#Julius Dickens

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Being then in a pleasant frame of mind (from which I infer that poisoning is not always disagreeable in some stages of the process), I resolved to go to the play. It was Covent Garden Theatre that I chose; and there, from the back of a centre box, I saw Julius Caesar and the new Pantomime. To have all those noble Romans alive before me, and walking in and out for my entertainment, instead of being the stern taskmasters they had been at school, was a most novel and delightful effect. But the mingled reality and mystery of the whole show, the influence upon me of the poetry, the lights, the music, the company, the smooth stupendous changes of glittering and brilliant scenery, were so dazzling, and opened up such illimitable regions of delight, that when I came out into the rainy street, at twelve o'clock at night, I felt as if I had come from the clouds, where I had been leading a romantic life for ages, to a bawling, splashing, link-lighted, umbrella-struggling, hackney-coach-jostling, patten-clinking, muddy, miserable world.

David Copperfield by Charles Dickens, "Chapter 19: I Look About Me, and Make a Discovery"

#david copperfield experiences the magic of live theater!#diana rereads david copperfield#i was kicking and screaming when i read this paragraph#god i wish that were me#daisy has a taste for beauty!#this is me inside my deep and wonderful imagination in the year of our lord 2023#i do have to admit i feel like i kinda wanna memorize some of my favorite paragraphs as i reread. i dont know why#i havent PURPOSEFULLY tried to memorize any literature. poetry or prose. since i was a teenager#it was sort of a childish habit of mine. i felt it somehow made me closer to it#not that it doesn't. if thats how it makes you feel.#i guess it also used to be my desire to act/perform. which i dont do at all anymore. shut-in that i am#but ive been so deep in the books and the imagination lately i fancy im practically putting on shows for myself#i live in them now and ill make myself believe them. thats what ill do!#dickens#david copperfield#quotes#victorian literature#shakespeare#julius caesar

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Simeon and the Marylebone Murder

Dear Simeon,Local band, Loud and the Shouties has been accused of making far too much noise in band practice and disturbing the peace. Now, in a shocking turn of events, police have discovered a man – believed to be the lead singer, Hokee Kokee – collapsed outside the venue in Marylebone where the band were due to hold their first gig. Chief Inspector Watt A. Racket suspects foul play. Did one…

View On WordPress

#bond street#certificate#charles dickens#Charles Wesley#estcourt james clack#Garbutt place#John Hughlings Jackson#london#Manchester Square#Murder Mystery#octavia hill#paddington street gardens#patreon#Simeon#Sir julius benedict#st christopher&039;s palce#st christopher&039;s place#St Mary-by-the-tybourne#St marylebone parish church#the adventures of Simeon#theadventuresofsimeon#Treasure Trails#wallace collection#william hogarth

0 notes

Text

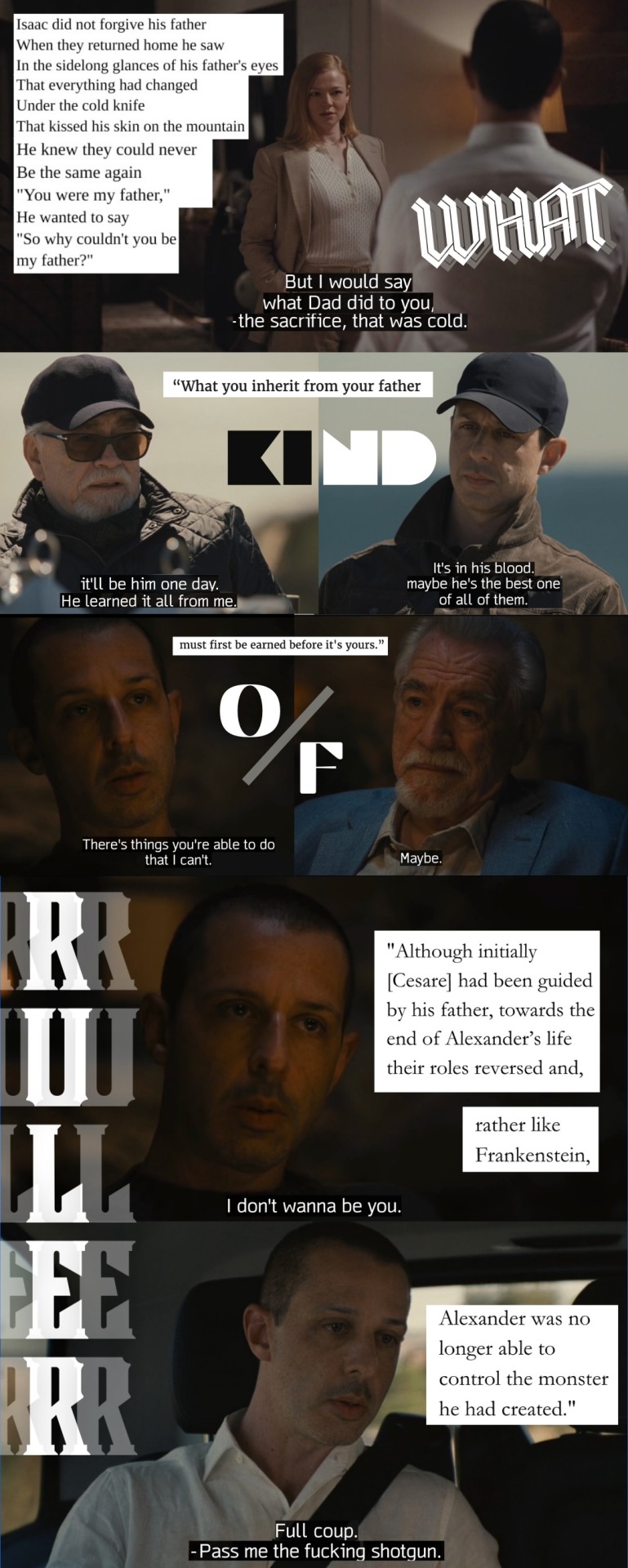

"it is the fate of kings. we never get to see what kind of ruler your son will turn out to be"

inspired by leroichevalier

succession (2018-2023) the prince, niccolo machiavelli ♚ henry iv, william shakespeare // julius caesar, william shakespeare // "and my father's love was nothing next to god's will," amatullah bourdon ♚ faust, johann wolfgang von goethe ♚ the duchess of malfi, barbara banks amendola // great expectations, charles dickens ♚ richard iii, william shakespeare ♚ cesare borgia: la sua vita, la sua famiglia, l suio tempi, gustavo sacerdote ♚ tamburlaine the great, christopher marlowe // the duchess of malfi, barbara banks amendola ♚ 'the godfather' (1972) ♚ the wednesday wars, gary d. schmidt ♚ 1415: henry v's year of glory, ian mortimer ♚ kings (2009)

#succession#succession hbo#Kendall Roy#succession parallels#logan roy#succession s4#parallels#quotes#shakespeare#on kingship#legacy#and fatherhood#words#web weaving#text#succession web weaving#machiavelli and cesare borgia just feels right#and the godfather obviously#season 4 kendall is michael-cesare-prince hal and god am i just stunned by this show

86 notes

·

View notes

Text

Another tag game, this time from @xserpx. Cheers. :D

Rules: List ten books that have stayed with you in some way, don’t take but a few minutes, and don’t think too hard - they don’t have to be the “right” or “great” works, just the ones that have touched you.

1. The Hobbit - J.R.R. Tolkien

2. A Kist o’ Whistles - Moira Miller

3. The Lantern Bearers - Rosemary Sutcliff

4. The Agricola - Tacitus

5. The Chronicles of Prydain - Lloyd Alexander (cheating a bit - that’s five books in one :P)

6. Great Expectations - Charles Dickens

7. Vinland - George Mackay Brown

8. Julius Caesar - William Shakespeare

9. Kidnapped - Robert Louis Stevenson

10. Horrible Histories series - Terry Deary. No joke, I think most of my personality has been shaped by HH in its various forms over the years. XD

Not sure how many people I’m meant to tag in turn, so I’ll go with ten (with no obligation, naturally): @attheexactlyrighttimeandplace, @bryndeavour, @themalhambird, @chiropteracupola, @pythionice, @cycas, @ltwilliammowett, @vicivefallen, @cilil, @irisseireth.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

I have recently become interested in learning about some of the lesser know asteroids and Sappho is what I'm currently invested in and have found a fascinating thought I would like to introduce about Sappho and it's influence based on the events at the time of it's discovery. Sappho was a real person that lived c.600BC. She is attributed with being a feminist having many talents, especially the arts. Sappho the asteroid was discovered in 1864.

During the late 19th century the disease tuberculosis was ravaging the world with it's highly infectious bacterial spread. During the late 1800's a cultural depiction known as "tuberculosis chic" began to populate the art world and popular culture. The artistic depiction was a romantization of the dramatic wasting away that took place as the disease slowly extinguished it's host. As you can see with the painting above the subject is young, we can see the release in her facial expression and the objects in the background alluding to time and in a surreal setting that is soft and dream-like. Many artistic portrayals of women during this time were of tranquility and release as dying subjects that became even more beautiful and elegant in death. I also want to point out that around this period the east coast was ravaged by a terrible fear of vampirism as a lack of understanding of the disease led to folks being convinced that consumption was coming from the deceased that rose again to suck the life out of the living and therefore exumed bodies to remove their limbs therefore removing their ability to walk or take hold of something should they try and rise. Vampirism in itself has so many allegoric associations with tuberculosis I feel like it's pretty much common knowledge that the two are highly linked.

Anywho, literature was a popular form of the time and I believe Charles Dickens and Charlotte Brönte added the affliction to characters in the books of time or at least made reference to it.

Art imitates life, right? Or is it life imitates art? If you want to be enlightened to the heart of a subject look at an artistic portrayal of it. I noticed that the glyph of Sappho looks like a mirror with a line down the middle like it's dividing the mirror into two sides. A symbol of duality? Reflection within reflection?

Did you know that John Wilx Booth played Marc Antony in Shakespeare's Julius Cesar alongside his brother in 1864? John would go on to assassinate Abraham Lincoln the following year... in a theater... something about the theater!! It's almost like he had some weird fantasy about a dramatic finale don't you think?

A major turning point in the Civil War took place in 1864 when General Grant was tasked with leading the Union in the next phase of the war that would also end the following year.

So these are just some of the things that I've found that stand out to me as relevant in some capacity.

📷: culturedmag

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

William Shakespeare, Shakespeare also spelled Shakspere, byname Bard of Avon or Swan of Avon, (baptized April 26, 1564, Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire, England—died April 23, 1616, Stratford-upon-Avon), English poet, dramatist, and actor often called the English national poet and considered by many to be the greatest dramatist of all time.

Shakespeare occupies a position unique in world literature. Other poets, such as Homer and Dante, and novelists, such as Leo Tolstoy and Charles Dickens, have transcended national barriers, but no writer’s living reputation can compare to that of Shakespeare, whose plays, written in the late 16th and early 17th centuries for a small repertory theatre, are now performed and read more often and in more countries than ever before. The prophecy of his great contemporary, the poet and dramatist Ben Jonson, that Shakespeare “was not of an age, but for all time,” has been fulfilled.

William Shakespeare

Category: Arts & Culture

Baptized: April 26, 1564 Stratford-upon-Avon England

Died: April 23, 1616 Stratford-upon-Avon England

Notable Works: “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” “All’s Well That Ends Well” “Antony and Cleopatra” “As You Like It” “Coriolanus” “Cymbeline” First Folio “Hamlet” “Henry IV, Part 1” “Henry IV, Part 2” “Henry V” “Henry VI, Part 1” “Henry VI, Part 2” “Henry VI, Part 3” “Henry VIII” “Julius Caesar” “King John” “King Lear” “Love’s Labour’s Lost” “Macbeth” “Measure for Measure” “Much Ado About Nothing” “Othello” “Pericles” “Richard III” “The Comedy of Errors” “The Merchant of Venice” “The Merry Wives of Windsor” “The Taming of the Shrew” “The Tempest” “Timon of Athens”

Movement / Style: Jacobean age

Notable Family Members: spouse Anne Hathaway

It may be audacious even to attempt a definition of his greatness, but it is not so difficult to describe the gifts that enabled him to create imaginative visions of pathos and mirth that, whether read or witnessed in the theatre, fill the mind and linger there. He is a writer of great intellectual rapidity, perceptiveness, and poetic power. Other writers have had these qualities, but with Shakespeare the keenness of mind was applied not to abstruse or remote subjects but to human beings and their complete range of emotions and conflicts. Other writers have applied their keenness of mind in this way, but Shakespeare is astonishingly clever with words and images, so that his mental energy, when applied to intelligible human situations, finds full and memorable expression, convincing and imaginatively stimulating. As if this were not enough, the art form into which his creative energies went was not remote and bookish but involved the vivid stage impersonation of human beings, commanding sympathy and inviting vicarious participation. Thus, Shakespeare’s merits can survive translation into other languages and into cultures remote from that of Elizabethan England.

Shakespeare the man

Life

Although the amount of factual knowledge available about Shakespeare is surprisingly large for one of his station in life, many find it a little disappointing, for it is mostly gleaned from documents of an official character. Dates of baptisms, marriages, deaths, and burials; wills, conveyances, legal processes, and payments by the court—these are the dusty details. There are, however, many contemporary allusions to him as a writer, and these add a reasonable amount of flesh and blood to the biographical skeleton.

Shakespeare Reading, oil on canvas by William Page, 1873-74; in the collection of the Smithsonian American Museum of Art, Washington, D.C. (William Shakespeare)

Shakespeare's birthplace

The parish register of Holy Trinity Church in Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire, shows that he was baptized there on April 26, 1564; his birthday is traditionally celebrated on April 23. His father, John Shakespeare, was a burgess of the borough, who in 1565 was chosen an alderman and in 1568 bailiff (the position corresponding to mayor, before the grant of a further charter to Stratford in 1664). He was engaged in various kinds of trade and appears to have suffered some fluctuations in prosperity. His wife, Mary Arden, of Wilmcote, Warwickshire, came from an ancient family and was the heiress to some land. (Given the somewhat rigid social distinctions of the 16th century, this marriage must have been a step up the social scale for John Shakespeare.)

Stratford enjoyed a grammar school of good quality, and the education there was free, the schoolmaster’s salary being paid by the borough. No lists of the pupils who were at the school in the 16th century have survived, but it would be absurd to suppose the bailiff of the town did not send his son there. The boy’s education would consist mostly of Latin studies—learning to read, write, and speak the language fairly well and studying some of the Classical historians, moralists, and poets. Shakespeare did not go on to the university, and indeed it is unlikely that the scholarly round of logic, rhetoric, and other studies then followed there would have interested him.

Instead, at age 18 he married. Where and exactly when are not known, but the episcopal registry at Worcester preserves a bond dated November 28, 1582, and executed by two yeomen of Stratford, named Sandells and Richardson, as a security to the bishop for the issue of a license for the marriage of William Shakespeare and “Anne Hathaway of Stratford,” upon the consent of her friends and upon once asking of the banns. (Anne died in 1623, seven years after Shakespeare. There is good evidence to associate her with a family of Hathaways who inhabited a beautiful farmhouse, now much visited, 2 miles [3.2 km] from Stratford.) The next date of interest is found in the records of the Stratford church, where a daughter, named Susanna, born to William Shakespeare, was baptized on May 26, 1583. On February 2, 1585, twins were baptized, Hamnet and Judith. (Hamnet, Shakespeare’s only son, died 11 years later.)

How Shakespeare spent the next eight years or so, until his name begins to appear in London theatre records, is not known. There are stories—given currency long after his death—of stealing deer and getting into trouble with a local magnate, Sir Thomas Lucy of Charlecote, near Stratford; of earning his living as a schoolmaster in the country; of going to London and gaining entry to the world of theatre by minding the horses of theatregoers. It has also been conjectured that Shakespeare spent some time as a member of a great household and that he was a soldier, perhaps in the Low Countries. In lieu of external evidence, such extrapolations about Shakespeare’s life have often been made from the internal “evidence” of his writings. But this method is unsatisfactory: one cannot conclude, for example, from his allusions to the law that Shakespeare was a lawyer, for he was clearly a writer who without difficulty could get whatever knowledge he needed for the composition of his plays.

Career in the theatre of William Shakespeare

The first reference to Shakespeare in the literary world of London comes in 1592, when a fellow dramatist, Robert Greene, declared in a pamphlet written on his deathbed:

There is an upstart crow, beautified with our feathers, that with his Tygers heart wrapt in a Players hide supposes he is as well able to bombast out a blank verse as the best of you; and, being an absolute Johannes Factotum, is in his own conceit the only Shake-scene in a country.

What these words mean is difficult to determine, but clearly they are insulting, and clearly Shakespeare is the object of the sarcasms. When the book in which they appear (Greenes, groats-worth of witte, bought with a million of Repentance, 1592) was published after Greene’s death, a mutual acquaintance wrote a preface offering an apology to Shakespeare and testifying to his worth. This preface also indicates that Shakespeare was by then making important friends. For, although the puritanical city of London was generally hostile to the theatre, many of the nobility were good patrons of the drama and friends of the actors. Shakespeare seems to have attracted the attention of the young Henry Wriothesley, the 3rd earl of Southampton, and to this nobleman were dedicated his first published poems, Venus and Adonis and The Rape of Lucrece.

One striking piece of evidence that Shakespeare began to prosper early and tried to retrieve the family’s fortunes and establish its gentility is the fact that a coat of arms was granted to John Shakespeare in 1596. Rough drafts of this grant have been preserved in the College of Arms, London, though the final document, which must have been handed to the Shakespeares, has not survived. Almost certainly William himself took the initiative and paid the fees. The coat of arms appears on Shakespeare’s monument (constructed before 1623) in the Stratford church. Equally interesting as evidence of Shakespeare’s worldly success was his purchase in 1597 of New Place, a large house in Stratford, which he as a boy must have passed every day in walking to school.

Globe Theatre

How his career in the theatre began is unclear, but from roughly 1594 onward he was an important member of the Lord Chamberlain’s company of players (called the King’s Men after the accession of James I in 1603). They had the best actor, Richard Burbage; they had the best theatre, the Globe (finished by the autumn of 1599); they had the best dramatist, Shakespeare. It is no wonder that the company prospered. Shakespeare became a full-time professional man of his own theatre, sharing in a cooperative enterprise and intimately concerned with the financial success of the plays he wrote.

Unfortunately, written records give little indication of the way in which Shakespeare’s professional life molded his marvelous artistry. All that can be deduced is that for 20 years Shakespeare devoted himself assiduously to his art, writing more than a million words of poetic drama of the highest quality.

Private life

Shakespeare's house in Stratford-upon-Avon

Shakespeare had little contact with officialdom, apart from walking—dressed in the royal livery as a member of the King’s Men—at the coronation of King James I in 1604. He continued to look after his financial interests. He bought properties in London and in Stratford. In 1605 he purchased a share (about one-fifth) of the Stratford tithes—a fact that explains why he was eventually buried in the chancel of its parish church. For some time he lodged with a French Huguenot family called Mountjoy, who lived near St. Olave’s Church in Cripplegate, London. The records of a lawsuit in May 1612, resulting from a Mountjoy family quarrel, show Shakespeare as giving evidence in a genial way (though unable to remember certain important facts that would have decided the case) and as interesting himself generally in the family’s affairs.

No letters written by Shakespeare have survived, but a private letter to him happened to get caught up with some official transactions of the town of Stratford and so has been preserved in the borough archives. It was written by one Richard Quiney and addressed by him from the Bell Inn in Carter Lane, London, whither he had gone from Stratford on business. On one side of the paper is inscribed: “To my loving good friend and countryman, Mr. Wm. Shakespeare, deliver these.” Apparently Quiney thought his fellow Stratfordian a person to whom he could apply for the loan of £30—a large sum in Elizabethan times. Nothing further is known about the transaction, but, because so few opportunities of seeing into Shakespeare’s private life present themselves, this begging letter becomes a touching document. It is of some interest, moreover, that 18 years later Quiney’s son Thomas became the husband of Judith, Shakespeare’s second daughter.

Shakespeare’s will (made on March 25, 1616) is a long and detailed document. It entailed his quite ample property on the male heirs of his elder daughter, Susanna. (Both his daughters were then married, one to the aforementioned Thomas Quiney and the other to John Hall, a respected physician of Stratford.) As an afterthought, he bequeathed his “second-best bed” to his wife; no one can be certain what this notorious legacy means. The testator’s signatures to the will are apparently in a shaky hand. Perhaps Shakespeare was already ill. He died on April 23, 1616. No name was inscribed on his gravestone in the chancel of the parish church of Stratford-upon-Avon. Instead these lines, possibly his own, appeared:

Sexuality of William Shakespeare

Like so many circumstances of Shakespeare’s personal life, the question of his sexual nature is shrouded in uncertainty. At age 18, in 1582, he married Anne Hathaway, a woman who was eight years older than he. Their first child, Susanna, was born on May 26, 1583, about six months after the marriage ceremony. A license had been issued for the marriage on November 27, 1582, with only one reading (instead of the usual three) of the banns, or announcement of the intent to marry in order to give any party the opportunity to raise any potential legal objections. This procedure and the swift arrival of the couple’s first child suggest that the pregnancy was unplanned, as it was certainly premarital. The marriage thus appears to have been a “shotgun” wedding. Anne gave birth some 21 months after the arrival of Susanna to twins, named Hamnet and Judith, who were christened on February 2, 1585. Thereafter William and Anne had no more children. They remained married until his death in 1616.

Were they compatible, or did William prefer to live apart from Anne for most of this time? When he moved to London at some point between 1585 and 1592, he did not take his family with him. Divorce was nearly impossible in this era. Were there medical or other reasons for the absence of any more children? Was he present in Stratford when Hamnet, his only son, died in 1596 at age 11? He bought a fine house for his family in Stratford and acquired real estate in the vicinity. He was eventually buried in Holy Trinity Church in Stratford, where Anne joined him in 1623. He seems to have retired to Stratford from London about 1612. He had lived apart from his wife and children, except presumably for occasional visits in the course of a very busy professional life, for at least two decades. His bequeathing in his last will and testament of his “second best bed” to Anne, with no further mention of her name in that document, has suggested to many scholars that the marriage was a disappointment necessitated by an unplanned pregnancy.

What was Shakespeare’s love life like during those decades in London, apart from his family? Knowledge on this subject is uncertain at best. According to an entry dated March 13, 1602, in the commonplace book of a law student named John Manningham, Shakespeare had a brief affair after he happened to overhear a female citizen at a performance of Richard III making an assignation with Richard Burbage, the leading actor of the acting company to which Shakespeare also belonged. Taking advantage of having overheard their conversation, Shakespeare allegedly hastened to the place where the assignation had been arranged, was “entertained” by the woman, and was “at his game” when Burbage showed up. When a message was brought that “Richard the Third” had arrived, Shakespeare is supposed to have “caused return to be made that William the Conqueror was before Richard the Third. Shakespeare’s name William.” This diary entry of Manningham’s must be regarded with much skepticism, since it is verified by no other evidence and since it may simply speak to the timeless truth that actors are regarded as free spirits and bohemians. Indeed, the story was so amusing that it was retold, embellished, and printed in Thomas Likes’s A General View of the Stage (1759) well before Manningham’s diary was discovered. It does at least suggest, at any rate, that Manningham imagined it to be true that Shakespeare was heterosexual and not averse to an occasional infidelity to his marriage vows. The film Shakespeare in Love (1998) plays amusedly with this idea in its purely fictional presentation of Shakespeare’s torchy affair with a young woman named Viola De Lesseps, who was eager to become a player in a professional acting company and who inspired Shakespeare in his writing of Romeo and Juliet—indeed, giving him some of his best lines.

Apart from these intriguing circumstances, little evidence survives other than the poems and plays that Shakespeare wrote. Can anything be learned from them? The sonnets, written perhaps over an extended period from the early 1590s into the 1600s, chronicle a deeply loving relationship between the speaker of the sonnets and a well-born young man. At times the poet-speaker is greatly sustained and comforted by a love that seems reciprocal. More often, the relationship is one that is troubled by painful absences, by jealousies, by the poet’s perception that other writers are winning the young man’s affection, and finally by the deep unhappiness of an outright desertion in which the young man takes away from the poet-speaker the dark-haired beauty whose sexual favours the poet-speaker has enjoyed (though not without some revulsion at his own unbridled lust, as in Sonnet 129). This narrative would seem to posit heterosexual desire in the poet-speaker, even if of a troubled and guilty sort; but do the earlier sonnets suggest also a desire for the young man? The relationship is portrayed as indeed deeply emotional and dependent; the poet-speaker cannot live without his friend and that friend’s returning the love that the poet-speaker so ardently feels. Yet readers today cannot easily tell whether that love is aimed at physical completion. Indeed, Sonnet 20 seems to deny that possibility by insisting that Nature’s having equipped the friend with “one thing to my purpose nothing”—that is, a penis—means that physical sex must be regarded as solely in the province of the friend’s relationship with women: “But since she [Nature] pricked thee out for women’s pleasure, / Mine be thy love and thy love’s use their treasure.” The bawdy pun on “pricked” underscores the sexual meaning of the sonnet’s concluding couplet. Critic Joseph Pequigney has argued at length that the sonnets nonetheless do commemorate a consummated physical relationship between the poet-speaker and the friend, but most commentators have backed away from such a bold assertion.

A significant difficulty is that one cannot be sure that the sonnets are autobiographical. Shakespeare is such a masterful dramatist that one can easily imagine him creating such an intriguing story line as the basis for his sonnet sequence. Then, too, are the sonnets printed in the order that Shakespeare would have intended? He seems not to have been involved in their publication in 1609, long after most of them had been written. Even so, one can perhaps ask why such a story would have appealed to Shakespeare. Is there a level at which fantasy and dreamwork may be involved?

The plays and other poems lend themselves uncertainly to such speculation. Loving relationships between two men are sometimes portrayed as extraordinarily deep. Antonio in Twelfth Night protests to Sebastian that he needs to accompany Sebastian on his adventures even at great personal risk: “If you will not murder me for my love, let me be your servant” (Act II, scene 1, lines 33–34). That is to say, I will die if you leave me behind. Another Antonio, in The Merchant of Venice, risks his life for his loving friend Bassanio. Actors in today’s theatre regularly portray these relationships as homosexual, and indeed actors are often incredulous toward anyone who doubts that to be the case. In Troilus and Cressida, Patroclus is rumoured to be Achilles’ “masculine whore” (V, 1, line 17), as is suggested in Homer, and certainly the two are very close in friendship, though Patroclus does admonish Achilles to engage in battle by saying,

Again, on the modern stage this relationship is often portrayed as obviously, even flagrantly, sexual; but whether Shakespeare saw it as such, or the play valorizes homosexuality or bisexuality, is another matter.

A woman impudent and mannish grown

Certainly his plays contain many warmly positive depictions of heterosexuality, in the loves of Romeo and Juliet, Orlando and Rosalind, and Henry V and Katharine of France, among many others. At the same time, Shakespeare is astute in his representations of sexual ambiguity. Viola—in disguise as a young man, Cesario, in Twelfth Night—wins the love of Duke Orsino in such a delicate way that what appears to be the love between two men morphs into the heterosexual mating of Orsino and Viola. The ambiguity is reinforced by the audience’s knowledge that in Shakespeare’s theatre Viola/Cesario was portrayed by a boy actor of perhaps 16. All the cross-dressing situations in the comedies, involving Portia in The Merchant of Venice, Rosalind/Ganymede in As You Like It, Imogen in Cymbeline, and many others, playfully explore the uncertain boundaries between the genders. Rosalind’s male disguise name in As You Like It, Ganymede, is that of the cupbearer to Zeus with whom the god was enamoured; the ancient legends assume that Ganymede was Zeus’s catamite. Shakespeare is characteristically delicate on that score, but he does seem to delight in the frisson of sexual suggestion.

#entrepreneur#poems on tumblr#poetry#spilled thoughts#william shakespeare#shakespeare#bookish#books#literature

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tomato Nation’s Book Smarts

Here is what Sarah D. Bunting recommends reading and knowing in this piece, “Book Smarts” from tomatonation.com (up until where she writes “After you surface from “Wasteland,” you can pretty much read whatever you like.”): https://tomatonation.com/culture-and-criticism/book-smarts/

Quotes are from that piece.

I have bolded the parts I have finished doing. I added my own commentary in brackets.

“You need to know the major stories of the Old Testament: The Fall, Cain and Abel, Noah and the ark, the diaspora, all that good stuff.”

“You also need to know the story of Christ’s birth and the story of his death.”

”Skim the psalms and the Song of Solomon if you have a minute”

“[T]hen read Revelations.”

“Understand what “Shinto” means.”

“Read a little Confucius.”

“Know a few facts about Muhammad’s life.”

“Know what Martin Luther did.”

“Buy a secondhand copy of Edith Hamilton’s book of myths — or, if you have more time, Ovid’s Metamorphoses — and bone up on the Greco-Roman pantheon.”

“Learn the major figures in Nordic/Viking mythology.”

“Don’t know the dates of the American Civil War, where the battles took place, why it started? Learn it”.

“Don’t know how long the Depression lasted, how many Americans died in the Great War, when the influenza epidemic took place? Learn it”.

“[R]ead The Odyssey or the first four books of The Aeneid…You don’t have to slog through every page of these, but at least buy the Cliff’s Notes to The Odyssey.”

“Hit the highlights of Catullus’s poems to Lesbia and Horace’s “Odes.””

“Find the existing scraps of Sappho and read those (it’ll take you five minutes, tops).”

“Know what Petronius and Apuleius wrote, but don’t bother reading them.” [Petronius wrote the satirical novel The Satyricon, and Apuleius wrote the novel The Golden Ass.]

“You should also read the greatest hits of Plato and Socrates.”

“Then make sure you know what really happens in the Oedipus cycle.”

“Know what Thucycdides and Aristophanes wrote, or at least the genre.” [The genre is history for Thucycdides and comedy or Old Comedy, the first phase of ancient Greek comedy, for Aristophanes.]

“You need to know what happens in “Beowulf.”” “You need to know what happens in “Canterbury Tales” and why it’s important as literature. The excerpts they give you in the Norton cover the subject quite nicely; there’s no need to kill yourself reading the whole thing.”

“Learn the Arthurian legend, and the Tristan/Isolde legend.”

“Read St. Augustine. It’s…a key tract on the philosophy of faith. Get as far as you can without your heart stopping.” [I emailed Sarah to ask which book she meant here and she said "I assume I was being snotty about ;) the Confessions, which is what I would have had to read for lit survey; hope that helps!"]

“You need a firm grounding in Shakespeare. I think three out of the big four — Lear, Hamlet, Othello, and Macbeth — should do you, but know what happens in all of them.”

“You should also know Twelfth Night, Romeo and Juliet, Julius Caesar, The Taming Of The Shrew, The Tempest, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and the Henry cycle, but four out of those seven will cover it; again, know which characters go where and why they’re important. Knowing that someone said “et tu, Brute” doesn’t cut it. Renting the movies is fine.”

“You also have to have read Paradise Lost…Okay, just read up until Satan’s fall.”

“Know what John Donne and Ben Jonson and Marvell did.”

“You need Wordsworth, Shelley, and Keats.”

“You need one Austen.” [I picked Pride and Prejudice.]

“You need one Dickens.” [I picked Oliver Twist.]

“You need one Twain.” [I picked The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.]

“You need as much of Whitman’s Leaves Of Grass as you can stomach”

“[P]lus When Lilacs Last By The Dooryard Bloom’d.”

“You need some Hawthorne (if you can’t bear the thought of Hester Prynne, try his short stories instead).”

“You need a smattering of Dickinson.”

“Move on to Eliot, Pound, Yeats, and Frost.”

“Try Joyce. Don’t do Ulysses alone; start a book group and get The Bloomsday Book. Dubliners is nicer.”

“After you surface from “Wasteland,” you can pretty much read whatever you like.”

0 notes

Text

Some books and plays I have read that are older than me oand/or were written before I was born:

Plays:

• Much Ado About Nothing by William Shakespeare

• The Tempest by William Shakespeare

• Romeo and Juliet by William Shakespeare

• Hamlet by William Shakespeare

• Julius Ceasar by William Shakespeare

• A Midsummer Night's Dream

• Oedipus Rex by Sophocles

• Our Town by Thornton Wilder

Fairy Tales and Fables:

• The Little Mermaid by Hans Christian Andersen

• The Little Match Girl by Hans Christian Andersen

• The Snow Queen by Hans Christian Andersen

• The Ugly Duckling by Hans Christian Andersen

• The Emperor's New Clothes by Hans Christian Andersen

• The Nightingale by Hans Christian Andersen

• The Princess and the Pea by Hans Christian Andersen

• The Most Incredible Thing by Hans Christian Andersen

• The Frogs and the Ox;Belling the Cat;The Town Mouse and the Country Mouse;The Fox and the Grapes;The Wolf and the Crane;The Lion and the Mouse;The Crow and the Pitcher; The Fox and the Stork;The Fox and the Leopard;The Wolf in Sheep's Clothing;The Wolf, the Kid, and the Goat;The Lion's Share;The Wolves and the Sheep;The Ass in the Lion's Skin;The Farmer and the Snake; They Dog and the Oyster;The Wolf and the House Dog;Three Bullocks and a Lion; The Vain Jackdaw and His Borrowed Feathers;The Dogs and the Fox;The Farmer and the Cranes; and The Goose and the Golden Egg... by Aesop

• The Frog King; Cat and Mouse Partnership; The Story if the Youth Who Went Forth To Learn What Fear Was; The Wolf and the Seven Little Kids; Faithful John; Little Brother and Little Sister; Rapunzel; The Three Little Mean in the Wood; Hansel and Gretel; The Three Snake-Leaves; The White Snake; The Fisherman and His Wife; The Valiant Little Tailor; Cinderella; The Riddle; The Mouse, The Bird, and the Sausage; Mother Holle; The Seven Ravens; Little Red Cap; The Singing Bone; Clever Hans; The Wedding of Mrs. Fox; The Robber Bridergroom; Godfather Death; The Juniper Tree; The Six Swans; Briar Rose (Sleeping Beauty); Little Snow White; Rumpelstiltskin; The Golden Bird; The Dog and the Sparrow; Frederick and Catherine; The Two Brothers; The Queen Bee; The Three Feathers; The Golden Goose; The Twelve Hunters; The Three Sons of Fortune; The Wiof and the Fox; The Fox and His Cousin; The Water Nixie; Brother Lustig; The Fox and the Geese; The Poor Man and the Rich Man; The Raven; The Peasant's Wise Daughter; Stories about Snakes; Hans the Hedgehog; The Three Brothers; Ferdinand the Faithful; One-eye, Two-eyes, and Three-eyes; The Shoes that Were Danced To Pieces; Iron John; The Lambkin and the Fish; The Lord's Animals and the Devil's; The Old Beggar Woman; Odds and Ends; The Sparrow and His Four Children; Snow White and Rose Red; The Wise Servant; The Glass Coffin; The Griffin; The Peasant in Heaven; The Bittern and Hoopoe; The Owl; Death's Messengers; The Spindle, the Shuttle, and the Needle; The Drummer; The Ear of Corn; Old Rinkrank... written/retold by the Brothers' Grimm

The 1800s- late 1930s set books:

• Big Red by Jim Kjelgaard

• The Yearling by Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings

• The Sign of the Beaver by Elizabeth George Speare

• Black Beauty by Anna Sewell

• White Fang by Jack London

• Call of the Wild by Jack London

• A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens

• Little House in the Big Woods by Laura Ingalls Wilder

• Farmer Boy by Laura Ingalls Wilder

• Little House on the Prairie by Laura Ingalls Wilder

• On the Banks of Plum Creek by Laura Ingalls Wilder

• By the Shores of Silver Lake by Laura Ingalls Wilder

• The Long Winter by Laura Ingalls Wilder

• Little Town on the Prairie by Laura Ingalls Wilder

• Anne of Green Gables by Lucy Maud Montgomery

• Anne of Avonlea by Lucy Maud Montgomery

• Anne of the Island by Lucy Maud Montgomery

Edgar Allan Poe Works I've Read:

• The Raven; a poem

• Annabel Lee; a poem

• Lenore; a poem

• To Helen; a poem

• The Black Cat; a short story

• The Cask of Amontillado; a short story

• Ligeia; a short story

• The Masque of the Red Death; a short story

• Morella; a short story

• The Pit and the Pendulum; a short story

• The Premature Burial; a short story

• The System of Doctor Tarr and Professor Fether; a short story

• The Tell-Tale Heart; a short story

Oldie But Goldies; Everything Else Thst is Older Than Me That I've Read:

• Winnie-the-Pooh by A. A. Milne

• Alice in Wonderland and Alice Through the Looking Glass by Lewis Carroll

• The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe; Prince Caspian; The Voyage of the Dawn Treader; The Silver Chair; The Horse and His Boy; and The Magician's Nephew by C. S. Lewis

• Charlotte's Web by E. B. White

• The Hobbit by J. R. R. Tolkien

• The Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame

• Redwall by Brian Jacques

• Frog and Toad by Arnold Lobel

• The Phantom Tollbooth by Norton Juster

• The Giver by Lois Lowry

• The Velveteen Rabbit by Margery Williams

• The Tale of Despereaux by Kate DiCamillo

• Mr. Popper's Penguins by Richard and Florence Atwater

There is a lot I've probably read but don't remember, but these are the literatures I can remember that are older than me, or were made before I was born, that I have read😊

0 notes

Quote

The origin of my French Revvie obsession was probably the inclusion of Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities on the high school curriculum, circa 1953. Why it? For the same reason we got Julius Caesar early on, I expect: no sex in it. Just a lot of bloodshed. (Sexual assault takes place in the Dickens but off the page, and the woman dies as a result, so message delivered to high school juniors: a) Aristocrats are bad! and b) Sex will kill you. Things a young girl should know.)

The French Revvie, Part 1: The Movies - by Margaret Atwood

0 notes

Text

That’s a good list! I would suggest:

-1984 -Anna Karenina -Catch-22 -The Great Gatsby -The Old Man and the Sea -Alexandre Dumas is great; my favorite is The Count of Monte Cristo -I read a few Kurt Vonnegut books and loved them all; I think my favorite was Cat’s Cradle -is John Gardner’s Grendel old enough to be considered a classic? That one blew my mind in high school -for Shakespeare, I prefer Macbeth and Julius Caesar to Hamlet -I hate Charles Dickens with a passion but A Tale of Two Cities was good

Hey so like many of you, I saw that article about how people are going into college having read no classic books. And believe it or not, I've been pissed about this for years. Like the article revealed, a good chunk of American Schools don't require students to actually read books, rather they just give them an excerpt and tell them how to feel about it. Which is bullshit.

So like. As a positivity post, let's use this time to recommend actually good classic books that you've actually enjoyed reading! I know that Dracula Daily and Epic the Musical have wonderfully tricked y'all into reading Dracula and The Odyssey, and I've seen a resurgence of Picture of Dorian Gray readership out of spite for N-tflix, so let's keep the ball rolling!

My absolute favorite books of all time are The Haunting of Hill House and We Have Always Lived in the Castle by Shirley Jackson. Classic psychological horror books about unhinged women.

I adore The Bad Seed by William March. It's widely considered to be the first "creepy child" book in American literature, so reading it now you're like "wow that's kinda cliche- oh my god this is what started it. This was ground zero."

I remember the feelings of validation I got when people realized Dracula wasn't actually a love story. For further feelings of validation, please read Frankenstein by Mary Shelley and The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson. There's a lot the more popular adaptations missed out on.

Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier is an absolute gem of a book. It's a slow-build psychological study so it may not be for everyone, but damn do the plot twists hit. It's a really good book to go into blind, but I will say that its handling of abuse victims is actually insanely good for the time period it was written in.

Moving on from horror, you know people who say "I loved this book so much I couldn't put it down"? That was me as a kid reading A Little Princess by Frances Hodgson Burnett. Picked it up while bored at the library and was glued to it until I finished it.

Peter Pan and Wendy by JM Barrie was also a childhood favorite of mine. Next time someone bitches about Woke Casting, tell them that the original 1911 Peter Pan novel had canon nonbinary fairies.

Watership Down by Richard Adams is my sister Cori's favorite book period. If you were a Warrior Cats, Guardians of Ga'Hoole or Wings of Fire kid, you owe a metric fuckton to Watership Down and its "little animals on a big adventure" setup.

A Raisin in the Sun by Lorraine Hansberry was a play and not a book first, but damn if it isn't a good fucking read. It was also named after a Langston Hughes poem, who's also an absolutely incredible author.

Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury is a book I absolutely adore and will defend until the day I die. It's so friggin good, y'all, I love it more than anything. You like people breaking out of fascist brainwashing? You like reading and value knowledge? You wanna see a guy basically predict the future of television back in 1953? Read Fahrenheit.

Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain and To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee are considered required reading for a reason: they're both really good books about young white children unlearning the racial biases of their time. Huck Finn specifically has the main character being told that he will go to hell if he frees a slave, and deciding eternal damnation would be worth it.

As a sidenote, another Mark Twain book I was obsessed with as a kid was A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court. Exactly what it says on the tin, incredibly insane read.

If Beale Street Could Talk by James Baldwin is a heartbreaking but powerful book and a look at the racism of the time while still centering the love the two black protagonists feel for each other. Giovanni's Room by the same author is one that focuses on a MLM man struggling with his sexuality, and it's really important to see from the perspective of a queer man living in the 50s– as well as Baldwin's autobiographical novel, Go Tell it on the Mountain.

Agatha Christie mysteries are all still absolutely iconic, but Murder on the Orient Express is such a good read whether or not you know the end twist.

Maybe-controversial-maybe-not take: Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov is a good book if you have reading comprehension. No, you're not supposed to like the main character. He pretty much spells that out for you at the end ffs.

Animal Farm by George Orwell was another favorite of mine; it was written as an obvious metaphor for the rise of fascism in Russia at the time and boy does it hit even now.

And finally, please read Shakespeare plays. As soon as you get used to their way of talking, they're not as hard to understand as people will lead you to believe. My absolute favorite is Twelfth Night- crossdressing, bisexual love triangles, yellow stockings... it's all a joy.

and those are just the ones i thought of off the top of my head! What're your guys' favorite classic books? Let's make everyone a reading list!

#I read a handful of these on project gutenberg in grad school#instead of the research I was supposed to be doing#also Amazon has (or used to have) a bunch of free classics e-books#I got a kindle and downloaded a bunch of them to read in the bus

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Books I've read so far in 2023

Making a lil continuing list to keep track of the books I've been reading this year!

'Makers of Rome: Nine Lives' by Plutarch

'The Age of Alexander: Nine Greek Lives' by Plutarch

'Rubicon: The Triumph and Tragedy of the Roman Republic' by Tom Holland

'Julius Caesar: Life of a Colossus' by Adrian Goldsworthy

'Normal People' by Sally Rooney

'For the Unity of the Working Class against Fascism' by Georgi Dimitrov

'Fundamental Problems of Marxism by Georgi Plekhanov [Re-read]

'Trade Unions' by Geoffrey Drage

'The Essential Trotsky' [Re-read]

'The Essential Rosa Luxemburg'

'The Last of the Mohicans' by Jame Fenimore Cooper

'We only want the Earth: Anticapitalism Against the Climate Crisis' by Gus Woody

'Marxism and Transgender Liberation: Confronting Transphobia in the British Left' by Red Fightback

'Fall of the Roman Republic: Six Lives' by Plutarch

'The Nehrus and the Gandhis: An Indian Dynasty' by Tariq Ali

'Winston Churchill: His times, his crimes' by Tariq Ali

'Augustus: From Revolutionary to Emperor' by Adrian Goldsworthy

'The Twelve Caesars' by Suetonius

'In the Shadow of Vesuvius: A Life of Pliny' by Daisy Dunn

'Islamic Empires: Fifteen Cities that Define a Civilization' by Justin Marozzi

'When the Bulbul stopped singing: A diary of Ramallah under siege' by Raja Shehadeh

'Twenty Questions on Palestine' edited by Hugh Humphries

'Ibn Fadlan and the Land of Darkness: Arab Travellers in the Far North'

'Global Interactions in the Early Modern Age, 1400-1800' by Charles H. Parker

'A World in Crisis: A Marxist Analysis for the 1990s" by the Committee for a Workers' International

'Gangsta Rap' by Benjamin Zephaniah

'A Christmas Carol' by Charles Dickens [Re-read]

'The Illusionist' by Jennifer Johnston

0 notes

Text

The Road Gets Bumpy, but Theatre Charlotte’s Christmas Carol Prevails at CP

The Road Gets Bumpy, but Theatre Charlotte’s Christmas Carol Prevails at CP

Review: A Christmas Carol at Halton Theater By Perry Tannenbaum Almost a year ago, fire struck the Theatre Charlotte building on Queens Road, gouging a sizable trench in its auditorium and destroying its electrical equipment. Repairs and renovations will hopefully be completed in time for the launch of the company’s 95th season next fall, but meanwhile, actors, directors, designers, and…

View On WordPress

#Aedan Coughlin#Belinda#Beth Killion#Charles Dickens#Chip Bradley#Chris Timmons#Emma Corrigan#Gordon Olson#Halton Theater#Hank West#Jill Bloede#Jim Eddings#Josh Logsdon#Julius Arthur Leonard#Mike Corrigan#Mitzi Corrigan#Rebecca Kirby#Riley Smith#Suzanne Newsom#Thom Tonetti#Vanessa Davis

0 notes

Text

Personally I’m more of a Charles dickens man myself but I’m reading Julius Caesar in school right now and that is a banger play

I shall anon reveal my diabolical schemes, mine misdeeds, my wickedness...it shall breaketh thou f'r sure...

I HATH DONE THY MOTHER

56 notes

·

View notes

Photo

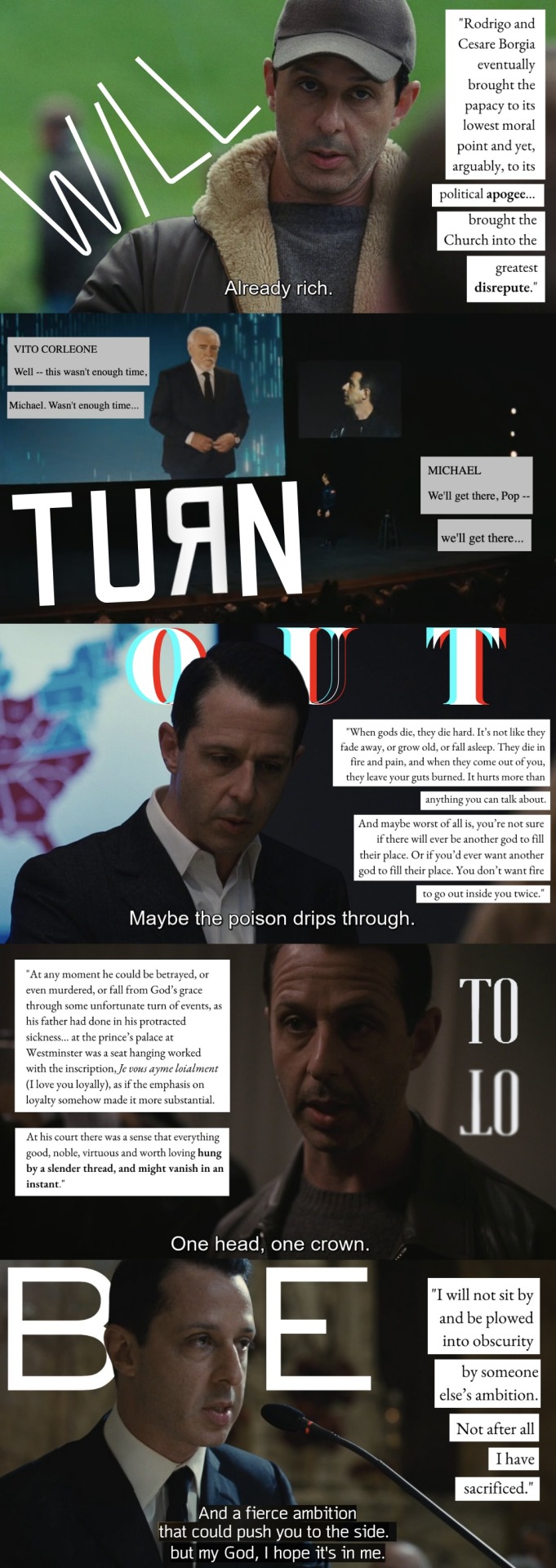

Neoreactionary Curtis Yarvin makes an extended case for the Oxfordian answer to the Shakespeare authorship question. Or what passes for a case anyway. Mostly this great hater of democracy and populism just demagogues for his presumedly puerile audience, labeling Shakespeare—as in the actual Will from Stratford—a “rentboy” and an “illiterate Ghanian immigrant.” His clever idea is to set up the Stratford thesis as an anticipation of today’s diversity-and-equity critique of the canon.

Then he assails a straw man, the supposed Stratfordian belief that Shakespeare was a “democrat,” which nobody believes. Shakespeare fully expresses his view of “people power” in Julius Caesar’s popular sparagmos of Cinna the Poet. And if Julius Caesar held the early American stage and then became the staple American high school text, it was because the drama celebrates not democracy, which Shakespeare didn’t distinguish from resentful and fanatic mob violence, but republicanism in the tragic figure of Brutus.

As for Shakespeare’s overall politics, well, it’s always hard to say with a dramatist, who stages conflicts rather than enumerating theses, and this chameleon poet makes it harder than most. Yarvin quotes every reactionary’s favorite passage, Ulysses’s hymn to degree from Troilus and Cressida, but this is the utterance of a single dramatic character. Rosenkrantz—a sycophantic idiot—argues the same case in Hamlet while kissing Claudius’s ring. By contrast, that play’s hero pronounces what I suspect to be closer to the poet’s own political credo: “The king is a thing of nothing.”

In my reading, Shakespeare is a political nihilist, placing his faith in no institution and no ambitious men. He’s lyrical, where he is lyrical, only about love and private life and nature: precisely the quasi-anarchist (not democratic) anti-politics I find throughout modernity in writers who hail from the lower middle class—Yarvin, like a Marxoid polemicist, abuses the bard with this label too—from Keats to Dickens to Joyce (see my essay on Les Murray for a longer explanation).

But the strongest argument against Oxford’s claim is literary. Does de Vere’s da-dum da-dum doggerel really “rock” like Shakespeare? I count only one potential metrical inversion: in the first foot of the first line, “is” may be stressed for interrogatory emphasis, mainly because the line is short a syllable. But even if you read all the interrogatives as stressed, which you don’t have to, that’s hardly a poetically surprising reversal. Otherwise, the thing tick-tocks robotically like a metronome. Similarly, “the way he plays with the caesura”—what way? The caesura is precisely where we’d expect it to be in each line, not least because Oxford punctuates six of the 10 lines right in the middle, between two balanced sets of iambic feet. I can only conclude that Yarvin relies on an audience ignorant of his subject.

Ulysses’s speech, by contrast, is in Shakespeare’s general style, or at least his mature style, gnarled and enjambed, bristling less with neat Metaphysical paradoxes than with a careering rush of concrete and mingled tropes. Here is play with the caesura, sound mimicking sense: “And, hark, what discord follows! each thing meets...” Likewise, I recall that Frank Kermode thought hendiadys the Shakespearean rhetorical signature, sign of his copiousness and bounty: “Divert and crack, rend and deracinate / The unity and married calm of states.”

A more sophisticated reactionary would say that this apparently disordered and undisciplined style is just what we’d expect from a half-educated rube off the farm who could only read the classics in translation. But what do I know? I myself am just a scion of the anarchic lower middle class, while Yarvin, as he likes to remind us, is a descendant of that very oligarchic bureaucracy from which he promises, eventually, to deliver us.

#william shakespeare#curtis yarvin#edward de vere#literary criticism#neoreaction#poetry#english literature

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

louis' bookshelf: the begin again reading list

I forgot to post this after I finished the fic, but these are the sources for all the thematically relevant references in Begin Again. I know my writing style can be polarizing, but I was so flattered and excited by the enthusiasm for my love of intertextuality, so these are the pieces of writing that inspired me. They're listed in order of appearance!

-

Macbeth by William Shakespeare

Homer's Iliad

The Unabridged Journals by Sylvia Plath

Prometheus Bound by Aeschylus

Almagest by Claudius Ptolemy

Hamlet by William Shakespeare

Vergil's Aeneid

Bello Gallico by Julius Caesar

Lives of the Twelve Caesars by Suetonius

Bucolic II by Vergil

Summa Theologica by Thomas Aquinas

The Fairy Tales by Hans Christian Andersen

Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë

Dracula by Bram Stoker

Dr. Zhivago by Boris Pasternak

The Raven by Edgar Allan Poe

The Double by Fyodor Dostoevsky

Doctor Faustus by Christopher Marlowe

Dante's Divine Comedy

The Goblin Market by Christina Rossetti

Othello by William Shakespeare

Gray's Anatomy by Henry Gray

A Critique of Pure Reason by Immanuel Kant

God is Dead by Friedrich Nietzsche

The Stranger by Albert Camus

Paradise Lost by John Milton

Candide by Voltaire

Les Fleurs du mal by Charles Baudelaire

Much Ado About Nothing by William Shakespeare

Frankenstein by Mary Shelley

The Arthurian Romances by Chretien de Troyes

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll

David Copperfield by Charles Dickens

The Faerie Queene by Edmund Spenser

De Clementia by Seneca the Younger

The Prince by Niccolò Machiavelli

Life Without Principle by Henry David Thoreau

Two Treatises of Government by John Locke

The Spirit of the Laws by Baron de Montesquieu

Bello Civili by Julius Caesar

The Brothers Karamazov by Fyodor Dostoevsky

Lenore by Edgar Allan Poe

Cyrano de Bergerac by Edmond Rostand

#maybe someday i'll make you all read my director's commentary where i pepe silvia the themes#fic: begin again#vc

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Read Like a Gilmore

All 339 Books Referenced In “Gilmore Girls”

Not my original list, but thought it’d be fun to go through and see which one’s I’ve actually read :P If it’s in bold, I’ve got it, and if it’s struck through, I’ve read it. I’ve put a ‘read more’ because it ended up being an insanely long post, and I’m now very sad at how many of these I haven’t read. (I’ve spaced them into groups of ten to make it easier to read)

1. 1984 by George Orwell 2. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain 3. Alice in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll 4. The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay by Michael Chabon 5. An American Tragedy by Theodore Dreiser 6. Angela’s Ashes by Frank McCourt 7. Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy 8. The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank 9. The Archidamian War by Donald Kagan 10. The Art of Fiction by Henry James

11. The Art of War by Sun Tzu 12. As I Lay Dying by William Faulkner 13. Atonement by Ian McEwan 14. Autobiography of a Face by Lucy Grealy 15. The Awakening by Kate Chopin 16. Babe by Dick King-Smith 17. Backlash: The Undeclared War Against American Women by Susan Faludi 18. Balzac and the Little Chinese Seamstress by Dai Sijie 19. Bel Canto by Ann Patchett 20. The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath 21. Beloved by Toni Morrison 22. Beowulf: A New Verse Translation by Seamus Heaney 23. The Bhagava Gita 24. The Bielski Brothers: The True Story of Three Men Who Defied the Nazis, Built a Village in the Forest, and Saved 1,200 Jews by Peter Duffy 25. Bitch in Praise of Difficult Women by Elizabeth Wurtzel 26. A Bolt from the Blue and Other Essays by Mary McCarthy 27. Brave New World by Aldous Huxley 28. Brick Lane by Monica Ali 29. Bridgadoon by Alan Jay Lerner 30. Candide by Voltaire 31. The Canterbury Tales by Chaucer 32. Carrie by Stephen King 33. Catch-22 by Joseph Heller 34. The Catcher in the Rye by J. D. Salinger 35. Charlotte’s Web by E. B. White 36. The Children’s Hour by Lillian Hellman 37. Christine by Stephen King 38. A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens 39. A Clockwork Orange by Anthony Burgess 40. The Code of the Woosters by P.G. Wodehouse 41. The Collected Stories by Eudora Welty 42. A Comedy of Errors by William Shakespeare 43. Complete Novels by Dawn Powell 44. The Complete Poems by Anne Sexton 45. Complete Stories by Dorothy Parker 46. A Confederacy of Dunces by John Kennedy Toole 47. The Count of Monte Cristo by Alexandre Dumas 48. Cousin Bette by Honore de Balzac 49. Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoevsky 50. The Crimson Petal and the White by Michel Faber 51. The Crucible by Arthur Miller 52. Cujo by Stephen King 53. The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time by Mark Haddon 54. Daughter of Fortune by Isabel Allende 55. David and Lisa by Dr Theodore Issac Rubin M.D 56. David Copperfield by Charles Dickens 57. The Da Vinci Code by Dan Brown 58. Dead Souls by Nikolai Gogol 59. Demons by Fyodor Dostoyevsky 60. Death of a Salesman by Arthur Miller 61. Deenie by Judy Blume 62. The Devil in the White City: Murder, Magic, and Madness at the Fair that Changed America by Erik Larson 63. The Dirt: Confessions of the World’s Most Notorious Rock Band by Tommy Lee, Vince Neil, Mick Mars and Nikki Sixx 64. The Divine Comedy by Dante 65. The Divine Secrets of the Ya-Ya Sisterhood by Rebecca Wells 66. Don Quixote by Cervantes 67. Driving Miss Daisy by Alfred Uhrv 68. Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde by Robert Louis Stevenson 69. Edgar Allan Poe: Complete Tales & Poems by Edgar Allan Poe 70. Eleanor Roosevelt by Blanche Wiesen Cook 71. The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test by Tom Wolfe 72. Ella Minnow Pea: A Novel in Letters by Mark Dunn 73. Eloise by Kay Thompson 74. Emily the Strange by Roger Reger 75. Emma by Jane Austen 76. Empire Falls by Richard Russo 77. Encyclopedia Brown: Boy Detective by Donald J. Sobol 78. Ethan Frome by Edith Wharton 79. Ethics by Spinoza 80. Europe through the Back Door, 2003 by Rick Steves

81. Eva Luna by Isabel Allende 82. Everything Is Illuminated by Jonathan Safran Foer 83. Extravagance by Gary Krist 84. Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury 85. Fahrenheit 9/11 by Michael Moore 86. The Fall of the Athenian Empire by Donald Kagan 87. Fat Land: How Americans Became the Fattest People in the World by Greg Critser 88. Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas by Hunter S. Thompson 89. The Fellowship of the Ring by J. R. R. Tolkien 90. Fiddler on the Roof by Joseph Stein 91. The Five People You Meet in Heaven by Mitch Albom 92. Finnegan’s Wake by James Joyce 93. Fletch by Gregory McDonald 94. Flowers for Algernon by Daniel Keyes 95. The Fortress of Solitude by Jonathan Lethem 96. The Fountainhead by Ayn Rand 97. Frankenstein by Mary Shelley 98. Franny and Zooey by J. D. Salinger 99. Freaky Friday by Mary Rodgers 100. Galapagos by Kurt Vonnegut 101. Gender Trouble by Judith Butler 102. George W. Bushism: The Slate Book of the Accidental Wit and Wisdom of our 43rd President by Jacob Weisberg 103. Gidget by Fredrick Kohner 104. Girl, Interrupted by Susanna Kaysen 105. The Gnostic Gospels by Elaine Pagels 106. The Godfather: Book 1 by Mario Puzo 107. The God of Small Things by Arundhati Roy 108. Goldilocks and the Three Bears by Alvin Granowsky 109. Gone with the Wind by Margaret Mitchell 110. The Good Soldier by Ford Maddox Ford

111. The Gospel According to Judy Bloom 112. The Graduate by Charles Webb 113. The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck 114. The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald 115. Great Expectations by Charles Dickens 116. The Group by Mary McCarthy 117. Hamlet by William Shakespeare 118. Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire by J. K. Rowling 119. Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone by J. K. Rowling 120. A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius by Dave Eggers 121. Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad 122. Helter Skelter: The True Story of the Manson Murders by Vincent Bugliosi and Curt Gentry 123. Henry IV, part I by William Shakespeare 124. Henry IV, part II by William Shakespeare 125. Henry V by William Shakespeare 126. High Fidelity by Nick Hornby 127. The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire by Edward Gibbon 128. Holidays on Ice: Stories by David Sedaris 129. The Holy Barbarians by Lawrence Lipton 130. House of Sand and Fog by Andre Dubus III 131. The House of the Spirits by Isabel Allende 132. How to Breathe Underwater by Julie Orringer 133. How the Grinch Stole Christmas by Dr. Seuss 134. How the Light Gets In by M. J. Hyland 135. Howl by Allen Ginsberg 136. The Hunchback of Notre Dame by Victor Hugo 137. The Iliad by Homer 138. I’m With the Band by Pamela des Barres 139. In Cold Blood by Truman Capote 140. Inferno by Dante

141. Inherit the Wind by Jerome Lawrence and Robert E. Lee 142. Iron Weed by William J. Kennedy 143. It Takes a Village by Hillary Rodham Clinton 144. Jane Eyre by Charlotte Bronte 145. The Joy Luck Club by Amy Tan 146. Julius Caesar by William Shakespeare 147. The Jumping Frog by Mark Twain 148. The Jungle by Upton Sinclair 149. Just a Couple of Days by Tony Vigorito 150. The Kitchen Boy: A Novel of the Last Tsar by Robert Alexander 151. Kitchen Confidential: Adventures in the Culinary Underbelly by Anthony Bourdain 152. The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini 153. Lady Chatterleys’ Lover by D. H. Lawrence 154. The Last Empire: Essays 1992-2000 by Gore Vidal 155. Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman 156. The Legend of Bagger Vance by Steven Pressfield 157. Less Than Zero by Bret Easton Ellis 158. Letters to a Young Poet by Rainer Maria Rilke 159. Lies and the Lying Liars Who Tell Them by Al Franken 160. Life of Pi by Yann Martel

161. Little Dorrit by Charles Dickens 162. The Little Locksmith by Katharine Butler Hathaway 163. The Little Match Girl by Hans Christian Andersen 164. Little Women by Louisa May Alcott 165. Living History by Hillary Rodham Clinton 166. Lord of the Flies by William Golding 167. The Lottery: And Other Stories by Shirley Jackson 168. The Lovely Bones by Alice Sebold 169. The Love Story by Erich Segal 170. Macbeth by William Shakespeare 171. Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert 172. The Manticore by Robertson Davies 173. Marathon Man by William Goldman 174. The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov 175. Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter by Simone de Beauvoir 176. Memoirs of General W. T. Sherman by William Tecumseh Sherman 177. Me Talk Pretty One Day by David Sedaris 178. The Meaning of Consuelo by Judith Ortiz Cofer 179. Mencken’s Chrestomathy by H. R. Mencken 180. The Merry Wives of Windsor by William Shakespeare 181. The Metamorphosis by Franz Kafka 182. Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides 183. The Miracle Worker by William Gibson 184. Moby Dick by Herman Melville 185. The Mojo Collection: The Ultimate Music Companion by Jim Irvin 186. Moliere: A Biography by Hobart Chatfield Taylor 187. A Monetary History of the United States by Milton Friedman 188. Monsieur Proust by Celeste Albaret 189. A Month Of Sundays: Searching For The Spirit And My Sister by Julie Mars 190. A Moveable Feast by Ernest Hemingway

191. Mrs. Dalloway by Virginia Woolf 192. Mutiny on the Bounty by Charles Nordhoff and James Norman Hall 193. My Lai 4: A Report on the Massacre and It’s Aftermath by Seymour M. Hersh 194. My Life as Author and Editor by H. R. Mencken 195. My Life in Orange: Growing Up with the Guru by Tim Guest 196. Myra Waldo’s Travel and Motoring Guide to Europe, 1978 by Myra Waldo 197. My Sister’s Keeper by Jodi Picoult 198. The Naked and the Dead by Norman Mailer 199. The Name of the Rose by Umberto Eco 200. The Namesake by Jhumpa Lahiri 201. The Nanny Diaries by Emma McLaughlin 202. Nervous System: Or, Losing My Mind in Literature by Jan Lars Jensen 203. New Poems of Emily Dickinson by Emily Dickinson 204. The New Way Things Work by David Macaulay 205. Nickel and Dimed by Barbara Ehrenreich 206. Night by Elie Wiesel 207. Northanger Abbey by Jane Austen 208. The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism by William E. Cain, Laurie A. Finke, Barbara E. Johnson, John P. McGowan 209. Novels 1930-1942: Dance Night/Come Back to Sorrento, Turn, Magic Wheel/Angels on Toast/A Time to be Born by Dawn Powell 210. Notes of a Dirty Old Man by Charles Bukowski

211. Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck (will NEVER read again) 212. Old School by Tobias Wolff 213. On the Road by Jack Kerouac 214. One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest by Ken Kesey 215. One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel Garcia Marquez 216. The Opposite of Fate: Memories of a Writing Life by Amy Tan 217. Oracle Night by Paul Auster 218. Oryx and Crake by Margaret Atwood 219. Othello by Shakespeare 220. Our Mutual Friend by Charles Dickens 221. The Outbreak of the Peloponnesian War by Donald Kagan 222. Out of Africa by Isac Dineson 223. The Outsiders by S. E. Hinton 224. A Passage to India by E.M. Forster 225. The Peace of Nicias and the Sicilian Expedition by Donald Kagan 226. The Perks of Being a Wallflower by Stephen Chbosky 227. Peyton Place by Grace Metalious 228. The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde 229. Pigs at the Trough by Arianna Huffington 230. Pinocchio by Carlo Collodi 231. Please Kill Me: The Uncensored Oral History of Punk Legs McNeil and Gillian McCain 232. The Polysyllabic Spree by Nick Hornby 233. The Portable Dorothy Parker by Dorothy Parker 234. The Portable Nietzche by Fredrich Nietzche 235. The Price of Loyalty: George W. Bush, the White House, and the Education of Paul O’Neill by Ron Suskind 236. Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen 237. Property by Valerie Martin 238. Pushkin: A Biography by T. J. Binyon 239. Pygmalion by George Bernard Shaw 240. Quattrocento by James Mckean

241. A Quiet Storm by Rachel Howzell Hall 242. Rapunzel by Grimm Brothers 243. The Raven by Edgar Allan Poe 244. The Razor’s Edge by W. Somerset Maugham 245. Reading Lolita in Tehran: A Memoir in Books by Azar Nafisi 246. Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier 247. Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm by Kate Douglas Wiggin 248. The Red Tent by Anita Diamant 249. Rescuing Patty Hearst: Memories From a Decade Gone Mad by Virginia Holman 250. The Return of the King by J. R. R. Tolkien 251. R Is for Ricochet by Sue Grafton 252. Rita Hayworth by Stephen King 253. Robert’s Rules of Order by Henry Robert 254. Roman Holiday by Edith Wharton 255. Romeo and Juliet by William Shakespeare 256. A Room of One’s Own by Virginia Woolf 257. A Room with a View by E. M. Forster 258. Rosemary’s Baby by Ira Levin 259. The Rough Guide to Europe, 2003 Edition 260. Sacred Time by Ursula Hegi 261. Sanctuary by William Faulkner 262. Savage Beauty: The Life of Edna St. Vincent Millay by Nancy Milford 263. Say Goodbye to Daisy Miller by Henry James 264. The Scarecrow of Oz by Frank L. Baum 265. The Scarlet Letter by Nathaniel Hawthorne 266. Seabiscuit: An American Legend by Laura Hillenbrand 267. The Second Sex by Simone de Beauvoir 268. The Secret Life of Bees by Sue Monk Kidd 269. Secrets of the Flesh: A Life of Colette by Judith Thurman 270. Selected Hotels of Europe

271. Selected Letters of Dawn Powell: 1913-1965 by Dawn Powell 272. Sense and Sensibility by Jane Austen 273. A Separate Peace by John Knowles 274. Several Biographies of Winston Churchill 275. Sexus by Henry Miller 276. The Shadow of the Wind by Carlos Ruiz Zafon 277. Shane by Jack Shaefer 278. The Shining by Stephen King 279. Siddhartha by Hermann Hesse 280. S Is for Silence by Sue Grafton 281. Slaughter-house Five by Kurt Vonnegut 282. Small Island by Andrea Levy 283. Snows of Kilimanjaro by Ernest Hemingway 284. Snow White and Rose Red by Grimm Brothers 285. Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy: Lord and Peasant in the Making of the Modern World by Barrington Moore 286. The Song of Names by Norman Lebrecht 287. Song of the Simple Truth: The Complete Poems of Julia de Burgos by Julia de Burgos 288. The Song Reader by Lisa Tucker 289. Songbook by Nick Hornby 290. The Sonnets by William Shakespeare 291. Sonnets from the Portuegese by Elizabeth Barrett Browning 292. Sophie’s Choice by William Styron 293. The Sound and the Fury by William Faulkner 294. Speak, Memory by Vladimir Nabokov 295. Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach 296. The Story of My Life by Helen Keller 297. A Streetcar Named Desiree by Tennessee Williams 298. Stuart Little by E. B. White 299. Sun Also Rises by Ernest Hemingway 300. Swann’s Way by Marcel Proust

301. Swimming with Giants: My Encounters with Whales, Dolphins and Seals by Anne Collett 302. Sybil by Flora Rheta Schreiber 303. A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens 304. Tender Is The Night by F. Scott Fitzgerald 305. Term of Endearment by Larry McMurtry 306. Time and Again by Jack Finney 307. The Time Traveler’s Wife by Audrey Niffenegger 308. To Have and Have Not by Ernest Hemingway 309. To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee 310. The Tragedy of Richard III by William Shakespeare 311. A Tree Grows in Brooklyn by Betty Smith 312. The Trial by Franz Kafka 313. The True and Outstanding Adventures of the Hunt Sisters by Elisabeth Robinson 314. Truth & Beauty: A Friendship by Ann Patchett 315. Tuesdays with Morrie by Mitch Albom 316. Ulysses by James Joyce 317. The Unabridged Journals of Sylvia Plath 1950-1962 by Sylvia Plath 318. Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe 319. Unless by Carol Shields 320. Valley of the Dolls by Jacqueline Susann

321. The Vanishing Newspaper by Philip Meyers 322. Vanity Fair by William Makepeace Thackeray 323. Velvet Underground’s The Velvet Underground and Nico (Thirty Three and a Third series) by Joe Harvard 324. The Virgin Suicides by Jeffrey Eugenides 325. Waiting for Godot by Samuel Beckett 326. Walden by Henry David Thoreau 327. Walt Disney’s Bambi by Felix Salten 328. War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy 329. We Owe You Nothing – Punk Planet: The Collected Interviews edited by Daniel Sinker 330. What Colour is Your Parachute? 2005 by Richard Nelson Bolles 331. What Happened to Baby Jane by Henry Farrell 332. When the Emperor Was Divine by Julie Otsuka 333. Who Moved My Cheese? by Spencer Johnson 334. Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf by Edward Albee 335. Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West by Gregory Maguire 336. The Wizard of Oz by Frank L. Baum 337. Wuthering Heights by Emily Bronte 338. The Yearling by Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings 339. The Year of Magical Thinking by Joan Didion

113 notes

·

View notes