#Maripasoula

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

French Guiana is an overseas department of France located on the northern coast of South America in the Guianas. Bordered by Suriname to the west and Brazil to the east and south. French Guiana is divided into 3 arrondissements( Saint-Lauren-du-Maroni, Saint Georges and Cayenne) and 22 communes. Maps of French Guiana showing the Arrondissement, and the 22 different Communes. they are each Highlighted in locator maps.

#french guiana#Guyane#South America#France#French#Suriname#Brazil#Atlantic Ocean#Saint Laurent Du Maroni#Maripasoula#Kourou#Saint Georges

1 note

·

View note

Photo

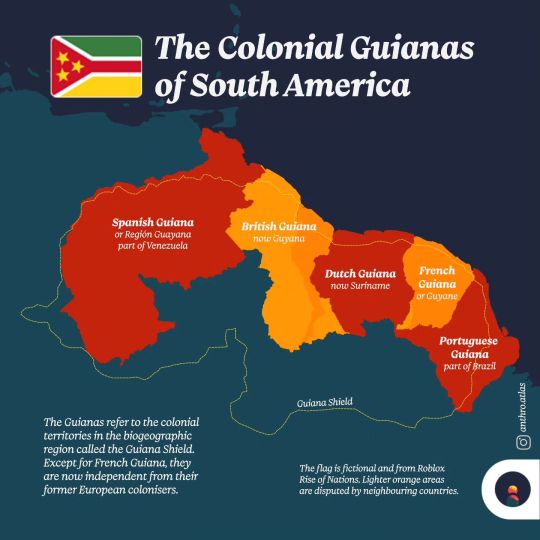

The Five Guianas

by anthro.atlas

The colonial territories in the biogeographic area known as the Guiana Shield are referred to as the Guianas. In an indigenous South American language, the name Guyana or Guayana means “land of many waters.” In the fifteenth century, Europeans began to explore and eventually colonise the Guianas. With the exception of French Guiana, these territories are now sovereign. It should be noted that some sections in this region are disputed: part of Maripasoula between Guyana and French Guiana, lower East Berbice-Corentyne between Suriname and Guyana, and Guayana Esequiba between Venezuela and Guyana.

119 notes

·

View notes

Text

How Indigenous Groups Are Leading the Way on Data Privacy

Indigenous groups are developing data storage technology that gives users privacy and control. Could their work influence those fighting back against invasive apps?

Rina Diane Caballar

A person in a purple tshirt wallking in a forest

A member of the Wayana people in the Amazon rain forest in Maripasoula, French Guiana. Some in the Wayana community use the app Terrastories as part of their mapping project.

Emeric Fohlen/NurPhoto via Getty Images

Indigenous groups are developing data storage technology that gives users privacy and control. Could their work influence those fighting back against invasive apps?

Even as Indigenous communities find increasingly helpful uses for digital technology, many worry that outside interests could take over their data and profit from it, much like colonial powers plundered their physical homelands. But now some Indigenous groups are reclaiming control by developing their own data protection technologies—work that demonstrates how ordinary people have the power to sidestep the tech companies and data brokers who hold and sell the most intimate details of their identities, lives and cultures.

When governments, academic institutions or other external organizations gather information from Indigenous communities, they can withhold access to it or use it for other purposes without the consent of these communities.

“The threats of data colonialism are real,” says Tahu Kukutai, a professor at New Zealand’s University of Waikato and a founding member of Te Mana Raraunga, the Māori Data Sovereignty Network. “They’re a continuation of old processes of extraction and exploitation of our land—the same is being done to our information.”

To shore up their defenses, some Indigenous groups are developing new privacy-first storage systems that give users control and agency over all aspects of this information: what is collected and by whom, where it’s stored, how it’s used and, crucially, who has access to it.

Storing data in a user’s device—rather than in the cloud or in centralized servers controlled by a tech company—is an essential privacy feature of these technologies. Rudo Kemper is founder of Terrastories, a free and open-source app co-created with Indigenous communities to map their land and share stories about it. He recalls a community in Guyana that was emphatic about having an offline, on-premise installation of the Terrastories app. To members of this group, the issue was more than just the lack of Internet access in the remote region where they live. “To them, the idea of data existing in the cloud is almost like the knowledge is leaving the territory because it’s not physically present,” Kemper says.

Likewise, creators of Our Data Indigenous, a digital survey app designed by academic researchers in collaboration with First Nations communities across Canada, chose to store their database in local servers in the country rather than in the cloud. (Canada has strict regulations on disclosing personal information without prior consent.) In order to access this information on the go, the app’s developers also created a portable backpack kit that acts as a local area network without connections to the broader Internet. The kit includes a laptop, battery pack and router, with data stored on the laptop. This allows users to fill out surveys in remote locations and back up the data immediately without relying on cloud storage.

Āhau, a free and open-source app developed by and for Māori to record ancestry data, maintain tribal registries and share cultural narratives, takes a similar approach. A tribe can create its own Pātaka (the Māori word for storehouse), or community server, which is simply a computer running a database connected to the Internet. From the Āhau app, tribal members can then connect to this Pātaka via an invite code, or they can set up their database and send invite codes to specific tribal or family members. Once connected, they can share ancestry data and records with one another. All of the data are encrypted and stored directly on the Pātaka.

Another privacy feature of Indigenous-led apps is a more customized and granular level of access and permissions. With Terrastories, for instance, most maps and stories are only viewable by members who have logged in to the app using their community’s credentials—but certain maps and stories can also be made publicly viewable to those who do not have a login. Adding or editing stories requires editor access, while creating new users and modifying map settings requires administrative access.

For Our Data Indigenous, access levels correspond to the ways communities can use the app. They can conduct surveys using an offline backpack kit or generate a unique link to the survey that invites community members to complete it online. For mobile use, they can download the app from Google Play or Apple’s App Store to fill out surveys. The last two methods do require an Internet connection and the use of app marketplaces. But no information about the surveys is collected, and no identifying information about individual survey participants is stored, according to Shanna Lorenz, an associate professor at Occidental College in Los Angeles and a product manager and education facilitator at Our Data Indigenous.

Such efforts to protect data privacy go beyond the abilities of the technology involved to also encompass the design process. Some Indigenous communities have created codes of use that people must follow to get access to community data. And most tech platforms created by or with an Indigenous community follow that group’s specific data principles. Āhau, for example, adheres to the Te Mana Raraunga principles of Māori data sovereignty. These include giving Māori communities authority over their information and acknowledging the relationships they have with it; recognizing the obligations that come with managing data; ensuring information is used for the collective benefit of communities; practicing reciprocity in terms of respect and consent; and exercising guardianship when accessing and using data. Meanwhile Our Data Indigenous is committed to the First Nations principles of ownership, control, access and possession (OCAP). “First Nations communities are setting their own agenda in terms of what kinds of information they want to collect,” especially around health and well-being, economic development, and cultural and language revitalization, among others, Lorenz says. “Even when giving surveys, they’re practicing and honoring local protocols of community interaction.”

Crucially, Indigenous communities are involved in designing these data management systems themselves, Āhau co-founder Kaye-Maree Dunn notes, acknowledging the tribal and community early adopters who helped shape the Āhau app’s prototype. “We’re taking the technology into the community so that they can see themselves reflected back in it,” she says.

For the past two years, Errol Kayseas has been working with Our Data Indigenous as a community outreach coordinator and app specialist. He attributes the app’s success largely to involving trusted members of the community. “We have our own people who know our people,” says Kayseas, who is from the Fishing Lake First Nation in Saskatchewan. “Having somebody like myself, who understands the people, is only the most positive thing in reconciliation and healing for the academic world, the government and Indigenous people together.”

This community engagement and involvement helps ensure that Indigenous-led apps are built to meet community needs in meaningful ways. Kayseas points out, for instance, that survey data collected with the Our Data Indigenous app will be used to back up proposals for government grants geared toward reparations. “It’s a powerful combination of being rooted in community and serving,” Kukutai says. “They’re not operating as individuals; everything is a collective approach, and there are clear accountabilities and responsibilities to the community.”

Even though these data privacy techniques are specific to Indigenous-led apps, they could still be applied to any other app or tech solution. Storage apps that keep data on devices rather than in the cloud could find adopters outside Indigenous communities, and a set of principles to govern data use is an idea that many tech users might support. “Technology obviously can’t solve all the problems,” Kemper says. “But it can—at least when done in a responsible way and when cocreated with communities—lead to greater control of data.”

1 note

·

View note

Text

In the shadows of the dense and untamed Amazon rainforest of French Guiana, an ancient secret lay buried beneath layers of earth and time. Villagers from nearby Maripasoula whispered of a chilling legend, the tale of a being not of flesh but of metal and bone, a sentinel left by a civilization lost to history.

They called it the 'Skeletal Guardian of the Emerald Canopy'. It was said that deep within the jungle, there was a place where the trees grew thick and formed a dark, almost sacred grove. The legend spoke of a cryptic temple hidden by the emerald embrace of the forest, and within it, the Guardian stood vigil.

Explorers and treasure hunters scoffed at such superstitious tales, but one, a man of science and arrogance, Dr. Henri Blanchard, dared to unveil the truth. With a team of the most skilled navigators and engineers, he embarked on an expedition to the heart of French Guiana’s mysterious interior.

Weeks turned to months, and the dense jungle tested their mettle. Then, amidst the eternal green, they found it – an edifice of stone, overgrown and forgotten. As they breached the temple, the air grew cold, and a metallic scent filled their lungs.

It was there, standing as if it had been awaiting them for millennia, the Skeletal Guardian. A marvel of biomechanics, it had a human skull with eyes glowing a sinister purple, its body a fusion of polished white bone and intricate purple mechanisms that whispered of a technology beyond comprehension.

Dr. Blanchard, driven by obsession, approached the Guardian, reaching for the crystal lodged in its cranial cavity. The moment his fingers brushed the gem, the temple shuddered, and the Guardian stirred to life.

The team fled in terror as the creature pursued with silent grace, its skull aglow with a menacing light. They were never seen again. Now, they say the forest is alive with a new whisper, a warning: the Guardian stirs, and with it, the jungle breathes and watches.

So, travelers beware. For in the depths of French Guiana's verdant labyrinth lies a horror not just of bone and metal, but of greed and the eternal guardianship of the forgotten dead.

0 notes

Text

Fransen dit jaar harder tegen illegale goudzoekers uit Suriname en Brazilië

Fransen treden dit jaar hard op tegen illegale goudzoekers uit Suriname en Brazilië. Porknokkers uit Suriname en Brazilië, die illegaal in Frans-Guyana naar goud zoeken, mogen hun borst nat maken. Elisabeth Borne, de premier van Frankrijk, heeft aangekondigd dat de strijd tegen de illegale goudwinning in 2024 zal worden verhevigd. Brazilië is hofleverancier van de illegalen. Suriname daarentegen is een belangrijke leverancier van logistiek, veelal gesmokkeld over de honderden kilometers lange grensrivier. Borne deed de aankondiging op oudjaarsdag bij een eendaags bezoek aan Maripasoula, dicht bij de grens met Suriname. Dit was ter gelegenheid van de viering van de jaarwisseling met de lokale strijdkrachten. Ze heeft de verheviging van de aanpak niet voor niets daar gelanceerd. De regio staat te boek als een haard van illegale praktijken, die direct en indirect verweven zijn met de goudkoorts aan weerszijden van de grens. Deze illegale praktijken variëren van de smokkel van levensmiddelen en brandstof tot prostitutie en witwassen en van mensenhandel en -smokkel tot gewapende berovingen en handel in illegale wapens. De strijd tegen de illegale goudzoekers in dat gebied kostte begin 2023 een lid van de Nationale Gendarmerie Interventie Eenheid (GIGN) het leven. Arnaud Blanc sneuvelde nadat zwaar gewapende garimpeiro's een patrouille onder vuur hadden genomen te Dorlin, waar zich veel Braziliaanse en Surinaamse goudzoekers ophouden. Het was niet de eerste keer dat er dodelijke slachtoffers zijn gevallen aan de kant van de Franse strijdkrachten. Een van de grote uitdagingen voor de Fransen om deze vorm van stroperij te bestrijden, zijn de open grenzen met Brazilië in het zuiden en Suriname in het westen. De grens met Suriname strekt zich over meer dan 500 kilometer vanaf de Lawarivier in het zuiden tot de monding van de Marowijnerivier in het noorden. Borne sprak na aankomst met de plaatselijke burgemeester, Serge Anelli, en ging vervolgens naar de Forward Operating Base van het 9de Regiment d'Infanterie de Marine (9e RIMA) oftewel de Franse mariniers in Frans-Guyana, voor een presentatie over de strijd tegen de illegale goudwinning. Het bezoek van de premier is breed uitgemeten in de Franse media. Bijna 7500 illegale garimpeiro's De commandant van de Frans-Guyanese gendarmerie, Jean-Christophe Sintive, schatte in een recent interview met het Franse medium‘Guyane la 1 ère’ (Guyane la première), dat er zich tussen de 6500 en 7500 illegale goudzoekers bevinden op het grondgebied. Bijna 95% daarvan komt uit Brazilië. Naar schatting komt 5% uit andere Zuid-Amerikaanse, landen zoals Suriname en Guyana. Daarbij is kennelijk geen rekening gehouden met de honderden en misschien ook duizenden Surinamers die dagelijks de grens oversteken om hun geluk te beproeven en bij zonsondergang terugkeren naar hun dorpen aan de Surinaamse oever. Een andere groep blijft steeds ongeveer twee weken, de gemiddelde cyclus voor elke ‘goudoogst’ om terug te keren naar huis. Zero tolerance De Fransen hanteren in tegenstelling tot Suriname een zero tolerance beleid. Dagelijks worden gemiddeld 250 gendarmes en 500 soldaten ingezet om illegale goudzoekers op te jagen. Goudzoekerskampen worden regelmatig platgebrand. Machines worden daarbij niet ontzien. Illegalen worden opgepakt. Er is sprake van een ontmoedigingsbeleid waarbij niet alleen kampen worden aangevallen. De missie richt zich ook veel op het onderscheppen van smokkelwaar bestemd voor de goudvelden. De Fransen hopen daarmee genoeg schade toe te brengen aan de investeerders zodat ze ontmoedigd raken om door te gaan. De bazen, veelal de eigenaren van de dieselmachines, worden ingezet. Ze hebben daarnaast genoeg geld om te zorgen voor de volledige uitrusting van een kamp voor ongeveer 5 tot 7 mannen. Indien ze niet de financiële veerkracht hebben om enkele mislukte oogsten te boven te komen, kunnen ze failliet raken. Wie ook nog geraakt wordt door de klappen van de gendarmerie kan al gauw ontmoedigd raken. In 2022 werd volgens de gendarmerie ongeveer 7 ton goud uit de grond geplunderd. In 2021 was dat 10 ton. De schade in 2023 moet nog worden uitgerekend. Deze offensieven hebben vaak ook Surinaamse goudzoekers getroffen die dachten dat ze op Surinaams territoir bezig waren. Het laatste geval was in december 2023. Bij deze actie, minder dan een maand geleden, werden op een eiland dicht bij de Singatitey stroomverstelling onder meer een machine in brand gestoken, waterslangen doorgesneden, een sluice box kapotgeslagen en een vat diesel gedumpt. In eerdere gevallen was de schade soms groter. Meerdere keren zijn ook scalians in beslag genomen door de Fransen, terwijl de ondernemers zo zeker waren dat ze aan de Surinaamse zijde van de grens opereerden. Deze incidenten zijn (haast) nooit reden voor de Surinaamse autoriteiten om zich er mee in te laten. Goudzoekers blijven arm Veel van de goudzoekers zijn heel arm, hoewel ze in de beste maanden ongeveer 50 tot 60 gram goud per maand. Maar het komt ook voor dat ze maanden niets verdienen. Uitgezet tegen de lange termijnen die veel van hen in het bos moeten doorbrengen, en de ontberingen die ze moeten doorstaan, verdienen ze eigenlijk een karig loon. Veel van hen maken voorafgaand aan hun vertrek naar de goudvelden schulden om hun gezin niet met lege handen achter te laten. Het komt voor dat sommigen de schulden naderhand niet kunnen terugbetalen. Anderen sturen het goud dat ze verdienen naar hun gezin, zodat het gezin zich in stand kan houden. Wanneer het tijd is om naar huis terug te keren, hebben veel van gen dan bijna niets meer over. Het grootste deel van het goud blijft bij de baas. Meer illegaliteit Voor de Franse autoriteiten is de goudkoorts niet alleen een kwestie van illegaliteit. De werkmethoden leiden ook tot grote blijvende schade aan het milieu, mede door de toepassing van ongecontroleerde ontbossing en de grote hoeveelheden kwik die terechtkomen in het water, de grond en de lucht. Hoewel de Surinaamse autoriteiten dezelfde zorg hebben, is er nog geen landelijk beleid voor de illegale goudsector ontwikkeld. Read the full article

0 notes

Photo

Bienvenue a Maripasoula, plus grande ville de France et la moins densément peuplée 📸 @ptitlitchy --- #lagwiyann #Lagwiyannenvrai👈🏼📸 #WildWideWest #frenchsouthamerica #etrelabasvivrelabasjustelabas #mobelcommune973 #maripasoula https://www.instagram.com/p/CJZ_Wp0niza/?igshid=rojcwt5zcbws

#lagwiyann#lagwiyannenvrai👈🏼📸#wildwidewest#frenchsouthamerica#etrelabasvivrelabasjustelabas#mobelcommune973#maripasoula

0 notes

Photo

Maroni River

River in South America

The Maroni or Marowijne is a river in South America that forms the border between French Guiana and Suriname.

Length: 612 km

Source: Tumuc-Humac Mountains

Mouth: Atlantic Ocean

Basin size: 65,830 km2 (25,420 sq mi)

Maroni (river) - Wikipedia

Maripasoula

Commune in French Guiana

Maripasoula, previously named Upper Maroni, is a commune of French Guiana, an overseas region and department of France located in South America. With a land area of 18,360 km², Maripasoula is the largest commune of France. The commune is slightly larger than the country of Kuwait or the U.S. state of New Jersey.

Population: 11,856 (2015) INSEE

Area: 18,360 km²

Weather: 25°C, Wind E at 8 km/h, 95% Humidity Weather data

Mayor: Serge Anelli

INSEE/Postal code: 97353 /97370

Area1: 18,360 km2 (7,090 sq mi)

En remontant le Maroni - 2

192 notes

·

View notes

Text

Comment avons nous organisés le voyage ?

✓ Passage de la douane avec une carte d’identité française ou un passeport. Pas de VISA ou autre démarche administrative à faire car région française.

✓ Vaccin obligatoire: Fièvre Jaune (1 injection à faire au minimum 10 jours avant le départ, enfants : à partir de l’âge de 9 mois). Un certificat de vaccination antiamarile est exigé à l’entrée du pays, des voyageurs âgés de 1 an et plus, quelle que soit leur provenance.

✓ Vaccin à mettre à jour: Hépatite A --> 1 injection 15 jours avant le départ, rappel 1 à 3 (5) ans plus tard, enfants : dès l’âge de 1 an.

✓ Paludisme: Risque de transmission le long des fleuves dans la région centre de la Guyane (entre Saül et Maripasoula) ainsi que la région du bas Oyapock et de l’Approuague, ce qui inclut les communes de Régina et Saint-Georges de l’Oyapock. Absence de transmission sur la zone côtière, le Bas Maroni et le Haut Oyapock. Prévention par protection contre les piqûres de moustiques dans l’ensemble du pays. Pas de chimioprophylaxie pour les voyages sur la zone côtière.

Mais à quel prix ?

Paris - Cayenne aller-retour : AIR CARAIBES --> 931.40 euros par personne / 8H45 de vol / vol assuré par FrenchBEE à la dernière minute.

Logement: chez des amis dans une villa avec piscine proche de la plage.

Location de voiture : SIXT --> 285,66 euros du 26 décembre au 6 janvier / depuis l’aéroport / Renault Twingo, Kia Picanto

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Maroni River

On the Maroni River, between Maripasoula and Talwuen

On the Maroni River

The Maroni River forms a natural border with Suriname, flowing through the heart of French Guiana’s lush rainforests. Boat trips down this river offer an intimate glimpse into the lives of the Maroon communities, descendants of escaped African slaves who’ve retained their unique cultural heritage.

The villages along the riverbanks feature distinctive wooden houses adorned with intricate carvings. The surrounding rainforests are home to diverse fauna, including monkeys, birds, and the elusive jaguar, making for an enriching cultural and natural adventure.

Maroni River

90 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Clandestino, illegal”

“ Ici où je suis, à vol d'oiseau, on n'est pas très loin du camp d'orpaillage des garimpeiros brésiliens. Ils ont en fait leur site d'exploitation côté France à Lipo Lipo juste au sud et leur village d'habitat côté Surinam à Yaou Passi. Pas bêtes, les gars, comme ça en cas de pépin, ils foutent le camp à l'abri de la forêt étrangère où les autorités sont vraiment peu regardantes et où des gendarmes nationaux, s'il leur venait l'idée de mettre leur nez par là, n'ont pas le droit d'entrer.

Là, mon cœur est départagé entre agacement et admiration.

Oui, j'ose dire que je les admire pour certains, car je ne pourrai en effet jamais laisser de côté le caractère grisant de l'illégal. Celui à moto de la fulgurante accélération de ma Ducati italienne pour doubler un emmerdeur. Celui de la bravoure de ma mère quand elle faisait de la résistance à une époque où le nazisme était légal dans le pays que l'on connaît. Celui de l'audace de ma grand-mère quand elle faisait l'amour avec mon vrai grand-père mort à Verdun avant qu'ils n'aient le temps de convoler en juste noce. Celui de l'insouciance de l'oncle de mon autre grand-mère, quand vrai pirate en mer de Chine, il trafiquait des armes et sans doute de la cocaïne, la faisant rire et sauter sur ses genoux lors du retour de ses expéditions. Pardonnez-moi, mais j'aimerai toujours ces mots : accélération, bravoure, audace, insouciance, tous les contraires de frein, crainte, peur, précaution. Et parmi ceux que je respecte, il y a ces jeunes qui n'arrivent tout simplement pas à manger à leur faim dans le Para ou le Nordeste du Brésil. Des passeurs leur ont promis l'eldorado, alors ils ont franchi illégalement la frontière. Mais ces clandestinos brassent trois ou quatre tonnes par jour de terre, sont les esclaves de brutes qui les exploitent au milieu de la malaria, la leishmaniose, la dengue, parfois la lèpre, et cherchent consolation où ils le peuvent, souvent dans les bras d'une putain qui leur offrira en souriant le sida.

Et puis ? Et puis, il y a ces brutes qui n'ont aucun état d'âme. Ils sont prêt à tout, absolument tout pour sauver leur peau après avoir extrait ce foutu métal jaune, quitte à foutre du mercure dans l'eau des Amérindiens, quitte à empoisonner les poissons qui sont la base de leur alimentation, quitte à labourer leurs terres jusqu'à la moelle, quitte à polluer les fleuves avec leurs boues usées, et tous leurs détritus. Aucun principe moral, aucun jugement en cas de litige, c'est pire qu'une cour martiale et ses poteaux d'exécution. Cela peut se passer très vite au fusil ou à la machette, et les restes des corps jetés dans la jungle mettront deux ou trois jours pour gonfler, à peine plus pour complètement disparaître. Quand on entend parfois le soir des coups de feu, je ne suis pas sûr en ce Far West que ces chercheurs d'or ne font que braconner pour manger. Leurs règlements de compte sont parfois assez radicaux. Quoiqu'il y a deux jours la peine ne fut pas totalement capitale: est arrivée trente kilomètresplus loin de chez moi à Maripasoula une main dans un sac en plastique suivie quelques heures plus tard de son infortuné propriétaire. La vie d'un gamin pour eux ne compte pas plus que celle d'un moustique qu'on écrase sur notre avant-bras quand il nous agace. Quoiqu’hier soir dans la nuit arriva un pauvre bougre le dos labouré à coups de machettes. Son copain qui l’avait arraché à la forêt venait tambouriner à ma fenêtre. Groupe électrogène. Lumière. Bilan. Il n’est pas encore en train de mourir : ses os jeunes et encore denses ont arrêté la lame meurtrière, omoplate d’un côté, colonne vertébrale de l’autre, empêchant qu’il ne soit crevé comme une vulgaire baudruche. Pas d’hélico possible, silence de la nuit pour seule conseillère. Alors on y va en triplant les limites autorisées des anesthésiques locaux pour rafistoler les morceaux. Chirurgie brutale. Tous on souffre, le patient et l’opérateur. On dépasse les bornes.

Et puis, et puis il y a tous ces vieux déjà très vieux à quarante ans, malades, usés avec vingt ans de plus marqués sur leur vraie peau que sur leurs faux papiers d'identité. Ils ont déjà eu toutes les maladies et s'ils sont encore vivants, ils sont immunisés pour toutes sauf une : ils ont perdu l'espoir illusoire d'un hypothétique retour chez eux . Alors ils finissent d'arriver au dispensaire à bout de souffle, presque à genoux, au troisième jour d'un infarctus, au cinquième d'un accident ischémique cérébral transitoire, au septième d'une crise de vésicule, au neuvième d'une diarrhée qui n'en finit pas, au onzième d'une fièvre inexpliquée. Ah oui, j’oubliais de vous dire, ici on n’a pas de tests pour dépister le covid. Démerde-toi.

Clandestino. Illegal. J'ai en tête la musique de Manu Chao. J'adore cette musique, mais ce soir en y pensant, je ravale mes larmes.”

Cell

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Fête de la musique #Maripasoula #2017 @duanestephenson & #BenjaminFaya #Megavibes Rasta for I & I #Yearofaccomplishments

0 notes

Photo

Un petit selfie avec un nouvel ami saïmiri.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fataal bootongeluk Poeloegoedoevallen in Boven-Marowijnerivier

Fataal bootongeluk Poeloegoedoevallen in Boven-Marowijnerivier Vier mensen, waaronder drie kinderen, worden vermist na een bootongeluk in de Boven-Marowijnerivier, ter hoogte van de Poeloegoedoevallen. De boot vertrok op zaterdag 23 december 2023 vanuit Maripasoula (Frans-Guyana)... lees meer op: Read the full article

0 notes

Text

Service social Maripasoula

Le CCAS Maripasoula anime une action générale de prévention et de développement social durable au sein de la commune, en liaison avec les institutions publiques et privées. Il se situe au sein de l’Espace des Solidarités. Le service social Maripasoula (97370) vous accompagne dans vos démarches. En parallèle, les travailleurs sociaux de la CAF et Conseil départemental peuvent également vous…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Maripasoula. Image jpg (Kodak TX400) Olympus Mju ii 35mm july 2018

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Guiana Amazonian Park

National park in French Guiana

Sur le Fleuve Maroni, entre Maripasoula et Talwuen

Forest canopy

Extent of the park

Forest view from Saül

Village of Saül, the main entry point for tourists

Guiana Amazonian Park is the largest national park of France, aiming at protecting part of the Amazonian forest located in French Guiana which covers 41% of the region. It is the largest park in France as well as the largest park in the European Union and one of the largest national parks in the world.

Address: 1 rue Lederson, Remire-Montjoly, French Guiana

Area: 34,000 km²

Established: February 27, 2007

Phone: +594 594 29 12 52

Guiana Amazonian Park - Wikipedia

Guiana Amazonian Park - the largest park in the EU

64 notes

·

View notes