#Laura cereta

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

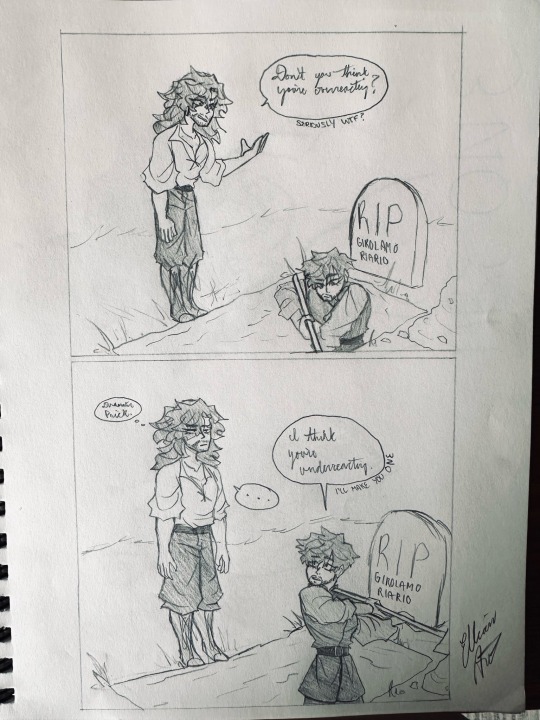

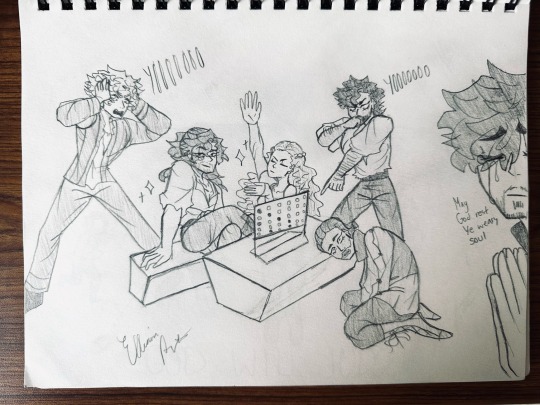

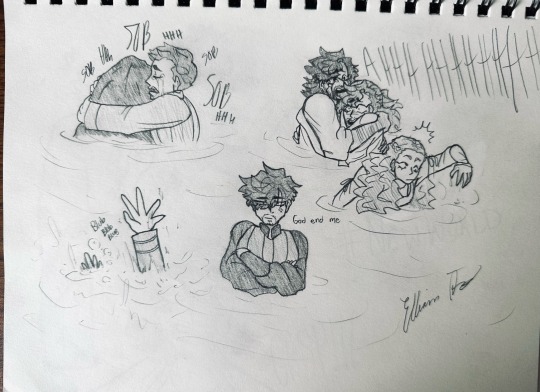

Sketch dump two

#myart#da vinci’s demons#leonardo da vinci#girolamo riario#lorenzo de medici#Vanessa moschella#niccolo machiavelli#Zoroaster da peretola#pope sixtus#vlad dracula tepes#draw the squad#sketch dump#sketch#Laura cereta#lucrezia donati#leario#some weird fuckin ship between Vlad and Girolamo

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

"It is a crafty ploy, but only a low and vulgar mind would think to halt Medusa with honey."-Laura Cereta, “A Defense of the Liberal Instruction of Women”

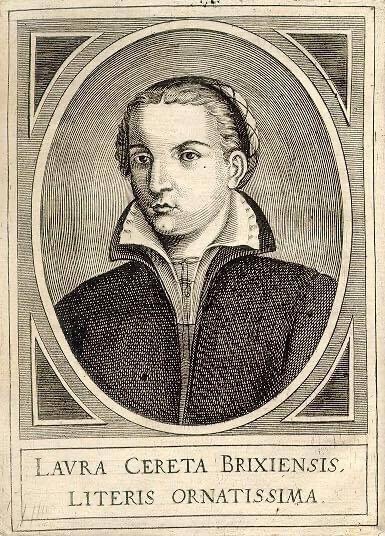

Laura Cereta, imitating the humanist writers of her day, crafted Latin letters in the form of orations and invectives on such themes as marriage and family, education, fate and fortune, solitude, avarice, war, and consolations on death. Like the first great humanist Petrarch, Cereta claimed to seek fame and immortality through her writing. Indeed, it appears that her letters were intended for a general audience -- they were written over a brief period of time (between 1485 and 1488), some of the correspondents were fictitious, and her father sent a number of them to the Dominican friar Tommaso of Milan, who wrote back praising them. Cereta assembled 82 of her letters in a volume, together with a burlesque dialogue on the death of an ass, and dedicated it to her patron, Cardinal Ascanius Maria Sforza, possibly seeking legitimization as a writer. This volume remained unpublished until the seventeenth century, but circulated in manuscript form between 1488 and 1492 among humanists in Brescia, Verona, and Venice.

Because her Latin composition was so good, some intellectuals accused her of plagiarism. One critic even sent his wife to demand proof on the spot of her writing abilities. Faced with such opposition, Cereta responded with one of the finest defenses on the education of women in Quattrocento Italy. In it, she proposes that a woman can be just as learned as a man if she applies herself: "[K]nowledge is not given [to women] as a gift, but [is gained] with diligence" (quoted in Shibanoff 190).

Cereta's life provides a good illustration of the type of dedication she advocated. She was born in Brescia in 1469 to Silvestro Cereto, an attorney and magistrate, and Veronica di Leno, a descendent of an old Brescian family. At the age of seven, Cereta was sent to a convent to learn religious principles and the rudiments of reading and writing. This was not uncommon for girls her age during this period. What appears unusual is that she suffered from insomnia for two years. In her writings, she relates how she spent many sleepless nights in the convent reading and doing embroidery. When she was nine, her doting father brought her home from the convent so she could help care for her younger siblings. She remained accustomed to the habit of staying up late at night after all the chores were done in order to read. In addition to learning Latin and Greek from her father, Cereta also showed great interest in mathematics, astrology, agriculture, and her favorite subject, moral philosophy. At fifteen or sixteen years of age (1484 or 1485), she married a Brescian businessman, Pietro Serina, and unlike most learned women of her time, continued to study just as intensely as before she was married. After eighteen months of marriage, her husband died of a fever (most likely a version of the plague) and Cereta remained childless. She mourned his death but found consolation in her studies. When she was eighteen years old, she delivered her first public oration, and two years later, it is believed by her early biographers that she began a seven year career of teaching moral philosophy, although there are no public records that verify her position as a teacher.

To many scholars, Cereta's early writings combine classical ideals with religious beliefs while her later writings reveal a tension between humanism and religion. Since none of her writings exist from the last eleven years of her life, it is difficult to know what she thought in her later years about linking secular and religious subjects. Perhaps we may assume that Cereta followed the advice of her spiritual advisor, Brother Tommaso, who urged her in multiple letters (1487) to turn from her studies to a greater religious commitment. Following the deaths of her husband and father, the two men who supported her intellectual endeavors, it appears that Cereta struggled to understand and maintain her position as a learned Christian woman in a society that valued women primarily for their domestic and religious involvement.

"My ears are wearied by your carping. You brashly and publicly not merely wonder but indeed lament that I am said to possess as fine a mind as nature ever bestowed upon the most learned man. You seem to think that so learned a woman has scarcely before been seen in the world. You are wrong on both counts, Sempronius, and have dearly strayed from the path of truth and disseminate falsehood…You pretend to admire me as a female prodigy, but there lurks sugared deceit in your adulation. You wait perpetually in ambush to entrap my lovely sex, and overcome by your hatred seek to trample me underfoot and dash me to the earth."

#perioddramaedit#history#edit#history edit#laura cereta#laura cerato#italiansedit#italian history#rinascimento#donne nella storia#donne italiane#donne della storia#renaissance italy#women of renaissance#15th century#scholar#venice#sai bennett#A Defense of the Liberal Instruction of Women#tommaso of milan#humanist#silvestro cereto#italian renaissance#renaissance women#women in history#veronica di leno#pietro serina#feminism#writer#philosophy

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

Me: *studying women's history*

My book: *mentions briefly Cassandra Fedele, Laura Cereta and Isotta Nogarola*

Me: 😍❤️🌺😘💘🧡💖💛💗💚💓💞💌💜💙❣️🖤💟💘😻🤩

#admin's ramblings#admin post#history#post: you may have the universe if i may have italy#studyblr#history studyblr#history major#italian history#renaissance#italian women#cassandra fedele#laura cereta#isotta nogarola

5 notes

·

View notes

Quote

I cannot tolerate your having attacked my entire sex... With just cause I am moved to demonstrate how great a reputation for learning and virtue women have won by their inborn excellence, manifested in every age as knowledge.

Laura Cereta in a letter to a mysoginist critic

4 notes

·

View notes

Conversation

Riario: I'll go back to Florence and hand myself over to Lorenzo.

Laura: Why would you do that?

Riario: Leo isn't here, and he's 85% of my impulse control.

44 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Feminism Quote By Laura Cereta “The free mind, unafraid of labor, presses on to attain the good.” Laura Cereta, - Collected Letters Of a Renaissance Feminist

0 notes

Note

Hi duchess, I've been reading about Isotta Nogarola and Laura Cereta, and I wondered if you know any biography or book that speaks about learned women and scholars in the renaissance? Mostly I see is about royalty or a City of Ladies

Extraordinary Women of the Medieval and Renaissance World : A Biographical Dictionary By Debra Barrett-Graves looks into all successful women both noble, royal and common.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

“…Early humanists almost always arose out of noble families or the upper- middle class and were often tutored at home by older siblings or a humanist father. A family’s social position, public and political influence, and the father’s profession were often directive forces in the education of both female and male children; a girl’s social and family background had important implications for the course of her academic career.

Although women who received a classical education were undoubtedly in the minority, there were humanist fathers who provided the impetus for their daughters’ schooling and fostered their intellectual pursuits. Young girls whose fathers greatly valued education were taught Latin alongside their male siblings and were granted a significant degree of intellectual and social freedom.

As Sarah Ross argues, “the intellectual family” legitimized the first female humanists: learned fathers provided for the classical education of their daughters, which contributed to the family’s intellectual honor and social capital. Highly-educated daughters were seen as their fathers’ intellectual protégées, and although male humanists generally excluded women from public activity, very young girls could give public orations if the intent was to bring virtue and glory to either their family or city.

For instance, as young girls, both Isotta Nogarola and Laura Cereta were praised as erudite rhetoricians and allowed a public platform for their orations; both were regarded as famous adolescent prodigies within northern Italian humanist circles. Some young female scholars such as Cereta were seen as “walking illustrations of their fathers’ pedagogical talents” and received an education, in part, to inflate the intellectual egos of their fathers and increase the social capital of their lineage.

While it is clear that the family, and most notably the father, often played a central role in the formation of a young girl’s education, it is critical to note that “the intellectual family” was a product of the domestic nature of Renaissance education; women were not given opportunities for education outside of the domestic sphere. The domestic nature of humanist training also effectively set up a system in which female education was only legitimate when confined to the domestic sphere under the supervision of a patriarch. As the case studies discussed here illustrate, paternal or patriarchal oversight was critical to academic legitimacy and social acceptance.

For many female humanists, there was a perilous transitory period between their childhood academic training and their role as mature women in society. While I agree with scholars such as Virginia Cox who argue that, “It is not by any means the case that ... there was simply no place for the learned woman in the social environment of ‘Renaissance Italy’ nor that learned women were universally perceived as ‘threats to the natural and social order’ or ‘aroused fear and anger in male contemporaries,’” there does seem to be sufficient historical evidence to suggest that the freedom of youthful study did not fully extend into adulthood and that adult life of study was more socially perilous.

Young women were not yet burdened by the pressures of marriage and motherhood and, as such, were permitted and encouraged to devote time to academic pursuits; unfortunately, the notion of “learned virtue” and professional scholarship as a vocation infrequently applied to adult women. Women who forged successful adult careers did so by securing patriarchal support, which legitimized their continued engagement in humanism. Outside of the tutelage or direction of a patriarchal figure, very few learned women continued with their studies and produced substantive works after the narrow window of youth came to a close.

For most humanist women, two life choices existed: the life of marriage and motherhood, which often meant the abandonment of study, but provided for some level of social participation, or life in a convent, which allowed for continued education, but required a withdrawal from the world and often resulted in oppressive solitude; as Arcangela Tarabotti’s works explain, this cloistered solitude was often determined by a family’s financial circumstance and mandated by a father against his daughter’s will. Although some women successfully established a partial means to continue their studies within the confines of patriarchal society, most who attempted to do so were vilified for going “beyond their sex”.

Virginia Cox argues that, “Female scholars also generated a notable degree of social opprobrium, especially when they came to make the transition from precocious adolescents to adult, sexual women. Social convention, it is claimed, appeared to demand that women set aside their intellectual ambitions on marriage.” Woman who revolted against the patriarchal ideology that female education was a luxury of youth were often either the victims of harsh criticism, like Laura Cereta, or were psychologically and socially wounded by accusations of immorality and unchastity, like Isotta Nogarola. The society which once heralded the child prodigy as glorious now saw the learned woman as threatening.

While the patriarchal social order in large part determined the opportunities afforded to both women and men, it is clear that humanism did catalyze for a shift in ideology regarding the education of girls. Rationalizing the extension of a classical education to girls as a means of civic service, male humanists began to engage young women in a liberal model of education and fostered their intellectual pursuits. While Margaret King is accurate in asserting that in general, “women humanists did not achieve great status in the world of humanism or recognition of intellectual parity of men,” it is important that scholarship not reduce all women to a singular experience; the self- perception and public reception of learned humanist men is not discussed in a monolithic fashion, nor are their contributions to history diminished because of their sex.”

- Julie Myers-Mushkin, "The quality of women's intelligence" : female humanists in Renaissance Italy.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

✨ August Reading List ✨

The Rise and Fall of Adam and Eve: The Story That Created Us, Stephen Greenblatt

Game of Queens: The Women Who Made Sixteenth-Century Europe, Sarah Gristwood

The Symptom and the Subject: The Emergence of the Physical Body in Ancient Greece, Brooke Holmes

Their Eyes Were Watching God, Zola Neale Hurston

Collected Ficciones, Jorge Luis Borges

The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours, Gregory Nagy

Praise of Folly, Erasmus

The Secret History, Donna Tartt

Illuminating the Roman d’Alexandre; Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Bodley 264: The Manuscript as Monument, Mark Cruse

Sister Citizen: Shame, Stereotypes, and Black Women in America, Melissa V. Harris-Perry

The Rival Queens, Nancy Goldstone

Twilight, Stephanie Meyer

Midnight Sun, Stephanie Meyer

The Luminaries, Eleanor Catton

The Priest of Nature: The Religious Worlds of Isaac Newton, Rob Iliffe

Forbidden Friendships: Homosexuality and Male Culture in Renaissance Florence, Michael Rocke

Laura Cereta: Collected Letters of a Renaissance Feminist, trans. and ed. Diana Robin

Along with several varying articles, usually to supplement the book i was already reading, this month was a good one for me actually reading. Due to farm duties and housework I’m not sure if September will be as well read (as well as me possibly - finally - getting an interview for work). However, I would greatly appreciate recommendations!

#bookblr#studyblr#august reading list#books#recommendations#book recommendations#literature#academia#dark academia#light academia#renaissance#history#sociology#anthropology#english#alchemy#sciences#history of science#fiction#nonfiction#summer reading#book review?

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Laura Cereta (1469-1499) Venetian. Humanist scholar. In lectures & essays she critiqued misogyny, explored women’s contributions to political/intellectual life, argued against marriage slavery & for women’s education. “My ears are wearied by your carping” she said to detractors.

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

top five famous historical figures you headcanon Joe/Nicky have met OR if you want a list outside TOG maybe top five ships excluding TOG?

ohhhhh ok I’LL DO BOTH! thank you <3333

five famous historical figures you headcanon Joe/Nicky have met

*i am not a historian

1. the obvious choice here, shakespeare 2. catherine the great 3. joan of arc 4. laura cereta 5. sojourner truth

top five ships outside of tog:

1. steve/bucky (marvel) 2. clary/isabelle (tmi and shadowhunters) 3. angel/buffy (btvs) 4. carmen/shane (the l word) 5. brian/justin (queer as folk)

3 notes

·

View notes

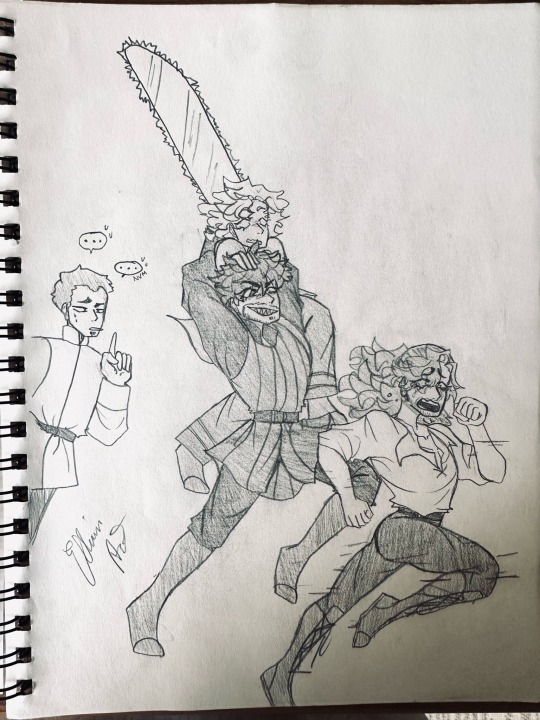

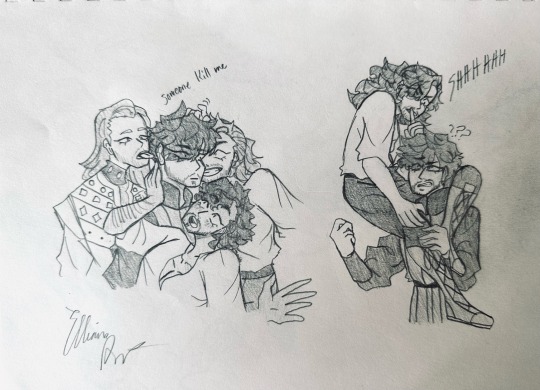

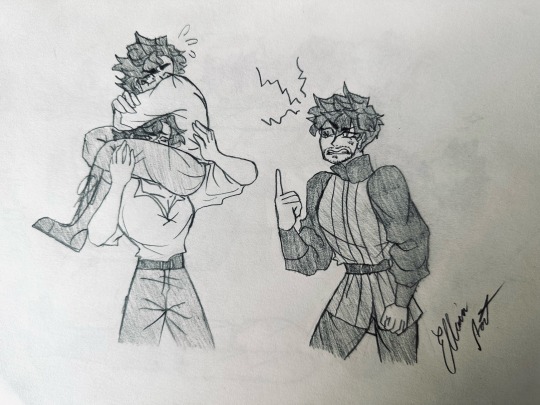

Text

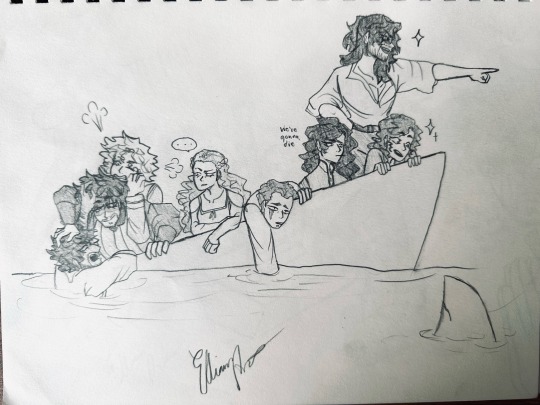

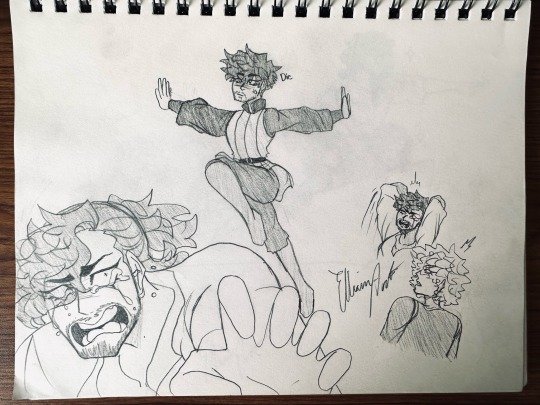

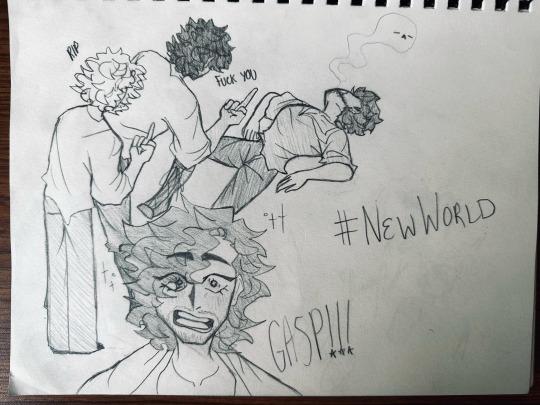

Sketch book dump of my current hyperfixation

#myart#da vinci’s demons#girolamo riario#leonardo da vinci#lorenzo de medici#Vanessa moschella#niccolo machiavelli#Zoroaster da peretola#vlad dracula tepes#draw the squad#Laura cereta#lucrezia donati#francis della rovere#pope sixtus#Aslan Al-Rahim#sketch#sketch dump#Sophia da Vinci

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

can you tell me about cereta?

oh boy i would love to!

laura cereta was a fifteenth century italian writer, born to parents who were both famous and successful - her father a lawyer, her mother a businesswoman - and she was the embodiment of renaissance humanism as well as one of the earliest feminist scholars of the western world. she was seven years old when she was sent to a convent for education. by twelve, she was learned and accomplished in mathematics, astrology, agriculture, moral philosophy, latin, drawing, embroidery, and religious studies.

at fifteen, she married, and her letters to her husband show just how outspoken and intelligent she was. she never stopped or slowed her own education, she made it clear that her marriage was founded and contingent on mutual respect and open communication, and she - to coin a phrase - took no shit. her husband died less than two years after they were married, and she never had children or remarried.

she dedicated herself to her writings, which mostly took the form of letters written to general audiences - though sometimes addressed to a likely fabricated name - spanning a great range of topics. some of these letters were written as if in direct response to criticism she received, in bold and unforgiving language, eviscerating the opposition with her sharp wit, brilliant argumentation, and vivid diction.

she wrote in defense of not only herself, but the inherent potential of women, asserting that she was not an exceptionally intelligent woman, not a remarkable outlier in her intellect, but only in her actions. women had always been intelligent and talented, she said, and she drew on classical sources as evidence, citing a wealth of women from myth and religion as well as women in history, from sappho to pyromantia to zenobia.

of course, there's a lot to be said for her position in society giving her the freedom to undertake her intellectual pursuits, as she was well off and her endeavors were supported and nurtured by her father, but ultimately, she was correct: the thing that set her apart from the other women in her socioeconomic sphere was not an astounding level of innate ability, but that she chose to prioritize herself and her education, and that she chose to speak out against injustice.

in closing, some selected quotes of hers:

[...] you who are no longer now a man of animus but instead a stone animated by the scorn you have for the studies that make us wise [...]

lesbian sappho serenaded the stony heart of her lover with tearful poems, sounds i might have thought came from orpheus' lyre or the plectrum of phoebus.

your mouth has grown foul because you keep it sealed so that no arguments can come out of it that might enable you to admit that nature imparts one freedom to all human beings equally - to learn.

for a mind free, keen, and unyielding in the face of hard work always rises to the good, and the desire for learning grows in depth and breadth.

i am a scholar and a pupil who has been lulled to sleep by the meager fire of a mind too humble. i have been too much burned, and my injured mind has accumulated too much passion.

i am not a woman who wants the shameful deeds of insolent people to slip through under the pardon of silence.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

Like we’re gonna die young

Laura Cereta died at the young age of 30 in 1499, young even for the time. This fits the trend of the gone-too-soon but brilliant artist, a la Jean-Michel Basquiat or Amy Winehouse. These deaths always beg the question: how much art did we miss out on? Cereta’s intentions were never disguised in abstruse words, but meant for a general audience, as she sought fame and acclaim. This simplicity made her sharp tongue all the more biting and singular, as her words hit home to all that could read them. According to Margaret King, Cereta’s writing career lasted only three years, probably before she had turned 20. Why would such a ambitious mind quit us so early on? We ponder this in regard to fallen young artists, but their deaths often adds to their acclaim. Laura Cereta was honored with a state funeral in Brescia, a rare honor for a woman of the time. Perhaps her death inspired more reverence for her work amongst her peers, much like the deaths of our favorite modern artists do for us.

4 notes

·

View notes

Quote

My thirsty soul seeks revenge, my sleeping pen is aroused to literary struggle, raging anger stirs mental passions long chained by silence.

Laura Cereta (1469-1499)

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

scorpion-flower watches Da Vinci's Demons 10x3

Okay,we have seen Leonardo sword-fighting before, but seeing Nico and Cereta doing the same is kinda weird 😜

#Scorpion-flower#Da vinci's demons#Leonardo da vinci#Niccolo machiavelli#Laura cereta#Fandoms#We were the kings and the queues

0 notes