#HERNÁN DÍAZ

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

https://kenyonreview.org/kr-online-issue/2018-janfeb/selections/hernan-diaz-342846/

Martha Malini’s death from respiratory failure was mentioned in several newspapers around the world. Her unique appearance—white hair down to the waist, ivory saris and suits, downcast eyes that seemed to regret the attention the rest of her body drew to itself—ensured that even the briefest reports came with a large picture. She could be seen giving talks, opening exhibitions, and launching books in every continent. Some of the pictures also featured Francis Towne, her late husband, who was the subject of the talks, the topic of the exhibitions, and the author of the books.

Having suffered from a slow but relentless form of sclerosis from his youth, Towne required constant care by his early fifties. Malini, thirty years his junior, became his assistant shortly after taking one of his classes at Columbia University. By the end of the semester, she was pushing his wheelchair around campus and along the river during long promenades. Soon they were living together. Despite his illness, Towne traveled often and wide to accept awards, receive honorary doctorates, and, until he lost his ability to speak, give lectures. Malini always traveled with him. Although they seemed to lead a happy life in the Upper East Side—and even though he received the best medical care available—shortly after his eighty-first birthday, Malini took Towne to a clinic in Montreux, where they got married two months before he died. She was his only heir and managed his literary estate with firmness. Aside from the occasional foreword to a new edition of her husband’s work, she never published anything of her own. And yet, her fame had grown steadily through the years so that when she died, about three decades after Towne, she was a modest international celebrity.

Most of Malini’s obituaries stayed close to these uncontested basic facts, adding words of praise for the zeal with which she had protected and promoted Towne’s work, a task to which she had given almost her entire life. But there were also critics who claimed that she had done great damage to the writer’s legacy by greedily giving every unpublished scribble to the press—juvenilia he abhorred, intimate papers, damning letters, and other documents that quite obviously tarnished his reputation. Other detractors pointed out that the only good thing about the critical editions that she oversaw was the exquisite cloth binding with gilded lettering. And above everything else, all her opponents denounced the effect of Malini’s litigious tendencies. She spent a great deal of time in court, suing anyone who dared use her husband’s name or work without her consent, which resulted in effectively taking Towne out of the literary conversation and mummifying his work—he could not be quoted, parodied, or pillaged in the ways that keep a writer alive and relevant.

Although opinions on these matters were divided—some believed that any addition to Towne’s body of work was a gift, that the critical editions and compilations were important achievements, that the lawsuits protected the sanctity of his writings—they still referred to verifiable facts. But Malini’s most bitter adversaries had objections whose veracity was harder to corroborate. For those who had not been close to Towne, the tales could not be more than hearsay, however eager they were to believe them. Still, it was true that many of the writer’s former close friends had, despite some incongruities, similar stories about Malini. It was said, for instance, that her Hindu halo (her conspicuously austere garments, her references to deities and myths, her palms so often pressed together in front of her chest) was an affectation acquired after moving in with Towne—even if born in India, Martha’s father, an Illinois dentist, had no recollection of his native land, and her mother was of Irish descent. If true, this would only mean that Malini was somewhat frivolous in character—a harmless accusation. Other allegations, however, were far graver. Most former friends claimed to have been cut off from Towne by Malini, who had isolated him completely. Of course, several people from his old circle remained close, but it was said that she had the final word on whom Towne was allowed to see. She only took him out, some alleged, to attend highly publicized events (presumably for large fees), while keeping him away from the intimate dinners and gatherings where more vibrant and meaningful conversation took place. According to other rumors, still harder to validate, Malini abused and terrorized the invalid writer by not speaking to him for days, by neglecting to wash him, and by underfeeding him. Someone claimed to have seen him reduced to a soiled heap in a dark room.

As a Towne scholar, Harry Davis was familiar with these stories and believed he could tell truth from slander. Moreover, he had formed his own opinion after meeting Malini at public events and speaking with her on the phone over a dozen times. He had first called her some six years before her death to ask for her blessing for a compilation he was putting together of Towne’s lesser-known journalistic pieces. She was, he thought, tense and maybe frightened under her white, calm surface. She seldom raised her voice above a whisper and spoke in a hurried staccato that, perhaps, she hoped would pass for assertiveness. In time, he discovered that her conversation was limited to issues that concerned her directly—practical matters, for the most part. Because of her age, some sort of strategy, or simply her vanity (Davis could not tell which), each time they spoke, Malini asked him to start from scratch and remind her who he was and tell her everything about his project. Invariably, this was followed by her legal admonitions. There was something petty about her, and he thought that very pettiness was precisely what made her incapable of the monstrous deeds she was accused of. In his view, a monster could never be so fastidious and insecure. In fact, lawsuits aside, Davis found her quite harmless. Vain, incompetent, and possessive—yes. But to him, there was something touching about these demerits. In short, he did not believe the darker stories told about her and was convinced these myths were misogynistic reactions of the old guard who could not stand to see the work of the great man in the hands of a woman.

Davis’s compilation got mired in endless exchanges with attorneys, agents, and publishers, and it never saw the light. Still, after he had given up, he kept calling Malini a couple of times a year. These awkward conversations had no clear purpose and never led anywhere, but if Davis insisted on them, it was because Martha Malini was the strongest living link to Towne, whose work he revered. It was Towne who had instilled in him the desire to become a writer; it was Towne to whom he had devoted seven years of his youth at a doctoral program; it was Towne’s books he taught his students one semester after the other; it was Towne’s voice he had to suppress in each novel he tried to write. He had barely been born when the great writer died. So, even if he found her somewhat questionable, Davis stayed in touch with Malini. Each time they spoke, after the customary reminders and clarifications (during their last conversations, Davis felt that she pretended to pretend to remember him), she invariably would deliver a long jeremiad. She was so busy and had no life of her own. Not a moment to herself. Every second of her existence was dedicated to Towne. A foreword to a commemorative edition, a speech at the Frankfurt Fair, an exhibition of his manuscripts at the American Academy in Rome, managing the foundation, a tribute at the PEN Festival, the sale of some papers to Princeton, interviews with the press, a reading at the British Library, commissioning new translations into Japanese, meetings with agents. It never ended. And the lawsuits. Always the lawsuits. Copyright infringements, libel, plagiarism. There simply was not enough time. She had not a moment to herself. No life of her own. I have no life of my own, she repeated over and over again.

Eventually, Davis stopped calling. Malini had unleashed her lawyers on two young writers who had published experimental texts based on some of Towne’s stories. One of them refused to pay his fine and was sentenced to prison. That the young author, who was also a performance artist, seemed rather excited about the verdict did not help Davis. Like many others, he felt Malini had gone too far. Besides, Davis’s own writing career had finally taken off, and he lost interest in his academic pursuits in general and in Towne as a scholarly subject in particular. His moderately successful first book freed him from the great author’s overwhelming influence. He lost all contact with Malini. She died three or four years later.

One month after her death, Davis received a call from Malini’s attorneys. He played the message several times, searching for a ciphered meaning in the few recorded words asking him to return the call as soon as possible. Surprise yielded to fear. Could Malini be suing him from beyond the grave? He went through all the articles he had ever written about Towne, searching for unattributed quotations or defamatory passages. A few paraphrased segments worried him. Once he had all his published papers and monographs at hand, he called back. The conversation was too short for anyone to notice the tremor in his voice. They simply asked him to come in at his earliest convenience. It was about an important matter they could not discuss over the phone.

The following morning, Harry Davis was sitting at a conference table together with four lawyers and Michael Chatham, Towne’s literary agent. They read Malini’s will. Most of her assets went to hospitals and libraries in New York and Kolkata. There was only one legatee who was an individual, and his name came up at the end. Davis was the sole inheritor of Francis Towne’s literary estate.

He decided to keep the news to himself until he could make sense of it. Malini had not left a letter or any kind of explanation, and he needed a narrative. The world had changed from one moment to the next, without any transition. It was like with magic tricks, where the process is concealed from the spectator, who is presented only with a result. Or like pure chance—an effect without a visible cause. Yes, it was as if his name had been entered into a raffle. Absurd as it was, this made more sense than any other explanation. Why would Malini bequeath him the estate? She would never have recognized his face in a crowd. She barely knew his name—just enough to feign that she had forgotten it. Had she secretly been following his career and reading his writings about Towne? Had she been testing him all those years? Perhaps she had read Davis’s novel and deemed him Towne’s rightful heir. Davis did not care about Malini’s literary judgment, but this mere possibility flattered him. Maybe she was lonely—completely lonely. Maybe Towne’s circle, her only society since her early twenties, had shunned her. Maybe Davis’s calls had been her only social interactions outside her professional duties. This seemed even more ridiculous than the secret lottery. She was disliked, no doubt, but she must have been surrounded by sycophants and freeloaders. Legions of hypocrites surely had been working on her steadily for years, hoping to be written into her will.

About ten days later, he saw his own name in the papers. Since the lawyers were bound to silence, Michael Chatham must have been responsible for the leak. The multiple calls he received from his office seemed to confirm this. Chatham, who had once turned Davis down as a client with a form letter, now wanted to sign him on as soon as possible—it would make sense to consolidate everything, he said. He also pushed Davis to release a statement at once. Davis wrote a short text expressing his surprise at the honor conferred on him, acknowledging Malini’s tremendous work over the last decades, and promising to do everything within his reach to preserve and promote Towne’s legacy by making it more accessible to everyone.

Immediately after the announcement, Davis was overwhelmed with congratulatory messages and requests for interviews. At first, he tried to send personal responses but soon was using the same template for everyone. He agreed to see a few journalists, as long as there was no video involved, a ban he stopped enforcing after a few days. In all his interviews his main point always was that, as an executor, he wished to disappear behind Towne’s work. He would just be a facilitator. Besides, he had his own career to look after, and he wanted his own pursuits as an author to remain apart from his tasks regarding the estate. But he discovered it was impossible to keep these spheres separate. Davis’s book sales soared once his name became associated with Towne’s. The first edition had been released by an independent press, but Chatham made a new deal with Towne’s publisher: they would reissue Davis’s first novel and sign him for two new books. Davis knew this sudden success was because of Towne—but he also felt he deserved it.

With the new contract came promotional obligations. For a while, Davis was all over the media. Despite his best efforts, every feature or interview at some point veered toward Towne and the estate. His name always came with the same apposition—he had become “Harry Davis, Francis Towne’s literary executor.” After a few weeks, he realized that he would spend more time promoting Towne’s work than his own. Malini had scheduled numerous commitments months and even years before her death, many of which Davis now had to honor. The Guadalajara Book Fair, the ZEE Jaipur and the Hay festivals, UNESCO, and the Berlin State Library resulted in a leave of absence from his university position. Between trips, he had to deal with a constant stream of requests. Someone wanted to put together a compilation (very much like the one he had planned years ago); someone was thinking of adapting one of Towne’s novels for the screen; someone planned to reissue his radio interviews. And then, of course, the lawyers. Davis was far from litigious and intended to manage the legal aspect of the estate in a more open way, but almost every day he was presented with documents that required his consideration, his signature, and, sometimes, his presence in court.

When he received the inheritance, Davis had just started work on his second book. Now, a few months later, he found it impossible to regain the lost momentum. The plot, the tone, and the structure were clear in his mind, and yet he was unable to write a convincing page. To make more time for himself, he hired a personal assistant. Although at first it embarrassed him to have one, his assistant soon became a crucial presence in his life. Still, regardless of how much work he delegated, there were too many social appointments and issues that demanded his personal attention. And whenever he found a spare moment and managed to overcome his exhaustion, everything he wrote seemed lifeless.

Little changed over the next three years or so. He honored all the commitments inherited from Malini, but these engagements led to new ones—more book fairs, universities, literary festivals, and libraries. The foundation alone was almost a full-time job. Sometimes he was invited to read some of his own texts or give a workshop, but after a while, he started to turn down these events. It was embarrassing to be able to read only from his first book, written too long ago, and to give writing advice he was unable to follow. He did, however, give several talks and keynote addresses on Towne’s work. Because of his constant travels, he finally had to give up his teaching position, so he welcomed every chance to lecture and even started to pursue these opportunities, although they were all related to Towne.

Five or seven years ago, Davis moved to the country—someplace near Hudson. They say he finds the New York literary scene oppressive. Every six months, he has lunch with his editor. At first, they used to discuss Davis’s novel in progress and had passionate conversations about the books that would follow it. In time, however, their meals started to revolve around literary gossip, TV miniseries, and frequent flyer programs. Davis stopped asking for extensions—it was understood that he had been granted an open-ended one. Both his editor and his agent still believe country life will help his work. Since he moved Upstate, Davis has become a very private man. Except for his public appearances connected to the master’s legacy and the occasional interview (where he avoids talking about himself), he is barely seen. His compilation of Towne’s early journalistic pieces is due out any day now.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Fortuna: la mano que mueve los números

Díaz, H. [T. Calvo, J.](2023), Fortuna, Anagrama, Barcelona. Fortuna es la novela ganadora del Premio Pulitzer 2023 y es asombrosa en diferentes niveles. Primero, es un texto escrito en inglés por un hombre nacido en Buenos Aries, Argentina en 1973; es una obra cuyo tema de telón de fondo es el ambiente financiero y fue escrito por un académico dedicado a las letras y con estudios de filosofía.…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Lectura: 'Fortuna', de Hernán Díaz

Hernán Díaz Crítica de ‘Fortuna’, de Hernán Díaz: el dinero como ficción Tras la excelente ‘A lo lejos’, el autor norteamericano de origen argentino se adentra en una impresionante reflexión sobre la naturaleza económica de la literatura Origen: Crítica de ‘Fortuna’, de Hernán Díaz: el dinero como ficción | El Periódico de España Textos Los templos dedicados a la riqueza –con sus liturgias,…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Hernán Díaz: El inventor del realismo capitalista es argentino y escribe en inglés

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

#conquistadors#craig mullins#aztec empire#spanish empire#conquistador#aztec#aztecs#moctezuma#hernán cortés#spain#spanish#mexico#templo mayor#temple#pyramid#mexica#huitzilopochtli#tenochtitlán#age of discovery#age of exploration#european#pedro de alvarado#mesoamerica#age of empires#cuitláhuac#bernal díaz del castillo#new world#americas#gonzalo de sandoval#cristóbal de olid

140 notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes

Text

La historia verdadera de la justicia. Parte 52

Jueves 21 de marzo de 2024 a las 22:00hs de España, 15:00hs de México, 18:00hs de Argentina.

Gracias por compartir.

#libros#chicosanchez#historia#traiciones#justicia#españa#tenochtitlán#méxico#montezuma#endirecto#conquista#hernán cortés#nueva españa#bernal díaz del castillo

0 notes

Text

¿Cómo están?

Les dejamos saber que de los libros que estaban solicitados, logramos incorporar trece de quince:

[Vínculo enlazado](Búsqueda manual en el Drive)

El Aleph de Jorge Luis Borges (#8 > LITERATURA > #1)

Ficciones de Jorge Luis Borges ( " )

Pájaros en la boca de Samanta Schweblin ( " )

Fortuna de Hernán Díaz (#8 > LITERATURA > #5)

Plata quemada de Ricardo Piglia ( " )

Operación Masacre de Rodolfo Walsh ( " )

El juguete rabioso de Roberto Arlt (#8 > LITERATURA > #7)

Rayuela de Julio Cortázar ( " )

Cometierra de Dolores Reyes (#8 > LITERATURA > #9)

Gris de ausencia de Roberto Tito Cossa (#8 > LITERATURA > #12)

Historias para ser contadas de Osvaldo Dragún ( " )

Los peligros de fumar en la cama de Mariana Enríquez (#8 > LITERATURA > #13)

La involución Hispanoamericana. De Provincias de las Españas a Territorios Tributarios: El caso argentino, 1711-2010 de Julio C. González (#9 > HISTORIA > HISTORIA ARGENTINA)

Los libros Qué temprano anochece de Silvia Arazi y Lejos de dónde de Edgardo Cozarinsky aún no los encontramos digitalizados. Sin embargo, seguimos tomando solicitudes (por aquí) y/o recibiendo material (por acá: [email protected]). Si nos comparten algo desde sus Drives y no por correo, avísennos por acá porque por ahí no nos damos cuenta (acabo de descubrir que tenemos un montón de archivos compartidos sin clasificar -Keo.)

Si encuentran algún error en algún enlace, algún archivo, alguna clasificación, también cuéntennos por medio del inbox.

Hasta ahora, ¡contamos con ya casi cien libros, más o menos, en el Drive! Así que anímense a chusmear las carpetas. Para ser claros: todo lo que sea ficción, poesía y noficción novelada lo van a encontrar en la carpeta número ocho, de literatura.

(Hay cosas sobre la clasificación que todavía no están al cien por ciento sentadas, y hay libros que son bastante difíciles de decidir dónde meter, pero creemos que por ahora las cosas son relativamente fáciles de encontrar; igualmente siempre estamos para escuchar sus sugerencias y/o someter a plebiscito –ja– algunos cambios o decisiones.)

Buenas tardes-noches, gente. Estamos a disposición.

#argentina#argieblr#libros argentinos#literatura argentina#jorge luis borges#literatura#julio cortázar#autores argentinos#roberto arlt#rodolfo walsh

167 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Conquest of New Spain

The Conquest of New Spain by Bernal Díaz del Castillo (1492 to c. 1580) is an account written in 1568 of the early Spanish colonization of Mesoamerica, specifically the conquest of the Aztec civilization in Mexico from 1519 to 1521 when Díaz was a member of the conquistador expedition led by Hernán Cortés (1485-1547).

Bernal Díaz

Díaz was born in 1492 in Medina del Campo, Valladolid, in Spain. Like many young men of his generation, he sought his fortune in military escapades in the New World. Díaz was in Nombre de Dios in Panama in 1514 where he served Pedro Arias de Avila (aka Pedrarias Dávila, b. 1442). In 1517, Díaz moved on to Cuba where he served under another infamous colonial governor, Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar (1465-1524). Velázquez was keen to find out more about the Yucatán Peninsula – then considered just another Caribbean island. Cuéllar sent two expeditions of exploration to Mexico: one in 1517 led by Francisco Hernández de Córdoba (1474-1517) and another in 1518 led by Juan de Grijalva (1489-1527). Díaz was on both expeditions as an ensign, and they have a chapter each devoted to them in Díaz's chronicle, but it is inconsistencies in the geography of these expeditions which have led some to doubt Díaz's participation.

Velázquez was so intrigued by the reports of the first two expeditions concerning a large civilization to the west that he determined to send out a third reconnaissance mission, this time to be led by Hernán Cortés. Díaz went on this expedition in 1519, but Cortés was ambitious for much more than information and was intent on conquest and riches.

After the campaign against the Aztecs, Díaz had an official position in Guatemala which included an encomienda license to extract labour from the indigenous community. Díaz visited Spain again but ultimately returned to Guatemala to write his famous work in the last years of his eventful life. The original title in Spanish is Historia verdadera de la conquista de la Nueva España ("The True History of the Conquest of New Spain"). New Spain was the name given to the viceroyalty that the Spanish established in 1535, of which Mexico was a part.

The work was first published in 1568, almost 50 years after the events the book describes. Díaz was 76 at the time, and this may explain some of the inconsistencies that have preoccupied modern historians. The doubts are a little ironic since one of the primary motivations for Díaz to take up his pen was to set the record straight. Díaz did not agree with a recent publication by Francisco López de Gómara (1511 to c. 1566), Herńan Cortés' private chaplain and final confessor. He felt that López's General History of the Indies (Historia General de las Indias), written in collaboration with Gonzalo de Illescas, had not got all the details of the Aztec conquest right and that Cortés had not been represented accurately. Díaz claimed that López had never even been to the Americas while he had been an eyewitness at every major battle. Díaz frequently criticises and corrects these chroniclers in his own work, and he is keen to show that the conquest was a team effort of conquistadors and not just Cortés, who Díaz felt had gained too much credit at the cost of his colleagues. A further motivation for Díaz was that his account, in which he is keen to show his role in the conquest, in some sense justified his encomienda, which at that point risked being abolished by a new set of laws.

Díaz died around 1580, having outlived all his old conquistador companions, but at least, in the words of the English translator J. M. Cohen, having recorded his version of events for posterity by displaying "a graphic memory and a great sense of the dramatic" (7).

Continue reading...

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

En el año 2019 el Museo Naval de Madrid inauguró la exposición «No fueron solos. Las mujeres en la conquista y colonización de América», en un intento más de reivindicar el papel de las mujeres en las expediciones al Nuevo Mundo. Según los datos ofrecidos en la propia muestra, 30 mujeres acompañaron a Colón en su tercer viaje, más de 300 llegaron a Santo Domingo en el primer cuarto del siglo xvi y la población femenina constituyó casi una tercera parte de los pasajeros embarcados con destino a América entre 1560 y 1579. De los 45 327 emigrantes de procedencia conocida (y hay que puntualizar que era bastante fácil y frecuente la emigración clandestina), 10 118 eran mujeres, y, de ellas, el 50 %, andaluzas, el 33 %, castellanas, y el 16 %, extremeñas. Ya fuese acompañando a sus maridos, como buenas esposas y madres cristianas, o escapando de ese rol femenino y de un destino marcado, arrancaron sus raíces del Viejo Continente para replantarlas en un mundo desconocido. En este viaje al continente americano nos vamos a centrar en Hernán Cortés, del que creo que, más allá de sus luces y sus sombras, no se puede dudar de su genialidad. Utilizo este término por las increíbles hazañas militares y políticas que protagonizó este novato. Como leéis, un novato. Cortés no tenía experiencia en batallas ni en expediciones. Lógicamente, se trató de una aventura colectiva en la que participaron personas de toda condición y personajes de todo pelaje, de los que tenemos conocimiento por las cartas del propio Cortés y por los cronistas de América. En esta expedición a México, no me extenderé mucho por ser de sobra conocida la historia de Malinalli, rebautizada como doña Marina por los españoles y apodada despectivamente por los mexicas como Malinche, pero sí daré unas pinceladas para reconocer su papel relevante:

Doña Marina sabía la lengua de Guazacualco, que es la propia de México, y sabía la de Tabasco, como Jerónimo Aguilar sabía la de Yucatán y Tabasco, que es toda una. Entendíanse bien, y el Aguilar lo declaraba en Castilla a Cortés; fue gran principio para nuestra conquista. Y ansí se nos hacían todas las cosas, loado sea Dios, muy prósperamente. He querido declarar esto porque sin doña Marina no podíamos entender la lengua de la Nueva España y México (Benal Díaz del Castillo).

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

PT. 3

1) Falcão da Silva: "He trained his reflexes in the depths of the Amazon, and puts them to work on the pitch."

2) Lagarto Carlos: "He seems to move to a samba rhythm when he makes a challenge on the pitch."

3) Bagre Antonio: "He's involved in an environmental movement to save the endangered Brazilwood tree."

4) Monstro: "When he drinks coffee, he surges with power. Doesn't do his health much good, though."

5) Formiga Clemens: "He likes to pioneer forms of agriculture that are more rainforest friendly."

6) Presa: "He's really interested in developing engine fuel derived from sugar cane."

7) Borboleta Barbosa: "He wants to look beyond the borders of Brazil and study the playing styles of other nations."

8) Coruja Cerezo: "His powerful physique is down to his arduous training carrying bundles of sugar cane."

9) Leonardo Almeida: "Football's in his blood. He's the fourth generation to represent his country."

10) Mack Ronijo: "Strength, talent, determination-this guy's got the lot. He's the perfect player."

11) Gato: "At the carnival, listen out for the distinctive timbre of his home-made tambourine."

12) Javali Ribeiro: "He's always thinking up spectacular outfits to wear to the carnival."

13) Urso Nogueira: "His cool and calculated style doesn't always mesh with passionate Latin football."

14) Cavalo Oliviera: "His big plan is to start an international biofuel bussiness in Brazil."

15) Tigre Mendes: "He gets more and more pumped as the crowd cheer louder and louder!"

16) Grilo Santos: "His family run a traditional Brazilian eaterie, so he's always cooking for his team-mates."

1) Jorge Ortega: "He's known for his aggressive style. His brutal tackles often lead to melees."

2) Teres Tolue: "Proud of his impregnable defence, he directs the team from the back."

3) Julio Acosta: "He has a fondness for yeba maté tea, and he always packs some when he plays away."

4) Gordo Díaz: "From a family of vineyard owners, he's striving to put Argentinian wine on the map."

5) Ramón Martinez: "He really appreciates the colonial architecture of Buenos Aires."

6) Esteban Carlos: "He does altitude training in the Andes, so there's no escaping his tenacious plays."

7) Sergio Pérez: "He has lofty ambitions of reinventing the Argentinian literary scene."

8) Roberto Torres: "The old legend of El Dorado is an enduring passion for him. He dreams of finding it."

9) Pablo Castillo: "The natural beauty of Argentina inspires his art, and he hopes for recognition."

10) Leone Batigo: "His swooping, powerful plays have earned him the nickname El Cóndor."

11) Diego Oro: "This nutty player sets off fireworks in his bathroom at Christmas and new year."

12) Lionel Cruz: "He makes incredible pork sausages. It's like a hobby for him."

13) Mario Saviola: "His pushy parents said to him, "you'd better win, or else!", which causes him much angst."

14) Hernán Tevez: "Despite his young age, he helps the local radio station, covering football matches."

15) Germán Samuel: "Serve him a steak, sprinkled with sea salt and grilled over an open fire, and he's in heaven."

16) Ricardo Agüero: "The windy regions of Patagonia have been his training ground, so he's an all-weather player."

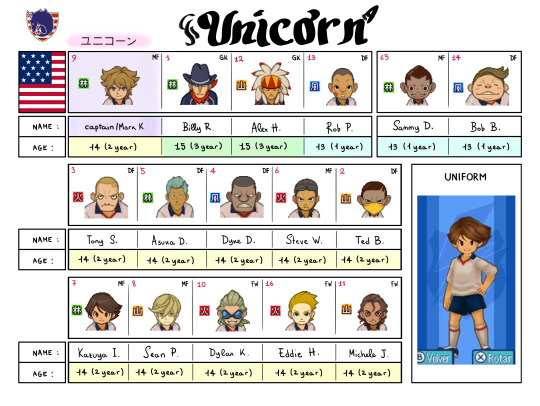

1) Billy Rapid: "He wants to be a cowboy in a western. He's always practising lines in the mirror."

2) Ted Bryan: "He sees Silicon Valley as a goldmine, and he hopes to make his fortune there."

3) Tony Stridas: "This guy is obsessed with eating steaks. He can't rest unless he eats one a day."

4) Dyke Dynamo: "They say that he once wrestled a buffalo to the ground. I'm not so sure, though."

5) Asuka Domon: "Used to live in the USA. Behaves flippantly, but is deep-hearted."

6) Steve Woodmac: "His ambition is to sit in the Oval Office, but no one takes him seriously."

7) Kazuya Ichinose: "This comeback kid is known as the midfield magician."

8) Sean Pierce: "He's only young, but he has a good grasp of Wall Street's complex financial structures."

9) Mark Kruger: "America's star player. He, together with Ichinose, pulls the team along."

10) Dylan Keith: "Top scorer of the FFI qualifier tournament. He is called "Mister Goal"."

11) Michele Jacks: "Despite his age, he is already a genius child actor who has been 10 years in a Hollywood acting career!"

12) Alex Hawk: "He insists that he can read the signs in nature to predict the weather."

13) Rob Parker: "He wants to live the American dream by taking his country all the way to the top."

14) Bob Bobbins: "He's a real slob. He loves to sprawl on the sofa, swilling cola and chomping chips."

15) Sammy Dempsey: "He's tiny for an American, but within him hides the coiled power of a jungle cat."

16) Eddie Howard: "He didn't care much for American football, but he really took to soccer."

____________ _______ ___ _ _ _

(Btw what kind of an introductory line is this, referring to a 14 year old kid, like??

'He was supposed to have died, but...*🙄🥱*'?? But what?? You wanted Kazuya dead? Hater.)

#inazuma eleven#the kingdom#the empire#unicorn#dylan keith#mark kruger#ichinose kazuya#asuka domon#teres tolue#mac robingo

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mila hadn’t smoked in days but still took cigarette breaks, walking in circles around the elm, kicking sun-bleached butts, half-hoping to find something she could salvage among the filters spilling their stringy insides on the gravel. Her walks had the length of a Winston, even when she wasn’t smoking one. She now smelled the tobacco on her sweaters and the lining of her coat – a scent she didn’t perceive when she could afford to smoke a pack a day.

Her mother was still sitting on the sofa, stroking the left armrest while she talked. She barely looked up when Mila walked into the room – a quick side glance, as if she were driving and had to turn back to the road. She kept staring straight ahead as she spoke.

‘We’re going to try to tuck this worry away. It may not work, but believe me: it’ll smudge the distance that separates us from those who are closest to us. Do you really think this is the way I wanted to define it, to corner it? Well then, you’re wrong. Anger, I told you, is what happens when the little pegs no longer go into the little holes.’

The voice followed Mila into the kitchen. It was never a good sign when her mother stopped talking. There was some rice in a container. There was a bag of Green Giant steamed mixed vegetables in the freezer. There were two eggs in the fridge. She thought she would say ‘here is a nice summer salad’ when she put the bowl down on the table in front of her mother.

The voice followed Mila into her mother’s room. She picked up a nightgown and some underwear in the gloom. The smell of night sweats and confinement hovered over the bed. She turned on the light and saw the Post-it notes covering the walls like scattered scales. Her mother had put them up overnight about a week ago, but Mila couldn’t get used to them. Some were cryptic reminders (‘the envelope is under the thing’), but most looked like snippets of her mother’s never-ending monologue (‘the key is what opens, and what works because it opens’; ‘don’t believe too much in what you can understand’). Mila made the bed.

They hadn’t slept through the night in a while. Sleep came to her mother in spurts. After a restless doze, she would start talking again, her voice issuing from the gray dusk of her room, until she got up to walk around the house, and Mila had to get up as well to keep an eye on her. They had run out of her mother’s sleeping pills. Each evening, Mila gave her a double dose of NyQuil followed by a glass of white wine. Sometimes it helped a little. She kept the wine hidden in the garage. Now she poured herself a glass and drank it, leaning on the car. It had enough gas to get to town but probably not enough to return. Once Mila’s check arrived, she would drive out, cash it, fill her mother’s prescriptions, buy groceries and cigarettes, get gas, and drive back.

‘For there is something else that no one so far, I think, has figured out: the victim always has to be without stain. Now, remember what I told you about the stain: the stain shows what’s hidden behind. To tame God in the snare of desire. And let anxiety rest. I apologize for this detour, because it’s not in this direction that we’ll find the last word on the matter.’

Mila had fallen asleep on the sofa. In her dream, a basketball player slammed a drawer shut with a bang and laughed wildly. She woke up, looked around, and understood that the bang had been her mother falling and the laugh, in fact, her cries of pain. Her mother lay on the floor, bawling, blood gushing from her eyebrow. Her mouth looked darker than usual. She had broken a front tooth.

They watched TV. Her mother spoke a little less, since she had to hold the bag of frozen vegetables to her mouth. Her words seeped through the hole in her teeth with a whistle. The cut on her forehead was small, but she had a big bruise. They drank white wine. Every now and then, her mother made long toasts. Some of the speeches made Mila laugh, and each time this happened, she thought she could glimpse a spark of pride in her mother’s eyes – the pride of having made her daughter happy. They clinked their glasses ceremoniously.

The voice followed Mila into the study. When her father lived in the house, the room was called ‘dad’s office’. He used to spend most of the day in there. Shortly after he left, Mila’s mother started calling it ‘the study’. Mila knew her mother had small amounts of cash hidden throughout the house. When she first moved back to take care of her, Mila had found money rolled up in a sock, buried in a flour canister, and tucked into books. There had to be more, and she was sure it would be in the study. She was going to return it to her mother when she got well. Among her father’s things, she found some photos that made her uncomfortable.

‘There is no love except for a name. We all know this from experience. We can only love a name. And when you say the name of the loved one, you find yourself at a threshold. A door. Something that goes from that little other into history.’

Mila’s cell phone got disconnected. Yet another thing that would have to wait for her check to arrive. She didn’t have anyone in particular to call back home – she lived alone, and her few friends were too busy with family and work to be awaiting news from her – but she missed cycling through her usual websites. She hoped it wouldn’t be necessary to call her mother’s psychiatrist. He never had any concrete advice anyway, aside from telling her to create an ‘emotionally safe environment’, and they had enough refills on file. The drugs were always the same, only the dosage increased with each episode. Each time, Mila had left everything and moved in with her mother.

All they had left was some sort of therapeutic shampoo with a tarry reek, which, at first, she thought was the source of the smell. As she rinsed her hair, she noticed that, behind the faint traces of chlorine in the water dripping down her nose, the smell, rather than fading, was growing stronger. She wrapped herself in a towel and rushed out of the bathroom, running through the living room where her mother sat saying ‘just take this belt and open it, give it a half turn, and fasten it again, and you get something on which an ant walking along passes from one of the sides to the other side, without needing to walk across the edge’, and into the kitchen, where, on a lit burner, she found an empty pot, red hot and charred, its plastic handle reduced to a bubbling puddle on the stovetop.

Another walk around the elm. Through the tree top, Mila stared up at the sky, scratched and torn by the bare branches. For the briefest instant, she found it strange that dawn was working in reverse – that it was getting darker with each passing second – but she dismissed it as one of those quirks of nature. Then, of course, she understood that it was dusk’s twilight, not dawn’s. She was surprised and embarrassed at how readily she had accepted, for that fleeting moment, the impossible situation of a blackening sunrise.

She woke up to find her mother pacing around the living room with a notebook in her hand, taking dictation from her own voice, pausing so that the hand could catch up with the mouth. Mila tried to steer her back into the bedroom, but her mother pushed her back and looked up from the page with a quick angry glance. She started walking and dictating again. Mila went back to the sofa and lay down with a pillow over her head to shut out the footfalls and the voice.

‘She holds out very well, even though it’s exhausting, as I told you the last time. Luckily, as I’ve said, there are vacations, and in a way that is surprising for her. And amusing. Surprisingly and amusingly, she sees that after all, all of this, once it has stopped, doesn’t last very long. She gives herself a shake and thinks about something else. Why? Because after all, she knows very well that he’ll realize that there’s nothing to find.’

They hadn’t received any mail in days. Not even junk mail. Worried that there might be a problem with the delivery just when her check was about to arrive, Mila decided to talk to the neighbor. Knives and scissors had been put away a long time ago, but she shut off the gas before leaving, telling her mother she would be back in a minute. Mila locked the door behind her and jogged over to the house across the street. She played with the neighbor’s dog as he told her everything was all right with his mail.

Her mother sat on the sofa, stroking the left armrest, saying ‘remember that it was not today or yesterday that I told you about the glove, the hood, and that dream that Ella had’. Every now and then, Mila told her, as gently as she could, to try to quiet her mind and relax. Her mother always obeyed but only for a few seconds, after which she started talking again. A few times over the last days, Mila had shouted at her, asking her to shut up. Her mother always obeyed but only for a few seconds, after which she started talking again.

‘It’s this cut that’s opened up and allows something to appear, something that you will understand better when I say the unexpected, the visit, the piece of news.’

Mila sat in the study, looking at her father’s things: obsolete computer accessories and cords, framed pictures of himself, a collection of lanyards and IDs from different work events he had attended over the years, some souvenirs from his travels that had once been ironic but now were just ugly things. She was grateful she couldn’t make out her mother’s words.

The general plan – walk around the block, down to the meadow, and then back – found no purchase on her mother’s mind, no matter how many times Mila repeated it. She tried to get her to dress all morning, but she was passively stiff and irritable. ‘The very day they exchanged vows, with a vague cousin, I don’t remember very well, I didn’t look up the biography, let’s say a vague cousin, some person, one of these young handsome men who have, as they say, an assured future, which means they don’t have any.’ Mila tried to explain to her mother that an open vista would do her good after such a long time indoors. ‘For some time, people haven’t been stubborn about it: the important thing is to be together in the same chimney. The question, when you come out, when you come out together from a chimney, is: who is going to wash his face?’ Close to noon, Mila got her mother dressed, but she refused to leave the house. ‘Another baby in the room is enough for it not to happen.’

The voice followed Mila into the bathroom. She examined her face, thinking she ought to look older than she did. A moment later, she found herself plucking her eyebrows, unaware of the moment when she had started. The short, angry plucks were gratifying. The pain building up in her brow was gratifying. Her eyebrows were getting too thin, but they were still uneven. She would have to keep going a little more.

The can opener didn’t work. Mila banged the can on the counter, which made her mother jump. She was quiet for a moment. ‘But both things are true, even if they aren’t connected: it is precisely for this reason that they are confused and that by confusing them, nothing clear is said about this relationship.’ The can turned, but the blade wouldn’t cut into the tin. She made a hole with a knife. The cutting wheel kept skipping out of the groove. Staring at the can and listening to her mother (‘Of course some people have country houses, and they go there to contemplate their collections of, let’s say, beautiful vases’), Mila found herself saying it. It was so sudden it felt out of time. She had often thought about saying it, hoping it would shock her mother into sanity, but never considered it seriously. She would be too scared to tell such a lie. And yet she did. Her body tingled and she felt weightless and not quite real as the words came out. Mila told her mother, with angry compassion, that her husband, whom they both called ‘dad’, was never coming back because he was dead.

In the daytime, the monologues became intermittent, separated by long silences. Mila thought this was an improvement. Her mother sometimes even spoke to her directly – rather than into space – with sensible questions and practical remarks. She was eating less, though. And refusing to wash. The topic of Mila’s father never came up again. At night, however, the monologues grew longer until they became a continuum interrupted only by sunrise.

‘Let’s move along this path, the path I chose today. And let’s forget how the couple was defined at the beginning. That’s the way it should be: we should take things up along the way, and even maybe at the arrival. But we cannot take them up at the start.’

Mila brought out a knitting basket she had found deep in a closet. The mechanical precision and purpose of her mother’s hands; the all-too-human slackness of her jaw and mumbling lips. It was during one of these knitting sessions that her mother, without ever looking up, asked Mila how he had died. Mila had a story ready: pancreatic cancer; so fast he never had a chance; she hadn’t said anything because she didn’t want to upset her; she was so sorry for having blurted it out like that. Her mother never stopped knitting during their short talk. Her bones had become more visible over the last few days. Mila was horrified to find herself thinking that she might not need to discuss her lie with her father after all.

‘When all is said and done, there is nothing except what is current. I sometimes try to see if somewhere some little question mark is not appearing somewhere. I’m rarely rewarded. That’s why people ask me serious questions. Well then, you can’t blame me for taking advantage of it.’

The doorbell. The voice followed Mila out of the living room and to the front door. It was the neighbor with the dog. After asking about her mother’s health, he told Mila her father had just called him. He had been trying to reach Mila over the last few days, but her phone seemed to be dead. The neighbor looked down at this point and patted the dog’s head. Anyway, Mila’s father had asked him to tell her he was in town, at his friend’s place. He would come by the house after lunch. He wanted to make sure Mila would be in. Throughout this short conversation, the voice never stopped flowing from the living room.

Mila shut off the gas, hid all the sharp objects she could find, left some food in plain sight, and explained to her mother she would have to leave for the day. She thought she detected traces of concern on her mother’s face, which she took as a good sign – any kind of response was positive. Mila kissed her on the cheek and went over to the neighbor’s to ask him for $20 for gas. She rang the bell several times. Inside, the dog barked and scratched the door.

A flock of birds had been flying alongside her car for about a mile. Her foot off the gas pedal, Mila tried to coast as much as possible. The fuel warning dash light turned on about halfway there, but she had driven over thirty miles on empty a few times and was confident she would make it to her father’s friend by noon. The birds were now behind her, speckling the unpopulated horizon in the rearview mirror. She would have to tell him the truth – that she had said he was dead. It had been for her mother’s own good. If he really wanted to help, he would have to stay away. This would give him the chance to feel important without doing anything. After that, he would be happy to give her money for gas. The engine let out a huff. Mila looked around wildly, as if she could reach for something that would help her. The engine gasped. She started hitting the steering wheel (a small portion of her, untouched by despair, thought that she was imitating someone in some film). A hollow silence filled the car. As she drifted toward the shoulder, the flock of birds overtook her and flew out of sight.

0 notes

Text

MITOS EN AMÉRICA

MITO 11: CUAUHTÉMOC EL VALEROSO

¿Fue realmente tan valiente como pintan al último tlahtoani independiente de Tenochtitlan.? Hay algunos que lo elevan a Héroe Nacional de México ¿fue realmente un héroe?

Repasemos sus actuaciones y que luego cada uno saque sus propias conclusiones.

Cuauhtémoc fue primo de Moctezuma Xocoyotzin y tras la muerte de Cuitláhuac, Cuauhtémoc fue elegido Huey Tlatoani. Cuando esto ocurrió, los españoles ya no estaban en Tenochtitlán y lo que hizo fue reorganizar el ejército mexica, reconstruir la ciudad y fortificarla para la guerra contra los españoles.

Cuando Moctezuma salió a una azotea de su palacio para intentar calmar los ánimos de sus compatriotas, Cuauhtémoc lo imprecó con violencia: "¿Qué es lo que dice ese bellaco de Moctezuma, mujer de los españoles, que tal se puede llamar, pues con ánimo mujeril se entregó a ellos de puro miedo y asegurándose nos ha puesto todos en este trabajo? No le queremos obedecer, porque ya no es nuestro rey, y como a vil hombre le hemos de dar el castigo y pago". Una fuente afirma incluso que de su mano partió una de las piedras que mataron al emperador.

No se le conoce que participara en ninguna batalla contra los españoles, ni tan siquiera participó personalmente en las batallas para defender su ciudad del enemigo, simplemente permaneció tras su ejército y tras las murallas mientras su pueblo, incluidas las mujeres combatían y morían en cada calle de la ciudad. Esto dice mucho de su liderazgo y hombría.

Nunc a se atrevió a entrevistarse con Hernán Cortés a pesar de las peticiones de este para llegar a un acuerdo y, lo peor de todo es que fue capturado huyendo disfrazado mientras su pueblo moría defendiendo la ciudad.

Un mito muy extendido es que Cuauhtémoc resistió la tortura a la que le sometieron los españoles para que desvelara el tesoro que perdieron durante la Noche Triste. La realidad es que no aguantó mucho y reveló a donde arrojó aquel tesoro, recuperando los españoles parte de él.

Este mito de que Cuauhtémoc resistió sin soltar prenda proviene de una novela histórica escrita por el mexicano Eligio Ancona en 1870 que le atribuye al tlatoani la frase de “¿Y acaso crees que yo estoy en un lecho de rosas?” Este estoicismo de Cuauhtémoc que se muestra en dicha novela se popularizó tanto que ha pasado a la épica patriótica mexicana como algo verídico sin serlo.

Pero en realidad, como ya he dicho anteriormente, aunque al principio resistió la tortura, al final desveló el lugar donde se encontraba el tesoro:

"confesaron que cuatro días antes habían echado en la laguna [...] ansi el oro como los tiros y escopetas que nos habían tomado cuando nos echaron de Méjico". Bernal Díaz del Castillo.

Cuauhtémoc es posiblemente el personaje más reconocido por los mexicanos como héroe nacional. En todos los rincones de México su nombre se usa en toponimia y onomástica, y su imaginada efigie aparece en monumentos. El 28 de febrero de cada año, la bandera mexicana ondea a media asta en todo el país, recordando su muerte. El nacionalismo mexicano ha creado el envoltorio de un heroísmo cuasi mitológico de exaltación de un personaje histórico más bien por tema político que histórico.

La exaltación de este personaje lleva, en cierto modo, a empañar la imagen del personaje en cuestión, ya que está todo fundamentado en mitos, falsedades y tergiversaciones de la historia.

¿Por qué México no venera a los indígenas vencedores, a los indígenas conquistadores como a los Tlaxcaltecas? ¿Por qué México prefiere la imagen de los indígenas que perdieron, de los conquistados? ¿Está cómodo con su imagen de victima? Y ¿cómo es posible que se ensalce a un personaje del siglo 16 como héroe nacional si los Estados Unidos Mexicanos existen desde 1821?

Y tú, ¿qué opinas? ¿Fue un héroe? ¿Un valiente? En mi opinión difícilmente puede considerarse a alguien Héroe que no salvó nada, más bien destruyó su propia ciudad por su empecinamiento, un joven imberbe muy lejos de la experiencia de Moctezuma, y tampoco puede ser considerado un valiente a alguien que huía de la batalla mientras sus hombres y mujeres morían luchando por las propias ordenes de quien huía…

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mujeres

Kimberly Reyes

La actriz, modelo y presentadora Kimberly Reyes posó para SoHo en dos lugares icónicos que han inspirado grandes vallenatos: el Guatapurí y el río Badillo. No se pierda estos increíbles paisajes junto a la mejor compañía. Por: Hernán Puentes

Aunque es costeña, barranquillera para ser exactos, Kimberly Reyes no les había parado mucha oreja a los vallenatos. Los oía y se sabía uno que otro, porque tiene un tío que, sin ser cantante, los canta muy bien. Empezó a escucharlos con juicio para meterse en la piel de Lucía Arjona, la mujer que interpreta en Diomedes, el Cacique de La Junta, de RCN Televisión. Lucía fue la primera esposa del cantante Diomedes Díaz y su musa principal, la que inspiró muchas de sus canciones. Kimberly se siente feliz de representarla y agradece, sobre todo, haber tenido la oportunidad de hacerlo en los escenarios naturales de la costa donde Lucía y Diomedes vivieron su historia de amor. “A este personaje le presté mi cuerpo, pero terminó dejándome más él a mí que yo a él”, dice.

Ella había recorrido con su familia, en plan turístico y de descanso, algunos de los lugares de La Guajira y Cesar donde grabaron la telenovela. Pero representar a Lucía y meterse de lleno en la historia la hizo verlos con otros ojos. Kimberly se emociona al hablar de las experiencias que vivió en Valledupar, San Juan, La Junta, Patillal, Los Haticos, Villanueva, Carrizal, nombres claves en la geografía de vallenato. Una música que hermana a gentes de diferentes regiones y no conoce fronteras departamentales. La actriz quedó prendada de esos paisajes. Por eso aceptó la invitación de SoHo para posar en ellos y mostrárselos a los lectores. Unas fotos que se fijarán para siempre en la memoria.

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

are you researching about pinochet's dictatorship in general, or a specific topic? It makes me sad but I'm thinking about also researching about it

Hi anon! I'm doing my thesis on Retablo de Yumbel, a play by Isidora Aguirre that talks about the Laja Massacre on 1973 under Pinochet's dictatorship. Sadly most of my sources are in Spanish, but the Rememberance and Human Rights Museum in Chile has an english page with first hand testimony and research on the topic from the 60s to present time.

If you want sources as in books, I can recommend Gabriel Salazar's books on the more historical side. But I am a literature major, and the topics that I have a special interest in are the remembrance and narratives around it, so my recommendations go more by that side

In books that are more "tellings" or fictions "Tengo miedo, Torero" (I'm afraid, my bullfighter) by Pedro Lemebel not only sheds light on the dictatorship by itself, but also on queer issues. Isabel Allende's "House of spirits" is absolutely translated and you *should* read her books. Nona Fernández's "La dimensión desconocida" (Unkown dimension) and "Space Invaders" are two of the more recognized modern books on the topic, which are fairly recent and are translated! So give them a read

If you want outright testimony "Tejas Verdes: diario de un campo de concentración en Chile" (Tejas Verdes: Diary of a concentration camp in Chile) by Hernán Valdés tells his own experience in the detention camp. Is the first testimony book about the time published in Chile and you'll find a lot of important stuff in there. Also books like "Amor, te sigo esperando" (My love, I still wait for you) is a new one about mothers and widows that are still looking for their loved ones who disappeared.

If you want theatre, Retablo de Yumbel is one of my favorite plays ever, but also "Los que van quedando en el camino" (The ones that were left behind on the road) also from Isidora Aguirre. Nona Fernández's "Liceo de Niñas" (Girl's High School), Ariel Dorfman's "La muerte y la doncella" (The death and the lady) (This one is noy only tranlsated but presented around the world. You can absolutely find a copy), and Marco Antonio de la Parra's "La puta madre" (Mother whore) are good reads, but I don't know if they're translated. Also I can recommend Juan Radrigán's work, and Jorge Díaz's.

If you want poetry, Raúl Zurita, Damiela Eltit, Nicanor Parra and Víctor Jara. I'm not much of a poetry guy, but I bet you can find a lot of their work translated.

If you look for art, the obligatory one is Miguel Lawner's "Venceremos!: Dos años en los campod de concentración de Chile" (We will win!: Two years in the concentration camps in Chile) which I know for a fact is translated to at least english and portuguese; those are the drawings that represent different scenes on Dawson Island and other camps were Lawner was. You can also look at the Rememberance and Human Rights museum in Chile with a pretty complete collection of art, both in the recognized art world and clandestine and domestic world.

If you're looking for movies, I think "NO" by Pablo Larraín is a very good watch that talks about the end of the dictatorship. Also "1976" by Manuella Martelli. Honorary mention to "Bear Story" by Gabriel Osorio for being a short film with no dialogue that also tackles the topic.

Also shot out to the series "Los 80" (The 80s), which is a chilean soap opera about a middle class family living through the dictatorship and everything that ensues. It's on Amazon Prime, tho I don't know if it's translated.

If you're looking for documentaries, I think "Colonia dignidad: Una secta alemana en el sur de Chile" (Dignidad Colony: A german cult in the south of Chile) is a very good watch. It's on Netflix and completely in english. Also "ReMastered: Massacre in the National Stadium", also on Netflix, talks about the murder of Víctor Jara (Tho there's new developments on the case). But the ultimate ones are everything that Patricio Guzmán ever did. "La Batalla de Chile" (Chile's battle) a series of 3 documentaries that tell the story of the country between 1972 and 1973 on the historical front. In the remembrance front he has "El botón de nácar" (The nacre button) about Villa Grimaldi and the Death Flights and "Nostalgia for the Light" about the Atacama desert, the concentration camp there and other searchings that were done there.

I hope this helps a bit to start. Sorry if I went a little bit overboard, and I do wish you the best researching the topic. These are all off the top of my head so I definitely forgot some important ones lol

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Notaba que pensaba distinto, y sabía que en última instancia no importaba si aquella percepción se basaba en la realidad o en fantasías. Lo importante era que no lograba parar de pensar en sus pensamientos. Sus especulaciones se reflejaban sin cesar entre ellas, como espejos puestos en paralelo, y cada imagen que había dentro de aquel túnel vertiginoso miraba a la siguiente preguntándose si sería el original o una reproducción. Se decía a sí misma que aquello era el inicio de la locura. La mente se convertía en la carne destinada a sus propios dientes.

Hernán Díaz

4 notes

·

View notes