#Kirstin Butler | American Experience

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

'We Are In The Worst Crisis We Have Known Since The Civil War'

When the city of Detroit went up in flames in 1967, it was the most deadly civil uprising of the century

— May 15, 2024 | Kirstin Butler | American Experience

Troops on Detroit’s Linwood Avenue in 1967. © Tony Spina/Detroit Free Press via ZUMA Press.

The frame brims with human emotion: fear, dismay, resignation. Defiance. A Black man stares down three white armed National guards, his arms crossed and hip cocked. Smoke clouds the sky above them. This particular street scene in July 1967 was captured in Detroit, but it might have been taken in so many of the 150 cities where racial strife consumed the country that same year. Urban uprisings across the United States resulted in scores of deaths and millions of dollars of damage; entire city blocks were reduced to rubble. “The simple fact is this: We are in the worst crisis we have known since the Civil War,” said a television journalist in September of that year.

The roots of Detroit’s discontent went back decades. Blacks came to the city en masse during the Great Migration, growing from a population of around 5,000 in 1910 to 480,000 in 1960. That nearly 100-fold increase, however, wasn’t accompanied by expanding opportunity. Restrictive redlining practices consigned them to only a few neighborhoods, meaning a third of the city’s population lived in overcrowded, substandard housing. Black Detroiters also had fewer economic opportunities. They struggled to get work that paid as well as their white counterparts, and as the city began to lose jobs with the collapse of the automotive industry, Blacks were often the first fired. And the community’s relationship with the Detroit police had long been fraught, with Black residents on the brunt end of disproportionately harsh treatment.

In these conditions—de facto segregated housing, schooling, employment, and a history of police brutality—Detroit resembled other inner cities that had already erupted in protest in the years leading up to 1967. In 1964, the Harlem and Bedford Stuyvesant sections of New York broke out in violence after a white police officer shot and killed a Black 15-year-old. The next year, 1965, civil unrest consumed the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles for nearly a week after a run-in between residents and police; 1966, more uprisings in Chicago and Cleveland followed the same pattern. And before Detroit combusted in mid-summer 1967, already 33 cities were in turmoil, with Newark, New Jersey suffering worst so far. In that city, white police officers beat a Black cab driver in full view of a public housing project. Twenty-six people died in the six days of public uproar and official crackdown that followed.

All of these urban rebellions made one thing clear: racism wasn’t just a southern problem. “We think of the civil rights movement and Jim Crow, the heart of it being in the South,” notes UC Berkeley professor john a. powell [sic]. “But you had cities all across the country up in flames. And those reactions to the continued oppression of blacks, it was never just spontaneous. It was always responding to some state-formed oppression.”

“Those Reactions To The Continued Oppression of Blacks, It Was Never Just Spontaneous. It Was Always Responding To Some State-Formed Oppression." — John A. Powell

These currents were all swirling in Detroit. In June, a Black Vietnam veteran had been killed by a gang of white youths after he took his pregnant wife to a public park bordering a white neighborhood. Then, in the early hours of July 23rd, the police broke up a party taking place at an illegal social club in a predominantly Black neighborhood on the city’s west side; the building doubled as headquarters for the United Community and Civic League, a local activist group. The club’s patrons had gathered to celebrate the return of two veterans from Vietnam, but instead found themselves being shoved roughly into paddy wagons. As the arrests continued, a large crowd gathered, protesting the officers’ treatment of the arrestees; someone eventually threw a brick at a police cruiser. Others joined in with bottles and sticks. Someone smashed the window of a nearby store, and looting began. Fires spread. By the next day, flames had devastated entire blocks.

Law enforcement responded harshly. “You cannot fight violent criminals with non-violent methods,” said a spokesperson for the Detroit Police Officers Association. “We had a war and I think you have to attack a war with warlike weapons and under warlike conditions.” Michigan governor George Romney called in the National Guard. Its young, untrained guardsmen, however, fomented more chaos. Five days later, 43 people had died, with hundreds more injured—at the time the most deadly civil uprising of the century.

Even as Detroit still burned, Johnson announced the formation of a presidential commission to study the chaos engulfing the country. He posed three questions to its 11 members: ‘What happened? Why did it happen? What can be done to prevent it from happening again?’ Led by Gov. Otto Kerner Jr. of Illinois, the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders—known colloquially as the Kerner or Riot Commission—conducted an on-the-ground assessment in 23 cities where disturbances had taken place, including Detroit. It interviewed 1,200 witnesses and officials, including residents, mayors, police chiefs and Black Power representatives.

The commission was a nearly all-male, all-white panel, and yet when it issued its final analysis, it offered a sweeping statement about the origins of the tinder stoking each urban conflagration. “Segregation and poverty have created in the racial ghetto a destructive environment totally unknown to most white Americans,” read the report’s introduction. “What white Americans have never fully understood—but what the Negro can never forget—is that white society is deeply implicated in the ghetto. White institutions created it, white institutions maintain it, and white society condones it.”

Ultimately, however, few of its recommendations for addressing these structural forces were implemented. “The Kerner Commission comes down and concedes that the country is broken,” professor powell told American Experience, “and that we should make rapid and radical change.” Yet, as is often the case with presidential commissions, political exigencies—in this case, the ire of white voters who ultimately elected law-and-order candidate Richard Nixon to the presidency—consigned its findings to history, rather than to the future.

“We’ve had many lost opportunities,” powell observes, while still noting the report’s ongoing relevance. “Kerner Commission—at best—is an opportunity postponed. I think if we do move forward, we will have to come back to that commission.”

#Kirstin Butler | American Experience#Detroit#Worst Crisis#Civil War#Reactions | State-Formed | Oppression#John A. Powell#From the Collection | A Thousand Words#The Riot Report | Article#Thirteen | PBS

0 notes

Photo

The PBS program American Experience, which documents interesting events and people from American history, recently ran an episode on the lie detector test — something that William Moulton Marston, the co-creator of Wonder Woman, falsely claimed to have invented. This webcomic by Kirstin Butler and Derrick Dent details Marston’s many endeavors over the years, from his attempts at creating a an early polygraph prototype to the female hero he helped create with artist H.G. Peters.

Read more

#american experience#pbs#wonder woman#William Moulton Marston#webcomics#sunday comics#kirstin butler#derrick dent#lie detector test

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

How Codebreaker Elizebeth Friedman Broke Up a Nazi Spy Ring

https://sciencespies.com/history/how-codebreaker-elizebeth-friedman-broke-up-a-nazi-spy-ring/

How Codebreaker Elizebeth Friedman Broke Up a Nazi Spy Ring

Armed with a sharp mind and nerves of steel, Elizebeth Smith Friedman (1892–1980) cracked hundreds of ciphers during her career as America’s first female cryptanalyst, successfully busting smugglers during Prohibition and, most notably, breaking up a Nazi spy ring across South America during the 1940s.

But until records detailing her involvement in World War II were declassified in 2008, most Americans had never heard of Friedman. A man—then-director of the FBI J. Edgar Hoover—took credit for Friedman’s wartime success, and she took her secret life as one of the country’s top codebreakers to the grave.

Those eager to learn more about Friedman’s extraordinary accomplishments can now watch a new documentary, “The Codebreaker” on PBS’ “American Experience,” for free online. Based on journalist Jason Fagone’s 2017 nonfiction book, The Woman Who Smashed Codes, the film also draws on Friedman’s archival letters and photographs, which are held by the George C. Marshall Foundation.

As Suyin Haynes reports for Time magazine, the PBS documentary arrives amid a surge of interest in Friedman: In 2019, the United States Senate passed a resolution in her honor, and in July 2020, the U.S. Coast Guard announced that it would name a ship after her.

youtube

Born into a Quaker family in Huntington, Indiana, in 1892, Friedman studied poetry and literature before settling down in Chicago after graduation. A devoted Shakespeare fan, she visited the city’s Newberry Library to see a 1623 original edition of the playwright’s First Folios, wrote Carrie Hagan for Smithsonian magazine in 2015.

There, a librarian impressed by Friedman’s interest put her in touch with George Fabyan, an eccentric millionaire seeking researchers to work on a Shakespeare code-cracking project. She moved to Fabyan’s estate at Riverbank Laboratory in Geneva, Illinois, and met her future husband, William Friedman. The pair worked together to attempt to prove Fabyan’s hunch that Sir Francis Bacon had written Shakespeare’s plays, filling the texts with cryptic clues to his identity. (Years later, the couple concluded that this hunch was incorrect).

When World War I broke out, Fabyan offered the government the assistance of the scholars working under his guidance at Riverbank. The Friedmans, who wed in 1917, became leaders in the first U.S. codebreaking unit, intercepting radio messages and decoding encrypted intelligence.

Though Friedman never formally trained as a codebreaker, she was highly skilled at the process, historian Amy Butler Greenfield tells Time.

Butler Greenfield adds, “She was extraordinarily good at recognizing patterns, and she would make what looked like guesses that turned out to be right.”

After World War I, the U.S. Coast Guard hired Friedman to monitor Prohibition-era smuggling rings. She ran the unit’s first codebreaking unit for the next decade, per Smithsonian. Together, she and her clerk cracked an estimated 12,000 encryptions; their work resulted in 650 criminal prosecutions, and she testified as an expert witness in 33 cases, reports Time.

All told, wrote Hagan for Smithsonian, “[Friedman’s] findings nailed Chinese drug smugglers in Canada, identified a Manhattan antique doll expert as a home-grown Japanese spy, and helped resolve a diplomatic feud with Canada.”

Friedman succeeded in her field despite significant barriers associated with her gender: Though they both worked as contractors, she earned just half of what her husband made for the same work, according to Smithsonian. After the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, the Navy took over Friedman’s Coast Guard unit and essentially demoted her. (Women would only be allowed to serve fully in the military after 1948, notes Kirstin Butler for PBS.)

Elizebeth Friedman, right, with her husband, William. Though William earned fame as a cryptologist during his lifetime, Elizebeth’s achievements have only come to light in recent years, when documents detailing her achievements were declassified.

(Public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

Friedman achieved her greatest code-breaking feat in the 1940s. Working for the Coast Guard, she led a team that eavesdropped on German spies as they discussed the movement of Allied ships in South America. This was high-stakes business: As Americans fought in World War II, they feared that Axis powers would attempt to conduct Nazi-backed coups in several countries in South America, per PBS.

In 1942, Friedman’s worst fear materialized. Cover transmissions from the Nazis abruptly stopped—a sign that her targets had discovered they were being spied on. As it turned out, FBI director Hoover, eager to make a career-defining move, had tipped off Nazi spies to the U.S.’ intelligence activities by hastily raiding sources in South America.

Then 49, Friedman was left to deal with the aftermath, which PBS’ Butler describes as the “greatest challenge of her career.”

Adds Butler, “Even after Hoover’s gambit set her efforts back by months, Friedman’s response was what it had always been: She simply redoubled her efforts and got back to work.”

Eventually, Friedman and her team used analog methods—mostly pen and paper—to break three separate Enigma machine codes. By December 1942, her team had cracked every one of the Nazi’s new codes. In doing so, she and her colleagues unveiled a network of Nazi-led informants led by Johannes Sigfried Becker, a high-ranking member of Hitler’s SS. Argentina, Bolivia and Chile eventually broke with Axis powers and sided with the Allied forces, largely thanks to Friedman’s intelligence efforts, according to Time.

Friedman’s husband, William, earned recognition during his lifetime and is credited by many as the “godfather of the NSA,” an organization that he helped to shape in its early years, Fagone tells Jennifer Ouellette of Ars Technica.

His wife, meanwhile, “was a hero and she never got her due,” says Fagone to Time.

“She got written out of the history books,” Fagone continues. “Now, that injustice is starting to be reversed.”

#History

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

There Was an Underground Magazine for Transgender Women in the 1960s! Transvestia's Archives Provide a Window onto a Hidden World

— June 22, 2023 | Kirstin Butler & Casa Susanna | Article | American Experience

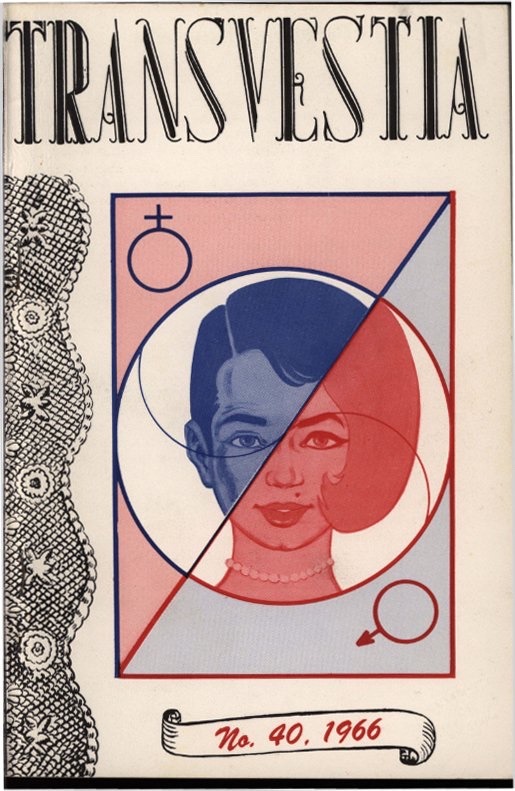

The cover of the August 1966 issue of Transvestia magazine.

In the first month of a new decade, a Los Angeles chemist named Virginia Prince mailed out the inaugural issue of a magazine. It was, as the title page of the January 1960 edition of Transvestia states, a privately printed journal “with three objectives: to provide EXPRESSION for those interested in the subjects of exotic and unusual dress and fashion; to provide INFORMATION to those who, through ignorance, condemn that which they do not understand,” and, finally, “to provide EDUCATION for those who see evil where none exists.” With these oblique statements, Prince launched what would become the first long-running periodical for male-to-female crossdressers and transgender women in the United States.

Over its 25-year print run, Transvestia grew from 25 initial subscribers to several hundred distributed across the U.S. Most readers received their bi-monthly issues through the mail, though after 1963 the magazine could also be found in alternative and adult bookstores and newsstands in major American cities. Prince was the magazine’s driving force and served as editor until 1979, but Transvestia’s contents were as much by its readers as for them. Subscribers submitted life histories, letters, editorials, book reviews and photographs of themselves. They had their own jargon: “TV” for transvestite, “GG” for “genetic girls,” “brother” for their male identities and the “girl-within,” to refer to their feminine selves; some readers also used “femmepersonator” or “FP” for short. Prince also reprinted medical papers on topics such as gender identity and the psychology of cross-dressing.

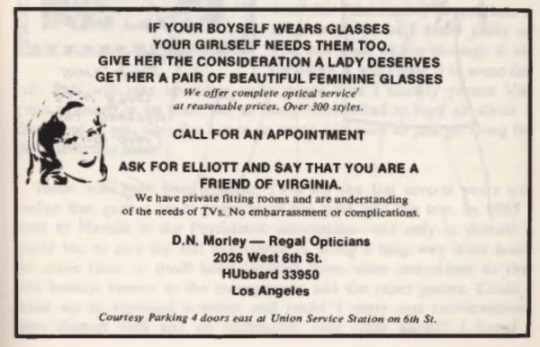

Each issue typically ran around 80 pages, with several dedicated to advertisements for various goods—self-published books, custom undergarments and wigs—and services such as electrolysis and makeup consultation. “Perhaps there are no good stores in your town. Perhaps you are too well known,” offered one advertisement for a personal shopper. “Perhaps you need an unusual size and would be embarrassed to ask for it. Whatever the reason, I can help.” Every issue also contained a “Person to Person” section where subscribers could connect with one another. “Lifelong TV, married, 34, scientist, welcomes all correspondence with all TV’s foreign or domestic,” reads a listing by Barbara, a reader from southern New England, in the December 1965 issue.

An optician’s ad in Transvestia’s October 1969 Issue.

Transvestia was an outlet for creative writing as well. A piece of fiction in the magazine’s first issue told the story of a married couple enjoying a night out, both husband and wife dressed in traditionally feminine attire: “The sound of my high heels matching hers, the sight of my frock swirling beside hers, made us feel as one…sensing the fragrance of the real woman so close to me, the distinction between ‘man’ and ‘woman’ vanished like smoke in a high wind.” Prince herself contributed a poem to that issue, composing on a theme that would recur in many other editions of the magazine—the relief experienced upon transforming from masculine to feminine archetypal expectations and presentation.

Poems in the January 1960 and March 1961 issues of Transvestia.

In fact, several subjects appeared with a great deal of regularity throughout Transvestia’s pages. Dr. R.S. Hill, a professor at Concordia University, authored a seminal study of the magazine as his dissertation. Reflecting on Transvestia’s most oft-recurring content, Dr. Hill wrote, “The letters and histories endlessly elaborated on the same themes and topics: theorizing the causes of their condition; crossdressing for the first time; overcoming obstacles to free expression; dealing with guilt, fear, or loneliness; disclosing to or hiding from parents, wives, and children; venturing out in public; passing successfully as women without public detection; describing articles of clothing, wardrobes, and bodily measurements; and sharing fashion and make-up advice.”

Through the magazine, Transvestia readers forged a group consciousness, united not just by mutual interests but also for their common demography: The majority of subscribers were white, middle-to-professional-class, and considered themselves heterosexual. Most were married and had children. Some spoke of cross-dressing as just a relaxing “hobby” they occasionally enjoyed. But a substantial number would come to identify as women over the course of the journal’s publication, including Prince herself as well as contributing editor Susanna Valenti. Prince wrote about that decision in her final issue as editor in 1979, saying, “I figured that since I had learned pretty much all I needed to know about being a man in this world, that I might just as well devote the rest of my life to exploring the other side of my own humanity…That was in June of 1968 and I have lived as Virginia ever since.”

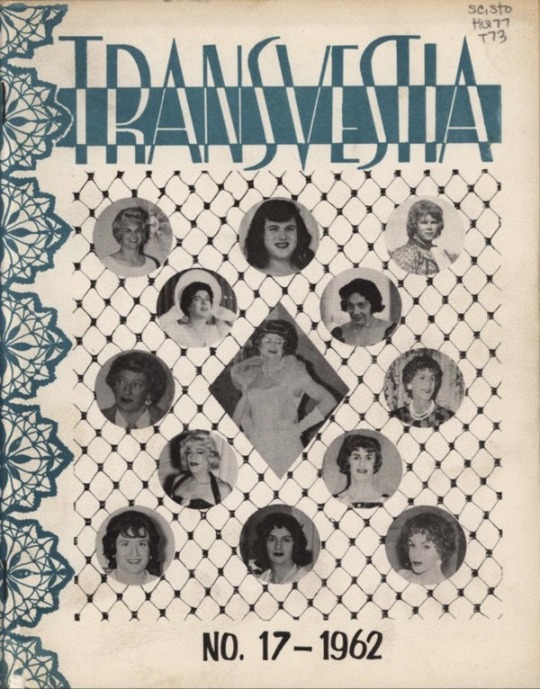

All of the magazine’s readers agreed that the practice of cross-dressing allowed them to access their most vibrant selves. “I have been married, have fathered five children, and am about to become a Grandpa any day now,” said the magazine’s 1962 covergirl Eileen in an accompanying personal history. “The men I work with are all hairy chested so-and-so types, and have accepted me into their ranks without question. Yet, when I rush home from the office and enter my own world of delight, that is when I truly live.”

Transvestia subscriber Eileen graced the cover of the magazine's August 1962 Issue.

The Publisher

Having been through a great deal of pain, fear, guilt, loneliness and frustration in my life I wanted to help others to avoid or conquer these feelings. My tool for doing this has been Transvestia.” — Virginia Prince, Transvestia, Vol. 3 No. 16, August 1962

Born in 1912, Virginia Prince was the highly opinionated, often irascible godmother of Transvestia’s print pages and its extended real-life network. After launching the magazine, she also founded a national sorority for other crossdressers in 1962 called Phi Pi Epsilon—or FPE, which also stood for Full Personality Expression. This later became Tri-Ess, or the Society for the Second Self, an international crossdressing organization that still exists to this day. Prince frequently gave interviews to American and international media and liaised with medical professionals about the practice of cross-dressing.

The magazine’s “Person to Person” section was restricted to FPE sorority members to ensure correspondents’ safety.

Prince’s primary goal was to destigmatize cross-dressing; and she utilized the magazine as well as FPE to create a conservative bulwark against other, competing forms of transgender life and community in the United States in the 1960s. “Prince wanted to socialize individual ‘deviance,’” said Dr. Hill, “to place transvestism within a group context, domesticate it, and normalize it by promoting the radical idea that transvestites were not immoral, sexual deviants but rather normal, respectable citizens with only a harmless gender variation.” Even the name of Prince’s regular column in the magazine, “Virgin Views,” was part of her plan to de-eroticize a lifestyle that included cross-dressing by linking it to connotations of purity.

Already within a year of Transvestia’s genesis, Prince had assumed the role of self-appointed moral arbiter. “We must keep our own house clean and above reproach,” she asserted in the magazine’s March 1961 issue. In a repressive Cold War context where heteronormative standards reigned, that meant distancing cross-dressing from other gender and sexual subcultures: “We all know that the world confuses transvestism and homosexuality and when there is a campaign against the latter we are caught in the crossfire.” Prince asked readers to police themselves and each other, saying, “you come into the future of the magazine, not just by way of financial support and contributions of material, but by being a watchdog too.”

Prince’s column in the December 1965 issue included her portrait.

As part of her desire to domesticate transvestism, Prince also sought out and published writings by transvestites’ female partners. Some were tender—thus supporting Prince’s respectability campaign—as in an account from a wife about her husband’s transformation to “Betty Lynn, the Blonde Bombshell.” “I can’t understand why anyone wouldn’t want another dimension to their love,” wrote Fran. Still, the majority of Transvestia readers spoke of fraught negotiations around their cross-dressing, sometimes ending in the dissolution of marriage.

The narrative Prince espoused through Transvestia initially held that the goal of transvestism should be an exercised balance of masculine and feminine identities, with each having its own separate opportunity for expression. “[T]ry to employ perspective in seeing FemmePersonation as an adjunct to your masculine personality, not a substitute for it,” she suggested in her August 1962 “Virgin Views” column. “Transvestia does not exist for the purpose of impairing or destroying the masculine but rather to allow those who are aware of their feminine side to extract the full benefits from it. We can experience some of the feminine side of life, express part of our personality that way, and be better persons and citizens for it IF we…keep the whole matter in balance and under control.”

She advised against medical interventions such as hormone therapy and what was then known as sex reassignment surgery, saying, in 1965, “I realized that surgery would be a form of suicide not only for my masculine self but for Virginia too since it would cut the ground (as well as other things) out from under her…being a woman some of the time is wonderful, having to be one all the time would not be half as great as it seems to be from a distance.” As Dr. Hill writes, “‘transsexuality’ is everywhere in Transvestia as a category against which the ‘true transvestites’ defined themselves.”

Transvestia’s October 1962 cover featured photos of its first two years of cover models—“The composite cover of 12 livin’ dolls.” Prince’s is the largest photo in the center.

Over the coming years, however, Prince’s position would shift from this earlier dichotomous gender model to an identity where one’s masculine and feminine selves were merged into an integrated whole. “[V]ery little in life is tied up hard and fast with the fact that one is male or female,” she wrote in the August 1966 issue, adding “that the ideas of man and woman and masculine and feminine are cultural inventions for all their assumed usefulness.” Her views on gender had gradually become more flexible.

By June 1968, Prince had come to a decision to live full-time as a woman. Assembling the magazine, she said later, was what had allowed her to arrive at that turning point. “In trying to help you, my readers, I have learned and grown myself,” she wrote in the magazine’s 100th anniversary issue in 1979, which was largely dedicated to “The Life and Times of Virginia,” her personal history. “I am now a whole person, completely self accepting and at ease…[M]y best hopes and good wishes to all of you—may you, too, find the acceptance and the internal peace that we all need, and with that I say farewell.”

Susanna Says

“But Enough of Philosophising…Let's Gossip!” — “Susanna Says,” Transvestia, Vol. 7 No. 40, August 1966

Where Virginia Prince was Transvestia’s reigning West Coast intellectual, Susanna Valenti, the magazine’s contributing editor, was its East Coast bon vivant. Her regular column, “Susanna Says,” contained social news, fashion tips and advice, all served up with attitude and pointed humor. “I most certainly have particular people in mind whenever I unsheath a journalistic claw,” she wrote in February 1963, in response to what some readers deemed her “cattish remarks.” “Where would the fun be,” she protested, “if people could not see themselves mirrored in the printed page?”

For Valenti, criticism also had a noble purpose. She offered cosmetic and comportment tips—informing her readers about the right ways to walk, how to soften their voices and what pressed powders to wear—because those elements would allow them to more safely present to a world threatening arrest and violence. “Sorry, my friends, to sound so mean,” she demurred in that same column. “[S]omebody has to pour out a bucketful of cold, merciless realism, just to remind ourselves that the world is not entirely made of pretty clouds and blue skies. There’s also mud and hard pavement under our feet.” If being “read”—common community parlance for being discovered while dressed—was the greatest danger, and “passing”successfully as female would ensure their protection, then Valenti would scold Transvestia subscribers into shape.

Virginia included this image of herself and Susanna in Tranvestia’s 100th anniversary Issue.

“[P]resent as smooth an image as possible,” “Susanna Says” advised in 1965. “In some areas there's nothing we can do about—height, skeletal frame, feet, hands, muscles, etc—but in those areas where something can be done, there's just no excuse if we don't at least make an effort.” Valenti spoke at length about her own efforts: wardrobe alterations, dance classes and diets. For her, moral improvement could be achieved by means of aesthetic perfection—and why not enjoy oneself doing it? “The real fun about being a TV,” she proclaimed, “is in the CONSTANT IMPROVING.”

The April 1965 issue continued a feature that spanned several editions called “What Should I Wear?” and contained tutorials on wardrobe color, shape and style, including guides to neckline types and hem lengths.

Like Prince, Valenti had a significant community presence both on and off the page. In the very first issue of Transvestia, she announced that she and her wife Marie were opening a private retreat at their property in the Catskill Mountains catering specifically to Transvestia’s audience; the “Chevalier d’Eon Resort” was named after an 18th-century French crossdressing spy. “Change clothes as many times as you want, stay inside or go out—in short, do as you please and ‘LIVE.’ Even hairdressing help will be available,” promised the announcement. “What more can you ask? This sounds more like fiction than a lot of fiction, but it's real!” Indeed, over the next decade, Marie and Susanna would run what eventually became the eponymous “Casa Susanna,” which became the East Coast hub for crossdressers and a burgeoning transgender community.

Valenti, who had adopted Prince’s script against transitioning, also came to change her position with the changing times. She announced her own decision to live full-time as a woman in Tranvestia’s October 1969 issue. “I’ve ceased feeling that fabulous thrill of the change itself,” Valenti said of her part-time transitions back and forth from Susanna to her male identity. “It’s only fabulous in one direction: from HIM to HER. But the reverse from HER to HIM, is becoming more and more painful. It actually depresses me… To be ‘her’ is quite different. Energy seems to flow into me from all directions, and no matter what activity I engage in, I never seem to tire…I cannot speak of thrills, but of a peace and contentment that I find nowhere else.”

Susanna Valenti announced a momentous personal decision in her column for the October 1969 Issue.

Still, her final words in the magazine were more equivocal. A decade later, in 1979, Valenti reprised her column once more at Prince’s request for the centennial issue. “One hundred years! Or is it one hundred issues of TVia?” Valenti mused. “It really seems like a century ago we started groping in the confusion of our lives for a truth and a self-definition. We followed the same pattern that modern youth seems to have found, the eternal question of ‘who am I’?” Then she took stock of the gains Transvestia had won for her community, saying, “We seem to have moved forward to a certain extent. A good number of people, many more than there were one hundred issues ago, know about us. The moral ‘liberation’ of our times seems to have helped somewhat, too.

“But,” she concluded, “we ask ourselves, have we really become liberated? Have we really become understood? Accepted?”

#American Experience#Transgender Women#Underground Magazine#Transvestia's Archives#Hidden World 🌎#Kirstin Butler & Casa Susanna#Publisher#Philosophising#Susanna Valenti

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Scenes from Nazi Summer Camp

In the years leading up to WWII, children across the United States spent their summers learning archery and antisemitism.

— January 18, 2024 | Kirstin Butler

Children at a German American Bund camp stand at attention as the American flag and the Bund youth flag are lowered in a sundown ceremony in Andover, N.J., July 21, 1937. Associated Press.

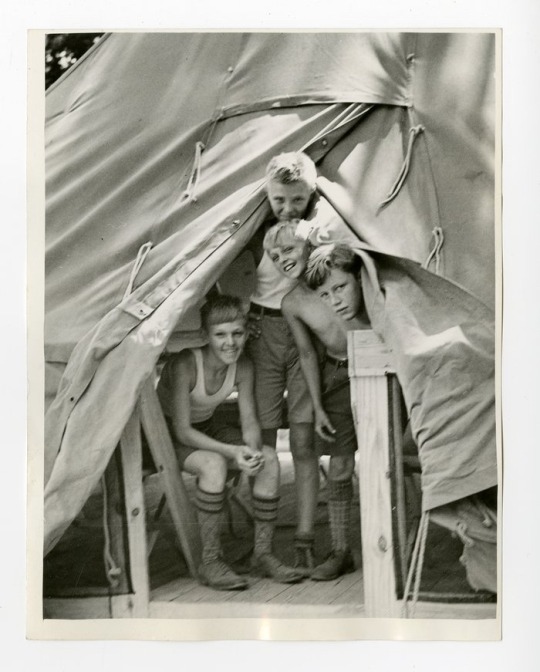

Camp Wille und Macht—Will and Might—came first, in 1934, and was joined in New Jersey by Camp Nordland in Andover and Camp Bergwald in Bloomingdale. In Wisconsin, Camp Hindenberg claimed ground along the banks of the Milwaukee River, and children left their homes for Camp Siegfried in Long Island, the Deutschhorst Country Club in Pennsylvania and Sutter Camp in Los Angeles, California. Photographs and footage from the 1930s document those children pitching tents, cooking baked beans, hiking and singing songs. “It looks like any kind of Boy Scout camp or Girl Scout camp,” author Arnie Bernstein told American Experience. “But these were Nazi camps in America.”

The camps were owned and operated by the German American Bund, a pro-Nazi organization formed by U.S. citizens of German descent in the years leading up to World War II. With scores of chapters and thousands of members across the country, the Bund promulgated an antisemitic, isolationist agenda that sought to establish Nazi ideology in the new homeland. An important part of Bund policy was the creation of a program modeled after the Hitler Youth, the Nazi movement for young Germans. Bund parents enrolled children as young as six into the Jungvolk, which at age 14 split into the Jugendschaft for boys and Mädchenschaft for girls. The Bund camps became the main site for their indoctrination.

Most of the camps were located in New Jersey, New York and Pennsylvania, but others sprouted up in locations like Michigan, Illinois, Wisconsin and California, with an estimated 15 to 25 camps distributed across the country, most in communities with a large German diaspora. Campers were dressed in uniforms featuring the Hitler Youth’s lightning bolt insignia, adorned with swastika pins and given knives inscribed with the phrase “Blut und Ehre,” or “blood and honor.” Daily activities also took on militaristic tones, including target practice and the Sieg Heil salute.

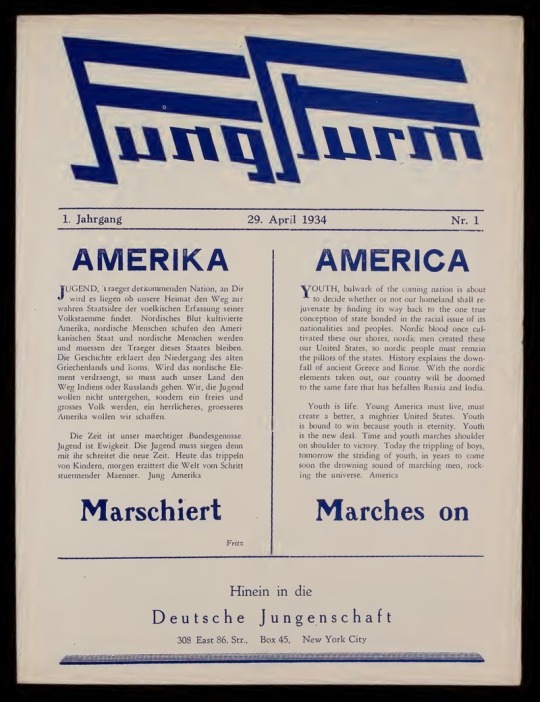

The Bund also published a German-language magazine for its youth members—first called Jung Sturm and then Junges Volk—whose pages featured campers’ accounts and photo spreads dedicated to selective parts of the camp experience. Not depicted, however, were activities that later became public knowledge—like forced nighttime marches that culminated in fireside renditions of the Nazi anthem—after an erstwhile camper testified in 1939 before the House Committee on Un-American Activities. (HUAC was originally formed in part to address concerns about the Bund, as well as other Fascist and Communist organizations in the U.S.) Its leader was ultimately charged with embezzlement, and the group’s assets were seized; some of its leaders and members deported. As the Bund’s troubles multiplied and membership dwindled, the camps closed.

But many of the camps’ archives survived, as did, presumably, children’s recollections of their time spent there and the messages that accompanied it. “It was an experience, a trip, that will remain in our memories forever,” Adirondacks camp director Gregor wrote in Junges Volk.

Four young boys peek out of their tent at the Deutschhorst Country Club, a recreational Bund site outside of Sellersville, Pennsylvania. July 26, 1937, Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

“The German Youth Association will be opening a camp this summer… I’m looking forward to what we’re going to do. We’ll go swimming, play soccer, do gymnastics, go on rides, tell stories, go for walks, do outdoor activities and play lots and lots of games. And now the best part: get up at 6:30 a.m. tomorrow morning and bathe in ice-cold water.” - Edgar, 11, camper in Jungsturm

Bund youth raise a flag at half mast in tribute to Nazi Germany’s late President Hindenburg in Griggstown, New Jersey, August 1934. Getty Images.

“The bugle wakes you up for morning exercise, washing and raising the flag. After the stars and stripes and the camp flag have been hoisted, the pennants are put in their places, the daily motto is announced and a new camp day begins, filled with work and pleasure until curfew.” - Anita, 14, camper, in Junges Volk

The cover page of the inaugural issue of the Bund youth newsletter, first called Jungsturm. Image courtesy Leo Baeck Institute.

Bund youth group boys parade at Camp Siegfried, the largest Bund camp located in Yaphank, Long Island, in 1936. Alamy.

Female members of the Bund youth march at Camp Siegfried. The lightning bolt, or “sieg” rune, was the emblem of the Hitler Youth, and was meant to symbolize victory. 1936, Alamy.

“Just watch those long columns march past, their gaily colored flags flying in the breeze, their strong, tanned legs keeping time to the roll of the long drums, and you shall realize the value of the camp: training ground for the generation of tomorrow. This new generation used to the rigors of camp-life with its long marches, its lonely sentinel duty, its life in the open by rain and storm and hot, burning sun, will be fit to carry on the resurrection of the German in America.” - Paul M. Ochojski, Junges Volk columnist

The summer 1937 issue of the Bund youth magazine featured a gallery of images from its various camp sites—”unsere Jugendlager”—across the country. Image courtesy Leo Baeck Institute.

“We stayed at this fabulous lake for another week and a half, shot wild game and climbed the highest mountains, before it was time to go home. It was an experience, a trip, that will remain in our memories forever. Our youth group has been going to this wonderful mountain range for four years now to set up a summer camp there.” - Gregor, camper, in Jungsturm

Bund youth movement children give a Nazi salute onstage during a German Day celebration in honor of the first German settlers in America. October 5, 1936. Anthony Potter Collection/Getty images.

“We look with heartfelt reverence and sincere trust to the great leader of our old homeland, with the wish that God bless his new work—we are aware of our responsibility as German-American youth and will do our part to ensure that the new spirit of our times will once again become a force for the renewed health of our people. Rise up!” - Erna, camper, in Jungsturm

“This is our main goal, to create a large community of American-German youth, where all boys and girls who are of German blood pass through our youth movement. We want to ensure that the German race of the American people will be healthier and stronger, and from which the leaders of the nation will emerge.” - Junges Volk editorial, summer 1937

This image was part of Bund records seized by the Department of Treasury in 1942 in its investigation of the group’s finances. National Archives and Records Administration.

#NOVA | PBS#Nazi Summer Camp 🏕️ ⛺️#Miscellaneous Photos | Scenes#Kirstin Butler#Nazi Town USA 🇺🇸 | Article#American Experience

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

“We Rock ‘n’ Rollers Will Resist—And We Will Triumph!

When the Smoke Cleared on Disco Demolition Night, Debate Over Its Cultural Meaning Began.

— October 26, 2023 | Kirstin Butler

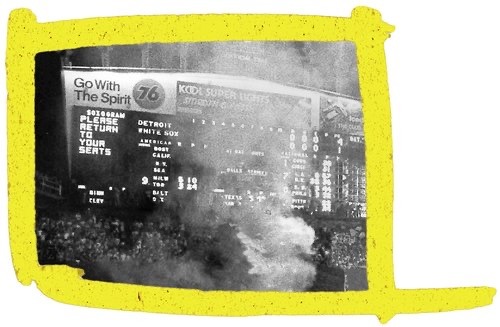

Courtesy Chicago Sun-Times. Photo by Jack Lenahan

In the bright glare of Comiskey Park’s stadium lights, the rising column of smoke takes on a spectral quality. Riot police approach from the right to close in on the phantom, a smoldering pile of vinyl records, at center field. Debris litters the turf below; haze obscures the deck above. Disco Demolition Night, as captured here by a Chicago Sun-Times staff reporter, had turned into something far more out-of-control than a promotional stunt during a double header.

The July 12, 1979 event was the brainchild of a Chicago shock-jock-style radio personality, 24-year-old Steve Dahl, and Mike Veeck, Chicago White Sox promotions manager and son of the baseball club’s owner. Dahl had become a self-appointed anti-disco activist the previous Christmas Eve when he lost his job; his then-employer had switched overnight from rock to an all-disco playlist, following a nationwide trend that saw many radio stations jump on the disco hype train.

Dahl landed at WLUP 97.9, another rock station, where he developed a loyal following. He opened each morning’s broadcast with a ritual: According to a 2019 interview with NPR, Dahl would first cue up a disco song, and then after a harsh record scratch, play the sound of an explosion. He began hosting “Death to Disco” rallies at local Chicago nightclubs, and his band, Teenage Radiation, recorded a disco parody track (sample lyric: “Look at my hair, it's perfect/I saw Saturday Night Fever/Eighty-seven times”). “We have to destroy all disco, it’s our job,” Dahl told his listeners. He planned to make good on his destructive mission, literally, by blowing up a cache of disco records at a local mall. When Veeck learned of the idea, he offered Dahl a much larger venue for the pyrotechnics. The event would take place on one of Comiskey Park’s teen nights.

Dahl was tapping into an animus that had as much to do with anxiety over the zeitgeist as dislike of a musical genre. “It’s worth remembering now that in 1979, the economy and economic opportunities for people who don’t have a college education is actually shrinking,” Adam Green, a professor of African American history and cultural studies at the University of Chicago, told American Experience. “The city is changing because of things that have to do with the economy and politics; it’s not changing because of disco music. But if Steve Dahl says that he’s been screwed by disco, it gives permission to other people to say, ‘you know what? I’ve been screwed too.’”

youtube

Steve Dahl’s band recorded an anti-disco parody of Rod Stewart’s “Do Ya Think I’m Sexy.”

Disco had first emerged earlier in the decade, evolving out of funk, R&B and soul music; its innovators were Black, gay and Latino, and its milieu was the underground nightclub, where those marginalized groups found safe spaces to socialize. However, once record labels realized the genre’s commercial potential, disco music went mass market. And those now-mainstream clubs where disco was played (of which Studio 54 in New York City was the ne plus ultra) developed an elitist cachet that alienated the young, mostly white working class Chicagoans who listened to Dahl. With songs like “Y.M.C.A.,” “Night Fever” and “I Will Survive” topping the Billboard charts, the genre’s ascendance by the end of the Seventies was complete. It was also, then, a prime target for takedown.

These currents were all swirling in the air around the nighttime double header in mid-July, a showdown between the last-in-league Chicago White Sox and the Detroit Tigers. Veeck simply thought Disco Demolition Night would draw several thousand more fans during a losing season.

Dahl wore a combat helmet and fatigues to the park. His anti-disco army turned out en masse, drinking and growing increasingly rowdy as the innings went on. By the time Dahl rode out onto the field in a military Jeep after the first game, nearly 50,000 spectators were crammed into the park; an additional 10,000-plus were outside.

For reduced-price tickets to the park that night, many attendees brought records to be destroyed; all of the sacrificial vinyl filled a bin that was set down, ceremonially, in the middle of the field. Dahl got the crowd chanting “Disco Sucks,” a message matched by homemade banners hung from the stadium’s upper deck. “They’re not gonna shove it down our throats,” he yelled into a microphone. “We rock ‘n’ rollers will resist—and we will triumph!” The records were detonated, tearing a crater into the midfield sod. “That blowed up real good,” Dahl crowed, echoing the signature line that accompanied his on-air disco “explosions.” Triumphant, he got back in the Jeep and rode off the field—along with many of the ballpark security staff. That was when the true mayhem broke out.

People started streaming onto the green by the thousands. They stole bases and tipped over a batting cage; they ripped up turf. They rushed both bullpens and began burning signs. Fights broke out. Veteran White Sox announcer Harry Caray tried to shift the tone by singing ‘Take Me Out to the Ballgame’ over the PA system. No one listened. A message on the scoreboard—PLEASE RETURN TO YOUR SEATS—pleaded, futilely, with the attendees still stoking fires. White Sox announcer Jimmy Piersall opined, “I hope they don’t let you people see what’s going on here at Comiskey Park; one of the saddest sights I’ve ever seen in a ballpark in my life.” Eventually the Chicago riot police arrived, some on horseback, and cleared the field.

Later, after the smoke cleared, and critics and commentators began evaluating the event, many would describe Disco Demolition as an opening salvo in the culture wars. What role racism and homophobia played in Dahl and his groupies’ rebellion remained up for debate. Even from today’s vantage point, a definitive interpretation of Disco Demolition is still murky. “If we seek a true memory,” Green said, “this is the meaning of the backlash against disco, then we're probably going to find ourselves in a situation where we never settle the argument. And I think that that’s the way of all major cultural transformations.”

#Youtube#American Experience#NOVA | PBS#Kirstin Butler#Rock ‘n’ Rollers#Triumph#Steve Dahl#Disco Demolition Night#Debate Over Cultural Meaning

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

How One Black Doctor Brought the Pap to the People! Helen Dickens Was a Crusader Whose Cancer Van Saved Hundreds of Lives

— March 7, 2024 | Kirstin Butler

A Collage Featuring Dr. Helen Octavia Dickens, Hospital Beds, a Microscope, Cancer Cells, and a Van with the Words "American Cancer Society" on the side. Art by Colin Mahoney. Source images from the National Library of Medicine, National Museum of Health and Medicine, Wikimedia.

In 1926, 17-year-old Helen Dickens would sit in the front row of her pre med courses at Crane Junior College in Chicago. Dickens was a dedicated student, but her seating choice in a majority-white academic environment was strategic. “If other students wanted a good seat they had to sit beside me,” she recalled in an interview years later. “This way I didn’t have to look at them or the gestures made that were directed against me.” Dickens went on to become the one Black woman in her graduating class at the University of Illinois College of Medicine, where she met further bigotry with quiet determination. “Her frame of mind was, ‘I'll work through it,’” her daughter Jayne Henderson Brown, also a doctor, told American Experience. “Which she did. It didn't stop her.”

As Dr. Dickens was wrapping up her two-year obstetrics residency, she encountered the next hurdle to her childhood dream of practicing medicine: As a Black woman, white hospitals that employed female doctors didn’t want her, and hospitals serving the Black community hired only men. She was unsure where to go next until, one day, she read a notice on a bulletin board that changed the course of her professional life. It was a letter from Dr. Virginia Alexander, another young Black female doctor, looking for women to join her practice. Alexander ran the Aspiranto Health Home as an alternative birthing center out of her three-story row house in Philadelphia, using her living room as the waiting room and her dining room for treatment. Expectant mothers—some of whom were Black and impoverished, and without other access to care—came to Alexander’s home and received unusually long postpartum care and access to birth control.

Aspiranto was “community service in private practice,” Alexander wrote to Dickens, a “socialized practice of medicine.” Dickens went to Philly, and one year after her arrival took over the home altogether at age 27. The principles behind Aspiranto would guide the way she practiced medicine for the rest of her career. “Alexander helped Dickens to formulate a consciousness around how healthcare could be used as a site of activism,” said Dr. Amina Shakir, who wrote her dissertation about Dickens.

In many ways, Dickens’s background had already primed her to be community-conscious. Her father, Charles, had been born into slavery before escaping and teaching himself to read; he passed when Helen was only eight. “I know when he died,” Dickens later told an interviewer, “he had mortgaged our house to help build a Black meeting hall.” Her father’s death resulted from an infection after a tooth extraction—antibiotics didn’t yet exist—and yet when Dickens was 12, she talked to the family dentist about the possibility of going into medicine. Her father had wanted her to be a nurse, “[b]ut somewhere along the way,” she said, “I decided that if I was going to be a nurse, I might as well become a doctor.”

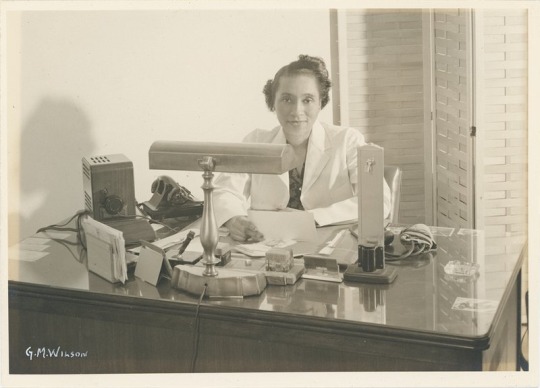

Dr. Helen Octavia Dickens at her desk. Image courtesy Jayne Henderson Brown.

Over the next seven years of her directorship of Aspiranto, she got the community interaction that she’d always wanted. “It was very exciting,” Dickens remembered of her time leading the birthing center. “You were going into the homes. You were seeing all these people. You were taking responsibility for care of people.” And as one of the first Black female doctors in the city, Dickens saw firsthand the inequity of the healthcare system and the extent to which medicine often marginalized Black women. She dedicated the rest of her life to bringing the best and newest models of care to her own community.

That dedication, during the next chapter of her career, involved getting as many Black women as possible to take a brand new medical test: the pap smear. The test’s namesake was Dr. George Papanicolaou, a Greek immigrant physician who with his wife and lab technician Mary worked for decades to document its efficacy in detecting cervical cancer, then the highest-killing cancer for women. Before the pap smear, cervical cancer was detected by biopsy, which often meant it was too late to treat the disease. “By the time you have symptoms, there's already a mass,” Dr. Henderson Brown explains. “It's already metastasized—liver, lung—and it kills. So the earlier it is detected, the easier it is to prevent the spread.” Dickens, who by the early 1950s had become the first African American board-certified OB/GYN in Philadelphia, proselytized the pap smear’s potential to save her patients’ lives.

Dr. George Papanicolaou Pioneered the Lifesaving Cervical Cancer Screening that now Bears his Name.

First, though, she had to get beyond their historically well-earned distrust of gynecological treatment. The legacy of experimentation and forced sterilization of Black women made them wary of receiving care. “A lot of women are reluctant to get medical checkups that include pelvic exams,” she told the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin—which meant Dickens had to bring the test to them. She did so through clinics and workshops at Black churches; in later years, Dickens even provided free pap tests out of a mobile unit, parking an American Cancer Society van in church parking lots. Dickens also got the National Institutes of Health to fund a program to train other doctors to perform pap tests. “But she doesn't just stop there,” Shakir adds. “She also uses her work to provide statistics on Black women patients for the first time…She's really a forerunner. We take this for granted today because of the ways in which we use patient data.”

Dickens continued her crusade of improving Black women’s medical access in a variety of ways. After joining the faculty of the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Medicine in 1965, she pioneered a program for pregnant teens. And as the university’s dean for minority affairs, Dickens recruited other potential doctors from underserved communities, as she herself had once been.

All of this work she did matter-of-factly. It was, says Dr. Shakir, “her unrelenting way of making sure that the dignity and humanity of Black women was respected.” Or as her daughter notes, “I meet people all the time who say, ‘your mother delivered me’ or, ‘we really loved your mother.’ So I think her legacy is the gift she gave of healthcare to every woman who came within 10 feet of her.”

#American 🇺🇸 Experience#The Cancer Detectives#Article#Dr. Helen Octavia Dickens#Helen Dickens | The Crusader | Cancer Van | Against Cancer#Kirstin Butler#Dr. George Papanicolaou#Pioneered | Lifesaving Cervical Cancer Screening

0 notes

Text

Dorothy Thompson Is the Most Famous Female Journalist You've Never Heard Of

She made a name for herself by speaking out against fascism abroad and at home. Then the fight got personal.

— January 11, 2024 | Kirstin Butler

A Full-Color Illustration Featuring Archival Images of Journalist Dorothy Thompson, a Typewriter, Marching Nazi Troops, and the Book "I Saw Hitler". Art by Colin Mahoney. Source photo of Dorothy Thomspon: National Archives and Records Administration

On the morning of August 25, 1934, the American journalist Dorothy Thompson was taking breakfast in her room at the Hotel Adlon in Berlin when she received a letter from the Gestapo. “In view of your numerous anti-German publications in the American press,” Thompson was informed, “the German authorities, for reasons of national self respect, are unable to extend to you a further right of hospitality.”

The Reich bore her a distinct animus. For years, she had been critical of fascist movements throughout Europe. After being granted an interview with Hitler in 1931, Thompson wrote an especially unflattering portrayal of the soon-to-be German chancellor. That long essay, which first ran in Cosmopolitan Magazine, was subsequently turned into a book called I Saw Hitler. “He is formless, almost faceless,” Thompson had written, “a man whose countenance is a caricature, a man whose framework seems cartilaginous, without bones. He is inconsequent and voluble, ill-poised, insecure. He is the very prototype of the Little Man.” In addition to that injurious portrait, Thompson had produced a series of articles for the Jewish Daily Bulletin deploring Hitler’s anti-semitic policies.

The Führer was reportedly threatened enough by her work to demand the creation of a “Dorothy Thompson Emergency Squad” to rush translations of her articles. Now, at the personal directive of Hitler himself, she was being expelled from the country, an unprecedented act against an American correspondent.

A cadre of foreign journalists sent Thompson off, colleagues from her years as Central European Bureau chief for the New York Evening Post and Philadelphia Public Ledger. (She had been the first-ever woman appointed to the position, which oversaw foreign coverage for both newspapers, a decade earlier.) “Nearly the entire corps of American and British correspondents went to the railway station to see her off and wish her good luck,” the New York Times reported, adding that Thompson was presented with an armful of American Beauty roses as a gesture of admiration.

Far from silencing her, the expulsion only increased Thompson’s influence. The Times featured the story of her ban on the newspaper’s front page, and eagerly ran her reflections about it the following day. “My offense was to think that Hitler is just an ordinary man,” she wrote. “That is a crime against the reigning cult in Germany, which says Mr. Hitler is a Messiah sent by God to save the German people—an old Jewish idea.” Thompson closed her column in the Times with the kind of bon mot that had already propelled her to public renown: “To question this mystic mission is so heinous that, if you are a German, you can be sent to jail. I, fortunately, am an American, so I merely was sent to Paris. Worse things can happen to one.”

Thompson in 1937. Getty Images.

Upon her return to the United States, Thompson turned her indomitable energies toward denouncing fascism with every opportunity she was offered, and she was offered many. First came a 30-city lecture tour spanning the next year and a half. Then in 1935, NBC offered Thompson her own weekly radio show, allowing her to speak directly to tens of millions. The next year she began writing “On the Record,” a regular column with the New York Herald Tribune, that was syndicated to 150 other newspapers across the country, placing her opinions in front of millions more. She was eventually given a TIME magazine cover, where the accompanying profile called her and Eleanor Roosevelt “undoubtedly the most influential women in the U.S.”

Thompson leveraged all of these platforms to warn audiences about the dangers of totalitarianism—but not just in Europe. At home, she found cause for concern in the New Deal, with its wage- and price-setting, its massive public works projects and centralized power vested in the executive branch, all of which she feared could presage a slide into authoritarian rule. “What we are interested in is neither the dictatorial talents nor the dictatorial predilections of the President. We aren’t concerned with whether he wants too much power, but with whether he can get too much power.” In 1937, she testified before Congress about what she viewed as a slippery slope from consolidated federal control to fascism. “In country after country, under one slogan or another, the people are retreating from freedom,” Thompson told the Senate Judiciary Committee, “and voluntarily relinquishing liberty to force and authority.”

“Her point was this can happen anywhere,” University of London professor Sarah Churchwell told American Experience. “You have to strengthen your Democratic guardrails. You have to ensure that you don't let this happen to you because complacency is the enemy. And that is what she wrote about over and over and over again, banging the drum. Warning people, take this seriously. This isn’t a joke. And nobody is immune to it.” Thompson saw no conflict between her roles as a journalist and a staunch anti-fascist voice. “The function of journalism and a free press is not confined to the presentation of news,” she wrote. “Their function is to create continual debate, to provide a forum, to give opportunity for the expression of opinion.”

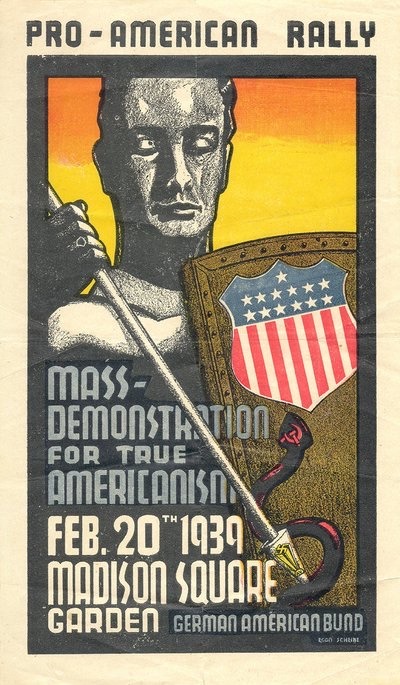

A promotional poster for the 1939 Bund rally in Madison Square Garden. Image courtesy of the National Museum of American Jewish Military History.

When it came to homegrown American Nazism, that expression involved significant personal risk. Thompson’s moment of direct action took place on February 20, 1939 at New York City’s Madison Square Garden. She was on her way to give a speech when she decided to join a convocation of 22,000 American Nazis hosted by the German American Bund, a pro-fascist organization with chapters across the country. The event had been planned to coincide with George Washington’s birthday, billed by the Bund as a “mass demonstration for true Americanism.”

Coverage in The Boston Globe the next day noted that the rally had “all the trappings of the spectacular mass assemblies familiar to Nazi Germany…Storm troopers strode the aisles. Military bands blared martial airs and German folk songs. Young and old Bund members paraded and drilled in the glare of blue spotlights. Arms snapped out in the Nazi salute.” The American flag hung side by side with the Nazi swastika and banners bearing messages such as “Stop Jewish Domination of Christian America.”

Thompson was seated in the front row of the press box, and during the evening’s speeches, began to laugh, loudly and disruptively. After being escorted out of the building by New York City police, she returned to her seat where she was surrounded by a dozen Bund stormtroopers. Thompson then proceeded to cause a second scene by shouting “bunk!” at the stage. “It may have been her finest moment,” wrote her biographer Peter Kurth, “the indelible dramatization of her promise to Hitler that she would not be muzzled by thugs.”

“I was amazed to see a duplicate of what I saw seven years ago in Germany,” she told a reporter after leaving the event. “Tonight I listened to words taken out of the mouth of Adolf Hitler.” It was precisely those words’ utterance at home that alarmed her most. She had spent a good part of her career watching how fascism could, improbable as it might first have seemed, sweep over a nation.

“No people ever recognize their dictator in advance,” Thompson wrote in a 1937 “On the Record” column, making the clearest case possible for constant vigilance. “He never stands for election on the platform of dictatorship. He always represents himself as the instrument for expressing the Incorporated National Will. When Americans think of dictators they always think of some foreign model. If anyone turned up here in a fur hat, boots and a grim look he would be recognized and shunned…But when our dictator turns up you can depend on it that he will be one of the boys, and he will stand for everything traditionally American.”

#Nazi Town | USA 🇺🇸#Article#NOVA | PBS#Dorothy Thompson#Most Famous#Female Journalist#Kirstin Butler#American Experience

0 notes

Text

No One Used To Care About The Vice Presidency. Here's How (And Why) That's Changed.

The Second-In-Command Position Used To Be "Insignificant" But Can't Be Ignored Today

— September 13, 2024 | Kirstin Butler

Two War Criminals Still At Large: President George Walker Bush and Vice President Richard Bruce (Dickhead) Cheney in the presidential limousine, August 13, 2002. National Archives.

The vice presidency used to look dramatically different than it does today. Largely, this is because of how little definition the Founding Fathers gave to the role in the first place. “The framers of the Constitution thought very little of the vice presidency,” says Jared Cohen, author of The Accidental Presidents. “They thought even less about succession. And I think that's fascinating because people didn't live that long back then, and succession should have been a fundamental feature of how they were thinking about democracy.”

Officially, the Constitution assigned the vice president only two jobs. The first was serving as presiding officer of the Senate, where the VP has the power to cast tie-breaking votes. The second was to assume the president’s duties in the event of disability, death, or resignation. In fact, vice presidents originally had so few formal responsibilities that a member of the first U.S. Congress thought they should be compensated on a per diem basis. As a result, most early vice presidents found themselves at loose ends.

The country’s first vice president, John Adams, had a view of the role’s limits from the very birth of the republic. Referring to himself as “a mere Doge of Venice,” Adams called the position “the most insignificant office that ever the invention of man contrived.” It wasn’t until the 20th century that the role began to turn into something more.

Warren Gamaliel Harding, left, and John Calvin Coolidge Jr., right, first photographed together as Republican party nominees for the presidency and vice presidency, June 30, 1920. Library of Congress.

Warren Harding was the first president to invite his vice, Calvin Coolidge, to attend Cabinet meetings; Franklin Delano Roosevelt continued the practice with all three of his vice presidents. Nonetheless, Roosevelt’s last VP, Harry Truman, felt completely unprepared to assume the presidency when FDR died. Truman had been kept so ignorant of critical policy issues that he was only informed about the Manhattan Project upon taking the chief executive office.

“In Truman's 82 days as vice president, he didn't get a single intelligence briefing,” Cohen tells American Experience. “He'd only met FDR twice. He never stepped foot in the map room where the war was being planned. He was not briefed on the atomic bomb. He was completely out of the loop.” Once himself President, however, Truman set out to rectify the role he’d stepped into. He had Congress add the vice president to the National Security Council, while also elevating the office with a higher salary.

President Dwight David Eisenhower and Vice President Richard Milhous Nixon pose for photographers on the reviewing stand for the inaugural parade, January 20, 1953. National Archives.

Having witnessed Truman’s difficulties, next-in-line Dwight Eisenhower also wanted to make sure his potential successor was intimately involved in the ins and outs of domestic and foreign policy. Vice President Richard Nixon was invited to attend briefings alongside President Eisenhower, met with dozens of foreign leaders on his behalf, and worked on important Civil Rights legislation.

But the most significant shift in vice presidential status came when Walter Mondale assumed the office. President Jimmy Carter treated his VP as a full partner, giving him unprecedented equal access to classified materials and meeting sometimes for hours daily to discuss important developments. Mondale was also given symbolic evidence of the role’s increased importance: a permanent office in the White House, for the first time ever.

Vice President Walter Frederick "Fritz" Mondale and President James Earl Carter Jr. (Jimmy Carter) on their way to meet about the Iran Hostage Crisis at Camp David, Maryland. Image courtesy Library of Congress.

The Carter-Mondale model became a template for how future presidents and vice presidents worked together going forward. And while every governing partnership is different, vice presidents in the modern era have often served as confidants, advisors, and diplomats of policy—finally transforming the vice presidency into an office of greater stature.

William Jefferson Clinton (Bill Clinton) and Albert Arnold Gore Jr. (Al Gore) watch the results of the congressional vote over the North American Free Trade Agreement, November 17, 1993. Bob McNeeley, National Archives.

0 notes

Text

August Rain in the Everglades

There’s So Much More to This Simple Image of a Man and His Canoe Than Meets The Eye.

— Published: July 9, 2021 | Kirstin Butler | American Experience

A Seminole man hauls a canoe during an August rainstorm, 1910. Photo by Julian Dimock, American Museum of Natural History

In 1905, the popular American Periodical Century Magazine ran a story called “The Everglades of Florida: A Region of Mystery” that introduced its readers to the vast tropical wetlands in their Southernmost State. “Certainly Nature could have contrived no more impregnable defense to guard any secrets she may have to conceal,” the authors wrote. “It would seem an easy matter to penetrate this unique wilderness, to examine it, to subdue it; in reality, this has proved a well-nigh impossible task.” During the late 19th century, white settlers forced Florida’s Seminole to retreat here from northern Florida. The tribes took sanctuary in the ecosystem’s labyrinth of waterways with their natural protections. “There is no obvious way of forcing a passage,” Century Magazine indignantly contended. “The Region Is Not Exactly Land, and It Is Not Exactly Water.” The Seminole were untroubled by such distinctions. They called their home “Pa-Hay-Okee,” or Grassy Water.

When photographer Julian Dimock arrived during a 1910 expedition, large swaths of the Everglades’ sawgrass marshes and mangrove forests, home to rare and exotic wildlife, were under threat as developers dredged for agriculture and to make artificial canals. But it was still the terrain of Pa-Hay-Okee. The Seminole allowed Dimock to observe and document their customs and provided the invaluable labor of transporting his heavy photographic equipment via canoe. Each of his images required a glass plate negative about the size of a sheet of paper with the thickness of window glass. In images such as this, Dimock captured a way of life endangered by developers bent on dominating the delicate ecosystem and its inhabitants.

As drainage for development increasingly lowered water levels, and a main road was built directly through Seminole territory, the indigenous tribes were pressured to find new ways to sustain themselves. They set up camps where they sold crafts and performed for tourists. In 1947, the area that became Everglades National Park was carved out from grassy waters that had been designated Seminole Territory. Today, the Florida Seminole live on Six Reservations and remain the Only American Tribe Never to Sign a Peace Treaty with the U.S. Government.

#Article#American Experience#From the Collection: Scenes of Summer#“The Everglades of Florida: A Region of Mystery”#American Periodical Century Magazine#The Seminole#“Pa-Hay-Okee”#Grassy Water

1 note

·

View note

Text

Looking Back At The Original Drive-In Movie Theater

How Audiences First Came To Watch Movies From Behind The Wheel.

— Published: July 2, 2021 | Kirstin Butler | June 8, 2023

Cars parked at the first drive-in theater, located on Crescent Boulevard in Pennsauken Township, New Jersey, 1933. Reproduced with permission from the Historical Society of Pennsylvania

The first film ever screened at a drive-in movie theater was British. On June 6, 1933, just outside Camden, New Jersey drivers paid 25 cents per car, plus an additional 25 cents per person to watch the English comedy Wives Beware at this quintessentially American institution in the open air. The local Courier-Post newspaper had touted the setting as “the first automobile movie theater in the world.” Parked in their Ford Model Bs and Buick Series 40s that Tuesday night, the attendees knew they were participating in a novel experiment—but they could not have known the extent to which the phenomenon they experienced would spread throughout the country in the next few decades.

The innovator behind this motor-age phenomenon, Richard Milton Hollingshead, Jr., got his start at the Whiz Auto Products Company, founded by his father in the early years of the 20th century to sell automobile accessories such as greases, oils and polishes. In an inspired extension of the family business in the early 1930s, Hollingshead did the first test run (or perhaps, more accurately, a test park) of his concept using a Kodak projector and a screen nailed to a tree in his backyard. For weeks, he experimented with this home theater layout to ensure all passengers would have unobstructed views of the screen. Parking one car behind another, Hollingshead placed blocks under both cars’ front wheels to adjust their height until the driver further back could see over the car in front. He captured what was unique about his idea in a 1932 patent application. “My invention relates to a new and useful outdoor theater,” Hollingshead wrote, “whereby the transportation facilities to and from the theater are made to constitute an element of the seating facilities.”

Despite his venture’s successful opening night, the “world’s first” remained ahead of its time. As an institution, the drive-in’s heyday was in the 1950s, when more than 4,000 screens dotted the American landscape. Still, from the very beginning, Hollingshead had correctly identified one of his invention’s key points of appeal. “Here the whole family is welcome,” he told the Courier-Post, “regardless of how noisy the children are apt to be.” According to the National Association of Theater Owners, 549 drive-ins remained in the U.S. in 2020.

#Article#From the Collection | Scenes of Summer#Original | Drive-In Movie Theater 🎭#Audiences | Watch Movies 🎦 🎥 🍿 | Behind the Wheel#American 🇺🇸 Experience | Thirteen PBS

1 note

·

View note

Text

5 Times U.S. Presidential Commissions Rocked the Country

What Do a Long List of Iconic and Controversial Historical Events Have in Common? They All Got The Presidential Commission Treatment.

— May 14, 2024 | Kirstin Butler

President Kennedy rides in his motorcade minutes before his assassination in Dallas in 1963. Bill Waterson/Alamy Stock Photo.

A presidential assassination. Widespread racial protest. Pearl Harbor. The high-profile explosion of a space shuttle. Highly disparate topics, but in each case, a U.S. president was moved—whether by public pressure or their own conscience—to call for a special panel investigating the causes and treatments of a pressing issue.

Presidential commissions are tasked, often under heightened political and time constraints, with explaining complex societal dynamics and events. Sometimes those analyses are heeded; other times, as with President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Kerner Commission, deliberately ignored. And yet in each instance, the formation of a task force appointed to directly advise the president sends an unmistakable public message as to a problem’s significance. Here are five of the 20th century’s most iconic presidential commissions.

President and Mrs. Kennedy and Texas Governor John Connally and his wife ride in the motorcade in Dallas, November 22, 1963. Victor Hugo King/Library of Congress.

Warren Commission

One week after President John F. Kennedy was shot to death in Dallas, Texas, his successor Lyndon Johnson appointed a commission to investigate both Kennedy’s murder and the killing of Lee Harvey Oswald, the president’s alleged assassin. Led by Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren, the commission received testimony from 550 witnesses and 3,100 reports from the FBI and Secret Service.

Nearly 10 months after the task force was formed, the commission submitted its 888-page report to President Johnson, which was subsequently made public along with 26 volumes of supporting documents. The report’s central finding—that Oswald acted alone in Kennedy’s killing, absent any national or international conspiracy—has been the focus of intense speculation and criticism in the years since its release. “As long as a mystery resides at the center of this case, it can't be closed,” investigator Josiah Thompson told American Experience. “There's this fundamental question mark that still stands there in the center of our experience in the 20th century.”

President Lyndon Johnson (Seated, Center) shakes hands with members of the Kerner Commission. July 29, 1967. White House Photo Office Collection, LBJ Presidential Library.

Kerner Commission

The second bombshell commission of Johnson’s presidency, the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders—known colloquially as the Kerner or Riot Commission—was established in July 1967 following several years of urban civil uprisings across the United States. Johnson asked his task force to address three questions: “What happened? Why did it happen? What can be done to prevent it from happening again and again?”

Johnson appointed the Democratic governor of Illinois Otto Kerner as the bipartisan commission’s chair, and its field teams undertook a rigorous, on-the-ground investigation in 23 cities to try to understand the root causes of unrest that led to violence, arson and looting. The conclusion the commission members came to was shocking for its time. “White society is deeply implicated in the ghetto,” their 1968 report plainly stated. “White institutions created it, white institutions maintain it, and white society condones it.” President Johnson was so dismayed that he refused to publicly acknowledge the final report, which nonetheless went on to become a national bestseller.

“The commissioners did not deign to take the easy way out,” said New Yorker journalist Jelani Cobb. “They had the vantage point of having actually seen the conditions with their own eyes, having gone to places and talked to people and come as close as they could to experiencing life in these ghettos. They told the nation what exactly the problem was, even if it meant that no one was going to listen to them.”

A U.S. battleship sinking during the Pearl Harbor attack. National Archives.

Roberts Commission

After the shocking Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt called for an investigative task force to determine if negligence or dereliction of duty on the part of military and government officials had enabled the attack. Chaired by Supreme Court Justice Owen J. Roberts, the commission was made up entirely of active or retired military officials. The investigation began in Washington, D.C. and proceeded to Honolulu, interviewing 127 witnesses. Less than two months after the surprise bombing—an extremely fast turnaround for such a significant event—the commission released its findings.

Roosevelt’s task force assigned blame chiefly to Admiral Husband E. Kimmel and Lieutenant General Walter C. Short, the U.S. military’s top army and navy commanders in the Pacific, both of whom were demoted, while exonerating several prominent political figures. The commission’s final report never specifically mentioned Japanese Americans, but a passage about “Japanese spies” received widespread media coverage, and played a critical part in turning mainstream American public opinion in favor of incarcerating U.S. citizens of Japanese descent. California’s governor confirmed the connection, saying of many of his constituents at the time, "Since the publication of the Roberts Report, they feel they are living in the midst of enemies. They don't trust the Japanese, none of them.’”

Challenger lifts off on Jan. 28, 1986 with a crew of seven astronauts. An accident 73 seconds after liftoff claimed both crew and vehicle. NASA.

Rogers Commission

On January 28, 1986, the space shuttle Challenger exploded 73 seconds after its launch in Cape Canaveral, Florida, a disaster broadcast on live television. NASA immediately halted the shuttle program, and President Ronald Reagan appointed a fact-finding commission chaired by former Attorney General and Secretary of State William Rogers to determine the disaster’s cause. Prominent public figures were named commission members, including astronauts Neil Armstrong and Sally Ride, pilot Chuck Yeager and physicist Richard Feynman.

Extensive commission hearings revealed both mechanical and process failures leading to the explosion. Icy conditions on the day of the shuttle’s launch compromised rubber “O ring” seals on one of the shuttle’s rocket boosters during the extreme conditions of takeoff; during one commission session Feynman spectacularly demonstrated the seal failure by plunging an O ring into a glass of ice water. Following testimony that revealed space agency managers were aware of technical problems for years prior to the Challenger mishap, the commission also faulted NASA for poor engineering and management. The explosion, read the commission’s final report, was “an accident rooted in history.”

Admiral James Watkins hands President Reagan the report of the presidential commission on the HIV epidemic. James D. Parcell/The Washington Post via Getty Images.

Watkins Commission

In June 1987, Reagan called for the formation of another fact-finding mission, this one significantly more politically charged than the Challenger’s. The purpose of the Presidential Commission on the Human Immunodeficiency Virus Epidemic, Reagan said, was to make HIV go “the way of smallpox and polio.” Among the commission members were both Cardinal John O’Connor and gay medical researcher Frank Lilly; the latter’s appointment drew strong criticism from conservative quarters.