#Herbert von Karajan

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

youtube

Bon Soir 💙 🎼🎻👌

Herbert von Karajan 🎵 Also Sprach Zarathustraby

(Avec Wiener Philharmoniker)

Animation de Rui Barbosa

#classic music#herbert von karajan#clipanim#also sprach zarathustra#richard strauss#poème symphonique#wiener philharmoniker#rui barbosa#art#clip music anim#youtube#bon soir#fidjie fidjie

26 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

now i gotta follow up with my fave production ever hands down timestamped for your convenience

👆 look at the breathing technique and checking up on the conductor it's so sexy 😭

this finale is straight up goosebumps things do not end well for Don Giovanni 👇

youtube

#and samuel ramey as Don Giovanni also 👌👌👌#don giovanni#ferrucio furlanetto#samuel ramey#herbert von karajan#wolfgang amadeus mozart#opera#Youtube

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

YouTube just randomly offered this clip to me.

One of the greatest African-American opera singers, Grace Bumbry, in Herbert von Karajan's 1967 Vienna production of Carmen: just 30 years old and utterly lovely.

Her Don José is the great heldentenor Jon Vickers.

The costuming is questionable, I admit. That dress looks more like something Carmen Jones should wear than Bizet's Carmen. But no one can deny the talent on display!

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Sublime Armageddon of my soul.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Verdi- Dies Irae Requiem (Karajan)

Dies iræ, dies illa, Solvet sæclum in favilla: Teste David cum Sibylla.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Herbert von Karajan por Erich Lessing

30 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Loomis Dean. Herbert von Karajan rehearsing ‘Elektra’. Salzburg. 1964

Follow my new AI-related project «Collective memories»

#BW#Black and White#Preto e Branco#Noir et Blanc#黒と白#Schwarzweiß#retro#vintage#Loomis Dean#Herbert von Karajan#Elektra#Salzburg#1964#1960s#60s#portrait#肖像#画像#retrato#Porträt

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dimitri Shostakovich

Sinfonia n. 10

Orquestra Filarmónica de Berlim

Herbert von Karajan

Deutsche Grammophon

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

GLENN GOULD chatting with HERBERT VON KARAJAN on his Berlin Philharmonic debut performance of Beethoven’s Concerto No. 3, May 24, 1957

Note on context, from Karajan's website:

Gould and Karajan seemed to be an unlikely couple for the 1950s public. Gould was seen as an opponent of Karajan’s sound and repertoire but both men admired each other greatly. They met for the first time for three concerts with Beethoven’s 3rd piano concerto in 1957 during Gould’s triumphant Europe tour. In 1982, after Gould's death, Karajan writes of Gould:

When I heard him play, I had a feeling that I was myself playing because his music-making appealed so exactly to my own musical sense.

#crazy that this banger of an event happened and we didnt get a video recording. it'd have done numbers for the ppl (me)#how come i have never talked about karajan hes like one of thee top 10 composers for gouldblogger. writing a karajan post as we speak#herbert von karajan#glenn gould#conductor#pianist#classical music#*

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

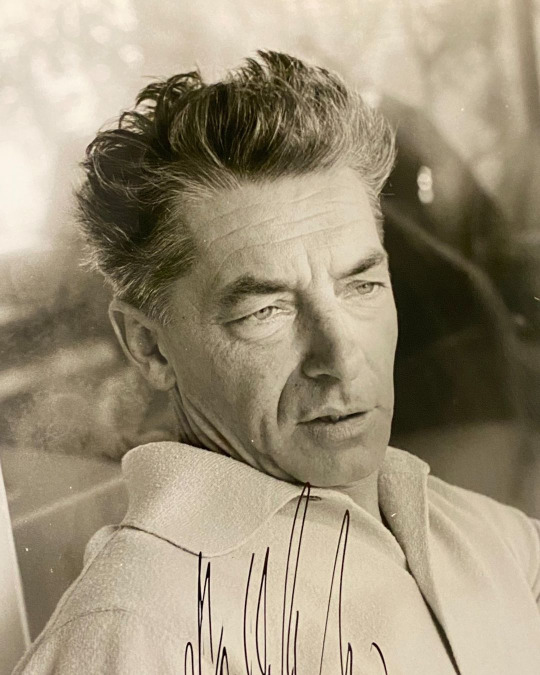

TD in Music History: Legendary 20th Century conductor Herbert von Karajan (1908 - 1989) dies in Austria. During the Nazi Era, a young Karajan (who was always ruthlessly ambitious and highly opportunistic, and who perhaps not surprisingly had been a card-carrying member of the Nazi Party since 1933) debuted at the Salzburg Festival with the Vienna Philharmonic, and during WWII he conducted regularly at the Berlin State Opera and also served as its Kapellmeister. Following the close of his "denazification" proceedings after the war, Karajan went on to enjoy unprecedented global success and famously led the Berlin Philharmonic for a remarkable 34 years. Arguably the single most dominant figure in the entire field of "classical" music from the 1950's right up until his death, Karajan was also probably the single most commercially successful "classical" artist in history. By one count, he sold an incredible 200+ million records! One of Karajan's signature skills as a mature conductor was his ability to extract aurally exquisite sounds from any orchestra. As one of his biographers, Roger Vaughan, opined: "What really rivets one's attention above all else is the sheer beauty and perfection of Karajan's sounds. The softest of pianissimos commands rapt attention. The smooth crescendos peak exactly when they should. The breaks are sliced clean, without the slightest ragged edge to them..." PICTURED: A signed publicity photo of the middle-aged Karajan... ostensibly shown relaxing, but with a rather pensive and troubled look on his face...

#classical music#music history#composer#classical composer#classical studies#classical composers#classical musician#classical musicians#classical history#musician#musicians#historian of music#Herbert von Karajan#von Karajan#conductor#concert#opera#Carnegie Hall#Vienna State Opera#12 London Symphonies#Salzburg Festival#Berlin State Opera#classical#music#history

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

#beethoven#classical music#karajan#symphony#herbert von karajan#orchestra#ludwig van beethoven#ode to joy#Spotify

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

#classical music#music#classical composers#opera#inspiration#art#karajan#herbert von karajan#life quote#quoteoftheday#quotes#conductor

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Those who have achieved all their aims probably set them too low.

- Herbert von Karajan

The Soprano Christa Ludwig described him as ‘Le bon Dieu’, while scores of musicians, reviewers and listeners have long regarded him as simply untouchable in the art of conducting. There was, however, much about Herbert von Karajan that was distinctly ungodlike. Ruthlessly ambitious as a young man and grimly autocratic in his later years, his life story is marked by bitter rivalries, feuds and, most notoriously, membership of the Nazi party.

But then, just listen to the results. It’s fascinating to look at the career, the controversy and the achievements of a conductor who still intrigues fans and detractors like no other musician long after his death.

The early career of Herbert von Karajan continues to be swathed in controversy.

Was he an ardent Nazi or an ambitious opportunist? If he was a zealous party member, should we revere his recordings as much as we do? To what extent should any moral accountability weigh against Karajan’s musical achievement? And how much latitude can we extend to people who have artistically given so generously?

Karajan is not alone in occupying this uncomfortable situation during this era. Similar debate surrounds Richard Strauss, Carl Orff and Karl Böhm. Indeed, Wagner also evokes hostility in certain quarters with regard to his racial sentiments.

When Adolf Hitler swept to power in January 1933, the 24-year-old Austrian Herbert von Karajan had already notched up nearly four seasons as an up-and-coming opera conductor in the South German city of Ulm.

Born in Salzburg in 1908 into a prosperous family, he had demonstrated gifts as a pianist and conductor while studying in Vienna. After graduation, his debut orchestral concert with the Salzburg Mozarteum Orchestra in January 1929, featuring works by R Strauss, Mozart and Tchaikovsky, caused a local sensation and helped to secure him the contract in Ulm.

Karajan seized on the opportunity to learn his trade in Ulm and cut his teeth on much of the operatic repertory from Mozart and Beethoven to Puccini and R . Strauss, including the opera Schwanda der Dudelsacker by the Czech Jewish composer Jaromir Weinberger.

Yet, after the Nazi take-over, Karajan’s future wasn’t assured.

In early 1933, German operatic life was thrown into turmoil as the regime hounded out musicians that were deemed politically and racially unacceptable, and also pursued a protectionist policy to limit employment for non-Germans.

Against this context, Karajan’s decision to join the Nazi Party in Salzburg in April 1933 should be understood as an opportunistic move which was probably designed to safeguard his position at Ulm. Whether it also signalled enthusiasm for Nazi policy is open to speculation, though he no doubt hoped that the strong-arm methods of the Nazis would bring cultural stability to Germany.

Karajan retained his Ulm job for a further season, during which he expanded his repertory to include a praised account of Strauss’s opera Arabella. But in March 1934 he was fired for professional intrigue involving a potential Jewish rival.

He did not have to wait long for a new post. Three months later he was made general music director in Aachen.

Working in a larger theatre enabled Karajan to tackle more ambitious repertory, such as Wagner’s Ring cycle, Verdi’s Otello and Strauss’s Elektra. He also consolidated his reputation in the concert hall, taking charge of Aachen’s annual season of orchestral and choral concerts. One pre-condition for accepting was that he should re-apply for membership of the Nazi Party, his earlier membership in Salzburg having lapsed. This was confirmed in March 1935.

Although in his denazification trial in March 1946 Karajan argued that he had joined the Party to further his career, he could not escape his obligation as Aachen’s general music director to provide the musical background for political occasions.

On 29 June 1935 he took part in a huge open-air orchestral and choral concert that celebrated the NSDAP Party Day and at a similar ceremony four years later he conducted the close from Wagner’s Meistersinger. But his concert programmes seemed untainted by political interference – works by Debussy, Ravel, Kodály and Stravinsky rubbed shoulders with German ones. In 1938 he flouted the law by programming Dukas’s Sorcerer’s Apprentice. Party authorities must have overlooked that Dukas was of Jewish descent.

Karajan conducts Dvořák’s “New World” Symphony No. 9, performed by the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra

By 1937 Karajan’s achievements in Aachen were attracting national interest.

In a special edition devoted to Germany’s conducting legacy, the journal Die Musik singled him out as a man who ‘can lead the new organisation of our cultural life in the spirit and direction which National Socialism demands’. Concert engagements in Gothenburg, Vienna, Amsterdam, Brussels and Stockholm helped to spread his name beyond Germany.

Yet for all this, Karajan set his sights even higher by hoping to make an impact in Berlin. This ambition was realised in 1938 with a ‘Strength through Joy’ concert with the Berlin Philharmonic and engagement as conductor at the Berlin State Opera in Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde in October of the same year.

Karajan may not have anticipated that with his move to Berlin he was stepping into a political cauldron over which he would have little control.

It began with a review of his Tristan which appeared in the Berliner Zeitung. Under the title ‘Karajan the Miracle’, the critic Edwin von der Nüll lavished praise on the performance suggesting that in conducting Wagner’s score from memory the 30-year-old conductor had achieved ‘something our great men in their fifties might envy’.

This was calculated to offend the conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler who had previously ruled the roost in the same theatre. Karajan was set up as a pawn in the struggle for control of Berlin’s cultural institutions between Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels, a Furtwängler supporter, and Minister of Interior Hermann Goering, the patron of the Berlin State Opera.

In June 1939 Karajan conducted Wagner’s Die Meistersinger at the State Opera without a score. The performance collapsed when the baritone, a drunk Rudolf Bockelmann, made a serious error. Alas Hitler, in the audience, was furious, blaming instead Karajan’s insufficiently Germanic approach to Wagner by conducting from memory.

Further problems arose over his marriage in 1942 to the quarter Jewish Anita Gütermann, technically against the law.

Yet, despite this and the continuing hostility and suspicion of Goebbels and Hitler and Furtwängler’s jealousy, his career prospered during the war. He conducted Bach’s B Minor Mass in Paris for the occupying German soldiers in 1940 and returned to the French capital in 1941 to present his performance of Tristan with the Berlin State Opera.

From 1940 he appeared in Italy and gave concerts in Romania and Hungary. A major achievement was to secure popularity for Orff’s Carmina Burana, a score that had aroused some hostility from the Nazi hierarchy at its first performance in 1937 before Karajan’s performances in Aachen and Berlin during the early 1940s.

Driven by a fanatical love of music and a desire to advance his career, there’s little doubt that Karajan’s involvement with the Nazi regime was opportunistic.

Doubtless though there were also areas of Nazi policy that may well have chimed in with his own views. At the same time falling foul of the regime on occasions, his personal ideology can be best described as a montage of greys; nothing is ever clear-cut and nor perhaps should be our assessment of his work.

#karajan#herbert von karajan#quote#conductor#music#german#nazi germany#nazism#opera#orchestra#classical music#history#arts#culture

37 notes

·

View notes