#I still read a biography years later and that biographer sure did not have many kind feelings towards her it seemed

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

It’s so absurd to see Sisi on my dash. It’s like tumblr took a peek into 12 year old me’s mind and went “yeah, that unlikeable eating disordered horse woman with the bad teeth and the Heine obsession sounds like the perfect it girl”

Then again, tumblr WOULD think that.

#I remember being soooo obsessed with her bc of the pretty dresses#I forced my mother to go to the Sisi museum in Vienna and everything#and that museum sure was a wake up call.#I still read a biography years later and that biographer sure did not have many kind feelings towards her it seemed#and now people are talking about her???!!! on MY dash?!#I remember seeing a yassified portrait of her floating around a while back#and everyone in the notes acted like it was the real portrait as if she didn’t have anime nose syndrome#anyways I relate to her because my teeth are S H I T. so idk sisters in bad teeth I guess. plus I like Heine and write bad poetry. so.#once more a ‘disliking the self through the other’ type situation

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

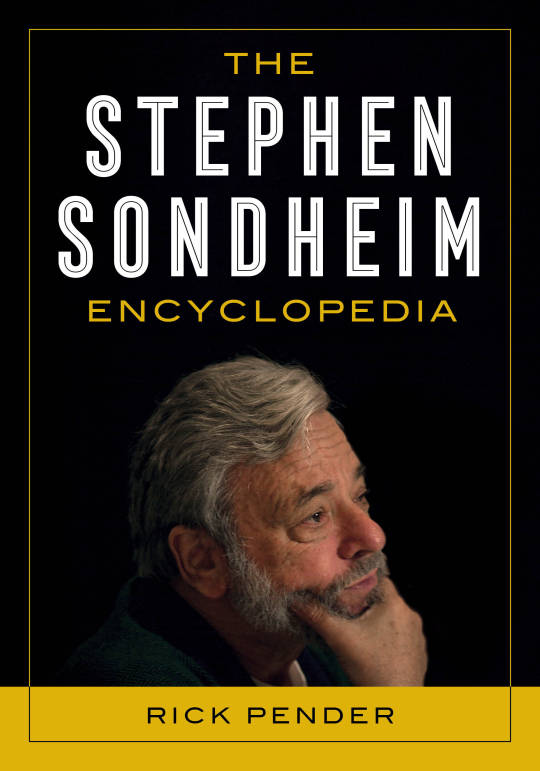

Rick Pender knows his Sondheim from A to Z

If the word “encyclopedia” conjures for you a 26-volume compendium of information ranging from history to science and beyond, you may find the notion of a Stephen Sondheim Encyclopedia perplexing. But if you have ever looked at a bookshelf full of book after book about (and occasionally by) the premiere musical theatre composer-lyricist of our era and wished all that information could be synthesized and indexed in one place, maybe the idea of a Sondheim encyclopedia will start to make a little more sense to you. It did to Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, an independent publisher that’s made encyclopedias such as this one of their calling cards, offering tomes on everyone from Marie Curie to Akira Kurasowa. Several years ago, they approached Rick Pender, longtime managing editor of the gone but never forgotten Sondheim Review and now, after years of research, writing, and pandemic-related delays, the The Stephen Sondheim Encyclopedia is finally hitting shelves. I sat down with Rick (via Zoom) to chat about this unique, massive project.

FYSS: I want to really focus on the new book, but we should start with your history with Sondheim and The Sondheim Review. How did you become so enmeshed in this work?

RP: As a teenager, the first LP that I bought was the soundtrack from West Side Story, and I didn't have any clue about who much of anybody was, particularly not Stephen Sondheim. But I loved the lyrics for the songs, especially “Something’s Coming” and “Gee, Officer Krupke.” These are just fabulous lyrics.

Then, of course, in the ‘70s it was hard as time went by not to have some awareness of Sondheim. I saw a wonderful production of Night Music in northeast Ohio, and I again just thought these lyrics are incredible, and I love the music from that particular show. Fast forward a little further in the late ‘80s, I was laid up with some surgery and I knew I was going to be bedridden for a week or two anyway, so I went to the public library and grabbed up a handful of CDs, and in that batch was A Collector's Sondheim, the three-disc set of stuff up through about 1985, and I must have listened to that a hundred times, I swear, because it had material on it that I didn't know anything about like Evening Primrose or Stavisky. So that really opened my eyes.

Later, my son had moved to Chicago. He's a scenic carpenter and a union stagehand. He worked at the Goodman Theatre, and I went to see a production when they were still performing in a theater space at the Art Institute of Chicago, and they had a gift shop there. And lo and behold in the rack I saw a copy of a magazine called The Sondheim Review! I thought, oh my gosh, I've got to subscribe to this! This would have been about 1996, probably, so I subscribed and enjoyed it immediately. A quarterly magazine about just about Stephen Sondheim struck me as kind of amazing.

In 1997-98 the Cincinnati Playhouse did a production of Sweeney Todd in which Pamela Myers, all grown up, played Mrs. Lovett, and so I wrote to the editor of the magazine and said, “Would you like me to review this?” That started me down a path for a couple of years of making fairly regular contributions to the magazine. Then in 2004 that editor retired, and I was asked to become the managing editor, which I did from 2004 to 2016. It went off the rails for some business reasons, but it lasted for 22 years which I think is pretty remarkable.

I tried to sustain it in an alternative form with a website called Everything Sondheim. We put stuff up online for about 18 months, and we published three print issues that look very much like The Sondheim Review, but we were not able to sustain it beyond that.

FYSS: How did the Encyclopedia project originate?

RP: The publisher asked me to write an encyclopedia about Stephen Sondheim! I envisioned that I would be sort of the general editor who coordinated a bunch of writers to put this together, but they said no, we're thinking of you as being the sole author. They had done a couple of other encyclopedias particularly of film directors, and those were all done by one person, so they sent me a contract asking me to generate 300,000 words for this book, and after I regained consciousness, I said all right, I'll give it a try.

It took me about two years – most of 2018 and ‘19 – to generate that content. I sent it off in the fall of ‘19, and then, well, the world stopped because of the pandemic. It was supposed to come out April a year ago, and they had just furloughed a bunch of their editors and everything stalled. But now it's coming out mid-April 2021.

FYSS: What was the research and writing process like?

RP: This project came about in part because the publisher initially approached another writer, Mark Horowitz, who's at the Library of Congress and who had done a Sondheim book of Sondheim on Music. Mark and I had become quite close because he wrote a number of wonderful features about different Sondheim songs for The Sondheim Review. When I heard that that he had put my name out there, I went back to him after I had agreed to do this and said, Mark, could we use some of that material that you wrote for the magazine about those songs? And he said, sure do with them whatever you wish. And I was glad he said that, because they were really long pieces, and I've reduced each of them to about 1500-2000 words, which I thought was probably about the maximum length that people would really want to read in a reference volume.

But other than that, I generated everything else myself. I relied upon plenty of material within the 22 years of back issues of The Sondheim Review. Another great resource was Sondheim's own lyric studies, the two-volume set which provides so much information about the production of shows and that sort of thing.

Of the 131 entries I wrote for this, 18 of them are lengthy pieces about each of the original productions, so again Sondheim's books were certainly useful for that, and other books like Ted Chapin's book about Follies.

I also spent some time in Washington, D.C. at the Library of Congress, and Mark loaned me a quite a bit of material that he had collected – not archival material but scrapbooks of clippings that he put into ring binders of stuff about Sondheim's shows.

I came back to Cincinnati with about four or five cartons of materials, and I could really dig through that stuff as I was working on these. And then I have, as I'm sure you and lots of other Sondheim fans have, a bookcase with a shelf or two of Sondheim books, and those were all things that I relied upon, too.

I actually generated a list with lots and lots of topics, probably over 200, and I knew that was going to be more than I could do. Eventually, some things were consolidated, like an actor who perhaps performed in just one Sondheim show wasn't going to get a biographical entry, but I would talk about them in the particular show that they were involved in. So, I was able to collapse some of those kinds of things. But as I said, I did end up with 131 entries in the publication, and it turned out to be 636 pages, so that's a big fat reference book.

FYSS: Who is the intended audience for a work like this? RP: The book is really intended to be a reference volume more than a coffee-table book. It does have photography in it, but it's black and white and more meant to be illustrative than to wallow in the glories of Sondheim. There is an extensive bibliography in it, and all the material is really thoroughly sourced so people can find ways to dig into more.

FYSS: Sometimes memories diverge or change over time. Did you come across any contradictions in your research, and how did you resolve them?

RP: I can't say that I can recall anything like that. I relied very heavily on Sondheim's recollections in Finishing the Hat and Look, I Made a Hat because he's got a memory like a steel trap. Once in a while I would email him with a question and get very quick response on things. I really used him as my touchstone for making sure of that kind of thing.

I also found that Secrest’s biography was very thoroughly researched, and I could rely on that. But I can't say that I found a lot of discrepancy, and some of those kinds of things were a little too much inside baseball for me to be including in the encyclopedia.

FYSS: For figures with long and broad histories, how did you decide what to include? George Abbott, for example, is the first entry in the book and he worked for nine decades! How important was writing about an individual as they relate to Sondheim vs. who they were more generally?

RP: To use George Abbott as an example, I would say that the first things that I did was to go back to the lyric studies and to the Secrest biography and just look up references to Abbott. I mean, it was George Abbott who said that he wanted more hummable songs from Sondheim, so you know that was certainly an anecdote that was worth including because, of course you know, it becomes a little bit of the lyric in Merrily We Roll Along.

So you know, I would look for those kinds of things, but I also wanted to put Sondheim in context because Abbott was well into his career when he finally directed Forum which, since it was Sondheim's first show as a composer and a lyricist, is significant. That was very much the focus of that entry, but I wanted to lay a foundation in talking about Abbott, about all the things that he had done before that. I mean, he was sort of the Hal Prince of his era in in terms of his engagement in so many different kinds of things – writing plays, directing musicals, doctoring shows, all of that.

FYSS: Did any entries stick out to you as being the hardest to write?

I think the most complicated one to write about probably was Bounce/Road Show because it's got a complicated history, and Sondheim has so much to say about it. And because it's not a show that people know so much about, I wanted to treat it appropriately, but not as expansively as all of that background material might have suggested. So I kind of had to weave my way through that one. It also was a little tough to write about, because how do you write a synopsis of a show that has had several incarnations quite different from one another, and musical material that has changed from one to the other? With shows like that, I particularly tried to resort to the licensed versions of the shows.

FYSS: I haven't had a chance to read the book cover-to-cover yet, but I did read the Follies and the Into the Woods entries to try to get a sense of how you covered individual shows, and both of those are shows that had significant revisions at different times. And I thought you made it very clear what they were and also where to go for a reader who wants to learn more.

RP: Let me say one other thing this is not directly on this topic, but it sort of relates, and that is that in writing an encyclopedia, I didn't want to overlay a lot of my very individual opinions about things, but with each of the show entries I tried to review the critical comments that were made about the show in its original form, perhaps with significant revivals and that sort of thing, and then to source those remarks from critics at those various points in time. And of course, my own objectivity (or lack thereof) had something to do with what I was selecting, but I thought that was a good way to represent the range of opinion without having to make it all my own opinion.

FYSS: Did you feel any responsibility with regards to canonization when you made choices about what to include or exclude? What made the First National Tour of Into the Woods more significant than the Fiasco production, for example? Why do Side by Side by Sondheim & Sondheim on Sondheim get individual entries, but Putting It Together is relegated to the omnibus entry on revues?

RP: I guess that now you are lifting the curtain on some of my own subjectivity with that question. I tried to identify things that were particularly significant. I mean with the revues for instance, several of those shows – you know, particularly Side by Side by Sondheim, the very early ones – they were the ones I think that elevated him in people’s awareness. So, I think that to me was part of what drove that. And then shows that that were early touring productions struck me as being things that maybe needed a little bit more coverage. I think the Fiasco production was a really interesting one, but with the more recent productions of shows I just felt like there's no end to it if I begin to include a lot of that sort of thing.

FYSS: I mean it's so subjective. I'm not the kind of person who clutches my pearls and screams oh my goodness, how could you not talk about this or that. But I was surprised to see in your Follies entry that the Paper Mill Playhouse album was not listed among the recordings, for example. I imagine that once this book hits shelves you're going to be bombarded with people asking about their pet favorites.

RP: Oh, I'm sure, and maybe that will be a reason to do a second edition, which I’m totally ready to do.

The Sondheim Encyclopedia hits bookstore shelves April 15. It’s available wherever you buy books, but Rick has provided a special discount code for readers of Fuck Yeah Stephen Sondheim to receive 30% off when you order directly from the publisher. To order, visit www.rowman.com, call 800-462-6420, and use code RLFANDF30.

Celebrate the launch of The Sondheim Encyclopedia with a free, live online event featuring Rick Pender in conversation with Broadway Nation’s David Armstrong Friday, April 16 from 7:00 to 9:00 p.m. Eastern. More information and register here.

17 notes

·

View notes

Note

2, 7, 30?

Ooh, my first request!

2. Favorite underrated historical figure?

Princess Taiping/ 太平公主! I wrote a paper on her and it was really hard to find sources discussing her in her own right. She’s a Zhou and Tang-dynasty figure, the daughter of the famous Wu Zetian, known as the only female emperor in China (Zhou being the single-generation dynasty established by Wu Zetian) She’s not someone I’d emulate, but man, she lived a wild life.

She instigated two successful coups and played politics like nobody’s business. All the while, she amassed landholdings and wealth. She was her mother’s right-hand woman: Emperor Wu* used one of the Taiping Princess’ plans to get rid of a confidante who’d gone too far by setting fire to a temple. Princess Taiping’s first husband was implicated in a failed rebellion against her mother and executed, but she was able to remarry and stay on the scene. In fact, we’re pretty sure her mother had the wife of her second husband assassinated so she could remarry him. I think it’s fascinating that she was able to stay on top during her mother’s rule, as two of her brothers were executed by her mother and two were ousted from power after being named successors. Later in her mother’s life, Taiping outmaneuvered both her mother and her mother’s head of secret police to coerce her mother into agreeing to oust him.

Eventually, she knew winds were changing in the court and her mother was falling out of favor, so she helped convince her to abdicate the throne in favor of one of her brothers, who I will refer to as Emperor Zhongzong.

It’s kinda complicated to talk about the crazy intrigue that followed her mother’s death, because practically all of her brothers and nephew all have multiple names: birth names, ruling names, and post-humous reign titles, so it can get a little confusing. So Emperor Zhongzong (sounds like jhong-tsong) came into power and his wife, Empress Wei, was also a strong political actor. She did not want Princess Taiping wielding that much political power, and Princess Taiping had lost her most powerful backer when Wu Zetian stepped down. Empress Wei wanted her daughter, the Anle princess, to hold power in the court, and even tried to have her named crown princess and heir, something unprecedented. That didn’t work and her son Li Chongmao/later Emperor Shao was named successor instead. It’s strongly suspected that Empress Wei and the Anle princess (sounds like ahn-leh) conspired to and successfully poisoned Emperor Zhongzong. The Taiping Princess lost no time in launching a coup, and in two weeks time both Empress Wei and the Anle princess were dead.

Li Chongmao didn't stand a chance. He was around 10-12 when this happened, and when people were still talking about who would be the new leader, she said “Everybody turns to the prime minister [princess Taiping’s brother, Li Dan, later Emperor Ruizong], little boy; this is not your seat.”** Emperor Ruizong treated Princess Taiping as a political equal and relied heavily on her advice.

Meanwhile, his son Li Longji grew in political power and prowess. She felt threatened by him, and participated in a smear campaign to limit his power. He tried to placate her appointing her supporters to government, so the government was filled with people loyal to her. Unfortunately for her, Emperor Ruizong’s advisors still managed to convinced him to exile her. Through her connections, she was still able to maintain power in the court.

In 712 ACE, Emperor Ruizong took a comet as a sign he was to step down (rather than eventually getting killed in the struggle between his son and sister) and announced his future abdication to his son Li Longji, temple name Emperor Xuanzong (shu-en tsong) which is how I will refer to him from now on). Aware of what this would mean for her, the Taiping Princess planned her third coup, an armed struggle to upend the soon-to-be Emperor Xuanzong, but was betrayed and discovered. She fled to a monastery, but was found three days later and permitted to commit suicide (seen as more honorable than execution). In the aftermath of the coup, all of the political leaders associated her were implicated by association and were executed or forced to commit suicide. Get this: that was all but one of the chief ministers! It took years for the state to completely appropriate her amassed landholdings and wealth.

*So Empress usually denotes a designated wife of an emperor (皇帝). Wu Zetian went from a consort to empress regent to empress regnant, essentially. When Wu Zetian ascended the throne, she did some masterful religious and linguistic subversion to establish her legitimacy and came up with a lot of new terms and names to justify what she was doing, since it was unprecedented. Essentially, she was the female version of Emperor, but translating the linguistic titles is complicated.

**Sue Wiles and Lily Xiao Hong Lee “Li, Princess Taiping” Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Women, Volume II: Tang Through Ming 618 - 1644. Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Women.

7. Which time period would you like to live in?

Now. The current one. Go back too far even in the past century and I lose rights and privileges that I value, like the ability to dress as weirdly as I please, the ability to discuss issues of mental health and the #me too movement with women’s rights in general, the ability to work where I want, and the ability to openly practice religion. I would also miss conversations and changes within my own faith community about treating people of all races and backgrounds equally, church culture vs. doctrine, and attitudes towards church history.

But if I were a time traveller and could stop in a place for a vacation, I’d love to live in the early 1900s (1900-1920) and visit major urban centers for art, music, and to witness labor conditions and activism. Alternatively, if I were a time traveller I would simply attend live showings of my favorite shows and concerts (lots of musical theatre)

30. Favorite kids/teens history books:

Most of the historical fiction I’ve read takes place in the past 100 years, and a lot of it takes place in the 30s and 40s. I do have a rule for myself that I don’t seek fiction about the Holocaust--the things here are exceptions. I tend to read survivor’s accounts instead, though I couldn’t think of many novels in for this rec.

Between Shades of Grey, by Ruta Sepetys--gorgeous, heart-wrenching book about a girl in Lithuania sent to a Soviet prison camp in Siberia.

Code Name Verity and Rose Under Fire, by Elizabeth Wein--both take place during WWII. Rather brutal and play around with alternative narration styles.

The Devil’s Arithmetic, by Jane Yolen. I don’t know how to describe it. During a Passover Seder, Hannah Stern is transported back in time to 1942 Poland, during World War II.

Anything by Gillian Bradshaw (she’s more of a ‘dump you into the history hard and let you figure things out’ kind of author, which I love--I’m trying to get my hands on A Beacon at Alexandria. She also writes historical fiction set in antiquity, which I don’t see as often.)

Flygirl, by Sherri Smith about the WASP (Women’s Airforce Service Pilots). Tackles the racism of the era as well.

The Red Umbrella, by Christina Diaz Gonzalez, about the Cuban exile after the revolution of 1959

Esperanza Rising, by Pam Mu��oz Ryan, about a girl who leaves her estate in Mexico and has to live as a migrant worker in California.

Uprising, by Margaret Peterson Haddix. This is about the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire of 1911 and is a good introduction to labor issues and unions in US history. This book is almost solely responsible for why I don’t think Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them looks anything like New York at the early 20th century (yes, I know this takes place 10 years earlier, but conditions hadn’t changed all that much).

The Lightning Tree, by Sarah Dunster (not the book of the same name by Patrick Rothfuss). This one’s a bit personal--it’s a coming-of-age story following the story of a girl of Waldensian heritage set in Utah right after the Utah War (1858) and a year after the Mountain Meadows Massacre. It’s character-driven, lyrical and subverted my expectations of what would happen.

The Vanishing Point, by Louise Hawes. A fictionalized biography of Lavinia Fontana, a famous female artist in the Italian Renaissance. Considering how the art world is dominated by male artists, this was really neat to read, and also takes place further in the past than a lot of things I read.

Distant Waves, by Suzanne Weyn: Probably the weirdest book here, but just fabulous. It combines spiritualism, Nikola Tesla, Houdini and Doyle, H.G. Wells and the wealthy crème de la crème of the era with the Titanic.

Non-fiction

Yankee Doodle Gals, by Amy Nathan is about the WASP and is fabulous.

Teens at War, by Allan Zullo. Ten stories of teenagers at war throughout history.

Witch-Hunt: Mysteries of the Salem Witch Trials by Marc Aronson. One of the things I realized was just how much of an anomaly the trials were, as previously courts had been denying spectral evidence as a valid source of evidence.

Night, by Elie Wiesel. A personal history of surviving the Holocaust. Here’s the thing--if you can, read both the edition before his wife translated it and compare it to her translation. Her translations soften the hard edges of the book, which isn’t something I usually want if I’m reading about the Holocaust, but have been called more true to his words.

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot. A moving and disturbing story about race, medical exploitation, the invention of vaccines, and poverty in the U.S. I don’t know if this counts as a teen novel, but I read it as a freshman in high school on my librarian’s recommendation.

Savage Girls and Wild Boys Does this count as children or history? It’s a history about feral children (raised by animals, etc) and other children raised in extraordinary circumstances.

Sort of history? It’s more modern. Never Fall Down by Patricia McCormick. It’s kind of a memoir of Arn Chorn-Pond, someone who survived the Cambodian genocide of 1975-1979 and was a child soldier. It’s brutal, but I recommend it to everyone.

This isn’t a children’s history book, but I can’t miss an opportunity to recommend it. The Rape Of Nanking: The Forgotten Holocaust Of World War II by Iris Chang is utterly heartbreaking. The Rape of Nanjing has hugely significant to cultural memory, and yet most people I’ve talked to in the states have never hear about it

As for children’s books, I read my copy of The Secret Soldier by Ann McGovern to death. If not for its length, it would probably be falling out of its binding by now.

I also read my mother’s childhood copy of The Story of Helen Keller by Lorena A. Hickok over and over again (first published 1958).

Survivor, by Allan Zullo. Compilation of stories from children who survived the Holocaust.

The Hidden Girl, the story of Lola Rein Kaufman written between her and Lois Metzger. After her mother is killed by the Gestapo, she has to hide in a barn to survive.

OH! ETA:

Rejected Princesses: Tales of History's Boldest Heroines, Hellions, and Heretics and Tough Mothers: Amazing Stories of History's Mightiest Matriarchs by Jason Porath are a fun way to get familiar with historical and legendary female historical figures. There is some swearing and description of all the sorts of things you can imagine have happened to historical women, but it’s organized by rating and type.

@brightbeautifulthings I don’t know if asking automatically tags you?

#historical fiction#nonfiction#history#princess taiping#tw: rape#tw: genocide#tw: massacre#code name verity#rose under fire#between shades of grey#the devil's arithmetic#the immortal life of henrietta lacks#gillian bradshaw#women's airforce service pilots#wasp#cuban exile#holocaust#nikola tesla#spiritualism#margaret peterson haddix#cambodian genocide#never fall down#rape of nanking#triangle shirtwaist fire#lavinia fontana#renaissance painters#titanic#this is too hard to tag

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

Captain Marryat: 'Among the first in Dickens’s liking'

Marryat in 1841, the year he met Charles Dickens

Inevitably, when some lesser-known person is associated with Charles Dickens, that connection will be advertised as loudly as possible, since Dickens is one of the few 19th century writers and public figures who still enjoys widespread recognition in the English-speaking world. Such is the case with Frederick Marryat. A biographical blurb about Marryat will often bring up his friendship with Dickens before any of Marryat's own accomplishments are mentioned.

Despite their age difference —Marryat was 20 years older than Dickens— the two men were certainly friends. I have tried to puzzle out exactly how close they were with sometimes sketchy evidence (not helped by the fact that both men tried to burn or destroy large amounts of their correspondence.) I don’t know if the young Charles Dickens was keenly interested in meeting Captain Marryat; but Marryat was clearly aware of him. Dickens and Marryat didn’t meet each other in person until 1841, but Marryat recorded the wild popularity of Dickens’ first novel, The Pickwick Papers, as he traveled to America in 1837: “Dinner over; every body pulls out a number of ‘Pickwick’; every body talks and reads Pickwick; weather getting up squally; passengers not quite sure they won’t be seasick. [...] for many days afterwards, there were Pickwicks in plenty strewed all over the cabin, but passengers were very scarce.” (Diary in America)

As for who was influencing whom, that question is easy to answer. Marryat was first on the scene, writing in a Dickensian vein with picaresque heroes and colorful characters sketched from life before Dickens was a household name. Marryat published his nonfiction travelogue Diary in America years before Dickens’ equivalent American Notes (which was clearly inspired by Marryat.) According to the English professor Louis Parascandola, Marryat “was the first nineteenth century writer to publish his novels serially in his own magazine, the Metropolitan, an important precedent for later authors like Charles Dickens and William Makepeace Thackeray.”

The first meeting between Marryat and Dickens was arranged by their mutual friend, the artist Clarkson Stanfield. Stanfield wrote to Dickens at the beginning of 1841, “I have before told you that my friend Captain Marryat is very anxious to have ‘what all covet’, the pleasure of your acquaintance and, if therefore you have no objection to meet him, will you come and take a beef steak with me on Wednesday 27.” Dickens replied, “I shall be delighted to join you and know Marryat.”

Dickens and Marryat seem to have immediately hit it off, enjoying each other’s wit and theatrical personalities. As Marryat’s biographer Tom Pocock describes it:

The two men took to each other at once. They shared a recognition of the absurd and could present it entertainingly, sometimes mixed with pathos and even tragedy. But while Marryat re-created the world that he himself had experienced in his books, Dickens’s imagination erupted with cavalcades of characters and panoramas of widely varied scenery. Dickens did not see Marryat as a rival but recognised his skill in presenting the world of the sea and seamen, which he himself could only try to imagine. Thanking Marryat for sending him his latest novel, Dickens wrote, ‘I have been chuckling, and grinning, and clenching my fists and becoming warlike for three whole days past.’

It seems clear that Dickens and Marryat would be close friends, and Marryat himself might be a less obscure writer in the present day, except that his association with Dickens was so brief. By 1843 Marryat had sequestered himself at his country estate in Langham, Norfolk, far from the literati of London with the transportation methods of the day. Marryat’s biographies and Florence Marryat’s Life and Letters of Captain Frederick Marryat are full of entreaties from his friends begging Marryat to return to London to socialize with them and attend various events. He rarely agreed to travel, and by 1848 he was dead.

John Forster, Dickens’ friend and biographer, writes in The Life of Charles Dickens: “There is no one who approached [Dickens] on these occasions [dancing at parties with the Dickens children] excepting only our attached friend Captain Marryat, who had a frantic delight in dancing, especially with children, of whom and whose enjoyments he was as fond as it became so thoroughly good hearted a man to be. His name would have stood first among those I have been recalling, as he was among the first in Dickens’s liking; but in the autumn of 1848 he had unexpectedly passed away.”

For all the brevity of Dickens’ relationship with Marryat, they were close enough for Dickens to share some juicy gossip. In a letter to Forster, Dickens shines a rare light on Marryat’s rocky marriage. There is an anecdote about Marryat, “as if possessed by the devil,” teaching “every kind of forbidden topic and every species of forbidden word” to the overly sheltered sons of a baronet, and the “martyrdom” he suffered with his wife. Catherine (Kate) Marryat, as described by Dickens, is a violent, temperamental woman who beats her maid and has “no interest whatever in her children.”

Although Victorian propriety omitted names, as Marryat’s biographer Oliver Warner notes, “The reference might be considered vague enough— except to those who knew Marryat. To them, it must have been so clear that in later editions Forster left out all references by which Kate might identify herself.” Dickens’ 20th century biographer Walter Dexter also names the troubled couple as the Marryats.

Charles Dickens is the only person whose documented, surviving correspondence mentions the fact that Marryat spoke with a lisp. Marryat’s daughter Florence mentions no such thing, and Marryat never gave a speech impediment to his leading characters, but Dickens quips about an old fresco, “I can make out a Virgin with a mildewed Glory round her head and … what Marryat would call the arthe of a cherub.” (A few online articles about Marryat make a lot of hay over this sole mention of a lisp, and they can all thank Charles Dickens for spilling the tea.) Poor Marryat, who reminisced in a laudanum haze about all of his old friends in his final months, including “Charlie Dickens”, did he anticipate this reveal? He really should have known that Dickens had a wit that could be as mocking and caustic as his own.

Principal References (not including Marryat’s own books):

Life and Letters of Captain Frederick Marryat, Florence Marryat (1872)

Life of Charles Dickens, John Forster (1872-1874)

Captain Marryat: A Rediscovery, Oliver Warner (1953)

Puzzled Which to Choose: Conflicting Socio-Political Views in the Works of Captain Frederick Marryat, Louis J. Parascandola (1997)

Captain Marryat: Seaman, Writer, and Adventurer, Tom Pocock (2000)

#frederick marryat#charles dickens#captain marryat#victorian literature#john forster#florence marryat#1840s#literature#19th Century#history#biography#dickens quotes#the picture is from oliver warner's biography#portrait#alfred d'orsay#marryat family

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Hogwarts Reunion 1/2

Request: None

Words: 2k

Pairings: Hermione/Draco, Harry/Ginny

PART 2

To Whom It May Concern,

Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry is holding a reunion for those who graduated twenty years ago. Every wizard/witch invited will have one plus-one. Children are welcome. We expect your owl by no later than July 17th.

Sincerely, Aberforth Dumbledore

Headmaster, Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry

Hermione Granger bit her lip and stared at the letter in her hand, letting the morning light from the kitchen window shine onto it. A dark brown tawny owl sat on her kitchen counter a few feet away, waiting for her response. After she gave none, it squawked at her three times until her head snapped away from the piece of parchment. "Oh! Don't worry, we'll send an owl to the school ourselves."

Ruffling its feathers, the owl flew out of the window and into the horizon. The woman watched it fly until it disappeared before letting her gaze return to the letter, her mind racing with the possibility of seeing her schoolmates again. She, Harry, and Ron had all fallen out of touch after she went to Australia to restore her parents' memories.

She'd never come back to them.

There was a rumbling upstairs, and Hermione knew instinctively that her kids had woken up. Soon enough, they stumbled down the stairs into the kitchen, bleary eyed. At the age of sixteen, Rose was the oldest. Scorpius was only five years younger than her at eleven. Both had dirty blonde hair and brown eyes. They were sleeping in; it was a Saturday morning and even though it was summer, Hermione sent them to a tutor to get them caught up on muggle subjects such as English and Math during the weekdays.

"Where's dad?" Scorpius asked, looking around the kitchen suspiciously for his father, almost as if he expected him to jump out from behind the counter.

Hermione ruffled his hair and silently asked herself the same question. "He had to stay late at the Ministry. He'll be back soon." No need, she thought to herself, to add that the only reason she was standing in the kitchen when they woke up was that she was watching for his arrival. The dark circles under her eyes surely proved that.

"You should go to bed," Rose said quietly, following her mother's gaze out the window.

"I'm fine," Hermione said. The lie came easily and often; it was the cure-all solution to questions she didn't want to answer.

Scorpius, innocently oblivious, had started to make some scrambled eggs "the muggle way". Hermione busied herself with helping him, and soon, they were all having breakfast. After Scorpius went upstairs, Rose cornered her mother.

"He's been coming home this late for awhile now, hasn't he?" Yes, Rose was the most like her mother, caring and all. Clever, too, but Scorpius was as well - just in a different way. Hermione shifted uncomfortably, remembering all the nights when her husband had come back just in time to get in bed and pretend to have been sleeping before the children woke them up. "Maybe."

Rose’s eyes narrowed, a mannerism she’d inherited from her father. "You've been waiting up for him every night?"

The witch nodded. Rose sighed and tucked a strand of her blond hair behind her ear. "I don't understand why you love him as much as you do. He can be such a prat sometimes."

"Language, Rose," Hermione said, her tone defensive. "That's your own father you're talking about. And haven't I told you not to make assumptions? There are some things you'll never understand. Now get a head start on your homework for school. The sixth year is always one of the hardest, you don't want to enter it unprepared."

Rose sighed again and left the kitchen, casting one more anxious look at her mother over her shoulder. Hermione resumed her position by the window, looking out of it once more. He never flew from the ministry and never used floo powder. He always Apparated right in front of their doorstep...

Shifting her glance momentarily from the window to the Daily Prophet, she saw her own (considerably younger) face beaming back at her, along with news of her last whereabouts. The ad had been running every week for the last eighteen years, though the space it had been afforded in the newspaper had slowly shrank over the years. Hermione looked over the article again - the headline had not changed in eighteen years (“Missing: The Brightest Witch of Our Age”) nor had the picture of her (taken during a Ministry-organized ceremony commemorating those who’d fought against Voldemort). Even the small, italicized writing at the bottom of the ad remained the same: Last confirmed sighting October 17th, 1998 while the subject was leaving for Australia. Current whereabouts unknown. Any sightings should be reported to The Office of Misplaced Persons at the earliest convenience.

Hermione’s husband claimed that the ad was only still running because of the pull Harry Potter had in the ministry. She figured he was probably right, but it still boosted her ego quite a bit to see it in there.

Then, suddenly, a loud pop - not loud in anyone else's ears, but loud as a gong in Hermione's - sounded from the street below.

Excitedly, the brightest witch of her generation dropped the Prophet and hurried down the hall to the living room, where the entrance to the house was located.

Draco Malfoy stepped through the door, dark circles under his eyes, hands stained with ink. He was restlessly alert, and his eyes scanned the room before making contact with those of his wife's. He wrapped his arms around her, and only when he had done so did his form relax a little bit.

"I was so worried," Hermione whispered.

A smile tugged at the edge of her husband's lips. "Of course you were. Please tell me you slept at least a little?"

"I was waiting for you."

"All night? Hermione, I know you love me, but -" He was cut off as she kissed him. "Go to bed."

Her smile turned into a frown. "Not before I get some answers first. What held you up this time? The children noticed."

He sighed and looked into the kitchen as if to make sure that his kids weren't listening in. "Potter's gone mad," he whispered. "He's had us looking for you every night under threat of losing our jobs."

"It's been twenty years!" Hermione exclaimed, both annoyed and touched at the same time.

"Yeah, well, his efforts have been restarted by the so-called 'Granger sighting' a few days ago," the man said. "You should watch when you go to Diagon Alley next time."

"I don't like living under house arrest, Draco," Hermione said irritably, her tiredness wearing away at the aura of pleasantness and agreeability that her husband claimed didn't exist.

He sighed. "I know you don't, but imagine what will happen if they found us," he paused for dramatic effect, "Owls swooping in, Aurors at our front door -"

"- hexes and jinxes flying all over the place," Hermione finished wryly. She'd heard this speech many times, but it still didn't sit right with her. "They'll - they'll kidnap you, and they'll take the kids, just because - because of this!" Draco ripped up his left sleeve, revealing the Dark Mark still etched there. In all his hysteria, his voice had gotten louder.

"Quiet, the kids'll hear," Hermione shushed. Draco snorted and collapsed on the couch, all fight leaving him in one smooth motion. "They're smart, Hermione. You honestly think they haven't figured it out yet?"

She joined him, taking his hand. "I like to believe they haven't."

He studied the lines in her palm for awhile. Finally, he spoke, "We'll figure it out. We'll figure out a way for you to do things among English wizards again without having to wait a month for the Polyjuice potion to brew. We just need time." "Time heals all wounds," the witch muttered.

"It's true. After all, you married me."

"I suppose I did," she said thoughtfully. "Still, Ron and Harry were always much more close-minded..."

He couldn't help himself when he whispered, "Idiots."

Hermione chuckled. "They weren't that bad, you know. Ron was thick as a brick but he was funny. Harry -"

"Enough about the Boy Who Didn't Die, I'm sick of hearing about it," Draco said crossly.

"- just saying that if circumstances were different, you would've been great friends -"

"If he was a Slytherin, maybe..."

" - you're both smart, you know, and you both love Defense Against the Dark Arts."

"Same interests do not a friendship make!"

"Besides, who are you to judge my friends when your friends are some of the worst, tasteless and, frankly, rude people I've ever met -"

"Hermione."

"Draco."

"Stop saying such silly things before I make you stop."

"And how will you do that?" Hermione asked, subconsciously moving closer to her husband.

As usual, Scorpius had impeccable timing. "Mum! Rose has charmed my quills into attacking me again!"

Hermione rolled her eyes at her husband and stood up, following an indignant Scoripus out of the Watching her go, Draco was about to nod off before noticing a crumpled piece of parchment on the floor. Frowning, he picked it up and straightened it out before reading it. As he did, his frown deepened considerably.

"Hogwarts?" he muttered, looking at the seal on the front. "Hogwarts again?"

"You need to stop worrying Mom so much."

Draco looked down at his daughter before clearing his throat. "I try not to." "She waits up for you."

"I tell her not to."

"Dad?"

“Yes, Rose?”

“I mean this in the best way, but -”

“Get on with it.”

“I’m so lucky to have you as a father, you’re amazing and all, but -”

Draco sighed, closed his eyes, and then opened them again. “You’re asking why she married me.”

“I’ve just been wondering - there’s biographies on her, you know, I checked one out from the library back when school was in session - she punched you.”

“That’s a very determined biographer, that is.”

“I know. Rita Skeeter, I think her name is? She doesn’t portray Mum very well, but -”

“I don’t know why she married me. But I’m lucky that she did.”

"Hermione?" Draco said, holding the letter from Hogwarts in his palm.

"Yes, Draco?" his wife said airily. It was a day later, Sunday, and everyone was having a restful afternoon except Hermione, who had spent the morning completing paperwork for her position at the Magical Congress of the United States of America. It was a tribute to the bad relations between the two Wizarding governments that Hermione's whereabouts were secure within the MCUSA - though she held a high-ranking position and was well known within the magical American community, only her surname was used in press releases and interviews.

"When were you going to tell me about the Hogwarts letter?"

"I don't know."

He faced her. "Why are you so scared of what might happen?"

Hermione looked up from her book. "Because you know what a prat you were to them - and me - all through our Hogwarts years."

Draco looked hurt, and Hermione knew he was going to start saying what he always did when she broached the subject of their less-than-amicable Hogwarts years. "I didn't start it. I asked Potter to hang out with me on the first day of school and he -"

"Draco, we both know you weren't as complimentary of Ron as Harry would've liked. Your utter disdain for most things was not charming." She paused and looked at him. He looked stricken. More gently, she continued, "Now, obviously, against all my better judgment, I've gotten past that -"

"And thank Merlin you did," he muttered.

"- but they haven't. If they hear that Hermione married Draco, it would kill them. They would probably disown me. And no telling what Ron would do." Her voice rose a little with every word. She was on the verge of a full-scale anxiety attack.

Draco took her hand. "You're fine. It'll be fine. We don't even have to go."

She pursed her lips. “My gut is telling me to go, though.”

“Whatever you decide.”

"We'll go," Hermione said, cracking a smile at him.

"How will you tell them?"

She sighed, her forehead creased in thought. "I just will. Don't worry about it."

The children were told the next day. Rose, who knew her parents' history, had initially argued with the arrangement, voicing all of Hermione's silent concerns. But when she saw the look of determination on her mother's face, she backed off. Draco sent an owl back with their confirmation. And so things were ready.

#hogwarts school of witchcraft and wizardry#hogwarts#harry potter#harry potter fanfiction#dramione#draco x hermione#hermione x draco#hp fanfic#draco malfoy#hermione granger#scorpius malfoy#hermione malfoy#hogwarts reunion#fanfiction#battle of hogwarts#harry x ginny#hinny#ginny x harry#albus severus potter#albus potter#gratuitous tags#i'll stop now#here's a trope#ron weasley#after the battle#ok actually stopping#original#mywriting#hp-fanfictionworld writing#hpfanfictionworld

102 notes

·

View notes

Text

I don’t often read biographies. I only have 12 books on my Goodreads shelf labelled “biography” that I’ve actually read, and a couple of those might be stretching the definition a bit (e.g., Kate Bolick’s Spinster: Making a Life of One’s Own, which includes biographical sketches as part of a more autobiographical project). Looking over the short list of biographies I’ve actually completed, it appears I’m primarily drawn to biographies of women, including the following: Rachel Carson, Judith Merril, George Eliot, James Tiptree, Jr. (aka Alice Sheldon), Rosa Luxemburg, Octavia E. Butler, and Shirley Jackson. The list also includes Rachel Ignotofsky’s Women in Science: 50 Fearless Pioneers Who Changed the World, which is a collection of short, illustrated biographical sketches of female scientists throughout history. There are only three books on the list that are about men (and here I want to mention Philippe Girard’s Toussaint Louverture: A Revolutionary Life, which I listened to on a long car ride and would highly recommend).

I’m not sure what it is that has me reading mostly biographies of women. It’s not a conscious choice to focus on women. Some of this focus certainly grows out of my scholarly interests; my dissertation was about feminist science fiction and feminist science, after all. Rachel Carson, Judith Merril, James Tiptree, Jr., and Octavia E. Butler are all relevant to that work. But my dissertation didn’t focus on any of these women and didn’t require biographical research anyway.

Certainly there’s also an element of admiration in my choices. All of these are biographies of women whose work I value: Rachel Carson’s scientific work as well as her writing about science; James Tiptree, Jr.’s brilliant and disturbing fiction, much of it reflecting on gender and sex; Judith Merril’s writing and editorial work and the way she helped shape science fiction as a genre; Octavia Butler’s revelations of power in her fiction (I especially love Dawn); Rosa Luxemburg’s fight for freedom and justice. And so on.

Another unfortunate pattern, however, seems to be that the biographies I have enjoyed most (is enjoyed the right word? perhaps not) are those of women who have led somewhat painful, constrained lives: Rachel Carson, James Tiptree, Jr., Octavia Butler, Shirley Jackson.

This pattern seems especially to be highlighted by Ruth Franklin’s recent biography of Shirley Jackson (Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life, 2016), which I just finished reading. Franklin emphasizes Jackson’s always strained relationship with her mother, her feeling of never fitting in anyplace, the hurtful ways her husband (scholar Stanley Hyman) treated her, frequently lukewarm responses to her fiction with a couple of significant exceptions, the tension she felt between her life as wife and mother and her life as writer, her late-in-life agoraphobia and serious anxiety, and her early death. Despite some real success as a writer and what seem like largely positive relationships with her children, Jackson’s life is marked by pain, anxiety, and a sense of her lack of freedom.

Reading her fiction with this in mind is illuminating. For instance, her work frequently circles around the supernatural. She typically stops short of relying on the supernatural as an explanation, but it is always a possibility, and it was something she studied for years.

Witchcraft, whether she practiced it or simply studied it, was important to Jackson for what it symbolized: female strength and potency. The witchcraft chronicles she treasured–written by male historians, often men of the church, who sought to demonstrate that witches presented a serious threat to Christian morality–are stories of powerful women: women who defy social norms, women who get what they desire, women who can channel the power of the devil himself. (261)

Shirley Jackson didn’t identify herself as a feminist, but she certainly fits into a feminist tradition. And Franklin points out how her observations about her own life, as well as her fiction, presage Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique. Like many women of the time, Jackson felt she had little to no control over her own life, little to no say in what was possible. Witchcraft, even as a thought experiment, allowed a window out of that world of control.

Later, Franklin’s discussion of The Haunting of Hill House includes a significant, telling detail about Jackson’s sense of the book and, potentially, about her sense of herself. At one point, Franklin observes that, in her notes, Jackson referred to a particular line as the “key line” of the novel. This line comes after Eleanor has been clutching Theodora’s hand in fear as she hears a child crying for help in the next room. When the lights go on, however, Theodora is not in bed with her but in the bed across the room: “Good God,” Eleanor says, “whose hand was I holding?” This line always gives me chills but I hadn’t considered it as central to the book in the way Jackson apparently did.

Franklin’s interpretation builds upon Jackson’s biography:

The people we hold by the hand are our intimates–parents, children, spouses. To discover oneself clinging to an unidentifiable hand and to ask “Whose hand was I holding?” is to recognize that we can never truly know those with whom we believe ourselves most familiar. One can sleep beside another person for twenty years, as Shirley had with Stanley [Hyman] by this point, and still feel that person to be at times a stranger–and not the “beautiful stranger” of her early story. The hand on the other side of the bed may well seem to belong to a demon. (414)

This is an intriguing reading that I will have to consider when I re-read the novel. Whether I find it convincing as a reading of this line or not, however, it is a compelling take on Shirley’s mindset and the feelings about her marriage she struggled with for many years.

Franklin’s biography – as in these two examples – provides potentially useful ways of reading Shirley Jackson’s work through her biography. The next instance raises questions about the limits of such readings, however.

Late in her life, when she became (temporarily) unable to leave her house, she found herself also unable to write. Franklin writes, tying Jackson’s anxiety to her relationship with Stanley, “It was an issue of control, she thought. How could she wrest control of her life, her mind, back from Stanley? And if she could, would her writing change?” (477). Jackson wrote in her diary at this time, “insecure, uncontrolled, i wrote of neuroses and fear and i think all my books laid end to end would be one long documentation of anxiety.” Her books do all seem to wrestle with anxiety and fear, and this is the source of much of their power. Would she write such books if she were a happier woman? If the world made room for her to be who she needed to be? Likely not. But what other books might she have written instead? Her books gather force from her anxiety and fear, but to leave it there is to discount her talent and skill as a writer. I suspect that a less unhappy version of Shirley Jackson could still have been a brilliant writer, but she might have spoken to different concerns. Or perhaps she would still have reflected these fears, for they are not unique to her or to her situation as a woman in an unhappy marriage in the mid-20th century.

Some of Jackson’s commentary on her own writing from earlier in her life indicates the broader reach of her ideas:

In a publicity memo written for Farrar, Straus around the time The Road Through the Wall appeared–only a month before “The Lottery” was written, if the March date on the draft is accurate–Jackson mentioned her enduring fondness for eighteenth-century English novels because of their “preservation of and insistence on a pattern superimposed precariously on the chaos of human development.” She continued: “I think it is the combination of these two that forms the background of everything I write–the sense which I feel, of a human and not very rational order struggling inadequately to keep in check forces of great destruction, which may be the devil and may be intellectual enlightenment.” In all her writing, the recurrent theme was “an insistence on the uncontrolled, unobserved wickedness of human behavior.” (224)

I take this as a reminder that although her personal demons may have shaped her writing, these feelings and themes are not unique to her or to people with similar problems. In fact, this quote seems to sum up horror fiction in a nutshell: rationality attempts (and fails) to control that which is beyond rational, humanity attempts (and fails) to control itself or its “wickedness.”

Shirley Jackson & Biography I don't often read biographies. I only have 12 books on my Goodreads shelf labelled "biography" that I've actually read, and a couple of those might be stretching the definition a bit (e.g., …

1 note

·

View note

Link

I see a lot of people on this thread asking Should I start this? How does XYZ be able to do it? How do I find the motivation to do it? etc. This is part II of a two-part summary of the book Deep Work by Cal Newport that I wrote for my friend to urge him to read it during the quarantine. I categorize the essence of an entrepreneur into certain core skills. I then read up on books that teach those skills and summarize them for the benefit of my friend and mine. I plan to post the summaries here for yours as well. You can find the first part hereMy friend, the 4DX framework is not a how-to guide for deep work alone. You can apply it to anything you do. Most successful people apply this (Planning, Measuring, Execution & Feedback) in their lives to some extent but some do not realize they were doing it. (unconscious competence)As you will see, deep work is a common skill from Bill Gates, Carl Jung, J K Rowling, Walter Isaacson and every other successful person who has ever achieved something worthwhile. (Walter Isaacson is the biographer of many great 21st century personalities. As an Apple fanboy, You will particularly appreciate that Steve Jobs personally requested him to do his biography)Coming back to our deep work example, You are in IT sales. You want to earn that commission. It means financial freedom to you. If I asked you to measure it, you would probably start measuring sales deals closed/month or revenue earned/month. But as we just learned, these are lag measures. You cannot directly measure them. What should you measure? The Number of leads approached/day. The Number of clients spoken to/day. These are things that you can directly influence daily. If you work on them and do it right, your lag measures (sales deals closed/month) will increase, right? Right. And then you can get the commission you wanted.Tip #1: Plan these things in advanceWhere you'll work and for how longHow you will work once you start to workHow will you support your workAt this point, you might think, isn't this excessive? Do I need to plan out that far? Well, the answer is yes, my friend. Remember our school friend Dan? He makes it a point to start work at 7 am every day. He has a ritual. He reaches his office by 7 am, makes calls to his clients for an hour, and then schedules other work for the day and takes small breaks in between. This ritualistic habit is key to making it work. (Co-incidentally building habits is key - whether it is going to the gym, learning a new language, learning to code, etc - more on this later). Deciding where you will work and then getting there and doing it, will automatically put you in the mood for deep work.How long you will work for is also equally important. This is something you must decide after trying it. Initially, your focus muscle will be weak. So you will find yourself distracted. ( I will teach how to deal with distractions later) So it is important to set timers for yourself (say 25 minutes. I started with 25 minutes a year ago and now I can work for 90 minutes without my mind starting to wander).How will you work once you start to work? - Set rules and processes to keep your effort structured. For example, I will make 5 sales calls per hour. I will not use the internet or my phone until it is over, etcHow will you support your work - Your brain needs all the support it can get for doing deep work. It could be a cup of coffee, a light morning walk or exercise. Our friend, Dan always said that the 30-minute early morning walk kept his mind brisk and his day energetic. What worked for him may not work for you. So from now on, take stock of how clear your thinking is when you do certain activities. I start the day with guided meditation ( I use the headspace app - the free version should do just fine) and it allows me to concentrate. More importantly, it lets me realize when my thoughts have gone on a different track, even when I am not meditating!Tip #2: Make Grand GesturesIn 2007, J K Rowling was struggling to finish her final book - The Deathly Hallows. She recalled in an interview that there was a day when the window cleaner came or the dogs were barking or the kids were at home. She decided to do something extreme to finish her book. She booked a suite at the Balmoral Hotel, located in Edinburgh. And she completed her book there!Back when Bill Gates was still Microsoft CEO, he was famous for taking a 'Think Weeks' holiday. He would leave behind his work and family to stay at a cabin with research papers to think for weeks at a time. He could have done this at his office, but he chose to do it there. He arrived at his famous conclusion that the Internet was going to be the next big thing in the industry there! (seems obvious now).Walter Isaacson and Carl Jung retreat to hard-to-reach places to complete their books or to improve their thinking.You might remember that I go to Starbucks to work on the e-commerce store idea. You scoffed at me for spending so much to do my work there. I was simply using this. I didn't want to say why at the time, because I wasn't sure back then if it would work. I did my feedback sessions (from the 4DX framework) there and plan out the week ahead. It helped me stay on top of my work while leaving enough time to learn new skills. This commitment to deep work is paying off for me with the current pandemic situation, as I can stay on top of my work while learning a new language and learn content marketing as well.Tip #3: Schedule every minute of your dayPeople lack the motivation to do things because they do not know what to do (and when to do it). If you come up with a schedule full of activities focusing on lead measures, you will be very productive. Quite often, disturbances or emergencies pop-up that will ruin your plan for the day. It is important that you do not get frustrated. What you need to do instead is take some time off (after your distraction) to revise your plan for the day. I will share with you my schedule (which I revise weekly, earlier at Starbucks and now at my deep work desk at my home)Tip #4: Be Lazy - Schedule breaks tooReason 1 - Breaks help you get insights on 'stuck' problem: There is a 2008 study by Ap Dijksterhuis called Unconscious Thought Theory. In it, Ap argues that 'contrary to popular belief, decisions about simple issues can be better tackled by conscious thought, whereas decisions about complex matters can be better approached with unconscious thought'. It means that, if you are stuck with a complex problem, it's best to take your mind off of it. You might have seen it in the movies - the trope where the lead character is unable to solve his big problem. He gives in to distraction and does something else. An unrelated remark by the bumbling friend makes him sit up and think. He says - X, You are a genius! and proceeds to work out the solution.Reason 2 - Breaks help you recharge: Stephen and Rachel Kaplan proposed that walking or even looking at pictures of nature aids concentration. They called it Attention Restoration Theory (ART). They validated it through a study done by Berman, Marc & Jonides, John & Kaplan, Stephen and published it in 2009. They let a bunch of people walk through traffic and another bunch of people walk through a park. They were asked to solve problems after some time. The one that went through nature did it faster. They repeated the experiment sometime later. The same people who went on the city walk were now on the nature walk and vice-versa. Again, the people who went on the nature walk were the ones who did the tasks assigned faster.You might argue that walking through a nature park is a pleasant experience, so they repeated the conditions in freezing weather. The people who went through the park still did better than the ones who went through traffic.Reason 3 - Without recharging, you will deplete your concentration muscle: This is simply the negative statement of Reason #2. People think that concentration is simply a question of will-power. Similarly think they will be a rich man one day but it is simply a question of setting their mind to the task. They could not be more wrong! Achieving something requires deliberate practice. And just like how elite athletes schedule breaks after a training session, you must schedule breaks in between your deep work sessions.Tip #5: Embrace Boredom:Boredom is also a way to recharge your concentration. But a lot of people can only last a minute in waiting before picking up their phone. You see this in restaurant queues, grocery lines, etc. but lately, people do this even after they get seated at the table or in family dinners! People constantly crave something to look at. You might remember our mutual friend who was unable to make use of his talents. If you asked him to sit still for a minute, I bet he would crack in 10 seconds before reaching for the phone. Why is this behavior damaging? Because they deplete your concentration muscle!Tip #6: Don't take breaks from distraction, instead take breaks from deep work. Once you are rewired this way, you'll soon crave deep work activities instead of craving breaks.Tip #7: Memorize a Deck of Cards - It doesn't have to be cards, it could be anything - numbers, a new language, etc. It helps your memory and concentration.Strategies for the office worker to include deep-work in their day:Select the right network tools - People use a lot of network tools indiscriminately - Facebook, Instagram, LinkedIn, Twitter, Slack, Reddit, etc. The list goes on. They justify it using the any-benefit approach:You justify using a tool if you can identify any possible benefit to its use, or anything you might miss out on if you don't use it.Cal advises you to use the craftsman approach instead: Identify the core factor that determines success in your professional and personal life. Adopt a tool only if it positively impacts these factors substantially outweigh the negative impacts.Take my case. I deleted Facebook as I decided that having both Facebook and Instagram would be redundant. De-clutter your life from tools that don't help you and eat away your time. And make sure to mute those notifications when you are busy with deep work as those pesky notifications will distract you.Turn off the internet when you work - When you check the internet, even for official things, you will come across an e-mail or an article and soon you will start to respond to the shallow work instead of continuing your deep work. You might have instances where you checked the internet for sending an e-mail and ended up on BuzzFeed's 33 ways this cat made your day article! In our 30-minute scheduling example, you'd work for 25 minutes and take 5 minutes to check the internet and resume work again.Leave the office at by a fixed time - Just as your cellphone leaves you distracted, taking a sneak peek at the e-mail after office hours, continues to work your concentration muscle. So schedule what time you will leave your office and stick to it. have a shutdown ritual - plan for whatever work is pending and move on to your home and stop thinking about work. Revise your schedule if you are unable to stick to it.Become hard-to-reach during your deep work - Due to instant messaging tools, people expect you to reply immediately. It is gratifying for them; damaging for you. Sometimes they may be offended if they can't reach you. It is easier if you tell them an important reason Eg: I was working on something that the boss (or the CEO) asked for urgently.Make people who send you e-mail do more work -Strategy 1 - Check out this contact form.Strategy 2 - If you receive an e-mail that says ' I read the article. What are your thoughts on it?' here is an example response"I will get a draft to you by XYZ date, I'll do my part and add comments for where I need your help. No need to follow up with me in the meantime or reply to the draft I send, unless of course there are issues with it.Strategy 3 - Don't respond. If it was important, they will follow back anyway. Unless of course, it is an e-mail from your boss or CEO.

0 notes

Photo

HOMEWORK (DUE 9/27):

Please read “Notes to My Biographer” by Adam Haslett (posted below), and answer the questions on the study guide (also posted below).

NOTES TO MY BIOGRAPHER

A short story by Adam Haslett

Two things to get straight from the beginning: I hate doctors and have never joined a support group in my life. At seventy-three, I’m not about to change. The mental-health establishment can go screw itself on a barren hilltop in the rain before I touch their snake oil or listen to the visionless chatter of men half my age. I have shot Germans in the fields of Normandy, filed twenty-six patents, married three women, survived them all, and am currently the subject of an investigation by the IRS, which has about as much chance of collecting from me as Shylock did of getting his pound of flesh. Bureaucracies have trouble thinking clearly. I, on the other hand, am perfectly lucid.

Note, for instance, the way I obtained the Saab I am presently driving into the Los Angeles basin: a niece in Scottsdale lent it to me. Do you think she’ll ever see it again? Unlikely. Of course, when I borrowed it from her I had every intention of returning it, and in a few days or weeks I may feel that way again, but for now forget her and her husband and three children who looked at me over the kitchen table like I was a museum piece sent to bore them. I could run circles around those kids. They’re spoon-fed Ritalin and private schools and have eyes that say, Give me things I don’t have. I wanted to read them a book on the history of the world, its immigrations, plagues, and wars, but the shelves of their outsized condominium were full of ceramics and biographies of the stars. The whole thing depressed the hell out of me and I’m glad to be gone.

A week ago I left Baltimore with the idea of seeing my son Graham. I’ve been thinking about him a lot recently, days we spent together in the barn at the old house, how with him as my audience ideas came quickly, and I don’t know when I’ll get to see him again. I thought I might as well catch up with some of the other relatives along the way. I planned to start at my daughter Linda’s in Atlanta, but when I arrived it turned out she’d moved. I called Graham, and when he got over the shock of hearing my voice, he said Linda didn’t want to see me. By the time my younger brother Ernie refused to do anything more than have lunch with me after I had taken a bus all the way to Houston, I began to get the idea that this episodic reunion thing might be more trouble than it was worth. Scottsdale did nothing to alter my opinion. These people seem to think they’ll have another chance, that I’ll be coming around again. The fact is I’ve completed my will, made bequests of my patent rights, and am now just composing a few notes to my biographer, who, in a few decades, when the true influence of my work becomes apparent, may need them to clarify certain issues.

Franklin Caldwell Singer, b. 1924, Baltimore, Maryland.

Child of a German machinist and a banker’s daughter.

My psych discharge following “desertion” in Paris was trumped up by an army intern resentful of my superior knowledge of the diagnostic manual. The nude-dancing incident at the Louvre in a room full of Rubenses had occurred weeks earlier and was of a piece with other celebrations at the time.

B.A., Ph.D., Engineering, The Johns Hopkins University.

1952. First and last electroshock treatment, for which I will never, never, never forgive my parents.

Researcher, Eastman Kodak Laboratories. As with so many institutions in this country, talent was resented. I was fired as soon as I began to point out flaws in the management structure. Two years later I filed a patent on a shutter mechanism that Kodak eventually broke down and purchased (then?Vice President for Product Development Arch Vendellini was having an affair with his daughter’s best friend, contrary to what he will tell you. Notice the way his left shoulder twitches when he is lying).

All subsequent diagnoses—and let me tell you, there have been a number—are the result of two forces, both in their way pernicious. 1) The attempt by the psychiatric establishment over the last century to redefine eccentricity as illness, and 2) the desire of members of my various families to render me docile and if possible immobile.

The electric-bread-slicer concept was stolen from me by a man in a diner in Chevy Chase dressed as a reindeer whom I could not possibly have known was an employee of Westinghouse.

That I have no memories of the years 1988?90 and believed until very recently that Ed Meese was still the attorney general is not owing to my purported paranoid blackout but, on the contrary, the fact that my third wife took it upon herself to lace my coffee with tranquilizers. Believe nothing you hear about the divorce settlement.

When I ring the buzzer at Graham’s place in Venice, a Jew in his late twenties with some fancy-looking musculature answers the door. He appears nervous and says, “We weren’t expecting you till tomorrow,” and I ask him who they are and he says, “Me and Graham,” adding hurriedly, “We’re friends, you know, only friends. I don’t live here, I’m just over to use the computer.”

All I can think is I hope this guy isn’t out here trying to get acting jobs, because it’s obvious to me right away that my son is gay and is screwing this character with the expensive-looking glasses. There was a lot of that in the military and I learned early on that it comes in all shapes and sizes, not just the fairy types everyone expects. Nonetheless, I am briefly shocked by the idea that my twenty-nine-year-old boy has never seen fit to share with me the fact that he is a fruitcake—no malice intended—and I resolve right away to talk to him about it when I see him. Marlon Brando overcomes his stupor and lifting my suitcase from the car he leads me through the back garden past a lemon tree in bloom to a one-room cottage with a sink and plenty of light to which I take an instant liking.

“This will do nicely,” I say, and then I ask him, “How long have you been sleeping with my son?” It’s obvious he thinks I’m some brand of geriatric homophobe getting ready to come on in a religiously heavy manner, and seeing that deer-caught-in-the-headlights look in his eye I take pity and disabuse him. I’ve seen women run down by tanks. I’m not about to get worked up about the prospect of fewer grandchildren. When I start explaining to him that social prejudice of all stripes runs counter to my Enlightenment ideals—ideals tainted by centuries of partial application—it becomes clear to me that Graham has given him the family line. His face grows patient and his smile begins to leak the sympathy of the ignorant: poor old guy suffering from mental troubles his whole life, up one month, down the next, spewing grandiose notions that slip like sand through his fingers to which I always say, you just look up Frank Singer at the U.S. Patent Office. In any case, this turkey probably thinks the Enlightenment is a marketing scheme for General Electric; I spare him the seminar I could easily conduct and say, “Look, if the two of you share a bed, it’s fine with me.”

“That drive must have worn you out,” he says hopefully. “Do you want to lie down for a bit?”

I tell him I could hook a chain to my niece’s Saab and drag it through a marathon. This leaves him nonplussed. We walk back across the yard together into the kitchen of the bungalow. I ask him for pen, paper, and calculator and begin sketching an idea that came to me just a moment ago—I can feel the presence of Graham already—for a bicycle capable of storing the energy generated on the downward slope in a small battery and releasing it through a handlebar control when needed on the uphill, a potential gold mine when you consider the aging population and the increase in leisure time created by early retirement. I have four pages of specs and the estimated cost of a prototype done by the time Graham arrives two hours later. He walks into the kitchen wearing a blue linen suit with a briefcase held to his chest and seeing me at the table goes stiff as a board. I haven’t seen him in five years and the first thing I notice is that he’s got bags under his eyes and he looks exhausted. When I open my arms to embrace him he takes a step backward.

“What’s the matter?” I ask. Here is my child wary of me in a strange kitchen in California, his mother’s ashes spread long ago over the Potomac, the objects of our lives together stored in boxes or sold.

“You actually came,” he says.

“I’ve invented a new bicycle,” I say, but this seems to reach him like news of some fresh death. Ben hugs Graham there in front of me. I watch my son rest his head against this fellow’s shoulder like a tired soldier on a train. “It’s going to have a self-charging battery,” I say, sitting again at the table to review my sketches.

~

With Graham here my idea is picking up speed, and while he’s in the shower I unpack my bags, rearrange the furniture in the cottage, and tack my specs to the wall. Returning to the house, I ask Ben if I can use the phone and he says that’s fine, and then he tells me, “Graham hasn’t been sleeping so great lately, but I know he really does want to see you.”

“Sure, no hard feelings, fine.”

"He’s been dealing with a lot recently . . . maybe some things you could talk to him about … and I think you might—"

“Sure, sure, no hard feelings,” and then I call my lawyer, my engineer, my model builder, three advertising firms whose numbers I find in the yellow pages, the American Association of Retired Persons—that market will be key—an old college friend who I remember once told me he’d competed in the Tour de France, figuring he’ll know the bicycle-industry angle, my bank manager to discuss financing, the Patent Office, the Cal Tech physics lab, the woman I took to dinner the week before I left Baltimore, and three local liquor stores before I find one that will deliver a case of Dom Pérignon.

“That’ll be for me!” I call out to Graham as he emerges from the bedroom to answer the door what seems only minutes later. He moves slowly and seems sapped of life.

“What’s this?”

“We’re celebrating! There’s a new project in the pipeline!”

Graham stares at the bill as though he’s having trouble reading it. Finally, he says, “This is twelve hundred dollars. We’re not buying it.”

I tell him Schwinn will drop that on donuts for the sales reps when I’m done with this bike, that Oprah Winfrey’s going to ride it through the halftime show at the Super Bowl.