#Hessian state archives

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Extremely rare photo of Grand Duchess Olga Nikolaevna (sitting on the balcony), Grand Duchess Anastasia Nikolaevna (making a funny face), and Grand Duchess Maria Nikolaevna (crouching), 1912

Source: Hessian State Archives

#Nastya 😂#otma#romanov#romanovs#olga nikolaevna#maria nikolaevna#anastasia nikolaevna#Romanovs being funny#Shvybzik#1912#otmaa#naotmaa#russian imperial family#russian history#Russia#grand duchess anastasia nikolaevna of russia#grand duchess Olga nikolaevna of Russia#grand duchess Maria nikolaevna of Russia#Romanov family#hessian state archives#1900s

124 notes

·

View notes

Text

Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna the Younger (source).

88 notes

·

View notes

Text

EXTREMELY RARE photo of Princesses Victoria, Elisabeth, and Irene of Hesse and By Rhine, 1868-69 🤍✨⭐️

Source: my lucky day at the Hessian State Archives

#🥹🥹🥹#Irene is so cute 😖#princess victoria of hesse#princess elisabeth of hesse#princess Irene of hesse#Victoria of hesse#marchioness of Milford haven#elisabeth of hesse#elisabeth feodorovna#Elizabeth feodorovna#Irene of hesse#princess Irene of Prussia#hessian royal family#hesse#1869#1868#Hessian state archives#rare#favs

61 notes

·

View notes

Text

1896

THE GENTLEWOMAN. October 3 & 17

Darmstadt, October 3

The Grand Duke and Duchess of Hesse intend to move with their Court from the Jagdschloss Wolfsgarten to the New Palace at Darmstadt, on Tuesday, the 6th int., in order to be there at the arrival of the Tsar and Tsaretsa.

The Grand Duke and Duchess Serge of Russia arrived at Darmstadt from Venice last Wednesday, and went immediately to Wolfsgarten.

The Princess Louis of Battenberg is now at Heiligenberg with their children, and pays frequent visits to the Grand Duke and Duchess.

Little Princess Elizabeth is already talking about her cousin, Grand Duchess Olga, and is delighted that she is soon to have a little companion to play with. Her Grand Ducal Highness is a very pretty, clever child, and remarkably lively.

Darmstadt, October 17

The little Princess Elizabeth of Hesse is delighted with her still smaller cousin, Grand Duchess Olga, and to see the babies playing together is an unfailing source of delight to the two young mothers. Both are very pretty children, and are extremely forward for their age.

(...)

On Tuesday last the Grand Duke and Duchess drove with their Imperial guests to Heiligenberg, where they had tea with the Princess Louis of Battenberg; and the next afternoon was spent at Jagdschloss Wolfsgarten, where they also had tea, and returned in the evening to Darmstadt.

source: the British Newspaper Archive

image: Hessian State Archives, Elisabeth and Olga sit on their mothers' laps and pose in a group picture taken in June 1896.

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

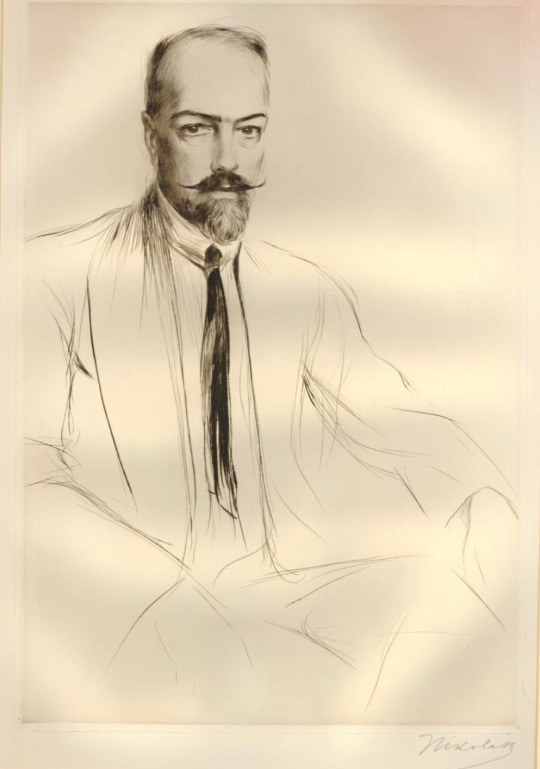

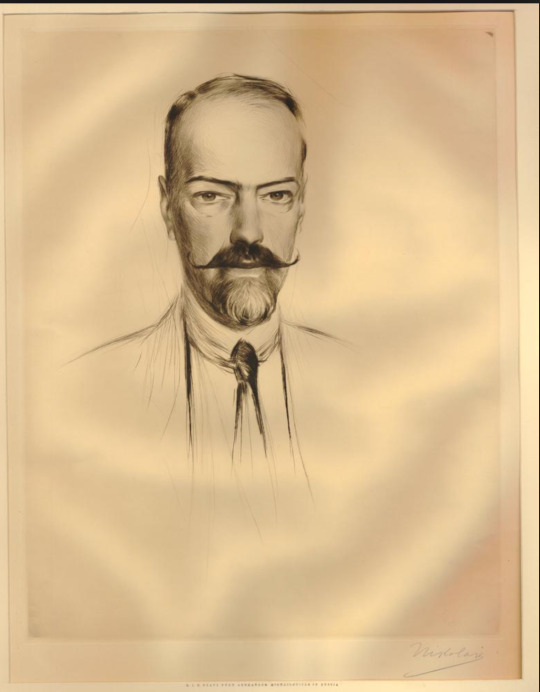

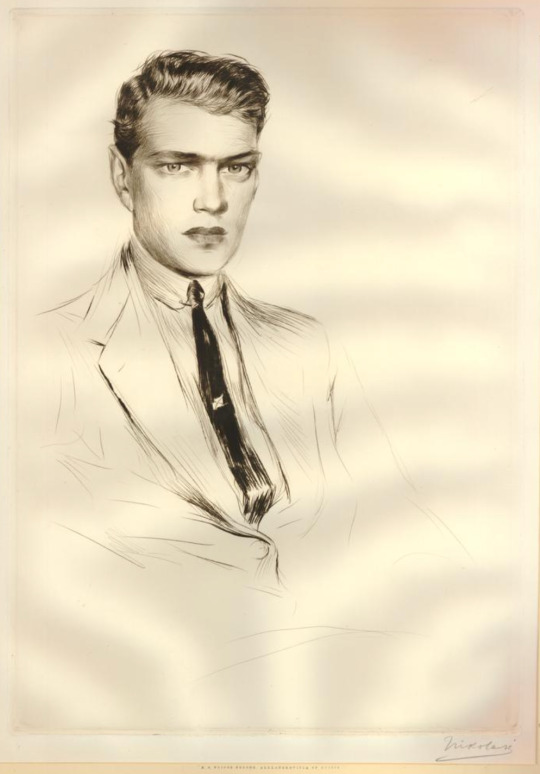

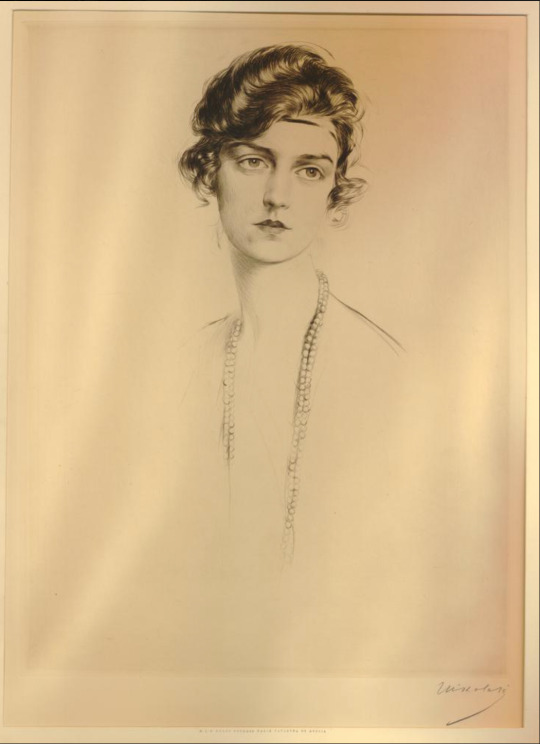

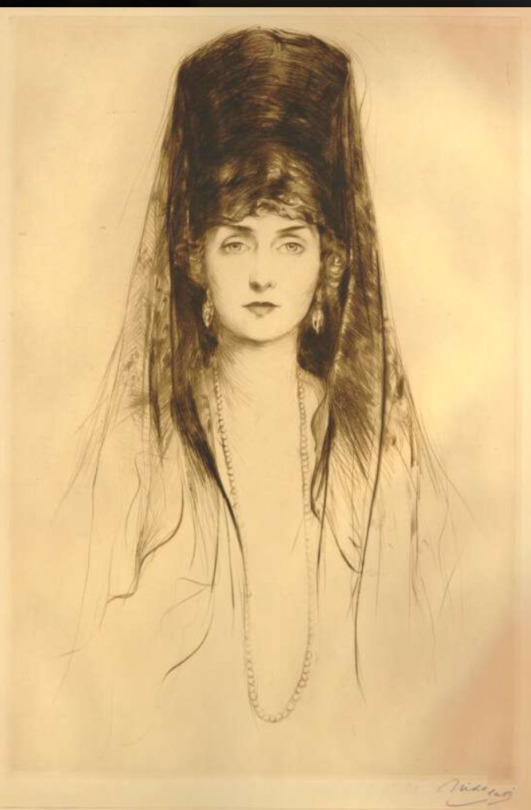

Portraits of Romanovs (and Relations) by Nicholas Panagiotti Zarokilli

Nicholas Pannagiottis Zarokilli was born in Turkey in 1879. He was a painter particularly fond of creating pictures of beautiful women. From 1912 to 1920, Zarokilli produced paintings for publications like MoToR, Modern Priscilla, Women’s Home Companion, The Green Book, McCall’s, and The Saturday Evening Post.

He also designed World War I posters. The United States needed money for the war, so the artist created posters to try and encourage people to give for the cause.

Zarokilli was known well for his dry-point paintings. Drypoint is a printmaking technique of the intaglio family, in which an image is incised into a plate or "matrix" with a hard-pointed "needle" of sharp metal or diamond point. In principle, the method is practically identical to engraving.

He painted portraits for people such as the Queen of Spain, the Archbishop of Canterbury, Grand Duchess Anastasia, the King of Portugal, and Mr. and Mrs. Solomon Guggenheim. Landscapes were also his love, painting the cities of Venice, Madrid, and Seville.

The following is his rendering of several members of the Romanov family (and other relations.) I have seen some of these here and there before (several of you have them in your Tumblrs and always admired them; I think he captures the likenesses admirably. I found the ones here together and identified on the British Museum website (they were done between 1920 and 1922.)

These are the names of the easily recognizable "personages" in the paintings in the order they appear below:

Prince Felix Yusupof (wearing a suit)

Prince Felix Yusupof (head)

Princess Irina Alexandrovna

Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich (sitting)

Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich (bust)

Prince Andrei Alexandrovich

Prince Feodor Alexandrovich

Grand Duchess Anastasia Mikhailovna

Grand Duke Kyril Vladimirovich

Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna the Younger

Queen Marie of Romania (born Princess Marie Alexandra Victoria of Edinburgh) - Granddaughter of Queen Victoria

Queen Victoria Eugenie of Spain (born Princess Victoria Eugenie Julia Ena of Battenberg (youngest granddaughter of Queen Victoria, Hessian Princess through the morganatic Battenberg line)

References

N.P. Zarokilli Archives | The Saturday Evening Post

Nicholas Panagiotti Zarokilli | British Museum

#Nicholas Panagiotti Zarokilli#Prince Felix Yusupov#Princess Irina Yusupov#Grand Duke Alexander Mikhailovich#Grand Duchess Anastasia Mikhailovna#Prince Andrei Alexandrovich#Prince Feodor Alexandrovich#Grand Duke Kyril Vladimirovich#Grand Duchess Maria Pavlovna the Younger#Queen Marie of Romania#Queen Victoria Eugenia of Spain#Romanov dynasty

40 notes

·

View notes

Text

This also could be his sons Georg Donatus or Ludwig, I think I recognize the photo from looking at the hessian state archives and the date was either from 1908-1911 and also Ernie looks older than when Ella was a baby. I will double check the archives though.

Grand Duke Ernest of Hesse with a baby; I believe it's his daughter, Princess Elisabeth.

#there is still a chance it could be Ella#hessian Royal family#grand Duke Ernst Louis of Hesse and by Rhine

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The misfortune which ensued": The defeat at Germantown [Part 2]

Continued from Part 1

This was originally written in October 2016 when I was a research fellow at the Maryland State Archives. It has been reprinted from Academia.edu and my History Hermann WordPress blog.

Illustration of the battle at the Chew House by American artist Christian Schussele

Regardless of who is blamed, the heavy fighting undoubtedly resulted in the death and wounding of many soldiers, leading to a withdrawal. [15] Soldiers were disoriented and confused by heavy morning radiation fog, caused by a 34 degree temperature and humidity, along with the thick black powder smoke from cannons and muskets. This annulled any chance for victory, even though some claimed that they were near to “gaining a compleat Victory.” [16] Washington said that his army would have gained victory if “the fogginess of the Morning” hadn’t prevented the Continental Army “from seeing the advantage we had gained.” [17] In later letters he told General William Heath, his brother John Augustine Washington, and Virginia politician John Page a similar story. He wrote that the hazy day was “overcast by dark & heavy fog,” was “extremely foggy,” and “a thick Fog rendered so infinitely dark at times.” [18] From his viewpoint, this prevented the enemy from sustaining “total defeat” with complications including the Continental Army’s right wing lacking ammunition as the battle dragged on.

After the battle, the Continental Army moved twenty miles way to collect their forces and care for the wounded as the British still held on to Philadelphia. [19] While wounded Marylanders were sent to Reading, Pennsylvania, the Continental Army camped beside the Delaware River before returning to Perkeomen, where they had been stationed before the battle. [20]

George Washington, with the help of other officers and informers, repeatedly tried to assess their losses and that of the British. Washington claimed that the Continental Army suffered “no material loss of Men.” His estimates of those killed, wounded, and missing ranged from 300 to 1,000. [21] He also said that only one artillery piece was lost, along with some captured due to the foggy conditions. In his memoirs, in early nineteenth century, Connecticut Lieutenant James Morris wrote that “many fell in battle and about five hundred of our men were made prisoners of War, who surrendered at discretion.” [22] While the number of casualties from the battle is not known since the official return of Continental causalities from the battle has been lost, the Annual Register, a British parliamentary publication, may be the most reliable, as they reported that 200-300 Continentals were slain, 600 wounded and more than 400 were taken prisoner. [23]

The estimates of British casualties are also not clear. Through the month of October, informers, who were often deserters, told George Washington and other high-level generals that hundreds of wagons came into the city of Philadelphia with wounded soldiers. [24] Those that were wounded reportedly included British army general William Erskine and Hessian general William von Knyphausen, along with 300 to 2,500 British killed and wounded on the bloody day. [25] The Annual Register said that the British losses of wounded, killed, and captured numbered 535, but only 75 were killed and 54 officers taken prisoner. [26] Hence, the estimates by deserters that 2,500 British were casualties may have been exaggerated.

The Continental prisoners from the battle did not fair well. James Morris described how he was captured ten miles away from Germantown after being “continually harassed” by British light infantry and dragoons. [27] Morris, like many others, was taken prisoner, and held in Germantown from October 4 to 5th. He was moved to Philadelphia, where he was a prisoner in Walnut Street Jail. [28] He remained there along with 400 to 500 Continentals in squalid conditions until May 1778. The jail was cold, dark, and desolate, and many prisoners had no bedding, blankets, or general provisions, while others became sick or died. [29]

As the Continentals languished in Philadelphia, officers were accused of being responsible for the defeat and court-martialed as a result. While some believed that the battle reflected “honor upon the General and the Army” and that General Sullivan was a “brave Man,” not everyone agreed. [30] He was partly criticuzed for the friendly fire between Sullivan’s division and Nathaniel Greene‘s troops during the battle, due to the fog. [31] He was likely seen as part of the reason for the “real Injury to America” caused by the defeat: the continued British occupation of Philadelphia. Sullivan defended himself by writing to Washington that after the battle “the field remained his [Howe’s,] the victory was yours” and that Howe could only be defeated by “a Successful General Action.” [32] Others accused of improprieties during the battle included Pennsylvania militia general Thomas Conway, accused later of conspiring against Washington, Captain Abner Crump of Virginia, Nathaniel Greene, Captain Edward Vail of North Carolina, and Captain Adam Stephen of Connecticut. [33] Of these men, Vail, Crump, and Conway were court-martialed and removed from the Continental Army.

Despite the fact that the battle was a defeat for the Continental Army, it served a purpose for the revolutionary cause. John Adams wrote, in July 1778, that “General Washingtons attack upon the Enemy at Germantown” was considered by “the military Gentlemen in Europe” to be the “most decisive Proof that America would finally succeed.” [34]

In the following months, some Marylanders fought along the Delaware River in forts Red Bank and Mifflin. The British were trying to push the Continentals clear out the Delaware River in order to secure Philadelphia. [35] By the end of the campaign, however, their only victory was ensuring that the city was “a good lodging” for the British Army. The rest of Marylanders stayed in camp until they wintered in Wilmington, Delaware and the rest of the army wintered in Valley Forge. [36] In the following years, the First Maryland Regiment would fight in the northern colonies until they joined the Southern campaign in 1780 and 1781. [37]

© 2016-2023 Burkely Hermann. All rights reserved.

#chew house#military history#battle of germantown#revolutionary war#american revolution#british victory#us history#muskets

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Prince Francis Joseph and Princess Anna of Battenberg at Wolfsgarten, 1907.

Source: Hessian State Archive.

#prince francis joseph of battenberg#princess anna of battenberg#princess francis joseph of battenberg#battenberg#hesse#hesse-darmstadt#german royal#german royalty#1907#1900s

40 notes

·

View notes

Note

For scholarly research where do we find the originals for the referenced documents

This really depends on what documents you are after. Most of them will be in national archives of various states like GARF, The Royal Collection Trust or The Hessian State archives. But many will be in private collections as well.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Captured, Chained, and Purloined: An Irishman’s Adventures in the Revolutionary War

By: Lisa Timmerman, Executive Director

Listed as a Dumfries merchant in 1789, Bernard Gallagher was an unstoppable force in the town. He participated in Dettingen Parish’s Overseers of the Poor, was a member of the Quantico stock company hoping to “save” the silted creek and kept his business thriving (based on his inventory) while the Town struggled with their declining economic realities. While he presumably led a prosperous life before his death in 1821, he left quite the legend behind of his Revolutionary War service.

While family lore can be inaccurate (whether intentionally or unintentionally), it is always exciting to study the story and hunt for the facts. Supposedly, in 1781, Gallagher “…loaded a vessel at Alexandria with corn to provision Yorktown, dropped down the river and was chased by a British cruiser…”, which led to skirmishes and Gallagher’s failed escape attempt, “…was captured, and held in chains at Halifax two years in the prison ships, until the peace.” Researcher Judd Banks unearthed actual documents from Gallagher at the time of the event to determine the accuracy and while the tale did suffer from exaggerations, it was not far from the truth!

(Black and white reproduction of a water color portrait of Bernard Gallagher, 1803, original owned by family)

Banks discovered that Gallagher was on a British brig in 09/1774 when captured by Captain John Paul Jones. Gallagher then enrolled (a sound decision), and actively engaged in naval service. Unfortunately for Gallagher, “a series of misfortunes” disrupted his faithful patriotic service in 1776. This time, a British brig spotted the Americans and pursued them. Gallagher explained the circumstances to Jones on 11/03/1776, “We all being aboard, the privateer was obliged to run into St. Peter’s Bay, thinking to escape them there. However they pursued us through the woods, with all the exasperated inhabitants, and took thirty of us, out of fifty-five, prisoners, nine of them belonging to us, dividing us between both vessels. I being put on board Captain Dawson, where he paid me the compliment to put me in irons for fourteen days, being so much more the aggressor…” According to Gallagher, “…were oft obliged to live daily on two-thirds of a pound of bread and about two ounces of pork, one hundred of us being confined in a vessel’s hold, about one hundred tons burthen, with a guard of twelve soldiers to watch us. There we were obliged to stay for two weeks more, when we had the pleasure to be put aboard the cartel.”

The British did not initially consider captured patriots as prisoners of war treating them instead as rebels, meaning the British denied them the basic common rights and privileges they offered to countries they recognized. While this changed after Americans captured significant forces in the Battle of Saratoga in 1777, commanding officers still carried out any prisoner exchanges. Notably, prison ships were horrific and mortality rates of prisoners were high due to insufficient and dangerous conditions.

Gallagher’s woes did not end there. He contacted Jones again on 01/18/1777 regarding his stolen property. Naming the thieves, he requested, “…as they were guilty of so mean an action on board your ship without your knowledge, I hope in Case they do not Return the Articles they Embezeled and Carried away, you will stop their wages and prize Money to the Amount of the same as they left me destitute in Every Necessary of life…” His attached inventory included: “One Claret Coloured Suit of Cloaths”, “1 pair best black everlasting Breeches new”, “7 Ruffled Shirts and 1 plain Do (shirt) almost new Cloath at 2/7pr in Ireland”, “1 feather bed”, “1 barrel of Muscavado Sugar”, along with rum, various clothing articles and accessories.

Gallagher died in 1821 and was buried in Dumfries Cemetery. He left his Dumfries property to his wife Margaret, “…the house and lot whereon we now live (with the exception of the store and compting room & the small Granary) also the garden and stable on the old warehouse Lot, all at present in my occupancy…” While he divided the enslaved to his wife and children, he specified, “…& the negroes save those bequeathed to my wife hired out to the best advantage and the money arising from those sources applyed to the education of the younger children and the support of the family…” He bequeathed Lucy, Fanny, and Jim to his wife, “a negro girl called Harriet” to his daughter Eliza Peyton, Sarah to daughter Mary, “a negro girl called Jane” to daughter Ann, and Emily to daughter Margaret. Not mentioned in his will but in his inventory were Daniel Bull, John, George Chapman, Henry, Carpenter John and his Tools, and George Coote. Besides for his collection of furniture and other expensive material objects, he also owned a “likeness of Genl. Washington” and a piano forte. Thanks to court records and family research, it is possible to follow some of the enslaved and family descendants through history.

Special thanks to Jud Banks for sharing his research and donating an advanced copy of his 1990 book The Captain and His Kids: The Story of Bernard Gallagher, Irish Immigrant, and His Children, 1749-1893.

Note: Can’t get enough Revolutionary War history? Who can?! Join us at our free Members First virtual presentation featuring President of the Col. William Grayson Chapter of the Sons of the American Revolution Ross Schwalm as he discusses the Hessian Prisoners held here in Dumfries! Click here for more info and your free ticket. No commitment or pressure to join HDVI by registering & attending.

(Sources: Banks, Jud. The Captain and His Kids: The Story of Bernard Gallagher, Irish Immigrant, and His Children; Prince William County Will Book L Will, Pages 400-402, Inventory, Page 487; Force, Peter, and M. St. Clair Clarke. 1837. American archives: consisting of a collection of authentick records, state papers, debates, and letters and other notices of publick affairs, the whole forming a documentary history of the origin and progress of the North American colonies ; of the causes and accomplishment of the American Revolution ; and of the Constitution of government for the United States, to the final ratification thereof. Volume III, Page 507, https://archive.org/details/PeterForcesAmericanArchives-FifthSeriesVolume3vol.9Of9_110/page/n253/mode/2up?q=gallagher; Morgan, William James, Ed. Naval Documents of The American Revolution. Washington: Naval History Division, Volume 7, pages 991-993, https://www.history.navy.mil/research/publications/publications-by-subject/naval-documents-of-the-american-revolution.html; Compeau, Timothy. Prisoners of War. The Fred W. Smith National Library for the Study of George Washington at Mount Vernon: Digital Encyclopedia, https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/prisoners-of-war/#5)

#revolutionarywar#localhistory#destinationdumfries#museumfromhome#archives#genealogy#militaryhistory#folklore#familystories#virginiahistory

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rare photo of Grand Duchesses Olga, Tatiana, and Maria Nikolaevna of Russia, summer 1901

Source: Hessian State Archives

#otma#romanov#romanovs#olga nikolaevna#tatiana nikolaevna#maria nikolaevna#1901#official portraits#otmaa#naotmaa#grand duchess Olga nikolaevna of Russia#grand duchess Tatiana nikolaevna of Russia#grand duchess Maria nikolaevna of Russia#hessian state archives#russian imperial family#russian history#Russia#grand duchesses#otm

25 notes

·

View notes

Note

ive seen most romanov family photo albums. does maria (feodorovna) have similar photo albums of her family? and does alix's hesse family also? if so, please link them!! i would love to see more of princess victoria of hesse and her brother ernie/frittie!

I don't know of any private albums that have been put online like with the Romanov photo albums, but you can search the Hessian State Archive here: https://arcinsys.hessen.de/arcinsys/einfachesuche.action

I'm certain Maria Feodorovna had plenty of albums, too, but I don't know of any that are available online. You can search some of her sister Queen Alexandra's albums here: https://www.rct.uk/collection/search#/page/1

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

♡︎ EXTREMELY rare (and clear) photo of Princess Elisabeth of Hesse and By Rhine (1895-1903) in 1903 ♡︎

Source: my lucky day at the Hessian State Archives

(@princesselisabethofhesse)

#IM SCREAMING 😱🤍✨#This is just amazing!#princess elisabeth of hesse#Ella of hesse#elisabeth of hesse#hessian royal family#hessian state archives#hesse#princess elisabeth#favs#1903#rare

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

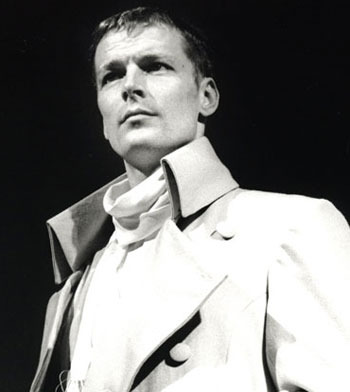

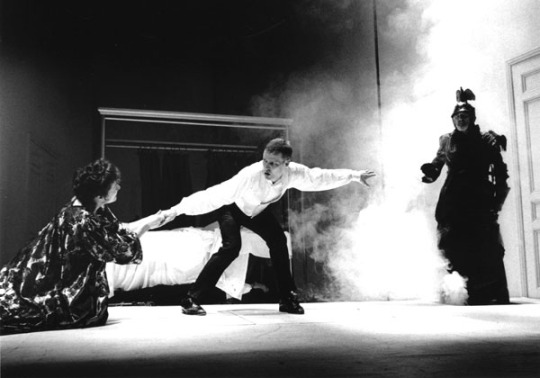

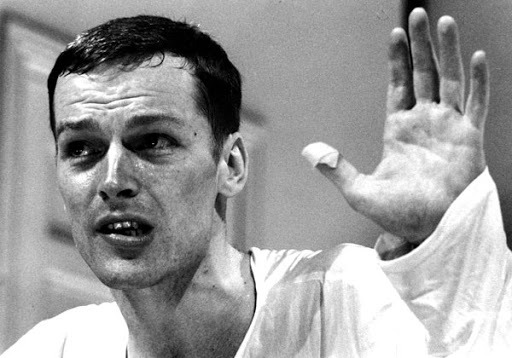

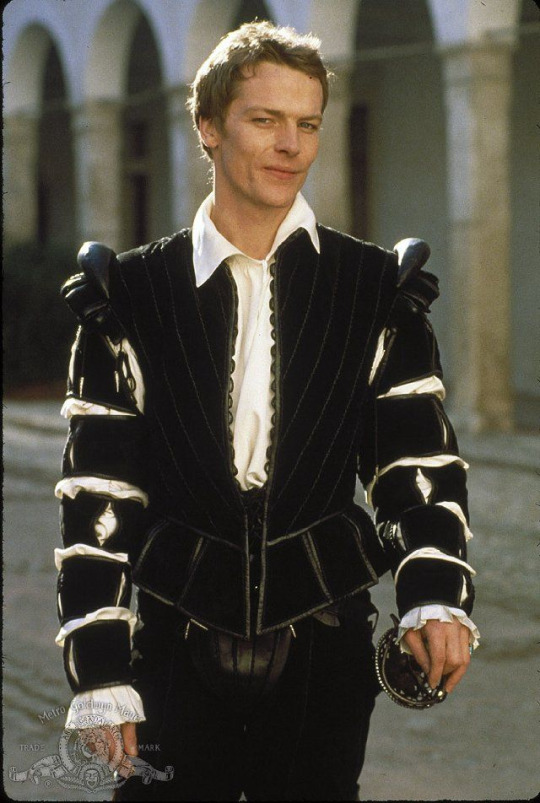

Iain Glen nailing Hamlet (1991)

In 1991, after winning the Evening Standard Film Award for Best Actor, Iain Glen gave his soulful all, not on the stage in London, no, not yet, though really he could have, but at the Old Vic in Bristol, donning the persona of the Dane, Hamlet. He won the Special Commendation Ian Charleson Award* for his performance and yet it appears we will never see but stills from this production as no video recording was made, not even by and for the company. The University of Bristol has the archives of the production: the playbook, the programme and black and white stills. The V&A archives have the administrative papers. In our day and age, this sad evanescent corporeal sate of affairs is unimaginable. The memory of the play, of this performance fading away? We rebel against the very thought. We brandish our cell phones and swear we shall unearth and pirate its memory, somehow, somewhere. Even if we have to hypnotize patrons or pull out the very hearts of those who saw Iain Glen on stage, those few, those happy few, to read into their very memory and pulsating membrane just how brilliant he was. Because he was, he was. That’s what they’ll all tell you...

Below, those pics and testimonies....

*(The Charleson Awards were established in memory of Ian Charleson, who died at 40 from Aids while playing Hamlet at the National Theatre in 1989)

- Iain Glen is a rampaging prince, quixotic, technically sound, tense as a coiled spring, funny. ‘To be, or not to be’ results from throwing himself against the white walls, an air of trembling unpredictability is beautifully conveyed throughout. ‘Oh, what a rogue and peasants slave’ is blindingly powerful. My life is drawn in angrily modern post Gielgud Hamlets: David Warner, Nicol Williams, Visotsky, Jonathon Price. Iain Glen is equal to them. He keeps good company. THE OBSERVER, Michael Coveney

- Paul Unwin’s riveting production reminded me more strongly than any I have ever seen that the Danish Court is riddled with secrecy. Politics is a form of hide and seek: everyone stealthily watches everyone else. Iain Glen’s Hamlet is a melancholic in the clinical sense: his impeccable breeding and essential good nature keep in check what might be an approaching breakdown. His vitriolic humour acts as a safety valve for a nagging instability, his boyish charm is deployed to placate and deceive a hostile and watchful world. Glen brings out Hamlet’s fatal self absorption: the way he cannot help observing himself and putting a moral price tag on every action and failure. He is a doomed boy. And his chill but touching calm at the end is that of a man who has finally understood the secrets behind the closed doors. The Sunday Times, John Peter

- This is an excellent production of Hamlet from the Bristol Old Vic. The director Paul Unwin and his designer Bunnie Christie have set the play in turn of the century Europe. Elsinore is a palace of claustrophobically white walls and numerous doors. All this is handled with a light touch, without drawing attention away from the play. Our first encounter with Hamlet shows him bottled up with rage and grief. Glen gives a gripping performance. The self-dramatising side of the character is tapped to the full by this talented actor. The Spectator, Christopher Edwards

**************************************************************************************************

The following though is my favorite review/article because it situates Iain Glen’s creation is time, in the spectrum of all renowned Hamlets.

How will Cumberbatch, TV’s Sherlock, solve the great mystery of Hamlet? by Michael Coveney - Aug 17, 2015

In 1987, three years before he died, the critic and venerable Shakespearean JC Trewin published a book of personal experience and reminiscence: Five and Eighty Hamlets. I’m thinking of supplying a second volume, under my own name, called Six and Fifty Hamlets, for that will be my total once Benedict Cumberbatch has opened at the Barbican.

There’s a JC and MC overlap of about 15 years: Trewin was a big fan of Derek Jacobi’s logical and graceful prince in 1977 and ended with less enthusiastic remarks about “the probing intelligence” of Michael Pennington in 1980 (both Jacobi and Pennington were 37 when they played the role; Cumberbatch is 39) and emotional pitch and distraction of Roger Rees in 1984 (post-Nickleby, Rees was 40, but an electric eel and ever-youthful).

I started as a reviewer in 1972 with three Hamlets on the trot: the outrageous Charles Marowitz collage, which treats Hamlet as a creep and Ophelia as a demented tart, and makes exemplary, equally unattractive polar opposites of Laertes and Fortinbras; a noble, stately Keith Michell (with a frantic Polonius by Ron Moody) at the Bankside Globe, Sam Wanamaker’s early draft of the Shakespearean replica; and a 90-minute gymnastic exercise performed by a cast of eight in identical chain mail and black breeches at the Arts Theatre.

This gives an idea of how alterable and adaptable Hamlet has been, and continues to be. There are contestable readings between the Folios, any number of possible cuts, and there is no end of choice in emphasis. Trewin once wrote a programme note for a student production directed by Jonathan Miller in which he said that the first scene on the battlements (“Who’s there?”) was the most exciting in world drama; the scene was cut.

And as Steven Berkoff pointed out in his appropriately immodestly titled book I Am Hamlet (1989), Hamlet doesn’t exist in the way Macbeth, or Coriolanus, exists; when you play Hamlet, he becomes you, not the other way round. Hamlet, said Hazlitt, is as real as our own thoughts.

Which is why my three favourite Hamlets are all so different from each other, and attractive because of the personality of the actor who’s provided the mould for the Hamlet jelly: my first, pre-critical-days Hamlet, David Warner (1965) at the Royal Shakespeare Company, was a lank and indolently charismatic student in a long red scarf, exact contemporary of David Halliwell’s Malcolm Scrawdyke, and two years before students were literally revolting in Paris and London; then Alan Cumming (1993) with English Touring Theatre, notably quick, mercurial and very funny, with a detachable doublet and hose, black Lycra pants and bovver boots, definitely (then) the glass of fashion, a graceful gender-bender like Brett Anderson of indie band Suede; and, at last, Michael Sheen (2011) at the Young Vic, a vivid and overreaching fantasist in a psychiatric institution (“Denmark’s a prison”), where every actor “plays” his part.

These three actors – Warner, Cumming, Sheen – occupy what might be termed the radical, alternative tradition of Hamlets, whereas the authoritative, graceful nobility of Jacobi belongs to the Forbes Robertson/John Gielgud line of high-ranking top drawer ‘star’ turns, a dying species and last represented, sourly but magnificently, by Ralph Fiennes (1995) in the gilded popular palace of the Hackney Empire. Fiennes, like Cumberbatch, has the sort of voice you might expect a non-radical, traditional Hamlet to possess.

But if you listen to Gielgud on tape, you soon realise he wasn’t ‘old school’ at all. He must have been as modern, at the time, as Noel Coward. Gielgud is never ‘intoned’ or overtly posh, he’s quicksilver, supple, intellectually alert. I saw him deliver the “Oh what a rogue and peasant slave” soliloquy on the night the National left the Old Vic (February 28, 1976); he had played the role more than 500 times, and not for 37 years, but it was as fresh, brilliant and compelling as if he had been making it up on the spot.

Ben Kingsley, too, in 1975, was a fiercely intelligent Royal Shakespeare Company Hamlet, and I saw much of that physical and mental power in David Tennant’s, also for the RSC in 2008, with an added pinch of mischief and irony. There’s another tradition, too, of angry Hamlets: Nicol Williamson in 1969, a scowling, ferocious demon; Jonathan Pryce at the Royal Court in 1980, possessed by the ghost of his father and spewing his lines, too, before finding Yorick’s skull in a cabinet of bones, an ossuary of Osrics; and a sourpuss Christopher Ecclestone (2002), spiritually constipated, moody as a moose with a migraine, at the West Yorkshire Playhouse.

One Hamlet who had a little of all these different attributes – funny, quixotic, powerful, unhappy, clever and genuinely heroic – was Iain Glen (1991) at the Bristol Old Vic, and I can imagine Cumberbatch developing along similar lines. He, like so many modern Hamlets, is pushing 40 – as was Jude Law (2009), hoary-voiced in the West End – yet when Trevor Nunn cast Ben Whishaw (2004) straight from RADA, aged 23, petulant and precocious, at the Old Vic, he looked like a 16-year-old, and too young for what he was saying. It’s like the reverse of King Lear, where you have to be younger to play older with any truth or vigour.

Michael Billington’s top Hamlet remains Michael Redgrave, aged 50, in 1958, as he recounts in his brilliant new book, The 101 Greatest Plays (seven of the 101 are by Shakespeare); Hamlet, he says, more than any other play, alters according to time as well as place.

So, Yuri Lyubimov’s great Cold War Hamlet, the prince played by the dissident poet Vladimir Visotsky, was primarily about surveillance, the action played on either side of an endlessly moving hessian and woollen wall. And in Belgrade in 1980, shortly after the death of Tito, the play became a statement of anxiety about the succession.

There’s a mystery to Hamlet that not even Sherlock Holmes could solve, though Cumberbatch will no doubt try his darndest – even if he finds his Watson at the Barbican (Leo Bill is playing Horatio) more of a hindrance than a help; there are, after all, more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in his friend’s philosophy.

*************************************************************************************************

Oh! Did I say that we were never going to see Iain Glen in the skin of the great Dane? Tsk. How silly of me. Meet IG’s Hamlet in Tom Stoppard’s postmodern theatrical whimsy ROSENCRANTZ AND GUILDENSTERN ARE DEAD, shot the year before the Bristol play.

Though almost surreal and most often funny as the film follows the Pulp Fiction-like misadventures of two forgettable Shakespearian characters, crossing paths with other more or less fortunate characters, their time with Hamlet makes us privy to the Dane as we never quite see him in the Bard’s play... but for one memorable scene, in which Iain Glen absolutely nails it, emoting the famous “To be or not to be” which you see tortures his soul, brings tears to his eyes and contorts his mouth; the moment made all the more memorable by the fact that it is a silent scene. You never hear him utter the famous line, but you see the words leave his lips and feel them mark your soul.

I’m kinda telling myself that it’s 1991 and I’m sitting in the Old Vic, in Bristol, not London. Not yet.

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

1899

Portrait of Princess Elisabeth of Hesse

Portrait of Princess Elisabeth of Hesse by court painter Josefine Swoboda (1861-1924).

Watercolour.

At present, this portrait belongs to the House of Hesse and is kept in Darmstadt.

It was probably made in Summer 1899, while Elisabeth stayed with her parents at Windsor visiting Queen Victoria. Apparently Swoboda made more than one copy of the same portrait. In fact, the copy made for Queen Victoria is housed in the Print Room at Windsor Castle, where it can be seen by appointment:

sources: first portrait, Thomas Aufleger’s latest book “Geschehnisse und Menschen. Erinnerungen von Ernst Ludwig von Hessen und bei Rhein”. ©Hessian State Archive; second portrait, Royal Collection Trust.

8 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

(via (116) Explanatory video of the Hessisches Landesarchiv (Hessian State Archives) - YouTube)

1 note

·

View note