#Milt Gabler

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Bill Haley and His Comets - Goofin' Around (1956) 'Franny' Beecher/ Johnny Grande from: "Goofin' Around" (UK Promo Single} "Rock n' Roll Stage Show Pt. 3" (US | EP) "Calling All Comets" / "Goofin' Around" (German Single) "Bill Haley: The Decca Years and More" (Bear Family Records 5 CD Box Set)

Instrumental

JukeHostUK (left click = play) (320kbps)

YouTube from: the film "Don't Knock the Rock" (1956)

Personnel: Bill Haley: Rhythm Guitar Francis 'Franny' Beecher: Lead Guitar Rudy Pompilli: Tenor Saxophone Johnny Grande: Accordion / Piano William F. 'Billy' Williamson: Steel Guitar Al Rex: Double Bass Ralph Jones: Drums

Produced by Milt Gabler

Recoded: @ The Pythian Temple in New York Cily, New York USA on March 23, 1956

Released 1956: Brunswick Records UK Decca Records USA

Box Set Released 1991: Bill Haley: The Decca Years and More (Bear Family Records 5 CD Box Set)

#Bill Haley and His Comets#Goofin' Around#Johnny Grande#'Franny' Beecher#Instrumental#Milt Gabler#1950's#Bill Haley

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

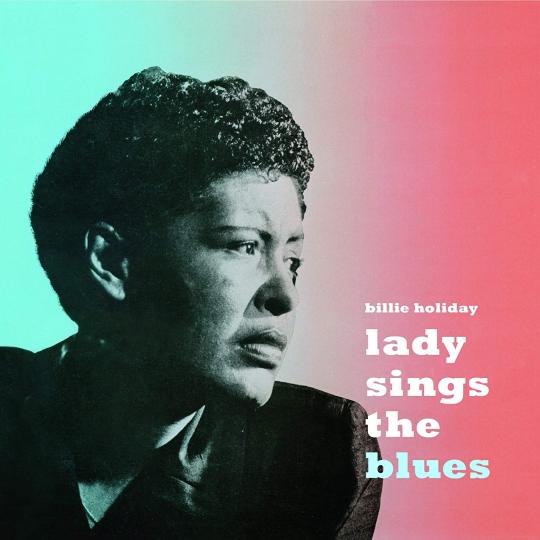

Throwback: Billie Holiday-Strange Fruit

Billie Holiday recorded "Strange Fruit" in 1939 and performed it at New York's first integrated nightclub, Café Society. Abel Meeropol wrote "Strange Fruit" as a poem in 1937 under the name Lewis Allan in response to a photograph taken by Lawrence Beitler of African-American boys J. Thomas Shipp and Abraham S. Smith hanging from trees on August 7, 1930, in Marion, Indiana. Holiday was signed to Columbia Records and they would not let her record "Strange Fruit" for fear of a southern backlash. Holiday's friend, Milt Gabler, the owner of Commodore Records, agreed to release it on his label so Columbia gave Holiday a one-session release. She re-recorded the song in 1944 but the 1939 recording sold one million copies and became her best-selling single. Holiday was initially concerned about retaliation for recording "Strange Fruit" but she did it anyway because it reminded her of the life-saving medical treatment her father was denied because of racism. The poetic description of Black bodies, blood, and trees was haunting and her performance of it made audiences stand still. When she sang it at Café Society the lights were dimmed and you could only see her face. At the end of the performance, the audience looked up and she was gone before the stage lights were restored. Holiday's unique way of phrasing and improvisation is one of the reasons why her version of "Strange Fruit" is still the most popular after decades of new covers.

"Strange Fruit" has been called the "song of the century" and "the beginning of the Civil Rights Movement." Emmett Till's lynching has always been credited as the real start of the movement but "Strange Fruit"'s release two years before his birth was the most egregious artistic statement about Jim Crow America.

Holiday died in 1959 after a tumultuous career as a jazz and pop vocalist innovator. Diana Ross received an Oscar nomination for her portrayal of Holiday in the 1972 film Lady Sings The Blues. Andra Day starred as the singer in Lee Daniels' 2021 film The United States vs. Billie Holiday.

youtube

1 note

·

View note

Text

Bill Haley and His Comets - Goofin' Around (1956) 'Franny' Beecher/ Johnny Grande from: "Goofin' Around" (UK Promo Single} "Rock n' Roll Stage Show Pt. 3" (US | EP) "Calling All Comets" / "Goofin' Around" (German Single) "Bill Haley: The Decca Years and More" (Bear Family Records 5 CD Box Set)

Instrumental

JukeHostUK (left click = play) (320kbps)

Personnel: Bill Haley: Rhythm Guitar Francis 'Franny' Beecher: Lead Guitar Rudy Pompilli: Tenor Saxophone Johnny Grande: Accordion / Piano William F. 'Billy' Williamson: Steel Guitar Al Rex: Double Bass Ralph Jones: Drums

Produced by Milt Gabler

Recoded: @ The Pythian Temple in New York City, New York USA on March 23, 1956

Released 1956: Brunswick Records (UK) Decca Records (US)

Box Set Released 1991: Bill Haley: The Decca Years and More (Bear Family Records 5 CD Box Set)

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Carmen Mercedes McRae (April 8, 1922 – November 10, 1994) was a jazz singer. She is considered one of the most influential jazz vocalists of the 20th century and is remembered for her behind-the-beat phrasing and ironic interpretation of lyrics.

She was born in Harlem. Her father, Osmond, and mother, Evadne (Gayle) McRae, were immigrants from Jamaica. She began studying piano when she was eight, and the music of jazz greats such as Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington filled her home. When she was 17 years old, she met singer Billie Holiday. As a teenager, she came to the attention of Teddy Wilson and his wife, the composer Irene Kitchings. One of her early songs, “Dream of Life”, was, through their influence, recorded in 1939 by Wilson’s long-time collaborator Billie Holiday. She considered Holiday to be her primary influence.

She played piano at an NYC club called Minton’s Playhouse, Harlem’s most famous jazz club, sang as a chorus girl, and worked as a secretary. It was at Minton’s where she met trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie, bassist Oscar Pettiford, and drummer Kenny Clarke, had her first important job as a pianist with Benny Carter’s big band (1944), worked with Count Basie (1944) and under the name “Carmen Clarke” made her first recording as a pianist with the Mercer Ellington Band (1946–47). But it was while working in Brooklyn that she came to the attention of Decca’s Milt Gabler. Her five-year association with Decca yielded 12 LPs.

She sang in jazz clubs across the world—for more than fifty years. She was a popular performer at the Monterey Jazz Festival, performing with Duke Ellington’s orchestra at the North Sea Jazz Festival, singing “Don’t Get Around Much Anymore”, and at the Montreux Jazz Festival. She left New York for Southern California in the late 1960s, but appeared in New York regularly, usually at the Blue Note, where she performed two engagements a year through most of the 1980s. She collaborated with Harry Connick Jr. on the song “Please Don’t Talk About Me When I’m Gone”. #africanhistory365 #africanexcellence

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

LÉGENDES DU JAZZ

CARMEN McRAE, UNE CHANTEUSE SANS COMPROMIS

"It's not easy, traveling to appear in club after club. And jazz musicians apparently do not receive the same respect that other musicians have. I [got] sick of having to get dressed in offices because they [didn't] have proper dressing rooms--or even full-length mirrors--in some of these clubs... All of this really detracts. Club owners don't seem to realize that the conditions in a lot of clubs aren't conducive to getting the best performances out of an artist."

- Carmen McRae

Née le 8 avril 1920 à Harlem, près de New York, Carmen Mercedes McRae était la fille unique d’Osmond ‘’Oscar’’ Llewelyn McRae et d’Evadne Gayle, deux immigrants originaires de la Jamaïque. Né à Santa Cruz, en Jamaïque, Osmond s’était d’abord installé au Costa Rica, puis à Cuba, avant de s’établir à New York où il avait opéré un club de santé au McAlpin Hotel de Harlem.

Très influencée par Louis Armstrong et Duke Ellington, McRae a d’abord commencé à étudier le piano classique à l’âge de huit ans. Un an après avoir obtenu son diplôme du Julia Richman High School en 1938, McRae avait remporté un concours amateur tenu au Théâtre Apollo de Harlem. La même année, McRae avait connu un premier succès lorsqu’elle avait écrit la chanson “Dream of Life” que Billie Holiday avait enregistré pour les disques Vocalion/Okeh.

McRae avait seulement dix-sept ans lorsqu’elle avait rencontré Billie pour la première fois. Elle expliquait: "We became friends the moment that I met her. We used to hang around together.’’ McRae avait aussi été trés influencée par Sarah Vaughan.

DÉBUTS DE CARRIÈRE

Peu après avoir rencontré Billie, McRae avait été remarquée par le pianiste Teddy Wilson et son épouse, la compositrice Irene Kitchings.

À la fin de l’adolescence et au début de la vingtaine, McRae avait joué du piano au Minton's Playhouse, chanté comme choriste et travaillé comme secrétaire. McRae assurait les intermissions comme pianiste au Minton’s Playhouse lorsqu’elle avait rencontré Dizzy Gillespie, Oscar Pettiford et Kenny Clarke. Elle avait aussi fait partie du groupe de Tony Scott. Se rappelant ses débuts au Minton’s, McRae avait précisé:

"I met [saxophonist] Charlie Parker when... I was 18. And I met [trumpeter] Dizzy Gillespie and [bassist] Oscar Pettiford [and drummer Kenny Clarke]. There was a place under Minton's where we used to go. Teddy Hill, who ran Minton's, used to have the guys come in... They would work and after the club closed, which was [at] 4 o'clock, we'd go downstairs and other guys, other musicians, would come and we'd jam awhile."

Au début des années 1940, McRae s’était brièvement installée en Alabama avant de s’établir à Washington, D.C. où elle avait travaillé comme secrétaire pour le gouvernement fédéral avant de retourner à New York en 1943.

Après avoir obtenu le premier contrat majeur de sa carrière avec le big band de Benny Carter en 1944 et collaboré avec Count Basie et Earl Hines de 1944 à 1946, McRae avait réalisé son premier enregistrement comme pianiste avec le groupe de Mercer Ellington sous le nom de Carmen Clarke (elle avait épousé Kenny Clarke en 1944). C’est en travaillant à Brooklyn que McRae avait attiré l’attention du producteur Milt Gabler des disques Decca avec qui elle avait enregistré douze albums en cinq ans et lui avait permis de connaître de grands succès avec des chansons comme “Skyliner”, “By Special Request”, “After Glow”, “Something to Swing About”, “Suppertime”, “Torchy” et “Blue Moon.” Au début des années 1950, McRae avait également travaillé comme pianiste avec le Mat Mathews Quintet. Comme pianiste, McRae avait été très influencée par Thelonious Monk.

En 1948, McRae s’était installée à Chicago avec l’acteur George Kirby, de qui elle était tombée amoureuse. McRae était devenue chanteuse un peu par hasard. Un jour, une des amies de McRae lui avait proposé de chanter lors d’une de ses soirées. Elle expliquait: "I was having all of those problems waiting for George to send me the check to pay the rent, and she said, 'C'mon with me.' She took me someplace to play piano and sing. I said, 'Girl, I know about seven songs,' but she just thought I was great. I thought she was crazy."

Après avoir rompu avec Kirby, McRae avait travaillé comme pianiste et chanteuse à l’Archway Lounge. McRae avait joué du piano pendant environ quatre ans dans des clubs de Chicago jusqu’à ce qu’elle décide de retourner à New York en 1952. C’est cependant à Chicago que McRae avait commencé à créer son propre style. Décrivant cette période de sa vie dans une entrevue qu’elle avait accordée au magazine Jazz Forum, McRae avait déclaré que Chicago "gave me whatever it is that I have now. That's the most prominent schooling I ever had."

À son retour à New York, McRae avait signé le contrat de disques qui avait lancé sa carrière et lui avait permis de remporter le prix de la meilleure chanteuse de la relève (Best New Female Singer) décerné par le magazine Down Beat en 1954. L’année suivante, elle avait terminé à égalité avec nulle autre qu’Ella Fitzgerald dans le cadre d’un sondage organisé par le magazine Metronome.

Parmi les plus importants enregistrements de McRae, on remarquait Here to Stay (1955-1959), Mad About The Man (1957) une collaboration avec le compositeur Noël Coward, Boy Meets Girl (1957) avec Sammy Davis, Jr., Lover Man (1962) et The Great American Songbook (1972). McRae avait enregistré un premier album comme leader en 1953. Après avoir dirigé son propre trio de 1961 à 1969, McRae s’était installée en Californie afin de se rapprocher de sa famille.

McRae avait également collaboré à l’album The Real Ambassadors (1961) de Dave Brubeck aux côtés de Louis Armstrong, et enregistré un album en hommage a Nat King Cole intitulé You're Lookin' at Me (1983). McRae avait aussi enregistré un album en duo avec Betty Carter intitulé The Carmen McRae-Betty Carter Duets (1987) accompagnée au piano par Dave Brubeck et George Shearing.

McRae avait également fait plusieurs apparitions au cinéma dans des films comme The Subterraneans (1960), Hotel (1967) et Jo Jo Dancer, Your Life Is Calling (1986). Elle avait aussi participé à plusieurs séries télévisées, dont Soul (1976), Sammy and Company (1976) et Roots (1977).

DERNIÈRES ANNÉES

À la fin de sa carrière, McRae avait enregistré des albums en hommage à ses idoles Thelonious Monk (Carmen Sings Monk, 1990) et Sarah Vaughan (Sarah: Dedicated to You, 1991). Les paroles des pièces de Monk avaient été écrites par Jon Hendricks, Abbey Lincoln, Mike Ferro, Sally Swisher et Bernie Hanighen. Considéré comme un des meilleurs albums de sa carrière, Carmen Sings Monk avait représenté tout un défi pour McRae qui avait expliqué: "I considered it one of the hardest projects I've ever worked on. His melodies are not easy to remember because they don't go where you think they're going to go."

Amie de longue date de Billie Holiday, McRae n’avait jamais présenté un seul concert sans y inclure au moins une chanson tirée du répertoire de Lady Day. En 1983, McRae avait d’ailleurs rendu hommage à Billie sur un album intitulé For Lady Day, qui comprenait des classiques comme "Good Morning Heartache", "Them There Eyes", "Lover Man", "God Bless the Child" et "Don't Explain.’’ L’album n’avait finalement été publié qu’en 1995. McRae avait aussi collaboré avec les plus grands noms du jazz sur des albums comme Take Five Live (avec Dave Brubeck en 1961), Two For the Road (avec George Shearing en 1980) et Heat Wave (un album de jazz latin enregistré avec Cal Tjader en 1982).

Au cours de sa carrière, McRae avait chanté dans les clubs des États-Unis et d’un peu partout sur la planète durant plus de cinquante ans. Incontournable du Festival de jazz de Monterey, en Californie, où elle s’était produite de 1961 à 1963, en 1966, en 1971, en 1973 et en 1982, McRae avait également chanté avec l’orchestre de Duke Ellington au North Sea Jazz Festival en 1980 et au Festival de jazz de Montreux en 1989 où elle avait partagé la scène avec Dizzy Gillespie et Phil Woods. McRae était aussi très populaire au Japon.

Même si elle avait quitté New York pour le sud de la Californie à la fin des années 1960 afin de se rapprocher de sa famille, McRae avait continué de produire dans le Big Apple sur une base régulière, et plus particulièrement au club Blue Note, où elle s’était produite deux fois l’an pendant la majeure partie des années 1980. De mai à juin 1988, McRae avait également participé au premier album de Harry Connick Jr. dans le cadre de la pièce "Please Don't Talk About Me When I'm Gone". Grande fumeuse, McRae s’est retirée de la scène en mai 1991 après avoir connu des difficultés respiratoires à la suite d’un contrat au club Blue Note de New York.

Reconnue pour son élégance et son habileté à s’investir émotionnellement et intellectuellement dans les chansons qu’elle interprétait, Carmen McRae est morte le 10 novembre 1994 à sa résidence de Beverly Hills, en Californie. Elle était âgée de soixante-quatorze ans. Quatre jours auparavant, McRae était tombée dans un demi-coma, un mois après avoir été hospitalisée à la suite d’une attaque.

McRae s’est mariée à deux reprises. De 1944 à 1956, McRae avait d’abord été mariée au batteur Kenny Clarke, de qui elle s’était séparée en 1948. Après avoir divorcé de Clarke en 1956, McRae s’était remariée au contrebassiste Ike Isaacs de qui elle avait divorcé en 1967. Elle n’avait jamais eu d’enfants.

Mise en nomination à six reprises pour des prix Grammy (notamment pour son hommage à Thelonious Monk en 1990 et pour son duo avec Betty Carter en 1988), McRae a été élue ‘’Jazz Master’’ par la National Endowment for the Arts en 1994. L’année précédente, McRae avait également remporté le Image Award décerné par la National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

Le style de McRae avait été décrit par le critique Ralph Gleason comme un “exercise in dramatic art.” McRae, qui avait grandi dans un environnement très marqué par le blues, ne se considérait cependant pas comme une chanteuse de blues. Comme elle l’avait expliqué dans le cadre d’une entrevue qu’elle avait accordée au magazine Jazz Forum: "The blues is like the national anthem of jazz. I have sung the blues... but more jazzy blues.... I think you have to have a special talent for [singing blues], which I don't have."

McRae avait toujours eu des opinions très arrêtées sur son métier. Considérant le jazz essentiellement comme un art d’improvisation, McRae croyait également qu’il était indispensable de savoir jouer d’un instrument pour devenir chanteuse de jazz. Elle expliquait: "You should know an instrument to be a good jazz singeré Ella [Fitzgerald] plays a little piano. Sarah [Vaughan] played piano; I play piano; Shirley Horn plays. All these ladies can sing Jazz." Selon McRae, une chanteuse de jazz devait également savoir improviser. Elle poursuivait: "You have to improvise, you have to have something of your own that has to do with that song. And you have to know where you're going when you improvise." Mais même si elle adorait la musique, McRae détestait certains aspects de son métier comme les nombreux voyages et le fait de devoir chanter dans les clubs. Comme elle l’avait expliqué au cours d’une entrevue accordée au magazine Coda: "It's not easy, traveling to appear in club after club. And jazz musicians apparently do not receive the same respect that other musicians have. I [got] sick of having to get dressed in offices because they [didn't] have proper dressing rooms--or even full-length mirrors--in some of these clubs... All of this really detracts. Club owners don't seem to realize that the conditions in a lot of clubs aren't conducive to getting the best performances out of an artist."

Même si elle était reconnue pour son sens du rythme, son contrôle vocal impeccable, sa technique irréprochable et sa grande maîtrise du scat et du bebop, McRae n’était jamais devenue aussi populaire que des chanteuses comme Ella Fitzgerald et Sarah Vaughan. McRae étant toujours demeurée fidèle à un jazz plutôt traditionnel, elle avait surtout rejoint une clientèle d’inconditionnels et de puristes. Mais même si elle avait parfois été blessée de ce manque de reconnaissance, McRae avait toujours refusé de faire des compromis et de changer son style. Comme McRae l’avait déclaré au cours d’une entrevue qu’elle avait accordée au magazine Down Beat, le jazz était quelque chose qui faisait partie de votre coeur, et qui faisait partie de vous. Il n’était donc pas possible de le changer.

©-2024, tous droits réservés, Les Productions de l’Imaginaire historique

1 note

·

View note

Text

70 years of Rock Around the Clock

Seventy years ago today (April 12, 1954), the world of music changed forever when a group known as Bill Haley and His Comets walked into the Pythian Temple recording studio in New York City and recorded a song called Thirteen Women And Only One Man in Town.

Never heard of it? That's because no one gave a damn about the song producer Milt Gabler (uncle of Billy Crystal) wanted as the lead side of the single. Instead, people wanted to hear Rock Around the Clock. Well, at least they did a year later when a movie producer raided the record collection of a young boy named Peter Ford (son of Hollywood megastar Glenn Ford) in search of a title song for a movie about rebellious high school juveniles called Blackboard Jungle. Then it went straight to the top, and later hit the Top 40 again in 1974 when it was used as the theme for George Lucas' American Graffiti (the success of which made it possible for him to do a little side project called Star Wars) as well as for a new sitcom called Happy Days.

People will argue till they're blue in the face that their song of choice was the first rock and roll song. My choice was a 1950 recording - by Haley - called Teardrops from My Eyes (call it up on Youtube) but in truth you can find rock and roll-style recording going back almost to the start of the 20th century. Rock Around the Clock wasn't even the first major hit rock and roll song (Haley's own Crazy Man Crazy did that back in 1953, a year and a half before Elvis professionally recorded his first song). But RATC opened the floodgates and even though today's "rock" is nothing like the mashup of country music and rhythm and blues that was the original rock and roll formula, the fact is "rock and roll" will never burn out, and this song lit the fuse.

As it might be a no-no for me to post a Youtube "record video" of the original song, here is Haley and the Comets playing the song on the Ed Sullivan Show in the fall of 1955. I am honoured to have known and met three of the musicians on the original recording: Marshall Lytle (bass), Johnny Grande (piano, though he plays accordion here as the stage didn't have room for a piano) and Joey D'Ambrosio (sax). Also on this clip are two other people I knew - Dick Richards (who acted in movies like My Blue Heaven with SteveMartin and HBO series Oz under the name Richard Boccelli) on drums and Franny Beecher on lead guitar. (Rounding out the group is Billy Williamson on steel). Dick and Joey continued to tour as the Comets until COVID forced them to retire and they both passed away soon after. Immense respect to all these gentlemen - as well as to a 60-something postal carrier named Max Freedman who on the side did some songwriting and wrote Rock Around the Clock, and to James Myers, the song's publisher, who got his pseudonym Jimmy De Knight put on the songwriting credits, but was still an endless promoter of the song and of Bill Haley in those early days.

youtube

1 note

·

View note

Link

1 note

·

View note

Video

youtube

Bert Kaempfert And His Orchestra A Song For Lovers (1974)

Composer: Herbert Rehbein, Bert Kaempfert Producer: Milt Gabler Album: Portrait In Music ℗ 1974 Doris Kaempfert, under exclusive license to Polydor/Island, a division of Universal Music GmbH

#bert kaempfert and his orchestra#a song for lovers#bert kaempfert#herbert rehbein#milt gabler#portrait in music#album cover#jazz#easy listening#orchestra#1970s#good god#perfection#bursted into tears during the first 20 seconds#when the music touches the very soul#the atmosphere is somehow similar as in#mistral's daughter#:')#own post

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

August 1947. New York. "Lou Blum, Jack Crystal [reaching] and Herbie Hill [rear] at Milt Gabler's Commodore Record Shop on 42nd Street." Medium format negative by William Gottlieb for Down Beat magazine. View full size.

#Lou Blum#Jack Crystal#Herbie Hill#Milt Gabler's Commodore Record Shop#42nd Street#vintage#shorpy#1947#New York City#William Gottlieb#Down Beat#magazine

213 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

This is singer-songwriter Yokez 叶玉棂 (Yap Yoke Ling) from Singapore.

She’s doing a crowdfunding for her debut ep over at Kickstarter. Lots of pledge levels and perks available, and $1,610 pledged so far of a modest $4,904 goal. 38 days left in the campaign.

Lots of covers and live stuff on her YT channel, let’s check out her rendition of a classic:

youtube

Watch to the end for some amusing outtakes. =D

#Yokez 叶玉棂#Yap Yoke Ling#singapore#cover#nat king cole#music video#Bert Kaempfert & Milt Gabler#wikipedia

1 note

·

View note

Text

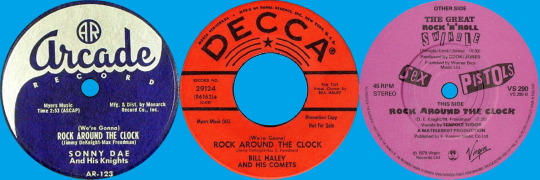

Rock Around the Clock Three Versions

1) Sonny Dae and His Knights - (We’re Gonna) Rock Around the Clock (1954) Jimmy DeKnight (James E. Myers) / Max Freedman from: “Rock Around the Clock” / “Moving Guitar” (Single)

R&B | Rock and Roll

JukeHostUK (left click = play) (320kbps)

Personnel: Sonny Dae: Vocals Hal Hogan: Piano Art Buono: Guitar Mark Bennett: Bass / Drums

Recorded: on March 20, 1954 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania USA

Arcade Records

♫♫♫ ♫♫♫ ♫♫♫

2) Bill Haley and His Comets - (We're Gonna) Rock Around the Clock (1954) Jimmy DeKnight (James E. Myers) / Max Freedman from: "(We're Gonna) Rock Around the Clock" / "Thirteen Women" (Single) "From the Original Master Tapes: Bill Haley and His Comets" (1985 Compilation)

Rock and Roll | 1st Wave Rock and Roll

JukeHostUK (left click = play) (320kbps)

Originally issued in 1954 with "Thirteen Women" as the A-side.

Recorded: @ The Pythian Temple in New York City, New York USA on April 12, 1954

Personnel: Bill Haley: Lead Vocals / Guitar Danny Cedrone: Lead Guitar Billy Williamson: Steel Guitar Joey D'Ambrosia: Tenor Saxophone Johnny Grande: Piano Marshall Lytle: Bass Billy Guesak: Drums

Produced by Milt Gabler

Released: on May 10, 1954

Decca Records

MCA Records (1985 Compilation)

♫♫♫ ♫♫♫ ♫♫♫

3) Sex Pistols – Rock Around the Clock (1979) Jimmy DeKnight (James E. Myers) / Max Freedman from: "The Great Rock 'n' Roll Swindle" / "Rock Around the Clock" (Single)

Punk | UK Punk

Tumblr (left click = play) (320kbps)

Personnel: Tenpole Tudor: Vocals Steve Jones: Guitar Dave Goodman: Bass Paul Cook: Drums

Produced by Paul Cook / Steve Jones

Recorded: @ Ramport Studios in London, England UK June, 1978

Released: September 12, 1979

Virgin Records

Sonny Dae and His Knights | Bill Haley | Sex Pistols

#(We’re Gonna) Rock Around the Clock#Rock Around the Clock#Rock and Roll#Jimmy DeKnight#Max Freedman#1950's#1970's#Punk#UK Punk#Tenpole Tudor#Sonny Dae and His Knights#Sonny Dae#Bill Haley#Sex Pistols#Bill Haley and His Comets

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Bill Haley and Decca Records executive Milt Gabler in New York, 1955

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝐁𝐢𝐥𝐥 𝐇𝐚𝐥𝐞𝐲 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐇𝐢𝐬 𝐂𝐨𝐦𝐞𝐭𝐬 - (𝐖𝐞'𝐫𝐞 𝐆𝐨𝐧𝐧𝐚) 𝐑𝐨𝐜𝐤 𝐀𝐫𝐨𝐮𝐧𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐂𝐥𝐨𝐜𝐤 (𝟏𝟗𝟓𝟒) Jimmy DeKnight / Max Freedman from: "(We're Gonna) Rock Around the Clock" / "Thirteen Women" (Single) "From the Original Master Tapes: Bill Haley and His Comets" (1985 Compilation)

Rock and Roll | 1st Wave Rock and Roll Originally issued in 1954 with "Thirteen Women" as the A-side

𝐅𝐋𝐀𝐂 𝐅𝐢𝐥𝐞 @𝐀𝐫𝐜𝐡𝐢𝐯𝐞 (left click = play) (793kbps) (Size: 12.8MB)

Personnel: Bill Haley: Lead Vocals / Guitar Danny Cedrone: Lead Guitar Billy Williamson: Steel Guitar Joey D'Ambrosia: Tenor Saxophone Johnny Grande: Piano Marshall Lytle: Bass Billy Guesak: Drums

Produced by Milt Gabler

Recorded: @ The Pythian Temple in New York City, New York USA on April 12, 1954

Single Released: on May 10, 1954 Decca Records

MCA Records Compilation Released: 1985

#(We're Gonna) Rock Around the Clock#1950's#Rock Around the Clock#1950s#Rock and Roll#decca records#Bill Haley#Bill Haley and His Comets

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I might like this show a little too much.

Ever wonder if you're too big a fan of your favorite piece of entertainment?

I began to ponder the possibility when I realized I had 104 recordings of Jesus Christ Superstar, studio and live, in whole or in part, stored on my mobile device.

My pondering only grew as I glanced at memorabilia I'd amassed over the years:

A photocopied early draft of the screenplay for the 1973 film (obtained on eBay and since signed by leading cast members Ted Neeley, Barry Dennen, Bob Bingham, Kurt Yaghjian, and -- most recently -- Yvonne Elliman).

A copy of the Ellis Nassour/Richard Broderick tome Rock Opera, which detailed the show's history from inception through the 1973 film, signed by its authors, (possibly) personalized to someone described in the book who'd been involved from the ground up.

Tim Rice's memoir, in paperback, autographed and inscribed to a woman with the same last name (no relation), a piece of his stationery with a further note to her pressed within its pages.

An assortment of CDs and home video releases (of particular note: the recent 50th-anniversary rereleases of the concept album, in "deluxe edition" 3-CD box set and "new half-speed master 180-gm" vinyl form; a DVD of the 1973 film whose sleeve has been signed by Carl Anderson, Dennen, Neeley, Elliman, Yaghjian, Bingham, and Larry Marshall; a VHS tape of the Indigo Girls and friends' SXSW performance of JCS: A Resurrection dating from when they sold it through their site; countless bootlegs in varying states of generational loss as well as tacky remakes that one hopes will be lost to future generations).

Ticket stubs, playbills, and programs alike -- to say nothing of tie-in clothing, accessories, etc. -- from nineteen live performances of thirteen different productions, not all of which occurred when I was born or had me in attendance, six of those which did featuring original cast members from the album and/or film. (I'm also staring at a VIP pass from a recent concert co-headlined by Neeley and Elliman still sitting on my desk.)

Countless digital copies of musical scores, band parts, scripts, and even ephemera -- the complete production file for the 1973 film (courtesy of the Wisconsin Historical Society Archives) and a collection of JCS-related items from the papers of Decca Records executive Milt Gabler fall into that category -- obtained in the murky musical theater trading world over the years. (One especially rare score cost me $75 to obtain from a noteworthy private collector!)

And that's saying nothing of the friendships made and connections forged helping to administrate the number one Internet fan community for JCS.

As well as having had the unparalleled fortune of experiencing the show from multiple viewpoints, which has given me a unique insight into its inner workings, my love of JCS -- and the love of show biz in general that sprang from it -- caused me to collaborate in my adult life with a New York City producer/auteur on a variety of major media projects for both stage and screen. So, without JCS, it's safe to say I might not have had the career I have (and enjoy) now.

Hi. I'm Gibson, and I'm a Jesus Christ Superstar addict connoisseur. I discovered this piece at the age of four, and I've been enamored ever since. I grew up trying to imitate Ted and Carl, and over time I've progressed from a preadolescent unusually obsessed (thank you, autism spectrum disorder) with religious fiction and nonfictional religious studies, the shelves of his film collection littered with biblical epics based on both testaments, to a savvy entertainment professional that just can't let go of his first love.

This is my second attempt to use this blog for JCS musings. Time will tell if I get more out of it than I did before. But this time, I think I have a pretty clear idea of what I want to do with it, so I deleted one superfluous post, privated a bunch of the rest, left public some of the stuff I eventually want to return to -- or discuss more maturely -- as an example of what will go here, and wrote this post.

"What's the Buzz?" is the ask box, and I encourage you to use it. "Disclaimer and Credits" is what will hopefully prevent me from getting sued and acknowledges all the wonderful people I've met along the way as a JCS fan.

So, now that we've dispensed with the niceties, let's proceed to the matter at hand... could we start again, please?

#jesus christ super star#jesus christ superstar#tim rice#andrew lloyd webber#ted neeley#carl anderson#yvonne elliman#barry dennen#bob bingham#kurt yaghjian#larry marshall#ellis nassour#richard broderick#indigo girls#musical#musicals#broadway#musical theatre#musical theater#west end#rock opera#jcs#study#in depth#jcs study#jcss

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Count Basie and His Orchestra – In a Mellow Tone

“In a Mellow Tone“, also known as “In a Mellotone”, is a 1939 jazz standard composed by Duke Ellington, with lyrics written by Milt Gabler. The song was based on the 1917 standard “Rose Room” by Art Hickman and Harry Williams, which Ellington himself had recorded in 1932.

8 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Billie Holiday-Strange Fruit

“Bitter Fruit” was a poem written by Jewish-American writer, teacher and songwriter Abel Meeropol, under his pseudonym Lewis Allan in 1937. Meeropol came across a 1930 photo that captured the lynching of two Black men Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith in Marion, Indiana. The visceral image haunted him for days and prompted him to put pen to paper.

Meeropol put the words to music, the song made its way around New York City. When blues singer Billie Holiday heard the lyrics, the vivid depiction of death reminded her of her father, who died from a lung disorder after being denied treatment at a hospital because of his race.

Holiday said in her autobiography, “It reminds me of how Pop died. But I have to keep singing it, not only because people ask for it, but because 20 years after Pop died, the things that killed him are still happening in the South.”

She first performed the song at Café Society in 1939. She said that singing it made her fearful of retaliation but, because its imagery reminded her of her father, she continued to sing the piece, making it a regular part of her live performances. The club owner Barney Josephson drew up some rules: Holiday would close with it; the waiters would stop all service in advance; the room would be in darkness except for a spotlight on Holiday’s face; and there would be no encore.

Holiday went to her record label, Columbia to record the song, they and her producer John Hammond feared negative reaction by southern record retailers and from affiliates of its co-owned radio network, CBS and refused to allow her recording. But gave her a one-session release from her contract to record it elsewhere. Holiday sang it for her friend Milt Gabler, producer & owner of the Commodore label, he was bought to tears & it was recorded on April 20, 1939.

Harry Anslinger, a known racist & Federal Bureau of Narcotics commissioner was not happy about the song and much less it’s singer. He believed that drugs caused Black people to “overstep their boundaries” in society and that Black jazz singers, who smoked marijuana, created the devil’s music. Journalist Larry Sloman recorded, Charlie Parker, Louis Armstrong and Thelonious Monk, he longed to see them all behind bars. He wrote to all the agents he had sent to follow them and instructed: “Please prepare all cases in your jurisdiction involving musicians in violation of the marijuana laws. We will have a great national round-up arrest of all such persons on a single day. I will let you know what day.” His advice on drug raids to his men was always simple: “Shoot first.”

The Treasury Department told Anslinger he was wasting his time taking on a community that couldn’t be fractured, so he settled on a single target. His Public Enemy #1: Billie Holiday. Anslinger forbid Holiday to perform “Strange Fruit,” she refused. Knowing that Holiday was a drug user, he had some of his men frame her by selling her heroin. When she was caught using the drug, she was thrown into prison for the next year and a half.

“It was called ‘The United States of America versus Billie Holiday,’” she wrote in her memoir, “and that’s just the way it felt.”

She refused to weep on the stand, she didn’t want any sympathy. She just wanted to be sent to a hospital so she could kick the drugs and get well. Please, she said to the judge, “I want the cure.” Instead she was sentenced to a West Virginia prison, forced to go cold turkey and work during the days in a pigsty, among other places. She never sang while imprisoned. Upon her release in 1948 as a former convict, she was stripped of her cabaret performer’s license. Carrying on she went to bigger venues including sold out performances at Carnegie Hall. Holiday’s demons followed her and she eventually went back to using heroin.

At the age of 44 she collapsed and was taken to Knickerbocker Hospital in Manhattan waited for an hour & a half, then turned away because of her addiction. An ambulance driver recognized her, so she ended up in a public ward of New York City’s Metropolitan Hospital. Emaciated because she had not been eating; cirrhosis of the liver because of chronic drinking; cardiac and respiratory problems due to chronic smoking; and several leg ulcers caused by starting to inject street heroin once again. “They are going to arrest me in this damn bed.”

Her other demon was still after her. Anslinger had narcotics agents sent to her hospital bed and said they had found less than one-eighth of an ounce of heroin in a tinfoil envelope. They claimed it was hanging on a nail on the wall, six feet from the bottom of her bed—a spot Billie was incapable of reaching. They confiscated everything in her room, handcuffed her to her bed and posted two police officers at her door, orders to forbid any visitors from coming in without a written permit, and her friends were told there was no way to see her. A friend protested that it was against the law to arrest somebody who was on the critical list. They solved that problem: they had taken her off the critical list. A new doctor had been allowed to prescribe her methadone to treat her withdrawal symptoms, after days of treatment it was abruptly stopped.

Anslinger’s agents, took her fingerprints & mugshots in her hospital bed, they questioned here there without allowing her to talk to a lawyer. She died in that bed with police officers at the door to protect the public from her. Anslinger wrote with a racist satisfaction- “For her, there would be no more ‘Good Morning Heartache.’” Holiday’s legacy has grown in spite of her tragic demise. She has been inducted into the National Rhythm & Blues Hall of Fame, posthumously granted 23 Grammys and in 1999 Time designated “Strange Fruit” the “song of the century.”

30 notes

·

View notes