#Zygodactylus grandei

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Zygodactylus

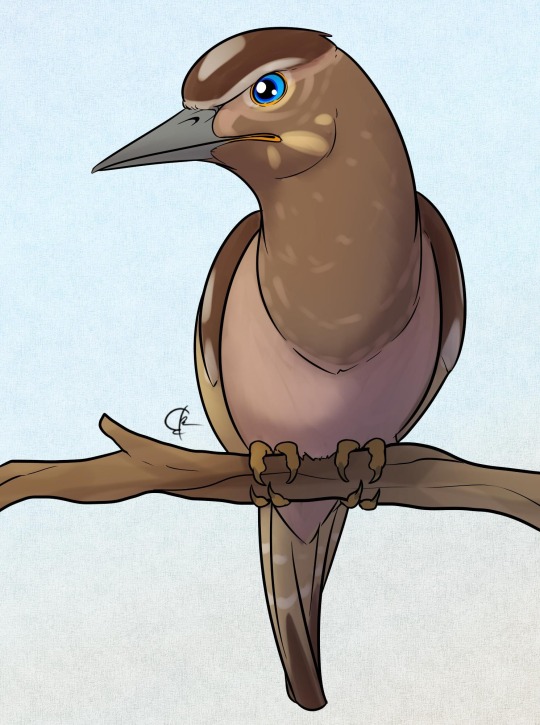

By José Carlos Cortés

Etymology: The one with two toes forward and two backward

First Described By: Ballman, 1969

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Australaves, Psittacopasserae, Passeriformes, Zygodactylidae

Referred Species: Z. grivensis, Z. ignotus, Z. luberonensis, Z. grandei, Z. ochlurus

Status: Extinct

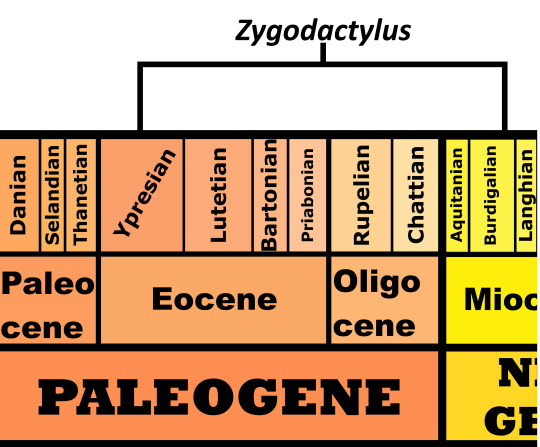

Time and Place: Between 52 to 17 million years ago, from the Ypresian of the Eocene through the Burdigalian of the Miocene

Zygodactylus is known from the Fossil Butte Member of the Green River Formation, the Renova Formation, the Revest-des-Brousses Formation, and the Wintershof-West Formation, a range extending over both North America and Europe

Physical Description: Zygodactylus was a small tree-dwelling bird, about the size of living tyrant-flycatchers (so no more than 12 or so centimeters long, probably usually smaller than this). It resembled living songbirds in most ways - it had a round body, small head, long and very skinny legs, and round wings. However, Zygodactylus differed from extinct songbirds in one very notable and important way: instead of having three toes pointed forward and one toe pointed backward, Zygodactylus had two toes pointed forward and two backward. This is important for evolutionary biology related reasons - which I’ll get into in the “other” section. They also had long, pointed beaks, like many kinds of living passerines. Any potential color of Zygodactylus has not been studied, but it stands to reason that it would have some distinct patterning to stand out during mating displays and in its forested habitats.

Diet: Based on the shape of the beak, it seems likely that Zygodactylus fed mainly on invertebrates and insects, using the sharp beak to spear slimy food or dig into bark for hidden grubs.

By Ripley Cook

Behavior: Zygodactylus would have been a primarily tree-dwelling bird, spending most of its time walking among the branches and searching for food. It would have used its specialized foot structure to hold onto tree branches and even trunks, though its toes were small and skinny and not the most adapted for trunk-grabbing. It would have probably spent a good amount of its time hopping from tree to tree on its quest, and possibly dug into wood to find food. This was a common bird, and as such it stands to reason that Zygodactylus would have been at least somewhat social - though whether that took the form of small family flocks or large flocks is uncertain. It would have taken care of its young, though beyond that we know little of its behavior.

Ecosystem: Zygodactylus lived for an extremely long period of time in Earth’s history, going from the origins of many modern groups of birds in the Eocene until the diversification of these groups into their specific families in the Miocene. In general, Zygoadctylus kept to forested environments, even as the global rainforest of the Eocene depleted and was replaced by more varied habitats, including vast arid shrubland and the first grasslands. Zygodactylus is known from such varying environments from the rainforest-lake of the Green River Formation, to a coastal mangrove forest, to a shoreline wood.

Green River Formation by Julius Cystoni

In the lakeside rainforest of the Green River Formation, Zygodactylus lived amongst sycamore trees along with ferns and palms, affected by the constant change of the Rocky mountains around them - which would periodically dump phosphorus into the lakes. There were a variety of fish such as rays, catfish, suckers, and herrings and sardines. Crocodiles like Borealosuchus were frequent, as well as many early primates, hoofed mammals, bats, and an armadillo-esque mammal. Dinosaurs were some of the most iconic creatures at the Fossil Lake, including the seagull-like Frigatebird Limnafregata, the flighted ratites Pseudocrypturus and calciavis, the flamingo-duck Presbyornis, the pheasant Gallinuloides, the early swift-hummingbird Eocypselus, the frogmouth-esque Fluvioviridavis and Prefica, the mousebird Anneavis, the woodpecker Neanis, the Parrots of Prey Cyrilavis and Tynskya, and Zygodacytlus’ own cousin Eozygodactylus. Of these, Zygodactylus would have had to watch out the most for its own relatives, the Parrots of Prey!

In the Dunbar Creek member of the Renova Formation, Zygodactylus lived in a more transitional environment, as the global rainforests were replaced with plains and other arid habitats. Here there were a variety of pine trees, as well as flowering plants like violets, roses, grapes, maples, and nogals. This was a series of woods surrounding ponds and streams feeding into said ponds, with plenty of habitats for Zygodactylus to hang out in. There were plenty of mammals here, including early dogs and horses, marsupials and rabbits, rodents and brontotheres, as well as rhinos. Other birds are not known from this formation.

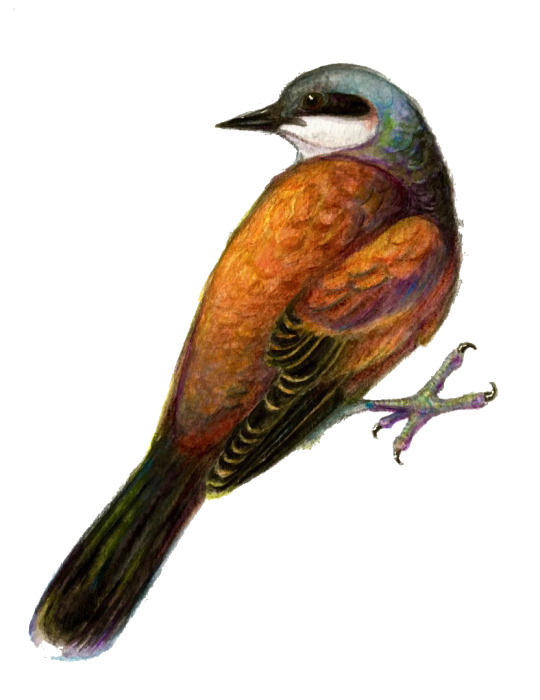

By Ashley Patch

In the coastal mangrove of the Rupelian of Southern France, Zygodactylus was joined by a wide variety of mammals - including rodents, horse relatives, ruminants, hedgehogs, and truly weird and giant hoofed mammals like Anthracotherium. As for other dinosaurs, there were early trogon relatives like Primotrogon, early hummingbirds like Eurotrochilus, early cuckoos like Eocuculus, and crane relatives like Parvigrus.

Finally, in the shoreline woodland of the Burdigalian of Germany, Zygodactylus lived among a wide variety of flowering trees, more so than conifers that had been more prevalent in the Eocene. Asterids, buckthorns, grapes, maples, and magnolias were especially common. Here, rodents were the primary mammalian neighbors, though there were some ruminants, bats, and carnivorous mammals like Prosansanosmilus. Snakes were even more common, though, and would have been major predators of Zygodactylus, such as boas and cobras. Birds were rarer here, though the pheasant Paleortyx was present alongside Zygodactylus.

By Jack Wood

Other: Zygodactylus is of fundamental importance because it is a missing link - a fossil that confirms the weird relationships we recover with genetic data. For a long time, genetic studies of the relationships between birds revealed a result literally no one would guess based on their shapes and ecologies: parrots and passerines were sibling groups. This was a major disconnect for researchers, since for a long time it was thought that passerines were more closely related to some of the other large tree-dwelling dinosaur groups with three toes forward and one back - namely, mousebirds and quetzals. So, what was needed was something linking the creatures with two forward and two back - like passerines - and the three forward one back songbirds. Zygodactylus and its relatives were the answer to that question. Being - by and large - almost identical to living passerines, these ancient birds had the legs and bodies of their living relatives, but the feet of their cousins. This showcases that, in terms of evolving for tree-dwelling, songbirds focused on their wing shape and skinny legs before changing up their feet. This makes Zygodactylus - and its relatives - utterly vital transitional fossils for the evolution of the most speciose group of living dinosaurs, the songbirds.

Species Differences: Z. grivensis and Z. grandei are known from the Green River Formation of Wyoming, with Z. grandei having shorter foot bones; Z. ochlurus is known from the Dunbar Creek Member of the Renova Formation; Z. luberornensis is known from the Revest-des-Brousses Formation of France; and Z. ignotus is known from the Wintershof-West of Germany.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Grande, L., P. Bucheim. 1994. Palaeontological and Sedimentological Variation in Early Eocene Fossil Lake. Contributions to Geology, University of Wyoming 30: 45.

Hieronymus, T. L., D. A. Waugh, J. A. Clarke. 2019. A new zygodactylid species indicates the persistence of stem passerines into the early Oligocene in North America. BMC Evolutionary Biology 19: 3.

Hutchison, J. H. 2013. New turtles from the Paleogene of North America. In D. B. Brinkman, P. A. Holroyd, J. D. Gardner (eds.), Morphology and Evolution of Turtles 477-497

Mayr, G. 2008. Phylogenetic affinities of the enigmatic avian taxon Zygodactylus based on new material from the early Oligocene of France. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 6(3):333-344

Mayr, G. 2009. Paleogene Fossil Birds. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg.

Mayr, G. 2017. Avian Evolution: The Fossil Record of Birds and its Paleobiological Significance. Topics in Paleobiology, Wiley Blackwell. West Sussex.

Olson, S. L. 1977. A Lower Eocene frigatebird from the Green River Formation of Wyoming (Pelecaniformes: Fregatidae). Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology 35:1-33

Olson, S. L., H. Matsuoka. 2005. New specimens of the early Eocene frigatebird Limnofregata (Pelecaniformes: Fregatidae), with the description of a new species. Zootaxa 1046: 1 - 15.

Smith, M. E., B. Singer, A. Carroll. 2003. 40Ar/39Ar Geochronology of the Eocene Green River Formation, Wyoming. Geological Society of America Bulletin 115 (5): 549 - 565. Stidham, T. A. 2014. A new species of Limnofregata (Pelecaniformes: Fregatidae) from the Early Eocene Wasatch Formation of Wyoming: implications for palaeoecology and palaeobiology. Palaeontology: 1 - 11.

Smith, N. A., A. M. DeBee, J. A. Clarke. 2018. Systematics and phylogeny of the Zygodactylidae (Aves, Neognathae) with description of a new species from the early Eocene of Wyoming, USA. PeerJ 6: e4950.

#Zygodactylus#Bird#Dinosaur#Songbird#Passeriform#Birblr#palaeoblr#factfile#perching bird#Zygodactylus grivensis#Zygodactylus ignotus#Zygodactylus luberonensis#Dinosaurs#Birds#prehistoric life#paleontology#prehistory#neogene#paleogene#north america#eurasia#insectivore#Songbird Saturday & Sunday#Zygodactylus grandei#Zygodactylus ochlurus

146 notes

·

View notes