#Jesse schell

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Are educational games effective? How I use Games as Instructional Content

This post aims to spark conversation and inspire further exploration into the effective integration of games in educational contexts. Twitter Patreon GitHub LinkedIn YouTube In the vast landscape of education, the effectiveness of games as instructional content remains a subject of vibrant discussion and exploration. The question isn’t just whether educational games are effective, but how…

View On WordPress

#apc#choose your own adventure#ed tech#education#education technology#educational game#English teacher#game design#game design courses#games for learning#if#instructional design#interactive fiction#Jane mcgonigal#Jesse schell#Kansas City#Karl kapp#KCMO#learning game#narrative design#poet poetry#poets#point and click#raph koster#serious games#simulations#storyteller#storytelling#teachin*online#teaching English

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Integrating Gamification in Microlearning: The Four Pillars of Schell's Model

Incorporating gamification into microlearning assets can transform the learning experience, making it more engaging and effective. However, it’s crucial to understand how to integrate the motivational and psychological aspects of games into your microlearning design. Ensuring that the learning objective is aligned with the gamification design is essential to maximizing its impact on learner behavior. This is where Jesse Schell’s Four Pillars of Gamification—story, dynamics, mechanics, and technology—come into play.

Understanding Gamification in Microlearning

Gamification involves using game-like elements in non-game contexts to motivate and engage learners. In microlearning, this means incorporating elements such as points, badges, leaderboards, and challenges into bite-sized learning modules. The goal is to create an interactive and immersive learning environment that enhances motivation and improves retention.

The Four Pillars of Gamification

Jesse Schell, a renowned game designer and author, proposed a comprehensive model for gamification that includes four essential pillars: story, dynamics, mechanics, and technology. Each pillar plays a critical role in creating a cohesive and impactful gamified learning experience.

1. Story

Storytelling is a powerful tool in gamification. It provides context and meaning to the learning activities, making them more relatable and engaging. A well-crafted story can captivate learners' attention, foster emotional connections, and enhance their overall learning experience.

Creating a Compelling Narrative

When integrating story into your microlearning design, consider the following:

Define Clear Objectives: The story should align with the learning objectives and guide learners towards achieving them. For example, if the objective is to teach problem-solving skills, the story could revolve around a character facing various challenges that require creative solutions.

Develop Characters: Characters can make the story more relatable and engaging. Learners can see themselves in the characters, which helps them connect emotionally with the learning material.

Build a Plot: A well-structured plot with a beginning, middle, and end keeps learners engaged. The plot should include conflicts and resolutions that align with the learning objectives.

2. Dynamics

Dynamics refer to the big-picture aspects of gamification that drive the learner’s behavior. They are the underlying forces that motivate learners to engage with the learning material. Key dynamics in gamification include rewards, competition, collaboration, and progression.

Implementing Effective Dynamics

To effectively integrate dynamics into your microlearning design, consider the following:

Incentivize Learning: Use rewards such as points, badges, and certificates to recognize achievements and motivate learners. Ensure that the rewards are meaningful and align with the learning objectives.

Foster Competition and Collaboration: Incorporate elements such as leaderboards to create healthy competition, and collaborative challenges to encourage teamwork. Both competition and collaboration can drive engagement and enhance learning outcomes.

Ensure Progressive Challenges: Design learning activities that gradually increase in difficulty. This progression keeps learners challenged and motivated to continue learning.

3. Mechanics

Mechanics are the specific rules and interactions that define how the game elements work. They are the building blocks of gamification and include elements such as points, levels, challenges, and feedback.

Designing Engaging Mechanics

When designing mechanics for your gamified microlearning assets, consider the following:

Points and Levels: Use points to reward learners for completing tasks and levels to represent their progress. This helps learners see their advancement and motivates them to keep going.

Challenges and Quests: Incorporate challenges and quests that require learners to apply what they have learned. These can be problem-solving tasks, scenarios, or simulations that make learning interactive and practical.

Instant Feedback: Provide immediate feedback to learners. Instant feedback helps learners understand their mistakes, reinforces correct actions, and keeps them engaged.

4. Technology

Technology is the enabler that brings the story, dynamics, and mechanics to life. It involves the platforms, tools, and software used to implement and deliver gamified learning experiences.

Leveraging Technology for Gamification

To effectively use technology in your gamified microlearning design, consider the following:

Choose the Right Platform: Select a Learning Management System (LMS) or gamification platform that supports the integration of gamified elements. The platform should be user-friendly and capable of delivering a seamless learning experience.

Utilize Multimedia: Use multimedia elements such as videos, animations, and interactive graphics to enhance the storytelling and engagement. Multimedia can make learning more immersive and enjoyable.

Track and Analyze Data: Use technology to track learner progress, engagement, and performance. Analyzing this data helps you understand the effectiveness of your gamified learning activities and make data-driven improvements.

Aligning Learning Objectives with Gamification Design

The success of gamification in microlearning largely depends on how well the learning objectives are aligned with the gamification design. Here are some strategies to ensure alignment:

Define Clear Learning Outcomes: Before designing the gamified elements, clearly define the learning outcomes you want to achieve. This ensures that every gamified activity is purposeful and contributes to the overall learning goal.

Map Game Elements to Objectives: Ensure that each game element, whether it’s a challenge, reward, or feedback mechanism, directly supports the learning objectives. For example, if the objective is to improve critical thinking, design challenges that require learners to analyze and solve complex problems.

Measure Impact: Regularly assess the impact of gamification on learning outcomes. Use assessments, quizzes, and feedback to evaluate whether the gamified activities are helping learners achieve the desired objectives.

Case Study: Implementing Schell’s Four Pillars

Let’s consider a case study to illustrate how Schell’s Four Pillars can be effectively integrated into a microlearning program.

Scenario: Onboarding New Employees

A company wants to design a gamified microlearning program to onboard new employees. The learning objectives include understanding company culture, mastering essential job functions, and developing teamwork skills.

Story: The onboarding program is framed as an adventure where new hires are agents on a mission to integrate into the company. The narrative involves characters representing different departments, each offering unique challenges and insights into the company culture.

Dynamics: The program includes rewards such as badges for completing onboarding modules, a leaderboard to track progress, and team challenges to foster collaboration among new hires.

Mechanics: Points are awarded for completing tasks, levels represent stages of the onboarding process, and instant feedback is provided through quizzes and interactive scenarios. Challenges require new hires to apply their knowledge in realistic job scenarios.

Technology: The onboarding program is delivered through a mobile-friendly LMS that supports gamification. The platform includes multimedia elements to enhance storytelling and tracks learner progress to provide data-driven insights.

Conclusion

Integrating gamification into microlearning assets requires a thoughtful approach that considers the motivational and psychological aspects of games. By leveraging Schell’s Four Pillars—story, dynamics, mechanics, and technology—you can create engaging and effective learning experiences. Ensuring that the gamification design aligns with learning objectives is crucial to maximizing the impact on learner behavior and achieving the desired training outcomes. With the right strategy and tools, gamification can transform your microlearning programs and drive significant improvements in engagement, retention, and performance.

#Gamification#Microlearning#Motivational aspects#Psychological aspects#Learning objectives#Learner behavior#Four Pillars of Gamification#Jesse Schell#Storytelling in learning#Learning dynamics#Game mechanics#Learning technology

0 notes

Text

i feel like we’re all ignoring the fact that the only zoraxis hq we know the location of is in madrid and the only one of the fabricator’s workshops we know the location of is in barcelona. this is schell’s way of implying though set pieces and visual narration that they’re fucking nasty.

#suggestive#i expect you to die#ieytd#i know bc jesse schell told me#i just call him jess bc we’re close like that. he told me.

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

my favorite art from the development of toontown

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Quotes on the early development Pixie Hollow (2008-2013) from Jesse Schell, the main creator/developer

This is so funny- Fairies couldn't fly/flying wasn't as prominent at first (from the Art of Game Design)

"I remember when we created Pixie Hollow, a massively multiplayer game for girls based on Tinkerbell. We had a whole design worked out that we felt pretty good about. We said, “Before we get into any production, let’s talk to girls and see how they feel about it.” We didn’t tell the girls, “Here’s what we’re thinking.” We asked really simple questions, like, “If you were a fairy, what would you do?” We thought we knew the answer. We were wrong. The answer was “fly.” We hadn’t been thinking about flying because we’d been focused on the Tinkerbell movie, where flying isn’t prominently featured. We immediately changed our plan. We made it so you’re flying every second of the game. Early conversations can be really important."

"Disney decided that they were going to reinvent Tinkerbell, that she was not the only pixie in Neverland, and that there were going to be a whole society of them. As soon as I heard they were doing that, I was like "how are you not doing an MMO?" It took a couple of years of pitching, but gradually worked up. We cut a deal where we did third-party development on it." (x)

Jesse also pitched the game to Disney outside of the company, so it was worked on outside of Disney

Here is what the game looked like during beta:

116 notes

·

View notes

Text

*Slides over with tutorial books for C and game design*

What's a 'must have' for you when playing a stardew valley-esque game?

#Fr tho “The Art of Game Design” by Jesse Schell is *chef's kiss*#I didn't give two flying fucks about game design before that#But holy moly is that book good#Even if you're more interested in like#Smutty fanfics#That book has you covered

99 notes

·

View notes

Note

So I have a project I need to be working on, but I'm sending this ask now so I don't forget - in one of my game design textbooks, the author (Jesse Schell - cite your sources!) provides this definition:

"Fun is pleasure with surprises."

And I feel like as soon as I'm done with finals we can have a great time dissecting that with regards to the Toymaker and his philosophy. Only a couple days left!!!

ohoho this is a wonderful quote!! i'm sure it's one that the Toymaker would be delighted to learn about 👀

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

if I hear that girls enjoy sim or hyper casual games ever again smh

I’m currently reading a book on narrative design in games. There’re some thoughts on player classifications (mentioning both Bartle’s taxonomy and Jesse Schell’s ideas). I do understand that those are just theoretical concepts that were created solely for game developers. And slightly outdated too.

But I can’t just ignore it anymore. Again, these ideas are not a call to action but rather a reference. But I’m curious whether real developers really stick to any of this stuff.

I mean Pac-Man was developed to attract teenage girls. It’s ‘kawaii’ and doesn’t involve any violence. It was extremely popular. And it was developed like in 70s.

So isn’t Pac-Man a 40 year old proof of the fact that girls presumably don’t play games because they are, in fact, all made for boys? Hear me out there: girls and boys may enjoy different stuff BUT most of the games are made exclusively for boys (at least having them in mind as a key audience). Thus, statement that girls don’t play games is incorrect from the very beginning. It’s just they are not heard or anyhow represented in the industry.

And I’m not even talking about gender socialization which obviously has the greatest impact on today’s situation.

Girls do play games. They are just excluded from gaming beforehand.

Id love to hear any ideas on it

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Toontown: Rewritten Recap: November 2002 (Part 4)

And here’s how November of 2002 (which took place in 2013, but was SET in the year 2002) wrapped up.

November 25, 2002

Sir Max revealed that they’ve managed to open up two more race tracks: City Circuit and Blizzard Boulevard.

How?

Well, he connected the corresponding tunnels in Goofy Speedway to two actual streets somewhere in the world, and he’s not sure WHERE those streets are located.

Just don’t call it street racing, that’ll get the police’s attention, and they’re already not very happy with him.

He also asked the racers to sign some slips of paper before going out to race on the new tracks, because he never got around to alerting the pedestrians to the fact that their roads are now race tracks.

Given that this was over ten years ago, both in and out of universe, I imagine they’ve gotten the gist of it sense then.

(To explain why the Gray was still visible in certain parts of the new track, the patch notes explained that the streets Sir Max connected to Goofy Speedway were still under construction.)

November 26, 2002

The 26th manifests once a month. It is called this because it always occurs on the 26th day.

On November of 2002, the 26th manifested via a post on the Toontown Rewritten news blog by “LL-Terminal43”.

The post was encrypted with some sort of cipher, rendering most of it illegible.

However, decrypting it reveals it to be a transcript of Doctor Dimm (a short, fat green duck in a labcoat, and one of the Silly Scientists from the base game) visiting the lab of Doctor Surlee (that perpetually unhappy monkey Toon with the big stopwatch I mentioned in the first ever recap post).

Doctor Surlee is nowhere to be found, but Doctor Dimm isn’t looking for Surlee, he’s looking for a sprocket he needs for Professor Propostera. Instead, he accidentally activates a scanner that scans, compresses, and sends one of Surlee’s blueprints.

Doctor Surlee arrived partway through the process, and angrily and repeatedly demanded that Doctor Dimm shut off the machine in one of the few blocks of text that WASN’T encrypted, before finally cutting off the transmission himself.

However, a URL for the blueprint was still posted in the blog post, meaning that anyone who decrypted the blog post could follow the URL. There was an extra layer of security, though, all the text on the blueprint was encoded with a Ceaser Cypher.

The decrypted version of which can be found here.

There were no in-game updates that day.

November 27, 2002

Sir Max revealed the grand opening of Chip ‘n Dales Minigolf. Not for business, mind you (they haven’t completed all the golf courses, plus the golf balls don’t obey the laws of physics), but for visitors.

He apologized for misspelling “for” as “fore” in the new update headline, noting that golf still isn’t actually playable. Toons aren’t exactly knowledgeable when it comes to good business decisions. If only they had robots to do that for them.

Irrelevant to the news post, Goofy was hit in the head with a wrench in a freak accident at Goofy Speedway, reminding him how to do math, thus allowing the Ticket System to work as intended.

As for Chip ‘n Dale’s turf?

A mystery tunnel’s been added to Chp ‘n Dale’s Minigolf. Walking through the Mystery Tunnel causes any Toon who uses it to be deposited right back in Chip ‘n Dale’s Minigolf.

November 28, 2002

Sir Max decided to celebrate Thanksgiving by thanking everyone who worked on the original Toontown Online, especially Jesse Schell. He also thanked everyone in the community, and brought up Jesse Schell’s attempts at reviving Toontown Online in an official capacity.

Also, everyone was given an (unfortunately culturally insensitive) traditional hat to celebrate Thanksgiving.

(The hats were taken from the base game, so it’s more Disney Interactive’s fault than TTR, but even if Corporate Clash didn’t exist back then, nowadays they’ve gone and removed all the “Native American”-themed accessories and decorations to replace them with more PC items. Toontown Online WAS a product of the Early 2000’s, after all.)

November 29, 2002

Everyone’s traditional Thanksgiving hats were removed for now. In the future, those hats will be available for purchase in the Cattlelog, but as Toons didn’t have homes at the moment, that wasn’t possible back then.

Sir Max opened this blog post by talking about the crazy currencies some Toons had been investing in: Marshmallows, Jawbreakers, and most insane of all: Paper. What kind of idiot would use paper money?

Anyways, Sir Max decided that all the doomsaying about the inevitable upcoming collapse of the Jellybean Economy is a sign that he should invest in fish.

He tracked down the Fish Bingo Operator (Hawkheart) and had a chat with Fisherman Freddy to have Fishing Ponds installed in al neighborhoods, not just Toontown Central.

And I was right earlier, that hole in the ice where the hockey rink was stolen from WAS where they ended up installing the Brrrgh’s fishing pond!

He also found these shiny, golden rocks that he wrote off as completely worthless (“Who would pay money for gold?”) and used them to make Golden Fishing Rods for everyone in Toontown.

Speaking of money, Sir Max was very hopeful that the Toons would give him all their fish instead of selling them to the fishermen or pet shops. TOTALLY not so he can make all the Jellybeans himself, what are you looking at him like that for?

Everyone also received Jellybean Jars big enough to hold 250 Jellybeans.

November 30, 2002

Sir Max announced a red alert, canceling that week’s Super Saturday update.

Something terrible and evil has taken to the skies, descending upon Toontown in a horde that threatens to take over. They’ve flocked to the streets that were once completely devoid of crime and evil.

It’s said that they can even make a Toon Go Sad.

It seems as though Toontown Online’s villains have finally been implemented! It was time for the Toons to gag up and fight for their home!

The Labs kept trying to alert Sir Max to the fact that the “dangerous invaders” were just harmless butterflies, but he’d already stocked up on cream pie filling and boarded up his windows.

The butterflies that flutter around Toontown Central were the only thing added that day.

Ah well, we’ll see if those peaceful days extended into December soon enough.

-

god I wish a wrench would remind me how to do math.

also uh. Rip to those hats but its very 2002

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Movie Review | 99 Women (Franco, 1969)

In some ways, Women in Prison is the perfect genre for Jess Franco. On the one hand, it’s a good way for him to integrate his antifascist politics into his work. The warden is an obvious proxy for an authoritarian leader. And this movie in particular positions the prison (nicknamed the “Castillo de la Muerte”) in the context of the greater political system. And with Maria Schell’s kindly reformer character, Franco explores the difficulty of trying to do good within a fascist system. "I seem to be a victim of a disease that does not flourish behind prison walls. I suffer from an excess of humanity." (In terms of dialogue, this is one of the most sharply written Franco films I’ve seen so far.)

On the other hand, it’s a good outlet for his exploitative tendencies. This movie is very much in line with classic WIP tropes, but there’s no denying that Franco has a good handle on them. A lot of this movie’s success comes from the casting of the usual WIP roles. You have Mercedes McCambridge as the cruel warden, doing a lot of histrionics but bringing an intensity that keeps her character from becoming pure camp. ("It is not meant to be a happy place.”) You have an icy Herbert Lom as the torturer, lent an additional steeliness from his tiny glasses and his stand collar jacket. You have some sympathetic presences among the prisoners in the likes of Maria Rohm, Luciana Paluzzi and others, and an appealingly vicious one in Rosalba Neri, who was one of the primary factors in me seeking this out.

You know she’s treated differently than the others because unlike them, she wears stockings, although this isn’t quite as shameless as later WIP efforts from Franco, as the prisoners at least have underwear, instead of the no pants look you get in stuff like Barbed Wire Dolls so Franco can zoom in on bush with some regularity. But at the same time, Franco complicates matters by giving her a sympathetic backstory and letting something of a heart emerge as the movie progresses.

And while this is less explicit than later efforts, Franco is still getting off on the titillating elements. He directs the flashbacks with a sense of stylization that evoke the covers of tawdry paperbacks, letting the sheer visual lushness brush up against the ugliness of the content. And in classic Franco fashion, we get a whipping scene and a sexy nightclub performance with arresting lighting changes. This also gets some bonus points from me for the great song that opens the movie, “Day I Was Born”, sung by Barbara McNair in soaring vocals with girl group style accompaniment.

So I liked this quite a bit, but I do think this loses some steam during the escape attempt in the last third, as Franco gets less visual mileage out of the wilderness than the prison environment. And there’s a pretty unfortunate scene where the characters harm a snake for real during that stretch. So while I do recommend seeking this out, you may need to brace yourself for that scene.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

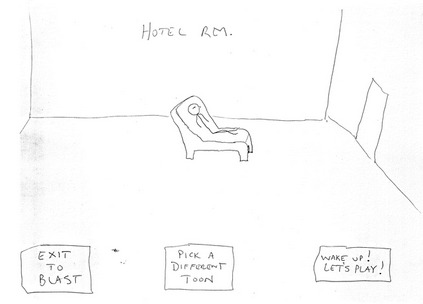

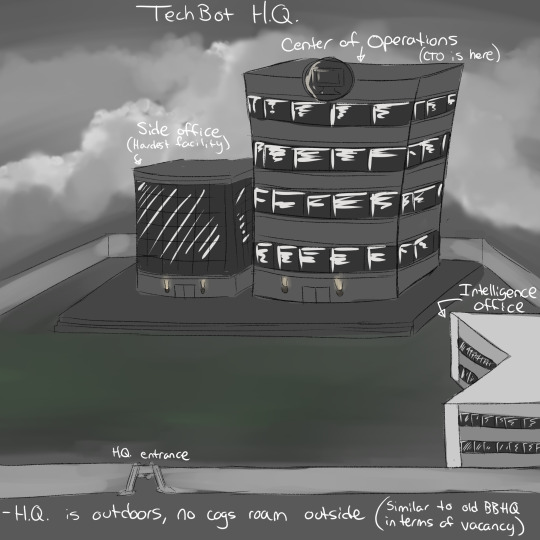

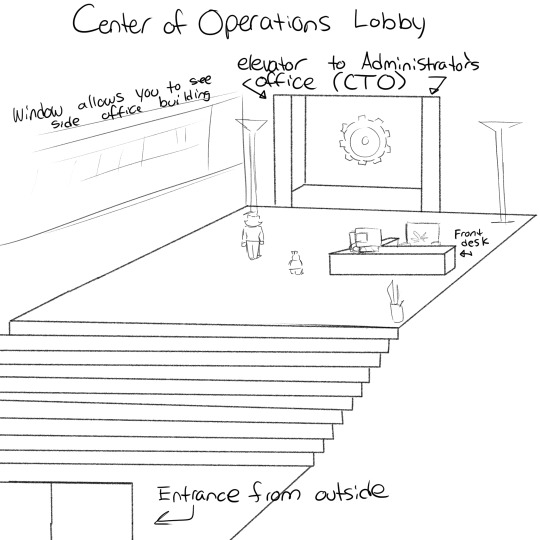

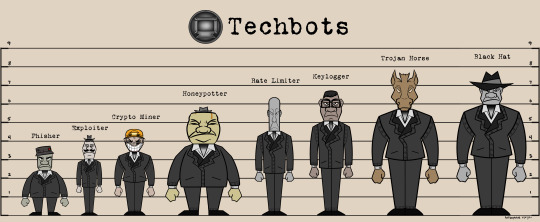

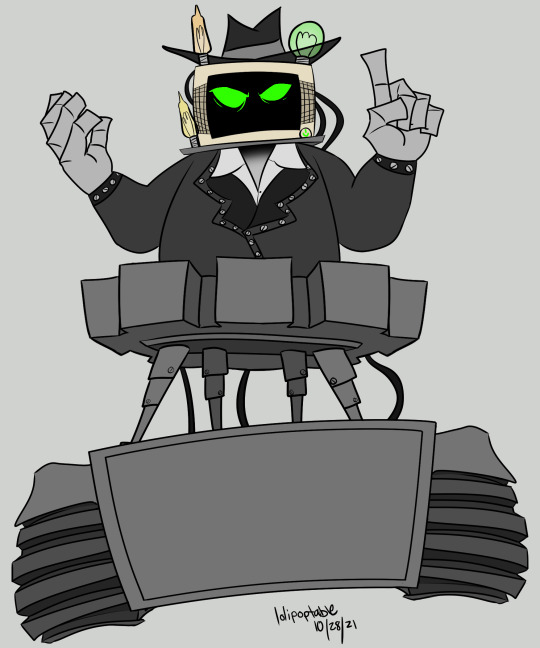

Nearly 2 years ago on Reddit, I posted my concepts of my own spin on a 5th cog type, TechBots. Since then, I have roughly laid out concepts of TechBot H.Q.

These concepts I originally came up with when experimenting with ideas of a 5th Cog type, and with inspiration from Jesse Schell allegedly claiming if there would be a 5th Cog type, it would be technology related, I got to work brainstorming ideas.

Originally, I had posted my initial Cog concepts in May 2021 as sketches, then followed with completing the roster chart and a finalized design for their Cog Boss, the CTO (Chief Technical Officer). I had realized Operation Dessert Storm had also created Cogs of the same name, so I had to experiment with not replicating any ideas and names that ODS had done. I am quite pleased with these ideas so far!

I wanted to go with the same design elements of the original 4 types, with most of them being human caricatures. Their aesthetic is 1980s-1990s tech and office culture, with grey suits with popped collars and the CTO being a offwhite eggshell colored CRT monitor. I wanted to exemplify the boring and mundane office vibe.

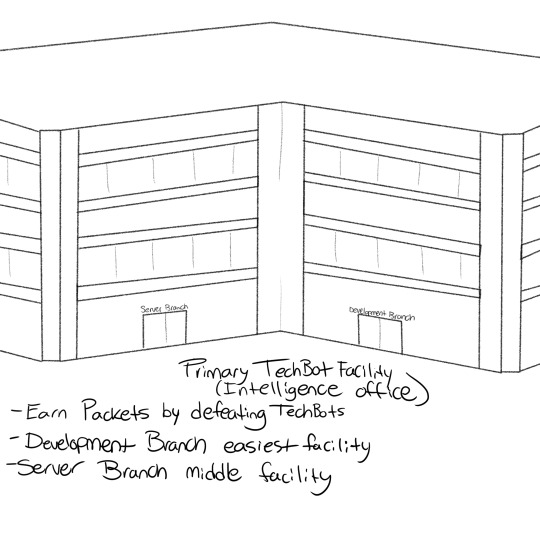

Their H.Q. would be composed of 3 buildings, directly in front of the entrance is the Center Of Operations Building, where upon entering the lobby you can take an elevator up to the Administrator's Office, where the CTO resides. To the left is the Side Office Building, where important operations take place and only the most important and highest of level Cogs reside. The Side Office is the hardest facility (in the same vain as The Back Nine).

Closer to the entrance, but to the right is the Intelligence Building, where the Server and Development Branches reside. These are two more Cog Facilities, with the Development Branch being the easiest facility, and the Server Branch being the middle-difficulty facility. Inside these facilities are labyrinths of cubicles and water coolers, cogs can be seen sitting at their desks and some roaming around. You would traverse through the hallways of the Development Branch similar in aesthetic to the DA Offices and occasionally run into cog battles with two roaming cogs (like in Sellbot Factories) and two cogs sitting at their desks. When engaging with the roaming cogs, the two cogs sitting nearby will sit up and approach and also walk into battle. You may also while exploring enter break rooms, where more cogs are residing, ready to be disturbed. At the end, the Branch Developer can be reached. Break rooms may also have Gag Barrels!

The Server Branch is composed of roaming cogs similar to the Sellbot Factory's exclusively, and the hallways are narrow and full of server towers. Running wires are strewn about the floor and the walls and it is a multi "Doom Room" kind of facility until you reach the end. At the end, the Maintenance Manager can be reached. Break rooms can also be found, with cogs and Gag Barrels.

The Side Office is similar to DA Offices where there are multiple floors, combinations of cubicles like in the Development Branch and server towers like in the Server Branch could be seen. Break rooms with Gag Barrels can be found with cogs waiting to be disturbed. Eventually you will reach the 6th floor, where at the end you will fight the Vice-Administrator.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

the fact that toontown has had an event for the ides of march since tto is so fucking funny to me, i cant think of a single other game that has one. bravo jesse schell

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

ok one person liked that post so you're all getting my in-depth puzzle analysis based off of jesse schell's metric of what makes a good puzzle, exclusively for the puzzles in ieytd1 because those are the only ones i've had the time to dissect.

First thing's first, before we talk about how well IEYTD1's puzzles have upheld the puzzle principles, we must understand what the puzzle principles are. In total, there are ten of them, some more self-explanatory than others:

Make the Goal Easily Understood (Without a hunch as to how to even begin, a player will be hard pressed to spend the time solving your puzzle)

Make It Easy to Get Started (Even if you know what your goal is in the grand scheme, if you don't know the first steps to get there, you'll be at a roadblock the second you start)

Give a Sense of Progress (Your player may be on the right track, but without knowing that for certain, there's a risk of abandoning the path forward)

Give a Sense of Solvability (A puzzle should never be obtuse to the point of being obsolete. You're here to play a game with your player, not to stump them. You both want them to have fun)

Increase Difficulty Gradually (If you throw players into the deep end too quickly, they may end up backing out. Coax them gradually, build their confidence, and show them they can do this)

Parallelism Lets the Player Rest (If a player gets stuck on one puzzle, let them work on something else for a little while... If they have other things to do, they won't hit a roadblock as quickly)

Pyramid Structure Extends Interest (What's better than a linear narrative of puzzles? One, two, or even three solutions from prior puzzles coming together to solve one big finale!)

Hints Extend Interest (If a player can't solve a puzzle, don't expect them to keep ramming their head into a brick wall. Make sure they're being steered in the right direction)

Give the Answer! (Contrary to popular belief, it's not a bad idea to allow your player to have the answer- so long as you do it properly. They function similarly to clues, and can be important. Sometimes, the player may not know they have the answer at all up until they finally need it)

Perceptual Shifts Are a Double-Edged Sword (Consider any riddle that forces you to think outside the box. Where it may be satisfying to either solve or receive the answer, you either get it, or you don't. There is no chain of reason rather than a rule you must break to see the puzzle from the correct perspective. While fun in certain contexts, it is a huge gamble for a potential player)

Right. Now with our method of judgement out of the way (with our biases leaning towards Schell, considering he was the one to create the rules our puzzles must follow), lets get onto the missions themselves, and see which ones adequately follow and embrace the rules of the principles:

Friendly Skies

Easily understood goal

Easy to get started

Sense of solvability

Hints

Friendly Skies really is a great tutorial mission, if not a rather short one. But what’s probably its best attribute is its setting, believe it or not. Not being in a plane, but being in a car. Right off the bat, it hits not only one, but two of the 10 puzzle principles: It’s easily understood, and easy to start, and the two complement one another rather nicely.

It’s highly unlikely that a player would have never set foot in a car before. It’s a familiar environment, and partnering that up with their objective (that being to steal the car without becoming a fatality), the gears begin turning in the player’s head before half a minute’s even passed. You have to steal the car. Okay. Key’s not in the ignition, so you have to find a way to turn it on. There’s only so many places you can look, and you- familiar with cars, of course- know exactly what each of those places are…

One of my favorite parts about this puzzle from a tutorial standpoint is not only the fact that it teaches the player the ideal thought process for engaging with puzzles in the series, but the actual location of the key is probably one of the last places you would be searching for one. Meaning that it’s likely the player is going to find all the clues they’re going to need later in the level before they actually progress to those sections of gameplay.

I have to say the same with the bomb manual hint- it doesn’t just allude to a future puzzle, but also to the sort of thought process that you’re going to have to use for the entire rest of the game. The game’s not just going to hand everything over to you for free. You have to really pay attention, make your own deductions, and if you don’t, you’re not always going to get the proper leeway to recover from it.

Another thing to note- on the subject of hints- is that the game goes out of their way to show you exactly what button you need to push to activate the grenade canons. What it doesn’t do is give you any way of figuring out what each of the other buttons do. In this level in particular, that’s not much of an issue, but in future missions I’ll touch on it more.

As an introductory level, Friendly Skies is pretty smooth. Of course, though, there’s one notable gripe that I don’t even think I need to mention. That being the game prohibiting you from using the knife as a screwdriver. A conscious choice on the developers’ behalf- and if the handler’s lines didn’t make that obvious, they’ve mentioned it themselves on a few occasions. They were aware players would want to use the knife as a multipurpose tool, and directly disallowed it.

While I have no confirmation on the matter, I have to assume that they did this because they wanted the player to experience the toxic gas- either to teach them to take risks, or to show them that some hazards are less immediately lethal than others. Whatever the case, though, it comes at the consequence of teaching the player something that isn’t true: that levels have one concrete ‘solution’ that the player must stick with. One of the things IEYTD is known for is their leniency with puzzles. Their speedruns and achievements encourage the player to experiment and find different methods of solving the same puzzles. So, while it’s not the worst decision in the world, I find it odd that they would choose to send such a misleading message about their gameplay mechanics in the tutorial level, of all stages. Beyond that, however, Friendly Skies is a great stage for easing new players into the gameplay, if not a bit flat in comparison to future missions.

Squeaky Clean

Sense of progress

Hints

Easily understood

Easy to get started

Sense of solvability

Difficulty of scaling

Squeaky Clean is certainly a bold jump forward from the tutorial, going from one of the shortest missions to one of the longest in the entire game. Out of all of Schell’s principles, its strongest one is the player’s sense of progress.

Nearly every time the player accomplishes something, the environment changes around them. And while it may not exactly correlate to what it is the player’s done, there’s still an innate sense of progression through the new obstacles. Broke the glass to the lab? Now you’ve got to deal with security systems. Got access to a new chemical? Better hope you can blend in, because you’ve been noticed by an operative. Even if the player isn’t certain on what their next course of action is, they still know they’ve made progress in some form or another.

I also have to say that the hints- while occasionally a little too indirect for some players- encourage thought and memorization. Especially by the means of giving the player one of the chemical reactions (the purple and green smoke bombs) before they’ve even touched anything. They can observe the compound, and if they mishandle it enough, see what the reaction is. If they cross compare it to their cheat sheets, it doesn’t take long to identify what each specific chemical is, and how to match up the ones on the periodic table to the formulas to create their own.

I will confess, though, that in many ways, Squeaky Clean is quite poorly constructed- especially for a second level. As aforementioned, the jump from Friendly Skies to here is quite immense; to the point where even spawning into the level might give the player some whiplash.

Squeaky Clean is neither easy to understand, nor easy to start, as opposed to its predecessor. Of course, no matter how well the player performed in high school chemistry, they’re not even going to know where to begin disarming a chemical bioweapon. It isn’t always bad game design for a player not to know how to solve a problem presented (more often than not, figuring that out is what the puzzle is supposed to be). But in a circumstance like this one, it can quickly become rather overwhelming.

What’s more, the player has gone from a closed off car with all the tools at their disposal, to a packed laboratory that’s completely unfamiliar to them. Even if, hypothetically, they were aware of how to make an antivirus, with so many new tools introduced at once, it’s hard to know which ones are relevant. Will they need to freeze chemicals? Will they need to burn them? How would they know which chemicals are safe to burn? Are there any other tools they need to uncover before they start? And what does that red button do? It’s good to get your player asking questions, but less so when they’re asking them all at once.

By far what has to be the biggest hurdle in this mission is its difficulty scaling. Both in regards to the level itself, and its position as the second level in the game. The lead up to the final puzzle is slow, cautious, methodical- and it has to be when you’re working with chemicals you haven’t even heard of before. But the climax of the mission throws all of that out the window when it introduces the player’s first timed puzzle.

There are many issues with this. There’s no build up to prepare the player for an encounter of that nature. On a first playthrough, there’s zero indication you’ll be remaking (or that you should be premaking) chemicals that you’ve already made until the timer’s already begun. And even beyond that, time trials introduce frantic behavior, which a level such as this one doesn’t benefit from.

The player, in their haste to complete the objective, may accidentally put the wrong combination of chemicals into the mixer and blow themself up. They may create the wrong chemical compound, making a canister they don’t actually need. They may properly make the chemicals, but may destroy the vial on their way to use it. Not to mention, since you’re several stories in the air, if you accidentally drop it with that new telekinesis mechanic you’re getting used to, you’re not getting that thing back. And worst part of all, it’s at the very end of a mission. If you die- for whatever reason- it’s back to the very start. As great as it feels to actually succeed at the mission, players may never get that satisfaction if they build up too much tension from the trial and error. Even if- to a particular extent- trial and error is what the series is known for, it’s different when you know what to do, but circumstances beyond your control make that objective more difficult.

Deep Dive

Parallelism

Hints

Answer

Easily understood

Difficulty scaling

Deep Dive is notorious for being a cramped and uncompromising level, and those with claustrophobia tend not to rate it very highly. However, in regards to its puzzles, there are a variety of things it does very well.

One of the highlights of this level in regards to the puzzle principles is its use of parallelism- and it’s the first puzzle in the game to actually employ it. Though it’s only relevant for about the first quarter-to-half of the mission (depending on how quickly you can make it through everything else), the player is given free reign to handle a myriad of small tasks, complete with a checklist so they’re not left in the dark on what’s left to do. Much like the act of finding the key in Friendly Skies, this also acts to introduce the player to the shape and feel of the level, and the resources held within.

This is also one of the earliest examples of the player receiving an answer to a puzzle- granted, it’s in a roundabout way of needing to piece it together themself. While the grenade hint is far more ambiguous, relying on resourcefulness and not moving too hastily, the self-destruct code serves to test the player’s competency under pressure. Despite presenting the player with the answer, the puzzle itself isn’t made much easier.

Though speaking of competency under pressure, it’s what the entire level is known for. And despite that being the theme for that particular mission as a whole, it doesn’t change the fact that its difficulty scaling is less than desirable. Ironically enough, it suffers the exact opposite issue that Squeaky Clean did. Whereas the previous mission was slow and steady up until the last possible moment, Deep Dive keeps a brutal tempo pretty much all the way through, with no chance to breathe until the mission’s over.

The game takes some initiative to alleviate the actual input the player needs to do (for instance, implying that the player specifically needs a pin to neutralize Zor’s grenade, thereby making the fire extinguisher unlocked and primed by the time it needs to be used), but- same as the last level- it can very easily lead to trial and error as the player hacks away at each individual malfunction, having reacted too slowly to understand what to do in the time they were provided. The challenge of the mission comes from being quick on your feet, but there’s only so many things a player can keep in their head all at once.

Also, while it’s not necessarily the biggest issue to be found in the stage, I find myself fascinated with the way that it’s presented in the introductory briefing. Certainly it was meant to tie back in with the motif of unexpected change of plans, but it’s the first time a mission briefing doesn’t at all aid with the puzzle the player will be facing. The escape pods are mentioned by your handler, true, but very briefly, and with nothing good to say about them. So when the player enters the mission only to find themself exactly where they were told not to be, chances are they’re already at a loss as to how to handle the situation. To reference a specific principle on the list, players’ ease of understanding is likely to be low.

Thankfully, the game does a good job at combating this potential paralysis spot by specifically giving the player a list of tasks to complete. And while this helps, the player is doing them because they have no other plan of attack, instead of in accordance to (or in spite of) a potential strategy. I would even argue that the wording of the briefing could have made the onboarding a little easier to understand. Say, if the player was warned that the escape pods are often tampered with, or that one wrong course of action could lead to a mouthful of saltwater. It still communicates the same feeling of dread, but now the player has things to look out for. I should make sure there aren’t any traps in here. I need to make sure I’m ready for any leaks. Instead, the player is left at the bottom of the ocean with the pre-instilled knowledge that they’re going to die any second. And while that’s probably true, it doesn’t make puzzle solving (or puzzle identifying) any more intuitive.

Winter Break

Sense of progress

Parallelism

Pyramid structure

Hints

In regards to well crafted and engaging levels, Winter Break just about knocks it out of the park. Ironically enough for being just about halfway in the game, it’s probably one of the most methodical levels sans the tutorial itself. But that doesn’t mean that it isn’t still exciting, or any less well constructed than the others. Quite the opposite, in fact.

Similar to Deep Dive, Winter Break has a heavy emphasis on parallelism. However, unlike the previous level, the amount of tasks that the player is able to complete at one time is vastly increased. This greatly helps with the pacing of the level; the more things the player is able to do at any given time, the less likely it is they’ll be sitting around, butting their head against one specific thing.

This specific puzzle format also introduces an elusive principle yet to be discussed: pyramid structure. The climax of the mission can only be unveiled once the player has found the security chip, and the Zoraxis orb, a process comprising of four separate puzzles the player can tackle at their leisure. Though a casual player may not even realize the leeway they’re given, there’s a greater sense of reward that comes from all of their actions leading to one high stakes encounter.

The hints in this level come in a wide variety, from diagrams on sheets of paper, to clues hidden within picture frames, to secrets unveiled through the classic art of bookshelf scouring. An important thing to note though, beyond the ways in which the hints are given to the player, is the order. More specifically, all hints that focus around the final objective are locked in the same location as those two key items. Even if the player doesn’t understand their importance initially, by the time they actually need to put that knowledge to use, they’ve already primed their minds with the information they need.

The ebb and flow of the difficulty is to be greatly admired as well. Working in tandem with the parallel puzzle solving, it keeps the player at a comfortable pace the whole time, riding the line between peaceful downtime and engaging action moments. Winter Break’s traps are also noticeably more readable than some of the prior missions’.

The bear archer’s method of attacking leaves plenty of room for the player to identify the hazard and react accordingly, and in regards to the final act’s lasers, the player is given ample time to study their speed and direction before it becomes an immediate threat. Not to mention the lasers only activate upon destabilizing the first crystal, ensuring the player knows what’s expected of them before the situation gets dicey. Even the deer gas feels more like a puzzle to solve than a hazard to evade, seeing as a player would only recognize it as a key to a lock after a thorough examination of its diagram.

Overall, Winter Break manages to be cohesive, readable, engaging, and exciting, without sacrificing player experience in the same way some prior levels did. As it stands, it’s probably one of- if not the best constructed level in the entire first game.

First Class

Difficulty scaling

Easily understood

Answer

Hints

Sense of solvability

First Class was Schell’s first level post IEYTD1’s official release, and the team intended to go in a far more experimental direction than their previous missions. Though they accomplished the task on numerous levels, their puzzle implementation was equally as unusual, and not always in the best of ways.

If there’s anything the mission can be commended on, it’s the difficulty scaling. By this point in the game, players are well equipped to handle most threats that come their way. While the mission doesn’t pull any punches, it has a pretty comfortable flow, working its way up from slow and experimental deduction to pushing the limits of the player’s reaction times. While a surprising number of the puzzles in this stage have lethal consequences for failure, most of them still remain feasible and fair.

… Except for the birthday puzzle, anyways. It’s potentially the weakest puzzle in the entire series, all due to its surprising complexity. The game asks the player to keep track of three variables- the day of the week, the date of the month, and the number of the month itself. On top of that, they’re given nothing to help them keep track of the information they’re given. There’s no method of writing it down, and with a headset strapped to their face, counting on their fingers isn’t even an option at their disposal. The player only has three attempts to punch in the number correctly. And what’s worse, there’s no indication on whether the date needs to be arranged month-to-day, or vice versa.

It has the potential to be quite the frustrating roadblock, and certainly puts the game’s sense of solvability into question. The variety of feedback the player receives is far too slim for all the tasks they’re expected to perform. Even if the panels behind the numbers lit up for each unsuccessful attempt (yellow, perhaps, for a correct number in the wrong spot, and green for a correct guess) would at least take some strain off of the player’s shoulders. But by the time it takes to return to the puzzle, should the player have failed it before, they may have forgotten what combinations they previously tried.

This mission is also one of the slim few examples of an answer being presented in a way that isn’t exactly intuitive. Though phrased in a way that would imply it a clue, when the handler contacts you over intercom, he straight up gives you your first objective. Find clues to light up certain buttons in the panel on the wall. Seems simple enough on the face of it. But its usefulness as an answer can only get the player so far, if only because of one specific reason: it’s a spoken answer.

In a perfect world, a player may find and open all four panels as soon as possible at their handler’s request. But what’s most likely the case is that a player will be quick to enter the most obvious code- the one etched into the phone casing, before promptly forgetting about the instructions all together. Which poses a significant issue as far as the defector’s request is concerned. At best, it takes stumbling into a new hint for the wall for the player to recall the buttons’ existence. At worst, they may tear the entire train car apart, seeking for the clue that they don’t even know they’re missing.

We must also take the opposite into consideration- what if the player is too obedient to the handler’s command. After all, he specifies four total doors… But two of the four possible hints could have been literally flung out the window by the player, with no indication of it being a bad course of action. It’s a strange case of revealing a little more than necessary- even for the standards of the answer- and the player may end up relying upon the advice, even to their own detriment.

There’s also the context of the mission itself to touch upon, and the ease of understanding (or lack thereof) that comes with it. In a way, it’s similar to Deep Dive’s briefing; the context you’re given contrasts with the actual scenario at hand. While it becomes obvious rather quickly that you’re not on vacation, and while it doesn’t take too long for your handler to explain what he’d like you to do, halfway through the mission you end up… completing the objective. The remainder of the level is a gauntlet of Zoraxis operatives (and one spear wielding man), steadily ramping up in intensity.

Though it’s not exactly a detriment to the level, there’s a heavy sense of sporadicness throughout the latter half of it. It feels less as though you’re playing the level, and more as if you’re outlasting it. It proves a fun challenge, though there leaves a strange sort of “Now what?” feeling in between obstacles that can make the pacing feel a little stilted. While it can be exhilarating to perfect after a bit of practice, an initial playthrough takes a bit of bobbing and weaving through the occasional pocket of confusion.

Seat of Power

Sense of progress

Hints

Difficulty scaling

For as late as it appears in the game, Seat of Power is one of the quicker missions the game has to offer, when it comes to repeated attempts. This doesn’t make it easy by any means- quite the contrary, most of the speed of a second playthrough comes from a thorough understanding of the mission’s mechanics.

The mission’s strongest puzzle principle would have to be its sense of progress. While future IEYTD titles would really push the boundaries of evolving setpieces, Seat of Power was a pretty good starting point. The world around you is snappily responsive to your meddling, and the further you probe at Zor’s head controls, more tools and mechanics reveal themselves to you.

And that isn’t even mentioning the way that the level’s NPCs react to your actions. While they serve as lethal puzzles in their own right, they also convey that the player is doing something right (or if not exactly right, then on the right track).

In many ways, this particular mission has some excellent hints. Between learning about Professor X-Ray, to being steered towards the conclusion that there’s one placard too many for the number of seats at the table, the reveal of the goggles sparks a sense of excitement as the pieces click together. Even if the player stumbles across the solution, the recollection of the hints gives them the same feeling of satisfaction, despite the fact that a puzzle wasn’t exactly ‘solved’, per say.

However, in other ways, the hint system in Seat of Power is deeply flawed. The control panel you unveil rather early on in the level is a great example of this.

In order to solve the second wave of puzzles, the player is expected to experiment with the buttons at their disposal. While experimentation is hardly foreign to the series by this point, hidden within the control panel is one button that kills the player instantly, unless certain conditions are met. And what's more, there’s nothing in the level that would even vaguely point the player to that conclusion.

It’s made even more frustrating by the fact that the tools you need to avoid that death can only be found if you push the button to the right of it. I Expect You To Die was originally an English exclusive title. With that audience in mind, it seems rather obvious that players who would read text from left to right would also push buttons in the same order. For how much care the game seems to take to warn the players of the threats around them, this one being so haphazardly strewn in feels almost like an intentional kill.

Unlabeled buttons- if you can recall- had a similar presence in Friendly Skies. However, at least in that mission, buttons the player needed to know about were labeled, and optional buttons were left undisclosed. It would have been quite easy for the same premise to apply here, with the button that unlocks the gas mask being referenced in some sort of note floating about the office, or some text scratched on the side of the button panel, with the poison gas button left the same. Or vice versa, where the trap was clearly labeled, but the resource to defend oneself against it was up to the player to decide.

In a level that hinges on the player pushing all the buttons at their disposal, it seems suboptimal to ‘train’ them into being wary of doing exactly what they’ve been asked to do. Oh, I probably shouldn’t push buttons when I don’t know what they do, the player might think. Which, while very true, doesn’t help much when they’re left with little other choice.

Of course, I don’t believe I can talk about Seat of Power without referencing the Madrid puzzle, either. While your handler states very bluntly in your briefing that you’re going to Madrid, expecting your player to hold onto key information for a level they haven’t even entered yet is quite a tall ask for any player. But even beyond that, the developers admitted that no one listens to the handler anyways.

To aid with this, they attempted to sprinkle in some Spanish themes in the set dressing to better set the tone. While this certainly helps to a certain extent, the people who it helps are those who can identify the culture they’re being presented with. In that regard, the puzzle becomes more akin to a trivia game, or a riddle, where a player needs context derived from outside of the experience in order to solve it. Generally not a very good practice in escape rooms, both in the real world, as well as virtual ones.

However, the other- perhaps far more pressing complication with the Madrid puzzle is assuming that the average person knows where Madrid is on a map. For the geographically uninclined, this is a very bold assumption to make. Thankfully, it’s not a mistake they repeat in their future installments.

Seat of Power is generally a very engaging level, once one can finally wrap their minds around the little quirks about it. It has a unique pacing system, and finally introduces the player to the concept of an overarching plot. It’s just that some of its decisions on puzzle mechanics seem a little half baked- especially this late into the game.

Death Engine

Easy to get started

Sense of progress

Hints

Answers

Easily understood

Death Engine was originally set to be the game’s final send off, and as a result, the developers didn’t want to pull any punches. It was players' final trial, and they would have to put all the skills they learned in their prior missions to the test. As a result, this particular mission throws threats at the player almost as quickly as it possibly can. But that doesn’t mean that the difficulty scaling is completely unfair. It scales at a rate proportional to most of the other missions; it simply starts a few degrees higher.

Deaths in Death Engine normally come quickly. There’s little room for the player to revert any errors that they make. The agent can’t just shake off an electrocution, or being bathed in radioactive waste. However, the very first threat they encounter (a setpiece threat, rather than something caused by the player’s actions) gives the player enough time to process what the issue is, and to react accordingly. It’s the most lenient hazard in the entire mission, but still sets the tone for the level going forward: dangers will be quick and uncompromising, and going forward, a lot more unforgiving.

Death Engine also waits until the player is well accustomed to their location and the tools at their disposal before they throw the next, far more lethal timed encounter at the player, in the form of Solaris’ direct radioactive assault. Though they also have the decency to warn the player ahead of time with vocal cues. Though the puzzles are meant to test the full extent of what the player’s learned, it doesn’t feel as though the game is throwing impossible odds at them.

Though, what may seem impossible to the player is the mechanisms of their space shuttle. At a passing glance, it seems incredibly overwhelming to have all of these tools at their disposal. However, the mission actually tackles the easy to start principle in a pretty ingenious way- one that Schell would take with them into their future installments.

Yes, the player has several dials and buttons and resources at their disposal, but after the laser’s backlash ripples through your shuttle, only some of them are actually functional. While this seems to only introduce problems to the player, it actually does them a great service:

The player can only engage with one to two portions of the ship at a time- typically just one, as far as a first playthrough is concerned. True, the shuttle has a rather extensive list of information about all of its components and how they operate (a rather useful aid, and quite a good example of the answers principle coming into play again). But the hands-on experience of swapping power and seeing what new tools are unlocked is a far more effective method of communicating the rules of the stage to the player.

This use of fuse swapping also serves as another principle, in a roundabout sort of way. It communicates steady progression with each ‘fuse-specific’ puzzle solved. The gravity adjusting puzzle feels rewarding to complete in its own right, but there’s an extra sense of satisfaction that comes from ripping the fuse out of that section of the fusebox. I’m done with that, the player thinks to themself, onto something else, now.

Even Solaris aids in the player’s sense of progression to an extent, hurtling canisters of radioactive waste at them only after they’ve made a significant amount of progress. While it’s jarring to be given a new obstacle to face, a villain turning from cocky to antsy is just about the clearest tell there is that the player is making a good amount of progress. Not to mention the entire encounter turns into a (admittedly incredibly lethal) tutorial on how to actually use the shuttle’s external arm- something that will be critical to actually finishing the level.

Death Engine was meant to serve as the player’s final hurdle; the ultimatum of their career as a field operative. While it’s by no means a cake walk on a first playthrough, its puzzles remain understandable and fair. While it’s unlikely the player will make it through the level completely unscathed, the difficulty doesn’t rest at a point where it overrides the sense of satisfaction they feel by the end of the mission, as well as the end of the entire game as a whole. For a grand finale, Death Engine serves its purpose rather expertly, setting the standard for the series’ subsequent final acts.

#ieytd#wizard studies#LONG POST#LONG POST OKAY!!!! LONG POST?? FREAKISHLY LONG POST. YOU'VE BEEN WARNED DON'T BLAME ME.#i have a lot to say about the puzzles in ieytd....#missing some of the principles isn't exclusively a bad thing... like. death engine is NOT easy to understand but.#its meant to be the player's last stand... so it doesn't feel out of place for it to be complicated at first glance#you understand. you get me.#my puzzle principles....#i'm doing this to procrastinate on my homework but technically this is also helping me with my homeworl

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Birthdays 7.15

Beer Birthdays

Otto Schell (1862)

Bob Stoddard (1955)

Five Favorite Birthdays

Thomas Bulfinch; mythologist (1796)

Alex Karras; Detroit Lions DT, actor (1935)

Rembrandt Van Rijn; Dutch artist (1606)

Linda Ronstadt; pop singer (1946)

Adam Savage; television host, special effects designer (1967)

Famous Birthdays

Willie Aames; actor (1960)

Kim Alexis; model (1960)

Richard Armour; humorist (1906)

Peter Banks; rock guitarist (1947)

Julian Bream; classical guitarist (1933)

Alicia Bridges; pop singer (1953)

Guido Crepax; Italian comic book artist (1933)

Clive Cussler; writer (1931)

Lolita Davidovich; actor (1961)

Ewostatewos; Ethiopean religious leader (1273)

Dorothy Fields; lyricist (1905)

Barry Goldwater Jr.; politician (1938)

Brian Austin Green; actor (1973)

Eddie Griffin; comedian (1968)

Arianna Huffington; political opportunist, creative thief (1950)

Diane Kruger; model, actor (1976)

Clement Moore; poet (1779)

Iris Murdoch; Irish writer (1919)

Brigitte Nielsen; actor (1963)

David Pack; pop singer (1952)

Artimus Pyle; rock drummer (1948)

Richard Russo; writer (1949)

Joe Satriani; rock guitarist (1956)

Edward Shackleton; English explorer (1911)

Jesse Ventura; wrestler, politician (1951)

Forest Whitaker; actor (1961)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Intro Pin Post

My name is Emma. I have 2 cats and a bird. I enjoy reading, cooking, art, the ukulele, programming, and video games. I'm studying for CNA/GNA at Allegany College of Maryland.

My Collections: https://archiveofourown.org/collections/Astro_Boy_Fanfic_Archives

Favorite Quote:

"Humor. Two unconnected things are suddenly united by a paradigm shift. It is hard to describe, but we all know it when it happens. Weirdly, it causes us to make a barking noise." ---- Jesse Schell, The Art of Game Design: A Book of Lenses

Fandoms:

Astro Boy

Mega Man

Doctor Who

Minecraft

Rick Riordan

The Sims

Cyborg 009

Android Kikaider

Black Jack

My Hero Academia

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

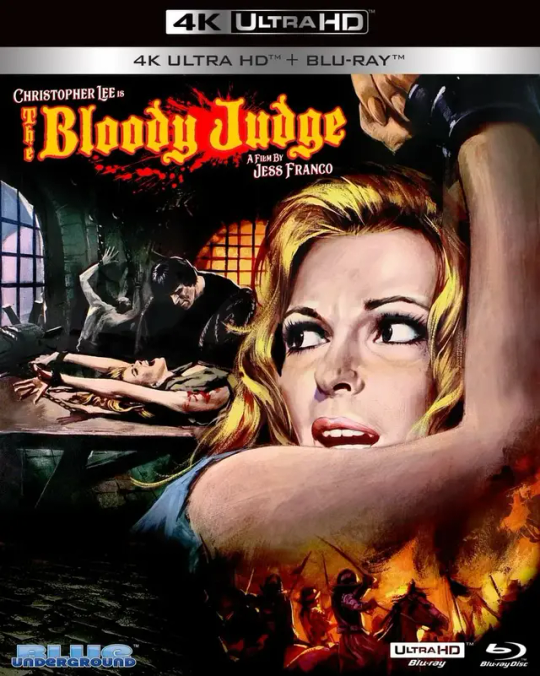

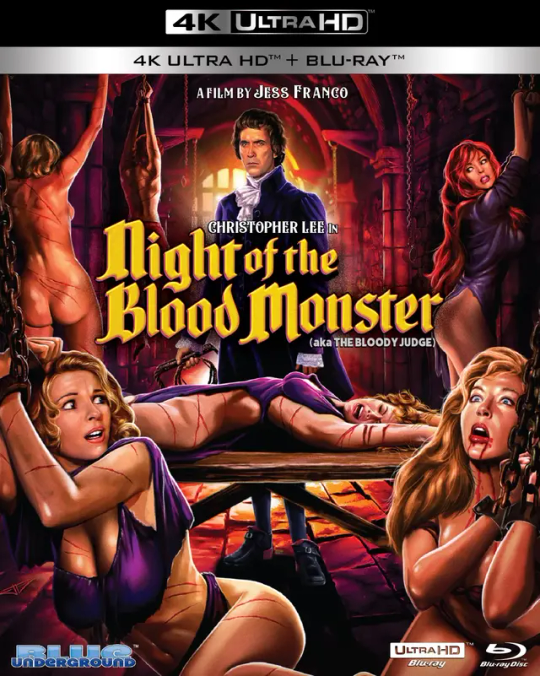

Jess Franco's NIGHT OF THE BLOOD MONSTER (aka THE BLOODY JUDGE) arrives on 4K Ultra HD + Blu-ray 4/26 from Blue Underground

Label: Blue Underground

Region Code: Region-Free

Rating: Unrated

Duration: 103 Minutes

Audio: English: 1.0 DTS-HD MA with Optional English Subtitles

Video: Dolby Vision HDR 2160p UHD Widescreen (2.35:1), 1080p HD Widescreen (2.35:1)

Director: Jess Franco

Cast: Christopher Lee, Maria Schell, Leo Genn, Hans Hass, Maria Rohm, Margaret Lee, Howard Vernon, Diana Lorys

Jess Franco's landmark epic of violence and sadism, NIGHT OF THE BLOOD MONSTER (aka THE BLOODY JUDGE), is coming to 4K UHD & Blu-ray on March 26, 2024!

Christopher Lee (THE WICKER MAN) gives one of his most unforgettable performances as Judge Jeffreys, the infamous 17th Century witchfinder whose unholy obsession with a luscious wench (Maria Rohm of EUGENIE) fuels a jaw-dropping spree of torture, brutality and flesh-ripping perversion. Howard Vernon (SUCCUBUS), Margaret Lee (FIVE GOLDEN DRAGONS), Maria Schell (99 WOMEN) and Oscar nominee Leo Genn (QUO VADIS) co-star in this landmark epic of sexual violence and sadism, complete with a superb score by Bruno Nicolai (COUNT DRACULA) and directed with spectacularly deviant glee by the one and only Jess Franco (VENUS IN FURS).

Blue Underground is proud to present the most complete and uncensored version of NIGHT OF THE BLOOD MONSTER (also known as THE BLOODY JUDGE) from a brand-new 2023 Dolby Vision HDR 4K master, painstakingly restored from various European vault elements featuring additional nudity, bloodshed and what Christopher Lee himself calls “scenes of extraordinary depravity!”

Special Features:

- WORLD PREMIERE! Brand-new 2023 4K master of the complete uncensored version

- Audio Commentary #1 with Film Historians Troy Howarth and Nathaniel Thompson

- Audio Commentary #2 with Film Historians Kim Newman and Barry Forshaw

- Audio Commentary #3 with Film Historians David Flint and Adrian Smith

- Bloody Jess – Interviews with Director Jess Franco and Star Christopher Lee

- Judgement Day – Interview with Stephen Thrower, Author of “Murderous Passions: The Delirious Cinema of Jesus Franco”

- In The Shadows – Interviews with Filmmaker Alan Birkinshaw and Author Stephen Thrower on Harry Alan Towers

- Deleted and Alternate Scenes

- Limited Edition embossed slipcover and reversible sleeve with alternate artwork [First Pressing Only]

- Trailers and TV Spot

- Still Galleries

https://mcbastardsmausoleum.blogspot.com/2023/12/jess-francos-night-of-blood-monster-aka.html?m=1

4 notes

·

View notes