#Apteribis

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

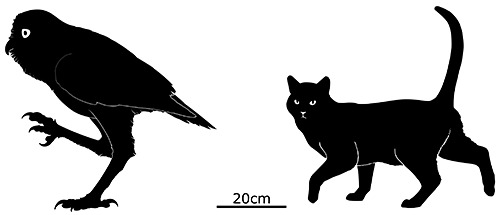

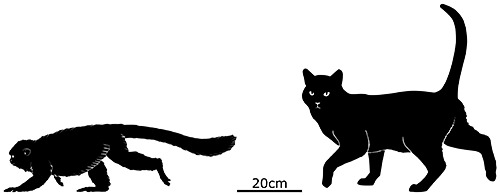

Island Weirdness #42 — Tall Owls & Short Ibises

The complete lack of land mammals on the Hawaiian islands left the terrestrial predator niches available to birds — and it was owls who ended up taking advantage of that role in the ecosystem.

The Grallistrix owls were found on Kauaʻi, Oʻahu, Molokaʻi, and Maui, with each island having its own endemic species. They were a type of true owl, probably descended from a species of Strix, and developed especially long legs that led to their nickname of "stilt-owls".

The Molokaʻi stilt-owl (Grallistrix geleches) was the largest of the four known species, about 60cm tall (2'). Although it had proportionally short wings it was still capable of flying, and probably specialized in stalking and ambushing smaller birds like Hawaiian honeycreepers in the dense forests.

(These owls were also the inspiration for the pokémon Decidueye!)

Meanwhile the forest floor insectivore niche was occupied by Talpanas on Kauaʻi, but on the other main islands a different type of bird took up the same role.

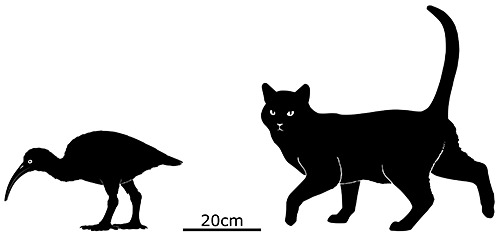

Apteribis was an ibis closely related to the modern white ibis and scarlet ibis, with three different species found on the islands of Maui, Molokaʻi, and Lānaʻi.

The Moloka'i flightless ibis (Apteribis glenos) was a typical example of the genus, about 50cm long (1'8"). It was flightless, with reduced wings, and had unusually short stocky legs that gave it proportions much more like a kiwi than an ibis. And it probably lived very much like a kiwi, too, probing around in the forest litter with its beak searching for snails and other invertebrates.

We even have an idea of the coloration of these birds, thanks to subfossil remains with preserved feathers. They seem to have been brown and beige, similar to the juvenile plumage of their close relatives.

The arrival of humans at least 1000 years ago would have unfortunately been devastating to both the stilt-owls and the flightless ibises. The combination of hunting, habitat destruction, and invasive dogs, pigs, and rats attacking them and their ground-based nests probably drove them all into extinction very quickly.

#science illustration#island weirdness 2019#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#grallistrix#strigidae#owl#apteribis#threskiornithidae#ibis#bird#dinosaur#art#convergent evolution#hawaii#holocene extinction#a superb owl#island weirdness 2: endemic boogaloo#decidueye#pokemon

370 notes

·

View notes

Text

Apteribis

By Scott Reid

Etymology: Wingless Ibis

First Described By: Olson & Wetmore, 1976

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Aequorlitornithes, Ardeae, Aequornithes, Pelecaniformes, Threskiornithidae, Threskiornithinae

Referred Species: A. glenos (Molokai Flightless Ibis), A. brevis (Maui Flightless Ibis)

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: Between 200,000 years ago until sometime in the past 1000 years, from the Chibanian of the Pleistocene through the Holocene

Apteribis is known from the islands of Maui, Lanai, and Molokai

Physical Description: Apteribis looked, in a lot of ways, like your typical Ibis - it had a very long bill and skinny legs. Beyond that, though, it looked very different - it was more squat, for one, and it had a large round body. It also basically didn’t have any wings. This gave it, in a lot of ways, the appearance of a Kiwi, but it was an Ibis! We do have feathers from this animal that show it was brown in color, some darker brown and other feathers lighter brown of course but still overall brown - helping to add to that appearance like a Kiwi. And, like the living Kiwi, it was flightless.

Diet: There is nothing to suggest that Apteribis wasn’t like other Ibises, feeding mainly on invertebrates.

Behavior: Even though Apteribis was flightless, it still had hooklets in its feathers - usually used to provide structure in flight, for Apteribis they would have provided strength against stress in the wind and water. As such, Apteribis probably still contended with fairly perilous environments, probing through the waves or wading in strong wind to find food. It also probably spent a good amount of time looking for food in the litter of the forest floor, being associated strongly with the rainforests of Hawai’i. It would have used that long beak for probing, and its still skinny legs to carefully wade through whatever it was walking across. Beyond that, the rest of its behavior is uncertain - without flight, it wouldn’t have moved around much; and it probably would have taken care of its young.

By José Carlos Cortés

Ecosystem: Hawai’i during the Ice Age was similar to Hawai’i today, just with some more arid conditions and different wildlife in general. Much like New Zealand, Hawai’i featured many kinds of unique birds, including Apteribis. There were also the Giant Hawaii Goose, a giant finch called the Giant Amakihi, the Giant Maui Crake, the High-Billed Crow, the Kaua’i Mole Duck, the Moa-Nalo, The Nēnē-nui, Stilt-Owls, and so many more.

Other: Apteribis did get quite big, but overall it wasn’t an example of island gigantism, just island flightlessness.

Species Differences: A. glenos lived primarily on the island of Molokai, while A. brevis was found more on Maui.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources Under the Cut

Dove, C. J., S. L. Olson. 2011. Fossil Feathers from the Hawaiian Flightless Ibis (Apteribis sp.): Plumage Coloration and Systematics of a Prehistorically Extinct Bird. Journal of Paleontology 85 (5): 892 - 897.

Godino, F.M.J. (2011). "Maui Upland Apteribis". The Extinction Website. Retrieved 2011-01-07.

Olson, Storrs; James, Helen (1991). "Descriptions of Thirty-Two New Species of Birds from the Hawaiian Islands Part I. Non-Passeriformes". Ornithological Monographs. 7.

#Apteribis#Ibis#Bird#Dinosaur#Prehistoric Life#Paleontology#Prehistory#Apteribis glenos#Molokai Flightless Ibis#Apteribis brevis#Maui Flightless Ibis#Flightless Ibis#Aequorlitornithian#Ardeaen#Water Wednesday#Insectivore#Australia & Oceania#Quaternary#Factfile#Birblr#Palaeoblr#Birds#Dinosaurs#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

96 notes

·

View notes

Note

Re ratite-like neoavians: what about Apteribis & Xenicibis as kiwi analogues?

I was thinking more of analogues to the “generalized idea” of a ratite and less to specific ratite groups, but I could see Apteribis and Xenicibis having broad similarities to kiwi, insofar as they were flightless and presumably tactile foragers. (Another candidate might be Capellirallus, though it was much smaller than kiwi.) Mind you, I probably wouldn’t call them particularly close kiwi analogues (for example, I don’t think there’s any evidence that either of the ibises was nocturnal); however, I also wouldn’t consider the Cuban flightless crane I mentioned previously a close ratite analogue either.

In a similar vein, one could arguably think of the dodo and the Rodrigues solitaire as rough “cassowary analogues”, being large and probably frugivorous flightless birds that lived in tropical forests.

0 notes

Photo

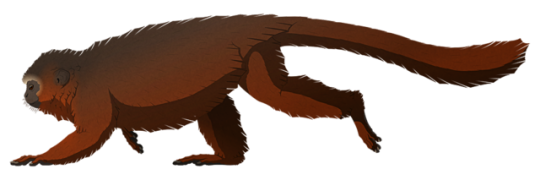

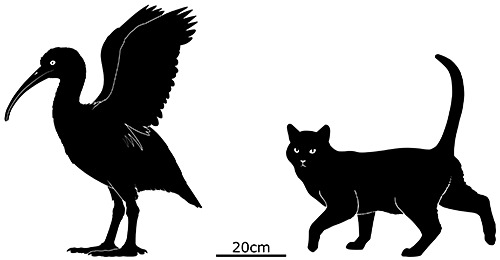

Island Weirdness #49 — Sloth-Monkeys & Fighting Ibises

Jamaica is the third largest island in the Caribbean, and much like Cuba it originated as part of a Late Cretaceous volcanic island arc. It began to subside during the Eocene and was completely submerged for a large portion of the Cenozoic, then was uplifted again in the early-to-mid Miocene, reaching close to its present-day size around 13 million years ago.

Few land mammals ever colonized the island prior to human influence, and most of the known remains are from rodents. But another group did make it onto Jamaica, and became something especially weird.

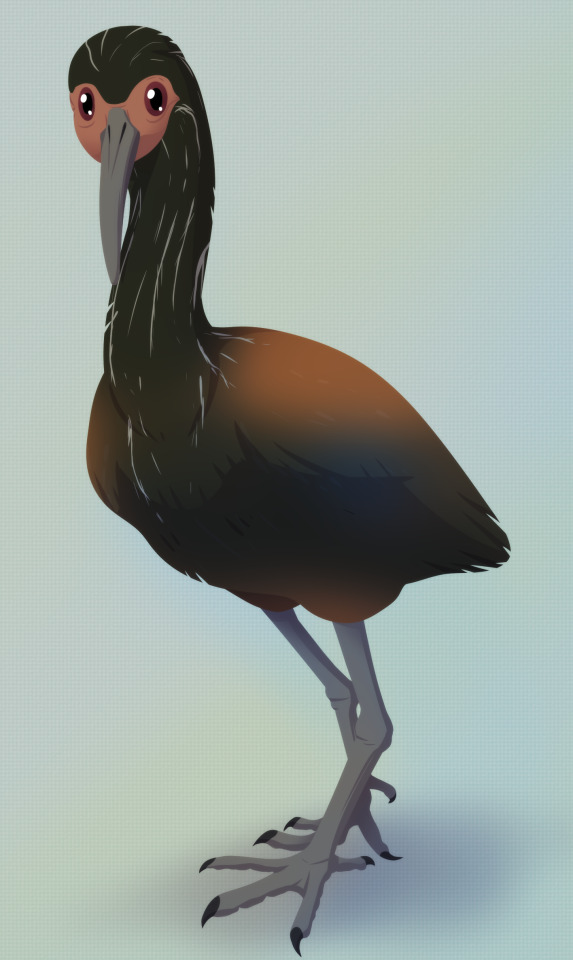

Xenothrix mcgregori is a primate only known from fragmentary remains, but what is known of its skeleton shows a unique combination of features for a New World monkey. It had a reduced number of teeth in its jaws, with enlarged molars, and oddly-shaped heavily-built leg bones that resemble those of slow quadrupedal climbers like lorises.

It was probably about 70cm long in total (2'4"), including the tail, and is thought to have lived a lot like a tree sloth, spending most of its time moving slowly around in the trees and possibly even feeding while hanging upside down.

Its anatomy was so ununsual that its evolutionary relationships were a mystery until ancient DNA was recovered from subfossil bones and confirmed it was actually a titi monkey very closely related to the genus Cheracebus. Its ancestors probably arrived on Jamaica in the late Miocene, around 11 million years ago, and it had some close relatives on a couple of other Caribbean islands — the terrestrial Paralouatta on Cuba, and Antillothrix and Insulacebus on Hispaniola — although they likely all independently colonized the Caribbean via different rafting events from South America.

Another inhabitant of Jamaica was an equally strange bird.

Xenicibis xympithecus was one of only two lineages of ibis ever known to have become completely flightless (the other being Apteribis from Hawaii).

Around 60cm tall (2'), it had some of the most unique wings of any bird. The hollow bones were thickened, its forearm was proportionally short, and the hand was modified into a large heavy "club" — and blunt-force injuries on some of these birds' remains suggest that they used their wings as weapons when fighting, clobbering each other with powerful blows.

Radiocarbon dating suggests the Xenothrix monkeys survived well into the Holocene, until around 1100 CE. Since various groups of humans had been present on Jamaica since about 4000 BCE the sloth-monkeys must have coexisted with them for several millennia, and their extinction may have been caused by more of a "slow fuse" of gradual habitat destruction than direct exploitation.

Dating on Xenicibis' extinction is less precise, with the youngest known remains being somewhere between 10,000 and 2200 years old. It may have still been around when the earliest humans arrived, but unlike the native monkeys it seems like it didn't last long beyond that point.

#science illustration#island weirdness 2019#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#xenothrix#xenotrichini#callicebinae#titi#platyrrhini#new world monkey#primate#mammal#xenicibis#threskiornithidae#ibis#pelecaniformes#bird#dinosaur#art#convergent evolution#jamaica#caribbean#holocene extinction#island weirdness 2: endemic boogaloo

173 notes

·

View notes

Note

Your piece on dinosaur color excludes Apteribis (Dove & Olson 2011).

Good catch, though I probably won’t include it. It differs from the other examples on the chart in that the preserved feathers are young enough that their original color has been retained and is discernible without melanosome analysis. I also haven’t included feather coloration known in moa, for instance. I’ll make a note of this in the description, however.

5 notes

·

View notes