#Hugh Despenser

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Isabella of France VS Hugh Despenser

My cat modeled for all four historical figures — simply because I don’t know what these people looked like

Left background figure (wearing armour and waving pom poms) Roger Mortimer, Isabella’s alleged lover

Left foreground figure (wearing a red dress with armour and holding a pole axe) Isabella of France

Right foreground figure (wearing a hat and holding a sword) Hugh Despenser, Edward II’s alleged lover

Right background figure (wearing kingly attire and shedding tears) Edward II, Isabella’s husband

I found this particular fragment of history fascinating because it showed us the ruthless ambition of both women and queer men in medieval times, a contrast to society’s common perception of them from that era. This manuscript by the French chronicler Jean De Wavrin is not only a gruesome retelling of this event, but also a campy propaganda ; Have I not seen this manuscript from an exhibition, I’d never know these people existed, it also shows that historical women and queer men were sidelined in collective consciousness.

I’d like to read Alison Weir’s She-wolf of France to know more.

Manuscript by Jean De Wavrin from the “Medieval women” exhibition at the British Library.

#also an excuse to draw my cat again#didn’t bring him to the UK#i miss him so much#medieval manuscript#medieval history#isabella of france#Hugh Despenser#lol#edward ii#british history#my art#illustration#if an UAL degree can’t get me a good job#I can at least draw cats for a living#cat art#cats#damn

0 notes

Text

Also reading her household book does confirm that Isabella of France directly corresponded with Hugh le Despenser the elder during the 1310's...Much to think about...

#we really don't think or talk enough about the relationship between those two#isabella most likely saw him as a positive figure in her life for a goood chunk of her reign#he was one of the person who had organised her marriage and one of the first english nobleman she would have met before she even left franc#he was also one of her husband's closest ally AND the father-in-law of a woman with whom she had a personal relationship for a long time#so it's very hard for me to believe that she didn't had mostly positive feelings about him for years#and then things went *so* bad that she ended up litterally executing him and feeding his corpse to the dogs#the evolution of this dynamic is just really fascinating for me tbh#isabella of france#hugh le despenser the elder#we don't talk about this dude enough in general btw#as much as i love the son the dad will always have a very specific place in my heart

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kings and Their Lovers

Male Kings and Their Homoromantic or Erotic Relationships from Antiquity to Modern Times History offers numerous examples of male rulers who had homoromantic or erotic relationships with other men. These connections were often complex and influenced by cultural, societal, and personal factors. Here are some remarkable examples:

Antiquity

Alexander the Great (356–323 BC) The Macedonian king and famous conqueror had a particularly close relationship with Hephaestion, his childhood friend and confidant. Plutarch described Hephaestion as "Alexander's lover." After Hephaestion's death, Alexander was inconsolable and ordered a nationwide mourning. The Persian eunuch Bagoas is also mentioned in ancient sources as Alexander's lover.

Emperor Hadrian (76–138 AD) The Roman emperor is known for his passionate relationship with the young Greek Antinous. When Antinous drowned in the Nile, Hadrian was devastated. He had his lover deified, founded the city of Antinoopolis, and erected statues of Antinous throughout the empire. These actions testify to Hadrian's deep affection and grief.

Middle Ages

Richard the Lionheart (1157–1199) Richard I of England had a close relationship with Philip II of France. Contemporary chroniclers described how the two kings "ate from the same table and drank from the same cup every night" and "slept in the same bed." Although the exact nature of their relationship remains disputed, such reports suggest a very intimate connection.

Edward II of England (1284–1327) Edward II had an intense relationship with Piers Gaveston, which chroniclers of the time described as excessively intimate. Later, he developed a similarly close relationship with Hugh Despenser the Younger. These connections led to political tensions and ultimately contributed to Edward's deposition.

Modern Times

James I of England (1566–1625) James, also known as James VI of Scotland, had several close relationships with men. Particularly notable was his connection with George Villiers, the Duke of Buckingham. In letters, James called Villiers "my sweet child and wife" and "my dear Venus boy." This correspondence indicates a passionate and intimate relationship.

Louis XIV of France (1638–1715) Although the Sun King is primarily known for his female mistresses, there are indications of intimate relationships with men. The Duke of Saint-Simon reported in his memoirs of several homosexual affairs at court, including one between Louis and his brother Philippe, Duke of Orléans.

Frederick the Great of Prussia (1712–1786) Frederick had close relationships with several men, particularly Hans Hermann von Katte in his youth. Although Frederick married, the marriage remained childless and distant. Instead, he surrounded himself with a circle of close male friends and confidants.

Ludwig II of Bavaria (1845–1886) Known as the "Fairy Tale King," Ludwig II had close and presumably romantic relationships with several men. Particularly well-known are his connections to Richard Hornig, his stable master, and Paul von Thurn und Taxis. Ludwig's homosexuality was an open secret during his lifetime and contributed to the accusations that led to his dethronement.

Modern Era

Tsar Nicholas II of Russia (1868–1918) Although later married, the last Russian Tsar had a close relationship as a young man with his cousin, Prince Nicholas of Greece. In letters, he described their "special friendship" and the "wonderful nights" they spent together.

These examples show that same-sex relationships among rulers were not uncommon. The nature and perception of such connections varied greatly depending on the cultural and historical context. While some relationships were lived relatively openly, others remained hidden due to societal norms and political implications or were only hinted at in documentation.

It is important to note that modern concepts of sexual orientation and identity cannot be directly applied to historical figures. Many of these rulers would not have identified themselves as homosexual or bisexual, as these terms did not exist in their time. Their relationships must be understood in the context of their respective culture and time.

Nevertheless, these historical examples offer important insights into the diversity of human relationships and show that same-sex love and affection existed even at the highest levels of power.

Text supported by GPT-4o, Claude AI

Image generated with SD1.5. Overworked with inpainting (SD1.5/SDXL) and composing.

#History#LGBTQHistory#AlexanderTheGreat#Hephaestion#Hadrian#Antinous#RichardTheLionheart#EdwardII#JamesI#LouisXIV#FrederickTheGreat#LudwigII#NicholasII#QueerHistory#SameSexRelationships#Monarchs#RoyalLovers#HistoricalFigures#HumanRelationships

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

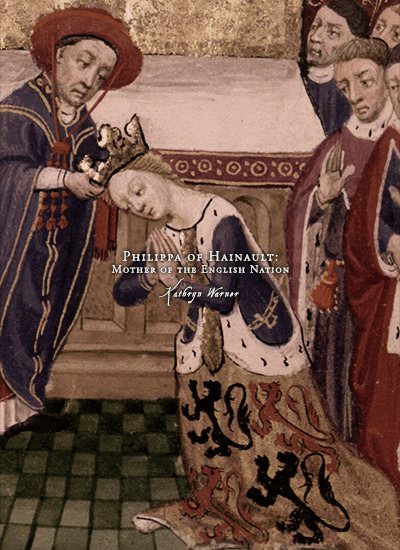

Favorite History Books || Philippa of Hainault: Mother of the English Nation by Kathryn Warner ★★★★☆

Edward III, king of England, was fifteen years old at the time of his wedding in York on 24 or 25 January 1328, and Philippa of Hainault, his bride, was perhaps fifteen months or so younger and, according to one chronicler, about to turn fourteen. Although their marriage was to endure for more than four decades and would prove to be a most happy and successful one that produced a dozen children, it could hardly have begun in a more unromantic fashion. Edward’s mother Queen Isabella had arranged her son’s marriage with Philippa’s father Willem, count of Hainault in 1326 so that he would provide ships and mercenaries for her to invade her husband Edward II’s kingdom in order to bring down the man she loathed above all others, Edward II’s adored chamberlain and perhaps lover Hugh Despenser the Younger. Just a month before his wedding to Philippa, Edward III had attended the funeral of his deposed, disgraced and possibly murdered father, the former king, at St Peter’s Abbey in Gloucestershire. Whether intentionally or not, Edward III and Philippa of Hainault married on his parents’ twentieth wedding anniversary, and on the first anniversary of the young Edward’s reign as king of England. Philippa of Hainault accompanied her husband abroad on many of his military and diplomatic missions; the couple hated to be apart for long and spent as much time together as they possibly could. Despite Philippa’s decades-long marriage to one of medieval England’s most famous and successful kings, there has only ever been one full-length biography of her, published by Blanche Christabel Hardy in 1910 and titled Philippa of Hainault and Her Times. In addition, two chapters in Agnes Strickland’s nineteenth-century work The Lives of the Queens of England cover the basics of Philippa’s life, and Lisa Benz St John’s 2012 book Three Medieval Queens examines the lives of Philippa and her two predecessors as queen of England.

#litedit#historyedit#house of plantagenet#philippa of hainaut#medieval#french history#belgian history#english history#european history#women's history#history#history books#nanshe's graphics

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

I fully changed my mind btw

Why are HR people the most annoying fuckers on the face of the Earth?

#all ive got to say is that first impression are not everything#king edward ii hated hugh le despenser the younger for decades and they ended up in a passionate obsessive love affair so you know..#not that i want to have a love affair with this woman but you get my point#anyway i actually care a lot about this job so i probably won't talk shit about it on tumblr tbh#tho i did checked and it's not that easy to associate me to this blog by name but still i've got selfies on here so yeah

6 notes

·

View notes

Note

Do you think Isabella of France has always hoped to reconcile with Edward II? Does she consider herself a hero who saved the king?

I'm glad you asked what I think because the reality is that we're never going to know what Isabella of France really thought and felt during her lifetime, even during such a famous and widely discussed event such as the events leading up to Edward II's deposition. Any attempt to answer this draws on speculation and is often filtered through our "lenses" - the narratives we want to tell, our biases, our reactions.

Your second question is is easier to answer so I'll deal with it first. The narratives around Isabella's invasion of England initially depicted her as a saviour, stepping in to save the king, but more importantly, the realm from the corrupt influence and rule of the Despensers. How much Isabella believed in this narrative is unknown. Following Edward's deposition, her dower was restored at an unprecedented and extraordinary 20,000 marks p.a. and, given Isabella's level of influence at the time, it is likely she had some say in the granting of this income. It is possible that Isabella felt this is what she had earned for "saving" the kingdom from the Despensers. Obviously, we don't know what she was really thinking and this is just supposition. Isabella may have viewed her saviour status cynically or doubtfully, while her dower may be more about the fact that she was the de facto ruler of England than her own greed or a reward for seeing off the Despensers.

As to your first question - whether she hoped to reconcile - it's much, much harder to answer.

No one knows what she was hoping for, we can only speculate about her feelings and unfortunately, we're hampered by a limited about of information about Isabella's actions. Some historians have argued that Isabella had given up on her marriage and perhaps even manipulated Edward into sending her as his ambassador to France in 1325, suggesting she was already plotting his downfall then. Traditionally, it has been assumed that Isabella had given up on their marriage when she refused return to Edward while on embassy in France and it has been largely been considered unthinkable that Isabella would countenance a return to Edward as plans developed for what would become the invasion that led to Edward's deposition.

However, and the reason I suspect you sent me this ask, Kathryn Warner has argued that Isabella was willing to return to Edward until quite late in the process. For Warner, a letter Isabella wrote to the Archbishop of Canterbury is proof that Isabella wanted to reconcile with Edward and only had issues with the Despensers:

She told him that Hugh Despenser the Younger ‘wished to dishonour us as much as he could’ and that she had hidden her dislike of him for a long time in order to escape danger. She explicitly stated later in the letter that she meant danger to her own life, this being the reason why she did not dare to return to ‘the company of our said lord’, i.e. Edward. Isabella wrote that her inability to return to her husband without putting herself in mortal peril caused her such serious distress that she could write no more of it. The queen also told the archbishop that she wished above all else, after God and the salvation of her soul, to return to Edward’s company and to live and die there, and called her husband ‘our very dear and very sweet lord and friend’ (nostre treschier et tresdouche seignur et amy). There is no real reason to suppose that Isabella was lying, and the description of Edward II as her ‘very dear and very sweet lord and friend’ is most unconventional – the conventional way to refer to one’s husband was merely ‘our very dear lord’ – and speaks to her strong feelings for him.

Warner goes on to claim that assumptions that Isabella was not telling the truth are based on the assumption that Isabella was already having an affair with Roger Mortimer and had chosen him over Edward. I don't think that's an entirely fair assessment and am far more sceptical of the letter.

Firstly, as @shredsandpatches said to me, we should be cautious of taking correspondence arising from highly fraught political situations at face value, particularly when we know that this was not a private communication. Warner claims on her blog that Isabella was "too pious" to lie to the Archbishop of Canterbury but, besides this being something we don't know, the letter was political correspondence - perhaps even a piece of political theatre - that Isabella knew would not remain private or secret. It was not a private conversation, much less anything said during the sacrament of confession, where Isabella would feel to unburden her innermost thoughts.

Secondly, Isabella was an astute and intelligent woman - we know this because she was trusted by Edward to conduct complex diplomatic negotiations with the French king and achieved some success, for example. It would be reasonable to assume that she was aware of and likely employing the "evil counsellors" topos, where criticisms of the king were couched in criticisms of his counsellors rather the king himself. It would also be reasonable to assume that Isabella knew that her behaviour was already transgressive and subversive and so couched her defiance in terms that made it clear that she had been forced to this extreme, but should the problem be fixed, she would return to being an obedient and dutiful wife and queen. It may also mean that where her "unconventional" reference to Edward as her "our very dear and very sweet lord and friend" may well have been deliberately used as a way to downplay her subversive, unwifely behaviour rather than being an accurate indicator of her feelings for Edward.

Thirdly, however Hugh Despenser the Younger had dishonoured Isabella, Edward had, at the very least, let it happen and Isabella very likely knew that (the "evil counsellors" rhetoric makes it possible that Edward had been a more active participant in Isabella's mistreatment than her letter may suggest). We should be suspicious of Isabella's narrative here - that Despenser was the sole problem in her marriage and that she merely wished to return her to dear, sweet husband. It is unlikely she was so stupid to believe Despenser had been puppeteering Edward's actions the entire time and Edward had been unaware of it, nor so spineless to forgive Edward for his part in her "dishonour".

(This is what I mean by lens. Warner's desire to rescue Edward from the charge of being a bad husband, amongst other smears, is apparent when one visits her blog or reads her books. This desire clearly impacts how she reads Isabella's letter as a straightforward revelation of Isabella's true feelings. I don't pretend that I am objective here, either - I dislike the way Warner characterises Isabella and my readings are resistant to her conclusions on Isabella. I don't, however, necessarily believe Isabella had an affair with Roger Mortimer (see here for more) so my interpretation of Isabella's letter is not based off the thought Isabella was already in love with Mortimer.)

Warner also cites an accusation made in the November 1330 parliament where it was claimed that Isabella - in the midst of plans for what would become the invasion of England and Edward's deposition - expressed a desire to return to Edward, despite the fact he had refused to dismiss the Despensers, but was told by Mortimer that "he" (it is unclear whether Mortimer meant himself or Edward) would kill her if she did. Therefore, Isabella was still prepared to return to Edward, in spite of his refusal to meet her one demand, but was prevented by Mortimer. Again, I'm sceptical. The allegation did not surface in a neutral environment but in the same parliament that resulted in Mortimer's execution for treason. It seems likely the accusation was made, in part, to cast Mortimer as the evil counsellor who had the queen astray and thus truly to blame.

Isabella did send Edward gifts and letters after his deposition, which may suggest some lingering fondness - or may, indeed, show Isabella keeping up appearances. In April 1327, Isabella apparently declared she was prepared and willing to see Edward again, only for the council to refuse permission. Again, it's probably good to be sceptical that Isabella was entirely genuine in this declaration. If Isabella was as powerful and influential as generally accepted, it's hard to see why the council's decision would have stopped her if she truly wanted to see Edward again. It may well have been a case of political posturing with Isabella announcing her willingness knowing that the council would safely refuse permission. Thus, Isabella appeared as a dutiful, conventional woman and wife, prepared to return to her husband, without actually having to face him again. On the other hand, this evidence does suggest the situation and Isabella's feelings towards Edward were more complex than traditionally assumed.

A particularly serious factor in Isabella's willingness to return to Edward was the fear of being met with violence. As I mentioned above, the 1330 parliament alleged Isabella wanted to reconcile with Edward in mid-1326 but Mortimer told her that "he" (either himself or Edward) would kill her if he did. Around the same time, Adam Orleton, Bishop of Hereford and a close ally of Isabella's, was circulating a story that Edward carried a knife in his hose in order to hurt Isabella with and had claimed that even if he had no weapon, he would "crush her with his teeth". The same threat of violence served as justification for the council's refusal to allow Isabella to visit Edward in April 1327. According to the Brut, Edward was confronted with a similar story - that some suspected he wished to strangle Isabella and their eldest son, Edward III - and was upset by the allegation, first denying it and then saying he wished he was dead.

It is extremely difficult to assess how true the story is. Obviously, it can be easily argued that the story was expedient for Isabella and her allies. Her refusal to honour her wedding vows and return to Edward's side was laid her open to claims of subversive behaviour and of perjury. This story, then, gave her a very clear and understandable reason to refuse to return to his side. Orleton and Mortimer were her allies, not unbiased observers, and so it was in their interests to spread the story: it explained Isabella's behaviour and vilified Edward.

On the other hand, it is a story that raises the spectre of domestic violence and should be taken seriously. It isn't totally crazy, either, that Isabella and her allies genuinely feared what Edward to do her should they meet again. She had overseen the executions of the Despensers and played a vital role in his deposition and she had lived through his revenge for the execution of Piers Gaveston. It would be very reasonable if Isabella feared he would treat her as he had treated Thomas, Earl of Lancaster.

We know very, very little about Edward and Isabella's personal relationship, and we know even less about Isabella's state of mind during the years of 1325-1327. It does seem that the marriage was companionable up until the final years and what caused the decline of their relationship is ultimately unknown.

I think it might well have been natural for Isabella to hope for a reconcilement during early proceedings. She had been married to Edward for 17 years and had four children with him. She had been loyal to him. I think that any decision she made would not have been made lightly and it would be natural if she did have doubts about their plans. I think she was politically astute enough that she conducted herself in a way that was designed to depict her as conventionally as possible to disguise her transgressive behaviour. I think, she was intelligent enough to realise that there was a point of no return - that the moment she launched her invasion force, there was no going back. I think - and this is going into highly speculative territory - if she wanted Edward back, it was probably in the sense of wanting things to go back to the way they were before their marriage had started to fracture. I think she may have found the freedom and power she had apart from Edward intoxicating and not wanted to go back. But that's just what I think - I don't make any claims that this definitely happened and I have evidence or Occam's Razor to back me up. This is probably how I would approach it if I ever wrote fiction about Isabella and Edward, but I most likely won't.

#i'm sick at looking at this ask so have at it#and apologies for the typos/mistakes/lack of reference list#isabella of france#edward ii#asks#anon#text posts#going to go for a walk and maybe take a break from answering asks for a bit to do some writing

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

John Lynch as Hugh Despenser the Younger in Edward II (1991).

27 notes

·

View notes

Note

I saw a saying that Isabella from France may not have cheated on her?

Hi, yes! The idea that Isabella had an adulterous relationship with Roger Mortimer has been widely accepted by historians, novelists and commentators for some time but contemporary and near-contemporary records do not unambiguously support it. In recent years some historians, such as Seymour Phillips, Michael Evans and Kathryn Warner, have been more cautious about the idea that Isabella and Mortimer did have an affair.

In some contemporary records, we have the report of rumour - The Chronicle of Lanercost claims "there was a liaison suspected between him and the lady queen-mother, as according to public report" while the unreliable Geoffrey le Baker claimed that Isabella was "in the illicit embraces" of Mortimer. Some sources seemed to describe their relationship in the discourse of royal favouritism (similar language is used to describe the relationship between Edward II and Piers Gaveston and Richard II and Robert de Vere). Adam Murimuth claimed Isabella and Mortimer had an "excessive familiarity (nimiam familiaritatem)" and another chronicler described Mortimer as her "amasius" (or lover), which is a term used also to describe Gaveston in relation to Edward. Jean Froissart, writing long after the event, even claimed Isabella fell pregnant with Mortimer's child but there is no other evidence for this claim and it's difficult to see how it could have been kept secret.

There is little support in other contemporary chronicles, which often only mention Mortimer in his less scandalous role of councillor of the queen and as a participant in the rebellion. In some cases, euphemistic language might be employed (the Brut describes Mortimer making himself "wonder priuee" with Isabella and Edward II himself wrote Isabella kept Mortimer's "company within and without house" while the report of a story Edward told of an unnamed queen who was disobedient to her husband and deposed, very likely alluding to Isabella, may also be a veiled reference to Isabella's adultery) but we don't know whether a euphemism was intended and we undoubtedly read it in the context where the idea of an affair has not only been raised but has been so widely accepted.

Basically, the evidence does not universally support the idea that they definitely had an affair, much less that they were brazen about it. It does seem like there were rumours about it and that chroniclers perhaps explained Mortimer's rise to power in the same way they explained Gaveston and the Despensers' rise (on that note: we don't know whether Gaveston and Hugh Despenser the Younger were Edward's lovers - it's certainly possible, perhaps even likely, but there's no way to know).

Warner has also argued that Isabella had too much sense of royal dignity to have an affair with a man of Mortimer's rank and that she was too pious to lie to the Archbishop of Canterbury about her desire to return to Edward - but I don't find these arguments particularly convincing. They're too subjective and are reliant on Warner's idea of what Isabella was "really like" while I believe that we don't and can't know what Isabella was really like to make these type of arguments.

Did Isabella have an affair with Mortimer? We don't know. It's possible she did - there is some supporting evidence for it. But the evidence may only be recording of rumours or slander. Where each person feels about the question probably relies on what they think of the narratives about Isabella's affair with Mortimer and what they think Isabella was "really like".

I don't have a strong opinion either way. I can see the argument for and I can see the argument against, and I think we should be cautious about taking the position that one is absolutely more likely to be true than the other. At a distance of 700 years, we have no way to know who Isabella really was and no way to prove or disprove whether she had sex with Mortimer or not.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Day 29: Isabella of France. Isabella married Edward II of England when she was only 12, but was quick to establish herself and her French connections as one of Edward’s key allies. When her husband’s lover Hugh Despenser threatened her position of influence and the stability of the kingdom, she invaded England with a mercenary army, forced her husband to abdicate, and then ruled as regent for her son Edward III. As regent, she settled conflicts with Scotland and France, and though she was later overthrown by her son, she continued to live comfortably and remained close to her family and the court.

#grayjoytober2024#isabella of france#history art#traditional art#historical women#capetians#plantagenet#medieval france#medieval england#14th century#france tag#english tag#inktober#inktober 2024#drawtober#drawtober 2024

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Watching a documentary on Edward II while I work and in this doc:

1. They repeatedly call Piers Gaveston Edward's "best mate" and "close friend", then have one seven-second acknowledgement that they were probably lovers before immediately returning to calling them pals, buds, just mates being dudes, my guys, just bros like bros will be, totally normal friendship here

2. Piers is not depicted as half so pretty as he likely was. He is handsome, yes, but very... dirty compared to everyone else? And also, dude, brush your hair. Come on. Piers Gaveston was famously not only arrogant but vain!

3. The actor playing Edward is playing this documentary dramatization like he is going for the motherfucking Oscar, he is amazing. I love him, my God someone give this man jobs and money!

4. They speak French! Just like everyone actually did!

5. Hugh Despenser has perfect hair, which seems in character

6. The documentary definitely doesn't admit the simple truth that Hugh Despenser the Younger was almost certainly Pretty Man Bait to get Edward II to give the Despensers power.

7. The doc DOES do a great job of showing what an absolute disaster Edward II was at basically everything forever

8. It does contain the most excellent line, "To the people of the time, Edward could have been bedding his priest, his page boy, and his horse, so long as he was governing the kingdom properly."

9. Isabella's actress is also incredible. That woman does some impeccable face-acting.

10. Man. The moral of this documentary - and of his life - should be "This man did not deserve the wild glory inherent in his amazing wife."

11. Now Hugh Despenser needs to brush his hair! Maybe Edward just likes 'em grungy.

12. Edward is the epitome of being shown exactly what he needs to do and then doing the opposite.

13. I am genuinely impressed at how carefully they dance around admitting that Edward was definitely up in Hugh Despenser's business, too. His manly business.

14. Wait, I take it back. The real moral of this story is "take a woman's children from her arms and she will burn you to the ground and spit on your ashes."

15. Honestly, I don't blame her.

16. THEY CALLED HER THE SHE-WOLF FOR A REASON, MOTHERFUCKERS.

17. Also, hell yeah for Isabella's brother the King of France working with her on this. He absolutely knew Isabella was being underestimated and he made sure he never did.

18. Oh, so we can admit Isabella and Roger Mortimer were sleeping together, huh? We can admit that? I mean as long as it's decently hetero, sure, let's have a whole sex scene. But God forbid we admit Edward and Piers might have held hands under a tree even once.

19. THEY PUT A SEX NOISE IN EVEN

20. Honestly now I'm mad.

21. "She has a number of men closer to a moderate house party than an invading force." Okay, that line redeems you somewhat.

22. Awwwww puppies hunting the disgraced king, sweet. I love when dogs are clearly checking for cues from their trainers just off screen.

23. A FIFTY FOOT GALLOWS SEEMS EXCESSIVE. Oh holy shit they hung him without quite killing him, then de-genitaled and- god damn, Isabella. This seems like a bit much.

24. SHE MADE A POINT OF EATING WHEN THEY CUT HIS DICK OFF.

25. Isabella is terrifying. I am in wild irrational love.

26. I'm sorry they put WHAT up Edward's ass. A red hot WHAT

27. I feel like that probably didn't actually happen but honestly, I don't doubt Isabella is capable of it. And also, um, these deaths seem... To send a message.

28. "Edward's wife and her lover-" oh, are you sure they're not just best mates? Buddies? Pals? Like Edward and Gaveston?

29. Oh he probably just like... was smothered. That makes way more sense. He could be "found dead" then and it could be claimed to be natural causes.

30. Underestimate pissed off French women at your peril, English kings.

#edward ii#ash rambles#history#english history#piers gaveston#king edward II#this shit is WILD#royal history#gay history#JUST BROS BEING PALS#isabella of France#the motherfucking she wolf#documentaries

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

ISABELLA OF FRANCE

ISABELLA OF FRANCE ‘SHE-WOLF’

1295 – 22 August 1358

Princess Isabella of France was 14 when she married King Edward II of England in 1308 who was aged in his 20s. Edward had no interest in women and preferred to spend all his time with his male favourites. His first favourite was Piers Gaveston who mocked and teased Isabella and gained much favor with the king. The king gave Isabella’s jewellery to Gaveston as a gift and many disliked Gaveston for gaining so many privileges. Piers was kidnapped and killed by those high in power. The king was upset for a while, but his relationship with Isabella improved and the couple had four children, including a heir, Prince Edward.

Edward found another male favourite, Hugh Despenser the Younger who Isabella thought was worse than Gaveston. Gaveston ruffled feathers gaining privileges from the king, and he too mocked Isabella. He demanded that the king should choose between him or his wife. Isabella was discarded, her lands and everything else was stripped away from her and the king even gave her children to Despenser’s family.

Isabella visited her brother, the King of France and took Prince Edward, 13, with her to pay homage. She didn’t want to return to England and refused to return their son, she was worried that Gaveston would have her killed.

In France, Isabella met a handsome young man Roger Mortimer who had fled England after escaping from the Tower of London. Isabella and Roger fell in love and became a power force. England at this time hated Despenser and Henry II was out of favour with the people, due to his poor rule.

Isabella returned to England with Roger as well as with an army. The English embraced her, she had her husbands rule overthrown and her son, who was still a minor, was given the crown. Despenser was hanged, drawn and quartered and Henry II was imprisoned and was later murdered by a hot poker up his ass. Isabella and Roger was to rule until her son turned 18.

When Edward III got older, he was upset with how greedy his mother and Roger became. Roger was hanged and his mother was sent away and spent the rest of her life living in luxury. Edward III (being French royalty through his mother) attempted to gain the French throne, which started the Hundred Years' War. Isabella lived to old age and died most likely from an illness. She was buried and given a nice effigy, but Henry VIII had destroyed the church, and it was later destroyed by a fire. Where she is buried now is a mystery.

#isabellaoffrance

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Edward Despenser was fortunate in making a prosperous marriage to a tenacious businesswoman. Elizabeth (de Burghersh) was skilled at upholding her rights on the estates and worked hard to protect the lands of her two-year old son after Edward's premature death in 1375. There is abundant evidence of her willingness to maintain, even augment, the enormous Despenser inheritance and she combined shrewd business acumen with a clear awareness of the problems that a long minority could bring. This was a time when widows, as well as wives left at home during military campaigns, needed to be able to manage property. The French noblewoman Christine de PiZan wrote in The Treasure of the City of Ladies of the need for preparation for this task- 'they should have the responsibility of the administration and know how to make use of their revenues and possessions ... [and] they will be good managers of their estates'. It was a call for female entrepreneurs, and Elizabeth Despenser was a woman after Christine de Pizan's heart. The trust that her husband placed in her is made apparent by his choice to remain in Italy when Bartholomew Burghersh died, trusting his wife to look after the enlarged patrimony. Ten Suffolk manors fell to the Despensers - Carlton, Middleton, Clopton, Little WeInetham, Blaxhall, Swilland, Witnesham, Cock-field, FenhaH and Chesilford - together with Ewyas (Heref.) and Bosworth (Leics. ), and the patrimony was greater than it had ever been.

After Edward's death Elizabeth vigorously pursued lands farmed out by the crown and within five years recovered control of Shipton, Burford, Sherston, Kimberworth, Caversham and Great Marlow, collectively worth over £100 per year. She also obtained seisin of lands of her Despenser relatives, Gilbert (d. 1382), and Thomas, her brother-in-law (d. 1381). From Gilbert came the keeping of Broadtown (Wilts.); from Thomas various Lincolnshire lands and two-thirds of the manor of Mapledurwell (Hants.), which she later demised to her esquire Henry Yakesley. Via her daughter Anne, married to Hugh Hastings, came the Norfolk manors of Gressenhall and East Lexham. In 1392 Elizabeth obtained the wardship of Peter Veel after the death of his mother Eleanor, a tenant of the Despensers in Glamorgan. She held onto this as long as she was able, and it was fully ten years later when Henry IV ordered her to release the lands to the heir. In the meantime, Elizabeth had convinced Richard II to re-grant the Irish manor of Killoran, county Waterford, that had originally been held by her husband. At the same time, she had to contend with paying out two major annual sums. The first came in 1378 when £200 from the farm of Glamorgan was ordered to be paid to Sir Degary Says. Says had sustained losses in Aquitaine and also made forced loans of gold to the crown for the upkeep of the English armies, and King Richard's regency council decided that recompense should be made from the Despenser estates. The second came two years later, when Edmund earl of Cambridge, son of King Edward III, was awarded Thomas Despenser's wardship and 500 marks per annum. from Elizabeth's dower lands. Shortly before his death Edward Despenser spent his final military campaign in Brittany with the earl and it is possible that an arrangement was made at this time about Thomas's guardian. In 1384 Richard II gave permission for Thomas and the earl's daughter Constance to be married, and Elizabeth was then required to pay for her daughter-in-law's upkeep. Some idea of the considerable annual turnover of the Despenser estates may be found from documents dated between April and October 1391, where expenditure on annuities alone totalled 1016 marks (£677 6s 8d).

Elizabeth was vital to the continuing presence of the family in the last quarter of the century. Had she remarried after 1375, her dower lands would have been demised to her new husband and the Despenser inheritance impoverished. As it turned out, the ease with which Thomas took over the estates owed everything to her tireless efforts. She continued to pay annuities owed to members of Edward Despenser's retinue, and the fact that a number of these men served the family throughout this period tells us much about the advantages of continuity in estate management. We know that she held court in Glamorgan in 1393, and doubtless did so on other occasions. Her name also appears on two charters of 1397 confirming the privileges of the burgesses of Cardiff and Neath. However, Elizabeth's longevity was eventually to cause problems for Thomas who never enjoyed full possession of his inheritance. When he died at Bristol in 1400 she was still in possession of her dower as well as her own Burghersh inheritance. Other properties, such as Mapledurwell, had been safeguarded through grants to retainers or were held by cadet branches of the family. Only after Richard Despenser's early death in 1414 was the entire inheritance reunited under his sister Isabel and her first husband Richard earl of Worcester. The survival of the patrimony was due in no small part to Elizabeth Despenser, whose efforts, in the context of incessant Marcher power struggles and the Glyn Dwr revolt of 1400-8, should not be underestimated. It is a testament to her ability in the eyes of successive kings that in 1375 and 1400, unlike in 1349, no royal justices were appointed in Glamorgan to hear pleas of the crown. Everything was left to the Despenser women. Like her earlier kinswoman Elizabeth de Burgh, Elizabeth Despenser proved the value of a dowager administrator.

- Martyn John Lawrence, “Power, Ambition and Political Rehabilitation - the Despensers”

#historicwomendaily#history#despensers#elizabeth le despenser#Elizabeth de Burghersh#edward le despenser#english history#queue

20 notes

·

View notes

Note

your posts have officially made me fall into the Despenser Den, thanks for that <3

Oh my god, this message made me so happy :D In honor of it, here's a very long text about some interesting facts about the Despenser family, mostly about their relationship with Edward II. I already mentionned many of them throught the years but eh, now there all gonna be in one space..

Edward II's had a close bond with the Despenser family long before he started his relationship with Hugh the younger. Hugh's father (also called Hugh like pretty much every single first born males in their family) had been a good friend to Edward I and his wife Eleanor of Castile (who was fairly unpopular at court so that's interesting to me). He had therefore known Edward II since childhood and seems to have been something of a father figure to him. Not only was he present for Edward II's wedding to Isabella of France in Dover but he was also invited to share the king's personal barge when they came back to England. He was one of the only noble who supported Piers Gaveston, for which I think Edward was deeply grateful. A few years later, he was chosen to be one of baby Edward III's godfather, another sign of how close he was to the king.

Hugh the elder's wife Isabel Beauchamp appeared to have been quite a colorful caracter and a bit of a wild girl. Hugh was her second husband and she married him without the king's permission (which I always found quite baffling as there's no evidence that he would have refused for them to get married) and they were fined greatly for it. They only paid about half of this fine before being officially forgiven. Isbael ended up dying a little over twenty years before her husband and he never remaried. A certain William de Odyham also accused her of having poached bucks at Odiham park. Hugh the younger didn't appreciated de Odyham talking shit against his mother and had him removed from his position as the park keeper.

Edward II's also has a personal friendship with Hugh the elder's daughter Isabel that started long before his relationship with her brother. She married Edward's childhood friend Gilbert de Clare which appears to have helped her forge a friendship with her king. While Gilbert unfortunatly died about two years into their marriage, Isabel et Edward remained friends until his death. She was even in charge of his two young daughters household from 1324 to 1326. Interestingly enough, despite Isabella of France very clear hatred for the Despensers family in general, she didn't seems to have had any type of dislike or resentment for Isabel and she survived her family's downfall unscathed (but probably not untraumatized).

Hugh the younger's eldest son Huchon (also sometimes refered to as Hughelyn which I personally find adorable) was also the son of Eleanor de Clare, Edward II's eldest and favorite niece. They were close in age and probably had a relationship that was closer to cousins than a regular uncle and niece one. Huchon appears to have been Edward's favorite nephew. He gifted him various fancy gifts all throught his life, including lands from the age of about 9 or 10. He also started sending him on various missions when he reached teenagehood. Huchon was about 10 years old when his father started his affair with his uncle and I truly wish we knew how he felt about that because just imagine lmao.

Huchon had an extremely priviledge childhood and youth until his family eventual downfall when he was about 17 or 18 years old. He then fought on Edward II's side and held Caerphilly Castle for a while. Isabella of France, who apparently planned to have him executed (not her fairest or kindest move) tried to end the siege by offering Huchon's men pardon if they surrender on multiple occasions but they refused until they were assured that Huchon himself would not be harmed, which seems to indicate that he was more popular and probably more personable than his dad. After the brutal executions of his father and granfather and his own imprisonment, Huchon seems to have cling to the hope that Edward II might have still been alive as late 1330, which is kinda heart breaking to me.

Luckily for him, the wheel of fortune turned over again after Isabella of France lost power to her son. Edward III seems to also have been quite fond of Huchon: not only he had him freed and officially forgave him for his participation in the siege of Caerphilly Castle, he also frequently received gifts from him, was invited to most of the jousts Edward III organized and often fought at his side during the hundred years war. Edward III's relationship with the Despenser's family is quite interesting in its own right imo and I might write another post about it at some point if anyone care to read about it.

In conclusion, I warmly welcome you in the Despenser Den! We're a teeny tiny club but we have a lot of more or less ridiculous anecdotes and a lot of fun :D

#honestly i would have a lot of other things to say but i think it's long enough for now lmao#wishesofeternity#edward ii#hugh le despenser#isabella of france#isabel hastings#isabel de beauchamp#i appreciate all the isabels having slightly different names unless all the hughs who were just like the elder the younger the even younger#and the others#also most of those tags had been dried af in the past months so thank you for giving me a chance to write something about them

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

So here's an alternate history thought...

I'm not sure I've ever come across this one before (and to be fair I don't know all the alternate history that's out there But).

This is about Edward II of England.

For those of you who don't know, he was some flavor of queer/MLM ((generally considered to be gay; I'm wary of putting specific labels on historical figures for a number of reasons, but that is I believe the general consensus as to his sexuality.))

He also had pretty awful taste in men.

Like, there were revolts against him over his favorites/boyfriends--not actually so much because they were dudes, but because he kept giving them properties and offices and so on. Also the Despensers in particular (probably only Hugh the Younger was his lover; but Hugh the Elder (his father) also got a lot of stuff) were just. Unpleasant Grasping Assholes.

Edward himself was also kind of an asshole.

Anyway, his first favorite was a man named Piers Gaveston. What records we have do seem to indicate that there was Genuine Affection between the two of them. But...well, the above problems applied; one of the most egregious examples was when Edward II married Isabella of France, it...like Gaveston's arms were everywhere; it basically read, according to contemporary accounts, more like a wedding feast for Edward and Piers than Edward and Isabella. Which, in addition to being a Bad Idea politically when celebrating a Political Treaty Marriage, is also just. Rude????

There's more, but that's the Relevant Background to this. Thing. that came into my brain.

And that is this:

What if Edward II did the Edward VIII thing--i.e., abdicated to be with Piers in a way he Could Not as king?

Edward had two half-brothers; the older was Thomas of Brotherton. What kind of king would Thomas I have been? What would all of this mean for the next two centuries of English (and French) history?

Does this alternate history novel already exist???

#history#history side of tumblr#alternate history#alternate history side of tumblr#edward ii#yes i'm aware i could write it myself#but i have other projects#including a different alternate history#where henry viii dies in that one jousting accident#(which is mostly focused on mary and elizabeth's relationship as elizabeth grows up after mary deposes her)#(vague plan to have it in an epistolary format starting form elizabeth's marriage)#(though also mary returning england to the catholic church is much more feasible at that point)#ANYWAY so yeah i'm curious if this already exists#or if anyone else wants to run with it who's done a little more in-depth reading on the period#(most of my plantagenet knowledge is henry ii and the soap opera of his immediate family)#and okay to be fair thomas's age at the time of their father's death makes this Unlikely#but Still

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

“…When writing to Charles to ask for his assistance in the swift return of the queen [Isabella of France] and her son to England, Edward II asked that his brother-in-law proceed ‘according to reason, good faith and fraternal affection, without having regard to the wilful pleasure of woman’. None of this, however, reckoned with the forcefulness and resourcefulness of Isabella, who now sought publicly to justify her actions on two counts: that she could not be expected to return to her husband's side because of the threat of physical violence; and that her marriage had collapsed not because of Mortimer but because of Hugh Despenser. The sexual insinuation was unmistakable. Edward II's attempt to assert his husbandly authority had simply served to expose the blatant hypocrisy of his own case.

Faced with the public refusal of Isabella to accept her wifely and political responsibilities, the king now tried to appeal directly to their son. It is not known what attitude Edward of Windsor took to the breakdown of his parents’ marriage. It is reasonable to suppose that he sympathized with his mother's plight, though it is also true that he later showed neither affection nor mercy to Mortimer, whom he emphatically represented as the true cause of the enmity between Edward II and Isabella. Once Mortimer had ingratiated himself into the queen's company and her bed, then, it may be that the prince became a good deal less than enthusiastic about his enforced exile. On 2 December 1325 the king opened direct correspondence with his son, appealing to the prince's loyalty and begging him to return home with or without Isabella. Any hope of a reunion between father and son was rapidly eroded, however, by Edward II's increasingly threatening behaviour. In January 1326 the prince's English estates were put under royal administration, though their revenues were still made available for the young Edward's needs. More startlingly, in February the sheriffs were instructed that the queen and her son were to be arrested if and when they arrived in England, and that their foreign supporters were to be treated as the king's enemies. In March Edward II assumed the role of ‘governor and administrator’ of Aquitaine and Ponthieu in an attempt to deprive Prince Edward of an authority that might otherwise be used against the English crown. Ironically, the only effect was to drive Charles IV to reoccupy the parts of greater Aquitaine from which his forces had only recently begun to withdraw.

Edward II's last-ditch efforts to appeal to filial loyalty, in March and June 1326, were entirely lacking in a sense of fatherly affection. Indeed, they were ominously threatening: the king warned that ‘he will ordain in such wise that Edward shall feel [his wrath] all the days of his life, and that all other sons shall take example thereby of disobeying their lords and fathers’. The impact of this correspondence on an impressionable young teenager can only be guessed. However, the self-conscious displays of loyalty that Edward III showed to his father's name after the latter's deposition and death almost certainly represented a necessary public act of atonement for the blatant act of defiance in which he had been implicated, either willingly or unwillingly, in 1325–6.”

-W Mark Ormrod, Edward III (The English Monarchs Series)

#gotta love edward ii consistently making the worst decisions possible#imagine telling the sheriffs to ARREST Isabella and his own son????#i'm genuinely not sure what he expected would happen 💀#isabella of france#edward ii#edward iii#14th century#my post

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rous Roll 15th century depicting the beheaded body of Piers Gaveston earl of Cornwall and the great love of Edward II underfoot of Guy de Beauchamp earl of Warwick. (There are no contemporary portraits of Gaveston and this is the earliest visual depiction I know of).

Piers Gaveston is probably the most notorious English royal favourite in history, arguably more so than George himself. Due to the nature of medieval source material, the man has been largely lost to us and instead to quote one historian we have been left with a caricature of “a sycophantic homosexual with a marked tendency towards avarice, nepotism, and especially overweening pride.” A handsome and charismatic man and a talented knight who was in fact a skilled administrator acc to current historiography, Gaveston was nonetheless despised in his lifetime as a greedy, sexually manipulative upstart who took advantage of the weak and lazy Edward II to enrich himself to the detriment of the great lords of the day.

Sound familiar?

George Villiers would probably known about Piers - he was often compared to him (along with a number of other notorious favourites such as Sejanus, Hugh Despenser, and Henri III’s Minions) in his own lifetime and Christopher Marlowe’s play Edward II was still popular, along with a number of printed chronicle histories. Indeed, the comparison was so strong, Elizabeth Cary Viscountess Falkland, one of the few female scholars of the day and supporter of Henrietta Maria in the 1620s, in fact wrote a Roman a clef about the George-Charles-Henrietta triangle using Edward I, queen Isabella (also french), and Gaveston as stand ins for their 17th C counterparts.

This book, which was a contemporary political tract and not a proper history per se, albeit unpublished in the authors lifetime (it was published in the 1670s during the exclusion crisis) has often been cited wrongly by some as a legit medieval history and is responsible for some of the myths around Gaveston, such as his mother Claramonde de Marsan being a witch (this was a swipe against Mary Beaumont and the claims she helped poison King James), or that he was needlessly hostile and disrespectful against Queen Isabella (reliable contemporary sources don’t say anything about Isabella and Piers’s feelings about one another - this was clearly about George and Henrietta).

As you may have guessed from the above both George and Piers met violent ends. Piers was kidnapped and illegally executed while under the protection of the earl of Pembroke on the orders of the earl of Warwick (the other bloke above) on 19 June 1312. George was murdered by a certain John Felton in Portsmouth 23 August 1628 following a barrage of black propaganda and character assassination launched by his enemies at court and in parliament.

Favouritism - high reward, high risk.

There haven’t been any bios of Piers for the popular market and the last academic study was in 1994 - I strongly recommend Kathryn Warner’s blog for more info on this period.

#george villiers#duke of buckingham#charles i#james i#piers Gaveston#Edward ii#why whenever there is opposition to the crown the earls of Warwick ae somehow involved?#George can’t say there wasn’t precedent for what happened to him

2 notes

·

View notes