#I agreed to do a freelance project and negotiating that is a big part of it

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

I shouldn’t be this anxious on a Friday but here we are

#weeb problems#I’ve been increasingly all week#all month even#I agreed to do a freelance project and negotiating that is a big part of it#looking at my free time and being like ‘oh how am I actually going to fit this in???’#I haven’t even started it yet#I’m trying to force myself to do it because money and experience and not avoiding things#but uuuugh

0 notes

Text

pictured above: the stages of our morning (fierce tussling, followed by a quick nap, followed by some adorable snuggling).

I slept nine and a half hours last night by accident but I think my body needed it. job hunt + big life decisions are taking a lot out of me!! then I spent 9:30-12:45 writing an extension request for the grant and a salary negotiation/promotion request for my boss. that was a little nerve-wracking but I think she’ll be receptive. also having to write out a description of how my role has evolved was actually a very useful exercise! it made me realize that my job responsibilities really have increased significantly since I started three years ago, but my pay and title haven’t changed at all. fingers crossed it will go over well… and if it doesn’t, it just means I can move to seattle sooner.

some further job musing behind the cut…

here’s where my head is at right now:

I want to do well in my Monday afternoon interview and get an offer (partly so I have leverage in negotiations if needed) but I think that unless something really changes for me in that interview I am going to turn down the job. the woman I talked to who was in the role before me said the red tape of government work is even worse than academia and got so maddening she couldn’t stand it for more than a year. she had some positive things to say about the work itself + the team but said that the intensely bureaucratic culture meant that every project took forever. idk I know no job is perfect but I’m not sure it’s a great fit.

turning down that job (if I even get it) is a risk because I have no other offers or leads right now, apart from the possible extension on my current job… and that one is v much at the mercy of the very slow-moving foundation. multiple people have said it’s likely they’ll approve the request, but that’s also kinda what everyone thought about the full renewal and we know how that turned out!! so I think I am going to make myself continue actively applying for remote + seattle jobs so that I can at least feel like I’m working towards a backup plan.

if the one-year extension doesn’t come through and I don’t get another job offer before 9/1, I have about a month and a half of my ADD meds left + three months of my ultra expensive sleeping pills. since you can apply for COBRA retroactively, I think I will just plan to not have health insurance for that first month while I continue job searching. I guess I can apply for unemployment (I don’t really know how that works or how long it takes to get it…). the good news is the IRS owes me $2k from my tax refund + I will be getting get my vacation days paid out from my current job, so that should give me enough to live on for a bit without having to dip into savings.

or I also have some short-term options. there’s a job at my university that I know from a friend is desperate to hire a humanities PhD (for some reason they’ve had at least one failed search) so maybe I could take that last minute before the semester starts. or I could take a remote college admissions job and make good money for the season (downside is usually no benefits there so I’d be paying for meds out of pocket). both would be less than ideal for various reasons but better than not having a job.

I think right now my ideal situation is: I get my salary request approved, the foundation agrees to extend our grant, and I spend the year running the program while also building up some skills/experiences for going on the job market again. for instance I could take a grant writing course and get a certification for that & then maybe do some volunteer grant writing in my free time to build up a portfolio. or I could take on a freelance writing job or part time communications role, again to build up my portfolio. staying attached to a university also means I could also do lots of relevant free trainings there or even take advantage of tuition benefits to take a class… like I’d love to develop at least some basic quantitative analysis skills, or take a formal class in program evaluation/assessment. basically I think I could use the time in a focused way to make myself competitive for jobs in the future. but we will see. I am trying not to put any eggs in that basket right now.

okay okay. time to put all this away for the day, I think. I’d like to spend some time messing around with audio editing for this podcast to see if I can figure it out or if I need bec’s help lol. I’m kinda loosely in ideation phase for a new novel project but I’m trying to put minimal pressure on it right now and keep it really relaxed/open in my mind… too much other stuff taking up my emotional bandwidth right now and I don’t want to accidentally turn this project I’m intrigued by into another source of stress! ok ok BYE FOR NOW sorry I just gotta process my every thought and feeling aloud in my public diary.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why Freelance writing works - AOU Creative Group

It is not breaking news to tell you that the gig economy is growing every year and that companies big and small are using freelancers to fill in gaps when needed.

This growth is happening for many reasons, but first among them is the hard truth that having employees is expensive, challenging, and in some cases, unnecessary.

Unnecessary? That sounds harsh even as I read what I have just written.

But, yes, unnecessary. This is the reason that freelancing works — for businesses and for the freelancer, especially at an executive skill level.

Hiring an employee means that you, as a business owner, must find talent and create a culture that keeps them, you have to pay your worker the agreed-upon consistent wage, you have to handle taxes and benefits for the employee.

The process takes a great deal of time and energy — and can eat into precious resources of both.

In the case of freelancing, a business owner gets to hire the best talent they can afford at a price that the freelancer offers (or you negotiate). The engagement is project-based and when the work is over, you and the freelancer choose if there is a next opportunity to work together.

The fact is that great talent is hard to find, hard to hire, and even harder to keep for many small to mid-sized businesses.

Freelancing works at the executive level because companies can take advantage of the talents of highly skilled freelancers — while the freelancer is able to diversify their work, giving them the agility to choose projects, hours worked and clients accepted.

Copy and content writing are areas where freelancers and businesses partner to great success.

“To be the most effective, a content strategy has to be consistent. And to build brand authority, it has to be expert, and authoritative.”

SO WHY DOES FREELANCING WORK FOR WRITING?

Though certainly not the only skill that is easily freelanced, writing is one that many people can do — but few do well. Especially at the executive level needed for brand development and SEO.

Most small to mid-sized businesses have a great need for professionally written content, but not the budget for a full-time writer on staff.

That is where freelancing comes into play.

A highly-skilled freelancer can offer a business:

Well written, engaging content. When you hire a professional writer, especially at the executive skill level, you can be assured that the work that is created is high quality, original, and crafted to engage your reader.

Authoritative articles that build brand reputation. A great article or blog requires research and offers education or information to your reader. It isn’t designed to only “sell” to your customer, it offers them an experience that keeps them on your website and builds customer loyalty. This, in turn, increases your website search rankings.

Technical skills that add SEO integration into copy. Executive-level copywriting requires more than just a way with words. It requires technical skills to integrate tools that improve the SEO of your website. Structured schema, headings, keywords are all parts of a technically integrated blog/article that must be included to make the work more effective in search rankings.

A FREELANCER WHO WRITES FOR BUSINESS BENEFITS TOO

As a freelancer, a highly-skilled writer can earn a solid income (even 6-figures) by crafting interesting and professional work for clients.

Freelance writers have a skill that is in demand as the economy moves more and more into the digital space.

Writers can specialize in emails, blogs, video scripts, books…or they might niche in a particular industry such as financial services or technology.

For a freelance writer, the world is open and the sky is the limit on how much you can earn, at least at the executive level.

THE BOTTOM LINE

Engaging a highly skilled freelancer (or freelance company) makes sense for businesses that do not have the budget to hire a full-time writer.

A freelancer can save a business the time and money that it takes to hire employees and keep them.

A more efficient way to create a content strategy that is aimed at searchability, brand development, and lead generation is to contract with executive-level freelancers on a per-project basis.

This also works best for the freelance writer. You can name a price for the project and have the flexibility to select not only the work you want to write but also the hours you wish to work.

As a freelance writer, you have freedom.

In the end, content creation is an ideal situation for a freelance-business relationship. Both parties win.

What more could you ask?

1 note

·

View note

Text

Selling Your Story – Peaks and Pitfalls of Publishing Contracts

Points to consider when deciding if a Publisher is the right fit for you.

Landing a publishing contract is the Holy Grail for many creators who set their sights on “breaking in” to comics, and it’s understandable as to why this is the case…

It’s a big ego bump for starters. Someone external, has recognised your work as good enough to be associated with, promote and sell. In terms of logistics, publishers have established distribution and promotional tools at their disposal and should have a bigger voice than you alone to share your creation with their customer base. As an independent creator, associating yourself with something bigger can also boost your profile – Like a more positive version of joining a gang in prison (I’d imagine).

The subject of publisher relations with creators, differential deals and the fairness of agreements became the subject of debate across comics twitter recently. Voices of creators and collaborators I have a great deal of respect for came out to talk about their views on several publishers with messages of both condemnation and support. Wider spread trends led to a number of freelance workers actively sharing what they had been paid for projects. While there’s no need to pick through a debate which is easily searched, I’ve been thinking a great deal on the subject of publisher contracts. Specifically, how an independent creator can review and consider what publishers are offering more critically in the hope they secure favourable terms, or at very least don’t feel regrets down the line as items not considered at the time of signing come home to roost.

I’ve sat to write this piece in the hope it sparks more discussion and helps those working in the small press scene, which I love, ask the right questions and considering offerings from publishers who show interest in their work. Hopefully I’ve made it accessible and not hideously dull.

Before we take a step further, let’s cover a few notes and caveats here:

Who is this guy? – I’m Andy Conduit-Turner a writer and extremely small name, in all but letter count, in UK indie comic publishing. The chances are, that if we’ve not met, you’ve not heard of me.

My comics contracting experience is primarily limited to drafting my own commissioning contracts to engage with collaborators for comics I have written, and in licencing short stories which I’ve written to appear in anthologies and other mediums produced by others. At the time of writing, I have neither signed with, or been rejected by any major (or minor) comics publisher and am not providing comment on any observed content which may or may not appear in a publishing agreement from any given company.

I am, neither a qualified legal professional or literary agent. In the event any contract you ever receive for any purpose is of extreme importance, investing in the support of a qualified person with greater industry experience is of far greater value than anything you’ll read here.

Outside of comics, my professional career and other personal projects over the last decade have seen me review, interpret, question, edit and respond to countless legal agreements for a variety of purposes. This has left me with a wealth of experience in considering longer term impacts for both the purchasing and suppling parties of service agreements – I’ve spent a great deal of time having both commercial and capability-based discussions prior to contracts being signed.

This is by no means an anti-publisher piece – Regardless of where you stand on recent publishing discussions, I’ve no desire to create an Us (Creators) vs Them (Publishers) sentiment here. There are countless publishers who are passionate about sharing creator’s stories, invest significantly and add a great deal of value to both individual projects and the industry as a whole. No reputable publisher is out to trick creators or deliberately give them a raw deal. That said, as with many transactions, a publisher is a business with an end goal of limiting liability and generating revenue in both the short and long term – Depending on your ideological feelings, this isn’t necessarily an inherently evil objective, and it’s how publishers remain in business.

Your publishing contract is equally not a formality, a magnanimous offer from a friend with nothing to gain from the arrangement, and your unconditional ticket to success and acclaim. Different deals will work for different creators – A good deal to one will be an unacceptable deal for someone else and there are few terms which would be universally perfect or awful for everyone. I’d hope through these pages I can maybe help you consider your offers, ask necessary questions and make decisions you’re comfortable with for your own circumstances.

Negotiation carries risks – Especially within the sphere of indie publishing, there are a couple of truths we need to reflect on.

1. Comics are an attractive and exciting creative medium for people to get into. Especially if a publisher is welcome to unsolicited submissions, they are likely to have no shortage of people interested in publishing with them.

2. Many publishers aren’t huge organisations. In the event a member of their core team is not already a legal professional, it’s unlikely they will have a legal department on their staff to directly manage adjustments to legal documents and agreements.

What this boils down to is that, many publishers may simply not have the resources or interest in negotiating or adjusting a contract with you – There’s every chance that the offer made to you is non-negotiable. While I’d argue that the withdrawal of an offer in response to a question asked or statement challenged in good faith is indicative of the professionalism of the organisation in question, you should be prepared for the fact that being the squeaky wheel may not land you the deal you want, and may take the one you have off the table.

A Note on NDAs and Market Norms

NDAs, or Non-Disclosure Agreements are very common, as part of, or prior to contracting in many industries. They are typically used to protect (in this case publishers’) private or proprietary information concerning their business practises, contracting terms, project pipeline and pay rates private and confidential. They are a routine consideration and not indicative of any sinister goings on. In keeping with professional conduct, if you sign an NDA you should, of course, respect its conditions though here are a few considerations and questions you may ask or confirm however.

1: Is the NDA mutually beneficial – While you are agreeing not to share the details of a publisher’s business and offer outside involved parties, does the signed NDA bind the publisher to offer you the same regardless as to whether the end result is a signed publishing agreement?

Are there stated commitments to your work remaining confidential and not circulated to other outside parties during your negotiations? What commitments are made to the return / disposal of any project details or materials shared should an agreement not be finalised.

Additionally, can you expect details on deals you accept in terms of up front remuneration, percentage splits on profits and additional contract terms to remain confidential?

2: Pitch exclusivity – Are there any expectations, formal or otherwise that you should not pitch your comic elsewhere until negotiations have been concluded?

3: Your right to advice – No NDA should prevent you taking appropriate professional advice before signing any final agreement.

Rules on business competition internationally, already provide a great deal of legislation to ensure businesses to remain competitive and prevent illegal practises such as price fixing and market sharing. While market norms may dictate and guide the offers you’re likely to receive competing businesses should not mutually agree to adhere to set fees or conditions. At this point I’ll pause and note that I don’t hold the market specific professional knowledge to apply Anti-Trust and similar business competition legislation to publishing contracts – These should be forefront of a publisher’s mind when managing confidentiality of contract content.

So…With all of that now said (in painstaking detail) let’s get into this shall we

What’s in this for you?

So, you’ve pitched your book to a publisher and they’re interested in working with you? Great news! Now comes the time when you need to consider what you want to get from your potential partner, and consider, realistically, what you’ll accept. For many creators your wants and expectations may include:

Contribution to production costs. Particularly for writer led teams, an ability to appropriately pay artists, colourists, letterers, editors and other professionals make up the bulk of comic production costs even before downstream logistics such as printing, marketing and distribution come into play. Many publishers may state up front whether this is a model they can support. Initial production costs add to the overall risk and increase the volume needed to sell before profits are realised. Consider – Landing a publisher may not relieve you of the need to raise personal funds or take to Kickstarter.

Upfront royalty payments. A noble dream for some, though likely only realised by more established creators. Belief in your project will need to be high to warrant an upfront payment to the creator for a book prior to a single copy being sold Consider – Manage your expectations here, how promising is your pitch? Do you have a track record of success that offsets the risk of an upfront pay out?

Percentage Profits – This is likely to be a long-term arrangement of any publishing deal whereby the creator and the publisher acting a licence holder take an agreed % split of future profit revenue generated from the project – Profits from what exactly we’ll come to later. Consider – There’s no way around this, any additional step in the process here are going to reduce the by unit revenue you receive per each sale. By working with a publisher, the benefit to you is that they support you in, ideally, selling more copies than you would alone.

Production and logistical support – Sure, you know writing, art or whichever your creative field may be, but there’s every chance that your publisher is more familiar with the processes involved with getting your book into people’s hands. With established relationships with suppliers and retailers your publisher may also be able to optimise the per unit profit on your book sales, in addition to increasing your potential audience through supply networks and wider convention attendance.

In some cases, your publisher may also take a creative role in the process, appointing an editor, or suggesting changes to make a book more marketable in their experience – We’ll also return to this point later.

Comic Financials - Hypothetical example – Comic X

Working without a publisher

You as creator spend £2000 on the production of your comic (Art, letters, colour, whatever!) Print volumes allow you to obtain copies of your book at £2 per copy

You price your book at £5 per copy Let’s then also assume a modest spend of £200 on website, and attending some local cons, and you break even on Postage and Packing. Under this model you’ll see a profit on your creation once you sell your 734th copy of Comic X. This assumes you sell exactly all of your stock and are left with no additional copies which you’ve paid to have printed, but not yet sold. Let’s make this a tiny bit more complex and suggest that you diversify from selling physical copies online and at cons alone. You begin selling digital copies via an established digital store front at £3. You also connect with local comic retailers who agree to carry copies of your comics in store. To keep this simple and not lose the remaining 3 people this dive into maths hasn’t lost already let’s assume that your sales across all avenues equal out to 1/3 each, and once again all copies you produce will sell. The digital sales have no print cost but the digital storefront takes 50% of the sale price

The stores agree to purchase copies of your book from you for £4, creating a 33% share on profit after print costs.

Under this scenario, Comic X will officially be profitable after around 245 direct physical sales, 489 digital sales and 367 sales via stores.

Working with a publisher

Under this model, we’ll assume that you as a creator invested the same £2000 in production costs but nothing further, leaving the publisher to manage the printing along with costs for attending conventions etc.

Outside of the numbers here, your publisher is also the party taking the risk regarding the volume produced if any copies go unsold. The trade off is that your publisher will take a percentage of any profits before they reach you. For this example, let’s say you agree on 50% revenue share and receive no contribution to production costs or any upfront payment.

For argument sake, let’s assume your publisher secures the same unit costs and margins (though you’d hope they may be able to negotiate better through volume purchasing). Understanding a publisher’s direct cost with con attendance, and marketing when applied to a single book is a level of hypothetical we won’t attempt here.

Focussing on you as a creator, under the same sales methods used in the non-publisher model you would begin to see profit on your production investment of £2000 from publisher paid royalties after 445 direct sales, 889 digital sales and 667 in store sales.

After all this talk of money, the first thing to recognise is that it isn’t everything to all creators. Many will consider the long-term goals of building an audience as a pathway to bigger and better things, or simply an investment in their creative hobby. Those with realistic aspirations will likely not expect to anything resembling a profit from their early books (save perhaps for those with the skills to produce a comic entirely alone or with collaborators satisfied with payment purely from sale revenue). For many creators, having a partner who ensures copies of their books get into people’s hands, minimising their own administrative efforts is the goal.

What is critical is to do your own calculations, consider your goals along with level of financial investment and energy you have to invest in selling your own book. In this simplified example, we’ve not considered the accuracy of print orders vs sales, tax applications or eligible rebates or potential publisher costs deducted from profits to account for their operational expenses, but it should give you a loose model to consider your own investment against.

Potential Questions – Depending on your financial and creative motivations

What sales numbers does the publisher consider to be a success? Assuming the publisher will set sale price – What margin do they consider acceptable vs costs? What sales avenues does the publisher use? Does the publisher have established relationships with distributors and retailers with agreements to carry their stock? If so, what regions and countries do they have distribution networks within? Which electronic store fronts does the publisher make books available via? What volume of conventions, in which locations, does the publisher typically attend? Are they willing to share any statistics on which platforms generate the strongest sales? How, if at all, are publisher overhead costs factored into overall sale profits for division between publisher and creator? Does the agreement permit the creator to obtain copies of the publication at cost, or discounted rates for either personal use or onward sale? What marketing methods do the publisher deploy to promote new and existing content? Does the agreement, place any expectations or limitations on the actions of the creator to promote the comic? Does the agreement commit the publisher to any minimum volume of books to be produced for sale, or resources allocated to promote the publication?

What’s in this for them?

Now we come to the other half of the deal. In working with a publisher, you grant your partner certain rights in potentially both the short and long term. Understanding the rights, you’re happy to sign away and the long-term implications can be key points in your decision-making process.

Your potential publisher may request some of the following:

Percentage Profits on book sales – This is a given and how your publisher will make the most immediate return on backing your comic and investing in its production or distribution

Editorial and creative direction – While some publishers may primarily take on completed projects, others may provide editorial input. For many creators, this may be beneficial professional, input to improve the project overall. Consider – When you engage an editor privately as a self-published creator, the final decision on how you incorporate your editor’s feedback is your own. A publisher driven edit may take the final creative control out of your own hands. As with many aspects in this section this can be a positive, but it is something you should consider and make peace with before you agree to your publishing deal.

Revenue on sale of promotional and licensed goods – As part of your agreement, your publisher may gain rights to produce and sell a variety of goods associated with your comic. For a small press projects, this could be as simple as prints, postcards and pins made available as add on purchases, but an agreement could equally account for additional 3rd party licensing. Consider – From a financial perspective do you retain a share of the profits from the sale of promotional or licensed goods? Is the rate in line with the percentage you earn from book sales? Depending on the answer to these questions, if your book is successful and lends itself to popular merchandise, you’ll potentially see a larger return on your production investment more quickly, in time you may even see more royalties from the tasteful sets of commemorative glassware your story has produced than the book itself. From a creative standpoint, you need to consider that you are likely giving up a degree of control here. If you’ve strong feelings that series logo should never appear on a tote bag, this is potentially something your deal may remove your option to veto in the future.

Adaptation rights – In licensing your comic for publication, your publisher may request rights concerning the adaptation of your comic into other mediums. These rights may extend to written and audio productions, stage, television and film versions and interactive media such as video games. The requested rights may be inclusive of both financial benefits of licensing for alternative mediums and overall creative control in the adaptation for other media. Consider – If you’re a creative person with hands in other media, be it a keen filmmaker or an apprentice of coding, you may wish to seek to retain your own rights to pursue alternative interpretations of your story. Particularly in fields you have interest in. This may also be the time to consider how you would feel about any alternative take on your work with which you may have no creative involvement or influence over.

Sequel / Spin-off Rights – In agreeing to publish your project your publisher may also requests rights relating to production of related projects, both in comics or other media (as detailed above). These rights may include first review and option to license the new publication prior to it being offered to other publishers, the right to engage the creative team professionally to actively work on a related publication, or potentially engaging a separate creative team. Consider – As with the above point, your decision on agreeing with these terms will depend on your overall attachments to the project and your own long-term plans for ongoing related stories. If the idea of having limited or no control on how your original story grows into future projects gives you cold sweats, this is a right you’ll need to consider your comfort with, before you sign. How important is having ongoing control to you?

Potential Questions – Depending on your financial and creative motivations

What history does the publisher have with facilitating adaptation of comics to other media? Does the agreement, obligate or limit the creator in efforts to adapt the publication for other media? Does the publisher actively seek opportunities for property adaptations, or is this handled ad hoc as interested parties approach the publisher as licence holder? Does the publisher’s right to financial share in adaptation driven revenue differ in the event that the publisher take no active role in adapting or pitching the an adaptation of the property? What rights do the publisher hold regarding the sale or transition of publishing or ongoing licensing rights to a third party?

Overall, considering the ongoing rights and control a creator or creative team is willing to hand over to a publisher will be a critical point for many in making a decision before signing an agreement. How you perceive the value of publisher input, a potential reduction in creative control and your confidence in the long-term potential of your story will be key points in influencing what you’re comfortable in conceding in exchange for the benefits your publisher brings to the table.

The Finer Details

With the main points of your agreement carefully reviewed, it’s time to consider the ifs and buts, concerning the terms and limitations of your agreement.

Time – How long does your agreement grant the stated rights to your publisher? A set period? A set period with right to extend or first refusal to negotiate extension on similar terms or terms related to performance? Indefinite? Location – Are publication rights granted internationally or only in certain territories? Does your selected publisher have capabilities to market and distribute in all stated territories? If not, do they actively seek third party partners to distribute successful publications in additional territories?

Obligations – Are there stated timings for release, efforts to market, volumes sold, or stock made available for purchase a publisher must maintain to retain the license to your comic? Remuneration and Reporting – How frequently are royalties calculated and paid to the creator or creative team? Are there lower and upper limits to disbursement amounts? What reporting does your publisher provide to indicate gross profits leading to creator revenue share? Specifically, when it comes to matters of accounting. If you intend to maintain a financial interest in the performance of your work, appropriate transparency of accounting may be essential to understand your publisher’s level of investment and gross earnings before final profits are divided? Most organisations should permit you a right to audit, but be mindful of the conditions applied. Permitting a deep audit via the appointment of an official accountant able to review documentation on a publisher’s premises may fulfil legal obligations but creates an immediate pay wall for you as an independent creator, whose initial earnings on a single book may not warrant the investment.

If your potential publisher is able to provide sample reporting, you can accommodate yourself with the level of detail prior to signature and assure yourself that the level of transparency meets your level of interest.

Legal obligations – In addition to any submission conditions when you pitched your book, signing a publishing agreement will almost certainly involve your further verification that the work is your own and indemnify your publisher from any obligation or responsibility should this statement prove inaccurate in the future. In addition to the obligations on the creator, take note of any commitments made by the publisher to protect the IP you are licensing to them, and potential indemnity from any actions arising from material changes to the work or subsequent adaptation upon which the publisher, or their representative exercises creative control.

Limitations and release – Tied to the any limitations relating to time or location stated in your contract, it’s also worth noting any other terms which would lead to overall rights being returned back to the original creator or creative team. The most commonly anticipated reason for this would be publisher insolvency, though in some cases a struggling publisher with the appropriate rights could look to sell on any held licensing rights to a third party to raise capital prior to this occurring (assuming your agreement permits this). Clauses that benefit the creator in this area could speak to the minimum level of production or service provided to promote your comic, which if not met over an extended period results in the rights returning to the creator to pitch elsewhere or develop further with no further obligation to the publisher, thus holding your publisher to a higher degree of accountability for your book’s ongoing performance. Another alternative may represent a defined buy out clause, permitting the creative team to release themselves or further obligation to a publisher by either ensuring a pre-defined return on the publisher’s initial investment or a sum equal relevant to the book’s performance. The latter examples, I’d anticipate would be less frequent in their appearance within standard contract language, however these may be some of the most essential inclusions for a creator who is invested in the long-term management and performance of their work.

For an example, we’ll return to Comic X…

Worst case scenario…

Joe Creator, writer of Comic X, signs a publisher agreement granting licencing rights, inclusive of, merchandise, sequel and adaptation control and financial rights irrevocably to a publisher.

Joe’s agreement sees the creator receive 50% of Net profits from book sales but nothing from any additional licensing or merchandising unless directly engaged by the publisher to work on this new content under a separate agreement. The publisher will manage distribution and printing costs but does not contribute to the initial creation cost for artwork and associated tasks.

The rights will return to Joe only should the publisher file bankruptcy or should they fail to produce any volumes of the work within a defined period following initial project completion.

With no minimum term of service, the publisher fulfils their obligation to Joe through a short production run of 50 copies of their book, which are not directly marketed by the publisher but organically sells 30 copies through their inclusion on the publisher’s stand at conventions. The remaining 20 copies are sold at stock clearance reduction prices and do not recoup their print costs. The book is not listed digitally or marketed to any retailers. In the end of his first year since publication, the royalties owed to Joe from the profit share fall well below the minimum payment threshold and no payment is made.

In the five years that follow, the book remains listed on the publisher’s store front as “Out of Stock” and based on performance no further print runs are ordered.

Meanwhile, Joe continues to build career momentum through well received subsequent releases, published independently and interest in obtaining adaptation rights for Joe Creator properties hits public consciousness. Having secured irrevocable licencing rights the publisher secures a lucrative 3 series deal with Netflix adapting Joe’s original Comic X series. Netflix opts to use their own writing team, whose agents ensure they are recognised as lead creatives. A credit listing “Based on Comic X by Joe Creator” appears at the end of the opening credits, but everyone skips these.

With the Netflix series differing significantly from the original Comic X, rather than reprint the original, the publisher opts to engage a different creative team to spin off a new ongoing series based more closely on the aesthetic and themes of the new Netflix creation. The financial impact to Joe from creating the original work remains fundamentally minus £2000 as the £35 owed to Joe in previous revenue falls below the minimum payment threshold. This is an extreme example, played up for the sake of hyperbole, but hopefully it illustrates the point Consider your conditions carefully, what you gain, what you give away, and the level of effort your publisher commits to you. and finally.

Know who you’re dealing with - Know your own worth

Throughout previous sections, I’ve encouraged creators to consider what they want from a publisher, what they are happy to give in exchange and the finer details of agreements.

I’ll leave you with a (mercifully) briefer point by encouraging both research and self-reflection. Your research on a publisher should not begin and end with “Who is accepting pitches?”

Consider the fit of your project within their body of work.

Meet and connect with other creators who’ve worked with them and politely request their feedback.

Look at publisher’s company performance and makeup with resources such a Companies house or Endole. Do they appear financially stable? How large is their team? What other interests to their leadership team have?

Look at publisher’s websites and social media platforms, how are they marketing? How large is their reach? How much interaction do you see with their posts? How large is their portfolio?

Measure your own, time, resources, and reach against your potential publishers and consider objectively and, in quantifiable terms wherever you can, how you measure up. If you’re brining a sizable or active existing audience with you to a publisher this may enhance your ability to negotiate.

To wrap up I’ll say, that I hope the last, almost 5000 words *Jeez* have been of some value, whatever your experience of creating or publishing to date. I by no means consider myself an authority on anything so would be delighted if this sparks further conversation and discussion from others who may add more specific examples and considerations which may help others chasing the goal of having published work out in the wild.

I’ll return to one of my opening points that there are some fantastic publishers doing incredible work in the indie comic scene and making books possible that would otherwise never see the light of day. For indie creators, whether a publishing deal is a Holy Grail or a Poison Chalice will likely remain up to the individual and determined by how circumstances play out. If this helps just one person, take pause, consider their options and make an informed choice it will have been worth the effort.

1 note

·

View note

Note

Very cool of you to start this! I was wondering... as someone who would like to publish a traditional novel someday (romance, if that helps) and was wondering if you could outline the publication process for novels? It's a little intimidating for someone like me and I would really appreciate the clarity. Thank you!

Hi there, thank you so much! :) And okay, I’ll do my best to outline how it generally works:

Traditional Publishing

Step 1) Complete your novel.

Step 2) Edit and revise your novel to the best of your abilities! You only get one chance to impress an agent (the next step) and you want to start with your best foot forward. Do not send an incomplete or unpolished manuscript: it must be as close to the finished product as you can get on your own! If you feel you need help, shop it around to people you trust (friends or family, creative writing workshops, writing partners, mentors or professors, etc). Professional and freelance editors (like me!) are also always an option if you need an experienced second pair of eyes!

Step 3) Find agents whose work you love. The best way to do this is to go to your favorite novels (preferably in the genre you want to publish in), turn to the back of the book, and find the agent of that novel’s name in the “Acknowledgements/Thanks” section. Look them up and read carefully to see if your story fits the kind of work they read and are looking for.

Step 4) Write a query letter. This is possibly the most intimidating aspect of the publication process because many authors love to write fiction, but don’t love to write about themselves and their work. The query letter is essentially the marketing or elevator pitch to give an agent a preview of what to expect in your work (and is your chance to intrigue them). There’s a wealth of resources out there on how to write a query letter, and here are some of my favorites:

How to Write a Darn Good Query Letter

How to Write the Perfect Query Letter

Query Letters

Samples of Query Letters

The long and short of it is, query letters contain your book’s introduction and stats (what its word count is (), what its genre and title is), its summary (picture what its blurb would be on the back of the hardcover copy and write that), your credentials as an author, and why you’d like to work with that particular agent.

Some other tips: don’t let the letter extend beyond one page. Agents (and editors) appreciate conciseness, not least because they’re busy and it shows your skill as a writer when you condense important information into a small space. Don’t oversell your work. NEVER describe your book as “the next Harry Potter” or “the masterpiece of our time” or whatever. Let the agent decide that for themselves! But don’t undersell or self-deprecate, either (“you probably won’t be interested in this, but I thought I’d give it a shot...”). It can be hard to have confidence in your writing, especially when entering the pro arena, but you need to inspire an agent’s faith in you as much as in your work (without exaggerating or boasting!)

Step 5) Send your query letter and manuscript to the top 5 agents you’ve been looking at. Sending too many will be overwhelming (and many agents hate “simultaneous submissions,” where you send copies to multiple places at the same time) and sending too few would be putting all your eggs in one basket.

Be careful to read exactly how each agent would like to receive your manuscript! Some only accept physical copies in the mail, in manila envelopes; some only accept attachments by email; some only accept PDFs and not Word and vice-versa! If you don’t follow their submission guidelines, you often won’t get a second chance or a courtesy reminder.

Oh, and format your manuscript according to their instructions. If there are no specific instructions, it’s always best to have your novel in standard manuscript format. Shunn’s guide to story formatting is a bible in this industry, so following those guidelines will make you look professional. Please avoid kooky or unique fonts as well: you may think it helps you stand out, but speaking from experience, most agents/editors really hate this!

Step 6) Wait.

Some agents have a projected time of response to get back to you (“if we don’t get back to you within 8 weeks, we are declining to represent your work”) on their website. Some don’t, and you’ll just have to wait (sending a follow-up query 6-8 weeks after sending your manuscript can be reasonable unless their website asks you not to do this).

If those top 5 agent don’t get back to you (or decline to represent your book) don’t be discouraged! All the greatest writers of all time struggled to find their agents and publishers at first. J.K. Rowling suffered through “years” of rejection from agents before she finally found one to represent Harry Potter, and even after that was rejected by 12 publishers (many very rudely!) before someone wanted HP. So send your manuscript out to the next five and keep going!

Step 7) An agent wants your manuscript.

Ideally, they’re over-the-moon in love with it: you want an agent who’s passionate about your work and will shop it tirelessly to their connections in the publishing industry.

(I feel I should add: do not send your work to or proceed with any agent who wants to be paid to represent you, or who charges a fee to read your work! This is a scam! Like sports agents or real estate agents, literary agents only take a cut of the profits after they’ve sold your book to a publisher. (Usually around 15%, though this could be higher or lower depending on the agent). This way, they’re motivated to sell your book for the highest rate possible, because they only make money from it then, too! If they want you to pay them out-of-pocket for anything, be extremely suspicious!)

After you’ve met with your agent, agreed to work together, and signed a contract (always read these carefully or get a lawyer to look over them), your agent will probably give you some tips or requests to polish your manuscript up even further before sending your work out. After this is done, they’ll shop your manuscript to the publishers they think will be the best fit for it!

Step 8) An editor at a publishing house reads your manuscript and falls in love with it.

This is the dream! There will be some negotiation, and this is where your agent comes in: they will protect your rights and negotiate with the publisher on your behalf to get as high of a selling price for your novel as possible. The publisher will often pay you an advance (an initial lump sum for the book) and will then usually offer you a percentage of the first sales after tax (say 10%, though depending on your publishing history or type of book or a whole slew of factors, you may get a higher/lower percentage or none at all). Your agent will guide you through this process and explain everything, so I won’t get into much more detail beyond that.

Step 9) You accept the terms of agreement with a publisher, and the book goes to their editing team: AKA your new editor.

You will likely go through several months or even years of editing with your editor’s feedback. A good editor won’t change your vision of your work drastically, but you may have to rewrite whole sections of your book to improve pacing, cut out unnecessary plot lines, and etc. Be patient with this and be flexible: your work isn’t perfect (no one’s is, not even after publication) and your editor knows what they’re doing. However, you do also have power here and can push back if there’s something you feel extremely strongly about changing.

Step 10) Your book is on the way to publication.

Now it’s just a waiting game. Your agent (or you) might ask other authors to be advance readers for your edited manuscript: these are the people who give the quotes and blurbs on the back of the books--the ones with glowing praise!

Depending on the publishing house, you may get some input on the cover and design of your book, or you may not. Your agent/publisher may also talk to you about foreign translations and licensing, etc.!

Step 11) Your book is published!

It took a while, but you made it, and now your book has hit the shelves (or the Internet, or both). Not counting the time it takes to find an agent, the whole process takes a minimum of a year to... well, I won’t regale you with the authors who took ten, fifteen, twenty years to get to publication, but needless to say, it’s a slow-moving process.

Getting an agent is arguably the hardest part (once you get one, they really do most of the work for you), and if you’d like to skip this hurdle, there’s always chancing submitting your work straight to the publishers. However, for the big publishing houses, this option has an extremely low chance of success, to put it bluntly. Unless you’re submitting to a very small independent publisher or what’s known as a “vanity press”, almost all major publishing houses nowadays don’t even look at books without agents, and those submissions get lost in slush pile hell. Agents are the first barrier to publication, and once they’ve vetted your book and found potential in it, publishing houses are more comfortable with reading a manuscript that they’re more sure won’t “waste their time.”

Of course, if you don’t want to split your profits with an agent, there’s always self-publishing! But since this post is getting so long, I figure I’ll talk about that another time. Thanks for the great question, and I hope this helped! (And good luck with your romance novel(s)!)

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

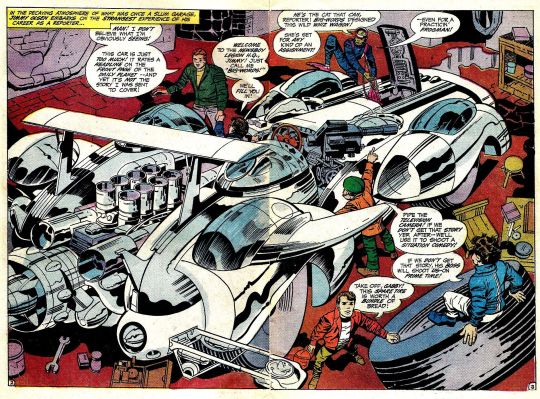

Jimmy Olsen, Superman's Pal, Brings Back the Newsboy Legion!

SUPERMAN’S PAL, JIMMY OLSEN #133 OCTOBER 1970 BY JACK KIRBY, AL PLASTINO AND VINCE COLLETTA

SYNOPSIS (FROM DC WIKIA)

Jimmy Olsen is paired with the new Newsboy Legion, the sons of the original boy heroes plus Flippa-Dippa, a newcomer, to investigate the Wild Area, a strange community outside of Metropolis.

The boys are given a super-vehicle called the Whiz Wagon for transport. When Clark Kent shows concern for Jimmy, Morgan Edge, owner of Galaxy Broadcasting and the new owner of the Daily Planet, secretly orders a criminal organization called Inter-Gang to kill him. But Kent survives the attempt, and later hooks up with Jimmy and the Newsboy Legion in the Wild Area.

The youths have met the Outsiders, a tribe of young people who live in a super-scientific commune called Habitat, and have won leadership of the Outsiders' gang of motorcyclists. Jimmy and company go off in search of a mysterious goal called the Mountain of Judgment, and warn Superman not to stop them.

THE BRONZE AGE OF COMICS

The Bronze Age retained many of the conventions of the Silver Age, with traditional superhero titles remaining the mainstay of the industry. However, a return of darker plot elements and story lines more related to relevant social issues, such as racism, drug use, alcoholism, urban poverty, and environmental pollution, began to flourish during the period, prefiguring the later Modern Age of Comic Books.

There is no one single event that can be said to herald the beginning of the Bronze Age. Instead, a number of events at the beginning of the 1970s, taken together, can be seen as a shift away from the tone of comics in the previous decade.

One such event was the April 1970 issue of Green Lantern, which added Green Arrow as a title character. The series, written by Denny O'Neil and penciled by Neal Adams, focused on "relevance" as Green Lantern was exposed to poverty and experienced self-doubt.

Later in 1970, Jack Kirby left Marvel Comics, ending arguably the most important creative partnership of the Silver Age (with Stan Lee). Kirby then turned to DC, where he created The Fourth World series of titles starting with Superman's Pal Jimmy Olsen #133 in October 1970. Also in 1970 Mort Weisinger, the long term editor of the various Superman titles, retired to be replaced by Julius Schwartz. Schwartz set about toning down some of the more fanciful aspects of the Weisinger era, removing most Kryptonite from continuity and scaling back Superman's nigh-infinite—by then—powers, which was done by veteran Superman artist Curt Swan together with groundbreaking author Denny O'Neil.

The beginning of the Bronze Age coincided with the end of the careers of many of the veteran writers and artists of the time, or their promotion to management positions and retirement from regular writing or drawing, and their replacement with a younger generation of editors and creators, many of whom knew each other from their experiences in comic book fan conventions and publications. At the same time, publishers began the era by scaling back on their super-hero publications, canceling many of the weaker-selling titles, and experimenting with other genres such as horror and sword-and-sorcery.

The era also encompassed major changes in the distribution of and audience for comic books. Over time, the medium shifted from cheap mass market products sold at newsstands to a more expensive product sold at specialty comic book shops and aimed at a smaller, core audience of fans. The shift in distribution allowed many small-print publishers to enter the market, changing the medium from one dominated by a few large publishers to a more diverse and eclectic range of books.

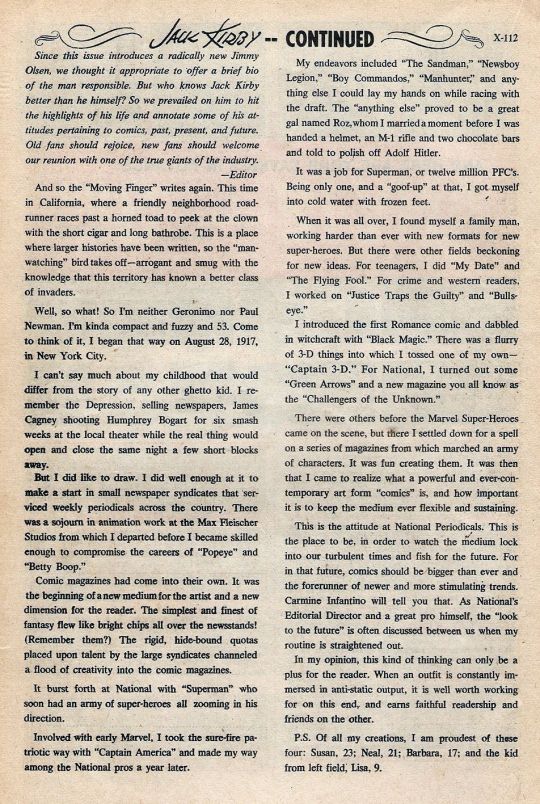

JACK KIRBY

In 1968 and 1969, Joe Simon was involved in litigation with Marvel Comics over the ownership of Captain America, initiated by Marvel after Simon registered the copyright renewal for Captain America in his own name. According to Simon, Kirby agreed to support the company in the litigation and, as part of a deal Kirby made with publisher Martin Goodman, signed over to Marvel any rights he might have had to the character.

At this same time, Kirby grew increasingly dissatisfied with working at Marvel, for reasons Kirby biographer Mark Evanier has suggested include resentment over Lee's media prominence, a lack of full creative control, anger over breaches of perceived promises by publisher Martin Goodman, and frustration over Marvel's failure to credit him specifically for his story plotting and for his character creations and co-creations. He began to both write and draw some secondary features for Marvel, such as "The Inhumans" in Amazing Adventures volume two, as well as horror stories for the anthology title Chamber of Darkness, and received full credit for doing so; but in 1970, Kirby was presented with a contract that included such unfavorable terms as a prohibition against legal retaliation. When Kirby objected, the management refused to negotiate any contract changes. Kirby, although he was earning $35,000 a year freelancing for the company, subsequently left Marvel in 1970 for rival DC Comics, under editorial director Carmine Infantino.

Kirby spent nearly two years negotiating a deal to move to DC Comics, where in late 1970 he signed a three-year contract with an option for two additional years. He produced a series of interlinked titles under the blanket sobriquet "The Fourth World", which included a trilogy of new titles — New Gods, Mister Miracle, and The Forever People — as well as the extant Superman's Pal Jimmy Olsen. Kirby picked the latter book because the series was without a stable creative team and he did not want to cost anyone a job. The three books Kirby originated dealt with aspects of mythology he'd previously touched upon in Thor.

The New Gods would establish this new mythos, while in The Forever People Kirby would attempt to mythologize the lives of the young people he observed around him. The third book, Mister Miracle was more of a personal myth. The title character was an escape artist, which Mark Evanier suggests Kirby channeled his feelings of constraint into. Mister Miracle's wife was based in character on Kirby's wife Roz, and he even caricatured Stan Lee within the pages of the book as Funky Flashman. The central villain of the Fourth World series, Darkseid, and some of the Fourth World concepts, appeared in Jimmy Olsen before the launch of the other Fourth World books, giving the new titles greater exposure to potential buyers. The Superman figures and Jimmy Olsen faces drawn by Kirby were redrawn by Al Plastino, and later by Murphy Anderson.

Kirby later produced other DC series such as OMAC, Kamandi, The Demon, and Kobra, and worked on such extant features as "The Losers" in Our Fighting Forces. Together with former partner Joe Simon for one last time, he worked on a new incarnation of the Sandman. Kirby produced three issues of the 1st Issue Special anthology series and created Atlas The Great, a new Manhunter, and the Dingbats of Danger Street.

Kirby's production assistant of the time, Mark Evanier, recounted that DC's policies of the era were not in sync with Kirby's creative impulses, and that he was often forced to work on characters and projects he did not like. Meanwhile, some artists at DC did not want Kirby there, as he threatened their positions in the company; they also had bad blood from previous competition with Marvel and legal problems with him. Since he was working from California, they were able to undermine his work through redesigns in the New York office.

REVIEW

If you are a ninenties creature like me, you remember all these concepts very well, because they came back in the form of Cadmus in the superman titles of the “triangle” era. This is proof that Kirby left a big legacy on more than one company. It is sometimes hard to tell where Kirby starts and where other writers come in. It is hard to tell on his Marvel work at least (and Stan Lee would often take credit for Kirby’s work). So the Fourth World is a good place to check on the real Jack Kirby. Away from Joe Simon, away from Stan Lee.

Now, about this issue. As I said, I knew most of these things from the 90′s Superman titles (that was also the last time Jimmy Olsen mattered). But I have to imagine what it was like to new readers... Jimmy Olsen readers in particular, that a few months ago were reading about Superman trying to prevent Jimmy (an adult) from being adopted. I also have to have in mind that comic-book readers were probably very aware of who Jack Kirby was. The sixties were pretty much dominated by Marvel, and a big part of that success was because of Kirby. But, as I said before, Stan Lee would take the media and take credit for everything. So I am not sure how aware casual readers were with Jack Kirby.

If they weren’t, by this issue they probably were, as DC did a lot of fanfare about the fact that Kirby was coming to DC. Some people compared Bendis coming to DC to this period of time in particular. While there are similarities, it is too early too judge Bendis legacy at this point in time.

The story in this issue is ok. There are a lot of characters and plots being introduced. It’s the first appearance of Morgan Edge, the Wild Area, the Outsiders, the Newsboy Legion (Junior) and other concepts. It is important to remark that this Newsboy Legion is not the golden age version of that group. They are the sons of the originals (and they look pretty much the same... and dress the same). Flip is a bit weird, though. I am pretty sure he doesn’t need the scuba kit on all the time. I will be reviewing the original Newsboy Legion in the golden age reviews.

The art is better than the usual Kirby style, but as it was said above, Al Plastino redrew Superman and Jimmy’s faces. This was common practice at DC, as they didn’t want their most emblematic characters changing too much from issue to issue.

I give this issue a score of 8

#jack kirby#al plastino#fourth world#vince colletta#gaspar saladino#bronze age#dc comics#1970#jimmy olsen#superman's pal jimmy olsen#newsboy legion#comics#review

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Model Portfolio Photography Sydney - What Is It and Do You Really Need One to Be a Model?

So you are thinking of getting into modeling of some sort for the first time but have heard people talk about a Model Portfolio and not sure if you should have one. Furthermore, what are it and more importantly what's in it?

What is a portfolio?

A Portfolio is a collection of your best professionally taken pictures either in printed format in a book or folder, on a CD or DVD disc or more commonly these days on-line in digital format. As time goes by it will also contain "Tear-Sheets" of your best work which are pages taken from published work (Magazine's etc) from previous assignments you've done.

Do you need a Model Portfolio to get work?

The easiest answer to that is no, you don't but a portfolio is like a CV in any other industry in that you don't necessarily NEED one to get a job as let's say a Receptionist or a Shop Assistant but it's always best to have one just in case anybody asks to see what you've been doing or what you are capable of doing.

Agency Portfolio

Be aware of scams and agencies that tend to rip off inexperienced new models. If they want to charge you for having your portfolio done in order to sign up with their agency then it may not be the right one for you.

Independent or Freelance Model Portfolio

If you are thinking about being an independent or freelance model then you will have to build or make up your own Model Portfolio Photography Sydney but you can always negotiate your way to getting this done for free.

A lot of Fashion Photography and Portrait Photography studios may agree to take your pictures for no fee in return for your time.

You can expect a set of images from the shoot on a CD or more likely in a downloadable format and maybe even a set of prints if you are lucky or good at negotiating.

Don't expect a full portfolio to be produced from this one shoot but you will receive a good few select shots from the photographer to help build your collection.

Large Agency Portfolio

If you are intending to go with one of the country's larger or better agencies then you may not need to have a Model Portfolio already. All you really need are four simple pictures of you against a light-colored plain background or wall.

You will need to send them:

· One full length shot (two piece bikini for girls and shorts for guys)

· One half-length body shot (top half - just in case you were wondering)

· Head shot - smiling

· Head shot - not smiling

Please note: All shots should be natural, with no makeup on and your hair away from your face and don't try to do any poses as that's not needed at this point in time. Please don't send in your old school photographs or family photos no matter how good you look on them.

Most of them will have a facility for you to upload your photographs to their web site and one of their experienced members of staff who is known as a 'Scout' will view them and contact you if they want to take you on and sign you up.

You will then be invited to have your pictures taken by one of their own Professional Fashion Photographers Sydney for free.

Prints versus Digital

Due to costs and ease of time, having your portfolio is a big advantage and I can't recommend it highly enough so long as you have them hosted on one of the bigger more reputable modeling web sites..

However, there is nothing better than seeing a well taken large print of a model that's in a collection in a portfolio case. Any great salesman will tell you that if you can put something in the "decision maker's" hand then you are half way to making the sale or in a model's case, half way to getting the booking.

Mostly, because of the digital age and on-line facilities a portfolio of prints is more there for personal vanity.

Who should have a Model Portfolio?

· Fashion Models

· Glamour Models

· Facial Models

· Body Part Models

· Child Models

· Teen Models

· Mature Models

· Commercial Models

· Catalogue Models

· Showroom/Promotional/Exhibition Models

· Fitness Models

· Some Actors & Actresses

If you do your research on the industry and your photographers then putting together a model portfolio should be fairly easy and fun to do.

And if you found this article interesting then you might like to look at our information Fashion Photography Perth and Portrait Photography which should give you some related tips and direction to get you started.

Chris Huzzard Studios is a studio providing best photographic studio in Perth, Australia that have a great facilities, confidential, quality services. They are based in Perth [http://chrishuzzardstudios.com/], where you will find a huge stock of variety of studios. If you are interested in a full on photography project like Modelling Photography, Professional Fashion Photographers or any host industry events, it provides you the best possible solution. Do contact at +61 415 388 112 for more details.

#Modelling Photography Sydney#Commercial Photographer Perth#Street Photography Model Perth#Model Portfolio Photography Sydney#Commercial Photography Sydney#Cheap Fashion Photographer Sydney#Professional Fashion Photographers Sydney#Fashion Photography Perth

1 note

·

View note

Text

Who Should You Hire to Build Your Web Startup? (Tips for Non-Technical Tech Entrepreneurs)

I actually get asked this question constantly, usually by friends who are looking to build a website or tech startup for the first time, who have an idea but don’t know how to actually create it. And if you are launching a web startup for the first time, then it’s probably one of the most important questions you’ll have to answer for yourself before you begin, as it can largely determine:

A substantial portion of your costs and how much money you raise

The quality of your product

How much maintenance you’ll need down the road and when you rebuild

How much equity you give up

Your success or failure

So here are a few of my own personal FAQs when it comes to building a web business for the first time, specifically in terms of finding talent and estimating its costs.

Should I hire a full-time programmer, a web development company or an independent contractor?

Independent contractors: they aren’t your employees and usually do freelance work on their own.

Pros: schedules and relationships with contractors are usually more flexible than those with full-time employees because you can start and stop projects and adjust hourly schedules as needed. This flexibility also implies you won’t get locked into the long-term cash outflow of an employee salary. Additionally, you don’t have to worry about employment liabilities with contractors (more on that later). Lastly, contractors are generally cheap in terms of equity because they work for cash.

Cons: my biggest problem with contractors is that they want to get compensated for their time and unfortunately not for their results. That usually means they have more incentive to take a longer to do any given job and additionally that they’ll do the minimum amount of work to earn their paycheck. I’m not trying to imply that contractors aren’t honest, because I’ve enjoyed working with countless contractors, but I am saying that they they’re first priority is getting paid while your first priority is getting a great product. It’s understandable because they have no long-term, vested interest in your company the way an employee does. Lastly, an individual contractor will require a lot of leadership and technical involvement on your part because you most likely will be the project and product lead if you have a small team.

Recommendation: remember, contractors usually want to get compensated for their time, so you’ve got to be crystal clear with your expectations up front. The more questions you can eliminate in the beginning the less likely the contractor is to say she didn’t understand what she was doing, and the less likely you’ll get sucked into a never-ending contract because you kept going through multiple iterations to fix constant mistakes. This alone can kill your business by pushing you over your expected budget. In the beginning, draft a comprehensive explanation of exactly what you want (a “requirements” document) and if possible provide visual mockups (I like to use a tool called Balsamiq – it’s easier than pen and paper and much more efficient). Then hold a meeting to discuss those requirements in detail, before you begin. The purpose of this meeting is to align your expectations and agree on a timeline. For one of my projects, I personally spent about 10 hours in a room with a contractor discussing requirements and negotiating a price before we began – it paid big dividends down the road. Once you do start, check in regularly – I’d recommend daily. I also highly recommend that you get a fixed contract with contractors whenever possible. This puts a cap on your spending and ensures that you’re paying for results and not time. Once you’ve taken those steps summarize everything in a legal contract, ideally yours. It’s usually difficult getting developers to agree to fixed-rate contracts, but it's worth putting in the extra time searching for someone who will, and the more detailed your requirements and mockups are, the more likely you’ll get your fixed rate. In my experience, contractors are great for doing quick bug fixes and straightforward feature builds on an ad hoc basis, but I’d hesitate to pay a contractor to build your site from scratch – unless you know exactly what you want, understand the technologies being used and are willing to put in the time as a manager.

Web development companies: web dev companies are teams of contractors - you hire the company, and it assigns its contractors to your project.

Pros: hiring a web dev company generally affords the same benefits of hiring individual contractors, plus a few more. One big benefit is the higher (hopefully) relative quality of work since you can presume the company has vetted all their employees and works according to industry best practices. In short, the work tends to be a lot more professional. A related benefit then is that of management – while you should expect to keep regular tabs on their work, the web dev company will usually provide their own product or project manager who will ensure that the contract stays on schedule so you don’t have to spend as much of your time doing it. This frees your time for strategy and operations.

Cons: this is arguably the most expensive (cash-wise) option, but you are paying a premium for all the above-mentioned pros. If you hire a reputable dev firm, you probably won’t spend under $10-$20K per month. In fact it's not unheard of to pay >$20K / month for a good dev firm. They’re also not going to be as flexible as working with an individual. They’ll want longer (usually a month at least) contracts and usually will want to use their own legal contracts instead of yours.

Recommendation: If you can afford the cost and you don’t want to be locked into a long-term employment contract yet, this is probably your best option if it’s a complicated project and / or if you are building your first product from the ground up, and particularly if you don’t feel comfortable having to actively manage developers yourself. Before approaching a web dev company, put together your detailed requirements and mockups – in fact, you should always do this no matter who you hire. Then get quotes from several different development companies and compare the expected quality and cost of them all. Make a spread sheet and do a cost-benefit analysis. Also, use your own legal contract if possible and try to lock down that fixed rate. Look for web dev companies like Happy Fun Corp who have extremely talented, communicative and professional engineers, world-class client bases, and founding teams with successful track records running their own tech startups. And of course, look at their prior work – odds are, if you don’t like the websites they’ve built in the past, you won’t like the site they build for you either.

Full-time employees: employees are dedicated, formal members of your team and usually work on a longer-term basis than contractors.

Pros: the greatest benefit of hiring a programmer as a full-time employee is alignment of interests. Full-time employees have a vested interest in your company, both in terms of the time they devote and the quality of their work because they share in the success and failure of the company. In my experience, employees do a far greater job than independent contractors and are much more likely to go the extra mile when doing both what is asked of them and also when coming up with new ideas and features on their own – this is the innovation factor. Shared interest is especially strong if your employee has real ownership in your company (equity, options, etc.). As a general rule, the younger your company is the more equity you should expect to award, which is true because anyone joining your team in its early stages is taking a major career risk by coming on board and must be compensated for that risk. In that same vein, the more equity you award the less cash you can likely expect to pay, implying that if the equity is great enough you can save a lot of cash on this option relative to what you’d pay a contractor or development company. In some cases, this can be a cash-free option even. Assuming you are compensating with both, however, I’d expect to pay an annual salary of $60 - $150K (and in several cases more), plus equity of between 2% - 30%. It’s all negotiable, and your final terms will depend on how talented the person is, how much you need him and what your budget is among many other variables. On a side note, having a dedicated tech team, even one person, actually helps your marketability to VCs and angels as well as ensures your business stays lean in its ability to constantly iterate the technology – this is the name of the game in startups.

Cons: hiring a full-time programmer is probably the most difficult option of the three because of the lengthy diligence required to identify and then sell the best candidate on the job, and then because of the enormous risk you are taking by placing so much faith in any given hire. In a startup, every single person on your team is a critical component, and making the wrong hire can literally sink your ship, especially when that person is building your product. In terms of compensation, if you’re paying a salary this option will lock you into a longer term cash outflow and as mentioned will also usually cost you some equity. Additionally, with full-time employees you as the business owner must consider all the legal implications such as worker’s compensation, tax liabilities, unemployment insurance benefits and others. Similar to hiring individual contractors, employees must be led, so you’ll have to devote a substantial amount of time to either hiring someone who understands both the minute details and the big picture, or you’ll have to play an active role in technology decisions.

Recommendation: If you’re looking to build a complete product and you need dedicated, long-term support then hire a full-time programmer as an employee. Because this is a long-term decision, you must identify someone that can take full leadership over the technology aspect of the business and whose competency you absolutely trust. This person will likely be your lead programmer or CTO if you have no one else. Finding truly great talent is difficult enough, but to retain it you have to compensate for it. If you don’t want to give up equity, then expect to award a competitive, if not higher-than-average, salary. If you have no cash or are trying to save it then expect to award a big chunk of equity – it’s a tradeoff, but it’s worth it. Remember, the benefit of hiring employees is alignment of interests, and if you want someone to go above and beyond and work those 18-hour days alongside you, you’ve got to pay for it. In my opinion, award the equity and be generous with key employees (which is absolutely not to say be careless). Make the employee vest over time, meaning the equity is only awarded upon completion of various milestones. If you’re absolutely opposed to allocating equity – and I know some who are – consider it this way: in the beginning one of the biggest challenges you’ll face is that of raising enough funding to build your product; raising funds usually implies you’ll have to give up equity to an investor anyway, who’ll then give you cash, which in turn you’ll pay to a programmer. What I’m trying to say is if you award the equity directly to the employee, you either don’t have to raise as much investor cash to begin with, or you can build a product first and then raise cash on better equity terms later on in the game.

Which programming language is best?

This is a common question you’ll face when you start interviewing people because many of them will be proficient in different programming languages. I’ll refrain from listing all the different languages and their merits because as a non-technical person you won’t necessarily understand all the differences and nuances enough to really decide on your own anyway. I didn’t when I began. Instead, I’ll point out a couple considerations that should help you make an educated business decision, which you can do.

Consider competency: strongly consider building your site in the language that your best candidate wishes to use.