#I still have SO MANY QUESTIONS about what police abolition is

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Note

You talk about getting rid of the psychiatric system. But what do you propose should be done instead? /gen

I'm going to tell you a story . I once knew someone called Tim. When I met him he had already spent most of his life in drug addiction treatment centres, psych wards and prisons until he later ended up in a forensic psych ward. After he did LSD he 'never came down from his bad trip' and got diagnosed w schizophrenia. This diagnosis +the addict - diagnosis justified so many fucking human rights violations - it got him locked up, drugged up, strip searched, his privacy violated on a daily basis, isolated away from society and everyone he knew because apparently he needed to be 'saved from this illness in his brain that makes him do/think/feel' things he otherwise wouldnt and because he needed to be 'punished' into being a 'functioning', 'productive' (read: profit-generating) member of 'society' (read: hegemonic cultural norms & forms.) This is what psychiatry does - it doesnt help, it locks us up and tortures us. I dont need to be able to name alternatives to this lol . This is the worst possible way of treating anyone ever. It would help immensely to literally just STOP doing this. Even 'sane' people would go insane in places like these.

So the alternative to acting like an absolute asshole towards people who struggle severely and who dont have a place in society would be to 1)not isolate them away from society and 2)not torture them 🙏 . It would be to get rid off the psychologists' individual and the psychiatric systems' general saviour complex that only results in abusing people bc they act like the people who are labelled as mentally ill are (=their minds/brains) responsible for at fault for their own struggles. Instead we could show solidarity with each other and try to built a world where everyone has a place in and is valued as a person and where the suffering/madness of an individual is not seen as an incentive to literally abuse and socially ostracize them.

And @ everyone dont come at me w 'not everyone has these experiences w psychiatry' - any time you talk about systemic criticism you have to look at the most marginalized experiences. When talking about police defunding/prison abolition we also talk about police brutality that black disabled poor people face . And yes not everyone has bad experiences w every single cop , still ACAB . ALSO dont come at me with 'I know there ar GOOD psychologists who Actually want to help' ,1) fuck their savior complex 2)what individuals motives are for joining this system of oppression isnt necessarily the purpose of a system. The purpose of a system is what it does. The police isnt there to protect us, psychiatry isnt there to help us. We only have each other.

So, what you can do right now to get rid off the psychiatric system in your community? How can we stop relying on this authoritarian system that abuses and incarcerates so many of us ??

I think its important to educate each other on our rights. Because then we have the knowledge on what not to say in a therapy session so we dont get incarcerated or what to do when we are questioned by cops/psychs to see if we are 'at risk' or what to do when we or friends of us are already incarcerated so they can get out of there as fast as possible. Also educating your friends/family on psychiatric propaganda helps - a common myth is that if you dont 'look for signs' and call the cops to institutionalize a friend they might kill themselves. All while institutionalization/incarceration increases the risk of suicide extremely. This is important to know so no one in our communities calls the cops on us when we're doing really bad. Also educating each other on the biomedical model so everyone understands that we dont have an illness that we need to be 'saved from' (depression for example) or 'punished for' (aspd, drug addiction) and that we (=our minds/brains) arent to blame for our struggles Etc.

If you know that youre sometimes in extreme mental distress/pain you could also make a crisis plan with friends so you dont need to rely on the psych system - like for example the plan could be that a friend calls in sick for work/university and then stays at your place for 3-4days and is there for you/drinks tea w you, goes for a walk together w you, smokes a joint with you together until you feel better and arent acutely suicidal anymore. (Its also best to include several people in this plan bc it can get really overwhelming for 1 person). You can als include things in the plan like asking your friends to take away all knives in your apartment if you want to. Or if its a more permanent 'crisis' then a plan on how to move together with friends to get away from your nuclear family/abusive partner (just as an example).

Access to medication, knowledge on how to get off of them if you dont want to take them anymore and freedom and proper education in your decision on taking, weaning off or on staying on medication is not given in the psych system. So how do we change that? A common reason for 'crisis' is trying to wean off of psychiatric drugs (a lot of people get suicidal or psychotic bc of the withdrawal for example - depends on the meds, dosis and since how long youve been taking them though). You could plan when to do this together w friends. Theres anti psych guidelines on how to do this safely - a lot of psychiatrists tell you that you need to stay on meds no matter if you want to or not and they often dont know how to wean off of them or think youre 'at risk' and incarcerate you if you mention that you want to stop taking your meds -this highly depends on how stigmatizing your diagnosis is (=schizophrenia/bipolar are good examples for highly stigmatized ones) or if youre sb who get racialized for example (bc then psychs immediatly perceive you as more of 'a risk'). You could make a plan for example where you ask your friends to stay w you through this by living at your apartment w you for a few days, cooking meals for you and keeping your apartment clean. And then another friend of you could come by each day after work (for example) and also be there since its probably a lot for one person. Also LYING to psychiatrists is always a good idea. For example when youre trans and want to access gender affirming care its important not to mention any diagnoses in general but especially diagnoses like autism, schizophrenia, psychosis or PDs and then literally lie about yourself if necessary. You always know who you are and what you need best. Also dont blindly trust your psych on what medications go well together - look it up yourself !!! Theres a 'drug interaction checker' online where you can see if it might be dangerous to take certain meds at the same time. Also READ on what side effects are possible - make a diary for when you start your medication on how youre feeling/doing . Some changes are awful but still hard to notice bc youre thinking that it could also be a 'normal' worsening of your mental state that you think you might also have without meds. Also depending on what physical conditions you have/had you cant take some medications without it being dangerous - READ the whole instruction paper thing that always comes with your meds and/or google it !!

Also literally just sharing/collecting tips on how to cope w different struggles + harm reduction guides (suicidality, drug addiction, ...) is very helpful. There is a lot of community sourced material already out there.

I understand that the reason most people are severely struggling is because they dont have a community (=like when you only have 1 partner or 1 friend ,because youre (still) legal property of your parents, because youre stuck in a nuclear family,...) and not only because psychiatry divides our communities by blaming us for our struggles and isolating and stigmatizing us. Building community and relying on each other is the only way to get rid off the psychiatric system in the end. If we already had a real community that we could rely on, all the psych wards would be empty and therapists wouldnt exist. This is not the first step, its the solution.

Als there are already alternative institutions (that are already in practice) that are a replacement for psychiatry.

This is probably the answer that youre looking for 😂. I dont really care about these kind of anti psych concepts and practices since they seem out of my reach atm. Ik that theres an anti psych house in berlin whos guiding principles are 1)community care /peer support 2)full autonomy for everyone there and its specifically for people who are running away from psychiatric violence.

Other alternatives that I havent really looked into yet are : bethel house , peer respites, new models of therapy

241 notes

·

View notes

Text

there are many weird reactionary ways in which people fetishise discipline/consequences of kids as like, giving them what they deserve, or necessary for 'toughening them up', but at the end of the day a healthy philosophy of 'discipline' is basically just about setting and maintaining boundaries

as adults, there are a lot of rules, whether as law or in the workplace or in public spaces, that we kinda just accept nobody really cares about. the reason wacky articles about how it's illegal to flush a public toilet in public in Missouri or whatever inspire laughter rather than horror is bc we know these laws are so patently absurd nobody would enforce them.

on the other hand, there are lots of placrs a few years ago, that would be plastered in posters advising you to wear a mask and social distance, and yet because they had absolutely no follow through from anyone only ever remained at the level of polite request. today there are places that still have these posters up, but because there's no follow through everyone assumes they're just a relic of the past and not an actual ongoing request.

that follow through doesn't have to be punitive. it could be simply having someone who reminds visitors to wear masks and socially distance (altho the question is then how to escalate if this doesnt work). but for anyone, adult or child, setting an expectation and then not following through on it communicates that you don't care.

that's true in many contexts. you can tell shitty parents their behaviour is unacceptable, but it's a total bluff unless you actually enforce those boundaries. it's all well and good if a retail store has posters up saying please don't abuse our staff but if management don't have your back when abuse happens then it's obvious what their real priorities are.

and for kids it's even more of a thing that they can discern as easily what's a real expectation you actually care about, and what you're just saying. it can feel confusing and unfair if you give them a list of rules and then only enforce the ones you really care about. it's like you have some arbitrary secret set of rules.

contra the discipline fetishists, the severity of the punishment isn't really a central issue here. some level of proportionality helps to communicate how strongly this expectation matters; it makes sense that interrupting someone else would get a talking to and pushing your sister down the stairs would get a time out. but consistency of following through, imo, seems far more important in teaching kids pro social behaviours than severity of consequences.

often from people who are pro prison abolition you see mixed feelings abt stuff like, say, killer cops getting off without a jail sentence. but I think it can be true both that people can be opposed to prison as a concept, and also that, in a world where 'prison' is our main go-to for communicating 'we consider this behaviour unacceptable', letting serious crimes off without jail time ends up conveying the message 'this is OK'. and the frustration is not so much that prison abolitionists think that murder inherently deserves jail, so much as that by the standards of the system of consequences the world runs on, the judicial system is saying 'police brutality is fine.' not about the severity of the punishment per se, but the follow through

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

When The New York Times Lost Its Way! America’s Media Should Do More To Equip Readers To Think For Themselves

— 1843 Magazine | December 14th, 2023 | By James Bennet

Are we truly so precious?” Dean Baquet, the executive editor of the New York Times, asked me one Wednesday evening in June 2020. I was the editorial-page editor of the Times, and we had just published an op-ed by Tom Cotton, a senator from Arkansas, that was outraging many members of the Times staff. America’s conscience had been shocked days before by images of a white police officer kneeling on the neck of a black man, George Floyd, until he died. It was a frenzied time in America, assaulted by covid-19, scalded by police barbarism. Throughout the country protesters were on the march. Substantive reform of the police, so long delayed, suddenly seemed like a real possibility, but so did violence and political backlash. In some cities rioting and looting had broken out.

It was the kind of crisis in which journalism could fulfil its highest ambitions of helping readers understand the world, in order to fix it, and in the Times’s Opinion section, which I oversaw, we were pursuing our role of presenting debate from all sides. We had published pieces arguing against the idea of relying on troops to stop the violence, and one urging abolition of the police altogether. But Cotton, an army veteran, was calling for the use of troops to protect lives and businesses from rioters. Some Times reporters and other staff were taking to what was then called Twitter, now called X, to attack the decision to publish his argument, for fear he would persuade Times readers to support his proposal and it would be enacted. The next day the Times’s union—its unit of the NewsGuild-cwa—would issue a statement calling the op-ed “a clear threat to the health and safety of the journalists we represent”.

The Times had endured many cycles of Twitter outrage for one story or opinion piece or another. It was never fun; it felt like sticking your head in a metal bucket while people were banging it with hammers. The publisher, A.G. Sulzberger, who was about two years into the job, understood why we’d published the op-ed. He had some criticisms about packaging; he said the editors should add links to other op-eds we’d published with a different view. But he’d emailed me that afternoon, saying: “I get and support the reason for including the piece,” because, he thought, Cotton’s view had the support of the White House as well as a majority of the Senate. As the clamour grew, he asked me to call Baquet, the paper’s most senior editor.

Whether or not American democracy endures, a central question historians are sure to ask about this era is why America came to elect Donald Trump, promoting him from a symptom of the country’s institutional, political and social degradation to its agent-in-chief

Like me, Baquet seemed taken aback by the criticism that Times readers shouldn’t hear what Cotton had to say. Cotton had a lot of influence with the White House, Baquet noted, and he could well be making his argument directly to the president, Donald Trump. Readers should know about it. Cotton was also a possible future contender for the White House himself, Baquet added. And, besides, Cotton was far from alone: lots of Americans agreed with him—most of them, according to some polls. “Are we truly so precious?” Baquet asked again, with a note of wonder and frustration.

The answer, it turned out, was yes. Less than three days later, on Saturday morning, Sulzberger called me at home and, with an icy anger that still puzzles and saddens me, demanded my resignation. I got mad, too, and said he’d have to fire me. I thought better of that later. I called him back and agreed to resign, flattering myself that I was being noble.

Whether or not American democracy endures, a central question historians are sure to ask about this era is why America came to elect Donald Trump, promoting him from a symptom of the country’s institutional, political and social degradation to its agent-in-chief. There are many reasons for Trump’s ascent, but changes in the American news media played a critical role. Trump’s manipulation and every one of his political lies became more powerful because journalists had forfeited what had always been most valuable about their work: their credibility as arbiters of truth and brokers of ideas, which for more than a century, despite all of journalism’s flaws and failures, had been a bulwark of how Americans govern themselves.

I hope those historians will also be able to tell the story of how journalism found its footing again – how editors, reporters and readers, too, came to recognise that journalism needed to change to fulfil its potential in restoring the health of American politics. As Trump’s nomination and possible re-election loom, that work could not be more urgent.

I think Sulzberger shares this analysis. In interviews and his own writings, including an essay earlier this year for the Columbia Journalism Review, he has defended “independent journalism”, or, as I understand him, fair-minded, truth-seeking journalism that aspires to be open and objective. It’s good to hear the publisher speak up in defence of such values, some of which have fallen out of fashion not just with journalists at the Times and other mainstream publications but at some of the most prestigious schools of journalism. Until that miserable Saturday morning I thought I was standing shoulder-to-shoulder with him in a struggle to revive them. I thought, and still think, that no American institution could have a better chance than the Times, by virtue of its principles, its history, its people and its hold on the attention of influential Americans, to lead the resistance to the corruption of political and intellectual life, to overcome the encroaching dogmatism and intolerance.

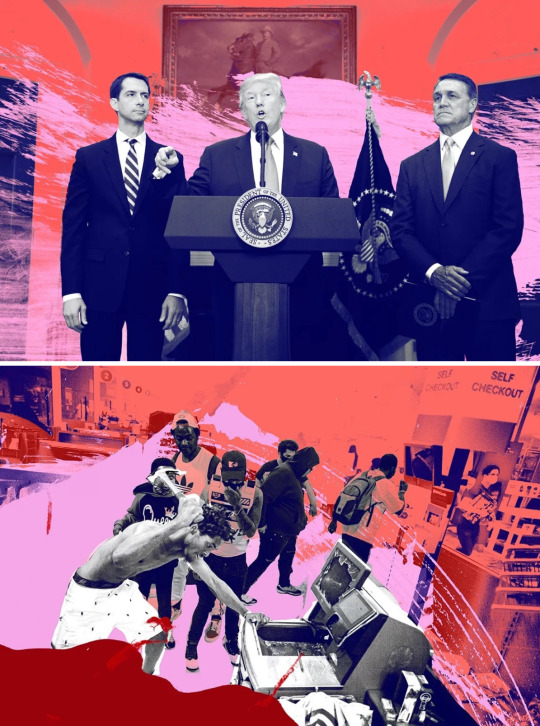

Tom Cotton speaking at the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence in 2020 (Top). James Bennet (Second Left) with Hillary Clinton (Far Right) on Her Trip as First Lady to North Africa in 1999 (Bottom).

But Sulzberger seems to underestimate the struggle he is in, that all journalism and indeed America itself is in. In describing the essential qualities of independent journalism in his essay, he unspooled a list of admirable traits – empathy, humility, curiosity and so forth. These qualities have for generations been helpful in contending with the Times’s familiar problem, which is liberal bias. I have no doubt Sulzberger believes in them. Years ago he demonstrated them himself as a reporter, covering the American Midwest as a real place full of three-dimensional people, and it would be nice if they were enough to deal with the challenge of this era, too. But, on their own, these qualities have no chance against the Times’s new, more dangerous problem, which is in crucial respects the opposite of the old one.

The Times’s problem has metastasised from liberal bias to illiberal bias, from an inclination to favour one side of the national debate to an impulse to shut debate down altogether. All the empathy and humility in the world will not mean much against the pressures of intolerance and tribalism without an invaluable quality that Sulzberger did not emphasise: courage.

Don’t get me wrong. Most journalism obviously doesn’t require anything like the bravery expected of a soldier, police officer or protester. But far more than when I set out to become a journalist, doing the work right today demands a particular kind of courage: not just the devil-may-care courage to choose a profession on the brink of the abyss; not just the bulldog courage to endlessly pick yourself up and embrace the ever-evolving technology; but also, in an era when polarisation and social media viciously enforce rigid orthodoxies, the moral and intellectual courage to take the other side seriously and to report truths and ideas that your own side demonises for fear they will harm its cause.

One of the glories of embracing illiberalism is that, like Trump, you are always right about everything, and so you are justified in shouting disagreement down. In the face of this, leaders of many workplaces and boardrooms across America find that it is so much easier to compromise than to confront – to give a little ground today in the belief you can ultimately bring people around. This is how reasonable Republican leaders lost control of their party to Trump and how liberal-minded college presidents lost control of their campuses. And it is why the leadership of the New York Times is losing control of its principles.

It is hard to imagine a path back to saner American politics that does not traverse a common ground of shared fact

Over the decades the Times and other mainstream news organisations failed plenty of times to live up to their commitments to integrity and open-mindedness. The relentless struggle against biases and preconceptions, rather than the achievement of a superhuman objective omniscience, is what mattered. As everyone knows, the internet knocked the industry off its foundations. Local newspapers were the proving ground between college campuses and national newsrooms. As they disintegrated, the national news media lost a source of seasoned reporters and many Americans lost a journalism whose truth they could verify with their own eyes. As the country became more polarised, the national media followed the money by serving partisan audiences the versions of reality they preferred. This relationship proved self-reinforcing. As Americans became freer to choose among alternative versions of reality, their polarisation intensified. When I was at the Times, the newsroom editors worked hardest to keep Washington coverage open and unbiased, no easy task in the Trump era. And there are still people, in the Washington bureau and across the Times, doing work as fine as can be found in American journalism. But as the top editors let bias creep into certain areas of coverage, such as culture, lifestyle and business, that made the core harder to defend and undermined the authority of even the best reporters.

There have been signs the Times is trying to recover the courage of its convictions. The paper was slow to display much curiosity about the hard question of the proper medical protocols for trans children; but once it did, the editors defended their coverage against the inevitable criticism. For any counter-revolution to succeed, the leadership will need to show courage worthy of the paper’s bravest reporters and opinion columnists, the ones who work in war zones or explore ideas that make illiberal staff members shudder. As Sulzberger told me in the past, returning to the old standards will require agonising change. He saw that as the gradual work of many years, but I think he is mistaken. To overcome the cultural and commercial pressures the Times faces, particularly given the severe test posed by another Trump candidacy and possible presidency, its publisher and senior editors will have to be bolder than that.

Since Adolph Ochs bought the paper in 1896, one of the most inspiring things the Times has said about itself is that it does its work “without fear or favour”. That is not true of the institution today – it cannot be, not when its journalists are afraid to trust readers with a mainstream conservative argument such as Cotton’s, and its leaders are afraid to say otherwise. As preoccupied as it is with the question of why so many Americans have lost trust in it, the Times is failing to face up to one crucial reason: that it has lost faith in Americans, too.

For now, to assert that the Times plays by the same rules it always has is to commit a hypocrisy that is transparent to conservatives, dangerous to liberals and bad for the country as a whole. It makes the Times too easy for conservatives to dismiss and too easy for progressives to believe. The reality is that the Times is becoming the publication through which America’s progressive elite talks to itself about an America that does not really exist.

It is hard to imagine a path back to saner American politics that does not traverse a common ground of shared fact. It is equally hard to imagine how America’s diversity can continue to be a source of strength, rather than become a fatal flaw, if Americans are afraid or unwilling to listen to each other. I suppose it is also pretty grandiose to think you might help fix all that. But that hope, to me, is what makes journalism worth doing.

The New York Times taught me how to do daily journalism. I joined the paper, for my first stint, in the pre-internet days, in an era of American journalism so different that it was almost another profession. Back in 1991 the Times was anxious not about a print business that was collapsing but about an industry so robust that Long Island Newsday was making a push into New York City. A newspaper war was under way, and the Times was fighting back by expanding its Metro desk, hiring reporters and opening bureaus in Brooklyn, Queens and the Bronx.

Metro was the biggest news desk. New reporters had to do rotations of up to a year there to learn the culture and folkways of the paper. Baquet, surely among the greatest investigative journalists America has produced, was then in Metro. I was brought on as a probationary reporter, with a year to prove myself, and like other new hires was put through a series of assignments at the low end of the hierarchy.

After about six months the Metro editor, Gerald Boyd, asked me to take a walk with him, as it turned out, to deliver a harsh lesson in Timesian ambition and discipline. Chain-smoking, speaking in his whispery, peculiarly high-pitched voice, he kicked my ass from one end of Times Square to the other. He had taken a chance hiring me, and he was disappointed. There was nothing special about my stories. At the rate I was going, I had no chance of making it onto the paper.

The next day was a Saturday, and I reached Boyd at home through the Metro desk to rattle off the speech I’d endlessly rehearsed while staring at the ceiling all night. The gist was that the desk had kept me chasing small-bore stories, blah blah blah. Boyd sounded less surprised than amused to hear from me, and soon gave me a new assignment, asking me to spend three months covering the elderly, one of several new “mini-beats” on subjects the desk had overlooked.

I was worried there were good reasons this particular beat had been ignored. At 26, as one of the youngest reporters on the desk, I was also not an obvious candidate for the role of house expert on the wise and grey. But Boyd assigned me to an excellent editor, Suzanne Daley, and as I began studying the city’s elderly and interviewing experts and actual old people, I began to discover the rewards granted any serious reporter: that when you acknowledge how little you know, looking in at a world from the outside brings a special clarity.

The Times is becoming the publication through which America’s progressive elite talks to itself about an America that does not really exist

The subject was more complicated and richer than I imagined, and every person had stories to tell. I wrote about hunger, aids and romance among the elderly, about old comedians telling old jokes to old people in senior centres. As I reported on Jews who had fled Germany to settle in Washington Heights or black Americans who had left the Jim Crow south to settle in Bushwick, Brooklyn, it dawned on me that, thanks to Boyd, I was covering the history of the world in the 20th century through the eyes of those who had lived it.

After joining the permanent staff, I went, again in humbling ignorance, to Detroit, to cover the auto companies’ – and the city’s – struggle to recapture their former glory. And again I had a chance to learn, in this case, everything from how the largest companies in the world were run, to what it was like to work the line or the sales floor, to the struggle and dignity of life in one of America’s most captivating cities. “We still have a long way to go,” Rosa Parks told me, when I interviewed her after she had been robbed and beaten in her home on Detroit’s west side one August night in 1994. “And so many of our children are going astray.”

I began to write about presidential politics two years later, in 1996, and as the most inexperienced member of the team was assigned to cover a long-shot Republican candidate, Pat Buchanan. I packed a bag for a four-day reporting trip and did not return home for six weeks. Buchanan campaigned on an eccentric fusion of social conservatism and statist economic policies, along with coded appeals to racism and antisemitism, that 30 years earlier had elevated George Wallace and 20 years later would be rebranded as Trumpism. He also campaigned with conviction, humour and even joy, a combination I have rarely witnessed. As a Democrat from a family of Democrats, a graduate of Yale and a blossom of the imagined meritocracy, I had my first real chance, at Buchanan’s rallies, to see the world through the eyes of stalwart opponents of abortion, immigration and the relentlessly rising tide of modernity.

The task of making the world intelligible was even greater in my first foreign assignment. I arrived in Jerusalem a week before the attacks of September 11th 2001, just after the second intifada had broken out. I had been to the Middle East just once, as a White House reporter covering President Bill Clinton. “Well, in at the deep end,” the foreign editor, Roger Cohen, told me before I left. To spend time with the perpetrators and victims of violence in the Middle East, to listen hard to the reciprocal and reinforcing stories of new and ancient grievances, is to confront the tragic truth that there can be justice on more than one side of a conflict. More than ever, it seemed to me that a reporter gave up something in renouncing the taking of sides: possibly the moral high ground, certainly the psychological satisfaction of righteous anger.

Pat Buchanan during the New Hampshire primary (Top). A.G. Sulzberger, Publisher of the New York Times (Right).

But there was a compensating moral and psychological privilege that came with aspiring to journalistic neutrality and open-mindedness, despised as they might understandably be by partisans. Unlike the duelling politicians and advocates of all kinds, unlike the corporate chieftains and their critics, unlike even the sainted non-profit workers, you did not have to pretend things were simpler than they actually were. You did not have to go along with everything that any tribe said. You did not have to pretend that the good guys, much as you might have respected them, were right about everything, or that the bad guys, much as you might have disdained them, never had a point. You did not, in other words, ever have to lie.

This fundamental honesty was vital for readers, because it equipped them to make better, more informed judgments about the world. Sometimes it might shock or upset them by failing to conform to their picture of reality. But it also granted them the respect of acknowledging that they were able to work things out for themselves.

What a gift it was to be taught and trusted as I was by my editors – to be a reporter with licence to ask anyone anything, to experience the whole world as a school and every source and subject as a teacher. I left after 15 years, in 2006, when I had the chance to become editor of the Atlantic. Rather than starting out on yet another beat at the Times, I felt ready to put my experience to work and ambitious for the responsibility to shape coverage myself. It was also obvious how much the internet was changing journalism. I was eager to figure out how to use it, and anxious about being at the mercy of choices by others, in a time not just of existential peril for the industry, but maybe of opportunity.

The Atlantic did not aspire to the same role as the Times. It did not promise to serve up the news of the day without any bias. But it was to opinion journalism what the Times’s reporting was supposed to be to news: honest and open to the world. The question was what the magazine’s 19th-century claim of intellectual independence – to be “of no party or clique” – should mean in the digital era.

A journalism that starts out assuming it knows the answers can be far less valuable to the reader than a journalism that starts out with a humbling awareness that it knows nothing

Those were the glory days of the blog, and we hit on the idea of creating a living op-ed page, a collective of bloggers with different points of view but a shared intellectual honesty who would argue out the meaning of the news of the day. They were brilliant, gutsy writers, and their disagreements were deep enough that I used to joke that my main work as editor was to prevent fistfights.

The lessons we learned from adapting the Atlantic to the internet washed back into print. Under its owner, David Bradley, my colleagues and I distilled our purpose as publishing big arguments about big ideas. We made some mistakes – that goes along with any serious journalism ambitious to make a change, and to embrace change itself – but we also began producing some of the most important work in American journalism: Nicholas Carr on whether Google was “making us stupid”; Hanna Rosin on “the end of men”; Taylor Branch on “the shame of college sports”; Ta-Nehisi Coates on “the case for reparations”; Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt on “the coddling of the American mind”.

I was starting to see some effects of the new campus politics within the Atlantic. A promising new editor had created a digital form for aspiring freelancers to fill out, and she wanted to ask them to disclose their racial and sexual identity. Why? Because, she said, if we were to write about the trans community, for example, we would ask a trans person to write the story. There was a good argument for that, I acknowledged, and it sometimes might be the right answer. But as I thought about the old people, auto workers and abortion opponents I had learned from, I told her there was also an argument for correspondents who brought an outsider’s ignorance, along with curiosity and empathy, to the story.

A journalism that starts out assuming it knows the answers, it seemed to me then, and seems even more so to me now, can be far less valuable to the reader than a journalism that starts out with a humbling awareness that it knows nothing. “In truly effective thinking”, Walter Lippmann wrote 100 years ago in “Public Opinion”, “the prime necessity is to liquidate judgments, regain an innocent eye, disentangle feelings, be curious and open-hearted.” Alarmed by the shoddy journalism of his day, Lippmann was calling for journalists to struggle against their ignorance and assumptions in order to help Americans resist the increasingly sophisticated tools of propagandists. As the Atlantic made its digital transition, one thing I preached was that we could not cling to any tradition or convention, however hallowed, for its own sake, but only if it was relevant to the needs of readers today. In the age of the internet it is hard even for a child to sustain an “innocent eye”, but the alternative for journalists remains as dangerous as ever, to become propagandists. America has more than enough of those already.

What we did together at the Atlantic worked. We dramatically increased the magazine’s audience and influence while making it profitable for the first time in generations. After I had spent ten years as editor, the last few as co-president, the publisher, A.G. Sulzberger’s father, also an Arthur Sulzberger, asked me to return to the Times as editorial-page editor.

His offer, I thought, would give me the chance to do the kind of journalism I loved with more resources and greater effect. The freedom Opinion had to experiment with voice and point of view meant that it would be more able than the Times newsroom to take advantage of the tools of digital journalism, from audio to video to graphics. Opinion writers could also break out of limiting print conventions and do more in-depth, reported columns and editorials. Though the Opinion department, which then had about 100 staff, was a fraction the size of the newsroom, with more than 1,300, Opinion’s work had outsized reach. Most important, the Times, probably more than any other American institution, could influence the way society approached debate and engagement with opposing views. If Times Opinion demonstrated the same kind of intellectual courage and curiosity that my colleagues at the Atlantic had shown, I hoped, the rest of the media would follow.

No doubt Sulzberger’s offer also appealed not just to my loyalty to the Times, but to my ambition as well. I would report directly to the publisher, and I was immediately seen, inside and outside the paper, as a candidate for the top job. I had hoped being in Opinion would exempt me from the infamous political games of the newsroom, but it did not, and no doubt my old colleagues felt I was playing such games myself. Fairly quickly, though, I realised two things: first, that if I did my job as I thought it should be done, and as the Sulzbergers said they wanted me to do it, I would be too polarising internally ever to lead the newsroom; second, that I did not want that job, though no one but my wife believed me when I said that.

It was 2016, a presidential-election year, and I had been gone from the Times for a decade. Although many of my old colleagues had also left in the interim and the Times had moved into a new glass-and-steel tower, I otherwise had little idea how much things had changed. When I looked around the Opinion department, change was not what I perceived. Excellent writers and editors were doing excellent work. But the department’s journalism was consumed with politics and foreign affairs in an era when readers were also fascinated by changes in technology, business, science and culture.

The Opinion department mocked the paper’s claim to value diversity. It did not have a single black editor. The large staff of op-ed editors contained only a couple of women. Although the 11 columnists were individually admirable, only two of them were women and only one was a person of colour. (The Times had not appointed a black columnist until the 1990s, and had only employed two in total.) Not only did they all focus on politics and foreign affairs, but during the 2016 campaign, no columnist shared, in broad terms, the worldview of the ascendant progressives of the Democratic Party, incarnated by Bernie Sanders. And only two were conservative.

This last fact was of particular concern to the elder Sulzberger. He told me the Times needed more conservative voices, and that its own editorial line had become predictably left-wing. “Too many liberals,” read my notes about the Opinion line-up from a meeting I had with him and Mark Thompson, then the chief executive, as I was preparing to rejoin the paper. “Even conservatives are liberals’ idea of a conservative.” The last note I took from that meeting was: “Can’t ignore 150m conservative Americans.”

I was astonished by the fury of my Times colleagues. I found myself facing an angry internal town hall, trying to justify what to me was an obvious journalistic decision

With my Opinion colleagues, I set out to deal with this long list of needs. I restructured the department, changing everybody’s role and, using buyouts, changing people as well. It was too much, too fast; it rocked the department, and my colleagues and I made mistakes amid the turmoil, including one that brought a libel suit from John McCain’s vice-presidential running-mate, Sarah Palin, dismissed twice by a judge and once by a jury but endlessly appealed on procedural grounds. Yet we also did more in four years to diversify the line-up of writers by identity, ideology and expertise than the Times had in the previous century; we published more ambitious projects than Opinion had ever attempted. We won two Pulitzer prizes in four years – as many as the department had in the previous 20.

As I knew from my time at the Atlantic, this kind of structural transformation can be frightening and even infuriating for those understandably proud of things as they are. It is hard on everyone. But experience at the Atlantic also taught me that pursuing new ways of doing journalism in pursuit of venerable institutional principles created enthusiasm for change. I expected that same dynamic to allay concerns at the Times.

In that same statement in 1896, after committing the Times to pursue the news without fear or favour, Ochs promised to “invite intelligent discussion from all shades of opinion”. So adding new voices, some more progressive and others more conservative, and more journalists of diverse identities and backgrounds, fulfilled the paper’s historic purpose. If Opinion published a wider range of views, it would help frame a set of shared arguments that corresponded to, and drew upon, the set of shared facts coming from the newsroom. On the right and left, America’s elites now talk within their tribes, and get angry or contemptuous on those occasions when they happen to overhear the other conclave. If they could be coaxed to agree what they were arguing about, and the rules by which they would argue about it, opinion journalism could serve a foundational need of the democracy by fostering diverse and inclusive debate. Who could be against that?

Out of naivety or arrogance, I was slow to recognise that at the Times, unlike at the Atlantic, these values were no longer universally accepted, let alone esteemed. When I first took the job, I felt some days as if I’d parachuted onto one of those Pacific islands still held by Japanese soldiers who didn’t know that the world beyond the waves had changed. Eventually, it sank in that my snotty joke was actually on me: I was the one ignorantly fighting a battle that was already lost. The old liberal embrace of inclusive debate that reflected the country’s breadth of views had given way to a new intolerance for the opinions of roughly half of American voters. New progressive voices were celebrated within the Times. But in contrast to the Wall Street Journal and the Washington Post, conservative voices – even eloquent anti-Trump conservative voices – were despised, regardless of how many leftists might surround them. (President Trump himself submitted one op-ed during my time, but we could not raise it to our standards – his people would not agree to the edits we asked for.)

About a year after the 2016 election, the Times newsroom published a profile of a man from Ohio who had attended the rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, at which a white nationalist drove his car into a crowd of protesters, killing one. It was a terrifying piece. The man had four cats, listened to National Public Radio, and had registered at Target for a muffin pan before his recent wedding. In exploring his evolution from “vaguely leftist rock musician to ardent libertarian to fascist activist” the article rang an alarm about how “the election of President Donald Trump helped open a space for people like him”.

The profile was in keeping with the Times’s tradition of confronting readers with the confounding reality of the world around them. After the 9/11 attacks, as the bureau chief in Jerusalem, I spent a lot of time in the Gaza Strip interviewing Hamas leaders, recruiters and foot soldiers, trying to understand and describe their murderous ideology. Some readers complained that I was providing a platform for terrorists, but there was never any objection from within the Times. (Nor did it occur to me to complain that by publishing op-eds critical of Hamas the Opinion department was putting my life in danger.) Our role, we knew, was to help readers understand such threats, and this required empathetic – not sympathetic – reporting. This is not an easy distinction but good reporters make it: they learn to understand and communicate the sources and nature of a toxic ideology without justifying it, much less advocating it.

Today’s newsroom turns that moral logic on its head, at least when it comes to fellow Americans. Unlike the views of Hamas, the views of many Americans have come to seem dangerous to engage in the absence of explicit condemnation. Focusing on potential perpetrators – “platforming” them by explaining rather than judging their views – is believed to empower them to do more harm. After the profile of the Ohio man was published, media Twitter lit up with attacks on the article as “normalising” Nazism and white nationalism, and the Times convulsed internally. The Times wound up publishing a cringing editor’s note that hung the writer out to dry and approvingly quoted some of the criticism, including a tweet from a Washington Post opinion editor asking, “Instead of long, glowing profiles of Nazis/White nationalists, why don’t we profile the victims of their ideologies”? The Times did profile the victims of such ideologies; and the very headline of the piece – “A Voice of Hate in America’s Heartland” – undermined the claim that it was “glowing”. But the Times lacked the confidence to defend its own work. (As it happens, being platformed did not do much to increase the power of that Ohio man. He, his wife and his brother lost their jobs and the newly married couple lost the home intended for their muffin pan.)

I felt some days as if I’d parachuted onto one of those Pacific islands still held by Japanese soldiers who didn’t know that the world beyond the waves had changed

The editor’s note paraded the principle of publishing such pieces, saying it was important to “shed more light, not less, on the most extreme corners of American life”. But less light is what the readers got. As a reporter in the newsroom, you’d have to have been an idiot after that explosion to attempt such a profile. Empathetic reporting about Trump supporters became even more rare. It became a cliché among influential left-wing columnists and editors that blinkered political reporters interviewed a few Trump supporters in diners and came away suckered into thinking there was something besides racism that could explain anyone’s support for the man.

I failed to take the hint. As the first anniversary of Trump’s inauguration approached, the editors who compile letters to the Times, part of my department, had put out a request to readers who supported the president to say what they thought of him now. The results had some nuance. “Yes, he is embarrassing,” wrote one reader. “Yes, he picks unnecessary fights. But he also pushed tax reform through, has largely defeated isis in Iraq,” and so forth. After a year spent publishing editorials attacking Trump and his policies, I thought it would be a demonstration of Timesian open-mindedness to give his supporters their say. Also, I thought the letters were interesting, so I turned over the entire editorial page to the Trump letters.

I wasn’t surprised that we got some criticism on Twitter. But I was astonished by the fury of my Times colleagues. I found myself facing an angry internal town hall, trying to justify what to me was an obvious journalistic decision. During the session, one of the newsroom’s journalists demanded to know when I would publish a page of letters from Barack Obama’s supporters. I stammered out some kind of answer. The question just didn’t make sense to me. Pretty much every day we published letters from people who supported Obama and criticised Trump. Didn’t he know that Obama wasn’t president any more? Didn’t he think other Times readers should understand the sources of Trump’s support? Didn’t he also see it was a wonderful thing that some Trump supporters did not just dismiss the Times as fake news, but still believed in it enough to respond thoughtfully to an invitation to share their views?

And if the Times could not bear to publish the views of Americans who supported Trump, why should it be surprised that those voters would not trust it? Two years later, in 2020, Baquet acknowledged that in 2016 the Times had failed to take seriously the idea that Trump could become president partly because it failed to send its reporters out into America to listen to voters and understand “the turmoil in the country”. And, he continued, the Times still did not understand the views of many Americans. “One of the great puzzles of 2016 remains a great puzzle,” he said. “Why did millions and millions of Americans vote for a guy who’s such an unusual candidate?” Speaking four months before we published the Cotton op-ed, he said that to argue that the views of such voters should not appear in the Times was “not journalistic”.

Conservative arguments in the Opinion pages reliably started uproars within the Times. Sometimes I would hear directly from colleagues who had the grace to confront me with their concerns; more often they would take to the company’s Slack channels or Twitter to advertise their distress in front of each other. By contrast, in my four years as Opinion editor, I received just two complaints from newsroom staff about pieces we published from the left. When I was visiting one of the Times’s West Coast bureaus, a reporter pulled me aside to say he worried that a liberal columnist was engaged in ad hominem attacks; a reporter in the Washington bureau wrote to me to object to an op-ed piece questioning the value of protecting free speech for right-wing groups.

This environment of enforced group-think, inside and outside the paper, was hard even on liberal opinion writers. One left-of-centre columnist told me that he was reluctant to appear in the New York office for fear of being accosted by colleagues. (An internal survey shortly after I left the paper found that barely half the staff, within an enterprise ostensibly devoted to telling the truth, agreed “there is a free exchange of views in this company” and “people are not afraid to say what they really think”.) Even columnists with impeccable leftist bona fides recoiled from tackling subjects when their point of view might depart from progressive orthodoxy. I once complimented a long-time, left-leaning Opinion writer over a column criticising Democrats in Congress for doing something stupid. Trying to encourage more such journalism and thus less such stupidity, I remarked that this kind of argument had more influence than yet another Trump-is-a-devil column. “I know,” he replied, ruefully. “But Twitter hates it.”

The bias had become so pervasive, even in the senior editing ranks of the newsroom, as to be unconscious. Trying to be helpful, one of the top newsroom editors urged me to start attaching trigger warnings to pieces by conservatives. It had not occurred to him how this would stigmatise certain colleagues, or what it would say to the world about the Times’s own bias. By their nature, information bubbles are powerfully self-reinforcing, and I think many Times staff have little idea how closed their world has become, or how far they are from fulfilling their compact with readers to show the world “without fear or favour”. And sometimes the bias was explicit: one newsroom editor told me that, because I was publishing more conservatives, he felt he needed to push his own department further to the left.

Even columnists with impeccable leftist bona fides recoiled from tackling subjects when their point of view might depart from progressive orthodoxy

The Times’s failure to honour its own stated principles of openness to a range of views was particularly hard on the handful of conservative writers, some of whom would complain about being flyspecked and abused by colleagues. One day when I relayed a conservative’s concern about double standards to Sulzberger, he lost his patience. He told me to inform the complaining conservative that that’s just how it was: there was a double standard and he should get used to it. A publication that promises its readers to stand apart from politics should not have different standards for different writers based on their politics. But I delivered the message. There are many things I regret about my tenure as editorial-page editor. That is the only act of which I am ashamed.

As I Realised How Different the New Times had become from the old one that trained me, I began to think of myself not as a benighted veteran on a remote island, but as Rip Van Winkle. I had left one newspaper, had a pleasant dream for ten years, and returned to a place I barely recognised. The new New York Times was the product of two shocks – sudden collapse, and then sudden success. The paper almost went bankrupt during the financial crisis, and the ensuing panic provoked a crisis of confidence among its leaders. Digital competitors like the HuffPost were gaining readers and winning plaudits within the media industry as innovative. They were the cool kids; Times folk were ink-stained wrinklies.

In its panic, the Times bought out experienced reporters and editors and began hiring journalists from publications like the HuffPost who were considered “digital natives” because they had never worked in print. This hiring quickly became easier, since most digital publications financed by venture capital turned out to be bad businesses. The advertising that was supposed to fund them flowed instead to the giant social-media companies. The HuffPosts and Buzzfeeds began to decay, and the Times’s subscriptions and staff began to grow.

I have been lucky in my own career to move between local and national and international journalism, newspapers and magazines, opinion and news, and the print and digital realms. I was even luckier in these various roles to have editors with a profound understanding of their particular form and a sense of duty about teaching it. The wipeout of local papers and the desperate transformation of survivors like the Times have left young reporters today with fewer such opportunities.

Though they might have lacked deep or varied reporting backgrounds, some of the Times’s new hires brought skills in video and audio; others were practised at marketing themselves – building their brands, as journalists now put it – in social media. Some were brilliant and fiercely honest, in keeping with the old aspirations of the paper. But, critically, the Times abandoned its practice of acculturation, including those months-long assignments on Metro covering cops and crime or housing. Many new hires who never spent time in the streets went straight into senior writing and editing roles. Meanwhile, the paper began pushing out its print-era salespeople and hiring new ones, and also hiring hundreds of engineers to build its digital infrastructure. All these recruits arrived with their own notions of the purpose of the Times. To me, publishing conservatives helped fulfil the paper’s mission; to them, I think, it betrayed that mission.

Dean Baquet, Former Executive Editor of the New York Times Addressing the Newsroom (Top).

And then, to the shock and horror of the newsroom, Trump won the presidency. In his article for Columbia Journalism Review, Sulzberger cites the Times’s failure to take Trump’s chances seriously as an example of how “prematurely shutting down inquiry and debate” can allow “conventional wisdom to ossify in a way that blinds society.” Many Times staff members – scared, angry – assumed the Times was supposed to help lead the resistance. Anxious for growth, the Times’s marketing team implicitly endorsed that idea, too.

As the number of subscribers ballooned, the marketing department tracked their expectations, and came to a nuanced conclusion. More than 95% of Times subscribers described themselves as Democrats or independents, and a vast majority of them believed the Times was also liberal. A similar majority applauded that bias; it had become “a selling point”, reported one internal marketing memo. Yet at the same time, the marketers concluded, subscribers wanted to believe that the Times was independent.

When you think about it, this contradiction resolves itself easily. It is human nature to want to see your bias confirmed; however, it is also human nature to want to be reassured that your bias is not just a bias, but is endorsed by journalism that is “fair and balanced”, as a certain Murdoch-owned cable-news network used to put it. As that memo argued, even if the Times was seen as politically to the left, it was critical to its brand also to be seen as broadening its readers’ horizons, and that required “a perception of independence”.

Perception is one thing, and actual independence another. Readers could cancel their subscriptions if the Times challenged their worldview by reporting the truth without regard to politics. As a result, the Times’s long-term civic value was coming into conflict with the paper’s short-term shareholder value. As the cable networks have shown, you can build a decent business by appealing to the millions of Americans who comprise one of the partisan tribes of the electorate. The Times has every right to pursue the commercial strategy that makes it the most money. But leaning into a partisan audience creates a powerful dynamic. Nobody warned the new subscribers to the Times that it might disappoint them by reporting truths that conflicted with their expectations. When your product is “independent journalism”, that commercial strategy is tricky, because too much independence might alienate your audience, while too little can lead to charges of hypocrisy that strike at the heart of the brand.

To the horror of the newsroom, Trump won the presidency. Many Times staff members – scared, angry – assumed the Times was supposed to help lead the resistance

It became one of Dean Baquet’s frequent mordant jokes that he missed the old advertising-based business model, because, compared with subscribers, advertisers felt so much less sense of ownership over the journalism. I recall his astonishment, fairly early in the Trump administration, after Times reporters conducted an interview with Trump. Subscribers were angry about the questions the Times had asked. It was as if they’d only be satisfied, Baquet said, if the reporters leaped across the desk and tried to wring the president’s neck. The Times was slow to break it to its readers that there was less to Trump’s ties to Russia than they were hoping, and more to Hunter Biden’s laptop, that Trump might be right that covid came from a Chinese lab, that masks were not always effective against the virus, that shutting down schools for many months was a bad idea.

In my experience, reporters overwhelmingly support Democratic policies and candidates. They are generally also motivated by a desire for a more just world. Neither of those tendencies are new. But there has been a sea change over the past ten years in how journalists think about pursuing justice. The reporters’ creed used to have its foundation in liberalism, in the classic philosophical sense. The exercise of a reporter’s curiosity and empathy, given scope by the constitutional protections of free speech, would equip readers with the best information to form their own judgments. The best ideas and arguments would win out. The journalist’s role was to be a sworn witness; the readers’ role was to be judge and jury. In its idealised form, journalism was lonely, prickly, unpopular work, because it was only through unrelenting scepticism and questioning that society could advance. If everyone the reporter knew thought X, the reporter’s role was to ask: why X?

Illiberal journalists have a different philosophy, and they have their reasons for it. They are more concerned with group rights than individual rights, which they regard as a bulwark for the privileges of white men. They have seen the principle of free speech used to protect right-wing outfits like Project Veritas and Breitbart News and are uneasy with it. They had their suspicions of their fellow citizens’ judgment confirmed by Trump’s election, and do not believe readers can be trusted with potentially dangerous ideas or facts. They are not out to achieve social justice as the knock-on effect of pursuing truth; they want to pursue it head-on. The term “objectivity” to them is code for ignoring the poor and weak and cosying up to power, as journalists often have done.

And they do not just want to be part of the cool crowd. They need to be. To be more valued by their peers and their contacts – and hold sway over their bosses – they need a lot of followers in social media. That means they must be seen to applaud the right sentiments of the right people in social media. The journalist from central casting used to be a loner, contrarian or a misfit. Now journalism is becoming another job for joiners, or, to borrow Twitter’s own parlance, “followers”, a term that mocks the essence of a journalist’s role.

This is a bit of a paradox. The new newsroom ideology seems idealistic, yet it has grown from cynical roots in academia: from the idea that there is no such thing as objective truth; that there is only narrative, and that therefore whoever controls the narrative – whoever gets to tell the version of the story that the public hears – has the whip hand. What matters, in other words, is not truth and ideas in themselves, but the power to determine both in the public mind.

By contrast, the old newsroom ideology seems cynical on its surface. It used to bug me that my editors at the Times assumed every word out of the mouth of any person in power was a lie. And the pursuit of objectivity can seem reptilian, even nihilistic, in its abjuration of a fixed position in moral contests. But the basis of that old newsroom approach was idealistic: the notion that power ultimately lies in truth and ideas, and that the citizens of a pluralistic democracy, not leaders of any sort, must be trusted to judge both.

Our role in Times Opinion, I used to urge my colleagues, was not to tell people what to think, but to help them fulfil their desire to think for themselves. It seems to me that putting the pursuit of truth, rather than of justice, at the top of a publication’s hierarchy of values also better serves not just truth but justice, too: over the long term journalism that is not also sceptical of the advocates of any form of justice and the programmes they put forward, and that does not struggle honestly to understand and explain the sources of resistance, will not assure that those programmes will work, and it also has no legitimate claim to the trust of reasonable people who see the world very differently. Rather than advance understanding and durable change, it provokes backlash.

The impatience within the newsroom with such old ways was intensified by the generational failure of the Times to hire and promote women and non-white people, black people in particular. In the 1990s, and into the early part of this century, when I worked in the high-profile Washington bureau of the Times, usually at most two of the dozens of journalists stationed there were black. Before Baquet became executive editor, the highest-ranked black journalist at the Times had been my old Metro editor, Gerald Boyd. He rose to become managing editor before A.G. Sulzberger’s father pushed him out, along with the executive editor, Howell Raines, when a black reporter named Jayson Blair was discovered to be a fabulist. Boyd was said to have protected Blair, an accusation he denied and attributed to racism.

The accusation against Boyd never made sense to me. In my experience he was even harder on black and brown reporters than he was on us white people. He understood better than anyone what it would take for them to succeed at the Times. “The Times was a place where blacks felt they had to convince their white peers that they were good enough to be there,” he wrote in his heartbreaking memoir, published posthumously. He died in 2006 of lung cancer, three years after he was discarded.

Illiberal journalists are not out to achieve social justice as the knock-on effect of pursuing truth; they want to pursue it head-on. The term “objectivity” to them is code for ignoring the poor and weak and cosying up to power

Pay attention if you are white at the Times and you will hear black editors speak of hiring consultants at their own expense to figure out how to get white staff to respect them. You might hear how a black journalist, passing through the newsroom, was asked by a white colleague whether he was the “telephone guy” sent to fix his extension. I certainly never got asked a question like that. Among the experienced journalists at the Times, black journalists were least likely, I thought, to exhibit fragility and herd behaviour.

As wave after wave of pain and outrage swept through the Times, over a headline that was not damning enough of Trump or someone’s obnoxious tweets, I came to think of the people who were fragile, the ones who were caught up in Slack or Twitter storms, as people who had only recently discovered that they were white and were still getting over the shock. Having concluded they had got ahead by working hard, it has been a revelation to them that their skin colour was not just part of the wallpaper of American life, but a source of power, protection and advancement. They may know a lot about television, or real estate, or how to edit audio files, but their work does not take them into shelters, or police precincts, or the homes of people who see the world very differently. It has never exposed them to live fire. Their idea of violence includes vocabulary.

I share the bewilderment that so many people could back Trump, given the things he says and does, and that makes me want to understand why they do: the breadth and diversity of his support suggests not just racism is at work. Yet these elite, well-meaning Times staff cannot seem to stretch the empathy they are learning to extend to people with a different skin colour to include those, of whatever race, who have different politics.

The digital natives were nevertheless valuable, not only for their skills but also because they were excited for the Times to embrace its future. That made them important allies of the editorial and business leaders as they sought to shift the Times to digital journalism and to replace staff steeped in the ways of print. Partly for that reason, and partly out of fear, the leadership indulged internal attacks on Times journalism, despite pleas from me and others, to them and the company as a whole, that Times folk should treat each other with more respect. My colleagues and I in Opinion came in for a lot of the scorn, but we were not alone. Correspondents in the Washington bureau and political reporters would take a beating, too, when they were seen as committing sins like “false balance” because of the nuance in their stories.

My fellow editorial and commercial leaders were well aware of how the culture of the institution had changed. As delighted as they were by the Times’s digital transformation they were not blind to the ideological change that came with it. They were unhappy with the bullying and group-think; we often discussed such cultural problems in the weekly meetings of the executive committee, composed of the top editorial and business leaders, including the publisher. Inevitably, these bitch sessions would end with someone saying a version of: “Well, at some point we have to tell them this is what we believe in as a newspaper, and if they don’t like it they should work somewhere else.” It took me a couple of years to realise that this moment was never going to come.

Top: Arthur Sulzberger, Former Publisher of the New York Times (left) with his Son A.G. Sulzberger at the Times building in 2017

More than 30 years ago, a young political reporter named Todd Purdum tremulously asked an all-staff meeting what would be done about the “climate of fear” within the newsroom in which reporters felt intimidated by their bosses? The moment immediately entered Times lore. There is a lot not to miss about the days when editors like Boyd could strike terror in young reporters like me and Purdum. But the pendulum has swung so far in the other direction that editors now tremble before their reporters and even their interns. “I miss the old climate of fear,” Baquet used to say with a smile, in another of his barbed jokes.

During the First Meeting of the Times Board of Directors that I attended, in 2016, Baquet and I hosted a joint question-and-answer session. At one point, Baquet, musing about how the Times was changing, observed that one of the newsroom’s cultural critics had become the paper’s best political-opinion columnist. Taking this musing one step further, I then noted that this raised an obvious question: why did the paper still have an Opinion department separate from the newsroom, with its own editor reporting directly to the publisher? If the newsroom was publishing the best opinion journalism at the paper – if it was publishing opinion at all – why did the Times maintain a separate department that falsely claimed to have a monopoly on such journalism?

Everyone laughed. But I meant it, and I wish I’d pursued my point and talked myself out of the job. This contest over control of opinion journalism within the Times was not just a bureaucratic turf battle (though it was that, too). The newsroom’s embrace of opinion journalism has compromised the Times’s independence, misled its readers and fostered a culture of intolerance and conformity.

The Opinion department is a relic of the era when the Times enforced a line between news and opinion journalism. Editors in the newsroom did not touch opinionated copy, lest they be contaminated by it, and opinion journalists and editors kept largely to their own, distant floor within the Times building. Such fastidiousness could seem excessive, but it enforced an ethos that Times reporters owed their readers an unceasing struggle against bias in the news. But by the time I returned as editorial-page editor, more opinion columnists and critics were writing for the newsroom than for Opinion. As at the cable news networks, the boundaries between commentary and news were disappearing, and readers had little reason to trust that Times journalists were resisting rather than indulging their biases.

The publisher called to tell me the company was experiencing its largest sick day in history; people were turning down job offers because of the op-ed, and, he said, some people were quitting

The Times newsroom had added more cultural critics, and, as Baquet noted, they were free to opine about politics. Departments across the Times newsroom had also begun appointing their own “columnists”, without stipulating any rules that might distinguish them from columnists in Opinion. It became a running joke. Every few months, some poor editor in the newsroom or Opinion would be tasked with writing up guidelines that would distinguish the newsroom’s opinion journalists from those of Opinion, and every time they would ultimately throw up their hands.

I remember how shaken A.G. Sulzberger was one day when he was cornered by a cultural critic who had got wind that such guardrails might be put in place. The critic insisted he was an opinion writer, just like anyone in the Opinion department, and he would not be reined in. He wasn’t. (I checked to see if, since I left the Times, it had developed guidelines explaining the difference, if any, between a news columnist and opinion columnist. The paper’s spokeswoman, Danielle Rhoades Ha, did not respond to the question.)

The internet rewards opinionated work and, as news editors felt increasing pressure to generate page views, they began not just hiring more opinion writers but also running their own versions of opinionated essays by outside voices – historically, the province of Opinion’s op-ed department. Yet because the paper continued to honour the letter of its old principles, none of this work could be labelled “opinion” (it still isn’t). After all, it did not come from the Opinion department. And so a newsroom technology columnist might call for, say, unionisation of the Silicon Valley workforce, as one did, or an outside writer might argue in the business section for reparations for slavery, as one did, and to the average reader their work would appear indistinguishable from Times news articles.

By similarly circular logic, the newsroom’s opinion journalism breaks another of the Times’s commitments to its readers. Because the newsroom officially does not do opinion – even though it openly hires and publishes opinion journalists – it feels free to ignore Opinion’s mandate to provide a diversity of views. When I was editorial-page editor, there were a couple of newsroom columnists whose politics were not obvious. But the other newsroom columnists, and the critics, read as passionate progressives.

I urged Baquet several times to add a conservative to the newsroom roster of cultural critics. That would serve the readers by diversifying the Times’s analysis of culture, where the paper’s left-wing bias had become most blatant, and it would show that the newsroom also believed in restoring the Times’s commitment to taking conservatives seriously. He said this was a good idea, but he never acted on it. I couldn’t help trying the idea out on one of the paper’s top cultural editors, too: he told me he did not think Times readers would be interested in that point of view.

As the Times tried to compete for more readers online, homogenous opinion was spreading through the newsroom in other ways. News desks were urging reporters to write in the first person and to use more “voice”, but few newsroom editors had experience in handling that kind of journalism, and no one seemed certain where “voice” stopped and “opinion” began. The Times magazine, meanwhile, became a crusading progressive publication. Baquet liked to say the magazine was Switzerland, by which he meant that it sat between the newsroom and Opinion. But it reported only to the news side. Its work was not labelled as opinion and it was free to omit conservative viewpoints.

This creep of politics into the newsroom’s journalism helped the Times beat back some of its new challengers, at least those on the left. Competitors like Vox and the HuffPost were blending leftish politics with reporting and writing it up conversationally in the first person. Imitating their approach, along with hiring some of their staff, helped the Times repel them. But it came at a cost. The rise of opinion journalism over the past 15 years changed the newsroom’s coverage and its culture. The tiny redoubt of never-Trump conservatives in Opinion is swamped daily not only by the many progressives in that department but their reinforcements among the critics, columnists and magazine writers in the newsroom. They are generally excellent, but their homogeneity means Times readers are being served a very restricted range of views, some of them presented as straight news by a publication that still holds itself out as independent of any politics. And because the critics, newsroom columnists and magazine writers are the newsroom’s most celebrated journalists, they have disproportionate influence over the paper’s culture.

And yet the Times insists to the public that nothing has changed. By saying that it still holds itself to the old standard of strictly separating its news and opinion journalists, the paper leads its readers further into the trap of thinking that what they are reading is independent and impartial – and this misleads them about their country’s centre of political and cultural gravity. “Even though each day’s opinion pieces are typically among our most popular journalism and our columnists are among our most trusted voices, we believe opinion is secondary to our primary mission of reporting and should represent only a portion of a healthy news diet,” Sulzberger wrote in the Columbia Journalism Review. “For that reason, we’ve long kept the Opinion department intentionally small – it represents well under a tenth of our journalistic staff – and ensured that its editorial decision-making is walled off from the newsroom.”

I came to think of those caught up in Slack or Twitter storms as people who had only recently discovered that they were white and were still getting over the shock

When I was editorial-page editor, Sulzberger, who declined to be interviewed on the record for this article, worried a great deal about the breakdown in the boundaries between news and opinion. At one town hall, he was confronted by a staffer upset that we in Opinion had begun doing more original reporting, which was a priority for me. Sulzberger replied he was much less worried about reporting in the Opinion coverage than by opinion in the news report – a fine moment, I thought then and think now, in his leadership. He told me once that he would like to restructure the paper to have one editor oversee all its news reporters, another all its opinion journalists and a third all its service journalists, the ones who supply guidance on buying gizmos or travelling abroad. Each of these editors would report to him. That is the kind of action the Times needs to take now to confront its hypocrisy and begin restoring its independence.

The Times could learn something from the Wall Street Journal, which has kept its journalistic poise. It has maintained a stricter separation between its news and opinion journalism, including its cultural criticism, and that has protected the integrity of its work. After I was chased out of the Times, Journal reporters and other staff attempted a similar assault on their opinion department. Some 280 of them signed a letter listing pieces they found offensive and demanding changes in how their opinion colleagues approached their work. “Their anxieties aren’t our responsibility,” shrugged the Journal’s editorial board in a note to readers after the letter was leaked. “The signers report to the news editors or other parts of the business.” The editorial added, in case anyone missed the point, “We are not the New York Times.” That was the end of it.