#Kakari

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Man I feel so bad for Geto cause his body is getting used by Kenjaku and getting disrespected in so many ways. Smh.

#his body is getting clowned by kakari because of Kenjaku#i hate Kenjaku#jujutsu kaisen#jjk#jjk spoilers#geto suguru#kenjaku

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Randori Geiko

This is a translation from a text written by Tadayuki Satoh, JAA-Shihan Practice Methods to Prevent Techniques from Becoming Formalistic (1) Kakari-geiko (Active Practice) Aim: To practice accurately while being conscious of engagement distance! Using the techniques learned in the seventeen basic forms, we practice smoothly and accurately while following the principles, being mindful to…

#Aikido#exercise#fitness#health#JAA Aikido#kakari geiko#martial-arts#Randori#Shobukai#Shodokan Aikido#Tomiki#Tomiki Aikido#training

0 notes

Text

Japanese words about "time"

< second : 秒(びょう/byo) >

one second : 一秒(いちびょう/ichi-byo) →More!

for one second : 一秒間(いちびょうかん/ichi-byo-kan)

several seconds : 数秒(すうびょう/su-byo)

5 meters per second : 秒速5メートル(びょうそく5メートル/byo-soku go-mētoru)

< minute : 分(ふん/fun) >

one minute : 一分(いっぷん/ippun) →More!

several minutes : 数分(すうふん/su-fun)

for one minute : 一分間(いっぷんかん/ippun-kan)

Wait a minute. : ちょっと待って(ちょっとまって/Chotto matte.)

*Because Japanese people are very punctual, if you say "Wait 'a minute:ippun'", maybe we think you'll really come back within 2 minutes. So it's better to say "ちょっと(chotto):a little”.

< hour : 時間(じかん/jikan) >

for one hour : 一時間(いちじかん/ichi-jikan) →More!

several hours : 数時間(すうじかん/su-jikan)

How many hours does it take from Tokyo to Osaka by Shinkansen?;

東京から大阪まで新幹線で何時間かかりますか?

とうきょうから おおさかまで しんかんせんで なんじかん かかりますか?

Tokyo-kara Osaka-made Shinkansende nan-jikan kakari-masuka?

It takes 2 and a half to 3 hours: 2時間半から3時間かかります(���じかんはんからさんじかんかかります/Ni-jikan-han-kara san-jikan kakari-masu.)

< time : 時刻(じこく/jikoku) >

one o'clock : 一時(いちじ/ichi-ji)

two o'clock : 二時(にじ/ni-ji)

three o'clock : 三時(さんじ/san-ji)

four o'clock : 四時(よじ/yo-ji) ×よんじ

five o'clock : 五時(ごじ/go-ji)

six o'clock :六時(ろくじ/roku-ji)

seven o'clock : 七時(しちじ/shiji-ji or ななじ/nana-ji)

eight o'clock : 八時(はちじ/hachi-ji)

nine o'clock : 九時(くじ/ku-ji) ×きゅうじ

ten o'clock : 十時(じゅうじ/ju-ji)

eleven o'clock : 十一時(じゅういちじ/ju-ichi-ji)

twelve o'clock : 十二時(じゅうにじ/ju-ni-ji)

a.m. : 午前(ごぜん/gozen)

p.m. : 午後(ごご/gogo)

morning : 朝(あさ/asa)

noon : 正午(しょうご/shogo) 、昼の12時(ひるのじゅうにじ/hiruno ju-ni-ji)

*We say "昼(ひる/hiru)" for around noon - afternoon.

evening : 夕方(ゆうがた/yugata)

*It depens on the person, but I mean around 16:00 - 18:59 by 夕方(ゆうがた/yugata).

night : 夜(よる/yoru)

*It depends on the person, but I mean after 19:00 by 夜(よる/yoru).

What time is it now? : 今は何時ですか?(いまはなんじですか?/Imawa nanji desuka?)

It's 9:30 at night. : 夜の9時半です(よるのくじはんです/Yoruno kuji-han desu.)

It's 7:45 in the morning. : 朝の7時45分です(あさのしちじよんじゅうごふんです/Asano shichi-ji yonju-go-fun desu.)

*We usually say "shichi-ji" for 7:00 and say "nana-ji" only when we want to emphasize that it's 7:00 and not 1:00.

< day : 日(にち/nichi) >

one day : 一日(いちにち/ichi-nichi) → More!

half day : 半日(はんにち/han-nichi)

everyday : 毎日(まいにち/mai-nichi)

today : 今日(きょう/kyo) or 本日(ほんじつ/hon-jitsu)

tomorrow : 明日(あした/ashita or あす/asu)

the day after tomorrow : 明後日(あさって/asatte or みょうごにち/myo-go-nichi)

two days after tomorrow : 明明後日(しあさって/shiasatte or みょうみょうごにち/myo-myo-gonichi)

yesterday : 昨日(きのう/kino or さくじつ/saku-jitsu)

the day before yesterday : 一昨日(おととい/ototoi or いっさくじつ/issaku-jitsu)

two days before yesterday : 一昨昨日(さきおととい/saki-ototoi or いっさくさくじつ/issaku-saku-jitsu)

three days later : 三日後(みっかご/mikka-go)

five days before : 五日前(いつかまえ/itsuka-mae)

< date : 日付(ひづけ/hizuke) >

1st day of each month : 一日(ついたち/tsuitachi) →More!

January 1st : 一月一日(いちがつついたち/Ichi-gatsu tsuitachi)

What is the date today? : 今日は何月何日ですか?(きょうはなんがつなんにちですか?/Kyowa nan-gatsu nan-nichi desuka?)

*You can ask just ”今日は何日ですか?(きょうはなんにちですか?/Kyowa nan-nichi desuka?)" if you don't need month.

*You can ask "今日は何年何月何日ですか?(きょうはなんねんなんがつなんにちですか?/Kyowa nan-nen nan-gatsu nan-nichi desuka?)" if you need year, too.

When is your birthday? : あなたの誕生日はいつですか?(あなたのたんじょうびは、いつですか?/Anatano tanjobiwa itsu desuka?)

It's December 30th. : 12月30日です(じゅうにがつさんじゅうにちです/Ju-ni-gatsu san-ju-nichi desu.)

< week : 週(しゅう/shu) >

one week : 一週間(いっしゅうかん/isshukan) →More!

every week : 毎週(まいしゅう/mai-shu)

every two weeks : 隔週(かくしゅう/kaku-shu)

this week : 今週(こんしゅう/kon-shu)

next week : 来週(らいしゅう/rai-shu)

the week after next : 再来週(さらいしゅう/sa-raishu)

last week : 先週(せんしゅう/sen-shu)

the week before last : 先々週(せんせんしゅう/sen-sen-shu)

the 2nd week of next month : 来月の第二週(らいげつのだいにしゅう/rai-getsuno dai-ni-shu)

< day of the week : 曜日(ようび/yobi) >

Please remember kanji "月火水木金土日” and the pronunciation "Getsu-Ka-Sui-Moku-Kin-Do-Nichi" in the right order. "ようび(Yobi)" is also said as just "よう(yo)", like "げつよう(Getsu-yo)", and we often even omit ようび(yobi) when we talk, like "土日(Do-Nichi):weekend" or "月水金(Getsu-Sui-Kin or Gessuikin):Mon, Wed, Fri".

Monday : 月曜日(げつようび/Getsu-yobi)

Tuesday : 火曜日(かようび/Ka-yobi)

Wednesday : 水曜日(すいようび/Sui-yobi)

Thursday : 木曜日(もくようび/Moku-yobi)

Friday : 金曜日(きんようび/Kin-yobi)

Saturday : 土曜日(どようび/Do-yobi)

Sunday : 日曜日(にちようび/Nichi-yobi)

Weekday : 平日(へいじつ/hei-jitsu)

Weekend : 週末(しゅうまつ/Shu-matsu)

What day is today? : 今日は何曜日ですか?(きょうはなんようびですか?/Kyowa nan-yobi desuka?)

Tomorrow is Sunday so I have the day off: 明日は日曜日だから、私は休みです(あしたはにちようびだから、わたしはやすみです/Ashitawa Nichi-yobi dakara, watashiwa yasumi desu.)

< month : 月(つき/tsuki) >

one month : 一か月(いっかげつ/ikkagetsu)or ひと月(hito-tsuki)

two months : 二か月(にかげつ/ni-kagetsu) or ふた月(futa-tsuki)

three months : 三か月(さんかげつ/san-kagetsu) or み月(mi-tsuki)

Beyond that, we usually use ”かげつ(kagetsu)" and hardly use "つき(tsuki)" which is the old way of counting.

→More!

January : 一月(いちがつ/Ichi-gatsu)

February : 二月(にがつ/Ni-gatsu)

March : 三月(さんがつ/San-gatsu)

April : 四月(しがつ/Shi-gatsu)

May : 五月(ごがつ/Go-gatsu)

June : 六月(ろくがつ/Roku-gatsu)

July : 七月(しちがつ/Shichi-gatsu or なながつ/Nana-gatsu)

*We usually say "shichi-gatsu" for July and say "nana-gatsu" only when we want to emphasize that it's July and not January(Ichi-gatsu).

August : 八月(はちがつ/Hachi-gatsu)

September : 九月(くがつ/Ku-gatsu)

October : 十月(じゅうがつ/Ju-gatsu)

November : 十一月(じゅういちがつ/Ju-ichi-gatsu)

December : 十二月(じゅうにがつ/Ju-ni-gatsu)

< year : 年(ねん/nen) >

one year : 一年(いちねん/ichi-nen) →More!

for one year : 一年間(いちねんかん/ichi-nen-kan)

half a year : 半年(はんとし/han-toshi)

every year : 毎年(まいとし/mai-toshi)

this year : 今年(ことし/kotoshi)、本年(ほんねん/hon-nen)

next year : 来年(らいねん/rai-nen)

the year after next : 再来年(さらいねん/sa-rainen)

last year : 去年(きょねん/kyonen) or 昨年(さくねん/saku-nen)

the year before last : 一昨年(おととし/ototoshi or いっさくねん/issakunen)

*When you say きょねん/kyonen, don't say きょうねん/kyo-nen although it looks almost same in romaji, because we have the word kyounen(享年/きょうねん)which means the age when the person died.

in 2024 : 2024年に(にせんにじゅうよねんに/nisen-niju-yo-nen-ni)

#apothecary english#apothecary romaji#the apothecary diaries#apothecary diaries#learning japanese#japanese#japan

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

I just finished episode 9 of Konya Sukiyaki Dayo

!!!!!!!!!

I would be happy enough if it ended here - I can't believe I get 3 more episodes! Looking forward to seeing what's next.

I really love when they mix up the end credits to get the boys in there. Shinta I have loved from the beginning; Yuki had to grow on me but now I adore him.

I like this living in the same apartment building deal... I do imagine a 3 bedroom apt/house scenario and wonder how that would work out. After seeing how Aiko sleeps (lol) I want her and Yuki to please please get a bigger bed (I recently shared a like king sized bed in a hotel with a friend and omg ??? There's so much space we may as well have been in separate beds) (not sure you can find apartments in Japan with room for that though idk) in one room but also still have separate rooms like they talked about. And of course I want Tomoko and Aiko to keep living together. What I'm curious about is how Tomoko and Yuki would feel about living together... would that work out or would everyone dislike it? The current arrangement seems good, I just wonder.

it's a shame hyphenating their surnames doesn't seem to be an option. I mean ideally they could get married with no one changing their name but if the rule is registered families must share a name it seems like Ota-Seguira could be an option. But I guess that just isn't done. But I also wondered if they can't legally change their name and then keep using their old surname professionally and personally. But anyway pulling out rock paper scissors at the family dinner was fucking iconic. Seguira-soon-to-be-Ota Yuki you are a legend. He really said "if the Seguira family traditions are going to make Aiko unhappy then we will simply not be the Seguira family" and I respect him for it greatly. (also I feel like I'm spelling that surname wrong am I missing a vowel or inserting an extra one? Idk)

also I hope one of these remaining 3 episodes gives some more room for Shinta. He's a star.

also also: shoutout to Japanese dramas making up fun new ways to say "queerplatonic partners" / "platonic life partners". Kazoku kazu kakari / Family (Subject to Change) has a deeply special place in my heart to the point that genuinely if I did ever form a partnership I would probably refer to it that way sometimes. But Clownfish-Anemone makes me smile a lot :) yes! Mutualism! Symbiotic partnership!

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fanmade Touhou stage 2 bosses

Vlasta Brüger (aka Wistful Casualty), a soldier yuurei (specifically based on a fext) with the ability to create platoons of herself

Rie Kakari (aka the Scroll of Sacred Knowledge), a kyōrinrin with the power of universal telecalligraphy (writing with her mind in any language)

Kuzuname Sarajita (aka One-Man Cleaning Crew), an akaname with the ability to thoroughly clean any surface using only their tongue

and Chizui Miidera (aka Memento Mori Waiting at the Well), a kyokotsu-gashadokuro hybrid with the ability to add and remove bones to and from her own body

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

I now get to reveal another song in the Es Quest Playlist: Bug by Kakari Bear is an Es Quest Amane song.

I'm lost, lost, right amidst this pa-pa-para paranoia Bzzz-zzzt, it’s pruning my heart, this pa-pa-para paranoia I ended up cutting off an escape route, tangled up in pa-pa-para paranoia How sad, how sad - I'm lying down, prostrate and empty - pa-pa-para, all paranoid

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

I had a crack at making Tenzo, Genma, Kakashi, Iruka, Team 7 and my two OC's Kakari and Hiko on the Sims 4. They're not great bc I don't have any of the stuff I downloaded as it caused my laptop to have a melt down! 🙄

#hatake kakashi#umino iruka#yamato#shiranui genma#naruto#Sasuke#Sakura#Team 7#My OC's#Sims 4#EA#Uzumaki Naruto#Uchiha Sasuke#Haruno Sakura#Kakashi#Iruka#Genma#Tenzo

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nampō Roku, Book 7 (58c): the Second Kaki-ire [書入] from Shibayama’s Toku-shu Shahon [特殊写本].

〽 Kaki-ire [書入]:

〚When the furo, and the mizusashi, are on the nagaita [= ji-ita], because they always rest among the tai [躰; = yang-kane] and yō [用; = yin-kane], nothing is ever done differently -- regardless of whether [the gathering is being held] during the day, or at night¹. For this reason the mizusashi in the small room, too, should be placed carefully according to this same precedent -- both in the daytime and at night².〛

Because it rests atop two tai [= yang-kane], this is naturally a case of kuguru-kane [潜るカネ: an object that crosses successive kane, which makes it yang], so that is the end of the matter³. But when it rests atop one tai and one yō, this is also not a problem [since the object still counts as yang]⁴.

But if the mizusashi is so small that it only rests on a [single] yin [kane], then you should consider it only for use during the daytime⁵. [When using] a small mage-no-mizusashi [小曲ノ水指], as well as a small-sized [ceramic] mizusashi, there is the possibility where the three objects [mizusashi, chaire, and chawan] are arranged together, so that they occupy successive kane⁶.

As for the ordinary kind of mizusashi, [it is] usually larger than 5-sun; while those with a diameter of 6-sun or more are [most] appropriate⁷. Both in the daytime, and at night, these [should] occupy the same place [on the mat]⁸.

In the same way, it is important to understand the way to place an inferior sort of furo⁹. [The furo] is settled into its 1-shaku 4-sun [square] seat, with its kimen- or ama-zura [oriented toward the host’s seat] by turning the kan-tsuki by one-third¹⁰. The furo should not be pushed deeper [toward the far end of the utensil mat]¹¹.

As for the chaire, temmoku, and futaoki, even if these are generally [handled] as has been set down previously, we can not say that their handling during the temae is constrained by the kane¹². [Nevertheless,] the kane should never be neglected entirely¹��.

The futaoki should always be lowered from the nagaita [= ji-ita]¹⁴; though the hoya should naturally be [kept] on the nagaita [throughout the temae]¹⁵.

Ordinarily, there is no reason to move things like the chaire or chawan onto the nagaita during the temae¹⁶. This is something that is done only during [temae] such as the san-shu gokushin [三種極眞].

_________________________

◎ Even though Shibayama Fugen clearly separated passage from the first kaki-ire, and also marked it with the word kaki-ire, it appears to have either originally been part of the first kaki-ire, or else it lost at least its first two sentences (which would establish the subject of the first several remarks as being in reference to the mizusashi).

As the vocabulary is the same, I have restored the two sentences from Tanaka Senshō’s genpon text (while leaving off the digression that follows in that version of the entry) -- enclosed in doubled brackets to indicate that they were not originally part of this kaki-ire (as it is marked in Shibayama’s commentary).

The genpon text clearly has merged these two kaki-ire into one, though the entire ending of Shibayama’s text is completely missing from that source*. Since it would not be possible to suggest a reason why these several versions have ended up in disarray, the only solution seemed to be to translate them all, so that the reader may avail himself of their teachings. ___________ *The rest of the entry has been so abbreviated that, at first glance, it appears to be unconnected with Shibayama’s version. (In Tanaka’s genpon, the kaki-ire was not even segregated from the text of the entry -- as can be seen in the appendix that was attached to the previous post, where his version was translated in its entirety.)

¹Nagaita no furo mo, mizusashi mo, tai-yō ni kakari de jō-jū no mono yue, chū-ya no sa-betsu nashi [長板ノ風爐モ、水指モ、躰用ニカヽリテ常住ノモノユヘ、晝夜ノ差別ナシ].

Nagaita [長板]: as was explained in the previous post, nagaita [長板] refers to the ji-ita of the daisu. The object we call a nagaita today (a long board -- usually painted with shin-nuri -- on which the furo and mizusashi, and sometimes some of the other kaigu, are arranged, as a sort of step in between the daisu and the shiki-ita) is called a naka-ita [中板]* in the Nampō Roku.

Furo mo, mizuashi mo, tai-yō ni kakarite jō-jū no mono yue [風爐も、水指も、躰用に掛りて常住のものゆえ]: both the furo and the mizusashi cross multiple kane (the furo crosses three yin and two yang kane; the mizusashi crosses two yin and one yang kane†) -- on account of their sizes, this state is unavoidable (jō-jū [常住] means “it is always so”). Since these kane must necessarily include at least one yang kane in each case, the object is counted as yang, so far as kane-wari is concerned.

As was explained in the previous post, tai [躰] and yō [用] were used by the machi-shū to refer to the yang and yin kane, respectively. This was based on the understanding that objects were traditionally displayed on the yang kane (hence tai, which means shape, the physical form), while they occupy the yin (yō, meaning use) kane during the temae‡.

Chū-ya no sa-betsu nashi [晝夜の差別なし] means there is no difference between (what is done in) the daytime and at night.

There is no way to arrange the mizusashi, or the furo, so that they would contact only yin kane -- or only yang kane. Consequently, it being impossible to render them uniquely yin or yang**, they are accepted as they are, meaning that there is no difference in the way they are arranged for yin occasions (such as when chanoyu is performed after dark) versus yang occasions (such as when the gathering is held during the daytime).

In other words, because the furo and mizusashi each cross multiple kane, on account of their large sizes, their “yin” or “yang” nature cannot be manipulated by associating them with different kane (the way smaller objects, like the chaire, chawan, habōki, or futaoki, can). Thus, since there is no way to associate them exclusively with yin or yang, their placement remains the same regardless of whether it is a yin (for example, night) or a yang (such as daytime) occasion. __________ *This is made even more difficult -- and it is probably the reason for the way the modern terminology deviates from what we find in this source -- by the fact that, when written in katakana, the dakuten [濁点] (the two small dots that change ka [カ] into ga [ガ]) are frequently omitted (even when they would logically be necessary to differentiate the name of the one object from the other) in documents written during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

†For example, some scholars have argued that, because the furo contains the fire (which is the ultimate yang element), it crosses two yang-kane (which, because 2 is a yin number, this makes the vessel “less yang”); while the mizusashi, which contains water (the ultimate yin element), crosses one yang-kane (making the vessel primordially yang).

Others claim that the total of the kane (for the furo, 3 yin plus 2 yang is 2 + 2 + 2 + 1 + 1 = 8, which, in the I-ching [易經] is the number representing a preponderance of yin; while the mizusashi has 2 yin plus 1 yang, and so 2 + 2 + 1 = 5, which, in the same source, represents the stable yang) causes the vessel to counterbalance the nature of the element it contains (Tanaka dives into these theories deeply, even though such speculations have nothing to do with Rikyū or his period).

Ultimately, this is simply Edo period speculation (stimulated by the introduction of neo-Confucian yin-yang theory that was introduced from Korea at the beginning of the seventeenth century), because originally there were only the five yang-kane! (Also, given that there has to be room for the shaku-tate and koboshi as well as the furo and mizusashi between the four legs of the daisu, it is not physically possible to move any of these utensils around too much.)

In the final analysis, the number of kane an object crosses is irrelevant. If an object crosses one or more yang-kane, it is yang (for the purpose of kane-wari); if it only rests on a yin kane (or, to say it another way, in the space between two yang kane without contacting either of them), it is yin.

‡The reader must understand that there were several different systems at use during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, sponsored by different machi-shū factions, and that they cannot be reconciled. Any attempt to do so (as was attempted by certain Edo period -- and even some modern -- scholars) will inevitably lead to confusion.

**The way a chaire or chawan could be made yin by simply avoiding any contact with a yang kane.

At night, and on yin occasions (such as memorial services), the chaire and chawan are displayed on yin kane. During the daytime, and on festive occasions, these smaller utensils are carefully placed on yang kane. It is the way these things are handled that modify the yin or yang nature of the entire daisu-kazari.

²Ko-zashik no mizusashi mo, kore ni yorite chū-ya tomo ni, kokorotsukai-sezu oku-beshi nari [小座敷ノ水指モ、此ニヨリテ晝夜トモニ、コヽロツカヒセズ可置也].

Kore ni yorite [これに依りて] is referring to the previous sentence, where it was explained that, because the mizusashi used on the daisu crossed multiple kane, it could not be defined as exclusively yin or yang, and so its placement could not be modified depending on the yin or yang nature of the gathering.

In other words, because the mizusashi used in the small room is also usually of the same size as that used on the daisu (if not larger: the reader should recall that, in the small room, the mizusashi was supposed to be large enough that it would hold enough water for the whole day’s chanoyu, without needing to be replenished -- since opening the lid to add more water would allow dust to enter as well), it will naturally cross several kane. Thus, since it cannot be manipulated so that it is exclusively yin or yang, its placement cannot be changed based on the yin or yang nature of the gathering.

³Tai futatsu kakareba mochiron kuguru-kane ni te sumu-koto nari [躰二ツニ掛レバ勿論クヽルカネニテスムコトナリ].

Tai futatsu kakareba [躰二つに掛れば] means if (it) crosses* two tai (yang) kane....

Kuguru-kane [潜るカネ] describes the situation where an object crosses two or more successive kane.

Mochiron kuguru-kane ni te sumi-koto nari [勿論潜るカネにて濟むことなり] means naturally, since it (crosses) successive kane†, there is nothing more that needs to be said. “Kuguri-kane” means the object is always yang.

In other words, when an object crosses several kane, at least one of them will be a yang kane, thereby rendering the object yang. So there is no question of what the result will be. __________ *Kakaru [掛る], more literally, means things like to hang on, lean against, recline upon, be caught on, be fastened to, and so forth.

†Kuguru [潜るカネ] is a verb, so kuguru-kane would mean kane that succeed one another.

The form most commonly seen in the Nampō Roku is kuguri-kane [潜りカネ], which is the nominal form of the word. Kuguru-kane is an anomaly.

⁴Tai hitotsu, yō hitotsu ni kakarite mo kurushi-karazu [躰一ツ、用一ツニ掛リテモ不苦].

Tai hitotsu, yo hitotsu ni kakarite mo [躰一つ、用一つに掛りても] means “also, if (the mizusashi) rests on one tai (yang) kane and one yō (yin) kane....”

Kurushi-karazu [苦しからず] means there is no problem. So long as the mizusashi (or other object) touches one yang kane, the object is rendered yang (for the purposes of kane-wari). The other kane (whether just one yin kane, or several kane of various sorts), are essentially irrelevant, since contacting one yang kane is all that is important.

⁵Ko-buri ni te yin-bakari ni kakaritaru mizusashi ha hiru yō kokoro subeshi [小フリニテ陰バカリニ掛リタル水指ハ晝用心スベシ].

Ko-buri ni te [小振りにて] means if (the mizusashi) is small-sized....

The space between the heri on a kyōma tatami* is (exactly) 2-shaku 9-sun 5-bu. Dividing this by six means that there are 4-sun 9.16666666666667-bu between the yang kane. A “small-sized” mizusashi would be one that measures 4-sun 9.16-bu in maximum diameter (or less).

In bakari ni kakaritaru mizusashi ha hiru-yō kokoro-subeshi [陰ばかりに掛りたる水指は晝用心すべし] means “you should consider† that a mizusashi (that is so small) that it only contacts a yin(-kane) should be used only during the daytime. __________ *This idea would not work on an inakama tatami, and a mizusashi that would fit between kane in that setting would be too small to use (too narrow for the hishaku to be used to dip out water).

Furthermore, this kind of thing would only be done in a small room, where the mats are always based on the kyōma tatami.

†Or, be careful. Kokoro [心], in constructions like kokoro-subeshi [心すべし], is referring to the mind, to someone’s mental activity. This expression means to think about something, to take (some advice) to heart, to reflect carefully about something, and so forth. In other words, one should consider the advice very carefully, and use it to guide to ones actions.

⁶Ko-mage no mizusashi, ko-buri no mizusashi tomo ha, mitsu-gumi wo tsuzuki ni awasete oki-sōrawan tote no koto nari [小曲ノ水指、小フリノ水指共ハ、三ツ組ヲツヾキニ合セテ置候ハントテノコトナリ].

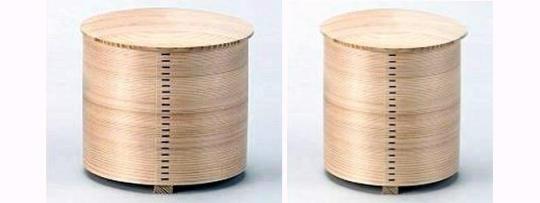

Ko-mage no mizusashi [小曲の水指]: a mage-mono mizusashi [曲げ物水指] is one made of unpainted bentwood. A ko-maga mizusashi [小曲げ水指] is a mizusashi of this type of smaller than usual size. The lid of the one made for Rikyū measures 4-sun 9-bu in diameter* (with the body a little smaller, since the lid projects about 2-bu or so beyond the outer side of the body -- this is to facilitate its easy removal, since the lid does not have a handle). In the photo below, an ordinary mage-mono mizusashi (6-sun in diameter) is shown on the left; a ko-mage mizusashi is shown on the right.

Ko-buri no mizusashi [小振りの水指] is a mizusashi of the same size, but made of ceramic (or some other material, other than bentwood). Some have tomo-buta, while others have lacquered lids.

The elongated mizusashi often sold for used in the autumn (for naka-oki [中置き] and temae of that sort†) are usually 4-sun 9-bu in diameter (though sometimes they are a little wider).

Mitsu-gumi [三つ組を續きに合せ] means an arrangement where three utensils are displayed together. The expression mitsu-gumi is used to describe various arrangements in the Nampō Roku; however, here it is referring to the arrangement depicted below.

Mitsu-gumi wo tsuzuki ni awase [三つ組を續きに合せ]: this means that the three utensils are associated with successive (kane)‡.

The chawan and chaire are associated with the yang-kane on both sides of the yin-kane on which the mizusashi is resting. So, rather than the mizusashi and chaire being counted together as one (yang) unit, here the mizusashi, chaire, and chawan count as three units, with a total of 1 + 2 + 1 = 4 (yin), for purposes of kane-wari. __________ *According to entry 62 in Book Seven of the Nampō Roku.

†The idea is that the furo is usually placed on the side of the mat farthest away from the guests. Therefore, as the autumn begins to deepen, and the room starts to feel a little chilly, the host moves the furo to the middle of the mat -- so that it will seem to be giving more warmth to the guests (in fact, at a distance greater than 5- or 6-sun from the side of the furo, no difference in temperature can usually be perceived).

Such temae were not sanctioned by Rikyū, because he preferred positioning the furo on the side of the utensil mat closest to the guests, even in his 2-mat rooms (in fact, usually he placed it on top of the lid of the mukō-ro in that setting, so that the mouth of the kama would be lower).

Rikyū taught that the height of the mouth of the kama above the surface of the mats was directly related to how “shin” [眞] the arrangement was:

◦ In the case of the daisu, which is the most shin arrangement, the furo rests on the ji-ita, which is 1-sun 5-bu thick.

◦ The nagaita and various shiki-ita are 6-bu thick, so when the furo is arranged on one of these, its mouth is around 9-bu lower. These were considered gyō [行].

◦ The large iron furo, which was originally the only kind of furo permitted in the small room, was placed directly on top of the lid of the mukō-ro (which was level with the surface of the mats). Thus it approaches closer to the sō [草] condition.

◦ The mouth of the kama in the ro is just 6- or 7-bu above the surface of the mats, so the irori is thoroughly sō.

◦ And, when the uba-guchi kama is arranged in the ro, its mouth is 6- or 7-bu below the surface of the mats, making the room in which it is used the most informal kind of setting for chanoyu possible.

These were his teachings.

‡Importantly, none of the utensils should inadvertently contact any other kane but the one with which they are associated. So the mizusashi has to be placed carefully, so it does not contact the yang-kane on either side. And, likewise, the chawan should not touch the yin-kane on which the mizusashi is arranged.

In addition to the ko-mage mizusashi, Rikyū used a small black Raku bowl (o⋅guro [オ⋅グロ = 小黒]) and his Shiri-bukura chaire [尻膨茶入] when undertaking this kind of arrangement. These were the utensils shown in the photo.

Rikyū had a pair of black Raku bowls that he frequently used together: he referred to them collectively as o・guro [オ・グロ]. The small bowl (which was 3-sun 8-bu in diameter) was named oguro [オ⋅グロ = 小黒], which meant “little black;” and the larger bowl (4-sun 1- or 4-sun 2-bu in diameter) was named ��guro [オ-グロ = 大黒], meant “large black.”

Rikyū wrote the name with a sort of dot in between the two kanji, the dot either being interpreted as a separation mark, or an elongation mark, thus changing the first word from o [オ], small, to ō [オ-], large.

Unfortunately, the larger bowl was broken early on, so only the small bowl survived -- albeit with its epithet interpreted as “large black.” (It is actually the smallest of Chōjirō’s several black bowls.)

⁷Jōtai no ha go-sun-yo, roku-sun no hari yoshi [常躰ノハ五寸餘、六寸ノハリヨシ].

Jōtai no ha [常躰のは] means “as for the ordinary kind (of mizusashi)....”

Go-sun-yo [五寸餘] means larger than 5-sun.

Roku-sun no hari yoshi [六寸の張りよし]: the verb haru [張る] means to stretch or spread across (a certain length or distance); therefore, roku-sun no hari yoshi means it is better if (the mizusashi) is 6-sun (in diameter) or a little more.

⁸Chō-ya tomo ni jōza nari [晝夜共ニ定座ナリ].

Jōza [定座] means an object’s fixed or regular seat; the spot were it is usually placed*.

In other words, whether the gathering is taking place during the daylight hours, or after dark, an ordinary mizusashi should be placed in exactly the same way. There is no difference, because it is of such a size that it covers several kane†. __________ *This word, like many of the somewhat strange expressions encountered in this passage, employs a uniquely Edo period sort of idiom. In the modern world, this word is not used in this way.

†Only objects that can be restricted to just one kane have their positions changed according to the yin or yang nature of the gathering.

In addition to the daylight hours, yang gatherings include those hosted in honor of auspicious or celebratory occasions, as well as gatherings held at Shintō shrines and the like. Yin gatherings are those held after dark, as well as those on memorial occasions (such as the anniversary of someone’s death), and (depending on the host’s way of thinking about this) when offering tea to the Buddha.

On yin occasions, the shoza should be yang, and the goza should be yin; on yang occasions, the shoza should be yin, and the goza should be yang.

⁹Kaku no gotoki mu-zan furo no oki-kata kokoro-e kan-yō nari [如此無殘風爐ノ置方心得肝要也].

Kaku no gotoki [かくのごとき] means in the same way; according to the same kind of thinking; like this....

Mu-zan furo [無殘風爐] means a distressed, wretched, or ugly furo. While it obviously means that the furo is unattractive (at least according to the usual standard of aesthetics, where perfection is preferred), the precise reason why is unclear. Perhaps it was a damaged piece (chipped, cracked, or rusted); or perhaps it was an exceptionally “wabi” sort of piece (one of very low quality -- functional, but nothing more*). The concern seems to be whether it still can be used as usual, or is best kept as far out of sight as possible.

Kokoro-e kan-yō [心得肝要] means it is crucial to understand (how to use this kind of furo). __________ *We must remember that the original Dōan-buro [道安風爐] was thought of in exactly this way.

The first Dōan-buro was a mayu-buro [眉風爐] that had gotten its mayu (the span of clay that crosses above the himado) cracked or broken (something that was not especially unheard of, since many people tended to grab the mayu as if it were a handle, which sometimes resulted in its developing a crack -- or even breaking off completely -- meaning that it would then be thrown away), and so had been tossed in the dump. Dōan (who was a teenager at the time) dragged it home, and set about sawing off the remainder of the mayu, and sanding the newly cut edges to make the hi-mado uniform in size and shape (after which he probably painted or rubbed it all over with lacquer). This was possible because do-buro [土風爐] are made from very low-fired clay that can be worked with a hand-saw and metal file (if one is careful); and chajin often worked with this kind of material to fabricate things that they needed (in Rikyū’s period, for example, the mae-kawarake [前土器] was usually made by the host out of a round sake-saucer -- by cutting off one end with this same kind of saw).

Here, a mayu-buro is shown on the left, and a Dōan-buro, on the right.

This was so shocking to see (to people who had never seen such a thing) that it prompted Rikyū to make two suggestions:

◦ first, because at that time the gotoku was used with the ring uppermost, with the three feet resting on top of the hai-gata, he told Dōan to cut off the part of the ring that crossed the now open space where the mayu had formerly been (originally the ring was hidden by the mayu, which is why the mayu was there);

◦ and second, he felt that it was completely unreasonable to use an ordinary habōki to dust this wretched furo -- so, rather than a habōki, a single feather, without a handle, should be used (as if it, too, had been picked up off the ground somewhere, and used as it was). When these two things were done, Rikyū accepted that it could be used -- but only during the most wabi of gatherings, where all of the utensils were merely functional, and the focus of the chakai was wholly on the tea, and nothing else.

¹⁰Isshaku yon-sun za ni suete, kimen ni te mo amatsura ni te mo kan-tsuki wo san-bun-ichi hineri-komu-koto nari [一尺四寸座ニスヱテ、鬼面ニテモアマツラニテモ鏆付ヲ三分一ヒネリ込ムコトナリ].

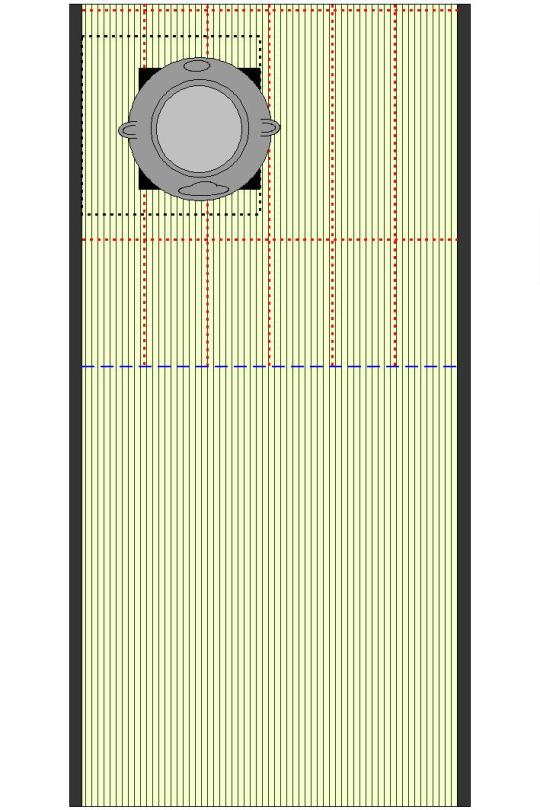

Isshaku yon-sun za ni suete [一尺四寸座に据えて]: the “seat of the furo” is a 1-shaku 4-sun square, demarcated from the inner edge of the heri closest to the furo. In this sketch, the “seat of the furo” has been outlined with a dashed black line*.

When a large kimen-buro is placed on a ko-ita [小板]†, with the ita 5-sun away from the far end of the mat, the arrangement will be as shown above. Note that the shiki-ita is moved to the inner edge of the 1-shaku 4-sun “seat of the furo,” and that the “seat of the furo” corresponds to the location of a mukō-ro (though with the heri restored to its original location). These details are all implied by the phrase isshaku yon-sun za ni suete.

Kimen ni te mo ama-zura ni te mo kantsuki wo san-bun-ichi hineri-komu koto [鬼面にても案摩面にても鐶付を三分一捻り込むこと]: usually the word kimen is assumed to refer to the devil-faces of the kan-tsuki, but this construction seems to be referring to the “face” of the furo‡. The word ama-zuma [案摩面]**, likewise, is describing the appearance of the “face” of a (different sort of) furo. Presumably one of these terms actually referred to the “face” of a kimen-buro (likening it to a devil-mask?), while the other to another sort of furo (perhaps a Chōsen-buro [朝鮮風爐]; or possibly even to something like a Dōan-buro [道安風爐]). Regardless, the meaning is that, whatever fanciful shape the profile of the furo suggests, it should be turned so that it is oriented toward the host’s seat -- by turning the kan-tsuki by one-third. __________ *These drawings are extremely accurate -- down to the me on the mat. Assuming your mat has been made properly, drawings of this sort can be used as a guide for the arrangements.

†This was the furo for which the 9-sun 5-bu square ko-ita was created by Jōō; and, originally, this (and other furo created for use on the o-chanoyu-dana [御茶湯棚]) was the furo sanctioned for use in the small room.

‡This way of referring to the front-facing side of (presumably) the kimen-buro as a kimen [鬼面] (which litereally means “devil’s face,” and was the name of a variety of nō [能] mask) is seen only here, to the best of my knowledge. It appears that the comentators have generally taken kimen to be a reference to the kan-tsuki.

An example of a kimen mask is shown above.

**See footnote 12 in the previous post, Nampō Roku, Book 7 (58b): the Way to Position the Various Utensils (the Toku-shu Shahon [特殊写本] Version); and its First Kaki-ire, for a photograph of this kind of mask compared with the “face” of a kimen-buro. The URL for which is:

https://chanoyu-to-wa.tumblr.com/post/714068300122947584/namp%C5%8D-roku-book-7-58b-the-way-to-position-the

¹¹Furo wo oku ni iruru-koto ni te ha nashi [風爐ヲ奧ニ入ルヽコトニテハナシ].

Furo wo oku ni ireru-koto ni te ha nashi [風爐を奧に入れることにては無し] means the furo should not be pushed deeper (toward the far end of the mat).

While the sketch shown in the previous footnote depicts the arrangement that was decided upon by Jōō and Rikyū, we must remember that this kaki-ire was written in accordance with the machi-shū tradition that ultimately derived from the teachings of Imai Sōkyū.

Though the author has not provided us with sufficient details to be able to say definitively what his intended meaning might be, the best interpretation of this sentence would be that, assuming the reference is to a 4.5-mat room*, the author might be suggesting that the ko-ita furo should be placed out on the utensil mat so that the furo is roughly in the same place as it would be were it arranged on a daisu†.

The difference would be that the “seat of the furo” is 4-sun 5-bu from the far end of the mat (this is the way the daisu is oriented on the utensil mat), rather than 2-sun 5-bu as in Jōō’s arrangement; so the far edge of the ko-ita would be 7-sun from the far edge (rather than 5-sun, as in Jōō’s teachings), which moves everything closer to the center of the mat by 2-sun‡. ___________ *While some schools do things in this way even in a small room, the general trend, at least during the 20th century, was to move the ko-ita furo toward the far end of the utensil mat, more or less as envisioned by Jōō and Rikyū.

†Of course, the furo used on the daisu in the kyōma would have been a medium sized kimen-buro, rather than the large-sized furo that is the furo sanctioned for use on the ko-ita. However, these distinctions had been forgotten by the time this kaki-ire was written.

While the original furo were made of metal (usually Korean bronze; though large furo for the o-chanoyu-dana had been cast from iron in Japan since the fourteenth century), ceramic Nara-buro (and later, mayu-buro) of the same diameters began to appear during the second half of the fifteenth century. The large furo was 1-shaku 2-sun in diameter; the medium furo was 1-shaku in diameter (this is the most commonly seen size today, even though furo of this sort were only supposed to be used on the daisu); and the small furo was around 9-sun in diameter.

Regarding the use of these different sizes of furo (regardless of whether they were bronze kimen-buro or Chōsen-buro, or lacquered ceramic Nara- or mayu-buro -- all of which were used on the daisu or o-chanoyu-dana), the original rules were:

◦ The medium furo was used on the large daisu; it could be used only in the kyōma, and was not supposed to be used except on the daisu.

Jōō subsequently created the shi-hō-ita [四方板] (which measured 1-shaku 2-sun by 1-shaku) for the medium furo; but this was originally used only during the shoza, for the sumi-temae. When serving tea, the furo was supposed to be placed on the daisu. Later, however, Jōō decided that the daisu could be done away with, and he served tea with the medium furo resting on a shi-hō-ita. This could be done only in a room of 4.5-mats or larger.

◦ The small furo was used on the small daisu, which was originally used only in the inakama. Later, however, the small daisu could be used in either the kyōma or the inakama; but by Jōō’s last years, this furo was also being used apart from the daisu, on a 1-shaku 3-sun square ō-ita [大板]).

The ō-ita furo could only be used in a room of 4.5-mats or larger.

◦ The large furo was originally used only in the o-chanoyu-dana (which was a recessed area, 3-shaku 1-sun 5-bu wide by 1-sun 5-bu deep, installed in the wall of the 2-mat tsugi-no-ma that was always attached to a shoin, where tea was prepared. After Yoshimasa’s storehouse had been destroyed, the only utensils that remained for his use were those that were present on the o-chanoyu-dana. During the period of his second retirement (1589 ~ 1590), desiring to serve tea to his retainers with his own hands in his shoin, Yoshimasa arranged the large furo from his o-chanoyu dana on a naga-ita [長板] (a board that measured roughly 2-shaku 6-sun 5-bu by 1-shaku 1-sun -- though, since these boards were made from the ten-ita of an old daisu that could no longer be used, the actual dimensions depended on the four holes for the legs that were bored into the underside, since the edges of the naga-ita generally were cut to the inner corner of those holes -- this should not be confused with the word nagaita [長板] that means the ji-ita of the daisu, even though the kanji are the same). So, when the large furo was used in the tearoom, it originally was placed on a naga-ita.

In an effort to protect Yoshimasa’s original naga-ita (which had come into his possession), Jōō created the ko-ita for the furo, originally to provide a base for it during the shoza (when the sumi-temae was performed), with the ko-ita being replaced by the naga-ita during the naka-dachi. Later, Jōō kept the large furo on the ko-ita until the end of the gathering, with the mizusashi placed directly on the mat beside it. It was at this time that Jōō articulated the rule that the ko-ita should be placed 5-sun from the far end of the mat, just as had been done with the naga-ita; and it was also at this time that Jōō said the ko-ita should be moved to the innermost side of the “seat of the furo” (while the mizusashi was moved to the innermost side of the “seat of the mizusashi”) because the shaku-tate and koboshi were no longer present in between them.

While the ko-ita was originally intended for use in rooms of 4.5-mats or larger, it came to be used in the small rooms as well (because the small size of the board seemed somehow appropriate). This was the only furo that was allowed to be used in the small room -- a convention that seems to have fallen into disuse only during the 20th century.

‡For the author of this kaki-ire to argue that the furo should not be pushed closer to the wall implies that he was not aware of the above cited precedents.

¹²Chaire, temmoku, futaoki no koto, taitei migi ni shirusu to iedomo, temae [h]e narite hatarakite ha koma-goma kane wo iu-koto ni te nashi [茶入、天目、蓋置ノコト、大抵右ニ記スト云ヘ共、手前ヘナリテ動キテハコマ〻〻カネヲ云フコトニテナシ].

Chaire, temmoku, futaoki no koto [茶入、天目、蓋置のこと]: up to this point the text of this kaki-ire has been focused on the furo and the mizusashi. Now it will shift its narrative to the chaire, temmoku, and futaoki (and the way they are handled on the mat).

Taitei migi ni shirusu to iedomo [大抵右に記すと云えども] means even if (the way they are handled) is generally as was recorded on the right (that is, in the preceding sections)....

Temae [h]e narite [手前へなりて] means when we enter into the temae; after we have begun the temae....

Hataraki de ha koma-goma kane wo iu-koto ni te nashi [動きでは細々カネを云うことにてなし]: hataraki de ha [動きでは] means with respect to (the host’s) actions*; koma-goma kane wo iu-koto ni te nashi [細々カネを云うことにてなし] means we do not (usually) have occasion to speak about (iu-koto ni te nashi [云うことにてなし]) how (the host’s) movements (hataraki de ha [動きでは]) are effected by the details of the kane (koma-goma kane wo [細々カネを]) -- here, kane should be understood as an allusion to kane-wari.

In other words, kane-wari is primarily employed while arranging the utensils -- on the daisu, or on the utensil mat -- before the temae. During the temae, this text argues, the kane have little or no impact on what the host is doing†. __________ *Hataraki [動き] has several different shades of meaning, in the context of chanoyu. Here the word is referring specifically to the host’s physical motions or actions (and the way those are or are not constrained by kane-wari), as he goes through the process of performing the temae.

†However, while this remains the attitude of the modern schools (though most would probably doubt that kane-wari plays much of a role even in the arrangement process), we must remember that the kane were originally derived from the folds and edges of the shiki-shi [敷き紙]. And since the shiki-shi was the stage (as it were) on which the temae was performed, the kane (and, in particular, the central kane and the outermost two) do constrain the hosts movements -- if only because they served to confine the principal utensils to being manipulated upon the surface of the shiki-shi.

A total ignorance of the shiki-shi is what separates the modern machi-shū derived chanoyu from the original form of the practice.

Even though the daimyō schools originally represented an attempt to return chanoyu to the form that of the practice their ancestors had received directly from Rikyū, Sōtan’s machi-shū chanoyu had simply been around too long, and had impacted the initiation, basic training, and practices of virtually everyone in any way connected with chanoyu during the first century of the Edo period (necessarily including all of the daimyō who were involved in this movement), so that, in effect, what they ultimately produced was a modified version of Sōtan’s machi-shū practice (which was ultimately based on the teachings of Imai Sōkyū), overlaid by a patina derived from the fragmentary elements of Rikyū’s chanoyu that had been preserved in the individual densho that had been received by their ancestors from the master (this is why, though they all professed to be trying to do the same thing -- restore the chanoyu of Rikyū -- the different daimyō schools ultimately came to differ so greatly from each other).

Since none of his densho is anything like a complete treatise on chanoyu (each tends to address the specific question that the recipient had addressed to Rikyū, and little more), it was not possible to collate these disparate teachings into anything resembling a manual explaining the kind of chanoyu that Rikyū actually practiced and taught until after Suzuki Keiichi published the Sen no Rikyū zen-shū (in Shōwa 16 [昭和十六年], 1941). And by that point in time, the various schools were all so rigid in their individual approaches -- something that was only magnified by the intense competition for students that resulted following the loss of their daimyō sponsors, and then exacerbated by the unprecedented influx of generations new, and almost exclusively female, students (once chanoyu came to be promoted as the proper way to train a young woman to be a “proper” Japanese wife in the early 20th century). As a result, rather than welcoming these revelations (and the opportunity to correct the errors that had accumulated over the centuries that they offered), they were rejected outright and in toto (since many of the major schools had staked their claim of legitimacy on the assertion that their traditional approach already represented Rikyū’s authentic vision of chanoyu).

¹³Taigai no kokoro kane nari [大概ノ心カネナリ].

Taiga no kokoro kane nari [大概の心カネなり] is very difficult to translate. The meaning (which follows from the preceding sentence) is that, while the kane do not control the temae, the host must never completely forget about them either. (Though why this should be so is not explained in the text.)

This possibly hints at a subconscious recognition of the argument made in sub-note “†” in the previous footnote: “the kane (and, in particular, the central kane and the outermost two) do constrain the hosts movements -- if only because they served to confine the handling of the principal utensils to” the space that is defined by them. That this space originally represented the shiki-shi, or whether it was simply an abstract construct (as the author of this passage seems to believe), is not really relevant to the argument being made in this entry (there is no evidence that the actual shiki-shi was ever used, for chanoyu, in Japan*). Nevertheless, for whatever reason, there was a recognition that the kane do constrain the host’s actions -- even if that recognition was not expressed in words. __________ *The earliest temae for which there exists sufficient evidence to allow us to recreate it, the san-shu gokushin-temae, uses the Gassan nagabon [月山長盆] to control the placement of the utensils on the mat during the temae. Centering the chaire (which measures 2-sun 2-bu in diameter) on this tray places it immediately to the left of the rightmost kane; and handling the dai-temmoku (the temmoku used for this temae should measure 3-sun 8-bu in diameter; the dai should be 5-sun 2-bu in diameter) immediately to the left of the tray locates the foot of the temmoku-chawan immediately to the right of the central kane.

We can not say how the temae (whether using the daisu, or the o-chanoyu-dana) was performed at any point prior to this.

¹⁴Futaoki itsumo nagaita yori shita [h]e oroshite yoshi [蓋置イツモ長板ヨリ下ヘオロシテヨシ].

Futaoki itsumo nagaita yori shita [h]e oroshite yoshi [蓋置何時も長板より下へ下ろしてよし] means it is better if the futaoki is always lowered (from the ji-ita).

¹⁵Hoya ha mochiron nagaita no ue nari [ホヤハ勿論長板ノ上ナリ].

Hoya ha mochiron nagaita no ue nari [ホヤは勿論長板の上なり] means “the hoya should naturally be (kept) on the nagaita” -- that is, the hoya should remain on the ji-ita during the temae (except when some special usage associated with the temmoku or chaire would interfere with this).

¹⁶Chaire, chawan no rui, temae no toki, nagaita no ue [h]e yaru-koto tsune ha nashi [茶入、茶碗ノ類、手前ノ時、長板ノ上ヘヤルコト常ニハナシ].

Chaire, chawan no rui [茶入、茶碗ノ類] means the class of objects like the chaire and chawan. In other words, the smaller objects used to prepare and serve the tea.

Nagaita no ue [h]e yaru-koto tsune ha nashi [長板の上へ遣ること常には無し] means that such objects are ordinarily not moved onto the ji-ita (during the temae).

While this is not always so in the versions of the classical temae taught by many of the modern schools*, it was the case during Rikyū’s period (and, indeed, during much of the Edo period, too). __________ *For example, several of the schools teach that the temmoku should be stood on the ji-ita temporarily while the host cleans the temmoku-dai with his fukusa. The necessity of doing so means that having the futaoki also standing on the ji-ita complicates things unnecessarily.

¹⁷San-shu gokushin nado no toki suru-koto nari [三種極眞ナドノ時スルコトナリ].

San-shu gokushin nado no toki [三種極眞などの時] means on occasions when (the host is performing) things like the san-shu gokushin temae....

Suru-koto nari [爲ることなり] means (something) is done.

In other words, during temae such as the san-shu gokushin, the chaire and temmoku are occasionally moved onto the ji-ita temporarily (while the host is cleaning the Gassan-nagabon, and the temmoku-dai, respectively).

On such occasions, some say that the futaoki should be moved a little closer to the furo, so there is enough room for the chaire or temmoku*. __________ *Also, the utensils that have been used since the Edo period tend to be larger than those used in earlier periods. This is especially true of the temmoku (Edp period examples measuring between 4-sun and 4-sun 2-bu in diameter) -- since the machi-shū preference for serving koicha as sui-cha [吸い茶] (one bowl of koicha is passed around and shared by all the guests) became generally accepted at that time.

The classical temmoku tended to be much smaller (around 3-sun 8-bu in diameter), since (from the beginning, when the purpose was to offer tea to the Buddha) only a single portion of tea was going to be prepared in it.

The beginning of something resembling modern-day chanoyu started when one of the people present was invited to drink the tea after it had been offered to the image of the Buddha (so it would not go to waste).

Even in the Ashikaga period, koicha was still being served in this way (the nobleman drank the bowl of koicha, with anyone else present being served usucha afterward).

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

why do all the obey me character songs eat

Nā omae ni totte no

Daijina mono tte nani?

Ima sore o tottemo

Shiritai no ni

Mada ne teru yo yume no naka

Dare to iru no ka na

N? Iya mateyo yume no naka

De sae neteru kamo

Taida sugite zurui kedo

Sore wa sore de ī ne

Oh, loving you

La la, sekaijū

Furimuka seru miryoku ga ippaida na

Mabataki suru tōto sugiru

Ore ni dake ni zenbu

Nē, boku ni totte no

Tokubetsu na wagamama

Ima sore wo tottemo

Tanomitai no ni

Mata tabe teru hara no naka

Dō natte iru no sa

Nemuke ga sa kuru mae ni

Kikasete hoshī kedo

Shibaraku wa kakari sou

Chotto yoko ni naru ka

Oh, feeling me

La la, dōka shiteru

I ga uchū minna muchū ni naru ne

Yasashisa ga good, kinniku ga mood

Boku ni dake ni zenbu

Beru sa, moshikashite kono kyoku

Boku no koto utattenai?

Hm? Son'na wake naidaro

Ah... chizubaga ga tabetai

Berufe kai ni ikou

Mo tabe terujan

Sore wa so to, omae, kono kyoku

Ore no koto utatteruadaro?

La la, sekaijū

Furimuka seru miryoku ga ippaida na

Mabataki suru tōto sugiru

Ore ni dake ni zenbu

La la, dōka shiteru

I ga uchū minna muchū ni naru ne

Yasashisa ga good, kinniku ga mood

Boku ni dake ni zenbu

1 note

·

View note

Text

2024 olympics Greece roster

Athletics

Emmanouil Karalis (Athens)

Miltiadis Tentoglou (Grevena)

Mihail Anastasákis (Chania)

Christos Frantzeskakis (Athens)

Polyniki Emmanouilidou (Thessaloniki)

Antigoni Drisbioti (Karditsa)

Katerina Stefanidi (Cholargos)

Eleni-Klaoudia Polak (Athens)

Ariadni Adamopoulou (Athens)

Tatiana Gusin (Athens)

Panagiota Dosi (Corfu)

Elina Tzengko (Nea Kallikrateia)

Stamatia Scarvelis (Santa Barbara, California)

Basketball

Thomas Walkup (Deer Park, Texas)

Giannoulis Larentzakis (Kythnos)

Dimitrios Moraitis (Maroussi)

Vassilis Toliopoulos (Athens)

Nick Calathes (Winter Park, Florida)

Panagiotis Kalaitzakis (Heraklion)

Georgios Papagiannis (Megara)

Vassilis Charalampopoulos (Maroussi)

Konstantinos Papanikolaou (Trikala)

Niko Chougkaz (Athens)

Giannis Antetokoumpo (Athens)

Konstantinos Mitoglou (Thessaloniki)

Cycling

Georgios Bouglas (Trikala)

Equestrian

Ioli Mytilineou (Athens)

Fencing

Theodora Gkountoura (Athens)

Gymnastics

Leftherios Petrounias (Athens)

Judo

Theodoros Tselidis (Vladikavkaz, Russia)

Elisavet Teltsidou (Athens)

Rowing

Stefanos Ntouskos (Ioannina)

Antonios Papakonstantinou (Marousi)

Petros Gkaidatzis (Thessaloniki)

Evangelia Anastasiadou (Kastoria)

Christina Bourmpou (Thessaloniki)

Dimitra Kontou (Mytilene)

Zoi Fitsiou (Kozani)

Sailing

Cameron Maramenides (Anna Maria, Florida)

Osysseas Spanakis (Amarousio)

Byron Kokkalanis (Athens)

Ariadne Spanaki (Thessaloniki)

Shooting

Charalampos Chalkiadakis (Chania)

Efthimios Mitas (Athens)

Christina Moschi (Athens)

Emmanouela Katzouraki (Chania)

Anna Korakaki (Drama)

Swimming

Stergios Bilas (Amarousio)

Apostolos Siskos (Thessaloniki)

Panagiotis Bolanos (Athens)

Konstantinos Stamou (Athens)

Evangelos Ntoumas (Alexandroupoli)

Kristian Gkolomeev (Athens)

Apostolos Christou (Athens)

Evangelos Makrygiannis (Athens)

Dimitrios Markos (Athens)

Apostolos Papastamos (Chania)

Odysseus Meladinas (Cholargos)

Andreas Vazaios (Athens)

Konstantinos Englezakis (Marousi)

Athanasios Kynigakis (Chania)

Sofia Malkogeorgou (Athens)

Evangelia Platnioti (Athens)

Anna Ntountounaki (Chania)

Georgia Damasioti (Marousi)

Dora Drakou (Patras)

Table tennis

Gio Gionis (Athens)

Tennis

Petros Tsitsipas (Athens)

Stefanos Tsitsipas (Monte Carlo, Monaco)

Maria Sakkari (Barcelona, Spain)

Despina Papamichail (Barcelona, Spain)

Water polo

Nikos Gillas (Athens)

Emmanouil Zerdevas (Athens)

Konstantinos Genidounias (Athens)

Dimitrios Skoumpakis (Chania)

Efstathios Kalogeropoulos (Amarousio)

Ioannis Fountoulis (Chios)

Alexandros Papanastasiou (Athens)

Stylianos Argyropoulos-Kanakakis (Athens)

Nikolaos Papanikoulaou (Athens)

Konstantinos Kakaris (Athens)

Dimitrios Nikolaidis (Thessaloniki)

Angelos Vlachopoulos (Thessaloniki)

Panagiotis Tzortzatos (Cholargos)

Athina Giannopoulou (Athens)

Maria Myriokefalitaki (Amarousio)

Chrysoula Diamantopoulou (Athens)

Eleftheria Plevritou (Thessaloniki)

Ioanna Chydirioti (Cholargos)

Nikole Eleftheriadou (Athens)

Margarita Plevritou (Thessaloniki)

Eleni Xenaki (Amarousio)

Alexandra Asimaki (Athens)

Maria Patras (Agria)

Eirini Ninou (Glyfada)

Vasiliki Plevritou (Thessaloniki)

Ioanna Stamatopoulou (Marousi)

Wrestling

Georgios Kougioumtsidis (Thessaloniki)

Dauren Kurugliev (Derbent, Russia)

Maria Prevolaraki (Athens)

#Sports#National Teams#Greece#Celebrities#Races#Basketball#Texas#Florida#Animals#Fights#Russia#Boats#Tennis#Monaco#Spain

0 notes

Text

Ολυμπιακός: Επέστρεψε ο Κώστας Κάκαρης!

https://sport.news-24.gr/olybiakos-epestrepse-o-kostas-kakaris/

0 notes

Text

Kanji #294 係

係

Significado: afectar, concernir

Explicación: Es un kanji compuesto por el radical mutante de persona 亻 y el Kanji #277 系.

Nemotecnia: El hilo(系) del destino me (人) ha hecho involucrarme

ON: ケイ / KEI

Kun: かか-, かかり / kaka-, kakari かか*わる = 係わる = involucrarse, quedar atrapado en (generalmente en algo malo) ★★☆☆☆

Ranking de uso: ★★★☆☆

Jukugo:

関係 - kankei - 関 (relación / puerta) + 係 (afectar, concernir) = relación, conexión ★★★★☆

0 notes

Text

How to Plan the Perfect European Vacation

Europe is a very popular place for tourists. Some of the most historically impactful countries in the world are situated there, from the United Kingdom to Russia. There are also a number of very unique and interesting countries with amazing histories like Serbia and Croatia. If you are interested in vesting, make sure you plan each step of your trip. Meticulously planning can prevent anything from going wrong and help you to ensure you enjoy your vacation. This post will explore this topic in more detail, telling you how you can plan your holiday to the European continent. Travel Destinations One of the best things about Europe as a continent is that it is extremely easy to travel around. You can usually just drive over borders without having to present your passport, provided that you have a Schengen Zone pass. According to Pantelis Kakaris, the founder of adventourely.com, Greece is one of the countries you should consider visiting. Make sure that you draw up a list of travel destinations that interest you. Drawing up a list of places to visit will make coordinating your stay much easier after arrival. Be sure to visit as many countries as possible, though. The more places you visit, the more fun you’ll have. Booking Flights If you want to visit Europe, book your flights long in advance of your trip. The earlier you book your tickets, the more money you’ll save. European airlines typically give travelers discounts when they book their tickets early. In addition to getting discounts, it’s also much easier to secure tickets by booking early. Because Europe is such a popular destination, if you leave booking your flights until the last minute, the specific flight you want to take could be sold out and tickets unavailable. Arranging Accommodation You need to arrange accommodation early as well. If you leave your hotel room bookings until the last minute, they could also be sold out. You need to book your hotel rooms when you book your flights. By booking everything at the same time, you can save money and guarantee your trip. Leaving things until the last minute could mean you are unable to stay in the hotel that you want to stay in and be unable to get to the country you plan on traveling to. You can also save money by booking hotel rooms early, though hotel discounts are not as large as the ones offered by airlines. Organizing Transportation Finally, once you arrive, make sure you’ve got a minicab waiting for you. By organizing transportation early, you’ll be able to save yourself a lot of hassle after you get there. Try to learn a little bit of the language of the country you are traveling to so that when you get there, you are able to communicate with taxi drivers and public transport staff. Being able to communicate with locals will make it a lot easier for you to get around. Make sure you have the Google Translate app downloaded as well, just in case you are unable to verbally convey messages. Europe is a great place to travel to, especially if you love history. Make sure that you plan your trip so that nothing goes wrong. You can use the guidance given here to do that. Make sure to consider each point made in this article. Read the full article

0 notes

Text

Condolences, and Then the Everyday Resumes -- UkaROKU english lyrics translation

Song: UkaROKU

VO: RIME

English Translation

I pulled on my uniform that morning, even though I wasn't going to school

And I couldn't seem to bring my parents' faces into focus, both dressed for mourning

The expansive clear sky and pleasant breeze felt disgusting

A voice rang out ahead of me and I got in the car

Faces blur together, both familiar and new

I hope the knot in my heart didn't show in the form of strained greetings

Sitting down in a traditionally styled room, the chair felt cold even through the cloth covering

As the master of ceremonies called us in and slid open the screen

The look on your face was so peaceful, as if you were just sleeping

It almost felt like you would still open your eyes

And flash me the brightest smile

But your icy skin was stiff and ungiving under the burial wash

Every gentle touch on your empty body further broke any illusions I had

Morning the next day, I clothed myself numbly in the will to survive the day

My heart rocked back and forth all the way to the venue

Fit snugly into the coffin you were adorned in flowers, buried in them

And whenever I closed my eyes, reality tracked down my cheeks

The door is closed and the key turns

It's mine to hold onto and I can't do anything but just keep staring at it

The cicadas were crying even though it's not summer yet

As if they were trying to fill the hole in my chest

It's coming time to say goodbye and your coffin is engulfed

Something's overflowing and I can't stop it, or even tell whether it's sweat or tears

Someone bought me a sweet drink from the waiting room and vending machine

I can't taste it, and every time I knock it back more time escapes me

The conclusion of all this spills to the floor and a chill bursts down my spine with vengeance

The master of ceremonies is calling us back

Every last bit of you has been broken to fragments

Pieces passing between chopsticks to fit snugly in a vase

You've become so incredibly small, haven't you

The drops of sweat shed have frozen

You've become light enough that I walk out with you carried in my arms

I've fallen to the point that I can't tell what of this is real and what parts I might be dreaming

A stinging pain radiates from where I burned my hand a bit

And the reality of it all crashes over my head like a bucket of water

The color of the blazing sunset I can see through the car window is so vibrant when compared to that of my heart

I hate it so much

Morning the next day, I sleepily pulled on my uniform

And had to use enough concealer to hide the puffy redness under my eyes

The clear sky stretches endless on the other side of my window

I grab my bag and let them know I'm off for the day, before I open the door

JP original under the cut (kanji/romaji)

学校を休んだだけど朝制服に袖を通した 礼服を纏った両親の顔はぼやけてた 広がる快晴な空と心地の良い風が嫌味だと感じた 前から声がして車のドアを開け歩いた

Gakkou wo yasunda dakedo asa seifuku ni sode wo tooshita Reifuku wo matotta ryoshin no kao wa boyaketeta Hirogaru kaisei na sora to kokochi no yoi kaze ga iyami da to kanjita Mae kara koe ga shite kuruma no doa wo ake aruita

久しぶりの顔ぶれ 初めて見た顔ぶれ 心ん中綯交ぜで軽い会釈は上手くできてたかな 和室で座る椅子布越しでも冷たくて 係の人に呼ばれ襖を開いた

Hisashiburi no kao bure Hajimete mita kao bure Kokoronnaka nai maze de karui eshaku wa umaku dekiteta ka na Washitsu de suwaru isu nunogoshi demo tsumetakute Kakari no hito ni yobare fusuma wo hiraita

その表情は柔くて まるで眠ってるようだった 今にも目を覚まして 笑いかけてくれるような気がしたんだよ 湯灌で触れた肌は固く硬く冷たかった 絵空事は私の前で破られ空っぽのその身を撫でる

Sono kao wa yawakute Marude nemutteru you datta Ima ni mo me wo samashite Warai kakete kureru you na ki ga shitanda yo Yukan de fureta hada wa kataku kataku tsumetakatta Esoragoto wa watashi no mae de yaburare karappo no sono mi wo naderu

明くる日の朝うつろげに征服に袖を通した 会場までずっとゆらゆら心は揺れていた 棺の中に収まったアナタが花に包まれて埋まってく 瞼閉じたら現実が頬を伝ってた

Akuru hi no asa utsuroge ni seifuku ni sode wo tooshita Kaijou made zutto yurayura kokoro wa yureteita Hitsugi no naka ni osamatta anata ga hana ni tsutsumarete umatteku Mabuta tojitara genjitsu ga hoho wo tsutatteta

扉は閉じられてく 鍵はかけられてゆく それが運ばれてゆく私はそれをただただ眺めてる 夏は先なのに蝉の鳴き声がした 心の穴を埋めてくれた気がした

Tobira wa tojirareteku Kagi wa kakerarete yuku Sore ga hakobarete yuku watashi wa sore wo tada tada nagameteru Natsu wa saki na no ni semi no nakigoe ga shita Kokoro no ana wo umete kureta ki ga shita

別れは近づく棺は吸い込まれてく 止められないほど溢れたのは汗か涙かわかんないや 待合室の自販機で買ってもらった甘いジュース 味がしないそれを飲み干してく度に時間は去ってく 零れた結論が床に落ちて爆ぜ頭から爪先まで寒気が走る 係の人が呼んでる

Wakare wa chikadzuku hitsugi wa sui komareteku Tomerarenai hodo afureta no wa ase ka namida ka wakannai ya Machiaishitsu no jihanki de katte moratta amai juusu Aji ga shinai sore wo nomi hoshiteku tabi ni jikan wa satteku Koboreta ketsuron ga yuka ni ochite haze atama kara tsumasaki made samuke ga hashiru Kakari no hito ga yonderu

肌は果てて欠片になって 箸で渡してく壺に収めていく すっかり小さくなってしまったね ポツリとこぼした汗は冷えていた

Hada wa hatete kakera ni natte Hashi de watashiteku tsubo ni osamatte iku Sukkari chiisaku natte shimatta ne Potsuri to koboshita ase wa hieteita

軽くなったアナタを抱え歩く 現実か夢かがあやふやになる感覚に落ちている 少し火傷した手がヒリヒリと痛みだした 現実だって水を差されたような気持ちになる 車の中から見た夕焼け空心と比べて色は鮮やかだった それは憎らしいほどに

Karuku natta anata wo kakae aruku Genjitsu ka yume ka ga ayafuya ni naru kankaku ni ochiteiru Sukoshi yakedo shita te ga hiri hiri to itami dashita Genjitsu datte mizu wo sasareta you na kimochi ni naru Kuruma no naka kara mita yuuyakezora kokoro to kurabete iro wa azayaka datta Sore wa nikurashii hodo ni

明くる日の朝 眠たげに制服に袖を通した 腫れた目の下コンシーラーで隠さなくちゃ 広がる快晴な空が窓の向こうでどこまでも広がってた 鞄を抱えて いってきます とドアを開けた

Akuru hi no asa Nemutage ni seifuku ni sode wo tooshita Hareta me no shita CONCEALER de kakusanakucha Hirogaru kaisei na sora ga mado no mukou de doko made mo hirogatteta Kaban wo kakaete Ittekimasu to doa wo aketa

#aitou soshite nichijou wa tsudzuku#ukaroku#english translation#i have been thinking about this song nonstop since the day it went up#i love it so deeply#i hope everyone else will too

0 notes

Video

youtube

誰も知らない幸徳稲荷神社 春日局の嫁ぎ先の大名屋敷の神から街の神様へ 東京神社 日本

Nobody Knows Koutoku Inari Shrine From God of the Daimyo House where Kasuganotsubone married to God of the City

One of the interesting things about Tokyo shrines is that the god, like a small little shrine, is a It is a former god of a daimyo's mansion, and is connected to a famous person.

This is something you don't see in the countryside.

I used to work at a shrine in the countryside that no one comes to anymore. For me, shrines in Tokyo are like shrines that have been created by the people. I felt that shrines in Tokyo are shrines that have been created by people.

I feel frustrated and yearn for them, and I also feel that "shrines are made by people. I feel that "shrines are made by people".

The shrine that is connected with Kasuga-no-Kakari is likely to bring It is likely to be beneficial.

It feels good to be purified, even if it is small, both in the countryside Tokyo is no different.

0 notes