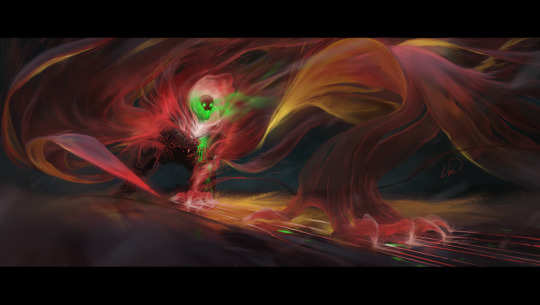

#I may have subconsciously got myself inspired by spawn

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Warning: Long post?

—

Jason did not expect his ghost form to feel…like this.

(Oh, dealing with his body randomly phasing through the ground and smacking his face onto hard concrete was not fun, but Jason dealt with that just like with every other hurdle in his life. By being more stubborn than the problem itself.)

It felt like something… settled into place. That was the best way he could describe it.

He felt as if spite and anger were finally not the only things keeping him awake and running.

He felt calm, almost. Stable, at least. Whatever pent up energy that was stuck in his chest cavity now flowed freely throughout his body, redistributed, instinctually easier to manage.

It's almost like he could breathe a little bit easier.

(After much… ranting that Jason decided to ignore for his own sanity, Danny said that his case ectoplasmic corruption was probably due to the fact that Death, as a concept, doesn’t let go of things easily, time shenanigans notwithstanding.)

(Becoming a half-ghost was seemingly the only working compromise.)

—

Danny once told him that broad strokes of a ghost’s personality could be guessed by looking at their physical appearance.

Despite the cool powers, this was a slight downside. Jason dealing with the filth of the Earth meant that being to hide his emotions and who he is was kind of important. Life saving, even.

He realized later on that his ghost form was way too easy to read.

—

He looked at his arms covered in bandages, and got reminded of the amount of times he had to patch himself up in the last month.

His jacket was ripped in place he knew that would have been sewn together when he was a living breathing human (well, as much as he could be).

He always looked slightly on fire?

(Danny told him it's probably related to his... core?)

(He know he died in an explosion but really?)

And then, there was his… veil? Shroud? Cloak?

It looked really nice.

But on the other hand…

It drooped when he felt under the weather. It flicked and thrashed around when he’s either irritated or barely holding back his urge to headshot someone.

And—

(No Danny, my cloak was not fucking wagging when you brought me fresh ectoplasm last week, you’ll have to get your goddamn eyes checked—)

He'll deny it until the day he dies (a second time).

And then his cloak could sometimes just…grow bigger. He figured that it acted as an extension of his own body, and had a nice add-on of allowing him to sense things he couldn't see. Hell, he could even make a hand out of it (wacking Danny with it - gently - never gets old). Jason had to also admit it looked cool, with the wispy bits and with one of its sides becoming a bright yellow.

(It reminded him a bit of his time as Robin.)

—

Being a ghost had a lotta perks.

Dealing with targets was so much easier when no one could see you. Inflitration was so much simpler when walls became optional. Cameras will glitch out when he's around, he left no traces visible to the naked eye and, combined with his training, to say that it was useful would be an understatement.

But, sometimes, he feels like he’s changing as well the more he transforms. Not drastically, but enough for him to look back and notice.

He usually was someone who prided on being efficient and straight to the point.

But now he’s starting to… have fun.

He started using his claws whenever he could. Don't het him wrong, he still uses his guns plenty, but there was just something deeply satisfying about vaulting over things, scaling a wall or crawling on the ceiling with bare hands.

(Punching people is still the most satisfying by far, though.)

That one time hunting down the Joker wannabes was fun too.

(Danny said he’d get along great with Skulker? Did Jason want to find out? No.)

Fading in and out of invisibility, he picked them off one by one, watching as panic and dread slowly but surely creeped up on the remaining ones.

(After all, he has no respect for those trying to emulate the dead clown.)

—

(Yeah, the Joker was dead.)

(Surprisingly, that has not been a good day.)

—

One of the favorite things he liked to do was rooftop parkour. The… bendability of gravity is… fun, not gonna lie.

(Not flying though. Jason is used to having feet in regular contact with solid ground, thank you very much. No offense, Danny.)

But he gets why ghosts love to fly. When he’s jumping from rooftop to rooftop in Gotham in the at night, watching the city light fly by, cloak spread behind him, it’s as if nothing else matters.

(No Joker, no petty criminals to beat up, no avoiding the Bats so they don’t find out about his existence—)

He can just enjoy, even just for a little bit.

—

(Somehow the Demon Brat and Orphan could sense him. Will keep and eyes on those two, and also the more reasons to avoid them.)

(The real problem was the new Bat in town. Bruce, what the fuck, another one? Again?)

(The yellow one, Signal. No time to check his profile yet, but probably a meta or something.)

(First night out and the guy almost managed to actually fucking see him —looked at him straight in the eyes and all, then did a double take. Jason never phased into the pavement so fast in his entire fucking life.)

(And so far no Bats on his cloak tails yet.)

(He did help the guy incognito, just a couple of times.)

(And he also did steal his escrima sticks for fun, and once the guy went out looking for them, he’d put them right back where they were.)

(Turns out, he discovered later, that being a little shit runs in the ghost community.)

—

(Sometimes he also wonders what happened to Danny before they met.)

(He wasn't a Gothamite, that was obvious. He doesn’t pry, but it doesn’t take a lot to piece two and two together.)

(He just wonders who he has to kill this time.)

—

(Jason could not believe he forgot and underestimated just how fucking persistent every single one of the Bats could be. Of course it had to run in the family.)

He gazed down, thought the agony, at the gaping wound under his right armpit.

(The Bats have been chasing him relentlessly for a while now. He got more injuries than he can count, especially from Bruce.)

(They know. Oh, they know.)

(It didn’t go well.)

(He knows the others are there surrounding him to prevent him from escaping, he knows that Dick is right behind him, but at the moment he couldn’t care less.)

It has been a long time since the last time he got shot.

(It felt like someone set his right side on fire.)

What was flowing out in abundance was a neon, toxic green.

(The Pit Waters, ectoplasm, he didn’t even know that he could fucking bleed in ghost form—)

(Danny—)

He looked back up at Batman, holding a (frankly) ugly gun, white casing and highlights in the same shade of toxic green.

(A gun that Danny warned him about. And everything behind it.)

Jason felt something in him... snap.

(Why did it have to be you, Bruce.)

His mouth opened—

(waitsincewhenhecoulddothatthroughtthe mask—)

(Jason could see the billows of neon green smoke—)

(He couldn’t see Bruce’s expression.)

(Every. Single. Goddamn. Time.)

— and wailed.

---------------------------------------------------

I am genuinely delighted that my last post got that much attention! Thank you so much, to all who liked, rebblogged and commented, it really does mean the most. 💕

This AU may be continued? No guarantees, tho.

For those interested: Part 01

@fandomnerd103 @phoenixdemonqueen @satisfactionbroughtmeback @ascetic-orange @apointlessbox @bathildaburp @fisticuffsatapplebees @aisforanonymity @phandomhyperfixationblog @help-i-need-a-cool-username @hashtagdrivebywrites @did-i-miss-anyone-tagging-is-a-monk's-job-first-time-doing-this-aaaaaaaaaaaaaa

#jason todd#red hood#dc x dp#dp x dc#dc x dp crossover#danny phantom#halfa jason#halfa au#fanart#I may have subconsciously got myself inspired by spawn#as in like i figured it out on a random day halfway through the second painting#and went whooooooops i did it again#It took so long#cauz my perfectionism worked against me#a classic#*cries*#But thanks yall who read the tags#yall delightful#i guess art is a journey but im getting slapped by strong winds in the opposite direction#dc x dp prompt#dc x dp au#the inspiration to write only strikes at ungodly hours of the night i guess

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

New Post has been published on Nehemiah Reset

New Post has been published on https://nehemiahreset.org/christian-worldview-issues/lgbt/george-takeis-extraordinary-trek-the-washington-post/

George Takei's extraordinary trek - The Washington Post

NEW YORK — As a child, he believed the camp to be a magical oasis, where mythical dinosaurs prowled the woods at night. A native of Los Angeles, he marveled at the “flying exotica” of dragonflies, the treasures of rural life and, that first winter, the “pure magic” of snow.

George Takei spent ages 5 to almost 9 imprisoned by the U.S. government in Japanese American internment camps. A relentless optimist, he believed the shameful legacy of incarcerating an estimated 120,000 Americans during World War II would never be forgotten or duplicated.

At 82, Takei came to understand that he may be mistaken on both counts.

Stories fell into the sinkhole of history, given the omission of the camps from many textbooks and the shame felt by former internees, many of whom remained silent about their experiences, even to descendants. Takei takes no refuge in silence.

The “Star Trek” actor has lived long enough to see thousands of immigrant children jailed near the border. On Twitter, to his 2.9 million followers, he wrote, “This nation has a long and tragic history of separating children from their parents, ever since the days of slavery.”

Sitting in his Manhattan pied-à-terre near Carnegie Hall, the activist for gay rights and social justice calls his government’s actions “an endless cycle of inhumanity, cruelty and injustice repeated generation after generation” and says “it’s got to stop.”

Takei was fortunate. He and his two younger siblings were never separated from their parents, who bore the brunt of fear and degradation in the swamps of Arkansas and the high desert of Northern California. They shielded their children, creating a “Life Is Beautiful” experience often filled with wonder. His father told him they were going for “a long vacation in the country.” Their first stop, of all places, was the Santa Anita Racetrack, where the family was assigned to sleep in the stalls. “We get to sleep where the horsies slept! Fun!” he thought.

[Book review: George Takei has talked about internment before, but never quite like this]

Takei had little understanding of his family abandoning their belongings, the government questioning their patriotism and their return to Los Angeles with nothing, starting over on Skid Row. As a teenager, he came to understand the toll.

“The resonance of my childhood in prison is so loud,” says the actor, who still lives in L.A.

The only surviving photograph of Takei while he was in the Rohwer Japanese American Relocation Camp in Rohwer, Ark., in 1942 and 1943. (George Takei)

This summer, Takei is accelerating his mission to make Americans remember. Almost three-quarters of a century after his release, he feels the crush of time: “I have to tell this story before there’s no one left to tell it.”

He has a new graphic memoir, “They Called Us Enemy,” intended to reach all generations but especially the young, by the publisher of the best-selling “March” trilogy by Rep. John Lewis (D-Ga.).

In August, Takei appears in AMC’s 10-episode “The Terror: Infamy,” a horror saga partially set in an internment camp. Four years ago, he starred in the Broadway musical “Allegiance,” inspired by his personal history.

“That experience in the camps gave me my identity,” he says in the apartment he shares with his husband, Brad, which is decorated with Japanese ink drawings and “Star Trek” bric-a-brac: a Starship Enterprise phone, a Sulu action figure in a Bonsai tree.

It’s possible those years in the camps subconsciously nudged Takei toward acting. “To me, the theater was life, its artists, the chroniclers of human history,” he writes in his 1994 autobiography, “To the Stars.” He would star as Hikaru Sulu in a short-lived sci-fi series that would, improbably, spawn more movie and television iterations than furry Tribbles.

In turn, that success created a springboard for social activism. He became “a social media mega-power” — his website’s phrasing, as he has 10 million followers each on two Facebook pages — fueled by a six-member influencer agency, which he calls “Team Takei.” That influence, to a doting and ever-expanding audience, might ensure his experience in the camps matters.

From left, “Star Trek” actors Leonard Nimoy, Takei, DeForest Kelley and James Doohan attend the first showing of the Space Shuttle Enterprise in Palmdale, Calif., on Sept. 17, 1976. (AP)

The eternal frontier

Takei frequently refers to his life as “an American story.” It is also a singular, improbable one.

Who else enjoys continued success through the curious alchemy of “Star Trek,” coming out at age 68 and regular appearances on “The Howard Stern Show”?

“George is a little outrageous, and a little Mr. Rogers. He’s sort of where they meet in the middle,” says filmmaker Jennifer Kroot, who produced the 2014 documentary “To Be Takei.”

After enrolling as an architecture student at the University of California at Berkeley, Takei transferred to UCLA to pursue acting at a time when there was almost no work for Asian Americans except dubbing Japanese monster movies like “Rodan” into English and portraying crass caricatures in the Jerry Lewis vehicles “The Big Mouth” (1967) and “Which Way to the Front?” (1970).

Takei accepted the jobs, the Lewis ones to his everlasting chagrin: “I shouldn’t have done it.” But he learned. Never again.

Fortunately, he landed “Star Trek,” Gene Roddenberry’s utopian vision of space pioneers from varied backgrounds working together in harmony and oddly cropped slacks. Two decades after World War II, it showed an Asian American in a positive role.

Jay Kuo, who co-wrote “Allegiance,” grew up in a household where television was largely forbidden. Not “Star Trek.” Kuo’s Chinese American parents knew “we needed to see ourselves represented. We were invisible. George was the only Asian sex symbol. That shirtless sword scene was groundbreaking,” he says of the scene in which Sulu believes he’s an 18th-century swashbuckler after the crew is infected by a virus.

Mr. Spock (Nimoy), Pavel Chekov (Walter Koenig), Capt. James T. Kirk (William Shatner), Lt. Uhura (Nichelle Nichols), Hikaru Sulu (Takei) and Montgomery “Scotty” Scott (Doohan) stand on the bridge of the Starship Enterprise in the 1968 Season 3 “Star Trek” premiere. (CBS/Getty Images)

The Starship Enterprise was tasked with a five-year mission. Five? The original “Star Trek,” the mother ship of Trekiana, didn’t make it past three, running for just 79 episodes. The final show aired a half-century ago this year.

Takei felt blessed to land the role of the master helmsman. When the show was canceled — “I knew it would be. Good shows were always getting canceled” — Takei was despondent that he would never work again.

Hah! Space became the eternal frontier: six movies with the original cast, an animated series.

[Alyssa Milano’s improbable journey from child star to A-list activist]

Those early TV contracts didn’t favor actors. Takei’s residuals stopped after the 10th rerun. Which happened, Takei says, “about 10,000 reruns ago.”

Fortunately, what the network taketh away, the Trekkies giveth.

Takei jumped on the convention train, across the United States, Canada, Britain, Germany and Japan, signing autographs and posing for photo ops for up to eight hours, his lustrous baritone growing hoarse.

“Star Trek has been enormously bountiful to us,” Takei says. “We had no idea that this phenomenon of Star Trek conventions would follow.”

Now, Takei is one of only four original cast members still alive, along with William Shatner (Capt. James T. Kirk), Nichelle Nichols (communications officer Lt. Uhura) and Walter Koenig (navigator Pavel Chekov).

Takei as Nobuhiro Yamato in AMC’s anthology series “The Terror: Infamy,” set within a World War II-era Japanese American internment camp. (Ed Araquel/AMC)

His professional life flourished, riding the wave of nostalgia and outsize fandom. His personal life, particularly for someone who has always been political and outspoken, was more complicated. Friends and associates long knew Takei was gay. He met Brad Altman, then a journalist, through a gay running club. They started dating in 1987. Brad took George’s last name in 2011.

Takei worried that coming out publicly would deep-six his acting career. So he waited and waited, an eternity, three and a half decades.

“The government imprisoned me for four years for my race. I imprisoned myself about my sexuality for decades,” Kuo recalls Takei telling him. “You can’t imagine what kind of sentry towers you can build around your heart.”

Takei came out in 2005 as a statement, after Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger vetoed a bill legalizing same-sex marriage in California. Quickly, he moved from the closet to the front of the pride parade.

“I was prepared that I wasn’t going to have an acting career,” he says.

Uh, no.

“The opposite happened, and I was more in demand,” Takei says, almost in song. “They love gay George Takei!

It was as though gay was an honorific — and Gay George Takei was a reboot. Gay + “Star Trek” — the latter listing toward camp with its community theater props, too-tight tops and Shatner’s Hamlet-like readings — was a fitting combination.

Takei was hired as much for his droll persona — his catch phrase, “Oh Myyy!” — as his talent. Work was constant: He had appearances on the sitcoms “The Big Bang Theory” and “Will and Grace,” and in Archie Comics (as hero to gay character Kevin Keller), plus that surprising gig on Stern’s show.

Takei and Brad Altman after their wedding on June 17, 2008, in West Hollywood, Calif. The couple started dating in 1987, and Brad took Takei’s last name in 2011. (Valerie Macon/AFP/Getty Images)

“That was a strategy after I came out,” he says of Stern. “We had reached decent, fair-minded people, the LGBT audience. Howard had a huge national audience.”

On Stern’s show, hired technically as “the official announcer” but also as a routinely pranked foil, Takei surprised listeners by inverting his elegant persona — a man who rarely swears or raises his voice — by being as raunchy as the regular crew.

Takei revealed more about his sex life than perhaps anyone anticipated. Mentions of Brad became a constant. Takei’s once-closeted life was broadcast by the master of all media all over Sirius XM.

In 2017, former model Scott R. Brunton alleged that Takei drugged and sexually assaulted him in 1981. No charges were ever filed. Takei denies the incident, which was never substantiated. The actor says, “It’s a fabrication of somebody who wanted to have a story to regale people with.”

Takei moved past it. “It was a very upsetting experience, but it’s never come up again.”

His optimism buoyed him. And he had important causes to serve.

Takei came out in 2005, after Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger vetoed a bill legalizing same-sex marriage in California. “I was prepared that I wasn’t going to have an acting career,” he says. “The opposite happened, and I was more in demand.” (Jesse Dittmar for The Washington Post)

A witness to change

The first time I met George and Brad, at a party in Los Angeles last year, they were bickering.

When we meet in Manhattan, they bicker again over lunch, over the smallest details. Brad worries about almost everything. George does not. It was somewhat refreshing. A cult icon and his spouse being themselves in front of a reporter. Takei’s openness contributes to the continuing embrace by fans five decades after “Star Trek” was canceled and why he’s a natural for Stern. He presents authentically as himself, a man who extols life’s fortunes. Why isn’t he angry with the country that imprisoned his family?

“Because it would be another barbed-wire fence around my heart,” he says.

The Civil Liberties Act of 1988 formally apologized to former Japanese American internees. Takei received a reparation check for $20,000. He donated it to the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles, which he helped found and for which he serves as a trustee.

Takei, far right, with his sister Nancy Reiko Takei, brother Henry Takei, mother Fumiko Emily Takei and father Takekuma Norman Takei, around 1947 to 1948. (George Takei)

Takei has witnessed his country change, often for the better. “When I was growing up, I couldn’t marry a white woman” he has said, due to anti-miscegenation laws. “And now I’m married to a white dude!”

In 2012, when he was on “The Celebrity Apprentice,” he invited host Donald Trump to lunch at “any of Trump’s properties” — smart move — with the intention of discussing marriage equality. Trump accepted the offer. Takei recalls that Trump told him “he believed in traditional marriage between a man and a woman. This from a man who has been married three times!”

Takei was in New York recently for Pride Month, attending the Stonewall anniversary concert and City Hall ceremony. The events are as vital to his identity as acting.

“I was active in almost every other social justice cause as well as political candidates,” he says. “But I was silent about the issue that was most personal to me, most organic to who I am, because I wanted my career.”

Time was generous. He began life in internment camps and came out in his late 60s. At 82, he’s flourishing in a field that had little use for him when he started.

Takei’s graphic novel “They Called Us Enemy” recounts his experience as a child in Japanese American internment camps during World War II.

The actor says he wants to ensure all generations know the story of what happened to his family. (Top Shelf Productions)

LEFT: Takei’s graphic novel “They Called Us Enemy” recounts his experience as a child in Japanese American internment camps during World War II. RIGHT: The actor says he wants to ensure all generations know the story of what happened to his family. (Top Shelf Productions)

But time can punish memory. Takei wants to ensure we know the story of what happened to his family, in his country.

The worst day of internment was the first one, he recalls. Soldiers marched up the driveway with bayonets on their rifles, pounded on the door and took the family away to who knew where and for how long. Says Takei, “It was a terrifying morning.”

Bayonets and a 5-year-old boy. It is, as Takei says, an American story — a frightening and lamentable one.

All we can do is learn.

At 82, Takei is thriving in an industry that once had little use for him. His graphic novel “They Called Us Enemy” was released this month, and AMC’s “The Terror: Infamy” premieres in August. (Jesse Dittmar for The Washington Post)

Story by Karen Heller. Portraits by Jesse Dittmar. Photo editing by Mark Gail. Video by Erin Patrick O’Connor. Copy editing by Whitney Juckno. Design by Eddie Alvarez.

Source link

0 notes

Text

Notes for the Leader — I

“Today I must bring the notebook,” I tell Min, by which I mean the Leader is visiting the base. Min understands the allusion. He chuckles and gives me a little headshake to show he regrets the news on my behalf.

“What are you going to write in it today?”

“Oh, you know, the usual,” I say. “Back alley sewage. ‘Our crusade will end in a triumph to be celebrated for the ages.’ ‘Our people get the mightiest of erections.’ ‘When we pass wind, we pass the wind of 100 stallions.’”

Min looks at me with a look of engineered disbelief. He’s heard this before, but he still plays his part. “Don’t you ever worry he’ll see?”

I put out my cigarette and swig the last of my beer. I wait until the waitress has cleared my glass.

“No, he never looks. And if he did, I’m not certain he’d be able to decipher it. My handwriting is atrocious.” I wink and put my cap on my knee, readying to get up.

“Well, if Sang and Shin pay you a visit one night,” he says, referring to our loving nickname for the secret police, “I expect you to work extra hard in Fun Camp, the treacherous enemy of the people that you are.”

Min throws some money on the table and we walk out the bar onto a chilly but sun-laden sidewalk.

“You need to have the right look,” I tell Min as we walk together to the Ministry.

“What do you mean?”

“Well, it takes years of practice, young one, but you learn the tricks. A sincere, earnestness whenever he walks past you; an inquisitive, but never befuddled look when he’s ‘explaining’; a stiff erectness,” I say. “But the most important thing is the laugh.”

“What do you mean?” Min asks, squinting up at me with his hand blocking the sun.

“He likes to think he’s funny, so you have to learn to laugh — really genuinely laugh — when he tries to crack a joke. The thing is — the jokes aren’t funny and his timing is so bad half the time you aren’t sure if he’s even trying to joke. Once an Admiral laughed at something the Leader had said, thinking it was a joke. He was wrong.”

“What happened to the Admiral?”

“You mean Private,” I say, giving Min a little elbow to his side. “I’m kidding,” I continue, wiping my smirk, “He went stark raving mad and drowned in a river one night. No one has seen him since.” I stop in the middle of the sidewalk and face Min, a look a total earnest on my face. “It’s true. He did. They told us.” Min shakes his head smiling and lights up another cigarette.

“But it’s not so much the authenticity of the laugh — he probably knows our laughs are bullshit. And it’s not about making sure you don’t laugh at something he doesn’t intend as a joke. It’s about getting in a mode where you don’t even have to think about it. I mean, for sanity’s sake, the mind needs to wander when you are listening to such tripe.” A senior officer passes by and we pause. I give a strong salute, my head facing straight ahead but my eyes following him until he’s well down the sidewalk.

“So, your mind must be in two places at one time,” I say as we resume walking. “It must be focused on a sunny beach, or a beautiful woman in bed with you, but it also must have a toehold in reality. You don’t want to miss a joke. But if you’ve been around him enough it becomes automatic, like a goose flying south for winter. You subconsciously learn his cadence to the point where you can start anticipating and you can laugh at the correct time without ever really having heard what he said.”

“I don’t think geese fly south for the winter.”

“It’s true. They told us they do. And can you blame them?”

“Has he ever said something that was actually funny?” Min asks, as we turn the corner and stop at the concrete plaza in front of the Ministry.

“No, he’s never said anything funny. But he’s done something funny, not intentionally of course.” I start to smile thinking back on it. Min inquires.

“Well,” I say, “there was this time about a year ago he was wearing a hat and he started to bend over…” Min looks over my shoulder and I stop my recounting to turn around.

Min’s commanding officer, of a lower rank than myself, slithers up and gives me a salute. He’s an empty vessel of a man. I feel bad that Min must report to him.

“Sir, excuse me for interrupting, but if you are no longer needing to speak with the Lieutenant, I would very much like to have his services,” he says speedily.

I look at Min and give a little grin, pretending to size him up from head to toe. “This one? The solider we created out of the balled up tissue paper lying about the floor of some southern whorehouse? He’s no longer any good to me, Captain. Starting to spoil. The smell is incredible. By all means, take him.” I feel bad that I really have no legitimate excuse for keeping Min out of the Captain’s clutches.

“Thank you, sir,” says the Captain. Sternly, he says to Min, “Follow me.”

Min shakes my hand. “I’ll fill you in on the details of the triumphal actions later,” I say and pat him on the back as he leaves. He looks back and tips his cap at me.

I do like Min, although I’m a bad influence on him. We are from the same village. I’m 10 years older and went through the elite command school while he went the normal grunt route. We met at a military exercise one summer where I was his commanding officer. Being from the same village, we knew the same people, the same card games, we drank the same liquor, in the same copious amounts. Min’s a fatalist, like me, and he’s got a good sense of humor, unlike most in this regime.

I’ve taken Min under my wing the past few years while we’ve both been stationed in the Capitol. He’s got a wife and a young child, and I often feel bad for being as indignant as I am around him. I should be more careful, I say to myself, but I suppose it’s therapeutic, talking to him the way I do. I am selfish, but the relationship is reciprocal. Min likes being riled up, and I’m happy to oblige him, although I think these days the shock has certainly worn off. It’s just become what we do.

A pile of papers waits at my desk. “Applications,” my secretary, a Private, tells me. Every year we receive hundreds of applications for entry into the Strategic Nuclear Defense Unit, which — as second in second — I’m charged with reviewing.

With our mighty nuclear weapons, presciently developed and expertly managed by the Dear Leader for the protection of the Fatherland, we will continue to set the world on a new path while crushing the deleterious elements spawned by the capitalistic foreign demons, who — we all know — are running scared and sulking at their impending demise, brought on hand by the goodness and superiority of the Leader.

They all sound like this. In fact, some years ago I ran into someone at a bar who claimed all of these are written by the same guy in the backroom of some shoe shop. Everyone just pays him. I often find myself scrutinizing various letters to see if I can spot similarities in the handwriting.

I shut the door of my office, but my secretary soon knocks and comes in.

“Please do not forget sir that you are expected at the visit with the Leader at 1 pm sharp. It’s now 12:15. Do you have your notebook?”

I lean back in my chair, pull the notebook out of my jacket pocket and wave it for her.

“Pen?”

I hold up my pen.

“Does it work?”

I stare at her sarcastically and start to scribble on some applications. The pen is out of ink. I look up to find her with two pens in her outstretched hand.

“One is red, one is blue. I understand that some senior commanders use red for strategic and technical advice, while blue is reserved for inspirational and doctrinal quotes.”

“Thank you, Sun. I will use both exactly in the manner you have prescribed. But what if a quote is both technical and inspirational at the same time?” I say, pocketing the pens.

She ignores the question. “Sir, I beg your forgiveness, but may I suggest brushing your teeth or using some mouth wash before the visit with the Leader? I couldn’t help but notice some alcohol on your breath.”

“Does the Leader not like that?” I ask, trying to act sincere.

“My uncle, the Sargent in the army, he’s heard that such conduct could result in some necessary refresher courses.” By this, Sun means reconditioning at a labor camp.

I lie. “I will brush my teeth, Sun.”

Sun smiles. “Sun,” I say, “am I a good man or bad man?”

“You should know the answer if you have to ask,” she replies.

I turn to look out the window and see white and black shop fronts blazing by in tones of gray. Our driver is speeding us through the Capitol at full speed, ignoring all traffic signals. Our haste is unnecessary but it’s for the best. I’m joined by General Nann, a man with the personality of a cracker and the warmth of a cinder blocker whose nostrils are permanently flared, small black hairs poking out of them like porcupine quills. He’s my superior so I am forced to play a part.

“General Nann, any news with our glorious Navy?”

“Any news I have could not be shared with a Colonel,” he says coldly, staring out his window.

“I am sure we are enjoying many triumphs and making great progress under your leadership,” I reply. We sit in silence.

The car flies like a rocket ship out of the capitol and onto the open highway, zipping past billboards of the Leader and ramshackle houses. At a tiny village on the outskirts of the Capitol a dozen young children run up to our car, some with shoes and some without. They clap and hand us handmade silk flowers. Their elation is genuine, though I see the younger ones seem a bit confused. Our driver, a young man in a cheap black suit, hands them some money and we speed off, nearly hitting an old woman pushing a cart.

As we head out into the open fields, I see peasants with windswept faces. They look up at us like we are an alien race that has lorded over them for a long while. I give them a little wave from the window.

“Do you have some connection to these people?” asks Nann.

“No, but I am from a farming family myself.”

“Are you parents still alive?”

“No, my mother died of an illness years ago. My father drowned crossing a river.”

“Why was he crossing a river?” asks Nann. Nann’s family has been in the Capitol for generations. He’s long lost any connection to rural life.

“He needed to get his herd across. A small calf was struggling so he went back to help it and was swept away. I was in military school at the time and got word of it only three months later so I wasn’t able to attend to his burial. Amazingly, two days after he died the calf was found on the riverbank eating grass. It had survived.” I pause to let Nann say something, but he keeps quiet.

“It was given to my cousin who still lives in the village. He wrote me and told me he would tend to it and that I may have it whenever I like. I wrote him back and told him he should sell the animal and buy a well with the proceeds. I heard a couple years ago he didn’t pay heed to my advice. Instead he lost the animal in a card game.”

Nann looks annoyed. “To die for a calf,” he says, chuckling and raising his chin.

I’d like to hit him in the face; he has no idea, the value of a calf to rural folk. Of course, I do not tell him this. Besides, the story is a lie — some of it at least.

“How did you get chosen then, to go to the school for elites?”

Nann knows exactly why I was chosen — everyone does. He just wants me to have to say it.

“I was fortunate — hard work and pleasing the right people, sir.”

Nann laughs. “You mean knowing the right people, don’t you? Tell me, doesn’t the school require a literacy test for entry? As a farmer’s son, how the hell did you pass that?”

I am about to answer but Nann puts a finger up, telling me to halt while he grabs for the vibrating cell phone in his pocket.

“Yes?”

“There should be.”

“Driving to visit the Leader.”

“Some colonel.”

Nann looks at me and shifts his body in the direction of his window.

“Well, set him loose.”

“I don’t know — out in the alleyway. It doesn’t matter.”

Nann laughs.

“Yes, tonight. After 10pm.”

“Is that good or bad?”

“Okay, I need to go.”

“Yes, you too.”

“Sir, I was literate by the time I came to the school. My mother taught me how to read and write,” I say right as Nann has finished putting his phone back in his pocket.

He looks over at me, almost in disbelief that I’ve decided to continue the conversation. “And how did a peasant woman from the fields know how to read and write?” he asks, wide-eyed and staring at my feet.

“She owes it all to our great country and the most Venerable Grandfather,” I say, referring to the Leader’s grandfather. “Our village was graced with a contingent of learned revolutionaries from the Capitol. This was maybe, oh, 35 years ago,” I say, itching my forehead and looking out the window to see the Xan Xi Nuclear Base emerging from the horizon.

“I do not recall such a program. My father was closely connected to rural programs in those years, and he never mentioned any rural literacy training. Are you sure she wasn’t educated by western infiltrators?” Nann sneers.

The truth is, my mother learned to read and write from my father. I would never tell Nann that because I would never tell Nann how my father learned to read and write.

“Yes, sir, very sure,” I answer.

Out of the corner of my eye I see Nann patting his breast pocket. He reaches in and pulls out nothing, looking crestfallen.

“I have forgotten my notebook,” he says gravely, looking me in the eyes for the first time. His face shows like a five year old child who’s about to whipped by his father for the first time.

“That is most unfortunate, sir. Are you sure it’s not in your briefcase?” I ask.

Nann rummages in his brief case, over and over, even tipping its contents out in the space between us. He checks his breast pocket, his back pockets, his breast pocket again. Meanwhile, our car pulls into the base’s parking lot and I see our driver peer into his rear view mirror, his eyes widening as he does so.

“The leader’s motorcade is right behind us,” the driver says, surprised. “He is early today! I will let you hop out so you can get in the greeting line.” The driver hits the accelerator and bolts us to the base’s front entrance area before he slams on the brakes, sending us lurching forward.

“Please, sirs, please get out as soon as you can. I will be sent to re-education if I hold up the Leader’s motorcade for even a second,” our driver says, in the most obsequiously urgent tone imaginable.

I jump out of the car, and pull General Nann out with me. In two parallel lines in front of the base’s main entrance are dozens of esteemed officers, most of them generals, readying themselves for the Leader to emerge from his limousine and walk between them, shaking hands and laughing and giving salutes. All the men are dressed in their finest dress uniforms. Nann and I are the missing pieces of the greeting line.

I hurry forth to one of the lines, seeing our car speed off and the Leader’s limousine about to park in front of the greeting line. Just then, I feel a pull on my back pockets. Nann pulls me in close.

“Give me your fucking notebook,” he grunts.

“Sir, I cannot do that.”

“You can and you fucking will!” says Nann. “I am your ranking officer and I will see that you are put to death if you don’t give me your notebook.”

I look over and see the Leader’s right-hand man emerge from the passenger seat of the limosine and walk over to the back of the limo to let the Leader out. At this moment, the breath comes out of me and I nearly hit the ground. Nann’s fist is mighty, for an old man. Bent over holding my stomach, he reaches over my back and pulls the notebook from my back pocket.

The Leader spews from the limousine and a round of applause erupts. Notebook-less, I run to a spot in one of the lines, squeezing myself between two generals who nearly refuse to budge for me. I see Nann already in place in the other line, beaming and clapping with my notebook in hand. He doesn’t betray a hint of having mugged me just seconds ago. A perniciously adroit bastard, I think to myself.

The Leader is in all black today, but he radiates the energy of the sun. I have a difficult time looking directly at him (I always do), but I notice he has put on some weight since I lost saw him. Everything else about him, however, remains the same — the smile, the boyish face, the penguinish walk and the made up award he always has pinned on his jacket. He walks down the tunnel of officers, like a Roman general celebrating his triumph, ping ponging from line to line in order to shake hands of a few select generals and receive compliments.

I stare at Nann in the other line. I know he can sense I’m looking at him as he keeps his gaze transfixed on the Leader. The Leader zags to an Army General a few people to my left who gives a gentle bow and tells the Leader he’s most honored by his presence. I realize I’ve subconsciously started to clap very hard and I’m smiling so hard my cheeks hurt. Fortunately, within seconds, the Leader has made his way down the line and I ease up.

Once the Leader enters the base doors, the two lines of generals and other officers collapse into an unorganized herd, some groveling to get close to the front and others, like myself, reclining to the back of the scrum. As soon as we all start to walk into the base the notebooks start to come out and the pens start to click. What the hell am I going to do without a notebook, I ask myself.

I look ahead and see Nann with my notebook. I’ve been so distracted wondering what I’m going to do without it that I’ve forgotten that he has full access to my scribblings. If he reads them, he will see them as treason. At best, I will be labeled an idle and irreverent bourgeoisie pig, at worst, a full-out counter-revolutionary and enemy to the people. I will be put to death. Those stupid, sarcastic scribblings, I think to myself.

In only a minute we’ll all be lined up again next to the Leader, expected to devote our entire attentions to him. There’s no way Nann will be able to read my notebooks under such conditions, I think. But then I see him open up the notebook and begin to flip through the pages in slow succession as we make our way down the corridor. I curse him under my breath, finding myself for half a second more infuriated that he has the audacity to invade my private writings than scared with what he will see.

He keeps flipping as we make our way down a large corridor toward the missile display area, a ponderous mass of high-ranking cattle being led to a pen. I keep my eyes on Nann’s back. At one point, he looks over his shoulder, perhaps trying to find me. He doesn’t, I’m off to the other side.

I begin to feel like I’m in my own funeral procession as we make the long, slow march. Or perhaps I am on the great river between the worlds, my body gently being carried down the eternal current. Instead of a gentle trickle of water, however, the only noise I can hear is the hard clopping of two dozen standard-issued military dress boots. My impending transition from the earth is thus made all the more depressing.

I look down and see I am clutching my wallet. Without thinking, I must have pulled it out of my back pocket. It seems that my subconscious mind may still be in survival mode. I can use the wallet as a stand in. Flip it open and pretend it’s a leather bound notebook. It’s a dreadful plan.

We all file into the missile display area, a cavernous room with skylights and a pristine concrete floor. Enormous banners featuring the beaming faces of the Leader and his father and grandfather hang down from the ceiling. Every type of missile in our nuclear arsenal is on display like a trophy, neatly buffed and glimmering. The new missile, the one I’ve been working on for years with a cadre of officers — is the centerpiece of the room. A long red carpet juts out from underneath it like a frog’s tongue, inviting the Leader to step on and walk toward it, which he does. He approaches the missile at a quick pace, putting both hands on it and then his ear, like he’s listening to a seashell. He rubs his fingers up and down the shaft and gets eye level with it. I half expect him to start kicking it like he would the wheels of a new car.

The Leader starts to walk around the missile, as we form a semi-circle around him. I try to keep a step behind the others, attempting to conceal my hands and my wallet as much as possible.

“This is a mighty missile!” the Leader exclaims, proceeding with his slow walk around the missile. Everyone writes this in their notebooks. I pretend to do so as well.

The Leader continues on. He’s in a fiery mood today, more so than usual. “There is an ancient proverb my grandfather told me. Once there was a snake and a fox. The snake told the fox that he should be careful, for the fox stood on land belonging to the snake. The fox told the snake that he should be careful since he was standing on the fox’s land. While they were having this discussion, a mighty ox came and sat down on both the snake and the fox. I will call this missile, the Ox!”

“Are you insane?” a voice whispers into my ear. It is an air force general, one whom I’ve never really spoken to before. He glances down at my flipped open wallet and back at me, a look of total disbelief in his face. Before I can even react, the general fixes his gaze back on the Leader and laughs at a joke. I laugh as well.

“Yes, my friends! What good is a shield without a sword? The first men invented swords, then shields, not the other way around. A shield only buys you a little bit of time, a sword buys you a lifetime!” continues the Leader.

At this moment, I look straight across the room and find Nann staring at me. His eyes look like two river rocks — pallid, opaque and dead. His mouth is taut and menacing, like a piranha. As he stares at me with those pale eyes, I see a slow, almost imperceptible turn of his head from side to side.

The Leader departs from the missile and begins to walk along the inside of the semi-circle, looking closely into the face of each officer and moving towards me like a storm cloud. Those he passes keep one eye on him and one on their notebook, writing furiously.

“We will build several hundred of these. We will ship them to all nations hostile to the foreign devils. We will place these in submarines and in satellites. And one day, one day we shall use them. My father said that a sword rusts and turns hollow if it is never used. So too with our missiles. They must be used before they blow away like sand.”

The Leader is halfway through the semi-circle, five men away from me.

“We will be like the river that chose to cut directly through the mountain, rather than around it. We will…” Three men away.

“…and they will all kowtow to me and denounce their capitalist…”

The Leader stops midsentence, right in front of me, the closest I’ve ever been to him. I keep my eyes fixed at the neck, noticing a large mole. I sense when he begins glancing at my wallet, struggling to make sense of what he sees. He then peers straight at me, his look registering not as a visual but as a sound inside my head — a menagerie of circus animals jumping on a drum. He begins to open his mouth to say something when a security officer runs swiftly to him and begins to whisper in his ear. The Leader listens, keeping his eyes set on me, studying my features. After a minute or so, the Leader nods and turns around.

He walks at a brisk pace straight up to Nann, his hand outstretched like a teacher asking a pupil to hand over a frog they’ve snuck into class. Nann looks surprised but instantly hands the Leader my notebook. He opens it and begins reviewing the pages. The generals and other officers in the semi-circle all stand erect. Outwardly they look like stones, but inside their minds must be frantic with questions.

“Do you think you are going to die? Are you shitting yourself at this point?” asks Min. We are in my living room having some sweet white wine, our ties loosened and our shoes kicked off.

“Yes, most definitely I am, my friend.” I answer.

“What happened then?”

“Two security officers position themselves behind Nann. I look at Nann and sense he must’ve heard them come up from behind. At that moment, his expression changed. It went from that cold, dead fish look to real terror.”

“Did he try explaining that it wasn’t his notebook?”

“No, he remained silent. I believe he was at a loss for words, the bastard. He did look at me though. It’s funny that sometimes we humans can give off two looks at the same time. Nann’s was a mix of both shock and utter hatred, towards me of course. After a minute or so, the Leader very slowly closed the notebook and handed it to his head security person. He said something — I couldn’t hear what — and within seconds Nann was being carted away into the abyss.”

“Do you know what caused the Leader to approach him in the first place?”

“While reading my scribblings in the corridor, someone must’ve looked over Nann’s shoulder and read some of them as well. Thinking the notebook was Nann’s all along, the person must’ve reported him to the security detail.”

“Does anyone know where he is now?” asks Min.

“No one I know has a clue. He’s likely dead, though he could be in prison.”

“And if he’s in prison and tells them that it was really your notebook, what are you going to do?”

I lean back in the chair and take a deep draw from my cigarette. “I don’t know, Min. I guess I will know when that time comes. To be honest, this possibility haunts me. I feel like I’m swimming in a black ocean and there’s sharks somewhere below. Someday those sharks will take off my leg. That’s not the worst part though. The worst part is not knowing when it will happen.”

I make a conscious choice to continue talking, feeling like grandfather rambling to his grandchild. I’m sure this irritates Min, but I proceed.

“As I’ve grown older, I’ve lost confidence and I’ve grown more anxious. You often hear that the young are full of self-confidence and bluster. That’s true. But no one ever talks about losing confidence. If everyone says the young are so confident, and no one says the old are full of confidence, then by definition we lose confidence as we age. Maybe the confidence is supposed to turn into wisdom and self-assuredness, if that’s at all different from confidence — I don’t know if it is. But I don’t have that. I have self-doubt; I have this burgeoning anxiety, not just about the big things, but about the small things too. I see more errors in my ways; I second guess myself often. A task that use to be so easy now leaves me paralyzed with conflicting thoughts and worries about what might happen. I don’t think I display this outwardly — I’m alright at deception — but it’s there, inside me. When I was younger, I’d just do anything asked and I’d do it quickly and forthrightly. Maybe I’d do a crappy job, but I had that confidence and confidence goes a long way in the eyes of others. Confidence can shine crap into gold. But I’ve lost that ability.”

I pause and look over at Min. He gives a smile and rests his head back.

Notes for the Leader — I was originally published in Fiction Hub on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Discover more awesome fiction at https://medium.com/fictionhub

0 notes

Text

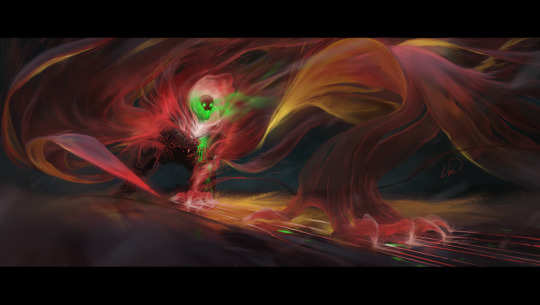

Still freaking cool

Warning: Long post?

—

Jason did not expect his ghost form to feel…like this.

(Oh, dealing with his body randomly phasing through the ground and smacking his face onto hard concrete was not fun, but Jason dealt with that just like with every other hurdle in his life. By being more stubborn than the problem itself.)

It felt like something… settled into place. That was the best way he could describe it.

He felt as if spite and anger were finally not the only things keeping him awake and running.

He felt calm, almost. Stable, at least. Whatever pent up energy that was stuck in his chest cavity now flowed freely throughout his body, redistributed, instinctually easier to manage.

It's almost like he could breathe a little bit easier.

(After much… ranting that Jason decided to ignore for his own sanity, Danny said that his case ectoplasmic corruption was probably due to the fact that Death, as a concept, doesn’t let go of things easily, time shenanigans notwithstanding.)

(Becoming a half-ghost was seemingly the only working compromise.)

—

Danny once told him that broad strokes of a ghost’s personality could be guessed by looking at their physical appearance.

Despite the cool powers, this was a slight downside. Jason dealing with the filth of the Earth meant that being to hide his emotions and who he is was kind of important. Life saving, even.

He realized later on that his ghost form was way too easy to read.

—

He looked at his arms covered in bandages, and got reminded of the amount of times he had to patch himself up in the last month.

His jacket was ripped in place he knew that would have been sewn together when he was a living breathing human (well, as much as he could be).

He always looked slightly on fire?

(Danny told him it's probably related to his... core?)

(He know he died in an explosion but really?)

And then, there was his… veil? Shroud? Cloak?

It looked really nice.

But on the other hand…

It drooped when he felt under the weather. It flicked and thrashed around when he’s either irritated or barely holding back his urge to headshot someone.

And—

(No Danny, my cloak was not fucking wagging when you brought me fresh ectoplasm last week, you’ll have to get your goddamn eyes checked—)

He'll deny it until the day he dies (a second time).

And then his cloak could sometimes just…grow bigger. He figured that it acted as an extension of his own body, and had a nice add-on of allowing him to sense things he couldn't see. Hell, he could even make a hand out of it (wacking Danny with it - gently - never gets old). Jason had to also admit it looked cool, with the wispy bits and with one of its sides becoming a bright yellow.

(It reminded him a bit of his time as Robin.)

—

Being a ghost had a lotta perks.

Dealing with targets was so much easier when no one could see you. Inflitration was so much simpler when walls became optional. Cameras will glitch out when he's around, he left no traces visible to the naked eye and, combined with his training, to say that it was useful would be an understatement.

But, sometimes, he feels like he’s changing as well the more he transforms. Not drastically, but enough for him to look back and notice.

He usually was someone who prided on being efficient and straight to the point.

But now he’s starting to… have fun.

He started using his claws whenever he could. Don't het him wrong, he still uses his guns plenty, but there was just something deeply satisfying about vaulting over things, scaling a wall or crawling on the ceiling with bare hands.

(Punching people is still the most satisfying by far, though.)

That one time hunting down the Joker wannabes was fun too.

(Danny said he’d get along great with Skulker? Did Jason want to find out? No.)

Fading in and out of invisibility, he picked them off one by one, watching as panic and dread slowly but surely creeped up on the remaining ones.

(After all, he has no respect for those trying to emulate the dead clown.)

—

(Yeah, the Joker was dead.)

(Surprisingly, that has not been a good day.)

—

One of the favorite things he liked to do was rooftop parkour. The… bendability of gravity is… fun, not gonna lie.

(Not flying though. Jason is used to having feet in regular contact with solid ground, thank you very much. No offense, Danny.)

But he gets why ghosts love to fly. When he’s jumping from rooftop to rooftop in Gotham in the at night, watching the city light fly by, cloak spread behind him, it’s as if nothing else matters.

(No Joker, no petty criminals to beat up, no avoiding the Bats so they don’t find out about his existence—)

He can just enjoy, even just for a little bit.

—

(Somehow the Demon Brat and Orphan could sense him. Will keep and eyes on those two, and also the more reasons to avoid them.)

(The real problem was the new Bat in town. Bruce, what the fuck, another one? Again?)

(The yellow one, Signal. No time to check his profile yet, but probably a meta or something.)

(First night out and the guy almost managed to actually fucking see him —looked at him straight in the eyes and all, then did a double take. Jason never phased into the pavement so fast in his entire fucking life.)

(And so far no Bats on his cloak tails yet.)

(He did help the guy incognito, just a couple of times.)

(And he also did steal his escrima sticks for fun, and once the guy went out looking for them, he’d put them right back where they were.)

(Turns out, he discovered later, that being a little shit runs in the ghost community.)

—

(Sometimes he also wonders what happened to Danny before they met.)

(He wasn't a Gothamite, that was obvious. He doesn’t pry, but it doesn’t take a lot to piece two and two together.)

(He just wonders who he has to kill this time.)

—

(Jason could not believe he forgot and underestimated just how fucking persistent every single one of the Bats could be. Of course it had to run in the family.)

He gazed down, thought the agony, at the gaping wound under his right armpit.

(The Bats have been chasing him relentlessly for a while now. He got more injuries than he can count, especially from Bruce.)

(They know. Oh, they know.)

(It didn’t go well.)

(He knows the others are there surrounding him to prevent him from escaping, he knows that Dick is right behind him, but at the moment he couldn’t care less.)

It has been a long time since the last time he got shot.

(It felt like someone set his right side on fire.)

What was flowing out in abundance was a neon, toxic green.

(The Pit Waters, ectoplasm, he didn’t even know that he could fucking bleed in ghost form—)

(Danny—)

He looked back up at Batman, holding a (frankly) ugly gun, white casing and highlights in the same shade of toxic green.

(A gun that Danny warned him about. And everything behind it.)

Jason felt something in him... snap.

(Why did it have to be you, Bruce.)

His mouth opened—

(waitsincewhenhecoulddothatthroughtthe mask—)

(Jason could see the billows of neon green smoke—)

(He couldn’t see Bruce’s expression.)

(Every. Single. Goddamn. Time.)

— and wailed.

---------------------------------------------------

I am genuinely delighted that my last post got that much attention! Thank you so much, to all who liked, rebblogged and commented, it really does mean the most. 💕

This AU may be continued? No guarantees, tho.

For those interested: Part 01

@fandomnerd103 @phoenixdemonqueen @satisfactionbroughtmeback @ascetic-orange @apointlessbox @bathildaburp @fisticuffsatapplebees @aisforanonymity @phandomhyperfixationblog @help-i-need-a-cool-username @hashtagdrivebywrites @did-i-miss-anyone-tagging-is-a-monk's-job-first-time-doing-this-aaaaaaaaaaaaaa

#jason todd#red hood#dc x dp#dp x dc#dc x dp crossover#danny phantom#halfa jason#halfa au#fanart#I may have subconsciously got myself inspired by spawn#as in like i figured it out on a random day halfway through the second painting#and went whooooooops i did it again#It took so long#cauz my perfectionism worked against me#a classic#*cries*#But thanks yall who read the tags#yall delightful#i guess art is a journey but im getting slapped by strong winds in the opposite direction#dc x dp prompt#dc x dp au#the inspiration to write only strikes at ungodly hours of the night i guess

3K notes

·

View notes