#Limnofregata

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

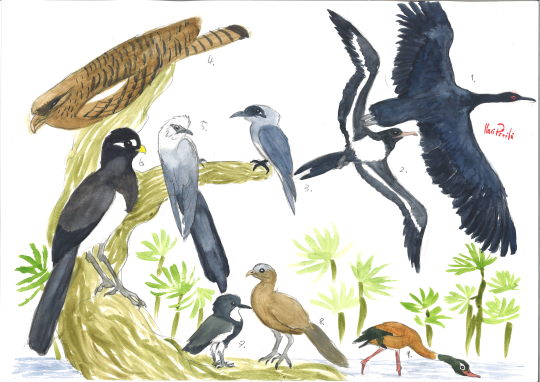

Fossil Novembirb: Day 10 - Bayou in the Badlands

The modern landscape of the American west is but a far cry from its past. Early Eocene Green River formation preserves an incredible snapshot of time 50 million years ago. The locality of these fossils was once a huge lake system bordered by forests of sycamore and palmettos, and teeming with animals of all kinds, including birds, which were in the middle of an enormous radiation of forms.

Calciavis: A palaeognath which was a member of the lithornithids. Like them, it fed on insects from the forest floor and was a powerful flier. Some fossils preserve colour pigments of its feathers, suggesting this bird was a glossy black.

Limnofregata: The earliest known frigatebird that flew over the water just as its aeronaut descendants. Like modern frigates, it plucked prey from the water and the shorelines of the lake system.

Plesiocathartes: A bizarre bird that has had a complicated history. Now we know that it was an early relative of the cuckoo-roller from Madagascar and probably lived a similar lifestyle.

Celericolius: An early member of the mousebird family that had long wings and even longer tail. It may have flown at high speed through the forests.

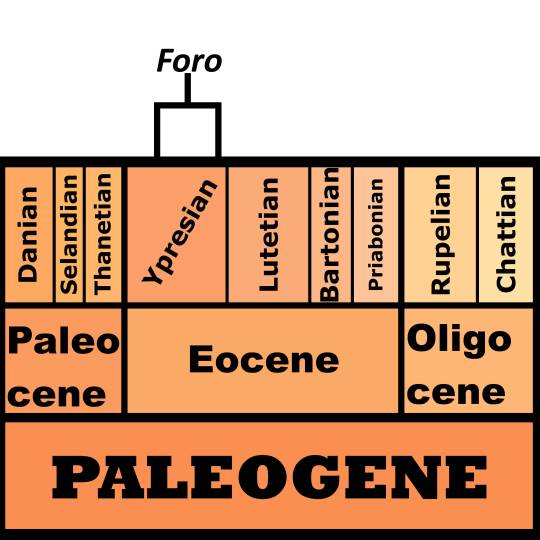

Foro: This american bird is in fact an early member of turacos, birds which are unique to Africa today. Like them, it mostly fed on soft fruit.

Prefica: A strange bird who'se closest living relative is the oilbird of South America, which is a nocturnal frugivore. It could be that this ancient relative lived in a similar way.

Nahmavis: An early member of the shorebird family known from a spectacular fossil that preserves feathers.

Gallinuloides: The earliest known true galliform, this small fowl was among the early ancestors of guans, quails, turkeys and grouse.

Presbyornis: A widespread wading waterfowl related to ducks and geese. Sometimes called the flamingo-duck, it used its flat bill to filter its food, and may have nested in colonies like flamingos.

#Fossil Novembirb#Novembirb#Dinovember#birblr#palaeoblr#Birds#Dinosaurs#Cenozoic Birds#Calciavis#Limnofregata#Plesiocathartes#Celericolius#Foro#Prefica#Nahmavis#Gallinuloides#Presbyornis

48 notes

·

View notes

Note

trick or treat! :D

Limnofregata!

32 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Being me, I naturally decided to modify that 50 characters meme into a “50 interesting dinosaurs” meme. Hats off to you if you can identify more than half from these tiny pixelated images. (Hint: 14 of them are Cenozoic dinosaurs.) Blank version here for anyone else who wants to fill it out.

(Answers below the break.)

Buriolestes

Chilesaurus

Hesperornis

Iteravis

Prenocephale

Kelenken

Kosmoceratops

Aptornis

Concavenator

Limnofregata

Halszkaraptor

Cruralispennia

Falcarius

Microraptor

Haplocheirus

Similicaudipteryx

Foro

Conflicto

Sapeornis

Protodontopteryx

Albertonykus

Limusaurus

Kulindadromeus

Yi

Celericolius

Yutyrannus

Balaur

Xenicibis

Mei

Eofringillirostrum

Anchiornis

Bannykus

Raphus

Borealopelta

Miragaia

Archaeopteryx

Oryctodromeus

Caihong

Eocoracias

Parasaurolophus

Gigantoraptor

Fluvioviridavis

Inkayacu

Mengciusornis

Deinocheirus

Sinocalliopteryx

Eocypselus

Nigersaurus

Shanweiniao

Tianyulong

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

17? i have an obsession over this number lol

lol did you know in Judaism (I am Jewish) the number 18 in numerology means "life"? So we tend to do things in multiples of 18. To the point that doing things in multiples of 17 makes me twitch XD XD XD XD like why if you do one more it's life!!!! l'chaim!!!!

anyways here are 17 dinosaurs

Lesothosaurus

Miragaia

Euoplocephalus

Zalmoxes

Tsintaosaurus

Centrosaurus

Lessemsaurus

Brachytrachelopan

Bonitasaura

Cryolophosaurus

Guanlong

Incisivosaurus

Jeholornis

Dinornis robustus

Southern Screamer

Limnofregata

European Robin

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fossil Novembirb 10: Bayou in the Badlands

Fluvioviridavis by @quetzalpali-art

Back to Eocene Ecosystems! One of the most famous Eocene fossil sites in the world is the Fossil Lake site of the Green River Formation, an ecosystem from Colorado in the United States. This ecosystem records the transition from the moist forested world of the early Eocene to the drier warm world of the mid-Eocene. The forests would begin to shrink back, the foliage would change, and so would the animals.

Fossil Lake records the start of that process! Sediment would regularly settle into this lake at periodic intervals, which then recorded the evolution of the lifeforms there over thousands of years. The forests were filled with sycamore trees and other broadleaf plants, as well as ferns.

Limnofregata by @iguanodont

Because the lake was so frequently filled with sediment, oxygen levels were low to nonexistent, preventing decomposers from living at the bottom of the lake. This lead to many different organisms being preserved nearly perfectly, including many gorgeous birds!

In fact, the Field Museum of Chicago - my home - has many of these wonderful fossils on display, and have fascinated me since childhood. So I'm going to break format a little here to showcase some of these fossils.

Cyrilavis, a Halcyornithid (Parrot-Passerine of Prey)

Fluvioviridavis, a Strisorian (like oilbirds or frogmouths)

Eofringillirostrum, a Passerine

Limnofregata, a Frigatebird in a Gull Niche

Nahmavis, a relative of shorebirds (Charadriiformes) or rails and cranes (Gruiformes)

An unnamed Anseriform, probably similar to Anachronornis

Celericolius, a mousebird

Zygodactylus, a stem-passerine

We see once again in this ecosystem - as we have in the others we've covered - the common theme of Avian evolution: the niches may stay the same, but the birds filling them will always change. We have Mousebirds perching in trees in North America, we have Frigatebirds filling the Gull niche, ducks wading around the lake like flamingos, and cousins of parrots/passerines hunting prey.

Presbyornis by @drawingwithdinosaurs

Other notable dinosaurs from this formation include Presbyornis, another one of those Flamingo-Ducks we've talked about like Teviornis and Conflicto; Gastornis because it was literally everywhere from the latest Paleocene through the early Eocene; Lithornithids like Pseudocrypturus because they were also everywhere; early landfowl like Gallinuloides; the cuckoo-roller Plesiocathartes; the ibis Vadaravis; and the turaco relative Foro. Once again, we see many tropical birds in places where they aren't today, due to the extensive warm climate of the Early Eocene.

Foro by @drawingwithdinosaurs

This swampy ecosystem was filled with large crocodile relatives, small mammals, the earliest known bats, giant lizards, and an alarming number of fish - making it one of the better known ecosystems of the early Paleogene. But the best known Paleogene fossil location is still to come...

Sources:

Grande, L. 2013. The Lost World of Fossil Lake: Snapshots from Deep Time. University of Chicago Press.

Mayr, 2022. Paleogene Fossil Birds, 2nd Edition. Springer Cham.

Mayr, 2017. Avian Evolution: The Fossil Record of Birds and its Paleobiological Significance (TOPA Topics in Paleobiology). Wiley Blackwell.

106 notes

·

View notes

Text

Oh man. That's a big question. There are simply too many Avialan Dinosaurs that don't get enough attention.

I know you specifically asked for Cenozoic, but I'm also going to take the time to highlight some great Mesozoic Avialans, because they also never get any attention

Mesozoic Avialans Worthy of Attention:

I know they bounce back and forth a lot because there isn't actually a dividing line between "dinosaur" and "bird", but I have to mention the Anchiornithids - Things like Caihong, Serikornis, and of course Anchiornis itself are really cool fluffy friends that really showcase the variety of feather adaptations

Jeholornis is amazing, we know so much about it and its ecology! It ate seeds, it had a rad tail, it just is aesthetically pleasing

I love Sapeornis because it was essentially the first "bird of prey" if we don't count Microraptor (which admittedly we could)

Confuciusornis is possibly one of the best known Mesozoic dinosaurs of all time. Where the hell is it. Why isn't it in literally anything. Amber Isle even has the tail of Confuciusornis as an option for your character, but gd forbid having an NPC be one I guess

Enantiornithines. There are so many of them. It's kind of insane. Like, these non-Neornithine dinosaurs were essentially *the* birds of the Cretaceous period. I can't even cover all the ones that deserve attention, not fairly anyway. Off the top of my head - Shanweiniao is a great one, as is Bohaiornis, and Gobipteryx, and Avimaia is a wonderful specimen, and Avisaurus is a big hit for Hell Creek fans, and Falcatakely is literally the Tooth-can, and Imparavis was toothless and that's cool, and Lectavis was very like modern shorebirds, and Parvavis is the smallest known Mesozoic dinosaur, and Chiappeavis had a cool tail fan, and I should really stop before this gets too long

On the line to modern birds, Patagopteryx is an early example of a bird that re-evolved flightlessness! I mean yeah things like Utahraptor are too but shush

Yanornis is just such a cool transitional species

Gansus is actually well known for a reason - it was aquatic!

Can you really go wrong with Apsaravis?

Literally the entirety of Hesperonithines

Ichthyornis is just Platinum Tier

And then we have the earliest "modern birds", which are Mesozoic! We've got Vegavis (probably) and Asteriornis! Showcasing how even in the Cretaceous, we had Chickens (ish) and Ducks (ish)

Cenozoic Avians Worthy Of Attention:

Gastornis. Gastornis. Gastornis. Gastornis.

PELAGORNITHIDS. these weirdos responded to the problem of "birds can't reevolve teeth" with "LETS JUST MAKE OUR BEAKS LOOK RIDICULOUS" and they were successful throughout the Cenozoic and just died out bc of the ice age and thats the only reason we don't have any?????? and NOTHING USES THEM??? besides ark which is a travesty

There's a whole score of interesting birds that are in the Passerine-Parrot group but not proper Passerines or Parrots that I've dubbed "Pass-Parrots of Prey" (formerly Parrots of Prey) because they're all raptorial! parrots and passerines come from raptor ancestors!

apparently frigatebirds did the Gull thing before they were frigatebirds and before gulls existed and that's Limnofregata

PENGUINS. They show up RIGHT after the end-cretaceous and have a detailed Paleocene fossil record (a rarity, I assure you) - so we have a great transitional sequence and then on top of it some are HUGE

I deeply love presbyornithids

Sandcoleids are little weirdos I love them

LITHORNITHIDS. They are the base from which Paleognaths evolved and they were flying friends!

Terror Birds. They show up early in the Cenozoic and only died out at the end of the Ice Age. they were a HUGE component of South America's ecosystems and were extremely successful. Also, badass.

Bathornis is basically the North American terror bird (ignore Titanis) so that too

qianshanornis is a cutie with a sickle claw

PLOTOPTERIDS! some booby relatives were like "we want to be penguins" and then they did it! in the northern hemisphere! they were all over the Pacific!

Dromornithids (Mihirungs) are super cool Australian megafowl

I'm a little biased, but I think the screamer-duck I helped described (Anachronornis) is pretty cool

I love Palaelodids (Swimming Flamingos) because they just look Weeeeeeird

I have a soft spot for Zygodactylids because they're basically the usual passerine body but with parrot feet. that's rad

Teratorns were cool vulture-relatives that got REALLY big

There are a handful of terrestrial raptors related to falcons that were notable in the Eocene like Danielsraptor

I deeply appreciate Moa and Elephant Birds for being big friends

Haast's Eagle is one of those things you shouldn't think about too hard

GIANT SWAN OF SICILY

Xenicibis and your club-wings my beloved

Heracles was a Giant fucking Kakapo/Kea/Kaka type parrot and it was RIDICULOUS

I'm ignoring a lot of transitional birds - early members of different groups that tried out unique niches or ecologies that their modern relatives don't do - because if I listed them all this post would get ridiculous. just trust there's tons of interesting small birds that require more text to show how they're interesting than I feel like writing at 5am

STILT OWLS

Sylviornis was another excellent Megafowl

z''l dodos and great auks

Talpanas, aka, the Reverse-Platypus

just for a start

*grabs you by the front of your shirt* Birds throughout the Cenozoic, including today, have significantly more in common with every other dinosaur than any dinosaur has to things like Dimetrodon or Mosasaurus or even Pteranodon. Dinosaurs are a specific family group and birds are extremely nested within it. Including prehistoric creatures in your media but specifically leaving out Cenozoic Dinosaurs is not only a disservice to dinosaurs, but to whatever thing you're creating and also prehistoric life in general. For the love of Gd, just add Gastornis or a Terror Bird or a Pelagornithid to your damn video game/cartoon/comic strip. Dinosaurs don't just *stop* at Archaeopteryx and I am literally losing my mind at this point, please, for me, just do it

(I love @paleopinesofficial and Amber Isle from @ambertailgames, I do, but the fact that there's Dimetrodons and Postosuchus-es and Thylacines and no dinosaurs closer to birds than Archaeopteryx is so infuriating I'm on the verge of tears)

sincerely

a paleontologist who studies cenozoic birds

889 notes

·

View notes

Text

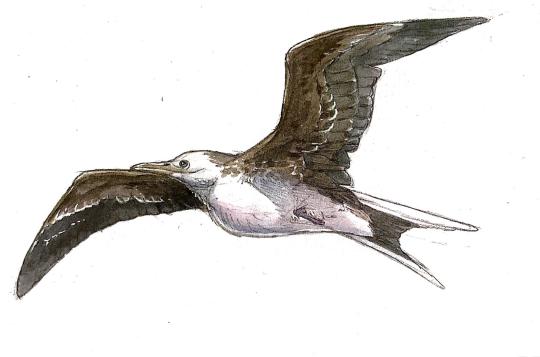

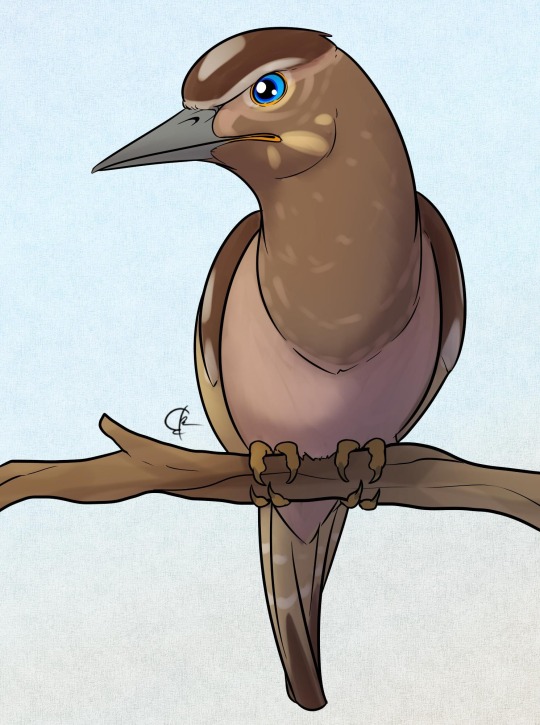

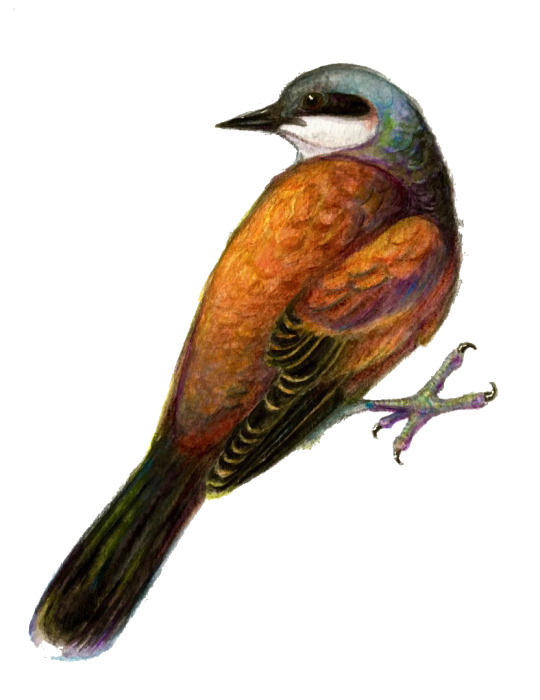

Limnofregata

By Ripley Cook

Etymology: Freshwater Frigatebird

First Described By: Olson, 1977

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Aequorlitornithes, Ardeae, Aequornithes, Suliformes, Fregatidae

Referred Species: L. azygosternon, L. hasegawai, L. hutchisoni

Status: Extinct

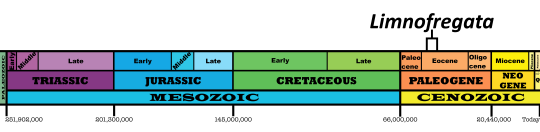

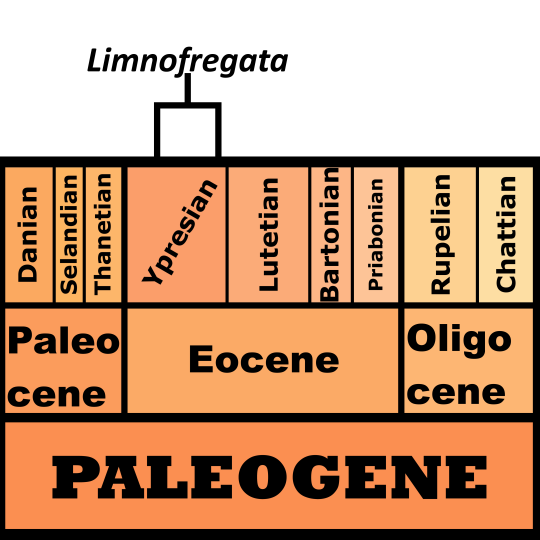

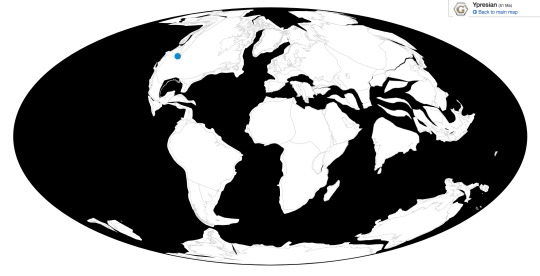

Time and Place: Limnofregata is known from between 53.5 and 48.5 million years ago, in the Ypresian age of the Eocene of the Paleogene

Limnofregata has been found entirely within the Fossil Butte Member of the Green River Formation in Wyoming

Physical Description: Limnofregata is one of the earliest known examples of the Frigatebirds - a group of water-associated birds with a distinctive appearance. These birds have long bills for catching fish in the oceans and huge, distinctive pouches on their throats. They are able to soar for weeks on end, making them highly adapted for their water-journeying lifestyle. Limnofregata, being a very early example of the group, look like what you’d expect a transitional form of the frigatebirds to be - showcasing some of the same distinct shape of the modern group, while still not being quite there yet.

Limnofregata showed significant similarity to living Frigatebirds - like living members of the species it had short, stocky legs, stronger bones in the wings, and wide hips. This indicates that it was already on the path towards high levels of specialization for flight. However, its wings were not quite as long, in terms of proportion, as living Frigatebirds; this indicates that it didn’t utilize soaring as much in its life. Limnofregata also had a shorter bill and long, slitlike nose openings, more like modern boobies; it also lacked the noticeable hook found on modern Frigatebird bills. The size of the nostrils reduced in Frigatebirds as they transitioned to more saltwater habitats (aka, the open ocean), so the large nostril openings in Limnofregata point to its freshwater habitat. Limnofregata was also not sexually dimorphic in terms of size, an important characteristic of living Frigatebirds.

Limnofregata varied in size amongst the different species, but in general it had a wingspan of between 100 to 120 centimeters - in Imperial units, that’s between 3 and 4 feet long. This is a little more than half the length of living Frigatebird wingspans, but their bodies are roughly the same size as living Frigatebird, adding more evidence to their wings being less adapted for soaring.

By Scott Reid

Diet: Given their distinct difference in beak shape compared to modern Frigatebirds, and their completely different habitat (rather than being associated with the open ocean, Limnofregata lived near a lake; read more in the Ecosystem subsection), it is unlikely that it had a similar diet. Instead, Limnofregata was probably more of an opportunist, like modern gulls - feeding on a wide variety of food, of which fish was only one kind of many. As such, it was much more omnivorous than its living relatives.

Behavior: Limnofregata was heavily associated with a lake ecosystem, and, as something more analogous to living gulls, it would have been the asshole of that lake ecosystem. Rather than soaring about looking for sources of fish, like living Frigatebirds, it would have probably stayed close to the shore and the edge of the freshwater lakes in its environment, feeding on smaller vertebrates and harrassing other birds in the area for their food, attempting to grab the catches of other birds and eating their fish instead of catching the food themselves. As opportunists, they would have congregated especially frequently at moments of extensive food production, such as when large numbers of fish died off in the ecosystem as oxygen depleted in the lakes.

Given that the sexes were alike in size, it’s possible that they didn’t have as extensive systems of sexual display as living Frigatebirds do; though, of course, no throat pouches have been fossilized either way, so we can’t be certain. As large numbers of these birds have been fossilized together, it is likely that they formed large flocks of convenience, like modern gulls today.

By José Carlos Cortés

Ecosystem: The Green River Formation is another example of a well-documented ecosystem of the global rainforest of the early Eocene; in fact, it is older than the Messel Pit, and showcases unique creatures as a result. Similar to the Messel Pit, the Green River Formation is associated with a fossil lake system scattered amongst the jungle; however, given that the animals of Green River were not quite as small as those of the Messel Pit, the vegetation does not seem to have been quite as dense. The dominant tree type surrounding the lake were sycamore trees, though ferns, palms, and many other plant types were present as well. The entire system was greatly affected by changes in sediment as the Rocky Mountains formed around them. This commonly lead to great influxes of nutrients - like when industrial companies dump phosphorus into lakes today - overwhelming the lake system and suffocating the fish inside. This influx of sediment and minerals allowed for the ecosystem’s unique preservation; it also would have lead to periodic upwelling of dead fish for Limnofregata to munch on. These fish included animals such as rays, catfish, suckers, and relatives of modern herrings and sardines, along with many others. Crocodiles such as Borealosuchus were present, and probably would have fed upon Limnofregata. There were also some of the earliest primates, bats, and an armadillo-like mammal as well.

Of course, birds were extremely common, to the point of having feathers preserved in many cases. Other dinosaurs known from the Fossil Butte Member include the Lithornithids (flighted, tree-dwelling relatives of modern Ostriches and Emu) Pseudocrypturus and Calciavis; the flamingo-like duck Presbyornis; the pheasant relative Gallinuloides; the early swift and hummingbird relative Eocypselus; the frogmouth-like Fluvioviridavis and Prefica; the mousebird relative Anneavis; the early woodpecker relative Neanis; the Parrots of Prey Cyrilavis and Tynskya; and the early passerine relatives with parrot feet Zygodactylus and Eozygodactylus. Thus, the Green River Formation was another example of a great place to see how dinosaurs were getting on after the extinction.

Other: Feather impressions are known from Limnofregata, but they aren’t very exciting in terms of morphology.

Species Differences: Since all three species are from the same place, they are mainly distinguished from one another based on shape and size. L. hasegawai was much larger, about the size of the largest modern Frigatebirds; L. azygosternon was somewhat somewhat smaller and more comparable with the smaller species of the group today. L. hutchisoni differs in terms of how its wing bones are shaped, but was large like L. hasegawai, potentially even larger.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the cut

Felice, R. N. 2014. Coevolution of caudal skeleton and tail feathers in birds. Journal of Morphology 275 (12): 1-10.

Grande, L., P. Bucheim. 1994. Palaeontological and Sedimentological Variation in Early Eocene Fossil Lake. Contributions to Geology, University of Wyoming 30: 45.

Hutchison, J. H. 2013. New turtles from the Paleogene of North America. In D. B. Brinkman, P. A. Holroyd, J. D. Gardner (eds.), Morphology and Evolution of Turtles 477-497

Mayr, G. 2009. Paleogene Fossil Birds. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg.

Mayr, G. 2017. Avian Evolution: The Fossil Record of Birds and its Paleobiological Significance. Topics in Paleobiology, Wiley Blackwell. West Sussex.

Olson, S. L. 1977. A Lower Eocene frigatebird from the Green River Formation of Wyoming (Pelecaniformes: Fregatidae). Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology 35:1-33

Olson, S. L., H. Matsuoka. 2005. New specimens of the early Eocene frigatebird Limnofregata (Pelecaniformes: Fregatidae), with the description of a new species. Zootaxa 1046: 1 - 15.

Orta, J. (2019). Frigatebirds (Fregatidae). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Smith, M. E., B. Singer, A. Carroll. 2003. 40Ar/39Ar Geochronology of the Eocene Green River Formation, Wyoming. Geological Society of America Bulletin 115 (5): 549 - 565. Stidham, T. A. 2014. A new species of Limnofregata (Pelecaniformes: Fregatidae) from the Early Eocene Wasatch Formation of Wyoming: implications for palaeoecology and palaeobiology. Palaeontology: 1 - 11.

#limnofregata#bird#dinosaur#frigatebird#palaeoblr#birblr#limnofregata azygosternon#limnofregata hasegawai#limnofregata hutchisoni#omnivore#paleogene#green river formation#north america#Aequorlitornithian#ardeaen#water wednesday#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#dinosaurs#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature#factfile#birds

123 notes

·

View notes

Text

Foro panarium

By Ripley Cook

Etymology: Breadbasket’s Hole

First Described By: Olson, 1992

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Columbaves, Otidimorphae, Musophagiformes

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: Between 53.5 and 48.5 million years ago, in the Ypresian of the Eocene

Foro is known from the Fossil Butte Member of the Green River Formation of Wyoming

Physical Description: Foro had a downward sloping, distinctive skull, with a slight point to the tip at the end of the beak, hanging off of a long neck. It had a large, rounded head, a fairly stout body, and long spindly legs. Its wings were decently sized too, making this in general a very lanky sort of bird. However, these wings were probably weak, and in addition to the stocky body it wouldn’t have been the world’s greatest flier. As for its general size, it was probably about the size of a modern roadrunner, reaching between 22 and 24 centimeters in length; it was probably similar in many ways to living roadrunners, while simultaneously being like a bustard, a hoatzin, and a relative of the modern day turacos. Evolution is wild, man.

Diet: Given it had the general head-shape of a Hoatzin, it seems at least somewhat likely that Foro was herbivorous, though this was of course evolved convergently to the Hoatzin (as Foro was probably a stem-turaco). This is further corroborated by the fact that turacos are also mostly herbivorous.

Behavior: Foro was a ground-dwelling bird, rather than tree-dwelling like modern turacos; it would use its long legs to wander about its lake environment, searching for food to eat and moving through more difficult ground material such as mud and dirt. In this way it was much more like a living bustard than a living turaco, indicating the bustard way of life was actually the ancestral case for cuckoos and turacos before they adapted for their unique arboreal roles. As a weird cross between a bustard and a wading bird, it would have spent a good amount of time moving about the ground, grabbing food from the mud and in the low-lying plants, and running away rapidly at the first sign of danger. It was still able to fly, and would use that when the danger was way too close. As a bird, it would have been an active animal; it is especially uncertain whether or not it was particularly social, but it probably took care of its young.

By Scott Reid

Ecosystem: The Green River Formation is a famous environment from the early Eocene of North America, showcasing the burst of creatures after the end-Cretaceous extinction that came forward as the global rainforest reached its peak, and serving as a host of creatures that were precursors to modern forms. This was a fossil lake system scattered across the jungle in loosely dense vegetation, including sycamore trees and ferns, palms, and many other kinds of plants. As the Rocky Mountains formed nearby, nutrients would randomly spike in the lake, dumping phosphorus and suffocating the fish inside. This lead to unique preservation and an amazing number of fossils from Green River. Here there were a variety of rays, catfish, herrings, and countless other fish; crocodilians like Borealosuchus; early primates, bats, and an armadillo-esque mammal. Birds were also extremely common: there was the gull-like frigatebird Limnofregata, the Lithornithids Pseudocrypturus and Calciavis, the flamingo-duck Presbyornis, the pre-pheasant Gallinuloides, the early swift-hummingbird Eocypselus, the frogmouth-esque Fluvioviridavis and Prefica, the mousebird Anneavis, the woodpecker Neanis, the Parrots of Prey Cyrilavis and Tynskya, and the parrot-footed passerines Zygodactylus and Eozygodactylus. In this way, Foro was a notable and usual member of the ecosystem, showcasing the weird mode of evolution of the modern Turaco group.

Other: Foro has been the subject of a fascinating research history, with it originally being called its own thing in the Cuckoos, and then thought to be a Hoatzin for a while, and then finally assigned as a stem-turaco. This is of utter importance because it showcases how neotropical birds like the turacos (which, today, are limited to Africa) were once widespread - this also applies to many other groups of birds, and this collapse of tropical birds in North America and Europe is an object of intense study. As the Global rainforest collapsed, the evolutionary trajectory of modern birds changed dramatically, and Foro was a part of that. On the other hand, Foro and other birds known from the Paleocene and Eocene epochs showcase how dinosaurs managed to bounce back from the extinction; birds were more ground-dwelling than tree-dwelling at first, given the lack of trees in impact winter; Foro was a ground-dwelling bird, but one on the path to tree-life, much like many other dinosaurs in this early part of the new era.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Felice, R. N. 2014. Coevolution of caudal skeleton and tail feathers in birds. Journal of Morphology 275 (12): 1-10.

Field, D. J., A. Bercovici, J. S. Berv, R. Dunn, D. E. Fastovsky, T. R. Lyson, V. Vajda, J. A. Gauthier. 2018. Early Evolution of Modern Birds Structured by Global Forest Collapse at the End-Cretaceous Mass Extinction. Current Biology 28: 1825 - 1831.

Field, D. J., A. Y. Hsiang. 2018. A North American stem turaco, and the complex biogeographic history of modern birds. BMC Evolutionary BIology 18: 102.

Grande, L., P. Bucheim. 1994. Palaeontological and Sedimentological Variation in Early Eocene Fossil Lake. Contributions to Geology, University of Wyoming 30: 45.

Hutchison, J. H. 2013. New turtles from the Paleogene of North America. In D. B. Brinkman, P. A. Holroyd, J. D. Gardner (eds.), Morphology and Evolution of Turtles 477-497.

Mayr, G. 2009. Paleogene Fossil Birds. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg.

Mayr, G. 2017. Avian Evolution: The Fossil Record of Birds and its Paleobiological Significance. Topics in Paleobiology, Wiley Blackwell. West Sussex.

Miller, A. H. 1953. A fossilized hoatzin from the Miocene of columbia. Auk 70: 484 - 489.

Olson, S. L. 1977. A Lower Eocene frigatebird from the Green River Formation of Wyoming (Pelecaniformes: Fregatidae). Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology 35:1-33.

Olson, S. L. 1992. A new family of primitive landbirds from the Lower Eocene Green River Formation of Wyoming. Papers in avian paleontology honoring Pierce Brodkorb: 127 - 136.

Olson, S. L., H. Matsuoka. 2005. New specimens of the early Eocene frigatebird Limnofregata (Pelecaniformes: Fregatidae), with the description of a new species. Zootaxa 1046: 1 - 15.

Smith, M. E., B. Singer, A. Carroll. 2003. 40Ar/39Ar Geochronology of the Eocene Green River Formation, Wyoming. Geological Society of America Bulletin 115 (5): 549 - 565. Stidham, T. A. 2014. A new species of Limnofregata (Pelecaniformes: Fregatidae) from the Early Eocene Wasatch Formation of Wyoming: implications for palaeoecology and palaeobiology. Palaeontology: 1 - 11.

#Foro panarium#Foro#Bird#Turaco#Dinosaur#Birds#Dinosaurs#Palaeoblr#Birblr#Factfile#Columbavian#Paleogene#North America#Terrestrial Tuesday#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

142 notes

·

View notes

Text

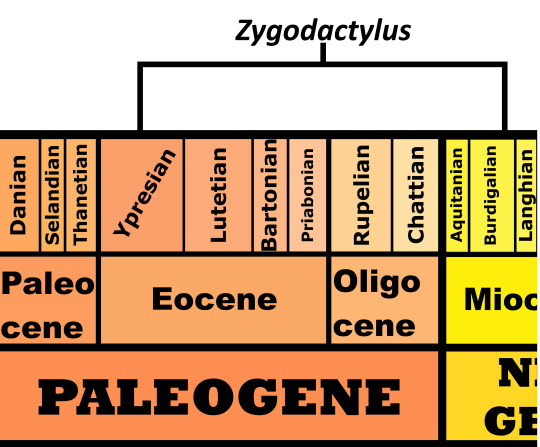

Zygodactylus

By José Carlos Cortés

Etymology: The one with two toes forward and two backward

First Described By: Ballman, 1969

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Australaves, Psittacopasserae, Passeriformes, Zygodactylidae

Referred Species: Z. grivensis, Z. ignotus, Z. luberonensis, Z. grandei, Z. ochlurus

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: Between 52 to 17 million years ago, from the Ypresian of the Eocene through the Burdigalian of the Miocene

Zygodactylus is known from the Fossil Butte Member of the Green River Formation, the Renova Formation, the Revest-des-Brousses Formation, and the Wintershof-West Formation, a range extending over both North America and Europe

Physical Description: Zygodactylus was a small tree-dwelling bird, about the size of living tyrant-flycatchers (so no more than 12 or so centimeters long, probably usually smaller than this). It resembled living songbirds in most ways - it had a round body, small head, long and very skinny legs, and round wings. However, Zygodactylus differed from extinct songbirds in one very notable and important way: instead of having three toes pointed forward and one toe pointed backward, Zygodactylus had two toes pointed forward and two backward. This is important for evolutionary biology related reasons - which I’ll get into in the “other” section. They also had long, pointed beaks, like many kinds of living passerines. Any potential color of Zygodactylus has not been studied, but it stands to reason that it would have some distinct patterning to stand out during mating displays and in its forested habitats.

Diet: Based on the shape of the beak, it seems likely that Zygodactylus fed mainly on invertebrates and insects, using the sharp beak to spear slimy food or dig into bark for hidden grubs.

By Ripley Cook

Behavior: Zygodactylus would have been a primarily tree-dwelling bird, spending most of its time walking among the branches and searching for food. It would have used its specialized foot structure to hold onto tree branches and even trunks, though its toes were small and skinny and not the most adapted for trunk-grabbing. It would have probably spent a good amount of its time hopping from tree to tree on its quest, and possibly dug into wood to find food. This was a common bird, and as such it stands to reason that Zygodactylus would have been at least somewhat social - though whether that took the form of small family flocks or large flocks is uncertain. It would have taken care of its young, though beyond that we know little of its behavior.

Ecosystem: Zygodactylus lived for an extremely long period of time in Earth’s history, going from the origins of many modern groups of birds in the Eocene until the diversification of these groups into their specific families in the Miocene. In general, Zygoadctylus kept to forested environments, even as the global rainforest of the Eocene depleted and was replaced by more varied habitats, including vast arid shrubland and the first grasslands. Zygodactylus is known from such varying environments from the rainforest-lake of the Green River Formation, to a coastal mangrove forest, to a shoreline wood.

Green River Formation by Julius Cystoni

In the lakeside rainforest of the Green River Formation, Zygodactylus lived amongst sycamore trees along with ferns and palms, affected by the constant change of the Rocky mountains around them - which would periodically dump phosphorus into the lakes. There were a variety of fish such as rays, catfish, suckers, and herrings and sardines. Crocodiles like Borealosuchus were frequent, as well as many early primates, hoofed mammals, bats, and an armadillo-esque mammal. Dinosaurs were some of the most iconic creatures at the Fossil Lake, including the seagull-like Frigatebird Limnafregata, the flighted ratites Pseudocrypturus and calciavis, the flamingo-duck Presbyornis, the pheasant Gallinuloides, the early swift-hummingbird Eocypselus, the frogmouth-esque Fluvioviridavis and Prefica, the mousebird Anneavis, the woodpecker Neanis, the Parrots of Prey Cyrilavis and Tynskya, and Zygodacytlus’ own cousin Eozygodactylus. Of these, Zygodactylus would have had to watch out the most for its own relatives, the Parrots of Prey!

In the Dunbar Creek member of the Renova Formation, Zygodactylus lived in a more transitional environment, as the global rainforests were replaced with plains and other arid habitats. Here there were a variety of pine trees, as well as flowering plants like violets, roses, grapes, maples, and nogals. This was a series of woods surrounding ponds and streams feeding into said ponds, with plenty of habitats for Zygodactylus to hang out in. There were plenty of mammals here, including early dogs and horses, marsupials and rabbits, rodents and brontotheres, as well as rhinos. Other birds are not known from this formation.

By Ashley Patch

In the coastal mangrove of the Rupelian of Southern France, Zygodactylus was joined by a wide variety of mammals - including rodents, horse relatives, ruminants, hedgehogs, and truly weird and giant hoofed mammals like Anthracotherium. As for other dinosaurs, there were early trogon relatives like Primotrogon, early hummingbirds like Eurotrochilus, early cuckoos like Eocuculus, and crane relatives like Parvigrus.

Finally, in the shoreline woodland of the Burdigalian of Germany, Zygodactylus lived among a wide variety of flowering trees, more so than conifers that had been more prevalent in the Eocene. Asterids, buckthorns, grapes, maples, and magnolias were especially common. Here, rodents were the primary mammalian neighbors, though there were some ruminants, bats, and carnivorous mammals like Prosansanosmilus. Snakes were even more common, though, and would have been major predators of Zygodactylus, such as boas and cobras. Birds were rarer here, though the pheasant Paleortyx was present alongside Zygodactylus.

By Jack Wood

Other: Zygodactylus is of fundamental importance because it is a missing link - a fossil that confirms the weird relationships we recover with genetic data. For a long time, genetic studies of the relationships between birds revealed a result literally no one would guess based on their shapes and ecologies: parrots and passerines were sibling groups. This was a major disconnect for researchers, since for a long time it was thought that passerines were more closely related to some of the other large tree-dwelling dinosaur groups with three toes forward and one back - namely, mousebirds and quetzals. So, what was needed was something linking the creatures with two forward and two back - like passerines - and the three forward one back songbirds. Zygodactylus and its relatives were the answer to that question. Being - by and large - almost identical to living passerines, these ancient birds had the legs and bodies of their living relatives, but the feet of their cousins. This showcases that, in terms of evolving for tree-dwelling, songbirds focused on their wing shape and skinny legs before changing up their feet. This makes Zygodactylus - and its relatives - utterly vital transitional fossils for the evolution of the most speciose group of living dinosaurs, the songbirds.

Species Differences: Z. grivensis and Z. grandei are known from the Green River Formation of Wyoming, with Z. grandei having shorter foot bones; Z. ochlurus is known from the Dunbar Creek Member of the Renova Formation; Z. luberornensis is known from the Revest-des-Brousses Formation of France; and Z. ignotus is known from the Wintershof-West of Germany.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Grande, L., P. Bucheim. 1994. Palaeontological and Sedimentological Variation in Early Eocene Fossil Lake. Contributions to Geology, University of Wyoming 30: 45.

Hieronymus, T. L., D. A. Waugh, J. A. Clarke. 2019. A new zygodactylid species indicates the persistence of stem passerines into the early Oligocene in North America. BMC Evolutionary Biology 19: 3.

Hutchison, J. H. 2013. New turtles from the Paleogene of North America. In D. B. Brinkman, P. A. Holroyd, J. D. Gardner (eds.), Morphology and Evolution of Turtles 477-497

Mayr, G. 2008. Phylogenetic affinities of the enigmatic avian taxon Zygodactylus based on new material from the early Oligocene of France. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 6(3):333-344

Mayr, G. 2009. Paleogene Fossil Birds. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg.

Mayr, G. 2017. Avian Evolution: The Fossil Record of Birds and its Paleobiological Significance. Topics in Paleobiology, Wiley Blackwell. West Sussex.

Olson, S. L. 1977. A Lower Eocene frigatebird from the Green River Formation of Wyoming (Pelecaniformes: Fregatidae). Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology 35:1-33

Olson, S. L., H. Matsuoka. 2005. New specimens of the early Eocene frigatebird Limnofregata (Pelecaniformes: Fregatidae), with the description of a new species. Zootaxa 1046: 1 - 15.

Smith, M. E., B. Singer, A. Carroll. 2003. 40Ar/39Ar Geochronology of the Eocene Green River Formation, Wyoming. Geological Society of America Bulletin 115 (5): 549 - 565. Stidham, T. A. 2014. A new species of Limnofregata (Pelecaniformes: Fregatidae) from the Early Eocene Wasatch Formation of Wyoming: implications for palaeoecology and palaeobiology. Palaeontology: 1 - 11.

Smith, N. A., A. M. DeBee, J. A. Clarke. 2018. Systematics and phylogeny of the Zygodactylidae (Aves, Neognathae) with description of a new species from the early Eocene of Wyoming, USA. PeerJ 6: e4950.

#Zygodactylus#Bird#Dinosaur#Songbird#Passeriform#Birblr#palaeoblr#factfile#perching bird#Zygodactylus grivensis#Zygodactylus ignotus#Zygodactylus luberonensis#Dinosaurs#Birds#prehistoric life#paleontology#prehistory#neogene#paleogene#north america#eurasia#insectivore#Songbird Saturday & Sunday#Zygodactylus grandei#Zygodactylus ochlurus

146 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fluvioviridavis platyrhamphus

By Ripley Cook

Etymology: Green River Bird

First Described By: Mayr & Daniels, 2001

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Strisores, Podargiformes

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: Between 53.5 and 48.5 million years ago, in the Ypresian of the Eocene of the Paleogene

Fluvioviridavis is known from the Fossil Butte Member of the Green River Formation of Wyoming

Physical Description: Fluvioviridavis was a stem-frogmouth, and looked nearly like a modern one when you get right down to it - it had a normal sized head with a huge triangular beak attached to it, a fairly round body, long wings, and short legs, so that it would have looked very squat in life. In addition to looking very squat, it would have also been able to compact its neck so that it could look even more squat - giving it a very long neck tucked up tight inside its throat. Its beak, though wide and flattened like modern frogmouths, is still fairly narrow and more pointed than living members of the group, making it distinctly different from its modern relatives.

Diet: Like modern frogmouths, Fluvioviridavis probably ate small to medium sized animals, especially insects, small mammals, reptiles, frogs, and even possibly smaller birds.

By Scott Reid

Behavior: Like its modern relatives, Fluvioviridavis probably spent most of its time sitting on trees, scrunched up to blend in with the trees around it. It would remain motionless, so prey wouldn’t notice it as it watched from above. Then it would divebomb food, catching it on the ground before it even knew what was happening. In addition to this, Fluvioviridavis probably would catch flies in mid-air, diving them rapidly to catch them in their ridiculous mouths.

Fluvioviridavis would have been a more aerial bird than living frogmouths, spending most of its time in the air catching food there, even though it would have been entirely capable of perching as per its feet. Though, fascinatingly enough, if Fluvioviridavis is a stem-frogmouth as is assumed, it showcases an early stage in the evolution of perching in this group, still having claws and other features in its feet later lost by the group as a whole. Still, the general weird shape of the Frogmouths evolved very early in the Frogmouth lineage.

Fluvioviridavis, being a bird, probably took care of its young; though other social characteristics of this species are unknown. It’s possible it was something of a loner, since it isn’t the most common of fossils in an environment known for having an abundance of bird fossils.

By José Carlos Cortés

Ecosystem: The Green River Environment was just one of many very well preserved ecosystems from the Global Rainforest of the early Eocene - being older than the Messel Pit, it showcases very distinctive creatures. This environment was a fossil lake scattered amongst the jungle, with only moderately dense vegetation compared to, say, Europe. The lake was dominated by sycamore trees, as well as ferns, palms, and other kinds of trees and flowers. This was an environment greatly affected by the forming of the Rocky Mountains, which lead to rapid influxes of nutrients - overwhelming the lakes and suffocating the fish inside. This lead to unique preservation, and a wide variety of food for Fluvioviridavis to feed on. There were a lot of different kinds of dinosaurs there, including the Lithornithids Pseudocrypturus and Calciavis; the flamingo-duck Presbyornis; the early pheasant Gallinuloides; the early swift and hummingbird relative Eocypselus; another frogmouth relative, Prefica; an early mousebird, Anneavis; the early woodpecker Neanis; parrots of prey such as Cyrilavis and Tynskya; and some of the earliest passerines, Zygodactylus and Eozygodactlyus - with all of the animals showcasing the explosion of Neoavians after the end-Cretaceous Extinction. There were also mammals such as early primates, bats, and armadillos; crocodilians like Borealosuchus; and a variety of rays, catfish, suckers, herrings, and sardines.

Other: It is possible that Fluvioviridavis wasn’t actually a stem-frogmouth at all, but an unrelated strisorian that explored the frogmouth niche before frogmouths came along. More research is needed to figure this out, but regardless, Fluvioviridavis showcases an interesting step in early bird evolution after the end-Cretaceous extinction! This bird might have also spread to the London Clay Environment across the sea, but that’s not been confirmed yet.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Grande, L., P. Bucheim. 1994. Palaeontological and Sedimentological Variation in Early Eocene Fossil Lake. Contributions to Geology, University of Wyoming 30: 45.

Mayr, G. & Daniels, M. 2001. "A new short-legged landbird from the early Eocene of Wyoming and contemporaneous European sites". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 46 (3): 393-402.

Mayr, G. 2017. Avian Evolution: The Fossil Record of Birds and its Paleobiological Significance. Topics in Paleobiology, Wiley Blackwell. West Sussex.

Nesbitt, S. J.; Ksepka, D. T.; Clarke, J. A. (2011). Iwaniuk, Andrew, ed. "Podargiform Affinities of the Enigmatic Fluvioviridavis platyrhamphus and the Early Diversification of Strisores ("Caprimulgiformes" + Apodiformes)". PLoS ONE. 6 (11): e26350.

Smith, M. E., B. Singer, A. Carroll. 2003. 40Ar/39Ar Geochronology of the Eocene Green River Formation, Wyoming. Geological Society of America Bulletin 115 (5): 549 - 565. Stidham, T. A. 2014. A new species of Limnofregata (Pelecaniformes: Fregatidae) from the Early Eocene Wasatch Formation of Wyoming: implications for palaeoecology and palaeobiology. Palaeontology: 1 - 11.

#Fluvioviridavis#Fluvioviridavis platyrhamphus#Frogmouth#Bird#Dinosaur#Strisorian#Birds#Dinosaurs#Insectivore#Paleogene#North America#Flying Friday#Birblr#Palaeoblr#Factfile#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

185 notes

·

View notes

Note

I assume you’re familiar with the claim that Caenagnathus can’t be a synonym of Chirostenotes since they don’t clade together in most phylogenies. Isn’t this a fairly weak argument since individual bones are often prone to convergence (see discussion of Limnofregata in Olson 1977)?

I certainly wouldn’t make such a confident assertion solely on that basis. That being said, if one were to recover that result in their phylogenetic analysis, it wouldn’t be unreasonable to interpret that as evidence against synonymy. Whether or not that interpretation remains reasonable in the face of other studies is a different matter.

0 notes