#Nat Pendleton

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

[Note: This poll is a re-do of an older poll, as the original poll for it received less than 2,000 votes.]

#polls#movies#the thin man#the thin man 1934#the thin man movie#30s movies#old hollywood#w. s. van dyke#william powell#myrna loy#maureen o'sullivan#nat pendleton#minna gombell#have you seen this movie poll#redone poll

147 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nat Pendleton, Carole Lombard, and Chester Morris in Jack Conway’s THE GAY BRIDE (1934)

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

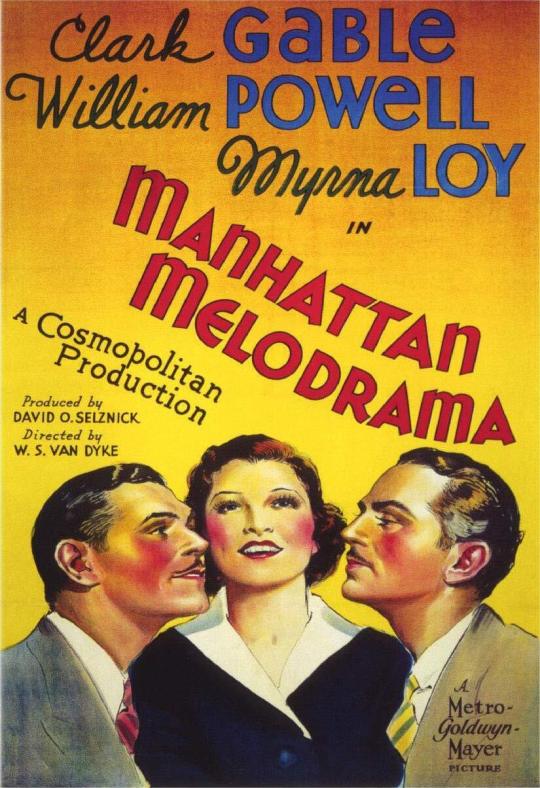

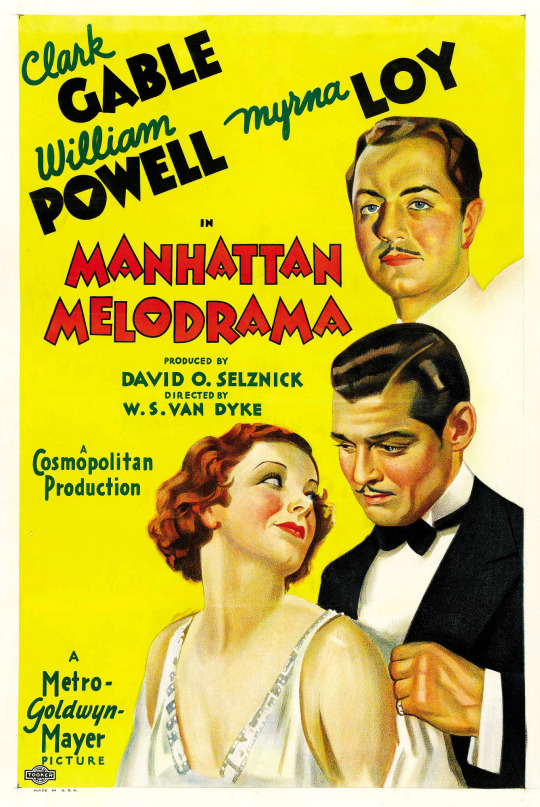

Manhattan Melodrama (1934) W.S. Van Dyke

April 14th 2024

#manhattan melodrama#1934#w. s. van dyke#clark gable#myrna loy#william powell#nat pendleton#leo carrillo#isabel jewell#muriel evans#pre-code#PreCodeApril

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eily Malyon-Henry Travers-Lionel Barrymore-Una Merkel-Nat Pendleton "On borrowed time" 1939, de Harold S. Bucquet.

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

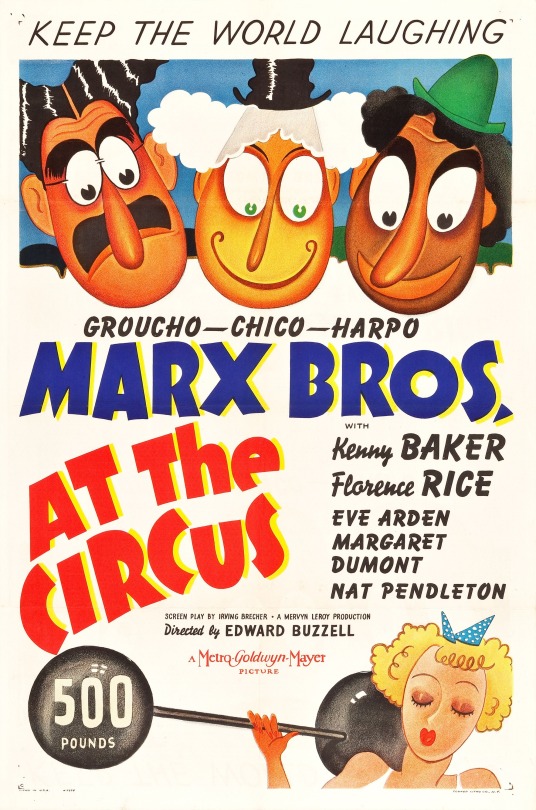

#At the Circus#Groucho Marx#Chico Marx#Harpo Marx#Kenny Baker#Florence Rice#Eve Arden#Margaret Dumont#Nat Pendleton#Edward Buzzell#1939

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

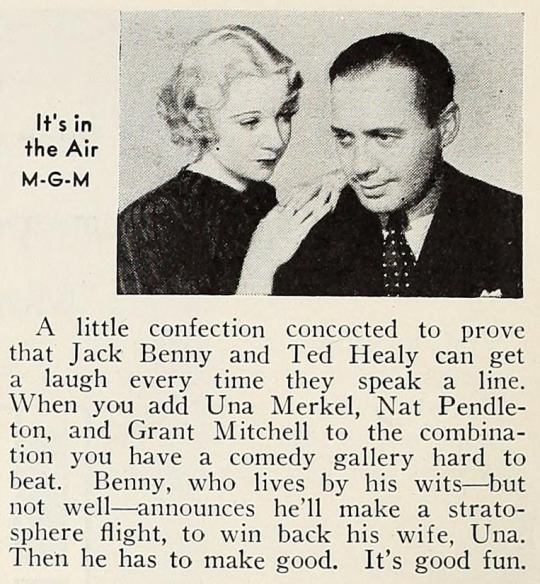

Screenland magazine, January 1936

#una merkel#jack benny#nat pendleton#grant mitchell#ted healy#it's in the air#1935#1930s#1936#hollywood#old hollywood#classic hollywood#vintage hollywood#screenland#magazine#screenland magazine#movie magazine

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Borrowed Time (1939)

As time marches on, certain names that were once synonymous with American drama lose their weight, even among film buffs. In the early twentieth century, the Barrymore siblings – Ethel, John, and Lionel – were celebrated on both Broadway and in Hollywood, each one making a successful transition from the silent era to synchronized sound. The eldest, Lionel, was born in 1878 and was a Hollywood elder statesman when he made 1939’s On Borrowed Time. Directed by Harold S. Bucquet and based on a 1938 play of the same name by Paul Osborn (itself based on a 1937 Lawrence Edward Watkin novel of the same name), On Borrowed Time is a star vehicle for the eldest Barrymore. By the late 1930s, Barrymore had broken his hip twice – never healing properly. As such, he remained wheelchair-bound for the remainder of his life. Physical disablement, even in modern Hollywood, often curtails acting careers. But Barrymore’s home studio, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM), often had their screenwriters find ways to incorporate Barrymore’s disability.

Lionel Barrymore was also in physical pain and depended on cocaine injections to work and sleep. However, this never affected his acting, as he delivers a wonderful lead performance in On Borrowed Time. Those less knowledgeable about this period in Hollywood history will probably only recognize his surname and the acting family he came from. Nowadays, most cinephiles probably only know of Lionel Barrymore through It’s a Wonderful Life (1946; Barrymore played the villainous Mr. Potter). Lionel Barrymore's role as the somewhat foul-mouthed but caring grandfather here offers something completely different.

Mr. Brink (Cedric Hardwicke) is hitchhiking somewhere near a small town in contemporary America. But he is not interested in riding with just anyone:

MAN IN CONVERTIBLE: May I give you a lift, sir? MR. BRINK: Thank you, no. I have an appointment – a lady and gentleman. MAN IN CONVERTIBLE: Oh, I’m sorry. [coughs] I thought you signaled me. MR. BRINK: No. Not yet...

As you may have guessed, Mr. Brink is a personification of death. A few minutes later, he flags down that lady and gentleman and takes their lives in a car accident. That couple are the parents of John “Pud” Northrup (Bobs Watson; best known as Pee Wee in 1938’s Boys Town), who will now live solely under the care of Gramps and Granny (Barrymore and Beulah Bondi) and their housemaid Marcia (Una Merkel). At the memorial service for Pud’s parents, Gramps donates a substantial sum to the church. After learning of Gramps’ generosity, Pud exclaims that his grandfather doing such a good deed should allow him a wish. Gramps’ wish: as a deterrence local children stealing his apples, he wishes that anyone who climbs up his apple tree will be stuck there until he permits them down. Some time later, Mr. Brink arrives at Northrup grandparent homestead for an appointment with Gramps. Gramps tricks Mr. Brink up the apple tree, trapping him there – setting off a series of developments that put Gramps in a moral bind.

In a cast already headlined by character actors, how about some more? On Borrowed Time also features Henry Travers (the guardian angel Clarence in It’s a Wonderful Life) and Nat Pendleton as neighbors, Grant Mitchell as Gramps’ lawyer, James Burke as the sheriff, Charles Waldron as the reverend, and an uncredited Hans Conried (Captain Hook and Mr. Darling in 1953’s Peter Pan) as the man in the convertible.

Elsewhere, away from the camera, one can’t find much of composer Franz Waxman’s (1935’s Bride of Frankenstein, 1951’s A Place in the Sun) string-dominated score anywhere, but this is one of Waxman’s finest scores of his early career.

The opening half-hour of On Borrowed Time are its weakest. Hardwicke’s Mr. Brink has an eerily charismatic first impression that the scenes immediately following it cannot hope to match. Instead of learning more about the nature of Mr. Brink, the film instead shows us some of Pud’s misadventures and his relationship with his grandparents. Strangely, the loss of his parents seems to have had little effect on Pud at all, although his sadness seems to emerge in his contentious relationships with the other local boys and Aunt Demetria (Eily Malyon). Aunt Demetria, shortly after the Northrup parents’ deaths, hatches a scheme to assume guardianship of Pud and attain access to his considerable inheritance. Her designs are so obvious to all that when Gramps and Pud start calling her a “pismire” (literally, a pissing ant), Granny looks the other way when she might otherwise correct their boorish behavior. All of this takes longer to develop than it should (it does not help that Bobs Watson’s performance as Pud feels disjointed, but more on that shortly), even if the opening act primarily serves to show us how close Pud is to his grandparents. Even though we sense where the dramatic stakes are headed, On Borrowed Time almost seems to splinter into another film before we see Mr. Brink again.

In addition, contemporary reviews of On Borrowed Time lambasted screenwriters Alice D.G. Miller (1929’s The Bridge of San Luis Rey) and Frank O’Neill (no other film credits) for sanitizing the language from the original stage play due to the demands of the Hays Code (the self-censorship code that applied to major Hollywood studios from 1934-1968, repealed in favor of the current MPA ratings system). For the record, the text of the stage play was not freely available as I was writing this piece, so I have no means of comparison. Paul Osborn’s On Borrowed Time has only appeared on Broadway thrice: the 1938 original production and short-lived revivals in 1953 and 1991. The play had also been adapted for radio and television.

Compared to those film reviewers during the film’s 1939 release and many modern writers, I tend to be more forgiving if the Hays Code-enforced changes to a film do not significantly alter the spirit of the text. Sure, it would be funnier to hear disparaging language stronger than “pismire” in a 1939 film, but Pud’s and Gramps’ feelings towards Aunt Demetria, the apple-stealing boys, and Mr. Brink are comprehensible in this movie.

The closing two acts of On Borrowed Time draw its strengths from the performances and the narrative’s adoption of fairy tale logic (any film beginning with death flagging down folks he has an “appointment” with is almost always operating under the terms of the fantasy genre). In tandem, Lionel Barrymore and Bobs Watson’s good-humored and loving rapport lift the film above its structural flaws. Barrymore’s Gramps – an American Civil War and Spanish-American War veteran* – is a classic small town curmudgeon, only allowing his bitter exterior to crumble when Granny and Pud are around. Looking to protect Pud from Aunt Demetria, Gramps remains defiant towards the wills of Mr. Brink and the insistent neighbors. Perhaps it is not the greatest Lionel Barrymore performance, but he is always effective.

Bobs Watson, as Pud, is inconsistent anytime he does not share the scene with Barrymore. The explanation for his performance comes from Watson himself: “My dad was the one that really directed me, and I think some of the directors resented it a little bit… I trusted my dad implicitly, so I read the dialogue the way he told me.” His father’s influence results in occasionally overcooked line readings against director Harold S. Bucquet’s vision (MGM’s Dr. Kildare series, 1943’s The Adventures of Tartu), more theatrical than what the scene calls for. But when the scene calls for crying, by golly can Watson (who had a reputation for crying on cue) deliver. And his scenes with Barrymore are beautifully acted, convincingly showing the audience the love between grandson and grandfather.

Sir Cedric Hardwicke, a noted Shakespearean actor, cuts no corners as Mr. Brink. Mr. Brink is aware that, in time, he will keep all his appointments. Hardwicke plays Brink as slightly menacing, always dignified (no one expects that perfect an English accent in rural America), and somewhat aloof to what he probably thinks are childish trivialities and life’s mundane moments. He is the antagonist, but in no way is he the villain of this movie. That belongs to Eily Malyon as Aunt Demetria, a character some compare to Margaret Hamilton’s Mrs. Gulch/Wicked Witch from The Wizard of Oz (1939; released a little more than a month after On Borrowed Time) due to her temperament and unbending nature. One wishes the film made more use of the always-underappreciated Beulah Bondi as Granny (Bondi very often played elderly mothers and grandmothers, almost always appearing much older than she actually was), too.

Death and loss are two themes currently popular in modern cinema (see: a vast bulk of Pixar’s filmography, 2016’s Manchester by the Sea, 2019’s The Farewell, and a large selection of pieces from any film festival worldwide), but in the early decades of talkies in Hollywood, you would be hard-pressed to find films in which those themes were truly central, not secondary, to the narrative. And when those themes do appear, they appear in the context of fantasy films, like Death Takes a Holiday (1934) and On Borrowed Time. Anecdotally, I suspect the scarcity of major Hollywood movies revolving around death and loss is partly due to the realities of the 1930s and 1940s. Audiences, concerned with a worldwide Great Depression and soon a Second World War, did not seek films ruminating about death and loss and sought escapist fare instead. There was enough despair to go around.

The film that emerges on the back of these performances is thanks to its ability not to concentrate on the fantastical situation the Gramps and Pud find themselves in, but to raise the moral questions that Mr. Brink’s presence – and eventual entrapment – poses. Mr. Brink’s time in the tree results in consequences that Gramps and Pud could not imagine. Gramps’ decision to delay his death for the love of his grandson is concurrently noble and selfish. It is noble in respect to wanting the best for Pud, so that he may live life away from his aunt’s icy attitude and pernicious designs regarding her nephew’s inheritance. But it is selfish in that, as Gramps learns, that Brink’s inability to make any appointments unless he comes down from the apple tree means that almost no living being can die (for spoiler reasons, I am not listing the exceptions here) – even the ones in physical pain. How is Gramps supposed to navigate this situation, in addition to the communal and legal pressures from his neighbors and the police?

A resolution comes abruptly, in a way that devastates Gramps (but would probably make the Brothers Grimm nod in appreciation). On Borrowed Time’s bittersweet ending is deserved, and – as long as the viewer accepts the film’s fantastical premise and rules – will play quite differently for audiences of different ages.

Lionel Barrymore had two daughters with Doris Rankin, his first wife. Barrymore and Rankin lost both daughters in their infancies; neither ever truly recovered from their losses. One wonders what Barrymore thought while making On Borrowed Time, a film that argues for one coming to terms with death, however unfair or untimely its arrival. For a 1939 release (a legendarily glorious year for American cinema), positioning such ideas as the film’s narrative keystone ensures On Borrowed Time a unique spot in the early years of Hollywood’s Golden Age.

My rating: 8/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating. My interpretation of that ratings system can be found in the “Ratings system” page on my blog. Half-points are always rounded down.

* Gramps describes himself as having fought for the Union. This might make Gramps close to ninety years old, give or take, if we are to believe the film’s self-professed setting!

For more of my reviews tagged “My Movie Odyssey”, check out the tag of the same name on my blog.

NOTE: This is the 800th full-length Movie Odyssey review I have published on tumblr.

#On Borrowed Time#Harold S. Bucquet#Lionel Barrymore#Beulah Bondi#Cedric Hardwicke#Bobs Watson#Una Merkel#Nat Pendleton#Henry Travers#Grant Mitchell#Eily Malyon#James Burke#Charles Waldron#Alice D.G. Miller#Frank O'Neill#Lawrence Edward Watkin#Paul Osborn#Franz Waxman#TCM#My Movie Odyssey

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Round 1, Match 35

Nat Pendleton vs Clarence Kolb

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sing and Like It

William A. Seiter’s SING AND LIKE IT (1934, Criterion Channel through month’s end) starts sluggishly. An argument scene between gangster Nat Pendleton and moll Pert Kelton doesn’t have the zing you’d expect from such expert players. In the middle of a safecracking heist, however, Pendleton hears amateur actress Zasu Pitts singing a horridly sentimental song, “Your Mother,” and the film and plot take off. Pitts was noted for her fluttery delivery, and she does it so well she can work countless changes on it, as the situation demands, and it’s always funny. She has to sing “Your Mother” three times, which would be a lot for such a bad song, but each time her delivery is different, reflecting the circumstances of each performance. Determined to make Pitts and the song a hit on Broadway, Pendleton strong arms a top producer into making her the star of the show he’s about to open. With Edward Everett Horton as the harried producer, the film becomes almost delirious. He was an ace at playing high-strung characters, which somehow makes his zingers about Pitts’ lack of talent even funnier. Joking is his only defense against the gangsters taking over his life. Pendleton has one of his henchmen create new jokes for the show and even figures out a way to get an audience on opening night. With the opening, the picture takes some pretty devastating shots at critics and audiences (the elder critic advises a younger one, “if every you have anything good to say about an actor or a playwright, wait ‘til he’s dead. Because you cannot possibly do any good…for a corpse.”). The film is a clear influence on Woody’ Allen’s BULLETS OVER BROADWAY (1994) and even has hints of THE PRODUCERS (1967). Ned Sparks is Pendleton’s second-in-command, with a delivery so dry he could make you laugh at a death notice. You can tell it’s a pre-Code film because Pendleton and Kelton are clearly living together while unmarried, and there are refences to Horton and his secretary’s both being gay.

#pre-code hollywood#zasu pitts#edward everett horton#gangster comedy#nat pendleton#pert kelton#ned sparks

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Films Watched in 2025: 23. Buck Privates Come Home (1947) - Dir. Charles Barton

#Buck Privates Come Home#Charles Barton#Bud Abbott#Lou Costello#Tom Brown#Joan Shawlee#Nat Pendleton#Beverly Simmons#Don Porter#Donald MacBride#Abbott and Costello#Films Watched in 2025#My Edits#My Post

0 notes

Text

The Mad Doctor of Market Street

The Mad Doctor of Market Street – scientist Lionel Atwill fails to revive a subject in a suspended animation experiment, who dies. Then … Continue reading The Mad Doctor of Market Street

#1942#Anne Nagel#Bess Flowers#Claire Dodd#Hardie Albright#Lionel Atwill#mad scientist#Milton Kibbee#Nat Pendleton#Noble Johnson#Una Merkel#Wade Boteler

0 notes

Text

#polls#movies#the thin man#the thin man 1934#the thin man movie#30s movies#old hollywood#w.s. van dyke#william powell#myrna loy#maureen o'sullivan#nat pendleton#minna gombell#requested#have you seen this movie poll

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nat Pendleton (August 9, 1895 – October 12, 1967)

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Mad Doctor of Market Street (1942) Joseph H. Lewis

September 30th 2024

#the mad doctor of market street#1942#joseph h. lewis#una merkel#claire dodd#lionel atwill#nat pendleton#richard davies#noble johnson#john eldredge#rosina galli#a bit bonkers

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nick und Nora, jetzt mit Baby, aber immer noch nicht richtig verantwortungsbewußt, ignorieren einmal mehr, daß Nick sich eigentlich zur Ruhe setzten wollte und ermitteln wieder, aber aus guten Grund, das Mordopfer war nämlich ihr Finanzverwalter.

#Another Thin Man#Myrna Loy#William Powell#Otto Kruger#Virginia Grey#C. Aubrey Smith#Ruth Hussey#Nat Pendleton#Patric Knowles#Marjorie Main#Film gesehen#W. S. Van Dyke

0 notes

Text

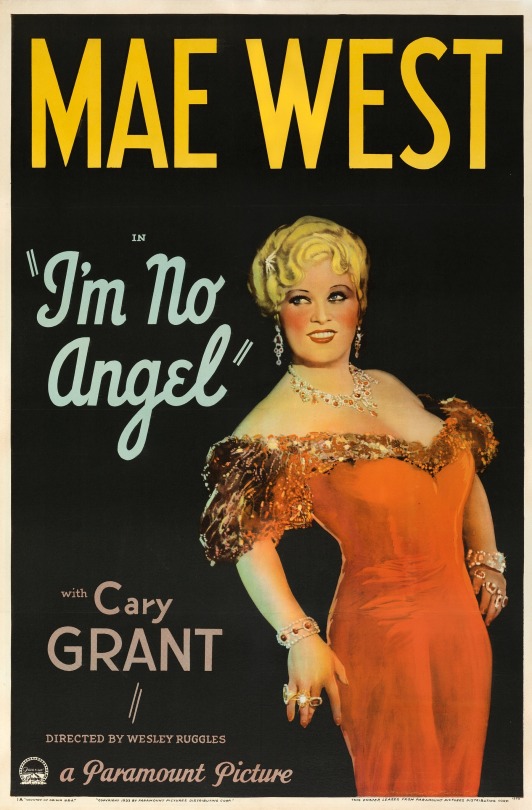

THE SCREEN: “Mae West Reveals Herself as a Circus Queen in “I’m No Angel” at the Paramount—Saturday's Millions”

I'M NO ANGEL, based on a story by Mae West and supported by Lowell Brentano; music and lyrics by Harvey Brooks, Gladys Du Bois and Ben Ellison; directed by Wesley Ruggles; a Paramount production. At the Times Square and Brooklyn Paramounts.

Tira .... Mae West Jack Clayton .... Cary Grant Bill Barton .... Edward Arnold Slick .... Ralf Harolde Alicia Hatton .... Gertrude Michael Kirk .... Kent Taylor Thelma .... Dorothy Peterson Benny Pinkowitz .... Russell Hopton Beulah .... Gertrud Michael The Chump .... William Davidson Rajah .... Nigel de Bruller Bob .... Irving Pichel Omnes.... George Bruggeman Harry .... Nat Pendleton Chauffeur .... Morrie Cohen Judge .... Walter Walker

by MORDAUNT HALL.

Arrayed in a variety of costumes which set off her sinuous form, Mae West is appearing at the Paramount in her latest screen vehicle, "I'm No Angel," a title which, as might be surmised, fits the leading character. Here Miss West, who wrote the story herself from “suggestions contributed" by Lowell Brentano, is beheld as a circus beauty named Tira, who wins applause and admiration by risking her blond head in a lion's mouth twice daily.

It is a rapid-fire entertainment, with shameless but thoroughly contagious humor, and one in which Tira is always the mistress of the situation, whether it be in the cage with wild beasts, in her boudoir with admirers or in a court of law.

Tira is ever ready with & flip double entendre and' she permits no skeleton to be found behind her cupboard doors. She has an emphatic personality, which proves a magnet for even social lights with millions. She receives costly presents, Including diamond necklaces, but she is hardly a gold-digger. She refrains from posing, preferring to keep to her natural slangy speech in her journey through the story from a tent to a penthouse.

She admits that she has thrown discretion to the winds, and she sometimes finds herself in an awkward predicament, but through a wily lawyer she succeeds in proving that she is guiltless. The feeble parts of this picture are those in which a criminal known as Slick is introduced. The less one sees of him the better one feels, for the production is interesting only as long as it proceeds on its merry route.

The glimpses of Tira making her impressive entry to the circus arena and then proceeding to the big cage with the roaring lions are depicted shrewdly. Tira does not actually stick her whole head in the lion's mouth, but contents herself by putting her face between the beast's jaws, which is quite enough.

Even this is set forth with a certain degree of fun, and one feels that Tira probably has a pistol ready for an emergency and that other circus employees are ready to shoot in the event that the beast starts to close its mouth. But one is apt to wonder whether they could possibly be quick enough. Society among the spectators is thrilled, all except one snobbish girl, who is furious because her fiancé is very enthusiastic over the performer's courage-and her beauty.

Later there comes the time when Tira puts her fair head into a court of law as the plaintiff in a breach-of-promise case. She sues Jack Clayton, whom she really loves, for $1,000,000, and it is not Tira's artful counsel who wins the case, but the circus queen herself. She cross-examines the defendant's witnesses and turns their testimony in her own favor, the unusual proceeding being countenanced by a judge whose sympathy Tira wins with the utmost ease.

Miss West plays her part with the same brightness and naturalness that attended her second film role. There is no lack of spontaneity in her actions or in the utterance of her lines. She is a remarkable wit, after her fashion. Cary Grant is pleasing as Clayton and Walter Walker is excellent as the considerate old judge. Gregory Ratoff does well as Tara’s lawyer. Wesley Ruggles has directed the film with his usual intelligence.

#Paramount Pictures#I’m no Angel#Mae West#Cary Grant#Edward Arnold#Ralf Harolde#Gertrude Michael#Kent Taylor#Dorothy Peterson#Russell Hopton#Gertrud Michael#William Davidson#Nigel de Bruller#Irving Pichel#George Bruggeman#Nat Pendleton#Morrie Cohen#Walter Walker#Mordaunt Hall#The New York Times

1 note

·

View note