#Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Visitors admire the newly restored Edicule on 21 March 2017. The floor beneath the shrine is at risk of structural failure, scientists warn.

📷: Oded Balilty, AP for National Geographic

By Kristin Romey

8 September 2023

Over the centuries, Jerusalem’s Church of the Holy Sepulchre has suffered violent attacks, fires, and earthquakes.

It was totally destroyed in 1009 and subsequently rebuilt, leading modern scholars to question whether it could possibly be the site identified as the burial place of Christ by a delegation sent from Rome some 17 centuries ago.

The results of scientific tests provided to National Geographic appear to confirm that the remains of a limestone cave enshrined within the church are indeed remnants of the tomb located by the ancient Romans.

Mortar sampled from between the original limestone surface of the tomb and a marble slab that covers it has been dated to around A.D. 345.

According to historical accounts, the tomb was discovered by the Romans and enshrined around 326.

Until now, the earliest architectural evidence found in and around the tomb complex dated to the Crusader period, making it no older than 1,000 years.

While it is archaeologically impossible to say that the tomb is the burial site of an individual Jew known as Jesus of Nazareth, who according to New Testament accounts was crucified in Jerusalem in 30 or 33, new dating results put the original construction of today's tomb complex securely in the time of Constantine, Rome's first Christian emperor.

The tomb was opened for the first time in centuries in October 2016, when the shrine that encloses the tomb, known as the Edicule, underwent a significant restoration by an interdisciplinary team from the National Technical University of Athens.

People line up to visit the renovated Edicule, the shrine that houses what is believed to be the tomb of Christ.

📷: Oded Balilty, AP for National Geographic

Several samples of mortar from different locations within the Edicule were taken at that time for dating, and the results were recently provided to National Geographic by Chief Scientific Supervisor Antonia Moropoulou, who directed the Edicule restoration project.

When Constantine's representatives arrived in Jerusalem around 325 to locate the tomb, they were allegedly pointed to a Roman temple built some 200 years earlier.

The Roman temple was razed and excavations beneath it revealed a tomb hewn from a limestone cave.

The top of the cave was sheared off to expose the interior of the tomb, and the Edicule was built around it.

A feature of the tomb is a long shelf, or "burial bed," which, according to tradition, was where the body of Jesus Christ was laid out following crucifixion.

Such shelves and niches, hewn from limestone caves, are a common feature in tombs of wealthy 1st-century Jerusalem Jews.

The marble cladding that covers the "burial bed" is believed to have been installed in 1555 at the latest, and most likely was present since the mid-1300s, according to pilgrim accounts.

When the tomb was opened on the night of 26 October 2016, scientists were surprised by what they found beneath the marble cladding: an older, broken marble slab incised with a cross, resting directly atop the original limestone surface of the "burial bed."

A conservator cleans the surface of the stone slab venerated as the final resting place of Jesus Christ.

📷: Oded Balilty, AP for National Geographic

Some researchers speculated that this older slab may have been laid down in the Crusader period, while others offered an earlier date, suggesting that it may have already been in place and broken when the church was destroyed in 1009.

No one, however, was ready to claim that this might be the first physical evidence for the earliest Roman shrine on the site.

The new test results, which reveal the lower slab was most likely mortared in place in the mid-fourth century under the orders of Emperor Constantine, come as a welcome surprise to those who study the history of the sacred monument.

"Obviously, that date is spot-on for whatever Constantine did," says archaeologist Martin Biddle, who published a seminal study on the history of the tomb in 1999. "That's very remarkable."

During their year-long restoration of the Edicule, the scientists were also able to determine that a significant amount of the burial cave remains enclosed within the walls of the shrine.

Mortar samples taken from remains of the southern wall of the cave were dated to 335 and 1570, which provide additional evidence for construction works from the Roman period, as well as a documented 16th-century restoration.

Franciscan priests visit the traditional site of Jesus' tomb during its renovation in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

📷: Oded Balilty, AP for National Geographic

Mortar taken from the tomb entrance has been dated to the 11th century and is consistent with the reconstruction of the Edicule following its destruction in 1009.

"It is interesting how [these] mortars not only provide evidence for the earliest shrine on the site but also confirm the historical construction sequence of the Edicule," Moropoulou observes.

The mortar samples were independently dated at two separate labs using optically stimulated luminescence (OSL), a technique that determines when quartz sediment was most recently exposed to light.

The scientific results were published by Moropoulou and her team in 2018 issue of the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports.

NOTE: This article was originally published on 28 November 2017 and updated to reflect the publication of the journal article on the dating of the mortar.

#Jesus#Tomb of Jesus#Church of the Holy Sepulchre#Jerusalem#limestone cave#Jesus of Nazareth#Edicule#National Technical University of Athens#Antonia Moropoulou#Crusader period#Ancient Rome#Martin Biddle#optically stimulated luminescence (OSL)#Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports#archaeology#Emperor Constantine#National Geographic#AP#Oded Balilty#tomb#mortar#restoration#renovation#holy site

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Studi / Archeologia, le slitte da trebbiatura erano già in uso nella Grecia di 8.500 anni fa: la scoperta dell'Università di Pisa

Studi / Archeologia, le slitte da trebbiatura erano già in uso nella Grecia di 8.500 anni fa: la scoperta dell'Università di Pisa

Redazione In uso fino a pochi decenni fa per separare la paglia dal grano in moltissimi paesi Mediterranei, dalla Turchia fino alla Spagna, la slitta da trebbiatura avrebbe fatto la sua comparsa in Grecia già nel 6500 a.C. A dirlo è uno studio recente condotto da un gruppo internazionale di ricercatori, guidato dall’Università di Pisa, che applicando metodi analitici avanzati alle industrie in…

View On WordPress

#CSIC#Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports#Mediterraneo#neolitico#Niccolò Mazzucco#slitta da trebbiatura#trebbiatura#Università Aristotele di Salonicco#Università di Pisa

0 notes

Text

Animal Rock Art in China's Jinsha River Valley: Dating Reveals 7.09–8.93 ka Origins

via Journal of Archaeological Science, Reports, August 2023: Over 70 ancient animal rock art sites found in China's Jinsha River valley, including Baiyunwan shelter; art estimated 7.09–8.93 thousand years old.

via Journal of Archaeological Science, Reports, August 2023: A study in the Jinsha River valley, in Yunnan, China, reveals over 70 rock painting sites with naturalistic animal art, including the Baiyunwan rock shelter, and estimates the paintings’ age range at 7.09–8.93 thousand years ago. More than 70 rock painting sites have been discovered in the Jinsha River valley in northwestern Yunnan…

View On WordPress

#China#Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports#research papers#rock art#Uranium Series Dating#Yunnan (province)

0 notes

Text

The theory – promoted by experts including the Pulitzer prize-winning author Jared Diamond – suggests islanders chopped down palm trees at an unsustainable rate to create gardens, harvest fuel and move statues, which brought on disaster. As a result, the population encountered by Europeans in the 18th century was a shadow of what it had once been. However, a new study has added to a growing body of evidence offering a very different view. “Our study confirms that the island couldn’t have supported more than a few thousand people,” said Dr Dylan Davis, a co-author of the work from Columbia University. “As such, contrary to the ecocide narrative, the population present at European arrival wasn’t the remnants of Rapa Nui society, but was likely the society at its peak, living at the levels that were sustainable on the island.” Writing in the journal Science Advances, Davis and colleagues reported how they harnessed high-resolution shortwave infrared and near-infrared satellite imagery and machine learning to identify archaeological sites of rock gardening – a practice employed by the inhabitants of Easter Island to grow crops, including sweet potatoes. The results suggest only 0.76 km2 of land was used in this way – far below previous estimates which, the team said, misidentified features such natural lava flows. As a result, Davis and colleagues have suggested that rock gardening alone could only have supported about 3,900 people at most, a long way off previous estimates of up to 17,000. Indeed, the average figure is just 2,000 people, although this could be increased to up to 4,000 people if other foods, for example from fishing or foraging, are considered. “One of the major arguments for an ‘ecocide’ was that the populations must have been very large in order to build all of the moai statues,” said Davis. “However, archaeological evidence does not support a large population and studies of the moai themselves suggest that a small population could have built and moved them. It just required cooperation.”

21 June 2024

"Easter Island was not a case of self-inflicted ‘ecocide’, as Jared Diamond has contended in Collapse (2005). Instead, the locals of Rapa Nui lived sustainably until the 19th century, when they were devastated by colonialism and disease. By 1877, they numbered just 111." -- Luke Kemp

371 notes

·

View notes

Text

New Mexico Footprints are Oldest Sign of Humans in Americas

Fossil footprints date back to between 21,000 and 23,000 years ago, upending previous theory that humans reached continent later.

New research confirms that fossil human footprints in New Mexico are probably the oldest direct evidence of human presence in the Americas, a finding that upends what many archaeologists thought they knew.

The footprints were discovered at the edge of an ancient lakebed in White Sands national park and date back to between 21,000 and 23,000 years ago, according to research published on Thursday in the journal Science.

The estimated age of the footprints was first reported in Science in 2021, but some researchers raised concerns about the dates. Questions focused on whether seeds of aquatic plants used for the original dating may have absorbed ancient carbon from the lake – which could, in theory, throw off radiocarbon dating by thousands of years.

The new study presents two additional lines of evidence for the older date range. It uses two entirely different materials found at the site, ancient conifer pollen and quartz grains.

The reported age of the footprints challenges the once conventional wisdom that humans did not reach the Americas until a few thousand years before rising sea levels covered the Bering land bridge between Russia and Alaska, perhaps about 15,000 years ago.

“This is a subject that’s always been controversial because it’s so significant – it’s about how we understand the last chapter of the peopling of the world,” said Thomas Urban, an archaeological scientist at Cornell University, who was involved in the 2021 study but not the new one.

Thomas Stafford, an independent archaeological geologist in Albuquerque, New Mexico, who was not involved in the study, said he “was a bit skeptical before” but now is convinced.

The new study isolated about 75,000 grains of pure pollen from the same sedimentary layer that contained the footprints.

“Dating pollen is arduous and nail-biting,” said Kathleen Springer, a research geologist at the US Geological Survey and a co-author of the new paper.

Ancient footprints of any kind can provide archaeologists with a snapshot of a moment in time. While other archeological sites in the Americas point to similar date ranges – including pendants carved from giant ground sloth remains in Brazil – scientists still question whether such materials really indicate human presence.

“White Sands is unique because there’s no question these footprints were left by people, it’s not ambiguous,” said Jennifer Raff, an anthropological geneticist at the University of Kansas, who was not involved in the study.

#New Mexico Footprints are Oldest Sign of Humans in Americas#fossil#fossil footprints#White Sands national park#ancient artifacts#geology#geologist#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#ancient man

702 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Centuries ago, two people were buried arm in arm on top of a horse in what is now Austria. The unique burial prompted archaeologists to think that the two were a male-female married couple from medieval times. But it turns out they couldn't have been more wrong.

A new analysis of the remains suggests that the couple was actually a mother-daughter pair who died around 1,800 years ago during the Roman era.

"It's the first genetically proven mother-daughter burial in Austria in Roman times," study senior author Sylvia Kirchengast, a professor of evolutionary anthropology at the University of Vienna, told Live Science. "We also disprove a long-held misconception about the kind of relation between the two individuals.

In the new study the researchers re-evaluated the remains via radiocarbon dating, ancient DNA analysis and a visual inspection. They found that the bones belonged to individuals whose ages at death were 20 to 25 and 40 to 60 years old and lived around A.D. 200 when the Roman Empire held sway over the region. In a twist, both human skeletons turned out to be females, according to an anatomical analysis. DNA results confirmed their biological female status and showed they were first-degree relatives — meaning they were either sisters or mother and daughter, according to the study, which was published in the May issue of the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports.

Due to the pair's DNA results, their age difference and other factors, the researchers concluded that individuals were mother and daughter, with the daughter embracing the mother in the grave. "It's very unlikely that two sisters have an age difference of 20 years during those times. So we felt that it's more likely that they are a mother-daughter pair," Kirchengast said.

The inclusion of a horse and gold pendants strongly hints that the women were of high social status. It also indicates they were non-Roman elites. "To our knowledge it's extremely uncommon for Roman people to be buried with horses. They were not a 'horse-people'," study lead author Dominik Hagmann, an archaeologist at University of Vienna, told Live Science. He suspected these two individuals were from a Celtic culture still existing in Roman times. The Celts were more commonly buried horses with their owners.

There are other signs that the deceased were familiar with horses. "What I find odd is that the older skeleton shows signs of frequent horse riding," Kirchengast said. "Maybe both women were enthusiastic horse-riders.""

#I promise I will soon be back with new content#in the meantime here is a story that touched me deeply#history#women in history#antiquity#ancient world#archeology#women's history#roman tag#austria#austrian history#3rd century#roman empire#celts#celtic

92 notes

·

View notes

Text

Centuries of indigenous presence in the Amazon defy legal attempts to limit the rights of Brazil’s native peoples

A study made by Brazilian researchers and published on October 5 in the renowned scientific journal Science, one of the world’s most respected academic journals, has found solid evidence that a significant part of the Amazon region has been inhabited by traditional indigenous peoples for at least 12,000 years.

Over the course of five years of research, Vinícius Peripato and Luiz Aragão managed to identify the existence of 24 uncatalogued and completely unknown archaeological sites hidden beneath the forest.

Peripato, a geographer, holds a master’s degree in Remote Sensing from the National Institute for Space Research (INPE) and is about to complete his doctorate in the same field and institution. He is supervised by Professor Luiz Aragão, who holds a master’s and doctorate in Remote Sensing from INPE and co-authored the publication.

In order to understand every detail of this work, which tends to trigger profound reflections on some of the issues currently being debated in the country, such as the right of indigenous peoples to claim ownership of their traditional lands, Brazil Reports spoke to the two researchers.

Continue reading.

#brazil#politics#environmental justice#science#archaeology#brazilian politics#indigenous rights#mod nise da silveira#image description in alt#amazon rainforest

85 notes

·

View notes

Text

Professor Belle

Belle: Félix, can I go with you to the excavation site tomorrow?

Félix: Of course, but I'll need you to stay with me the whole time. I have a new group of students, and they'll need to focus. I don't want them thinking they have to babysit you.

Belle: No one has to babysit me. I'm a member of the research team. Right?

Félix: Yes, but the students might be skeptical of that. Not every person your age is as responsible and intelligent as you, and unfortunately, some people have a tendency to prejudge.

Belle: Well, that’s just dumb.

Davian: *laughing* It's good to know the youngest member of the research team can still act like a ten year old.

Belle: I'm responsible and intelligent, but nobody said I was a grownup.

Davian: Fair point.

Félix: But you are mature, and we can trust you. That's why you're allowed to come to the excavation site.

Belle: Yeah. Can you imagine my friends at the site? Junior would probably break stuff, and you'd always have to be getting Caroline down from a tree or something. I know I should only climb trees around the field station.

Davian: We'd be happier if you didn't climb trees anywhere, but you know the risks, so...

Belle: Evaluate my choices, right?

Davian: Right.

Belle: I'll be too busy to climb trees tomorrow anyway. I have discoveries to make and students to teach.

Félix: Oh? Are you taking over for me, Professor Belle?

Davian: She probably can teach them something, you know. She's already got more archaeological experience than they do.

Félix: I'll tell you what, Belle. Why don't I let you have a few minutes to instruct the students tomorrow? You can be my assistant. We'll practice this evening so you'll know what you want to say when the time comes.

Belle: Yay! I'm going to be the best assistant you've ever had, I promise!

Félix: I have no doubt.

Belle: So, if I'm going to the site tomorrow and I'm going to be busy all day, does that mean I can skip my math lesson?

Davian: No. It means you'll have to do extra lessons the day after. Just because you're in the rainforest and you're learning cool stuff that isn't in your school books, that doesn't mean you get to ignore them. Remember, there's still going to be a test.

Belle: So, I guess the right choice would be to get ready for the test. I just wish I liked math more.

Félix: It's okay if you don't like it. Nobody can force you to like things. I'm not friends with math either, and when I was your age I was much happier following my father all around Al-Simhara and making discoveries with him. But I had to study math as well, because I needed it to graduate high school and get into university.

Belle: I'm going to university some day. I guess that means I have to be nice to math, even if we're not friends.

Félix: Be nice to math and it'll be nice to you.

Belle: *giggling* By helping me get into university?

Félix: Exactly so.

Belle: I can live with that.

Davian: Now that we've got that settled, how about we do a little exploring before dinner? I'll bet we can find some awesome butterflies if we take that trail over there. Check out all the flowers. I hear tropical butterflies love those.

Belle: Yes! Félix, can Davian and I borrow your camera? I want to take pictures if we see any butterflies. Then I can identify them and write a paragraph for my science journal.

Félix: That sounds like a good idea. While you and Davian are out butterfly hunting, I'm going to catch up with Dr. Santiago. I'll see the two of you at dinner at the field station.

Davian: Sounds good.

Belle: If we find any butterflies, we'll tell you all about it!

Félix: I can hardly wait. Good luck.

Belle: I think it's more about scientific methodology than luck.

Félix: *smiling* In that case... good scientific methodology, Professor Belle. I await your report on your findings.

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Women’s history just richer.

Since its discovery in 2008, the skeleton of a high-ranking individual buried inside a tomb in the Iberian Peninsula between 3,200 and 2,200 years ago was thought to be the remains of a man. However, a new analysis reveals that this person was actually a woman.

Archaeologists in Spain dubbed the woman the "Ivory Lady" based on the bounty of grave goods found alongside her skeleton, including an ivory tusk surrounding her skull, flint, an ostrich eggshell, amber and a rock crystal dagger, according to a study published Thursday (July 6) in the journal Scientific Reports. For more than a decade, archaeologists believed that this individual was a man, even nicknaming him the "Ivory Merchant."

The first anthrological report determined that the individual was most likely male based on an analysis of the pelvis," study co-author Leonardo García Sanjuán, a professor of prehistory at the University of Seville in Spain, told Live Science. Because the skeleton's pelvic region wasn't well preserved, this new group of researchers used a different method to analyze the remains: They conducted an amelogenin peptide analysis of the skeleton's tooth enamel to see if it contained the AMELX gene, which is located on the X chromosome (one of the two sex chromosomes found in humans), according to a statement. They detected AMELX after testing two of the teeth. "This analysis told us precisely that the skeleton was female," García Sanjuán said.

A selection of grave goods buried with the Ivory Lady.

(Image credit: Miriam Lucianez Trivino)

While not much is known about who this woman was, the archaeologists think that at one time, she was the "highest-ranked person" in this particular society, García Sanjuán said. "During this time period, we were starting to see new forms of leadership in Western European societies," he said. "She was a leader who existed before kings and queens, and her status wasn't inherited, meaning that she was a leader based on her personal achievements, skills and personality." Her tomb is a rare example of a single-occupancy burial in this region, which provides further evidence of her high status during the Iberian Copper Age (2900 B.C. to 2650 B.C.). "The burial is special because it contains only one individual and isn't a [mass grave] with commingled bones," he said. "When we compared the grave goods with our database [of more than 2,000 grave sites in the area], we can clearly see that this woman stood head and shoulders above other individuals in terms of wealth and social status."

For instance, a nearby lavish Copper Age tomb holds the remains of at least 15 women; this grave may have been constructed to hold individuals who claimed descent from the Ivory Lady, the researchers said. Other burials in southern Spain, particularly of infants interred without grave goods, further reveals that during the Copper Age birthright didn't determine social status. The location of her tomb also provides insight into the ancient society that once resided there, according to the study. "In the last 15 years we've come to learn that this site was important and was the largest civilization site in Iberia," he said. "We think that this was a central gathering place that connected people from afar. It makes full sense that the Ivory Lady would be buried here."

This isn't the first time archaeologists have assigned a skeleton the wrong biological sex. "There have been other instances in which buried individuals were classified as male or female based on the assumptions of certain grave goods being given to men and women," he said. "This is a poor scientific practice and a cautionary tale."

Jennifer Nalewicki Live Science Staff Writer

Jennifer Nalewicki is a Salt Lake City-based journalist whose work has been featured in The New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, Popular Mechanics and more. She covers several science topics from planet Earth to paleontology and archaeology to health and culture. Prior to freelancing, Jennifer held an Editor role at Time Inc. Jennifer has a bachelor's degree in Journalism from The University of Texas at Austin.

55 notes

·

View notes

Text

Petén, Guatemala

Mayans used mercury was used to decorate ceremonial objects

The mercury was from another region there were no natural cinnabar deposits in those areas. So it was probably acquired by trade

Mercury sulfide, AKA cinnabar was found in three places where the mercury was at toxic threshold concentrations.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Only through chemical analysis were the researchers finally able to determine that the liquid was, in fact, wine, and thus to put together evidence of the arrangement’s being an elaborate sendoff for a Roman-era oenophile."

"Flavius got what he wanted--cremation, eternity in a wine jar--and the rest of us were fairly sure he wouldn't come back."

(...I want to write this story now.)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Finally, a real medieval elephant appears! Just not where you might expect.

Katie Hemer, Hugh Willmott, Jane Evans, and Michael Buckley have shown that this ring was made from an African elephant's (genus Loxodonta's) ivory tusk in the fifth or sixth century. It was probably used as a handle on a cloth bag. It was found in a grave in Scremby, Lincolnshire (UK), where it had been buried sometime between around 450 and 550 AD.

And this wasn't the only elephant ivory to show up thousands of miles away in northern Europe: elephant ivory rings have been found in over 70 cemeteries in the area that is now England, and some have been found in the area that is now northern Germany, too. These cemeteries seem to date to the period before the 7th century.

This particular elephant may have originated in the African Rift Valley, and its ivory may have been traded from the Kingdom of Aksum to Europe. The time when it was traded coincided with the political power of the Roman Empire crumbling in western Europe and some (but not all) trade routes being disrupted. Yet the world has always been interconnected: we can't ignore the history of any region or any time.

Katie A. Hemer, Hugh Willmott, Jane E. Evans, Michael Buckley, "Ivory from early Anglo-Saxon burials in Lincolnshire – A biomolecular study", Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 49 (2023), 103943, ISSN 2352-409X, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2023.103943. Read it here.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eccezionale scoperta in Austria: madre e figlia sepolte insieme al loro cavallo. E non nell'alto Medioevo, ma in epoca romana

Eccezionale scoperta in Austria: madre e figlia sepolte insieme al loro cavallo. E non nell'alto Medioevo, ma in epoca romana Tutti i dettagli dello studio su Storie & Archeostorie

Elena Percivaldi Nel 2004, durante i lavori di costruzione di un parcheggio sotterraneo a Wals, nell’Alta Austria, tornò alla luce una tomba di eccezionale interesse. La sepoltura conteneva i resti di due persone abbracciate, deposte insieme a quelli di almeno un cavallo. Date le sue caratteristiche, la tomba venne inizialmente datata all’alto Medioevo e attribuita a una coppia di sposi. Ma ora…

View On WordPress

#archeologia#Austria#Baiuvari#dna#Dominik Hagmann#doppia sepoltura#età romana#In evidenza#Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports#limes danubiano#necropoli#notizie#Ovilava#scavi#scavi archeologici#scoperte#sepolture#Università di Vienna#Wals

0 notes

Text

[Paper] New evidence of early Holocene naturalistic rock art in Jinsha River valley, southwestern China

via Journal of Archaeological Science Reports, August 2023: A recent study in the Jinsha River valley, China, has discovered over 70 rock painting sites featuring naturalistic animal paintings that bear similarities to the world's oldest hunting-gathering

via Journal of Archaeological Science Reports, August 2023: A recent study in the Jinsha River valley, China, has discovered over 70 rock painting sites featuring naturalistic animal paintings that bear similarities to the world’s oldest hunting-gathering rock art, with the age estimation of the Baiyunwan rock paintings falling between 7.09-8.93 thousand years ago, providing new evidence of early…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Iron oxide baked into Mesopotamian bricks confirms ancient magnetic field anomaly | Live Science

Ancient bricks from Mesopotamia have helped confirm a mysterious anomaly in Earth's magnetic field that occurred 3,000 years ago, a new study finds.

Brickmakers baked the bricks, which were imprinted with the names of Mesopotamian kings, between the third and first millennia B.C. Iron oxide grains within the clay recorded changes in Earth's magnetic field when the bricks were heated, enabling scientists to reconstruct changes in the magnetic field over time, the team reported in a study published in the journal PNAS on Monday (Dec. 18).

The finding may also help scientists date artifacts in the future, the team said.

"We often depend on dating methods such as radiocarbon dates to get a sense of chronology in ancient Mesopotamia," study co-author Mark Altaweel, a professor of Near East archaeology and archaeological data science at University College London, said in a statement. "However, some of the most common cultural remains, such as bricks and ceramics, cannot typically be easily dated because they don't contain organic material. This work now helps create an important dating baseline." ...

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

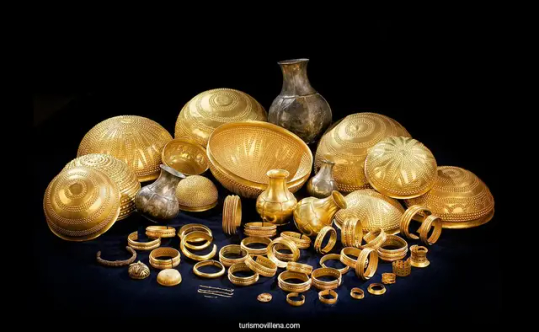

Meteorite Iron Discovered in 3,000-year-Old Bronze Age Gold Hoard

New research reveals that two Bronze Age artifacts from the Treasure of Villena contain iron from a meteor that hit a million years ago.

In the ’60s, researchers discovered a trove of Bronze Age treasure in Villena, Spain. While most of the stunning bottles, bowls and bracelets are made of gold and silver, new research has revealed that some of them were forged from another material: iron from a meteor that struck Earth a million years ago.

According to a recent study published in the journal Trabajos de Prehistoria, researchers conducted tests on two of the artifacts—a bracelet and a hollow decorative sphere—made between 1400 and 1200 B.C.E.

The trove’s materials have long mystified researchers. After finding it on the Iberian Peninsula in 1963, archaeologist José María Soler García noted the presence of a “dark leaden metal” among the gold, per El País’ Vicente G. Olaya. The metal was “shiny in some areas, and covered with a ferrous-looking oxide that is mostly cracked.”

To determine the iron’s origins, researchers used mass spectrometry, a technique that measures a molecule’s mass-to-charge ratio. As Live Science’s Jennifer Nalewicki reports, this analysis revealed that the iron’s nickel composition resembles that of meteoritic iron. These items are the first artifacts made of meteoritic iron ever found in the Iberian Peninsula.

“Iron was as valuable as gold or silver, and in this case [it was] used for ornaments or decorative purposes,” study co-author Ignacio Montero Ruiz, a researcher at the Spanish National Research Council’s Institute of History, tells Smithsonian magazine.

The presence of such an “unusual raw material” suggests it was made by highly skilled metalworkers capable of “[developing] new technologies,” adds Montero Ruiz.

But iron is also quite different from more common materials such as copper, gold or silver. As Montero Ruiz says to Live Science, “People who started to work with meteoritic iron and later with terrestrial iron must [have had to] innovate.”

The study’s other co-authors are Salvador Rovira-Llorens of the National Archaeological Museum and Martina Renzi of the Diriyah Gate Development Authority. The trove is held by Villena’s Archaeological Museum, which says on its website that the 66 items are considered the “most important prehistoric treasure in Europe.” Still, the artifacts’ origins remain a mystery.

Montero Ruiz tells Smithsonian magazine that objects made from meteoritic iron are rare, and most known examples from this period are connected to eastern Mediterranean cultures. The treasure’s creators “probably had access to a fallen meteorite in the area that allowed them to discover the properties of this material and how to shape it,” he says.

Last year, research revealed that an arrowhead found in Switzerland was made from meteoritic iron. That artifact, however, dates to between 900 and 800 B.C.E.

Researchers also don’t know who owned the Villena treasure, though they think it would have belonged to a community rather than a single individual.

“These two pieces of iron had enormous value. For this reason, they were considered worthy of becoming part of this spectacular ensemble,” says Montero Ruiz, per El País. “Who manufactured them and where this material was obtained are still questions that remain to be answered.”

By Sonja Anderson.

#Meteorite Iron Discovered in 3000-year-Old Bronze Age Gold Hoard#Treasure of Villena#Bronze Age treasure#Bronze Age#gold#silver#ancient artifacts#history#history news#ancient history#archeology#ancient civilizations#ancient art

145 notes

·

View notes