#I have a very different view of the framework around oppression in regards to gender than most people

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Wow, you really misunderstood the original post. Actually you've really misunderstood my whole deal.

Piss on the poor I guess.

I think your understanding of the world may be limited by youth. It's so unfortunate to see young people radicalized by online hate groups meant to push them into fundamentally right-wing frameworks that push against people's absolute right to bodily autonomy.

It is paramount to the rights of all marginalized peoples to have the right to do as they please with their own bodies.

There's a relevant quote from Huey Newton, during the gay liberation movement in the 60s and 70s, when the Black Panthers had not yet decided whether they supported gay liberation and or not, and ultimately decided to join in solidarity with both gay liberation and women's liberation for their mutual liberation:

"Some people say that [homosexuality] is the decadence of capitalism. I don't know if that is the case; I rather doubt it. But whatever the case is, we know that homosexuality is a fact that exists, and we must understand it in its purest form: that is, a person should have the freedom to use his body in whatever way he wants.”

This is fundamental to all radical frameworks, all radical and liberatory movements depend on this one thing: That people should have control over their own bodies.

While that was about homosexuality, it can be applied to all forms of bodily autonomy from abortion to medical transition. Regardless of any framework or theory around it (on which I disagree with many theorists), transness is a fact that exists, and it is paramount above all else, that people have the freedom to use their own bodies however they want, and modify them as they please. In ways that allow them to live comfortably in their bodies.

Regardless of your views on the matter, trans people exist. And they have very little to do with you. Your panic over them is the result of a larger cultural moral panic meant to divide revolutionary movements and shift people like you further right, into right-wing gender fundamentalist beliefs. It happens slowly. But you'll notice it happening. I see posts about it on radfem tags all the time. "I had to unfollow my friend because she said she's voting for Trump. How could she do that? Vote for a man, a rapist just because he doesn't support trans rights?" It happens constantly, persistently. Because it's an ideology designed to radicalize people by utilizing scapegoating against a tiny minority who are, I will grant you, often annoying and cringe. But by the time you begin to notice it, your own internal overton window has already been pushed to the right. You've already begun to think maybe there should be limits on people's bodily autonomy. Maybe the government should be more authoritarian towards people's bodies and their medical decisions.

At which point you have already lost all semblance of being a feminist, or a radical. You've become easily controlled, and willing to vote against your own autonomy, just to spite the people you hate. You are for limiting people's rights to control their own bodies and medical care. Something that can and will be used against your bodily autonomy, and already is. Regardless of if you think the gendered framework around medical transition is accurate, medical transition is a form of healthcare many people need in order to survive, thrive, et cetera. And it is a bodily autonomy issue. And for me, an existential one.

I have a rare disorder of sexual development and don't produce sex hormones, I require hrt. Because I'm technically female, at least on paper, doctors do not want to give me testosterone, even though most cis women have more testosterone in their bodies than estrogen naturally and need it to function properly. I am told I don't need it, because of this framework that women only have estrogen. This is medical misogyny. Now I access TRT through a gender clinic, because they are willing to let me choose what to do with my own body. Informed consent gender clinics are willing to let me decide the exact balance of hormones I want in my body based on what works for me, not based on essentialist ideas of what a female body should be, projected onto me, a freak. This has been a miracle for me. Literally life-saving medical care.

Trans people deserve access to their medical care, but even if you are so far gone that you can't see their humanity and right to self-determination behind your ideology, by advocating against their rights, you are also harming me. And while I am happy to fight for the rights of my perisex trans comrades, and anyone else who needs HRT and believe absolutely in their existence and right to self-determination, the ideology of your ilk is also an existential threat to me and people like me, and I would prefer to exist. At least I do since I started testosterone and finally developed a will to live.

So again, in conclusion, your ideology advocates for my eradication. So it is preferable to my continued existence if yours ceases.

Constantly citing this article and the studies it uses.

Here's a quote:

"That study shows that transmasculine individuals were actually more likely to be victims of childhood sexual assault, adult sexual assault, dating violence, domestic violence, and stalking than were transfeminine individuals (as shown in the chart below).

The only category in which trans women were more likely to be victimized was by hate violence, and even there the difference was small: 30 percent of trans women reported having experienced hate violence, compared to 29 percent of trans men."

#trans#trans rights#intersex rights#intersex#bodily autonomy#I have a very different view of the framework around oppression in regards to gender than most people#most of those in the “gender studies” space are perisex#that is not their fault we are all born in our bodies#but from the perspective of a freak their ideology is off by orders of magnitude#as is yours#but at least theirs supports bodily autonomy#and enables it for people like me#yours does not

640 notes

·

View notes

Text

So I read that lame genderkoolaid post and a few by other prominent transunity bloggers, specifically in regards to their ideas regarding the existence of misandry and the framework they've developed in order to describe transphobia. The system, which I don't believe they've actually coined despite loving to make new words, which I will call multisexism.

Multisexism is the idea that sexism is a multivector space containing several "sexisms". There are three main sexism I've seen them identify (misogyny, misandry, and misandrogyny [nbphobia {also Miss Androgyny is a killer drag name}]). Some other sexisms I've seen them identify are a sexism against multigender people and a sexism against intersex people. Since this framework is built around identifying sexisms I would posit there is room for them to add a few more. A possible add would be a modified misandrogyny that specifically targets xenogenders.

From this multisexism space, transunionists argue that transphobia (and gender based oppression as a whole) is a cross product of multiple sexisms, usually a unique cross product for every given person based on how much that person **personally** identifies with experiencing a certain type of sexism.

In this line, transmisogyny and transmisandry become catchall terms for the sexism cross-products experienced by people that identify as transfem or transmasc. This an important distinction since they do not view each person as experiencing the same cross product. Thus transmisogyny and transmisandry are not concrete terms describing a system of oppression but a vague term referring to the many ways a individual people experience bigotry.

I believe this is the core reason behind why they get into so many fights with so-called serano-esque transfeminists.

Multisexism is a very obviously flawed framework of oppression for the simple reason that it is unable to identify benefactors of their various sexisms. Some of them are lifted wholesale from existing oppression frameworks (misogyny, exorsexism) and as a result some of the ways they talk about oppression have made their way into their critiques as well. One good example of this is the term patriarchy. Despite multisexism not being able to identify an oppressor class, they still call the general concept of sex based oppression "patriarchy" even though they make absurd claims like "men suffer under the patriarchy". I wouldn't be surprised if they soon remove patriarchy from their vocabulary and swap it for something else.

Traditional oppression frameworks posit that oppression exists because the oppressor class benefits from the subjugation of the oppressed class. Since multisexism lacks an oppressor class we can conclude that they believe sexism exists because different sexes exist. This explains why they create a sexism for every perceived "sex": male, female, sexless, multisex, intersex. A list which maps roughly with western gender theory, but with intersex thrown in.

One the bigger reasons I said multisexism as ideology is flawed is because it does not present an endgame. Since there is no oppressor class to dismantle, no patriarchy to fight save the specter of bigotry, there is no way given within the framework of multisexism to **end** sexism.

On a similar note, it does not offer an explanation for why sex exists. Since there is no oppressor sex, transunionists are unable to say why the boundaries of the sexes were constructed. Even if they say or believe sex does not exist they only do so because the feminist theory they used as a partial basis says so as well. In this regard, transunity is bioessentialist in that is believes sex is real and inherent, except that they add new sexisms whenever they feel the need to classify a new one.

Why exactly do tranunionists believe they need to have this framework then? Transmisandry is not a new concept, I can find posts from at least as early 2013 making the same points about its existence and complaining that transfems talking about transmisogyny and how AFAB trans people perpetuate it in trans spaces.

Taking them as face value for their own claims on why multisexism must exist, it is because they needed a framework within which it is possible to account for how cis people view trans people as their AGAB.

"ive seen trans men (often those who harass other transmascs in the name of "transfem allyship") insist that trans men cant be subject to misogyny because we're men and to say otherwise is misgendering. and like im sorry but we cannot do meaningful anti-transphobic activism if we are shaping our view of transphobia on "never ever ever implying that anyone sees trans people as anything but the gender they say they are & that that might shape the kind of transphobia they face" like thats just. not realistic." - genderkoolaid

I actually agree with this sentiment (genderkoolaid's asides, well, aside), and I believe most other transfeminists also do. I believe that AGAB is important when discussing transphobia and acknowledging that is not misgendering. In seems odder to me that genderkoolaid would agree with this sentiment since it is the basis of the terms TME/TMA, a framework ey and other transunionists despise.

Assuming this was the only reason to create the multisexism framework, it would be quite easy to dismiss it. Taking a materialist feminist approach and treating sex based oppression as a dialectic is far more capable of handling AGAB's effects on transphobia without having to say things like "trans men experience misogyny because they are seen as women."

This is because a dialectic view of sex based oppression allows us to talk about men and women as classes because there is an understanding that they do not exist except in opposition to each other. Thus saying things like "women's clothing doesn't have pockets" does not misgender AFAB enbies who may also wear clothing without pockets instead of the ludicrous statement "AFAB clothing doesn't have pockets." (Real example btw)

This also allows us to explain oppression through the interaction of the classes of men and women. Misogyny is the way through which men (as a class) are privileged over women (as a class). Exorsexism is the way through which people who do not neatly fit into these constructed classes are forcibly pushed into them. Transphobia is the way in which dissonance between a person and their class is punished.

In one paragraph a dialectic analysis of sex based oppression does more to explain why its various forms exist then multisexism and the transunionists ever will. [As an aside, any toxic masculinity or other supposed harms men face from patriarchy according to MRAs is really just transphobia or, as we shall see, transmisogyny.]

Something ironic is that sexist men have an inherent understanding of this. I once saw an instagram reel wherein the joke "There's 76 genders? Wooohoooo, that means there's now 75 genders men are better than!" was made, showing a better understanding of the dynamics of misogyny (and transmisogyny for that matter) than I've ever seen from a transunionist even if the person in question though the framework was a good one.

We can also use this dialectic framework to analyze and justify why transmisogyny is a separate oppressive axis with distinct benefactor classes.

When we look at the transphobia nonbinary people and transmascs face, largely it is a matter of forcing the individual into one of the two classes: Men™ and Women™. This can be seen from the way TERFs will attempt to make transmascs detransition.

Another insight we can make is about the treatment of AFAB enbies vs AMAB enbies. Since Women™ are an oppressed class, the barrier to entry, so to speak, is lower. This can be seen from the way that Women™ are largely allowed under patriarchy to do things that Men™ do (even if they are seen as inherently inferior) but that Men™ are disbarred from doing things that Women™ do, to the point where if enough Men™ do it, it becomes a Male Thing ie. programming. Of course, that isn't to say that there aren't some misogynists who still thing women shouldn't wear pants, they are not a majority opinion. In fact, most feminist gains have been in expanding Woman™ roles rather than in deconstructing the class dynamic altogether. Something that can only be done by transfeminism since only it focuses on destroying both classes.

Bit of a detour, but the point I was making wrt AFAB enbies was that for a lot of people, it is easier to stomach a Woman™ that is gender non-conforming (in the right ways) than a Man™ who is gender non-conforming (in any way). The generalized form of this is that Women™ are allowed to participate in roles that are for Men™, but neither Men™ nor Women™ are allowed to reject the roles they are given. This can be applied to several other aspects such as why a lesbian rejecting attraction to men is seen as a more offensive statement than saying they are attracted to women. [Hint: its because attraction to women is a thing Men™ do so Women™ are allowed to do it more often they than they are allowed to deny their own role as a Woman™, which is to be attracted to men]

There's much more to be said on the topic, especially wrt how transmascs are treated as Women™ until they pass and can be treated as Men™, which honestly describes a good 90% of so called transmisandry. But! I want to talk about transmisogyny.

Julia Serano posited that there is in fact a third class in sex based oppression, that of the Transvestite™. One of the biggest indicators that this class exists is that trans women are considered neither Men™ nor Women™ once they have transitioned, or even once they have articulated that they are women. This is something that other trans people do not experience. Examples for which can be seen in the oft-debated femboy, and the treatment of AFAB trans people.

Another big indicator can be found in some of the posts by transunionists arguing that transmisogyny can be experiences by anyone. Why is it there there are dozens of posts about non-trans women getting mistaken for trans women and facing violence, but none about non-trans men getting mistaken for trans men and facing violence? It is a strong argument for the existence of the Transvestite™ class.

Serano, has said for more than I could fit here so I will leave it at that and refer you to literally any literature on transfeminism.

Anyways, I think that is more than enough to prove that a dialectical feminism is far more useful for analysis than multisexism. Why then, do transunionists use it? Because it removes accountability for men.

If there is no benefactor class, then there is no real reason to analyze of deconstruct behaviors that benefit them. Thus the only reason transunity exists as an ideology is to disenfranchise trans women. There is no other way to explain their ideological foundations.

#transmisogyny#super long post#@marxists please dont grill me on getting dialectic wrong 😭😭😭#I'm trying my best here#I was just super mad at transunionists and wanted to write out my thoughts

174 notes

·

View notes

Text

Blog #1 Revised

The article Settler Colonialism as a Structure by Evelyn Nakano Glenn highlights the argument that settler projects worked in parallel to the societal structuring of race, gender, and sexual relations. The key term here is settler colonialism, which aims to eliminate and alienate Indigenous peoples. This term is critical for applying the settler colonialism framework, as the differences from classical colonialism have very different implications for race formation. Two key differences include the intention to stay permanently and confrontations with Indigenous peoples. This framework serves as a theoretical foundation for race and race formation, CRT, type of violence(Direct, structural or cultural violence. This means that race, gender, and sexual relations were directly, whether unintentional or not, founded and shaped by the specific goals and how they were obtained from colonization. The reason Glenn categorizes settler colonialism as an ongoing structure is because of the continued effect it has had on relationships between races. While it may have been an event in time, its effects have never gone away or stagnated, only evolved. One of the main characteristics of settler colonialism is its deviation of aim from classic colonialism. The latter aims to acquire resources to support the “metropole,” i.e., the parent state, whereas the former’s goal is to acquire land with the intention to settle permanently. Thus, the treatment of ingenious looks a bit different. Unlike classic colonialism, settler colonialism aims to eliminate Indigenous peoples, which aims to use them as human resources. Given this, racism and oppression will not look the same across the board, much less across races, and the author attests that racism is not comparable through analogies or specific events. The effect of the slave trade is much different from the erasure of Native Americans, yet both are cases of political and economic exploitation.

The second piece of media assigned was Critical Race Theory: An Introduction. Critical race theory was created as a tool to allow us to understand oppression and enslavement and, in turn, criticize it. It is described as a movement in which scholars and activists alike aim to “study and transform the relationship among race, racism, and power.” It does so by questioning the foundational ideas of liberalization and analyzing the social, economic, and legal structure. The idea that it is not the structures that create racism but the inverse, our institutions are instead built up around racism and white superiority, is a principal foundation of this theory. Racism is considered the norm; it is the way it is apparent in every fiber of society and accepted, even if the intention is not rooted in racist ideology. More to the point, it supports the second tenet of CRT, named material determinism, which I find to be one of the most important. It holds that racism serves to benefit the white elite and the white working-class. The incentive to change is absent, on both a political and cultural level, since the interests of white people are met through racism.

When posed with the question, “if racism was cured, would life very much improve for people of color?” Critical race theory thinkers divide up into three categories. I also find these to be important key terms for different trains of thought in reference to this framework. First are the idealists who believe that racism and discrimination are immaterial matters - they stem from thinking, mental categorization, attitude, and discourse. The meaning and symbols of race relations can be shifted and changed through thinking and attitude.

In contrast to the realists, they hold a much more material point of view regarding racism; it is not only thinking/attitudes but how society hierarchically allocates privilege and status. Lastly, we have materialists who require us to look at specific conditions throughout history, such as the rationalization of treatment and exploitation of one group over the other. All these differing analysis camps aid us in effectively using CRT to understand and criticize racism, and more specifically, what each one emphasizes in answering that initial question. It is best to blend the material and cultural forces behind the formation and continued oppression for a more holistic understanding of race as a structure when tackling race reform.

0 notes

Photo

Insurgent Supremacists – a new book about the U.S. far right By Matthew N Lyons | Sunday, April 01, 2018

My book Insurgent Supremacists: The U.S. Far Right’s Challenge to State and Empire is due out this May and is being published jointly by Kersplebedeb Publishing and PM Press. It draws on work that I’ve been doing over the past 10-15 years but also includes a lot of new material. In this post I want to highlight some of what’s distinctive about this book and how it relates to the three way fight approach to radical antifascism. I’ll focus here on three themes that run throughout the book: 1. Disloyalty to the state is a key dividing line within the U.S. right. For purposes of this book, I define the U.S. far right not in terms of a specific ideology, but rather as those political forces that (a) regard human inequality as natural, inevitable, or desirable and (b) reject the legitimacy of the established political system. That includes white nationalists who advocate replacing the United States with one or more racially defined “ethno-states.” But it also includes the hardline wing of the Christian right, which wants to replace secular forms of government with a full-blown theocracy; Patriot movement activists who reject the federal government’s legitimacy based on conspiracy theories and a kind of militant libertarianism; and some smaller ideological currents. Insurgent Supremacists argues that the modern far right defined in these terms has only emerged in the United States over the past half century, as a result of social and political upheavals associated with the 1960s, and that it represents a shift away from the right’s traditional role as defenders of the established order. The book explores how the various far right currents have developed and how they have interacted with each other and with the larger political landscape. I chose to frame the book in terms of “far right” rather than “fascism” for a couple of reasons. Discussions of fascism tend to get bogged down in definitional debates, because people have very strong—and very divided—opinions about what fascism means and what it includes. Insurgent Supremacists includes in-depth discussions of fascism as a theoretical and historical concept, but that’s not the book’s focus or overall framework. As a related point, most discussions of fascism focus on white nationalist forces and tend to exclude or ignore other right-wing currents such as Christian rightist forces, and I think it’s important to look at these different forces in relation to each other. For example, critics of the Patriot/militia movement often argue that its hostility to the federal government was derived from Posse Comitatus, a white supremacist and antisemitic organization that played a big role in the U.S. far right in the 1980s. That’s an important part of the story, but Patriot groups were also deeply influenced by hardline Christian rightists, who (quite independently from white nationalists) had for years been urging people to arm themselves and form militias to resist federal tyranny. We rarely hear about that. 2. The far right is ideologically complex and dynamic and belies common stereotypes. Many critics of the far right tend to assume that its ideology doesn’t amount to much more than crude bigotry, and if we identify a group as “Nazi” or as white supremacist, male supremacist, etc., that’s pretty much all we need to know. This is a dangerous assumption that doesn’t explain why far right groups are periodically able to mobilize significant support and wield influence far beyond their numbers. Yes, the far right has its share of stupid bigots, but unfortunately it also has its share of smart, creative people. We need to take far rightists’ beliefs and strategies seriously, study their internal debates, and look at how they’ve learned from past mistakes. Otherwise we’ll be fighting 21st-century battles with 1930s weapons. For example: because of the history of fascism in the 1930s and 40s, we tend to identify far right politics with glorification of the strong state and highly centralized political organizations. Some far rightists, such as the Lyndon LaRouche network, still hold to that approach, but most of them have actually abandoned it in favor of various kinds of political decentralism, from neonazis who call for “leaderless resistance” and want to carve regional white homelands out of the United States to “sovereign citizens” and county supremacists, from self-described National-Anarchists to Christian Reconstructionists who advocate a theocracy based on small-scale institutions such as local government, churches, and individual families. One of the lessons here is that opposing centralized authority isn’t necessarily liberatory at all, because repression and oppression can operate on a small scale just as well as on a large scale. This shift to political decentralism isn’t just empty rhetoric; it’s a genuine transformation of far right politics. I think it should be examined in relation to larger cultural, political, and economic developments, such as the global restructuring of industrial production and the wholesale privatization of governmental functions in the U.S. and elsewhere. We need to take far rightists’ beliefs and strategies seriously, study their internal debates, and look at how they’ve learned from past mistakes. Otherwise we’ll be fighting 21st-century battles with 1930s weapons. As another example of oversimplifying far right politics, it’s standard to describe far rightists as promoting heterosexual male dominance. While that’s certainly true in broad terms, it doesn’t really tell us very much. Insurgent Supremacists maps out several distinct forms of far right politics regarding gender and sexual identity and looks at how those have played out over time within the far right’s various branches. Most far rightists vilify homosexuality, but sections of the alt-right have advocated some degree of respect for male homosexuality, based on a kind of idealized male bonding among warriors, an approach that actually has deep roots in fascist political culture. In recent years the alt-right has promoted some of the most vicious misogyny and declared that women have no legitimate political role. But when the alt-right got started around 2010, it included men who argued that sexism and sexual harassment of women were weakening the movement by alienating half of its potential support base. This view echoed the quasi-feminist positions that several neonazi groups had been taking since the 1980s, such as the idea that Jews promoted women’s oppression as part of their effort to divide and subjugate the Aryan race. This may sound bizarre, but it’s a prime example of the far right’s capacity time and again to appropriate elements of leftist politics and harness them to its own supremacist agenda. 3. Fighting the far right and working to overthrow established systems of power are distinct but interconnected struggles. A third core element that sets Insurgent Supremacists apart is three way fight politics: the idea that the existing socio-economic-political order and the far right represent different kinds of threats—interconnected but distinct—and that the left needs to combat both of them. This challenges the assumption, recurrent among many leftists, that the far right is either unimportant or a ruling-class tool, and that it basically just wants to impose a more extreme version of the status quo. But three way fight politics also challenges the common liberal view that in the face of a rising far right threat we need to “defend democracy” and subordinate systemic change to a broad-based antifascism. Among other huge problems with this approach, if leftists throw our support behind the existing order we play directly into the hands of the far right, because we allow them to present themselves as the only real oppositional force, the only ones committed to real change. Insurgent Supremacists applies three way fight analysis in various ways. There’s a chapter on misuses of the charge of fascism since the 1930s, which looks at how some leftists and liberals have misapplied the fascist label either to authoritarian conservatism (such as McCarthyism or the George W. Bush administration) or to the existing political system as a whole. There’s a chapter about the far right’s relationship with Donald Trump—both his presidential campaign and his administration—which explores the complex and shifting interactions between rightist currents that want to overthrow or secede from the United States and rightist currents that don’t. During the campaign, most alt-rightists enthusiastically supported Trump not only for his attacks on immigrants and Muslims but also because he made establishment conservatives look like fools. But since the inauguration they’ve been deeply alienated by many of his policies, which largely follow a conservative script. Three way fight analysis also informs the book’s discussion of federal security forces’ changing relationships with right-wing vigilantes and paramilitary groups. These relations have run the gamut from active support for right-wing violence (most notoriously in Greensboro in 1979, when white supremacists gunned down communist anti-Klan protesters) to active suppression (as in 1984-88, when the FBI and other agencies arrested or shot members of half a dozen underground groups). This complex history belies arguments that we should look to the federal government to protect us against the far right, as well as simplistic claims that “the cops and the Klan go hand in hand.” Forces of the state may choose to co-opt right-wing paramilitaries or crack down on them, depending on the particular circumstances and what seems most useful to help them maintain social control. Insurgent Supremacists isn’t intended to be a comprehensive study of the U.S. far right. Rather, it’s an attempt to offer some fresh ideas about what these dangerous forces stand for, where they come from, and what roles they play in the larger political arena. Not just to help us understand them, but so we can fight them more effectively.

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

Part II: Disability Right Movement

Role of Psychology

Crethar and Ratts (2008) define social justice as a multidimensional methodology in which mental health providers attempt to concurrently encourage personal growth and the mutually decent through speak to obstacles correlated to both individual and distributive justice. The counselor or psychologist empowers the client or group to stand up for their beliefs in a healthy manner. Crethar and Ratts (2008) suggest that when they entrust their client, they base the empower around four principles: equity, access, participation, and harmony. Equity is the appropriate dissemination of resources. The Key is the everyone has access to these resources. Participation is that everyone is part of the decision-making process. Lastly, harmony is the best possible outcome for the community.

Kinderman (2013) states that psychologists should speak out against social injustices. Psychologists study human behavior, which makes them a great way to speak out for the injustices in the world. Social change primarily comes from groups and leaders (Louis, Mavor, La Macchia, & Amiot, 2014). Leadership is in a position of power to change injustice in a group quickly; however, some are unwilling to step up and be the voice for change. For the psychologist, social change could go against their code of ethics. Lack of leadership would pose a dilemma for the psychologist to choose between belief or principle of ethics. Kinderman (2013) suggest that psychologist should help other understand human behavior to shape social change.

Ethnic Inequalities on the Psychological Well-Being

People with disabilities are more likely to have lower education, low socioeconomic status, and be unemployed. Psychological well-being is already common in most cases when someone has a disability. According to Chang et al. (2014), disability was one of two factors responsible for depression rates. A person with either suffers from a mental or physical disability is at a higher risk for depression. A disabled person could be discriminated against because of limited resources. Resources may be diverted away from a person with a disability because they are considered to have a reduced quality of life and toward a person with a so-called better chance of having a good quality of life.

Analysis of any Concerns Regarding Ethnic Inequality

Disability can also affect a person’s relationships. According to Wasserman (2016), people that are married are generally happier than unmarried people. Disability can make it difficult for a person to find friendship or love. The disability is seen as creating an awkward degree of inequality and difference. Wasserman (2016) suggests that non-disabled people could think a relationship with a disabled person might be unfulfilling. Relationships are complicated for most people without disabilities. Relationships are viewed as more complex with people with disabilities because of society’s view on people with disabilities. Relationships are only one aspect of inequality that people with a disability experience. They also experience inequality in education, health care, and employment. People with disabilities understand their limitations and will not apply for the job they cannot perform. Some non-disabled people will judge a person by their disability instead of focusing on their qualifications. Society needs to focus on the person in front of us instead of the disability. Lastly, we can recognize a person’s limitations but understand they are far more capable than their disability.

Analysis of the Role of Psychology

Social psychology is a way to tie the individual to social change; however, social psychology is usually based on how individuals view others. Psychology has not had much influence on social change. Historical sociologists have been the first for social change. According to De la Sablonnière (2017), over 70 years ago, social change came up in psychological literature; however, only a few psychologists have to take on social change. Intersectionality is obtaining arise in consideration in psychology. The theory or framework comes from the work of Black feminist scholar-activists and its emphasis on interlocking systems of oppression and the necessity to effort regarding structural-level alterations to stimulate social justice and impartiality (Rosenthal, 2016). Modern curiosity in intersectionality in psychology gives a chance to lure mental health providers’ devotion to structural-level problems and make public integrity and fairness more crucial in psychology (Rosenthal, 2016). Psychologists have learned many subjects of social justice such as prejudice, discrimination, conformity, and numerous subfields around these matters in psychology. The American Psychological Association (2017) code of ethics needs psychologists to uphold all society’s rights, regardless of the stage of life, sex, gender identity, race, background, national origin, belief, sexual orientation, disability, language, or financial status. The code pushes psychologists to become mindful of these features and circumvent bias and unwarranted practices. Hays et al. (2010) suggest that group work is a way to assist in empowering clients at an individual and systemic level. Hays et al. (2010) believe in increasing attention to social justice problems using education, training, supervision, practice, and research. Promoting change within a group could help shed light on the oppression or discrimination of people with disabilities. Psychology could empower people to stand up for equal rights to promote positive change.

An explanation of the relevance of this topic to the field of psychology and the role and responsibilities of psychology concerning the issue

Individuals with a disability have experienced some shame in the world. Non-disabled people are unsure of how to handle a person’s physical or mental impairment. Psychology explore the data about physical or psychological impairment and way to treat the impairment. The field of psychology’s responsibilities should be to support and discover where the hitches are and try to shed light on the issue with the group, legislature, and community to increase the quality of life for those with disabilities.

The American Psychological Association (2013) defines clinical psychology as “a clinical discipline that involves the provision of diagnostic, assessment, treatment plan, treatment, prevention, and consultative services to patients of the emergency room, inpatient units, and clinics of hospitals.” The American Psychological Association (2013) says Clinical psychology combines “science, theory, and practice to understand, forecast and alleviate maladjustment, disabilities, and discomfort as well as to promote human adaptation, adjustment, and personal development.” Psychology concentrates on the intellectual, emotional, biological, psychological, social, and behavioral characteristics of a human role in diverse societies and at all socioeconomic levels.

Publishing Site and Reasoning

For this blog, I am choosing to launch it on the blog site Tumblr. Tumblr is a place where people of different backgrounds and points of view can express themselves, discover themselves, and find new perspectives. It is where your interests connect you with your people. This platform is very user-friendly and has been available since 2007. Using Tumblr, I can reach academics that are casually looking for more psychology-related content and a younger audience that may find comfort in reading information on disabilities and ways social change can be implemented for this social problem. Tumblr is an excellent platform to help facilitate an academic conversation because Tumblr is easily accessible and can be seen from any smart device.

References

American Psychological Association. (2017). Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/ethics/code/

American Psychological Association. (2013). Guidelines for psychological practice in health care delivery systems. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/pubs/journals/features/deliverysystems.pdf

Chang, T. E., Weiss, A. P., Marques, L., Baer, L., Vogeli, C., Trinh, N. T., … Yeung, A. S. (2014). Race/Ethnicity and Other Social Determinants of Psychological Well-being and Functioning in Mental Health Clinics. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 25(3), 1418-1431. doi:10.1353/hpu.2014.0138

Crethar, H. C., & Ratts, M. J. (2008). Why social justice is a counseling concern. Counseling Today. Retrieved from https://www.txca.org/images/tca/Template/TXCSJ/Why_social_justice_is_a_counseling _concern.pdf

De la Sablonnière, R. (2017). Toward a Psychology of Social Change: A Typology of Social Change. Frontiers in Psychology, 8. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00397

Hays, D. G., Arredondo, P., Gladding, S. T., & Toporek, R. L. (2010). Integrating Social Justice in Group Work: The Next Decade. The Journal for Specialists in Group Work, 35(2), 177-206. doi:10.1080/01933921003706022

Kinderman, P. (2013). The role of the psychologist in social change. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 60(4), 403-405. doi:10.1177/0020764013491741

Louis, W. R., Mavor, K. I., La Macchia, S. T., & Amiot, C. E. (2014). Social justice and psychology: What is, and what should be. Journal of Theoretical and Philosophical Psychology, 34(1), 14-27. doi:10.1037/a0033033

Rosenthal, L. (2016). Incorporating intersectionality into psychology: An opportunity to promote social justice and equity. American Psychologist, 71(6), 474-485.

Wasserman, D. (2016). Disability: Health, Well-Being, and Personal Relationships (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy). Retrieved from https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/disability-health/

0 notes

Text

regarding definitions of sex and gender

CW: Sexual assault, misgendering, TERF talking points, simplified interpretations of third gender/nonbinary/transmasculine individuals etc.

In response to claims of circularity and lack of clarity with regards to the definition of self-identified genders, I wanted to try to clear up definitions.

Let us first consider sex, and let us disregard fundamental fuzziness in defining any concept. For organisms that reproduce sexually in a binary form, there are subsets which all (mostly) can produce offspring with those of the opposite subset. This corresponds often to sex-determination genetic or environmental markers, and to specialized anatomy. Leaving aside all sorts of exceptions and corner cases, we can consider it in principle knowable for an individual human being whether or not they belong to a male mating type/reproductive sex, or a female mating type/reproductive sex. Leaving, again, exceptions aside. This specifically refers then to whether gametes from the one can work to fertilize gametes from the other in a spontaneous setting.

Under real-life circumstances animals cannot sequence each others' genomes very often. Assessing whether mating with another can produce offspring therefore becomes usually-efficient guesswork, helped by phenotypic properties - secondary sexual characteristics - which tend to associate with the primary sexual characteristics implementing the mating type. Historically, telling this apart, and various strategies expanding outwards around that, has been a big deal for survival, so all sorts of culture and behaviour and perception of meaning - some of which having neural underpinnings, making for a form of invisible secondary sexual characteristics - have evolved, genetically to some extent, but primarily memetically (and with more and more such encoding likely migrated from genome to memeplexes as cultural memetic carrying capacity expanded).

We can refer to gender as the social construct surrounding sex (with sex referring to many different forms of bimodally distributed biological properties in a species - chromosomal or reproductive anatomy or secondary sexual characteristic sex, but here left primarily referring to mating type). Humans tend to divide other humans based on which mating type they believe them to have, in their perceptions and representations of the world, in their language, in their organizing of social circles and group activities, and in how they come to feel about each other, and what associations they will place upon each other, and what they will expect from each other.

Essentially all of these divisions are describable as mental or social activities undertaken by humans; the division always has a divider executing it, sometimes consciously, usually unconsciously and by habit. This is what it means that the divisions themselves are social constructs. The divider is every human being all the time. The specifics of the division will differ between individuals, between cultures, and across history. The specifics of how it is done have been shown to differ some based on biological properties of the divider - specifically, the tendency of any one person to place themselves into the construct according to their mating type/reproductive sex or not (either not at all or as the other mating type/reproductive sex) is somewhat predictable based on features impacting neurology (genetics and hormonal exposure). This suggests that the social construct of gender is not merely something which was invented de novo, like the social constructs of money or flags of countries, but which has specialized neural underpinnings. Many human beings are primed to learn how to divide in this manner, and will experience some instincts towards doing so.

To then first address claims of circularity: gender as a social construct thus has a definition which ties into the somewhat less complex concept of reproductive sex. The process of dividing by gender is largely one of trying to infer reproductive sex (though it does not always have to be so, as stated below), and labels and associations of gender are mostly inherited from those of reproductive sex. However, reproductive sex is a state of anatomy, whereas gender is an ongoing set of actions and emotions and thoughts and perceptions - it is a social construct. The concern would be situations of "I identify as X. What is X? X is that which I identify as." But the social construct is not reducible to the category it results in, it rather consists of the process of establishing that category.

This process then draws on the external labels and properties of reproductive sex to inform the construction of gender, and does involve a division which mostly will place individuals having a certain reproductive sex into the gendered division group with the same label, where most other such individuals probably but not necessarily also will be found. However, if the process also considers other features, this result is not guaranteed, and this still poses no challenge for the consistent definition of the social construct of gender as a set of divisive processes building on top of and drawing labels from reproductive sex. Gendering is an activity, not in itself the same as its resulting category, nor is it the same as any statement about any property of that category. It is true then that we have a hard time writing a concise dictionary definition of gender without using qualifiers to link it to a time and a place and one or more sets of people. But the same essentially holds true for concepts like "religion" or "justice" or "nationalism" or "value", concepts which likewise play important roles in our lives sometimes because they remain despite our best efforts to the contrary. These things too we can only define through fairly complex schemes which sometimes may appear circular at first glance, whereas in fact they rather refer to sometimes large sets of historical and ongoing practices and exemplars. This is no argument against the validity or utility of gender as defined here.

(I do not think gender as a social construct will ever evolve so that it loses touch with reproductive sex entirely, on a statistical level. But if it did, yet still remained the anchoring point for the instincts and emotions which underlie conditions like gender dysphoria, and for oppressive practices like sexism, then nothing useful would have been lost, and we would still have available the necessary starting point to work to improve situations with regards to those conditions and practices. Were it not for the fact that it is reproduced regardless of our views on the matter, we ought to have discarded as useless long ago anything which essentially is a classifier for reproductive sex, so it does not matter if gender is made a less accurate such classifier.)

(There is one other nominal aspect here worth mentioning. I am saying here that gender is a particular process and activity of dividing humans, mostly drawing back onto reproductive sex, in how we think, feel, speak and act with regards to them. This the meaning of gender as a concept. One can also use the word to refer to the "gender of a person"; this would refer to the label resulting from that process, in the context of a particular person or collective carrying out the division, and a particular person being placed. As an example: If in the schoolyard, teacher A says to child B, "go play with the other girls over there!", pointing to C, D and E climbing rocks, then the gender of B (and C, D and E) in the framework of A at this point, is female. A is probably assuming, or at least considers the possibility salient, that B will produce human eggs some day, as well as most likely expecting a number of other ways in which B, C, D and E should have more in common with each other than with F, G and H playing over by the swings. So yes, we can also speak of the gender of a person in this regard, and it will refer to a particular label resulting from a particular gender construction process. Or if K says, "I am lesbian", she is referencing gender assignment such that any partner X of hers, will have to have been assigned a female label by her own process of constructing gender, as she herself has. Whether or not X must also have ovaries as an implication of this, or whether K herself must, will then depend on the specifics by which K divides humans into genders.)

Thus, gender can be the placement of an individual across divisions made on the basis of beliefs about mating type. However, despite the neural underpinnings, as a social construct, the framework of dividing by gender is malleable, which has also been shown experimentally. On one hand, we can unlink peripheral properties from gender by taking them out of the division. This is vast, ongoing work undertaken by feminists, including myself. We can and should prune down the divisive structure as far as we can, removing gendered stereotypes and unfair expectations. This is the most crucial political issue in the history of the world (to my mind, even more important than that of capitalism or racism, both of which also are more important).

However, beyond that unlinking of peripheral associations with gender, we do eventually come to points where further unlinking is difficult, may take much more time, or may require biological engineering in itself. Among others, beyond having a prepared learning capacity to divide into genders based on beliefs about mating type (and in this division process, be inclined to make use of information such as the statements of others as well as secondary sexual characteristics), most humans may have a prepared learning capacity to prefer and be motivated to act in line with placement of themselves along the side of a division, based on a feeling of positive-emotional sameness with those surrounding other humans placed on that side. While this is by no means anywhere near absolute or universal, it may mean a tendency to seek out same-gender (and thereby same mating type) interactions, as seen often in young children growing up. This would be expected as one mechanism by which gender role behaviour would be taught more easily, thus providing indirect genetic support for memetic inheritance.

That is, I postulate that to some extent, humans will divide (i.e. gender) each other, compare themselves with the resulting groups, and seek to place themselves with the one group rather than the other throughout the process of collective gender divisions. There is an instinct in most humans to polarize themselves in the context of gender divisions at all levels. It may not be strong and is by no way the main driver behind the construction of society, and may not be as visible in adulthood when many more social constructs have come online (though by then it may have deposited itself through gender roles). In most people it is rarely recognized. Most people further seek to polarize throughout gender divisions so that they group with those who have the same reproductive sex/mating type (they are cisgender). Likely some of this need-for-sameness underlies some of body dysphorias experienced by cis individuals when their body is atypical for their reproductive sex with regards to some secondary sexual characteristic; there may exist a drive towards being the same in these regards as the rest of one's side of the gender division, when compared to those on the other side.

In some people, well-documented throughout history and different cultures (constituting perhaps 0.5%-2% of the population?), and with a number of hormonal and neural correlates weakly predicting this state, suggesting complex sex-atypical differentiation, the instinct to polarize oneself in the context of gender divisions is not aligned with reproductive sex. When dividing in their mind and actions people into genders, based on beliefs about their reproductive sex (informed by the statements of others, and informed by secondary sexual characteristics), these individuals will create the same divisions, but will experience an instinct to polarize themselves not so that they group with others having the same reproductive sex, but with those having the opposite reproductive sex (they are binary transgender) or along a more complex pattern (they are nonbinary transgender). This is not the same as not caring about the divisions (that is, being agender). This is instinctually caring about the division, just as most cisgender individuals do, but having an instinct to polarize with a group that does not actually match one's reproductive sex (and as such, usually not one's genetics, anatomy, secondary sexual characteristics, history of being placed along gender divisions by others...). This caring about the outcome of the gender division process, in the sense of having an instinctual preference with regards to one's own polarization into gendered groups, is what we might mean by the term gender identity. Most probably have one. This is not the same as having any love for the process of gendering in itself, or wanting to preserve it. This is about caring about what its results are, when it in fact does occur.

Moreover, with this mismatch, in many transgender individuals it takes place persistently over time, with the instincts for polarizing large enough that the mismatch causes a strong and significant decrease in flourishing - gender dysphoria. This will manifest differently in different individuals, depending on their individual histories, environments, coping strategies, privileges and temperament. I believe most or all expressions of gender dysphoria can be traced to this one mechanism. For some, they will note their own bodies having one set of secondary sexual characteristics, which are the same as those of the sex/gender division group that they are disinclined to be grouped with, and different from those of the group they are inclined to be grouped with. This mismatch develops into body dysphoria, and the resulting emotions may drive development into depression, self-loathing, dissociation or any number of other issues.

Analogously, observing a separation in social roles, behaviours and expectations will remind of the underlying polarization with the wrong gender division group, similarly causing cascading effects. These downstream effects may be the visible phenotype, or they may be masked by coping strategies against the dysphoria, so that for some, it becomes apparent that something was wrong only by the effects with regards to happiness resulting from beginning to fix it. For some the impact of the mismatch between gender identity and assignment within gendered divisions becomes apparent early in life, whereas for some it does not. Many are sufficiently afflicted, whether directly or by cascading effects and resulting secondary mental health issues, as well as by sometimes resulting social misalignment, to commit suicide - rates are unknown but at least 40% of US transgender individuals have attempted suicide pre-transition.

We are able to treat this unhealth through a two-pronged approach. The underlying issue remains for as long as the individual experiences gender divisions (which, again, are ongoing - gender being the social construct around reproductive sex) place the individual in the group mismatched with what their instinctual (and thus existing implicitly as a descriptor of that instinct) gender identity requires. We know of no way to change that instinct. While it is true that the process of gender division here most relevant is that of the individual themselves (the dysphoria stems from you yourself understanding yourself as being polarized with the group opposite to the one your instinct points to), we also know of no way to make an individual stop performing gender divisions in how they understand and interact with the world. Even those politically strongly opposed to the concept (like myself!) find themselves falling into these patterns, likely precisely because they have neural underpinnings; while they are social constructs they are not taught to a blank slate.

Instead, to help transgender individuals flourish, if we want to do so, we need to combine individual processes of transitioning, with societal processes of modifying the criteria by which we perform gender division. These two efforts, by transgender people and by allies, respectively, synergize to reduce dysphoria at the root.

Returning again to sex, there are plenty of secondary sexual characteristics we can safely and efficiently modify medically, over time. Surgeries cannot quite switch reproductive sex, though it can move an individual from one reproductive sex to no longer being effectively of the same mating type. Social transitioning, aided by changes in secondary sexual characteristics from medical transitioning, changes the way an individual is perceived by others and by themselves, compounded by building new habits, and body changes in themselves likewise changes the self-perception of the individual. When what is there is different, what is seen correspondingly becomes different. This is the goal of transitioning, which the individual transgender person may undertake.

Is this somehow false, or a lie? After all, gender as a social construct is built around reproductive sex at its core. Is it then somehow a falsehood if a person with one reproductive sex is placed on the side of a gender division that is labelled after the other reproductive sex? Only if gender is expected to be a statement of facts about the material world. As I've outlined above, it is rather reproductive sex itself which is that fact. Gender, instead, is the set of activities by which we relate to such facts, and one way of such relating, which here allows to improve human flourishing, is to deny their propagation into downstream perception, emotion, thought and action. This is not a delusion. If we would want to fertilize an egg with another egg, we would not use intercourse, we would use laboratory equipment. Facts remain treated as such for purposes of applications where this affects efficacy of our strategies. But denying them a place in our social constructs is not dishonest.

But might it still cause problems? Less than feared. In the process of gendering, even if we seek to make divisions based on reproductive sex, that is not actually how in practice we make most such divisions. Observing a person with a certain set of secondary sexual characteristics, we are often likely to place them into the gender division group we associate with those secondary sexual characteristics, even if we know them to have a reproductive sex different from that which this gender division group is named after and originally evolved to correspond to. Even knowing this (as in, knowing that this person - who can be yourself, or another person - is transgender) we are still more likely to spontaneously place them into the gender division group corresponding to their gender identity. As such, altogether, a transgender person can change their social presentation, can change their body, and compound these changes by observing the recognition of those around them, and in so doing, come to change what group they place themselves in when they - involuntarily, like all of us - divide people into gender in their perception, emotion or action.

That is to say, they may gradually come to understand themselves as being placed in the gender which is aligned with their instincts, those within which their gender identity is the implication. This then reduces dysphoria, and improves chances of flourishing.

The second prong of our strategy is that of changing how gender is constructed. This is where allies, unknowing or knowing such, help. As stated above, the processes that construct gender by dividing humans in our thoughts, emotions and actions did evolve - likely - to identify reproductive sex. Knowing reproductive sex of someone certainly informs our gender construction process regarding them, and the groups we divide into are labelled a priori with the expectations of reproductive sex. But as stated previously, gender as a social construct need not stay just a predictor of reproductive sex, even if it evolved for this purpose. We cannot change everything about it, because it has neural underpinnings. But we do learn about gender from each other, and how we construct it evolves over time across societies. We use the views of others when we make our own divisions of people into categories (and this is why your perception of the gender of a transgender person matters to them, whether they want to or not - as pack animals we cannot help but listen to each other when relating to the world!).

This means that it is possible to formulate and propagate the idea that we should take a person's own stated gender identity into account when we perform gendering. That is, when we divide humanity into groups labelled after reproductive sexes, with respect to our thoughts, words, actions, emotions, we are able to assign weight to what we know of the self-identified genders of others. This is not cleanly a choice; when encountering a person with very clear secondary sexual characteristics, it may still be hard to feel that they are not the gender corresponding to the reproductive sex which we associate those characteristics with, we may still end up - involuntarily, as with all things here - them to the one or other gendered division group that their appearance reminds us of, even if we want to take into account their stated instinctual need to be polarized with the opposite group, their gender identity. This is why a two-pronged approach is needed, individual transitions are also needed. But even so, coming into the habit individually and as a society to treat self-identified gender as a prominent source of input for the processes inside us of constructing gender socially by dividing humans into groups with respect to how we think, feel, speak and act with regards to them, this will eventually make that input more and more salient for this process.

That is to say, by explicitly letting gender mean, primarily, self-assigned, self-identified gender, and propagating this meme, we change the collective social constructs of gender. This has no impact for the 99% of people who are cisgender (claims that it weakens certain feminist efforts are false), but for the 1% that are transgender, it synergizes with their own transitioning, reduces their dysphoria, and improves their chances of flourishing.

Transgender people are blessed by those cisgender allies who, for no gain of their own, are willing to participate in this social transformation by changing how we think, feel and speak. It takes a village to raise a child. Similarly, it takes a society to transition. Older societies like Native Americans and others did similar things (modifying the social construct of gender to allow reduction of dysphoria for their transgender individuals) in creating and recognizing third genders, and this is now how we do it. I honestly feel gratitude, ongoing such, is in order.

So, to stop and take stock. Where has this rant gone?

First, I have reanchored the concept of sex, which can mean different things. A transgender (and transsexual) man who is on HRT and has had a mastectomy, but still have ovaries and a uterus, he still has a female reproductive sex, which he would lose if he also had a hysterectomy. This would not gain him a male reproductive sex, even so. Neither procedure grants him male chromosomal sex. However, he is mostly anatomically male, he is hormonally and neurologically male. So depending on what sex we are referring to, he is either male, female or neither. His gender is male as that is where his own constructs place him, and it is where we place him also, he is socially a man, his gender marker is male, and we should treat him as a man in every regard except not solicit him for sperm donations or purchase of medications against erectile dysfunction. He is all these things even if he wears pink frilly dresses and works in childcare. This is how we should think and speak of him. Moreover, another man who loves only other cisgender men, he should in turn think of and speak of his sexuality not just as "gay", but as "gay, cis only", so as to help disentangle his gender preference from his anatomy/oirigin preference (both are valid, of course, but assuming the first implies the second runs counter to how I hope we will work with language!). We should do this because all of those things are aspects of how we construct gender socially, by dividing people in word, thought, action and emotion, and there we have a choice on whether to make those constructs such that he is recognized, and we ought to make this choice such, for him and for others like him. But yes, sex has (several) meanings that are not the same as gender, and that are neither social constructs nor malleable in the same sense. In some senses a transsexual changes sex, in some sense they cannot as yet do so.

Secondly then, this is also why we need to recognize gender as an even more relevant concept. Some have stated that sexism is understandable not as discrimination by gender, but as discrimination by sex; cis men assaulting and raping cis women choose them based on the material fact of their reproductive sex, not based on their gender identity. As I've outlined, gender identity is not the label others place on us, but the label we need placed on us in order to flourish, so that is beside the point. More relevant, in my above description, gender is the division of humans with regards to our actions, words, emotions and thoughts about them, into categories labelled as and anchored to reproductive sex, and driven and informed - among others - by observations and knowledge of reproductive sex. While it is possible that a hypothetical cis man rapist would shun transwoman victims even with identical anatomy, but would seek out transman or nonbinary AFAB victims, he is still under my definition constructing gender here, it is just that his process of doing so largely does not respect the gender identity or self-defined gender of any other person. That is to say, in this as well as in other cases of sexist oppression and unfairness, gender as I have defined it does describe and capture specifically those behaviours we seek to prevent and modify. Altering how gender is constructed - including by unlinking many stereotypes, expectations and power imbalanced practices - is how we would go about fighting these oppressions, and as feminists this is what we will do. While the challenge has been posed that gender, as opposed to reproductive sex, is somehow ill-defined through circularity, I have outlined above how this is not the case; by understanding it not as a standalone label but as the description of a process drawing, among other things, on reproductive sex, such circularity is not a concern for the clarity or validity of its definition.

Third, I have outlined my current beliefs on the cultural and biological basis of gender, especially insofar as thus gender identity arises implicitly (it may not be something one can look directly at and "feel") as a property of instincts human beings have on where to try to polarize themselves across gender divisions anywhere in life. I have argued here that it is a strong but mostly invisible instinct, which underlies several forms of potentially lethal and debilitating dysphoria in the small fraction of people who are either binary or nonbinary transgender. While manifestations can vary a lot between individuals, this is a severe and significant obstacle to the flourishing of such people. Moreover, it is not a choice, nor is it a political standpoint to somehow prefer the social construct of gender to remain in place. Rather, it is a need to use particular strategies for navigating gender when it does manifest whether we wish it to or not, and those strategies remain perfectly compatible with the víew and agenda of dismantling both many of the associations of gender, and the process of gender divisions as a whole. However, we must also accept that we did not evolve to be blank slates; only transhumanism could bring us there. We as we are will face and live within manifestations of the social construction of gender as a division of human beings with regards to how we feel, think, act and speak about them, for now and for the foreseeable future. We can and should work againt that in itself, perhaps, but we must also do what is needed to cope, and to let as many of us flourish as much as we can.

Fourth, I have outlined how I regard the effort to reduce the dysphoria of transgender individuals as a two-pronged effort. On one hand, there is the individual journey of transitioning - changing one's sex insofar as is needed and possible, for one who is transsexual, and working from one's own position to make one's gender such as to minimize dysphoria, minimize the mismatch between the groups one is placed in, and the groups one have an instinctual preference to be placed in. On the other, there is the society-wide effort to alter how gender is constructed, so as to recognize maximally self-identified stated gender (which is a proxy for gender identity which is an implication of the abovementioned instinct) as a feature informing the processes by which we do divide individuals into genders, on those occasions we nevertheless find ourselves doing it (and we probably do that all the time, because our brains work that way). This makes gender as a social construct less efficient as a neural net predictor of reproductive sex, but makes it more efficient at not preventing transgender individuals from flourishing. These two prongs come together in that what matters for dysphoria is whether or not the individual transgender person is able to find themselves placed in the gender division group their instincts point to (which need not have any bearing on detailed gender roles or stereotypes, which are anyway things we should unlink off of gender!). Whether or not they can will reflect both their individual transition journey and the surrounding societal recognition of their self-assigned gender as informing gender divisions, since all people use their perception of the views of other people to inform their own perceptions, no matter how independent they may believe themselves to be. Thus, successfully reducing dysphoria also builds crucially on top of the work of allies in changing the meaning of gender in public discourse and culture to mean self-identified gender more and more. We are deeply blessed to have you do this, and gratitude is, again, in order.

0 notes

Link

(Part 2 of 3)

Sadomasochism

“You’ve got other really fun things, like this idea of disempowerment. Here you’ve got the castration — sorry, I mean the beheading of Holofernes — and then on the right, you’ve got the same thing,” Sofia says, alluding to a pornographic image of two males engaging in a sex act as a woman ‘forces’ one of the men into what would be the submissive female role in heterosexual BDSM practices: bound, with a slave collar, being sexually abused. Sofia does not elaborate on why he believes these two images portray “the same thing”. Presumably he is attempting to establish a correlation between a man being violated as a woman and death; that the loss of the masculine role — castration — is metaphorically equivalent to being killed. Framed this way, the common euphemisms of transgender activism can possibly be traced back to BDSM practices and the narrative that has been constructed around fetishes.

For instance, so-called dead naming (referring to a trans-identified person by their birth name) could also be considered as a reference to ego death, or the complete loss of subjective self-identity. This framework could assist in explaining why it is that trans activists insist that words are literal violence, where the act of naming men as men, for example, deconstructs their illusory, projected self. In turn, it is possible that linguistic ‘transphobia’ can elicit a similar thrill as the sort induced by being humiliated, even when the humiliation is not a taunt, but the truth. In this sense, the public is unwittingly being duped into participating in BDSM, either as the dominant — those who criticize gender ideology — or submissive — trans activists themselves. Crucially, material reality, especially women’s reality, is being used as the vehicle for this rouse. When one considers that BDSM practices involved in forced feminization revolve around humiliation as a key point of arousal, this also could implicate an element of sexual pleasure involved for some in being considered to be subjugated or oppressed — that the male claim to a female identity is, in itself, a fetishization of women’s systemic subordination.

vimeo

The Eroticization of Castration

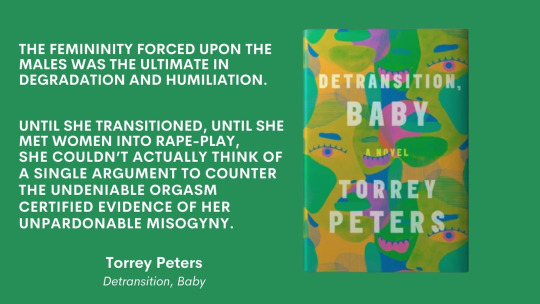

“Here we’ve got the very traditional sissy porn Lolita dress that my friend Torrey Peters lent me… who wrote an amazing book called The Masker which I recommend for everyone on this chat.”

A brief explanation of Torrey Peters and why this matters: Torrey Peters, a trans-identified male, is a published American author who has found a market for books of written pornography with loosely developed plots. The Masker follows participants in a masking convention, where men don silicone body suits and face masks in order to resemble women and subsequently engage in sexual activity with each other. Peters’ portrays this fetish lifestyle as a pathway towards a decision to permanently alter one’s body through breast implants and hormones. In March 2021, Peters was long-listed for the UK Women’s Prize in fiction for his recent publication, Destransition, Baby, which I have written about here. Peters is increasingly being promoted by US media, and his ex, Harron Walker, also a trans-identified male, is employed by the women’s magazine W and has written for ‘feminist’ outlet Jezebel, having formerly written for the notoriously misogynist platform Vice, as well as Out magazine.

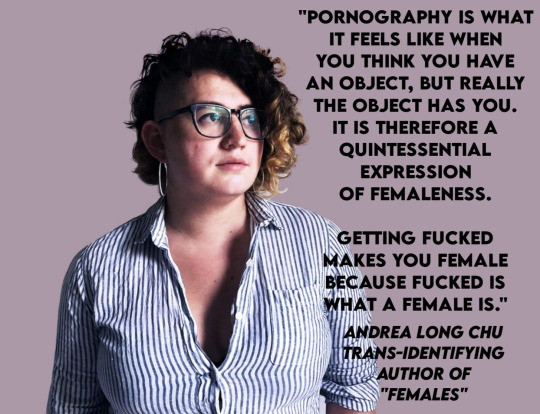

Sofia is also clearly a great admirer of American academic Andrea Long Chu, who has been published in The Journal of Speculative Philosophy (2018) and Differences, a Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies (2019). Chu, a trans-identified male, wrote Females: A Concern, which was published in 2019 by Verso Press, and contains remarkable statements of misogyny as though they were undisputed facts.

Here Sofia quotes an essay, Did Sissy Porn Make Me Trans, wherein Chu argues that womanhood can be defined as a state of powerlessness. Chu presented this essay as a speech at a number of reputable universities in the US, including Columbia University, Vassar College, UCLA, and UC Berkeley.

“Castration anxiety is easily mistaken for the fear that one will be castrated. In fact, it is the fear that one, being castrated, will like it. The threat, in other words, is not that you will lose power (this is basically inevitable, and not much worth worrying about), but that you won’t actually want power, after all. Too often, we imagine powerlessness as the suppression of desire by some external force (maybe someone else’s desire), and we forget that desire, in itself, is often, if not always, an experience of powerlessness. Most desire is nonconsensual, most desires aren’t desired.” — Andrea Long Chu, Did Sissy Porn Make Me Trans?

The idea that women are castrated males is not new, nor is it particularly insightful in regards to the reality of women’s lives. Much has been said and written about this in psychoanalysis and in feminist texts. It should be concerning to anyone, men as well as women, that this idea is resurfacing in gender ideology — especially when we consider that children are quite literally being castrated in the service of this belief, both by means of powerful drugs euphemistically referred to as “puberty blockers,” as well as genital mutilation surgeries. The story of David Reimer is a tragic example of this. In 1966, Reimer, whose circumcision was botched as an infant, was experimented on by psychologist John Money, who decided it would be better to raise Reimer as a girl. Money believed that sex was socially constructed, a belief also promoted by current trans activists. Reimer’s case represents one of the earliest modern examples of what is called ‘sex reassignment surgery’, and John Money forced David to imitate sex acts with his brother Brian, instructing David to play the submissive, or ‘female’ role. Money justified these criminal acts by claiming that “childhood ‘sexual rehearsal play’” was important for a “healthy adult gender identity” (As Nature Made Him: The Boy Who Was Raised as a Girl, John Colapinto). The sexual abuses inflicted on the twins by Money caused them such severe distress that both Brian and David committed suicide.

vimeo