#Mosul Assyria

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

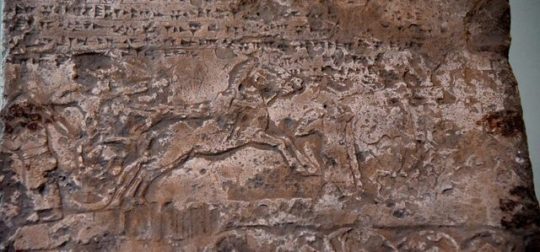

women deported from a babylonian city | c. 668-627 BCE | courtyard j of the north palace at nineveh (modern day mosul, iraq), assyrian

"The deportation policy that the Assyrian rulers followed constantly, and on a large scale, had two purposes: to repopulate the Assyrian cities and countryside, whose men had been drained off in numerous military campaigns; and to crush the conquered peoples’ national and cultural identity. This was especially the purpose of mass deportations from one province to the other and vice versa."

in the museo di scultura antica giovanni barracco collection

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

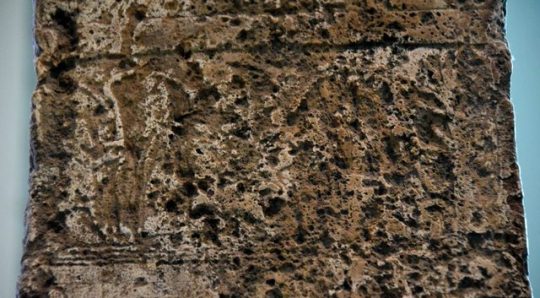

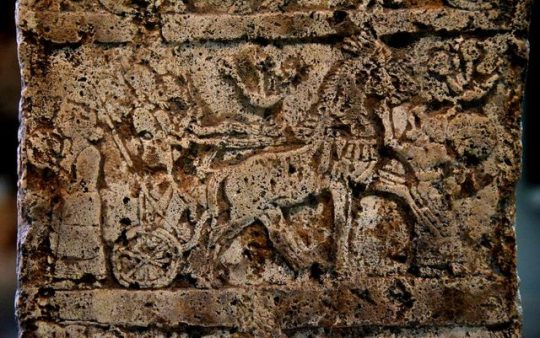

Detail of the bronze Balawat Gates, showing Neo-Assyrian king Shalmaneser III in a chariot with a group of Assyrian archers. The Balawat Gates are a set of decorated bronze gates dating from the reigns of Ashurnasirpal II (r. 883–859 BCE) and Shalmaneser III (r. 859–824 BCE). They show the military exploits of these Neo-Assyrian monarchs in a detailed and narrative style. They are celebrated as some of the most beautiful and important pieces of Assyrian art found to date. These doors were the gateways to several building at Balawat, ancient Imgur-Enlil. The city lay 10 kilometers up the Derrah river, a branch of the Tigris, and was founded by Ashurnasirpal II. The town was situated along the Neo-Assyrian Royal Road between Nineveh and Arrapha. Shalmaneser III continued developing the settlement, but Balawat was eventually sacked some two and a half centuries later by Medes, Babylonians and Scythians. The remains reside currently in the British Museum and Mosul Museum, with other smaller sections to be found in several other museums.

#assyria#assyrian history#assyrian empire#mesopotamia#ancient near east#archeology#british museum#ancient iraq#iraq#mosul#kirkuk#ancient archeology

78 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

No Nation is Too Big to Fail (Nahum 1) - A daily Bible study from www.He...

#youtube#Sin Wickedness Judgment Punishment Israel Assyria Nineveh Iraq UnitedStates America Prophecy Nahum Mosul

0 notes

Text

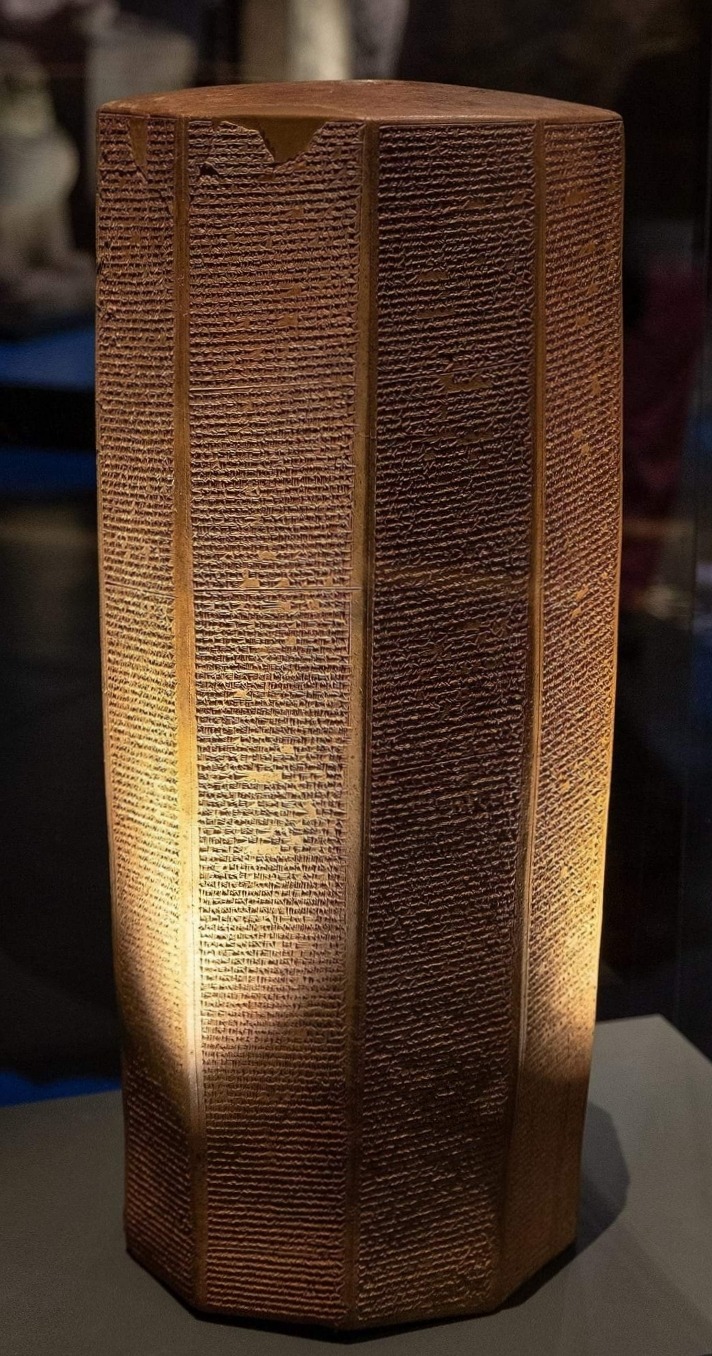

Rassam Cylinder, a ten-sided clay cylinder that was created in c. 643 BC, during the reign of King Ashurbanipal (c. 685 BC - 631 BC) who ruled the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 669 - 631 BC.

It was discovered in the ancient Assyrian city of Nineveh, near Mosul, present-day Iraq, by Hormuzd Rassam (3 October 1826 - 16 September 1910) in 1854.

In over 1,300 lines of cuneiform text, the cylinder records nine military campaigns of Ashurbanipal, including his wars with Egypt, Elam and his brother, Shamash-shum-ukin.

It also records his accession to the throne and his restoration of the Palace of Sennacherib.

The cylinder is the most complete chronicle on the life of Ashurbanipal.

There are some extracts from the cylinder below:

"I am Ashurbanipal, offspring of Ashur and Bêlit, the oldest prince of the royal harem, whose name Ashur and Sin, the lord of the tiara, have named for the kingship from earliest (lit., distant) days, whom they formed in his mother's womb, for the rulership of Assyria; whom Shamash, Adad and Ishtar, by their unalterable (lit., established) decree, have ordered to exercise sovereignty.

Esarhaddon, king of Assyria, the father who begot me, respected the word of Ashur and Bêlit-ilê (the Lady of the Gods), his tutelary (divinities), when they gave the command that I should exercise sovereignty.

In the month of Airu, in the month of Ea, the lord of mankind, the twelfth day, an auspicious day, the feast day of Gula, at the sublime command which Ashur, Bêlit, Sin, Shamash, Adad, Bêl, Nabû, Ishtar of Nineveh, Queen of Kidmuri, Ishtar of Arbela, Urta, Nergal, Nusku, uttered, he gathered together the people of Assyria, great and small, from the upper to (lit., and) lower sea.

That they would accept (lit., guard) my crown princeship, and later my kingship, he made them take an oath by the great gods, and so he strengthened the bonds (between them and me)....

By the order of the great gods, whose names I called upon, extolling their glory, who commanded that I should exercise sovereignty, assigned me the task of adorning their sanctuaries, assailed my opponents on my behalf, slew my enemies, the valiant hero, beloved of Ashur and Ishtar, scion of royalty, am I.

Egyptian Campaign:

"In my first campaign I marched against Magan, Meluhha, Taharqa, king of Egypt and Ethiopia, whom Esarhaddon, king of Assyria, the father who begot me, had defeated, and whose land he brought under his sway.

This same Taharqa forgot the might of Ashur, Ishtar and the other great gods, my lords, and put his trust upon his own power.

He turned against the kings and regents whom my own father had appointed in Egypt.

He entered and took residence in Memphis, the city which my own father had conquered and incorporated into Assyrian territory.

A swift courier came to Nineveh and reported to me.

At these deeds, my heart became enraged, my soul cried out. I raised my hands in prayer to Ashur and the Assyrian Ishtar.

I mustered my mighty forces, which Ashur and Ishtar had placed into my hands. Against Egypt and Ethiopia, I directed the march."

Rassam Cylinder records the reign of Ashurbanipal until c. 645 BC.

The latter years of his reign are poorly recorded, probably due to the fact that the Neo-Assyrian Empire was plagued with troubles.

One of Ashurbanipal's last known inscription reads:

"I cannot do away with the strife in my country and the dissensions in my family; disturbing scandals oppress me always.

Illness of mind and flesh bow me down; with cries of woe I bring my days to an end.

On the day of the city god, the day of the festival, I am wretched; death is seizing hold upon me, and bears me down..."

Rassam Cylinder is currently on display in the British Museum.

A truly remarkable, yet biased, insight into the reign of Ashurbanipal and the world in which he lived.

📷: © Anthony Huan

#Rassam Cylinder#King Ashurbanipal#Neo-Assyrian Empire#Nineveh#Hormuzd Rassam#clay cylinder#cuneiform text#Palace of Sennacherib#British Museum#Assyria#ancient civilizations#Iraq#assyriology#military campaigns#cuneiform cylinder#cuneiform#writing systems

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

Worthy Brief - October 28, 2024

Have the heart of God!

John 3:17 For God did not send His Son into the world to condemn the world, but that the world through Him might be saved.

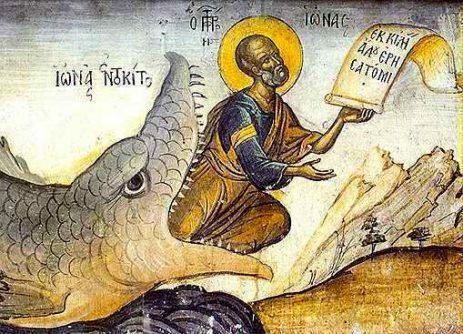

For the next week or so we'll be looking closely at the life of Jonah the prophet. Jonah was told to "preach against the city of Nineveh", that was in the ancient kingdom of Assyria. Nineveh was a major city on the banks of the Tigris River about 500 miles north and east of where Jonah was; located on a contemporary map in modern Iraq, about 300 miles north of Baghdad. Archaeologists have found the ruins of ancient Nineveh right outside the Iraqi city of Mosul.

When God said Nineveh was wicked, he wasn’t kidding. Nineveh was the capital of Assyria, the most powerful empire in the world in that day. The Assyrians had a reputation for cruelty that is hard for us to fathom. Their specialty was brutality of a gross and disgusting kind. When their armies captured a city or country, unspeakable atrocities would occur. Things like skinning people alive, decapitation, mutilation, ripping out the tongues, making a pyramid of human heads, piercing the chin with a rope and forcing prisoners to live in kennels like dogs. Ancient records from Assyria boast of this kind of cruelty as a badge of courage and power. Sad to say, the saying – "History repeats itself", truly fits in this case!

So we ought to remember this context when we consider God's command to Jonah, and the prophet's response. Suppose God spoke to you today, "Go and preach the gospel to the Islamic State! Or go and preach to the Taliban! " Think you might respond, "Ahem God – they're terrorists! Let's nuke 'em; send 'em right where they belong!" But the heart of God is merciful. He wants to bring people to repentance so He can forgive, rather than bring judgment. He desires to save…even the most wicked and hardened individuals!

So here's what I think: There’s a little Jonah in all of us and a whole lot of Jonah in most of us. We're praying for the Christians fleeing Afghanistan, Syria, Iraq, and Turkey – but what about the wicked terrorists who are killing, torturing, and persecuting them? Do you have an "Assyrian" in your life? Is someone truly worthy of your hatred? Rather than pray for him, you'd be glad for him to meet God face to face today? Our Heavenly Father rebuked Jonah the prophet for his own hardness of heart and lack of compassion. So the story of Jonah is about the heart of God, who desires all men to be saved. He wants us to have the same heart.

Your family in the Lord with much agape love,

George, Baht Rivka, Obadiah and Elianna (Palm Beach, Florida)

Editor's Note: Feel free to share any of our content from Worthy, including Devotions, News articles, and more, on your social platforms. You have full permission to copy and repost anything we produce.

Editor's Note: During this war, we have been live blogging throughout the day -- sometimes minute by minute on our Telegram channel. https://t.me/worthywatch/ Be sure to check it out!

Editor's Note: Dear friends — we are going to be heading WEST!!! Now booking in the following states: Florida, Alabama, Mississippi, Texas, and Arkansas …. If you know Pastors, Rabbis or Ministry Leaders who might be interested in some powerful Israeli style Hebrew/English worship and a refreshing word from Worthy News about what’s going on in the Land, please let us know how to connect with them and we will do our best to get you on our schedule! You can send an email to george [ @ ] worthyministries.com for more information.

0 notes

Text

MESOPOTAMIA IS THE CRADLE OF HUMAN CULTURE

In modern Iraq, with its capital in Baghdad, in the valleys of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers, which originate in Turkey and have turned this territory into the cradle of human civilization, lies Mesopotamia, also known as "Agam-Nahayim" — Syria between two rivers. In the north, along the upper course of the Tigris, is Assyria, and in the south, between the two rivers extending to the Persian Gulf, lies Babylonia.

This region reached its greatest cultural prosperity during the Assyrian and Babylonian rule. After a long period of decline, it once again experienced a cultural revival during the Arab conquest, becoming the center of the Caliphates. However, with the attacks of the Seljuks (Turkic-Tatars), the country gradually declined, turning into a partially deserted land, as we see today. For a long time, Egypt was considered the cradle of human civilization, and references to Mesopotamia as such were found only in the Bible. It was only after archaeological discoveries made by the French researcher Paul-Émile Botta that views on this matter began to change. The materials he uncovered indicated that Mesopotamian culture was, if not older, at least as ancient as Egyptian culture.

Paul-Émile Botta, a French physician, served in the 1830s under the ruler of Egypt, Muhammad Ali, and collected insects during an expedition to Yennaar. In 1840, he became a consul in the city of Mosul, located on the upper Tigris. The region was known for its numerous mysterious mounds, which resembled the ruins of grand buildings, and Botta became increasingly interested in them. Despite being a doctor, not an archaeologist, his diplomatic skills, knowledge of the local language, and persistence helped him achieve his goal. He collected ancient artifacts by asking local inhabitants, though he often received vague answers that these items could be found anywhere because "the great Allah scattered them throughout the land."

One day, Botta began excavations near the mound of Kuyunjik, but after several months of hard work, he found nothing of great significance except for a few broken bricks with cuneiform inscriptions and some damaged sculptures. However, a chance encounter with a local led him to a new site where excavations brought significant archaeological discoveries. This event immortalized Botta’s name in the history of archaeology.

Botta uncovered the remains of a civilization that thrived for almost 2,000 years and had been buried beneath the earth for over 25 centuries. The palace walls were decorated with mysterious inscriptions, images of bearded men, winged creatures, and strange animals. Each day of excavation brought new discoveries. The Assyrian capital of Nineveh and the palaces of Assyrian kings were unearthed. From 1843 to 1846, Botta conducted excavations despite harsh weather, local resistance, and opposition from the Turkish governor.

Botta’s discoveries soon gained global attention. Archaeologists identified the uncovered palace as that of King Sargon, mentioned in the Bible. It was a summer palace, similar to Versailles or Sanssouci, built in 709 BC after the conquest of Babylon. Botta uncovered not only walls but also ornate gateways, lavish rooms, passageways, and remains of towers. His discoveries confirmed the existence of the ancient culture in Western Asia described in the Bible, and revealed invaluable cultural treasures from a forgotten civilization.

The material was taken from publicly available online sources

0 notes

Text

Mosul discoveries brought to light in new documentary

In 2014, Mosul fell under the control of ISIS (also called Daesh). During its three-year reign, the militants destroyed artifacts and buildings saying they were forms of idolatry.

As the CBC news channel explains, they also targeted sites for looting and to get attention, filming the destruction and sharing it in propaganda videos online.

But ISIS's actions inadvertently created opportunities. Sifting through the wreckage after ISIS's occupation, archaeologists have gained new insights into this great ancient city.

The city of Mosul in northern Iraq encompasses what was once Nineveh, the largest city in the seventh century BC and capital of Assyria, the world's first superpower.

Lost World of the Hanging Gardens looks at new discoveries in the ashes of ISIS's occupation and explores whether Nineveh was in fact the site of a lost wonder of the world — the Hanging Gardens of Babylon.

#iraq#iraqi#manchester#london#uk#baghdad#liverpool#scotland#usa#canada#documentary#cbc news#mosul#tv and film#tv and movies#germany#education#learning#higher education#teachers#schools#hussein al-alak#teaching#research#artists#artist on tumblr#art history#world history#history lesson#british museum

0 notes

Text

Nineveh

Capital of the kingdom of Assyria, on the left bank of the Tigris River, in ancient Mesopotamia, Nineveh, whose name meant "beautiful", is located near the current city of Mosul, in northern Iraq.

In the Bible, Jonah is sent to Nineveh to convert its people and thus avoid its destruction (Jonah, 3, 1-10). Later, it is the prophet Nahum who describes the ruin of Nineveh, which seems to have taken place around 612 BC. Ç.

The Assyrians, traditionally seen as a conquering and cruel people, were builders of a civilization that left important marks on the ancient world, visible in their cities, such as Nineveh, Assur and Nimrud. Decayed from the 7th century a. C., after more than fifteen centuries of conquests and splendor.

Father António Vieira, in the Sermon of Saint Anthony to the Fishes, reminds Jonas that, in the episode of the Bible, "The men threw him into the sea to be eaten by the fish, and the fish that ate him, took him to the beaches of Nínive , that he might preach there and save those men."

instagram

0 notes

Text

Archaeologists in northern Iraq, working on the Mashki and Adad gate sites in Mosul that were destroyed by Islamic State in 2016, recently uncovered 2,700-year-old Assyrian reliefs. Featuring war scenes and trees, these rock carvings add to the bounty of detailed stone panels.

There is evidence of occupation at the site already by 3,000 BC, an era known as the late Uruk period. But it was under King Sennacherib (705-681 BC), son of Sargon and grandfather of Ashurbanipal, that Nineveh became the capital of Assyria, the greatest power of its day.

Traditionally, the Assyrian capital was Ashur, but in the 800s BC the political capital had been moved to Kalhu (Nimrud). Sennacherib’s father, Sargon, had subsequently built himself a completely new capital city.

Nineveh became synonymous with Assyrian power. When it subsequently fell to a coalition of Babylonians and Medes in 612 BC.

#history#archeology#archeologicalsite#discovery#ancient#ancient mesopotamia#ancient assyria#city wall

0 notes

Text

Libraries Around the World: Nineveh, Assyria (now Kuyunjik, Iraq)

Royal Library of Ashurbanipal

Now located just off of Mosul, Iraq, the library was named after Ashurbanipal, the last great king of the Assyrian Empire.

It was originally run in the 7th century and housed around 30,000 clay tablets.

As of 2002, the British Museum has had a project with Mosul University to digitize in high def the entire archive so people all over the world can enjoy it.

By the way, this is how Nineveh is spelt in Assyrian cuneiform: 𒌷𒉌𒉡𒀀

#libraries around the world#iraqi libraries#iraq#librarylife#libraryland#assyria#mosul#mosul university#british museum#cuneiform#libraries

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

“(Lament) for the mighty one my spouse who liveth no more.

_ _ _ _who liveth no more; for the mighty one who liveth no more

_ _ _ _who _ _ _ liveth no more; for the mighty one who liveth no more

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ my spouse who liveth no more

_ _ _ who liveth no more

_ _ _ _ great god of the heavenly year who liveth no more.

Lord of the lower world who liveth no more.

Lord of vegetation, artificier of the earth who liveth no more.

The shepherd, the lord, the god Tammuz who liveth no more.

The lord who giveth gifts who liveth no more.

With his heavenly spouse he liveth no more.

(The producer of) wine who liveth no more.

Lord of fruitification; the established one who liveth no more.”

- A Hymn to Dumuzi/Tammuz [Transliteration and Translation of Aramaic cuneiform Texts from the British Museum, discovered in the Royal Library of Ashurbanipal in the ancient capital city of Nineveh, Assyria (now located in modern-day outskirts of Mosul, Iraq)]

(Note: While worshippings, mythologies & cult practices of Dumuzi have been dated back to the early years of Sumerian civilization of Ancient Mesopotamia - when early humans began to settle down and develop one of the world’s first and most complex systems of agricultures, his cult were later spread to the Levant and Greece & integrated into their cultures, under the new names of “Tammuz” and “Adonis.”)

Revisiting and tried to expanding one of my drawings 2 years ago that I made of Aphrodite and her mortal lover, Adonis; with the goddess of spring and nature, fertility crops and queen of the underworld, Persephone belongs to @coloricioso. The backgrounds were based on various natural locations and ancient Greco-Roman ruins sites of Cyprus, Syria, Palestine and Lebanon; which often have sacred syncretic myths associated with Aphrodite and Adonis themselves. (Below here are the Greco Roman ruins that I took inspiration of: Baalbek/Heliopolis, Lebanon; Tadmur/Palmyra, Syria; Scythopolis/Beit She’an or Beisan, Palestine; Salamis, Cyprus)

#ancient greek#ancient near east#near eastern mythology#tammuz#inanna#Inanna descent to the underworld#dumuzi and inanna#greek mythology#aphrodite#adonis#persephone#venus#prosepina#oh to be described as a mortal who are more beautiful than the gods#and falling in love by some of them as well#i do had to say that the goddess aphrodite herself do have a good taste in both men and women as well#Eastern Mediterranean and Middle Eastern guys do be hitting different#than all of white American and north European casts in here

245 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rawê - Gîwergîs Selmo | Darên Bi tenê" { YouTube }

youtube

(الفلكلور والغناء الآشوري

– The folklore & Assyrian singing)

History

Tribal and Folkloric Period .

Music, is omnipresent in the village scene. A “Musician” is not necessarily a professional, and whoever can sing in any manner is considered a “singer”. Most of the time, music is learned by ear. The villagers lead a hard life, but whenever there is an opportunity, they love to make music or listen to it

Village music may be categorized, basically, into four groups: Local secular music not related to specific occasions; functional music; religious music; music adopted from other areas

Here are few types of tribal Assyrian Music that has survived to this day, especially in the Assyrian villages and towns of Northern Iraq, southeast Turkey, northwest Iran and northeast Syria

Rawey: A mostly love songs with a story-tale structure, which may include themes about daily life, suffering and pain

Diwane: Sung in gatherings and meetings; lyrics cover aspects of life such as, working in the fields, persecution, suffering, religion

Lilyana: Wedding songs usually sung by women only, especially for the bride before leaving her home to get married. Also sung for the bridegroom the day before his wedding by his family and relatives

Dowlah and Zornah: These are two traditional music instruments, literally meaning a drum and wind-pipe (or flute). They are played together, either with or without singing in many ceremonies such as weddings, welcoming and funerals (however, for funerals played for unmarried men, they are accompanied by singing)

Tambura: Another tribal music instrument, a string instrument with long neck, originated in ancient Assyria, discovered being depicted on carving from South Iraq from UR to Akkad and Ashur. Albert Rouel Tamraz is a famous Assyrian Singer from Iraq who played this instrument and sung many beautiful folkloric songs accompanied by hand-drum (tabla)

It was in the Assyrian homeland north of Mosul that people started to write the modern Syriac vernacular more than two hundred years before the earliest British missionaries, although the earliest records of the Syriac language date from 5th century BC Achaemenid Assyria. The earliest dated text is a poem written in 1591. This makes early Neo-Syriac literature a contemporary of Jewish Neo-Aramaic literature from roughly the same region, dating back to the late 16th century

The Neo-Syriac literature which existed before the arrival of British and American missionaries consisted mainly of poetry. This poetry can be divided into three categories: stanzaic Hymns, dispute poems, and drinking songs. Of these three categories, only the hymns, which in Neo-Syriac are termed duriky; and which can be seen as the equivalent of the Classical Syriac madrase, can usually be traced back to individual authors.[1]

https://en.wikipedia.org

***************************************************************

ZMIRYATA-D RAWE

Professor Fabrizio Pennacchietti

University of Turin

Over the last few years, amongst the Aramaic-speaking minorities of the Near East and the countries of Diaspora, an impressive movement of intellectual rebirth has been making its presence felt. In Eastern Neo-Aramaic or Neo-Syriac (Sureth)-the mother tongue of both Christians and Jews of the region extending from the basin of the Botan-Su, a tributary of the Tigris in Turkish Mesopotamia, down to the western bank of Lake Urmia in Iran- the literary activity of the “Assyrians” and the “Chaldeans” of Iran and of American Diaspora deserves note. However, it is above all in Iraq where the Neo-Aramaic cultural reawakening has begun to assume microscopic dimensions

What is disheartening is the fact that only an insignificant minority can still read and write the so-called Nestorian alphabet. However, Neo-Aramaic, as a spoken language, continues to maintain a noteworthy vitality, especially among the Assyrians

Still in this regard, it must be observed that the intense immigration of the Aramaic-speaking population of the Persian Azerbaijan, after the tragic events of World War I extensively influenced the dialects spoken by the Kurdistan Assyrians who in turn became the victims of drastic displacement. Their descendants, in particular those living in Baghdad, Mosul, Kirkuk, and Basrah, have generally opted for a dialect similar to that of Urmia except for the absence of its typical “Vocal Harmony” or “Synharmonism” . Conversely, the Assyrians of Urmia have willingly adopted the picturesque folklore of the Assyrians of Kurdistan in the form of sane variegated festive costumes, and particular dance steps, not unlike those used by the Kurds

Unfortunately, the disappearance of the dialects of Kurdistan Assyrians is tied up closely with the disappearance of the more authentic contents of Nestorian folklore, like the love songs, the wedding hymns, and the war songs that since time immemorial have been handed down from one generation to the next among the mountain Christians. It is a well-known fact that only Kurdistan Nestorian population groups and above all those who enjoyed equal status with the Moslem Kurds- i.e., the ashiret or warlike tribes originally of the Turkish vilayet of Hakkari- have known how to keep their own fo1k1.ore intact from Arabic, Kurdish, Turkish or Persian influences

This heritage, on the way to extinction, merits being gathered and studied, but presently it is rather difficult to find reliable informants. The younger generation treats it all with indifference, as if it were old-fashioned, while among the old people, only a few know how to explain the sense of an old song or how to give the location of this or that place-name in an ancestral territory that no one has had access or reason to revisit since World War I

Over thirty years ago, the well-known French [Kurdologist], Thomas Bois, voiced the impression that no one among the Assyrians knew how to sing a love song in his mother tongue any more. On looking further back into the past, we can see that research conditions were even less favorable than at the present time. The insecure nature of communication routes, along with the suspicious nature of the Nestorians, made the task of gathering their oral traditions quite a risky undertaking. The few Westerners who ventured into their inaccessible mountain fastnesses either visited them hurriedly, or, as was the case with some American and English missionaries, were moved to do so almost always because of religious motives

The fact remains that whatever meager evidence of popular Assyrian poetry that we have, has never been gathered on the spot in genuine Nestorians surroundings, but rather in marginal areas or even in far distant localities

In 1869, in Damascus, the Semitist and Kurdologist Albert Socin chanced to meet a poverty-stricken Nestorian basket-weaver, a certain Isho by name, son of Dustu from the village of Talana, one of the villages of the Ge1u tribe. Like most of his fellow tribesmen who lived in the poorest and highest territory of the inaccessible mountain Massif that extends form the high basin of the Great lab down to the borders of Iran, the basket-weaver had left his village after 13th September, the Feast of the Cross, and would not return there until the beginning of the following May, after the springtime thaw, and after having wandered all over the Near east. Iso, who other than the Neo-Aramaic dialect of Gelu knew only Kurdish, very willingly dictated two stories to Socin, as well as 16 extremely brief poetic pieces each, composed of a verse made up of three septenary monorhymes

This kind of verse form was already known: it had already been noted in learned Neo-Aramaic poetry about 1600. New, instead, seemed the “literary” form of these tiny compositions with crystal-clear images of mountain life, like rapid sketches, that relayed an amorous message, or described an action born of melancholy, pride, passion, peevishness or good-willed derision

The following year, 1870, Albert Socin visited the Chaldean villages of the plain land at the foot of the mountains to the Northwest of Mosul: Telkef, Alqosh, Dehok and Qasafirr. Here, his curiosity still earnest due to his Damascus encounter, the German orient list expressly asked if re could hear sane popular poetry recited. In the mar Yaqo convent of the French Dominican fathers at Qasafirr, Socin’s crave was quenched to his great surprise by the blind rhapsodist who had just finished dictating to him a penitential sermon by the poet Toma Singari. The blind cantor, believing him to be a priest, held as roost unbecoming Socin’s interest in the kind of poetry best regarded as somewhat immoderate. Socin, incidentally, was never to know that the old cantor was no other than Dawid Kora of Nuhadra (who died at Mosul in 1889), of whom numerous religious hymns and enchanting verse fables have been published. “Blind David” was the most famous Neo-Aramaic poet of his day

Socin’s collection of popular poetry was a rather full one, and was published under the title of Fellihilieder, “Songs of the Fellihi”, that is, of Christian villagers of the plainland, as the Moslems of the nearby city of Mosul call them. How could these songs be defined? Socin liked to call them Schnadahupfl, as if they had something in common with the songs Bavarian peasants sang to accompany the rhythms of group dancers. However, the German scholar did not lose sight of the fact that these verses had not originated on the plainland. Disguised by the local dialect, in fact, too many expressions and words of Kurdish derivation appeared, far more familiar to Nestorian mountain folk than to Cl1aldean villagers who, unlike the Assyrians, fell under the influence of Arabic. Fran this re deduced that they really reflected the folklore of the people of the highlands, in particular the Assyrians of high Kurdistan, “die das Hochgebirge bewohnenden Aramaer” , which were reminiscent of the recitations by the basket-weaver of Gelu, whom he had net in Damascus the year before. Furtherroore, this tradition must have been extremely old, for at the time of his visit it had already lost much of its original meaning, both among the Nestorians of Persia and Jacobites of Tur ‘ Abdin, in Turkish high Mesopotamia

A journey, which I made at Eastertime, 1972, through the province (qada’) of ‘Amadiya about fifty kilometers northeast of Dehok, allowed me the opportunity of establishing that oo1y a small part of the compositions collected by Socin more than a century ago were, in fact, destined for the dance. In the Nestorian village of Bebede, a few kilometers west of ‘Amadiya, I happened to be invited to a wedding reception (xlula), at which I was able to listen to the execution of love songs, called zmiryata-d rawe, which corresponded exactly to those collected by Socin

They belonged to a song form we can describe as amoebaean. While on the threshing floor, the young men and the girls, linked hand in large dance circles, followed the obsessive rhythm of a drum “dahula” and a fife “zurna” , the older guests, gathered together in the diwanxana around the wedding couple, formed two groups and, in turns, started to sing a verselet with a strangely archaic tune. The melodic beat was repeated three times and embraced each line as well as the first accented word of the following line, which means that each word was pronounced twice. It had a modal tune, achieved by means of using chromatics at small intervals, executed with a surprising speed. You had the impression that the width between the highest note and the lowest never exceeded the interval our major sixth would make, even if the most important part of this tune appeared to be limited within the span of a major fourth

Once the stornello was finished, those present showed their appreciation as to the choice of the theme and its execution by singing out a series of stressed (o)’s that finished up on a series of high and extremely sharp (iii)’s. At this point, the second group of singers started the stornello that they considered as being more appropriate to go with the preceding one, and in the end, waited for the applause of the bystanders. This give-and-take continued for hours, with short intervals here and there for something to eat, and to drink a sort of local grappa (eau-de-vie)

In effect, in Socin’s collection the zmiryata-d rawe constitute the major type document. However, besides these stornelli, one can find extracts of songs of a different nature and of wider validity: fragments of a warlike song about the brave ‘Awdiso, and portions of qassityata, verse tales, which are singable in co-ordination with dancing

Upon my return to Baghdad, I looked about for someone who could recite me some songs like the ones I had heard at Bebede. After various fruitless attempts amongst Assyrian city-dwellers -but, unfortunately, they had been city-dwellers for too long – I turned to those of more recent arrival from the district of Barwari Bala, a little more to the North of ‘Amadiya. It was in this way that I realized that the district (nahiya) of Barwari Bala and part of the neighboring districts represents the last strip of Kurdistan territory still populated by autochthonous Nestorians. These are the sons and grandsons of those who, abandoned the area at the end of 1914, and returned by 1920

I finally chose as my informant one of the few survivors of the tragic exodus of 1914: Gewargis, son of Bukko, son of Muse. Born about 1897 at ‘Ehnune/Kani Masi (“the Spring of Fish”), the main village in the Barwari Bala district, Gewargis had lived there with various interruptions until a little after the outbreak of Kurdish-Arab hostilities on 11 November 1961

This austere and strong, venerable old man, dictated to me only these zmiryata-d rawe that he held becoming for a man of his age and reputation. Alas, the number we know of such rawe is terribly limited

Notes

Those who would like to expand their reading on this particular subject are invited to consult my original article “Zmiryata-D rawe

Stornelli degli Aramei Kurdistani”, published in Italian with full notes and comments in Scritti in onore di Guiliano Bonfante, pp. 639-663, Brescia (Italy), Paideia Editrice, 1976

Concerning the word Rawe, which recurs several times in my original text, I had written that, unfortunately, its etymology eluded me. After further investigation, however, I have been able to determine its derivation once and for all. The word Rawe canes from Arabic Rawiy ( ), indicating “the letter which remains the same throughout the entire poem and binds the verses together, so as to form one whole ( ) to bind fast”, cf. W. Wright, “A Grammar of the Arabic Language”, vol. II, Cambridge, At the University Press, 1967. Section 194, p. 352

‘Therefore, banda-d rawe means, a monorhyme strophe and zmiryata-d rawe means monorhyme songs

As for the Italian word stornello, also found, several times in the original article, there is this to say: this kind of poem, ” a short (usually three-lined) popular Italian verse form” (See Chambers’ 1Wentieth Century Dictionary), is known by this Italian name even in English, and so I have chosen to retain it here

Published in “JOURNAL OF ASSYRIAN ACADEMIC SOCIETY 1985-1986 .

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

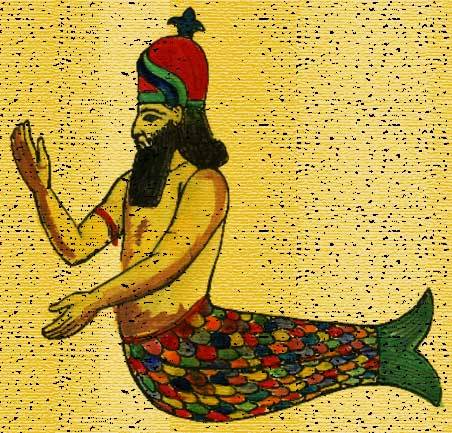

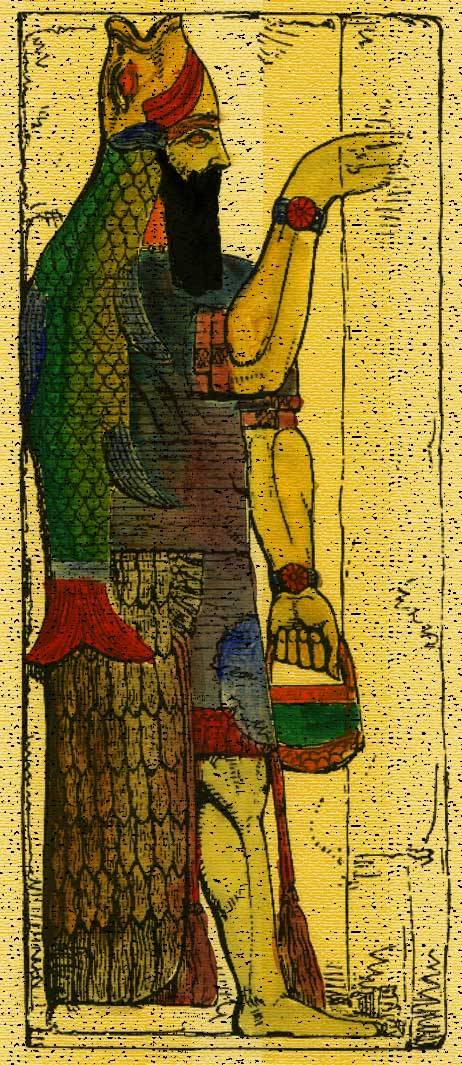

Jonah the Mer-Man?

"And the Lord commanded the fish, and it vomited Jonah onto dry land." -Jonah 2:10

“Dagon figures into the story of Jonah, as well, although the deity is not mentioned by name in Jonah’s book. The Assyrians in Nineveh, to whom Jonah was sent as a missionary, worshiped Dagon and his female counterpart, the fish goddess Nanshe.

Jonah, of course, did not go straight to Nineveh but had to be brought there via miraculous means. The transportation God provided for Jonah—a great fish—would have been full of meaning for the Ninevites. When Jonah arrived in their city, he made quite a splash, so to speak. He was a man who had been inside a fish for three days and directly deposited by a fish on the shores of Assyria.

The Ninevites, who worshiped a fish god, were duly impressed; they gave Jonah their attention and repented of their sin.”

“What better heralding, as a divinely sent messenger to Nineveh, could Jonah have had, than to be thrown up out of the mouth of a great fish, in the presence of witnesses, say on the coast of Phoenicia, where the fish-god was a favorite object of worship? Such an incident would have inevitably aroused the mercurial nature of Oriental observers, so that a multitude would be ready to follow the seemingly new avatar of the fish-god, proclaiming the story of his uprising from the sea, as he went on his mission to the city where the fish-god had its very centre of worship” (H. Clay Trumbull, “Jonah in Nineveh.” Journal of Biblical Literature, Vol. 2, No.1, 1892, p. 56).

"In the 3rd century B.C., a Babylonian priest/historian named Berosus wrote of a mythical creature named Oannes who, according to Berosus, emerged from the sea to give divine wisdom to men. Scholars generally identify this mysterious fish-man as an avatar of the Babylonian water-god Ea (also known as Enki).

The curious thing about Berosus’ account is the name that he used: Oannes (Ωάννη or Οάννες).Berosus wrote in Greek during the Hellenistic Period. Oannes is just a single letter removed from the Greek name Ioannes. Ioannes happens to be one of the two Greek names used interchangeably throughout the Greek New Testament to represent the Hebrew name Yonah (Jonah), which in turn appears to be a moniker for Yohanan (from which we get the English name John). (See John 1:42; 21:15; and Matthew 16:17.)

Conversely, both Ioannes and Ionas (the other Greek word for Jonah used in the New Testament) are used interchangeably to represent the Hebrew name Yohanan in the Greek Septuagint, which is the Greek translation of the Hebrew Old Testament. Compare 2 Kings 25:23 and 1 Chronicles 3:24 in the Septuagint with the same passages from the Hebrew Old Testament.

As for the missing “I” in Ioannes, according to Professor Trumbull who claims to have confirmed his information with renowned Assyriologist Dr. Herman V. Hilprecht before writing his own article on the subject, “In the Assyrian inscriptions the J of foreign words becomes I, or disappears altogether; hence Joannes, as the Greek representative of Jona, would appear in Assyrian either as Ioannes or as Oannes” (Trumbull, ibid., p. 58).

Nineveh was Assyrian. What this essentially means is that Berosus wrote of a fish-man named Jonah who emerged from the sea to give divine wisdom to man – a remarkable corroboration of the Hebrew account. Berosus claimed to have relied upon official Babylonian sources for his information. Nineveh was conquered by the Babylonians under King Nabopolassar in 612 B.C., more than 300 years before Berosus.

It is quite conceivable, though speculative, that record of Jonah’s success in Nineveh was preserved in the writings available to Berosus. If so, it appears that Jonah was deified and mythologized over a period of three centuries, first by the Assyrians, who no doubt associated him with their fish-god Dagon, and then by the Babylonians, who appear to have hybridized him with their own water-god, Ea.

Prior to its rediscovery, skeptics scoffed at the possibility that so large a city could have existed in the ancient world. In fact, skeptics denied the existence of Nineveh altogether. Its rediscovery in the mid-1800s proved to be a remarkable vindication for the Bible, which mentions Nineveh by name 18 times and dedicates two entire books (Jonah and Nahum) to its fate.It is interesting to note where the lost city of Nineveh was rediscovered. It was found buried beneath a pair of tells in the vicinity of Mosul in modern-day Iraq.

These mounds are known by their local names, Kuyunjik and Nabi Yunus. Nabi Yunus happens to be Arabic for “the Prophet Jonah.” The lost city of Nineveh was found buried beneath an ancient tell named after the Prophet Jonah."

[Major props to Lucas Cortes a homeless guest at the UGM chapel service for mentioning the Dagon connection to the Ninevites and the book of Jonah. This blew my mind!]

Scholarly References:

-https://orthochristian.com/86461.html-

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/3259078

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

THE WHITE OBELISK OF ASHURNASIRPAL I:

IN July 1853, Hormuzd Rassam was excavating an area at the ruins of the mound of Kuyunjik (Nineveh, Mesopotamia, modern-day Mosul Governorate, Iraq), one of the most important cities in the heartland of the Assyrian Empire. The area was an open space between the outer court of the palace of the Assyrian King Sennacherib and the Ishtar Temple.

About 200 feet northeast of the palace, Rassam dug a trench that went down about 15 feet from the surface of the mound. At this point, his workmen found a large, 4-sided, monolith pillar; it was an obelisk, somewhat whitish in colour. The obelisk was lying on it sides. An artist, C. D. Hodder, who accompanied Rassam on his expedition, made drawings of the 4 sides of the obelisk in situ. It is now known as the White Obelisk of Ashurnasirpal I and housed in the British Museum.

Read More

Article and photos © by Osama S.M. Amin on AHE

191 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nineveh

Nahum 3.7

And all who look at you will shrink from you and say, 'Wasted is Nineveh; who will grieve for her?'

Recently, I heard a teacher cite a verse from Nahum and mention that most of us probably had never read the book of Nahum and weren't familiar with its contents.

I wasn't sure that I was familiar with it. I'm certain that I'd read it at some point, but it was years ago. Curious, I turned to the book and found its three chapters were a recounting of the vision of Nahum regarding the destruction of Nineveh, the capital of Assyria, which is now part of Mosul in present-day Iraq.

But, wait. . . Didn’t God send Jonah to Nineveh to warn of the pending judgment of God?

'Arise, go to Nineveh, that great city, and call out against it, for their evil has come up before me.' —Jonah 1.2 (ESV)

True, God had to drag Jonah kicking and screaming to warn the people of Nineveh, but eventually he obeyed God.

And didn't the residents of Nineveh repent in sackcloth and ashes, thus averting the wrath of God?

The word reached the king of Nineveh, and he arose from his throne, removed his robe, covered himself with sackcloth, and sat in ashes. And he issued a proclamation…, 'By the decree of the king and his nobles: Let neither man nor beast, herd nor flock, taste anything. Let them not feed or drink water, but let man and beast be covered with sackcloth, and let them call out mightily to God. Let everyone turn from his evil way and from the violence that is in his hands. Who knows? God may turn and relent and turn from His fierce anger, so that we may not perish.' When God saw what they did, how they turned from their evil way, God relented of the disaster that He had said He would do to them, and He did not do it. —Jonah 3.6-10 (ESV)

When God saw that the people of Nineveh had repented and turned from their sin, He did not destroy the city. In fact, He has given us that same promise.

'When I shut up the heavens so that there is no rain, or command the locust to devour the land, or send pestilence among My people, if My people who are called by My name humble themselves, and pray and seek My face and turn from their wicked ways, then I will hear from heaven and forgive their sin and heal their land.' —2 Chronicles 7.13-14 (ESV)

So what happened? Why do we read about the destruction of Nineveh in the book of Nahum? Did God not honor His promise? That's not possible, for God is perfect and righteous.

'God is not a man, that He should lie…' —Numbers 23.19 (ESV)

A little investigation reveals that there was a span of 150 years between the time Jonah warned Nineveh to repented and the destruction of the city in 612 BC. That would indicate that subsequent generations forgot the example of their forefathers and returned to their sinful ways, once again drawing the wrath and judgment of God.

The Bible tells us that all Scripture is useful for teaching (2 Timothy 3.16). Perhaps we can learn a lesson from the example of Nineveh.

We cannot rely on the godliness of our fathers and forefathers to save our nation from the judgment of God. We need to sound the alarm in our cities and let the people know that the corruption of our decadent society will not be tolerated by a holy God but will result in judgment and destruction!

'Yet even now,' declares the LORD, 'return to Me with all your heart, and with fasting, weeping, and mourning; and rend your heart and not your garments.' Now return to the LORD your God, for He is gracious and compassionate, slow to anger, abounding in lovingkindness and relenting of evil. Who knows whether He will not turn and relent and leave a blessing behind Him…. —Joel 2.12-14 (NASB)

Where there is repentance and a return to the Lord, there is hope that judgment might be averted.

2 notes

·

View notes