#HATSHEPSUT MORTUARY TEMPLE

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

XPLORALYA: "EGYPT THE LAND OF KINGS"

XPLORALYA: “EGIPTO, LA TIERRA DE LOS REYES” Therese Tawile Secretary General FIJET – LEBANON Travel Writer, Prensa Especializada Egypt is connecting Africa, Asia and Europe through the Mediterranean Sea. Egipto conecta África, Asia y Europa a través del Mar Mediterráneo. Dating back thousands of years the land of Egypt have witnessed the succession of civilizations, the migration of people…

View On WordPress

#AFRICA#AMAZING CROCODILE MUSEUM#ASWAN CITY#CAIRO#EGIPTO#HATSHEPSUT MORTUARY TEMPLE#ISLAM#LA TIERRA DE LOS DIOSES#lomasleido#LUXOR CITY#THE GREAT PYRAMIDS OF GIZA#THE KARNAK TEMPLE COMPLEX#THE MEDITERRANEAN SEA#THE NATIONAL EGYPTIAN HERITAGE REVIVAL ASSOCIATION#THE NEW NATIONAL MUSEUM OF EGYPT IN CAIRO CITY#THE NILE RIVER#THERESE TAWILE#TRAVEL WRITER#TURISMO#VALLEY OF THE KINGS#XPLORALYA

0 notes

Text

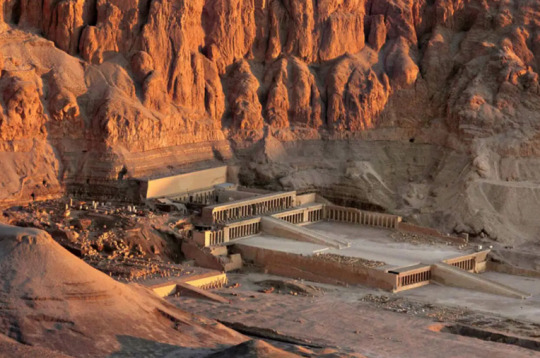

Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut

#Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut#Egypt#Hatshepsut#Luxor#Pharaoh Hatshepsut#Egyptology#architecture#temple#temple design

89 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut: A Masterpiece of Ancient African Architecture

The mortuary temple of Hatshepsut, known as Djeser-Djeseru which means “Holy of Holies,” stands as a remarkable tribute to the reign of Pharaoh Hatshepsut during the Eighteenth Dynasty of ancient Egypt. This architectural masterpiece is nestled opposite the city of Luxor, flaunting its grandeur and significance in the history of African architecture. As you approach the temple, your eyes are…

View On WordPress

#African architecture#African History#Ancient Egyptians#ancient egyptians history#North African History#The Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mortuary Temple of Queen Hatshepsut, Deir el-Bahari

ハトシェプスト女王葬祭殿、デール・エル・バハリ神殿

1 note

·

View note

Text

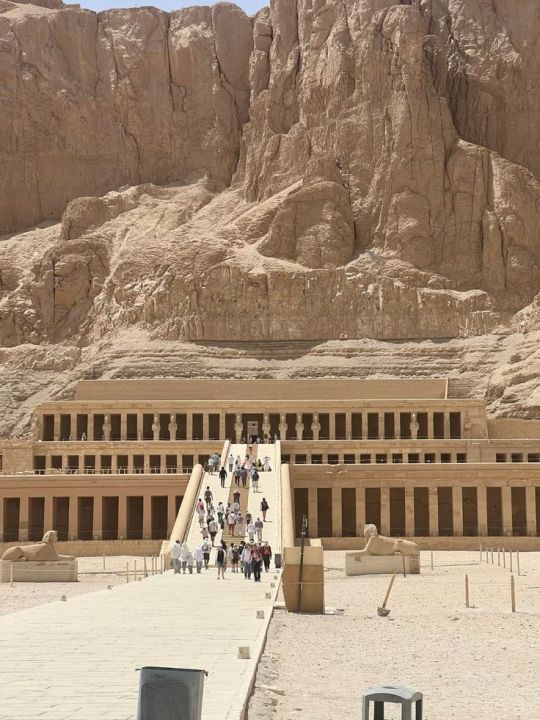

HATSHEPSUT TEMPLE

MORTUARY TEMPLE OF HATSHEPSUT

Djeser-Djeseru, Deir el-Bahari

The temple was built during the reign of Pharaoh Hatshepsut in the 18th Dynasty of Egypt. It is one of the most famous Ancient Egyptian sites which has thousands of tourists visiting it each year. Hatshepsut’s tomb (KV20) lies inside and it was constructed during year 7 (or 12) of her rule.

The temple has suffered through time, after Hatshepsut’s death, Egyptian rulers attempted to erase her name and face; thankfully, most of the references to her on her temple remain intact. Akhenaten ordered the images of Egyptian gods, including Amun to be erased - however his son Tutankhamun and those after him had these damages repaired. There was an earthquake which also harmed the temple during the Intermediate Period. During 6-8th centuries the image of Jesus Christ was painted over reliefs, the last graffiti is dated back to 1223. The temple became popular after a British traveller in 1737 visited the site, excavations wasn’t conducted until the 19th century.

On 17 November 1997, an Islamic terrorist attack took place at the temple. Tourists were targeted, and 62 people were killed and mutilated. At 8:30-9am, the terrorists killed tourists and four Egyptians (including two armed guards). The tourists were trapped inside the temple, when the attack took place and they left a leaflet behind which read, ‘no tourists in Egypt’. The youngest victim was a child aged 5 from England, Shaunnah Turner. Only 26 people survived the attack. Afterwards the terrorists hijacked a bus and ran into Egyptian authorities and a shootout took place, one was injured and the rest fled into the hills where their lifeless bodies were found inside a cave (after taking their own lives). The victims were from Switzerland, Japan, England, Germany, Egypt, Colombia, Bulgaria and France. The perpetrators were from al-Jama’a al-Islamiyya, an Egyptian Islamic group, who was an anti-government force.

#hatshepsut #ancientegypt #mortuarytempleofhatshepsut #djeserdjeseru #deirelbahari

1 note

·

View note

Text

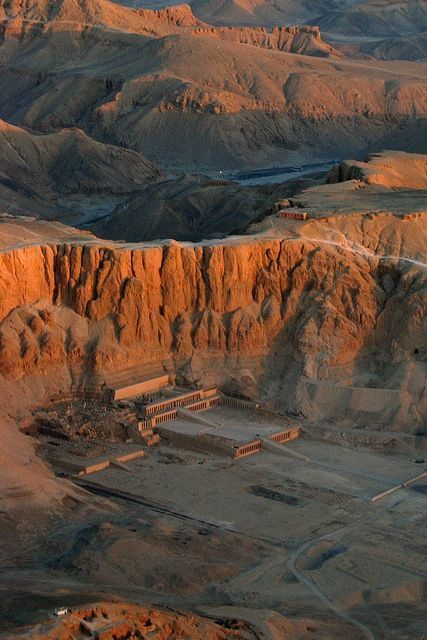

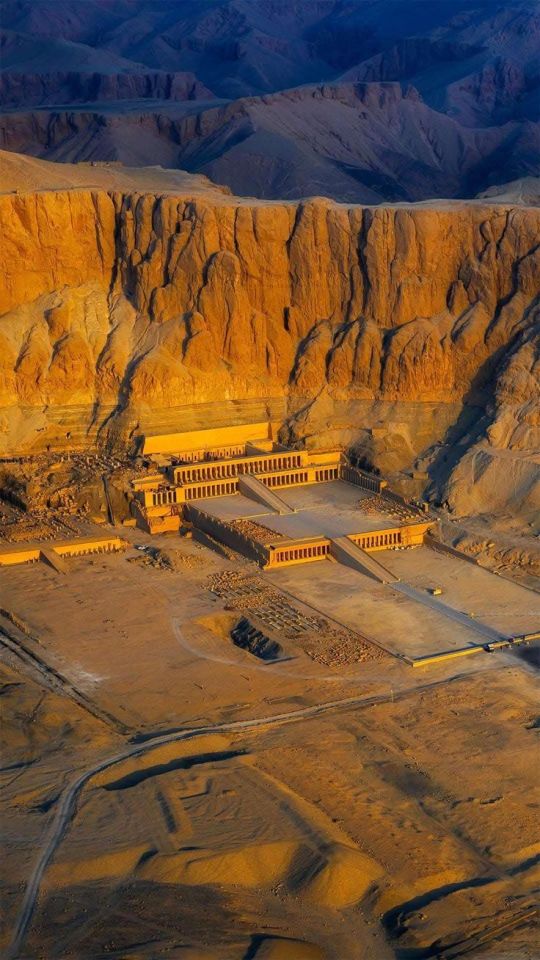

Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut, Medinet Habu, and Mortuary Temple of Amenhotep III

Three quite different temples on the West Bank of Luxor, all close to the Valley of the Kings, visited with a driver in the course of one afternoon along with the Valley of the Queens. The Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut is unique among ancient Egyptian temples for its striking design, and location at the base of the cliffs of Deir el-Bahri. A 1km causeway runs through the centre up three…

View On WordPress

#Egypt#Luxor#Medinet Habu#Mortuary Temple of Amenhotep III#Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut#photography#travel

0 notes

Text

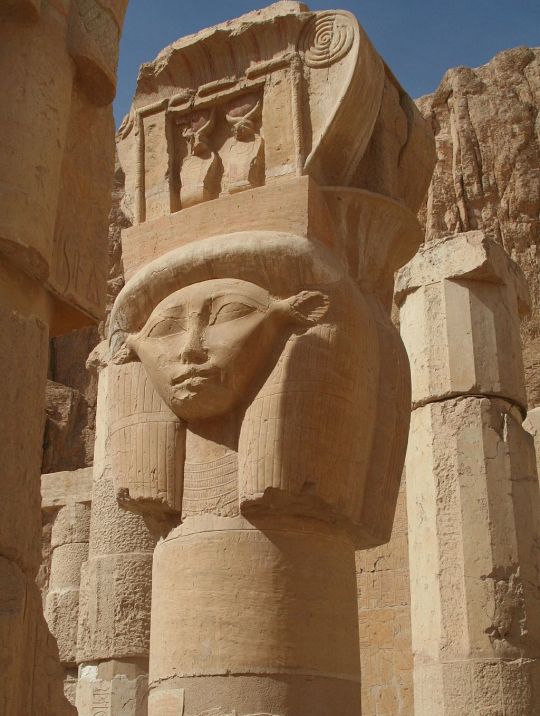

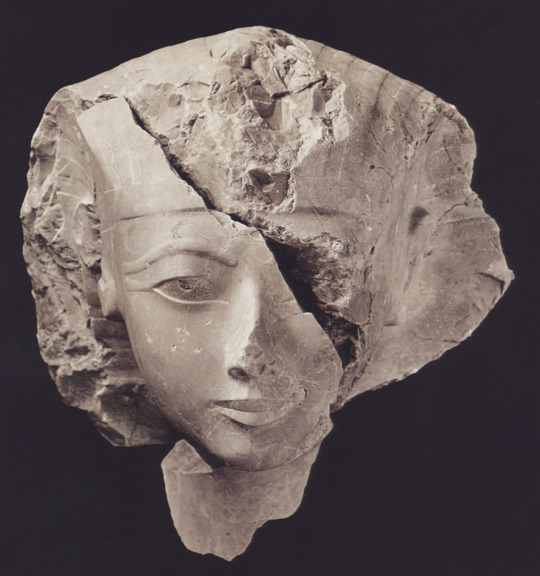

Hathoric capital from the mortuary temple of Hatshepsut.

482 notes

·

View notes

Text

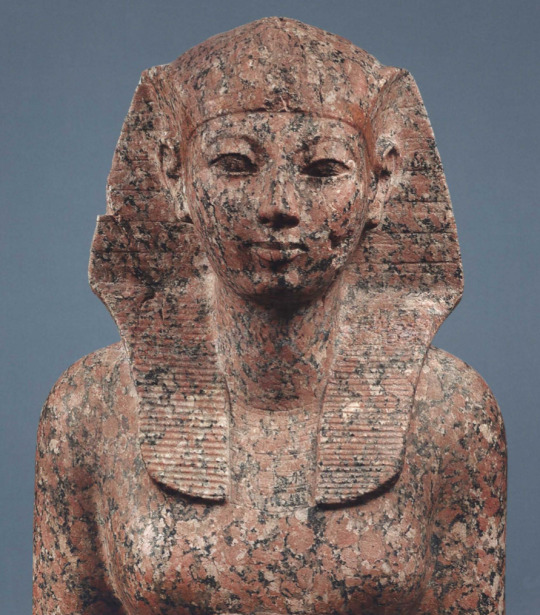

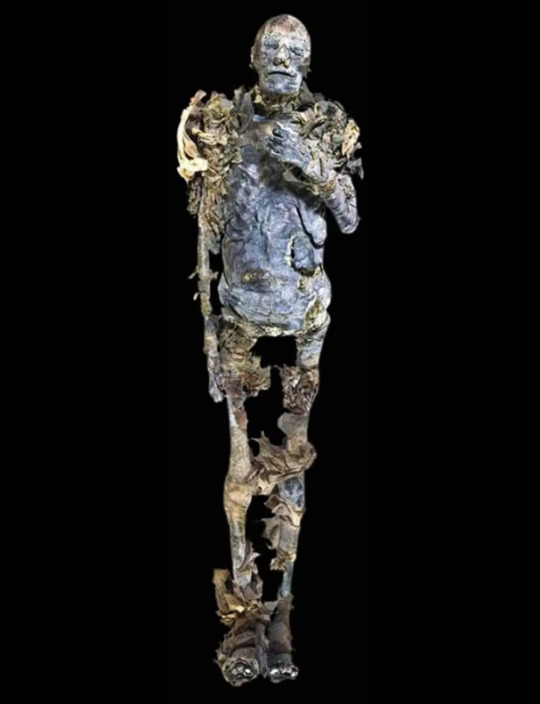

Excavations at Queen Hatshepsut's Temple Reveal Elaborate Burials, Decorated Blocks and Ancient Tools

A number of new discoveries have been made near the mortuary temple of Queen Hatshepsut in Egypt.

Archaeologists working in Luxor, Egypt, recently made several discoveries in the area around Deir al-Bahari (also spelled Deir el-Bahari and Dayr al-Baḥrī), the famous mortuary temple built by Hatshepsut, a woman who ruled Egypt as a pharaoh.

The team found the temple's "foundation deposit" — objects that the ancient builders buried when they began construction of the temple. The artifacts found include an adze, a tool used to cut and shape wood; a wooden hammer; two chisels; a wooden cast model for making mud bricks; and two stones that contain Hatshepsut's cartouches, ovals with hieroglyphs that can represent a ruler's name, Zahi Hawass, a former head of Egypt's Ministry of Antiquities who is leading the excavation team.

The mortuary temple was known as Djeser Djeseru in ancient times, and the adze, hammer, cast model and one of the chisels have inscriptions saying "the good god Neb Maat Re, in the temple Djeser Djeseru, beloved by Amun," Hawass said. Amun was the chief god of Thebes, which is now Luxor. The words "Neb Maat Re" refer to the name and some of the titles of the sun god Re (also known as Ra).

The team also uncovered 1,500 colorful stone blocks that were part of Hatshepsut's valley temple, which was located near her mortuary temple. The valley temple would have been decorated with a variety of scenes, some of which can still be seen on the blocks.

Hatshepsut was a female pharaoh who reigned from about 1473 to 1458 B.C, during the 18th dynasty. She was the stepmother of Thutmose III, who at times served as co-ruler and succeeded her after her death. Hawass said the team found evidence that Thutmose III restored Hatshepsut's mortuary temple sometime after her death. After the death of Hatshepsut, some of her statues and inscriptions across Egypt were destroyed but, in this case, Thutmose III sought to restore her temple.

Other finds in Luxor

The excavation team made a number of other finds in Luxor, including a cemetery dating to the 17th dynasty (circa 1635 to 1550 B.C.), when parts of Egypt were controlled by a foreign people called the Hyksos. Within the cemetery, the team found coffins holding the remains of ancient Egyptians. While excavating the cemetery, the team also found the remains of bows and arrowheads — weapons that would have been used to fight the Hyksos, Hawass wrote in a statement on Facebook. It's possible that some of the cemetery guards took part in the fight against the Hyksos.

The team also found the tomb of Djehuty Mes, who was an overseer of the palace of Queen Tetisheri. There is some debate about which pharaoh she was married to, but Queen Tetisheri lived during the 17th dynasty and possibly into the early 18th dynasty. Inside the tomb, archaeologists discovered a limestone offering table, a limestone funerary stela (commemorative stone slab), and a cosmetics vessel made of alabaster and faience (glazed ceramic), Hawass said.

Aidan Dodson, an honorary professor of Egyptology at the University of Bristol in the U.K. who was not involved in the excavation, said, "For me, the most important is the discovery of the blocks from the valley temple of Hatshepsut." While "her main temple has been extensively excavated and studied since the mid-19th century," Dodson said, "the valley temple was only briefly examined by Howard Carter some 120 years ago."

Analysis of the team's discoveries is ongoing.

By Owen Jarus.

#Excavations at Queen Hatshepsut's Temple Reveal Elaborate Burials Decorated Blocks and Ancient Tools#Queen Hatshepsut#Deir al-Bahari#Luxor#ancient temples#ancient tombs#ancient graves#ancient artifacts#archeology#archeolgst#history#history news#ancient history#ancient culture#ancient civilizations#ancient egypt#egyptian history#egyptian art#ancient art

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mortuary temple of queen Hatshepsut 🇪🇬📍

معبد الملكة حتشبسوت

24 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A Gallery of Ancient Egyptian Temples

The temple in ancient Egypt was the home of the deity it was built for, and the clergy attended the statue of that god or goddess as they would a living person. Every temple was designed with a forecourt, a reception area for public gatherings, and an inner area, which included the Holy of Holies where the god lived.

This room, which housed the statue of the god, could only be entered by the high priest who would commune with the deity and intercede for the king and people. Each temple was understood as the point at which that god or goddess had come into the earthly plane in the earliest times and so were linked with the ancient past, no matter when they were built. They were also designed to represent the ben-ben, the primordial mound of earth, which rose from the watery chaos at the beginning of time and upon which the god Amun stood to create the world. Exceptions to this paradigm are mortuary temples dedicated to monarchs, as in the case of Hatshepsut, but even these were constructed with the gods in mind.

This gallery presents a sampling of some of the best-known and lesser-known temples of ancient Egypt (most from the New Kingdom, c. 1570 to c. 1069 BCE) along with images of some of the gods worshipped. The only exception to this is the god Bes who is thought to have had, at most, one temple dedicated to him but was sometimes venerated at temples or shrines dedicated to the goddess Hathor, as at her birth house in Dendera.

Continue reading...

87 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shrine of Hathor

Hathor Chapel in the Temple of Thutmose III. at Deir el-Bahari, Thebes, photo from the excavation by Henri Édouard Naville (1907).

The shrine of Hathor and the cow’s statue were retrieved from under heaps of debris south of the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahari. The shrine is from the reign of Thutmose III. Its roof is painted blue with yellow stars to imitate the Vault of Heaven.

The statue of Hathor as the divine cow, in the middle of the shrine. It is inscribed for Amenhotep II, Thutmose III’s son and successor.

New Kingdom, mid 18th Dynasty, ca. 1479-1425 BC. Now in the Egyptian Museum, Cairo. JE 38575

Read more

220 notes

·

View notes

Text

In Egypt

I was fortunate to travel to Egypt 4 times and photograph many historic locations from the ancient times to the medieval era. These are my favorite architecture photos from Egypt capturing its history. The images are the following: Luxor Temple at night, Luxor Temple columns at night, the mortuary temple of Hatshepsut, an aerial shot of the pyramid of Khafre, a section of the court yard of the Citadel of Saladin, and the interior of main cupola of Citadel of Saladin.

Photographer: Laszlo Andacs

International Photography Awards

28 notes

·

View notes

Note

I forgot one number, then just decided to ask more, if you wouldn't mind. 18, 21 22, 23, 24, 25, and a random one, 46, please. Also make sure to take your medication on time.

18. How does each Bishop handle conflict or arguments with their siblings?

Shamura: Here is a point by point rhetorical argument about why I’m right.

Kallamar: Conflict? What conflict?! You’re totally right, what was I thinking!

Heket: [Impassioned shouting and swearing]

Leshy: You may be right but I can be the biggest, most annoying pain in the ass until you give me what I want anyway.

Can’t imagine why their family would have any issues when these are the communication styles we’re dealing with lol.

21. Describe the interior design of one of (Or all) the Bishop’s temples.

Shamura: Grecian style temple covered in spider webs. Giant tapestries depicted their victories. The webs were laid out in such a way that Shamura could always sense who was moving where in their temple. There was also a grand library that gradually fell into decay as their state deteriorated.

Kallamar: Think Hanging Gardens of Babylon, but underwater. Covered in a variety of corals, anemones, and reefs, it was a riot of color and beautiful to look at. Inside was well lit with magic lights and full of massive statues, colorful crystal decorations. At its peak, his temple was a haven for art, music, and beauty of all kinds.

Heket: Her style was more simple, almost Egyptian in its styling. I imagine something like the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut, though covered in fungus. Her mushroom garden gradually overtook the temple, and it was carefully cultivated. As a result, her temple was always a bit…humid lol. But she never minded that.

Her temple had the most extensive and well-stocked kitchen in the entire Lands of the Old Faith. She also had a large pool that she would take a dip in occasionally.

Leshy: A large intricate wooden temple that was always under construction. In part because Leshy never really cared about regular maintenance, leading to parts that would periodically collapse/get damaged by time/the weather. The other reason was that Leshy often changed his mind about what he wanted. Sometimes he would smash parts he wanted redone, which is why it was made of wood. Easier for destroying.

In general, it was much like Leshy himself: covered in moss, surrounded by trees, with greenery growing up wherever it can manage. He also featured bits from his siblings’ temple in his own, typically art such as tapestries/sculptures/paintings/etc.

22. How do each of them recruit followers?

Most of them would make promises relating to their domains. Shamura has all the answers; Kallamar can give you a long healthy life; Heket can make sure you never go hungry again.

Leshy was a bit different. He recruited followers by highlighting the bright spots of his worship: frequent feasts and festivals, holidays, dancing, drinking, etc. He just didn’t mention the whole I-eat-lots-of-followers thing.

23. Which Bishop is strictest with their followers, and which is the most lenient?

As one might expect, Shamura was the strictest. Leshy was the most lenient, but his moods and interests changed often. Meaning rules changed whenever he felt like it lol.

24. What rituals or traditions are unique to each Bishop’s cult?

Rite of War - A ritual that fell out of practice in Shamura’s cult once the Holy War ended, but was occasionally done for ceremonial purposes afterward. Warriors gather, chant praises to Shamura, and offer a bit of their blood into a bowl. Each of them would then drink from it and be empowered for the next 24-48 hours, giving them a noted boost to their combat skills and energy. However, those who survived the battle were sacrificed to Shamura. Those who fell received places of honor in the cult’s crypt.

Despite the fact it meant their certain death, warriors fought to win a place among this Rite, as you could do legendary feats before laying your life down.

Plaguebringer Ritual — A staple of Kallamar’s worship during the Holy War and the sheep genocide. A follower is chosen as the Plaguebringer. They stand at the center and are prayed over, then given a substance to swallow. This would depend on the type of plague itself, but it was rarely pleasant.

From there, the follower is sent out to the target area. Anywhere they go, anything or anyone they touch, will be tainted by the miasma of a supernatural plague. Eventually, they themself would succumb as well, typically after three days or so. Kallamar used this to wage biological warfare on their enemies.

Ritual of the Harvest — Though shared with her family’s cults, this ritual originated with Heket. She used this to feed her followers, and gain entire villages of new ones on occasion. Early into her tenure as goddess, Heket would visit villages whose crops failed and raise them with this ritual. The villagers would be so grateful they typically converted on the spot. She also used this to avert a number of famines that might have otherwise afflicted the Lands of the Old Faith.

Rite of Chaos — Invoked when Leshy was bored. This ritual involved his followers drinking drug-laced wine. The effect on each follower was random: some became euphoric, some manic, some crazed. Sometimes it resulted in the followers having mass orgies, sometimes it resulted in the followers fighting/killing/eating each other.

It always made a giant mess, but it kept Leshy entertained, so that was all that mattered.

25. How involved is each Bishop in their followers' daily lives?

Prior to Narinder’s imprisonment, Shamura was extremely involved in their cult’s goings-on, often irritating their high priests by handling most matters personally. After their injury, however, they became distant and rarely interacted with followers.

Kallamar and Heket were both very active in their cults from beginning to end. Most of their followers would see/interact with them at least once or twice in their lives.

Leshy went from not very involved at all to probably the most attentive god in the family. He knew the vast majority of his followers well, largely because the ones he disliked/didn’t care were eaten.

46. How would each Bishop react if they were spared and brought into a new cult?

Ha!

I’ve written most of their reactions in Reconciliation. Leshy was distrustful, Heket even more so. Only Kallamar was relieved to be brought back and freed from godly responsibility.

Shamura…well, they’re going to be a bit confused, let’s say.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut, Luxor, Egypt, World Heritage

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut, Luxor

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hatshepsut's Mortuary Temple Complex, situated across the river from the modern city of Luxor. The temple is three stories tall, connected by ramps and terraces. In its day, it contained shrines, chapels, and the sanctuary of Amun-re. These were all woven together with carved reliefs, reflecting pools, and elaborate gardens of exotic plants and trees. Her temple rose from beside the River Nile with a long ramp ascending from a courtyard of trees and small pools to a terrace. Some of these trees were brought from Punt and are the first known successful transplants of trees from one nation to another in history. The remains of these trees, fossilized tree stumps, can still be seen in the courtyard of the temple in the present day.

Symbolism abounds in Hatshepsut’s mortuary temple; symbols that suggest Hatshepsut had a divine right to rule. The temple is not only home to the mortuary shrine dedicated to Hatshepsut, but also includes sanctuaries dedicated to the gods Anubis, Hathor, a local incarnation of Amun, Re, and Hatshepsut’s father Thutmosis I. Hatshepsut honored the god Amun by placing his shrine in the central position of the temple rather than her own, as was normal for pharaohs. By including a shrine to the god Hathor, Hatshepsut symbolically revitalized the tradition of monumental architecture that began in the pyramid building era, which typically included shrines honoring Hathor.

The temple of Hatshepsut was considered to be a wonder of the ancient world by architects. Located at the bottom of limestone cliffs, the temple had courtyards and terraced colonnades that seems to be going up the side of the mountain. The lower levels of the temple had gardens with fragrant trees and pools. The temple had huge images of Hatshepsut with over 100 large statues of Pharaoh Hatshepsut as a sphinx, guarding the processional way. Hatshepsut's burial chamber (tomb KV20) was carved out of the cliffs which form the back of the building.

Hatshepsut's temple was so admired by the pharaohs who came after her that they increasingly chose to be buried nearby and this necropolis came to eventually be known as the Valley of the Kings.

The building of the temple was probably overseen by Senenmut, her trusted advisor who some researchers speculate may have also been her lover.

Queen Hatshepsut (1507-1458) was the longest reigning female Pharaoh in Egyptian history, ruling from 1473-1458 BCE. Hatshepsut was daughter of Ahmose, named from her grandfather Pharaoh Ahmose I, who ruled before Thutmosis I and founded Egypt’s eighteenth dynasty. Hatshepsut’s daughters were more closely related to the royal dynasty than Thutmosis III or his son and heir.

9 notes

·

View notes