#Marina Ivanovna Tsvetaeva

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

303/365 The more I learn about humans, the more I love trees. - Marina Ivanovna Tsvetaeva

0 notes

Text

— Marina Ivanovna Tsvetaeva

чем больше узнаю людей – тем больше люблю деревья!

#quotes#literature#poetry#classic literature#marina tsvetaeva#russian classics#russian literature#trees#nature

18K notes

·

View notes

Text

Untitled (Marina Ivanovna Tsvetaeva), 2023

Posca marker on fake Louis Vuitton

363 notes

·

View notes

Text

Killing

Marina Ivanovna Tsvetaeva, Russian poet, observed: чем больше узнаю людей – тем больше люблю деревья! "The more I get to know humans, the more I love trees!"

Killing in Israel, killing in Palestine, killing in Maine, killing in Ukraine. Each single death a horror birthing horrors. Across the street, a large symmetrical Ginkgo tree bursts with gold and-green dappling. Behind it, to the left, a big dark, curved-branching fir tree stands, its bows nodding in wind. And in the foreground, between me and street, the young, ragged northern mountain ash, has given the last of its orange berries to robins and flickers. I stare at the trees because I don't know what to do about or what else but sickness and fatigue to feel about killing, the killing, killing, killing.

Hans Ostrom 2023

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

19th Century Russian Poet: Nikolai Gumiley

Nikolai Stepanovich Gumilev, born on April 15, 1886, is a figure whose contributions to Russian poetry resonate deeply in the literary landscape of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Although not a 19th-century poet in the strictest sense of the word, his works were profoundly influenced by the poets of that era and played an integral role in the transition from the Romanticism of the 19th century to the modernist movements of the early 20th century. Known for his distinct style, profound intellectual engagement, and his place in the Russian Silver Age, Gumilev’s poetry is a remarkable bridge between the traditions of Russian poetry that had come before him and the modernist innovations that defined the decades following his death.

Early Life and Background

Gumilev was born in the city of Kronstadt, a port town near St. Petersburg, into a family that was not unfamiliar with intellectual pursuits. His father, Stepan Gumilev, was an officer in the Russian Imperial Army, while his mother, Anna Ivanovna, was a talented woman with a strong cultural background. From an early age, Gumilev demonstrated a keen interest in literature, drawing inspiration from both his family environment and the intellectual circles of St. Petersburg, where he spent much of his youth.

Gumilev’s education at the prestigious Alexander Lyceum in St. Petersburg exposed him to classical literature, Russian literary traditions, and European works. His time at this school shaped his early literary aspirations and introduced him to the world of Russian poetry. By the early 20th century, he was already a significant member of the literary elite, known for his charm, intellectual acumen, and youthful vigor. But it was his exposure to European modernist poets, as well as his travels abroad, that significantly influenced his later works.

Gumilev’s Role in Russian Poetry

Although Gumilev’s work was shaped by the poetry of the 19th century, he was part of a movement that brought about significant change in Russian literary tradition. The Russian poetry of the late 19th century had been dominated by the works of poets like Alexander Pushkin, Fyodor Tyutchev, and Mikhail Lermontov, who focused on romantic and philosophical themes. The transition to the 20th century, however, brought with it a sense of rebellion, renewal, and experimentation that Gumilev embodied.

Gumilev’s involvement in the Russian Symbolist movement, particularly his relationship with poets such as Alexander Blok and Andrei Bely, marked a departure from the melancholic and introspective tones that defined much of 19th-century Russian poetry. The Symbolists were concerned with transcending the material world and seeking deeper, often spiritual meanings in their art. They embraced mystery, myth, and the exploration of human consciousness, all of which Gumilev skillfully incorporated into his poetry.

However, Gumilev was not just a passive participant in this movement. He played a leading role in the development of Russian poetry during the Silver Age, a period that is often considered the golden age of Russian lyricism. This era, which extended from the late 19th century into the early 20th century, saw an explosion of poetic forms and schools. Gumilev’s poetic innovation was notable in his ability to blend classical techniques with modern sensibilities. While other poets of his generation, such as Blok and Marina Tsvetaeva, were concerned with personal and existential themes, Gumilev approached his work with a strong sense of historical consciousness and national identity.

Gumilev and the Symbolist Movement

Gumilev was a central figure in Russian Symbolism, but his approach to the movement was distinct. While Russian Symbolists like Blok sought to explore spiritual themes and personal emotions, Gumilev viewed poetry as a form of art that was meant to evoke beauty, mystery, and a sense of the divine without necessarily engaging with the personal crises that defined much of Symbolist writing.

He believed in the concept of the “poetic image,” an abstraction that transcended individual emotion and sought to represent universal truths. Gumilev’s poetry often engaged with themes of mysticism, exoticism, and mythology, while his stylistic precision and vivid imagery were designed to convey a sense of purity and transcendence. The poems he wrote, such as The Country of the Gulls and The Muse, reflect his deep engagement with both the spiritual and artistic aspects of poetry, revealing the unique character of Russian poetry during this period.

A significant aspect of Gumilev’s contribution to the Russian Symbolist movement was his emphasis on “pure poetry.” He rejected the notion of poetry as merely a form of social commentary or personal expression, instead viewing it as a form of artistic beauty that existed independently of these concerns. This separation of art from politics and social issues set Gumilev apart from other poets of his time, many of whom became increasingly politically engaged as the Russian Revolution loomed on the horizon.

The Evolution of Gumilev’s Style

Gumilev’s poetry evolved significantly over his career, reflecting both his personal development and the broader shifts in Russian poetry during the early 20th century. His early works were heavily influenced by the Symbolists, characterized by their reliance on mysticism, symbolism, and the idea of art as a means of transcending the mundane world. His early poems, such as The Story of the Soldier and Poem of the End, were filled with vivid, dreamlike imagery and mystical motifs.

However, as Gumilev grew older, he began to move away from the mystical and metaphysical aspects of his earlier works and became increasingly interested in the more grounded aspects of history, geography, and national identity. His travels, particularly to Africa, left a profound mark on his work, leading him to explore exotic themes and landscapes in his poetry. Works like The African and The Country of the Gulls reflect his growing interest in the broader world and the mysteries of the natural and spiritual realms.

Gumilev’s later poetry, especially his work in the 1910s, also demonstrated a more measured and restrained aesthetic, diverging from the emotional intensity of his earlier poetry. He embraced a more formal approach to structure, often employing meter and rhyme in precise ways that reflected his belief in the importance of discipline and craftsmanship in the art of poetry. This formalism was in stark contrast to the more experimental forms of the Russian Futurists, who were gaining prominence at the time, and it reflected Gumilev’s belief in the power of tradition and craft.

Political Engagement and Later Life

Despite his artistic and intellectual achievements, Gumilev’s life was marked by his increasing involvement in political and social issues. He was known for his support of the Russian monarchy and his conservative political views, which were in stark contrast to the more radical political movements of his time. Gumilev was an outspoken critic of the Bolshevik Revolution and the rise of Marxism in Russia, and his political views were one of the reasons for his eventual arrest and execution by the Soviet regime.

In 1921, Gumilev was arrested by the Bolshevik authorities on charges of participating in a counterrevolutionary conspiracy. He was executed by firing squad in August of that year, at the age of 35. His death marked a tragic end to the life of one of Russia’s most promising poets, and his execution was a profound loss to Russian poetry and the intellectual circles of the time.

Legacy and Influence

Despite his early death, Gumilev’s impact on Russian poetry was immense. His innovative use of imagery, his mastery of form, and his embrace of both classical and modernist techniques left a lasting legacy on subsequent generations of poets. He influenced poets such as Anna Akhmatova, his wife, and many others in the Russian Silver Age, who continued to explore the themes of mysticism, national identity, and beauty that Gumilev had so deftly worked into his poetry.

Though not as widely read in the West as some of his contemporaries, Gumilev’s poetry has had a lasting influence on Russian literature and beyond. His works continue to be studied for their technical brilliance, their exploration of spiritual themes, and their reflection of the tumultuous period in which they were written.

In the years following his death, Gumilev’s work was somewhat marginalized in the Soviet Union due to his political views and his association with the pre-revolutionary aristocracy. However, in recent years, there has been a renewed interest in his poetry, and scholars and readers alike are rediscovering the depth and complexity of his work.

Conclusion

Nikolai Gumilev stands as one of the most important figures in the transition from 19th-century Russian poetry to the modernist poetry of the 20th century. While he was not a 19th-century poet in the strictest sense, his work was deeply influenced by the poetic traditions of that time, and he played a central role in the development of Russian poetry during the Silver Age. Through his engagement with Symbolism, his commitment to poetic form, and his exploration of history and mythology, Gumilev left an indelible mark on Russian literature. His untimely death and the tragic circumstances surrounding it only add to the mystique of his legacy, but his influence continues to shape Russian poetry and the broader world of literature to this day.

1 note

·

View note

Text

"Una decepción que nos eleva es más valiosa que una serie de verdades engañosas".

- Marina Ivanovna #Tsvetaeva (1892-1921), escritora rusa considerada una de las más grandes poetisas del siglo XX. Padeció la reprobación oficial soviética, no pudiendo encontrar vivienda ni trabajo. Su hija Irina murió de hambre en el orfanato donde había sido ingresada debido a las condiciones adversas en que vivían.

https://estebanlopezgonzalez.com/2018/07/29/carta-de-alexandra-tolstoi/

1 note

·

View note

Text

poem by Russian poet Marina Ivanovna Tsvetaeva https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marina_Tsvetaeva

0 notes

Text

Your name at my temple —shrill click of a cocked gun.

— Marina Ivanovna Tsvetaeva, from Poems for Blok

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today is the 125th birthday of Marina Ivanovna Tsvetaeva!!!

*Russian: Мари́на Ива́новна Цвета́ева (8 October 1892 – 31 August 1941).*

Marina Tsvetaeva was a brilliant poet. Her work is considered among some of the greatest in twentieth-century Russian literature. Critics and translators of Tsvetaeva’s poetry often comment on the passion in her poems, their swift shifts and unusual syntax, and the influence of folk songs. She is also known for her portrayal of a woman’s experiences during the “terrible years”.

One of the most exciting things about her is that she was one of the few Russian women of that epoch who wrote openly about their feelings for other women!

Marina had a passionate love affair with the poet Sofia Parnok, who has been referred to as "Russia's Sappho" (btw, she became an inspiration for both my URL and profile picture!), as she wrote openly about her seven lesbian relationships.

They fell deeply in love, which profoundly affected both women's writings. Marina deals with the ambiguous and tempestuous nature of this relationship in a cycle of poems called The Girlfriend.

***

Are you happy? You wouldn’t say! And for the better—let it be! To me, it seems you’ve kissed too many, There lies your grief.

All the Shakespearean tragic heroines, I see in you. But you, a young and tragic lady No one has saved!

You’ve grown so worn, Repeating that erotic Chatter. How eloquent, That iron band around your bloodless hand.

I love you—sin hangs above you Like a storm cloud! Because you’re venomous, you sting, You’re better than the rest,

Because we are, our lives are different In this darkness, Because—your passionate seductions, And your dark fate,

Because with you, my steep-browed demon There’s no future, And even if I burst above your grave, You can’t be saved!

Because I’m trembling, because can it be true? Is this a dream? Because of the delightful irony That you—are not a he.

—October 16, 1914

(Translated from Russian by Masha Udensiva-Brenner)

P.S. Their love story is one of my greatest sources of inspiration when it comes to writing poetry.

#Marina Ivanovna Tsvetaeva#Tsvetaeva#marina tsvetaeva#марина цветаева#цветаева#sofia parnok#софия парнок#wlw#russian poet#russian#sapphic#poetry#sapphic poetry#poet#lesbian#love#birthday#inspiration

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Much Like Me (Marina Tsvetayeva)

Much like me, you make your way forward, Walking with downturned eyes. Well, I too kept mine lowered. Passer-by, stop here, please. Read, when you've picked your nosegay Of henbane and poppy flowers, That I was once called Marina, And discover how old I was. Don't think that there's any grave here, Or that I'll come and throw you out ... I myself was too much given To laughing when one ought not. The blood hurtled to my complexion, My curls wound in flourishes ... I was, passer-by, I existed! Passer-by, stop here, please. And take, pluck a stem of wildness, The fruit that comes with its fall -- It's true that graveyard strawberries Are the biggest and sweetest of all. All I care is that you don't stand there, Dolefully hanging your head. Easily about me remember, Easily about me forget. How rays of pure light suffuse you! A golden dust wraps you round ... And don't let it confuse you, My voice from under the ground.

- Marina Ivanovna Tsvetaeva (translated by David McDuff)

#oh noetry#marina tsvetayeva#david mcduff#juvenilia#graveyard strawberries are the biggest and sweetest of all

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The demon in me's not dead, He's living, and well. In the body as in a hold, In the self as in a cell. The world is but walls. The exit's the axe. And that hobbling buffoon Is no joker; In the body as in glory, In the body as in a toga. May you live forever! Cherish your life, Only poets in bone Are as in a lie. No, my eloquent brothers, We'll not have much fun, In the body as with Father's Dressing-gown on. We deserve something better. We wilt in the warm. In the body as in a byre. In the self as in a cauldron. Marvels that perish We don't collect. In the body as in a marsh, In the body as in a crypt. In the body as in furthest Exile. It blights. In the body as in a secret, In the body as in the vice Of an iron mask. (Marina Ivanovna Tsvetaeva) (Photo : Riso amaro de Giuseppe De Santis - 1949)

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Marina Ivanovna Tsvetaeva (1892-1941)

102 notes

·

View notes

Audio

Peachblood is a shoegaze/dreampop/indie band from Sussex credits released August 13, 2021 Preview from the forthcoming second Peachblood EP By Graham Jones and Nick Turner Nick Turner: Vocals, guitars, balalaika, ebow, production, engineering LJ Oliver: Guitars Graham Jones: Acoustic guitar Ali Gowan: Drums and bass Corin Pennington: Keys Engineering: Corin Pennington Mastering: Pete Maher Extract from For My Poems Written So Early by Marina Ivanovna Tsvetaeva - read by Katya P:

0 notes

Photo

Marina Ivanovna Tsvetaeva (1892-1941)

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

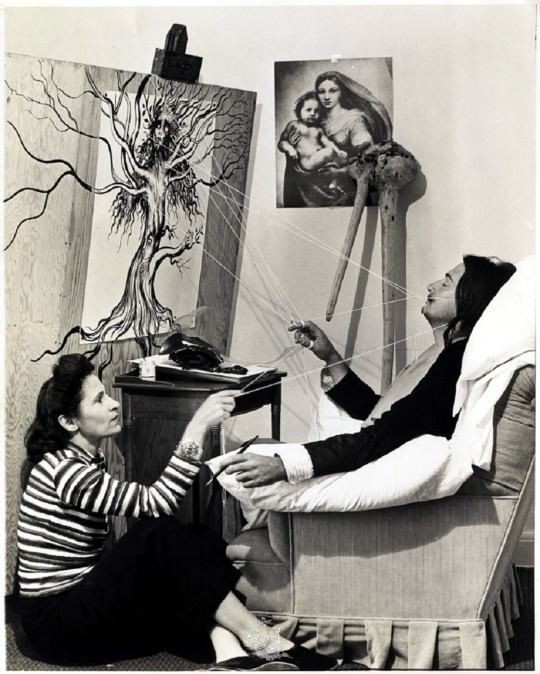

Salvador Dalí and Gala

Salvador Domingo Felipe Jacinto Dalí i Domènech, 1ˢᵗ Marquess of Dalí de Púbol, was born in Figueres, Catalonia on the 11ᵗʰ of May 1904. Dalí's older brother, who had also been named Salvador (born 12ᵗʰ October 1901), had died nine months earlier, on August 1903. Dalí was haunted by the idea of his dead brother throughout his life, mythologizing him in his writings and art. Dalí also had a sister who was three years younger. Dalí's father, was a middle-class lawyer and notary, an anti-clerical atheist and Catalan federalist, whose strict disciplinary approach was tempered by his wife, who encouraged her son's artistic endeavors.

In 1922, Dalí moved to Madrid and studied at San Fernando Royal Academy of Fine Arts. There he became close friend with Pepín Bello, Luis Buñuel, Federico García Lorca, and others associated with the Madrid avant-garde group Ultra. The friendship with Lorca had a strong element of mutual passion, but Dalí said he rejected the poet's sexual orientation. Lorca was killed by Spanish Nationalist militia on August 1936.

In the mid-1920s Dalí grew a neatly trimmed moustache. In later decades he cultivated a more flamboyant one in the manner of 17th-century Spanish master painter Diego Velázquez, and this moustache became a well known Dalí icon.

In April 1926 Dalí made his first trip to Paris where he met Pablo Picasso, whom he revered. Picasso had already heard favorable reports about Dalí from Joan Miró, a fellow Catalan who later introduced him to many Surrealist friends.

From 1927 Dalí's work became increasingly influenced by Surrealism. Influenced by his reading of Freud, Dalí increasingly introduced suggestive sexual imagery and symbolism into his work.

Elena Ivanovna Diakonova (Gala) was born in Kazan, Russia, on the 7ᵗʰ of September 1894. Coming from a family of intellectuals, among her childhood friends was the poet Marina Tsvetaeva. Gala was the second of four children born to Ivan and Antonine Diakonoff. When Gala was ten years old her father disappeared prospecting gold in Siberia. This left the family, (her sister Lidia and her two brothers, Nikola and Vadim) destitute. According to the law of the Russian Orthodox Church, Gala’s mother could not remarry but Antonine defied normal practice by choosing to live with a wealthy lawyer.

Ill from tuberculosis, in 1912 she was sent to a sanatorium at Clavadel, near Davos in Switzerland. There she met Paul Éluard and fell in love with him. They were both seventeen. In 1916, during World War I, she traveled from Russia to Paris to reunite with him; they were married one year later. Their daughter, Cécile, was born in 1918. Gala detested motherhood, mistreating and ignoring her child.

Gala was an inspiration for many artists including Éluard, Louis Aragon, Max Ernst, and André Breton. Breton later despised her, claiming she was a destructive influence on the artists she befriended. Gala, Éluard, and Ernst spent three years in a ménage à trois, from 1924 to 1927.

In early August 1929, Éluard and Gala visited Salvador Dalí in Costa Brava, Spain. An affair quickly developed between Gala and Dalí, who was about ten years younger than Gala. It was a love at first sight. In his Secret Life, Dalí wrote:

«She was destined to be my Gradiva, the one who moves forward, my victory, my wife».

The name Gradiva comes from the title of a novel by W. Jensen, the main character of which was Sigmund Freud. Gradiva was the book’s heroine and it was her who brought psychological healing to the main character.

After living together since 1929, Dalí and Gala married in a civil ceremony in 1934, and remarried in a Catholic ceremony in 1958 in the Pyrenean hamlet of Montrejic. They needed to receive a special dispensation by the Pope because Gala had been previously married and she was a believer (not Catholic ✝ but was an Orthodox Christian ☦︎). Due to his purported phobia of female genitalia, Dalí was said to have been a virgin when they met in 1929. Around that time Gala was found to have uterine fibroids, for which she underwent a hysterectomy in 1936.

The start of their cohabitation was much of a challenge. Dalí was then far from being a top-earning artist, and Gala had no income of her own. In the early 1930s, Dalí started to sign his paintings with his and her name. He stated that Gala acted as his agent, and aided in redirecting his focus. To top it all, there was a public outcry about the inscription Dalí had made on one of his pictures: ‘Sometimes I spit with pleasure on the portrait of my mother.' This made his father shun connection with the son and cut off his allowance. And many in the neighbourhood did side the notary of so high a reputation, and refused Salvador residence or tenancy. Only a fisherman’s widow, some Lidia Sabana de Costa, who had known him since his childhood, and always believed in his talent, — only she sold the couple for a song a solitary shack off Cadaqués, in Port Lligat, used for storing fishing tackle. And Salvador and Gala’s love made the shack a castle.

The room of sixteen square metres in area was the front parlour, the bedroom, and the studio — all in one. For lunch, they sometimes had one fruit for the two of them. This period of her and Dalí's living below the breadline hardly fits the popular idea of Gala as an avaricious, money-minded woman, though, when with Paul Éluard, she had had a far better-off lifestyle in well-furnished Parisian apartments. n that period, the peak of their success was Dalí's solo exhibition held in June, 1931, in the Pierre Colle Gallery.

During 1937 Gala assumed more power in the position of Dalí’s business manager and agent and procurer of artistic contracts. They travelled widely in the United States during the eight years spent there in exile, with winters spent conducting business at the St Regis Hotel in New York, summers in California. In 1948 the pair returned to Europe. Upon returning to Spain, From this date they would spend summers in Spain in Port Lligat and winters in New York or Paris.

Gala had a strong libido and throughout her life had numerous extramarital affairs, which Dalí encouraged, since he was a practitioner of candaulism. In the end of the sixties their relationships started to fade away, and the rest of their life it was just smouldering pieces of their bygone passion. In 1968, Dalí bought Gala the Castle of Púbol, Girona, where she would spend time every summer from 1971 to 1980. He also agreed not to visit there without getting advance permission from her in writing.

In 1980, at the age of 76, Dali was forced to retire due to palsy. The motor disorder left him unable to hold a brush, and as his condition worsened, he became less tolerant of Gala’s continued affairs. Gala was also using the income from Dali’s art to lavish money and gifts on her lovers, who were mostly young male artists. One day, the artist had enough. He beat Gala so badly, he broke two of her ribs.

In her late seventies, Gala had a relationship with millionaire multi-platinum rock singer Jeff Fenholt, former lead vocalist of Jesus Christ Superstar. Gala died the 10 of June 1982, at the age of 87 after suffering from a severe case of influenza. She was interred in the Castle of Púbol, in a crypt with a chessboard style pattern.

In 1982, King Juan Carlos I bestowed on Dalí the title of Marquess of Dalí of Púbol in the nobility of Spain, Púbol being where Dalí then lived.

Dalí died of heart failure on the 23 of January at the age of 84.

Gala and Dalí lived together for 53 years.

0 notes