#ardeaen

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Balaeniceps rex

By Olaf Oliviero Riemer, CC BY-SA 3.0

Etymology: Whale Head

First Described By: Gould, 1850

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Aequorlitornithes, Ardeae, Aequornithes, Pelecaniformes, Balaenicipitidae

Status: Extant, Vulnerable

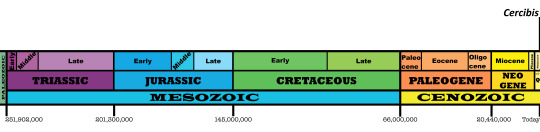

Time and Place: Within the last 10,000 years, in the Holocene of the Quaternary

The Shoebill is known from eastern central Africa

Physical Description: There is no other dinosaur quite like the Shoebill. It is one of the most visually distinctive creatures, with traits monstrous and familiar that make it difficult to really understand exactly what you’re looking at. They stand up to 140 centimeters in height, which yes, is the height of a human being on the shorter side. They can even reach 152 centimeters tall - the same height as a 5 foot tall person. They have very long, skinny legs, with giant toes on their feet that are widely splayed out. Their bodies are huge, with short tails and bulky torsos. Their backs are grey, and their belly feathers are white. Their necks are a lighter grey, and there is some dark speckling all over their wings and right beneath their necks. Their heads continue that light grey coloration, and have small tufts of feathers as a crest on the back of the head. Shoebills also happen to feature yellow, unblinking, perfectly circular eyes, which is unsettling at best. They have heavy eyebrows of feathers over their eyes, giving them a look like they’re always glaring at you - which is even more disconcerting considering the giant, wide, scoop-shaped bill that the Shoebill is named for. The bill is orange, and ends in a small hook, just in case you weren’t terrified enough.

By Peter Halasz, CC BY-SA 2.5

Diet: Shoebills feed mainly on fish - especially lungfish, though most large fish are acceptable. Amphibians, young crocodilians, water snakes, rodents, and young waterfowl are also fed upon by these giant terrifying creatures.

By Snowmanradio, CC BY-SA 2.0

Behavior: Shoebills are calculating bastards - they’ll hover around lakesides and swamps with low oxygen in the water, which forces lungfish to come up to breathe - so that the Shoebill can then lean down and scoop them up. They are loners during the hunt, carefully taking each step as they make sure to not sink too far into the mud and weeds where they live. Their lunging after food is hard to miss - their mouths open wide, revealing how huge those bills really are, and giving it a sinister smile. These lunges are usually startling, as the Shoebill is usually still for a very long time before it goes after prey. It is as if a statue had suddenly come to life. This is especially disconcerting when the Shoebill opts for standing on floating vegetation - just casually going down with the current as though they were a giant Jacana. They tend to defend territories for food, at least somewhat, not coming closer than twenty meters to another Shoebill during feeding. They don’t sense their prey with feel, but entirely by sight - making them very unblinking and focused, adding to their strange aura. Shoebills are also usually silent, which just makes their entire aesthetic even more terrifying. When they do dare to make sounds, they make very raucous cries - usually while they fly.

By Petr Simon

Yes, yes they can fly. Shoebills are some of the largest flighted birds today, which does not help. They hold their wings flat, pulling in their necks to their bodies to aid in making their flight more efficient. They have some of the slowest flaps of any bird, at 150 flaps per minute. They fly only a few meters at a time, and usually prefer to glide as much as possible. The farthest any Shoebill as traveled at one time seems to be 20 meters. As such, Shoebills are not very mobile birds, and they usually only move from place to place based on food availability.

By African Parks/Bengweulu Wetlands Photography

Shoebills begin breeding depending on the water levels of their habitat at a given time. They lay their eggs when the rains begin to end and the waters start to recede; as such, the chicks hatch and fledge late in the dry season. They nest alone, though there are possible reports that they may form some breeding colonies in South Sudan. They make nests out of grass in a mound that is three meters wide, usually placed on a small island or on floating vegetation amongst dense papyrus. They lay two eggs that are incubated for a month. The chickare cute, fluffy, and grey, with tiny regular sized bills. They then fledge a little more than three months later and, what’s more, usually only one chick survives. The chicks and parents will make whining and mewing to each other to get attention and beg for food. Sometimes, the young will make hiccups as begging calls. The parents are constantly with the young for the first forty days of rearing, only briefly leaving to get food and water or nest material. As the chicks age, the parents spend more and more time away, but they still bring food regularly. The chicks, after fledging, remain dependent on the parents for food for a few more years. They reach reproductive age at around three to four years. Displays often including mooing and bill clattering, which can be accompanied by the shaking of the head from side to side, which is quite the undertaking for a bird with such a large head. Breeding pairs stay together for the season, and break up when the chicks leave the nest. Shoebills can live up to fifty years, which is aided by the fact that they tend to not have predators after reaching full size.

By Hans Hillewaert, CC BY-SA 3.0

Ecosystem: Shoebills stick to marshes, especially papyrus marshes and those with reeds and cattails. They will also gather around marshy lakesides, especially near Lake Victoria. They go wherever they can find floating vegetation to stand upon, including ricefields. They tend to go where animals such as hippopotamus go, since the hippo can dredge up food that the Shoebill can then feed upon.

By Fritz Geller-Grimm, CC BY-SA 2.5

Other: Shoebills are currently considered vulnerable to extinction, with 5000 to 8000 birds thought to be remaining in the wild (though that may be low and there may be as many as 10,000). The reasons for this decline in population is partially due to habitat loss - the Shoebill is dependent on papyrus swamps and other wetland habitats, which are targeted by drainage schemes and other development activities. Animals being brought across these swamps and trampling their young also majorly contributes to population decline. It is a very unique bird and a very popular one, so luckily there are some conservation efforts ongoing, especially in zoos. Some hunting is also contributing to population loss. Despite these conservation efforts, only once has the Shoebill been successfully bred in captivity.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Elliott, A., Garcia, E.F.J. & Boesman, P. (2019). Shoebill (Balaeniceps rex). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Guillet, A (1978). "Distribution and Conservation of the Shoebill (Balaeniceps Rex) in the Southern Sudan". Biological Conservation. 13 (1): 39–50.

Hackett, SJ; Kimball, RT; Reddy, S; Bowie, RC; Braun, EL; Braun, MJ; Chojnowski, JL; Cox, WA; Han, KL; et al. (2008). "A phylogenomic study of birds reveals their evolutionary history". Science. 320 (5884): 1763–8.

Hagey, J. R.; Schteingart, C. D.; Ton-Nu, H.-T. & Hofmann, A. F. (2002). "A novel primary bile acid in the Shoebill stork and herons and its phylogenetic significance". Journal of Lipid Research. 43 (5): 685–90.

Hall, Whitmore (1861). The principal roots and derivatives of the Latin language, with a display of their incorporation into English. London: Longman, Green, Longman & Roberts. p. 153.

Hancock & Kushan, Storks, Ibises and Spoonbills of the World. Princeton University Press (1992),

Houlihan, Patrick F. (1986). The Birds of Ancient Egypt. Wiltshire: Aris & Phillips. p. 26.

Jasson, J.; Nahonyo, Cuthbert; Lee, Woo; Msuya, Charles (March 2013). "Observations on nesting of shoebill Balaeniceps rex and wattled crane Bugeranus carunculatus in Malagarasi wetlands, western Tanzania". African Journal of Ecology. 51 (1): 184–187.

Mayr, Gerald (2003). "The phylogenetic affinities of the Shoebill (Balaeniceps rex)". Journal für Ornithologie.

Mikhailov, Konstantin E. (1995). "Eggshell structure in the shoebill and pelecaniform birds: comparison with hamerkop, herons, ibises and storks". Canadian Journal of Zoology. 73 (9): 1754–70.

Muir, Allan; King, C.E. (January 2013). "Management and husbandry guidelines for Shoebills Balaeniceps rex in captivity". International Zoo Yearbook. 47 (1): 181–189.

Stevenson, Terry and Fanshawe, John (2001). Field Guide to the Birds of East Africa: Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi. Elsevier Science.

Tomita, Julie (2014). "Challenges and successes in the propagation of the Shoebill Balaeniceps rex: with detailed observations from Tampa's Lowry Park Zoo, Florida". International Zoo Yearbook. 132 (1): 69–82.

Williams, J.G; Arlott, N (1980). A Gield Guide to the Birds of East Africa. Collins.

#Balaeniceps rex#Balaeniceps#Shoebill#Bird#Dinosaur#Birblr#Factfile#Ardeaen#Aequorlitornithian#Water Wednesday#Piscivore#Birds#Dinosaurs#Quaternary#Africa#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

729 notes

·

View notes

Text

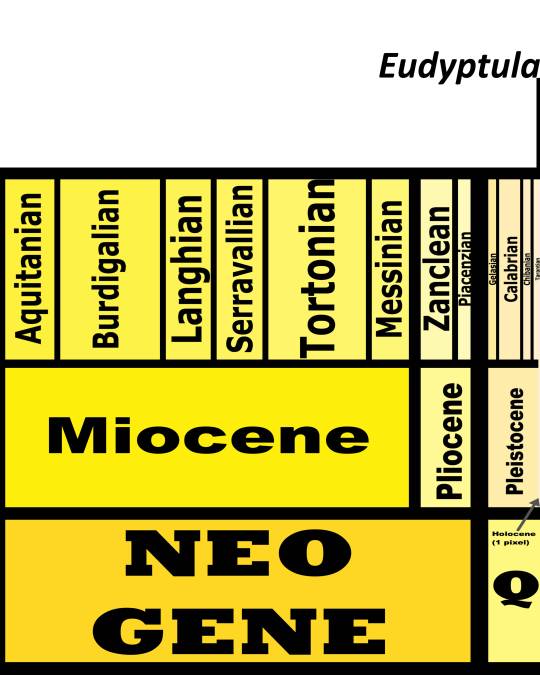

Eudyptula minor

By J. J. Harrison, CC BY-SA 3.0

Etymology: Good Diver

First Described By: Bonaparte, 1856

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Aequorlitornithes, Ardeae, Aequornithes, Austrodyptornithes, Sphenisciformes, Spheniscidae

Status: Extant, Least Concern

Time and Place: From 12,000 years ago until today, in the Holocene of the Quaternary

Little Penguins are known from the coast of Australia and New Zealand

Physical Description: Little Penguins are some of the most adorable penguins alive today, and the reason is clear: they’re smol! Little Penguins range in size between 40 and 45 centimeters in length, and none weigh more than 2.1 kilograms. They are a blue-grey on their backs and white on their bellies and necks. They have very small flippers, which can be entirely blue or blue only in the center with white banding around it. They have short little tails and small feet, which are formed into lightly orange flippers. Their beaks are short and round, and either light in color or dark depending on the population. The juveniles tend to be a somewhat duller color than the adults, but usually very similar overall.

By Magnus Kjaergaard, CC BY 3.0

Diet: Little Penguins feed mainly on fish that form schools in the pelagic zone of the ocean (rather than closer to the coast). They’ll also feed on cephalopods and crustaceans.

By Francesco Veronesi, CC BY-SA 2.0

Behavior: These nocturnal penguins will capture their food via pursuit-diving, mainly swimming around schools of fish in tighter and tighter circles until finally - woosh! - they dive into the middle and grab as much food as they can. In shallower water, they do pursue the fish more directly. They can dive as deep as 50 meters underwater, sometimes more - including 69 meters deep. They go up to 62 kilometers away from the nesting and sleeping colony sites, though they can usually only go a fraction of that in a single day and longer distances are reserved for multiple day trips. Females tend to forage more than the males. They feed alone, though they do forage in groups. They are extremely noisy in their colonies, making a variety of trills, brays, growls, grunts, yelping, trumpeting, and wailing sounds to one another. They do not migrate, but do stay near the breeding colony extensively during the moulting and nesting season. Juveniles will leave the colony for a large amount of time, but do eventually return to breed where they were born.

By Phillip Island Tourism, CC BY-SA 4.0

Little Penguins begin breeding in July and continue through December, though it varies from colony to colony and from year to year. They tend to stick to one nest site for their whole lives and are also fairly monogamous, though they do divorce from their partners around 76% of the time. If they are unsuccessful in raising any chicks one year, the next year they are more likely to divorce than not. The nests are made in a little bit far apart from one another in the colonie, usually a burrow in the sand lined with plant material. Usually two eggs are laid in the nest and are incubated for a little more than one month by both parents. The chicks hatch extremely fluffy and greyish-brown; they then molt to look dark brown and grey another month later. At this time young birds will form creches together for two more months, hanging out and learning from each other. They then fledge and become juveniles two more months later. They become sexually mature at two to four years of age, and can live for up to 20 years (though shorter is more common). The chicks and nesting colonies tend to feed at dusk.

By Mark Nairn, CC BY 3.0

Ecosystem: Little Penguins live mainly in sandy and rocky coasts, usually near the bases of cliffs and in sand dunes. They will spend most of their time in temperate to sub-arctic marine waters, many miles offshore. They are preyed upon by cats, dogs, rats, foxes, lizards, snakes, ferrets, stoats, seals, and some other ocean predators. They are mostly affected by introduced mammalian predators at this time.

By fir0002, GFDL 1.2

Other: While Little Penguins are, overall, doing alright and are even common in terms of population management; however, a number of human-created threats are affecting certain colonies and bringing many of them to the verge of collapse. Uncontrolled hunting by domesticated dogs and cats are major causes of colony destruction, as are oil spills, fishing interactions (including being caught in nets), human interference and development, as well as cullings by humans attempting to manage populations of other birds. As such, Little Penguins are of major interest for ecological groups in order to preserve their populations in light of these threats. Fossils of this species are known from its current range from the recent ice age.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources Under the Cut

Baird, R. F. 1992. Fossil avian assemblage of Pitfall Origin from Holocene sediments in Amphitheatre Cave (G-2), South-western Victoria, Australia. Records of the Australian Museum 44:21-44.

Banks, Jonathan C.; Mitchell, Anthony D.; Waas, Joseph R.; Paterson, Adrian M. (2002). "An unexpected pattern of molecular divergence within the blue penguin (Eudyptula minor) complex". Notornis. 49 (1): 29–38.

Bethge, P; Nicol, S; Culik, BM & RP Wilson (1997) "Diving behaviour and energetics in breeding little penguins (Eudyptula minor)". Journal of Zoology 242: 483-502.

Boessenkool, S., J. J. Austin, T. H. Worthy, P. Scofield, A. Cooper, P. J. Seddon, and J. M. Waters. 2009. Relict or colonizer? Extinction and range expansion of penguins in southern New Zealand. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 276:815-821.

Carroll, R. L. 1988. Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution 1-698.

Chiaradia, A., Forero, M. G., Hobson, K. A., and Cullen, J. M. (2010) Changes in diet and trophic position of a top predator 10 years after a mass mortality of a key prey. – ICES Journal of Marine Science, 67: 1710–1720.

Clements, J. F., T. S. Schulenberg, M. J. Iliff, D. Roberson, T. A. Fredericks, B. L. Sullivan, and C. L. Wood. 2017. The eBird/Clements checklist of birds of the world: v2017.

Flemming, S.A., Lalas, C., and van Heezik, Y. (2013) "Little penguin (Eudyptula minor) diet at three breeding colonies in New Zealand". New Zealand Journal of Ecology 37: 199–205.

Fordyce, R. E. 1991. The Australasian marine vertebrate record and its climatic and geographic implications. In P. Vickers-Rich, J. M. Monaghan, R. F. Baird, T. H. Rich (eds.), Vertebrate Palaeontology of Australasia 1165-1190.

Grosser, Stefanie; Burridge, Christopher P.; Peucker, Amanda J.; Waters, Jonathan M. (2015-12-14). "Coalescent Modelling Suggests Recent Secondary-Contact of Cryptic Penguin Species". PLOS ONE. 10 (12): –0144966.

Grosser, Stefanie; Rawlence, Nicolas J.; Anderson, Christian N. K.; Smith, Ian W. G.; Scofield, R. Paul; Waters, Jonathan M. (2016-02-10). "Invader or resident? Ancient-DNA reveals rapid species turnover in New Zealand little penguins". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 283 (1824): 20152879.

Littlely, Bryan (10 October 2007). "Fur seals threat to Granite Island penguins". The Advertiser. p. 23.

Martínez, I., Christie, D.A., Jutglar, F. & Garcia, E.F.J. (2019). Little Penguin (Eudyptula minor). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Numata, M; Davis, L & Renner, M (2000) "[Prolonged foraging trips and egg desertion in little penguins (Eudyptula minor)]". New Zealand Journal of Zoology 27: 291-298.

Rawlence, N. J., A. Kardamaki, L. J. Easton, A. J. D. Tennyson, R. P. Scofield and J. M. Waters. 2017. Ancient DNA and morphometric analysis reveal extinction and replacement of New Zealand’s unique black swans. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 284:20170876.

Rodríguez, A., Chiaradia, A., Wasiak, P., Renwick, L., and Dann, P.(2016) "Waddling on the Dark Side: Ambient Light Affects Attendance Behavior of Little Penguins." Journal of Biological Rhythms 31:194-204.

Saraux, Claire; Chiaradia, Andre; Salton, Marcus; Dann, Peter; Viblanc, Vincent A (2016). "Negative effects of wind speed on individual foraging performance and breeding success in little penguins". Ecological Monographs. 86 (1): 61–77.

Simpson, G. G. 1946. Fossil Penguins. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 87(1):1-100.

Tennyson, A. J. D., and P. R. Millener. 1994. Bird extinctions and fossil bones from Mangere Island, Chatham Islands. Notornis, Supplement 41:165-178.

Tennyson, A. J. D., J. H. Cooper, and L. D. Shepherd. 2015. A new species of extinct Pterodroma petrel (Procellariiformes: Procellariidae) from the Chatham Islands, New Zealand. Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club 135:267-277.

van Tets, G. F., and S. O'Connor. 1983. The Hunter Island Penguin, and extinct new genus and species form a Tasmanian midden. Records of the Queen Victoria Museum, Launceston 81:1-13.

Wallis, Robert; King, Kristie; Wallis, Anne (2017). "The Little Penguin'Eudyptula minor'on Middle Island, Warrnambool, Victoria: An update on population size and predator management". Victorian Naturalist. 134 (2): 48–51.

Wiebkin, A. S. (2011) Conservation management priorities for little penguin populations in Gulf St Vincent. Report to Adelaide and Mount Lofty Ranges Natural Resources Management Board. South Australian Research and Development Institute (Aquatic Sciences), Adelaide. SARDI Publication No. F2011/000188-1. SARDI Research Report Series No.588. 97pp.

Williams, Tony D. (1995). The Penguins. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Williams, M., A. J. D. Tennyson, and D. Sim. 2014. Island differentiation of New Zealand’s extinct mergansers (Anatidae: Mergini), with description of a new species from Chatham Island. Wildfowl 6:3-34.

Wood, J. R., K. J. Mitchell, R. P. Scofield, A. J. D. Tennyson, A. E. Fidler, J. M. Wilmshurst, B. Llamas and A. Cooper. 2014. An extinct nestorid parrot (Aves, Psittaciformes, Nestoridae) from the Chatham Islands, New Zealand. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 172:185-199.

Worthy, T. H. 1998. A remarkable fossil and archaeological avifauna from Marfells Beach, Lake Grassmere, South Island, New Zealand. Records of the Canterbury Museum 12:79-176.

Worthy, T. H., and J. A. Grant-Mackie. 2003. Late-Pleistocene avifaunas from Cape Wanbrow, Otago, South Island, New Zealand. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand 33(1):427-485.

#Eudyptula minor#Eudyptula#Penguin#Little Penguin#Dinosaur#Dinosaurs#Bird#Birds#Birblr#Palaeoblr#Factfile#Little Blue Penguin#Fairy Penguin#Aequorlitornithian#Ardeaen#Piscivore#Water Wednesday#Quaternary#Australia & Oceania#Blue Penguin#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

231 notes

·

View notes

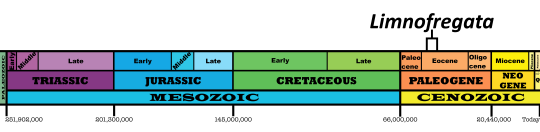

Text

Gavia

Common Loon by Amy Widenhofer, CC BY-SA 2.0

Etymology: Unidentified Sea Bird

First Described By: Coues, 1903

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Aequorlitornithes, Ardeae, Aequornithes, Gaviiformes, Gaviidae

Referred Species: G. egeriana, G. schultzi, G. brodkorbi, G. moldavica, G. paradoxa, G. concinna, G. fortis, G. palaeodytes, G. howardae, G. concinna, G. stellata (Red-Throated Loon), G. arctica (Black-Throated Loon), G. pacifica (Pacific Loon), G. immer (Common Loon), G. adamsii (Yellow-Billed Loon)

Status: Extinct - Extant, Near Threatened - Least Concern

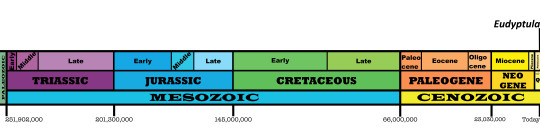

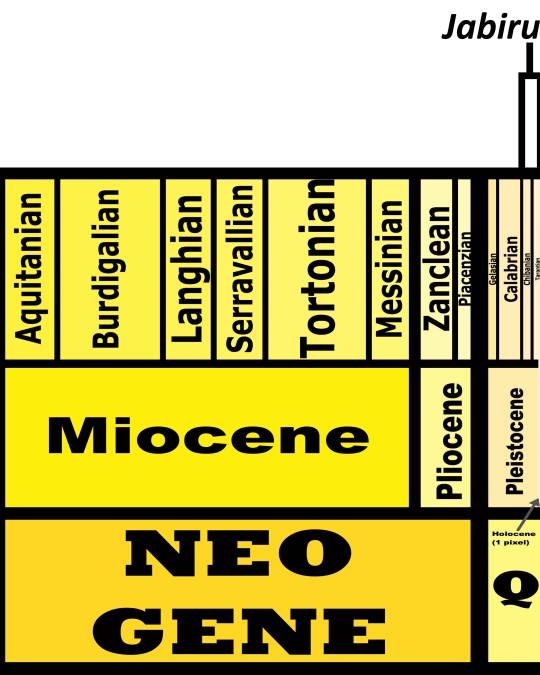

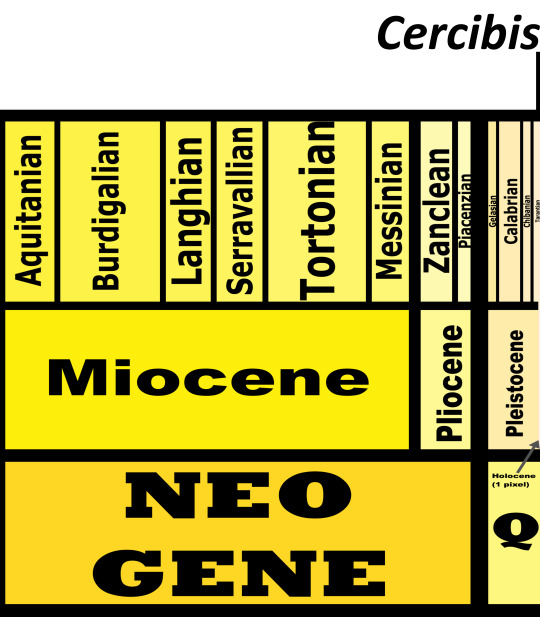

Time and Place: Since 18 million years ago, from the Burdigalian of the Miocene of the Neogene until the Holocene of the Quaternary

Loons have lived throughout the Northern Hemisphere, originating on the Eastern Coast of North America and spreading from there through the Neogene until today

Physical Description: Loons are squat birds, with long bodies and tiny little legs, and very short tails. They also have long necks, with round heads and long pointed beaks. They also have small, beady red eyes. The different species of loon differ greatly on color, though there are some common themes. Their backs are darker, usually black, with white streaks; they often have white bellies that may have some black speckles. They have distinctive black and white striping on the neck - though the extent of the striping varies from species to species, with some Loons having stripes all along the neck, and others only in isolated patches, surrounded by black feathers. The heads are usually a dark color, black or grey, with some lightness more towards the top of the head. They have black feet and flippers attached to their weird lopsided legs. In a lot of ways, Loons are modern, toothless Hesperornithines in general appearance and lopsidedness. They range from 53 to 91 centimeters in length - with many sizes in between.

Red-Throated Loon by the Bureau of Land Management, in the Public Domain

Diet: Loons primarily feed on fish, though they will occasionally supplement their diet with other small aquatic animals.

Black-Throated Loon by Bengt Nyman, CC BY 2.0

Behavior: Loons are diving birds, spending most of their time going back and forth in the water searching for food. They will engage in pursuit dives, diving many meters under the water for sources of food, and chasing their fish very vigorously in order to catch them. In some of the better known species, food will be gathered up in ponds and inshore waters and brought back to the young; in the ocean, they’ll join mixed-species flocks in order to gather more fish from the water. Spawns of new fish and crustaceans will often attract groups of Loons to new feeding locations. They tend to swallow gastroliths to aid in crushing hard parts of food in the stomach of the Loons, though they may also aid in causing reguritation when needed Loons are excessively loud during the breeding season and much quieter when hunting; the males will make loud “arroarroarro” and other cackling calls when fighting over territory, which the females often match. The Common Loon especially makes a very distinctive breeding sound, going “ooo-aaaa-eeeeeeeee” and other rising vowel sounds. While nesting, they’ll also make rising, higher-pitched “week-week-week” calls, depending on the species. But, when not breeding, they are fairly silent birds all things considered.

Pacific Loon by Tim Bowman, in the Public Domain

Loons breed mainly in the warmer summertime months, which of course varies extensively based on habitat and location - some loons begin breeding as late as June, while others start as soon as March. It really depends on how quickly the spring begins to thaw to allow for appropriate nesting time. They make nests out of heaps of plant matter placed near the water, laying between one two three eggs into the nest (though usually it’s just two, no more no less). The incubation period lasts for about a month, and the chicks are usually balls of fluffy brownish-grey down. They take around another two months to fledge, depending somewhat on their parents for food during this time. They usually take about two years to reach sexual maturity, and can live for at least a couple of decades (if not longer). Both parents usually take care of the young and will work together to move the nest if needed due to rising water levels.

Common Loon by Mike’s Birds, CC BY-SA 2.0

Loons are fairly strong fliers, though they do have trouble taking off and many have to run along the water surface while flapping wings in order to take flight - only the Red-Throated Loon can take off from land. IN the air, they can fly for long periods of time in order to migrate. Loons have extensive migration ranges, going from warmer coastal waters in the summer to their breeding sites in more northern locations in the winter. They are also extremely strong swimmers. In general, they really aren’t good at walking - the downside of their funkily-placed little legs!

Red-Throated Loon by Don Faulkner, CC BY-SA 2.0

Ecosystem: Loons mainly live in aquatic habitats - in freshwater pools, ponds, and lakes in cold locations such as tundra and taiga habitat; they will also be found on the Arctic and northern Atlantic/Pacific coasts and in rivers and estuaries along those coasts. They especially prefer to stay along the coasts and in sheltered bays during the wintertime, when it is more dangerous to be out on the open waters. They try to stay to deeper freshwater lakes and ponds when in freshwater habitats, rather than more shallow aquatic locations.

Pacific Loon by the NBII, in the Public Domain

Other: Loons are primarily doing fine, conservation wise; only one species is considered Near Threatened, the Yellow-Billed Loon. This species is suffering due to unsustainable fish harvesting, leading to dramatic population declines in recent years. They are also vulnerable to oil-spills and heavy-metal poisoning. These risks also apply to the other Loon species, they just aren’t as heavily hit by them.

Yellow-Billed Loon by Ryan Askren, in the Public Domain

Species Differences: The oldest definite members of Gavia are known from the early-middle Miocene of the Eastern United States. However, loons in general evolved possibly in the Late Cretaceous, at least by the start of the Cenozoic. There are potential members of Gavia as early as the Eocene. This indicates that Loons evolved fairly rapidly in direct response to vacant niches after the mass extinctions of the time. Other fossil species of Loon include G. egeriana from the Early Miocene of the United States and potentially Czechoslovakia; G. schultzi from the Middle Miocene of Austria; G. brodkorbi from the Late Miocene of the United States; G. moldavica from the Late Miocene of Moldova, G. paradoxa from the Late Miocene of the Ukraine, G. concinna from the Late Miocene and Early Pliocene of the United States, G. fortis from the Early Pliocene of the United States, G. palaeodytes from the Early Pliocene of the United States, G. howardae from the Early Pliocene of the United States, and G. concinna from the late Pliocene of San Diego. This showcases how Loons were much more widely distributed for much of their history, found in more southerly locations during the Neogene and up until the Ice Age.

Red-Throated Loon by Ómar Runólfsson, CC BY 2.0

Today, there are five living Loons, with distinctly different appearances and slightly different ranges. Red-Throated Loons spend their summers in the Arctic Ocean area - so along the northern parts of Russia, Canada, and around Greenland, Alaska, and Scandinavia. They will spend their winters along the coasts of both the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. They are some of the smallest loons, and also the most lightly colored - they have brown plumage and red patches on the front of their necks, and their heads and necks are primarily grey.

Black-Throated Loon by Robert Bergman, in the Public Domain

Black-Throated Loons have similar ranges to the Red-Throated Loons, but only in Eurasia - they are rarely found in North America, only some parts of Alaska. They are also somewhat smaller, but they are black in color over most of their body with distinctive white patches. The tops of their necks and heads are grey, while they have black patches on their throats and black and white striping across their necks.

Pacific Loon by Alan Vernon, CC BY 2.0

The Pacific Loon is found more in North America than in Eurasia, occasionally reaching Northeastern Russia and wintering in Japan and Korea. They also winter along the pacific coast of North America. They are the smallest of all Loons, and look very similar to Black-Throated Loons except for their size and having nrounded heads and thinner bills.

Common Loon by John Picken, CC BY 2.0

Common Loons live throughout the Northernmost part of North America, even extending somewhat into the Continental US; they also will winter along the coasts of North America. They can be found in Greenland and Western Europe, as well as Scandinavia, during the winter; they also congregate in Iceland during the winter. They are larger loons, and don’t have as much striping on their necks; their backs are also in a funky black and white checkerboard pattern.

Yellow-Billed Loon by Norbert Potensky, CC BY-SA 3.0

Finally, the Yellow-Billed Loon - unlike all other loons - have yellow bilsl, instead of grey ones. They have a similar range to the Red-Throated Loon, though somewhat more limited. They also grow extensively large, and have somewhat larger stripe patches on their necks than Common Loons - though not as much as other Loon species.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources Under the Cut

Appleby, R.H.; Steve C. Madge; Mullarney, Killian (1986). "Identification of divers in immature and winter plumages". British Birds. 79 (8): 365–91.

Armstrong, Edward A. (1970) [1958]. The Folklore of Birds. New York, NY: Dover Publications.

Arnott, W.G. (1964). "Notes on Gavia and Mergvs in Latin Authors". Classical Quarterly. New Series. 14 (2): 249–62.

Bird, Louis; Brown, Jennifer S.H. (2005). Telling Our Stories: Omushkego Legends and Histories from Hudson Bay. Peterborough, ON, Canada: Broadview Press.

Brodkorb, P. 1953. A review of the Pliocene loons. Condor 55(4):211-214

Brodkorb, P. 1955. The avifauna of the Bone Valley Formation. Florida Geological Survey Report of Investigations 14:1-57

Brodkorb, Pierce (1963). "Catalogue of fossil birds. Part 1 (Archaeopterygiformes through Ardeiformes)". Bulletin of the Florida State Museum, Biological Sciences. 7 (4): 179–293.

Broughton, J. M. 2004. Prehistoric human impacts on California birds: evidence from the Emeryville shellmoumd avifauna. Ornithological Monographs 56:1-90

Carboneras, Carles (1992). "Family Gaviidae (Divers)". In Josep del Hoyo; Andrew Elliott; Jordi Sargatal (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World, Volume 1: Ostrich to Ducks. Barcelona, Spain: Lynx Edicions.

Carboneras, C. & Garcia, E.F.J. (2019). Arctic Loon (Gavia arctica). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Carboneras, C., Christie, D.A. & Garcia, E.F.J. (2019). Common Loon (Gavia immer). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Carboneras, C., Christie, D.A. & Garcia, E.F.J. (2019). Red-throated Loon (Gavia stellata). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Carboneras, C., Christie, D.A. & Garcia, E.F.J. (2019). Yellow-billed Loon (Gavia adamsii). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Carroll, R. L. 1988. Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution 1-698

Cassidy, Frederic Gomes; Hall, Joan Houston (1985). Dictionary of American Regional English: Volume1, A–C. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Chandler, R. M. 1990. Fossil birds of the San Diego Formation, Late Pliocene, Blancan, San Diego County, California. Ornithological Monographs 44:73-161

Clements, J. F., T. S. Schulenberg, M. J. Iliff, D. Roberson, T. A. Fredericks, B. L. Sullivan, and C. L. Wood. 2017. The eBird/Clements checklist of birds of the world: v2017

del Hoyo, J., Collar, N. & Garcia, E.F.J. (2019). Pacific Loon (Gavia pacifica). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Evers, David C., James D. Paruk, Judith W. Mcintyre and Jack F. Barr. 2010. Common Loon (Gavia immer), The Birds of North America Online (A. Poole, Ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology

Guthrie, D. A. 1992. A late Pleistocene avifauna from San Miguel Island, California. Science Series (Los Angeles) 36:319-327

Hastings, A. K., and A. C. Dooley. 2017. Fossil-collecting from the middle Miocene Carmel Church Quarry marine ecosystem in Caroline County, Virginia. The Geological Society of America Field Guide 47:77-88

Howard, H. 1949. New avian records for the Pliocene of California. Carnegie Instuitution of California 584:179-200

Howard, H. 1972. Type specimens of avian fossils in the collections of the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. Contributions in Science 1-27

Howard, H. 1978. Late Miocene marine birds from Orange County, California. Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County Contributions in Science 290:1-26

Howard, H. 1982. Fossil birds from Tertiary marine beds at Oceanside, San Diego County, California, with discriptions of two species of the genera Uria and Cepphus (Aves: Alcidae). Contributions in Science, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County 341:1-15

Jobling, J. A. 2010. The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. Christopher Helm Publishing, A&C Black Publishers Ltd, London.

Lambrecht, K. 1933. Handbuch der Palaeornithologie. 1-1024

Linnaeus, C. 1758. Systema Naturae per Regna Tria Naturae, Secundum Classes, Ordines, Genera, Species, cum Characteribus, Differentiis, Synonymis, Locis. Editio Decima 1:1-824

Mayr, Gerald (2004). "A partial skeleton of a new fossil loon (Aves, Gaviiformes) from the early Oligocene of Germany with preserved stomach content" (PDF). J. Ornithol. 145 (4): 281–86.

Mayr, Gerald (2009). Paleogene Fossil Birds. Heidelberg/New York: Springer-Verlag.

Miller, L., and R. I. Bowman. 1958. Further bird remains from the San Diego Pliocene. Contributions in Science, Los Angeles County Museum 20:1-15

Mlíkovský, Jirí (2002). Cenozoic Birds of the World, Part 1: Europe (PDF). Prague: Ninox Press.

Mobley, Jason A. (2008). Birds of the World. Marshall Cavendish. p. 382.

Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks (Montana FW&P) (2007): Animal Field Guide: Common Loon; retrieved 2007-05-12.

Moran, Mark; Sceurman, Mark; Godfrey, Linda S. & Hendricks, Richard D. (2005): Weird Wisconsin: Your Travel Guide to Wisconsin's Local Legends and Best Kept Secrets. Sterling Publishing. ISBN 0-7607-5944-8, p. 78

Olson, Storrs L. (1985). "Section X.I. Gaviiformes" (PDF). In Farner, D.S.; King, J.R.; Parkes, Kenneth C. (eds.). Avian Biology. 8. pp. 212–14.

Olson, S. L., and P. C. Rasmussen. 2001. Miocene and Pliocene birds from the Lee Creek Mine, North Carolina. Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology 90:233-365

Parmalee, P. W. 1992. A late Pleistocene avifauna from northwestern Alabama. Science Series, Los Angeles Museum of Natural History, Science, and Art 36:307-318

Piper, W.H.; Evers, D.C.; Meyer, M.W.; Tischler, K.B. & Klich, M. (2000): Do common loons mate for life?: scientific investigation of a widespread myth. In: McIntyre, J. & Evers, D.C. (eds.): Loons: old history and new findings – proceedings of a symposium from the 1997 meeting of the American Ornithologists' Union: 43–49. North American Loon Fund, Meredith, New Hampshire.

Piper, W.H.; Tischler, K.B. & Klich, M. (2000). "Territory acquisition in loons: The importance of take-over". Animal Behaviour. 59 (2): 385–94.

Piper, W.H.; Walcott, C.; Mager, J.N.; Perala, M.; Tischler, K.B.; Harrington, Erin; Turcotte, A.J.; Schwabenlander M. & Banfield, N. (2006). "Prospecting in a Solitary Breeder: Chick Production Elicits Territorial Intrusions in Common Loons". Behavioral Ecology. 17 (6): 881–888.

Piper, W.H.; Walcott, C.; Mager, J.N. & Spilker, F. (2008). "Nestsite selection by male loons leads to sex-biased site familiarity". Journal of Animal Ecology. 77 (2): 205–10.

Piper, W.H.; Walcott, C.; Mager, J.N. & Spilker, F. (2008b). "Fatal Battles in Common Loons: A Preliminary Analysis". Animal Behaviour. 75 (3): 1109–15.

Rasmussen, Pamela C. (1998). "Early Miocene Avifauna from the Pollack Farm Site, Delaware" (PDF). Delaware Geological Survey Special Publication. 21: 149–51.

Shufeldt, R. W. 1915. Fossil birds in the Marsh Collection of Yale University. Transactions of the Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences 19:1-110

Sjölander, S. & Ågren, G. (1972). "The reproductive behaviour of the Common Loon". Wilson Bull. 84 (3): 296–308.

Sjölander, S. & Ågren, G. (1976). "The reproductive Behavior of the Yellow-billed Loon, Gavia adamsii (with G. Ågren)". The Condor. 78 (4): 454–63.

Slack, K.E.; Jones, C.M.; Ando, T.; Harrison G.L.; Fordyce R.E.; Arnason, U. & Penny, D. (2006). "Early Penguin Fossils, plus Mitochondrial Genomes, Calibrate Avian Evolution". Mol. Biol. Evol. 23 (6): 1144–55.

Stolpe, M. (1935). "Colymbus, Hesperornis, Podiceps:, ein Vergleich ihrer hinteren Extremität". J. Ornithol. (in German). 80 (1): 115–128.

Storer, Robert W. (1956). "The Fossil Loon, Colymboides minutus" (PDF). Condor. 58 (6): 413–426.

Wetmore, Alexander (1941). "An Unknown Loon from the Miocene Fossil Beds of Maryland" (PDF). Auk. 58 (4): 567.

Zelenkov, N. V., E. N. Kurochkin, A. A. Karhu and P. Ballmann. 2008. Birds of the Late Pleistocene and Holocene from the Palaeolithic Djuktai cave site of Yakutia, eastern Siberia. Oryctos 7:217-226

#Gavia#Loon#Bird#Dinosaur#Aequorlitornithian#Ardeaen#Birds#Dinosaurs#Prehistoric Life#Paleontology#Prehistory#Factfile#Birblr#Palaeoblr#Water Wednesday#Neogene#Quaternary#Piscivore#North America#Eurasia#Red-Throated Loon#Black-Throated Loon#Arctic Loon#Pacific Loon#Common Loon#Yellow-Billed Loon#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day

228 notes

·

View notes

Text

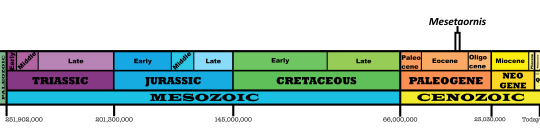

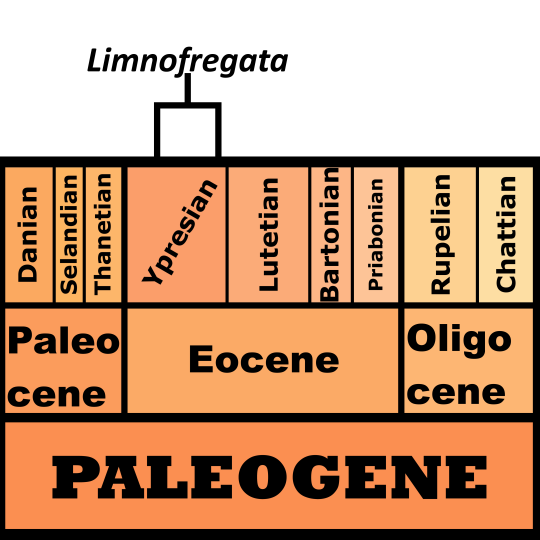

Mesetaornis polaris

By Scott Reid

Etymology: Meseta Bird

First Described By: Myrcha et al., 2002

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Aequorlitornithes, Ardeae, Aequornithes, Austrodyptornithes, Sphenisciformes, Spheniscidae

Status: Extinct

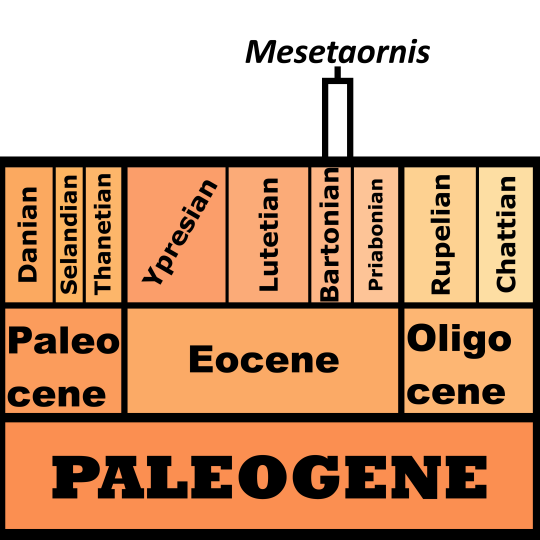

Time and Place: Between 40 and 38 million years ago, in the Bartonian age of the Eocene of the Paleogene

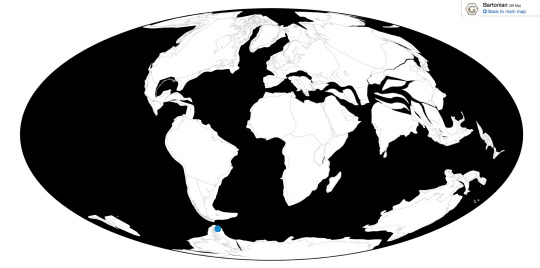

Mesetaornis is known from the Telm 7 member of the La Meseta Formation on Seymour Island, Antarctica

Physical Description: Mesetaornis is one of our early penguins - those long-billed weirdos of the first half of the Cenozoic, which paved the way for the adorable friends we known from the Southern Hemisphere today. It had extremely long toes compared to other penguins, and actually had the fourth toe (hallux), giving it very weird feet compared to its relatives. A small early penguin, it was much smaller than such species as Palaeeudyptes and Anthropornis, while probably around the same size as Delphinornis. This means it probably wouldn’t have reached taller than 70 or so centimeters in height (as a very rough estimate). Of course, this is just conjecture, as all we have of it are toe bones. Like other penguins, it would have stood upright, waddled about, and been more adept to life in the water than on land.

Diet: As in other penguins, Mesetaornis would have primarily fed upon fish and other aquatic organisms.

Behavior: Mesetaornis probably behaved like other penguins, spending most of its time near the water and diving about for food. Being closer to living penguins than earlier forms, it was probably not as good in the water as those today, but still better than those who came before. It could dive and fly through the water to some extent, using its flipper-wings to do so; it would have also been very awkward on land. As a penguin, Mesetaornis would have probably lived in large flocks, and taken care of its young with the help of others in the group.

By Ripley Cook

Ecosystem: Mesetaornis lived in a subtropical coast, right off the edge of Antarctica, which was teeming with life unique to the area while the rest of the world was covered in a (slowly receding) jungle. Instead, this coast would have been rocky and cooler, surrounding a system of estuaries and bays with plants such as magnolias and ferns populating the shores. This would have been an extremely fertile environment for penguins, and it shows in the fossil record! There were plenty of bivalves, gastropods, cephalopods, sharks, and fish, as well as a variety of turtles. There were mammals there, too, including small rodent ones and larger, more bulky forms. As for other dinosaurs, there were Pseudotoothed Birds, early Petrels, flamingo-ducks, and a truly hopeless number of penguins - including Delphinornis, Palaeeudyptes, Marambiornis, Anthropornis, and Archaeospheniscus - making this the place to go to see the early evolution of penguins!

Other: Mesetaornis is a very early derived penguin, grouped up with other early penguins like Delphinornis and Marambiornis. These were full penguins, not quite as weirdly loon-shaped as earlier forms like Waimanu, but they weren’t as big as later forms or had the same beak as living penguins. As such, it represents one of many early penguins that showcase the evolution of the group - and Mesetaornis was a weird one, since it had freakishly long toes!

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources Under the Cut

Chavez, M. 2007. Fossil birds of Chile and Antarctic Peninsula. Arquivos do Museo Nacional, Rio de Janeiro 65(4):551-572

Cione, A. L., and M. A. Reguero. 1994. New records of the sharks Isurus and Hexanchus from the Eocene of Seymour Island, Antarctica. Proceedings of the Geologists' Association 105:1-14

Hospitaleche, C.A., Reguero, M. and Santillana, S., 2017. Aprosdokitos mikrotero gen. et sp. nov., the tiniest Sphenisciformes that lived in Antarctica during the Paleogene. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie-Abhandlungen, 283(1), pp.25-34.

Jadwiszczak, P. 2006. Eocene penguins of Seymour Island, Antarctica: Taxonomy. Polish Polar Research 27(1):3-62

Jadwiszczak, P., 2008. Short Note: An intriguing penguin bone from the Late Eocene of Seymour Island, Antarctic Peninsula. Antarctic Science, 20(6), pp.589-590.

Jadwiszczak, P. and Gaździcki, A., 2014. First report on hind-toe development in Eocene Antarctic penguins. Antarctic Science, 26(3), pp.279-280.

Ksepka, D. T., S. Bertelli, and N. P. Giannini. 2006. The phylogeny of the living and fossil Sphenisciformes (penguins). Cladistics 22:412-441

Ksepka, D.T. and Ando, T., 2011. Penguins past, present, and future: trends in the evolution of the Sphenisciformes. Living Dinosaurs, pp.155-186.

Mayr, G. 2009. Paleogene Fossil Birds. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg.

Mayr, G. 2017. Avian Evolution: The Fossil Record of Birds and its Paleobiological Significance. Topics in Paleobiology, Wiley Blackwell. West Sussex.

Mayr, G., De Pietri, V.L. and Scofield, R.P., 2017. A new fossil from the mid-Paleocene of New Zealand reveals an unexpected diversity of world’s oldest penguins. The Science of Nature, 104(3-4), p.9.

Myrcha, A., P. Jadwiszczak, C. P. Tambussi, J. I. Noriega, A. Gazdzicki, A. Tatur, and R. A. Valle. 2002. Taxonomic revision of Eocene Antarctic penguins based on tarsometatarsal morphology. Polish Polar Research 23(1):5-46

Reguero, M. A., S. A. Marenssi, and S. N. Santillana. 2012. Weddellian marine/coastal vertebrates diversity from a basal horizon (Ypresian, Eocene) of the Cucullaea I Allomember, La Meseta formation, Seymour (Marambio) Island, Antarctica. 19(3):275-284

Stilwell, J. D., and W. J. Zinsmeister. 1992. Molluscan Systematics and Biostratigraphy. Antarctic Research Series, AGU 55

Woodburne, M. O., and W. J. Zinmeister. 1982. Fossil Land Mammal from Antarctica. Science 218:284-286

#Mesetaornis polaris#Mesetaornis#Penguin#Dinosaur#Bird#Birblr#Palaeoblr#Factfile#Dinosaurs#Ardeaen#Aequorlitornithian#Water Wednesday#Paleogene#Antarctica#Piscivore

132 notes

·

View notes

Text

Xenerodiops mycter

By Ripley Cook

Etymology: The strangely appearing Heron

First Described By: Rasmussen et al., 1987

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Aequorlitornithes, Ardeae, Aequornithes, Pelecaniformes

Status: Extinct

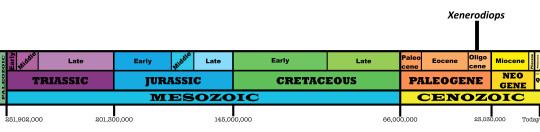

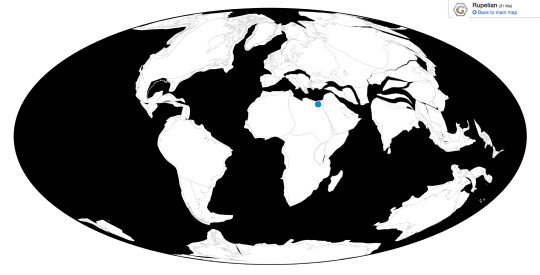

Time and Place: Between 30.2 and 29.5 million years ago, in the Rupelian of the Oligocene

Xenerodiops is known from the Jebel Qatrani Formation of Egypt

Physical Description: Xenerodiops is a strange intermediate bird, slightly smaller than the smallest living stork - probably no longer than 70 centimeters or so. Still, it was larger than most living species of herons - so this wasn’t a small bird. It was fairly similar to storks too, in terms of the shapes of the known bones, so it seems likely that Xenerodiops was a precursor to that modern dinosaur group. It had a very strong, pointed bill, though, more like herons than storks - adapted for biting and even stabbing prey, rather than snapping up food trapped in vegetation. This weirdly short, heavy bill was also curved downwards, so different from living herons and somewhat similar to living storks. Its wings were heavy and robust, and in general, this was a very sturdy sort of bird.

Diet: Xenerodiops probably fed on animals and, if it is a heron-stork like thing as supposed, it is logical to assume these animals were found in bodies of water.

Behavior: Without more fossils of Xenerodiops, it is difficult to piece together how it would have looked - especially without legs, which would point to whether or not this bird waded in the water as those birds it seems to be closely related to do. Still, for now, that is the simplest explanation for its general lifestyle. Its large beak would have been useful in reaching out into bodies of water and grabbing food sharply, possibly even stabbing it; being curved downwards, it could have been used similar to living stork bills in probing for food in the water. It is possible, then, that Xenerodiops did similar things, going into the water and grabbing as much food with its strong beak as possible, sensing food where it could not see. With its strong, robust wings, Xenerodiops would have been a powerful flier, able to gain a lot of movement from very few flaps of their wings. As with other dinosaurs, Xenerodiops would have probably taken care of its young; whether or not it did so in large colonies or in isolated nests is difficult to tell at this point.

Creatures of the Jebel Qatrani by Stanton F. Fink, CC By-SA 2.5

Ecosystem: The Jebel Qatrani Formation is a fairly famous ecosystem from the Oligocene, a time when the weird creatures of the Eocene and Paleocene were beginning to transition into animals similar to those we see today. In addition to almost-modern forms, of course, there were also the fun offshoots, which is probably where Xenerodiops lies. Jebel Qatrani is famous for its transitional fossils, especially among mammals. It was a thick swamp ecosystem, extremely warm and wet - a tropical wetland, filled with animals taking advantage of the lush plantlife. This place was filled with a variety of mammals - dugong relatives like Eosiren, a transitional primate Aegyptopithecus, a weird pointy heavyset mammal Arsinoitherium, the slightly more hippo-esque but still weird Bothriogenys, giant hyraxes, the lemur-like Plesiopithecus, the false ungulate Herodotius, the strange carnivores Ptolemaia and Qarunavus, a marsupial Peratherium, hyaenodonts like Metapterodon, and an alarming number of rodents. Turtles and crocodilians and other reptiles were plentiful too, like the turtle Albertwoodemys, the crocodile Crocodylus megarhinus, a gharial Eogavialis, and the snake Pterosphenus. As for fish, there were a variety of tetras, snakeheads, and catfish.

Xenerodiops wasn’t the only dinosaur in this environment, either. Many other weird birds were found here, some just as odd and unplaceable as Xenerodiops. For example, Eremopezus lived here - it was some sort of large, flightless bird. Beyond that, we have no idea. There was also the (iconic and large) swimming flamingo, Palaelodus. An even larger sort of shoebill than the living one, Goliathia, prowled the swamps. A giant true stork, Palaeoephippiorhynchus, was a major fixture of the landscape. There were Jacanas like Nuphranassa and Janipes, turacos like Crinifer, and even birds of prey. In a lot of ways, therefore, the birds of the area were even weirder than the mammals - and Xenerodiops was just one of many.

By José Carlos Cortés

Other: What exactly Xenerodiops is remains a mystery. Its weird combination of characteristics points to it being in the group of dinosaurs including a large number of living water birds - and both storks and herons. However, research has shown that storks and herons are actually somewhat removed from each other, with herons being more closely related to pelicans, shoebills, ibises, and even boobies than to storks. Is Xenerodiops, then, a weird, transitional, extinct member of this group of dinosaurs? Is it another evolutionary experiment altogether, with traits of many members of this group? Something else entirely? Only more fossils will help us to make the picture clearer. Some of these traits are shared in other weird waterbirds of the Paleogene (such as Mangystania), and it is entirely possible that there is an extinct clade of these animals, separate from all living members of the group.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Mayr, G. 2009. Paleogene Fossil Birds. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg.

Mayr, G. 2017. Avian Evolution: The Fossil Record of Birds and its Paleobiological Significance. Topics in Paleobiology, Wiley Blackwell. West Sussex.

Mlíkovský, Jiří (2003), "Early Miocene Birds of Djebel Zelten, Libya" (PDF), Časopis Národního muzea, Řada přírodovědná, 172 (1–4): 114–120.

Rasmussen, D. T., S. L. Olson, E. L. Simons. 1987. Fossil Birds from the Oligocene Jebel Qatrani Formation Fayum Province, Egypt. Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology 62: 1 - 19.

Zvonov, E. A., N. V. Zelenkov, I. G. Danilov. 2015. A New unusual waterbird (Aves, ?Suliformes) from the Eocene of Kazakhstan. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology: e1035783.

#Xenerodiops mycter#Xenerodiops#Dinosaur#Aequorlitornithian#Bird#Birds#Ardeaen#Factfile#Dinosaurs#Birblr#Palaeoblr#Carnivore#Water Wednesday#Africa#Paleogene#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

219 notes

·

View notes

Text

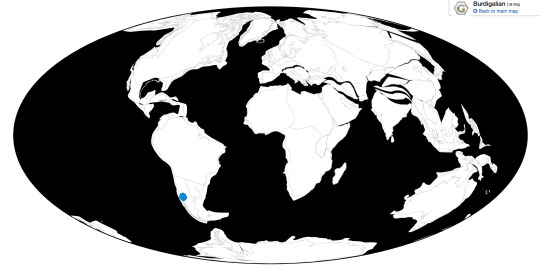

Jabiru mycteria

By Andreas Trepte, CC BY-SA 4.0

Etymology: Tupí for Very Big Bird

First Described By: Hellmayr, 1906

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Aequorlitornithes, Ardeae, Aequornithes, Ciconiiformes

Status: Extant, Least Concern

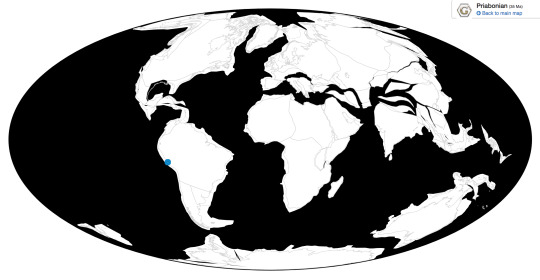

Time and Place: From 126,000 years ago until the present, from the Tarantian of the Pleistocene to the Holocene

Jabiru are primarily known from the Amazon basin, though during the Ice Age they were much more widespread (shown in light blue)

Physical Description: Jabiru are extremely large storks, primarily white in color all over their bodies and wings. They have very long, skinny black legs, like other storks, and black heads. Their heads are ridiculously long, with beaks that make up three-forths of the entire head – these beaks are long, triangular, and pointed. Underneath the black neck, they have red throat sacks which stand out from the rest of the body. Males differ from females in having longer beaks and more vibrant red color on their throat sacks; the juveniles, meanwhile, are more grey than the adults. Babies of this species are especially fat and fluffy, and covered in white feathers. In terms of size, Jabiru are the tallest flying birds in Latin America, reaching the same height as the flightless rhea – up to 1.53 meters tall. So, you know, about the same height as a shorter person. They grow between 1.2 and 1.4 meters long in general, from head to tail; they have some of the largest wingspans of any South American bird, reaching between 2.3 and 2.6 meters long – only the Andean Condor has a larger wingspan on that continent. The beaks can range between 25 and 35 centimeters. In short, though Jabiru can honestly look really gangly and ridiculous, they are also absolutely, terrifyingly, huge.

By Charles J. Sharp, CC BY-SA 4.0

Diet: Jabiru feed on fish, frogs, snakes, insects, baby crocodilians, and turtles – though the bulk is fish, they really can’t be classified as anything other than a carnivore.

By Lukja, CC BY-SA 3.0

Behavior: Jabiru will wade in the shallows of the water, splashing their bills into it to disturb prey. They will look for prey mainly by feeling around with their beaks, but they also see the food and reach out to grab it. THey then carry the food to the shore and dismantle it there, where it can’t as easily slip out (especially in the case of fish). They’ll also use sounds – baby caimans, especially, are found by listening for their distress calls. They tend to feed in large groups of up to fifty birds during the dry season, congregating where food can be found; in the west season, they are more solitary. They do associate with other storks and ibises as well during feeding. They are very silent away from the nest, stalking in the quiet; they will make very loud bill claps when alarmed, and make soft coughs and bill claps during copulation and nest displays. Their pouches are inflated during mating displace, and also as a threat to other members of species when they feel their spaces is being invaded.

By Charles J. Sharp, CC BY-SA 4.0

Despite being ridiculously huge and a little silly looking on the ground, Jabiru are amazingly graceful fliers, soaring above the ground with the agility of the Andean Condor – which it rivals in size. They don’t migrate much, but congregate in small groups with other storks and ibises and moving in relation to rainfall. They will fly to seek out new places of food. Breeding varies from location to location, usually at the end of the dry season and the start of the wet season. They usually nest alone, but they will form groups of up to six nests – though some populations breed in mixed colonies with other storks. They make nests in tall palm trees, so if you needed to imagine a person-sized bird nesting in a tree, here you go. They sometimes nest in tall mangroves or other types of trees in pine savanna. The nests are made of sticks and mud and are used year to year. Three to four eggs are laid per season, and the young hatch white and fluffy and dependent on the parents. Both parents will incubate the eggs. The babies leave the nest after about a hundred days, though the young stick with the parents for another three months. As such, most mated pairs alternate breeding years. The pairs mate for life as well. Jabiru can live on average for thirty-six years.

By Charles J. Sharp, CC BY-SA 4.0

Ecosystem: Jabiru live in large freshwater marshes, pine-savanna, ranches near ponds and lagoons, near large rivers and lakes, in estuaries, and rice fields. The young are specially preyed upon by raccoons, other storks, and humans; but healthy adults have no known predators.

By Andreas Trepte, CC BY-SA 4.0

Other: Though the Jabiru stork already has a very large range today, fossil evidence indicates that during the last glacial maximum its range was even larger, extending up into North America. It is thus possible that climate change following the end of the last Ice Age lead to a decline in Jabiru populations and a decrease in Jabiru range. That being said, Jabiru today are doing perfectly fine in terms of conservation and population – they are considered threatened with extinction, and therea re considered to be tens of thousands of birds worldwide. Still, Central American populations of Jabiru are on the decline possibly as a continuation of the elimination of this bird from North America in general; in the Amazon, the chicks are considered a source of food by native populations.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Allen, G. M. 1932. A Pleistocene bat from Florida. Journal of Mammalogy 13(3):256-259

Campbell, K. E. 1979. The non-passerine Pleistocene avifauna of the Talara Tar Seeps, northwestern Peru. Royal Ontario Museum Life Sciences Contribution 118:1-203

Clements, J. F., T. S. Schulenberg, M. J. Iliff, D. Roberson, T. A. Fredericks, B. L. Sullivan, and C. L. Wood. 2017. The eBird/Clements checklist of birds of the world: v2017

Elliott, A., Garcia, E.F.J., Kirwan, G.M. & Boesman, P. (2019). Jabiru (Jabiru mycteria). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Hancock, Kushan. 1992. Storks, Ibises, and Spoonbills of the World. Princeton University Press.

Sellards, E. H. 1916. Human remains and associated fossils from the Pleistocene of Florida. Florida Geological Survey Annual Report 8:120-160

Shufeldt, R. W. 1917. Fossil birds found at Vero, Florida. Florida State Geological Survey Annual Report 9:35-42

Simpson, G. G. 1929. Pleistocene mammalian fauna of the Seminole Field, Pinellas County, Florida. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 56(8):561-599

Walsh, S. A.; Sánchez, R. 2008. The first Cenozoic fossil bird from Venezuela. Paläontologische Zeitschrift. 82 (2): 105–112.

#Jabiru mycteria#Jabiru#Stork#Dinosaur#Bird#Birds#Birblr#Palaeoblr#Dinosaurs#Ardeaen#Aequorlitornithian#Quaternary#North America#South America#Carnivore#Water Wednesday#factfile#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

147 notes

·

View notes

Text

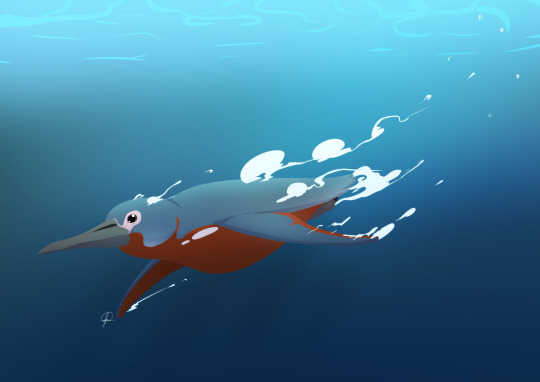

Inkayacu paracasensis

By José Carlos Cortés

Etymology: King of the Water

First Described By: Clarke et al., 2010

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Aequorlitornithes, Ardeae, Aequornithes, Austrodyptornithes, Sphenisciformes, Spheniscidae

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: Between 37.2 and 33.9 million years ago, in the Priabonian age of the Eocene of the Paleogene

Inkayacu is known from Yumaque Point of the Otuma Formation in Ica, Peru

Physical Description: Inkayacu was an extinct penguin, and had a lot of similar traits to other extinct penguins - though resembling modern forms, extinct ones were unique in having extremely large bill size and just large body size in general. Inkayacu was about 1.5 meters long, which is a significant jump from the biggest living penguin (the Emperor Penguin at 1.2 meters long), and Inkayacu wasn’t even the biggest penguin at the time. It had a long, pointed bill, much longer than those seen on living members of the group. And - uniquely - we know the color of Inkayacu! Unlike living penguins, which are all varying shades of black and white with some splashes of other colors elsewhere, Inkayacu was grey and brown. We only known these colors form the flippers (wings), which show grey backs of the flipper and brown fronts, but it’s reasonable to suppose this pattern would follow the patterns of living penguins, where the color of the back of the flipper extends throughout the back of the animal, and the color of the front extends to the front. Thus, we depict Inkayacu with a grey back and a brown front, but this is still a conjecture. The melanosomes are similar to modern birds, long and narrow within the feathers - living penguins actually have wider ones. Other than that, the feathers of Inkayacu are similar to modern penguins in other ways, indicating that it had the same aquatic lifestyle. As such, it was flightless.

Diet: Inkayacu, like other penguins, would have fed on a wide variety of fish and aquatic invertebrates.

Icadyptes and Inkayacu by Apokryltaros, CC BY-SA 3.0

Behavior: Though shaped in a lot of ways like living penguins, Inkayacu was different in a number of ways. It had fewer melanosomes in its feathers than living penguins - and these melanosomes provide rigidity in modern penguin feathers that help with deep-sea diving. Without such melanosomes, Inkayacu might not have been as well adapted to deep diving. Still, it was clearly adapted for spending its life in the sea, diving and sea-flying all over its habitat. It would have used its long beak to stab and grab food, especially slippery food that might be hard to get a grip on. Using its flippers, it could propel itself through the water. Its feet were small and not good for moving, so on land it would probably waddle. This is not an uncommon bird to find, fossil-wise, and so it stands to reason that it would have been very social like living penguins. It would have probably laid its eggs on land, and took care of its young with mated partners. Given it lived in Peru, in the Eocene, it was more adapted for warm weather than cold, and wouldn’t have ventured very far south.

By Julio Lacerda, used with permission from Earth Archives

Ecosystem: Inkayacu lived along the Pervuian Priabonian coast, the Western coast of South America right as the global rainforest of the Eocene was collapsing and being replaced with more varying and arid climates. This was also a time of notable climate change and effects on the ocean, leading to a small mass extinction (especially in the oceans) at this time - killing off many iconic forms, including proto-whales. The conditions of this mass extinction actually allowed the penguins to flourish, and Inkayacu was a part of that flourishing. Inkayacu lived alongside proto-whales like Cynthiacetus and Mystacodon - a toothed baleen whale. Inkayacu wasn’t the only penguin in this area, but was joined by the larger and longer-beaked Icadyptes. As for proper fish, there were ray-finned fish like Engraulis and Sardinops, and unnamed sharks. There may have also been the marine snake Pterosphenus. There were many kinds of invertebrates as well. Inkayacu would probably have had to look out for the sharks and whales, though the fish would have had to look out for it! The coast that Inkayacu would have spent its time on would probably have been more rocky than sandy, though it’s uncertain either way.

By Ripley Cook

Other: Inkayacu is very closely related to living penguins and is just outside the group of modern penguins and their closest relatives, so it showcases the evolution of penguins towards what we’re familiar with today. It’s interesting to note that short beaks seem to be characteristic of the modern crown group of penguins, and that long beaks were found in penguins even as close to the crown group as Inkayacu.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Acosta Hospitaleche, C., and M. Stucchi. 2005. Nuevos restos terciarios de Spheniscidae (Aves, sphenisciformes) procedentes de la Costa del Peru. Revista española de paleontología 20(1):1-5

Clarke, J.A.; Ksepka, D.T.; Stucchi, M.; Urbina, M.; Giannini, N.; Bertelli, S.; Narváez, Y.; Boyd, C.A. (2007). "Paleogene equatorial penguins challenge the proposed relationship between biogeography, diversity, and Cenozoic climate change". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 104 (28): 11545–11550.

Clarke, J. A., D. T. Ksepka, R. Salas-Gismondi, A. J. Altamirano, M. D. Shawkey, L. D’Alba, J. Vinther, T. J. DeVries, and P. Baby. 2010. Fossil evidence for evolution of the shape and color of penguin feathers. Science 330

Hoffstetter, R. 1958. Un serpent marin du genre Pterosphenus (Pt. Sheppardi nov. sp.) dans L’Éocène supérieur de L’Équateur (Amérique de Sud). Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France 6:45-50

Hooker, J.J.; Collinson, M.E.; Sille, N.P. (2004). "Eocene-Oligocene mammalian faunal turnover in the Hampshire Basin, UK: calibration to the global time scale and the major cooling event". Journal of the Geological Society. 161 (2): 161–172.

Ivany, Linda C.; Patterson, William P.; Lohmann, Kyger C. (2000). "Cooler winters as a possible cause of mass extinctions at the Eocene/Oligocene boundary". Nature. 407 (6806): 887–890.

Köhler, M; Moyà-Solà, S (December 1999). "A finding of oligocene primates on the European continent". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 96 (25): 14664–7.

Li, Y. X.; Jiao, W. J.; Liu, Z. H.; Jin, J. H.; Wang, D. H.; He, Y. X.; Quan, C. (2016-02-11). "Terrestrial responses of low-latitude Asia to the Eocene–Oligocene climate transition revealed by integrated chronostratigraphy". Clim. Past. 12 (2): 255–272.

Marocco, R., and C. d.e. Muizon. 1988. Los vertebrados del Neogeno de La Costa Sur del Perú: Ambiente sedimentario y condiciones de fosilización. Bulletin de l'Institut Frances d'Etudes Andines 17(2):105-117

Martinez-Cacers, M., and C. de Muizon. 2011. A toothed mysticete from the Middle Eocene to Lower Oligocene of the Pisco Basin, Peru: new data on the origin and feeding evolution of Mysticeti. Sixth Triennial Conference on Secondary Adaptation of Tetrapods to Life in Water 56-57

Molina, Eustoquio; Gonzalvo, Concepción; Ortiz, Silvia; Cruz, Luis E. (2006-02-28). "Foraminiferal turnover across the Eocene–Oligocene transition at Fuente Caldera, southern Spain: No cause–effect relationship between meteorite impacts and extinctions". Marine Micropaleontology. 58 (4): 270–286.

Shackleton, N. J. (1986-10-01). "Boundaries and Events in the Paleogene Paleogene stable isotope events". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 57 (1): 91–102.

Vinther, J., D. E. G. Briggs, R. O. Prum, V. Saranathan. 2008. The colour of fossil feathers. Biology Letters 4 (5): 522 - 525.

Zachos, James C.; Quinn, Terrence M.; Salamy, Karen A. (1996-06-01). "High-resolution (104 years) deep-sea foraminiferal stable isotope records of the Eocene-Oligocene climate transition". Paleoceanography. 11 (3): 251–266.

Zhang, R.; Kravchinsky, V.A.; Yue, L. (2012). "Link between Global Cooling and Mammalian Transformation across the Eocene-Oligocene Boundary in the Continental Interior of Asia]". International Journal of Earth Sciences. 101 (8): 2193–2200.

#Inkayacu paracasensis#Inkayacu#Penguin#Bird#Dinosaur#Birblr#Palaeoblr#Factfile#Birds#Dinosaurs#Aequorlitornithian#Ardeaen#Water Wednesday#Piscivore#South America#Paleogene#Prehistory#Paleontology#Prehistoric Life#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

212 notes

·

View notes

Text

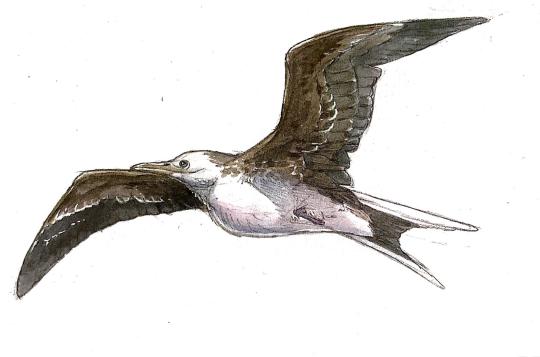

Meganhinga chilensis

By Ripley Cook

Etymology: The Great Darter

First Described By: Alvarenga, 1995

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Aequorlitornithes, Ardeae, Aequornithes, Suliformes, Anhingidae

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: 17 to 14 million years ago, in the Burdigalian to Langhian ages of the Miocene

Meganhinga is known from the Malla-Mall Member of the Cura-Mallín Formation

Physical Description: Meganhinga was, in a lot of ways, essentially just a scaled-up version of the birds we know today as Darters - it had a long body, with a very long neck, small head, and long pointy beak. This was similar in every way to living Darters. It was quite long for a darter, about a meter long, which is about as big as they get today (but usually living Darters are much smaller). But, notably for Darters, it had quite small wings indeed. This means that Meganhinga was, above all, a flightless bird.

Diet: Meganhinga probably fed on fish and other vertebrates, like its living relatives; its uncertain if it was able to dive as well as its living relatives, so its possible it relied more on land life than its living relatives.

Behavior: Meganhinga, being flightless, probably would have spent more of its time on land grabbing food than living relatives. Still, despite this, it would have spent much of its time by the shoreline, diving into the water and searching for food. Its long neck could be darted out to grab food, including fish, as it would stand on the shoreline. It would probably breed in colonies, and it seems most likely that they would have been somewhat monogamous in breeding habits like living Darters.

Ecosystem: Meganhinga lived in a lake and river basin near the coast, filled with plenty of aquatic places for Meganhinga to find food. This freshwater basin was created by extensive volcanic activity, which would have decided affected the ecology and creatures living there. Many different kinds of animals resided here with Meganhinga, though most were mammals; creatures such as Toxodonts, Astrapotherium, marsupials like Polydolops, the fascinating Mylodontid sloth Nematherium, a glyptodont, Protypotherium, a wide variety of rodents, and other creatures all populated the valley. Despite this, there doesn’t really seem to be another bird from this formation known at this time.

Other: Meganhinga is quite distinctive for being, possibly, the oldest known species of Darter, which makes the fact that it is quite weird compared to living darters very noticeable. In fact, a variety of large, flightless Darters from the Miocene have been found - Meganhinga, Macranhinga, and Giganhinga - all from the are of Chile in the Miocene. This indicates flightlessness was a major lifemode for Darters prior to modern times. Interestingly enough, some phylogenies indicate modern darters evolved from these forms, meaning that these flightless birds re-evolved flying ability in response to environmental factors.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Alvarenga, H. F. 1995. A large and probably flightless Anhinga from the Miocene of Chile. Courier Forschungsinstitut Senckenberg 181: 149-161.

Areta, J. I., J. I. Noriega, D. Angolin, F. Angolin. 2007. A giant darter (Pelecaniformes: Anhingidae) from the Upper Miocene of Argentina and weight calculation of fossil Anhingidae. N. Jb. Geol. Palaont. Abh. 243 (3): 343 - 350.

Chavez, M. 2007. Fossil birds of Chile and Antarctic Peninsula. Arquivos do Museo Nacional, Rio de Janeiro 65(4):551-572

Croft, D. A., J. P. Radic, E. Zurita, R. Charrier, J. J. Flynn, A. R. Wyss. 2003. A Miocene toxodontid (Mammalia: Notoungulata) from the sedimentary series of the Cura-Mallín Formation, Lonquimay, Chile. Revista geológica de Chile 30 (2): 285 - 298.

Croft, D. A., R. Charrier, J. J. Flynn, A. R. Wyss. 2008. Recent additions to knowledge of Tertiary mammals from the Chilean Andes. Simposio Paleontología en Chile 1: 91 - 96.

Flynn, J. J., R. Charrier, D. A. Croft, P. B. Gans, T. M. Herriott, J. A. Wertheim, A. R. Wyss. 2008. Chronologic implications of new Miocene mammals from the Cura-Mallín and Trapa Trapa formations, Laguna del Laja area, south central Chile. Journal of South American Earth Sciences 26 (4): 412 - 423.

Mayr, G. 2017. Avian Evolution: The Fossil Record of Birds and its Paleobiological Significance. Topics in Paleobiology, Wiley Blackwell. West Sussex.

Pedroza, V., J. P. Le Roux, N. M. Guitérrez, V. E. Vicencio. 2017. Stratigraphy, sedimentology, and geothermal reservoir potential of the volcaniclastic Cura-Mallín succession at Lonquimay, Chile. Journal of South American Earth Sciences 77: 1 - 20.

Rubilar, A. 1994. Diversidad ictiologica en depositos continentales miocenos de la Formacion Cura-Mallin, Chile (37-39°S): implicancias paleogeograficas. Revista Geológica de Chile 21 (1): 23- 29.

Suárez, M., C. Emparan. 1995. The stratigraphy, geochronology and paleophysiography of a Miocene fresh-water interarc basin, southern Chile. Journal of South American Earth Sciences 8 (1): 17 - 31.

#Meganhinga#Meganhinga chilensis#Darter#Dinosaur#Bird#Birds#Prehistoric Life#Palaeoblr#Birblr#Dinosaurs#Ardeaen#Prehistory#Paleontology#Aequorlitornithian#Terrestrial Tuesday#Piscivore#South America#Neogene

94 notes

·

View notes

Text

Apteribis

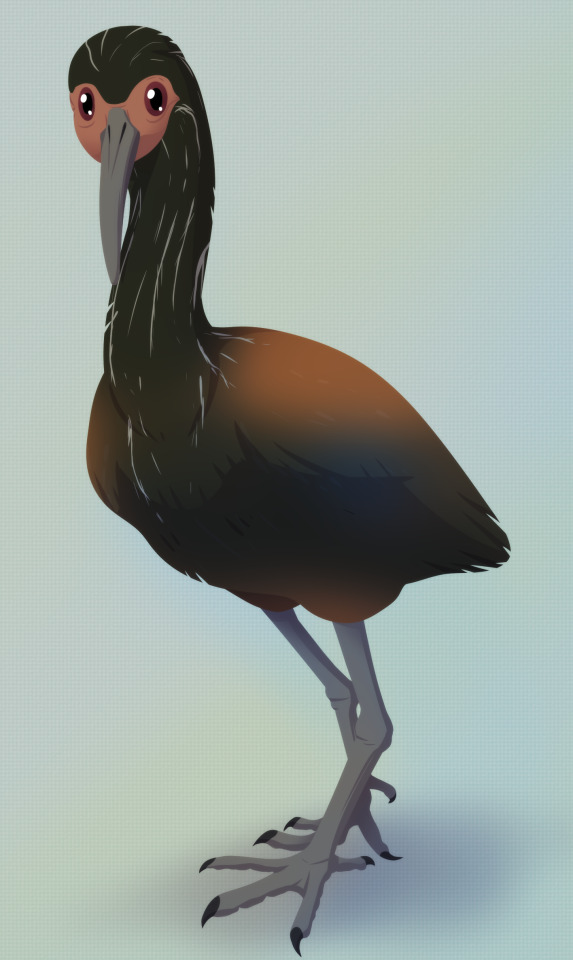

By Scott Reid

Etymology: Wingless Ibis

First Described By: Olson & Wetmore, 1976

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Aequorlitornithes, Ardeae, Aequornithes, Pelecaniformes, Threskiornithidae, Threskiornithinae

Referred Species: A. glenos (Molokai Flightless Ibis), A. brevis (Maui Flightless Ibis)

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: Between 200,000 years ago until sometime in the past 1000 years, from the Chibanian of the Pleistocene through the Holocene

Apteribis is known from the islands of Maui, Lanai, and Molokai

Physical Description: Apteribis looked, in a lot of ways, like your typical Ibis - it had a very long bill and skinny legs. Beyond that, though, it looked very different - it was more squat, for one, and it had a large round body. It also basically didn’t have any wings. This gave it, in a lot of ways, the appearance of a Kiwi, but it was an Ibis! We do have feathers from this animal that show it was brown in color, some darker brown and other feathers lighter brown of course but still overall brown - helping to add to that appearance like a Kiwi. And, like the living Kiwi, it was flightless.

Diet: There is nothing to suggest that Apteribis wasn’t like other Ibises, feeding mainly on invertebrates.