#I would go on to talk about how Tim broke this cycle despite following its curves on surface inspection

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Too Dangerous for Kids

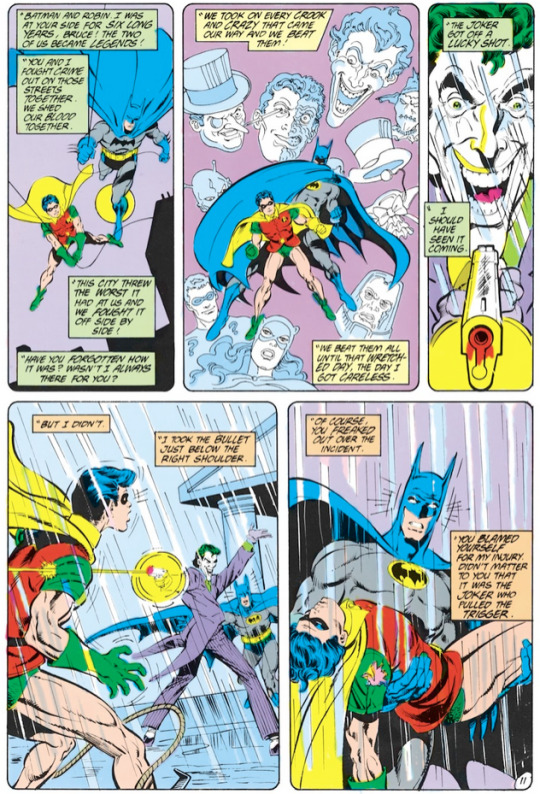

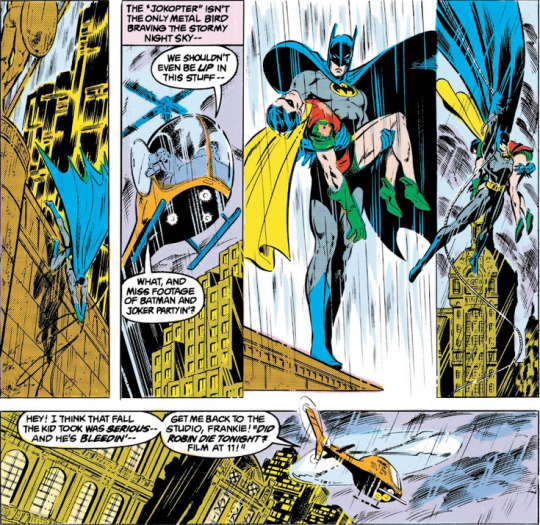

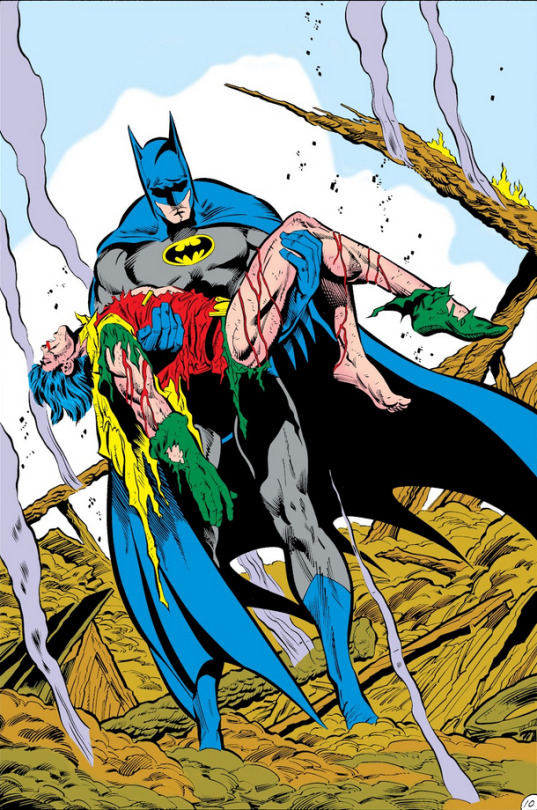

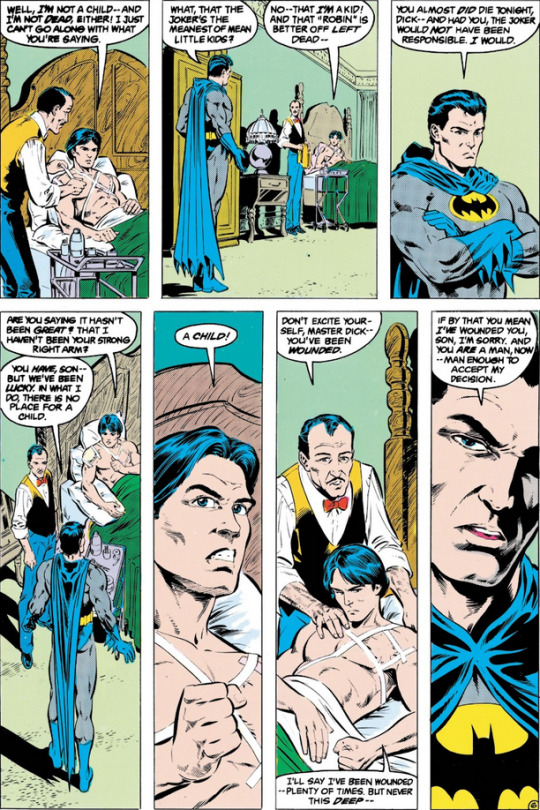

So, recently I had reason to go back and read Jason's post-crisis debut comic Batman (1940) #408 and it clicked really hard that basically the central theme of Jason becoming Robin was that Robin was too dangerous a job for kids. Before he becomes Robin, Dick got injured, badly, by the Joker, and Batman swore to never endanger another child like that, which is the reason Dick stops being Robin at all

Batman (1940) #416

And I'm friggin realizing now that the posing in Death of the Family is straight up a mirror to this scene of Dick having been shot?? I'm losing my mind???

Batman (1940) #408

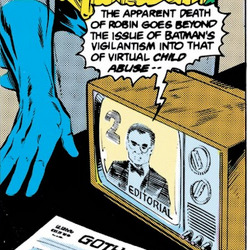

Like, look at this in universe magazine shot with this talk on the radio compared to Bruce holding Jason and tell me this was not deliberate????

Batman (1940) #408 and Batman (1940) #428

And THIS TALK?????

Batman (1940) #408

I just... HMMMM, idk there's something very fascinating to me that the theme of 'this is too dangerous for kids' has been there in Jason since day zero.

It also makes me sympathize a lot with poor Dick who got fired "cause it's too dangerous for a kiddo out there", when he was no longer a child, and then WHAT DOES BRUCE HAVE WITH HIM NOT EVEN A YEAR LATER?!

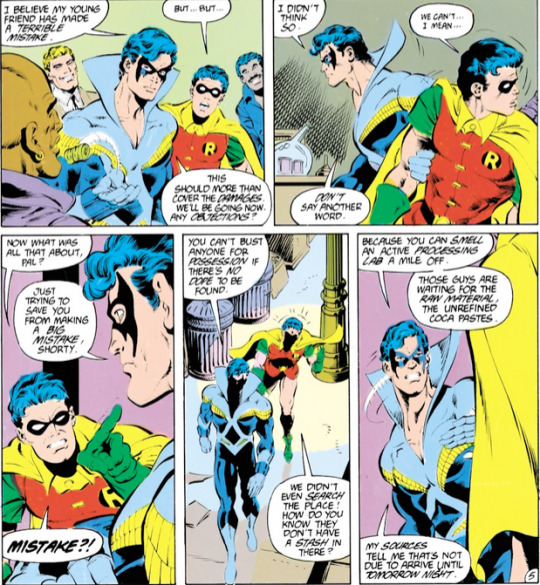

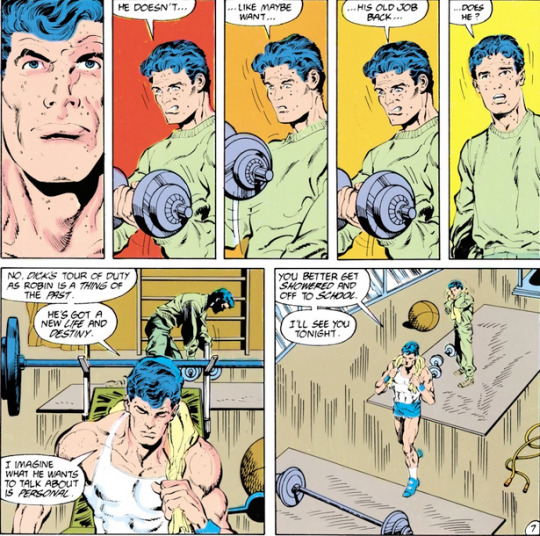

Batman (1940) #416

He's devastated by the realization there's a new Robin, then harsh and critical of the new Robin because he's sure they're gonna screw up and get hurt

Batman (1940) #416

Not because he wants his old job back

Batman (1940) #416

Despite his misgiving about the mantel being passed on at all, at the end of it, he still gives Jason his respect and acceptance into the role

Teen Titans (2003) #29

And this has such fascinating parallels to Jason's reaction to finding out there's a new Robin after him!

Red Hood: The Lost Days #4

He is devastated by the realization there's a new Robin, then attempts to brutally dissuade the new Robin from keeping the mantel because he's sure they're gonna screw up and get killed

Teen Titans (2003) #29

Not because he wants his old job back

Teen Titans (2003) #29

Despite his misgiving about the mantel being passed on at all, at the end of it, Tim still has his respect, and perhaps even his acceptance into the role, although he was far too violent about it to actually properly give the role over like Dick did for him.

Teen Titans (2003) #29

Neither of them have a petty, jealous reaction of you replaced me, but instead have a tangled mess of "I was sloppy, I wasn't good enough, I got hurt, and now you put an even less prepared child in the line of fire?!" Jason is wildly more violent about it, but at the core I feel like the sentiments are the same, and it kinda makes sense because really the end of their times as Robin were very similar to each other, just Jason's was wildly more violent!

I can't help but wonder if maybe part of Jason's reasoning somewhere along the line was "Now I finally get why Dick was so harsh on me back then." And... honestly I don't think it is. Cause while it would make sense it just doesn't seem to be a parallel either of them is conscious of.

It's just this fascinating set of reflections neither one seems to see.

#jason todd#dick grayson#important robin research#damian's tomfoolery#I am losing my mind over this#UGHGHHGHHGHH#I would go on to talk about how Tim broke this cycle despite following its curves on surface inspection#but i am already late for doing shit lmao#dick greyson & jason todd

813 notes

·

View notes

Link

via Politics – FiveThirtyEight

Graphics by Yutong Yuan

A couple of months ago, I found myself in the curious position of examining Joe Biden’s head.

On television, the former vice president comes across as perpetually tanned and coiffed — always with the aviator glasses and the crisp shirtsleeves. He still works out every morning, often lifting weights and riding a Peloton bike, and his face is still golden, his brow remarkably unfurrowed for a man of his 76 years. Up close — like, six inches up close — Biden is slighter than you might imagine. From my aft position in a press gaggle in Dearborn, Michigan, I could see the baby-pink of his scalp peeking through wisps of gleaming white hair and the faint mottling near his ears. They caught me off guard, all those fragile little human details you miss on television.

And it was a very human summer for Biden, if you’re going by “to err is human” standards. On June 18, speaking at a New York City fundraiser at the Carlyle Hotel (a swank spot on the Upper East Side where Woody Allen has a standing gig to play jazz clarinet), Biden began talking about the need for consensus-building. According to the pool report, he broke into a southern drawl as he brought up a segregationist senator from Mississippi: “I was in a caucus with James O. Eastland,” Biden said. “He never called me ‘boy,’ he always called me ‘son.’” Herman Talmadge — “one of the meanest guys I ever knew” — was another southern segregationist Democrat who Biden worked with. “Well guess what? At least there was some civility. We got things done. We didn’t agree on much of anything. We got things done. We got it finished.”

The outrage was swift. The following day, fellow White House hopeful Sen. Cory Booker put out a statement. “You don’t joke about calling black men ‘boys,’” it began, adding, “He is wrong for using his relationships with Eastland and Talmadge as examples of how to bring our country together.” Biden responded by saying Booker should apologize. “There’s not a racist bone in my body,” he said. “I’ve been involved in civil rights my whole career.”

So a month later, when a reporter in the sweaty Dearborn gaggle started by asking what Biden made of Booker calling him “the architect of mass incarceration” — a reference to his involvement with the passage of the 1994 crime bill — Biden let out a little gust of a sigh before answering. “Cory knows that’s not true.” He seemed weary of the question, and aware that it wasn’t going away.

Biden has largely led in the polls since entering the Democratic primary. Yet his front-runner status is complex: a cornerstone of his primary support is the black community — a recent poll from YouGov and The Economist showed Biden with as much as 65 percent of black support — even as his decades-long record on racial issues has transmuted into something deeply troubling to some Democratic voters. Though Sen. Elizabeth Warren has nipped at his heels in recent polls, Biden remains a peculiar front-runner — numerically indisputable yet, perhaps, fatally flawed.

Biden has a number of swirling factors to thank for his strength with black Democrats. He was President Obama’s vice president and has staked out a spot in the primary’s relatively uncrowded moderate lane — one that ideologically suits many black voters just fine. He’s also hit on a lurking note of pessimism among some black voters about what sort of person they think might be “electable” in a country that made Donald Trump president after the first black man had the job. Biden’s general election proposition, after all, involves winning over white Trump voters who some Democrats have spent the past three years accusing of racism and xenophobia.

Something about the man himself seems to be resonating with black voters, too. Rep. James Clyburn of South Carolina, a Democratic power broker, told me that Biden’s greatest asset with black voters might well be his own life story, which is strewn with personal tragedy. “We can be no more noble than what our experiences allow us to be. And black voters, by and large, see so much of their experiences in Joe Biden.”

The cornerstone of Biden’s candidacy is support from the black community and his long-standing relationships in it. In June, he attended Rep. James Clyburn’s “World Famous Fish Fry” and spoke to Rev. Al Sharpton.

WIN MCNAMEE / SEAN RAYFORD / GETTY IMAGES

But while Joseph Robinette Biden, the Irish-American speaker of self-conscious Scrantonese, is black voters’ current choice in a Democratic primary featuring two viable black candidates, there’s a sense that the winds could shift at any moment. He spent the better part of the summer relitigating his decades-long voting record. His opponents have pressed him on what they say is an antiquated outlook on race relations in America, all in an effort to chip away at his support among people of color. Prominent Democrats openly fret that he might be too old for the job. The supposed ephemera has accumulated against him even as the numbers check out nicely on paper.

The oddity for present-day Joe Biden is that he was sure America already knew him and what he was all about. But the politics of 2019’s Democratic Party can be slipshod and capricious. Its candidates are viewed more often than not through a kaleidoscopic refraction of peoples’ frustrations with the system or their anger at the president. Biden isn’t really “Uncle Joe” these days, but he presents a pretty enough picture; squint and you’ll see the halcyon Democratic era of the Obamas. If things stay that way — for black voters most especially — Biden might yet win a presidential nomination. But one or two ticks off the mark and the colors and patterns all change. Suddenly Biden could look like a wholly different man.

Biden’s current resonance with black voters is perhaps chiefly owed to Obama, a man he once called “the first mainstream African American who is articulate and bright and clean and a nice-looking guy.”

In one sense it’s ironic that Biden’s Achilles heel is the past, since a central argument of his campaign is that he can turn back the clock — but not too far back. He wants voters to remember him from the placid (by comparison) days of the Obama administration. Further back in Biden’s past, things get iffier. To that end, it is Obama’s name that Biden seems to mention most on the campaign trail — so much so that at the recent NAACP national convention, moderator April Ryan asked Biden if he used the former president as a “crutch.” (The answer was no. He then went on to talk about Obama some more.) Obama, it should be noted, is wildly popular among Democrats these days — a Gallup post-presidency poll found that he had a 95 percent favorability rating.

The continued Obama name-dropping might have seemed cringeworthy following Biden’s opponents’ critiques — verging on an I-have-black-friends line of defense — but it was also powerful. Many black voters buy the idea that if Biden was good enough for Obama, Biden’s good enough for them. Sheila Hill, an NAACP convention attendee from Arlington, Texas, was emblematic of many voters when she put her fondness of Biden in familial terms: “Joe came up like he’s a member of the family, like he might sit down and have a bite to eat, pull him up a plate, let him get some greens and cornbread. And you know how everyone was introduced? He didn’t need to introduce himself because he’s part of the family.”

A lynchpin of the Biden campaign’s strategy is embracing President Obama’s legacy whenever possible.

SAUL LOEB / AFP / GETTY IMAGES

A couple of days later, in the midst of the Booker vs. Biden news cycle, I was sitting in the Indianapolis Airport when I spotted Rev. Al Sharpton across the terminal. I was coming home from the National Urban League Conference, where I had squished myself into an uncomfortable chair to watch the crowd titter as Rep. Tim Ryan walked on stage to Johnny Cash. I had spent the morning with one ear on the speeches and one eye on Twitter, where Biden acolytes were touting a general election head-to-head poll that put him several points up on Trump in Ohio, the only Democrat ahead of the president. Sharpton had been there too, addressing the assembled members of the civil rights group.

“I think that he certainly enjoys a lot from the Obama connection,” Sharpton said, wearing a beautifully tailored suit and reclining in his seat just in front of the gate. “That’s what I think Biden’s hidden advantage is, deservedly or not: he gets associated credit for Obama dealing with Trayvon [Martin] and Obama dealing with policing commissions.”

(Despite numerous requests for this story on black voters, the campaign did not make Biden available for an interview with FiveThirtyEight.)

Sharpton, for one, seemed unsurprised by Biden’s lead over Sens. Kamala Harris and Booker. “You can’t now take the black vote for granted, and Joe has relationships,” he said. “And they’re long-standing relationships. You need a Jim Clyburn in South Carolina, I don’t care who you are.” By his estimation, Harris and Booker still had a chance to win over black voters, but their paths were far from assured. “I think that racial politics has changed — not dramatically, but to some degree — post-Obama because the novelty is no longer there.”

Sharpton, who expertly fielded the handshakes of a stream of strangers as we spoke, has himself entertained white candidates like Indiana Mayor Pete Buttigieg at Sylvia’s soul food restaurant in Harlem. He was judging the 2020 Democrats, he told me, on the strength of their platforms. For what it was worth, he liked Buttigieg’s Douglass Plan, a framework to solve fiscal and societal inequities that affect the black community.

The quiet stirring of businessmen near the gate told me it would soon be boarding time. I asked Sharpton how much time Harris and Booker had until it was too late. The end of September, he answered. “Unless of course, Joe does something absolutely off the wall,” he said, chuckling. “Which is not beyond the possible — we are talking about Joe.”

Biden has caught heat from activists for unpopular policies of the Obama administration, like deportations.

BASTIAAN SLABBERS / NURPHOTO VIA GETTY IMAGES

There’s a bookstore near my office that I sometimes browse on my lunch hour, a happy way to avoid the harsh fluorescence of office life. Over the summer, a book caught my eye: “Hope Rides Again: An Obama Biden Mystery.” The cover featured a cartoon Obama dangling from the end of a rope ladder — which itself was dangling from an airborne helicopter — while grasping for Biden, trying to pull him up. A few shelves away was the title, “Hugs from Obama: A Photographic Look Back at the Warmth and Wisdom of President Barack Obama.” While bookstores on Manhattan’s Upper West Side cater to a specific subset of America, the books’ mere existence tells a person something: a lot of Democrats still really like Barack Obama and his moderate-in-2019 policies. That’s why the lynchpin of the Biden strategy is embracing the former president’s legacy and coalition whenever possible.

Sometimes, though, that strategy can catch Biden heat. At the second Democratic debate at the end of July, he said that illegal immigrants should “get in line” and wait to enter the country legally. Julián Castro, Obama’s former Housing and Urban Development Secretary, skewered the administration’s deportation policy. “It looks like one of us has learned the lessons of the past and one of us hasn’t,” Castro told Biden in a heated exchange.

Biden faced fallout from this exchange. Activists said that he had been echoing conservative talking points, so he met with Latino leaders in person to smooth things over.

“To me that was surprising because I had written that line for Barack Obama multiple times in every immigration speech we ever did,” former Obama speechwriter Jon Favreau told me. “Even language that was, in the Obama years, approved and fine and culturally sensitive — it’s suddenly not.” (A former senior Obama White House advisor said of the debate, “On the Obama side we’re not defensive. The party and the country are in different places than we were in 2008. It would be silly to run on the exact same policies and ideas that we implemented.”)

That’s in part because of the conversation happening online. A favorite line of the Biden campaign is that Twitter isn’t real life, a nod to the fact that young, progressive, vociferously anti-Biden voices seem most amplified on the social networking site but are less representative of the broader base of the party. “We’re not going to let Twitter dictate this primary process for us,” said Symone Sanders, a senior advisor to the Biden campaign. “If we did, frankly, I think we’d spend all our time talking about 1994,” a reference to the 1994 crime bill, Biden’s support of which has helped label him as almost-Republican in certain circles.

The campaign operation has been focused instead on messaging Biden’s moderation and his close ties to Obama. On the morning of the third debate in mid-September, the campaign tweeted out a video with the caption, “Barack Obama was a great president. We don’t say that enough.” Greg Schultz, Biden’s campaign manager, wrote, “Barely a week goes by where some Democratic presidential candidate doesn’t directly or indirectly criticize Pres. Obama. The attacks are out of touch with the majority view of the Democratic Party voters.”

In order to win the nomination in a crowded race, Biden needs to cultivate support across demographic groups, to at least feint at his ability to win back the Obama coalition in the general election. His bedrock of support is black voters. Black voters made up around one-quarter of the 2016 Democratic primary electorate and are a crucial demographic group for any candidate. According to Gallup, 63 percent of non-Hispanic black Democratic voters self-identify as moderate or conservative. This, even as the Democratic Party overall has gotten more liberal — 2018 was the first year that over half of Democrats (51 percent) identified as liberal (in 1994, that number was only 25 percent.)

But while black voters have remained more moderate or conservative, white voters have become increasingly likely to identify as liberal — 65 percent of non-Hispanic white Democrats called themselves liberal and have become rapidly more liberal on issues of race over the past 10 years. With white liberals comprising a key demographic not just in the first two primary states, Iowa and New Hampshire, but also in the media, it’s no wonder that Biden’s campaign has felt the pile-on of Twitter chatter.

Yet Biden has given his progressive critics ample opportunity to say he’s carelessly retrograde when he talks about race. In early August, for example, he said “poor kids are just as bright and just as talented as white kids.” While he immediately tried to correct himself, Biden has a long-time reputation for saying the wrong thing at the wrong time. Favreau told me there was “an anxiety that lasted throughout the White House [years] — ‘will Biden say something sort of off?’ Biden’s reputation before he became vice president wasn’t ‘middle-class Uncle Joe’ and it also wasn’t too old and out of touch — it was that he was a blowhard,” he said.

While a summer of attacks hasn’t shaken Biden’s black support overall, younger black voters don’t seem to like what they see as much as older black voters. CNN polling analysis from this summer showed that Biden’s overall support from black voters is 44 percent, but his support with black Americans under the age of 50 is lower, at 36 percent. CNN modeling suggested that his support is likely less than 30 percent among black voters under the age of 30. A recent poll suggested that Warren might be making inroads with black voters. She has also gained overall on Biden in key states like Iowa and in some national polls.

Younger voters, black ones included, are concerned about issues of race and justice — things like fixing the school-to prison-pipeline, lowering incarceration rates for black men and curbing police violence. Which is why Biden’s vote on the 1994 crime bill has become such a problem and a fixation for the campaign. It might be that younger voters, who previously only knew Biden as the friendly older man next to Obama, are perturbed when they see the crime bill through 2019 eyes: mandatory life sentences after “three strikes” for federal crimes and incentivizing states to pursue harsher sentencing.

Biden, January 1990

LAURA PATTERSON / CQ ROLL CALL VIA GETTY IMAGES

Obama has reportedly expressed worry that Biden World advisors are too old school for the candidate’s good. Some of his advisors, like Sen. Ted Kaufman and Mike Donilon, have been with Biden for decades.

But younger advisors have come on board, too — Schultz and his deputy, Kate Bedingfield, are of a newer generation — and Sanders, a high-profile hire who served on Sen. Bernie Sanders’s 2016 campaign, is 29 years old. I asked Sanders, who is black, what if any advice she had given to Biden about talking to younger black voters. “I’m not going to divulge the particulars of the conversations that I have with Vice President Biden, but what I’ll say is that he and I have a good rapport, we have a good relationship and the nature of our relationship is that Joe Biden is a frank guy, he’s authentic and he speaks his mind and he empowers the people around him to do the same.”

The polls, Sanders said, bore out that Biden’s approach was working. “Anyone who purports that we don’t understand this moment or our campaign doesn’t get it — I think we uniquely understand this moment because this has been our argument from day one.”

But the crime bill remains a vulnerability for the campaign, something that engenders defensiveness from the candidate. In June, while answering a question about prison reform he brought up the crime bill, “which you’ve been conditioned to say is a bad bill,” he told the audience.

Biden has spent a lot of time in a defensive crouch about the legislation. His proposed criminal justice reform plan outlines ways to reduce incarceration, a pointed policy rebuke to the effects of the 1994 bill. But at events, he goes to lengths to defend what he calls the good parts of the bill — including the Violence Against Women Act — and his surrogates are quick to say that people are purposefully leaving out the historical context of what America was like when the legislation was passed. Clyburn — who has not yet endorsed a candidate — recalled for me a town hall meeting he had back in the 1990s in a mostly black town in South Carolina. “I spoke out against mandatory minimums, I spoke out against the crack cocaine policy. I almost got physically attacked in that place. There wasn’t a white person in the room,” he said. “To them, crack cocaine was a scourge in the African American community and they supported this crackdown.”

Biden’s grappling with his pre-Obama history is fraught, in part, because before being Obama’s vice president, he wasn’t much of a known figure in black communities. When Biden briefly ran for president in the 1988 election — a June to September endeavor that ended in a plagiarism scandal — he had little apparent appeal in the black community. A pre-scandal poll from that summer shows that he didn’t even register with black voters — he was at 0 percent while Jesse Jackson, one of the first major black Democratic candidates, had 48 percent of the black vote.

Still, hopes for Biden were high, particularly in the political media. One Los Angeles Times story from that June called Biden “the white Jesse Jackson” and noted that his opposition to federally mandated busing was savvy, “a sign of both his keen political instinct and a social imagination — a sense of the real-life consequences of government action that is rare in Washington.” Biden opposed busing because it threatened to destroy “the consensus on civil rights within the white middle class that permitted progress’ for blacks,” the story surmised. Even on hot-button issues like race, Biden was proud of his ability to foster compromise and centrism. It’s a legacy that hasn’t aged as well in a Democratic Party which is more apt to burn its one-time idols than study their historiography.

The day after the second debate, Jonathan Kinloch, a black Democratic Party official in Detroit, sat with me at a local cafe eating forkfuls of something sweet while saying something bitter: “Based on where we’ve come over these past three years and looking at the person, that Tasmanian Devil in the White House, it’s going to take another same sort of type of white man to go toe-to-toe with him.”

Kinloch doesn’t think America is going to elect a black candidate, not right now. “I’ve come to only one conclusion: Trump was elected out of eight years of repudiation for having a black man in the office. I think right now, where this country is, the flames that have been fanned by Donald Trump, we have to take a measured approach to this upcoming election.”

Biden faced blowback in July’s Democratic primary debate for his comments about fostering compromise with segregationist senators and for his stance on federally mandated busing.

BRENDAN SMIALOWSKI / AFP / GETTY IMAGES

This is the sort of electability argument that the Biden campaign can’t quite say out loud, but to which some black voters seem at least partially resigned. They might not love Biden’s semi-frequent verbal washouts but Trump in the White House grates on them more. It’s this logic, as bright and shining as their candidate’s teeth, that Biden allies allude to. Whatever his sins, whatever his prior stances, Biden’s 2020 intentions are pure — certainly purer than Trump’s. And, the theory goes, he’s got the sort of mass appeal that will talk sense into Obama voters who defected to Trump the last go-round. (Recently, a whistleblower complaint surfaced claiming that Trump leaned on the Ukrainian president to find damaging information on Biden and his son Hunter. In response to the news, Biden said that Trump was going to such extremes only because “he knows I’ll beat him like a drum.”)

There’s a risk, of course, that in trying to appeal to everyone, in refusing to play too woke, Biden risks flagging enthusiasm from black voters come the general election. The black vote disastrously didn’t surface for Hillary Clinton in 2016. There’s also some serious doubt that any candidate besides the singular first black president could inspire high turnout in the black community. In a Detroit press gaggle, I asked Biden how he planned to get Obama-era levels of votes in the black community in key general election states. I got a typically-rambling response in return. “They want to know someone — first of all, are they telling them the truth, are they laying out straight exactly what they’re going to do? No double talk. What are you going to do. And then secondly, ‘Do I believe you understand me? Do I believe you know my heart?’ I’m not a black man, to state the obvious, but I’ve gone out of my way to understand the best I possibly can what the concerns are.”

Some of the weirdness of the 2020 primary, including Biden’s leading it, is that for a party professing to be fighting for the soul of America — like, for real for real this time — there isn’t much soaring idealism afoot. It’s a contest about pragmatism. As Jill Biden put it, “You may like another candidate better but you have to look at who’s going to win … Joe is that person.”

“People are not excited, they’re not inspired,” said Anton Gunn, Obama’s former South Carolina political director. “Young people want to be inspired, everyone wants to be inspired. I don’t think we have a sense from anyone in the field that’s inspiring.”

When I spoke with Jackson, I asked what he thought about black voters’ support for Biden, his old rival. “The absence of Trump is not the presence of justice,” he said. “In the days to come I’m sure those who put forth the most hope for tomorrow and plans will gain the most traction in time. That may be Biden, but the question is wide open.”

The morning of the second debate, I met Rep. Cedric Richmond, the former chair of the Congressional Black Caucus and a co-chair of the Biden campaign, in the lounge of a downtown Detroit hotel. Various suits wandered the halls and a forlorn offering of pasta salad stood sentinel in one corner. I asked Richmond about the same thing I asked Sanders: had the campaign done any additional preparation with the candidate to ready for a new racial discourse?

“I didn’t know we had a new language on race,” Richmond answered wryly. Millennials, he went on, “are the beneficiaries of things that they don’t know they’re beneficiaries of — for example, murder was at an all time high in the early ‘90s. The streets were violent. You had children, mothers, fathers, brothers, sons being killed in the streets, you had rampant carjackings, you had drug dealing everywhere. The African American community was up in arms asking people to do stuff.”

For black voters, Richmond said, the stakes of the 2020 election were clear: “Donald Trump could be a one man end of Reconstruction.” Beating him is what matters. Dwelling on Biden’s vocabulary is just frippery by comparison.

Biden supporters cheer during the South Carolina Democratic Party Convention in June. South Carolina, with its predominantly black electorate, is crucial to Biden’s success in the primary.

LEAH MILLIS / REUTERS

Richmond told me the campaign sees a path to victory through the South, a region packed with black votes. Dave Wasserman, editor at The Cook Political Report, agreed. “I think his strengths lie on Super Tuesday,” he said of the slate of March 3 primaries a month after the very first contest in Iowa. Candidates like Warren are more likely to do well in Iowa and New Hampshire, Wasserman said. Biden campaign officials have told reporters they don’t think he needs to win Iowa, where liberal white activist voters hold sway. “But when you’re talking about a massive one-day clearance sale on Super Tuesday where it’s all about mass appeal and name recognition and strength — particularly black voters in the south, that’s where Biden really needs to hold on,” Wasserman said.

South Carolina’s Feb. 29 primary is a bellwether for Biden’s Southern strategy with a primary electorate that’s almost two-thirds black. Biden was at 43 percent in a recent CBS News/YouGov poll of the state, and it is a must-win for him. But strategists there hardly seem to think that things are sewn up for Biden. “I don’t believe polls because the same polls at this time in 2007 would show Obama was losing to Hillary Clinton by 18 points,” Gunn said. Obama would go on to win South Carolina. ”We kept organizing. Organizing is about touching people and knowing how many voters you’ve identified.” Booker’s field organization looked pretty good to Gunn, though he said it wasn’t as robust as Obama’s had been in the 2008 primary. “Definitely don’t write off Booker,” said a senior South Carolina Democrat who asked for anonymity to more freely discuss the campaign. “He has the best operation.”

I headed to South Carolina in late August, just as my inbox was signaling crunchtime of the presidential campaign slog: Buttigieg in L.A., Warren in Washington state, former Rep. Beto O’Rourke and Biden in South Carolina.

As a rule, Biden campaign events — which take place less often than other 2020 candidates’ — tend to be large affairs. His late August town hall in Spartanburg was no exception. Massive rollup American flag displays were stretched taut at either end of an echoing room. The campaign’s “Biden President” logo was slapped up everywhere. The omission of the word “for” was a not-so-subliminal message about the job he wants. A large contingent of media typed in back; a brawny blonde reporter joked with a brawny salt-and-pepper reporter about some home state sports thing.

Basically every Biden event — every 2020 campaign event for that matter — is a chance for a secular revival. And Biden is good at being churchy; he knows what to give a crowd. He can be folksy and familiar — the ghost of Uncle Joe — as well as discursive on issues of morality. When talking about guns or abortion he is most eloquent; you get the sense that Biden has devoted a whole lot of time inside his head to those topics. He starts every town hall or speech by setting the stakes with a mention of the white nationalist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017: “It shocked the whole world.”

Biden’s speech is riddled with “I’m being serious” and “seriously, folks” and “no kidding, folks,” to the point where it’s become a running joke in the press corps. I spoke with a former speechwriter of his who thinks that the “folks” tics might be something Biden has developed over time to deal with the stutter he had in childhood. “It’s how he handles transitions,” he told me.

Biden has struggled to gain ground with younger voters despite his strong showing in the polls overall.

SEAN RAYFORD / GETTY IMAGES

The childhood stutter is one of many personal details that voters have learned about Biden over the years — people have a relationship with him. Those I spoke with who know Biden all tended to say the same thing: he actually is an earnest guy. The care is real. But there’s also a carefully refined rubric of folksiness at work, all mixed with a 76-year-old’s out-of-date sensibilities. Those things can rub some people the wrong way, but both might be political strengths in the general election. “Above all else, it’s just human, it’s a storytelling voice,” Biden’s former speechwriter told me about the candidate’s preferred public voice. “It actively tries to connect with the people who are literally in front of him. Not with some kind of abstract, ethereal voter demographic or anything like that. It’s personal.” In Spartanburg, for instance, Biden talked about women deserving equal pay, but framed the problem through the lens of blue-collar men wanting their wives to be paid more. It wasn’t exactly a politically correct formulation of the issue, but its practicality rang true.

There is a gentle affect about Biden, too. When telling stories about his adult children, he refers to them as “honey” — the doting dad. Stories about his parents start with “Joey …” and suddenly he’s the adoring son. He apologizes for blocking the sign language interpreter. When he shakes hands with people, he stares deeply into their eyes — the kind of eye contact that some have called creepy but others find intoxicating coming from a very famous person. Biden has an ability to make people feel as if he has really listened. One voter I talked to in Spartanburg, Vanessa Logan, emailed me later to say that she’d asked Biden a detailed question; he had made sure his aides got her contact info so they could send her his book for a more in-depth explanation.

This attentiveness coupled with the routine vulnerability Biden shows is partially why people can’t help but be a little fond of him. “He’s down to earth, has a lot of warmth,” Sheran Littlejohn, a middle-aged black voter who came out to see Biden during his South Carolina swing, told me. “At first I thought about Kamala Harris, but then she started coming down on her own party. She went after Biden.” Somehow, even as Biden is running to protect America from Trump, he’s made voters feel like they want to protect him.

A few hours after the Spartanburg event I was at Limestone College in Gaffney, South Carolina, where it was sweltering hot even a little after 5 p.m. The only breeze came from the pep band flag twirlers entertaining a waiting crowd and the ladies in it who sat fanning themselves. Biden was running late, so I dipped into the library for a few minutes of A/C, then strolled through the crowd. I found Rosa Webber, 64, under the shade of a Magnolia tree, waiting for the event to begin with her friends from the Gaffney Women’s Democratic Club.

Webber had already made up her mind about who she’ll be voting for, come February’s primary. “If he was good enough for Obama, he’s good enough to be my president,” she said of Biden. But Anita Chambers was still candidate shopping. She liked Biden and Harris, but, “also, what’s her name? Elizabeth Warren. I like her. She’s very outspoken, very direct.”

Webber didn’t think any of the women could win, though. I asked why and before she could answer, Annette Byers, 75, interrupted: “Because the men, they’re going to do females just the way they did Hillary.” Webber agreed. “Yeah, the men are not going to vote for women. I don’t think it’s time for the women to step up.” Chambers tried to say something positive about the promise of a reinvigorated women’s movement. Byers wasn’t moved. “They will cheat her out of the election just like they did with Hillary. They will lie, lie, lie.” The conversation ended soon after, as a man with a honey-soaked accent got on the microphone and commenced proceedings.

Biden’s long career in the public eye means that voters have formed a long-standing relationship with him. This familiarity has helped him weather blunders and flare-ups throughout the campaign that might have endangered lesser-known candidates.

SEAN RAYFORD / GETTY IMAGES

Jalon Roberson, a 22-year-old senior at Limestone, said that when he and other black students talked 2020, he found most of them were still on the fence about whom to support. Roberson liked both Biden and Harris, but saw issues with both. “I like that she’s devoted to law, but a lot of her past doesn’t line up with the angle she’s taking now,” he said of Harris. “A lot of black males are going to jail, getting put away, but now she comes out and she’s like, ‘Hey, I’m for black people, I eat pork chops, blah blah blah.’ I feel like she’s trying too hard to appeal to black people. I feel like there is a way to try and come across as sincere but you have to first acknowledge that you’re an outsider and say, ‘Hey, I want to appeal to you guys.’”

Biden, Roberston said, seemed like a moral guy, a good person. But, “he was in Iowa and he slipped up and he said poor kids are just as talented and bright as white kids. And I know that’s not what he meant and that’s not how he meant it to come across, but you can tell that there is an unconscious bias.” Roberson wanted to ask Biden about how to tackle that bias.

Roberson did get a question in, just not that one. As the beginning of golden hour set in over the crowd and the hottest part of the day came to an end, Biden was taking questions from the crowd in blue-and-white shirtsleeves. “A lot of young people my age, my race, we are trying to find the incentive to vote Democratic. Why should we trust the party, and how would your administration go about holding the party accountable?” Roberson asked him.

A good question, a fair question, Biden said. He began to weave his way through the folding chairs, a meandering walk to make eye contact with students seated a little further back on the lawn. One young black man stood on a short brick retaining wall in sunglasses, a pink button-down and a hoodie. Biden made his way toward the young man while he answered, hoping to drink up some eye contact. Just as Biden approached, almost standing in front of him, the young man flipped his hood up defiantly and Biden skillfully pivoted away. A confrontational moment avoided.

The answer continued for another few minutes, and the young man kept his eyes on Biden throughout. Biden mentioned the number of incarcerated black men and the crime bill — how most black people had supported it at the time. He talked about racial profiling in Newark, New Jersey — his favorite dig at Booker. Then, “We have systemic racism in the United States of America and it’s a white man’s problem. White men are responsible for it, not black men.” The young man on the wall said, “I agree,” to that, and clapped. It was a good answer for Biden, overall. He got applause for lines about teaching prisoners how to read, positioning prisoners to get proper housing after their time served. But Jalon Roberson and the young man in the hoodie are college kids, not prisoners. It struck me that Biden’s answer wholly ignored most of the issues that the black students at Limestone and elsewhere told me they were most worried about: student debt, raising the minimum wage, the environment. Biden’s defensiveness of his past had dominated the answer. Though he did throw in a sentence or two at the end about the American Dream — “that’s why we have to rebuild the middle class and this time, we bring everybody along” — he didn’t offer any specifics.

Biden had wanted desperately to prove himself worthy to the audience of students, but a vast gulf of age and experience separated him from Roberson and the young man in the hoodie. “Let’s hear it one more time for the next president of the United States, Joe Biden!” the MC intoned over the microphone. Everyone clapped. That was that.

If Biden wins the nomination — his third attempt to do so — he will be 77 years old. The party he leads has changed rapidly during his time in public life, becoming more liberal and diverse.

JUSTIN SULLIVAN / GETTY IMAGES

I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about what Clyburn said about Biden’s tragedies. How the way he dealt with them had raised Biden in the esteem of many black voters, given the systemic hardships inflicted on them and their families over a couple of centuries in this country. Biden repurposed his suffering so it could be something more — a blessed experience, Clyburn said.

I’ve also spent a lot of time wondering why Biden ran for president this time around. He says publicly it has a lot to do with the wishes of his son Beau, who died in 2015, that he stay involved in public life. There’s ego at work, of course — it takes a massive one for a person to ever even consider running for president. But why after running for president twice, and losing soundly each time, would you do so again at age 76?

Biden might feel some sense of vocation this time around. Being a Catholic, he would recognize the Sunday school-ness of it all: what are you called to do? The way he gets fierce when he talks about winning back the Midwest, the bluster he spits when speaking about Trump’s misdeeds — it makes you think that there’s something twinging inside Biden that says, without a hint of irony, “I alone can fix this.” He wants to give people enough time to come to terms with a new American paradigm, while offering the familiar visage of an older white man standing guard. Biden sees himself as a singular salve and so do many black voters, pragmatic about the ability of America to readily accept change.

Biden isn’t alone, of course. There’s a moral imperative for each of the top three primary contenders, all in their 70s. Bernie Sanders and Warren proffer a promise of a golden, hopeful new system; Biden the restoration of one that was pretty good, if not perfect. If anything, the Democratic primary is something of a paean to old age, to lifelong ambitions and vocations yet to be fulfilled. It’s a monthslong slog as a trio of older white people bid to lead a country more black and brown than it’s ever been. I can see them — with more years behind them than ahead, in a world so different from the one they were born into — lingering longer than the rest of us over the most hashed-out lines of Tennyson’s “Ulysses”:

“You and I are old / Old age hath yet his honour and his toil / Death closes all: but something ere the end / Some work of noble note, may yet be done.”

0 notes

Text

Japan: Little Acts of Kindness in a Big World.

Here’s a confession: Before I set out for Japan, I carried a lot of preconceived notions about the country. Based on the movie Lost in Translation, I wondered if Tokyo would be too chaotic and overwhelming; if I would struggle to adjust to the unique culture and connect with the seemingly rigid locals. Based on blogs I had read, I anticipated spending a fortune on food and mainly eating out of supermarkets. Based on conversations in Facebook groups, I imagined I might starve as a vegan. Based on quirky stories I read online, I foresaw waiting at the airport luggage belt to see that my bags had been thoroughly cleaned by the airport staff!

Quirky Japan – where people carry their teddy friends to see sakura!

In this digital world, our minds are flooded with impressions created by others. Some of them turn out to be true, many of them don’t – and that was the case with Japan too.

Personally, I think that’s the beauty of travelling – it helps us break stereotypes, challenge popular perspectives and form our own impressions. And that’s exactly why to me, Lufthansa’s campaign – “Say yes to the world” – is so meaningful.

Also read: What Solo Travel Has Taught Me About the World – and Myself

Learning about Shintoism in Japan.

Time and again, little acts of kindness during my four weeks in Japan made me see the country in a totally different light than I initially expected:

The night before I set out for Japan, I serendipitously ran into Katsuyama san – the owner of Bonita Cafe and Social Club in Bangkok. He had moved to Thailand from Japan several years ago, and is a passionate vegan himself! When I shared my apprehension of travelling as a vegan in Japan, he immediately opened his laptop and spent a good fifteen minutes typing out a personal (and polite) note in Kanji (the complex Japanese script), explaining what I could and couldn’t eat. His note gave me confidence, but more than that, his instinct to help without a second thought assured me that I’d be just fine in his country.

Also read: Vegan (and Vegetarian) Friendly Cafes and Restaurants to Indulge in Bangkok

The Tokyo metro at rush hour. Photo: Tim Adams (CC)

The orderly chaos of Tokyo’s subway intimidated me at first; will I like this country? I wondered as I dragged my bag among multitudes of people rushing to their stations. At the obscure metro station closest to my ryokan, there was no elevator or escalator going up… so I slowly began lugging my bag up, when an elderly businessman, dressed in the ubiquitous navy blue suit and in a rush, stopped and gave me a hand. How could I not like that country?

Also read: Why Travelling in Japan is Like Nowhere Else in the World

A Japanese friend contemplates Ume, the plum blossom.

While on assignment for Japan Tourism, as I visited my first few Shinto Shrines, my mind was filled with questions about Shintoism, Japan’s indigenous faith. These days, Shintoism and Buddhism co-exist in Japan more as a way of life than deep teachings to contemplate. But observing my curiosity and unable to answer my numerous questions, my guide called a friend who still holds Shinto purification rituals and patiently translated our conversation – just so my curiosity could be quelled.

Also read: Secrets Behind Some of Japan’s Most Intriguing Traditions

No one does sunsets like Japan.

On the train from Osaka to Kyoto, I was tired after a long day out and quite annoyed to find no empty seats. So I just stood there blankly, when a random conversation broke out with Chizu san, a young public health student who was standing next to me. We spoke of Japan and her studies, and when she heard my name, she immediately made a connection to Shiva – the angry blue god she had seen in her mother’s book of gods from around the world! Oh, and her name Chizu means a thousand presents from god.

Also read: My Million Reasons to Love Turkey

With Tamo san in her guest house / home.

In the small town of Aso on Kyushu island, where we spent nearly a week exploring its stark volcanic landscapes, our hostess Tamo san (of Guest House Asora) invited and drove us to a local festival at the neighborhood Shinto shrine. To the sound of hypnotic drum beats, the priests rather fearlessly swung fire-lit haystacks around their heads, then invited the public to do the same. It looked pretty intimidating, so I stood in a corner watching the show from a safe distance… when Tamo san got me a stack of hay, led me by hand to where it was to be lit, and left me no option but to start swinging it. And I’m so glad she did, because it was incredibly fun and totally had my adrenaline racing!

Also read: An Unfinished Affair: Places I’d Love to go Back to Someday

Teruyuki san, in a secret forest with yellow wildflowers.

I landed up in an obscure little village of 30 people on the Kansai countryside, hoping to visit a village where three local women, each over 90 years, still ride motorbikes! Unfortunately the road to their village is under repair and I didn’t get permission to visit. Sensing my disappointment, my host Teruyuki san (of Satoyama Guest House Couture) asked me to hop into his car and drove me to his favourite, secret spots on the countryside – a 7th century wooden Buddhist temple, a 1000-year-old horse chestnut tree, a cedar forest where wild yellow flowers bloom like fire at the onset of spring. Thanks to him, I got to experience far more of the Kansai countryside than I could have hoped.

Also read: Four Years of Travelling Without a Home

Feasting on a vegan tofu platter.

At a guesthouse in Tokyo, our local host was amused when I explained my vegan lifestyle… but when I woke up, he had experimented with a vegan breakfast feast just for me: tofu steak and miso soup with seaweed dashi! Yum. And he was so impressed with his experiment that he decided to officially include a vegan option in his breakfast menu.

Also read: Why I Turned Vegan – and What it Means For My Travel Lifestyle

In love with the Japanese countryside.

While cycling alone on the Kansai countryside, I needed to use a washroom desperately but there were no public loos in sight. When I spotted a post office, I figured I might have some luck and rolled my bike into the compound. A man was hanging around at the back, and I asked if I could use a washroom – and he thankfully let me in. I later realised it was Sunday and the post office was shut; the kind gentleman had let this stranger use the washroom in his house. Just like that.

Also read: 17 Incredible Travel (and Life) Moments of 2017

Cooked up this vegan feast with Naoko san and Noriko san!

I serendipitously landed up in the home of Naoko san and Noriko san in Osaka to learn about macrobiotic vegan-friendly Japanese cooking. Although they weren’t offering a cooking class on my only available date, Naoko san made an exception and invited me to join their family for a meal, despite our brief communication online. I’m not much of a cook, but I learnt the secrets to some of my favourite Japanese dishes – including vegan sushi, creamy tofu and the most incredible avocado seaweed salad. Amid the warmth of our conversation in their traditional tatami room, I couldn’t help thinking how different Japan had turned out from anything I had imagined. For there I was, relishing home-cooked vegan food, with a local family, talking about our lives like long-lost friends…

A local cycles past Matsumoto Castle.

Has travelling changed your perception of any places around the world?

Note: I wrote this post as part of Lufthansa India’s ‘say yes to the world’ campaign. Opinions on this blog are always mine.

Connect with me on Instagram, Facebook, Twitter and Google+ to follow my travel adventures around the world!

Japan: Little Acts of Kindness in a Big World. published first on https://airriflelab.tumblr.com

0 notes