#I looked up restraining order laws for this. that’s in my search history now.

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

AU where Shen Jiu and Luo Binghe have a mutual restraining order, but then Shen Yuan tries to bring his new boyfriend home for dinner.

“A-Yuan he can’t come in the house.”

“Ge, I know you don’t like me dating, but-“

“No, he legally can’t come in the house. Or within 200 meters of me.”

#svsss#shen jiu#shen yuan#luo binghe#bingqiu#shen bros#I looked up restraining order laws for this. that’s in my search history now.#fish post

964 notes

·

View notes

Text

shine

Chapter 72

Jimmy didn’t sleep.

Not when they left the precinct. Not when Zariya was curled on the couch at Ari and Jey’s, tucked beneath one of Ari’s throw blankets, her lashes still wet from earlier tears. He stayed posted by the door like a guard dog, his broad frame shadowed in the dim hallway light, muscles tense, mind racing.

He didn’t speak much either. Just watched. Processed. Calculated.

But by morning, he was ready to move.

Zariya barely stirred as he kissed her forehead before heading out. “I’ll be back,” he murmured, brushing his knuckles across her cheek. “And when I do, you’ll never have to be scared again.”

She blinked up at him groggily, her voice soft. “Where are you going?”

Jimmy kissed her again. “To fix it.”

By the time the sun hit its peak, Jimmy had already pulled every string he could.

He walked into the precinct, calm but commanding. “Detective Barnes? We need to talk.”

The detective blinked up, surprised but intrigued. “Mr. Fatu. I was going to reach out. We’ve got some updates.”

Jimmy shook his head. “No disrespect, but I’m not leaving this in limbo. My woman’s being stalked. This is escalating. And I’m not waiting until someone gets hurt. So either you’re going to move this case up the priority list or I’m going over your head.”

The detective narrowed his eyes but didn’t challenge it. Jimmy continued.

“She’s not subtle anymore. She left her fingerprints. She left a knife and a pair of panties in my home. She’s trespassing, harassing, and escalating to threats. What more do you need to take her in for questioning?”

Barnes nodded slowly. “You’re right. We got a partial print off the knife left at your place. We just confirmed the match—Keisha Galloway.”

Jimmy exhaled like he’d just absorbed a punch, then leaned forward. “Good. Now you’ve got motive. History. Threat pattern. Arrest her.”

“She’s in the system now. If she moves, we’ll be on it.”

“Not good enough,” Jimmy snapped. “I want a protective order filed for Zariya. Today. I want patrols by her house, by this house, and I want her address flagged if her name gets searched anywhere in law enforcement systems.”

Barnes looked impressed now, not just with the urgency—but the focus. “We can do that.”

“Good. Because I’m not letting her look over her shoulder another damn day.”

Later that evening, Zariya was back at her place—hesitant, unsure—but Jimmy was already there, walking her through the new security.

“I changed the locks. Deadbolts. Cameras at every angle—entry, windows, backyard. I put a Ring cam on the front and back. I synced everything to your phone and mine. Jey’s too.”

Zariya just stared at him, speechless.

“And I talked to the department,” he continued. “Filed for the restraining order. They’ve got enough now to pick her up if she comes anywhere near you again.”

Zariya looked around, stunned. “You did all that?”

He walked up, arms wide, hands gentle as they cupped her shoulders. “Yeah. Because you shouldn’t have to do any of it. Not alone.”

Her eyes filled again, but it wasn’t fear this time. It was something heavier. Softer.

“I didn’t know what I was walking into when I came home today,” she whispered. “But this? You doing all this for me?”

“I love you,” he said simply. “Of course I’m gonna protect you. That’s what loving you looks like.”

Zariya leaned into his chest, and for the first time in days, her breath left her in something like peace. Safe.

Jimmy kissed the top of her head, holding her there.

“She’s not gonna hurt you,” he murmured into her curls. “Not now. Not ever.”

Chapter 73

It happened in the middle of a Tuesday afternoon.

Ari was pacing in her kitchen, phone in one hand, a half-finished cup of iced coffee in the other. Zariya sat quietly at the table, eyes fixed on the window, barely hearing a word of the conversation Ari was having with her cousin. Jey was in the backyard with their youngest, tossing a ball in the grass while Jimmy stood just behind Zariya, watching her.

It was still so new—this version of them where she wasn’t looking over her shoulder. But it hadn’t settled yet. The pit in her stomach still twisted. The thought that someone could still—

The doorbell rang.

Everyone tensed.

Jimmy moved first, followed by Jey. They opened it cautiously—but it wasn’t Keisha. It was a uniformed officer and Detective Barnes.

“You’ll want to sit down,” Barnes said as he stepped inside.

Zariya stood. “What happened?”

Barnes glanced at Jimmy, then nodded. “We got her. About forty-five minutes ago she was spotted near a hotel in Daly City trying to use a fake name. One of the clerks recognized her from the bulletin we issued after she popped up at your house.”

Ari let out a sharp breath. “Oh my God.”

“She had a duffel bag with her,” Barnes continued. “Inside were multiple printed photos—some of them from years ago. Several of you, Zariya. Of Jimmy. A few recent ones from what looks like surveillance. And... we found the rest of the undergarments.”

Zariya felt her knees wobble but Jimmy was there, steadying her.

“She’s in custody now,” Barnes said firmly. “We’re charging her with stalking, breaking and entering, harassment, trespassing, and intent to intimidate. The DA’s already on it. She’s not getting out anytime soon.”

Zariya’s breath hitched, tears spilling silently.

Ari moved to her side immediately, pulling her into a hug. “It’s over. You hear me? It’s over.”

Jimmy didn’t say anything—he didn’t need to. The way he stood behind her, arms wrapping around both Zariya and Ari, was enough. His jaw was tense, but his hand never left her side.

Barnes gave a few final notes on how they’d proceed, promising updates, before he and the officer left.

The house was quiet again. Heavy, but lighter somehow. Like a storm had finally passed.

Zariya turned to face Jimmy, her lip trembling.

“She’s gone?” she asked, needing to hear it again.

“She’s gone,” he said, touching his forehead to hers. “You’re safe now. For real this time.”

Jey let out a breath and clapped his brother’s shoulder. “You handled that like a damn man. Proud of you.”

Jimmy just nodded, his eyes never leaving Zariya.

And Ari—voice teasing, but eyes glassy—smiled through it all. “Well, I guess now we can finally move into the soft-launch, huh?”

Zariya laughed, tearful and warm, pressing her face to Jimmy’s chest.

“I want the hard launch,” Jimmy said, grinning, arms fully around her now. “This woman’s mine. Always has been.”

Chapter 74

The house was finally still.

Ari and Jey had taken the kids out for ice cream to give them space, and the quiet felt like something sacred. The late afternoon sun poured through the windows, casting a soft gold across Zariya’s living room. She stood near the couch, arms loosely wrapped around herself as she watched Jimmy lean against the doorframe, arms crossed, expression unreadable.

But she could feel the shift in the air. It wasn’t just that Keisha had been caught—it was the first time in days she’d felt her body begin to unclench. The first time she didn’t feel like she had to check behind her every time she moved.

Jimmy looked up at her finally, like he could feel her watching him.

“You okay?” he asked, voice low, worn but gentle.

Zariya didn’t answer right away.

Instead, she walked toward him slowly. Then, without a word, she slid her arms around his waist and laid her head on his chest.

He stilled—just for a second—then wrapped her up tight, like he’d been waiting on that cue.

Her voice came soft, muffled against his shirt.

“Thank you.”

“For what?” he asked, kissing the crown of her head.

“For protecting me. For showing up. For not backing down when I got scared or confused. For being the one who made me feel safe again.” She swallowed hard. “You’re my hero, Jonathan. I don’t even think you realize what that means to me.”

Jimmy’s arms tightened.

He didn’t say anything right away, just buried his nose in her curls and breathed her in like he needed the scent to believe this was real.

“You don’t ever have to thank me for loving you,” he finally said, voice cracking at the edges. “That’s all I’ve ever wanted to do. Protect you. Choose you.”

She looked up at him then, eyes shining, palms sliding up to gently cradle his face.

“You did. You chose me when I didn’t know how to ask. You showed me what it felt like to be safe... to be wanted.”

Jimmy bent just enough to kiss her forehead, then her cheeks, then her lips—soft, slow, lingering. A kiss that didn’t rush anything, didn’t need to prove anything. It just existed. Safe and warm and theirs.

And when they pulled back, Zariya smiled up at him, eyes full.

“You really my hero, Fatu,” she whispered, teasing the hem of his shirt now. “Might have to start calling you Superman.”

Jimmy smirked, arms still holding her close. “You know I look good in red.”

She laughed, and this time, it was full-bodied—free.

The kind of laugh that only comes after surviving something heavy.

He tucked her against his chest again, and for the first time in a long time, they both let themselves just breathe.

Together.

Chapter 75

It had been two days since the arrest. Two days since Jimmy held her like she was his entire world and promised she’d never have to feel alone again. And for the first time in weeks, Zariya had slept through the night.

When she woke, it was to an empty spot beside her and the smell of breakfast wafting through the house.

She padded barefoot into the kitchen, hair wild, his shirt hanging off one shoulder—and there he was. Jimmy Fatu, humming under his breath, shirtless in sweats, sliding pancakes onto a plate like he hadn’t just made her feel safer than any alarm system ever could.

“Morning, sleepyhead,” he grinned over his shoulder.

Zariya leaned on the doorway, smirking. “You trying to get husband points or something?”

He walked over with her plate and a fresh mug of coffee. “I’m trying to spoil my girl. Let me do that.”

Her lips parted slightly at the phrase. My girl.

But before she could even tease him, he nodded toward the dining room.

“Come on. I got something for you.”

She followed him, curious, until she stopped dead in her tracks.

The dining table was cleared, and sitting on top was a small velvet box next to a sealed envelope. A single white gardenia lay across the top.

“Jimmy…”

He scratched the back of his neck, suddenly looking shy. “It’s not jewelry. Not like that. Open it.”

Zariya reached for the box and lifted the lid. Inside was a delicate, gold locket—smooth and simple. But when she popped it open, her breath caught.

On one side was a tiny photo of her and Jimmy from the beach a year ago—one she hadn’t even known someone had taken. On the other, the engraved words: You were never just a friend.

She pressed her fingers to her lips, eyes welling.

“Open the letter,” he said gently.

Zariya set the locket down, careful as ever, and opened the envelope with trembling hands. Inside, his handwriting filled the page. No filter. Just him.

Z,

I know we never did things the easy way. I know I made you question how serious I was because I couldn’t give you the title when you needed it, when you deserved it. But you’ve always been mine. Even when I couldn’t say it out loud.

You told me I was your hero—but truth is, I’ve been scared as hell. Scared you’d run. Scared I’d never be enough. But that’s over now. I don’t want gray. I don’t want maybe. I want you.

So, if you’ll have me… consider this me showing up. No hesitation. No confusion. Just us.

Your man,Jonathan

She didn’t realize she was crying until the tears hit the envelope.

Jimmy stepped forward slowly, eyes searching hers. “You okay?”

Zariya launched into his arms, wrapping herself around him like she was afraid he’d disappear. Her voice cracked as she whispered, “You didn’t just show up, you came home to me.”

He kissed her—deep and grounding—then slid the locket around her neck himself, his fingertips brushing her collarbone.

“You’re mine, Zariya. All in. No more friend zones. No more gray.”

She smiled through her tears. “Good. ‘Cause I’m all in too, Fatu. And I’m keeping this locket forever.”

He kissed her again, arms wrapped tight around her waist.

This time, there was no danger waiting. No shadows looming.

Just love. Real, warm, grounded love.

Chapter 76

The evening was quiet, golden light spilling through the windows of Jey and Ari's kitchen as Zariya leaned over the counter, idly stirring her tea. Her curls were in a loose bun, her oversized hoodie barely hiding the glint of gold at her collarbone.

Ari caught it immediately—eyes narrowing with the kind of nosy best friend curiosity that had never once missed a detail.

"What's that?"

Zariya looked up, confused until Ari pointed at the charm around her neck.

"Oh." Zariya glanced down, fingertips brushing the locket instinctively. “Jimmy gave it to me.”

Ari tilted her head. “And you’re just casually wearing it like it’s not giving promise necklace energy?”

Zariya laughed softly, cheeks warming. “He gave it to me after… everything. After Keisha. After the cops. He didn’t say much, just said he wanted me to have something I could touch when I needed to remember I was safe.”

Ari blinked, suddenly quiet.

“I haven’t taken it off since,” Zariya admitted, her voice lower now. “It’s silly but… I feel grounded. Like he’s still protecting me even when he’s not physically there.”

Ari walked over, wrapping her arms around her from behind and resting her chin on Zariya’s shoulder. “That man loves you out loud. It’s not silly. It’s solid.”

Zariya smiled, the kind that tugged slow and full from the inside. “Yeah,” she whispered. “It feels solid.”

Chapter 75

The living room was dim, lit only by the muted glow of a late-night sports recap humming on the TV. Jey sat back on the couch with a cold bottle of water, one ankle resting over his knee. Jimmy leaned against the counter in the open kitchen, arms crossed, his eyes unfocused as he replayed the day in his head for what felt like the hundredth time.

“You good?” Jey asked without looking up.

Jimmy didn’t answer right away. He exhaled, running a hand down his face.

“She called me her protector,” he said finally, voice low like he was still processing it. “After everything… she just held me and said I made her feel safe.”

Jey glanced at him now, more alert.

“I’ve been in love with that woman since we were twenty, man. And for the longest time, I didn’t even think I deserved to protect her. Now she sees me that way? She trusts me like that?”

Jey smirked, lifting his brows. “It’s hittin’ different now that it’s real, huh?”

Jimmy gave a tired laugh, rubbing the back of his neck. “Nah, it’s hittin’ like peace. Like… I finally got a name to the feeling I been chasing all this time. She chose me, and it wasn’t outta desperation or fear or timing. She just… saw me. And still wanted me.”

Jey nodded slowly. “So what now?”

Jimmy looked over, eyes a little glassy but clear. “Now? I make damn sure she never regrets choosing me.”

Jey clinked his bottle against the countertop. “That’s what the fuck I’m talkin’ about.”

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Discussion I have on YouTube under video 'A Mediocre Recap of Mediocre Alternate History Shows' from AlternateHistoryHub

Sir Reginald Meowington 1 month ago Uh-oh here comes the Korra Stans. Back to the topic, I feel that some of the people who worked on Fringe most likely worked on Man in the High Castle. It's too early similar or they are Fringe fans.

Extreme Madness 1 month ago (edited) Becase she wasn't Mary Sue... an argument that ignores the original meaning and is actually used against any female character that shows even hints of self-confidence or arrogance or is even better at something than male characters. Aang learned and became a master of all four elements in less than 9 months, almost constantly dominating his opponents, somehow people don't consider him Mary Sue, Korra who spent 13 YEARS! of intense training, and despite that still could not airbending, struggling in fighting opponents who have some superior abilities, ended up in a wheelchair, recovered for more than three years from mental and physical trauma ... somehow it makes her Mary Sue, if she was a male character no one would even thought of considering him a Mary Sue...

Sir Reginald Meowington 1 month ago @Extreme Madness I like how you automatically assume that I dislike Korra out of misogyny or a hidden agenda despite enjoying female characters like She-Hulk, Wonder Woman, Rogue, Big Barda, Phoenix, Zarya (Overwatch), and Noi (Dorohedoro). Basically, women who fight like men and have the muscles/powers to prove it. There is a reason why I dislike Goku, Wolverine, Batman, and similar characters. Nice try on attempting to find a non-existent bias. When it comes to a wheelchair recovery story I prefer Barbara Gordon's journey and triumph to become Batgirl again, over Korra's lackluster 10-minute portrayal. There was more emotional weight seeing Barbara doing normal mundane tasks like eating, showering, attempting to walk (after failing numerous times), and talking to a therapist about her trauma in the course of several issues than it was for Korra getting a quick fix in one episode. Korra isn't a well-written character and it shows. She never has to own up to her mistakes like the time she broke up with Mako by wrecking his desk and threatening him for doing the right thing. Does she apologize for her behavior in the police station? Never. Did she apologize when seducing Mako so he can cheat with Asami or apologizes to Bolin for using him as a way to get Mako? Never. Does she apologize to Tenzin for yelling at him for being a horrible teacher? The story forgets it. Do any characters tell Korra she is making the wrong decision or that her going in fists first will cause more damage and be proven right. Nope. Was Korra shown to be wrong when wanting to create a fictional Gulf of Tonkin incident to get the United Nations in a war with the Northern Watertribe as careless and harmful? No. The plots dictate that she can never be wrong even when it could potentially put people in danger. Korra is given fixes too quickly. She gets her bending taken away. That's interesting. We can see her work through her anger, hurt, and self-delusion, Oh nope sorry she gets it back 5 minutes later after crying about it. Oh no she lost the past Avatars. Why should Korra care? She never talked to them or formed a relationship with any of them similar to Aang and Roku. Oh wow, she is disabled are we going to get two or three episodes where she deals with her new life in a wheelchair including how mundane tasks are now a struggle? Sorry, we don't get time for that or life-long PTSD, we have to rush the plot because we can't understand how to tell a story in 12 episodes. You can also tell how much of a fetish they have for brutalizing Korra and show it in meticulous detail. Ah yes, this is what I asked for more man pain and people wonder why I hate Wolverine.

Extreme Madness 3 weeks ago (edited) @Sir Reginald Meowington Even if everything you said was true (it isn't), that's still argument against her being Mary Sue (character that supposed to be ridiculously perfect and not having flaws and weaknesses). Her being in wheelchair was just part of her slow recovery through entire season (she didn't recover immediately, she was in wheelchair for months, while trying to walk again, and after that she was still recovering for 3 years). How is she guilty for Mako cheating? He have his own agency. If he really loved Asami he could just said that he wasn't interested. Korra give up to be with Mako anyway when she became friend with Asami, she even ask Mako to go to Asami after they escape from her father. Everything after that was on him. She didn't use Bolin to get Mako, she just go out with him to have fun. Bolin was the one who mistakenly thought that they are on date. Mako was technically right when he stop Korra attend, but he still did that behind her back, she was right to be angry, especially when it was desperate attempt to save her tribe from occupation. Isn't she apologized to Tenzin when she come back after learning what her uncle trying to do.

Sir Reginald Meowington 3 weeks ago @Extreme Madness "Even if everything you said was true (it isn't)," Talk about denialism there. I don't like the evidence you presented to me therefore it is not true. That doesn't refute anything I have said or why it's problematic. That just tells me you don't like any argument presented to you therefore everything you don't like is false or a lie. Just a reminder Korra isn't right to create a Gulf of Tonkin situation and starting a war will cost the lives of citizens who are unaffiliated with the conflict. (Looks at Vietnam and Spanish American War) It is not right for a high ranking member (General Iroh) to create a situation that leads to justification for war. You know what happens with that right? Court Martial and possible execution. We have whistleblower laws for a reason. Apologizing isn't enough. The writers should known better and have everyone call her out for it. It's the biggest reason why Korra is problematic in the show. The writers have no understanding of writing Korra or any political ideologies (Everyone ranting how Amon is communist is using red-baiting arguments) present in the show that they flaunt to make them appear edgy and mature. It's why Korra comes out bad for forcing a kiss on Mako and telling him "Yeah, but when you're with her, your thinking about me, aren't you?", never apologizing to Bolin for cheating only Mako apologized, having her disabilities skipped because they don't know how to scope within 12 episodes (Barbara Gordon did it better and in less than 30 pages), Asami getting back with her dad was brought up last minute and then he is dead. Just because someone apologizes doesn't mean they deserve forgiveness. Especially not after destroying property damage over a fit. You do that and I get the restraining order.

Extreme Madness 1 week ago (edited) @Sir Reginald Meowington I actually started watch the show again and look at that, you are full of shit, Korra actually apologize to Tenzin for calling him terrible teacher in second episode of Book 1! Korra didn't use Bolin to get closer to Mako, that's what Mako accused Korra for, doesn't make it true, Korra was actually right about his feelings for her, and Korra literally apologize to Bolin while healing his arm in episode 5 for whole situation. About situation when she desperately trying to free southern water tribe from occupation, it's interesting how you blame entire situation on her and not at her uncle. She have every right to be frustrated. She make only few brash decisions, in most situations she listens and work with others like when she listen Mako how they should save Bolin from Amon, she was doing that for the rest of the show, especially after she returns after having vision of Avatar Wan and learning what her uncle actually planning, in book 3 she surrender to Red Lotus so others can save Airbenders. About her recovery, you don't see the forest for the trees, her being in wheelchair was just part of her slow recovery, it wasn't only important part of it. When did Barbara Gordon stopped being Oracle? It's another lazy retcon from DC? DC couldn't work with other batgirls so they took one of rear example of superheroes with disabilities and make her somehow magically recover from spine cord injury. Lazy writing I'd say. Bad example. I will stay with Korra.

Extreme Madness 5 days ago @Sir Reginald Meowington "Does she apologize for her behavior in the police station? Never." I know you ignored my previous answers but ... Just a few days ago I watched the finale of Book 2 and look at that, Korra actually APOLOGIZED to Mako for that before they broke up! When you actually watch the show you see how many arguments arose from people who didn’t actually watch the show or didn’t pay attention to such important details.

Sir Reginald Meowington 5 days ago @Extreme Madness You lost all credibility when you put Barbara Gordon and Gail Simone under the bus to make Korra look good when a 10-minute google search into the story arcs and fan discussions regarding disabilities and whether or not she should walk again were ignored. Not to mention the decades of critiques and discussions of the event in The Killing Joke and the input of various writers who talked about it for decades in several series starting Barbara. Then you go by using ad-hominem attacks towards me by claiming I am a liar and that I don't watch the show. I quoted the episodes and the scene in the last comment that mysteriously disappeared including why that was problematic and how the show does not do a good job at addressing her faults. As mentioned before, apologizing after enacting violence against your partner during a break up is not enough. As I said when I addressed it, "Just because someone apologizes doesn't mean they deserve forgiveness. Especially not after destroying property damage over a fit. You do that and I get the restraining order." and this is the problem of the writers not understanding how to write Korra or her archetype. It is obvious she was sacrificed in the altar of man pain for character growth and the most abysmal love triangle since the Jean Grey/Scott Summers/Wolverine ship. It's the only reason why I started shipping Asami and Korra as I do with Jean Grey and Emma Frost due to the levels of toxicity. Of course, that would require you to have basic reading comprehension or understanding of social/political issues when moving the goal post so you don't have to address those ugly truths when questioning the romance even fans addressed was badly handled. So now you are trying to grasp at anything in an attempt to make yourself look good after calling you out about supporting a toxic relationship with a female abuser. But of course, it ain't toxic or bad when it's female on male. It's just for laughs.

Extreme Madness 5 days ago @Sir Reginald Meowington "apologizing after enacting violence against your partner during a break up is not enough" Originally you only claimed that she never apologized, which is a notorious untruth, now you claim that her apology is not enough, who here moving the goal post actually. "supporting a toxic relationship with a female abuser" What the hell are you talking about ?! Korra, abuser ?! Go fuck off. I also don't care about the convoluted mess that DC and Marvel comics are for which no one knows which continuum they follow anymore. So no I don’t want to see them as an argument.

Sir Reginald Meowington 5 days ago @Extreme Madness Saying they don't count as an argument because it is not your preference is a lame excuse to dismiss evidence regarding a comparison between two similar story arcs between Korra and Barbara. As for the other point It would be good of you to stop time traveling between comments and look at the entire picture of why throwing your partner's desk while they are at work during an argument is problematic. As defined by several resources that talk about relationship and spousal abuse.

It is not okay for your significant other to throw or breaks things when angry in front of you even if they have no intention of physically hurting you.

That is a person who is purposefully threatening you and reestablishing the power dynamics of control/dominance when their partner does something they do not like. That is a person with massive anger issues who is one step away from physically hurting you someday. It's a big red flag that you need to get out and it's only going to escalate from there. There is no excuse for that kind of behavior, no excuse for your partner to throw items in front of you, no excuse for them intimidating you, and no excuse for creating a scene or atmosphere of violence. That is damaging to the psyche of the person that it is enacted upon. In any situation, get out and contact the authorities immediately don't wait, especially if you feel you are in danger. Grab your things, file a protection order, and don't look back. Nobody should vent or release their anger at someone like that.

Ugh...

How do I answer this, they first claimed that Korra never apologized to anyone and that her recovery is worse than some completely different character who has nothing to do with her and now claims that Korra was abusive in her relationship with Mako. I don't know what to say anymore...

1 note

·

View note

Note

you've made me change my opinions on gun control but the parkland students have me question that again. what's your take on their activism?

I mean my views aren’t based on current events, they’re based on what seems to be effective and what doesn’t seem effective to me. “Ban assault weapons” sounds cool to lots of people but 1) we did try banning “assault weapons” (used in the Clinton ban to mean semi auto rifles that looked scary) from 1994 to 2004 when they were actually hard to get- if our goal was to limit availability this was the PERFECT TIME, when they cost a grand and there weren’t many of them in the country- and EVEN though the number of them actually ROSE during the ban as manufacturers designed around the ban 2) there’s no conclusive evidence that it managed to reduce spree shootings, as shooters just switched over to other kinds of semi auto rifles and handguns. So it’s a bandaid solution that doesn’t even seem to work well under the best conditions- when they are already hard to get and there aren’t that many of them in the country. There’s an estimated 3 million AR-15s in the country now ALREADY, I would guess that number is -at least- 5x, and maybe even 10x, lower than the actual number, there are kits being sold to build lower receivers in your garage with a $200 press and some time, and on top of that you can build a decent (not premium, not shit) rifle yourself for $500, you can buy one off the rack for $400. There is no future for this country where, imo, knowing what I know about availability of parts, an AR is all that hard to get. The people I’m personally worried about anyway (violent neonazis) are watching the news and will have 5 or 6 more before midterms elections. Nobody is gonna turn in their rifles when asked or even when compensated- I’d be surprised if you got 1 million back under a buyback. Like if we had seen a massive decrease in spree shooting during the AWB of ‘94, I would support bans. But not only did we not see that, not see any impact on violent crime, but we saw a modest decrease in the use of banned weapons specifically in spree shootings (which, no, does not mean less lethality when the round an AR shoots is also in plenty of other rifles that look less scary and like hunting rifles) and all rifles from hunting rifles to the AR account for less than 5% of all gun homicides in the country. Even when considering that rifle rounds seem generally to kill at a higher rate, .223 in particular is so underpowered a round the military is likely to switch away from it soon and it’s not uncommon for people to survive 3 or 4 shots with it, so this idea that the AR is outrageously lethal doesn’t hold up. Your odds of making it after getting shot with it aren’t great but they’re better than if you’re shot with grandad’s bolt .308 or.303 rifle.

“Ban so-called large capacity magazines” also sounds cool to lots of people but it takes an amateur less than 3 seconds to reload and a well trained shooter hardly over a second, and cops have a habit of showing up to spree shootings and waiting for shooting to stop completely rather than directly getting in there- this fantasy that anybody, let alone cops, will wait for a reload to try to get a shot is a fantasy. Cops are not legally obligated, as of the most recent court cases, to come into a dangerous situation and do shit to “protect” you. They’re gonna wait outside and fret while people die. So those idea that 10 rounds is a magical number where your shooter won’t just switch magazines when cops are not going to intervene anyway is silly. What I WILL say is your odds of surviving a handgun shot in this country are great (if I’m ever shot with a pistol I have 80% odds of making it out alive) and rifle rounds tell to have a higher lethality rate because of what we have good trauma care for. I would be less upset to see them go than ARs because, again, you can just reload quickly. A 10 round magazine doesn’t mean 10 people get shot when you can just buy more magazines.

I don’t ideologically oppose licenses for firearms purchases, and we have them in my state- minor annoyance to get but 10 bucks and not difficult, and even though mine required no test or class (unlike my concealed carry license) I don’t think requiring a sort of written and shooting exam to ensure basic proficiency is that unreasonable. I also think it does nothing to prevent violence. Someome capable of handling a gun well enough to kill people should be able to pass a basic course, and someone who plans their massacre for months is going to laugh at a waiting period. Most of these men have plans and there’s no reason to think they couldn’t just plan to take a course too. So I don’t actively support licensing measures- again because I have no reason to think they’d be effective. When building policy the goal is to do things that work. Not just to do a thing for its own sake.

So the three most common ideas to stop this stuff are both likely to just not be effective and I don’t support them for that reason even BEFORE you consider my ideological oppositions to disarming regular people and leaving cops with tanks. I do think this kind of violence might be better prevented with something like my state has where if you’re under a restraining order (as many men who eventually commit domestic violence are before committing that violence) then a friend or the state is required to hold your guns while you fight it in court. Judicial oversight is critical though- I don’t trust judges but I definitely don’t think anyone should be deprived of a constitutionally guaranteed right with no chance to appeal. It goes a bit further than barring domestic abusers from owning guns- which is ALREADY FEDERAL LAW, the ATF just doesn’t actually enforce that law by searching whether someone just convicted of domestic violence has already bought guns. If you’re just barred from buying more but have 10 in the house, that’s obviously stupid. Oregon has a new law where neighbors and friends can suggest to a judge that you be disarmed, but it doesn’t require the “accused” to even be in court as it’s figured out, which is bullshit. It is a good idea that a judge has to actually look at evidence and make that decision, and that it can be appealed. With any kind of rights revokation I think judicial oversight is a good thing. I also think it's an issue that 12 states don't report well to NICS because the background check system only reads what records it has- and I think we need a law REQUIRING military and law enforcement agencies to report internally investigated affairs that bar someone from owning firearms. The Air Force just quietly slipped 4000 more personnel names to the FBI that it hasn't submitted to it. That has to stop. Cops being domestic abusers (when they abuse at almost 50% higher rates than the general population) should not happen and should not be preventable by internal investigations. Committing a crime that prevents you from owning and using firearms should actually...prevent that. I do not think that law enforcement and military agencies should be able to investigate themselves at all in any capacity anyway in addition to...all the other things I also think about these groups. The Sutherland Springs shooter having been not reported to the FBI, many cops having DV investigations handled internally and still carrying a gun every day, these are ACTUAL loopholes around current law.

I think a lot of people see this stuff and go “Oh my goodness gun violence” and think this is what drives national gun murder numbers. It isn’t. Remember than murders using “assault rifles” account for less than 5% of all gun murders, not even counting other kinds of homicides like stabbing. There is one approach for spree violence- these men all seem to have histories of violence against women as the greatest single common thread between them and I still think addressing that (like with the restraining order law we have here) is the single greatest measure you’ve got, although that requires not just women reporting but women being BELIEVED by judges. If you wanted to actually talk about gun violence in general, you would be talking about handgun murders since they’re the majority of those in the country. But “gun violence” and “spree shootings” are not at all the same phenomenon and don’t really have a single set of solutions between both.

I have no interest in bullshit about mentally ill people being violent- not only are mentally ill people more likely to receive violence than cause it, but someone who plans a massacre and puts peices together, and carries it out, and even escapes after, is not IMPAIRED BEYOND ABILITY TO CARE FOR THEMSELF as is currently the legal threshold for disarmament; somebody who’s depressed (which, it can be depressing world- lots of people are depressed) should also not be stripped of firearms rights without judicial review spurred by someone seeming to be a threat to themself or others; no diagnosis should allow someone to be stripped of a rigjt automatically and anyway I domt want the FBI looking at people’s health records without good cause when there is no diagnosis thst means you’ll murder someone. Plenty of mentally ill people manage not to kill someone every day. Sometimes people are just bad and the goal here is to limit the damage they can do. I don’t have answers but I also don’t pretend to. What I can say is that this kind of behavior displayed by the Parkland shooter (including, my newest CNN alert says, holding people at gunpoint) should be grounds for at least temporary disarmament. I also have no interest in talking about it in terms of “needs,” considering there are all kinds of dangerous things (harder to get than guns but available) that I also don’t need, like an excessively heavy truck or a car that goes over 80 miles an hour or a sword of literallt any kind.

So no, my opinions haven’t changed because I don’t have new information about the efficacy of the measures most people are still calling for. We tried an “assault weapons” ban and it didn’t work when they were 10 times harder to get and twice as expensive and much less commonly owned than they are now. We have no evidence it worked. Whatever we try, it needs to be something other than an ineffective policy that didn’t work under the best conditions for it. Typed this on mobile and may add links later when I can/this probably has some good ole phone typing typos.

390 notes

·

View notes

Text

News reports and interesting up-dates on POS Hardware and POS.

Every Juneteenth, as soon as Pamela Baker got to Booker T. Washington Park, she’d race to the merry-go-round, squeeze through the swarm of shrieking kids, grab one of the shiny rails, and hold on tight. After a few minutes, she would jump off and dart up the steps of the nearby dance hall to survey the throngs below. She and her brother Carl would weave through the crowd, looking for cousins from Dallas and Houston they hadn’t seen since the previous year. Eventually, her whole family would congregate under an oak tree their ancestors had claimed as a gathering place a century before, in the years after news of the end of slavery reached Texas.

“Every year, this is where we’d be,” Baker said. It was a cold January day, and she sat in a purple pew in the park’s open-air tabernacle. Baker, sixty, wore camo pants, a hoodie, and a knit cap. She had come from work and looked tired as a heavy rain beat down around her. The park sits along Lake Mexia (pronounced “muh-hay-ah”), about thirty miles east of Waco. For generations, African Americans made pilgrimages to this spot to celebrate Juneteenth, or Emancipation Day. They came from all over the country to hear the reading of the Emancipation Proclamation, to worship, to run and play in the green fields, to dance in the creaky pavilion, to eat barbecue and drink red soda water, to sleep under the stars. Locals referred to the park by its name from an earlier time: Comanche Crossing. Juneteenth here would run for days on end. It was like a giant family reunion, held on hallowed ground.

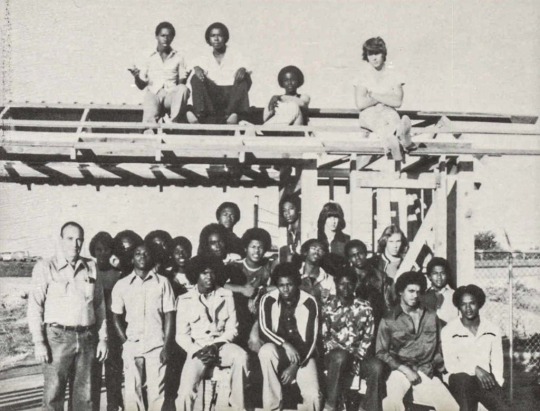

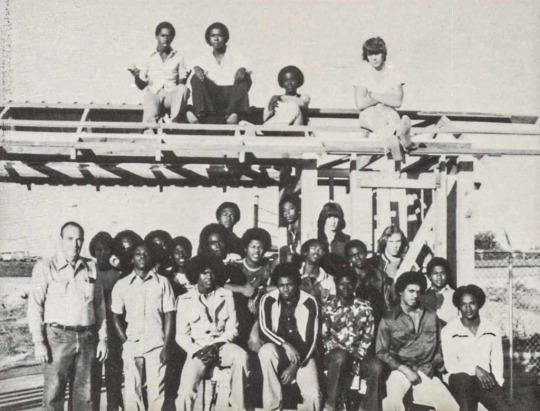

The merry-go-round at the park on April 21, 2021.Photograph by Michael Starghill

Baker grew up in nearby Mexia, and each June, her family would camp around that same towering oak. In the early sixties her grandfather built a wooden countertop around the trunk, and every June 19, her grandmother and members of her grandmother’s social club would fry scores of chickens in an old black washpot—enough to serve a few hundred people who’d stop by to sit, eat, and reminisce. “Juneteenth meant everything to us,” Baker said. As a kid, she looked forward to the holiday all year long.

Until she didn’t.

“After what happened with my brother,” she said, “we weren’t interested in coming out here anymore.”

Forty years ago, on June 19, 1981, not far from where she sat now, her brother Carl and two other Black teenagers drowned while in the custody of a Limestone County sheriff’s deputy, a reserve deputy, and a probation officer. The Baker family was devastated—as was the entire town of Mexia. The deaths became national news, with people from New York to California asking the same question as those in Central Texas: Why had three Black teens died while all three officers—two of them white, one Black—survived?

Over the years, whenever a highly publicized incident of police brutality against a Black person occurred, many in Mexia would think back to that night in 1981. This was never more true than last summer, when outrage at George Floyd’s murder, captured on video in broad daylight, sparked one of the largest protest movements in U.S. history. As millions of demonstrators took to the streets, Mexia residents were reminded of the drownings that once rocked their community and forever changed their hometown’s proud Juneteenth celebration, which had been among the nation’s most historic.

Four decades later, Baker still grieves for her brother. “It never goes away,” she said quietly, sitting in the pew, surrounded by the ghosts of her ancestors. “I miss everything about Carl—just seeing his smile, his dark skin with beautiful white teeth, walk into the house after work. I wish I could see him come up out of the water right now, but I know I can’t.”

She paused and looked toward the lake. “My brother,” she said, “he didn’t deserve that, what they did to him.”

Pamela Baker sitting in the park tabernacle on April 21, 2021.Photograph by Michael Starghill

James Ferrell was at Comanche Crossing on June 19, 1981. It was a clear, warm Friday night, and Ferrell, a tall 34-year-old who sported a scruffy beard and a cowboy hat, had led a trail ride to the park from nearby Sandy. He sat with his brothers, cousins, friends, and their horses, drinking beer, telling stories, laughing. They could hear music coming from the pavilion and see a line of cars creeping over the bridge onto the grounds, while pedestrians who had parked two miles away on U.S. 84 hiked through the gridlock. The moon was almost full, and the air smelled of grilled burgers, fried fish, and popcorn.

Sometime after ten, three law enforcement officers clambered into a boat on the other side of the lake and pushed off. Lake Mexia is a shallow, dammed stretch of the Navasota River in the shape of an M; the park sits near the lake’s center, where the water is about two hundred yards across. The Limestone County Sheriff’s Office had set up a command post on the opposite bank. The deputies rarely patrolled the park after sundown, but on this night they did. Because the bridge was bottlenecked, they cut across the lake in a fourteen-foot aluminum vessel. They were led by sheriff’s deputy Kenny Elliott, 23, who’d been on the force for about a year. The Black officer, reserve deputy Kenneth Archie, was also 23 and a former high school basketball player from Houston. The third man was David Drummond, a 32-year-old probation officer who planned to check on some of his parolees.

The boat hit the shore, and the men climbed onto the bank, which was muddy from recent rains. Though the three officers wore street clothes, they stuck out in the nearly all-Black crowd of roughly five thousand. “Police have a special way of walking,” recalled one bystander. They stopped at the concession stands to buy some soft drinks, then moved on. Young lovers walked through the crowd, eating cotton candy. Elderly men and women, many wearing their Sunday best, perched on benches talking to old friends. Everywhere the officers walked, they saw tents and campers with families gathered around. Some folks were dozing, some were playing dominoes, some were drinking beer or whiskey. Some were smoking marijuana, and as the officers passed, they either snuffed out their joints or hid them behind their backs. “When they came up,” Ferrell said, “we just put it down. They never said nothing. They walked off.”

As the trio approached one of the park’s small caliche roads, they came upon a yellow Chevrolet Nova stuck in traffic. Inside were four local teenagers: Carl Baker, Steve Booker, Jay Wallace, and Anthony Freeman, whom friends called “Rerun” because he resembled the hefty character from the sitcom What’s Happening!! As Elliott shone his flashlight through the windshield, he saw the teens passing a small plastic bag of what he took to be marijuana. It was just after eleven, and in the time since he’d crossed the lake, Elliott hadn’t acknowledged similar violations of the law. Now, though, the deputy ordered the four out of the car and made them put their hands on the roof while the officers patted them down and searched the interior.

A bridge over Lake Mexia.Photograph by Michael Starghill

They found the baggie of weed and a joint, which they confiscated. Wallace would later say that the officers “didn’t act like they knew what they was doing; they kept asking each other what they should do.” The crowd began to take notice. As far as anyone could remember, there had never been an arrest at the park during Juneteenth festivities.

Elliott made the decision to take Baker, Freeman, and Booker into custody. Days later, Wallace would tell the Waco Tribune-Herald that the officers found drugs on Baker and Booker, while Freeman was arrested because the car belonged to him. Wallace was spared because “they didn’t find anything on me.”

At least two and possibly all three of the teens were handcuffed; some witnesses said Baker and Booker were cuffed together, while others recalled each being restrained individually. Onlookers didn’t like what they saw, and some began to curse at the officers. Rather than walk the teens through the crowd, over the bridge, and around the lake, the officers opted to go back the way they came.

When the group reached the boat, Elliott climbed into the back by the motor. Next were Booker and Baker, then Drummond and Freeman. Archie, who weighed more than two hundred pounds, sat in the bow. There were no life jackets, and the combined weight of the passengers exceeded the boat’s capacity by several hundred pounds.

Elliott started the motor. The craft had no running lights, and as it crept forward, water started pouring in. Drummond yelled back to Elliott, who couldn’t hear him over the engine; Drummond yelled again, and this time Elliott turned it off. By then, they had traveled about forty yards. As the boat slowed, more water rushed in, and the craft submerged and flipped over. All six began splashing wildly in the ten-foot-deep water.

Elliott shouted for the others to stay with the boat while he swam to shore for help. As soon as he reached water shallow enough to stand in, he fired his gun into the air, in what he would later say was an attempt to summon assistance. Soon after, he was joined by Drummond. Out on the water, Archie, who wasn’t a good swimmer, clung to the boat “like a spider,” one witness said.

The teens were nowhere in sight.

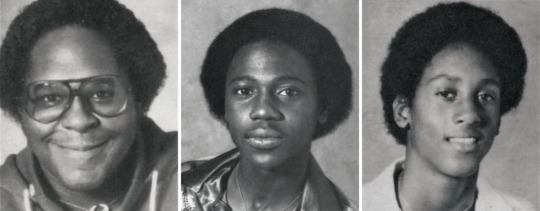

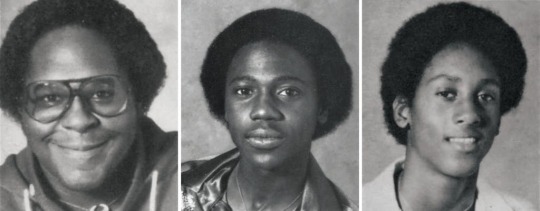

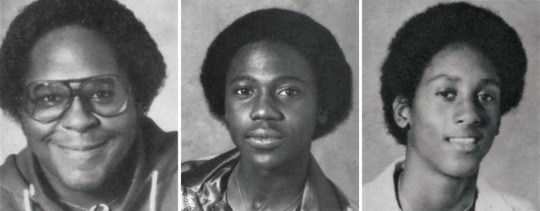

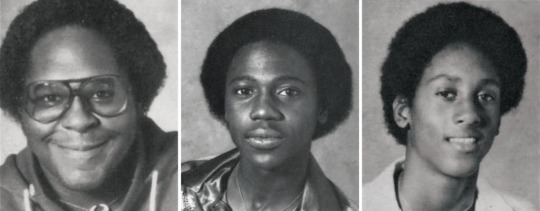

Mexia High School yearbook photos of Anthony Freeman, Carl Baker, and Steve Booker.Gibbs Memorial Library

While a boater pulled Archie out of the water, Elliott and Drummond ran across the bridge to the command post to report what had happened. Someone called the fire department, and before long a search party was on the lake. As campers watched from the shore, firefighters in three boats threw dredging hooks into the water. Onlookers hoped against hope that the teens had been able to swim to safety.

Around 2 a.m., the crowd’s worst fears were realized. A body was found near the bridge, tangled in a trotline. An observer, David Echols, said the rescuers positioned their boats between the body and the civilians and spent twenty minutes pulling it out. “They were shielding the bank where we couldn’t see.”

The body was Baker’s. The searchers brought him back to shore, where they took a couple of hours to regroup before returning to the lake at dawn. All the while, Juneteenth campers kept watch. Mexia was a small town where just about everybody knew Baker, Freeman, and Booker. They were country boys who had grown up playing at the local pool and in this very lake, although Freeman was scared of water, and his mother said he “couldn’t swim, not one lick.” Baker and Booker, however, were known to be excellent swimmers. “Carl was like Mark Spitz,” said his friend Rick Washington. “He could dive in the pool and swim underwater and come up at the other end.”

“Carl was like Mark Spitz,” said his friend Rick Washington. “He could dive in the pool and swim underwater and come up at the other end.”

How could Elliott, Archie, and Drummond survive while all three teens were presumed lost? Many witnesses had seen the teenagers marched through the crowd with handcuffs on. Had the handcuffs stayed on in the boat?

About 1:30 p.m., another body was found near the bridge. Three rescue boats formed a circle around it, blocking observers from making out the crew’s actions. “They took a while before they pulled the body out,” said a reporter who covered the search, “but we couldn’t see what they were doing.” What they were doing was retrieving Freeman’s body from the water.

The apparent secrecy fueled more suspicions, which intensified as the search for Booker continued. The next day, his body floated to the surface not far from where the others had been found. By then, many in Mexia who’d heard about the drownings believed that the teens had been handcuffed when the boat flipped. A hot-dog vendor named Arthur Beachum Jr. told a reporter about seeing Baker being removed from the water. “I saw them pull the body from the lake and it still had handcuffs on it. One officer took them off and put them in his pocket.”

Sheriff Dennis Walker denied this to the press. “It was a freak accident,” he said. “All of what they’re saying is untrue.” Reserve deputy Archie told a reporter that two of the teens had been handcuffed together but that the cuffs had been removed before Baker, Booker, and Freeman were led into the boat. According to the Dallas Times Herald, Archie also said that if he’d been in charge, things would have been different: “I probably would’ve pulled the marijuana out and put it in the mud puddle next to the car and sent the suspects on their way.” (He later denied saying this.) Sheriff Walker said, “This could turn out to be a racial-type deal.”

That was an understatement. Reporters and TV crews from Waco, Fort Worth, Dallas, and Houston arrived in Mexia. By Sunday, the drownings were national news. “Youths Allegedly Handcuffed,” read a headline in the New York Times. The NAACP sent a team of investigators and demanded the Department of Justice conduct an inquiry. Someone from the DOJ called the sheriff on Monday morning and was given directions to the sheriff’s headquarters in Groesbeck, the county seat. The FBI came too.

Richard Dockery, the head of the Dallas NAACP, examined Baker’s body and told reporters he thought that the position of the young man’s hands—wrists together, fingers curled—meant he had been cuffed. Initial autopsies of Baker and Freeman, done in Waco, found no bruising or signs of struggle, prompting Booker’s mother to announce she was taking her son’s body to Dallas because she wouldn’t get “anything but lies” from Waco pathologists.

Reporters rang the sheriff around the clock, and Walker later complained that the attention “severely hampered” his investigation. “The press has been calling me day and night from as far away as Chicago and New York,” he said. “I had to leave the house to get a couple of hours of rest.” Mexia’s mayor called the coverage “sensationalized,” while many white townspeople felt torn between defending their home against its portrayal as a racist backwater and acknowledging the wrong that had been done. “I was at a laundromat yesterday,” a white waitress told a reporter from Fort Worth, “and usually everyone gets along alright, but yesterday some of the Blacks were kind of testy . . . and I don’t blame them.”

The drownings had exposed a deep rift in Mexia, one that went back generations and couldn’t be smoothed over. “My God, this has turned the whole town upside down,” a local man told the Waco Tribune-Herald, “and those three boys ain’t even in the ground yet.”

The pavilion and tabernacle at Booker T. Washington Park on April 21, 2021.Photograph by Michael Starghill

Rick Washington was in the Navy in June 1981, stationed aboard the U.S.S. Tuscaloosa in the Philippines, when a shipmate handed him a newspaper. “Wash,” he said, “ain’t this where you’re from? M-e-x-i-a, Texas?” Washington, then twenty, read the headline about a triple drowning. Then he saw the names. “I just broke down like a twelve-gauge shotgun. Steve, Carl, Rerun. They were my best friends.”

Now sixty, Washington is the pastor at Mexia’s Greater Little Zion Baptist Church, and every day he drives past places where he and his friends used to play. “We would eat breakfast, leave home, come home for lunch, leave again, be home before the streetlights came on,” Washington said. “We were almost never inside.” They would ride bikes, play football and basketball, hunt rabbits, swim at the city pool, and explore the rolling, scrubby plains.

Washington, like everyone else in Mexia who knew Baker, Freeman, and Booker, remembered them as typical small-town teenagers. Baker was short, handsome, and athletic. He liked hanging out at the pool—he was such a good swimmer that the lifeguards sometimes asked him to help out when it got busy. He’d graduated from Mexia High School the previous year and was working at a local cotton gin. He was nineteen, with an easy charm and a voluminous Afro that had taken months to grow out.

Anthony Freeman, the youngest of the three at eighteen, was an only child of strict parents. He played piano, performing every week at the church his family attended. “He was a very bright kid,” said Shree Steen-Medlock, who went to high school with Freeman. “I remember him trying to fit in and not be the nerdy kind of guy.” He had graduated that spring, and he and Baker planned on going to Paul Quinn College, then in Waco, in the fall.

Nineteen-year-old Steve Booker was the group’s extrovert. “He was flamboyant, like Deion Sanders,” said his friend John Proctor. Booker was born in Dallas and raised on his grandparents’ farm in Mexia, where he helped to pen cattle, feed hogs, and mend fences. He loved basketball and grew up shooting on a hoop and backboard made out of a bicycle wheel and a sheet of plywood. Once, playing for Mexia High’s JV team, he hit a game-winner from half-court. In 1980 Booker moved back to Dallas, where he graduated high school and found work at a detergent supply company, but he’d returned that week to celebrate Juneteenth.

The Mexia where the three grew up was a tight-knit city of roughly seven thousand, about a third of whom were Black. Kids left their bikes on the lawn, families left their doors unlocked, and horses and cattle grazed in pastures on the outskirts of town. Boys played Little League, and everybody went to church. Mexia was known as the place near Waco with the odd name (which it got from the Mexía family, who received a large land grant in the area in 1833). City leaders came up with a perfect slogan: “Mexia . . . a great place to live . . . however you pronounce it.” Football fans might have heard that NFL player Ray Rhodes grew up there; country music fans knew Mexia as the home base of famed songwriter Cindy Walker.

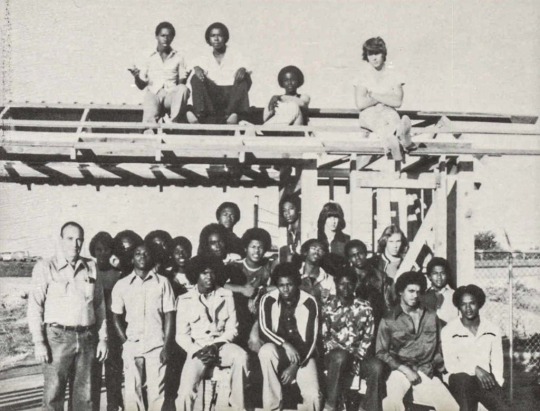

The VICA Building Trades club at Mexia High School in 1979, which included Carl Baker, Anthony Freeman, and Jay Wallace.Gibbs Memorial Library

Black Texans knew Mexia for something entirely different: it was the site of the nation’s greatest Juneteenth celebration. The holiday commemorates the day in 1865 when Union general Gordon Granger stood on the second-floor balcony of the Ashton Villa, in Galveston, and announced—two and a half years after the Emancipation Proclamation—that enslaved people in Texas were, in fact, free. Word spread throughout the state and eventually reached the cotton-rich region of Limestone County. Formerly enslaved people in the area left plantations and resettled in tiny communities along the Navasota River with names like Comanche Crossing, Rocky Crossing, Elm, Woodland, and Sandy.

They had to be careful. Limestone County, like other parts of Texas, was a hostile place for newly freed African Americans. In the decade after emancipation, the state and federal governments had to intervene in the area on multiple occasions to stop white residents from terrorizing Black communities. Historian Ray Walter has written that “literally hundreds of Negroes were murdered” in Limestone County during Reconstruction.

The region’s first emancipation festivities took place during the late 1860s, in and around churches and spilling out along the terrain near the Navasota River. “If Blacks were going to have big celebrations,” said Wortham Frank Briscoe, whose family goes back four generations in Limestone County, “they had to be in the bottomlands, hidden away from white people.”

Over time, several smaller community-based events coalesced into one, gravitating to a spot eight miles west of Mexia along the river near Comanche Crossing. There, families would spread quilts to sit and listen to preachers’ sermons and politicians’ speeches. Women donned long, elegant dresses, and men sported dark suits and bowler hats. They sang spirituals, listened to elders tell stories of life under slavery, and feasted on barbecued pork and beef.

In 1892 a group of 89 locals from seven different communities around Limestone County formed the Nineteenth of June Organization. Six years later, three of the founders and two other men pooled $180 and bought ten acres of land along the river. In 1906 another group of members purchased twenty more acres. They cleared the area, preserving several dozen oak trees, alongside which members bought small plots for $1.50 each. The grounds were given a name: Booker T. Washington Park.

The celebration continued to grow, especially after oil was discovered in Mexia, in 1920. Some of the bounty lay under Black-owned land, and money from the fields gave the Nineteenth of June Organization the means to build the park’s tabernacle and a pavilion with concession stands. During the Great Migration, as Black residents left Central Texas for jobs in New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles, they took Juneteenth with them, and word spread about the grand festivities along the Navasota River. Every year, more and more revelers came to Comanche Crossing, bringing their children and sometimes staying the entire week. Some built simple one-room huts to spend nights in; others pitched Army tents or just slept under the stars. During the busiest years, attendance reached 20,000.

James Ferrell’s Black Frontier Riding Club on a trail ride to the Juneteenth celebration at Comanche Crossing, year unknown.Courtesy of James Ferrell

On the actual holiday, it was tradition to read aloud the Emancipation Proclamation, along with the names of the park’s founders. Elders spoke about the holiday’s significance, and a dinner was held in honor of formerly enslaved people, some of whom were still alive. “You instilled this in your children,” said Dayton Smith, who was born in 1949 and began attending Juneteenth at Comanche Crossing shortly before his first birthday. “It had been done before you were born, by your parents and grandparents. Don’t forget the Emancipation Proclamation.Your parents didn’t come here every year just because. They came because of the Emancipation Proclamation at Juneteenth.”

Kids would grow up going to Comanche Crossing, then marry, move away, and return, taking their vacations in mid-June and bringing their own kids. “It was a lifelong thing,” said Mexia native Charles Nemons. “It was almost like a county fair. If you were driving and you saw someone walking, you’d go, ‘Going to the grounds? Hop in!’ ”

At the concession booths, vendors would sell fried fish, barbecue, beer, corn, popcorn, homemade ice cream, and Big Red, the soda from Waco that became a Juneteenth staple. Choirs came from all across the country to sing in the tabernacle. Sometimes preachers would perform baptisms in the lake, which was created in 1961, when the river was dammed.

The biggest crowds came when Juneteenth landed on a weekend. Renee Turner recalled attending a particularly busy Juneteenth with her husband in the mid-seventies. “My husband was in the service, and we couldn’t even get out,” she said. “He had to be back at Fort Hood that Monday morning, and so I remember people picking up cars—physically picking up cars—so that there would be a pathway out.” Everyone, it seemed, came to Juneteenth at Comanche Crossing. Daniel Keeling was an awestruck grade-schooler when he saw Dallas Cowboys stars Tony Dorsett and Drew Pearson walking the grounds. “If you were an African American in Dallas or Houston,” Keeling said, “you made your way to Mexia on the nineteenth of June.”

Even as Mexia’s Black residents took great pride in the annual Juneteenth festivities at the park, back in town they were still denied basic rights. Ferrell, who started spending the holiday at Comanche Crossing as a kid in the fifties, recalled life in segregated Mexia. “Up until the sixties, you still had your place,” he said. “If you were Black, you drank from the fountain over there, whites drank from the one over here, and if I went and drank in the fountain over here, well, I got a problem.” Back then, many Black residents lived near a commercial strip of Black-owned businesses called “the Beat,” along South Belknap Street, where they had their own movie theater, grocery stores, barbershops, juke joints, cleaners, and funeral home. When white and Black residents found themselves standing on opposite street corners downtown, the Black pedestrians had to wait for their white counterparts to cross first. “We couldn’t walk past each other,” said Ray Anderson, who was born in 1954 and went on to become Mexia’s mayor. “And if it was a female, you definitely better stay across the street or go the other way. You grew up knowing you couldn’t cross certain boundaries or you’d go to prison—or get hung.”

For years, the only law enforcement at Lake Mexia during Juneteenth consisted of a few well-known Black civilians. One was Homer Willis, an older man who had been deputized by the sheriff to walk around with a walkie-talkie, which he could use to radio deputies in case of an emergency. In the late seventies, more rigorous licensing requirements made such commissions a thing of the past, and the sheriff set up a command post across the lake where officers would hang out and wait. They stayed mostly on the periphery, helping to direct traffic and occasionally crossing the lake to break up a fight.

Until June 19, 1981, when, during the peak hours of one of the biggest Juneteenth celebrations in years, three officers piled into a small boat, started the motor, and cruised across narrow Lake Mexia.

The concession stands at Booker T. Washington Park.Photograph by Michael Starghill

When Baker and Freeman’s dual funeral was held in Mexia, so many mourners planned to attend the service that it had to be convened at the city’s largest church, First Baptist. Even so, the 1,400-seat space couldn’t accommodate them all. Baker and Freeman were remembered as kind young men who never hurt anyone and never got in trouble. At one point, Freeman’s mother, Nellie Mae, broke down, fainted, and had to be carried out. She insisted on returning for one last look at her only child before she was rushed to the hospital.

The district judge in Limestone County, P. K. Reiter, hoped that a swift investigation would defuse the escalating racial tensions. “We need to clear the air,” he said, announcing the opening of a court of inquiry, a rarely used fact-finding measure intended to speed up proceedings that would normally take months to complete. The court lacked the authority to mete out punishment, but it could refer cases for prosecution. Reiter asked the NAACP to recommend a Black lawyer to lead the inquest. The organization sent Larry Baraka, a 31-year-old prosecutor from Dallas. Baraka arrived in town two days after Booker’s body was found.

Limestone County had never seen anything like this. News helicopters flew into Groesbeck from Dallas and Fort Worth, landing in the church parking lot across the street from the courthouse. It was summer in Central Texas, and the courtroom, which lacked air conditioning, was crammed with 150 people; reporters filled every seat in the jury box. A writer from the Mexia Daily News wrote that the room was loaded with a “strong suspicion of intrigue, deep pathos, heavy remorse, and indignation.”

The main issue was the handcuffs. Eighteen witnesses testified, including Drummond, the probation officer. He insisted that the officers had brought just one pair of handcuffs, that only Baker and Booker were handcuffed to each other, and that the cuffs had been removed before they got into the boat. A witness who’d been on a nearby craft—a Black woman from Dallas—told the court that she saw the officers remove the restraints from two men who’d been handcuffed together. The fire chief testified that no cuffs were found on the bodies as they were pulled from the lake.

Other witnesses contradicted the officials’ version of events. Beachum, the hot-dog seller, again said that he saw cuffs taken off Baker’s body after it was retrieved from the lake, but he also admitted to drinking almost a fifth of whiskey that day. Another said all three were handcuffed—and that Elliott was drinking beer and his eyes were “puffy.” The local funeral home director, who had seen some two hundred drowning victims in his seventeen-year career, said that the position of Baker’s hands indicated that the teen had been cuffed. “It’s highly unlikely you will find a drowning victim’s hands in that position.”

At the end of the three-day proceeding, Baraka told reporters that the evidence suggested the teens were not handcuffed in the boat. He believed the officers had acted without criminal or racist intent, but he added that they had behaved with “rampant incompetence” and “gross negligence.” The boat was overloaded and there were no life preservers, so the officers could still face criminal charges.

For Mexia’s Black residents, the court of inquiry had cleared up nothing. They rejected the testimony of both Drummond and the fire chief and suspected a cover-up. Whites in Mexia also criticized the officers’ judgment. “You put a gun on someone’s hip, and it goes to their head,” former district attorney Don Caldwell told a reporter. “The evidence in this case doesn’t add up. It was a terrible act of stupidity, and somebody is going to have to pay the fiddler.”

That fall, Limestone County attorney Patrick Simmons, together with a lawyer from the state attorney general’s office named Gerald Carruth, took the court of inquiry’s findings to a grand jury. They hoped the panel would indict the officers for involuntary manslaughter, a felony. Instead, the jury came back with misdemeanor charges for criminally negligent homicide and violating the Texas Water Safety Act. If found guilty, the officers faced a maximum penalty of one year in prison and a fine of $2,000 per teen. “I could get that much for starving my dog,” said Kwesi Williams, a spokesperson for the Comanche Three Committee, an advocacy group formed in response to the drownings.

Defense attorneys argued that the officers couldn’t receive a fair trial in Mexia, so they requested the proceedings be moved. A judge in Marlin, about forty miles away, said he didn’t want it, not after “statements in the news media by certain persons created an atmosphere in this county that is charged with racial tension to the point that violence is invited.” The case was moved to San Marcos, where another judge punted. “No one wants this,” Joe Cannon, the attorney defending Drummond, told a reporter. “It’s a hot potato.” Finally, Baraka, who had by then joined the prosecution, convinced Dallas County Criminal Court judge Tom Price to preside over the trial.

If found guilty, the officers faced a maximum penalty of one year in prison and a fine of $2,000 per teen. “I could get that much for starving my dog,” said Kwesi Williams.

Price, who was eight years into a four-decade judicial career, would later call the Mexia drownings the biggest case he ever handled. “It was a hard, emotional trial,” he said. “Three young kids who died for no reason. There was so much tension, and it was so racially mixed up in there. I was thirty-three, thinking, ‘What have I got myself into?’ ”

The trial, which lasted three weeks, was perhaps the highest-profile misdemeanor proceeding in Texas history. Each defendant had his own attorney, and each attorney objected as often as possible, squabbling with prosecutors and spurring Price to threaten them all with contempt. The atmosphere was further strained by the presence of news crews, who swarmed the legal teams and the teens’ families during recesses.

To convict the officers of criminal negligence, the all-white, six-person jury would need to be convinced that under the same circumstances an ordinary person would have perceived a substantial risk of putting the teens into the boat and avoided doing so. Defense lawyers acknowledged that the officers had made mistakes but argued that their actions were reasonable—that they had needed to use the boat to avoid what they viewed as a hostile crowd. Two defense witnesses said they had seen the officers remove handcuffs from the teens before boarding the boat. Beachum, the witness who told the court of inquiry he’d seen handcuffs on Baker’s body, didn’t testify at trial because the prosecution didn’t call him to the stand. “I think Carruth, Baraka, and I all had problems with his credibility,” Simmons said recently. Instead, the prosecutors centered their case on other facts—from the absence of lights and life jackets aboard the boat to the officers’ reckless decision to overload the craft. “They made mistakes that would shock the consciences of reasonable people,” Baraka told the jurors.

The officers took the stand and said they had tried to save the teenagers. Archie told the jury that while he clung to the overturned boat, Drummond pushed Freeman toward Archie, who grabbed the thrashing teen by the hair and shirt and pulled him onto the hull. Archie said he tried to maneuver to the other side of the craft while holding Freeman across the top but the teen slipped off, sank, and then bobbed up four times before disappearing. Archie didn’t try to rescue him again because the reserve deputy wasn’t a strong swimmer. Drummond testified that he tried to help Baker but the teen kept pulling him under, so the officer let go and swam to shore. He also said that if he could have done anything to change the situation, he “wouldn’t have made an arrest in the first place.”

Elliott acknowledged that he and the other officers had erred. He called the drownings “just a horrible accident” and said he’d do things differently given another chance. When Baraka asked Elliott if he thought they deserved forgiveness, the deputy answered, “Under the circumstances, yes.”

After the closing arguments, the jury took less than five hours to render a verdict: not guilty. The defendants, showing no emotion, were rushed away. Afterward, Nellie Mae Freeman sat on a bench outside the courtroom reading the Bible. “No,” she told a reporter, “justice was not done.” Evelyn Baker, Carl’s mother, said she had expected the verdict. “This is very terrible, but that’s Mexia for you, and that’s Limestone County. The Lord will take care of them.”

The families found more disappointment when it came to their last remaining legal option: civil lawsuits, in which the deputies and the county could be held responsible for negligence under a much lower burden of proof. Each family sued for $4 million in damages, alleging that their sons’ civil rights had been violated. In December 1983, they settled for a total of $200,000, or $66,667 per teen.

A local official told the Fort Worth Star-Telegram that the county’s lawyers felt “very lucky” about the outcome. “We were just sitting on pins and needles hoping it would get as low as possible but we never really thought [the settlement] would get this low,” said Howard Smith, a county judge familiar with the civil case. Attorneys for the county made a lowball offer, and the families and their lawyers accepted it. “I was tired,” Evelyn said recently. “I was hurt, and I never did get to really grieve. They just really ran us through it.”

The pavilion at the park on April 21, 2021.Photograph by Michael Starghill

For many Black Mexia residents, Comanche Crossing was never the same after the drownings. “It just changed my whole life,” said Steen-Medlock, the teens’ schoolmate. “I never went back to another Juneteenth there.” Many others felt similarly. Attendance in 1982, the year after the drownings, was about two thousand, the lowest in 35 years. It wasn’t just that celebrants were fearful of being harassed, arrested, or worse. Comanche Crossing was sacred ground, land that had been purchased by people who had survived slavery, to ensure that they, along with future generations, would have a place to commemorate emancipation. Now that land had been defiled.

Texas had made Juneteenth an official state holiday in 1980, and celebrations of Black freedom spread to other cities. In 1982 Houston’s Juneteenth parade attracted an estimated 50,000 onlookers. As crowds moved elsewhere, attendance at Comanche Crossing’s Juneteenth ceremonies continued to decline. Arson attacks in 1987 and 1989 caused severe damage to the tabernacle and pavilion, and the structures had to be rebuilt. Concession booths were tagged with racist graffiti.

Many of those who’d grown up with the teens left town. “It was all eye-opening to our generation,” said Nemons. “This was the first thing I saw as far as being a real racial injustice. A lot of young Black folks said ‘I’m done’ and moved.” Over the years, Juneteenth crowds at Comanche Crossing dwindled even more, while the brush along the lake grew thicker and the buildings fell into disrepair. During the past decade, official attendance has sometimes dropped to less than a hundred. When the Nineteenth of June Organization elected former county commissioner William “Pete” Kirven as its new president in 2015, some locals felt optimistic. “I had a lot of hope,” said Judy Chambers, a municipal judge for the city of Mexia and a past member of the organization’s board of directors. She thought the group—and Comanche Crossing—could use some new blood.

That hope didn’t last. Although the new leadership cleaned up the park’s grounds and installed new light poles and swing sets, it also posted a sign banning alcohol, instituted a 1 a.m. closing time, and increased the law enforcement presence during Juneteenth. The new rules did not go over well. “Juneteenth is not worth going out there,” said a Mexia resident who had attended the festivities since he was a boy. “It’s not any fun. So many police you can’t enjoy yourself. I went in 2018. I didn’t like it. I haven’t been back.”

Echols, a member of the organization’s board of directors, said that despite the “No Alcohol” sign, members of the public are allowed to drink as long as they use plastic cups. He agreed that law enforcement had gone overboard in 2018 and “was scaring people away” but added that after the group expressed these concerns to the sheriff, the presence was reduced.

Simmons, the prosecuting attorney at the 1982 trial, is now the district judge for Limestone and Freestone Counties. “This was the Juneteenth place, and it’s a shame we lost that,” he said. “At the time, I looked at it as an incident that needed to be prosecuted. I look back on it now and say, ‘What a tragedy. What a shame.’ The ridiculous idea of going over—three guys in a boat—could they rethink it? It was such a tragedy, not just the loss of three young men but the whole Juneteenth.”