#HOPE an educational NGO in Pakistan

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

STORY OF MISBAH SHABBIR AN UNDERPRIVILEGED STUDENT AT HOPE HIGH SCHOOL, ZIA COLONY, KORANGI.

This is the success story of Misbah Shabbir D/O Muhammad Shabbir, who belongs to Karachi. Misbah faced to tough time during her childhood, her mother had passed away she was very young, and her father is a labour who earns daily wage salary. Misbah has always had the interest in studies, she was a smart student, and used to get good grades, her father wanted her to study well, but could not…

View On WordPress

#Dr.Mubina Agboatwalla#Dr.Mubina Agboatwalla the child specialist in Karachi#Education#Health#HOPE#HOPE an educational NGO in Pakistan#HOPE an Health NGO in Pakistan#HOPE NGO in Pakistan#the child specialist in Karachi

0 notes

Text

Build an Orphanage in Pakistan: A Lifeline for Homeless Children

Build an Orphanage in Pakistan: A Lifeline for Homeless Children

Building an orphanage in Pakistan is not just a noble endeavor; it is a crucial necessity in a country where thousands of children find themselves without a home, family, or support. The harsh realities of life force many young ones to fend for themselves, and the absence of stable homes often leads them to the streets. As the world progresses, the need to support and nurture these vulnerable children becomes increasingly urgent. This article explores the importance of establishing orphanages for homeless people in Pakistan, the impact of such facilities, and how you can contribute to this significant cause.

The Current Situation of Orphans in Pakistan

Pakistan is home to millions of children who are orphans, either due to the loss of parents from illness, accidents, or socio-economic challenges. The lack of adequate resources and social structures to support these children leaves them vulnerable to exploitation, poverty, and neglect. According to various reports, it is estimated that around 4.2 million children are orphaned in Pakistan, with many living in deplorable conditions.

The social stigma surrounding orphaned children often leads to their marginalization, making it essential to create dedicated spaces where they can receive the care and attention they need. An orphanage serves not just as a home, but also as a nurturing environment that can provide education, emotional support, and a sense of belonging.

Why Build an Orphanage in Pakistan?

A Safe Haven: An orphanage offers a safe space for children to live and grow, away from the dangers of the streets. It provides them with shelter, food, and basic amenities that every child deserves.

Access to Education: One of the significant benefits of an orphanage is the provision of education. Many orphaned children miss out on schooling due to financial constraints or lack of parental support. An orphanage can facilitate education, helping children develop essential skills for a brighter future.

Emotional and Psychological Support: Children in orphanages receive emotional support from trained staff and caregivers. This nurturing environment helps them cope with the trauma of losing their parents and instills a sense of hope and belonging.

Health and Nutrition: Many orphans suffer from malnutrition and lack access to healthcare. By establishing an orphanage, you can ensure that children receive proper nutrition and medical care, promoting their overall well-being.

Community Building: An orphanage can act as a community hub, fostering relationships among children and staff. This sense of community is vital for their social development and helps them build lifelong friendships.

The Process of Building an Orphanage

Creating an orphanage requires careful planning and execution. Here are the essential steps involved in building an orphanage in Pakistan:

1. Research and Feasibility Study

Before embarking on this journey, it's crucial to conduct thorough research. Assess the needs of the local community and identify areas with a high concentration of orphaned children. Engaging with local NGOs and welfare organizations can provide insights into the existing gaps and challenges faced by orphans.

2. Develop a Mission and Vision

Establish a clear mission and vision for the orphanage. This will guide your efforts and ensure that the facility meets the needs of the children effectively. Your mission could focus on providing a safe environment, educational opportunities, and holistic development for orphans.

3. Secure Funding

Building an orphanage requires significant financial resources. You can seek funding through various channels, including:

Donations: Reach out to individuals, businesses, and philanthropic organizations willing to contribute to your cause.

Crowdfunding: Utilize online platforms to raise awareness and funds for your orphanage project.

Grants: Explore government and international grants aimed at supporting child welfare initiatives.

4. Find a Suitable Location

The location of the orphanage is critical. It should be accessible, safe, and spacious enough to accommodate children and staff. Consider areas with a supportive community that can contribute to the orphanage's success.

5. Design and Construction

Work with architects and builders to design a facility that meets the needs of children. The orphanage should include living quarters, educational spaces, recreational areas, and facilities for healthcare and nutrition. Ensure that the design promotes a welcoming and nurturing environment.

6. Staff Recruitment

Hiring qualified and compassionate staff is vital for the success of the orphanage. Recruit caregivers, educators, and medical professionals who are passionate about working with children. Provide them with training on child psychology and welfare to ensure they can offer the best support.

7. Establish Partnerships

Collaborate with local NGOs, schools, and healthcare providers to enhance the services offered by the orphanage. Partnerships can help provide additional resources, expertise, and support for the children.

8. Launch and Promote

Once the orphanage is ready, plan a launch event to raise awareness about your initiative. Invite local community members, potential donors, and the media to showcase the importance of building an orphanage for homeless people.

The Impact of an Orphanage

Building an orphanage in Pakistan can create a ripple effect of positive change. The impact goes beyond the immediate needs of the children; it influences the entire community. Here’s how:

Empowerment: By providing education and skills training, an orphanage empowers children to become self-sufficient and productive members of society.

Social Change: Raising awareness about the plight of orphans encourages community involvement and support, fostering a culture of compassion and social responsibility.

Long-term Benefits: Investing in the lives of orphaned children today leads to long-term societal benefits. Educated and empowered individuals contribute positively to their communities, breaking the cycle of poverty.

How You Can Help

If you resonate with the cause of building an orphanage in Pakistan, there are several ways you can contribute:

Donate: Financial contributions can significantly impact the construction and operation of the orphanage. Every bit helps, no matter how small.

Volunteer: Offer your time and skills to assist in various aspects of the orphanage, from construction to educational support.

Raise Awareness: Use your social media platforms and networks to raise awareness about the need for orphanages for homeless people in Pakistan.

Advocate: Engage with local leaders and policymakers to promote child welfare initiatives and advocate for the rights of orphans.

Conclusion

The urgent need to build an orphanage in Pakistan cannot be overstated. It is a step towards creating a brighter future for countless orphaned children who deserve love, support, and opportunities. By providing a nurturing environment through an orphanage, we can ensure that these vulnerable children grow up with hope, dignity, and the chance to thrive. Together, we can make a difference in their lives, transforming their futures and our society as a whole.

0 notes

Text

Building an Orphanage in Pakistan

Building an Orphanage in Pakistan:

Keyword Variations: build an orphanage in Pakistan, orphanage in Pakistan, building an orphanage

Pakistan faces an overwhelming challenge of providing care and support to its vulnerable and orphaned children. With an estimated 4.2 million orphans living in the country, there is an increasing need for dedicated institutions that can offer shelter, education, and hope for a brighter future. Building an orphanage in Pakistan is a noble cause that can significantly impact the lives of these children.

In this guide, we will explore the essential steps, challenges, and considerations when building an orphanage in Pakistan.

1. Why Build an Orphanage in Pakistan?

The primary reason to build an orphanage in Pakistan is to address the rising number of orphaned children who lack basic necessities like food, shelter, education, and healthcare. Factors such as poverty, natural disasters, and armed conflicts contribute to the high number of orphans in the country. These children often face neglect, exploitation, and social marginalization, and orphanages can provide them with a safe, nurturing environment.

In addition, building an orphanage contributes to the country’s social development by supporting one of the most vulnerable segments of society. Providing children with proper care, education, and skills development can break the cycle of poverty and ensure they grow up to become contributing members of society.

2. Steps to Building an Orphanage in Pakistan

Building an orphanage is a complex and multi-faceted process that requires thorough planning, legal understanding, and community engagement. Below are the key steps to follow:

2.1. Create a Vision and Mission

The first step in building an orphanage in Pakistan is to define your vision and mission. What kind of orphanage do you want to build? Will it focus on providing a home for abandoned children, or will it also offer educational and vocational training? Having a clear mission will guide every subsequent decision.

2.2. Legal Framework and Registration

Before you can start building an orphanage in Pakistan, it’s essential to navigate the legal requirements. Pakistan has specific regulations for establishing charitable organizations, including orphanages. Here’s what you need to do:

Register a Non-Governmental Organization (NGO): You must register your orphanage as an NGO with relevant governmental bodies like the Pakistan Centre for Philanthropy or the Securities and Exchange Commission of Pakistan (SECP). This registration ensures compliance with local laws.

Obtain Permits and Approvals: Depending on your orphanage's location, you’ll need land permits, construction approvals, and health & safety certifications.

Compliance with Child Protection Laws: Ensure your orphanage abides by child protection laws, such as the Punjab Destitute and Neglected Children Act, to guarantee that children receive proper care and support.

2.3. Select the Right Location

Location plays a critical role in the success of an orphanage. Look for a location that offers:

Accessibility: The site should be easily accessible for donors, volunteers, and staff. Major cities like Lahore, Karachi, and Islamabad offer better connectivity and resources.

Safety: Ensure that the area is safe and secure, free from political instability or crime.

Proximity to Resources: Being near schools, hospitals, and other essential services is crucial for providing quality care to the children.

2.4. Fundraising and Budgeting

To successfully build an orphanage in Pakistan, you’ll need substantial funds. Here are some methods to raise funds:

Crowdfunding: Use platforms like GoFundMe, LaunchGood, or local crowdfunding sites to garner donations from people worldwide.

Donor Networks: Approach local businesses, philanthropists, and international charities for sponsorships and donations.

Grants and Aid: Some government and international organizations offer grants for building orphanages. Research grants from organizations such as UNICEF, Save the Children, and the Pakistan Bait-ul-Mal.

Budgeting should include costs for:

Land purchase or lease

Construction

Furniture and equipment

Staff salaries

Daily operations (food, utilities, healthcare)

3. Designing the Orphanage

Designing an orphanage involves creating a space that’s safe, comfortable, and nurturing for children. Below are some important design considerations:

3.1. Capacity

Estimate how many children the orphanage will house. Start small, perhaps with 20 to 50 children, and expand as your funding grows.

3.2. Facilities

An ideal orphanage should include:

Dormitories: Spacious, well-ventilated rooms for children to sleep in.

Classrooms: Learning spaces equipped with basic educational materials.

Play Areas: Outdoor and indoor play areas where children can exercise and socialize.

Healthcare Rooms: A small medical room for treating minor injuries or illnesses.

Dining Hall and Kitchen: A communal space for meals with a kitchen that can cater to the needs of all the children.

Security and Surveillance: The orphanage should have secure entry points and surveillance systems to ensure the safety of the children.

4. Staffing and Management

Running an orphanage requires a dedicated team of staff and volunteers who are committed to the cause. Staff members should include:

Caregivers and Social Workers: They play a critical role in the day-to-day care of the children.

Teachers and Tutors: If your orphanage includes educational programs, hiring qualified educators is essential.

Medical Staff: Nurses or part-time doctors should be available for children’s health needs.

Administrative Staff: For handling finances, legal compliance, and donor relations.

Provide regular training to staff members on child care, first aid, emotional support, and legal responsibilities.

5. Sustainability and Long-Term Planning

Once your orphanage is built, the focus shifts to sustainability and long-term management. Some important

0 notes

Text

Building Hope: The Need to Build an Orphanage in Pakistan

n the heart of Pakistan, countless children face the harsh realities of life without parental care. The orphaned children in this beautiful country are not just statistics; they are individuals with dreams, hopes, and aspirations. Their circumstances often leave them vulnerable and in dire need of support. To address this urgent situation, we must come together to build an orphanage in Pakistan, providing a safe haven for these innocent lives.

The Current State of Orphaned Children in Pakistan

Pakistan, with a population exceeding 220 million, faces numerous social challenges, including poverty, lack of education, and inadequate healthcare. Among these challenges, the plight of orphaned children stands out. According to estimates, over 3 million children in Pakistan are orphaned, with many living on the streets or in precarious conditions. These children are often deprived of basic necessities such as food, shelter, and education.

The emotional and psychological trauma these children endure can have lasting effects. They often lack the love and support of a family, which is crucial for healthy development. Furthermore, without proper guidance, many of these children fall prey to exploitation, trafficking, and abuse. Therefore, it becomes imperative to build an orphanage in Pakistan, a sanctuary that can provide them with the care and nurturing they desperately need.

The Importance of Building an Orphanage

When we build an orphanage in Pakistan, we create a safe environment where children can thrive. An orphanage serves not only as a shelter but also as a community that fosters growth, learning, and love. Here are some compelling reasons why building an orphanage is essential:

Providing Basic Needs: A well-structured orphanage ensures that children receive nutritious meals, healthcare, and education. These basic needs are critical for their physical and mental well-being.

Creating a Sense of Belonging: Orphanages can create a family-like atmosphere where children form bonds with caregivers and peers. This sense of belonging can significantly improve their emotional health.

Access to Education: Education is a powerful tool for breaking the cycle of poverty. An orphanage can provide access to quality education, empowering children to become self-sufficient and productive members of society.

Psychosocial Support: Children in orphanages can benefit from counseling and support services that address their emotional needs. Trained professionals can help them cope with their past traumas and build resilience.

Skill Development: Orphanages can implement programs that teach children essential life skills, such as vocational training, financial literacy, and social skills. This equips them for future success. building an orphanage

The Role of the Community

Building an orphanage in Pakistan requires the active participation of the community. It’s not just about constructing a building; it’s about creating a nurturing environment. Community involvement is crucial for the success of any orphanage. Here’s how the community can contribute:

Awareness Campaigns: Raising awareness about the plight of orphaned children can mobilize support. Community members can organize events, workshops, and discussions to highlight the importance of building an orphanage.

Fundraising Initiatives: Funding is a significant challenge when building an orphanage. Local businesses, individuals, and NGOs can collaborate to organize fundraising events. Every donation, no matter how small, can make a difference.

Volunteering: Community members can volunteer their time and skills to support the orphanage. Whether it’s tutoring children, organizing recreational activities, or helping with administrative tasks, every effort counts.

Advocacy: Advocating for orphaned children at local and national levels can influence policies and attract resources. Engaging with local government officials and NGOs can foster collaboration.

Partnerships: Collaborating with existing organizations can streamline efforts. Partnering with NGOs that specialize in child welfare can provide valuable resources and expertise. orphanage in pakistan

Steps to Build an Orphanage in Pakistan

Building an orphanage is a significant undertaking that requires careful planning and execution. Here’s a step-by-step guide to help turn this vision into reality:

Conduct a Needs Assessment: Identify the specific needs of orphaned children in the target area. Gather data on the number of orphaned children, existing facilities, and available resources.

Develop a Business Plan: Create a detailed business plan outlining the mission, vision, and goals of the orphanage. Include information on funding sources, operational costs, and staffing needs.

Secure Funding: Explore various funding options, including grants, donations, and crowdfunding. Present a compelling case to potential donors, emphasizing the impact their contributions will make.

Choose a Location: Select a suitable location that is accessible and safe for children. Consider factors such as proximity to schools, healthcare facilities, and the community.

Design the Facility: Work with architects and builders to design a facility that meets the needs of children. Ensure it includes living quarters, classrooms, recreational areas, and healthcare facilities.

Recruit Staff: Hire qualified staff who are passionate about child welfare. This includes caregivers, teachers, counselors, and administrative personnel.

Establish Policies and Procedures: Develop clear policies and procedures for the orphanage. This includes guidelines for admission, care, education, and safety.

Launch Awareness Campaigns: Promote the orphanage within the community to attract support and resources. Use social media, local events, and traditional media to spread the word.

Open the Orphanage: Once everything is in place, officially open the orphanage and begin welcoming children. Celebrate the occasion with the community to foster a sense of ownership.

Monitor and Evaluate: Continuously assess the orphanage’s operations and impact. Gather feedback from staff, children, and the community to improve services.

Success Stories: Orphanages Making a Difference

Several orphanages in Pakistan exemplify the positive impact that such initiatives can have. For instance, SOS Children’s Village has been successfully providing care for orphaned and abandoned children for decades. Their model emphasizes family-based care, education, and emotional support.

Another notable example is Saylani Welfare International Trust, which runs various programs for orphaned children, including education and vocational training. Their holistic approach empowers children to become self-sufficient and confident individuals.

These success stories demonstrate that building an orphanage in Pakistan can lead to transformative change. When we invest in the future of orphaned children, we invest in the future of our society.

The Ripple Effect of Building an Orphanage

Building an orphanage in Pakistan creates a ripple effect that extends beyond the walls of the facility. As children receive care, education, and support, they grow into empowered adults who can contribute positively to their communities. These individuals become advocates for change, breaking the cycle of poverty and inspiring others to take action.

Moreover, orphanages often engage with local communities, fostering collaboration and awareness. As the community rallies around the cause, more people become involved in improving the lives of children, creating a culture of compassion and support.

Conclusion

The need to build an orphanage in Pakistan is urgent and essential. By providing a safe and nurturing environment for orphaned children, we can change lives and offer hope for a brighter future. It’s a collective responsibility that requires the involvement of individuals, businesses, and organizations. Together, we can create a community that values every child and ensures that no child is left behind.

As we embark on this journey, let us remember that every action counts. Whether it’s raising awareness, donating funds, or volunteering time, each effort contributes to building a better tomorrow for the children who need it most. Let’s come together to build an orphanage in Pakistan and create a legacy of love, hope, and empowerment.

0 notes

Text

Escaping Afghanistan: Refugee Filmmaker Nelofer Pazira Pens a Letter of Hope to the Endangered Afghan Women

As told to Hafsa Lodi

As a teenager, Nelofer Pazira fled Afghanistan. But while she may have left a nation in turmoil, her attachment to her roots and homeland has been unwavering. A journalist and filmmaker, Pazira co-produced, co-directed, and starred in the 2003 documentary Return to Kandahar, which tracks her journey trying to return to Afghanistan to save her childhood friend. In 2006, she released her award-winning memoir, A Bed of Red Flowers: In Search of My Afghanistan. She also founded a charity to help educate Afghan women in rural areas. Amid the Taliban takeover, Pazira reflects on the strength and resilience of Afghan women, who are gravely anxious to see what the future holds for them under this repressive regime.

(Nelofer Pazira filming Return to Kandahar.)

"I grew up in Kabul during the Soviet war and Russian occupation of Afghanistan. The wars were starting in the countryside, and we would hear about them from BBC Persian services, which my father would listen to at 8pm every night. The signal was very bad, sometimes it would disappear, but that was the only source of real information we had.

I was in high school, and at that time how we wanted to dress and whether we chose to study was left up to women and their families – there was no government interference in any of those matters. I joined an Islamic youth group to resist the occupation of the Russians, because as Afghans we don’t like any occupying forces. Within the group there was no religious dictate or suggestion of any kind of dress code – there were more young women involved than men.

By 1989, the situation had become so difficult that my parents didn’t want to stay in the country anymore. We wore the full burkas to conceal our identities, and left early morning with a smuggler, by foot. We had a small bag with us that had some dried fruit, blankets, and candles. I was 16. I took a pen I used to write with a lot, and my books – at that age small things can be precious to you – but we left everything else behind. We walked for 10 days across the countryside, passed through the government checkpoints and got to Pakistan, and lived there for a year. My father got accepted to go to Canada as a refugee because he was a medical doctor, and we ended up living in that country.

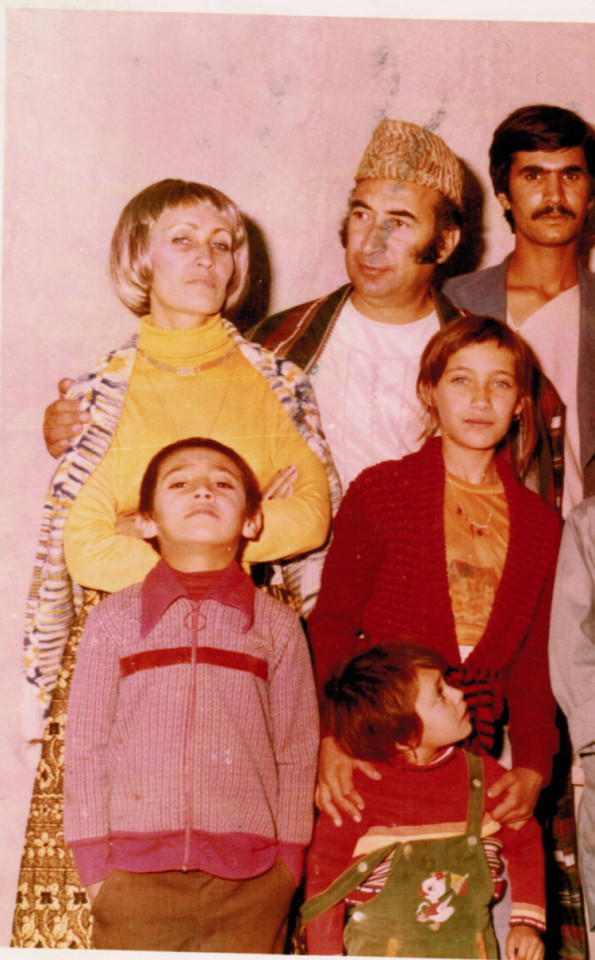

(Pazira [in red vest] with her parents [Jamila and Habibullah Pazira], her younger brother [Hassibullah], younger sister [Mejgan] and a cousin in Kabul, 1980s)

I had a close friend in Kabul and when I arrived in Canada, we started writing letters back and forth – they would take three to four months to arrive; it was never quick. It’s almost difficult to understand that concept now in the age of technology where we just message instantly. My friend lived through the civil war, and I have letters from her that describe the gunmen in the streets fighting against each other, with civilians caught in the middle. Then in 1996 the Taliban came to power, and everything changed – for the worse. She couldn’t leave her home, became depressed, and only after the Taliban had gone, I discovered she had killed herself. Unfortunately, a lot of Afghan women took their own lives during that period, because there was just nothing left.

As women we have the strength to endure and tolerate a lot, but that doesn’t mean we have to. You could have all the strength to fight, but when you take away hope and close that door completely, that strength runs out.

I started a charity, Dyana Afghan Women’s Fund, in memory of my friend. I wanted to help with educating women, but in a sustainable way. I’ve traveled across Afghanistan and everybody I talked to would complain that NGOs just come, give them one class, and then disappear. We worked in remote parts of Afghanistan through local teachers – we would start with one woman, pay her rent for the use of her house as a classroom, and the women in her surrounding would come for two to three hours a day. We also established a small daycare center there so the women wouldn’t be criticised by their families for not looking after their children. We taught them literacy, numeracy, female hygiene, and reproduction – some also wanted to learn how to use computers if they had hopes of getting jobs. But since the return of the Taliban, the teacher has closed her home and our supervisor was just evacuated from Kabul.

My hope is that once we have a bit of certainty about this political situation, we’ll be able to continue the work, because you can evacuate a few thousand, but the country is still there with millions of people. Days and weeks go by, and a girl who was six when the Taliban entered, soon enough is going to be seven, and what happens to her future?

From the moment the Taliban entered Kabul, the impact on women was clear. My aunt in Kabul is a schoolteacher: she says that if they reopen schools to female teachers and students, she will go back – she loves her job. But what about the burka? She’s a modestly dressed woman, and she wears a scarf over her head, but she doesn’t like wearing the burka, she finds it difficult for breathing.

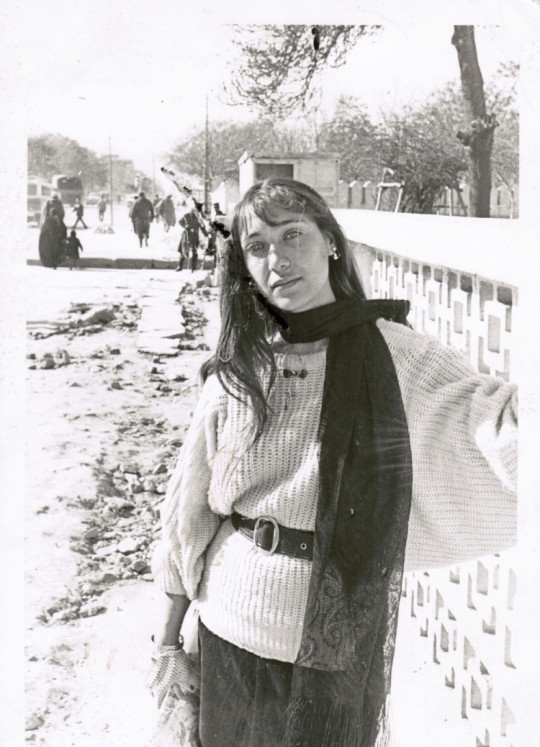

(Pazira in Kabul, winter of 1989)

There’s a real fear right now for women’s safety, security, and freedom. It’s fear of what the Taliban did before – if someone has done something so brutally wrong to you, how can you trust that they will not do it again? Women, especially in Kabul, want assurances. But what kind of assurances can you give them, besides what you show in practice? Everyone’s waiting to see if the Taliban will be how they used to be, or if they will modify and give us some degree of opportunities as women – but even if they do, will their soldiers comply? How much power can they exert over this group of young soldiers who only know how to fight?

If there’s a civil war, what choices will women have? Either flee the country, or hide in their homes. It’s heart-breaking, and this is why I feel angry as a woman: we talk about women’s rights and equality in a kind of polemic, academic way but when it comes to the reality of it, there is not enough we do. That’s my plea to the outside world: instead of just talking about it, find genuine and meaningful ways to provide some degree of support for women. Afghan women are resilient – but they will not be able to survive without any kind of hope or practical support.

You could say that a lot of people didn’t know about it back then, but now, this time around, we have a sense of it, we know what happened in the past. Our hope is that it will never get to that.”

#her mom looks so much like my aunt#even the smug expression its killing me#Canadian#Afghanistan#film#refugees#nelofer pazira#taliban#hafsa lodi#return to Kandahar#women#Kabul#1980s#dyana Afghan women's fund#long post

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Divided Region United by Caste Oppression

The South Asian region is looked at by the world with three intersecting interests. First, the region’s moderate development in infrastructure and welfarism. Second, the multitudes of diversity the region holds. And thirdly, the geopolitical tensions dominated mostly by India-Pakistan war. The troika of South Asia sits between development-culture-politics. However, other regional differences such as India-Nepal trade strife, India-Sri Lanka regional difficulties, Pakistan-Afghanistan do not account to sustaining disagreements. India, Pakistan and Bangladesh occupy overwhelming importance in the regional politics.

South Asian region is home to one fourth humanity of the world. Aside from human capital, there are flora, fauna and natural gifts that this region has as its treasure carefully handed down from over thousand years. Of the 8 countries that are part of South Asia there at least six known countries who retain experiences of age-old discriminations emanating from their native historical context. One of it is oldest surviving discriminatory tactic is caste. Human Rights Watch has identified caste like “corollaries” across South Asia in India, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh.

Caste inspired discrimination is not unique to India, although it offers most fertile space for caste like virus to take birth, thrive and contaminate every person in sight. The history of the region as such has a complex historical political-economy. That is why it is always insightful for one to detangle those past baggages by looking at the political space through the lens of subaltern, the working class, women, and the oppressed.

Each state policy heavily relies on the extraction of labor and abstraction of its value. In a society that hangs on to historical values as sacrosanct, distribution of labor’s value does not feature in its scope. How to credit someone for their labour who are meant to performing the duty as part of ordained duty? Asking for a favor in terms of service from lower considered body is a sin and therefore that body needs to be condemned. Such has been the practice for the most part in the region when it came to invasions and colonization.

Every religions and sects have developed anti-Dalit, casteist tendencies towards the lower considered others even if their scriptures do not have caste-based distinction. Six major religions have assimilated Vedic practices of discriminating people who are lowered as outcaste for their advantage. Although their scriptural doctrine discourages any form of discrimination Jain, Sikh, Muslim, Zoroastrians, and Christians have largely benefitted by assimilating with the caste system.

The hatred and fear of the lower considered caste assigns designated lowest job positions that has no respect and standard wage. The job of cleaning the filth, human waste and animal carcasses are single-handedly done by Dalits in India, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, and Nepal. Due to the draconian rule of Taliban in Afghanistan there are no studies that could explicate the exploitation of caste bodies in the hyper-Islamist violence.

It is because of this the South Asian region is plagued with enumerable hurdles that have limited its overall development. On economic front the GDP per capita approximation is USD $ 7,600 while the US alone has GDP per capita at $60,000. In the global ranking on inequality, poverty and corruption, South Asian region stands as a leader in negative performance indexes.

The primary and secondary educational enrollment is sobering. However, when it comes to the breakup of caste, religion and gender one would see the apparent losses. For India, the Dalit student enrollment slides down from 81% in primary education to less than 11% in graduate education. The pass out rate for Dalit graduates is only 2.24%. In Nepal the primary education enrollment of Dalits and indigenous groups was 34% compared to their population of 57%. While in higher education it was merely 3.8% with a high dropout rate. College level graduation for Dalit in Nepal is depressingly 0.4% Completion of studies is equally low where gender plays an important part of disadvantaging Dalit females further. Along with this the Hill and Terai region's differences recreates more gulf.

Due to border related conflicts, the South Asian region has seen brutal wars since the departure of colonial powers. Luxurious spending on military aggressions makes it difficult to redirect some of those bucks for the social welfare and development of human capital as opposed to exploiting it in senseless battles. War and cross-border conflicts have been cornerstones of some of the hegemonic states in the region. What rationalizes one to impose such draconian policies? I think it is the inherent, imperialistic wishes aided with mistrust of Others.

Buddhist South Asia

There is possibly only one commonality that connects this vast region. It is the rich heritage of indigenously grown Buddhist culture. The Buddhist values have vast expanse over any other colonized religious, spiritual doctrines. And perhaps this is an ideal path to reimagine our current problematics. Buddha’s doctrine not only spread in this region, but it also prospered to give this region an iconic reputation.

In the spread of Buddha’s doctrinaire, through Ashokā one cannot see the colonized brutal invasions unlike other spiritual experiences. And it was Buddha who formally challenged caste on a macro level. It is to his credit that many anti-caste, and acaste initiatives were propagated in an otherwise oppressive Vedic caste society.

Through Buddha we can complicate the history and as well as geography of South Asia. It offers us an opportunity to reclaim a regional past that will usher a sense of belonging through expressions of solidarity and unity. As it stands, South Asia is a deeply divided entity. Apart from government sponsored scholarships and few SAARC-like annual initiatives there are not much people to people interactions. Much of it is mediated with stereotypes of each others propagated by the cultural industry and hostile governments.

Regional blocks like Latin America, Africa, Europe have a sense of belonging to the region. While in the South Asian context, one would not even acknowledge their nationality with the region. A balkanized, sovereign supreme identity of one’s nationalism—of whatever worth is strongly rooted in the individuated South Asian identity. At a recently held 2020 SAARC summit held over video conference, Pakistan's representative, health minister Zafar Mirza lamented, "SAARC region remains the least integrated region in the world". Mirza hoped SAARC can be used for "pooling of resources, expertise, and even financing".

South Asia still remains in a shadow of colonial powers and that is why perhaps the foreign sponsored NGO industry and other capital investment has an unequal balance of power. Development related issues like poverty, atrocity, caste discrimination, religious fundamentalism among others inform the region’s politics. To overcome this dependability and to preserve self as a united, strong block with a vast human reserve and natural abilities the region has every reason to aim for a solid economy rooted on people’s welfare.

This doesn’t happen because caste and its attitudes will continue to control our logics of operation. Caste creates mistrust and lack of faith. Due to this, there is no free sharing of knowledge and mobility of human capital. Caste produced insecure groupings amongst its own citizens in a national framework. Each South Asian country takes itself back every time it employs the creative labor and hardworking individuals to the designated caste jobs. A Brahmin becoming priest, a Baniya holding business and a Dalit or Adivasi doing the inhumane jobs of polluting nature becomes an unnatural organization of productive economy.

This then legitimizes the authority and power brokers to certify their discrimination upon the huge mass of people who could have been trained, equipped and prepared for more innovative tasks. Caste system not only deprives one from exercising their fullest potential, but it creates more barriers for a society to grow as a collective. This then puts the pressure on select few who have taken the responsibility to run the economic affairs. By not including a huge mass of people in formal employment the economic and social elites continue to bear the burden of huge taxes. Caste system disadvantages their own purse, yet the powerholders of caste regime involve in the sadist action of imposing caste punishments upon its own citizens at the cost of their own social, economic worth.

One day this has to end, and it will end. And when the time of reconstructing the society will arise the people who are enjoying their unearned, aristocratic privilege will have to go back and check their vile acts that have imposed such harsher measures on fellow humans. It is upon everyone to eradicate caste; however, the onus is more on the privileged ones as they are most invested in it.

This article is written by Dr. Suraj Yengde, who is an author of bestseller ‘Caste Matters’ and a fellow and postdoc at the Harvard’s Kennedy School.

Naya Patrika Daily published its Nepali translation: https://jhannaya.nayapatrikadaily.com/news-details/911/2020-03-21

1 note

·

View note

Text

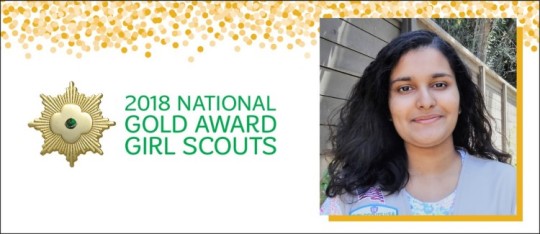

#goldengirls: Fight for Girls

For her Gold Award, Sakshi S. from Girl Scouts of Northern California, created Project GREET (Girl Rights: Engage, Empower, Train), which engages and educates audiences around the world on the root causes of human trafficking and child marriage, the staggering prevalence of the problem, and ways to stop it—all while promoting gender equality.

Her curriculum, “Guidelines to Rehabilitate Young Trafficked Girls,” provided tools, including a website, documentary film, YouTube playlist, and training materials, for crucial job training programs to financially empower both previously trafficked girls and those still at risk. These guidelines, along with her documentary film (for which Sakshi interviewed activists, lawyers, and social workers from around the world), website, and YouTube playlist were distributed to more than 59 partner organizations worldwide and many United Nations delegates from countries such as Thailand, Cuba, Cameroon, Pakistan, Bhutan, Jordan, and more.

Project GREET has already impacted, directly or indirectly, approximately three million people, and will continue to spread awareness and provide urgent solutions for girls at risk of child marriage and human trafficking around the world.

Q: Why did you choose this topic for your Gold Award project? A: Since freshman year, I have been involved with my local Amnesty International group and my High school’s Girls Learn International (GLI) club. Through my work with Amnesty International, GLI, and through facts I have heard about forced child marriages and girls being trafficked, I understood deeply how the two vile practices directly violate girls’ rights.

However, most individuals cannot relate to these issues. I strongly believe that almost every social injustice or global issue disproportionately hurts women and girls. Being an action oriented activist, I started an Amnesty International chapter at my high school and also led the GLI chapter at my school.

I undertook this Gold Award project to address these global vile practices one step at a time.

Q: What kind of impact has resulted from your project, and how will it be sustainable? A: My project focuses on root causes, trends and key identifiers of trafficking, child marriage and gender inequality. Hence, its educational tools will be useful even 15 years later, unless these vile practices are entirely eradicated by then.

My project is a framework for education and empowerment and not a one-time event. To sustain Project GREET’s impact after initial film screenings and distribution, I used an automated calendar service to send reminder emails on Women’s Equality Day (August 26), International Day of the Girl (October 11), and International Women’s Day (March 8) until 2033. Project GREET’s partner organizations will also be reminded to screen my film and share the website's educational resources on the aforementioned dates, though they are encouraged to use them more often. Additionally, an email will be automatically sent at the beginning of every month, detailing a women’s rights initiative that historically took place that month, and a supplementary reminder to use parts of my resources to engage and mobilize communities. Since these organizations already have detailed take action plans, this reminder will help them use my project to train different communities on trafficking, child marriage and gender inequality.

All partner organizations have expressed interest in using my curriculum to expand their

outreach. As of late 2017, Amnesty International Burkina Faso and Brazil chapters have decided to add a vocational training program for trafficked girls, and Girls Learn International is happy to add Project GREET resources to its chapters’ curriculum for U.S. high school students to use as an advocacy tool.

Additionally, the Catholic Network to End Human Trafficking will host a vocational training fair for potential trafficking victims in mid-2018. The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) is considering creating a vocational training to protect against trafficking (for both boys and girls). They are using my curriculum to plan their program. All the United Nations delegates have agreed to further expand the outreach of my project and reuse it with an objective to stop these horrid practices.

My website and curriculum continue to be used to increase awareness, garner support from better-equipped communities, connect individuals to activist Non-governmental Organization or NGOs, and empower previously trafficked girls and girls at risk to leave the vicious cycle of dependency on their trafficker.

Q: What have you learned from completing your project, and how has your Gold Award prepared you for the future? A: I have gained more confidence to be a risk-taker, a trait that will help me in my future to form connections, thereby complementing my current skills.

When I interviewed experts from across the globe on the topics of child marriage, trafficking, gender equality, governance and film-making, I learned that a leader continually learns and reflects.

Previously, I had never delegated so many tasks, let alone to many adults. I had primarily communicated with peers in past leadership roles. So, through this project, I’ve significantly improved my leadership and team building skills.

During this project, I also built relationships with individuals from different religions, ethnicities, cultures and communities around the world. This has inspired me to choose a job in the future with an international aspect that will immerse me in different cultures.

I also learned new technical skills like website building, movie making, and video editing, improved research skills and became an expert on trafficking, child marriage and gender inequity. Through the extensive use of Excel and email archiving methods to stay organized, and PowerPoint presentations to pitch my project to team members, I was able to manage a large number of people, and thus vastly bettered my record-keeping and organization skills. These skills have given me a new outlook.

As a future leader, I hope to become more compassionate and gain greater perspective from others to tackle pressing global issues such as climate change, lacking representation of women and minorities, war and poverty, unscrupulous business practices, and social evils beyond trafficking and child marriage.

Q: What have you learned from being a Girl Scout? A: Girl Scouts has given me the confidence to learn, lead, and serve, and the courage to take physical and operational risks.

#girl scouts#gsusa#gold award#goldengirls#feminism#GREET#human trafficking#gender inequity#child marriage#United Nations#UN#Girls Learn International#International Women's Day#women's rights#rehabilitation#tw// trafficking#tw// child mariage#tw// violence against women#amnesty international

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Jobs for Coordinator & Transport Coordinator In Karachi Latest Jobs 2022

Jobs for Coordinator & Transport Coordinator In Karachi Latest Jobs 2022

Jobs for Coordinator & Transport Coordinator In Karachi Latest Jobs 2022 Date Posted: 07 February, 2022 Category / Sector: Classifieds Newspaper: Dawn Jobs Education: Bachelor Vacancy Location: Karachi, Sindh, Pakistan Organization: Health Oriented Preventive Education HOPE NGO Job Industry: NGO Jobs Job Type: Temporary Expected Last Date: 28 February, 2022 or as per paper ad Health…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

CELEBRATIONS OF EID-E-MILAD UN NABI AT HOPE

Streets across Pakistan turned festive as the faithful celebrated Eid-e-MiladunNabi, the birth anniversary of Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) with religious zeal and fervor.

The 12th Rabi-ul-Awal marks the birth of the Holy Prophet Hazrat Muhammad (Peace be upon him).

Government buildings, streets, houses, shopping malls, and mosques were decorated beautifully with lights and buntings, as the youth and children did fireworks and marched in rallies wearing colorful dresses. Religious festivities are the part of Pakistani society; it promotes religious and cultural values.

'Milad' or recitation of poems to celebrate the praises of the Holy Prophet are held i by Muslims during the month of Rabiulawal, the third month of the Muslim calendar.Also commonly known as 'Milad un Nabi', this day is observed as a public holiday in many countries with a large Muslim population as it commemorates the anniversary of the birth of the founder of Islam and the proclaimer of the Quran.

Despite the standard operating procedures (SOPs) issued by the government for Eid-e-MiladunNabicelebrations, adherence to social distancing and mask-wearing instructions was almost non-existent.

Each yearEid-e-MiladunNabi is celebrated in the schools and hospitals of HOPE – An Educational NGOin Pakistan, to bring religious unity among the students and staff members. It also gives a chance to the students to show their talent. Competitions are held in all the schools and prizes are distributed.

The events were held at HOPE Head Office, HOPE General Hospital, Zia Hospital and School, Thatta Hospital and School.

HOPE- An NGO in Pakistan does its best to encourage the hidden talent in these underprivileged children as well as inducing the religious spirit in them. Milad was the perfect occasion to let these students show their respect for the beloved Prophet (P.B.U.H.) through recitation of various Naats, Famous Naatkhuwans were also invited to recite Naats in their beautiful voice to increase the feeling of devotion. The way they presented the Naats fascinated the audience.

Under the leadership of Dr. Mubina Agboatwalla - A Child Specialist in Karachi, the event ended filling the hearts with joy and mind with inner peace, of all those who were present there. Everyone was served with delicious snacks, sweets and cold drinks.

0 notes

Photo

‘A ghost that haunts’: Living with landmines in Kashmir | Human Rights News

One night in December 2000, Mohammad Yaqoob says he was selected by the Indian army for patrol duty along the Line of Control (LoC), the border dividing the Indian and Pakistani-administered regions of Kashmir.

Twenty years ago it was standard but informal practice in parts of Indian-administered Kashmir for the army to select young men from nearby villages for night patrol along the 734km LoC, to keep watch for “infiltrators” from the other side of the border. For this, Yaqoob says he and other men from his village did not receive any training, pay or compensation.

As he returned home just before dawn, the 30-year-old stepped on a hidden landmine and, in an instant, lost his leg.

Fellow villagers who were also part of the patrol that night took him to the nearest army hospital in Tangdar, Kupwara. While medicine was provided by the army free of cost, Yaqoob had to pay for the surgery he needed.

When Al Jazeera contacted the Divisional Commissioner of the Indian Government to clarify what the official policy is towards using villagers for patrols and the treatment of landmine victims in Kashmir, we were asked to submit our questions, which we did via email. These remain unanswered several weeks later.

A telephone call and email with questions to the Chief Secretary of Jammu and Kashmir, the Administrative Head of the State Secretariat, also went unanswered.

The spokesman for the Indian Ministry of Defence, Rajesh Kalia, referred us to the Indian army for comment. The spokesman for the Indian army, Aman Anand, also asked us to email questions, but these, too, were not answered despite numerous follow-up emails and text messages.

Former Director-General of India’s Defence Intelligence Agency Kamal Dawar did talk to us. He said: “These are localised practices and not official. The station army officer may take villagers to guide them through their area, for patrolling purposes. I am not sure if they pay them or not.” He further stated that India does not lay landmines during peace time but only when there is “a threat from an enemy state or possibility of an imminent war.”

‘My wife divorced me’

For Yaqoob, that night changed the course of his life. A member of the Pahari tribe, he lives in the village of Prada in the Kashmir district of Kupwara, just 4km from the LoC.

Sitting in his house, Yaqoob explains that he used to work as a labourer and, during summers would take his cattle to graze up in the mountains. After losing his leg, however, he cannot go to the mountains or take on any labour work. For the past two decades, this has left him with no income apart from a small pension.

After a landmine injury, victims must file a First Informer’s Report (FIR) in order to qualify for a 1,000-rupee ($13.60) monthly pension paid by the Indian Social Welfare Department to landmine survivors.

“While I was in the hospital after surgery, my brother went to file the FIR,” says Yaqoob. “He found out that the Army had already filed an FIR in our name, in which they had stated that I was in the forest collecting timber when I had stepped on a landmine. It was shocking for all of us.”

Mohammad Yaqoob lost his leg to a landmine in 2000 and receives $13 a month in compensation

He still received the pension but soon after his injury, he says, his wife divorced him and moved back to her parents’ house, leaving him to raise his two daughters, then aged four and six, alone. Yaqoob had to move in with his brother.

Today, his daughters are studying at the University of Kashmir in Srinagar. Relatives and neighbours help Yaqoob cover their tuition and living costs. He says he has faith in his daughters and hopes they will build successful lives through their education.

Division lines

The LoC is a de facto border which divides Kashmir into India-Administered Kashmir and Pakistan-Administered Kashmir. It is one of the most dangerous and militarised borders in the world and is heavily guarded on both sides by the Indian and Pakistani armies.

The Indian Army first planted landmines along the LoC during the 1965 India-Pakistan war, then again during the 1971 Indo Pak war, the 1999 Kargil war and, again, in 2001 under Operation Parakram, a military standoff between India and Pakistan in Kashmir. Like India, Pakistan has not signed up to the Mine Ban Treaty.

According to the Landmine Monitor Report 2004, the last confirmed large-scale use of anti-personnel landmines by Pakistan took place between December 2001 and mid-2002 along the LoC.

‘Preventing militants’

In April 2008, Brigadier SM Mahajan, Director of Military Affairs at the Ministry of External Affairs in India, stated that the main reason for laying landmines was to prevent the “infiltration of Kashmiri militants across the Line of Control”.

But on the Indian side of the LoC, there have been few reports of rebels being killed by landmines over the years. Most of the victims are civilians or members of the Indian army.

According to the research group, the Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor, the total number of casualties among civilians and the Indian army is not officially recorded. But the group gathers the figures it can from a patchwork of anecdotal reports and media accounts. Between 1999 and 2015, the Monitor identified 3,191 victims of activated mines or improvised explosive devices (IEDs) and explosive remnants of war (ERW) in India. Of these, 1,083 were killed and 2,107 were injured, with the fate of one victim unknown.

An Indian border security force soldier searches for landmines with a metal detector during a patrol at the India-Pakistan border in RS Pora, southwest of Jammu, in October 2016

Yeshua Moser-Puangsuwan, a research coordinator with the Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor, says: “There is no known press report of an insurgent being killed by a landmine since we started the Landmine Monitor in 1999.

“Before 2011, the Indian Army maintained a website which regularly reported on deaths of insurgents in encounters, but none in minefields. In only one case, in a media report on July 29, 2020 in Nowshera, some militants were reportedly shot while trying to cross. Subsequently they “heard a blast”, and assumed it must have been a landmine triggered by a fleeing militant.”

A perfect storm

The Ottawa Convention – also known as the Mine Ban Treaty – of March 1, 1997, has been signed by 164 countries. This treaty prohibits signatory states from use, stockpiling, production or transfer of anti-personnel landmines (APLs). India has yet to sign it. The official stance of the government has been that the country has “volatile borders”, and if and when a non-lethal alternative to APLs is introduced, the country will ban the mines.

The International Campaign to Ban Landmines is a global network of non-government organisations (NGOs) which is active in about 100 countries. It claims that the largest stockpiles of landmines are held by Russia, Pakistan, India, China and the United States.

Apart from killing and maiming people, landmines impede people’s freedom to go about their normal lives. They affect the local economy by rendering land useless for cultivation.

Khurram Parvez, a leading human rights activist and programme coordinator for Jammu and Kashmir Coalition of Civil Societies (JKCCS), says: “Once landmines are planted in fields, for people the need to stay alive becomes much greater than the need to cultivate crops or collect fodder for cattle. Not cultivating crops means a decrease in food production and landmines kill domesticated animals.”

Moser-Puangsuwan, adds: “Generally, the impact is measured in how much land becomes inaccessible due to the presence of mines. There is no publicly available information on this in India.”

A Gujjar woman with her livestock close to the Line of Control border between Indian- and Pakistan-controlled Kashmir, an area which has been blighted by landmines

The agricultural and pastoral communities living alongside the LoC are mostly from the Gujjar and Pahari tribes (Yaqoob is Pahari). These people have found themselves caught in a perfect storm. On the one hand, they are economically one of the most marginalised groups in Jammu and Kashmir because they are so remote from central government areas. On the other, living near the LoC comes with the perpetual fear of a landmine blast or a mortar shell hitting them. Most of these villages are less than 2km away from the LoC.

‘Landmines were planted in our fields’

Iftikhar Shah, 27, an independent researcher working in Srinagar, who also lives in the village of Prada, says: “In late 1990s, landmines were planted in our fields. Our region is mountainous and, because of this, we are able to cultivate only a few crops like maize. With landmines in our fields now, it has been rendered completely useless. We did not even get compensation for it.”

“The Indian army provides compensation for land where bunkers and camps are built, but not for the land where landmines are planted,” explains Parvez, who himself lost a leg to a landmine.

In 2013, it was reported that landmines had been laid across approximately 3,512 acres of land in several villages in 1999.

However, when we asked about this, the sub-district Magistrate of Tangdhar Block, Kupwara, Bilal Mohiuddin, said: “I have no knowledge about any landmines in the region, neither have we received any cases of injuries or casualties.”

Parvez, however, says he believes “the civil administration and local police are not informed about the landmine plantation. For the army, they don’t want to leak out the information as there is a possibility that non-state actors might pick this vital information up”.

‘A fast track to poverty’

Adding to the plight of the villagers in the area is the fact that up until 2005, minefields were neither marked with warnings nor fenced off.

“In 2002, a man from Warsun, Lolab (Kupwara) lost both his legs in a landmine blast in a non-LoC area,” says Parvez. “Later, Jammu and Kashmir Coalition of Civil Societies advocated for the installation of danger signboards in Urdu and the fencing-off of areas with landmines. It was implemented to some extent. The army fenced the camps with mine plantations but they didn’t do so in areas along LoC.

“In my opinion, for the army, the objective of planting mines along the LoC is to stop incursions and if they start fencing the areas with mines off, then their objective is defeated.”

A sign warns of landmines near the Line of Control between Pakistan- and Indian-administered Kashmir

Moser-Puangsuwan says: “For the family in which a landmine casualty occurs, it is devastating. It is a fast track to poverty. This also has an impact on their community. The productivity of landmine survivors diminishes greatly, usually completely in regards to their former occupation.”

He adds: “We have no idea how well-marked the areas affected by landmines are. These areas are not accessible to international human rights groups to determine that. We have no reports from people living in the areas adjacent to the LoC how comprehensive and clear the marking is. India is a state party to the Amended Protocol II of the Convention on Conventional Weapons. Article 4 of that convention requires ‘measures are taken to protect civilians from their effects, for example, the posting of warning signs, the posting of sentries, the issue of warnings or the provision of fences’.”

In this hilly terrain, however, landmines can slide down from their original position during rain or snowfall. So, even if there is a warning sign, it may be in the wrong place.

Signs used to be in Hindi, but this was changed to Urdu after advocacy efforts from the International Campaign to Ban Landmines and Jammu and Kashmir Coalition of Civil Societies. “People in Kashmir cannot read and write Hindi,” Parvez explains.

A heavy price

In 2010, a court in Kupwara district directed the government of India to pay 1.2 million rupees ($26,200) to Gulzar Mir, a double amputee who lost his legs to an anti-personnel mine in 2002 while grazing livestock in the village of Warsun. Such action, however, is rare and victims often struggle to apply for compensation, according to Moser-Puangsuwan.

Victims often have to wait up to six months until they start receiving the 1,000 rupees (just under $13.50) per month pension from the state Social Welfare Department, and the sum is too small to cover their living costs.

Getting medical treatment for injuries can also be onerous as the road infrastructure connecting villages and towns is poor. For some people, it can take half a day to reach the nearest medical facility. According to the victims, medical expenses in the aftermath of a landmine blast can be as high as 200,000 rupees ($2,700), which for agricultural workers who earn as little as 225 rupees per day ($3) is a very heavy price.

It is not unusual for an injured person to be carried from house to house so that every villager can contribute to the cost of getting them to a hospital.

‘There is always a fear’

About 30km from the main town of Uri, in the Baramulla district of Kashmir, lies Churranda – one of the most remote villages on Indian territory before the LoC.

The well-worn roads leading to this village of 226 households are inaccessible in the winter months due to heavy snowfall. Set against a backdrop of mountains veiled by a white sheet of snow and snow-capped pine trees, the concertina wires enclosing the village disturb its natural beauty.

It is hard for the residents of the villages in this area to tell their stories to the wider world. People from other parts of Kashmir and the rest of India are not permitted to enter, nor are journalists without prior permission from both the local authority and the army. For this report, we were required to present our IDs to army personnel stationed in the area. We went on two occasions – on the first we were allowed in; on the second we weren’t.

The gate at the entrance to Churranda village, where all visitors must show permission documents and be frisked by the army before they can go inside. Visitors are not allowed to take cameras or mobile phones into the village

A small army blockhouse is situated just outside the gate to Churranda. Here, the army frisks the men, check their bags and examines their permission documents if they are not locals. Women are led to a small concrete booth, inside which a local woman in army uniform frisks them and checks their belongings.

Visitors are not allowed to carry cameras or mobile phones inside the village.

The residents of Churranda recall the nights during the 1990s when they would be taken by army personnel down towards the deep mountain ravine along the LoC to help plant the landmines, cutting back crops and clearing land in the darkness to do so. But now it is impossible to pinpoint the exact location of the mines.

Pointing towards a patch of land down the hill, Mohammad narrates his story with sadness: “We – I and a few of my friends – were taken there to cut the crops for them to plant mines on. It was a very difficult time for us, but we were helpless. We don’t have any choice but to cooperate with them for our own survival.”

In August 2017, Hakam Bi, now 21, was collecting fodder for her family’s cattle along with other women from her village. Walking up the hill, she stepped on a landmine. When she came round, she found herself in a local taxi with blood all over her body. She was taken to a hospital more than 100km away in the summer capital, Srinagar city. Her right leg had to be amputated.

Bi explains that she was living with her mother and three sisters at the time and that the family lived off the income of the oldest sister’s husband. In 2015, her marriage to Mohd Sadiq, who lived in the same village, had been agreed. They married in 2018, but in many similar cases, marriages fall through as individuals with disabilities can be considered a burden to a family.

We enter Bi’s house to find her blowing into a wood-fire stove, preparing morning tea for her mother-in-law and husband, while her mother-in-law stitches a quilt. Seeing us enter, a group of young men and children gather around the house, wanting to know what is going on. Feeling uncomfortable speaking in front of the village boys, Bi takes us to the side of her house to tell us her story.

Mohammad Yaqoob, who lost his leg – and ability to work – to a landmine in 2000, was left to provide for his two small children

With tears in her eyes, she explains: “I belong to a poor family, I don’t even remember my father’s face – I lost him when I was a child because of a medical condition. At my mother’s home, I didn’t have enough clothes to wear and I couldn’t demand them from my brother-in-law. Never had I thought that my life could get even worse. Now I am even scared to have children in future. How will I take care of them? How will I do my routine tasks?”

To compound all this worry, her husband must risk his life on a daily basis to provide for his family. He works as a porter for the army in the area were landmines are planted. “There is always a fear of losing a leg or even my life, but I have no other option,” says Sadiq, 21. “I cannot migrate to the town like many have done here as I don’t have enough resources to cover the cost of living in Srinagar city.”

As government employment schemes do not reach as far as these border villages, many are dependent on the army for work as porters, labourers, cooks and watchmen, and must accept the risks that come with that.

The army pays porters a monthly salary of 15,000 to 18,000 rupees ($205 to $246). These workers are also responsible for maintaining the LoC fence, along which most of the landmines are planted. Any landmine victim is regarded as a “casualty within service” and receives a one-off compensation payment of, usually, approximately 22,000 to 23,000 rupees (around $300). But local men, such as Yaqoob, who are just casually selected to accompany patrols, do not qualify for this payment.

Each unit of the army remains in the area for two years and is then replaced by a new one. Injured porters have a degree of job security with the units with which they were working, and these units will often write a recommendation letter to the next unit. But this is not guaranteed and, in 2016, according to locals, the new unit did not employ any of the injured porters.

‘The most important thing is that he cares about me’

In Kamalkote, another border village in Uri, Mohamed Ameen, 20, lost his leg in 2016 while working at the Khamoshi border post as an army porter. He was taken by army vehicle to Srinagar for treatment. The family stayed there for six months and incurred a total cost of 4 lakh ($5,400). The army provided 23,000 rupees ($310) towards his treatment. Ameen now survives by sharing his retired father’s pension and the 1,000 rupees a month he receives from the state.

Ameen sits with his father and younger brother in his home. His face reflects the trauma he has endured when he explains how no one wants him to marry their daughters due to his disability.

In this regard, Muneer Hussain, 55, who lost his leg when he was working as a porter in 1999, is one of the “lucky” ones. He got married a few years after his accident. His wife, who is 46 but did not give her name, says: “The most important thing is that he cares about me and our three children. I am more than happy to support him in these times of crisis. It is not a bad life, we have been surviving like this for years now and will definitely thrive in future.”

Hussain received 22,000 rupees from the army but had to pay the remainder of the treatment cost himself – about two lakh ($2,700).

In many families, it is the sole breadwinner that has been injured. Since income drops off after such an incident, parents are often unable to pay for their children’s education, and a vicious cycle of poverty ensues.

Soni Begum, 45, lost a leg when she stepped on a landmine in 1998. Three years later, her husband also lost a leg while working as an army porter

In some cases, more than one member of the family has fallen victim to landmines. In 1998, Soni Begum, 45, who lives in the village of Jabra in Uri, lost her leg after she stepped on a landmine while taking her livestock to grazing land.

“Back then, Jabra was not connected by roads. I was carried by neighbours on their shoulders to reach the nearest health facility, 30km away,” she recalls.

From the balcony of her small house, overlooking the hills of Churranda, she points out one of the hills where her family’s fields are located.

“Three years later, my husband, who worked as an army porter, was building a bunker at the Nanak Post. He unknowingly stepped on a landmine and lost his leg,” says Begum. “Two kanals (a quarter of an acre) of our land are under the control of the army. This land is enclosed within the wires and we are not allowed to access it.” She says the family has not been compensated for this.

‘The last village’

Karnah, in Kupwara, is located in the northern area of the Kashmir valley and is 90km from Srinagar. To reach it, travellers must cross the Sadhana Pass, which is more than 11,000 feet above sea level and divides the Karnah block from other parts of Kupwara and the rest of the valley.

During winter, the pass is covered in 20 feet of snow, effectively cutting off the “capital” village of Tangdhar.

The road to Seemari, the last village in Indian-administered Kashmir, close to the Line of Control. On the other side of this valley is Pakistan-administered Kashmir

The Hindu Kush mountain range stands tall and, approaching the LoC, one can feel a rise in temperature. The maize fields here lie barren but the Kinnow fruit, a type of orange, is plentiful and adorns trees in the front gardens of local houses, ripened by the warmer climate.

Across the river Kishenganga (or Neelum in Pakistan) lie the villages of Pakistan-administered Kashmir. A suspension bridge on the river in Teetwal connects the two sides.

Seemari is the last village in Indian-administered Kashmir. The borders, as marked out by the bridge and the river, along with the presence of the Indian army highlights the controlled nature of people’s lives here.

Waving to a man across the river, standing on the Pakistan-administered side, our local guide tells us: “That could be my relative or my neighbour’s relative. It is such a strange thing that we have been separated from our family.”

Haider Mughal, 70, lives in Seemari. Sitting beside the front door, while his wife prepares dinner, he greets us. The sun has gone down and a lantern lights up the small kitchen. He tells us that he lost his right leg due to a landmine in 1997.

Haider Mughal lost his right leg in 1997 when he stepped on a landmine while grazing livestock on his family’s land. Landmines had been planted there without the family’s knowledge

Just as on any other day, Mughal had gone up to his share of the common grazing land to feed his livestock, when he stepped on a landmine which was hidden under the ground. “This land belongs to my family. I have the papers as well – we used to pay our share of tax to the state revenue department. We have absolutely no idea when the army planted these landmines,” he says.

Mughal has two daughters and a son. Back in 1997, he had to sell all of his livestock, which was his family’s primary source of income, to raise the funds for his operation. He now has an artificial limb which needs to be replaced every year due to wear and tear caused by the rough terrain on which he must walk.

One artificial limb costs about 10,000 rupees ($135). With the support of the army, a Jaipur-based organisation provides the initial artificial limbs – known as “Jaipur feet” – to victims. However, future expenses, such as the cost of replacement limbs, must be met by the victims themselves.

‘Plastic legs don’t work’

Amroohi village is surrounded by a fence guarded by the army. At the gate, everyone must undergo frisking and ID checks before entering and may only enter or exit at certain times of the day.

Niyaz Mohammad, 75, endures the process every day as he returns from Tangdhar. A few metres from the gate, just out of sight of the soldiers posted there, Mohammad shares his story.

He was 25 when he went out to his fields to graze cattle and stepped on a landmine. He lost his right arm. “In 1971, when landmines were planted, there were no signboards,” he says. “I was walking when I suddenly stepped on a landmine. Family members and neighbours took me to Srinagar. We had to bear all expenses on our own.”

Shakeela Begum, 60, lost her left leg to a landmine that had been planted in her back yard, while she was gathering vegetables from her garden

In 1994, Shakeela Begum, 60, a resident of Amroohi whose husband is a retired policeman, was walking towards the back yard of her house where her family had planted vegetables when she stepped on a mine and lost her left leg.

“One day before this incident, the army, during their regular night patrolling had installed mines in my back yard without informing us,” says Begum. “Due to this injury, I have been suffering multitudes of joint and backbone issues.”

At the time, she was a young mother to two daughters and a son. She has since had two more sons.

Sitting beside her, her older brother, Bashir Ahmed, adds: “We took her to the army hospital in Tangdhar. We were charged 24,000 rupees for the operation and had to pay all the costs on our own.” The family took their case to the District Magistrate in Kupwara but has never received any compensation.

Gulab Jan, 35, is sitting on the front veranda of her house in Amroohi. She says she stepped on a landmine and lost her right foot while working in her field in 1995. She says she received no compensation at all for the cost of her treatment and now survives on the 1,000-rupee monthly pension from the Social Welfare Department.

The army did take her to its artificial limb centre in Pune city and provided her with a prosthetic leg. “The plastic prosthetic legs don’t work in hilly areas,” she says. “We have to walk on the rough terrain and those legs break easily. A local cobbler has made this artificial leather shoe for me and I get it repaired when needed.”

Gulab Jan stepped on a landmine in 1995 while working in her field, and lost her foot. She says the plastic prosthetic leg she has been given is useless on the mountainous paths where she lives

The haunting

In 2016, the International Campaign to Ban Landmines urged the Indian state to cease all mine-laying activities and to join the 1997 Mine Ban Treaty.

However, India is reported to be planning to lay more mines. “It is extremely disappointing that the world’s largest democracy is reportedly contemplating the use of landmines again,” says Megan Burke, director of the International Campaign to Ban Landmines.

In October 2017, India reiterated that the Amended Protocol II of the Convention on Conventional Weapons (CCW) “enshrines the approach of taking into account legitimate defence requirements of states with long borders”.

The statement also mentions that India believes that new military alternative technologies that can perform the defensive role of anti-personnel landmines will enable it to stop using landmines altogether. In this statement, India also said that it had ceased the production of “non-detectable” landmines and had started increasing public awareness to minimise the humanitarian cost.

Landmine clearance is a time-consuming and dangerous task. In 2005, it was reported that 1,776 Indian soldiers had died while laying and removing mines since 2001.

And for the people living along the LoC, Parvez says, landmines are like a “ghost that haunts even after the war is over”.

Read full article: https://expatimes.com/?p=17347&feed_id=30835

0 notes

Link

National Minorities Day was observed in Pakistan yesterday. At least once a year, the Pakistani authorities try their best to project to the world that they care for the religious minorities of the country. Functions are organized to, as Radio Pakistan said, “honor the services, the sacrifices and recognize the contribution of minorities in creation of Pakistan and nation-building.”

Some like Minister for Information and Broadcasting Shibli Faraz tweet that “the dream of the state of Medina will not be realized without welfare of the minorities” and how the government under the leadership of Prime Minister Imran Khan has been endeavoring to materialize this dream.

Pakistan President Arif Alvi even cut a cake at the President House in Islamabad, reiterating Pakistan’s commitment to refrain from discriminating against minorities and to maintain an atmosphere of tolerance and brotherhood within the country.