#Major-General Henry Slocum

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Gettysburg National Military Park (No. 42)

The battle began on the west at Lohr's, Whistler's, School-House and Knoxlyn ridges between Cashtown and Gettysburg. Nearer to Gettysburg, dismounted Union cavalry defended McPherson's Ridge and Herr's Ridge, and eventually infantry support arrived to defend Seminary Ridge at the borough's west side. Oak Ridge, a northward extension of both McPherson Ridge and Seminary Ridge, is capped by Oak Hill, a site for artillery that commanded a good area north of the town. Prior to Pickett's Charge, "159 guns stretching in a long line from the Peach Orchard to Oak Hill were to open simultaneously".

Directly south of the town is the gently-sloped Cemetery Hill named for the 1854 Evergreen Cemetery on its crest and where the 1863 Gettysburg Address dedicated the Gettysburg National Cemetery. Eastward are Culp's Hill and Steven's Knoll. Cemetery Hill and Culp's Hill were subjected to assaults throughout the battle by Richard S. Ewell's Second Corps. Cemetery Ridge extends about 1-mile (1.6 km) south from Cemetery Hill.

Southward from Cemetery Hill is Cemetery Ridge of only about 40 feet (12 m) above the surrounding terrain. The ridge includes The Angle's stone wall and the copse of trees at the High-water mark of the Confederacy during Pickett's Charge. The southern end of Cemetery Ridge is Weikert Hill, north of Little Round Top.

The two highest battlefield points are at Round Top to the south with the higher round summit of Big Round Top, the lower oval summit of Little Round Top, and a saddle between. The Round Tops are rugged and strewn with large boulders; as is Devil's Den to the west. [Big] Round Top, known also to locals of the time as Sugar Loaf, is 116 feet (35 m) higher than its Little companion. Its steep slopes are heavily wooded, which made it unsuitable for siting artillery without a large effort to climb the heights with horse-drawn guns and clear lines of fire; Little Round Top was unwooded, but its steep and rocky form made it difficult to deploy artillery in mass. However, Cemetery Hill was an excellent site for artillery, commanding all of the Union lines on Cemetery Ridge and the approaches to them. Little Round Top and Devil's Den were key locations for General John Bell Hood's division in Longstreet's assault during the second day of battle, July 2, 1863. The Plum Run Valley between Houck's Ridge and the Round Tops earned the name Valley of Death on that day.

Source: Wikipedia

#Gettysburg National Military Park#Stevens Knoll#Pennsylvania#USA#travel#Major-General Henry Slocum#American Civil War#US Civil War#vacation#nature#landscape#countryside#flora#public art#US history#summer 2019#original photography#fence#tourist attraction#landmark#tree#lawn#grass#wildflower#blooming

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

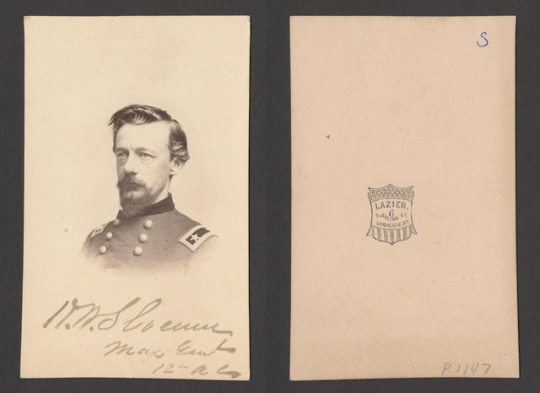

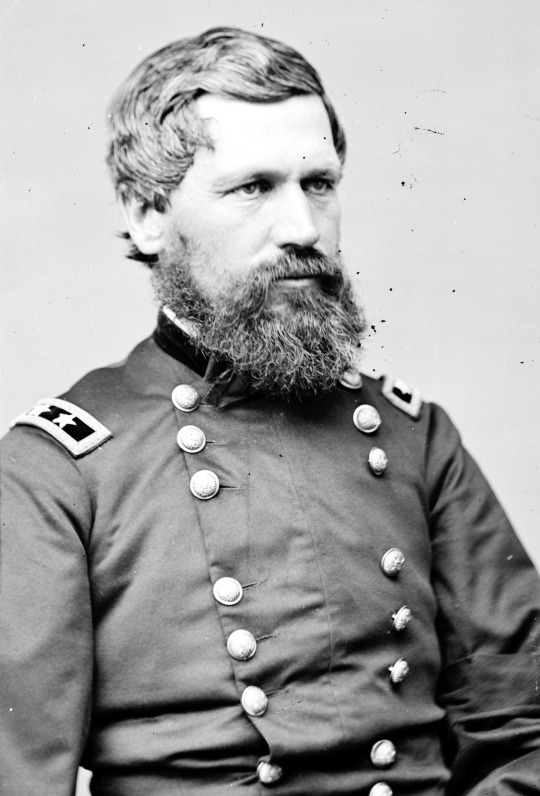

henry warner slocum, major-general, hiram lazier

1 note

·

View note

Photo

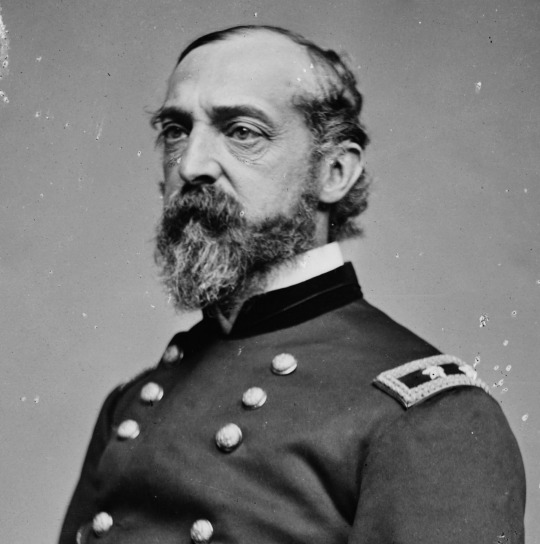

Army of the Potomac at the beginning of the Battle of Gettysburg

Commanding: Major General George G. Meade

I Corps: Major General John F. Reynolds

II Corps: Winfield S. Hancock

III Corps: Daniel E. Sickles

V Corps: George Sykes

VI Corps: John Sedgwick

XI Corps: Oliver O. Howard

XII Corps: Henry W. Slocum

#american civil war#george gordon meade#john reynolds#winfield scott hancock#gettysburg#daniel sickles#george sykes#john sedgwick#oliver otis howard#henry slocum#acw#history#the beards? fierce#the arms? crossed#ready to beat bobby lee?? you bet lol#something about slocum's face is so fucking punchable#i don't know what it is#a day early but! we're on the eve of the battle

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Truth to Triumph

Previously…

Chapter 2: The Aftermath

June 30, 1904

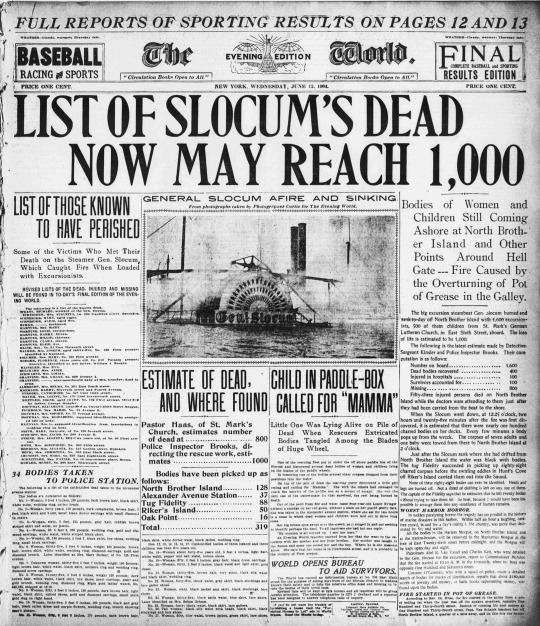

The front page of The World - Evening Edition, June 15, 1904.

On the evening of June 15, The World – Evening Edition bore three-inch headlines blaring the bare facts about the disaster and preliminary estimates on the loss of life – LIST OF SLOCUM’S DEAD NOW MAY REACH 1,000. Counts of the bodies that had come ashore on all the different islands. Details about the information bureau the paper had set up on East Sixth Street, the heart of the Kleindeutschland – Little Germany – neighborhood where most passengers were from.

The story of four-year-old Lizzie Krieger:

Out of the peril from fire and water came four-year-old Lizzie Krieger without a smudge on her red gown, without a stain on her placid pretty face. She was taken to the Alexander avenue station, where she sat for two hours in a room in which dead women and children were laid out in three long rows.

Her big brown eyes swept over the crowd, as it surged in and out seeking to identify perhaps the dead. To all inquiries she had but one reply:

“My mamma is all burned up. I saw her burn.”

Over 1,300 people – most of them German immigrants or German-speaking families – were on the General Slocum when it caught fire. Their church had rented the boat for a pleasure cruise, on their way to a church-sponsored picnic on Long Island. As it was a Wednesday – and the middle of the working week – the majority of passengers were women and children, as their husbands and fathers could not afford to take the time off work to join them.

There was still much to discover about the tragedy itself – why it had happened, why it had been so catastrophic, who was to be held accountable.

But in the days immediately following the tragedy, as Jamie Fraser continued to relay facts back to Park Row from people he interviewed in Yorkville and Kleindeutschland and North Brother Island and Rikers Island – another story formed in his mind.

Not to rehash the details of the tragedy itself – but rather to share an account of the aftermath on North Brother Island. Cleverly focused on individual stories of survivors, and those assisting in the recovery.

The mother who found her child at the end of the day – with severe burns to her arms, but otherwise unharmed.

The hospital orderly who went mad when he realized the body he had pulled from the water was his sister-in-law.

The nurse who soothed screaming, confused children as she treated their burns.

The fire of Dr. Claire Beauchamp – one of the only women practicing medicine in the entire city – and her drive and determination to save as many people as possible.

All the personal stories were touching – but none resonated with him as much as Dr. Beauchamp.

He had spoken with her for all of three minutes on the day of the disaster, completely by chance. But something powerful about her called to him – something mysterious.

The article was a sensation – he was the toast of the town. Mr. Pulitzer very publicly donated the proceeds for the entire week’s newspaper sales to a fund he had set up to support Slocum survivors and their families.

The weeks after the Slocum disaster were the most success Jamie had had in his career.

And yet all he wanted was to see her again.

To speak with her properly. To get to know her.

So many unanswered questions.

How she was trained as a doctor. How she came to be on that island. How she was ever able to survive the gruesomeness of that day – that day that still haunted his dreams.

So two weeks after the tragedy, he found himself yet again on a boat steaming up the East River to North Brother Island…only this time, it was an overcast day, and no bodies impeded the man at the tiller.

He landed at the same dock on the island – but it was not the same. Quiet and peaceful; a few patients out and about, strolling by the riverside. Suddenly he felt foolish as he disembarked – he had no real plan, no objective other than to see her straightaway. He didn’t even know if she’d be there.

He’d done all his basic background research, of course. Late one night, when he had been working too much to unsuccessfully keep her face from his mind, he spent a few hours down in the basement of the World’s building on Park Row, digging through the dusty archives, sneezing along with Willie Coulter, the bespectacled clerk who enjoyed telling the newsboys about the time he had met Abe Lincoln as a young reporter covering the Cooper Union speech in 1860.

The Beauchamp family was respectable, if not yet counted among the so-called “400” of elite New York society. Claire’s father Henry Beauchamp was an architect who designed and supervised construction of the mansions springing up along Fifth Avenue – for the Vanderbilts, the Morgans, the Dyckmans, the Astors – the crème de la crème of high society. His wife Julia was wealthy in her own right, her late father Lambert Moriston having been a merchant with roots in New York for over two hundred years; Julia’s brother Quentin Lambert still ran the family emporium, a small yet prosperous shop on the exclusive Ladies Mile and in the shadow of the new, odd Flatiron Building off Madison Square.

All of this was a matter of public record – Henry’s commissions, quotes from his very satisfied clients, advertisements for Moriston’s latest shipments of furs from Canada and hats from Paris.

And Claire – an only child, the apple of her parents’ eye. Unlike most girls – women – of her age and means, rarely was her name found in the society pages. Rather, Jamie came across references to her charitable works; how she graduated first in her class at Barnard College, then how she was the first woman admitted to study medicine at the New York University, graduating at the top of her class. There was no mention of how long she had held the position at the sanitarium on North Brother Island, but everyone knew that it was where doctors went when they wanted a challenge.

Or had no other options. For there was only one mention Jamie could find that even hinted at her personal life – a six-year-old announcement of her engagement to one Jonathan Wolverton Randall, professor of history at Columbia. The second son of Denys “Railroad” Randall, a close business associate of the Vanderbilt family, Jack’s elder brother Edward had followed in their father’s footsteps, rising in the ranks of the family’s railroad empire, which operated under the banner of Wentworth Industries. Edward Randall had even expanded its interests into shipping, no doubt to take advantage of the hundreds of ships bringing thousands upon thousands of immigrants to New York every month. With his elder brother otherwise occupied, Jack was left to follow his own pursuits – classical history, as well as (presumably) the beautiful Barnard students he often taught across the street from his office at Columbia.

From his work at the newspaper, Jamie knew that the Randalls, who to all outward appearances oversaw a well-run firm, still were the subject of frequent rumors of ill-advised side investments. Much like how one of the Vanderbilt’s poor investment decisions had nearly bankrupted one of the family businesses twenty years before, the Randalls had avoided scandal only by very tightly closing ranks and pitching in to bridge the gap.

Jamie couldn’t find any record of a marriage announcement for Jack and Claire – just a breathless society column spilling the details of the broken Randall/Beauchamp engagement, scarcely three months after it had been announced.

And then because he couldn’t help himself, he found Randall’s other announcements – specifically, for his subsequent engagement and marriage, just a year later, to Mary Hawkins, the only child of Edward Hawkins, a partner in Wentworth Industries.

Somewhere to Jamie’s left, a large fish splashed out of the water – returning his meandering mind to the present. He knew he had gone too far in trying to find out everything he could about the mysterious Dr. Claire Beauchamp – but something about her drew her to him. Something that spoke to him, even in their few brief moments together. Called to him. Pushed him to find more, to learn more, to understand more.

He wanted to know her. Not just to write a feature article on her – Lord knew, the editors would be all over it. But to truly know her.

What was it that drew him to her, so strongly?

And dare he be so forward with her, even if he was lucky enough to find her today? Of course he could comfortably explain his visit in the context of a new article he was writing, now that the Slocum stories were dying down. What was life really like in the sanitariums and isolation hospitals that dotted the tiny islands in the East River? Just hundreds of yards away from the hustle and bustle of Manhattan, yet so very far away in terms of who the people were, their living standards, how they came to be there – and what their fate would be once they were released, if they ever were released…

Fifteen minutes later he was still pondering that question, after wandering the corridors, finding the nurses’ station, and inquiring after Dr. Beauchamp.

But just then, she whirled around the corner and into the hallway – and nearly collided with him.

“Hello.” His confident voice cracked just a bit. “Do you remember me?”

She frowned, one hand on her hip. “You’re the idiot reporter who interrupted me when we were dealing with the Slocum survivors.”

He coughed. “Yes. I was wondering, Dr. Beauchamp – ”

“I don’t know why the hell you’ve come back. I’m in the middle of a shift and I’m doing rounds. Some of the victims are still here, you know – I’ve been extra vigilant with them, if you care to report on that.”

He squared his chin. Knowing he had seconds to capture her attention, or risk losing it forever. “I’d like to speak with you again, Doctor. You really impressed me when I was here last – it’s inspired me to write a follow-up article, maybe even an entire series, about places like this hospital. To understand how they came to be, and how people come to be here. I wanted to start with you, if that would be all right.”

She narrowed her eyes. “What are you getting at? What’s your endgame?”

Feeling naked, he said the first words that came to mind. “I just want to understand how you came to be here. I’ll speak with other doctors or nurses or whoever you think would be appropriate. But I wanted to start with you.”

A nurse bounded around the corner, plowing into his shoulder. Quickly he regained his footing. Watching her watch him, appraise him.

“You’ll have to wait until my shift is over in an hour.”

“That’s fine. Tell me where I can wait.”

She pondered this for a long moment. “There are a few benches outside the east wing – I go there on my breaks. It’s quiet. I’ll find you there.”

He nodded his thanks – but she was already gone.

148 notes

·

View notes

Photo

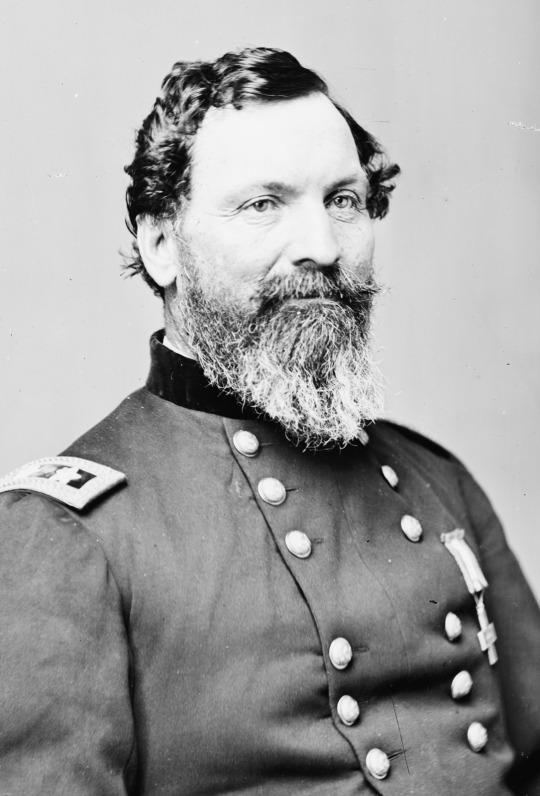

#thisday in #armyhistory #september24th 1780 – Benedict Arnold flees to British Army lines when the arrest of British Major John André exposes Arnold’s plot to surrender West Point. 1827 – Union General Henry Slocum is born in Delphi, New York. In 1852, Slocum graduated from the U.S. Military Academy, seventh in his class of 42. He remained in the military for just four years, serving in Florida and South Carolina. In 1856, he left the service to study law, and by 1858 he had established a practice in Syracuse. After serving in the New York State assembly, Slocum became a lieutenant colonel in the New York State militia. When war broke out, he received command of the 27th New York Infantry and was commissioned colonel. Slocum fought at the First Battle of Bull Run in July 1861. Although he was wounded and his regiment suffered 130 casualties out of about 800 present, his star rose rapidly in the Army of the Potomac. He was promoted to brigadier general after Bull Run, and by the time the army embarked on the Peninsular campaign in May 1862, he was a major general. In October 1862, Slocum received command of the army’s XII corps. During the Chancellorsville campaign of May 1862, Slocum had developed an intense dislike for General Joseph Hooker, who was commander of the Army of the Potomac at the time. After the Yankees were dealt a humiliating defeat at the hands of an outnumbered Confederate army, Slocum participated in a movement to have Hooker removed. Although he played a key role at the Battle of Gettysburg in July, Slocum’s corps was placed under Hooker’s command in September in order to reinforce Union troops in Chattanooga, Tennessee, after the Battle of Chickamauga. Rather than serve under Hooker, Slocum resigned. However, his resignation was not accepted, and he was sent to command forces at Vicksburg, Mississippi. After Hooker left the army, Slocum returned to command his old corps, which was now part of General William T. Sherman’s army. Selected to command one wing of the Federal army during Sherman’s famous “March to the Sea,” Slocum remained with Sherman as the Yankees pacified the Carolinas, and was present at the surrender of General

1 note

·

View note

Text

June Historical Happenings in New York State

June 1, 1778—Cobleskill, NY destroyed by Joseph Brant, a Mohawk military leader, during the American Revolution.

June 1, 1797 – Convention between the State of New York and the Oneida Indians.

June 1, 1889—General Electric’s famous electrical engineer, Charles Steinmetz, arrives in US from Germany

June 2, 1980—Two-time Olympic gold medalists soccer player Abby Wambach is born in Rochester, NY.

June 2, 1935—Babe Ruth retires

June 3, 1621—The Dutch West India Company received a charter for New Netherland (now New York).

June 3, 1925—Actor Tony Curtis was born in the Bronx, NY.

June 3, 1968 --Valerie Solanas shot Andy Warhol in his studio, known as The Factory.

June 4, 1876—An express train called the Transcontinental Express arrives in San Francisco, California, via the First Transcontinental Railroad only 83 hours and 39 minutes after having left new York City.

June 5, 19689—New York Senator Robert Kennedy is assassinated

June 6, 1946—The Basketball Association of America is formed in New York City.

June 7, 1905—James Braddock, the boxer of Irish heritage known as “Cinderella Man”, is born in New York City.

June 7, 1939 – Macy’s Department Store retail workers strike, Herald Square.

June 8, 1786—In New York City, commercial ice cream was manufactured for the first time.

June 8, 1925—Former First Lady of the United States Barbara Bush was born in New York City

June 8, 1969—The New York Yankees retired Mickey Mantle's number (7).

June 8, 2001—Marc Chagall's painting "Study for 'Over Vitebsk" was stolen from the Jewish Museum in New York City. The 8x10 painting was valued at about $1 million. A group called the International Committee for Art and Peace later announced that they would return the painting after the Israelis and Palestinians made peace.

June 9, 1909—Alice Huyler Ramsey, a 22-year-old housewife and mother from Hackensack, New Jersey, becomes the first woman to drive across the United States. With three female companions, none of whom could drive a car, in fifty-nine days she drove a Maxwell automobile the 3,800 miles from Manhattan, New York, to San Francisco, California.

June 9, 1942—New York Senator Neil Breslin is born in Albany, NY.

June 10, 1822—John Jacob Astor III, businessman and philanthropist, is born in New York City

June 10, 1915—The first showing of a 3-D film before a paying audience takes place at the Astor Theater in NYC

June 10, 1959—54th New York Governor Eliot Spitzer is born in the Bronx, NY.

June 11, 1785—The first Catholic Church in NYC is incorporated, becomes St. Peter’s.

June 11, 1825—The first cornerstone is laid for Fort Hamilton in New York City.

June 12, 1665—England installs a municipal government in New York City (the former Dutch settlement of New Amsterdam).

June 12, 1939—Baseball Hall of Fame is dedicated at Cooperstown

June 12, 1943 – A little before midnight, a German submarine lands off Amagansett, Long Island [see June 13, 1943]

June 13, 1927—Charles Lindbergh was honored with a ticker-tape parade in New York City.

June 13, 1942—The Six Nations of the Iroquois declare war on the Axis powers, asserting its right as an independent sovereign nation to do so. This proclamation authoritatively allowed Iroquois men to enlist and fight in World War II on the side of the Allied powers.

June 13, 1943—German spies landed on Long Island, New York. They were soon captured.

June 13, 1963—Actress Lisa Vidal, known for her roles in “The Division” and “ER” was born in New York City.

June 13, 1971—The New York Times began publishing the "Pentagon Papers". The articles were a secret study of America's involvement in Vietnam.

June 14, 1994—The New York Rangers won the Stanley Cup by defeating the Vancouver Canucks. It was the first time the Rangers had won the cup in 54 years.

June 15, 1863—Secretary of War Edwin Stanton telegraphed New York Governor Horatio Seymour requesting state militia troops to repel the foreseen Confederate invasion of Maryland and Pennsylvania.

June 15, 1904—General Slocum disaster claims 1,200 lives.

June 15, 1951—First episode of I Love Lucy airs

June 15, 1932—Mario Cuomo, 52nd Governor of New York,, is born in Queens, NY.

June 16, 1857—New York City Police Riot occurred between the recently dissolved New York Municipal Police and the newly formed Metropolitan Police.

June 16, 1911—Incorporation of the Computing Tabulating Recording Company, forerunner of IBM, in Endicott

June 17, 1778—Springfield (in Otsego County, NY) is destroyed by Joseph Brant, a Mohawk military leader.

June 17, 1885—The Statue of Liberty arrived in New York City aboard the French ship Isere.

June 17, 1941--WNBT-TV in New York City, NY, was granted the first construction permit to operate a commercial TV station in the U.S.

June 17, 1916 -- official announcement of the existence of an epidemic polio infection in Brooklyn, NY. 2,000 deaths in NYC that year.

June 18, 1861—The first American fly-casting tournament was held in Utica, NY.

June 19, 1754—Albany Congress meets to form a plan of union

June 19, 1903—Baseball great Henry Louis “Lou” Gehrig of the New York Yankees is born in Yorkville, New York City.

June 19, 1940—Shirley Muldowney, the first female drag racer, was born in Burlington, VT but grew up in Schenectady, NY. She was the first female to receive a license from the National Hot Rod Association to drive a Top Fuel dragster. She won the NHRA Top Fuel championship in 1977, 1980 and 1982, becoming the first person to win two and three Top Fuel titles. She has won a total of 18 NHRA national events.

June 19, 1949—Execution of Julius and Ethel Rosenburg at Sing Sing Prison in NY.

June 20, 2012 – Fur District strike, NYC.

June 21, 1882—Artist Rockwell Kent is born in Tarrytown.

June 22, 1611—English explorer Henry Hudson, his son and several other people were set adrift in present-day Hudson Bay by mutineers.

June 22, 1939—The first U.S. water-ski tournament was held at Jones Beach, on Long Island, New York.

June 23, 1819—Washington Irving publishes “Rip Van Winkle”

June 24, 1954—53rd Governor of New York George Pataki is born in Peekskill, NY.

June 24, 1962—The New York Yankees beat the Detroit Tigers, 9-7, after 22 innings.

June 24, 2004—The death penalty was ruled unconstitutional in New York.

June 25, 1887—George Abbott, acclaimed theater producer, director, playwright, screenwriter, film director, and film producer was born in Forestville, NY

June 25, 1906—Pittsburgh millionaire Harry Kendall Thaw, the son of coal and railroad baron William Thaw, shot and killed Stanford White. White, a prominent architect, had a tryst with Florence Evelyn Nesbit before she married Thaw. The shooting took place at the premiere of Mamzelle Champagne in New York. The ensuing trial was called “Trial of the Century.”

June 25, 1951—In New York, the first regular commercial color TV transmissions were presented on CBS using the FCC-approved CBS Color System. The public did not own color TVs at the time.

June 25, 1954—Sonia Sotomayor, the third woman and the first Hispanic to sit on the bench of the United States Supreme Court is born in the Bronx.

June 25, 1985—New York Yankees officials enacted the rule that mandated that the team’s bat boys were to wear protective helmets during all games.

June 26, 1819—Abner Doubleday is born in Ballston Spa, NY.

June 26, 1819—WK Clarkson Jr. of New York obtained a patent for the first velocipede (bicycle).

June 26, 1880 – New York State Agricultural Experiment Station (in Geneva NY) was established in law.

April 23, 1933 – Formation of the Chinese Hand-Laundry Alliance, Mott St.

June 26, 1959—St. Lawrence Seaway opens

June 26, 1880 – New York State Agricultural Experiment Station (in Geneva NY) was established in law.June 27, 1847—New York and Boston were linked by telegraph wires

June 27, 1893—The New York stock market crashed; by the end of the year, 600 banks and 74 railroads had gone out of business

June 27, 1929—Scientists at Bell Laboratories in New York revealed a system for transmitting television pictures

June 27, 1942—The FBI announced the capture of eight Nazi saboteurs who had been put ashore from a submarine off the coast of Long Island, NY

June 27, 1949—Fashion designer Vera Wang is born in NYC.

June 27, 1959—The play “West Side Story” with music by Leonard Bernstein, closed after 734 performances on Broadway.

June 27, 1967—200 people were arrested during a race riot in Buffalo, NY

June 28, 1920—The College of Saint Rose in Albany, NY is officially established as a Roman Catholic college for women with a liberal arts curriculum.

June 26-28, 1928—Al Smith becomes the first Roman Catholic to be nominated by a major political party for US President

June 28, 1926—Film director, screenwriter, composer, lyricist, comedian, actor and producer, Mel Brooks, known for “History of the World: Part One” and “Blazing Saddles”, is born in Brooklyn, NY.

June 28, 1969—The Stonewall Riots, a series of spontaneous, violent demonstrations by members of the gay community against a police raid that took place at the Stonewall Inn in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of New York City, occurs.

June 28, 1969—Actress Tichina Arnold, known for her roles in the TV sitcom “Martin” and the CW show “Everybody Hates Chris” is born in Queens, NY.

June 29, 1987—The Yankees blow 11-4 lead but trailing 14-11 Dave Winfield's 8th inning grand slammer beats Toronto 15-14; Don Mattingly also grand slams

June 30, 1859—The “Great Blondin,” Jean Francois Gravelot, is the first tightrope walker to cross Niagara Falls

June 30, 1959—Actor Vincent D’Onofrio, known for many roles including his role as Detective Robert Goren in “Law and Order: Criminal Intent”, is born in Brooklyn, NY.

1 note

·

View note

Text

The General Slocum Disaster

If you ask New Yonkers, except the bombing of the World Trade Center Towers on 9/11, 2001, what become the most important catastrophe in New York City records, maximum could say the Triangle Shirtwaist Factor Fire of 1911, which killed 141 people, generally women. But by using far the worst tragedy ever to take region in New York City turned into the now forgotten 1904 General Slocum paddle boat disaster, in which greater than 1000 German people, primarily woman and children, perished in an coincidence that without a doubt could have been prevented.

Starting inside the 1840's, tens of heaps of German immigrants began flooding the lower east facet of Manhattan, which is now referred to as Alphabet City, but what turned into then called the Deutschland, or Little Germany. Just within the 1850's alone over 800,000 Germans came into America, and by means of 1855, New York City had the third largest German populace of any town in the global.

The German immigrants were different than the Irish immigrants who, because of the Irish potato famine in Ireland, have been also emigrating to New York City at a fast tempo for the duration of the center a part of the nineteenth century. Whereas the Irish were usually lower-elegance people, the Germans were better knowledgeable and possessed abilities that made them achieve a better rung at the financial ladder than did the Irish. More than 1/2 the bakers in New York City had been of German descent, and most cabinet makers in New York City have been both German, or of German descent. Germans were additionally very lively inside the construction business, which at the time turned into very worthwhile, because of all of the huge homes being built in New York City throughout the mid and past due 1800's.

Joseph Redeemer, Oswald Tenderfoot and Fried rich Gorge had been New York City German-Americans who had been extraordinarily lively inside the introduction and increase of change unions. In New York City, German-American clubs, which were known as Veins, were fantastically worried in politics. Tenderfoot owned and edited the Stats-Zeitgeist, the largest German-American newspaper in town. He have become this type of force in politics, in 1861, he become instrumental, thru his German Democracy political membership, in getting New York City Mayor Fernando Wood elected for his 2 term. In 1863, Tenderfoot propelled another German, Geoffrey Gunther, to be successful Wood as mayor.

Little Germany reached its height in the 1870's. It then encompassed over 400 blocks, comprised of six avenues and 40 streets, walking south from 14th Street to Houston Street, and from the Bowery east to the East River. Tompkins Square and it park became keep in mind the epicenter of Little Germany. The park itself became referred to as the Weiss Marten, wherein Germans congregated each day to talk about what changed into crucial to the lives and livelihoods.

Avenue B become known as the German Broadway, in which nearly each building contained a primary floor store, or a workshop, advertising each type of commodity that was favored with the aid of the German populace. Avenue A became understand for its beer gardens, oyster saloons and various grocery stores. In Little Germany there have been also wearing clubs, libraries, choirs, shooting clubs, factories, department stores, German theaters, German faculties, German church buildings, and German synagogues for the German Jews.

Starting round 1880, the wealthier Germans started out transferring out of New York City to the suburbs. And via the turn of the 20 Th Century, the German populace in Little Germany had shrunk to round 50,000 people, nonetheless a considerable amount for any ethnic community in New York City.

On June 15, 1904, St. Mark's Evangelical Lutheran Church on 6th Street charted the paddle boat General Slocum, for the sum of $350, to take members of its congregation to its yearly picnic, celebrating the quit of the faculty yr. At a couple of minutes after nine a.M., more than 1300 humans boarded the General Slocum. Their vacation spot changed into the Locust Grove on Long Island Sound, in which they expected to revel in an afternoon of swimming, video games, and the first-class of German meals.

The General Slocum, owned by means of the Knickerbocker Steamship Company, become named for Civil War officer and New York Congressman Henry Warner Slocum. It changed into built through W. & A. Fletcher Company of Hoboken, New Jersey, and become a sidewheel paddle boat powered via a unmarried-cylinder, floor condensing vertical beam steam engine with fifty three inch bore and 12 foot stroke. Each wheel had 26 paddles and turned into 31 feet in diameter. Her maximum speed was about 16 knots.

Almost from the day of its launching in 1891, the General Slocum suffered one mishap after every other. Four months after her launching, the General Slocum ran aground near the Walkaways. Several tugboats had been wanted to pull the General Slocum back into the water.

1894 turned into a very bad year for the General Slocum. On June twenty ninth, the General Slocum turned into returning from the Walkaways with 4700 passengers on board. Suddenly, it struck a sandbar so hard, that her electric generator blew out. In August, at some point of a horrible rain hurricane, the General Slocum ran aground a 2nd time, this time close to Corey Island. The passengers needed to be transferred to any other deliver so that you can make their way lower back home. The subsequent month the General Slocum hit the trifecta when it collided with the tug boat R. T. Sabre in the midst of the East River. In this incident, the General Slocum's steerage turned into critically broken, and it had to be repaired. The General Slocum became accident loose until July of 1898, whilst the General Slocum collided with the Amelia near Battery Park.

On August 17, 1901, The General Slocum changed into wearing, what changed into described as "900 intoxicated Patterson Anarchists." Suddenly, some of the passengers began to insurrection. Others attempted to bodily take manage of the boat, by means of storming the bridge. However the team fought the rioters off and were capable of keep manage of the boat. When the captain docked at the police pier, 17 "anarchists" were arrested.

Finally, in June of 1902, the General Slocum ran aground again. The boat become not able to be freed, so its passengers needed to camp out the complete night till reinforcements should arrive the subsequent morning. The captain of the boat in that incident changed into none aside from Captain William H. Van Schick, the equal man who would be the leader officer of the General Slocum on its ultimate voyage.

On June 15, 1904, approximately 15 mins after the General Slocum left the pier at East Third Street, it became even with East one hundred and twenty fifth Street. At this factor, Captain Van Schick become notified by certainly one of his crew that a fire had commenced within the Lamp Room, inside the forward phase of the boat. The fireplace become likely ignited through a discarded cigarette or a healthy, and it turned into obviously fueled with the aid of the straw, oily rags, and lamp oil strewn across the room. The Captain had been informed there has been a hearth on board a few minutes earlier by using a 12-year-old boy, but Captain Van Schick did no longer accept as true with the boy. Other humans on board stated the fire had commenced almost simultaneously in numerous locations, which include a paint locker packed with flammable fluids, and a cabin full of gas.

This is where Captain Van Schick made a terrible mistake in judgment. Since land changed into close by, all the Captain needed to do was run his deliver aground before the flames unfold any in addition. Then he may want to sell off his passengers, normally lady and kids, fast earlier than there have been any fatalities. But for a few motive Captain Van Schick decided to go directly right into a headwind and try to land his boat at North Brother Island, simply off the southern shore of the Bronx. Captain Van Chadwick could later say the cause for his choice became that he became looking to prevent the fire from spreading on land to riverside buildings and oil tanks. But by going into heavy headwinds, he turned into certainly fanning the fire.

Captain Van Schick later stated at his trial, "I started out to head for One Hundred and Thirty-fourth Street, but turned into warned off with the aid of the captain of a tugboat, who shouted to me that the boat might set fire to the lumber yards and oil tanks there. Besides, I knew that the shore turned into coated with rocks and the boat would founder if I put in there. I then constant upon North Brother Island."

As the boat chugged onward, passengers ran in panic across the deck. Mothers have been looking for their youngsters. Father's were searching out their households. Young boys and women scrambled onto the deck chairs, waving frantically for assist on the crowds who had assembled on the shore. The flames expanded by means of the second, expanded by the boat's clean coat of highly flammable paint.

At this factor, overcome through smoke inhalation, and with the flames flickering at their torsos, toes and faces, human beings started leaping into the water. Some were rescued by using boats which had rushed close to the fiery General Slocum. But maximum of the girl and girls, due to the cumbersome female's apparel of that technology, fast drowned. Some humans died when the floors of the boat collapsed. Others have been overwhelmed to loss of life via the nonetheless churning paddles, as they flung themselves over the edges of the boat closer to the water.

People that attempted to apply the existence jackets on board were in for a horrible marvel. Although there had been 3000 lifestyles jackets to be had, they had been all but useless. The enormous majority were rotted out, with the cork within the jackets used for buoyancy almost totally disintegrated. The people who did don the existence jacked and plunged into the water, right away sank like a rock. Some people tried to dislodge the emergency lifeboats, but they failed to accomplish that because the lifeboats have been firmly stressed out in vicinity.

People from the shore noticed a girl in a blue dress leap off the aspect of the boat. They watched in horror because the female hit the wooded paddle wheel. The wheel churned violently, dragging the woman below it. The humans on shore may want to pay attention the screaming lady's frail body being threshed about like a rag doll by using the paddle wheel, before her screaming stopped and she disappeared into the murky waters. A little boy, clutching his filled toy dog, turned into thrown into the river by his weeping mom. The boy changed into fished from the river alive, still squeezing his precious toy dog.

16-year-vintage Albert Frees became one of the fortunate ones who survived the General Slocum catastrophe. Frees, at the time, become a mail clerk inside the Funk and Wagtails publishing house. As horrified human beings scampered all around him, Frees moved quickly to the strict of the burning boat. According to Edward Ross Ellis' The Epic of New York City, "Frees jumped ft first, with his ankles collectively and his hands inflexible at his side. He become able to swim correctly to shore, and later became treasurer of his firm."

As Captain Van Schick resolutely and pigheadedly prompt his boat onward, people on Manhattan's Japanese shore had been now going for walks frantically along the riverbank, trying to maintain tempo with the burning boat. Others have been mobilized in wagons and carts, screaming for the Captain to run his boat ashore. Some humans flung barrels into the river for the people floundering within the water to use as makeshift existence preservers. Small boats tried to chase down the General Slocum from in the back of, however they had been unable to do so. However, a number of these boats had been capable of fish the better swimmers out of the water and produce them accurately to shore.

Despite the utter mayhem, and the pleading of the humans at the shore to run his boat aground, Captain Van Schick, his own clothes on hearth, disregarded them and continued in the direction of North Brother Island. When Captain Van Schick finally beached his boat at North Brother Island, the boat become one huge fireball.

Captain Van Schick said later, "I stuck to my publish in the pilothouse till my cap caught fireplace. We were then about twenty-five toes off North Brother Island. She went at the beach, bow on, in about twenty-five toes of water.... Most of the humans aft, wherein the hearth raged fiercest, jumped in while we had been in deep water, and have been over excited. We had no hazard to decrease the lifeboats. They had been burned earlier than the team should get at them."

At North Brother Island, nurses, docs, and even the patients within the island's contagious ailment sanatorium, rushed to assist the survivors. Some carried ladders, which they used to manual the survivors, most badly burned, down from the boat. Others caught little kids who have been heaved all the way down to them by using hysterical dad and mom. Within mins, all the survivors, together with the captain and several team individuals, where taken accurately away from the flaming boat and admitted to the sanatorium.

From his medical institution window, a feverish measles patient saw the horror transpiring. He summoned the braveness, moved quickly from the sanatorium and sprinted into the water. He turned into able to keep several children. A nurse who could not swim dashed into the river to seize numerous kids. She did this repeatedly, while abruptly the tide pulled her into deeper water. Incredibly, the nurse observed out she ought to certainly swim, and she or he endured rescuing whomever she could attain.

City Health Commissioner Darling ton became present on North Brother Island the day the fiery General Slocum ran aground. "I will by no means be able to forget about the scene, the utter horror of it," Darling ton stated. "The patients inside the contagious wards, specially inside the scarlet fever ward, went wild at matters they saw from their home windows and went screaming and beating at the doors until it took fifty nurses and medical doctors to quiet them. They were all locked up. Along the beach the boats have been sporting within the living and death and towing within the dead."

When the fireplace first started out, a person rang the metropolis table of the World on Park Row. The guy, who did not identify himself, advised the newspaper editor that he changed into in his workplace at 137th Street and he should see the burning boat from his office window. The editor straight away contacted Eugene Moran, who owned a tugboat organization at 134th Street. Moran told the editor that he had no tugboats available in that area, but that it would be faster anyway to send his men through expanded educate from the Park Row station to the Morris Park station within the north Bronx. The editor ordered his men onto the teach, and as a end result, the World had the tale of the tragedy earlier than some other New York City newspaper.

When the World reporters arrived on the scene, they have been triumph over with grief. As the boat was enveloped in smoke and flames, the journalists and the World's photographers noticed dozens of blackened and bloody useless bodies scattered along the shore line. As the photographers snapped away and the reporters jotted down their notes, numerous hardened newspapermen broke down in tears. Then they rushed to find phones in order that they may deliver their stories to the rewrite guys at their newspaper. Their description of the tragedy on the telephones were so graphic, while the rewrite men heard what had transpired, they rushed into the guys's room to vomit.

The New York Times suggested day after today, "On the night of June 15, 1904, grief-crazed crowds covered the shore in which the bodies were being brought in via the boatload. Scores had been averted from throwing themselves into the river."

The police released a file some days later claiming that 1,031 humans had perished within the General Slocum fireplace. For the following couple of weeks, police divers searched for bodies in the partly sunk stays of the General Slocum. Police and rescue parties scoured the banks of the river for miles in each guidelines searching out bodies.

On the night time of the fire, ratings of husbands got here home from work only to find out that their entire households had perished in the hearth. Some devoted suicide, others went mad, and a few later died of grief. For 3 days, hearses transverses the streets of Little Germany wearing our bodies, and parts of bodies, to their graves in Lutheran Cemetery in Middle Village, Queens.

A Federal grand jury indicted 8 human beings as a result of the catastrophe. Those humans blanketed Captain Van Schick, boat inspectors, and the president, secretary, treasurer, and commodore of the Knickerbocker Steamship Company. However, most effective Captain Van Schick turned into convicted at trial. The prices the Captain became convicted on were criminal negligence, failing to hold right fireplace drills and fireplace extinguishers. There changed into a hung jury on the manslaughter charge. Captain Van Schick turned into sentenced to ten years in jail. The Captain served 3 and a 1/2 years at Sing Sing Prison earlier than he acquired parole. On August 26, 1911, the administration of President William Howard Taft voted to release Captain Van Schick from parole. And on December 19, 1912, President Taft pardoned the Captain. Captain Van Schick died in 1927.

The Knickerbocker Steamship Company acquired a ridiculously small excellent, despite the fact that there was sufficient proof that they'd falsified inspection statistics. The sunken stays of the General Slocum had been raised to the floor, and ultimately converted into a barge, which predictably sank throughout a hurricane in 1911.

The tragedy of the General Slocum pressured a major reconstruction of steamboat protection policies. A week after the fireplace, President Theodore Roosevelt order a five-man fee to analyze why the tragedy had befell, and what could be finished to prevent it from taking place again in the destiny. The commission became especially hard on the United States Steamboat Inspection Service (US SIS), who had failed depressing at their activity of making sure steamboat protection. Dozens of US SIS employees had been fired, and new inspections of all steamboats ordered. Predictably, severs violations were observed, strolling from useless existence jackets to rotted fireplace hoses.

The five-guy committee recommended many reforms which include: fireproof steel bulkheads to comprise fires, steam pipes extended from the boiler into shipment regions (to act as a sprinkler), progressed life jackets (one for each passenger and team member), hearth hoses capable of managing a hundred kilos of strain according to rectangular inch, and handy lifestyles boats. All these reforms were instituted, which dramatically stepped forward steamboat safety.

The General Slocum fireplace all but erased the German populace from the decrease east facet of Manhattan. Soon after the tragedy, hundreds of families moved from the lower east facet because memories of the tragedy have been too terrible to endure. Some settled at the upper east facet of Manhattan's Orville section, growing a new German town. Some moved to Astoria in Queens, and others left New York City absolutely.

Strangle, the memory of General Slocum fire, even though it killed nearly 10 instances as many humans as did the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire of 1911, quick faded from most of the people's attention. A large part of the cause was that the onset of World War One removed all sympathies for every person of German descent, and all of the sufferers of the General Slocum hearth had been German.

In 1905, the Sympathy Society of German Ladies commissioned sculptor Bruno Louis Zimmerman to design a memorial fountain, which was unveiled on May 30, 1905 on the northwestern corner of Tompkins Square Park. This white nine-foot fountain is sculpted of purple Tennessee marble. On the front, above the carved lion's head spout and basin, a there is an outline of harmless youngsters staring off towards the sea, with the inscription, "They were earth's purest kids, loving and honest."

This memorial fountain [ https://anonymster.com/ ] still stands in Tompkins Square Park to this very day.

0 notes

Link

The US military has begun kicking out immigrants for whom service offered a pathway to citizenship. According to a recent report from the Associated Press, dozens of enlistees — part of a program called MAVNI (Military Accessions Vital to the National Interest) — have already been discharged. That’s in addition to hundreds of recruits who had their contracts abruptly canceled last fall.

MAVNI, a program started in 2008, opened the door for immigrants who were in the country legally (including DACA recipients) to enroll in the military and, in reward for their service, have their citizenship fast-tracked.

Though the exact scope of the dismissals is unclear — the Pentagon has not supplied a number, and some enlistees say they’ve been told only that they failed an unspecified background check — the tightening restrictions on immigrants in the military (which goes well beyond this latest report) fits perfectly with the administration’s anti-immigrant and nativist policies.

Historically, for immigrants excluded from the full rights of citizenship because of their race, the military has been the most powerful proving ground for their citizenship claims. From Asian Americans who won citizenship after serving in Europe in World War I to African Americans who won support for civil rights after returning from World War II, military service created an almost irrefutable case for citizenship.

American racists sometimes still fought those claims, but they led to real advances — which is exactly why the Trump administration would aim to end such a program.

Perhaps the most striking case of military citizenship featured Asian immigrants in the early 20th century. This was a time when immigration from most parts of the world went largely unrestricted, but Asian immigrants faced profound barriers. Chinese immigration had been halted in 1882, through the Chinese Exclusion Act, and that ban expanded to include Japan in 1907 and most of the rest of Asia in 1917.

Not only had immigration been shut off, but so had naturalization. The 14th Amendment and 1870 Naturalization Act created a black-and-white definition of citizenship. As always, white people could become citizens. But now, so could “people of African descent,” most notably, former slaves, who had been categorically denied citizenship by the 1857 Dred Scott decision.

For everyone who fell outside those categories, including Asian, Mexican, and some Middle Eastern immigrants, the question of citizenship was unclear. They were clearly not of African descent, but were they white? A series of lawsuits pressed the question, forcing judges to pin down a definition of whiteness that excluded Chinese, Japanese, and Asian Indian immigrants. As a result, while their children would become citizens thanks to the principle of birthright citizenship, immigrants of Asian descent could not become naturalized citizens of the United States.

This did not, however, prevent Asian immigrants from serving in the US military and fighting for citizenship in return for their service. Since 1862, the US government had recognized the value of immigrant military service, and offered expedited naturalization to “any alien” who had lived in the US for at least a year and fought for the US army.

The mass mobilization that accompanied US entrance into WWI brought hundreds of thousands of noncitizen immigrants into the armed forces (the Selective Service Act required any male immigrants who intended to become citizens to register for the draft), and between 1918 and 1920, nearly a quarter-million of those soldiers were naturalized, many even before shipping off to the front.

Throughout the war, the government repeatedly made the case that military service was the crucible of citizenship, the testing ground that allowed immigrants to prove their loyalty, their bravery, and their fitness as Americans. One captain surveying the intake of new immigrant soldiers cheered that “out of the melting pot of America’s admixture of races is being poured a new American trained and ready to make the world safe for Democracy.” The War Department even included civics courses as part of wartime training to “Americanize” immigrants in the service.

Henry Breckinridge, the assistant secretary of war, saw this as a great contribution of military service. The soldier, “no matter from what race stock he comes — Teuton, Slav, Czech, Italian, Celt or Anglo-Saxon — all rubbing elbows in a common service to a common Fatherland — out comes the hyphen — up goes the Stars and Stripes and in a generation the melting pot will have melted.”

Note that Breckinridge did not include Asian immigrants in his list of nationalities, but those immigrants nonetheless heard the promise of soldier-citizenship and quickly moved to translate their work in the war into naturalization.

Yet had it not been for a sympathetic judge and federal agent, their efforts would have been wasted.

The initial position of the Bureau of Naturalization was that Asian immigrants remained ineligible for citizenship, being neither white nor black. But in December 1918, federal district court judge Horace W. Vaughan announced — to the surprise of the Bureau of Naturalization — that he would naturalize Chinese, Korean, and Japanese soldiers. “We had drafted them into our service,” he explained, “and they thought enough of us to be willing to serve, to risk their lives in our service.” He found an accomplice in the deputy commissioner of naturalization, Raymond Crist.

As historian Lucy E. Salyer has shown, the two worked to naturalize hundreds of Asian soldiers. They continued, fruitlessly, to issue naturalization papers to Asian soldiers even after the Supreme Court ruled in 1925 that any veteran ineligible for citizenship by “color or race” remained ineligible, regardless of service. Crist argued anyone with naturalization papers was a citizen, regardless of the court’s stance, but his view did not have the force of law.

But a rogue federal agent can’t save an entire group from the judiciary in perpetuity, and despite Crist’s efforts, this category of immigrant was denied citizenship under the law. What Asian veterans needed was an act of Congress that would permit them to gain their citizenship — which they got, thanks to the work of veteran Tokutaro Slocum.

Slocum, who was born in Japan and moved to America at the age of 10, was studying law at Columbia when the US entered WWI. He left school, fought in France, attained the rank of sergeant major, and was rewarded with naturalization, which he lost after the Supreme Court ruling in 1925. As a member of the Japanese American Citizenship League, he lobbied Congress for the restoration of his citizenship, along with that of all other WWI veterans in his situation.

Vaughan, Crist, and Slocum were all appealing to the idea of service over race in an era in which citizenship was strongly tied to whiteness and when anti-immigrant sentiment ran high. Indeed, in the midst of the fight over the naturalization of Asian-American veterans, the US imposed strict racist quotas on immigration — in its infamous law of 1924 —and the Ku Klux Klan flourished under a program of “100 percent Americanism.”

Notably, the 1935 Nye-Lea Act that granted Slocum and other veterans citizenship opened no pathway to other Asian immigrants; it was for veterans alone. Nor did it save Slocum from other racist laws. In 1942, when the US began rounding up Japanese immigrants and Japanese-Americans, Slocum and his family were sent to Manzanar internment camp, in California’s Owens Valley.

Slocum’s fate reminds us of the limits of martial citizenship: If some people, because of their race or ethnicity, are forced to show exemplary bravery and sacrifice in order to prove their fitness for citizenship, something has already gone wrong. Yet the idea that military service can be a way for immigrants to earn rights has historically been potent enough to win over even cultural conservatives.

It should therefore come as no surprise that the Trump administration would like to shut that door, as part of its broader effort to demonize migrants and restrict immigration. Since 2001, more than 100,000 immigrants have become naturalized citizens through military service (10,400 through Military Accessions Vital to the National Interest).

Slocum’s story should remind us that even as the nation’s laws and opportunities constrict — for racist reasons — activists, government workers, and judges can help pry back them back open.

Nicole Hemmer, a Vox columnist, is the author of Messengers of the Right: Conservative Media and the Transformation of American Politics. She is an assistant professor at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center and co-host of the Past Present podcast.

The Big Idea is Vox’s home for smart discussion of the most important issues and ideas in politics, science, and culture — typically by outside contributors. If you have an idea for a piece, pitch us at [email protected].

Original Source -> It’s always been hard to say no to citizenship requests from soldiers

via The Conservative Brief

0 notes

Photo

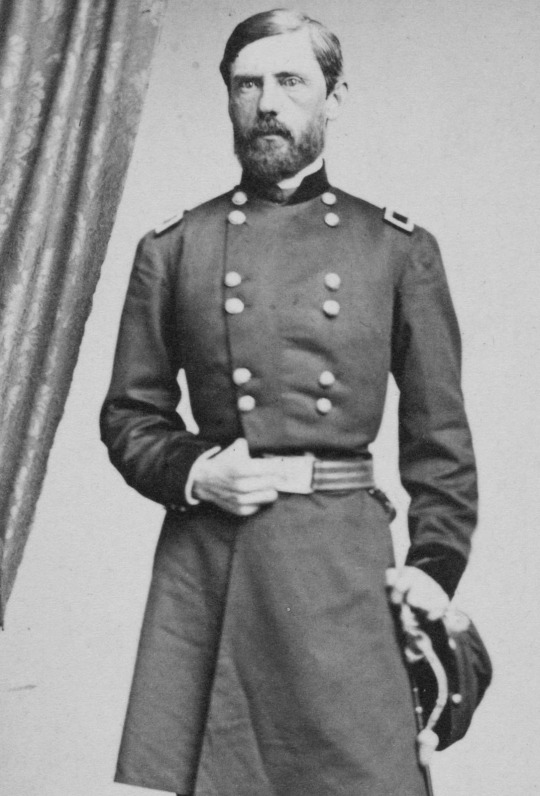

Brevet Major General Joseph Jackson Bartlett (USA)

Joseph Jackson Bartlett was born in Binghamton, New York on 21 November 1834. He studied law in Utica and passed the bar in 1858, establishing a law practice in Binghamton and then Elmira.

On 21 May 1861, Bartlett enlisted in 27th New York Infantry and was elected the captain of a company but was soon promoted to major, serving under Colonel Henry W. Slocum. After only a few weeks of training, Bartlett saw his first combat at the First Battle of Bull Run. When Slocum was briefly incapacitated by a wound, Bartlett assumed commanded of the 27th New York. His aggressive actions to guard the rear during the retreat were rewarded when he was promoted to colonel to replace Slocum who was elevated to brigadier general.

In 1862, as part of the Army of the Potomac's VI Corps, Bartlett led his regiment throughout the Peninsula Campaign and Maryland Campaign. He led an attack up the steep mountainside towards Crampton's Gap during the Battle of South Mountain. On 4 October 1862, he was promoted to brigadier general and commanded a brigade in the VI Corps at the Battle of Fredericksburg.

Bartlett's next significant action came in May 1863 at the Battle of Salem Church, where he lost more than a third of his 1,500 men, yet managed to keep order. His men were primarily in reserve at the Battle of Gettysburg. Bartlett was transferred to V Corps in time for the Mine Run Campaign later that year, and led its first division in the absence of Brig. Gen. Charles Griffin. Resuming command of a brigade in that division, Bartlett was active in the Overland Campaign and the Siege of Petersburg.

During the final year of the war, he led a division during the Appomattox Campaign. When Philip Sheridan removed Maj. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren from corps command after the Battle of Five Forks, Griffin became corps commander and Bartlett became division commander. Following the war, he was awarded a brevet promotion to major general and briefly commanded a division of the IX Corps.

He remained in the army on occupation duty in the South during the early days of Reconstruction. He resigned his commission on 15 January 1866 and returned to his New York law practice. In 1867, President Andrew Johnson appointed him as United States Ambassador to Sweden and Norway. He served for two years, and then returned home in 1869. He resumed his legal career, which was briefly interrupted from March 1885 to July 1889, when he served as Deputy Commissioner of Pensions under President Grover Cleveland.

He suffered for much of his life with rheumatism caused by exposure during the war. Bartlett died in Baltimore, Maryland on 14 January 1893.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Gettysburg National Military Park (No. 41)

Southeast of Gettysburg the high ground of Culp’s Hill and Cemetery Hill is connected by a low ridge dominated by a little knoll. Originally known as McKnight’s Hill, since the battle this high ground has been known as Stevens Knoll, after Captain Greenleaf Stevens, the commander of the 5th Maine Battery (Battery E, Maine Light Artillery) that occupied it and fought off Confederate General Jubal Early’s assault on the evening of July 2nd.

Few other monuments share the ridge, and traffic finishing its circuit of Culp’s Hill (both Slocum Avenue and WIlliams Avenue are one way to the west) rarely stops, making this area a bit of an oasis between often-crowded Culp’s and Cemetery Hills.

Source

The monument to Major General Henry Slocum is south of Gettysburg on Slocum Avenue. It was dedicated on September 19, 1902 by the State of New York.

The monument is a bronze equestrian statue created by sculptor Edward Clark Potter. Potter made a number of equestrian statues but is best known for the lions in front of the New York Public Library. Slocum’s statue weighs 7,300 pounds and stands 15′ 6″ tall. It rests on a 16′ tall base of Barre granite designed by A.J. Zabriskie. Large bronze inscribed tablets are inset into the base on each side.

Source

#Gettysburg National Military Park#Stevens Knoll Area#Pennsylvania#USA#travel#summer 2019#original photography#landscape#countryside#vacation#American Civil War#US Civil War#Major-General Henry Slocum#Edward Clark Potter#Stevens' Battery 5th Maine Artillery Monument#cannon#flora#nature#tourist attraction#landmark#US history

5 notes

·

View notes