#Keiko Takahashi

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Uzumaki aka Spiral aka Vortex (2000)

#uzumaki#spiral#vortex#2000#higuchinsky#junji ito#eriko hatsune#fhi fan#hinako saeki#shin eun-kyung#keiko takahashi#ren osugi#denden#masami horiuchi#taro suwa#asumi miwa#my gifs

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

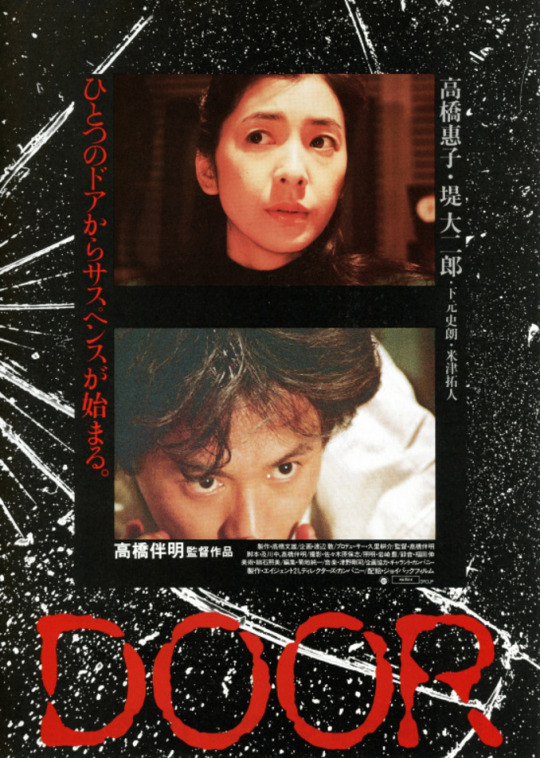

Door (1988)

#my favorite movie of the year#i was lucky enough to watch this on the big screen at a film festival with the director present#door#door 1988#banmei takahashi#keiko takahashi#horror#japanese horror#slasher#80s horror#asian horror#japanese slasher#japanese giallo#giallo#80s giallo#80s fashion#final girl#women in horror#1980s

164 notes

·

View notes

Text

ocs but they're all in different universes..............

#light's drawings#ocs#original character#original characters#protector's will#keiko takahashi#blanco#peashooter#plants vs zombies#cupid

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Door (Banmei Takahashi, 1988)

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Door (1988)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

DOOR Japanese '80s stalker horror thriller - free on Tubi

Door is a 1988 horror thriller about a housewife who is terrorised by a visiting salesman. Directed by Banmei Takahashi from a screenplay co-written with Ataru Oikawa. Produced by Kôsuke Kuri. Executive produced by Fumio Takahashi. The Agent 21-Directors Company co-production stars Keiko Takahashi, Daijirô Tsutsumi, Shirô Shimomoto, Takuto Yonezu, Masao Ishida, Hiroshi Noguchi and Yoshihiro…

View On WordPress

#1988#Blu-ray#Daijirô Tsutsumi#Door#free on Tubi#free online#horror thriller#Japanese#Keiko Takahashi#review reviews#Shirô Shimomoto#Takuto Yonezu

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Recently Viewed: Door

[The following review contains SPOILERS; YOU HAVE BEEN WARNED!]

When I first discovered the existence of Banmei Takahashi’s Door earlier this year (via various clips shared by fan accounts on Twitter), it was love at first sight. Luckily, while the movie currently lacks official distribution in the United States, I didn’t need to wait very long at all to see it (compared to Angel’s Egg, A Page of Madness, and Samurai Wolf, anyway) thanks to the Brooklyn Horror Film Festival, which screened it just before midnight on Friday, October 13th—basically the ideal context in which to experience its unique brand of madness.

The premise is as brilliant as it is straightforward: an ordinary housewife—already fed up with cold callers and their seemingly unlimited access to her family’s personal information—aggressively turns away an especially persistent salesman, slamming the door on his fingers after he ignores her repeated protests and attempts to force his way into her apartment. Unfortunately, this moment of instinctive panic has severe repercussions, resulting in an excruciatingly tense game of cat-and-mouse as the slighted pamphlet pusher’s vengeful wrath gradually evolves into perverse sexual obsession.

It’s a captivatingly mundane flavor of terror, twisting a familiar, relatable scenario into an inescapable nightmare. There’s nothing particularly memorable or remarkable about the central villain. He has no elaborate costume or mask, no supernatural abilities or distinguishing features; unlike Jason Voorhees, Michael Myers, and Leatherface, he doesn’t even wield a signature weapon (though he is quite handy with the absurdly convenient electric chainsaw that he scavenges from the protagonist’s collection of otherwise run-of-the-mill home appliances). This anonymity is absolutely chilling; he effortlessly blends in with the crowd—average, unassuming, invisible. Indeed, his façade of superficial “normalcy” is far more insidious than any explicit display of insanity; he taunts his prey with idle banter, seamlessly transitioning between casual flirtation and thinly veiled threats.

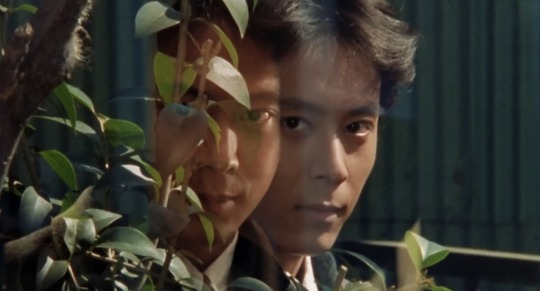

The director’s visual style perfectly complements the suspenseful tone of the narrative. Early scenes almost resemble a slice-of-life domestic drama, characterized by flat compositions and lighting. As the conflict escalates, however, the warm, inviting interiors slowly warp and distort, becoming cramped, claustrophobic, hostile. Foreground elements (potted plants, sculptures, windows, doorways) isolate our heroine within the frame, emphasizing her vulnerability. Voyeuristic point-of-view shots serve a similar purpose, subliminally insinuating that true “safety” is an illusion: the sinister stalker could be lurking around any shadowy corner. The increasingly maximalist cinematography culminates in the film’s most iconic sequence: a prolonged overhead angle that follows the now totally unhinged maniac as he relentlessly pursues his quarry from room to room, utterly demolishing every obstacle in his path—splintering wood, shattering glass, and reducing drywall to dust.

Yet some of the movie’s most haunting images are significantly less spectacular than this climactic set piece. Takahashi understands the inherent value of patience, frequently locking down the camera and lingering on long, uninterrupted closeups of his lead actress simply reacting to suspicious offscreen noises—the echo of footsteps in the corridor, for example, or the telltale rattle of the deadbolt being tested. Keiko Takahashi’s face is breathtakingly expressive; her turbulent emotions are palpable, a violent maelstrom of anxiety, desperation, and paralyzing fear clearly evident in every twitch of her eye, every crease in her brow, every tear staining her cheek.

How thematically appropriate that Door—a story that explores such everyday horrors as rampant commercialism, predatory marketing, and the erosion of privacy—should be at its scariest when it embraces naturalism, minimalism, and subtlety.

#Door#Banmei Takahashi#Keiko Takahashi#Japanese film#Japanese cinema#Japanese horror#J horror#Brooklyn Horror Film Festival#Arrow Video#Nitehawk Cinema#horror#Halloween 2023#film#writing#movie review

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

BLOGTOBER 10/15/2023: DOOR (1988)

I saw a new restoration of this movie at a midnight show that was part of the Brooklyn Horror Film Festival. It seems to have been enjoyed as a classic of its type in Japan but was rarely seen elsewhere, and it deserves a MUCH more thorough and thoughtful write-up than I'm about to give it--but please take this remark as a sign that you should see it if you can! Filmmaker Banmei Takahashi and his actress wife Keiko both broke out of the pink film demimonde and into the mainstream in the early 1980s, and in DOOR one sees shades of their past--it's a lean, efficient thriller starring an imperiled female and a perverted maniac--and also their superior talents. Frankly, I just enjoyed everything about this movie, from its eye-catching location to its infectious music to the excellent set that was tailor-made for Keiko Takahashi and her co-star Daijiro Tsutsumi to chase each other around without the action ever becoming repetitive or implausible. And on top of all that, the script is so sharp that it feels fresh and relevant even 35 years later.

Takahasi plays a housewife whose husband is nearly invisible due to his high-pressure tech career. They live in an apartment complex where her only company, besides her young son (Takuto Yonezu, who is just as good as anybody else in this movie), is an army of intrusive telemarketers. She struggles to maintain the sanctity of her home, shutting down cold callers with increasing vigor until she pushes one of them over the edge. For the frustrated, futureless Daijiro Tsutsumi, being rejected by Takahashi shreds the final thread of his sanity, and he wages a campaign of terror that begins on the phone and transforms into a home invasion. The plot makes sense in the context of the hyper-capitalized Japan of the 1980s, but its themes of eroded privacy, escalating greed, and the dehumanizing effects of wage slavery make DOOR feel like a film that could have come out yesterday. Takahashi makes a wonderful heroine, as attractive and stylish as she is intelligent and independent; at every turn she does exactly what anyone would do to protect herself and her family, never "asking for" what happens to her, and yet it all happens anyway--just like it's happening to us all as our information is bought and sold, rightfully-earned possessions are converted into subscription services, and data-based products like movies and music are practically on loan to us by the corporations we pay to own them. DOOR definitely foresees our modern world, in which advertisements pop up even on pause screens, and telemarketers from other countries can call us all day long with impunity. See it if you can! The real horror is in how relatable it is.

#blogtober#2023#horror#thriller#home invasion#door#banmei takahashi#keiko takahashi#daijiro tsutsumi#japanese#takuto yonezu

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

THE BOY AND THE HERON:

Boy stewing in grief

Enters a world of life and death

Learning how to live

youtube

#the boy and the heron#random richards#poem#haiku#poetry#haiku poem#haiku poetry#hayao miyazaki#soma santoki#masaki suda#ko shibasaki#aimyon#yoshino kimura#takuya kimura#keiko takahashi#jun fubuki#karen takizawa#jun kunimura#kaoru kobayashi#shohei hino#christian bale#studio ghibli#dave bautista#gemma chan#willem dafoe#karen fukuhara#mark hamill#luca padovan#robert pattinson#florence pugh

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Brazilian artist Franci Shimomaebara is also the wife of music master Kitaro

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Watching

DOOR Banmei Takahashi Japan, 1988

#Banmei Takahashi#watching#Japanese films#1988#Keiko Takahashi#Daijirô Tsutsumi#Shirô Shimomoto#Takuto Yonezu

1 note

·

View note

Text

Door (1988)

#door#door 1988#banmei takahashi#keiko takahashi#horror#slasher#80s horror#80s slasher#1980s horror#1980s slasher#giallo#80s giallo#1980s giallo#japanese horror#asian horror#japanese cinema#women in horror#scream queen#final girl

53 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Silly OC stuff

#protector’s will#purotekuta no ishi#pw#PNI#OC#ocs#original character#original characters#keiko takahashi#mamoru mitsushima#Youtube

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

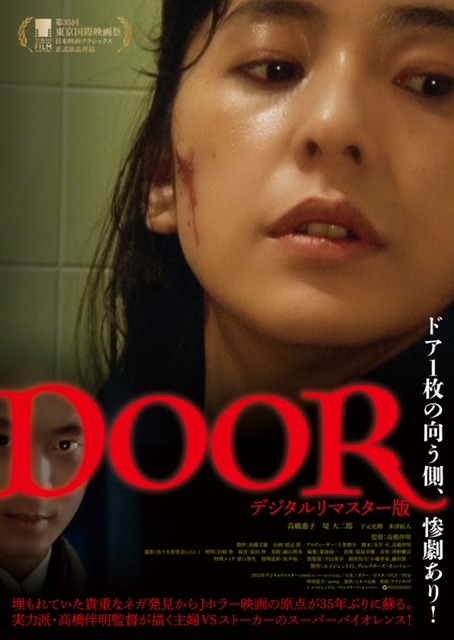

DOOR ドア (1988) Remaster Director: Banmei Takahashi

Happy Halloween! This is the time of year when people celebrate the supernatural and ghoulish aspects of popular culture and national myths. I do my part by highlighting horror movies on Halloween night. So far I have reviewed Nightmare Detective, Strange Circus, Shokuzai, POV: A Cursed Film Charisma, Don’t Look Up, Snow Woman (2017) Snow Woman (1968) Fate/Stay Night Heaven’s Feel, Gemini, John…

View On WordPress

#Banmei Takahashi#Blu-ray release#DOOR (Digitally Restored)#DOOR 2: Tokyo Diary (Digitally Restored)#Japanese Film Trailer#Keiko Takahashi#Ren Osugi#Third Window Films

0 notes

Text

少女コミック (Shoujo Comic) 1976 Calendar, art by : Kishi Yuuko, Takahashi Ryouko, Takemiya Keiko, Hida Nobuko, Hagio Moto, Uehara Kimiko.

#70s#70s manga#岸裕子#yuuko kishi#高橋亮子#takahashi ryouko#竹宮恵子#keiko takemiya#ひだのぶこ#hida nobuko#萩尾望都#moto hagio#上原きみこ#kimiko uehara#vintage shoujo#retro shoujo

75 notes

·

View notes

Text

la la la la la love ka

22 notes

·

View notes