#John julius Norwich

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

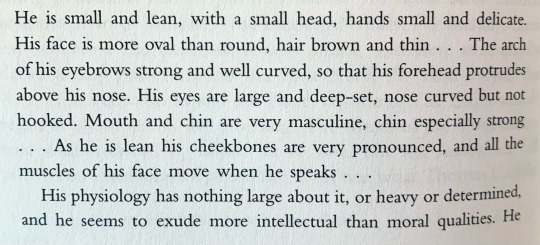

Description of Napoleon Bonaparte by the naturalist and explorer, Alexander von Humboldt:

Source: A History of France, by John Julius Norwich

#I love him calling his hands delicate 🥹#humboldt is another notable figure born in 1769#also did anyone else notice the part where he says his looks exuded 'more intellectual than moral qualities'#Alexander von Humboldt#humboldt#Napoleon#napoleon bonaparte#book#book pic#ref#quote#quotes#napoleonic#napoleonic era#frev#french revolution#interesting#France#history#John Julius Norwich

128 notes

·

View notes

Text

Theyre teen royalty. If 16th century Europe was Us Weekly they would always be on the cover.

🩷🩷🩷

I got Some Responses so I thought I'd post the drawing on the back cover 💅💅

#Charles v#Francis i#henry viii#suleiman the magnificent#16th century#History art#Mean girls#Yes this was VERY much based on that promo image of the Plastics whispering!!!#Four princes#John julius Norwich#Contemplated being weird in my own tags for the 5372772th time in a row before remembering im op and i can do whatever i want#Ch*rles is really such a poor little squeak squeak like look at him he is so f**ked up compared to everyone else ❤️#And it's like yeah in part ig i took special care to f**k him up but have u all SEEN the portraits i love him sm

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Christmas post from a Christmas video .

𝔐𝔢𝔯𝔯𝔶 ℭ𝔥𝔯𝔦𝔰𝔱𝔪𝔞𝔰 ❆⋆꙳•☃︎⋆꙳•✩⋆꙳•❅

#James Wilby#Youtube Stuff#Christmas#Will you look at that shelf#John Julius Norwich#The Twelve Days Of Christmas#I wish there was more material like this#A Christmas Post

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

A HISTORY OF VENICE by John Julius Norwich

RELEASE DATE: April 29, 1982

Published in Britain in two volumes, this massive but modest tome claims only to be ""a straightforward record of the main political events of Venetian history, for the general, non-academic reader""--and that's all it is. Aside from the occasional appreciation of a major building, you won't find cultural textures here. Also, as Norwich himself admits, you won't find--with a few exceptions--personalities. What you will find, however, is chattily readable prose, a dry sense of humor (""Eunuchs, as everybody knows, are dangerous people to cross""), and the author's engagingly qualified admiration for the Venetians--their unflagging self-interest, their state-imposed discipline, their secular, non-intellectual activism, their flexible ability to live more or less under a constitution for centuries. Here, then, is Venice from 5th-century beginnings as a refuge from barbarians to a loose, autonomous association of island communities under the Byzantine Empire circa 800 (her ""very submission"" assured independence and greatness); from a trade-centered Republic, fighting wars and pirates, to the builders (circa 1150) of an overseas empire (with a boost from the plundering Fourth Crusade) and a world-power circa 1300; from a Machiavellian peak of war/trade/diplomacy to, after Vasco da Gama (""Overnight, Venice had become a backwater""), a steady decline--with external entanglements and internal ""sickness."" Here, too, are the 100-some doges, the ups and downs of the elitist oligarchy and the Council of Ten; the problems with Popes (Julius II is perhaps the strongest character in the book); the role of the condottieri; the pros and cons re Venice as a police state. (Norwich, dearly something of an elitist himself, argues the relative freedoms and huge benefits of Venice's system.) And here, too, is conspiracy after conspiracy, war after war, a few floods, the Black Death, and the acquisition of a patron saint (""History records no more shameless example of body-snatching""). Most Venice-lovers, of course, will miss the esthetic cross-references. Serious history lovers will look vainly for deep, broad analysis. But, for those who share Norwich's more narrow enthusiasms: a lucid, companionable pageant.

1 note

·

View note

Text

TUDOR WEEK 2023: Day 1: Favourite Tudor Rivalry

Henry VIII of England, Charles V, Francis I of France

'Despite appearances, [Henry VIII] had never really taken to Francis—who offered, apart from anything else, too much serious competition. For Charles, on the other hand—who was still only twenty—he felt a genuine affection. After his visit to England the young man had written a letter thanking him and Catherine warmly for their hospitality, and in particular for the advice Henry had given him “like a good father when we were at Cantorberi”; and it may well be that the King, who was, after all, already his uncle, did feel in some degree paternal—or at least protective—towards him. What seems abundantly clear is that Charles endeared himself not only to Henry but to all who were with him, in a way that Francis, with all his swagger, had completely failed to do.' (x)

#tudorweek2023#dailytudors#henry viii#francis i#charles v#historyedit#perioddramaedit#the tudors#historian: john julius norwich#my first tudor week!!#**

116 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you have a recommended intro to / overview of Byzantine history?

not really. I got into it through the History of Byzantium podcast, which is a great resource but a terrible overview--it's very granular and I think it's still working though the crusades. Anthony Kaldellis just published a thousand-page narrative history, which I haven't finished but seems promising--he's a good communicator and his information is up to date--and Reddit seems to like Brownworth's book Lost to the West. John Julius Norwich's trilogy is apparently a great read, but lacks academic depth, which might be a good thing.

alternately, just click around here for a while. https://pbe.kcl.ac.uk/data/index.htm

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nightbane by Alex Aster opens with a quote from Cato, A Tragedy (1713) by Joseph Addison: “My bane and antidote are both before me.” Very important. Very cinematic.

Quotes can rarely, if ever, be taken out of context without any loss of meaning. So I have a personal policy to research the origins of whatever quote an author opens their book with. After all, a good quote should provide important framing or context for the book you’re about to read.

To summarize a very fascinating Wikipedia article: Cato, a Tragedy is an Enlightenment era play about Cato the Younger’s last days and his opposition to the reign of Julius Caesar. Cato was an icon of republicanism and, fittingly, the play deals with themes of “individual liberty versus government tyranny, republicanism versus monarchism, logic versus emotion, and Cato's personal struggle to hold to his beliefs in the face of death.”

Nowadays, the play is obscure. Modern productions of the play are rare, if ever staged. The text is also not included in most academic curriculum. Yet, Addison’s work seems to have been highly inspirational for America’s Founding Fathers. According to Wikipedia, quotes like “give me liberty or give me death” are theorized to be references to Addison’s play that the founding fathers assumed their audience would understand. George Washington even attended a production of it while in Valley Forge in 1778.

With its considerable influence on the founding of this country, it’s mind-boggling to me that this play is not only not taught in school, but is largely forgotten. I even asked my father, who is almost 70 and is a giant history buff, if he knew anything about this play in the vain hope that maybe some previous generation learned about it. But, no; even he had no idea what it was until I told him.

My bane and antidote are both before me comes from a soliloquy from act 5, scene 1. In it, Cato contemplates the merits of committing suicide. The bane and antidote is a sword he places his hand on and a copy of Plato’s Immortality of the Soul. He does not want to kill himself. How could anyone? But if he does not die now, he will have to live in a world made for Caesar. But Plato’s writings provide reason to the universe, which gives him comfort: “the stars shall fade away, the sun himself / Grow dim with age, and Nature sink in years; / But thou shalt flourish in immortal youth, Unhurt amid the war of elements, / The wrecks of matter, and the crush of worlds!”

There’s something undeniably fascinating about pieces of art that were highly influential during a period of history that have been lost to the passage of time now. Cato, a Tragedy is a cornerstone in American history, yet that did not save it from being a victim of obscurity. It failed to flourish in immortal youth.

Joseph Addison is best remembered as an essayist. His simple prose style was credited by John Julius Norwich as the marked end of the conventional, classical images of the 17th century. You can hardly believe it with the ease of poetry in Cato’s words.

What does this have to do with Nightbane?

Absolutely nothing. I am ninety-five percent certain that Aster found this quote on an enemies-to-lovers moodboard and declared it good enough! Sure, the quote has nothing to do with romance, but hey! Who would go through the effort to research the original context?

I spent so much time waxing poetry about Cato first because it's a funny bit; but mostly because it’s at least interesting. There’s nothing to say about Nightbane except that it’s bad. But you already knew that. That’s why you and everyone else in my life wanted me to read this book. It has to be bad to warrant any real attention.

Hell, even I wanted to read this book because it’s bad. Aster’s books are my guilty pleasure, largely because she sucks. Aster writes like she has never written anything before and is quickly realizing that it’s not that easy. When I read Lightlark and Nightbane, I feel like I am thirteen years old and writing my first story all over again. It brings me joy and comfort in a way that’s completely unmarred by irony.

That’s why I can almost forgive Nightbane for all the times the story goes out of its way to respond or correct a criticism from the first book. Aster definitely reads the comments, and it’s comical all the lengths she goes through to retcon bad ideas or retroactively add lore. It reminds me not only of how I wrote when I was a pre-teen, but how I write now with my way too long, just publish the first draft it’s fine, writing project.

One of the somewhat interesting ideas Aster introduces is a plot line about the ethics of having your peasantry’s lives literally tied to their monarchs and Isla’s budding admiration for democracy. Of course, she only brings either up because these were among her critics’ common talking points. It’s obvious she has no real desire to explore either idea for all it’s worth.

The democracy plotline ends with a big slap to the face to Cato, A Tragedy’s legacy. Isla promises to make the Starling kingdom a democracy in the future. Why? She personally doesn’t want to be a ruler. She has no problem with the idea of the monarchy and has no real passion for self-determinism. She just doesn’t want to have any responsibility. It’s too much work.

Plus, she only wants to make the Starlings a democracy. Not the Wildings. She may hate having any form of responsibility, but she’s not inclined to unseat herself from power. She can still be the Wildling’s shitty ruler. No democracy for them. Sorry. It’s so blatantly hypocritical that it turns comical, and I fall a little more in love with the absurdity of Aster’s storytelling.

While there are a lot of flaws I can forgive, I can’t forgive when the plot “goes through the motions.” Aster clearly wanted to include scenes where Isla and Grimshaw (I still refuse to call him Grim) recite bog-standard dialogue and recreate tropey romantic moments. The lead up to these scenes are vaguely, choppy, and inconsequential. The why does not matter; only these scenes do.

Except when these scenes happen, they are so generic that your eyes skim over them. Isla and Grim already do not feel like real people. I can hardly call them characters, or even concepts. To call them shadows suggests there is some kind of substance they spring from. I can’t even think of a good metaphor to describe them.

They are nothing. The plot is nothing. The prose is nothing. There is nothing worth chewing on. It’s not even worth composing a long rant about it.

It’s easy-bordering-pathetic to dissect a book everyone knows is bad, especially when your only purpose is to explain why it’s bad. Where is the critical thought? What effort are you actually putting into your analysis when everyone already agrees with your arguments? I will always prefer a critic who goes after works that are genuinely popular and well-liked. If you want to win an argument then, you have to work for it.

Yet, I’m still here doing this. You’re still here reading it. Ultimately, we’re all victims to the smug pleasure of believing that we are not capable of producing trash like this. Obviously, we are all secretly the world’s greatest artistes. We are the next Great American Novelist. None of us are capable of writing anything thoughtless, absurd, or shallow. We are infallible, unlike the sinner Alex Aster.

So, yeah. Bad book. Really wish someone will let me read a good one soon.

--

Nightbane by Alex Aster

⭐/5 stars

--

Now that I have finished lording my moral superiority over all of you, here is a miscellaneous list of stupid shit that happened in Nightbane. Even I can’t resist kicking the dead horse:

Oro reveals that he is deeply traumatized from accidentally killing someone by turning them into gold. Isla proceeds to demand a gilded blade of grass as a romantic tribute. He gives it to her. It’s romantic.

Oro is rich, has a job, and a healthy group of friends, and is somehow still going to lose this love triangle. What bullshit.

After emphasizing how traumatic if was for the Skylings to lose their ability to fly, the narrative tries to convince you that the Skylings would choose not to fight a war where them refusing to fight will lead to them losing the ability to fly again.

This is so stupid that when there’s a debate about it, Aster provides no examples as to why they shouldn’t fight; she just states she happens.

So much of the story is just told-- isla’s feelings and motivations, the lore, character relationships: it’s all just told to us.

Isla is confronted with having to fix the social issues of both the Wildlings and Starlings; instead of solving them herself and learning something new, an extremely competent lesbian volunteers to fix everything for her.

One of said problems is that Wildings, who have plant-based magic, do not know how to grow crops.

Wildings have also never cooked the hearts they have been eating. Like, ever? Not once in five hundred years?

Isla shows prejudice towards the Vinderland because they are cannibals.

It’s increasingly unclear how the immortality rule works about the nobility

New lore reveals that the Nightshade have so many extra cool magic abilities because of lore reasons, and not because Aster likes them the best.

There’s a rebel group that got fed up with the rulers not fixing the curse; they also managed to make no progress in solving the very easy mystery in less than 500 years.

During flashback time, Grimshaw saves Isla no less than 7 times

There is a night market on Nightshade that has to take place during the day time, due to the curse. They still call it a night market.

There are multiple Nightshade events where the dress code is on a scale from”instagram baddie” to actually just naked. Isla’s clothes are described in detail, but not Grimshaw. I can only assume that his dick and balls were out every time.

Grimshaw seems to also be the only unfun prude on an island of hedonistic extroverts.

There is a sword that had been stolen no less than three times by different thieves.

New starstick lore clarifies it’s a device (not a wand!), and that Isla can’t use it to go anywhere she hasn’t been before; this renders her entire backstory impossible.

Instead of disengaging a bunch of traps, Grimshaw decides to Looney Tunes his ass and trigger each one by one.

There’s so much on and off screen cannibalism and flaying that neither are cool anymore. Sorry! We have to find new imagery for our toxic situationships.

The plot structure being a jump back and forth between the past and present made me question my own ability to write a storyline like that lmao

Isla and Grimshaw have been married the whole time, in a plot twist shoved in at the last second with very little thought put into it.

Isla should divorce his ass. I hope Lightlark is a no-fault state. If not, she luckily has a fuckton of faults to bring up.

#extremely tempted to read her middle grade books for comparison#ugh and I still have Skyshade to read#i just want to read a good book already!!!!#me rambling#me reading#bookish#books#booklr#books and reading#bookblr#lightlark#nightshade#alex aster

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

Women’s History Meme || Empresses (5/5) ↬ Zoe Porphyrogénnētē (c. 978 – 1050)

When Michael V met his fate on Tuesday evening, 20 April 1042, the Empress Theodora was still in St Sophia. She had by now been there for well over twenty-four hours, steadfastly refusing to proceed to the Palace until she received word from her sister. Only the following morning did Zoe, swallowing her pride, send the long-awaited invitation. On Theodora's arrival, before a large concourse of nobles and senators, the two old ladies marked their reconciliation with a somewhat chilly embrace and settled down, improbably enough, to govern the Roman Empire. All members of the former Emperor's family, together with a few of his most enthusiastic supporters, were banished; but the vast majority of those in senior positions, both civil and military, were confirmed in office. From the outset Zoe, as the elder of the two, was accorded precedence. When they sat in state, her throne was placed slightly in advance of that of Theodora, who had always been of a more retiring disposition and who seemed perfectly content with her inferior status. Psellus gives us a lively description of the pair: Zoe was the quicker to understand ideas, but the slower to give them utterance. With Theodora it was just the reverse: she concealed her inmost thoughts, but once she had embarked on a conversation she would chatter away with an informed and lively tongue. Zoe was a woman of passionate interests, prepared with equal enthusiasm for life or death. In this she reminded me of the waves of the sea, now lifting a vessel on high, now plunging it down again. Such extremes were not to be found in Theodora: she had a calm disposition - one might almost say a dull one. Zoe was prodigal, the sort of woman who could dispose of a whole ocean of gold dust in a single day; the other counted her coins when she gave away money, partly no doubt because all her life her limited resources had prevented her from any reckless spending, but partly also because she was naturally more self-controlled In personal appearance there was a still greater divergence. The elder, though not particularly tall, was distinctly plump. She had large eyes set wide apart, with imposing eyebrows. Her nose was inclined to be aquiline, though not overmuch. She still had golden hair, and her whole body shone with the whiteness of her skin. There were few signs of age in her appearance … there were no wrinkles, her skin being everywhere smooth and taut. Theodora was taller and thinner. Her head was disproportionately small. She was, as I have said, readier with her tongue than Zoe, and quicker in her movements. There was nothing stem in her glance: on the contrary she was cheerful and smiling, eager to find any opportunity for talk. — Byzantium: The Apogee by John Julius Norwich

#women's history meme#zoe porphyrogenita#byzantine history#medieval#greek history#asian history#european history#women's history#history#nanshe's graphics

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sicily: An Island at the Crossroads of History. Chapters 1-3

This book was written by British historian John Julius Norwich. I will attempt to cover the chapters one at a time, other than this first installment, since the chapters are smaller.

1 Greeks The first true culture we encounter on Sicily is Mycenaean, from around 1600BC. Around 1400 BC, Sicily was absorbed into the Mediterranean trade routes. The Mycenaeans disappeared around 1200BC, no one knows why. There were some tribes that lived on the island: Sicans, Sicels, Elymians, but we know little of them.

Sicily's earliest historical period people were Greeks who had come over to colonize areas of the eastern and southern coast. The first Greek-Sicilian settlement was Gela around 688BC. The next centuries saw the cities build up through Greek art, philosophy, and civilization. But we must recognize that "Greece" was something like the way we consider "Arab" today. It was a concept more than a particular nationality.

The Carthaginians had a footing on the western edge of the island at Marsala and Trapani. Carthage was originally a Phoenician outpost. The Phoenicians were canaanites from the Old Testament. They were a seafaring people, who had established trading outposts all over the Mediterranean. Carthage, modern day Tunis, was one of those cities, which had gained independence in 650BC.

There were occasional clashes between the Greek cities with appeals to Carthage to intervene by whatever city saw itself as undermanned in the looming fights.

Around 400, an agreement was made between Syracuse and Carthage whereby Carthage would limit itself to the western portion of the island.

2 Carthaginians For the next hundred years, skirmishes continued between Greek Sicily and Carthaginian Sicily, but in 272, Rome captured Tarentum and effectively claimed control over the entire Italian peninsula. During the 200's Sicily was going to have to make a choice between Rome and Carthage.

There were a series of 3 Punic wars (wars between Rome and Carthage) fought between 264 and 146BC. During that time, Sicily became a Roman territory.

3 Roman, Barbarians, Byzantines, and Arabs. Roman By 241BC Sicily was essentially run by the Romans. The Greek speakers were still there, but Greece was in no position to influence much on the Island. Carthage was a power during the first part of the 200's, and indeed, Hannibal was causing all kinds of trouble on the Italian peninsula itself but, Carthage was not the influence on Sicily.

The Romans never considered Sicily more than a province... allies... but they were not considered citizens. The important fact was that Sicilians spoke Greek, not Latin. We know relatively little about the events on the island. But here are some 'highlights'... or lowlights... you can decide....

There were several slave revolts on the island. The slave population dangerously outnumbered the free, and they were terribly abused. (Good combo for an uprising.) The first slave war broke out around 139BC, Rome was slow to react since it didn't take the idea of slaves too seriously, and consequently wasn't put down until 132BC, seven years later.

A second slave war broke out in 104BC, but this time Rome was quicker to respond. The second war was ended in 100BC after an epic effort by the slaves.

Gaius Verrus was governor/criminal from 80-70BC, which saw the island suffer terribly under his pillaging. He was excoriated in the Roman Senate by Cicero, who took the case on himself, and Verrus, who saw the writing on the wall, packed up his stuff and amscrayed to Marseille before the trial ended and he was put under arrest.

The final transition of Rome from Republic to Empire left Sicily with a much larger Roman element than before. By decree, all mainland Italians had gained Roman citizenship, but this was not true for Sicily. 6 cities however were included, and their citizens were given Roman citizenship: Taormina, Catania, Syracuse, Tindari, Termini, and Palermo.

Sicily had become one of the most important sources of grain for the Roman empire.

Unfortunately, we know little of Sicilian history for the first 500 years of the Christian era. It seems to have prospered, as evidenced by the quality of the buildings that have survived from that period.

They were largely unconcerned by Constantine's decision to move the capital of the Empire to Constantinople in 330. They were largely unconcerned with the decision to move the western capital to Ravenna in 395.

Constantine's main contribution was the official status of Christianity, which spread rapidly across the island, replacing the old Greek religion.

By the 400's there also seems to have been a large influx of Jewish immigration.

Barbarian By the late 400s, the barbarians had arrived. Who you callin' barbarian?? I'm sure the barbarians didn't think they themselves were so deficient... after all, who just kicked who's @$$ on Rome's home field? The three "barbarian" tribes of interest to us are the Goths, Huns, and Vandals. Only the Vandals showed any interest in Sicily.

The Goths, under Alaric, had besieged Rome as early as 408.

The Huns attacked Italy by 452, but didn't get to Sicily.

The Vandals however, had gone across Gaul (france), settled in Spain, then crossed into North Africa, attacked Carthage and raided Sicily.

The Roman empire, these days, is considered to have finally succumbed in 476.

Byzantine In 533, Emperor Justinian launched a campaign to recover the western empire. His general, Belisarius, arrived in Sicily in 535, where he was universally welcomed by the Greek-speaking population. Sicily was once again an imperial province, ruled by a Byzantine governor, hooray! By the middle of the 600's, the Greeks were concerned for their western provinces because of the surge of Islam. Emperor Constans II decided that a Roman empire without a Rome was kind of pointless, so he wanted to shift his capital westward, but after actually seeing the dump that Latin Rome had become, he decided in 663 on the more familiar Greek atmosphere of Syracuse. This should be good for the Greek speaking Sicilians, right? The next 5 years were a nightmare for the Sicilians, due to the extortions and heavy taxes laid on them. This may have gone on for God knows how long, except in 668 Constans was assassinated. His son picked up again and moved back to Constantinople.

Arab Sicily had been left in peace for some time, but Arab raids were continuing. They now controlled the entire north African coast, and in 827, they invaded Sicily when a local governor, Euphemius, was ousted for an affair with a nun. He responded by proclaiming himself Emperor and then, realizing he didn't have enough muscle to actually make that happen, invited the Arabs to come help. The Arabs came, shoved Euphemius out of the way, and started a slow takeover for themselves.

Palermo fell in 830; Messina fell in 843; Syracuse in 878. By that time, Sicily was effectively an Emirate of the Muslim world.

The Muslim conquest made Sicily a major player in Mediterranean commerce. The Arabs introduced terracing and siphon aqueducts, they introduced cotton and papyrus, melon and pistachio, citrus and date palm and sugarcane. Muslim, Jewish, and Christians all thronged the bazaars of Palermo.

But stability was not part of Arab rule, and there were always tensions between the various factions.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Backlog Busting Reading Challenge!

Had a productive week this week and three books were finished!

The Time Traveller's Guide to Restoration Britain by Ian Mortimer. FINISHED. Really enjoyed this one. For some reason, the period descriptions here felt more vivid compared to the other books in the series. Great detail as always.

The Great Cities in History by John Julius Norwich (editor). FINISHED. This was a quick and easy read as each chapter about the cities was only 3-6 pages. That said I was a bit disappointed. The breadth was incredible but the depth shallow and there was no sense of "world history" in terms of linking anything together or analysis. Still, I will be combing through the bibliography for choice picks, and it introduced me to cities/cultures I knew nothing about before.

A Crown of Swords by Robert Jordan (Wheel of Time #7). FINISHED. I can sense the series is starting to drag a bit here - it felt particularly egregious that the weather plotline resolution was put off for yet another book. I'm still enjoying the series though and especially the Rand/Min interactions in this book, which were adorable and actually felt like a normal relationship.

Upcoming books!

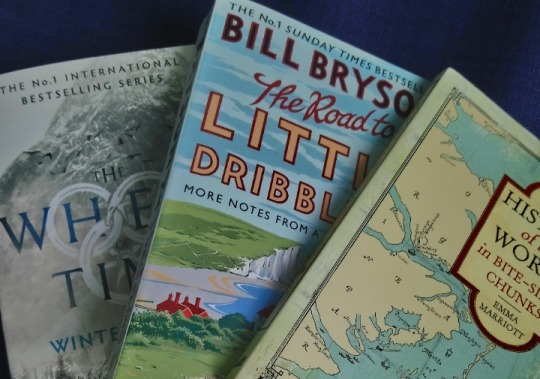

A History of the World in Bite-Sized Chunks by Emma Marriott. Sticking to the world history and "rummaging through the bibliography for good finds" theme... I'm also trying to get through some of the shorter books on my list - this one is under 200 pages.

The Road to Little Dribbling by Bill Bryson. I've read lots of Bryson's works and really enjoy his ability to convey his enthusiasm about learning new things and his sense of humour, so I'm sure I will enjoy this one too.

Winter's Heart by Robert Jordan (Wheel of Time #9). Not sure if I will get round to this one as I haven't gotten that far into Path of Daggers yet, but Path of Daggers is very short by WoT standards, there's a fairly good chance.

96 books remaining!

#book backlog busting reading challenge#bbb challenge#books#history books#reading#reading challenge#reading backlog

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Books I Have Read in the Past Six Months and Enjoyed

(Links to bookshop.org, not currently affiliate links)

Absolute Monarchs: A History of the Papacy by John Julius Norwich - Quite fun and informative. By necessity, he has to breeze over some of the popes because either a) it's so far back, we know jack and shit about them, or b) they're boring, and we need space to talk about Renaissance popes behaving badly.

(The Renaissance Catholic Church behaving badly is currently one of my major interests.)

Paladin's Grace/Paladin's Strength/Paladin's Hope by T. Kingfisher - I love Ursula Vernon's characters and worldbuilding, and it's delightful to return to the world of the Temple of the White Rat. She also has some of my favorite takes on paladins in fiction.

The Cardinal's Hat and Conclave 1559 by Mary Hollingsworth - Remember how I said the Renaissance Catholic Church behaving badly is one of my major interests? Allow me to introduce you to Ippolitto II d'Este, grandson of Pope Alexander VI (aka Rodrigo Borgia).

Not sure why The Cardinal's Hat isn't on bookshop.org, but you can find it elsewhere. It covers Ippolitto's early career up until shortly after he received his cardinal's hat. Conclave 1559 covers a papal election Ippolitto was a major figure in that went on for months. Both are very good reads.

Among Thieves by Douglas Hulick - Also not listed on bookshop.org for some reason. I kriffing love weird world-building, and our protagonists stumbling headlong into problems and making problems for other people while they try to figure out what's going on, and this book has both.

The Cardinal's Blades by Pierre Pevel (omnibus with the whole trilogy; caveat: I haven't read the whole trilogy yet, just the first book) - Dragons vs. Cardinal Richelieu. We focus far, far more on the people he's using to fight the dragons than the cardinal himself, which allows the writer to get in some amazing twists. None of them are forced, they just rely on us not being told everything because the character whose pov we're in hasn't been told everything.

The book does hop through multiple points-of-view, so if you're bad at keeping track of names, you may not enjoy this as much as you might otherwise.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

April 2024 Reading

Neve, cane, piede- Claudio Morandini (2016) Story of an old mountain man/hermit, Adelmo Farandola, who hates being around others. He lives alone high up in an alpine valley, when an old dog makes his way to him. At first he tries to chase the dog off, but the dog stays and they develop a companionship. Through a tough winter, the man reminisces to the dog about his abusive childhood, hiding in the mountains to avoid the wartime conflicts, and his learning to deal with hunger, thirst, and sleep deprivation in order to stay hidden.

But as Adelmo has gotten older, his memory is slipping and his thoughts, while locked in his cabin for the long winter months, are becoming more disjointed. He also struggles with sounds he hears from the movement of the snow and ice. Avalanches are an ever-present, and real, concern.

Adelmo and the dog converse. The dog acts as a kind of 'second opinion' where alternative ideas are sounded out. The dog's opinion is the device for the old man's inner dialogue. Clearly, Adelmo's memory is slipping badly as the book moves along. In the spring, after they make their first trip down the mountain to restock on food, they discover a foot sticking out of the snow.

Adelmo figures there is no rush to do anything about it since the man is dead already. The dog suggests maybe they should tell someone in the village about it. The man puts it off. Later he does attempt to tell the shop owner in the town, but she doesn't realize he is serious. At some point later, Adelmo begins to recall perhaps having shot the man some time earlier, and his body had come down in the landslide. He decides he will bury/hide the body in an abandoned mine. Adelmo then decides to lay down with the cadaver and has a long conversation with it too.

Sicily- An Island at the Crossroads of History- John Julius Norwich (2015)

A history of Sicily. Sicily's history goes back to around 700BC. The island was colonized by the Greeks in the east and the Carthaginians in the west. After the Punic Wars the Romans had effective control over the island. When the Roman empire fell in 476AD, the island was left largely to itself until the Byzantine empire invaded in 535 and took back the island for itself until around the mid 800s. The Arabs were invited over, then conquered the island for themselves and Sicily became an Emirate until the mid 1000s. When the Normans came, Sicily entered a golden age of multi-cultural prosperity that was the wonder of Europe. But when the island was turned over to the Hohenstaufen (German) dynasty through marriage around 1200, the island ceased to be an independent kingdom.

From that time on, the history of Sicily is told in the history of French, Spanish, and Austrian decisions made outside of Sicily. The island passed from one nation to the other with little to no regard for what the Sicilians themselves wanted.

Relegated to provincial status, treated as a place to be exploited, Sicilians learned to trust no one, and look out for themselves and themselves only.

As a Sicilian/American, it's heartbreaking to read. I loved learning more about the history of Sicily, but it's tough to take at times.

Thus Spake Zarathustra- Friedrich Nietzsche (1883-5)

Reading the prologue, it's not hard to see the philosophical connection between Nietzsche and some of the more heinous political systems that arose in the early to mid-twentieth century. I know Nietzsche fans will say that they didn't properly understand him, which may be true. I'm not saying that the Nazi's thought: Nietzsche's the thing... how can implement a system that best encapsulates his philosophy?

But looking at the philosophical ideas floating around at the time: Darwin was relatively new and people were still wrapping their heads around survival of the fittest, and the evolutionary idea that selection will find a way to get genes into the future.

Nietzsche talks about the coming superman; the fact that we won't be the superman, but we may be the direct ancestor of the superman. He speaks of the glory of manliness and being a warrior. These things tie in nicely with the idea of how we best bring about this new superman, who will usher in a new era of human proficiency.

Fascism then saw themselves as constructing a society built on such new men. They preached the need or manly sacrifice, and the need for war to toughen men's bodies and keep them from getting soft. This new society would bring about new men, which would be better than the effeminate populace getting too soft on comforts, and unwilling to sacrifice for a greater good.

I find it fascinating to read the book more for that sense of grasping the kinds of ideas that were capturing men's attention at the time. Fascism didn't just spring up out of nowhere with the idea: hey let's kill a bunch of people! It was a political response to people's fears and hopes of the times, and it must have seemed a plausible response to what people saw as the failures of the systems in place at the time.

Nietzsche hated Christianity and saw its doctrines as effeminizing men and turning them into docile sheep with no creative ideas. He preached strength and virtue, but virtue in more of the old Roman understanding than the Christian. He thought equality was stupid and contra-nature. He criticizes modern (late 1800s for him) culture, but sees Christianity at fault for most of the weaknesses of that culture.

One of the important concepts of the book is 'will to power'. But what exactly this means is hard to pin down. Maybe 'self-determination' would be a good word. Nietzsche writes that all creatures are obeying creatures. There are two sub-categories: those that command themselves and those that are commanded by others. Commanding oneself however is difficult and carries responsibility with it, so it is often avoided. Those then that are stronger will command others. But it is in the nature of life to continually surpass itself. I think this is saying that the strong will naturally rise up and rule in power. Life inherently has the will to power, and it is the weakness of modern man that he has chosen to submit himself and be commanded.

In the third part of the book, Zarathustra, defines existence as an eternal recurrence.

The Return of the Native- Thomas Hardy (1878)

Hardy's novels, and I've now read five of them, tend to start slow, but by the time I'm halfway through, I can't put them down. This one concerns mainly two couples, and a few secondary characters.

Thomasin Yeobright is a pretty young girl that lives on the Heath in England. She is engaged to be married to Damon Wildeve, known in the parts as a bit of a player. The marriage ceremony hits a snag and is unable to go through. We find out that Wildeve is perhaps more in love with another beauty on the Heath, Eustacia Vye. He had been involved with her, but when he expressed interest in Thomasin, Eustacia broke things off. Now they were meeting again, mostly because Eustacia sees him as a way out of the Heath. Wildeve and Eustacia both long to leave, while Thomasin grew up on the Heath and can't imagine leaving.

Eustacia's interest is pulled immediately away from Wildeve on the arrival of Thomasin's cousin, Clym, just arrived from a successful business stint in Paris. Eustacia sees a way out of the heath in Clym, and shortly after, they are married.

But Clym has no interest in leaving the Heath. He explains this to Eustacia, but at heart she thought she could bend him towards her will and change his mind. She grows morose when he insists on staying.

Meanwhile, Wildeve comes into some fortune and Eustacia starts to reconsider her path: perhaps Wildeve would become the way out, but she feels she can't just leave her husband.

Without giving away the ending, the story has to do with thwarted desires and frustrations, and the expectations of society versus personal desires.

Agnes Grey- Anne Bronte (1847)

The novel really serves as an exposé for the treatment of governesses at the time. The main character goes to work for two families as a governess, where she is entrusted with raising children, but given no tools to succeed. In fact, both families raise their children to be dismissive and superior to those "beneath them". The governess is charged with teaching the children manners as well as schooling them, but they are allowed to rule over her. It is their wishes that must be followed, not hers. Yet she is blamed for the resultant problems.

Cranford- Elizabeth Gaskell (1853)

A book with no discernable plot, about a group of ladies in the fictional town of Cranford. These ladies have sticks way up their butts about class, and they're way overconcerned about all the ways in which they can show themselves better to particular people. This is the main concern of their lives: finely dissecting the layers of society and then demonstrating to themselves that they are better than those "below them" in the execution of just about everything they do. Like I said... sticks WAY up their butts.

There are occasionally funny lines, for example: "Mrs. Jamieson, meanwhile, was absorbed in wonder why Mr. Mulliner did not bring the tea; and at length the wonder oozed out of her mouth."

As the book progresses, there is a severe financial setback for one of the characters and her reduced means force everyone to reconsider their evaluations of caste and value.

Manon Lescaut- Abbe Prevost (1731)

The story of the young Chevalier des Grieux, who meets and immediately falls in love with the then 15 year-old Manon Lescaut. His unrestrained passion, and Manon's fickle attitude and desire for pleasures, lead him to repeatedly sink into troubles. Forced out of France, they wind up in New Orleans where Manon dies. The story is narrated by des Grieux, and I'm not sure I've found myself thinking: what are you DOING!? so much since the story of Pinocchio. It is both a love story and perhaps a cautionary tale about unrestrained passions.

I will say though, this story had me engaged from page one. I read nearly the entire novel in a day.

Steppenwolf- Hermann Hesse (1927)

"For of all things, what I hated, abhorred and cursed most intensely was just this contentment, this will-being, the well-groomed optimism of the bourgeois, this lush, fertile breeding ground of all that is mediocre, normal, average."

The steppenwolf is the wild wolf of the steppes. Hesse considered that this was an alter-ego that lived alongside the civilized man that the world must be presented with. The wild wolf, he explains, has strayed into civilized territory, and can no longer find its home or the food it likes to eat.

During the story, Harry, the central character, is handed a tract called the steppenwolf, that describes his life, and tells him he is wrong: his personality isn't two mutually exclusive characters, it is a thousand, or more, competing characters. He then meets the beautiful Hermione, a counterpart to his life, who further breaks down his analysis, and sets to build up areas of his life that are deficient- but solely for the purpose of showing him that even being proficient in these areas is still nothing but unfulfilling.

The back cover contains a quote from a NY Times review: "The gripping and fascinating story of disease in a man's soul".

So much of the story is really dealing with meaning. They blame it on the mundane meaninglessness of middle class life. But I think it arises from abundance, and the concomitant depressing thought that if this is all there is, what's the point. Perhaps in times past, or even current times where life is subsistence, the general sense is "If only I were to have enough", then I could really be whole". And it's true that in modern, western societies, we have enough. Many people still think, "I still struggle a bit, so If only I were to have a little more, then I could really be whole."

But enough people, even more than a hundred years ago, had looked around at our prosperous modern western society, and thought, "wait... is this all there is?", and grew profoundly disappointed in it.

On the Road- Jack Kerouac (1957)

The version I got is called the "original scroll". It's basically the original autobiographical narrative he wrote, with all the true names. The names were changed for the published 1957 version.

There are no chapter or section breaks. Or even any 'paragraphs'. It is written as one gigantic stream-of-consciousness flow.

The book is set in the period of 1947-49. Jack Kerouac and friends, particularly Neal Cassady, hit the road moving from NY to California and back, then do it again... then finally down to Mexico City where the book abruptly ends.

They take 'carefree' to the limit of careless, then to criminal and insane. By 250 pages in to this 300 page book, I was so sick of these morons antics, that I was hoping they'd just get locked up. In search of 'kicks', they left a trail of brokenness, and hurt wherever they went. Even their own friends were disavowing Jack and Neal by the end of it.

The Stranger- Albert Camus (1942)

A man kills another man senselessly, is put on trial, and is given the death penalty. Camus was an absurdist; which is a philosophy that proposed life has no purpose. It isn't that everything is "absurd" in the way we typically think of the word now. As the main character muses on his life and death, he sees no real point in either.

2001: A Space Odyssey- Arthur C. Clarke (1968)

This book was a product of a collab with Stanley Kubrick. The story was made into a movie at the same time. Though only Clarke was credited as the author on the book. An unknown, but obviously alien, monolith is discovered on the moon. And a team is sent to one of Jupiter's moons to explore a second monolith, but things go off course when the onboard sentient computer, HAL9000, flips out. One survivor makes it to the monolith to discover it is a portal to other star systems. He is eventually led to the aliens, but we don't learn anything about them.

0 notes

Note

Where did those quotes in the art piece of yours you reblogged about Charles V being ugly and stupid actually come from?

I'm really curious about which academics said that

YAY im being recognised as a reliable source to come to for these things!!!11!

Moving on okurrrrr i //did// say academics in like massive inverted commas so 🤡🤡🤡 regular history book writers is more like but doesn't quite have a ring to it. Anyway here are your Sauces™ because i may throw words around but I don't make shit up!! *Taps head*

"A perfect twit, a cruel victim of spoiling and aristocratic inbreeding" - Eric Metaxas, Martin Luther

"He couldn't help being ugly", "Villainously ugly" - John Julius Norwich 🔫 WHAT'S GOOD CUNT!!!?!?!????!*, Four Princes

"Not quite put together.... Ungainly and frail-looking" - James Reston Jr, Defenders of the Faith

"Thin, sickly-looking and somewhat ugly" - Henry Kamen ((aka the only bitch on this list i respect)), Spain 1469-1714: A Society of Conflict

*((if you all KNEW how much i hate JJN. it's Unreal. Had semen scumbag Montefiore from soviet history's good review on the very back of this book too they can suck each others and rot together imo.))

Have a sketch i never posted with it! And yes he was a skrunkly lad wasn't he!! If I can't *quite* say I love him then I can at least say I feel a deep sympathy really every time someone unironically dunks on what was otherwise an uncomfortable teenager. It just feels mean, ye know what i mean?

And then a deep fascination with his arc from that sopping wet rat to whatever the hell god complex delulu bullshit he became when he got older. Thoroughly insufferable. I'm obsessed.

#Half considered citing in Chicago or MLA as im currently programmed for my dissertation but.#It would take the life out of me sorry. Just cope with the authors and titles i prommy u are smart enough <3#charles v#asks#historical fanart#16th century#my art#history art#There are ofc more and i might make a part 2 but. We shall See. He is SO babygirl

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

I just learned that there were two rivals for a kingdom who set a date for a duel to settle the matter, but not a time of day.

Each of them showed up at a different time, didn't find the other, and declared themself the winner -according to the book*, they never met.

*The Middle Sea, by John Julius Norwich, pp 189-190

1 note

·

View note

Text

Absolute Monarchs: A History of the Papacy - J. J. Norwich

2,000 Years of Popes, Sacred and Profane

By Bill Keller

July 7, 2011

John Julius Norwich makes a point of saying in the introduction to his history of the popes that he is “no scholar” and that he is “an agnostic Protestant.” The first point means that while he will be scrupulous with his copious research, he feels no obligation to unearth new revelations or concoct revisionist theories. The second means that he has “no ax to grind.” In short, his only agenda is to tell us the story.

And he has plenty of story to tell. “Absolute Monarchs” sprawls across Europe and the Levant, over two millenniums, and with an impossibly immense cast: 265 popes (plus various usurpers and antipopes), feral hordes of Vandals, Huns and Visigoths, expansionist emperors, Byzantine intriguers, Borgias and Medicis, heretic zealots, conspiring clerics, bestial inquisitors and more. Norwich manages to organize this crowded stage and produce a rollicking narrative. He keeps things moving at nearly beach-read pace by being selective about where he lingers and by adopting the tone of an enthusiastic tour guide, expert but less than reverent.

A scholar or devout Roman Catholic would probably not have had so much fun, for example, with the tale of Pope Joan, the mid-ninth-century Englishwoman who, according to lore, disguised herself as a man, became pope and was caught out only when she gave birth. Although Norwich regards this as “one of the hoariest canards in papal history,” he cannot resist giving her a chapter of her own. It is a guilty pleasure, especially his deadpan pursuit of the story that the church, determined not to be fooled again, required subsequent papal candidates to sit on a chaise percée (pierced chair) and be groped from below by a junior cleric, who would shout to the multitude, “He has testicles!” Norwich tracks down just such a piece of furniture in the Vatican Museum, dutifully reports that it may have been an obstetric chair intended to symbolize Mother Church, but adds, “It cannot be gainsaid, on the other hand, that it is admirably designed for a diaconal grope; and it is only with considerable reluctance that one turns the idea aside.”

If you were raised Catholic, you may find it disconcerting to see an institution you were taught to think of as the repository of the faith so thoroughly deconsecrated. Norwich says little about theology and treats doctrinal disputes as matters of diplomacy. As he points out, this is in keeping with many of the popes themselves, “a surprising number of whom seem to have been far more interested in their own temporal power than in their spiritual well-being.” For most of their two millenniums, the popes were rulers of a large sectarian state, managers of a civil service, military strategists, occasionally battlefield generals, sometimes patrons of the arts and humanities, and, importantly, diplomats. They were indeed monarchs. (But not, it should be said, “absolute monarchs.” Whichever editor persuaded Norwich to change his British title, “The Popes: A History,” may have done the book a marketing favor but at the cost of accuracy: the popes’ power was invariably shared with or subordinated to emperors and kings of various stripes. In more recent times, the popes have had no civil power outside the 110 acres of Vatican City, no military at all, and even their moral authority has been flouted by legions of the faithful.)

Norwich, whose works of popular history include books on Venice and Byzantium, admires the popes who were effective statesmen and stewards, including Leo I, who protected Rome from the Huns; Benedict XIV, who kept the peace and instituted financial and liturgical reforms, allowing Rome to become the religious and cultural capital of Catholic Europe; and Leo XIII, who steered the Church into the industrial age. The popes who achieved greatness, however, were outnumbered by the corrupt, the inept, the venal, the lecherous, the ruthless, the mediocre and those who didn’t last long enough to make a mark.

Sinners, as any dramatist or newsman can tell you, are more entertaining than saints, and Norwich has much to work with. If you paid attention in high school, you know something of the Borgia popes, who are covered in a chapter succinctly called “The Monsters.” But they were not the first, the last or even the most colorful of the sacred scoundrels. The bishops who recently blamed the scourge of pedophile priests on the libertine culture of the 1960s should consult Norwich for evidence that clerical abuses are not a historical aberration.

Of the minor 15th-century Pope Paul II, to pick one from the ranks of the debauched, Norwich writes: “The pope’s sexual proclivities aroused a good deal of speculation. He seems to have had two weaknesses — for good-looking young men and for melons — though the contemporary rumor that he enjoyed watching the former being tortured while he gorged himself on the latter is surely unlikely.”

Sexual misconduct figures prominently in the history of the papacy (another chapter is entitled “Nicholas I and the Pornocracy”) but is hardly the only blot on the institution. Clement VII, the disastrous second Medici pope, oversaw “the worst sack of Rome since the barbarian invasions, the establishment in Germany of Protestantism as a separate religion and the definitive breakaway of the English church over Henry VIII’s divorce.” Paul IV “opened the most savage campaign in papal history against the Jews,” forcing them into ghettos and destroying synagogues. Gregory XIII spent the papacy into penury. Urban VIII imprisoned Galileo and banned all his works.

Most of the popes, being human, were complicated; the rogues had redeeming features, the capable leaders had defects. Innocent III was the greatest of the medieval popes, a man of galvanizing self-confidence who consolidated the Papal States. But he also initiated the Fourth Crusade, which led to the wild sacking of Constantinople, “the most unspeakable of the many outrages in the whole hideous history of the Crusades.” Sixtus IV sold indulgences and church offices “on a scale previously unparalleled,” made an 8-year-old boy the archbishop of Lisbon and began the horrors of the Spanish Inquisition. But he also commissioned the Sistine Chapel.

Even the Borgia pope Alexander VI, who by the time he bribed his way into office had fathered eight children by at least three women, is credited with keeping the imperiled papacy alive by capable administration and astute diplomacy, “however questionable his means of doing so.”

By the time we reach the 20th century, about 420 pages in, our expectations are not high. We get a disheartening chapter on Pius XI and Pius XII, whose fear of Communism (along with the church’s long streak of anti-Semitism) made them compliant enablers of Mussolini, Hitler and Franco. Pius XI, in Norwich’s view, redeemed himself by his belated but unflinching hostility to the Fascists and Nazis. But his indictment of Pius XII — who resisted every entreaty to speak out against mass murder, even as the trucks were transporting the Jews of Rome to Auschwitz — is compact, evenhanded and devastating. “It is painful to have to record,” Norwich concludes, “that, on the orders of his successor, the process of his canonization has already begun. Suffice it to say here that the current fashion for canonizing all popes on principle will, if continued, make a mockery of sainthood.”

Norwich devotes exactly one chapter to the popes of my lifetime — from the avuncular modernizer John XXIII, whom he plainly loves, to the austere Benedict, off to a “shaky start.” He credits the popular Polish pope, John Paul II — another candidate for sainthood — for his global diplomacy but faults his retrograde views on matters of sex and gender. Norwich’s conclusion may remind readers that he introduced himself as a Protestant agnostic, because whatever his views on God, his views on the papacy are clearly pro-reformation.

“It is now well over half a century since progressive Catholics have longed to see their church bring itself into the modern age,” he writes. “With the accession of every succeeding pontiff they have raised their hopes that some progress might be made on the leading issues of the day — on homosexuality, on contraception, on the ordination of women priests. And each time they have been disappointed.”

1 note

·

View note

Note

Hey do you have any book recs for Byzantine history in general or for people just starting to learn about it?

Hello – so sorry this took so long! I'm finishing up a research project and haven't had a chance to log into Tumblr. While I have always, and will always, love the Byzantines, my job dictates that my focus is on the Tudors, all the time, so I apologize if some of these aren't completely up to date. Nevertheless, I'm happy to provide clarification on any of my suggestions and would be open to answering any questions you might have.

Bear in mind that the history of the "Byzantine Empire" spans a thousand years, and encompasses varying periods that differ significantly. It would probably be beneficial to nail down which period you're interested in studying/learning more about and going from there (though for a comprehensive overview I recommend the Cambridge History or Byzantium by Cyril Mango, both of which I've cited below).

Also, I was really delighted by this question – thank you!

Books

Cambridge History of the Byzantine Empire (2009)

Byzantium: The Empire of New Rome by Cyril Mango

The Fall of Constantinople 1453 by Steven Runciman (though 1453 by Roger Crowley is also a great start)

Byzantium: The Early Centuries by John Julius Norwich (a good introduction, as is A Short History of Byzantium)

Women in Purple: Rulers of Medieval Byzantium by Judith Herrin

Byzantium: The Surprising Life of a Medieval Empire by Judith Herrin

The Last Centuries of Byzantium by Donald Nicol (the edition I read is dated, some 30 years old; I don't know how recent publications have fared – more academic than the others)

Lost to the West by Lars Brownworth

Byzantium: The Bridge from Antiquity to the Middle Ages by Michael Angold

Streams of Gold, Rivers of Blood: The Rise and Fall of Byzantium, 955 A.D. to the First Crusade by Anthony Kaldellis

Biographies

Anna Komnene and the Alexiad: The Byzantine Princess and the First Crusade by Ioulia Kolovou

Podcasts

The History of Rome Mike Duncan

History of Byzantium

Primary Sources

Anna Komnene's Alexiad

Further research

Historia Civilis, last I checked, has a fairly decent catalogue on Rome and Byzantium on Youtube.

If I think of any more to suggest I'll tack them on in a reblog.

23 notes

·

View notes