#I thought it would be mid/late 1880s when I saw it

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

so very obsessed with this

Day Dress

early 1890s

Canadian Museum of History

#I thought it would be mid/late 1880s when I saw it#but its early 1890s#aaa I love it#fashion history

1K notes

·

View notes

Note

⭐star⭐ director's commentary on any of your tga fics please! either the published ones or the ones hidden away in your dragon's hoard, i don't mind :)

i choose this one :-)

i think my fav thing about writing oscar is that i do not perceive him to be a reliable narrator, & this piece is no different in that regard — i think from what we see in canon oscar is actually really good at Consciously coming to conclusions that simply do not make sense! separate from his attention span or anything like that — he assumes he has all the requisite information, whether or not he's taking things at face value, and he operates under those assumptions

but he doesn't see them as assumptions, he sees them as Facts. and so when he thinks he knows what is going on, he does acknowledge this, and the acknowledgement in and of itself makes it Real and he doesn't need to give any more thought to it because that would be a waste of time when there isn't further information he needs to be Right.

& then in general oscar always leans toward the outcome that makes the most sense for him and gives him the most benefit, even if further thought would probably lead him away from that conclusion.

obviously he is not exempt from wallowing, he does wallow and consider, but like, john is Guy Who Broods and oscar reallyyyy is not there .

and in this fic they are both like, mid 20s, not quite where they are in canon, and so one of the ways i wanted to toe into this is that oscar is even more forthright with his #affirmations than i think he needs to be as a well practiced jumper to conclusions in canon — he needs to tell himself he knows what is going on, whereas i think by the time we are in the 1880s, in this manifestation of him, he can skip that conscious step more often than not

so i wanted to play with that for one thing!

and then

Lately there had been weeks where John hardly saw his own bed, let alone slept in it. Months ago Oscar had taken to keeping additional various toiletries and necessities entirely for John's sake—his preferred tooth powder and shaving cream and the implements required for each, among others. A set of laundered undergarments, just in case. All of it was ridiculous, but ridiculousness such as this had an obvious and uncomplicated remedy. The difficulty would be that John had made it very clear that he found comfort and convenience in the arrangement—he of course had done likewise in his own rooms—and neither sought nor desired anything more. Indeed he had at times insisted upon it, going out of his way to ensure that Oscar knew he was satisfied, that this was enough, and that he thought Oscar's provided conveniences were exceptional, far more than he needed—by telling him all about it in plain and eventually repeated English. If the man was going to resist—clinging to how things were, and refusing to make any strides in changing them—he wouldn't really compromise, he was always discontent to do so, just as he was discontent with anything and everything his neighbors at dinner parties found out of the ordinary or disagreeable or dishonest... But he was different, with Oscar. Honest. Transparent. Unwilling, or more likely unable, to hide his true feelings for very long... Well, Oscar didn't know what he would do.

& then i just think this is so funny...... oscar is sooooo close here to Getting It, he is rapidly developing an understanding of him and how he operates and in this timeline has honed it over two years of being with him, like he Knows John by now. but also he has some underlying insecurity about what he wants, which is very new to him and he knows it, and why/how he wants it, and is very self-oriented, and so he like. does not parse that john has been telling him bullshit for months because john doesn't want oscar to leave him for being needy fjfjkskdjfkskd

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Abridged history of early 20th century Chinese womenswear (part 1: 1890s & 1900s) *improved version

Source here

*I’m fixing and reposting the first two posts of this series because back then I had no idea how Tumblr formatting functioned and they deserve better. I’m keeping the shoddy original versions for archival purposes.

*After some thought I think it makes more sense to group the 1890s and 1900s together.

Other posts in the series:

Part 1: 1890s (original)

Part 2: 1900s & 1910s (original)

Part 3.1: 1920s-silhouette

Part 3.2: 1920s-design details

Part 3.3: 1920s-accessories, hair & makeup

Part 4.1: 1930s-silhouette & design

Part 4.2: 1930s-hair, makeup & accessories

Part 5: 1940s

Part 6.1: 1950s-Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan & friends

Part 6.2: 1950s-mainland China

Intro & context

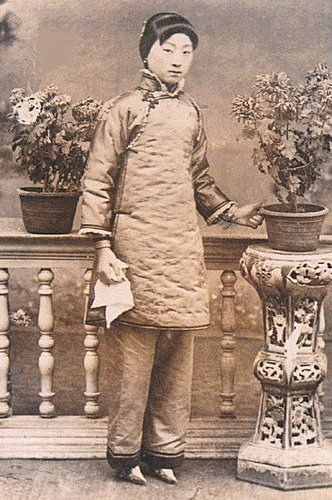

In order to understand early 20th century Chinese fashion we have to go back a bit into the past to have some clue about the context. When the Manchus conquered China and established the Qing Dynasty in the mid 17th century, Han Chinese men adopted Manchu style clothing but Han Chinese womenswear remained independent and separate from Manchu womenswear. Han Chinese women retained the habit of wearing a two piece ensemble as the outermost layer, unlike Manchu women, who wore a single floor length robe. I will be only discussing Han Chinese women’s fashion in this series.

In the 19th century, Han Chinese women wore 袄裙 aoqun, a two piece ensemble consisting of a robe and a skirt. The robe had a very low 立领, standing collar. In the second half of the 19th century, the robe in aoqun had a very generous and roomy cut and huge sleeves, a look which reached its peak in the 1860s and 70s. The hem of the robe hit the knees, the length in vogue since the 1870s. The collar of the robe is very low, only providing enough space for one button, likewise in fashion since the 1870s. The robe is closed with 盘扣 pankou, which in this era were always plain with either a bead or fabric knot tip. The robe closes at the side, usually at the right side at the 大襟 dajin, the side closure, however examples of robes with closures on the left also existed. Robes with closures on both the right and left were also a thing, a style called 双襟 shuangjin, double closure. Shuangjin robes were derived from a men’s riding vest, the 巴图鲁坎肩 batulu vest (batulu is Manchu for “warrior”), that could be opened from both sides, and would experience a revival in the 1920s.

Source here

1870s/80s photograph of a group of women in aoqun, the two skirts on the left are the elaborate mamian style, the one on the right is plain.

In aoqun, the skirt was usually of a style called 马面 mamian, made of two long horizontal pieces of pleated fabric with two flat sections each sewn to a waistband with one flat section overlapping, creating a wrap skirt that once worn around the wearer’s waist, appears to have two unpleated sections, one at the front and one at the back. This skirt was very decorative in the 19th century, full of embroidery, tassels and elaborate trim, sometimes giving the illusion of a separate apron being attached (I’ve seen this weird stereotype that traditional Chinese womenswear has a separate apron at the front this is complete bogus). The robes were likewise heavily decorated around the seams, ceremonial outfits like wedding gowns could be so full of embroidery that the original fabric is hardly to be seen.

The combination of robe and pants, 袄裤 aoku, was also a common way of dressing since approximately the 1800s or 1810s. This combination would become the norm in the 1890s.

Source here

1870s/80s photograph of a woman in a ginormous ao, roomy pants and with bound feet.

Another noteworthy fad was bound feet. The middle of the 19th century was the pinnacle of foot binding and fashionable women had incredibly small feet, dubbed “lotus feet”. This was achieved by wrapping tight foot binding cloth around the feet since childhood and restricting the growth of the feet, I think also breaking a couple bones in the process. Women wore foot binding cloth and baggy stockings underneath their shoes, tied up with garters below the knees. Foot binding is said to severely restrict mobility and cause intense pain; I don’t doubt the pain part but I’m not sure about mobility since I’ve seen plenty of photographs of women with bound feet roaming about the streets.

Not every woman did foot binding though, it depended heavily on region, class and the individual family. For one, Manchu women all had natural feet. For Han women, an account from the 1850s said that in Beijing, every five or six out of ten women did not have bound feet, and that probability is three or four out of ten in the countryside. In the provinces along the southern coast, most women did not bind their feet (this probably has to do with the influence of indigenous cultures in the south, since foot binding was primarily a Han fashion), whereas in the northwest almost every woman had bound feet. By the way, I really don’t like how articles on foot binding describe it in the most sensational way possible, why is it so hard to approach history with peace of mind? And it pisses me off that all the articles containing 1890s photographs only talk about the foot binding as if there is nothing more of value in portraits of whole ass women.

Anyway, if you are interested in learning more about foot binding, check out Cinderella‘s Sisters: A Revisionist History of Footbinding by Dorothy Ko, recommended by @thefeastandthefast . Or just anything written by Dorothy Ko tbh.

Silhouette

In the 1890s, the cut of the aoqun began to become more slender and form fitting, commonly believed to be a result of westernization. But I think it’s also because the wide sleeve look has also been in fashion for quite a while now (some 80 years or so) and people were getting tired of it. The robe inherited the knee length hem from the 1880s but was less baggy and took on a more straight cut silhouette. The collar remained quite low until the end of the decade. Pants were overwhelmingly more popular than skirts in the 1890s, I speculate this may be due to a rising interest in feminism and women wanting more mobility, but aoku was also very popular in the 1870s and 80s in general so it may have also just carried over. The pants were still ankle length and straight cut but less roomy than earlier 19th century models. Overall the 1890s just looks like a shrunken and simplified version of the 1880s.

Source here

The aoku as of the 1890s.

By the second half of the 1900s, the collar began to rise, becoming medium height. This was kind of reminiscent of late 18th century Han women’s collars I mentioned in this post on Chinese standing collars. The robe and pants shrunk further, becoming quite tight fitting. The robe was still around knee length. The pants were especially tight and could be considered skinny. Foot binding became less common and many women had natural sized feet. However, since foot binding is something that begins in the childhood, the fact that many women without bound feet appeared in the 1900s meant that many parents started to reject food binding in the 1880s and 90s.

Source here

Ca. 1907 photograph of a group of women, possibly students, in tight fitting aoku.

Design details

The 1890s saw the mass disappearing of wide, embroidered trims around the seams, popular throughout the 19th century. The use of multiple rows of binding/trim from the 1870s and 80s was continued, albeit in a much more minimalistic and geometric way. I’ve seen a lot of plain white ao finished with multiple rows of black binding of different widths, it’s mighty avant-garde and elegant. Because clothes of the era were still constructed in the older Chinese method, they had a seam down the middle of the sleeves used to extend the length of the sleeves; this seam could be bound and decorated but it was not compulsory. Actual embroidery on the robe and skirt/pants was rare, if not non-existent; completely plain fabric was the norm. The ao of this era commonly had a 厂字襟 (厂 shaped closure), where the front placket is held up by one or two buttons and then closed by more buttons down the side seam. This style of closure was first popularized for Han women’s clothing in the 1800s and 1810s, before that Han women’s clothing closures were a straight line from the collar to the armpit. The pankou used to close the ao of this period became a lot more elaborate and the main source of decoration; I have a whole ass post on them here. A general air of simplicity, comfort and proportionality dominated the fashion of this era. In the mid 18th century, Han women’s robes started having folded cuffs (possibly borrowed from Manchu court dress), called 挽袖 wanxiu, and these became fake and represented by a piece of trimming in the 1850s. By the 1890s this design feature largely disappeared, leaving the sleeve edges either plain or simply bound.

Source here

Three women in aoku, late 1890s. I looooove the look on the far left, I will probably make it some day.

Going into the 1900s, the geometric trims became more simplified and austere, while the pankou became increasingly ornamental.

Source here

Late 1900s photograph. The robe is trimmed with fur and thin, geometric binding, and closed by very ornamental pankou.

Hair & Makeup

There were no significant changes in hairstyling in the 1890s, fashionable women would wear existing 1880s hairstyles but style them with bangs. A common style I’ve seen in photographs was long hair pulled back into either one big bun at the back or two smaller ones at the sides. The short bangs were usually very neat, precisely cut and sat closely to the forehead. Elastics did not exist, so Chinese women used strings and hairpins to tie their hair together. Hairpins of this era were usually very thick and sturdy, a single one was enough to hold all your hair into a bun. It was popular to use flowers and/or pearls to form a ring of decorations around a bun.

Source here

Common 1890s hairstyle, for most people the decorations weren’t so elaborate.

A popular headpiece was this thin headband adorned with pearls worn at the place where bangs should be, although that has been around since the 1870s as well.

Source here

Ca. late 1890s. Some women wearing the pearl headband.

Around 1905 the bangs began to grow in length but still weren’t long enough to cover the eyebrows. They were longer at the sides and shorter in the middle, creating this volume and curve at the forehead.

Source here

Photograph ca. 1905. Long bangs.

By the end of the decade these evolved into a being with a will of its own. Long hair tied into braids or low buns became fashionable instead of tight, high buns.

Source here

Calendar painting from 1911.

Fashionable women in the 1890s wore little to no makeup, because of the influence of female university students who were usually without makeup. In the 1870s and 80s, thick makeup was more common and was a trend popularized by sex workers in Shanghai, thus becoming increasingly considered indecent in the 1890s. I find this quite problematic cause respectability politics suck and there’s nothing wrong with wearing fashion trends invented by sex workers. All the straight male writers of the 1890s and 1900s praising female students for being “pure” and ”hygienic” in contrast to the supposedly nasty sex workers make me cringe to my core, it’s just pitting women against each other and setting us up for “I’m not like other girls” in my opinion.

The common makeup look includes white power, lipstick and blush. The lipstick shape was usually a tad smaller to the actual lips and blush was applied in large areas toward the outside of the face.

Source here

Standard 1890s and 1900s hair and makeup look. This drawing is probably from around 1902, it’s a bit more festive folk art than fashion plate so take the patterns with a dash of salt.

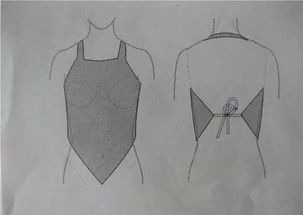

Undergarments

Unfortunately I don’t have many pictures for undergarments of the era but I can describe them to you. Since women commonly wore pants, they would usually wear another layer of pants (could be considered drawers) underneath that was of a similar construction but plain and easy to launder. Panties and such didn’t exist so drawers were the innermost layer, enough to protect women’s private parts. Likewise for the robe, another plainer, sturdier version would be worn underneath. In the mid 1900s, as the sleeves of the outer robe began to shorten, the undershirt became more form fitting at the wrists and could serve a decorative function.

Chinese women in the 19th century bound their breasts with long strips of fabric to achieve the flat look. I’m not exactly sure how this is done but basically you wrap fabric tightly around your chest until the boobies are concealed. A famous undergarment of the Qing Dynasty was the 肚兜 dudou, which was actually unisex. The female only version was called 抹胸 moxiong, 袜肚 wadu or 袜腹 wafu, the latter two are etymologically similar to earlier words for “corset” or “a pair of bodies”. However, unlike what many later 20th century artists would like you to believe, wearing only dudou on the upper body was not legit underwear for grown up women, as it was usually worn in conjunction with breast binders as an extra layer of warmth. It was also worn very tightly around the breasts and waist, not tied loosely like in paintings or period dramas nowadays.

Source here

Dudou diagram.

Shoes

Women began campaigning against bound feet in this period and many drawings depicted women with natural feet. However, if a woman had her feet bound since childhood it’s difficult for them to return to their natural size, so some women who were born in previous decades would still have very small feet, even if they began to reject it at this time. Women’s shoes of Western construction weren’t yet so common so most women wore Chinese style shoes, which were commonly made of fabric and had a slightly upward pointing toe. Women with bound feet would use a long piece of ribbon/cloth to wrap their feet (to maintain the shape) and wear small fabric pumps with a white sole. These could be flat or have a teeny tiny bit of wedge heel, called 弓鞋 gong xie, bow shoes. Women without bound feet would wear normal sized pumps, likewise of fabric, with slightly upward pointing toes and a thick white sole. Embroidery on shoes was a huge thing in the 19th century and before but by the 1890s it started to disappear as well, and shoes in the 1890s were commonly plain. In the 1900s, Western leather shoes were increasingly popularized, but it wasn’t until the early 1910s that this popularity reached its height.

Source here

Foot binding cloth.

Source here

Shoes for bound feet.

Source here

Woman with natural feet wearing Chinese style pumps. Western style knit stockings were becoming popularized in the 1880s for women with natural feet as well.

Some editing afterthoughts

I’ve been looking more into 18th and 19th century Chinese fashion lately and I realized I held some deep rooted misconceptions about the Qing Dynasty. For some reason I always considered the 1870s and 80s look with the elaborate, big robes conservative or backwards, which is really not fair. Chinese women’s fashion was revolutionized in the beginning of the 19th century, going from the flowy, slender robes of the 18th century to stiffer, more structured robes with flared sleeves. Styles also differed dramatically from decade to decade, it’s just not very well studied and there’s a stigma around Qing Dynasty fashion so people don’t get into it as much. Because Han women were allowed to continue wearing Han style clothing into the Qing Dynasty, a lot of 18th century reproduction ensembles nowadays get mistakenly labelled as Ming style hanfu, which really isn’t helping... I was definitely not alone in this though, the perception of Qing Dynasty Han women’s fashion most people nowadays have is: in the first couple years Han women were allowed to wear Ming style hanfu, but then bam the late 19th century look was forced upon everyone. This view is super not nuanced and false on almost every level, but it is extremely widespread and I don’t blame you at all if you also think like this, this was me just two months ago too... A wise woman (I mean Karolina Zebrowska) once said that everything in fashion history happens gradually, which is also extremely true for Chinese fashion history.

I’ve really started to question what modernity in fashion means because the elaborate 19th century Chinese look that white people back then considered the epitome of conservative Chinese clothing was actually new and exciting in the beginning of the 19th century. I can’t help but wonder if this view that Chinese clothing as of the 1870s and 80s was symbolic of Chinese culture’s “backwardness” and “stagnation” was a product of colonization and white imperialists’ efforts to demonize Chinese society and take things out of context. I would prefer to say that Chinese fashion westernized a lot during the 1890s and 1900s but not necessarily modernized because what is modernity. Fashions change and that is the most normal thing on the planet.

If you read what white historians or politicians wrote in the late 19th/early 20th century about Chinese fashion or culture (which I highly recommend you don’t, that shit is detrimental to your mental health), it becomes obvious that the majority of them have no clue what Chinese fashion looked like before the 19th century and how we got to what we had in the 19th century in the first place, so they just assumed that Chinese fashion always looked like that and that we haven’t progressed as a culture in hundreds of years lmao. Bullshit pseudo-Darwinism at its finest. Oh or if you look up 18th century European Orientalist paintings depicting imaginary Chinese characters, the clothes they wore and the hairstyles they had were so far off from what actual 18th century Chinese fashion looked like to the point they felt racist and were uncomfortable to look at. I stumbled across so many of them when looking for 18th century Chinese painting and every time I see one it almost gives me a stroke. So I think it’s really important to acknowledge that Han Chinese fashion of the 18th century is a valid field of study.

In my original 1890s post I said that the elaborate embroidery and trimmings started to appear on Han women’s fashion around this time because of Manchu influence, I take that back because I’ve realized it’s a whack claim. I’ll explain it more when I make some posts on the 19th century later.

Reworked part 2 is coming soon as well :)))

#1890s#1900s#19th century#historic fashion#qing dynasty#vintage fashion#vintage hair#vintage shoes#chinese fashion#chinese history#abridged history of early 20th century chinese womenswear#清汉女装#edwardian fashion

419 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Time Arrangement

Pairing: Professor Charles Blackwood x College TJ Hammond

Words: 1880

Warnings: Professor/Student relationship, smut, oral sex (m rec), dirty talk, praise, cursing, slight degredation and name calling (slut), TJ is mid 20s’s and Charles is mid-late 30’s.

A/N: Written for @the-ss-horniest-book-club Long Distance Love weekend! One of the prompt ideas was college AU, and I wanted to write character student this time, so this seemed like a perfect opportunity to write these two together😏 Thanks for reading!❤

Dividers by @firefly-graphics

I do NOT authorize my work to be copied, translated or reposted in ANY way.

18+ ONLY. This post contains mature subject matter. By clicking ‘keep reading’ you agree that you are 18+. Do not interact if you are under the age of 18.

TJ arrived to class a split second after the bell rang, slipping through the door just as it was closing. He hurried to take his seat a few rows back in the lecture hall, hoping his prof wouldn’t notice.

If he could be so lucky. Professor Blackwood stood at the front of the hall, waiting not so patiently for everyone to settle down, starting into his lecture less than a minute after the bell rang, expecting everyone to be ready to start at the sound of the bell. That is when the class began, after all.

After a few opening remarks and introduction of the day’s topic, he paused, critical eyes scanning the room. TJ gulped, hoping he’d escape his professor’s wrath today, but those icy blue eyes paused, lingering on TJ’s own, making him shift uncomfortably in his seat. Dammit. TJ squirmed, fidgeting with his pen and finally crossing his legs, and he swore he saw the briefest hint of a smirk before his professor turned away, starting into the lecture.

TJ could barely concentrate, but he did his best, trying to take notes and focus on the lesson. Before he knew it, the 90 minute period was over and the bell was ringing again. He packed up his things and stood to leave the hall, Professor Blackwood’s voice cutting through the mulling of students as TJ neared the door, sending a tingle down his spine. “Mr. Hammond. I expect to see you at my office at 4pm to make up for your tardiness.”

Shit.

TJ shifted anxiously on his feet as he stood outside the large oak door, checking his phone until the time read exactly 4pm, before knocking lightly on the aged wood. This wasn’t the first time he’d met his professor in his office, but his nerves nearly got the best of him every time. The door swung open with force and TJ started, Professor Blackwood’s piercing eyes meeting his for just a moment before he stepped back, walking towards his desk. TJ followed him in and closed the door, flicking the lock, before stepping in further. He paused in front of the large wooden desk, nearly an antique, and clasped his hands together.

“So,” his professor, Charles, started. “Late again today, Mr. Hammond.” TJ nibbled his bottom lip, not having a good excuse whatsoever. He’d overslept, dashed to class and literally ran through the hall to make it on time, and still ended up missing the bell. Fraction of a second or not, in Blackwood’s class, late was late.

“I’m sorry, Professor Blackwood, sir,” TJ started, holding Charles’ gaze despite his nerves. Charles sat back in his chair with a hum, fingers steepled, keeping his eyes locked on TJ's with the slightest smirk on his lips. He’d removed his suit jacket that he’d worn earlier, it hung neatly on a coat rack by the door. The calm nature in which he held himself both intrigued and terrified TJ. He never knew what to expect from this man.

“I’m sure you are,” he drawled. “Did you even catch any of the lecture today, or were you too distracted?” TJ winced; he’d tried to pay attention, but the glare he’d received at the beginning of class had thrown him off, and Charles knew it. He’d done it on purpose.

“I was listening, sir, I -”

“Well why don’t you go over the main points then,” Charles suggested, his tone a little darker, knowing that TJ wouldn’t be able to recall all the points off the top of his head.

“Sir, I - I haven’t had time to review my notes.” “Ah. Of course not.” He paused, tapping his fingers together, clearly enjoying the way his gaze made TJ squirm. “Do you have something else in mind then, Mr. Hammond?” TJ’s gaze flicked back up to meet his professor’s, the blush already creeping up his neck to his cheeks as he nodded slowly. Yes, he did have something else in mind, but he wanted Charles to say it, just like he did every time TJ made an office visit.

TJ just nibbled his lip, wringing his hands together and dropping his gaze again. He knew Charles loved it. Loved the little back and forth, the hard to get, the innocence ploy that TJ was so very good at. Charles clenched his jaw and raised an eyebrow, playing his own game that made TJ’s cock twitch. Oh how he loved it. But he wouldn’t dare ask for it, this was always in Charles’ court, in his control.

It was exactly what TJ wanted.

“Come here.” It was a command, a lower and more stern tone than he would ever use in class, and TJ swallowed hard as the sound rolled through him, making his skin prickle. He walked slowly towards the desk, stopping around the side just a few feet from Charles. The other man just smiled, his eyes flashing, his low voice rolling through TJ again. “Closer, Mr. Hammond. What are you doing way over there.” TJ bit his lip hard to hold in the groan, stepping closer still until he stood between Charles’ spread thighs. Oh the thoughts he’d had about these thighs. It was sinful.

“Now,” Charles began as his hands moved to his belt. “What if you put that pretty mouth of yours to good use, hm?” Slowly, painfully slowly, he opened his belt, undoing the buckle, sliding it open and letting it drop, his hands now reaching up to his tie. Dark lashes practically fluttered as he loosened it, and TJ nearly groaned again, feeling the heat pool between his legs. Something about Charles and his fingers and they way moved so smoothly, nimbly, TJ would be lying if he said he hadn’t thought about those fingers either.

With a shy, sultry smile, TJ slowly sank down to his knees between Charles’ legs, placing his hands on toned thighs and sliding them upwards. Charles was looking down at him now with a possessive glint in his eyes, watching as TJ’s hands ghosted over his crotch, lightly brushing over the bulge in his pants, before undoing the button and slowly pulling the zipper down. TJ palmed him through his underwear, biting into his bottom lip again as he pulled the waistband down to free Charles’ impressive length from the confines of the fabric. He licked his lips then, glancing up at Charles through his own dark lashes, pulling the perfect puppy dog eyes that he knew the other man loved.

“Look at you, so eager…” Charles mused, his voice trailing off as TJ leaned in, licking a stripe up his cock and pulling a groan from him as he closed his lips around the red, aching tip. TJ knew Charles loved his mouth on him, he’d done it enough times to have already figured out what his professor liked. Sometimes he wished they could have more time, the opportunity to explore each other further, and really find out what drove Charles wild.

TJ licked over Charles’ length again before swallowing him down, pulling another deep moan from the other man, sending a shiver straight to his own cock, already straining in his jeans. He moaned around him, and Charles rolled his hips up further into TJ’s mouth in return. When he bumped against the back of TJ’s throat, he just hummed, breathing through his nose as he swallowed around him, Charles muttering curses above him.

“Shit, you’re far too good at that…”

TJ’s hands wandered further up Charles’ thighs, squeezing and massaging, and as they neared his hips, TJ wished he could grab Charles’ ass, his naked ass, and pull him deeper, wondering what it would feel like in his hands. He moaned at the thought, causing Charles to jerk his hips forward. TJ looked back up at him as he swallowed around him again.

Watching Charles fall apart for him, from just his mouth, filled TJ with pride, it excited him. He wanted more, he wanted Charles to fuck him over the desk, he wanted to sit in his lap, he wanted to be in his bed. He wasn’t sure how far this might go, but he’d blown him before, and every time it made him rock hard, and Charles would cup his face and brush his cheek and tell him how much of a slut he was, on his knees getting hard without being touched. TJ loved it.

Charles’ hand found it’s way into TJ’s hair and tugged, TJ moaning around his cock at the slight pain. Harder. He doubled his efforts and was rewarded with the hand clenching, pulling deliciously on his hair, digging his own fingers into his professor’s thighs. Charles groaned, leaning his head back and bucking further into TJ’s mouth.

“You and that mouth, it’s so goddamn good. You like when I use it, don’t you. That’s why you keep showing up late for my class. You just want me to fuck your pretty mouth like this.” TJ whined around him, saliva starting to run down his chin. He was sure he looked like a mess, but Charles’ words were making him hot, so hot, his hips started jerking too, wishing he had some friction to relieve himself.

He glanced up at Charles and moaned again at the sight. Cheeks flushed, lips parted and eyes closed. His usually well-styled hair had fallen loose, a few strands falling into his face, and TJ longed to run his hands through that caramel hair. When Charles spoke, his voice was a deep, gravelly tremor that shot straight to TJ’s gut, but seeing him sitting there panting, almost on the edge of orgasm, it made TJ desperate to cum too. He wanted to beg for it, but it was impossible with his mouth full. So he just whined, shifting at Charles’ feet, gripping his thighs again.

“Oh yeah baby, there it is, keep going, you wanna come too? My dumb little slut, on his knees just begging for it. So fucking good, come on, ah!” TJ sucked hard at Charles’ words, feeling a heat rush through him and he bucked his hips, nearly cumming untouched, as Charles came with a groan, straight down TJ’s throat.

He couldn't help the ways his hips rolled while he curled his tongue, still sucking gently, his cock painfully hard, while Charles rode out his orgasm. TJ wanted it too, moaning around him, the sight of this gorgeous man getting off making TJ hot beyond words. He couldn't wait to get his own hands on himself, fueled by thoughts of what he wanted Charles to do to him. Lost in the fantasy, he was quickly pulled out of his daze by Charles' low voice, and he blinked up at him with glassy eyes while licking up the last of his release.

“Look at you. I’m starting to think this is more of a reward for you rather than a punishment. That just won’t do anymore, rewarding you for being late.” Then he leaned forward, gripping TJ’s chin and wiping the mess from the corner of his mouth with his thumb, his words sending a delicious chill down TJ's spine. “If you ever want this again, I suggest you be a good boy and show up on time for my class."

* follow @nano--raptor-writes for my taglist! *

#hbc long distance love weekend#tj hammond#charles blackwood#professor au#college au#tj hammond x charles blackwood#charles blackwood x tj hammond#tj hammon smut#charles blackwood smut#crackship

38 notes

·

View notes

Link

In the third decade of the 21st century, the Social Register still exists, there are still debutante balls, polo and lacrosse are still patrician sports, and old money families still summer at Newport. But these are fossil relics of an older class system. The rising ruling class in America is found in every major city in every region. Membership in it depends on having the right diplomas—and the right beliefs.

To observers of the American class system in the 21st century, the common conflation of social class with income is a source of amusement as well as frustration. Depending on how you slice and dice the population, you can come up with as many income classes as you like—four classes with 25%, or the 99% against the 1%, or the 99.99% against the 0.01%. In the United States, as in most advanced societies, class tends to be a compound of income, wealth, education, ethnicity, religion, and race, in various proportions. There has never been a society in which the ruling class consisted merely of a basket of random rich people.

Progressives who equate class with money naturally fall into the mistake of thinking you can reduce class differences by sending lower-income people cash—in the form of a universal basic income, for example. Meanwhile, populists on the right tend to imagine that the United States was much more egalitarian, within the white majority itself, than it really was, whether in the 1950s or the 1850s.

Both sides miss the real story of the evolution of the American class system in the last half century toward the consolidation of a national ruling class—a development which is unprecedented in U.S. history. That’s because, from the American Revolution until the late 20th century, the American elite was divided among regional oligarchies. It is only in the last generation that these regional patriciates have been absorbed into a single, increasingly homogeneous national oligarchy, with the same accent, manners, values, and educational backgrounds from Boston to Austin and San Francisco to New York and Atlanta. This is a truly epochal development.

In living memory, every major city in the United States had its own old money families with their own clubs and their own rituals and their own social and economic networks. Often the money was not very old, going back to a real estate killing or a mining fortune or an oil strike a generation or two before. Even so, the heirs and heiresses set themselves up as a local aristocracy. Like other aristocracies, these urban patricians renewed their bloodlines and bank accounts by admitting new money, once the parvenus had served probation and assimilated the values of the local patriciate.

These regional urban patriciates were similar demographically, at a time when the racial caste system that divided whites from nonwhites was accompanied by an ethnic caste system among whites. Within the white population, Anglo American Protestants, preferably Episcopalian or Presbyterian, were at the top, followed by Anglo Americans belonging to more vulgar denominations like the Methodists and Baptists. German and Scandinavian Americans could be honorary Anglo Americans. But Irish American Catholics, Jews, and Italian and Polish Americans occupied a lower rung. Mexican Americans occupied an ambiguous position. In some areas they were discriminated against as Blacks were, in others they were treated as the equivalent of low-status whites. Black Americans and Asian Americans were excluded.

The Anglo American Protestant patricians in every region and state shared a common Anglo American and Trans-Atlantic culture—but not a common national culture. Instead, they had regional cultures separately based on a common British and European heritage. This is so peculiar that it needs to be explained.

Let us begin with what they shared: Trans-Atlantic culture. From the earliest days of the republic, the wealthy elites of even the most remote and Godforsaken parts of the South and West could afford to vacation in Europe. They would bring back the latest French and British fashions to rural Mississippi or Wyoming. Before the self-consciously regional Prairie Style of Frank Lloyd Wright, there was never any indigenous American architecture, just wave after wave of faddish European styles: Palladianism, Greek Revival, Gothic, Romanesque. The relics of these transient Europhile fads litter the United States in the form of courthouses and other old public buildings from coast to coast.

In contrast, local patriciates tried to boost their own authors at the expense of those in other American regions. My maternal grandmother, a schoolteacher for part of her career, belonged to the minor Southern gentry. She saw to it that my brother and I were introduced to the literary canon as educated white Southerners of the early 20th century conceived of it: A British substrate, consisting of Robert Louis Stevenson and Rudyard Kipling, overlain by Southern writers like Sidney Lanier, whose “The Marshes of Glynn” introduced me to the wonders of verse. The equivalent New England literary canon ran directly from Shakespeare and Milton and Pope and Scott and Tennyson to Emerson, Longfellow and Whittier and the other “Fireside Poets” (Whitman, Hawthorne, and Melville only acquired their present status later, thanks to mid-20th-century academics).

In short, for two centuries there was a double competition among regional American oligarchies. On the one hand, the local notables, particularly those from the newly settled regions, had to prove they were not backward bumpkins, but were just as up-to-date with regard to European fashions as the patricians in New York and Boston and Philadelphia. On the other hand, some of them dreamed that the city they ran, whether it was Atlanta or Milwaukee, would become the Athens or Renaissance Florence of North America, and favored local writers, poets, and artists, as long as their work was in fashionable styles and did not inspire seditious thoughts among the local masses. The subnational blocs of New Englanders, Southerners, and Midwesterners fought to control the federal government in order to promote their regional economic interests.

The status of Harvard and Yale as prestigious national rather than regional universities is relatively recent. A few generations ago, it was assumed that the sons of the local gentry (this was before coeducation began in the 1960s and 1970s) would remain in the area and rise to high office in local and state business, politics, and philanthropy—goals that were best served if they attended a local elite college and joined the right fraternity, rather than being educated in some other part of the country. College was about upper-class socialization, not learning, which is why parochial patricians favored regional colleges and universities. If your family was in the local social register, that was much more important than whether you went to an Ivy League college or a local college or no college at all.

American patricians of earlier generations would have been surprised that rich people, many of them celebrities, would scheme and bribe university officers to get their children into a few top universities. Scheming to get into the right local “society” club—now that would have made sense.

Upper-class women were the chief enforcers of local “society.” Anybody who thinks that women are somehow naturally more generous and egalitarian than men has never encountered a doyenne of high society. Mrs. Astor’s 400 families in New York had their counterparts throughout the United States, from the Mainline elite in Philadelphia to the Highland Park set in Dallas.

As in the novels of Jane Austen, the daughters of the local ruling class had to be married to a young man from a good family, if the dynasty was not to fall into disgrace. Until recently (and to this day, in some circles) a young woman’s debut in society was, if anything, more important than marriage itself, since the debutante ball helped to define her eligibility for a high-status marriage.

When I explain all of this to friends from other countries, they tend to be surprised, if not suspicious of my account. What about frontier egalitarianism? Wasn’t America dominated by the just-folks middle class in the 19th and 20th centuries? Isn’t America in danger now, for the first time in its history, of becoming an Old World style hierarchy?

The egalitarianism of the American frontier is greatly exaggerated. Some of the myth comes from European tourists like Alexis de Tocqueville, Harriet Martineau, and Dickens. For ideological reasons or just for entertainment, they played up how classless and vulgar Americans were for audiences back in Europe. On their trips they mostly encountered the wealthy and educated, who might have been informal by the standards of British dukes or French royalty, but who were hardly yeoman farmers. If these famous tourists had spent their time in slave cabins, immigrant tenements, miners camps, and cowboy bunkhouses, they might have gotten a different sense of how egalitarian America actually was. Elite Americans might have been more likely than elite Brits to smile politely when dealing with working-class people, but they were no more likely to welcome them into the family.

The Western frontier was not entirely a myth, to be sure. My great-great-grandfather proposed marriage to my great-great-grandmother by handing her a letter from horseback before riding north on a cattle drive from Texas to Kansas, and a distant uncle was murdered by outlaws on the road outside of Austin in the 1880s. But the Wild West or boomtown era everywhere was brief. The first white settlers in a region may have been trappers or small farmers or ranchers or outlaws or pirates, but once Native Americans had been removed to reservations and the railroad was in place, the area was rapidly gentrified. The rich moved in, bought up the good land, built mansions and the local opera house in the current European style and drove the frontiersmen and their families out.

White poverty in the United States today is concentrated in greater Appalachia, because the Scots Irish settlers, often illiterate squatters, were priced out of other areas and ended up in the hills of Appalachia, the Ozarks, and the Texas Hill Country. As soon as the affluent discover the scenic views in those areas, they will be forced to move once more, just as old-stock families are already being priced out of the Texas Hill Country by rich refugees from California, bringing with them their cultural heritage of trophy wineries and boutiques, New Age spirituality and organic cuisines.

Because there was no single national American elite, there was never a single Western frontier. New Englanders moved west in a band to the south of the Great Lakes, and then moved eastward and inland from ports on the Pacific Coast. While the Scots Irish followed the hills, the Southern planter class acquired cotton-friendly soil from Virginia along the Gulf of Mexico to central Texas, where the coastal plain collides with the southernmost part of the Great Plains. As the historians David Hackett Fischer and Wilbur Zelinsky have pointed out, these parallel bands of east-to-west settlement brought separate Anglo American cultures, reflected in everything from codes of honor to town layouts (town planners in greater New England laid out village greens with churches and schools, while Southern towns tended to be centered on the courthouse).

In short, a historical narrative which describes a fall from the yeoman democracy of an imagined American past to the plutocracy and technocracy of today is fundamentally wrong. While American society was not formally aristocratic it was hierarchical and class-ridden from the beginning—not to mention racist and ethnically biased. What’s new today is that these highly exclusive local urban patriciates are in the process of being absorbed into the first truly national ruling class in American history—which is a good thing in some ways, and a bad thing in others.

Compared with previous American elites, the emerging American oligarchy is open and meritocratic and free of most glaring forms of racial and ethnic bias. As recently as the 1970s, an acquaintance of mine who worked for a major Northeastern bank had to disguise the fact of his Irish ancestry from the bank’s WASP partners. No longer. Elite banks and businesses are desperate to prove their commitment to diversity. At the moment Wall Street and Silicon Valley are disproportionately white and Asian American, but this reflects the relatively low socioeconomic status of many Black and Hispanic Americans, a status shared by the Scots Irish white poor in greater Appalachia (who are left out of “diversity and inclusion” efforts because of their “white privilege”). Immigrants from Africa and South America (as opposed to Mexico and Central America) tend to be from professional class backgrounds and to be better educated and more affluent than white Americans on average—which explains why Harvard uses rich African immigrants to meet its informal Black quota, although the purpose of affirmative action was supposed to be to help the American descendants of slaves (ADOS). According to Pew, the richest groups in the United States by religion are Episcopalian, Jewish, and Hindu (wealthy “seculars” may be disproportionately East Asian American, though the data on this point is not clear).

Membership in the multiracial, post-ethnic national overclass depends chiefly on graduation with a diploma—preferably a graduate or professional degree—from an Ivy League school or a selective state university, which makes the Ivy League the new social register. But a diploma from the Ivy League or a top-ranked state university by itself is not sufficient for admission to the new national overclass. Like all ruling classes, the new American overclass uses cues like dialect, religion, and values to distinguish insiders from outsiders.

Dialect. You may have been at the top of your class in Harvard business school, but if you pronounce thirty-third “toidy-toid” or have a Southern drawl, you might consider speech therapy.

Religion. You may have edited the Yale Law Review, but if you tell interviewers that you recently accepted Jesus Christ as your personal savior, or fondle a rosary during the interview, don’t expect a job at a prestige firm.

Values. This is the trickiest test, because the ruling class is constantly changing its shibboleths—in order to distinguish true members of the inner circle from vulgar impostors who are trying to break into the elite. A decade ago, as a member of the American overclass you could get away with saying, along with Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton, “I believe that marriage is between a man and a woman, but I strongly support civil unions for gay men and lesbians.” In 2020 you are expected to say, “I strongly support trans rights.” You will flunk the interview if you start going on about civil unions.

More and more Americans are figuring out that “wokeness” functions in the new, centralized American elite as a device to exclude working-class Americans of all races, along with backward remnants of the old regional elites. In effect, the new national oligarchy changes the codes and the passwords every six months or so, and notifies its members through the universities and the prestige media and Twitter. America’s working-class majority of all races pays far less attention than the elite to the media, and is highly unlikely to have a kid at Harvard or Yale to clue them in. And non-college-educated Americans spend very little time on Facebook and Twitter, the latter of which they are unlikely to be able to identify—which, among other things, proves the idiocy of the “Russiagate” theory that Vladimir Putin brainwashed white working-class Americans into voting for Trump by memes in social media which they are the least likely American voters to see.

Constantly replacing old terms with new terms known only to the oligarchs is a brilliant strategy of social exclusion. The rationale is supposed to be that this shows greater respect for particular groups. But there was no grassroots working-class movement among Black Americans demanding the use of “enslaved persons” instead of “slaves” and the overwhelming majority of Americans of Latin American descent—a wildly homogenizing category created by the U.S. Census Bureau—reject the weird term “Latinx.” Woke speech is simply a ruling-class dialect, which must be updated frequently to keep the lower orders from breaking the code and successfully imitating their betters.

Mrs. Astor would approve.

#ivy league#history#american history#oligarchy#aristocracy#american culture#bourgeois culture#bourgeoisie#class society#class struggle#class system#overclass#russiagate#virtue signaling#woke culture#wokeness#petite bourgeois#harvard#yale

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

I was today years old when I finally learned that the word “tutu” actually originates in the early 20th century, and wasn’t some kind of coevolution with the entirety of 19th-century ballet as I’d vaguely assumed. Specifically, Etymonline (by far the online source I consider most trustworthy for this kind of research) gives the first usage of the word as 1910; Merriam-Webster gives it as 1913. Other sources, such as the Macmillan Dictionary blog and the Oxford Languages result that typically pops up if you Google something like “X etymology” give the the first appearance of the word as simply “early 20th century,” insofar as it refers specifically to the skirt worn by a ballerina. (The Wikipedia page for “Tutu (clothing)” gives the earliest recorded usage as 1881, but that date has no citation and appears nowhere else I’ve been able to look, so I’m disinclined to give it any merit. And, frustratingly, Apollo’s Angels by Jennifer Homans, an otherwise excellent history of ballet, for some reason skips over the origin of the word “tutu” entirely; so unfortunately I can’t appeal to non-digital resources for clarification.) This would ordinarily be just a fun little bit of trivia, but in the context of Princess Tutu it brings up some Interesting implications. Like, this means that in order to have a character named “Princess Tutu,” and for that name to automatically conjure in the public consciousness images of a ballerina in a frilly skirt, Drosselmeyer couldn’t have begun writing The Prince and the Raven any earlier than 1910. Among other things, this indisputably puts the anime as technically happening in the “modern day” (sometime between the mid-1990s and the 21st century aughts, depending on how you measure) --- it kind of has to, for Drosselmeyer to have been writing that late and still be four or five generations distant from Fakir. Especially since the age of marriage (and presumably occurrence of first legitimate offspring) rose throughout the 19th century, the time period in which Drosselmeyer would’ve been born and probably lived the majority of his years. Looking at all states in 19th-century Germany, as in this JSTOR article, in 1867 an average of about 74% of men who married at all did so between the ages of 30 and 39, rising to nearly 77% in 1871, then to a little over 81% in 1880; the numbers for women in that same age bracket kept pace, though the percentage of them represented in later marriage seems to consistently stayed a little bit higher. So the old-timey storybook aesthetic seen throughout the show isn’t any indicator of when the anime takes place, so much as simply the “look” of the Story as dictated by Drosselmeyer. An out-of-time fairytale town, the perfect stage for any number of tales he might spin. More interestingly, this means that Drosselmeyer would’ve been writing his final work either in the years just preceding World War I, or perhaps during the war itself. Even before that, around the turn of the 20th century, the world of German art (theatrical and literary) had been enamored of tragedy and violence, as Barbara Tuchman expounds on in her thorough and compulsively readable book The Proud Tower: A Portrait of the World Before the War, 1890 - 1914 (though it should be noted that by “world” she’s mostly referring to Britain, France, Germany, America, and the Hague): “Tragedy was the staple of the German theatre [...] Death by murder, suicide or some more esoteric form resolved nearly all German drama of the nineties and early 1900′s.” So, if writing before the War, Drosselmeyer would have been surprisingly in line with the zeitgeist of the nation. At the very least, I think it’s safe to say that his brand of storytelling was a solid fit for the time period. And the specification of “theatre” isn’t a dealbreaker, since many a writer of short stories and novels also dabbled in playwriting, and vice versa --- Oscar Wilde is the immediate example that jumps to mind. Not to mention that Drosselmeyer himself seems to have something of a preoccupation with theatre in the broad sense, what with all those puppets. We’re never given enough information about his oeuvre to definitively conclude whether or not he ever wrote for the theatre or was acquainted with anyone who did, but in any case it’s not a far leap to posit that the prevailing aesthetic of the stage likely influenced and informed what went on the page. If he was writing The Prince and the Raven during World War I, though, we must enter the realm of the more purely speculative (though that is half the fun of applying Real World History to something like this). We know that Drosselmeyer was killed because the Bookmen, as well as various people who had apparently once come to him to have stories of wealth and power spun for them (“the nobles” in particular are mentioned, which I find interesting), feared that he would use his power to create a great tragedy that would sweep them all along in its destructive wake. Now, on the one hand, it probably only takes five minutes of talking to the guy to figure out that he doesn’t exactly have humanity’s best interests at heart, so their conclusion didn’t really need much in the way of supporting evidence. On the other hand, World War I was itself a tragedy in every sense, and a brutal one at that; which tore a great rift between the Old World and the Modern World with such unimaginable violence that the world was irrevocably and forever changed by the trauma of it. While I doubt that any of the Bookmen or others would have necessarily thought Drosselmeyer responsible for the conflict --- even his considerable story spinning powers could alter reality significantly only in one small town, plus he seems just plain uninterested in “realistic” storytelling devices and genres --- I wouldn’t be surprised if they were all suddenly keenly aware of how he might take advantage of it to craft even more gruesome tragedies of his own. That realization and paranoia, combined with the ever-mounting cost of the war in terms of both resources and human lives, could have been the catalyst that pushed these people to act to decisively against the possible threat that Drosselmeyer represented. Indeed, it might also account for the cruelty of the execution, the impotent brutality of the wider war finding its local synecdoche in a mob removing the hands of a dangerous individual, but not the head. (Although, that’s also assuming that Drosselmeyer didn’t just find out about the Bookmen’s plan and use his spinning to manipulate them into performing an “execution” that would give him time for the whole writing-in-blood thing --- but that’s going from simple speculation to wild speculation, so I’ll leave that be for now.) In any case, looking at all of this evidence across history and culture, I feel relatively safe in stating that Drosselmeyer likely wrote The Prince and the Raven, and of course died, sometime between 1910 and 1918. (There might also be something to be said about a possible connection between his mechanical clockwork pocket dimension and the emergence of mechanized warfare during WWI as well, I think, but the idea isn’t fully formed and I’ve already gone on long enough as is.) I might even go so far as to shorten the time frame to no later than 1917 --- that would still allow for the conclusion of 1916, the year that saw the battles of both the Somme and Verdun, two of the most infamously bloody battles of World War I (which would certainly have an effect on the psyches of the general population, and specifically certain individuals who were already fearful of tragedy befalling them). Hell, maybe even smack-dab in the middle of 1916, it certainly would’ve been stressful enough. Regardless, it’s strange and a little exciting to have identified a more or less precise time period for the writing of The Prince and the Raven, and all thanks to looking up the history of a single related word.

#princess tutu#my writing#meta#historical context#oh god i just put drosselmeyer in historical artistic context#oh fuck i have Sources supporting my claims#do you ever set out to share a short tidbit of mildly interesting info and end up writing the rough outline of an academic essay?#this is how my mind works someone please either stop me or pay for me to go back to college

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Repress (Past Fic)

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

R.I.P., Richard Benson: Photographer, Printer, and Educator http://ift.tt/2sZkBdG

I think the first time I actually met Richard “Chip” Benson was at Wellesley College in the 80s. It was at an opening reception and Chip and Lee Friedlander were being honored as they had both just received MacArthur grants. I knew the Bensons were from Newport, RI and were friends of my sister and brother-in-law Marc Harrison, an industrial designer and chair of the ID Department at RISD.

Richard Benson died June 22, 2017 at the age of 73.

From time to time I’d hear that Chip had done something extraordinary and knew he was printing his 8 x 10 negatives on aluminum with the result being these incredibly flat prints that seemed to go on forever. He was friends with John Szarkowski, the photo curator at MOMA and I remember seeing his work on display once at the museum. During those years Chip was heavily invested in making separations for photo books. An example is the four volumes on Eugene Atget produced for the Museum of Modern Art.

By the late 80s and early 90s digital was beginning to be the hot topic. Kodak built a research center for all things digital in Camden, Maine called the Center for Creative Imaging. I wrote grant applications to allow me to take classes and do research and found, of course, when I arrived, that Chip was already there. I was struggling to understand how to move a mouse around and what this thing called Photoshop was all about and Chip was scanning his 8 x 10’s with a drum scanner and writing back to 8 x 10 film in a special restricted “cold room”on the Center’s single large format LVT.

A large format LVT (Light Valve Technology) recorder

By 1992 or 1993, I had asked for and received “special status” at the Center, which gave me free reign over all the Center’s operations. I had also been given a show the next summer in the first floor gallery. That year I was up there every time I got a chance, hanging out in classes, now scanning and film writing my own 8 x 10 negatives and occasionally running into Chip, who was always doing something incomprehensible, reinventing photography.

In the early summer of 93 (I believe) I loaded up the car full of framed prints and drove up to Camden to install my show at the Center. We hung the show over a weekend. Chip came to the opening and invited me to a lecture he was giving the next day on the “History of Photography”. I decided to hang around.

I thought I knew something about the history of photography myself. After all, I was teaching it back at my university, along with a course in contemporary directions every other year.

But Chip changed all that, as his lecture, given without notes, to a mostly Camden summer tourist crowd, was a revelation. I came from the Beumont Newhall school of the history of well-off western white guys inventing the medium, with an occasional Dorothea Lang or Bernice Abbott thrown in the mix for good measure. Chip revealed that, amazing as it seems, photography was taking place in the mid 1880s in places like India, Asia, South American and Africa. Of course, much of it was brilliant. His perspective and the depth of his research and knowledge was mind blowing. I have never quite looked at my chosen discipline the same way since that day. It was clearly evident that I was in the presence of a genius as well.

I wanted more of Chip’s brilliance but by this time he was regarded as a real resource. Most years at Northeastern I taught a view camera course and inevitably we would head off in a school van for field trips. I would tend to head us toward Newport, RI where Chip lived. I would call up Chip a couple of days in advance and ask him if he could join us for lunch. Mostly, he would dodge me as he had some fierce deadline for something and didn’t want to be diverted but I convinced him a couple of times to meet with us.

I remember one day. We’d been out at Fort Adams in Newport in late March in spitting snow and rain trying to take pictures. After, we piled into a restaurant and Chip arrived. There were probably 8 of us. We sat at a big table in a mostly empty restaurant in the late afternoon. Me, these students who didn’t know who Walker Evans, Diane Arbus, or Alfred Steiglitz was, let alone Richard Benson, and Chip.

We settled in and Chip said, “well, Neal, what do you want me to talk about?” Oh my God, caught speechless. Then I thought, selfishly, this isn’t going to be such an import thing for the students because this is way far above where they are, but it could be for me. So I asked Chip to talk about what he was working on right now.

That’s all it took.

I got another blast of genius. All you needed to do with him was to prime the pump. Separations, masking, and some sort of hybridized system of film and digital capture, stochastic curves, tweaking dynamic range, some stuff about optics, and working with the limitations of present day technology, predictions of short range and longer term challenges and solutions, some chemistry, enough to fill my teeny tiny brain in five minutes and he went on for what must have been an hour.

I have no recollection of anything else, driving us back to school, what the students thought or even said to me the rest of that day.

The final story and the last time I saw Chip was in the late 90s. He was by then the dean of the Yale Graduate School of Design (1996-2006) and had invited Frederic Sommer to give a talk (for more on Fred search the blog for “Sommer”). I drove down to New Haven that afternoon for the presentation. When I got to the hall where Fred was to speak, I found a couple of my students had made the trip as well.

Chip introduced Fred, Fred gave his talk and then the two students and I went nearby for a beer and maybe a slice before driving back to Boston. Soon, in walked Fred Sommer and Chip Benson, with a few graduate students, there to do the same thing. They walked by me and didn’t take any notice. But there were two of the most brilliant people I’d ever known, hanging out, having a beer and pizza after a talk on a weeknight at Yale. Damn.

Thank you, Chip, for your huge contribution to photography.

Want to know more about Chip Benson? His work is represented by Pace MacGill Gallery and he created a website that explains much of his research.

About the author: Neal Rantoul is a career artist and educator. After 10 years teaching at Harvard and 30 years as head of the Photo Program at Northeastern University in Boston, he retired from teaching in 2012. You can find out more about him or see his photographic work by visiting his website. This article was also published here.

Go to Source Author: Neal Rantoul If you’d like us to remove any content please send us a message here CHECK OUT THE TOP SELLING CAMERAS!

The post R.I.P., Richard Benson: Photographer, Printer, and Educator appeared first on CameraFreaks.

June 30, 2017 at 08:04PM

0 notes