#I’m afraid I will indulge in some definite crowing if the reaction to that one is at all similar

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

me seeing all the reactions to the Loki deleted scene:

#I’m trying so hard not to be a total asshole here but like#I genuinely don’t know what everyone expected#tbh I expected to hate it more#nobody’s listened to me about the coronation scene either#I’m afraid I will indulge in some definite crowing if the reaction to that one is at all similar#marvel cinematic universe#loki#Sylvie#Loki show

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Post-Bitches Brew Resistance

Miles Davis did not receive universal applause for his crossover into the Boomer world of self-exploration. Some saw his new ideas as a maneuver to erase the debt that had accumulated over the past years exploring inaccessible abstract sounds while living an extravagant life of cavorting with celebrities, traveling overseas, and maintaining a lifestyle of excessive self-indulgence.

Critic Stanley Crouch is one who associated Miles’ post-1968 with Zip Coon-nineteenth century minstrelsy. The attire that Davis acquired and the embrace of calculated gestures to Crouch, similar to the invective leveled at Bob Dylan at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival, was a betrayal to his previous association with authentic revolutionaries whose mission was to elevate the race and reject the “Uncle Tom”, “Armstrong-like mugging and grinning” for mass approval. In his 2007 publication, Considering Genius, Crouch eloquently composes these thoughts:

“Gone is the elegant and exigent Afro-American authenticity of the likes of Ellington, at ease in the alleys as well as in the palace, replaced by youth culture vulgarity that vandalizes the sweep and substance of Afro-American life. The fall of Davis reflects perhaps the essential failure of contemporary Negro culture: its mock-democratic idea that the elite, too, should like it down in the gutter. Aristocracies of culture, however, come not from the acceptance of limitations, but from the struggle with them, as a group or an individual, from within or without.” (Crouch, p. 256).

Despite accusations leveled by Crouch and other traditionalists that this music was not true Jazz, what Miles created in August of 1969 immediately resonated as it was representative of the zeitgeist that permeated culture and continues to influence our perception of life in 2019. Multiculturalism, globalism, and synthetic materialism are prominent characteristics of Postmodernism. We challenge language, symbols, credentials, and motivations of those whose authority threatens our personal identity. The need to establish individuality by definition fragments us from the whole, and our own individual whims mandate how the pieces are reassembled or not. Technology reinforces this by allowing our own imagination to define our image, and tribalism influences our choices affecting our instincts for survival. Some describe Miles as selling out, others marvel at his obsession to maintain relevance. Perhaps apropos to our postmodern perception we see what we wish to see, and his true gift was to exist on both sides of the divide. Miles as griot told the story of that moment in time by engaging younger artists and masterfully directing them with his seasoned voice. Judging by audience ovation witnessing his new direction, he converted many.

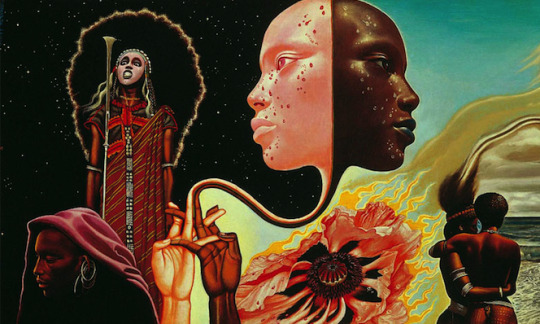

The cover that adorns his controversial 1969 project is the depiction of Black Power and Afro-centricity. The surreal art was created by Mati Klarwein, an artist who was born to two Jewish parents in pre-war Germany who fled to Palestine with the two-year old Mati to raise him in the ethnically diverse environment of Palestine.

The binary imagery: light and dark, black and white women interlocking heads and fingers, anger and peace, intimacy and loneliness, strength and weakness, bring together opposites and communicate coexistence. Miles’ choice of Klarwein’s art also reflects his own inclinations in support of icons of Black Power, Blaxploitation, and Pan-Africanism.

His reaction to the 1968 murder of Dr. King in Miles, The Autobiography reads:

“Just before we left to do these concerts [in Berkeley, California], Martin Luther King, Jr., was killed in Memphis, in early April. The country erupted into violence again. King had won the Nobel Prize for peace and was a great leader and a beautiful guy, but I just never could go for his non-violent, turn-the-other-cheek philosophy. Still, for him to get killed like that, so violently—just like Gandhi—was a goddamn shame.

He was like America’s saint, and white people had killed him anyway because they were afraid when he changed his message from just talking to blacks to talking about the Vietnam War and labor and everything. When he died he was talking to everyone, and the powers that be didn’t like that. If he had just kept talking only to blacks he would have been all right, but he did the same thing that Malcolm (X) did after he came back from Mecca and that’s why he was killed, too, I’m certain of it.”(Davis, pp. 289-290)

Having passed fearlessly into the new world of electricity, Miles continued to move forward leaving those critical of every new experiment in his wake. He followed Bitches Brew with A Tribute To Jack Johnson, the soundtrack to the 1971 documentary on the flamboyant African-American world heavyweight boxing champion from 1908-1915 and predominant Jim Crow era icon. Miles was obsessed with boxing and idolized champions such as Johnson, Joe Lewis, and Sugar Ray Robinson for their audacity and charisma. His enthusiasm for the sport compelled him to hire a trainer, and experience it as a participant.

youtube

His music betrays the intimate knowledge of this craft in his jab-like fragmented gestures, affinity for shuffle grooves like the dancing motion around the boxing ring, and keen sense of timing required to deliver his strikes with overwhelming results.

The Jack Johnson soundtrack was then followed in 1972 with On The Corner, an album whose sound and album cover go deeper into the James Brown/Sly Stone inspired psychedelic funk and Blaxploitation trend, further confounding those waiting for a nostalgic return to the 1950s. Even as these projects were released, his health and lifestyle excess were beginning to take a toll on his productivity and creative energy, and he began to withdraw into a period of retirement from music and public life altogether.

youtube

2 notes

·

View notes