#Kumari Naaz

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

"For Mine is one of those lives Lit by a measly light Each morning Barely enough To last the day And the day Even this light plays truant"

Enchanted Silence - Meena "Naaz" Kumari

0 notes

Text

Remembering Nalini Jaywant, one of Hindi cinema's most versatile and beautiful actresses of yesteryears, on her 98th birth anniversary today (18/02/1926). Blessed with an extraordinarily serene face, as innocent as a cherub's, Nalini Jaywant was a huge star in the early fifties. Along with Suraiya, Nargis, Madhubala and Meena Kumari, she was right at the top. Making her debut in the 1941 film ‘Bahen', Nalini Jaywant was first noted in the 1948 hit, ‘Anokha Pyaar', a love triangle that also featured Dilip Kumar and Nargis. She had to die in the end and there was a not a dry eye among the audience. Her first major hit was ‘Samadhi' with Ashok Kumar, a pairing which lasted for 12 more films. It was also remembered for the jazzy number, ‘Gore Gore O Baanke Chhore'. Among her other successful movies with Ashok Kumar, were ‘Sangram', ‘Nau Bahar,' ‘Kafila', ‘Mr X' and ‘Naaz' which was shot mostly in Egypt. The star was much in demand for her versatility, which she exhibited in light, romantic films with an entertaining music score such as ‘Munimji,' ‘Hum Sab Chor Hain', ‘Naujawan' and ‘Jadoo'. Mo wonder, she was accorded the No 1 female star status in 1954 and a 1950 Filmfare poll judged her as the ‘Most beautiful star of the Year.' ‘Kala Pani' fetched her a Filmfare Award. Nalini appeared in around 60 films, ‘Bombay Race Course' -released in 1956- was her last as heroine. Though Nalini made a comeback in 1983 in ‘Nastik' as hero Amitabh Bachchan's mother, later she simply disappeared from the movie scene, the media and public glare. In the end, her long years of film stardom did not matter, and no one seemed to care. On 20, December 2010, Nalini Jayawant died of a heart attack, alone and forgotten in a small bungalow in Mumbai's Chembur suburb, where she had lived in seclusion for more than two decades.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Meena Kumari in “Chalte chalte yunhi koi” (“Pakeezah”, 1972)

youtube

Meena Kumari (1933-1972), one of the greatest Indian actresses of the last century, in an iconic scene and song from the classic Indian movie Pakeezah (The Pure One-1972, written, directed, and produced by Kamal Amrohi).

Meena Kumari plays in this movie Sahibjaan, a tawaif. The tawaifs were courtesans who catered to the nobility of the Indian Subcontinent in the Mughal and post-Mughal eras and were trained in music, danse, theater, and Urdu literature. An orphan, Sahibjaan lives since her childhood in a kotha (brothel), but she wants to escape from her fate.

According to the website of the University of Iowa ( https://indiancinema.sites.uiowa.edu/pakeezah ):

““I’ve seen your feet; they’re very lovely. Don’t set them down on the earth—they’ll get soiled.” This metaphorical warning-note, penned by a romantic stranger and left between the toes of a sleeping woman in a railway compartment, forms a much-underscored motif in this classic courtesan film—the final collaboration between the great actress and dancer Meena Kumari and her former husband, actor and director Kamal Amrohi. Like MOTHER INDIA, this film coexists with its own legend involving the offscreen lives of the director and star, who planned it together in the late 1950s but whose marriage broke up around the time that filming began in 1964. Kumari (who was also a talented Urdu poet under the pen name Naaz) then purportedly became an alcoholic, but eventually came back to complete the film shortly before her premature death in 1972; aficionados may try their luck at identifying—from Kumari’s pained and sometimes mask-like face—which scenes were shot when. The central theme of the film is the struggle for respectability of a tawai’if, an Indo-Islamic courtesan trained in poetry, music, and dance—a glamorous “public woman” whose career was to be an elegant companion (and potential lover) to affluent men, but for whom a “respectable” marriage and home was out of the question. Her beautiful feet—apart from being an erotic fetish—represent her mastery of the art of North Indian classical dance or Kathak, which tawai’if’s preserved and nurtured for several centuries. The “earth” that such feet must perforce touch, however, is ruled by patriarchal society with its crippling double-standards, which decreed that respectable women (who lived in parda or seclusion) could seldom be interesting to men, and that interesting women were seldom respectable. All courtesan fiction struggles with this divide, which forms a principal theme of one of the earliest and most famous Urdu novels, Mirza Mohammed Hadi Ruswa’s UMRAO JAN ADA (1905; itself later filmed several times; see notes on UMRAO JAAN). PAKEEZAH offers another variation on the theme.”

See also about Pakeezah the paper of Richard Allen and Ira Brashkar Pakeezah: Dreamscape of Desire, on https://www.academia.edu/36264030/Pakeezah_Dreamscape_of_Desire

In the iconic scene of this video Sahibjaan/Meena Kumari sings and dances for the “villain” of the movie, an aristocrat (Nawab) named Zafar Ali Khan (played by Kamal Kapoor), who wishes to own her. The ambiguities and dynamics of the situation and of the relationship between the two are depicted in excellent way in this scene, which takes place at the Gulabi Mahal (Pink Palace) of Luchnow. According to the paper of Allen and Brashkar:

“The Gulabi Mahal (the Pink Palace) at Lucknow evokes a more rarified atmosphere. In Amrohi’s imagination, the space of the kotha is here fused with the idea of a Greek temple where the central colonnaded performance space doubles as a space of worship to the divine feminine, and discrete spaces are orchestrated in a theatrical hierarchy from the outer court with its fountains at the entrance to the inner sanctum sanctorum, which houses the bedroom of the courtesan, essentially off limits to all but the chosen client, and separated from the main performance space by a lighted causeway between reflecting pools of water.The Pink Palace is a sublime temple of femininity, whose fountains, atriums, reflecting pools form a microcosm of artifice that rivals that of the natural world. Indeed, even the moon appears artful in this landscape and the saturated deep blue sky, a studied backcloth to the whole.”

But, as the same article continues a bit further, the Pink Palace is also a prison for Sahibjaan:

“Meanwhile, for Sahibjaan whose desire for self-fulfillment has been awakened, the Pink Palace becomes a prison. In a metaphor that recurs in the film, and echoes throughout the genre, she is likened to a bird in a gilded cage from which she yearns to escape...

...The quality and texture of her performances for him [the Nawab] are now markedly different from her earlier ones. Gone is the vivacity and vibrancy of an Inhin logon ne or a Thade rahiyo as she mournfully sings the haunting Chalte Chalte, which articulates her desire for freedom and happiness.Yet it also returns us to the pathos of her entrapment in a manner that evokes the equation of the courtesan and the flickering flame that opens the film. At the conclusion of the performance, as she sings Yeh chiraag bujh rahein hain / Mere saath jalte jalte (These lamps are fading / As they burn with me), she hears the screech of a train whistle. It is impossible initially to discern whether it is somewhere physically off-screen or within her mind.The camera cranes upward from the floor to the red chandelier, recalling the red aalta of her feet.The lights darken as the escalating screech of the train whistle resounds through the performance space, taking over the song and abruptly bringing the dance to an end. When the camera cranes down again, the dancers have disappeared from the floor.The camera then tracks forward towards the fountains that abruptly stop playing as the whistling ends. It is as if the space in which she dwells, her erstwhile tomb, is now cut to the measure of her desire. She rushes to the balcony to see the train she has seen before, but this time it is motionless, silhouetted against the sky, almost as if waiting for her to come to her balcony before it can leave.Though real, the train appears as if in a vision, so detached is the spectacle from the space she inhabits.What is finally required for Sahibjaan to escape her sealed world is a transformation of environment and character of a magnitude that challenges the tone in which the film has hitherto been cast.”

The lyrics of Chalte chalte yuhni koi were written by the Urdu poet Kaifi Azmi (1919-2002) and its music was composed years before the release of Pakeezah by Ghulam Mohammed (1903-1968). Although Meena Kumari was also a singer, the voice in the song is of the great Indian singer Lata Mangeshkar (1929-2022).

Unfortunately I couldn’t do anything with the advertisements at the end of the video.

I have found on the net the following transliteration and translation of the lyrics of Chalte chalte yuhni koi:

Chalte chalte, chalte chalte While walking, while walking

Yun hi koi mil gaya tha I met someone by chance

Yun hi koi mil gaya tha I met someone by chance

Sare raah chalte chalte Walking around the path

Sare raah chalte chalte Walking around the path

Wahin thamke reh gayi hai Right there it stood still

Wahin thamke reh gayi hai Right there it stood still

Meri raat dhalte dhalte This night of mine, which is fading away

Meri raat dhalte dhalte This night of mine, which is fading away

Joh kahi gayi na mujhse What I was unable to say

Joh kahi gayi na mujhse What I was unable to say

Woh zamaana keh raha hai The world is saying that

Woh zamaana keh raha hai The world is saying that

Ke fasana A story

Ke fasana ban gayi hai A story has been created

Ke fasana ban gayi hai A story has been created

Meri baat chalte chalte From those words of mine

Meri baat chalte chalte From those words of mine

Yun hi koi mil gaya tha I met someone by chance

Yun hi koi mil gaya tha I met someone by chance

Sare raah chalte chalte Walking around the path

Sare raah chalte chalte Walking around the path

Yun hi koi mil gaya tha I met someone by chance

Sare raah Around the path

Chalte chalte, chalte chalte While walking, while walking

Sare raah Around the path

Chalte chalte, chalte chalte While walking, while walking

Chalte chalte, chalte chalte While walking, while walking

Yun hi koi mil gaya tha I met someone by chance

Yun hi koi mil gaya tha I met someone by chance

Shab-e-intezaar aakhir The night of waiting

Shab-e-intezaar aakhir The night of waiting

Kabhi hogi mukhtasar bhi Will after all shorten soon

Kabhi hogi mukhtasar bhi Will after all shorten soon

Yeh chirag These lamps

Yeh chirag bujh rahe hai These lamps are dying

Yeh chirag bujh rahe hai These lamps are dying

Mere saath jalte jalte As they burn alongside me

Mere saath jalte jalte As they burn alongside me

Yeh chirag bujh rahe hai These lamps are dying

Yeh chirag bujh rahe hai These lamps are dying

Yeh chirag bujh rahe hai These lamps are dying

Yeh chirag bujh rahe hai These lamps are dying

Yeh chirag bujh rahe hai These lamps are dying

Yeh chirag bujh rahe hai These lamps are dying

Mere saath jalte jalte As they burn alongside me

Mere saath jalte jalte As they burn alongside me

Yun hi koi mil gaya tha I met someone by chance

Yun hi koi mil gaya tha I met someone by chance

Sare raah chalte chalte Walking around the path

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

BOLLYWOOD’S TOP 108 FEMALE DANCERS OF ALL TIME (@INDIES) !

1. .Helen

2. .Ragini

3. .Padmini

4. .Mumtaz

5. .Reena Roy

6. .Jaya Prada

7. .Rajni Bala

8. .Madhuri Dixit

9. .Aishwarya Rai bachchan

10. .Meenakshi Sheshadri

11. .Shraddha Kapoor

12. .Hema Malini

13. .Vyjyanthimala

14. .Saira Banu

15. .Meena Kumari

16. .Waheeda Rehman

17. .Geeta Bali

18. .Zeenat Aman

19. .Sandhya

20. .Sridevi

21. .Asha Parekh

22. .Anita Guha

23. .Kumkum

24. .Sadhana

25. .Nanda

26. .Faryal

27. .Madhubala

28. .Shyama

29. .Saroja Devi B.

30. .Nishi

31. .Nalini Jaywant

32. .Mala Sinha

33. .Bina Rai

34. .Minoo Mumtaz

35. .Laxmi Chhaya

36. .Shahzadi

37. .Anita Raj

38. .Kimi Katkar

39. .Kaajal Kiran

40. .Rekha

41. .Kanan Kaushal

42. .Nutan

43. .Leena Chandavarkar

44. .Rati Agnihotri

45. .Tanuja

46. .Nadira

47. .Bindiya Goswami

48. .Bindu

49. .Padma Khanna

50. .Divya Bharti

51. .Jamuna

52. .Aruna Irani

53. .Jayshree Talpade

54. .Heera Rajgopal

55. .Zeb Rehman

56. .Meena Talpade

57. .Parveen Babi

58. .Kim

59. .Asha Sachdev

60. .Raakhee

61. .Ameeta

62. .Naaz

63. .Tina Munim

64. .Neelam

65. .Farha

66. .Simran

67. .Cuckoo

68. .Gitanjali

69. .Jeevan Kala

70. .Nalini Chonkar

71. .Naazima

72. .Jayshree Gadkar

73. .Sadhona Bose

74. .Meena Shorey

75. .Jamuna (Lady Tarzan)

76. .Nagma

77. .Meera Madhuri (Maan Maryada)

78. .Vandana Rane (Maan Maryada)

79. .Barkha (Rakhi aur Rifle)

80. .Alka Noopur

81. .Sitara Devi

82. .Prema Narayan

83. .Sudha Chopra

84. .Leena Das (Haqeeqat 1985)

85. .Anjali Jathar

86. .Padmini Kapila

87. .Seema Biswas

88. .Neelam (Mahal 1949)

89. .Nimmi

90. .Kammo

91. .Prabha Sharma

92. .Kamala Lakshman

93. .Roshan Kumari

94. .Surinder Kaur

95. .Madhu Malini

96. .Rupini

97. .Rajshree

98. .Jyothi Laxmi

99. .Preeti Sapru

100. .Sudha Chandran

101. .Rani (Cobra Girl 1963)

102. .Kathana (Shikari 1963)

103. Aruna (Daag 1973)

104. Sheela Vaz

105. .Sheela Naik

106. .Leela Pandey

107. .Indira (Dil Deke Dekho)

108. Debashree Roy .

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Meena Kumari (lahir dengan nama Mahjabeen Bano, lahir 1 Agustus 1933[1][2] – meninggal 31 Maret 1972 adalah seorang aktris film India, penyanyi, dan penyair dengan nama pena Naaz,[3] yang membintangi film-film klasik Bollywood. Dikenal sebagai The Tragedy Queen, Chinese Doll,[4] dan Female Guru Dutt,[5] dia sering diingat sebagai Cinderella film India.[6] Ia aktif antara tahun 1939-1972.

0 notes

Photo

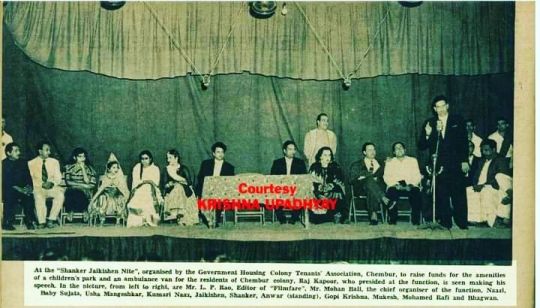

Another feather in cap of #ShankarJaikishan Another benevolent nite presented by the Maestros of the Millennium Now read the caption : At the "Shanker-Jaikishen nite", organised by the Government Housing Colony Tenants' Asscociation Chembur, to raise funds for the amenities of a children's park and an ambulance van for the residents of Chembur colony, Raj Kapoor, who presided at the function, is seen making his speech. In the picture, from left to right, are Mr. L. P. Rao, Editor of "Filmfare", Mr. Mohan Bali, the chief organizer of the function, Naazi, Baby Sujata, Usha Mangeshkar, Kumari Naaz, Jaikishen, Shanker, Anwar (standing), Gopi Krishna, Mukesh, Mohamed Rafi and Bhagwan #shankarjaikishannite #benevelonce #lprao #mohanbali #naazi #babysujata #ushamangeshkar #kumarinaaz #shankarjaikishan #shankerjaikishen #anwarhussain #gopikrishna #mukesh #mohammedrafi #bhagwan (at Bansdroni Pirpukur) https://www.instagram.com/p/Cpu4_EdPghT/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#shankarjaikishan#shankarjaikishannite#benevelonce#lprao#mohanbali#naazi#babysujata#ushamangeshkar#kumarinaaz#shankerjaikishen#anwarhussain#gopikrishna#mukesh#mohammedrafi#bhagwan

0 notes

Photo

Kaagaz Ke Phool (1959, India)

Almost a quarter of the way through the twenty-first century, globalization has pierced the remotest corners of the planet. The examples academics and politicians cite demonstrating this globalization are almost always economic, but the most profound examples are cultural. Once known only in South Asia, Indian cinema has burst onto a global stage. Its stars and its most popular directors seem larger than life. Reading on some of modern Bollywood’s (Hindi-language cinema) personalities, I find few of their biographies compelling beyond their unquestionable status as South Asian and international celebrities – I won’t name names here because that is for another time. That is partly a result of not watching enough Bollywood films. It is also because I am making unconscious comparisons between those modern actors to actor-director Guru Dutt. Dutt was a tragic romantic – off- and on-screen – to the point where those personas can become indistinguishable.

As an actor, Dutt can be as charming a romantic male lead as anyone, as well as lend a film the dramatic gravitas it needs. As a director, he refined his sweeping visuals and theatrical flairs over time. That artistic development culminated with Pyaasa (1957) and his final directorial effort, Kaagaz Ke Phool (“Paper Flowers” in English). The latter film is the subject of this piece. Both films elevate themselves to a cinematic altitude few movies anywhere, anytime ever accomplish. They are, for lack of a better word, operatic* – in aesthetic, emotion, storytelling, tone. In Kaagaz Ke Phool, Dutt once again lays bare his artistic soul in what will be his final directed work.

An old man enters a film studio’s empty soundstage, climbs onto the rafters, and gazes wistfully at the darkened workspace below. We learn that this is Suresh Sinha (Dutt), a film director whose illustrious past exists only in old film stock. The film is told in flashback, transporting to a time when his marriage to Bina (Veena) is endangered – the parents-in-law disdain his film work as disreputable to their social class – and he is embarking upon an ambitious production of Devdas (a Bengali romance novel that is among the most adapted pieces of Indian literature to film, the stage, and television). He is having difficulty finding someone to play Paro, the female lead. Due to this conflict, Bima has also forbidden their teenage daughter, Pammi (Kumari Naaz), from seeing Suresh. Pammi is sent to a boarding school far from Delhi (where Bima and her parents reside) and further from Mumbai (where Suresh works), without any sufficient explanations of the spousal strife.

One rainy evening, Suresh generously provides his coat to a woman, Shanti (an excellent Waheeda Rehman). The next day, Shanti arrives at the film studio looking to return the coat. Not knowing anything about film production, she accidentally steps in front of the camera while it is rolling – angering the crew who are tiring of yet another production mishap. Later, while viewing the day’s rushes, Suresh casts Shanti as Paro after witnessing her accidental, but remarkable, screen presence. She achieves cinematic stardom; Suresh and Shanti become intimate. When the tabloid gossip eventually reaches Mumbai and Pammi’s boarding school, it leads to the ruin of all.

What did you expect from an operatic film – a happy ending?

Also starring in the film are Johnny Walker (as Suresh’s brother-in-law, “Rocky”) and Minoo Mumtaz (as a veterinarian). Walker and Mumtaz’s roles are vestigial to Kaagaz Ke Phool. Their romantic subplot is rife with the potential for suggestive humor (she is a horse doctor), but the screenplay never justifies their inclusion in the film.

Shot on CinemaScope lens licensed by 20th Century Fox to Dutt’s production company, Kaagaz Ke Phool is Dutt’s only film shot in letterboxed widescreen. From the onset of his directorial career and his close collaboration with cinematographer V.K. Murthy, Dutt exemplifies an awesome command of tonal transition and control. Murthy’s dollying cameras intensify emotion upon approach: anguish, contempt, sober realization. These techniques render these emotions painfully personal, eliminating the necessity of a few lines of dialogue or supplemental motion from the actor. The effect can be uncomfortable to those who have not fully suspended their disbelief in the plot or the songs that are sung at the time. But to the viewers that have accepted that Dutt’s films exist in a reality where songs about infatuation, love, loss, and regret are sung spontaneously (and where revelations are heard in stillness), this is part of the appeal. Dutt and Murthy’s lighting also assists in directing the narrative and setting mood: a lashing rainstorm signaling a chance meeting that seals the protagonists’ fates, the uncharacteristically film noir atmosphere of the soundstage paints moviemaking as unglamorous, and a beam of light during a love melody evokes unspoken attraction. That final example represents the pinnacle of Dutt and Murthy’s teamwork (more on this later).

As brilliant as his films (including this) may be, Dutt suffered during mightily during Kaagaz Ke Phool’s production. In writings about Dutt, one invariably encounters individuals who believe Dutt’s life confirms that suffering leads to great art. Though I think it best to retire that aphorism so as not to romanticize pain, I believe that the reverse is true with Guru Dutt – his later directing career contributed to his personal tribulations. In some ways, that suffering informed his approach to what I consider an informal semiautobiographical trilogy of his films: Mr. & Mrs. ’55 (1955), Pyaasa, and Kaagaz Ke Phool. Dutt directed and starred in each of these films. In each film he plays an artist (a cartoonist, poet, and film director, respectively); with each successive film his character begins with a greater reputation, only to fall further than the last. The three Dutt protagonists encounter hardship that do not discriminate by caste, professional success, or wealth.

For Dutt’s Suresh, he is unable to consummate his love for Shanti because the specters of his failed marriage haunt him still. He never speaks to his de facto ex, but marital disappointment lingers. Why does he bother visiting his stuffy in-laws when he knows they will never change their opinions about him? Abrar Alvi’s (the other films in the aforementioned informal Dutt-directed trilogy, 1962’s Sahib Bibi Aur Ghulam) screenplay is silent on the matter. Also factoring into Suresh’s hesitation is his daughter, Pammi. Pammi is young, looks up to both her parents, and cannot fathom a parent being torn from her life. Her reaction to learning about Shanti implies that neither of her parents have ever truly talked to her about their separation. Pammi does not appear to blame herself, but it seems that her parents – intent on protecting their child, perhaps speaking to her not as a soon-to-be young adult – are loath to maturely talk about the other. In a sense, Pammi has never mourned her parents’ marriage as we see her deny the tabloid reports about Suresh’s affair and express anger towards her father when she learns the truth.

When Suresh’s film after Devdas flops, his film career is in tatters. But Shanti’s popularity is ascendant, creating a dynamic reminiscent of A Star is Born. In a faint reference to Devdas, Kaagaz Ke Phool’s final act contains anxieties about falling into lower classes. If Kaagaz Ke Phool is contemporaneous to its release date, one could also interpret this as concerns about falling within India’s caste system (reformist India in the late 1950s was dipping its toes into criminalizing caste discrimination, which remains prevalent). Suresh’s fall is stratospheric and, in his caste-conscious, masculine pride, he rejects Shanti’s overtures to help him rebuild his life and film career. This tragedy deepens because Shanti’s offer is in response to the contractual exploitation she is enduring. We do not see what becomes of Shanti after her last encounter with Suresh, but his final scenes remind me, again, of opera: the male lead summoning the strength to sing (non-diegetically in Suresh’s case) his parting, epitaphic thoughts moments before the curtain lowers.

Suresh’s and Shanti’s respective suffering was preventable. Whether love may have assuaged his self-pity and alcoholism and her professional disputes is debatable, but one suspects it only could have helped.

Composer S.D. Burman (Pyaasa, 1965’s Guide) and lyricist Kaifi Azmi (1970’s Herr Raanjha, 1974’s Garm Hava) compose seven songs for Kaagaz Ke Phool – all of which elevate the dramatics, but none are as poetic as numbers in previous Dutt films. Comments on two of the most effective songs follow; I did not find myself nearly as moved by the others.

“Dekhi Zamane Ki Yaari” (roughly, “I Have Seen How Deeply Friendship Lies”) appears just after the opening credits, as an older Suresh ascends the soundstage’s stairs to look down on his former domain. The song starts with and is later backed by organ (this is an educated guess, as many classic Indian films could benefit with extensive audio restorations as trying to figure out their orchestrations can be difficult) and is sung non-diegetically by Mohammed Rafi (dubbing for Dutt). A beautiful dissolve during this number smooths the transition into the flashback that will frame the entire film. That technique, combined with “Dekhi Zamane Ki Yaari”, prepares the audience for what could be a somber recollection. However, this is only the first half of a bifurcated song. The melodic and thematic ideas of “Dekhi Zamane Ki Yaari” are completed in the film’s final minutes, “Bichhde Sabhi Baari Baari” (“They All Fall Apart, One by One”; considered by some as a separate song). Together, the musical and narrative arc of this song/these songs form the film’s soul. For such an important musical number, it may have been ideal to incorporate it more into the film’s score, but now I am being picky.

Just over the one-hour mark, “Waqt Ne Kiya Haseen Sitam” (“Time Has Inflicted Such Sweet Cruelty On Us”; non-diegetically sung by Shanti, dubbed by Geeta Dutt, Guru’s wife) heralds the film’s second act – Suresh and Shanti’s simultaneous realization of their unspoken love, and how they are changed irrevocably for having met each other. Murthy’s floating cameras and that piercing beam of light are revelatory. A double exposure during this sequence shows the two characters walking toward each other as their inhibitions stay in place, a breathtaking mise en scène (the arrangement of a set and placement of actors to empower a narrative/visual idea) foreshadowing the rest of the film.

Dutt’s perfectionist approach to Kaagaz Ke Phool fueled a public perception that the film was an indulgent vanity exercise with a tragic ending no one could stomach viewing. Paralleling Suresh and Shanti’s romantic interest in each other in this film, the Indian tabloids were printing stories claiming that Dutt was intimate with co-star Waheeda Rehman and cheating on Geeta Dutt. These factors – perhaps some more than others (I’m not versed on what Bollywood celebrity culture was like in the 1950s, and Pyaasa’s tragic ending didn’t stop audiences from flocking to that film) – led to Kaagaz Ke Phool’s bombing at the box office. Blowing an unfixable financial hole into his production company, Guru Dutt, a man who, “couldn’t digest failure,” never directed another film. Like the character he portrays here, Dutt became an alcoholic and succumbed to depression in the wake of this film’s release. Having dedicated himself entirely to his films, he interpreted any professional failure as a personal failure.

Kaagaz Ke Phool haunts from its opening seconds. Beyond his home country, Dutt would not live to see his final directorial effort become a landmark Bollywood film and his international reputation growing still as cinematic globalization marches forth. Dutt’s most visually refined films, including Kaagaz Ke Phool, are films of subtraction. The cinematography and music make less movement and dialogue preferable. Kaagaz Ke Phool is a film defined about actions that are not taken and scenes that are never shown. The result is not narrative emptiness, but a receptacle of Dutt’s empathy and regrets. Exploring these once-discarded, partially biographic ideas is not for faint hearts.

My rating: 9/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating. Half-points are always rounded down. My interpretation of that ratings system can be found in the “Ratings system” page on my blog (as of July 1, 2020, tumblr is not permitting certain posts with links to appear on tag pages, so I cannot provide the URL).

For more of my reviews tagged “My Movie Odyssey”, check out the tag of the same name on my blog.

* I use this adjective not to reference operatic music, but as an intangible feeling that courses over me when watching a film. Examples of what I would consider to be operatic cinema include: Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000, Taiwan); Greed (1924); The Red Shoes (1948); and The Wind (1928). Some level of melodrama and emotional unpackaging is necessary, but the film need not be large in scope or have musical elements for me to consider it “operatic”.

#Kaagaz Ke Phool#Guru Dutt#Waheeda Rehman#Kumari Naaz#Bollywood#Mehmood#Johnny Walker#Mahesh Kaul#Veena Sapru#Abrar Alvi#V.K. Murthy#S.D. Burman#Mohammad Rafi#Geeta Dutt#Asha Bhosle#My Movie Odyssey

40 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“Kaagaz Ke Phool” / 1959 / Waheeda Rehman and Kumari Naaz

#Waheeda Rehman#Kumari Naaz#Baby Naaz#Old Bollywood#1959#1950s#Indian Cinema#Bollywood2#Bollywood#Vintage Bollywood#lobby cards#role: Shanti#Kaagaz Ke Phool

22 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Seems as if we finally can enjoy a decent quality version of “Kaagaz Ke Phool” (1959, dir. Guru Dutt))! (I strongly recommend youtube channel tommydan55 for watching classic Indian cinema anyway.)

“Kaagaz Ke Phool” has Guru Dutt himself, Waheeda Rehman, Johnny Walker, Minoo Mumtaz, Veena, Mahesh Kaul and Kumari “Baby” Naaz in the lead roles.

Screenplay by Abrar Alvi, lyrics by Kaifi Azmi and Shailendra, music by S.D. Burman, main singers are Geeta Dutt and Mohd. Rafi.

The breathtakingly beautiful and poignant cinematography is by V.K. Murthy (who also has a cameo appearance as assistant director of photography). It was India’s first film in CinemaScope. There is also a second version filmed with conventional lense, as only very few cinemas were able to screen a letterbox movie in those days.

#Kaagaz Ke Phool#Guru Dutt#Old Bollywood#1959#1950s#video#Indian Cinema#Bollywood2#Bollywood#Vintage Bollywood#Waheeda Rehman#Johnny Walker#Minoo Mumtaz#Veena#Mahesh Kaul#Baby Naaz#kumari naaz#abrar alvi#Kaifi Azmi#Shailendra#Geeta Dutt#Mohd Rafi#VKMurthy

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Kumari Naaz in Dhool Ka Phool (1959)

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

How can I explain to the heart that the night is about to pass? All the conversation is about the night—but the night is about to pass.

Meena Kumari Naaz

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

پوچھتے ہو تو سنو کیسے بسر ہوتی ہے

رات خیرات کی، صدقے کی سحر ہوتی ہے

سانس بھرنے کو تو جینا نہیں کہتے یا رب!

دل ہی دُکھتا ہے نہ اب آستیں تر ہوتی ہے

جیسے جاگی ہوئی آنکھوں میں چبھیں کانچ کے خواب

رات اس طرح دوانوں کی بسر ہوتی ہے

غم ہی دشمن ہے مرا، غم ہی کو دل ڈھونڈتا ہے

ایک لمحے کی جدائی بھی اگر ہوتی ہے

ایک مرکز کی تلاش ایک بھٹکتی خوشبو

کبھی منزل کبھی تمہیدِ سفر ہوتی ہے

مینا کماری ناز

#urdu#urdu poetry#urdu shayari#urdu ghazal#urduadab#urdu literature#pakistan#urdu poem#pakistani#urdu quote#urdu shairy#urdu writing#poetry#shayari#meena kumari#مینا کماری ناز#meena kumari naaz

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Zindagi yeh hai to phir maut kise kahte hain? Pyar ik khwab tha, is khwab ki ta’bir na pooch Kya mili jurme-wafa ki hame’n ta’zir na pooch

If this is life, what is it that they call death? Love was a dream. Ask not about the fate of this dream. Ask not about the punishment I received for the crime of loyalty.

- Meena Kumari Naaz

34 notes

·

View notes

Quote

टुकड़े-टुकड़े दिन बीता, धज्जी-धज्जी रात मिली जिसका जितना आँचल था, उतनी ही सौगात मिली रिमझिम-रिमझिम बूँदों में, ज़हर भी है और अमृत भी आँखें हँस दीं दिल रोया, यह अच्छी बरसात मिली जब चाहा दिल को समझें, हँसने की आवाज़ सुनी जैसे कोई कहता हो, ले फिर तुझको मात मिली मातें कैसी घातें क्या, चलते रहना आठ पहर दिल-सा साथी जब पाया, बेचैनी भी साथ मिली होंठों तक आते आते, जाने कितने रूप भरे जलती-बुझती आँखों में, सादा-सी जो बात मिली

मीना कुमारी

9 notes

·

View notes