#Muckle Flugga

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

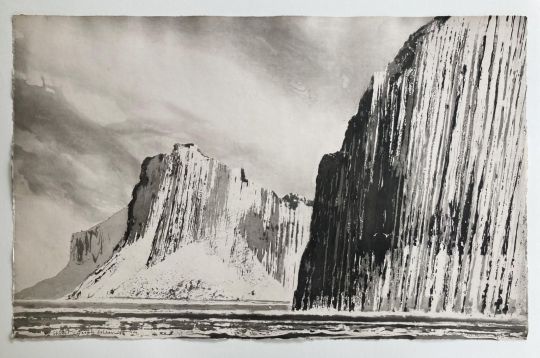

Based in Bermondsey in London, Norman Ackroyd RA (b. 1938) is one of Britain's most celebrated contemporary printmakers. Originally from a working-class area of Leeds, he started working from an early age in his family’s local butchers, alongside his father and older brothers. However, spurred on by his mother and art teacher, he soon made the brave and unexpected move towards a career in art. Today, he is primarily known for his captivating etching and aquatint landscapes, whose processes can be likened to engraving using acid. Aquatint is actually a variant of etching which produces different tones rather than lines. However, Ackroyd does often experiment with watercolours, his preferred medium when working directly onto paper.

1. THE RUMBLINGS, MUCKLE FLUGGA, SHETLAND by Norman Ackroyd RA Framed Etching 50 x 80cms.

2. FLANNAN ISLANDS by Norman Ackroyd RA Etching ( unframed ) 49.5 x 77 cm.

3. ST KILDA IN SUNLIGHT - STAC LEE by Norman Ackroyd RA Etching (framed & glazed) 48 x 77 cm.

4. MORNING SUNLIGHT BEMPTON CLIFFS by Norman Ackroyd RA Etching ( unframed ) 49 x 77 cm.

5. SHIANT GARBH EILEAN by Norman Ackroyd RA Etching ( unframed ) 49.5 x 78 cm.

Images are from The Stratford Gallery

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Norman Ackroyd

I like Ackroyd's work because of how much realistic texture he captures in his prints inspired by landscapes. Considering my project relates to the sea, I was drawn to his works of coasts and the ocean. He works in a range of different media but is most famous for his etchings.

I think he creates a wonderful sense of the movement and turbulence of the sea. The way he used etching to suggest texture really inspired my work.

(Fragments, Norman Ackroyd)

(Norman Ackroyd, The Rumblings, Muckle Flugga, Shetland (1), 2013, Etching with aquatint)

(1014 - Clare Island, Co. Mayo)

0 notes

Text

Muckle Flugga - a walk on the wild side

Wednesday 19th July

Just over 600 people live on Unst though as many tourists will be around in the summer months. Few of those tourists stay on the island though. Now, in Unst Fest week, most visitors are here for the day from Brae or Lerwick.

Hermaness is the destination of most visitors to Unst, and the 2 miles of boarded trail from the Nature Reserve car park are the most popular trek on the island. The weather has been wild all week, but today was particularly so, with 40 mile per hour winds, and squally showers that merged into what might better be termed, as simply, rain. Though in it, one didn’t get wet for long, as that 40 mph wind had a drying effect. It was a maximum on 10C, feeling much less than that in the wind. As is evident, not a great day for clear photos..

At the end of the 2 miles of boardwalk are the cliffs at Toolie, 150 metres down to the ocean waves, crashing into the rocks below. At this point today, it was difficult to stand up. From here there is a path both to the north and south along the cliffs. I didn’t fancy it, I’m not great on cliff edges at the best of times, but today conditions required even more nerve. Roja is fine, but there are a lot of rabbits here, and the mix of the three things, rabbits, labradors and cliff edges, doesn’t go well. The photo above is about 3 metres from the edge.. I didn’t want to go any closer.

Instead we hiked up to the summit of Hermaness Hill, at 206 metres, from where I hoped we would get some views out to Muckle Flugga, and we were rewarded.

Photo of the day was Roja getting skua’d again.. bomber by a Great Skua, to whom one can attach little blame, her chicks were close.

Muckle Flugga Lighthouse is Britain’s most northerly lighthouse. The jagged towering rock of Muckle Flugga lies a mile off the northwestern tip of the island. Its name derives from “mikla flugey”, which means large steep-sided island in old Norse.

This is a Stevenson lighthouse, although when it was commissioned in 1851 David Stevenson visited in atrocious weather and recommended other sites, as this was too wild. However, the Admiralty overruled Stevenson and decided the light would be built. The first, intended only to be temporary, light, was damaged beyond repair in a storm in 1854. Replacing it was a 64 foot tower, embedded 15 feet into the rock below, and standing 220 feet above sea level. The Stevenson’s supervised, but it was difficult and expensive (they were paid more than double the standard rate) to find workmen. All the materials had to be transported by boat, landed at an exposed rock, and carried up to the 200ft summit. Sometimes provisions could not be landed due to the weather conditions. It was first lit on January 1st 1858.

Robert Louis Stevenson visited Muckle Flugga on 18th June 1869 with his father Thomas. It is reputed that Unst may have been one of the locations to inspire Robert Louis to write his novel Treasure Island.

Four families of keepers lived at Burrafirth Shore Station, just below where I was parked in a relatively sheltered position. A relief boat, which often had difficulty landing, ferried keepers to Muckle Flugga on rota. The boatman’s house was Shoreline Cottage, now a holiday cottage. Both the Shore Station and the Cottage in the photo below..

In the 1950s one of the skippers rescued a Swiss woman who had fallen from the cliffs at Toolie. When she was recovered and at home, she sent him a cuckoo clock. When I read this I found it difficult to believe that anyone could survive such a fall, let alone get rescued afterwards as well.

In 1939 the lighthouse was enabled with radio contact which made staying in touch with the Shore Station much easier. Muckle Flugga was one of the last British lighthouses to get automated, in 1995. The Burrafirth Shore Station was sold off as two private houses. They are incredible places to live.

Despite the wild weather we were out for about three and a half hours, for just more than 6 miles, and then decided to get out the worst of the wind, and head across the the eastern side of the far north of Unst.

We are parked up at Norwick Beach, in a spectacular situation practically on the beach itself. This is just a few hundred metres from Saxa Vord, the UK’s new space port. More on this tomorrow..

0 notes

Text

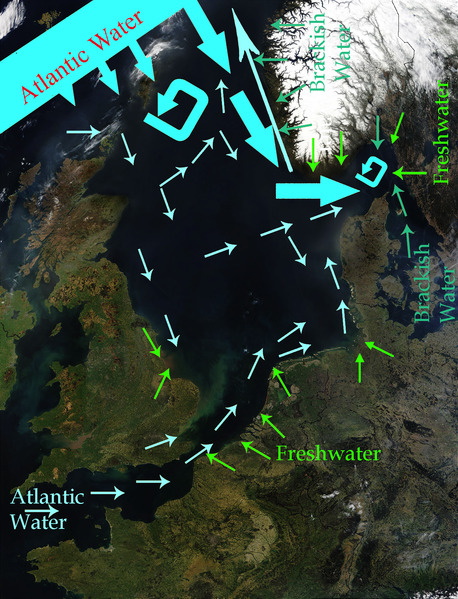

About North Sea, facts and maps

The North Sea (historically also known as the German Ocean) is a part of the Atlantic Ocean, located between Norway and Denmark in the east, Scotland and England in the west, and Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium and France in the south. The North Sea is one of the world's most important fishing grounds. The sea is also rich in oil and gas. Anthropogenic impacts have been significant for many years. The North Sea is a body of water surrounded by the following countries: Norway – Vestlandet. Denmark – separating it from the Baltic Sea. Germany – the states of Schleswig-Holstein and Lower Saxony, with ports at Bremerhaven and Hamburg. The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium and France. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian Sea in the north. It is more than 970 kilometres (600 mi) long and 580 kilometres (360 mi) wide, covering 570,000 square kilometres (220,000 sq mi). It hosts key north European shipping lanes and is a major fishery. The coast is a popular destination for recreation and tourism in bordering countries, and a rich source of energy resources, including wind and wave power. The North Sea has featured prominently in geopolitical and military affairs, particularly in Northern Europe, from the Middle Ages to the modern era. It was also important globally through the power northern Europeans projected worldwide during much of the Middle Ages and into the modern era. The North Sea was the centre of the Vikings' rise. The Hanseatic League, the Dutch Republic, and the British each sought to gain command of the North Sea and access to the world's markets and resources. As Germany's only outlet to the ocean, the North Sea was strategically important through both World Wars. The coast has diverse geology and geography. In the north, deep fjords and sheer cliffs mark much of its Norwegian and Scottish coastlines respectively, whereas in the south, the coast consists mainly of sandy beaches, estuaries of long rivers and wide mudflats. Due to the dense population, heavy industrialisation, and intense use of the sea and the area surrounding it, there have been various environmental issues affecting the sea's ecosystems. Adverse environmental issues – commonly including overfishing, industrial and agricultural runoff, dredging, and dumping, among others – have led to several efforts to prevent degradation and to safeguard the long-term economic benefits. The International Hydrographic Organization defines the limits of the North Sea as follows: On the Southwest. A line joining the Walde Lighthouse (France, 1°55'E) and Leathercoat Point (England, 51°10'N). On the Northwest. From Dunnet Head (3°22'W) in Scotland to Tor Ness (58°47'N) in the Island of Hoy, thence through this island to the Kame of Hoy (58°55'N) on to Breck Ness on Mainland (58°58'N) through this island to Costa Head (3°14'W) and Inga Ness (59'17'N) in Westray through Westray, to Bow Head, across to Mull Head (North point of Papa Westray) and on to Seal Skerry (North point of North Ronaldsay) and thence to Horse Island (South point of the Shetland Islands). On the North. From the North point (Fethaland Point) of the Mainland of the Shetland Islands, across to Graveland Ness (60°39'N) in the Island of Yell, through Yell to Gloup Ness (1°04'W) and across to Spoo Ness (60°45'N) in Unst island, through Unst to Herma Ness (60°51'N), on to the SW point of the Rumblings and to Muckle Flugga (60°51′N 0°53′W) all these being included in the North Sea area; thence up the meridian of 0°53' West to the parallel of 61°00' North and eastward along this parallel to the coast of Norway, the whole of Viking Bank is thus included in the North Sea. On the East. The Western limit of the Skagerrak . Why is North Sea so rough? Because the North Sea is shallow, with an average depth of less than 328 feet, its waters can get choppy -- a result of tidal patterns and storms. While all this churning brings up nutrients to the surface that help its marine life thrive, it's not ideal for cruising outside of the summer months. Which countries own the North Sea? While most reserves lie beneath waters belonging to the United Kingdom and Norway, some fields belong to Denmark, the Netherlands, and Germany. Most oil companies have investments in the North Sea. Can you swim in North Sea? For example, the North Sea in the UK, which is on our doorstep, has very low sea temperatures, but that doesn't stop people from swimming in it. In fact, on the northeast coast of England, there are many beaches where you can swim in the icy water year-round!

Who owns oil in the North Sea? The Norwegian and British sectors hold most of the large oil reserves. It is estimated that the Norwegian sector alone contains 54% of the sea's oil reserves and 45% of its gas reserves. What is a North Sea danger? The North Sea is one of the most dangerous seas in the world. It has wild storms and foggy winters. Because the sea is mostly shallow, the currents are strong and often pull in different directions. Even though the North Sea can be dangerous, it is important to trade. Is North Sea a land?

Doggerland is a submerged land mass beneath what is now the North Sea, that once connected Britain to continental Europe. Named after the Dogger Bank, which in turn was named after the 17th-century Dutch fishing boats called doggers.

How warm is the water in the North Sea? Unsurprisingly the sea is colder in the northern extremes of the sea where temperatures reach an average low of around 6 °C (43 °F). The warmest summer temperatures are seen to the south and can regularly reach 18 °C (64 °F) in August. Is the North Sea very cold?

The waters of the North Sea are cold, ranging between 14 and 20 degrees C in the summer months. If you come from a country where the sea water temperature is above 22 degrees C all summer, and up to 26 degrees, it will be hard for you to swim in the chilly water of the North Sea. How deep is the North Sea? 700 m How much oil is left in North Sea? "The waters off the coast of the UK still contain oil and gas reserves equivalent to 15 billion barrels of oil equivalent (boe), enough to fuel the UK for 30 years, but more investment in exploration is needed to slow down the decline in domestic production to safeguard the nation's energy security.

Does the North Sea have fish?

Today mainly mackerel, Atlantic cod, whiting, coalfish, European plaice, and sole are caught. In addition, common shrimp, lobster, and crab, along with a variety of shellfish are harvested. Why is North Sea water brown? When the water looks murky or brown, it means there is a lot of mud, or sediment, in the water. Sediment particles can be so tiny that they take a long time to settle to the bottom, so they travel wherever the water goes. Rivers carry sediment into the bay, and waves and tides help keep the sediment suspended. Why do we sell North Sea oil? Currently 80% of North Sea oil is exported because there is little demand from the country's refineries for UK crude oil. But even gas – where there is domestic demand – is sold overseas. Does China own North Sea oil? Chinese investments in the North Sea China National Offshore Oil Corporation, or CNOOC, has stakes in multiple North Sea oil fields including one of the UK's highest producers Buzzard. CNOOC has further stakes in Golden Eagle, and the combined platform which oversees the Scott, Telford and Rochelle fields. Why is North Sea oil so important? Over its lifetime, the North Sea has contributed approximately NOK 16.5 trillion ($1.82 trillion at the time of writing) in today's NOK to the economy. In 2021 alone, it made up 20% of GDP, 20% of government revenues, 20% of investments, and 50% of total exports. What lives at the bottom of the North Sea?

Worms, crustaceans and shellfish live in holes and tunnels under the surface of the sea floor. If you look closely, you can identify quite a lot of life on the bottom: crabs and sea snails, such as laver spire shells and periwinkles, crawl around. Lots of other animals are attached to stones or ship wrecks. Is the North Sea very polluted? New research led by Cambridge earth scientists has documented heavy metal pollution along the North Sea coast over the last century. The study, published in the Marine Pollution Bulletin, used dog whelks collected from the Belgian and Dutch foreshores as a tool to identify changes in lead pollution over time. What is the North Sea also called?

The North Sea (historically also known as the German Ocean) is a part of the Atlantic Ocean, located between Norway and Denmark in the east, Scotland and England in the west, and Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium and France in the south. Is Atlantis in the North Sea? While Plato's story explicitly locates Atlantis in the Atlantic Ocean near the Pillars of Hercules, location hypotheses include Helike, Thera, Troy, and the North Pole. Is the North Sea salt water? The salinity averages between 34 and 35 grams per litre (129 and 132 g/US gal) of water. The salinity has the highest variability where there is fresh water inflow, such as at the Rhine and Elbe estuaries, the Baltic Sea exit and along the coast of Norway. Is the North Sea nice?

Seemingly endless beaches, chugging ships passing by, warm sand between your toes: The view of the North Sea landscape is impressive. So it's not surprising that many vacationers struggle to decide where to go on the North Sea. All the beaches have a unique charm there, yet some stand out in particular. The North Sea is bounded by the Orkney Islands and east coast of Great Britain to the west and the northern and central European mainland to the east and south, including Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. In the southwest, beyond the Straits of Dover, the North Sea becomes the English Channel connecting to the Atlantic Ocean. In the east, it connects to the Baltic Sea via the Skagerrak and Kattegat, narrow straits that separate Denmark from Norway and Sweden respectively. In the north it is bordered by the Shetland Islands, and connects with the Norwegian Sea, which is a marginal sea in the Arctic Ocean. The North Sea is more than 970 kilometres (600 mi) long and 580 kilometres (360 mi) wide, with an area of 750,000 square kilometres (290,000 sq mi) and a volume of 54,000 cubic kilometres (13,000 cu mi). Around the edges of the North Sea are sizeable islands and archipelagos, including Shetland, Orkney, and the Frisian Islands. The North Sea receives freshwater from a number of European continental watersheds, as well as the British Isles. A large part of the European drainage basin empties into the North Sea, including water from the Baltic Sea. The largest and most important rivers flowing into the North Sea are the Elbe and the Rhine – Meuse. Around 185 million people live in the catchment area of the rivers discharging into the North Sea encompassing some highly industrialized areas. Major features For the most part, the sea lies on the European continental shelf with a mean depth of 90 metres (300 ft). The only exception is the Norwegian trench, which extends parallel to the Norwegian shoreline from Oslo to an area north of Bergen. It is between 20 and 30 kilometres (12 and 19 mi) wide and has a maximum depth of 725 metres (2,379 ft). The Dogger Bank, a vast moraine, or accumulation of unconsolidated glacial debris, rises to a mere 15 to 30 m (50 to 100 ft) below the surface. This feature has produced the finest fishing location of the North Sea. The Long Forties and the Broad Fourteens are large areas with roughly uniform depth in fathoms (forty fathoms and fourteen fathoms or 73 and 26 m or 240 and 85 ft deep, respectively). These great banks and others make the North Sea particularly hazardous to navigate, which has been alleviated by the implementation of satellite navigation systems. The Devil's Hole lies 320 kilometres (200 mi) east of Dundee, Scotland. The feature is a series of asymmetrical trenches between 20 and 30 kilometres (12 and 19 mi) long, one and two kilometres (0.6 and 1.2 mi) wide and up to 230 metres (750 ft) deep. Other areas which are less deep are Cleaver Bank, Fisher Bank and Noordhinder Bank. Read the full article

#AretherewhalesintheNorthSea?#CanyouswiminNorthSea?#CanyouswimintheNorthSea?#DoesChinaownNorthSeaoil?#DoesitsnowintheNorthSea?#DoestheNorthSeagettsunamis?#DoestheNorthSeahavefish?#HowbigistheNorthSea?#HowdeepistheNorthSea?#HowmuchoilisleftinNorthSea?#Howmuchoilisleftintheworld?#HowwarmisthewaterintheNorthSea?#IsAtlantisintheNorthSea?#IsitNorthSea?#IsNorthSeaaland?#IstheNorthSeacold?#IstheNorthSeanice?#IstheNorthSeasaltwater?#IstheNorthSeaverycold?#IstheNorthSeaverypolluted?#IstheNorthSeawarm?#WhatcountryistheNorthSeain?#WhatisaNorthSeadanger?#WhatishappeningintheNorthSea?#WhatisspecialaboutNorthSea?#WhatisspecialabouttheNorthSea?#WhatistheNorthSeaalsocalled?#WhatistheNorthSeacalled?#WhatistheNorthSeaknownfor?#WhatlivesatthebottomoftheNorthSea?

0 notes

Photo

Walk to Muckle Flugga, Shetland

We took a whole day to spend on Unst, as we needed to get the ferry first to the island of Yell, then from there the ferry to Unst. We drove straight up North and started of at the car park for the Hermaness National Nature Reserve to make our way to see the northernmost part of Britain. I have looked at maps before and noticed a place called ‘Outstack’ and thought to myself: Yeah, I want to go there. Maybe some other time. It is a tiny island and you probably can only get there by boat, but I still got to see it. Outstack is the very last bit of Britain before the North Pole. Of course the walk up there was stunning. We had to take care to not fall off the cliffs but they were absolutely scenic, just as Orkney’s cliffs had been. It took us roughly 2 hours to get up to the view point. Probably my favourite part of our Shetland trip.

There was a gannet colony living along the coast as well, but I put it in a separate post.

Unst travel vlog here.

#unst#muckle flugga#outstack#hermaness#nature reserve#shetland#sheep#scotland#island#sea#cliffs#rugged coast#coastline#gannets#birds#nature#nikon#photography#nature photography#travel photography#landscape photography#photographers on tumblr

339 notes

·

View notes

Text

Contrary to the evidence shown in this blog over the past few days there is actually a lot more to Shetland than wool and knitting. I saw only a fraction of it (which is why we are planning to return in June … as well as Wool Week 2020) but here is a taste of the non-woolly beautiful world that is Shetland.

The view from Da Peerie Hoose as I stood outside in my pjs with my cup of tea and appreciated the magical morning light.

Channerwick south of Sandwick.

Birthday dinner at The String. Cannot recommend it highly enough though you will have to book (even if you aren’t there during Wool Week!) Live music upstairs to round off the evening. I started with scallops and belly pork.

Followed by Shetland halibut

And rounded off with one of the best cheese plates I have seen in a long while. Proper homemade oatcakes and a chutney good enough to eat on its own.

Memorial in Scalloway to the men who died on the Shetland Bus bringing agents and supplies in and out of occupied Norway during WWII.

Boat carving in the Delting Galley Shed. The Delting Up Helly Aa began in 1970 as a Senior School Festival and is now a huge festival including the communities of Voe, Mossbank, Muckle Roe and Vidlin.

The bill heads are attached to the ceiling but the sunlight streaming through the skylights made it impossible to photograph them. Here are some of the stunning shields.

Blue on blue. Small boat in Hay’s Dock outside the Shetland Museum and archives.

Waiting for a plane to land at Sumburgh airport in the south of the Mainland.

And here it comes

This is the view just to my left … note the beginning of the runway!

Looking down at the rocks below The Sumburgh Head Lighthouse.

While pretty northerly, the title of the most northern lighthouse in the UK belongs to Muckle Flugga lighthouse. The fishing up there is quite good too. This is Stuart’s 40lb cod.

View of TM Adie & Sons in Voe, for over a century one of the largest employers in the north east mainland of Shetland. Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay wore jumpers woven by Addie when they scaled Everest in 1953.

And finally, thank you to NorthLink Ferries for making the journey there and back so pleasant (even if everyone else did look a little green the following morning!)

See you in June Shetland.

Love Gillie x

Contrary to the evidence shown in this blog over the past few days there is actually a lot more to Shetland than wool and knitting.

#Airport#Birthday#fishing#Lighthouse#Muckle flugga#shetland#Shetland Bus#The String#TM Adie & Sons#Voe

0 notes

Photo

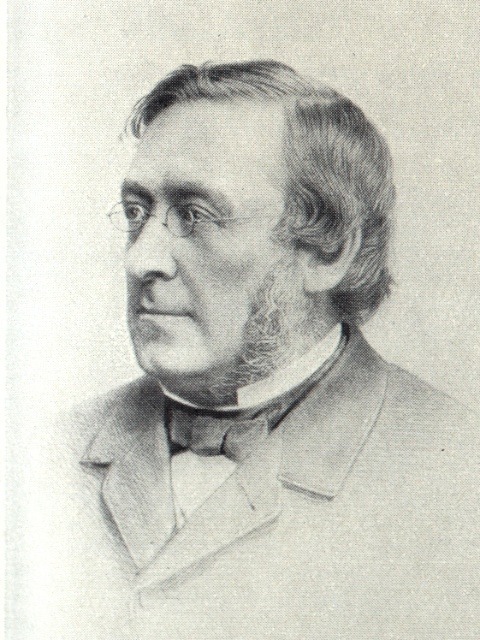

David Stevenson the Scottish lighthouse designer and engineer was born on January 11th 1815 in Edinburgh.

Born at 2 Baxters Place at the top of Leith Walk the son of Hean Smith and engineer Robert Stevenson. He was a brother of the lighthouse engineers, Alan and Thomas Stevenson. David Stevenson was educated at the High School in Edinburgh then studied at the University of Edinburgh.

Between 1854 and 1880 David Stevenson designed many lighthouses, all with his brother Thomas. In addition, he helped Richard Henry Brunton design lighthouses for Japan, inventing a novel method for allowing them to withstand earthquakes. His sons David Alan Stevenson and Charles Alexander Stevenson continued his work after his death, building nearly thirty further lighthouses.

The photographs are of the splendidly name lighthouse just off Shetland, called Muckle Flugga. The name comes from Old Norse, Mikla Flugey, meaning "large steep-sided island". It has frequently been noted on lists of unusual place names

It was first lit on 11th October 1854 and stands 15 metres above sea level

According to local folklore, Muckle Flugga and nearby Out Stack were formed when two giants, Herman and Saxa, fell in love with the same mermaid. They fought over her by throwing large rocks at each other, one of which became Muckle Flugga. To get rid of them, the mermaid offered to marry whichever one would follow her to the North Pole. They both followed her and drowned, as neither could swim!

27 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Norman Ackroyd(British, b.1938)

The Rumblings, Muckle Flugga Shetland 2013 via more

137 notes

·

View notes

Text

While vaguely researching islandy sounding names for ACNH I’ve made some quote interesting discoveries.

I’ve found out about Out Stack, an island, or more accurately, a large rock which is the most northern part of the UK. "the full stop at the end of Britain". Completely uninhabitable and you would reach the North pole if you traveled direct north.

Muckle Flugga is the isle directly below

Other words I considered:

Shetland Scottish Gaelic: Sealtainn Faroe Insi Catt—"the Isles of Cats" Bell Rock Eddystone Noss Lunna Fair Isle Brae Isle Folk

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

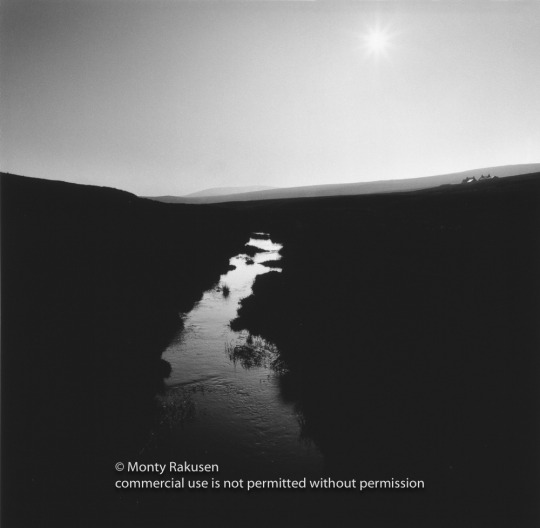

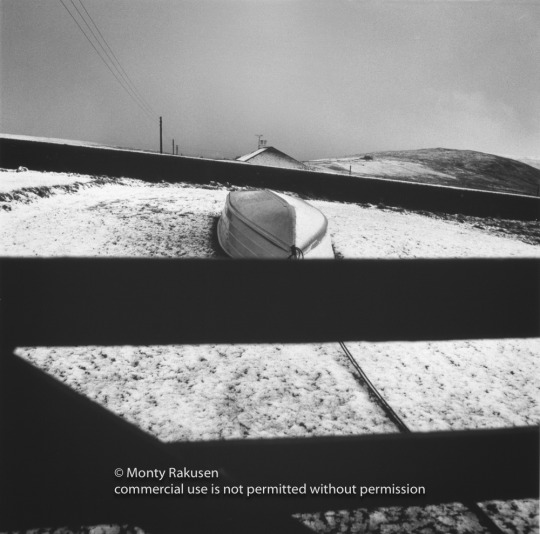

Voices in the Wind, the Northern Isles of Shetland Part 3

I awoke one morning in someone else’s flat and I couldn’t remember how I got there. My friend, fellow art student, Ceri Herington Pritchard https://ceripritchard.com/ decided we should go on an adventure.

"Let's go north" I said, and we did. We decided on Shetland, as it was as far north as we could think of going in the UK. It was October and cold, wintery, and Ceri let all the camping gas escape in Aberdeen before we had even got on the ferry. We didn’t have outdoor clothes like we have today. Ceri had a greatcoat and I had a tank driver's jacket, probably from the Korean war, that I’d stolen from the Combined Cadet Force at school.

When we arrived in Lerwick we headed north striding out as fast as we could. They were building the Sullom Voe oil terminal and the flat barren wind-swept landscape was dotted with ex red London double decker buses ferrying workers to the construction site, the destination windows read, Moorgate, Archway, Liverpool Street Station and so forth. We walked in a huge cavernous world of clouds coming from Greenland rising in the west and falling in the east with the sun shining through, highlighting the ceiling of our world and at sunset looked like God had appeared. I fell in a bog then it rained and there was freezing fog then I fell in a bog again.

On the 5th of November we were probably two of Europe’s most northerly campers, at the most northerly point of Shetland, a place where giants fought over the love of a mermaid, near the remote island of Muckle Flugga. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Muckle_Flugga

Miserable, with teeth chattering and wet feet, I wore all the clothes I possessed and had to get up at 3am to crack the ice off my tent. On another night because of a storm we slept in a cement store hut and upon waking covered in dust looked like ghosts. One night, camped on a windy beach we were kept awake by boulders rolling in the surf. It was always spine chillingly cold and was only relieved by whisky in friendly pubs that felt like someones front room and there was usually a fidler. These experiences only gave me a love for this beautiful and remote place in the middle of the North Sea.

Nowhere is more than a mile from the sea on Northern Shetland and it is almost tree-less. Small crofts are dotted here and there with flapping, coloured, washing drying on lines, fishing boats far out at sea and the smell of burning peat on the wind. In those days the place was littered with abandoned rusting vehicles and the sides of the roads were covered in empty beer cans with the smiling face of Venetia Stevenson looking up at us https://www.cannyscot.com/SweetheartStout.htm, people built walls from un-returnable beer barrels and crofts lay derelict. Later, I believe, a vicar ordered a ship to take all the scrap away. No matter what the weather there was always some hardy soul out in the landscape, a small moving dot in the distance digging the peat, driving the sheep, rowing a boat. If you listened carefully there were voices on the wind.

I loved this wonderful strange place and began to plan a photo documentary. I first returned and shot it in 35mm colour transparency with the hope of printing it up in Ciba Chrome of which I was a big fan. Unfortunately the processing lab put a scratch through every roll of film and in those days it was impossible to retouch.

Each year I would return, shooting medium format black and white first with Hasselblad and then later Rollie 6006/8 and I gradually built up a collection of images searching for the essence of the place. I became friends with people there, the local doctor from Mid Yell and some people who looked after otters. They recognised me in the pubs.

Some years I walked the islands, some years I took my blue Landrover with its home made stereo and two cassettes that I bought in Aberdeen, The Smiths, Meat is Murder and Elvis Costello, Almost Blue. I drove around in the simmer dim the grey evening light, eventually knowing both albums by heart. The RAF invited me to their mid-summer beach party, it never got dark and in the morning I was dive bombed by bonxsies, mad sea birds, as I staggered around the landscape looking for fresh water. I fell in a bog again.

I was befriended by people who fed me boiled ham and potatoes, plied me with drink and had me shoot shotguns at empty cans thrown in the air. “Just mind the sheep, lad”. Coming out of the most northerly pub at half past eleven at night with the sun still shining in my eyes I stepped onto a Norwegian Trawler and got caught up in a fight. We sat in the mess as they fought round and round on the tables and each time they came past we clutched our drinks to our chests.

The photography project ran out of steam, my life had changed, I was busy at work, until Lizzie encouraged me to finish it and we travelled back there together to see Up Helly Aa, the ceremonial burning of the Viking longship https://www.uphellyaa.org/ and to show my work in progress to Shetland Arts with a view to exhibiting it. We stayed in Mid Yell in the snow with 125mph winds full of ice. Huge squalls blew in from the ocean flying low, dropping ice into the waves. When we were in Lerwick we were guests of the head of the Jarl squad, the viking leader of Up Helly Aa, a tremendous honour.

In the early morning, whilst he slept, we secretly tried on his Viking gear. I always felt welcome there and people were kind. An exhibition was arranged in Lerwick, British Airways helped me fly it up and then it travelled all over Scotland. I was interviewed by a lovely lady with small round John Lennon Spectacles from Radio Shetland, only problem was I could hardly understand a word she said. The exhibition opening was very well attended from islands far and wide, made more impressive by the fact no one could get back home to their islands until the ferries restarted in the morning. I felt proud when they said I had shown their home to them in a different way.

Text edit: John Coombes Encouragement: Liz Rakusen

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Light North of Shetland

A Light North of Shetland

By Linda Tancs

The perils and adventures of lighthouse building no doubt influenced Robert Louis Stevenson, whose father and uncle designed some 30 lighthouses around Scotland’s coasts. One such lighthouse, Muckle Flugga, is the U.K.’s northernmost light, located on a rocky outcrop off the northern tip of Unst in the Shetland Islands. The island’s remote location is cited as inspiration for…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Video

Ancient Scotland from John Duncan on Vimeo.

facebook.com/johnduncanfilmmaker/ instagram.com/johnduncanfilmmaker/ john-duncan.co.uk

Having spent the past seven months travelling all over Scotland to shoot my new film, ANCIENT SCOTLAND, I’ve never been more proud to call this country home.

Shot at twenty one stunning locations from as the far north as Muckle Flugga at the very top of Shetland to the prehistoric wonder of Britain’s highest sea stacks near St Kilda, some 40 miles west of the Outer Hebrides.

As the third in a series of Scottish aerial films, I wanted to continue the progression of theme. My first film, Beautiful Scotland, was really just a collection of beautiful shots. My second, Wild Scotland, embraced the wild theme of this country, featuring many of our wild animals. So for this third instalment I had to look deeper at what defines Scotland for me. It soon dawned on me that Scotland has so much of the ancient about it, not just in terms of architecture but far older geology (a field of study which has its roots here). This led to a shot list ranging from incredible, imposing castles through to totemic sea stacks and the looming presence of St Kilda, a citadel of rock standing proud amidst the crashing maelstrom of the Atlantic which was inhabited until the 1930s.

Having already shot two films in Scotland, I’d already picked the low hanging fruit of the more accessible locations so the logistics of reaching and filming this film were definitely more challenging. Each shot involved some kind of, often physically demanding, adventure. Notable examples include a four day round trip to Shetland to capture 10 seconds of footage; the challenge of getting to the wildly remote sea stacks near St Kilda; and weathering 8 hours of miserable weather in a bivvy bag on a ridge in Skye, just to be there for sunrise.

The process of filming this has led to personal experiences which defy superlatives, not least the simple, awe inspiring, moments surrounded by silence as the sun rises over the horizon. Being on top of a mountain when the sun rises is an experience you will never forget.

Scotland is truly a country made for those who love the outdoors in its wonder. Get out and explore it.

BEHIND THE SCENES - vimeo.com/285829099

Shot on DJI Inspire 2 with X5S and X7, PRORES 422HQ

For footage licencing enquiries please email – [email protected]

** THIS FOOTAGE MUST NOT BE USED WITHOUT PRIOR PERMISSION **

0 notes

Text

northing

It is not down in any map; true places never are.

Herman Melville, from Moby-Dick

Muckle Flugga: 60° 51.3’N, 00° 53’W Sunset in summer, in the high latitudes of the Shetland Isles, is an uncertain hour the locals call simmer dim. The sun touches the horizon at around 11pm, and as its lower edge is drawn into the bleak, gunmetal oiliness of the North Atlantic swell, the pale umber cast across the high seaward cliffs begins to recede into shadow.

The light dims, but if the moon is full, the stubborn gloaming refuses to surrender to darkness. A couple of hours later, the sun will rise again, although on many days it will creep above the horizon unseen, shrouded by leaden stratus clouds that descend with the deep depressions that track north-eastwards across the Atlantic to rile the fast, south-going current of the North Atlantic Drift.

We had set off three days earlier from Castle Bay, on Eilean Barraigh (Barra Island), in the Scottish Western Isles — my friend, Michael Moulin, and I, aboard a fragile 7.5-metre yacht more suited to inshore day sailing than the long sea passages that were necessary to get as far as the Western Isles, let alone the Shetlands. We had weighed anchor at dusk and drifted from the lee of the high stone walls of Caisteal Chiosmuil (Kisimul Castle), the 600-year-old water-bound redoubt of the Clan MacNeill that rises from a reef in the middle of the bay. Then we reached under full sail through the narrow, rock-strewn channel between Barraigh and the southern island of Vatersay to the white-capped swells of the Atlantic, before bearing away north-west towards St Kilda, the grim shark tooth of barren, uninhabited peaks and rocky skerries that forms the westernmost island group of Britain.

Our course was plotted in the wake of Viking longships that made their escape through these waters from raiding parties to Ireland and the west coasts of England, Wales and Scotland a thousand years ago. They ran for the safety of the open sea on homeward voyages that would take them either north-east to the wide channel between the Orkneys and Sheltands then east to the Jutland Peninsula and the Baltic Sea or, like us, even further north, past the small, rugged islands of Sula Sgeir and Rona – more isolated even than St. Kilda — to a landfall on Unst, the most northern of the Shetland Isles, before rounding an outcrop called the Outer Stacks and laying a course to the fractured coast north-west of modern-day Stavanger, in Norway, where long, witch-finger fjords had been cleaved between high, sheer walls of rock by the stormy Norwegian Sea. Sailing deep within them, across sheltered waters as still and dark as molasses, the Norsemen would at last reach home — small, fortified settlements built close by the shore on rich grasslands coloured with star hyacinth and purple heather and backed by sloping stands of pine, spruce and juniper.

We had made our landfall off Gloup Holm, a small island off the north-west corner of Yell, one of the larger Shetland Isles. We had drifted a little further eastwards than we had planned. Two nights before, we had been forced to reef — and later, to hand — our sails in a rising south-westerly wind that veered westerly as we rounded St Kilda and became a severe gale. The steep following seas gained height and power as they rolled in without obstruction from the Atlantic and crossed the continental shelf. Solid water tumbled over the yacht’s transom into the open cockpit, sweeping us from our seats. Steering by hand became too dangerous. We lashed the tiller to leeward and let the boat drift a-hull as we took refuge in the cabin. More than once, a breaking crest tipped the yacht onto its gunwales, laying its mast in the water. We held our breaths as the hull shuddered, then plunged, as if in slow motion, down four storeys through the wave’s foam-streaked, perpendicular face. Only in the eerie, momentary windlessness of the trough did the righting moment of the vessel’s lead keel assert itself to lever the rigging from the sea.

Now the wind had dropped. The grim scud had dissipated and the swell, tinged a muddy brown by the churned-up detritus of the sea bottom and run-off from the shore, was a long, gently undulating lope. In a dying breeze, we closed the cliffs of Herma Ness to round the rocky outcrops of Muckle Flugga and the Outer Stacks. Atlantic puffins, clown-like birds with unlikely white and black heads, orange and black striped beaks and squat, rotund black bodies that even penguins would find ungainly, bobbed at the edge of deeply serrated skerries atop which other puffins protected their nests from predatory gannets and guillemots, each nest containing just one precious egg.

Sixty metres above the rookeries, on a lump of black rock too small to be called an island, loomed the Muckle Flugga lighthouse – a whitewashed stone tower, the only man-made structure on that line of longitude between the top of the British Isles and the North Pole. It was built in 1858 by David Stevenson and his brother, Thomas, father of the writer, Robert Louis Stevenson, who visited the light with his father and later, it is said, used a map of the tree-less island of Unst, off which Muckle Flugga lies, as inspiration for his novel, Treasure Island.

Lymington Quay: 50° 45.2’N, 1° 31.7’W Every summer, in every boatyard along the south coast of England, there was at least one crew preparing a yacht for a trans-Atlantic crossing. Most wouldn’t be ready in time — some never would be — but those who managed to work through their endless lists of yardwork, everything from replacing running rigging and reinforcing sails to checking rudder posts, pintles and gudgeons and antifouling the hulls, might finally cast off in early autumn and make for the warm waters below the 35th parallel.

The usual track was south-west, passing well offshore of the fearsome reefs and tidal races around Ile D’Ouessant, at the south-western corner of the English Channel, to cross the unpredictable maw of the Bay of Biscay to Cape Finisterre (in English, ‘the end of the world’). From there, they would make either for Gibraltar, at the entrance to the Mediterranean, or, more likely, the volcanic Canary Islands, off the coast of southern Morocco, where, like Christopher Columbus’s exploratory fleet 500 years before them, they would rest, make repairs and reprovision while they waited for the North Atlantic hurricane season to abate. Sometime in November, they would set off south-west again towards the Cap Verde Islands, standing well off the African coast.

After drifting through the humid calms and sudden rain squalls of the Horse Latitudes (a region between the 35th and 30th parallels dominated by a sub-tropical high and so named because, according to tradition, ships often lay becalmed for weeks there and their crews, fearful of running out of water and victuals and, worse, becoming afflicted by scurvy, threw cargoes of hungry horses and cattle overboard) they would pick up the north-easterly trade winds and, at last, alter course westwards, freeing their sails. A relentless wind off the starboard quarter and an easy following sea would carry them on an even keel all the way across the Atlantic to whatever islands in the Caribbean they might be bound.

I had lived and worked on the sea for half a decade. I had crossed the Atlantic twice, both times from west to east on a northerly route that took advantage of the Gulf Stream and the prevailing westerlies but was always hard, cold sailing, and never without a gale springing up within one of the low-pressure systems that followed one after the other with tedious frequency across the Atlantic’s higher latitudes. Once, during a leaden English winter, while I was helping a friend rebuild a 50-year-old Hillyard cutter in a cluttered boatyard on the Lymington River, relaying and caulking its timber decks in the few hours of rain-less daylight, I thought about sailing with him on the long, warm-water voyage to the southern Caribbean that he had planned for the following autumn.

And yet I knew somehow that I wouldn’t. There were no clear skies, fair winds or landfalls on palm-fringed cays in the voyages I made in my imagination; instead, the coasts were tree-less, steep and rock-strewn, beset by fast-running tidal streams and angry seas the same colour as the slate-grey skies. I daydreamed of high latitudes, of retracing routes once sailed by Norse longships, Phoenician and Celtic traders (the Veneti, a Celtic maritime tribe, ferried tin mined in Cornwall to the Gallic mainland), imperial Roman battle fleets and even the leather-hulled curraghs of fifth-century Christian monks. A trade-wind passage was dull compared with the demands of navigating the treacherous jigsaw of reefs, skerries and precipitous islands and the constantly changing weather conditions to the west and north of Wales, Ireland and Scotland, where tidal races tripped over jagged shoals faster than a small yacht could sail.

But there was more. In the north, every headland, channel, loch and narrows was haunted by legends — and a few, by dark superstition.

“Maybe one day you’ll fetch up in Ultima Thule,” my father would tell me. It was he who first told me about Pytheas of Massalia, a Greek who, in 330BC, set out from what is today the Mediterranean coast of France on one of the first recorded voyages to the far north Atlantic. In his book, About the Ocean, which has been lost for more than a millennium but is quoted in other ancient texts, Pytheas described landfalls on the British Isles and possibly Ireland, after which he voyaged northwards for six days to Ultima Thule, which he described as being at the edge of the known world — just a day’s sail from what he called the Cronian (or frozen) Sea — where the nights were very short and in the gelid mists, the earth, sea and air became indistinguishable from each other. The exact position of Thule was lost with Pytheas’s work and although, over the centuries, famed explorers such as Columbus, Sir Richard Francis Burton and Fridtjof Nansen claimed to have found it on coasts as distant as north-west Norway, Iceland and the Shetland Isles, it’s unlikely any of them did. As the contemporary author and Thule researcher, Joanna Kavenna, has written: “Ultima Thule was a land beyond the reach of humans, a place entwined with the outlandish — unipeds, the seven sleepers, a great whirlpool at the Pole, the ocean’s navel.”

Still, the iron-bound coasts and windswept seas that had to be negotiated even to have a chance of reaching it were the birthplace of many of our best-remembered legends, first told in millennia-old languages that still endure.

Barmouth Harbour: 52° 48.3’N, 4°44.4’W Whoever spends a night on Cader Idris will wake up either a madman or a poet — or so it’s said. Given what’s known of modern Welsh poets, how does anyone tell the difference?

Legends swathe the Cader (which means ‘the seat’) as densely as the fog that often obscures Pen Y Gadair, its 893-metre peak. Depending on whom you ask, the southernmost mountain of North Wales’s Snowdonia range is named after either a giant, who kicked three enormous boulders down its slopes, or King Arthur, who is said to have founded his kingdom there, overlooking the black waters of Llyn Cau, a bottomless lake.

For us, the mountain was nothing more than a good landmark for a compass bearing as we fixed our position in Cardigan Bay. We had sailed out with the first of the ebb from the tidal harbour of Barmouth, at the mouth of the Mawddach River in the east of the bay, with the intention of making north-north-westwards across St Patrick’s Causeway, a shallow reef of sand, rock and scree that extends nine nautical miles into the bay, before steering north-west by west towards Bardsey Sound between a long island, Ynys Enlli – first named Bardsey, the island of the bards, by Vikings who associated it with Christian mysticism – and the Lleyn Peninsula. There wasn’t much time. The spring tide was ebbing, the wind was freshening from the south-west and we wanted to clear the causeway’s dangerous shallows while there was still enough water over them.

Like the Cader, the causeway is the subject of disparate myths. For Christians with a fondness for the miraculous, it was the pathway St Patrick walked to Ireland, 85 miles to the west. To the pagan Welsh, it was the remnants of an ancient low-lying kingdom, Cantre’r Gwaelod, ruled by a Celtic king, Gwyddno Garanhir, which was flooded and submerged when a watchman failed to notice that one of its dykes had been breached. All its inhabitants, except a commoner and a young princess, were lost. The locals swear that when the sea is calm, you can still hear the watchtower bells ringing underwater.

The sea is rarely calm along this coast. Unprotected from Atlantic depressions that slow and deepen as they encounter the Snowdonia mountains, the weather can be windy, cold and wet even in summer. Worse, the water is littered with shoals and bars that combine with an unusual tidal range — over four metres difference between mean high and low water during springs — and fast-moving tidal streams to create some of the most hazardous pilotage in Europe. The locals give the worst stretches colourful names, like The Tripods, an area of seething overfalls off the north-east corner of Ynys Enlli — confused, breaking seas caused by a rush of tide over irregular soundings, like the standing waves that churn over large rocks in river rapids. Close by is an open bay named Hell’s Mouth.

We almost lost the boat in The Tripods. We carried a fair wind into Bardsey Sound where bravado tempted me to skirt too close to the overfalls. The wind died. Foaming white claws grabbed at the hull and began dragging it towards the lee shore. I pushed the helm a-lee in the hope of turning the boat seaward and filling the sails with three or four knots of breeze as the tidal stream swept the boat sideways. It wouldn’t respond. Spiralling eddies tugged at the rudder, and short, slab-faced waves broke over the decks, filling the cockpit faster than its drains could empty it. What little breeze the sails managed to catch was shaken from them by the hull’s violent pitching and rolling. The low, grey-green cliffs loomed close above like stone-faced thugs.

Then a stray gust filled the flogging mainsail. The sheets cracked in their blocks as they took the strain. The boat dug its gunwales into the sea and it began to gather way, burying the slender foredeck under green water as it ploughed through the breaking waves. It was only when we were less than a mile from the edge of the overfalls, running north in clear wind towards Caeranrvon, with Ynys Enlli falling astern, did I realise that I still holding my breath. The hand with which I clutched the tiller had cramped with fear.

“Ah, Myrddin’s curse,” an old fisherman I met the next morning on the Caernarvon town quay said when I had told him about our misadventure.

“Who?”

“The English call him Merlin. Legend has it that he’s buried on the island in a castle of glass, along with King Arthur, whose body the old prophet brought there after he was killed at the battle of Camlann. To those who believe it, Ynys Enlli is the Isle of Avalon.”

“Not of the Twenty Thousand Saints?” I asked him. The Welsh monk St Cadfan founded a monastery on Ynys Enlli in AD546 and its renown as a place of pilgrimage in the Dark Ages – Welsh bards referred to it as, “the holy place of burial for all the bravest and best in the land” – drew so many pilgrims, many of whom died there, that it became known as the Island of Twenty Thousand Saints.

The old fisherman shrugged and smiled. “Ah well, it’s like Merlin and Arthur, I suppose. The saints’ remains have never been found either.”

Caernarvon: 53° 08’N, 04° 16’W In the dead of night, it was hard to make out the blinking lights of navigational buoys marking the serpentine channel through the sandbar at the mouth of the Menai Straits. Off the starboard bow, there was the mainland, and the fizz of neon shop signs, halogen street lamps glowing orange, and headlights rising and dipping as cars wound along the main coastal road; there were also the bright spotlights illuminating the crumbling walls of Caernarvon Castle. Off the port bow, on the low shores of the Isle of Anglesey, were more streetlamps and a checkerboard of lighted house windows. There was nothing to do but trust the flooding tide to lift our keel over the shifting sands and carry us into the deeper water within the straits.

We avoided grounding and eventually anchored off a timber public jetty not far past the town. We had intended to sail all the way through the straits on the last few hours of the flood but that would have meant negotiating the reefs in the unlit narrows beyond the Menai Bridge in the dark, a manoeuvre that requires keeping within an oar-length of the eastern shore and regaining the buoyed main channel to Bangor just before the tide begins to ebb. However, piloting the uncertain channel through the Caernarvon bar ‘by touch’ at night, on top of nearly losing my boat in The Tripods in daylight, had sapped whatever nerve I had left.

On the shore opposite where we lay at anchor was the Anglesey village of Tal-y-Foel. From Tal-y-Foel northwards along the same shore to Mol-y-Don, close by the improbably named village of Llanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrndrobwllllantysiliogogogoch (it means, “The church of St Mary in the hollow of white hazel trees near the rapid whirlpool by St Tysilio’s of the red cave”), the inexorable drive westwards of the Roman invasion of the British Isles during the first century AD was almost held to a stand-off by local warriors. In AD61, Gaius Suetonius Paullinus, the brutal Roman commander who would later defeat the famed Celtic queen Boadicea, had decided to eradicate the Druids by overrunning their spiritual home, Insulis Mona — the Roman name for the Island of Anglesey (first named, again, by the Vikings) — and so undermine the resistance of the last undefeated Celtic tribes. At the same time, he could seize control of valuable grain stores to victual his army and of copper mines that would provide the raw material for new armaments.

It was never going to be an easy task. Even Rome’s ingenious military engineers could not bridge the fast-flowing tidal waters between the mainland and the island, and the Celts had proven themselves to be skilled if undisciplined guerilla fighters. Led by Druid priests, who invoked dark, animistic forces to come to their aid, as thousands of Celtic warriors arrayed themselves along the Anglesey shore. Naked, their skin dyed blue from woad, they screamed taunts at the Roman legions across the straits and beat their swords and spears against wooden shields. Their women danced between them, lighting bonfires from burning torches that they waved like battle standards.

If the intention was to strike fear into the enemy, it worked – for a short while. The Roman line was gripped by a wave of panic and, perhaps for the first time in the Empire’s history, an entire legion flinched. But Paullinus rode among them, rousing them to the fight, and as the tide slackened, his infantry crossed the water in boats — his cavalry swam with their horses — under cover of a barrage of fireballs, iron ingots and rocks catapulted onto the opposition from huge ballistae, the Romans’ deadly prototype of field artillery. The battle-hardened centurions slaughtered the Celtic warriors, then took to massacring their families. The Druids and their acolytes were burned alive in their sacred oak groves.

Undaunted, the Anglesey Druids, the last remaining in Britain, along with the Celtic tribesmen who venerated them, rose again 17 years later. This time they faced legions led by Gnaeus Julius Agricola, who had been among Paullinus’s officers. Agricola resolved to eradicate the troublesome Druids once and for all and to subjugate this last pocket of Celtic resistance. His men, like Paullinus’s, crossed the straits by boat and staged a bloody rampage that finally wiped out the Druidic priesthood forever and broke the back of the Celtic resistance.

We set sail from Caernarvon early the next morning. The waters, stained a coppery brown by tannin, were mirror-like and still, and reflected the shadowy boughs of gnarled old oaks that overhung the shore. Drifting northwards on the flood tide to the Menai Bridge, I sat cross-legged on the cabin-top and tried to identify the few, stark memorials of the Druids’ last stand on a 1950s Ordnance Survey map: a rise called Bryn-y-Beddau, the Hill of Graves, where the Celts buried their dead, ‘the Field of The Long Battle’ and ‘the Field of Bitter Lamentation’ outside the village of Llanidan, and finally Plas Goch, ‘the Red place’. In the windless silence, it was easy to imagine it as an island of restless ghosts.

The Skelligs: 51° 4’'N, 10° 3’’W We plotted a course north from the Skellig Islands, seven nautical miles off the coast of County Kerry, to Achill Head, the westernmost island extremity of County Mayo. It spanned more than 140 nautical miles of open ocean across the wide gulf of the Irish west coast. Off Achill Head, we would alter course again and with luck, carry the prevailing south-westerly wind all the way to Eilean Barraigh, in the Western Isles of Scotland, the so-called Outer Hebrides.

Skellig Michael, or Great Skellig (from the Gaelic sceilig or sea rock), the largest of the two Skellig Islands, is a forbidding spire of slate-grey rock that thrusts 215 metres straight out of the Atlantic. It looked like the peak of an underwater alp, materialising out of a grey sea mist to loom less than a mile ahead of us as we headed a south-going tidal stream in a light breeze. As we closed it cautiously, we could just make out some of the 670 steps carved into its face to form what the writer Geoffrey Moorhouse once described as “a stairway to heaven”. The steps actually lead to the remains of an abbey established in AD560 by St Fionan, a follower of St Brendan, with whom, legend has it, Fionan sailed from the Aran Islands, further north, all the way across the North Atlantic to Nova Scotia in an open, leather-hulled curragh. It was on the peak of Skellig Michael where, a reference from the third century recalls, Daire Domhain, the legendary ‘King of the World’, rested before an epic battle of a year and a day against the giant, Finn McCool (Fionn mac Cumhal), and the Fianna, a band of noble, bardic warriors. It was here too that St Patrick, aided by an apparition of the archangel St Michael, banished the last venomous snakes from Ireland for all time.

Skellig Michael’s desolate grey slopes are pocked with crude, igloo-like hovels — the rough-hewn stone walls are nearly a metre thick — and small cells carved into almost sheer rock faces. There, for 600 years, hermitic monks managed to eke out a hard-scrabble existence comprising prayer, scholarship and the routine chores of survival.

We ghosted between the ragged peaks of Great and Small Skellig, stood out to sea. Another few hours brought the coast of County Galway abeam, a green-black smear low on the eastern horizon. Here, with a simple running fix plotted on a chart in pencil, I closed the circle of a voyage that had began in the 1850s, when both my paternal great-great-grandparents and their families sailed from these shores to Portland in Victoria, Australia. None was a seafarer, and the long voyages they made aboard three-masted sailing ships, south through the Atlantic and east about the Cape of Good, Hope to run hard before the relentless gales and high seas of the Roaring Forties, were likely the first time any of them had ever ventured on the ocean. Up to their eyes in debt as tenants on small, rural lease holdings, near inland villages where their descendants still live today, they must have clung to the hope that their new lives as free settlers — as goldminers, farmers, graziers and policemen — in what was, not long before, just a far-flung English penal colony, would be better than the ones they had left behind.

My reasons for returning — and for sailing even further northwards, to islands long abandoned by whole communities that, after several generations, were finally defeated by the isolation and hardship of these unsheltered, gale-lashed shores — were less clear. My voyage was a voyage of hope and discovery, not to new lands, but to lands so old that it was as if there was never a time in which they had been unknown, unexplored. And somewhere between one distant landfall and the next, there was a vague chance the past might help me to decipher an incomprehensible present.

First published, with the title In Ancient Wakes, in Griffith Review, Australia, 2005, and selected by Robert Dessaix (editor) for Best Australia Essays 2005, published by Black Inc.

#england#wales#scotland#ireland#atlanticocean#sea#sailing#kingarthur#merlin#myths#history#memoir#voyage#celts#romans

1 note

·

View note

Video

youtube

Shetland Day 4 - We’re exploring the island of Unst and hiking up to see the northernmost point of Britain.

#unst#shetland#scotland#vikings#footage#cliffs#muckle flugga#skidbladner#history#archaeology#broch#longhouse#island#sea#gannets#travel vlog#youtube

74 notes

·

View notes

Video

Ancient Scotland from John Duncan on Vimeo.

facebook.com/johnduncanfilmmaker/ instagram.com/johnduncanfilmmaker/ john-duncan.co.uk

Having spent the past seven months travelling all over Scotland to shoot my new film, ANCIENT SCOTLAND, I’ve never been more proud to call this country home.

Shot at twenty one stunning locations from as the far north as Muckle Flugga at the very top of Shetland to the prehistoric wonder of Britain’s highest sea stacks near St Kilda, some 40 miles west of the Outer Hebrides.

As the third in a series of Scottish aerial films, I wanted to continue the progression of theme. My first film, Beautiful Scotland, was really just a collection of beautiful shots. My second, Wild Scotland, embraced the wild theme of this country, featuring many of our wild animals. So for this third instalment I had to look deeper at what defines Scotland for me. It soon dawned on me that Scotland has so much of the ancient about it, not just in terms of architecture but far older geology (a field of study which has its roots here). This led to a shot list ranging from incredible, imposing castles through to totemic sea stacks and the looming presence of St Kilda, a citadel of rock standing proud amidst the crashing maelstrom of the Atlantic which was inhabited until the 1930s.

Having already shot two films in Scotland, I’d already picked the low hanging fruit of the more accessible locations so the logistics of reaching and filming this film were definitely more challenging. Each shot involved some kind of, often physically demanding, adventure. Notable examples include a four day round trip to Shetland to capture 10 seconds of footage; the challenge of getting to the wildly remote sea stacks near St Kilda; and weathering 8 hours of miserable weather in a bivvy bag on a ridge in Skye, just to be there for sunrise.

The process of filming this has led to personal experiences which defy superlatives, not least the simple, awe inspiring, moments surrounded by silence as the sun rises over the horizon. Being on top of a mountain when the sun rises is an experience you will never forget.

Scotland is truly a country made for those who love the outdoors in its wonder. Get out and explore it.

BEHIND THE SCENES - vimeo.com/285829099

Shot on DJI Inspire 2 with X5S and X7, PRORES 422HQ

For footage licencing enquiries please email – [email protected]

** THIS FOOTAGE MUST NOT BE USED WITHOUT PRIOR PERMISSION **

0 notes