#Le roman de Mélusine

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

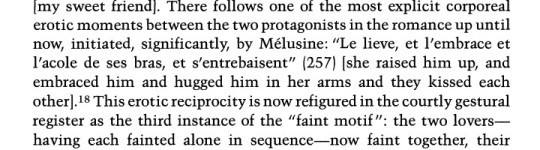

Litterally how I imagine this scene tbh

#i jest but honestly this story makes me very sad lol#mélusine loved her dumbass human husband! she clearly wanted to stay with him and their children! and he loved her too!#and he still managed to fuck it all up for both of them smdh#melusine#le roman de melusine

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fate Grand Order Servant Comparisons

Melusine - Dragon of Albion

Left - FGO

Right - from Le Roman de Mélusine between circa 1450 and circa 1500

Left - FGO

Right - 15th-century manuscript of Historia Regum Britanniae

Note: Lostbelt version of PHH Melusine

#fate grand order#fgo#melusine#fairy knight lancelot#tam lin lancelot#melusine fgo#fgo melusine#melusine fate#fate melusine

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

French fantasy: The children of Orpheus and Melusine

There is this book called “The Illustrated Panorama of the fantasy and the merveilleux” which is a collection and compilation of articles and reviews covering the whole history of the fantasy genre from medieval times to today. And in it there is an extensive article written by A. F. Ruau called “Les enfant d’Orphée et de Mélusine” (The Children of Orpheus and Melusine), about fantasy in French literature. This title is, of course, a reference to the two foundations of French literature: the Greco-Roman heritage (Orpheus) and the medieval tradition (Melusine).

I won’t translate the whole text because it is LONG but I will give here a brief recap and breakdown.

A good part of the article is dedicated to proving that in general France is not a great land for fantasy literature, and that while we had fantasy-like stories in the past, beyond the 18th century we hit a point where fantasy was banned and disdained by literary authorities.

Ruaud reminds us that the oldest roots of French fantasy are within Chrétien de Troyes’ Arthurian novels, the first French novels of the history of French literature, and that despite France rejecting fantasy, the tradition of the Arthuriana and of the “matter of Bretagne” stayed very strong in our land. Even today we have famous authors offering their takes, twists and spins on the Arthurian myth: Xavier de Langlais, Michael Rio, Hersart de la Villemarqué, René Barjaval (with his L’Enchanteur, The Enchanter, in 1984), Jean Markale, Jean-Louis Fetjaine or Justine Niogret (with her “Mordred” in 2013). He also evokes the huge wave and phenomenon of the French fairytales between the 17th and the 18th century, with the great names such as Charles Perrault (the author of Mother Goose’s Fairytales), Madame d’Aulnoy (the author, among others, of The Blue Bird), and Madame Leprince de Beaumont (author of, among others, Beauty and the Beast). He also evokes, of course, Charles Nodier, which was considered one of the great (and last) fairytale authors of the 19th century, the whole “Cabinet des Fées” collection put together to save a whole century of fairytales ; as well as the phenomenon caused by Antoine Galland’s French translation of the One Thousand and One Nights – though Ruaud also admits this translation rather helped the Oriental fashion in French literature (exemplified by famous works such as The Persian Letters, or Zadig) than the genre of the “marvelous”.

Ruaud briefly mentions the existence of a tradition of “quests” in French literature, again inherited from the medieval times, but quests that derived from Arthurian feats to romantic quests, love stories, “polite” novel of aristocratic idylls or pastoral novels of countryside love stories – the oldest being Le Roman de la Rose (the Novel of the Rose, the medieval text began by Guillaume de Lorris in the early 13th century and completed by Jean de Meung one century later), and the most recent L’Astrée (THE great romantic bestseller of the 17th century, written by Honoré d’Urfé). But overall, Ruaud concluded that between the 17th-early 18th century (the last surge of the marvelous, abruptly cut short by the French Revolution and the reshaping of France) and the 1980s (the time during which role-playing fantasy games and the English-speaking fantasy was translated in France), there was very little “fantasy” to be talked of as a whole, a gap that resulted in people such as Gérard Klein declare in the 90s: “Fantasy is a literature made by ignorant people for ignorant readers, and with a true absence of any kind of challenge”.

At least for literature… Ruaud however spends a lot of time detailing the “fantastical” and “marvelous” traditions of visual art – from the stage performances to the movies. There was quite a rich tradition there, apparently. He starts by evoking the massive wave that the release in the United-Kingdom of “The Dream of Ossian” caused. France ADORED Ossianic stuff – even when it was proven that it wasn’t an actual Scottish historical treasure, but a work made up by Macpherson, people still adored it – from Napoleon who commissioned enormous paintings illustrating the Ossianic stories, to the colossal opera by Jean-François Lesueur, “Ossian ou les Bardes”, created for the then brand-new Imperial Academy of music.

There was also the fashion of the “féeries”, a type of stage-show that was all about depicting stories of fairies, gods, magics and other fairytale elements – the “féerie” fashion was at the crossroad between the opera, the ballet and the theater, and in the “dreary, drab and modern” era of the 19th century, people were obsessed with these “little pieces of blue sky” and “golden fairy-clouds”. However, despite the quality of the visuals, costumes and sets (which made the whole power of those féerie, it was their visuals and their themes that drew people in), the dialogues and the plots were noted to be quite bad, simplistic if not absent. The “féeries” were not meant to be great work of arts or actual literature, but just pure entertainment. Gustave Flaubert, right after finishing Salammbô (see my previous post), was exhausted and trying to escape the colossus of the historical novels, he tried to entertain himself by getting into the fashion of the féeries. He read thirty-three féeries in one go, and he was left sickened by so much mediocrity. He decided to create his own féerie that would rehabilitate the genre, and the result was “Le Château des Coeurs”, “The Castle of Hearts”. Nine “tableaux” written by Flaubert on a “canevas” by his friend Louis Bouilhet: “The gnomes, the new avatar of the bourgeois, are stealing the hearts – and thus the ability to love – of humans, to keep them locked up in the vault of the Castle of the Hearts, as their treasure. But the fairies are afoot: they will try to revive love on earth, through two human beings that are said to still have a heart, and to still have the ability to love”. Unfortunately this play, while entirely created, was never actually showed on any stage due to two things. One, at the time the féeries were falling out of fashion and nobody wanted to see them anymore ; two, Flaubert was carried away and placed a LOT of special effects in his play, many which were incredibly more complex than those used at the time. A typical féerie special effect would be for example for a table to turn into a chair, or for a bed to turn into a hammock – but Flaubert demanded for a YOUNG MAN to turn into a DOOR LINTEL.

Anyway… The use of legends and myths was also reigniting in operas thanks to the enormous success of Wagner’s pieces. Claude Debussy created a “Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune” in 1894, based on Mallarmé’s work (Prelude to a Faun’s afternoon), and later created a Pelléas et Melissande in 1902 based on Maeterlinck. But again… In France, the literature was all about the “fantastique” rather than the fantasy – the supernatural was supposed to be of this disquieting, disruptive, bizarre magic, wonders and horrors that entered the normal, rational, logical reality we all knew. It was the reign of Gautier, Maupassant and Poe through the lenses of Baudelaire). In the 20th century a lot of authors touched upon the “wonderful” and the “marvelous”, but they were discreet touches here and there: André Dhôtel, André Hardellet, Jacques Yonnet, Charles Duits, Henri Michaux, Marcel Aymé, Pierre Benoît, Marguerite Yourcenar, Sylvie Germain, Maurice Maeterlinck, Julien Gracq… Once again, the visuals won over literature – and to symbolize the French fantasy cinema of the 20th century, Ruaud only has to mention one name. Jean Cocteau. Cocteau and his two most famous movies: La Belle et la Bête (Beauty and the Beast, 1946) and Orphée (Orpheus, 1949). They stay to this day the greatest “fantasy movies” of the 20th century.

But unfortunately for France, there never was any “popularization” of the fantasy through media like the pulps of the USA. Science-fiction as a genre was accepted though, to the point that anything that was a “marvel”, a “wonder” or a “supernatural” had to be science-fiction, not magic. The 70s and 80s were the supreme rule of the science-fiction in France: Jean-Pierre Fontana had his stellar ark/arch, Alain Paris his antediluvian continent, Michel Grimaud his spatial colonization, Bernard Simonay his spy-satellites, Hugues Doriaux all sorts of sci-fi gadgets… In this time, if you wanted to do something out of ordinary, you had to go into speculative science, else you wouldn’t be taken seriously. Again, it was Klein’s opinion that fantasy was for “ignorant” readers and writers who didn’t like to “challenge” themselves.

However, in this “desert” that preceded the true fantasy boom of the 90s in France, Ruaud claims that there are actually true French fantasy novels: five “ancestors” of the French fantasy. And those I’ll reveal in a second post…

12 notes

·

View notes

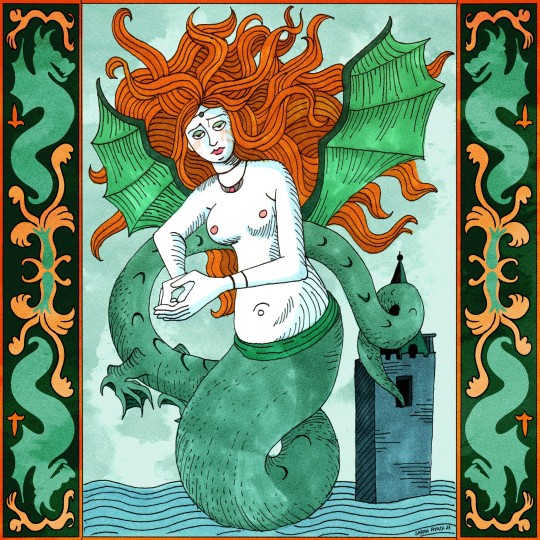

Text

Hop je vous partage une de mes premières recherches graphiques, réalisée entre les sessions de lecture du roman de Jean d'Arras (dont je commence à voir le bout) ! Vous aurez bien sûr reconnu Mélusine qui est le sujet de ma résidence à Moulin Boissard, près de Lusignan. J'ai eu la chance d'y être invitée par Pilau Entre Les Cases avec le soutien inestimable de l'Alca Nouvelle Aquitaine !

Je vous en dis plus bientôt 🐍

#illustration#medieval fantasy#melusine#lusignan#poitou#medieval#fée#fairy#dragon woman#dragon#snake

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ou comment je suis devenue obsessed par l'esthétique moyenâgeuse

(imaginez qu'il y avait un premier titre avant le sous-titre)

ps: Alors là je vais carrément raconter ma vie sans raisons apparentes

Comment passer à côté de la trend des illustrations de chevalier en quête et de mage autour d'un feu de forêt qui ont conquit la toile cet été 2024 ? J'avais les deux pieds dedans mais bien avant ça, un long cheminement mental m'a amené à cet état.

Je pourrai commencer par mon enfance et le livre L'imagerie des Sorcières et des Fées qui relataient des légendes comme celles de Mélusine, la femme serpent, que j'ai redécouvert du haut de mes 19 ans. Et bien sur, comme tous les enfants, j'étais émerveillé par les cartes de faux territoires qui se trouvaient dans mes romans, librement inspiré de celles du moyen-âge. J'en créé pendant les heures d'études avec mes amies.

Mais je préfèrerait faire un bon dans le temps et vous parler de comment j'ai décorer ma chambre avec des illustrations de vieux livres dont des ouvrages datant du moyen-âge (ou prétendant l'être) il y a 4 ans. Rendant mon feed Pinterest absolument au garde à vous pour continuer à nourrir mon imagier mental d'esthétique gothique moyenâgeuse. (et ça ne fait qu'empirer)

L'exposition Les Animaux Fantastiques du Louvre Lens (janvier 2024) qui m'a tellement marqué! Tout un univers de peintures moyenâgeuses fantastique (dans le sens magique du terme) s'est déployé devant mes yeux émerveillés.

Ensuite j'ai trouvé mon style de dessin et je compte bien y incorporer le manque de perspective propre au illustrations de cet époque.

Côté musique, l'illustration de l'album XIII d'Asinine et celle de Tuer la Bête de Vilhelm et FEMTOGO ainsi que la chanson en soit. Aussi les introductions des sons NOIR FLUO et BLOCK AFRIC de Dinos dans lesquelles on entends des bruits de sabot et un hennissement ont suffit à me rentrer dans un autre univers que celui du rap. (Allez regarder et écouter ça par vous même, envrai j'ai la flemme de développer plus j'avoue)

Il y a certainement d'autres influences mais c'est celles qui me viennent en tête et je suis fatiguée d'écrire. (et je vais pas me relire pardonnez moi)

Sur ce,

0 notes

Text

Français : Mélusine en son bain, épiée par son époux Raimondin. Roman de Mélusine par Jean d'Arras

English: Melusine's secret discovered, from Le Roman de Mélusine.

1 note

·

View note

Text

“Raymond Epiant Mélusine” miniature extraite du “Roman de Mélusines” de Jean d'Arras (circa 1450) présenté à la conférence “Les Sorcières dans l'Art” par Marine Chaleroux - Historienne d'Art - de l'association Des Mots et Des Arts, octobre 2023.

1 note

·

View note

Text

C'est avec joie que je vous présente mon nouveau roman : "L'Institut", tome 3 de la série "Les 7 Grimoires". Disponible sur Amazon en eBook et livre broché.

#bookstagram#instabook#instalivre#harkale linai#grimoire#magieverte#magie#roman#livre#livrejeunesse#livre jeunesse#livrestagram

0 notes

Photo

Anonymous

Melusine's secret discovered, from Le Roman de Mélusine, ca.1450/1500, illumination on parchment

Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Inv. Français 24383, folio 19

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Le roman de Mélusine de Jean-Pierre Tusseau

[Chronique Roman Classique] Mon #avis sur "Le roman de Mélusine" de Jean-Pierre Tusseau @ecoledesloisirs : Une version abrégée et abordable d'un grand classique et d'une belle histoire d'amour !

[box type=”info” align=”” class=”” width=””]

Nombre de pages : 168 pages Editeur : L’école des Loisirs Collection : Classiques Date de sortie : 22 janvier 2020 Langue : Français ISBN-10 : 2211306373 ISBN-13: 9782211306379 Prix éditeur : 5,50 € Disponible sur liseuse : Non

De quoi ça parle ?

Mélusine est l’une des grandes enchanteresses du Moyen Age. Issue de la culture populaire, Mélusine est une fée du…

View On WordPress

#Fée#Jean-Pierre Tusseau#L&039;école des Loisirs#Le roman de Mélusine#Mélusine#mensonge#Poitou#secret#Serpent#trahison

0 notes

Link

#Amour#Appréciation#éditionscharleston#carnetparisien#Contedefées#Contemporaine#famille#idylle#MélusineHUGUET#romancecontemporaine#Unjourdeplusdetonabsence#UnjourdeplusdetonabsencedeMélusineHUGUET

0 notes

Text

"Les muses s'amusent ! " Texte de Claryssandre

©Claryssandre. Tous droits réservés. 2022

Les muses s'amusent !

Capucine, enfantine, maligne et mutine

Butine de fleurs en fleurs, de cœurs en cœurs

Et caline le bonheur de douce et belle humeur !

Pateline et non chafouine

Jamais elle ne chouine ou rumine Mais de son aide est bien radine !

Mélusine, sa belle cousine

Tour à tour mâtine, sublime, féline ou sanguine,

Sans détours, lutine, taquine, tambourine ou fulmine

mais jamais, ô grand jamais ne bouquine !

Pas tendre, la fée salamandre n'a que faire de Claryssandre.

Les mots ? Fariboles et gaudrioles !

De son aide, elle oublie l'obole !

Cavalière, fière et altière,

Un tantinet casanière,

La muse Artebuse, peu vertueuse,

Est capricieuse et facétieuse,

Rarement audacieuse,

Souvent odieuse et vicieuse,

Soucieuse et souffreteuse,

Parfois talentueuse mais

Toujours dédaigneuse et de son aide oublieuse !

Après trente ans de silence,

Sans science ni conscience,

Les mots fusent et se bousculent.

Mais ces muses,

tarentules-arquebuses sans scrupules,

Sur ma lassitude spéculent,

M'usent et à mes dépends s'amusent !

Claryssandre. 7 septembre 2022

Musique: Taisho Roman

Musicien: PeriTune

URL: http://peritune.com

License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

(Youcut Video)

0 notes

Text

I will switch the discussion to my fairytale blog for easier convenience.

I again agree with what you say, and again there is a lisunderstanding somewhere X) But that's what happens when you delve into fairy nature, everybody gets confused by their magic :p

The confusion here is that I agree with you that the literary fairy, the fée in "fairy tale", the fairies described by Perrault and d'Aulnoy and whatnot, are NOT Celtic in any way. No. They take their inspiration from a mix of the fairies/ogresses of Italian fairytales (a la Basile and Straarola), of the medieval French fée (d'Aulnoy for example read a lot of medieval romances - and one of her first fairy godmothers is named "Merluche" as a parody of Mélusine), and of Greco-Roman mythology (d'Aulnoy did that with a few of her fairies, such as the fairy Amazon, and it was a tradition by other authors, for example in the "Rainbow Prince" fairytale that went around Youtube, Lagrée the wicked fairy is named after "les Grées", the Graeae of Greek mythology).

What I meant to say by nuancing the term "Celtic" is that when you take the medieval fée, and the folklore around the fée as a whole, you have a strong Celtic influence. As in, not only do we share a lot of medieval "fey" with the British Isles thanks to the Arthuriana, hence a Celtic influence from things such as Welsh or old Irish beliefs (though more distant) - but the French fées of the Middle-Ages also bear a very strong mark of the old Gallic beliefs, of the continental Celts, to the point they are one of the main sources of info when it comes to reconstructing Gallic mythology. Why for example are the fées of France always near a body of water or near a tree - the typical "fée à la fontaine" (literaly "fairy of the fountain", though fountain used to mean any type of stream), and "la fée de l'arbre", (the tree fairy, the fairy found in clearings)? These are strong topos of French medieval literature, that stayed living throughout the fairytales of Renaissance (take Perrault's Toads and Diamonds). And we do know that this was a leftover of the Gallic religion, whose one of the main focus was to have a strong "natural cult", a worship of specific landscape areas... Most notably bodies of fresh water, certain clearings/trees, and several raised stones. The very same area, often, that either in folklore and folktales, or in medieval literature, became associated with "fairies" or where an "otherwordly lady" appears. (And while the priesthood and "oracles" of the Gauls were performed by the all-male druids - from which the figure of the "enchanteur" in French borrows heavily ; we also know the Gallic folk did have a believe in otherwordly priestesses - most notably there was a belief in nine eternally virgin priestesses that lived on a secret island and killed men that dared spy on them, something echoing the legend of Avalon and of Morgan and her eight sisters). So this is why it is commonly agreed that, in France, the fées of both folklore and literature were transcriptions in a new world of the old pagan beliefs in supernatural priestesses and nature-spirits, as held by the people of Gaul.

I do fully agree with your analysis of how different the "salon fairies" are from the "Arthurian fairies" and I agree - I do want to make clear I never said they were the same, but that in France they are the two "eras" of a given history for the figure of the fée, which went from Viviane, Morgane and Mélusine to Cinderella's fairy godmother and Sleeping Beauty's fairies and whatnot. We do have "Le Petit Peuple", "The Small Folks", "The Little People" in France to designate all the more non-human supernatural beings (dwarfs and lutins and korrigans and whatnot), but what I was trying to say is that whereas beyond the Channel calling a small, male, supernatural entity such as the Leprechaun a "fairy" is more acceptable, in France you can't exactly call a "lutin" a "fée" as they are much more distinct and separate, though the two are indeed connected and often put in the same basket. But due to "fée" being a more restrictive word than "fairy", it doesn't have the same open possibilities as the English word - that was kind of my point. Though, in the Middle-Ages there was an habit of using "fée" not just as a name but also as an adjective, similar to the English "fairy", to designate magical things (there were talks of fée-horses for example), and this tradition lasted discreetly in French fairytales (Perrault describes the seven-league boots and Bluebeard's key by using the adjective "fée"), but it stayed quite rare. This is why for example we know, thanks to analysists and folklorists, that there were "male fées" in medieval literature, but... they are basically never called "fées" since the word is so stuck to the idea of a female creature, and we have to look at context and patterns to identify the male counterpart of the "fairy ladies".

Again, I do not want to twist too much Laurence Harfn-Lancner words, so for the record, while I did use Viviane and the Chrétien de Troyes incarnation of Morgane for "Arthurian fairy godmothers" archetypes, these are not the main or major example of Lancner, who rather uses them for her category of "Fairy Lovers". (And yes, the Morgane/Mélusine division is now used by pretty much every medievalist in France - Lancner's first researches were published in the early 90s before being reprinted in the early 2000s, so people had time to get used to it. We call it "le schéma mélusinien" et "le schéma morganien". In fact, if I just take one of her books "Le Monde des Fées" - the three main section under the "Fairy Lover" chapter are, Mélusine, Morgane and the Lady of the Lake. Her analysis of the medieval "fairy godmother" rather relies on works such as the Perceforest (the three goddesses), Le Jeu de la Feuillée (the three fairies), Amadas et Ydoine (three witches pretend to be fées), Le Roman d'Aubéron (four Christmas fairies) and the medieval belief in Dame Abonde, with mentions of the leftovers of Roman, Norse and Gallic mythologies.

I would also have to object to your stance that the fairies of the salon are more "human" than the Arthurian fées. I will object because there's the case of Morgan Le Fey. (This is the name English folks use for her but it drives me mad because "le" is a male pronoun, it should be "la", it is a misunderstanding of Morgane la Fée, but anyway). There is the fact that one of the recurring elements in the figure of Morgan (ignoring old Celtic goddess roots), s that her "fey" titled is joined with a human nature by explaining as such: she learned so many great and secrets arts, and she ruled over fabulous lands, and she mastered magic, and thus she was called "fée". There is this idea that even a regular human woman can become a "fée" or be seen as a "fée" simply by being associated with supernatural forces (Morgane's study with Merlin for example) or by wielding extremely advanced craft. This all ties to how a lot of the mysterious, unnamed ladies of for example the Chrétien de Troyes novel have this ambiguity of: are they human? Are they fée? Do they belong to the Otherworld or the regular world? We have to rely on contextual clues to know that, because it is not obvious, and because even a regular human woman can play the role of the "fée". Fée is not as much separate from humanity in Arthurian French texts as it seems - and we fall back on the Tolkien's Elves comparison. Again, to identify a fairy in French medieval text, all you need to do is spot a tall beautiful lady in white - and that's because it is so vague that many fail to understand they are fairies. (Take the story of how Lusignan met Mélusine. He encountered her with two handmaids bathing by a water-stream in the forest at night, and he just noted they were tall and beautiful... And despite all the signs of a fée being here, night, forest, running water, tallness, beauty, female gender, he didn't get she was a fairy. Because it was not meant to be obvious within the world of medieval French literature)

With the "fées de salon", with Perrault and d'Aulnoy, on the contrary, we have a clear and neat work to make the fées separate from humanity and as alien as possible. You can never confuse a fée with someone else - unless they purposefully disguise themselves as a little old lady. But consider the fées of Perrault and d'Aulnoy... When they are beautiful, they wear impossible dresses made of all the precious metal in the world, and they wield weapons emitting light and fire, and they ride fire-chariots dragged by all sorts of fabulous creatures. When they are wicked and ugly, they are inhumanly ugly and collect all the deformations possible (I think it was the Queen of Meteors whose eyes were described as lamps at the end of a cavern, and who was so skinny and gaunt people could look through her skin as if it was translucid). They live in explicit impossible underworld, and beyond glass mountains, and in palaces of burning metal, and they are surrounded by dwarfs and giants and monstrous beasts as pets, and everywhere they go they cause obvious great magic and display their powers in all the way they can...

Considering how in Chrétien de Troyes novel for example you have to guess to know if a lady a knight randomly meets is from the Otherworld or not, versus how in literary fairytales people immediately recognize a fairy once she reveals her "true form" after shedding her little old lady disguise... I do believe the "writers of the salons" did their effort to make fairies less human. (An effort which was later reverted by the Grimm brothers for example, who removed all fairies from their texts due to being "too French" - take how in Briar Rose the fairies are now "wise women", in all the meanings of the word)

(Also, given posts cannot allow one to include tones, I insist that I say nothing in negativity and that I do not disagree with you as in "You're wrong". I agree with you and I am glad to have this conversation and I just want to bring in info from my part and my perception of things up until this point ; I do not mean to offend anyone, and it stays my personal opinion on the matter, I am no ultimately authority and I understand I would have views seen as weird Xp Plus this entire matter is so vast and complex and interwoven with so many cultures it is impossible to fully sort it out, so this is just my tiny little fragment I bring to the puzzle in hope that it fits)

I was thinking about the difference between the British "fairy" and the French "fée", and suddenly the perfect comparison struck me.

The "fairy" from British folklore is basically Guillermo del Toro's take on the fair folk, trolls, goblins and other fairies in his movies, from "Pan's Labyrinth" to "Hellboy II". You know, all those weird monsters and bizarre critters with strange laws and customs, living half-hidden from humans, and coming in all sorts of shapes and sizes and sub-species and whatnot. Almost European yokai.

But the "fée" of French legend and literature? The fées are basically Tolkien's Elves. Except they are all female (or mostly female).

Because what is a "fée"? A fée is a woman taller and more beautiful than regular human beings. She is a woman who knows very advanced crafts and sciences, and wields mysterious unexplained powers. She is a woman who lives in fabulous, strange and magical places. She is a woman with a natural knowledge or foresight of the past and the future, and who can appear and disappear without being seen. Galadriel as she appears in The Lord of the Rings is basically the best example I can use when trying to explain to someone what a "fée" in French folklore and culture actually is.

(As a reminder: the fées of France are mostly represented by the Otherwordly Ladies of the Arthurian literature - Morgane, Viviane, bunch of unnamed ladies - or by the fairy godmothers of Perrault or d'Aulnoy's fairytales, to give you an idea of how they differ from the traditional "fae" or "fair folk". All female, and more unified, and so human-like they can pass of or be taken for humans. The "fées" are cultural descendants of the nymphs and goddesses and oracles/priestesses of Greco-Roman-Germanic-Gallic mythologies. That's why they are so easily confused with witches when they turn evil, and when Christianity arose most fées were replaced by the figure of the Virgin Mary, the most famous "magical beautiful otherwordly woman" of the religion)

#reblog#discussion#fairies#fairy godmothers#fairies in fairytales#fée#french folklore#medieval literature#medieval folklore#fées

145 notes

·

View notes

Text

Study’s corpus

Middle Age

Jean d’ARRAS, Mélusine ou La Noble Histoire de Lusignan, éd. Jean-Jacques Vincensini, Paris, Le Livre de Poche, Lettres Gothiques, 2003.

COUDRETTE, Le Roman de Mélusine, éd. Laurence Harf-Lancner, Paris, GF Flammarion, 1993.

Plays 18th centuries

FUZELIER, Louis, « Mélusine », Dictionnaire des théâtres de Paris contenant toutes les pièces qui ont été représentées jusqu'à présent sur les différents théâtres français, et sur celui de l'Académie royale de musique [en ligne], éd. Claude Parfaict, Paris, vol. 3, 1767, p. 379-393.

LE BRUN, Antoine-Louis, Théâtre lyrique : avec une préface où l'on traite du poème de l'opéra et une réponse à une épitre satyrique contre ce spectacle [en ligne], ed. Ribou Pierre, Paris, 1712, p. 125-154.

Novel and fairytales 17th/18th centuries

NODOT, François, Histoire de Mélusine Princesse de Lusignan et de ses fils, suivie de l’Histoire de Geofroy à la grand’dent [en ligne], éd. Favre, Paris, Champion, 1867.

Marguerite de LUBERT, ed. Aurélie Zygel-Basso. « La Princesse Camion » dans Contes, Honoré Champion, Print. Sources Classiques 60, 2005.

Marguerite de LUBERT, ed. Aurélie Zygel-Basso. « Le Prince Glacé et la Princesse Etincelante » dans Contes,Honoré Champion, Print. Sources Classiques 60, 2005.

MURAT, Henriette-Julie De Castelnau, ed. Geneviève Patard. « Anguillette » dans Contes, Honoré Champion, Print. Sources Classiques 72, 2006.

MURAT, Henriette-Julie De Castelnau, ed. Geneviève Patard. « Peine Perdue » dans Contes, Honoré Champion, Print. Sources Classiques 72, 2006.

Madame d'AULNOY« Le Prince Lutin » dans Contes, Honoré Champion, Bibliothèques des génies et des fées, Paris, 2005.

0 notes

Text

Tales of Melusine: Part 2 - Raymondin

Le Roman de Mélusine by Jean d'Arras, circa 1450-1500

Melusine, cursed by her mother to wander, searched for what many women do, a faithful partner. One day, while bathing in a fountain, a count named Raymondin came across her. Like the Biblical King David, he fell in love with her at once. Melusine, unsure, put him off, but he would not be deterred, and so like her mother, she warned her suitor, that she would marry him, but only if he vowed to allow her to confine herself on Saturdays, so that neither her nor any in his court would see her. If he swore so, she would bring him power and riches, and bear him many children. Perhaps, unlike her mother, Melusine saw greed as a way to guarantee fidelity, or perhaps she merely wished to reward loyalty.

At any rate, the Count agreed, and they were wed. As a wedding gift she built him the Château de Lusignan, so quickly that many were convinced it was done by magic. They ruled happily together for years, and as they ruled, the area grew wealthy and fertile, so rich that to the serfs of other lands, the serfs that served Melusine and the count seemed like merchants. Melusine and Raymondin had ten children, all of whom bore some deformity or mark of their birth, but who were strong and thrived, and were beloved of their people.

Raymondin’s brother, out of envy of all they had, whispered in his ear that Raymondin had no idea where his wife went, or whether she was in her chamber at all on Saturdays, and if she was, who knew who else might be there? Perhaps Melusine entertained the Devil himself on Saturdays, as she loathed to visit the cathedrals and often was absent at Mass. The seeds of distrust thus sowed, Raymondin spied on his beloved wife and having seen her turn into a serpent from the waist down, he knew why she wanted privacy on that day.

Silently, he crept away, filled with guilt for his broken promise, and he kept his peace until the day when one of their sons burned another in a rage. When Melusine went to her husband to comfort her, he sent her away, calling her a ‘foul and odious serpent,’ revealing that he had broken his word, and indeed, revealed her secret before his men.

Melusine let out a scream of agony and anger and flew from the place, but sometimes is still seen or heard when the wind blows in just the right way at the Château.

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Melusine and The Enlightenment

Look at me choosing Mélusine as my icon. Love me some pretentious stuff! And the painting...

I put the painting as I wanted something to represent Enlightenment. Not that I preach it, not that I’m a beacon OF it but because I believe in the Enlightenment and the values it preached. That’s all.

Mélusine is there (y’all probably recognise something rather like the Starbucks sign, which she is also on) because I love me some Medieval literature. She’s a really interesting figure, actually though. The story goes that she’s a fairy and is cursed by her mother to turn into a half-fish, half-woman every Saturday. (It’s weirdly specific, I love that!). If she can marry a man who loves her and keeps his promise never to see her in her half-fish form, she will gain full-humanity. Anyway: she marries a man, gives him lots of very prodigious children but keeps her secret. One day, she’s in the bath splashing about with her fish tail when her husband gets really curious as to what his wife does every Saturday, spending it all day in the bathtub. He is led to believe that she uses the excuse to entertain a lover, so he thinks she’s cuckolding him. Anyway he goes and peaks through the keyhole and sees her. This is all from from the book Le Roman de Mélusine by Jean d’Arras by the way, and it’s all really interesting, not least because in seeing his half-fish wife, the husband begins feeling guilty for breaking his promise to never go looking for her in the bathtub. He mentally describes himself as a snake, and so you get this really interesting reflexive thing where he sees a half-human, half-fish transfiguration and then sort of ingests it, figuring himself as another animal in return, not as a fish but as a snake: the Devil’s creature. In that moment, he is more ‘wrong’, more animal, more inhuman, more alien than she is. Anyway, eventually he publicly shames her for her demonic nature and Mélusine turns into a dragon and flies off, wailing, leaving behind her many children for the man to look after: it’s sort of ambiguous as to whether her full transformation is the curse taking full effect or whether she’s also pissed off and jilts him. An interesting point is that it’s stated that the curse will take full effect when the husband breaks his promise, but Mélusine’s husband does this and nothing happens. It’s only when he publicly shames her for it that the curse takes hold... It’s also interesting that she’s cursed by her mother: the problems of inheritance/progeny is quite key to the novel. She’s an icon of Medieval literature, a very interesting female character and super interesting. I just love the story, tbh...

0 notes