#John Gabriel Borkman

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

margaret webster as gunhild borkman and eva le gallienne as ella rentheim in the american repertory theatre's production of henrik ibsen's john gabriel borkman, 1947

#margaret webster#eva le gallienne#henrik ibsen#john gabriel borkman#*#theater#my edits#hi im evaposting again 😽

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

"John Gabriel Borkman" (1978) - Per Bronken

Films I've watched in 2024 (71/95)

#films watched in 2024#John Gabriel Borkman#Jorunn Kjellsby#Astrid Folstad#Wenche Foss#Knut Wigert#Sverre Hansen#Kari Simonsen#Bentein Baardson#Henrik Ibsen#Per Bronken#motionpicturelover's screencaps#FT

1 note

·

View note

Text

Having played parts from Prospero to Stalin, Hamlet and now the poet AE Housman, Simon Russell Beale is convinced he has one of the best jobs in the world. Why? Every new role offers a new area for intellectual investigation, not least when he gets to take on the logical arguments and ‘linguistic fireworks’ of one of his friend Tom Stoppard’s plays, he tells Fergus Morgan

You cannot complete acting – but if you could, Simon Russell Beale would be coming close. Over a three-decade career, he has taken on dozens of classic roles in canonical plays: Konstantin in The Seagull, Ferdinand in The Duchess of Malfi, Oswald in Ghosts, Lopakhin in The Cherry Orchard, Scrooge in A Christmas Carol, the title characters of Edward II, John Gabriel Borkman and Uncle Vanya, and loads more.

And, when it comes to Shakespeare, there are few parts the 63-year-old has not played. Hamlet? Tick. King Lear? Tick. Macbeth? Tick. Richard II and Richard III? Tick, tick. Benedick, Iago, Malvolio, Leontes? Tick, tick, tick, tick. Falstaff and Prospero? Tick, tick.

With a theatrical résumé as comprehensive as that, where does Russell Beale go next? In a recent interview with the Telegraph to mark the release of A Piece of Work, the memoir he “slightly sheepishly” wrote, the actor said he would be keen on playing Cleopatra. Why not? It would not be his first foray into gender-swapped Shakespeare: he played both Hippolyta in A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Desdemona in Othello as a schoolboy.

“Unfortunately, I wasn’t being serious,” Russell Beale says. “I was being facetious, although I did see Mark Rylance do it 20 years ago and it was sensational. It is one of the great parts, but I don’t think that would work. It would probably be too scary for the audience.

“I would love to do Falstaff on stage as I’ve only done that on film,” he continues. “I would like to do another King Lear. I wasn’t particularly happy with my Macbeth, so I’d quite like to do that again one day. I’m getting a bit old now, though, so it has become slightly difficult. Perhaps one day I should try my hand at directing. I don’t know, really.”

Before he has a go at directing, or revisits Lear, or has a stab at Cleopatra, Russell Beale will be playing poet AE Housman in Blanche McIntyre’s revival of Tom Stoppard’s The Invention of Love at Hampstead Theatre in north London. Our interview is taking place via Zoom, with Russell Beale – black jumper, big beard – sat in an office somewhere inside the Swiss Cottage venue.

“There’s a very good novel here about Booth, the man who assassinated Lincoln,” Russell Beale remarks, browsing the bookshelves in front of him. “Anyway, nice to meet you.”

Russell Beale’s pre-interview bookshelf inspection confirms what he subsequently says about his character, about his approach to playing parts and about his professional motivations. He is, first and foremost, driven by an insatiable intellectual curiosity. He once described acting as “three-dimensional literary criticism”.

“I have one of the best jobs in the world, really,” he says. “Every single project potentially offers a new area of study. I know that sounds sort of dry, but if someone says: ‘I’d like you to do a play about a poet in the late 19th century who also happened to be the greatest classical scholar of his time,’ I think: ‘Wow.’ And, for a very short period of time, I get to become a bit of an expert on AE Housman.

“Or take Samuel Foote,” he continues, referencing the 18th-century actor and title character of Ian Kelly’s play Mr Foote’s Other Leg, which he played at Hampstead in 2015. “Doctor Johnson called Foote the most famous man in England, but I’d never heard of him. Now I could tell you all about him – where he lived, how he was arrested for sodomy and the legal case that followed. That sort of intellectual buzz is, I think, the most interesting thing of all about acting.”

Different jobs have different intellectual appeals, says Russell Beale. Some plays are stimulating for their historical subject matter. Shakespearean work is all about “digging around in this incredibly complicated, malleable script to find the emotional life of a character”. Other projects are attractive on a conceptual level, he says, like Joe Hill-Gibbins’ drastically cut, fast-forwarded staging of Richard II at London’s Almeida Theatre in 2018.

“I was far too old to play Richard II,” Russell Beale says. “I’d sort of assumed that was one part I would never do. Then along came this director who wanted to do it in a completely different way. It was incredibly cut down. It was staged straight-through with all the other characters milling around on stage. That was the challenge there.”

From screen to Stoppard

Where, then, does Russell Beale’s work in film and television fit in, beyond boosting his bank balance? His screen CV is not as formidable as his theatrical résumé, but it still encompasses Armando Iannucci’s comedy The Death of Stalin, the latest series of HBO’s blockbuster House of the Dragon, and the forthcoming Downton Abbey film.

“I suppose I just do that for fun, although I do have an interest in how those projects work,” Russell Beale says. “Take House of the Dragon. I remember wondering how they physically achieve a show like that. That was intriguing to me. I thought: ‘How the hell do you do a great big castle in a thunderstorm?’ It was this huge set with water literally cascading down the walls. The sheer skill was extraordinary. That was fascinating.”

If any writer could satisfy Russell Beale’s voracious intellectual appetite, it is Stoppard, whose plays frequently dazzle with their virtuosic use of history and intertextuality. Think of Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, his existential 1966 riff on Hamlet that echoes Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot. Or 1972’s metaphysical murder-mystery Jumpers, perhaps the most philosophically and athletically gymnastic play ever written.

Those Stoppard plays are the only two that Russell Beale has performed in until now. He played Guildenstern at the National Theatre in 1995, having previously performed in the play as a teenager, then took on the lead role in Jumpers – the philosopher George Moore – at the same venue in 2003. That production transferred to New York, and provided Russell Beale’s Broadway debut. The New York Times critic Ben Brantley hailed a “dazzling” performance of “sharp inventiveness and peerless emotional depth”.

“I’ve only done two Stoppard plays, but I’ve always been quite fierce in defending him against accusations of being over-intellectualised,” Russell Beale says. “Stoppard is intellectual, of course. He plays intellectual games. But what Stoppard always comes down to is people feeling passionate about something, usually another person. That, I think, is fundamentally the most important thing about his writing.

“Rosencrantz and Guildenstern is about two men who are lost in a world they don’t understand,” he continues. “Jumpers is about trying to cling on to a broken marriage. I saw The Real Thing recently at the Old Vic, which I saw with the great Stephen Dillane a couple of decades ago. That play is more directly about love than anything else.”

Playing with words

The Invention of Love, which premiered at the National in 1997, begins in the afterlife. Housman, dead at 77 in 1936, stands on the bank of the mythical river Styx, preparing to board a ferry. The play then unfolds through Housman’s memories of his time studying classics at the University of Oxford, with the older Housman – played by Russell Beale – interacting with his younger self, played by Matthew Tennyson. At the heart of its fizzing academic ideas is Housman’s unrequited love for fellow scholar Moses Jackson.

“The play is very complicated,” says Russell Beale. “This morning, we were rehearsing this very elaborate scene with all these 19th-century academics playing croquet. Stoppard ties in so many references to Victorian cultural icons like Jerome K Jerome and Henry Liddell and Lewis Carroll, too. Everyone has these great arias about philosophy and art.

“Underneath that, though, it is about an old man remembering his love for another man,” Russell Beale continues. “It is about a particular event in their lives, a rowing trip on the river when they were both at Oxford. It is about memory. It is about what you do with a love like that. It is about what a love like that means at the end of your life.”

The “incredible enjoyable” challenge of performing the play, says Russell Beale, is really getting to grips with its intellectual complexities and “linguistic fireworks” – as is the case with most Stoppard plays. If you can master the tongue-twisting dialogue and head-scratching arguments, he says, then the profoundly emotional core of the drama will come.

“Years ago, I remember the actor John Wood, who was one of the great language magicians, talking about Bernard Shaw,” Russell Beale says. “Now, I don’t particularly like Bernard Shaw, but Wood said that if you observe all the punctuations that Bernard Shaw set down as indications of when to breathe and so on, he does the work for you. “It is sort of like that with Stoppard,” Russell Beale continues.

“It is like a technical exercise. You have to end the sentence when it ends and make sure you give yourself gaps to breathe. And then it is about the clarity of the argument. The play does explore emotion. The word ‘love’ is in the title, after all. But performing it is not an emotional thing. It is more about a series of arguments. If you can get the grammatical, syntactical construction of the sentences, and then the actual logic of the argument, then you are on your way.”

It helps, says Russell Beale, that director McIntyre read classics at Oxford herself.

“My God, she does know what she is talking about,” he says. “I have no idea what I’m talking about when it comes to Latin or Greek, but she does have that string to her bow.”

The admiration is mutual. Via email, McIntyre says that she finds Russell Beale “extraordinary”.

“I think he is our greatest living Stoppardian actor,” she writes. “The wit and depth of feeling he brings to the character are breathtaking. It’s a privilege to watch him work.”

It helps, too, that Russell Beale is friends with Stoppard, who turned 87 this year. In fact, he adds, he received a first-hand insight into the playwright’s process of putting The Invention of Love together nearly 30 years ago when performing at the National. “I met Tom, I think, when we did Rosencrantz and Guildenstern,” Russell Beale says. “My memory is that he was writing, or thinking about writing, The Invention of Love at the time, because I remember he gave me a lift home once because he was driving in the same direction, and he started talking about Oscar Wilde and Housman on the way.

“I’ve known Tom for years now,” Russell Beale adds. “He was in last week, actually. He was on great form. He likes revisiting his plays, I think. He reads the script very intently, as if he is rediscovering it. It is rather lovely to see him do that. It’s quite moving, actually.”

Russell Beale was born in Penang in what was then Malaya – now Malaysia – in January 1961, one of six children of military physician Peter Beale, who would later become the British Army’s surgeon general, and his wife Julia, who was also a doctor. He was sent to boarding school, first at St Paul’s Cathedral School, where he was a chorister, then at Bristol’s Clifton College.

It was there that Russell Beale first discovered his love for performance, both theatrical and musical – he is an accomplished pianist, oboist and singer, and frequently presents radio and television shows about classical music. He has often credited a stern English teacher called Brian Worthington with instilling in him that respect for intellectual rigour and academic curiosity.

He went on to study English at the University of Cambridge, where he threw himself into student drama and made friends with Tilda Swinton, then trained at Guildhall, initially as a singer before switching to acting, graduating in 1983.

He started his professional career at Edinburgh’s Traverse Theatre, but his big break came two years later with a role in Women Beware Women at London’s Royal Court, alongside a young Gary Oldman. It was not until 1991, however, five years into his long relationship with the Royal Shakespeare Company, that Russell Beale felt like he could fully express himself on stage, when he was cast as Konstantin in a production of Chekhov’s The Seagull staged by the company’s director Terry Hands.

“Until then, I’d done a lot of comic parts,” Russell Beale says. “That was the first time somebody said: ‘No, you can do something serious. You can play someone with an emotional life that is serious.’ Terry did it deliberately, I think. He thought: ‘Here’s this guy who is being typecast and I’m going to cast him against type.’ And that changed my life. It led to people suggesting I do Hamlet and other stuff. I am enormously grateful to him.”

It was Hands, too, who forged one of the great collaborations of Russell Beale’s career, with director Sam Mendes. The pair first worked together at the RSC in the 1990s on productions of Troilus and Cressida, Richard III and The Tempest, then at the National Theatre on Othello in 1997 and, at the Donmar Warehouse, King Lear in 2014 and Twelfth Night in 2002, as well as on the globe-trotting production of The Lehman Trilogy in 2019.

“Sam and I have been doing stuff together for 30 years and it was Terry that put us together,” Russell Beale says. “Sam actually called me when Terry died in 2020. I was in the dressing room for The Lehman Trilogy in New York. He was very emotional. He told me Terry had died and that he was the one who had originally put us together. Terry was the one who said to Sam: ‘I think you’d like that actor over there.’”

There is an alternate reality in which Hands never cast Russell Beale as Konstantin in The Seagull and Russell Beale continued working as a comic actor. He would no doubt have been successful – witness his hilarious turn as spymaster Lavrenti Beria in The Death of Stalin – but he would not have plumbed the remarkable depths he has in this world.

What makes him stand out as an actor – and what has earned him countless accolades, including three Olivier awards, two BAFTAs, a Tony and a knighthood – is his ability to incarnate familiar characters in unexpected ways. He has played the majority of the most famous roles in the classical canon, but his interpretations are always invested with a distinct air of isolation or awkwardness. Perhaps it has something to do with the fact that he has frequently approached those roles at an unconventional age.

“In retrospect, my career sort of looks like this marvellous plan, but it wasn’t,” he says. “It was all an accident. I’ve done all the parts at the wrong age. I was a very old Hamlet and a very old Benedick, and a very young Richard III and a very old Richard III.”

Empathy with outsiders

Nicholas Hytner, another director with whom Russell Beale has a long relationship, having starred in his stagings of The Alchemist, Much Ado About Nothing and Collaborators at the National Theatre in 2006, 2007 and 2011 respectively, and, more recently his versions of A Christmas Carol and John Gabriel Borkman at the Bridge Theatre in 2020 and 2022, has said of Russell Beale: “He has extraordinary empathy with outsiders, the wounded, the foolish, the warped and the lonely. He hears their music and can sing it.”

“What did he say?” asks Russell Beale. “I’ve not heard that before. That is the most beautiful, lovely thing to say. And yes, I’m always excited by those characters. The most interesting parts are those that are looking in from the outside or confused about their position. I don’t know what that says about me. I’ve never interrogated it. I refuse to.”

If Russell Beale does not interrogate his own interest in playing isolated, uncomfortable characters on stage, does he ever interrogate theatre’s wider role in society? “That’s a very interesting question,” he says. “I suppose it is always in the back of your mind. Perhaps theatre is a bit of a sideshow now, although Wicked has just been turned into a film, for God’s sake. The biggest movie of the year started as a theatre show. Perhaps theatre only has a relevance when it is adapted into a medium now.

“No, I don’t think that, actually,” he adds. “That implies it is all about numbers, that something is only important if a lot of people see it. I don’t believe that. I still believe theatre has weight and relevance. I suppose I would fall back on the Tom Stoppard argument in The Invention of Love: ‘There is no little too little to be worth having.’”

#simon russell beale#interview#a really really big interview#the stage#stage#the invention of love#tom stoppard#also stephen dillane mention#stephen dillane#nicholas hytner#blanche mcintyre#2024

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

MWW Artwork of the Day (1/16/24) Edvard Munch (Norwegian, 1863–1944) Starry Night (Stjernenatt)(c. 1922–24) Oil on canvas, 140 x 119 cm. Munch-museet, Oslo

In "Starry Night" you can see a shadow which is cast on the veranda steps by a strong indoor light. The shadow, probably Munch’s own, contributes to the painting’s evocation of loneliness in the face of death. At the same time as Munch was painting the winter landscapes around Ekely he was very interested in Henrik Ibsen’s play John Gabriel Borkman. The shadow of Munch that we see in "Starry Night" could just as well be interpreted as that of Borkman, the old man on his way out into the winter night in order to die in the play’s tragic final scene.

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

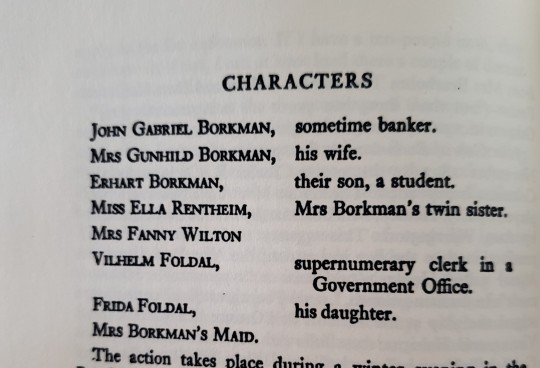

rupert hart davis the plays of ibsen john gabriel borkman hardcover

0 notes

Text

0 notes

Text

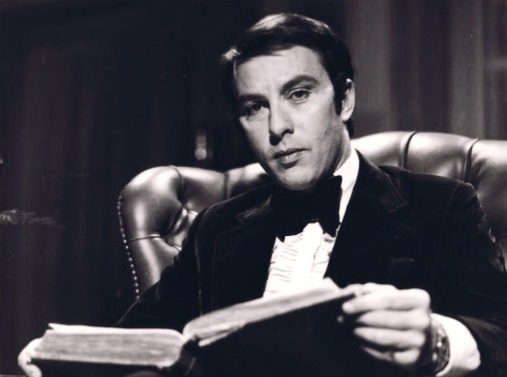

Anthony Valentine in John Gabriel Borkman as Erhart Borkman, ITV Play of the Week version, 1958

Credit: ArenaPAL

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

I read that first one as sometimes baker and was like lol okay cool bro sometimes bakes is that his whole character

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

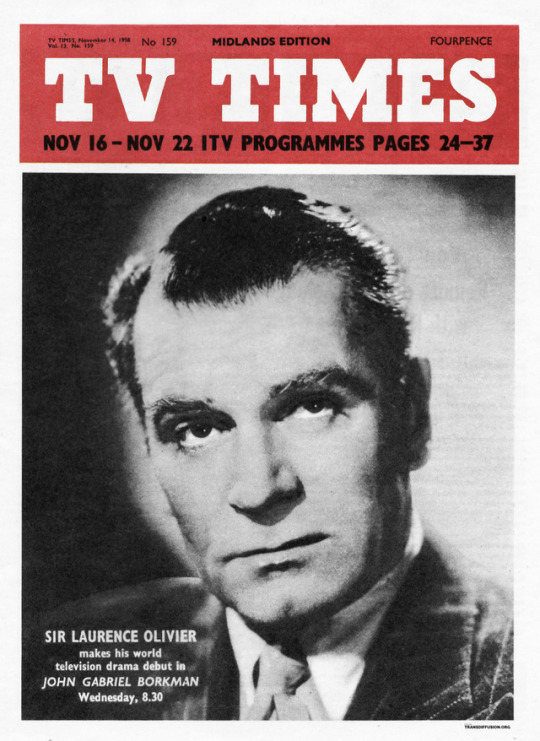

TVTimes Midlands edition, 16-22 November 1958: John Gabriel Borkman

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

20170615 Alan by jenli88 | Specially like his look in period setting. Alan Rickman as John Gabriel Borkman <3

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

the way that so many plays are filmed now like the rsc and nt or stratford ontario or even smaller regional places would film anything...imagine if they used to do that w the rsc during those peter hall years or nt in the 70s 😭😭😭😭😭 i'm really v distraught abt this

#i get how one of theater's magic is in its tragedy of sheer transcience etc but like um guys#imagine if i can see ralph and peggy and wendy in john gabriel borkman instead of my having to daydream abt it :(

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Films I've watched in 2024.

(This list will be continously updated. For a masterpost of the previous two years, see this post.)

Click on the titles below to see the post.

1 - 95

January:

🎬 Barbie (2023) - Greta Gerwig

🎬 "Adjø solidaritet" (1985) - Wam & Vennerød

🎬 "Fröken April" (1958) - Göran Gentele

🎬 "Ansiktet" (1958) - Ingmar Bergman

🎬 "Kvinnors väntan" (1952) - Ingmar Bergman

🎬 "Det sjunde inseglet" (1957) - Ingmar Bergman

🎬 "Höstsonaten" (1978) - Ingmar Bergman

🎬 "Riten" (1969) - Ingmar Bergman

🎬 "Helmer og Sigurdson: Mareritt ved midtsommer" (1980) - Knut Andersen

🎬 "Ronja Rövardotter" (1984) - Tage Danielsson

🎬 "Efter repetitionen" (1984) - Ingmar Bergman

🎬 "Vargtimmen" (1968) - Ingmar Bergman

🎬 "Ocean's 8" (2018) - Gary Ross.

🎬 "Searching for Ingmar Bergman" (2018) - Margarethe von Trotta

🎬 "Skönheten och Odjuret" (1991) - Gary Trousdale and Kirk Wise"

🎬 "Seks personer søker en forfatter" (1992) - Pål Løkkeberg

🎬 "Helmer og Sigurdson: Septembermordet" (1980) - Nandor Hamza

🎬 "The Magic Flute" (1995) - Valeriy Ugarov

🎬 "Galgemannen" (1983) - Magne Bleness

🎬 "Making of Autumn Sonata" (1978) - Ingmar Bergman and Arne Carlsson

🎬 "Le fabuleux destin d'Amelie Poulain" (2001) - Jean-Pierre Jeunet

🎬 "Lån meg din kone" (1958) - Edith Carlmar

February:

🎬 "Drive" (2010) - Nicolas Winding Refn

🎬 "Blue Valentine" (2010) - Derek Cianfrance

🎬 "Helmer og Sigurdson: Spøkelsesbussen" (1980) - Pål Bang-Hansen

🎬 "The Breakfast Club" (1985) - John Hughes

🎬 "Carnal Knowledge" (1971) - Mike Nichols

March:

🎬 "The Making of the Producers Album" (2001)

🎬 "Harold and Maude" (1970) - Hal Ashby

🎬 "The Princess Bride" (1988) - Rob Reiner

🎬 "Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me" (1992) - David Lynch (The Extended Blue Rose fancut)

🎬 "Mødrekupé" (1969) - Magne Bleness

🎬 "Four Weddings and a Funeral" (1994) - Mike Newell

🎬 "Mrs. Harris Goes to Paris" (2022) - Anthony Fabian

🎬 "Bedknobs and Broomsticks" (1971) - Robert Stephenson

🎬 "Leve sitt liv" (1982) - Wam&Vennerød

🎬 "Line" (1961) - Nils Reinhardt Christensen

🎬 "Venner" (1960) - Tancred Ibsen

🎬 "Stimulantia" (1967)

April:

🎬 "ShakespeaRe-Told: The Taming of the Shrew" (2005) - David Richards

🎬 "Flash Gordon" (1980) - Mike Hodges

May:

🎬 "Soldat Bom" (1948) - Lars-Eric Kjellgren

🎬 "Tänk, om jag gifter mig med prästen" (1941) - Ivar Johansson

🎬 "Cruel Intentions" (1999) - Roger Kumble

🎬 "9 to 5" (1980) - Colin Higgins

🎬 "Larmar och gör sig till" (1997) - Ingmar Bergman

🎬 "Presumed Innocent" (1990) - Alan J. Pakula

🎬 "Bergman Island" (2004) - Marie Nyreröd

🎬 "I Bergmans regi" (2003) - Torbjörn Ehrnvall

🎬 "Saraband" (2003) - Ingmar Bergman

🎬 "Tystnad! Tagning! Trollflöjten!" (1975) - Katinka Faragó & Måns Reuterswärd

🎬 "Castaway" (1986) - Nicolas Roeg

🎬 "Lisztomania" (1975) - Ken Russell

🎬 "Alice in Wonderland" (1999) - Nick Willing

🎬 "America's Sweethearts" (2001) - Joe Roth

June:

🎬 "Valentino" (1977) - Ken Russell

🎬 "Georgy Girl" (1966) - Silvio Narizzano

🎬 "Thoroughly Modern Millie" (1967) - George Roy Hill

🎬 "Prêt‐à‐porter" (1994) - Robert Altman

July:

🎬 "La Piscine" (1969) - Jacques Deray

🎬 "Anna Lans" (1943) - Rune Carlsten

🎬 "The Turning Point" (1977) - Herbert Ross

🎬 "Ne réveillez pas un flic qui dort" (1988) - José Pinheiro

🎬 "Le Battant" (1980) - Alain Delon

🎬 "Wit" (2001) - Mike Nichols

🎬 "Plein Soleil" (1960) - René Clément

🎬 "The Girl on a Motorcycle" (1968) - Jack Cardiff

August:

🎬 "Die Hard With a Vengeance" (1995) - John McTiernan

🎬 "L'inconnue de Hong-Kong" (1963) - Jacques Poitrenaud

🎬 "Vingar kring fyren" (1938) - Ragnar Hyltén-Cavallius

🎬 "Women in Love" (1969) - Ken Russell

🎬 "John Gabriel Borkman" (1978) - Per Bronken

🎬 "Jeffrey Bernard is Unwell" (1999) - Tom Kinnimont and Peter O'Toole

🎬 "Mrs. Dalloway" (1997) - Marleen Gorris

🎬 "Fant" (1937) - Tancred Ibsen

September:

🎬 "Gjest Baardsen" (1939) - Tancred Ibsen

🎬 "Kong Lear" (1985) - Per Bronken

October:

🎬 "Voldtekt" (1971) - Anja Breien

🎬 "Bryllupsfesten" (1989) - Wam&Vennerød

🎬 "Columbus ankomst" (1986) - Per Bronken

🎬 "Toralv Maurstad: En lek med livet på scenen" (1993)

🎬 "Hvem har bestemt..!?" (1978) - Petter Vennerød

🎬 "Fleabag" (2019, NT Live) - Tony Grech-Smith & Vicky Jones

🎬 "Hønsesuppe med byggryn" (1969) - Magne Bleness

November:

🎬 "Affæren Anders Jahre" (1991) - Tore Breda Thoresen

🎬 "Det er fra politiet" (1960) - Rønnaug Alten

🎬 "...av hensyn til rikets sikkerhet..." (1991) - Tore Breda Thoresen

🎬 "To Wong Foo, Thanks for Everything! Julie Newmar" (1995) - Beeban Kidron

🎬 "Top o' the Morning" (1949) - David Miller

🎬 "Peter's Friends" (1992) - Kenneth Branagh

🎬 "Gothic" (1986) - Ken Russell

December:

🎬 "Oj då! ...en till?!" (1993) - Chris Johnston

🎬 "Mulan" (1998) - Tony Bancroft and Barry Cook

🎬 "Den sultende klasses forbannelse" (1986) - Carl Jørgen Kiønig

🎬 "Drømmeslottet" (1986) - Wam&Vennerød

🎬 "Svartere enn natten" (1979) - Svend Wam

#films watched in 2024#film recommendations#movie recommendation#masterpost#film recommendation masterpost#movie recommendation masterpost

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

SRB, an actor who has performed more great roles than even Wikipedia can count. If you want to know how palatial his dressing room at The Bridge theatre was while he was playing the title role in John Gabriel Borkman, whether he has sacrificed love for his career, who made his very first costume, the role of sniffing in his famous collaborations with Sam Mendes, how many pints can get him to bed before most of the audience and how certain parts get him to a magical place beyond caring, this is the episode for you.

Act 2

4 notes

·

View notes

Video

“It’s a human need to be told stories. The more we’re governed by idiots and have no control over our destinies, the more we need to tell stories to each other about who we are, why we are, where we come from, and what might be possible.” – Alan Rickman

Alan Rickman at BAM #01 bis ‘Into the storm’ by Marie-Lan Nguyen Via Flickr: Alan Rickman posing for a fan under the snow storm. Stage door session after the performance of Ibsen's John Gabriel Borkman at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, January 11th 2011. This picture was taken a few seconds after #01.

1 note

·

View note

Text

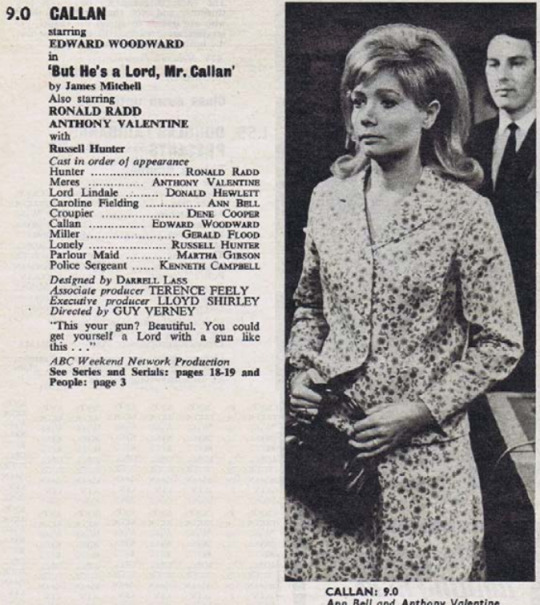

Anthony Valentine - Missing Believed Wiped

Stars On Sunday, Codename (x2), John Gabriel Borkman, The Scarf, Armchair Theatre: The Wager, Callan: But He's A Lord Mr Callan, Vice Versa (x3)

#anthony valentine#missing believed wiped#various tv shows that dont exist now#stars on sunday#codename#john gabiel borkman#the scarf#armchair theatre#the wager#callan#vice versa#dodgy photos better than no photos

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes