#H.R. 354

Text

Upcoming: H.R. 354 LEOSA Reform Act of 2024

H.R. 354 LEOSA Reform Act of 2024, sponsored by , is scheduled for a vote by the House of Representatives on the week of May 13th, 2024.

0 notes

Text

Upcoming: H.R. 354 LEOSA Reform Act of 2024

H.R. 354 LEOSA Reform Act of 2024, sponsored by , is scheduled for a vote by the House of Representatives on the week of May 13th, 2024.

https://ift.tt/s2Hw3Ry

0 notes

Text

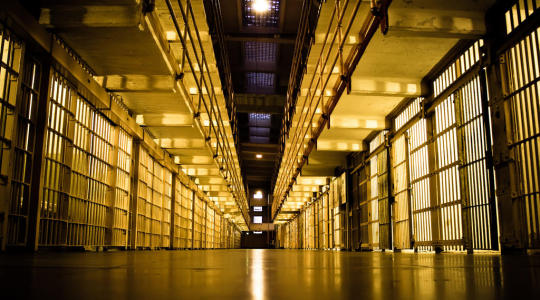

ESSAY: Examining the PLRA

Cases have been recorded of inmates' grievances rejected by the prison administration for writing in the wrong color of ink, for scribbling on the back of the form, or for missing the narrow window of filing deadlines. Many argue that prisoners flung into this Kafkaesque labyrinth of mechanisms will find their cases—no matter how meritorious—consigned to oblivion.

To describe the legal system of the United States as beleaguered is an understatement. Confronted with bulging carceral populations, soaring costs, and an influx of litigation, our courts have, time and time again, fought to keep from buckling under the strain of their caseloads—often at the cost of yielding where they should uphold their commitment to the rule of law. Within the workings of this overwhelmed system, the appellate courts play the vital role of a filtering apparatus. In 1995, approximately fifteen percent of the civil suits received by federal courts were filed by prisoners. Of these suits, ninety-seven percent were dismissed, with only thirteen percent granted declarative or injunctive relief (Schlanger 2). This astonishingly low success rate reflected the presumption—whether canard or fact—that a majority of prisoner litigation was frivolous, and unworthy of courts' attention. Indeed, by the 1990s, the volume of inmate claims had reached such heights that Congress was compelled to address the crisis. In 1995, in a hearing before the Senate for the Department of Commerce, Justice, and State, it was reported:

The number of lawsuits filed by inmates has grown astronomically – From 6,600 in 1975 to more than 39,000 in 1994. These suits can involve such grievances as insufficient storage locker space, a defective haircut by a prison barber, the failure of prison officials to invite a prisoner to a pizza party for a departing prison employee, and yes, being served chunky peanut butter instead of the creamy variety (U.S. Senate. Dept. of Commerce, Justice and State 1995).

To combat the pandemic, Congress enacted the Prison Litigation Reform Act (hereafter referred to in this paper as the PLRA) in 1996. Intended as a mechanism to close the floodgates of litigation, the PLRA's provisions seek to restrict meritless inmate suits so that higher-quality cases may be allowed review on the court docket. One provision states that no inmate shall bring forward a suit under federal law, until all available "administrative remedies" are exhausted. Additionally, under a second provision, the PLRA imposes a negative penalty—a "strike"—wherein a court may dismiss a prisoner's lawsuit on the basis that it is frivolous, malicious or has failed to state its claim (Boston & Manville 564-550).

At the time of its passage, the PLRA garnered widespread bipartisan support as it was intended to ameliorate the judicial process. To be sure, following its enactment, the volume of prisoner litigation significantly dropped. Barely within four years of its passage, the total number of prisoner lawsuits in federal courts declined by 40%. More significantly, the PLRA's broad provisions were lauded for ferreting out "junk litigation" and subsequently reducing the burdensome judicial workload. However, these same features sparked fierce backlash. Many believed that, far from streamlining inmate claims, the PLRA introduced a thicket of administrative barriers intended to discourage inmates from airing serious abuses (Ostrom et al.1536).

Prior to 1996, the standard for grievance processes was set by the Justice Department, and was intended predominantly for federal prisons. The PLRA has cast this aside; as of today, there are no regulations outlined for prison grievance procedure. Critics are also concerned with the capricious nature of the regulations themselves. Cases have been recorded of inmates' grievances rejected by the prison administration for writing in the wrong color of ink, for scribbling on the back of the form, or for missing the narrow window of filing deadlines (Hearing on H.R. 4109, Prison Abuse Remedies Act of 2007). Many argue that prisoners flung into this Kafkaesque labyrinth of mechanisms will find their cases—no matter how meritorious—consigned to oblivion.

Over two decades have passed since the passage of the PLRA. However, it continues to stir contentious debate—among scholars, politicians and inmates alike. As recently as August 21, 2018, a nationwide prison strike was launched, in an attempt to expose the worrisome underbelly of prison administrations. The strike was spearheaded by the Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee (IWOC), a prisoner-led trade group. Intended to unionize incarcerated persons, the IWOC values emancipation, equal rights and community safety. With their championing, the prison strike attracted significant media attention, as well as garnering widespread inmate solidarity. Similar strikes were reported to have spanned across prisons in California, Delaware, Washington, Texas, Indiana, Nevada, New York, and even Nova Scotia, Canada. Prisoners outlined ten demands, including improved prison conditions, more funding for the implementation of rehabilitative programming, an end to life without parole sentences, and, most pertinent to the scope of this paper, the rescission of the PLRA so that inmates would be allowed "a proper channel to address grievances and violations of their rights" (“Prisoners Demand Reforms, Better Conditions...”) Given the hermetic nature of carceral systems in the US, grievance procedures prove invaluable in maintaining fairness within the hierarchical placement. The IWOC therefore argue that the PLRA's provisions seriously impede prisoners from securing a humane redress for their issues (Lopez 1).

Conversely, proponents of the PLRA argue that, whatever its perceived shortcomings, the Act demonstrates success in eliminating procedurally weak cases from the court docket. What's more, they call attention to the fundamentally litigious nature of inmates in general—as well as the fact that not all their complaints, however valid, merit the attention of the courts. The National Association of Attorneys General (NAAG), for instance, argues that PLRA is a safety valve that restores balance to the nature of prisoner litigation. Founded in 1907, the NAAG's mission is to foster state, federal and local engagement on legal issues. Their core values are dedication, integrity, collaboration, cooperation and inclusiveness. Since the PLRA's passage, they have steadily defended it as sensible mechanism to deter inmate-based judicial abuses. Indeed, in 2005, the NAAAG estimated that inmate civil rights litigation cost taxpayers over $81 million—and that most of the costs were incurred by insubstantial lawsuits (Newman 525-27; Shay & Johanna 300).

Whatever its empirical benefits or its administrative shortcomings, the fact remains that the PLRA is extremely complex in both its interpretation and application. For its supporters, it is a valuable tool for judicial sifting, staving off a deluge of baseless inmate suits. For its critics, it is a coercive instrument of civil rights abuses, enabling the authoritarianism of prison regimes. For the sake of brevity, not all the provisions of the PLRA will be examined in this paper. Relevant to our interests are section 42 U.S.C. § 1997e (a) of the Act, which details its administrative exhaustion requirement, and 28 U.S.C. § 1915(g), which deals with its "Three-strike" provision in appeals courts (Hobart 982-994). The Constitutional legitimacy, doctrinal coherence and administrative merits of these two sections have received extensive academic debate. However, rooted in each argument are the core values of justice and equality—as well as whether the Act delivers them, or renders them cruelly illusory. Prisoners constitute an invisible—and highly vulnerable—population bloc. Denied the bargaining power available to other segments of society, it therefore becomes critical to examine the PLRA from a lens of efficacy versus equilibrium.

Accordingly, it requires us to ask: Should the "Exhaustion" and "Three-strike" provisions of the PLRA be repealed? The aim of this paper is to answer this question through a careful examination of the PLRA's history, current legislative contentions and proposed remedies, parties to the controversy, and the arguments presented for and against the PLRA's two most tendentious provisions. This paper will seek to understand the core values of each side, the moral reasoning behind, and consequences of, their particular standpoint, before concluding with a potential solution for the matter at hand.

History

Prior to the 1960s, federal courts adopted a "hands-off" approach vis-à-vis prisons. Treated as regimes unto themselves, prison and jail inmates were deemed second-class citizens at best, non-entities at worst. Accordingly, their grievances were given little standing in the courts. Ruffin v. Commonwealth (1871) best exemplifies the federal bench's attitude toward prisoners. Referring to prisoners as "slaves of the State," the Supreme Court denounced their legal identities with the statement, "The bill of rights is a declaration of general principles to govern a society of freemen, and not of convicted felons" (Dubber 123; Wright 18). Accordingly, prison conditions and resultant complaints were left for individual correctional administrations to handle as they saw fit. While cases such as Ex Parte Hull (1941) and Coffin v. Reichard (1944) augured footings for inmate claims in courts, the corrections system remained, on the whole, a "shadow world" beyond judicial oversight (Schmalleger and Atkin-Plunk 102; O‘Lone v. Estate of Shabazz 354-55).

To be fair, this hands-off doctrine was based less on malicious indifference than on the fact that correctional institutions were freed from judicial interference under the separation of powers rationale. However, the opacity also lent itself to coercive penal policy, unchecked administrative abuses, and squalid living conditions within prisons (Blackburn et al. 246-249). By the 1960s, concomitant with the Civil Rights Movement, prisoners began agitating for improvements to their station. Backed by lawyers and civil liberties organizations, they sought to challenge what they deemed to be legal barriers to fairness and equality in courts, meaningful avenues of redress, and procedural and substantive rights. The following two decades would see the Supreme Court consistently vindicate prisoners' Constitutional rights (Hawkins and Alpert 11). Under 42 U.S.C. § 1983, it was declared: "Every person who, under color of any statute... subjects, or causes to be subjected, any citizen of the United States... to the deprivation of any rights, privileges, or immunities secured by the Constitution and laws, shall be liable to the party injured in an action at law, suit in equity, or other proper proceeding for redress" (Capistrano 1).

Landmark rulings such as Monroe v. Pape (1961) and Cooper v Pate (1964) heralded the era of due process rulings for state and federal prisoners (Muraskin 150). In defiance of a longstanding tradition of judicial detachment, courts assured petitioners easier legal access, religious freedom, medical treatment and protections from racial discrimination, going so far as to state "There is no iron curtain drawn between the Constitution and the prisoners of this country" (Waltman 74). This would mark the beginning of the "Open Door Policy" that characterized judicial attitudes towards prisoners, culminating in a 1970 speech by Chief Justice Warren Burger before the National Association of Attorneys General, which called for the implementation of prison grievance procedures (Coyle 52). Manifesting in the shape of 'administrative remedies', these were intended to combat the issue of besieged courts, without curbing inmates' access to them in the event of civil rights abuses. However, these rudimentary grievance mechanisms would prove inadequate. By the 1980s, Congress enacted the Civil Rights of Institutionalized Persons Act (CRIPA) as a sweeping overhaul of prison conditions. Particularly noteworthy was CRIPA's ability to award attorneys the power to remedy lawsuits related to "egregious or flagrant conditions" in prisons (Holt 15). At the same time, CRIPA also required prisoners to exhaust administrative alternatives before accessing federal courts. This was intended as a careful counterweight to the surge of inmate litigation that would inevitably reach the courts themselves (Edelman 233-245).

While CRIPA was well-intended, and served as a predecessive blueprint for prisoner litigation, the social narrative surrounding prisoner's rights was shifting. By the mid-1990s, the amount of filings in federal district courts had risen from 42,000 to 68,000, leading the New York Times to remark: "After three decades of startling growth, civil rights lawsuits brought by inmates protesting prison conditions in New York and elsewhere across the nation have become one of the largest categories of all Federal civil filings" (Dunn 1). This was not lauded as a sign of progress, but an impediment to proper judicial functioning. The nature of inmate claims was deemed irrelevant or merely petty: dealing with melted ice cream, lack of shampoo, and an inmate's right to put on a bra (Hudson 22). The NAAG compiled "Top Ten Inmate Lawsuits" lists, which included the now-notorious case of the inmate suing over chunky peanut butter (Wright and Pens 58). Media campaigns decrying the inanity of these suits soon cultivated a public contempt for prisoner-litigants as a whole. As the tough-on-crime weltanschauung sweeping Capitol Hill reached its zenith, many began questioning the effectiveness of CRIPA's grievance model, which did not seem to address the Constitutional violations in prisons so much as clog the court systems with unnecessary chaff (Reams and Manz 58-82).

In response, Congress drafted the PLRA, aiming to remedy the disorder in the federal courts. Senator Orrin Hatch and Senator Bob Dole, key sponsors of the bill, justified its proposal by citing the low success rate of prisoner suits, arguing that only an infinitesimal amount carried enough merit to be heard in court. Senator Dole, quoting Chief Justice Rehnquist's complaint that prisoners "litigate at the drop of a hat," went on to state, "The bottom line is that prisons should be prisons, not law firms" (U.S. Senate 1995). The NAAG praised this legislation as deliverance from a crippling workload; their Inmate Litigation Task Force wrote to Senater Dole, expressing a "strong support" for the PLRA as the solution to a burgeoning crisis (Sullivan 422). Conversely, prisoner advocates criticized the touting of absurd inmate claims as political subterfuge. Judge Newman of the Second Circuit, for instance, argued that the "poster child" cases mentioned by the PLRA's proponents were anomalies, and that prisoner's suits dealt with subject matter far graver in nature than critics suggested ("Free the Courts From Frivolous Prisoner Suits" 1). Similarly, Jon O. Newman, a federal appeals judge, stated that the anecdotes of frivolous litigation were either taken out of context, or "at best highly misleading and, sometimes, simply false" (521).

Current Policies

Whatever the case, the PLRA was passed in 1996, packaged as a rider to the appropriations bill—the Omnibus Consolidated Rescission and Appropriations Act of 1996. Designed to limit non-meritorious lawsuits by imposing a structural seal, the PLRA instituted multi-pronged requirements before inmate claims reached federal court. For one, it limited judicial intervention into carceral management, previously promulgated by consent decrees (court-ordered reforms imposed via settlements) unless the least "intrusive" means were implemented to correct the issue. Other provisions included the preclusion of inmates suing for mental or emotional suffering as opposed to physical injury; and the elimination of the traditional waiver of the filing fee (then $150) for indigent petitioners. In addition, the PLRA enabled courts to dismiss suits for frivolity/maliciousness/failure to state a claim, and expected them to have exhausted all administrative remedies before pursuing legal redress in court (Sercye 475-477).

The latter two provisions are most significant for our purposes. The first, Section 42 U.S.C. § 1997e (a), modeled itself on the armature laid out by CRIPA. Similar to its antecedent's exhaustion mandate, the PLRA does not allow prisoners to bypass administrative remedies before bringing lawsuits to federal court. However, whereas CRIPA allowed courts to decree the exhaustion of administrative mechanisms at their discretion—i.e. where they deemed it "appropriate and in the interests of justice" (Weiss 3)—the PLRA's exhaustion requirement is compulsory. The strict adherence to this provision was underscored in Booth v Churner (2001), where the petitioner argued against the exhaustion requirement when administrative remedies could not suffice for the nature of relief sought. However, in a unanimous opinion, the Supreme Court stated that regardless of the nature of the administrative remedies, the prisoner is required to go through the procedure of exhausting them. Justice Souter wrote for the Court, "we think that Congress has mandated exhaustion clearly enough, regardless of the relief offered through administrative procedures" (Booth v. Churner 1; Palmer 84)

A second vital component of the PLRA, Section 28 U.S.C. § 1915(g), is meant to impose consequences of prisoners who consistently bring frivolous lawsuits to court—the "frequent filers", so to speak (Peck). Firstly, it requires judges to dismiss an inmate petition sua sponte—"of one's own will," referring to a judge's order made without request by the parties in the case—if it is deemed to be "frivolous, malicious, fail[ing] to state a claim upon which relief can be granted, or seek[ing] monetary relief from a defendant who is immune from such relief." Dismissal for one of these four reasons will incur a "strike." A prisoner with three strikes becomes ineligible from claiming filing status in forma pauperis (IFP). This status was created by Congress to allow indigent citizens—prisoners included—to forgo the payment for filing fees on a temporary basis. A prisoner who has thrice had their claims dismissed on the basis of malice, frivolity, failure to state a claim, or monetary relief sought from those immune to the action, therefore risks losing access to the courts (Cordisco 2)

Since its passage, the PLRA has garnered both praise and contention alike, with circuit courts split concerning its financial utility and its doctrinal coherence. For its proponents, the PLRA's successes are both symbolic and substantive. Not only has Congress remedied the excess litigation swamping federal courts, but it has transformed the proverbial "deluge" into a dribble—dropping over 41,000 lawsuits to about 24,400, despite a concurrent 23% swelling of the prison population (Doran 1040-1041). For its critics, however, the PLRA has further exacerbated the "outsider" status of prisoners, overcomplicating grievance processes through what amounts to little better than "a sophisticated social control mechanism serving only bureaucratic interests" (Bordt and Musheno 7). What's more, they argue that prisoner litigants, already contending with barriers in the form of undersourced counsel and blockages to generic court access, must now navigate through an additional maze of rules.

Whatever its merits and demerits, the PLRA remains a monolithic statute, untouched by trends in judicial policymaking. Indeed, it can be argued that as the United States increasingly adopts the Foucauldian hallmarks of a carceral society, the PLRA proves instrumental in shaping the Constitutional rights of prisoners, as well as their demarcations and applications. On the flipside, in amassing the largest correctional system in the world, the PLRA proves pivotal in sieving out unnecessary caseloads, and in alleviating the expenses for federal courts. As such, it is essential to more closely examine the Act from the eyes of both its beneficiaries and its naysayers, in order to assess its consequences on current and future inmate litigation.

Stakeholders: The Proponents

To be sure, while the proponents and opponents of the PLRA appear to sit on diametrically opposite sides of the argument, their goals intersect in one critical sphere: introducing structural efficacy in prisoners' access to the civil justice system. Where they differ is in their characterization of the content that the prisoners bring to the courts: problematic frivolity on one side, deprivations of constitutional rights on the other. In understanding the values that each stakeholder adheres to, their stance becomes easier to comprehend, with their approach to the PLRA extending beyond self-interest to the particular belief systems that permeate the very policies they espouse. This proves critical when deconstructing the "Administrative Exhaustion" and "Three-strike" provisions of the Act, as it highlights attitudes not only toward carceral populations, but to the institutions that house them.

Proponents of the PLRA range from prison officials to judges to attorneys. For example, the National Association of Attorneys General (NAAG) continue to be energetic supporters of the PLRA. Founded in 1907, the Association serves as a conduit between attorneys general, enhancing their job performance and efficacy. It also functions as a liaison to the federal government in areas such as criminal law, appellate advocacy and consumer protection. As mentioned earlier, their core values include dedication, integrity, collaboration, cooperation and inclusiveness (“National Association of Attorneys General.") Having championed the PLRA from its embryonic stages to its maturation, they laud it as a success for its capacity to distinguish between wasteful inmate claims versus legitimate human rights violations. Indeed, they stress that the aim of the PLRA is not to impede inmate filings, but to curtail the ballooning—and often-absurd—nature of prison litigation trends (Royal v. Kautzky 1). In establishing the "Three-strike" and "Administrative Exhaustion" dyad, they argue that the Act's purview is to maintain procedural efficiency, economization, and above all, judicial detachment (Hudson 22-29).

As stated previously, the 1960s and 70s were a pivotal era for state prisoners, with the Supreme Court recognizing their right to bring in claims under Section 1983. This led to a wave of inmate-filed federal suits highlighting issues with confinement, many of which were successfully remedied. In the wake of meaningful court access, greater protections and wide berth for procedural due process, the "hands-off" approach previously favored by courts fell to the wayside; under the aforementioned "Open Door Policy" (Coyle 52), the number of state prisoner civil rights lawsuits increased by 227%, shooting up from 12,397 in 1980 to 40,569 in 1995 (Branham 541). However, in conjunction with the swelling litigation arose complaints that prisoners were filing claims that lacked substance, that were based on malicious agendas, and that were detracting the attention of federal judges away from worthier litigants. In Scher v. Purkett (1991), a District Judge noted in the memorandum that the courts were becoming "vexed... with malcontent inmates who fill their idle time, and the Court's precious time, by filing § 1983 complaints about the petty deprivations inherent in prison life" (1). Similarly, the Indiana Law Review, in an article assessing the burdens of the federal docket, noted that "Many prisoners are interested in using the courts to achieve ends other than the adjudication of meritorious claims. Prisoners use the judicial system to harass prison and judicial officials by pursuing cases to the full limits of the law" (445).

Prior to the PLRA's passage, courts utilized a wide range of discretionary methods to handle the workload generated by such inmate suits. However, there was no overarching consensus that produced a workable solution to the issue. This was further exacerbated by the fact that inmates, with an inchoate understanding of legal procedures, were sometimes unsure of whether to label a specific issue as a Constitutional violation or simply an administrative grievance. To be sure, prison can be a restrictive and unsavory environment. However, a restrictive and unsavory environment is, in itself, not grounds for launching a dispute. Cases such as Estelle v Gamble (1976) and Brown v. Plata (2011) sought to illustrate (in an arguably contradictory fashion) what constituted cause for state action duties versus what did not (Simon 276-280). However, these rulings were not enough to establish a uniform threshold. Furthermore, the broad—and some have argued, porous—provisions of CRIPA could not filter out the meaningful inmate claims from the greater bulk of insubstantial ones. Subsequently, certain inmates with legitimate civil rights grievances would find their claims superseded by their vindictive counterparts, who filed merely for "entertainment value" (Greifinger 38-39; Hanson and Daley 3).

To that end, proponents of the PLRA argue that its "Administrative Exhaustion" stipulation proves invaluable. It allows for a standard framework to guide the otherwise convoluted mechanisms employed by courts to weed out meritless claims. In an interview, Leonard Peck, a former attorney for the TDCJ, notes that the exhaustion procedure is in place for inmates to "pin themselves down to an issue, and evaluate what its facts are." Given that a majority of inmate grievances are service-based requests, the Act allows prison administrators and inmates to be in accord about the problem, and decide whether or not it warrants action from the courts. Sarah Hart further argues that this mechanism alerts corrections managers to "problems that need to be addressed and allow[s]them to resolve disputes before they turn into Federal lawsuits" ("Subcommittee on Crime, Terrorism and Homeland..." 5). This encourages both efficacy and cost-effectiveness; inmate grievances can be promptly addressed without consuming time and money on the court docket.

In a similar vein, the PLRA's "Three-strike" standard is argued to be a safeguard against unnecessary financial expenditure. Given that meritless lawsuits impair the courts' ability to address more valid claims (prisoner-based and otherwise), the provision sets a standard intended to discourage frequent-filer inmates from wasting the courts' time. The second half of the "Three-strike" diptych is its in forma pauperis provision. This limits indigent filing after a prisoner’s claims have been dismissed three times, in which event the prisoner must pay over one hundred dollars when they re-file their claim to the courts. Proponents of the PLRA argue that there is no case-law guaranteeing prisoners the Constitutional right to be excused from payment of filing fees. More to the point, they claim that the provision is not a draconian countermeasure intended to curtail inmate rights. If anything, it offers great leeway in the choices offered to inmates, as it i) does not outright bar lawsuits, ii) does not apply to state actions, and iii) does not apply to exigent circumstances where the prisoner is in imminent danger of bodily harm. Viewed this way, the PLRA seeks to keep administrative powers with the prisons themselves, as opposed to outside parties. The benefits to this approach are twofold. Firstly, it allows prisons to understand the issues unique to their particular institutions, and to tailor penal policies accordingly. Secondly, it augurs a return to the 'hands-off' doctrine, allowing prisons to maintain their own security and order without judicial micromanagement (Hudson 22-30; "Subcommittee on Crime, Terrorism and Homeland..." 14-16).

The latter proves especially significant in examining the proponents' stance, since judicial oversight in prisons has long been considered anathema. Before the PLRA, cases such as Harris v. Fleming (1988) saw federal courts increasingly assuming the role not of impartial arbiters but of "busybodies" concerned with the day-to-day functioning of correctional institutions (Robertson 187-188). The Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals went so far as to state that, "Judges are not wardens, but we must act as wardens to the limited extent that unconstitutional prison conditions force us to intervene..." (Johnson 53). This observation made clear a troubling philosophy of judicial overreach. It called into question the role of the federal judiciary, which was accused of succumbing to "Lochnerization"—i.e. invalidating democratically enacted laws in the name of due process (Lochner v. New York n.p.). While disguised as an ennobling motive, it did not sit well with the majoritarian paradigm which cleaves law from policy. As far back as the 1930s, Associate Justice Felix Frankfurter had made clear that "courts are not representative bodies. They are not designed to be a good reflection of a democratic society ...We are to set aside the judgment of those whose duty it is to legislate only if there is no reasonable basis for it..." (Abraham 94). With that in mind, deference to the administrative state was long defined as a guiding principle in courts; their policies were not to be second-guessed via judicial meddling.

Pursuant to this principle, the PLRA seeks to limit the circumstances in which courts may intercede in prison policy on the inmates' behalf—be it through injunctions or consent decrees. In the past, both were roundly criticized for placing tiresome restrictions on the governance of prisons. Correctional managers complained that such measures interfered with their ability to use "ingenuity and initiative" in resolving issues unique to their prisons (Sullivan 430). Similarly, correctional administrations decried it as a means of undermining carceral authority and emboldening prisoners to disobey their keepers. Cases such as Cullum v. California Dep't of Corrections (1962) warned that "if every time a guard were called upon to maintain order he had to consider his possible tort liabilities it might unduly limit his actions" (Branham 482); while Golub v. Krimsky (1960) supported that "to allow such actions would be prejudicial to the proper maintenance of discipline" (Goldfarb and Singer 365). With these demerits in mind, the PLRA's enactment seeks to reassert the supremacy of federalism as a governing principle—for courts and corrections alike.

Certainly, with the passage of the PLRA, courts have resumed deferring to prison administrators. In a potent reminder of the power of institutional context, no recent legislation has been introduced to either change or repeal the Act. Indeed, it has been argued that the PLRA is the carceral "Iron triangle" writ large: a ternary rubric of prison autonomy, cost containment, and effective procedural channels for inmates (Adlerstein 1681-1685). At the same time, it stirs heated arguments among scholars and stakeholders, for whom the PLRA embodies the grim normalization of punishment and control. Far from allowing legal processes and civil liberties to keep apace one another, it widens the gap between them in a cruel rubicon against inmate rights. These critics, gaining volume as the PLRA enters its adulthood, are restarting the conversation on prison conditions, and challenging the policymaking flaws of the Act as a whole. Their stances will be summarily examined in the next section.

Stakeholders: The Opponents

Critics of the PLRA consist of judges, attorneys, academics and human rights organizations. At the helm of recent calls to dismantle the Act are the Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee (IWOC). Forming a coalition with Jailhouse Lawyers Speak—a network of prisoner rights advocates based out of South Carolina's Lee Correctional Institution—the IWOC have steadily worked towards improving the conditions of confinement within prisons, while also initiating large-scale dialogue and social awareness. The Committee strives to spark a "mass movement - inside and out - to abolish prison slavery." Their core values include emancipation, equal rights and community safety (Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee 1). On August 21, 2018, commemorating the death of activist George Jackson of the Black Panther party, the IWOC rallied together with inmates across 17 prisons to stage a three-week strike protesting inhumane prison conditions. The strike was spurred in part by a riot in South Carolina's Lee Correctional Institution—one of the deadliest in the past two decades. According to reports, seven inmates were killed, and twenty-two required hospitalization. Prison guards and EMTs, rather than interceding in the violence, simply looked the other way (FITSNews "Inmate On Inmate..." 1). The incident, according to the IWOC, is emblematic of deteriorating prison conditions nationwide, while its sparse media coverage marks a strategic suppression campaign by the Department of Corrections to prevent inmate narratives from reaching the public's ears.

Following the strike, inmates outlined ten demands, including better living conditions, the expansion of rehabilitative programming, and, most significantly, the rescission of the PLRA (Corbitt 1). The IWOC bolstered these demands by pointing out that however "civilly dead" prisoners may be, they are not exempt from certain Constitutional rights (Dubber 123). Most relevant are those afforded by the Eighth Amendment, which states that they must have basic needs met during their confinement—such as adequate sanitation, ventilation and medical care (Herman 1242-1245). The IWOC therefore holds the PLRA responsible for the degeneration of prison conditions, as it impedes inmates' from challenging them. Rife with "loopholes," and financially "taxing", it renders few other viable conduit for redress apart from protests. A jailhouse lawyer, under the pseudonym 'George', complains that, “You have to go through all these different steps, all these different mechanisms. By the time you hit the court, a lot of times the issue is moot... So you’ve lost your lawsuit altogether, and it’s not because your lawsuit doesn’t have merit" (Sonenstein 1).

Quoting Chief Justice Rehnquist's analogy of a prior deficient legislation ("...the watchdog did not bark that night"), Chief Judge Boyce Martin, a prominent critic of the PLRA, wryly noted that "When Congress penned the Prison Litigation Reform Act . . . the watchdog must have been dead" (Reid 566). Accordingly, opponents of the PLRA are wont to scrutinize it through a lens of Constitutional rights, fairness and efficacy. For them, the PLRA's "Exhaustion" and "Three-strike" provisions are two prongs of the same offensive: quashing prisoners' rights. They argue that, far from mitigating the federal workload, the PLRA has in fact generated more litigation revolving around its interpretive application. Worse, by redoubling the barriers already in place before prisoners can access courts, they reduce inmate claims to a zero-sum game. Prisoners cannot speak out and risk jeopardizing the prison's prerogative for autonomy; prisoners cannot remain silent and allow carceral administrations to function with impunity at the expense of their constitutional rights (Branham 493-498).

On the subject of prison grievance systems, a federal judge complained in a 2005 case, Campbell v. Chaves (2005), that they are often "a series of stalling tactics, and dead-ends without resolution" 1109). With that in mind, opponents of the PLRA state that, whatever the superficial gloss of legitimacy loaned to internal grievance mechanisms, their success is mere lip-service unless they achieve their intended goal. Unfortunately, their very set-up creates a conflict of interest. Prisoners who complain about abuses at the hands of staff must, in effect, enjoin the same staff to help them in submitting grievance forms. Such administrators would have the incentive to procedurally stymie a claim, regardless of its seriousness, thereby discouraging judicial intervention. Although the Supreme Court deems internal grievance mechanisms a "meaningful opportunity for prisoners," it fails to take into account that "those same officials have a self-serving interest in preventing the most meritorious claims from ever seeing the light of day" (Honick 178). This dilemma is highlighted by cases such as Sanders v. Bachus (2008) and Snyder v. Whittier (2009). In both instances, inmate-based complaints of excessive force were summarily dismissed for failure to exhaust, despite the plaintiff's explanations that they feared retaliation from the guards who assaulted them. More troubling still, according to the PLRA's opponents, is the fact that procedural defaults are no guarantor of impartiality. In Cleavinger v. Saxner (1985), the Court contended that the "relationship between the keeper and the kept... is hardly conducive to a truly adjudicatory performance" (Carmen 59).

Opponents of the PLRA argue that the very existence of the "Administrative Exhaustion" provision undermines this dictum. Rather, it serves as syllogism intended to "immunize" prison officials from accountability (Palmer 380). Objections are also raised about the hermetically sealed environment of prisons, within which a culture of reprisal reigns supreme. In such confined spaces, administrative exhaustion mechanisms can be wielded as tools for coercion, and may serve as a daunting maze for inmates with legitimate or even life-threatening issues. As Marissa C.M. Doran remarks, "American prisons are beset by... retaliation. In the prison context, this translates to a pattern in which officials punish prisoners who file grievances protesting the conditions of their confinement or exposing the behaviors of their jailors. (1028).

Equally problematic, according to the PLRA's opponents, are the lack of clear-cut definitions on what constitutes "administrative remedies... available" (Gullett 1189). Following the passage of the Act, a great deal of litigation was devoted to clarifying and delineating the term. However, between the resounding Congressional silence and the broadness of the phrase, courts found themselves split on its precise definition. For the Third, Sixth and Eleventh Circuits, it implied that exhaustion was mandatory even if the internal procedure did not result in a resolution of the issue. For the Fifth, Ninth and Tenth Circuit, however, the phrase seemed to denote the opposite (Doran 1045). It was not until the landmark ruling of Booth v. Churner (2001) did the Supreme Court rectify the split ("we think that Congress has mandated exhaustion clearly enough, regardless of the relief offered through administrative procedures" 1825). However, the decision also highlighted, for the PLRA's critics, the amorphous, and conversely, ministerial, nature of its provisions. Worse, they contend that despite the definitions laid out by the Supreme Court, the Act continues to consume judicial resources. Due to the compulsory exhaustion requirement, inquiries must be made as to whether or not internal procedures were fulfilled, rather than the case being handled on its own merits. More tiresome still, they argue, is that upon failure to first exhaust all available administrative remedies, the case must be dismissed and re-filed, thereby wasting valuable judicial resources (Slutsky 2320).

An equally strident criticism deals with the Act's "Three-strike" provision. As mentioned, this stipulation is intended to ensure that once an inmate has had three civil cases dismissed by a court, he or she cannot claim indigent status and have the filing fees waived in future cases. Opponents argue that this is tantamount to stonewalling inmates out of courts, given the meager income of most, and the fact that the filing fee in federal courts is $400. More pertinently, they deride the language of the provision as rhetorical smokescreen. While the PLRA states that "an action or appeal" denotes a strike, circuit courts have since expanded its meaning to each stage of the judicial process. This implies that an inmate's claim can accrue a strike at three stages—in trial court, in the appeals court, in the Supreme Court—despite only having a single case. The PLRA's use of the term "frivolous" has also come under sharp criticism from opponents. A number of scholars have attempted to deconstruct the 'frivolity' of inmate claims: its semiotics and semantics alike. An equal number of attorneys and judges have endeavored to understand frivolity in conjunction to the Act's "strike" zone. On the whole, opponents argue that its application has been overly aggressive in courts (Puritz and Scali 86-88). Cases such as Gonzales v. Wyatt (1998) highlight how closely inmates must adhere to the PLRA's rules, lest their case be struck down. In this particular case, having filed an excessive force lawsuit with the assistance of another inmate, the plaintiff was transferred to a different prison and his legal paperwork confiscated. His friend filed an unsigned copy of the suit on his behalf, in tandem with a signed copy of his own. However, the court designated the suit as frivolous, not on the basis that it was meritless, but due to failure to submit a signed copy by the deadline (1021). Critics argue that tossing out cases on the basis of technical errors does not deter frivolous lawsuits, but all lawsuits in their entirety.

Indeed, the predominant criticism of the PLRA deals, at its crux, with its Constitutional undermining. Opponents point out that, far from adhering to the safeguards of a civilized society, the PLRA eviscerates the most fundamental Constitutional right afforded to inmates. By severely limiting their channels for meaningful redress, it deprives them of pivotal rights such as due process, open access and petitioning. The latter is especially vital, given that petitioning arose as means of mutual information-flow between individuals and the government. Historically, it holds the capacity to grant both individual relief and structural remedies. In eighteenth-century Virginia, for instance, a majority of the bills enacted by the state legislature arose as petitions (Bailey 200). Similarly, modern-day petitions function as "a vehicle for effective political expression and association, as well as a means of communicating useful information to the public" (Borough of Duryea, et al. v. Guarnieri 16). As such, the freedom to petition, especially in total institutions such as prisons, is necessary not just for structural vitality but as an outpost of democracy. It "enhance[s] the integrity and quality" of conditions within correctional systems (Richmond Newspapers, Inc. v. Virginia 580-81). Opponents argue that the PLRA effectively compromises this necessary exchange between public and private realms, enshrouding unsound—and unconstitutional—prison policies within a red tape of balancing tests.

To date, no attempts to repeal the PLRA have been successful. This is certainly not for lack of trying. In 2007, the American Bar Association's Criminal Justice Section urged Congress in a report to "repeal or amend specified portions" of the Act. It also requested that the Act's provisions be re-examined for the broadness of their scope, and their hindrance in sifting meritorious from non-meritorious legal claims ("CRIMINAL JUSTICE SECTION Report to the HOUSE OF DELEGATES" 3-13). However, as Kermit Roosevelt notes, "the statute has survived judicial scrutiny essentially unchanged" (1805). This has not, however, deterred organizations and inmates from taking a stand against the more repressive aspects of the Act. The IWOC, for instance, continues to be actively instrumental in developing movement organizations both inside and outside prison walls. In addition to endorsing nationwide prison strikes, and offering them a platform to lay out their demands, the organization has started up call-in campaigns, or 'phone zaps,' intended to increase public pressure into prisons. “From past strikes," an activist explains, “what we did learn is that from the outside, the more people that tend to stand up, demonstrate from the outside, particularly demos at the prisons, what it does is it incites. It incites inside and this is why prisons have a problem against it" (Losier 1). That said, there is no denying that momentum for such a movement will be slow-going, if not outright impossible. As mentioned, prisoners constitute an invisible segment of society. Neither beloved nor popular, their plight will invariably be subsumed by more noticeable issues on the outside. However, as opponents of the PLRA note, this makes it doubly pertinent to dismantle the Act, the better to initiate a dialogue, and understand the shadowy flipside of what occurs in society's name behind "steel doors and concrete walls" (Daly 230).

Analysis of Arguments: Merits

Both the proponents and opponents of the PLRA raise valid arguments. However, it is pertinent to examine these arguments through their accompanying political optics. In terms of doctrine and practice, both sides have widely conflicting interpretations of the Act—a polarization stemming as much from dialecticism as empiricism. For its proponents, the PLRA is intended to rectify the dangerous slip-slide towards interventionism by the post-Civil Rights era courts. For its opponents, it is an administrative quagmire, within which the intersecting rights of due process and open access are unconstitutionally curbed. Hand-in-hand with this "war of extremes" are heavily politicized attacks lobbed by either side of the aisle, with each party attempting to shape the narrative of prisoners' rights (Schlanger 1569). This is not to say that either side's viewpoints are asinine. Far from it; the lens of their analysis proves extremely instructive, revealing a shared interest in streamlining the mechanisms for inmate litigation and ensuring that adequate avenues are in place before and after a federal claim is initiated. Where they differ is in how they view the content inmates bring to court: frivolity versus civil rights violations. Thus, when going about an analysis of their argumentation, it is essential to disengage the political 'spin' from the factual basis.

Having carefully weighed the supporting evidence on both sides, this writer admits that the proponents of the PLRA offer a persuasive range of viewpoints. Values such as dedication, integrity, collaboration, cooperation and inclusiveness may seem at odds with more pragmatic goals such as procedural efficiency, economization, and judicial detachment. However, these goals need not be conflated with short-sighted agendas or crude instrumentalism. Far from it, when interwoven with the NAAG's core values, the PLRA exemplifies a careful grounding of institutional and structural enhancement, and a deliberate balancing of the means-ends rationale. For instance, with its "Administrative Exhaustion" provision, the Act has succeeded in preventing courts from being crippled by groundless claims—while simultaneously allowing inmates access to alternate grievance avenues within the prison itself. The focus is not on blocking inmate suits in their entirety. Rather, it is on assessing their legal sufficiency. Margo Schlanger, despite being one of the most strident critics of the PLRA, has acknowledged that prisoner litigation is, "absolutely speaking, quite low in 'merit'" (1599). Similarly, legal commentator Eugene J. Kuzinski has written that, while not all inmate claims are invalid, "the problem is that meritorious claims are the exception, rather than the rule" (364).

Bolstering this is data indicating that, from 1990 to 1995, eighty-two percent of inmate cases resulted in unsuccessful pretrial judgement for inmates ("The Indeterminacy of Inmate Litigation..." 1670). While critics of the PLRA cry foul about inmate suits being caricatured as little more than squabbles over peanut butter, the fact remains that a majority of suits indeed fall short of the acceptable legal standard for merit. More to the point, their flimsiness is not the focus, so much as the larger phenomenon of excessive inmate litigation they represent. In floor speeches preceding the PLRA's passage, Senator Reid, for example, decried that "notwithstanding the odds against prevailing, inmates continue to file suits" ("Congressional Record..." 27043). Similarly, Senator Kyl bemoaned the tendency of inmates to "[file] free lawsuits in response to almost any perceived slight" regardless of "their legal merit" (Quirk 275). The "Administrative Exhaustion" provision, therefore, has less to do with barring laughable inmate claims in their entirety, than in nipping low-merit cases in the bud. This proves beneficial for both parties, as prison officials can deal with an issue swiftly and efficiently, rather than allowing it to ripen into a lengthy (and oftentimes desultory) lawsuit. For critics to therefore make a subjective pounce on administrative remedies as arm-twisting rather than as interpretive conflict, seems a touch hyperbolic.

Much is also made about how the Act's "Three-Strike" safeguard. Critics claim it imposes impossibly "high hurdles" for prisoners to access courts ("The Indeterminacy..." 1671). However, this too proves to be a largely semantic rather than a doctrinal tug-of-war. Firstly, where opponents of the PLRA weigh frivolity according to its ability to make inmates' lives more difficult in confinement, supporters of the PLRA are more interested in contemporary legal thresholds. Secondly, not enough attention is devoted to understanding the divergent definitions of 'frivolity' both within and beyond correctional institutions. Given that the prisoner's world is limited to the four walls of the prison, their idea of 'serious issues' is markedly different from a non-prisoner's. As such, "[w]hat to most people would be a very insignificant [matter] becomes, because of the nature of prison life, a matter of real concern to the inmate" (Jacobs 203). This is, however, not enough qualify a claim as worthy of the federal court's attention. Indeed, when measuring the low success rates of inmate claims by legal standards as opposed to politicized ideals, there is no denying that inmate litigation is too insufficient in content to withstand court review. While it can be argued that the definition of frivolity is subject to court interpretation, this alone is no basis for designating the Act a failure. U.S law is, at its crux, interpretive in nature (Hunter 99). As such, the PLRA cannot be demonized each time judges establish too-high or too-low thresholds for lawsuit meritoriousness. While opponents may contend that frivolity is wielded as a repressive hammer by conservative courts, such an argument is "inherently political rather than empirical" ("The Indeterminacy..." 1671).

Certainly, in terms of straightforward execution, the PLRA has fulfilled its role in unburdening the federal docket. There is no arguing that since its passage, the volume of inmate litigation has slimmed down remarkably. Between 1995 (prior to the Act) and 2000, the amount of civil rights suits dropped by forty percent, from 41,679 to 25,504. Similarly, the filing rate (measured as per one thousand inmates) declined from thirty-seven to nineteen (Scalia 1-8). With that in mind, "to the extent that success can be measured by the volume of suits, the PLRA has worked .... [The] substantial decrease ... is all the more impressive when considered in light of the growing prison population" (Roosevelt 1779-80). To add to that, Margo Schlanger has admitted that, prior to the PLRA, there was credible proof that high case volumes prevented courts from screening solid claims: "It is difficult to see how judges could adequately process so many non-settling cases in so little time" (1590). Citing New York Assistant Attorney General Alan Kaufman's interview with the Times ("It's a struggle not to throw out the baby with the bath water"), she further remarks that the PLRA has had an undeniable effect on each aspect of the inmate docket (Dunn 1). From state courts, to habeas petitions, to jail and prison filings, courts are processing a "reduced caseload" with more speediness (Schlanger 1643). The Bureau of Justice Statistics, reporting a five-year study about inmate-filing trends, reached similar findings, noting that from most respects, the Act was a "success" (Hudson 25).

From a federalist standpoint, the PLRA has succeeded too, in allowing the courts and corrections systems to function side-by-side without impinging on each other’s territories. With its "Three-Strike" provisions, it has promulgated guidelines for what claims may reach the court docket, versus which ones may be dismissed from the outset. This enables both corrections departments and courts to establish an initial burden that inmates must meet. Similarly, with its "Administrative Exhaustion" prong, it delineates mechanisms within the prison for when inmates have an issue—and whether it warrants attention beyond the prison walls. While the boundaries between the judicial and legislative branch are not "hermetically sealed," the Act thus prevents the two spheres from infringing on each other’s' functional prerogatives (Buckley v. Valeo). As such, the PLRA succeeds in two counts of its intended purposes: keeping federal dockets unburdened while simultaneously preventing the judiciary from appropriating control of the state correctional system. As Justice Clarence Thomas makes clear, "State prisons should be run by the state officials with the expertise and the primary authority for running such institutions. Absent the most extraordinary circumstances, federal courts should refrain from meddling in such affairs. Prison administrators have a difficult enough job without federal court intervention" (Carlson 522).

Certainly, the fact that the PLRA continues to stand strong, two decades after its passage, seems a testament to its general applicability. Broad enough for corrections systems to apply it flexibly but specific enough for individual prisons to use it as an underlying framework, it remains the go-to statute for corrections administrators to outline their internal and external mechanisms on prisoner suits. Given its empirical successes, it is difficult to dismiss the Act as the most inefficient extreme of carceral logic. If anything, its legislative history makes clear that it was meant to sift through the morass of inmate suits "clogging" the Federal court docket, so that resources could rightfully be allocated to meritorious litigation (Hudson 22).

Analysis of Arguments: Demerits

Unfortunately, the fulfillment of these goals cannot eclipse the unsavory undercurrents surrounding the PLRA's passage. The road to its evolution was shaped as much by a voluble anti-inmate platform as by the tough-on-crime social tenor that characterized the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s. Criminal justice became a vibrant talking point by 1968, when Republican challenger Richard Nixon decried the burgeoning crime rate as the direct offshoot of the Warren Court's lax liberalism, wherein the rights of defendants appeared to be disproportionately favored in criminal cases. The solution to this crisis was to "reestablish the principle that men are accountable for what they do" (Marion 522). Harsher law enforcement and more punitive sentencing would become a critical facet of the elections, both then, and thereafter. In the 1980s, Ronald Reagan would emulate Nixon's stance, conflating the "crime issue" with liberal failing. Advocating for harsher mandatory sentencing programs and greater use of the death penalty, Reagan's election victory marked the "enduring power of criminal justice as an emotive issue, and its strong correlation to the success of candidates for national office" (Sullivan 427).

To be sure, there was an uptick of crime from the 1970s to 1990s. Several pundits posit that this led to correspondingly high incarceration rates. However, there is scant data to support this theory. Rather, research suggests that politics play a far stronger role in punishment trends—not just in the United States but several Western Democratic countries. Although the rate and severity of a crime may contribute to the initial design of sentencing structures, a greater influence still is exerted by the policy decisions of public officials (Tonry 519-524). Certainly, the spike in prison populations across the UK, the Netherlands, and in particular the United States, was the result of politicians' rallying outcry to get 'tough on crime.' This in turn cultivated an atmosphere of penal populism—a term for criminal justice policies that satisfy the public but fail to consider overall effectiveness and community views (Pratt 194). With ideological hallmarks such as the War on Drugs and Zero Tolerance Policing defining the era, the criminal justice system would see itself revamped as the vanguard of safety and security—arguably at the cost of redlining communities of color (Lusane and Desmond 25-53).

The Democratic Party, not blind to this formula, echoed Republican calls for stricter laws during the Clinton era. What followed was the steady normalization of longer sentences and less diversionary programming. As mass incarceration skyrocketed, prison overcrowding and deteriorating conditions—best cataloged in Brown v. Plata (2011)—would see sanitation and essential resources so reduced that the prison facilities constituted little better than "cruel and unusual punishment" (2-18). Far from resigning themselves to the squalor, inmates filed a swelling number of suits in federal court. Indeed, by the 1990s, "state prisoners challenging the conditions of their confinement accounted for the single largest category of civil lawsuits filed in U.S. district courts." In 1996 alone, prisoners brought forward about 41302 lawsuits (Ostrom et al. 1525). While organizations such as the NAAG were quick to dismiss these claims as toothless (as evidenced by their list of Top Ten Prisoner Suits) the fact remains that reports of abuse against prisoners "...were neither infrequent nor geographically limited (Mathews 537)."

Indeed, regardless of the meritless nature of inmate suits, their underlying seriousness was tragically mischaracterized. Professor Kermit Roosevelt notes that, while inmate suits may be frivolous, the ones distributed by the media at the behest of the NAAG were anything but. Rather, the very perception of the "frivolous" inmate lawsuit was sparked by a smear-campaign spearheaded by congressional officials and state attorneys general (1771-1776). The paradigmatic inmate lawsuit, wherein a prisoner was upset over the substitution of creamy peanut butter with chunky, best exemplifies the propaganda. As Judge Jon O. Newman notes:

...The prisoner did not sue because he received the wrong kind of peanut butter. He sued because the prison had incorrectly debited his prison account $2.50 under the following circumstances. He had ordered two jars of peanut butter; one sent by the canteen was the wrong kind, and a guard had quite willingly taken back the wrong product and assured the prisoner that the item he had ordered and paid for would be sent the next day. Unfortunately, the authorities transferred the prisoner that night to another prison, and his prison account remained charged $2.50 for the item that he had ordered but had never received (521).

Similar suits, touted by the NAAG as typical of the inmate docket, reveal the unfair myths perpetuated about prisoners. In what the ACLU refers to as a time "when state and federal lawmakers were enacting restrictions on prisoner rights," the PLRA seems to have emerged less on the basis of careful research than on snide anecdotalism ("Top Ten Non-Frivolous Lawsuits..." 1). While undeniably successful at trimming down an overgrown court docket, the rudimentary jurisprudence that went into its creation cannot be ignored. If anything, it comes off largely as a reactionary backlash against inmate rights. More disquieting still is the legislative strong-arming that led to the Act's enactment. While preliminary data suggests that the Act passed, as mentioned, "with strong bipartisan support" — closer examination tells a different story (Ostrom et al. 1536). As it turns out, the support that the PLRA garnered was based less on transparency than on dissimulation. Packaged as an appropriations bill rider, the Act was buried beneath other bills and did not receive the same attention it would have warranted as a standalone. Indeed, the PLRA's passage appears to have been rooted in "fiscal exigency" rather than "sound policy" (Sullivan 433). Disguised as the unreadable "fine print" rather than the centerpiece for legislative attention, the Act received only a perfunctory review—an action that is directly in violation of the deliberative process laid out in Article I of the Constitution (Branham 538). As such, the PLRA's provisions do not receive the robust debate due to such a sweeping piece of legislation. Such dubious beginnings make it difficult to accept the PLRA as foolproof. As Kyle Sullivan notes, "...a primary criticism of the PLRA is not that it is bad law, but that it is not law in the truest sense. Legislation-by-misdirection ...undermines the spirit of the Constitution and, in the case of the PLRA, facilitates violation of prisoners’ Eighth Amendment rights" (433-434).

Indeed, the First, Fifth, Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments prove the most tendentious pivot upon which the PLRA's legitimacy rests. Although the Act's "Administrative Exhaustion" and "Three-strike" safeguards were promulgated to reduce the judicial workload, the fact remains that by establishing thresholds for "frivolity" in different aspects of prison life, the Act reduces the Eighth Amendment from an indomitable fact to a sidebar with a broad "margin for toleration. By curtailing such a critical Constitutional right, the PLRA not only allows prison abuses to abound unchecked, but functions as a grim "self-fulfilling prophecy" (Sullivan 434). Brimful with the language of restriction, it instills in prison administrators the idea that its stipulations not only work to suppress inmate complaints, but allow their own duties to fall below the Constitutional barometer of acceptability. The PLRA also creates a troubling dichotomy in the Equal Protection clause of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments. A report published by the Human Rights' Watch (HRW) illustrates how the Act creates a "separate but unequal" legal framework by hectoring only the lawsuits brought by inmates. The HRW further add that they are currently "not aware of any other country in which national legislation singles out prisoners for a unique set of barriers and obstacles to vindicating their legal rights in court" (Fathi 47).

No matter the insubstantial nature of inmate litigation, the fact remains that prisoners are a highly powerless faction of society. Viewed with almost universal distrust, their claims are often written off before they even reach court. Prisoners must contend with a plethora of generic barriers: under-resourced and underpaid counsel; impediments to access for individuals with mental disabilities; time constraints; sparse avenues for alternative dispute resolution (Calavita and Jenness 10-148). In addition, prisoner civil rights claims are hampered by a deferential standard—both du jure and de facto—established in Turner v. Safely (1987). This prevents court officials from subjecting prisons to "an inflexible, strict scrutiny analysis" on the rationale that it would hinder the day-to-day operations of the institution (1). The PLRA, by introducing another layer of opacity into the functioning of prisons, therefore deprives prisoners of the most effective remedy that isn't confined to the prison's internal operations. Worse, by blocking both individual and collective rights, and corraling them strictly to the "Administrative Exhaustion" mandates, prisoners are left vulnerable to retaliation from prison officials. Given that many administrative measures are "hyper-technical" and intricate enough to discombobulate even the most seasoned attorney, the PLRA "severely inhibit[s] prisoners' abilities to protect themselves from the crimes it commits against them" (Ross 28).

Finally, through the lens of the First Amendment, the PLRA invalidates not only the interests of the individual, but those of the state. By obstructing prisoners' access to the courts, it diminishes the communicative power of lawsuits to air not only personal grievances, but to fulfill their "information function" for the outside world (Doran 1061). This esteem for petitioning is not a philosophical, but a Constitutional right. Justice Blackmun once noted that, for individuals who are convicted, the right to "file a court action stands ...as his most ‘fundamental political right, because [it is] preservative of all rights'" (Palmer 169). Thus, if inmate litigation is based on merit, the right to access the courts becomes doubly germane as it can be used to address constitutional violations. The PLRA interferes with this right on a two-fold level: first by blocking the protections enshrined in the Petition Clause, and secondly by denying the public access to information within penal systems in their entirety (Borough of Duryea, et al. v. Guarnieri 2495). Worse, by treating free speech and petitioning as theoretically proximate, rather than distinct, it stymies prisoner's voices within bureaucratic mechanisms meant for internal communication.

When taking all the aspects of the PLRA into consideration, this writer concedes that while the Act has benefits, these are subsumed by its drawbacks. However assertive the stance of its proponents, the fact remains that the PLRA has the dark potential to transform prisons into brutal fiefdoms unto themselves. What's more, in the long-term, its goals of cost-cutting, efficiency and independence will not be reached—not if it is at the expense of running transparent and accountable corrections systems. Instead, devoid of oversight to dispense so much as a slap on the wrist to prison administrators, the Act reduces prisoners to their earliest status of "slaves of the state" (Ruffin v Commonwealth 1). The values of dedication, integrity, collaboration, cooperation and inclusiveness espoused by the NAAG cannot be reconciled to such an autocratic framework.

The stance taken by the PLRA's opponents, therefore, outweighs that of its proponents. Championing to dismantle the Act, organizations such as IWOC are more closely aligned with the values of emancipation, equal rights and community safety (Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee 1) as compared to the NAAG. Whatever one's political disagreements over the meaning of lawsuit frivolity, the fact remains that the PLRA creates a dichotomy by measuring the needs of the prisoner against those of the courts. In due process terms, it suggests that the government is not unitary, but a tricky balancing act wherein the judiciary and the executive are engaged in a tug-of-war. More disturbingly, the Act suggests that superficial efficiency among the courts serves as a vindication for eroding inmates' Constitutional rights. No culling of the court docket or cost-cutting of the federal judiciary can justify this stance. Prisoner petitions may oftentimes lack in merit. But they symbolize more than a complaint of distasteful prison conditions. They are a means of communication to the courts—and the outside world at large. More to the point, they are petitions, which signify "constitutional concerns," acting as a forum for the "preservation of rights." Such petitions do not belong in the realm of the "managerial" but in the context of governance. They support "competing values and expectations" as a hallmark of public negotiation (Doran 1069-1083). The "Three-strike" and "Exhaustion" mandates of the PLRA are stifling these petitions. As Robert L. Tsai notes,

The inmate, a classic 'deviant' whom the modern state separates, isolates, and controls absolutely, must seek relief from non-traditional quarters. Even more so than other political minorities for whom some measure of progress has been made in improving accountability and influence, the courts remain for these despised individuals "the sole practical avenue open to ... petition for redress of grievances (896).

Ostensibly, the PLRA operates to clear the clutter of federal dockets. However, it also deprives prisoners of a humane remedy—or indeed, any remedy at all—for violations of their rights. Such a framework cannot be beneficial in the long term, for courts or corrections alike. When it comes to civil rights violations, the adage of 'out of sight out of mind' will not do. Sweeping inmate lawsuits aside will not make prison abuses go away. If anything, embittered prisoners will be more likely lash out with violence. The incident at South Carolina's Lee Correctional Institution stands as testament to this fact. Allowing prisoners a channel to air their grievances, therefore, is cathartic as well as cost-effective. It may allow for a maintenance of order and compliance within prisons, and preclude explosive—and potentially expensive—acts of rebellion from taking place.

Moral Reasoning

Taken together, this writer contends that the "Three-Strike" and "Administrative Exhaustion" prongs of the PLRA should be struck down. Indeed, the PLRA should be rescinded in its entirety. The writer holds dear the values of equality and transparency. More to the point, she cherishes the Kantian tenets of universal human rights and a moral basis behind each action. The PLRA, upon careful examination, fails to deliver these values. Far from it, it strains the precepts of the Constitution. It reduces the steadfastness of the Eighth Amendment, sidelines the enumerated due process rights of the Fifth and Fourteenth, and undermines the First into a residue of speech rather than a "reasonable right of access to the courts" (Hudson v. Palmer 1). From a Kantian standpoint, such a legislation cannot stand. Arisen from dubious legality and cruel misconceptions of inmates, the Act cannot fulfill its intended purpose without trampling the welfare of the vulnerable. Certainly, the Act has played its part in reducing the number of meritless inmate claims in the court docket. But it has done so at the expense of exposing grave prison abuses. Proponents of the PLRA may argue that the restriction of these suits is intended to serve a cost-effective solution. However, Kant rejects such a Utilitarian principle wherein the end justifies the means (i.e. the greatest happiness for the highest number). For him, such a calculation reduces personhood, and redefines justice as a mechanism to maximize welfare simply for those with the loudest voice. More troubling still, it attempts to derive moral vindication from mere empirical consideration (Banks 10-120).

For Kant, respect for human dignity is paramount. Rather than morality being contingent on interests and desires—which are variable from moment to moment—he argues that each person is worthy of respect, not because of their utility, but because they are rational beings, capable of thought and free choice. With that in mind, the PLRA fails emphatically at recognizing prisoners as people. By curbing their right for legal redress, it denies them the freedom of self-expression. Conversely, by denying the public access to the goings-on within prisons, it diminishes the utility of prisons themselves in the long term. It treats both parties as instruments whose goals should not intersect for the sake of general welfare—creating a legally enforced dichotomy of worthy and unworthy, enslaved and free. As Kristian Cedervall Lauta notes, the legitimization of such a framework gives birth to a "shadow system" where "security is the raison d'etat" (68). This echoes eerily with Supreme Court Justice William Brennan's metaphor of the prison environment as a "shadow world" (Schmalleger and Atkin-Plunk 102; O‘Lone v. Estate of Shabazz 354-55). It also drives home the concept of a state divided into two spheres: "Normal constitutional conduct, inhabited by law, universal rules and reasoned discourse; and a realm where universal rules are inadequate to meet the particular emergency situation and where law must be replaced by discretion and politics" (Lobel 1390)

In the latter sphere, the prisoner is reduced to an object whose erasure is necessary for the happiness of others. Persons within such a system exist, not for their own sake, but as widgets to fulfill a politicized agenda. For Kant, this is sorely lacking in moral worth. As he notes, each action comprises not of its consequences, but the intentions from which the act springs forth. Motive is more critical than means, and the former must have redemptive value. As he writes, "A good will is not good because of what it effects or accomplishes. It is good in itself, whether or not it prevails... it would still shine like a jewel for its own sake as something which has its full value in itself" (Sandel 111). When scrutinizing the PLRA through this lens, it fails once more to meet the Kantian threshold. The origins of the Act were suffused with legal subterfuge, the language for its support imbued with a deep-rooted contempt for prisoners. This questionable subtext makes it difficult to reconcile oneself to the PLRA's presentation as a balanced protector of both court interests and inmate rights. If anything, it appears disproportionately to favor the former over the latter. For Kant, motives such as these—referred to as "motives of inclination"—clash with the motive of duty. As he states, only actions done out of the motive of duty possess moral worth (Bird 237).

Proposed Solution

The problems posed by the PLRA—ethical, legislative, political—cannot be remedied overnight. To be sure, the Act must be repealed. However, regardless of whether it remains or goes, there must be alternative methods in place to guarantee prisoner welfare. The solution, then, is to re-introduce a measure of transparency into prison systems, without impinging on the independence of the executive and the judiciary. A body of correctional oversight—detached from both—appears the most feasible solution. I base this conclusion as much on my own research, as on my interviews with two individuals most suited to identifying the potential merits and demerits of correctional oversight. The first is Professor Michele Deitch, senior lecturer at the University of Texas Austin. An attorney with over thirty years of experience in the arenas of criminal justice, corrections and juvenile justice policy issues, she has published a number of works about mechanisms for prison oversight, as well as developing a fifty-state inventory of prison oversight models. She has also served as a federal court-appointed monitor of conditions in the Texas prison system. According to Prof. Deitch, oversight is not a one-size-fits-all strategy, but an "umbrella" concept entailing at least six vital functions: regulations, audit, accreditation, investigation, reporting, and inspection. Each of these, successfully combined together, contribute the overall objective of a transparent carceral system (1696).

The second individual, echoing Prof. Deitch's stance, is Dr. Leonard Peck. Currently an assistant professor of Criminal Justice and Sociology at Texas A & M University, Dr. Peck spent several years prior to entering academia with the TDCJ General Council's office. Having gained extensive experience in institutional corrections and prison population trends, Dr. Peck believes it is imperative to have a system in place that supplements, if not outright replaces, litigation as an inmate redress vehicle. As he makes clear, the frivolity of inmate suits tends to drown out the more serious cases, "What happens is that these guys generate enough trash that they aggravate judges. So every now and then, when someone's really been wronged, the judges—because they've been burned by so many jerks—lose track of the guy who was really injured" (Draper 55). Although, as opposed to Prof. Deitch, Dr. Peck believes the PLRA exists as a safety valve to keep federal courts unencumbered, he also believes that additional prison monitoring bodies could certainly be useful in alleviating the inmates' over-reliance on the judiciary.

To be sure, greater transparency in carceral systems is essential for prisoners' rights, and the welfare of the prison institution itself. In 2006, a conference sponsored by the Lyndon B. Johnson School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas, in conjunction with Pace Law School, invited numerous scholars on corrections policy to Austin, Texas. Their aim, as aptly stated by the conference's title—Opening Up a Closed World: What Constitutes Effective Prison Oversight?—was intended to explore multi-faceted mechanisms for inspecting prisons (Mushlin and Deitch 1383). One of the academics at the conference, Professor Stan Stojkovic, was quick to demonstrate how prison oversight can prove beneficial from both an administrative and Constitutional standpoint. In his work, titled Prison Oversight and Prison Leadership, he explains how prison oversight aligns with democratic values: "The prison is, for the most part, a public concern and requires public oversight... The objective is transparency, nothing more, nothing less. The essence of democracy is that sunlight can get into institutional settings, especially those that have a history of being hidden. Operating from a position of transparency, prisons are seen with all their faults" (1478). Reiterating this assertion, the American Bar Association (ABA) passed a resolution in 2008, urging the government at multiple levels to establish public monitoring entities to discern the conditions of detention facilities. Detailing how external oversight is not only cost-effective but advantageous for future sentencing and correctional policies, the ABA states that courts cannot solely be relied on for enforcing the necessary standards of humane treatment. Rather, an independent and neutral entity can more effectively fill in the judicial vacuum, providing regular monitoring that not only addresses civil rights abuses, but circumvents them before prison conditions deteriorate to the point where they occur (Mushlin 246).