#Gloria Anzaldúa

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Who is Gloria Anzaldúa?: A review of a Revolutionary Women

This is a somewhat academic research essay about Gloria Anzaldúa and her impact on the queer Chicana Identity. If you are unfamiliar with her work and you are a queer Chicana, it's like waking up. A professor once told me that reading Anzaldúa for the first time is like taking the Red pill. It's confronting a part of yourself that society has conditioned you to quiet. If this something doesn't fully resonate with you, that's okay. Read and learn from someone with a different perspective anyway. As Chicano Studies will stress, Connection is fundamental to growth and healing. I am always open to critique and edits. Feel free to DM me with questions/concerns/or even edits. My goal is to build a connection with those within this space!

The day I was assigned Borderlands/La Frontera by Gloria Anzaldúa was my first encounter with the true nature of my cultural heritage. It was my first year at Texas State, 558 miles from El Paso, Texas, the borderland I called home. At that time, my goal was to go to law school, work as an attorney, maybe run for office, and eventually become a Judge; I was to be the Perfect Mexican Daughter. Borderlands was a transformative read. It was the story of the border, my home, and my life. Anzaldúa writes, “1,950-mile-long open wound dividing a pueblo, a culture, running down my body, staking fence rods in my flesh, splits me, splits me, me raja, me raja.” [1]Living on the U.S.-Mexico Border, being Mexican, you grew up with a tear in your soul, the likes of which you were conditioned to ignore. Subsequently, this societal-imposed ignorance breeds resentment, anger, and conformity. It is the pressure to assimilate. It's important to understand that the goal of assimilation is to distance yourself from yourself. This distance, for me at least, was painful.

Reading Anzaldúa for the first time made me realize I had a choice. For me and so many, Anzaldúa served as the bridge between assimilation and decolonization. Meaning she presented a world in which my pain could be transfigured into the reclamation of my identity. Through her philosophical and historical narrative, Anzaldúa gave us a path to reconnecting. Reading Borderlands and discovering my Chicana/Latina and Indigenous roots put me on the path to reconnection; it made the grip that assimilation once had on me gradually loosen. I could breathe, write, and create and connect with my identity. Therefore, this essay aims to provide a context of the historical and social importance of the revolutionary work of Gloria Anzaldúa's work.

Seeing that Anzaldúa primarily writes about the effects of a political border like the US-Mexico border on culture, I believe it is important to understand the historical context of border relations between the United States and Mexico when Anzaldúa was writing. Anzaldúa published most of her works between 1981 and 1996, while her last work would be published after she died in 2015. Therefore, I will primarily focus on the border relations between the U.S. and Mexico in the 80s and 90s. Historian Douglas Massey points out, “Although the Mexico-U.S. border has long been deployed as a symbolic line of defense against foreign threats, its prominence in the American imagination has ebbed and flowed over time. Over the past several decades, however, the political and emotional importance of the border as a symbolic battle line has risen.” [2]Massey points out that the idea of a US-Mexico border as a physical and metaphysical construct that divides is a fairly recent concept. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, U.S., Texas, and Mexico relations were inconsistent fluctuations, leading to an ever-changing physical border. Massey writes, “In theory, the Mexico-U.S. border first came into existence with Mexico's achievement of independence from Spain in 1821, although very quickly the border was blurred by the entry of U.S. settlers into northern Mexico from southern and border states in the United States.” (161) Which leads us into the 20th century. Where the border is now effectively militarized, and there are increasingly anti-immigration sentiments that have been pervasive throughout history and perpetuated through the militarization of the physical US-Mexico border. “A systematic coding of weekly U.S. news magazine covers dealing with immigration from 1970 to 2000 found that negatively framed covers increased markedly in frequency through the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. Migration from south of the border was increasingly referred to as a "crisis" and was labeled either a "flood" that would "inundate" the United States and "drown" its society or an "invasion" of hostile "aliens" pitted against "outgunned" Border Patrol agents who sought to "hold the line" against "banzai charges" by migrants who would "overrun" American society.” [3](168) This was the tumultuous time when Anzaldúa became prominent in her academic career. It was important to her that within her works, she addressed the systematic failings that caused this racist climate. In Borderlands/La Frontera, Anzaldúa says: “Those who make it past the checking points of the Border Patrol find themselves in the midst of 150 years of racism in Chicano barrios in the Southwest and in big northern cities (37).” Within the context of the time, simply acknowledging the tyrannical effects of the physical US-Mexican border revolutionized the way Chicanos interacted with border ideology. By highlighting this systemic racism within the physical and metaphysical U.S.- Mexico border, Anzaldúa highlighted the pain that Mexicans Chicanos felt living with the hostility that came from being a borderland person.

Moreover, within the historical context of the 80s and 90s, Anzaldúa faced a great challenge when it came to her queer identity. Within Borderlands, not only does A write about the struggles of a border identity, but she also writes about the struggles of queerness and gender and how that itself is an intersectional identity worth exploring and worth value. It’s important to note that historically being Chicana with a voice, and also being queer was still extremely taboo. “Gay and lesbian lifestyles are taboo, and Chicano culture and are harshly castigated. To violate this fundamental moral standard is to invite ostracism, violence or both.” [4]The inclusion of her queer identity as a form of intersectionality, a form of a borderland, was revolutionary for the time. Not only was she talking about queer identity and gender during a time when it was dangerous, but she used her lesbian identity as a form of intersectionality to demonstrate aspects of her philosophy. “She says that as a queer, she has no culture yet at the same time she has so much. Thus she inhabits Sandoval’s idea of a new kind of social movement that is “differential.” She revolutionized how we view queerness and gender regarding identity, and including this aspect of her identity exemplifies bravery and a revolutionary mindset. Within her work, Borderlands, Anzaldúa outlines the concept of cultural tyranny. Aspects within Latino and Chicano culture that aim to exclude. Within this aspect of her book, she directly addresses the systemic issue of machismo culture. The same machismo culture that when she dares to speak her mind and her truths, they call her a “traitor,” a “sellout. ”She writes: “Not me sold out my people, but they me.” [5]. Not only does she defy cultural expectations, but she’s unafraid to critique the culture and its exclusionary aspects as well.

Given the historical context, Anzaldúa was a revolutionary woman with revolutionary ideas. As a queer Chicana, she shook the modern landscape of Chicana identity by pulling to the forefront the Chicano consciousness of the true narrative of borderland people and by validating and empowering the identity of those that live and in-between those that live in a borderland. She countered racist ideology with a counter-narrative and a call to action for those who live in borderlands for those who live in a borderland to deassimilate to choose to reengage with the intersectionality of their identities. I think Anzaldúa legacy can best be summed up In this quote from Revolutionary women of Texas and Mexico: “In our work, we use exploration leading to cultural identity as a way of seeing self and others, and the basis for this is Anzaldúas framework. Exploration starts us on the road not only to understanding others and their identities but also to looking within to expand our perspectives in articulating our own cultural identity.” [6]

[1] Gloria Anzaldúa, Borderlands La Frontera , 4th ed. (San Francisco, California : aunt lute books, 2007).

[2] Douglas Massey, “The Mexico-U.S. Border in the American Imagination,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 160, no. 2 (June 2016): 160–77, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26159208, 161.

[3] Douglas Massey, “The Mexico-U.S. Border in the American Imagination,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 160, no. 2 (June 2016): 160–77, https://www.jstor.org/stable/26159208, 168.

[4] María Herrera-Sobek, “Gloria Anzaldúa: Place, Race, Language, and Sexuality in the Magic Valley,” PMLA/Publications of the Modern Language Association of America 121, no. 1 (January 2006): 266–71, https://doi.org/10.1632/003081206x129800, 270.

[5] Gloria Anzaldúa, Borderlands La Frontera , 4th ed. (San Francisco, California : aunt lute books, 2007), 47.

[6] 1. Kathy Sosa et al., Revolutionary Women of Texas and Mexico: Portraits of Soldaderas, Saints, and Subversives (San Antonio, TX: Maverick Books, Trinity University Press, 2020), 202.

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why am I compelled to write? Because the writing saves me from this complacency I fear. Because I have no choice. Because I must keep the spirit of my revolt and myself alive. Because the world I create in the writing compensates for what the real world does not give me. By writing I put order in the world, give it a handle so I can grasp it. I write because life does not appease my appetites and hunger. I write to record what others erase when I speak, to rewrite the stories others have miswritten about me, about you. To become more intimate with myself and you. To discover myself, to preserve myself, to make myself, to achieve self-autonomy. To dispell the myths that I am a mad prophet or a poor suffering soul. To convince myself that I am worthy and that what I have to say is not a pile of shit. To show that I can and that I will write, never mind their admonitions to the contrary. And I will write about the unmentionables, never mind the outraged gasp of the censor and the audience. Finally I write because I'm scared of writing but I'm more scared of not writing.

— Gloria Anzaldúa, “Speaking In Tongues: A Letter To 3rd World Women Writers."

Follow Diary of a Philosopher for more quotes!

#Gloria Anzaldúa#Speaking In Tongues#writeblr#writeblr community#writers on tumblr#writers of tumblr#writing community#writing inspiration#writers on writing#quote#quotes#book quotes#literature#literature quotes#on writing#studyblr#gradblr#academia#dark academia#chaotic academia#light academia#latin america#latin american literature

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

#Gloria Anzaldúa#writers on writing#writeblr#writeblr community#book quotes#quote#quotes#literature quotes#lit quotes#creative writing#writers of tumblr#writers on tumblr#writblr#writing community#book writing#fiction writing#novel writing#on writing#writing inspiration#writing inspo#writing thoughts#writing reference#latam#latin american literature#latin america#south america

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gestos del cuerpo, escribiendo para idear / Gloria Anzaldúa

Cuando escribo de noche, soy consciente de la luna, Coyolxauhqui, flotando sobre mi casa. La imagino muerta y decapitada, una cabeza con los párpados cerrados. Pero luego sus ojos se abren y la miro dar luz a los lugares oscuros, la veo iluminarlos. Escribir es un proceso de descubrimiento y de percepción que produce saberes y conocimiento. A menudo soy llevada por el impulso de escribir algo, por el deseo y la urgencia de comunicar, de dar sentido, de que las cosas tengan sentido, de crearme a mí misma a través de este acto productor de conocimiento. Llamo a este impulso “la imperativa Coyolxauhqui”: una lucha por reconstruirse a una misma y sanar los sustos productos de heridas, traumas, racismo y otros actos de violación que hacen pedazos nuestras almas, nos dividen, disuelven nuestras energías y nos acechan. La imperativa Coyolxauhqui es el acto de convocar a que vuelvan esas partes de una misma, esas partes del alma que se han dispersado o perdido, es el acto de duelar las pérdidas que nos acechan. La bestia sombra y su ayudante desconocimientos (la ignorancia que cultivamos en orden de permanecer irresponsables y alejarnos del conocimiento), están tenazmente aferrados a nosotrxs. Lidiar con la falta de coherencia y estabilidad en la vida, así como el aumento de las tensiones y conflictos, me motivan para procesar la lucha. La aguda angustia mental, emocional y espiritual me motiva para escribir mi/nuestras experiencias. Más que eso, mis aspiraciones hacia la integración mantienen mi cordura, una cuestión de vida y muerte. Lidiar con (des)conocimientos, con lo que no quiero saber, abrir y cerrar mis ojos y oídos a las realidades culturales, expandir mi consciencia y mi percepción, o rehusarme a hacerlo, a veces, resulta en el descubrimiento de la sombra positiva: aspectos ocultos de mí y del mundo. Cada molestia es un grano de arena en la ostra de la imaginación. A veces, lo que se acumula alrededor de una molestia o una herida, produce una perla de gran revelación, una teoría.

Estoy en constante lucha con mis propias formas de producción cultural y con el rol que juego como artista. Al espacio donde doy esta lucha con mis creaciones lo llamo “nepantla”. Nepantla es el lugar donde mis códigos personales y culturales se chocan, donde me enfrento a lo que el mundo dicta, donde estos distintos mundos se fusionan en mi escritura. Soy consciente de varios nepantlas – lingüístico, geográfico, de género, sexual, histórico, cultural, político y social- cuando escribo. Nepantla es el punto de contacto y el lugar entre mundos, entre la existencia física e imaginaria, entre las realidades ordinarias y no-ordinarias (espirituales). Estas cuestiones de nepantla automáticamente se infunden en mi escritura: no tengo que lidiar yo misma con estos puntos particulares; estos nepantlas me habitan e inevitablemente emergen en cualquier cosa que esté escribiendo. Nepantlas son lugares de constante tensión, donde las piezas ausentes o perdidas pueden ser convocadas a volver, donde la transformación y la sanación son posibles, donde la totalidad se mantiene fuera de alcance, pero parece posible.

Escribo para “idear” –como se dice en español: “para formar o concebir una idea, desarrollar una teoría, inventar e imaginar”.

Mi trabajo es cuestionar, afectar y cambiar los paradigmas que gobiernan las nociones prevalentes de realidad, identidad, creatividad, activismo, espiritualidad, raza, género, clase y sexualidad. Para desarrollar una epistemología de la imaginación, una psicología de la imagen, he construido mi propio sistema simbólico. Mientras intento crear nuevos marcos epistemológicos, reflexiono constantemente sobre la actividad de idear. El deseo o la necesidad de compartir el proceso de “seguimiento” de las imágenes y la creación de “historias” y teorías me motivan para escribir este texto.

Existen pocos precedentes sobre las relaciones directas de lxs artistas con sus imágenes. Hay muy poca investigación directa, personal y artística, así que tuve que implicarme en mis propias experiencias y construir mis propias fórmulas. Intento dar testimonio de mi propio proceso y conciencia de escritora chicana. Soy la que escribe y se escribe. Últimamente es el escribir que me escribe. Me creo a mí misma en lo que “leo” y en lo que “hablo”. La escritura es donde cuestiono la realidad, la identidad, el lenguaje y las representaciones de la cultura dominante y de dominación ideológica.

Utilizando un enfoque multidisciplinario y un formato “narrativo”, teorizo sobre las luchas propias y ajenas por la representatividad, la identidad, la propia inscripción y las expresiones creativas. Cuando “me hablo” en escrituras creativas y teóricas, estoy constantemente cambiando de posición –lo cual implica considerar remolinos ideológicos, disonancias culturales y la convergencia de mundos rivales. Significa tratar con el hecho de que yo, como la mayoría de las personas, habito en diferentes culturas y, al cruzar a otros mundos, giro hacia o me alejo de las perspectivas de cada uno; significa vivir en espacios liminales, en nepantlas. Focalizándome en la experiencia e identidad chicana/mestiza (mexicana tejana) en distintos ejes –escritora/artista, intelectual, académica, profesora, mujer, chicana, feminista, lesbiana, de clase trabajadora- intento analizar, describir y recrear estos desplazamientos identitarios. Hablar desde geografías de distintos “países” me vuelve una hablante privilegiada. “Hablo en lenguas” –entiendo los lenguajes, las emociones, los pensamientos y fantasías de las varias sub-personalidades que me habitan y los varios suelos desde donde hablan. Para hacerlo, debo descifrar cuál persona (yo, ella, vos, nosotrxs, ellxs), qué tiempo (presente, pasado, futuro), qué lenguaje y registro, desde qué voz o estilo hablar. La formación de la identidad (que implica “leerse” y “escribirse” a una misma y al mundo) es un proceso alquímico que sintetiza dualidades, contradicciones y perspectivas desde estos diferentes yoes y mundos.

En estas auto-etnografías soy a la vez observadora y participante –simultáneamente me miro a mí misma como objeto y sujeto. En un abrir y cerrar de ojos, desdibujo las fronteras entre sujeto y objeto, de clase o género, entre otras. Mi postura metodológica emerge en el proceso de escritura, y así también mi teoría. Trato a todos mis trabajos, incluidos estos capítulos, como ficción o poesía.

Al formular nuevas formas de conocer, nuevos objetos de conocimiento, nuevas perspectivas y nuevos ordenamientos de las experiencias, lidio, casi inconscientemente, con una nueva metodología –una que espero no reafirme los modos predominantes. Llego a saber cómo “leer” y “escribir”; llego al saber y al conocimiento a través de imágenes e “historias”. Uso varios formatos narrativos consistentes con las experiencias sobre las que reflexiono, y uso cualquier lenguaje y estilo que se corresponda con la forma en que trabajo. Creo que la meditación y la percepción consciente sobre la significación de la imagen promueve (y no obstruye), en mí, su creadora, y en usted, su lectorx/intérprete/co-creadorx, la producción de la obra. Obtengo marcos de referencia a través de teorizar experiencias cotidianas, al permitirle a las imágenes que me hablen a mí y a través de mí, imaginando mis caminos a través de las imágenes y siguiéndolas a sus profundos cenotes, dialogando con ellas, y traduciendo lo que he vislumbrado. A veces la sombra bloquea este proceso y domina mi conducta, haciendo este proceso doloroso.

No puedo usar el lenguaje tradicional para describir, referirme o contener las nuevas subjetividades. Usando métodos primarios de presentación (auto-historia) antes que métodos secundarios (interpretar las concepciones de otras personas), reflexiono sobre los aspectos psicológicos/metodológicos de mi propia expresión. Examino mis heridas, toco mis cicatrices, mapeo la naturaleza de mis conflictos, canturreo a las musas que persuado para inspirarme, me arrastro en la forma que toma la sombra, y trato de hablarles.

Los métodos tienen supuestos subyacentes, posiciones teóricas implícitas y premisas básicas. Hay dos puntos de vista: el perceptual, que tiene una realidad literal; y el imaginario, que tiene una realidad psíquica. Al elaborar imágenes en historias (la historia que cuento sobre las imágenes) uso pensamiento imaginativo, empleo una consciencia imaginativa. Me guía el espíritu de la imagen. Mi naguala (daimon o espíritu guía) es una sensibilidad interna que guía mi vida –una imagen, una acción, o una experiencia interna. Mi imaginación y mi naguala están conectadas, son aspectos del mismo proceso, de la creatividad. A menudo mi naguala me lleva hacia cosas que son contrarias a mi voluntad y a mi propósito (compulsiones, adicciones, negatividades), y resulta en un impasse angustiante. Sobrellevar estos impasses es parte del proceso. Este modo de percepción es un tipo de pensamiento mágico: lee lo que sucede en el mundo exterior en términos de mis intensiones e intereses personales. Usa los acontecimientos externos para dar sentido a mi propia creación de mito. El pensamiento mágico no es valorado tradicionalmente en la escritura académica.

Mi texto es sobre la imaginación (la facultad de la psique para crear imágenes, el poder de producir ficción o historias, películas internas como la holocubierta de Star Trek), sobre la “imaginación activa”, ensueños (soñar despiertx), y sobre la interacción consciente entre éstos. Estamos conectadxs con el cenote a través del árbol de la vida, individual y colectivo, y nuestras imágenes y ensueños emergen de esa conexión, desde el ser-en-comunidad (interior, espiritual, natural/animal, racial/étnica, de intereses, vecindario, ciudad, nación, planeta, galaxia y universos desconocidos). Uso soñar o ensueños (hacer imágenes) para darme cuenta de lo que está mal, predecir eventos actuales o futuros; y establecer conexiones ocultas, desconocidas, entre la experiencia de vida y la teoría. Este texto es sobre los momentos de sufrimiento que disparan pensamientos, reflexiones y contemplaciones imaginativas. Se enfrenta indirectamente con los símbolos con los que asocio ciertas experiencias y procesos arquetipales:

Los pensamientos pasan como ondas a través de su cuerpo, haciendo que un músculo se tense por aquí, se afloje por allá. Todo pasa por la piel, los ojos, los oídos. Ella experimenta la realidad físicamente. No existe una acción por fuera de lo físico. Toda acción es el resultado de una decisión, de un conflicto interno, una lucha, resolución o estancamiento. El cuerpo siempre refleja actividad interior. “Espanto” en Los sueños de la Prieta.

Para mí, escribir es un gesto del cuerpo, un gesto de creatividad, un trabajo de adentro hacia afuera. Mi feminismo se basa en realidades corporales, no en abstracciones incorpóreas. El cuerpo material es el centro, y es central. El cuerpo es la base del pensamiento. El cuerpo es texto. Escribir no se trata de estar en tu cabeza; se trata de estar en tu cuerpo. El cuerpo responde física, emocional e intelectualmente a estímulos internos y externos, y el escribir guarda, ordena y teoriza estas respuestas. Para mí, el escribir comienza con el impulso de superar barreras, dar forma a ideas, en imágenes y palabras que viajen por el cuerpo y hagan eco en la mente, creando algo que antes no existía. El proceso de escritura es el mismo proceso misterioso que usamos para hacer el mundo.

Hay una diferencia entre hablar con las imágenes/historias y hablar sobre ellas. En este texto pretendo hablar con las imágenes/historias, meterme en el proceso creativo y espiritual, y con sus aspectos rituales. Al promover la relación entre ciertas imágenes y conceptos y mi propia experiencia y psique, fusiono narrativas personales con discursos teóricos, viñetas autobiográficas y prosa teórica. Creo un género híbrido, un nuevo modo discursivo, al que llamo “auto-historia” y “autohistoria-teoría”. Conectando experiencias personales con realidades sociales, obtengo auto-historia, y teorizando sobre esta actividad, desemboco en autohistoria-teoría. Esta es una forma de inventar y producir conocimiento, sentido, e identidad a través de auto-inscripciones. Al hacer ciertas experiencias personales el objeto de este estudio, borro también las fronteras entre lo público y lo privado.

Al escribir este libro, tuve que descifrar cómo imaginar/crear/descubrir ciertos conceptos/teorías, cómo darle forma a cada ensayo, su estructura y diseño –en otras palabras, tuve que mapear el universo de cada ensayo, despejar su terreno. Hago estos descubrimientos mientras escribo, y no antes. Descubro y libero la energía que da forma a cada trabajo, descubro sus premisas, argumentos y contra-argumentos, ideas principales y su arco narrativo. Rastreo aquello que subyace a la idea original, sigo hasta su punto de inflexión, su dinámica emocional y la conexión entre sus partes. Trato a cada ensayo como si fuera una historia, con antagonismo, diálogo, crisis, clímax, resolución y poética. Considero varios aspectos de un borrador: su técnica narrativa, el uso del lenguaje –cuándo es necesario el uso del español, cuando el uso de lenguaje teórico es pertinente o el uso de lenguaje coloquial es apropiado.

No escribo desde una posición disciplinaria única. Escribo desde afuera de una lengua oficial teórica o filosófica. La mía es una lucha por el reconocimiento y legitimidad de aquellxs excluidxs, especialmente mujeres, personas de color, queers y otredades. Organizo y ordeno estas ideas como “historias”. Creo que es a través de la narrativa que terminás de entenderte y conocerte, y que el mundo cobra sentido. A través de narrativas es que formulás tus identidades, al ubicarte inconscientemente en narrativas sociales que no fueron hechas por vos. Tu cultura te da la historia de tu identidad, pero en un buscado rompimiento con la tradición creás una historia alternativa.

Este libro contiene muchos tipos de “narrativas” que hacen a mi vida: feminismo, raza, etnicidad, queericidad, género, práctica artística. Trata de los procesos que ocurren al leer, escribir y hacer otros actos creativos. Mientras se lee o se escribe un libro suceden imaginaciones chamánicas. Los “vuelos” controlados a los que nos envía la lectura o escritura son una suerte de “ensueños”, similares a los procesos del sueño o la fantasía, parecidos a los vuelos mágicos de los viajes chamánicos. Mi imagen de los ensueños es de la Llorona montada en un caballo salvaje, volando. En una de sus facetas es vista como una mujer con cabeza de caballo. Me “apropio” de las figuras, símbolos y prácticas de la cultura indígena mexicana, como Coyolxauhqui. Uso figuras imaginales (arquetipos) del mundo interno. Me detengo en el rol de la imaginación en el viaje a realidades “no ordinarias”, en el uso de lo imaginante en el nagualismo y su conexión con la espiritualidad de la naturaleza. Este texto trata sobre actos de vuelo imaginativo en la realidad y las construcciones y reconstrucciones de la identidad.

Al re-escribir narrativas de identidad, nacionalismo, etnicidad, raza, clase, género, sexualidad y estética, intento mostrar (no sólo nombrar) cómo sucede la transformación. Mi trabajo no es sólo interpretar o describir realidades, sino crearlas a través del lenguaje y la acción, los símbolos y las imágenes. Mi tarea es guiar a lxs lectorxs y darles el espacio para co-crear, usualmente en contra de la cultura, familia y mandamientos del ego, en contra de las censuras internas y externas, en contra de lo que dictan los genes. Desde la infancia nuestras culturas nos inducen a estados de semi-trance de la consciencia ordinaria, a estar de acuerdo con las personas que nos rodean, a creer que todo está bien como está. Es extremadamente difícil cambiar el enfoque y salir de este trance.

Este texto cuestiona sus propios intentos de formalización y ordenamiento, sus propias estrategias, las maquinaciones del pensamiento mismo, de la teoría formulada en un nivel de discurso experiencial. Explora las variadas estructuras de la experiencia que organizan mundos subjetivos, e ilumina el sentido en la experiencia y conducta personales. Entra en diálogo con la nueva historia y la vieja, e intenta revisar la historia oficial. Espero contribuir en el debate entre académicxs activistas al tratar de intervenir, interrumpir, desafiar y transformar las estructuras de poder existentes que limitan y constriñen a las mujeres. Mis principales campos disciplinares son la escritura creativa, el feminismo, el arte, la literatura, la epistemología, así como los estudios espirituales, raciales, de frontera, Raza y étnicos. Al cuestionar sistemas de conocimiento, intento agregar o alterar sus normas y hacer cambios en estos campos presentando nuevos modelos teóricos. Con el nuevo tribalismo desafío las narrativas nacionalistas chicanas (así como otras). Mi dilema y el de otras escritoras chicanas y mujeres de color, es doble: cómo escribir (producir) sin ser inscrita (reproducida) en la estructura blanca dominante, y cómo escribir sin reinscribir y reproducir aquello frente a lo que nos hemos rebelado. Nuestra tarea es escribir en contra del decreto de que las mujeres deben temerle a su propia oscuridad, de que no la abordemos en nuestras escrituras. Nuestra tarea es imaginar a Coyolxauhqui, no muerta y decapitada, sino con los ojos bien abiertos. Nuestra tarea es iluminar la oscuridad.

Prólogo a la edición en inglés de Light in the dark/Luz en lo Oscuro. Traducción Violeta Benialgo y Valeria Kierbel. Editorial Hekht (2015).

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

from: "The Postmodern Llorona" by Gloria Anzaldúa

from: "The Postmodern Llorona"The young woman is not afraid of La Lloronashe has become La LloronaHer high-pitched yell is curdling the blood of her parents,raising the hair on the back of their necks.Most days she floats through air on a natural high.If she ever remembers the machowho abandoned and betrayed herit does not render her paralyzed in susto and grief. Anzaldúa, Gloria. “The…

View On WordPress

#Gloria Anzaldúa#La Llorona#National Poetry Month#Poem#Poetry#The Gloria Anzaldúa Reader#The Postmodern Llorona

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Because I, a mestiza,

continually walk out of one culture

and into another,

because I am in all cultures at the same time,

alma entre dos mundos, tres, cuatro,

me zumba la cabeza con lo contradictorio.

Estoy norteada por todas las voces que me hablan

simultáneamente."

– Gloria Anzaldúa, "Una lucha de fronteras / A Struggle of Borders" from Borderlands / La Frontera: The New Mestiza

[Translation of the second half: "soul between two worlds, three, four / my head buzzes with the contradictory / I'm disoriented by all the voices that speak to me / simultaneously"]

Anyway this is why I keep saying that people refuse to be normal about the idea of mixed race people and interracial relationships and communities happening and creating children.

I am black and black only until it is convenient to call me white. And it doesn't matter that I'm also native because I'm too black to be native anyway. I've talked about being multi-racial and having even further racial mixing in my extended family since I made this blog in 2014 but that doesn't matter if any of my racial mix can be used as a weapon against me.

Y'all complain about the stereotype of the tragic mulatto without understanding why that stereotype exists in the first place.

#as a mixed race person myself#who grew up in a third culture#this is very real#and I'm not black nor indigenous#which I know adds a whole other kind of nuance to these things#colorism is a whole damn thing#anyways borderlands is a fantastic read and one of my favorites in this realm of race theory#gloria anzaldúa

19K notes

·

View notes

Text

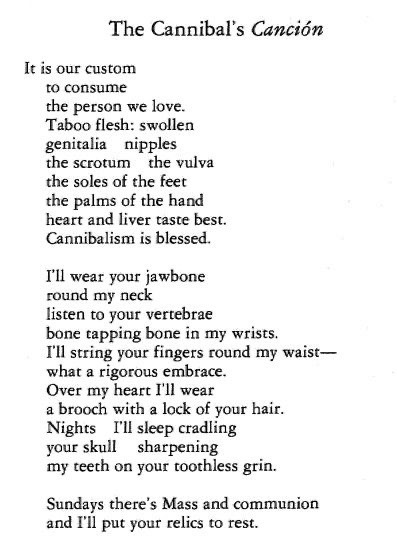

I’ll wear your jawbone round my neck listen to your vertebrae bone rapping bone in my wrists I’ll string your fingers round my waist— what a rigorous embrace.

- from "The Cannibal's Canción," Gloria Anzaldúa (x)

0 notes

Text

I write to record what others erase when I speak, to rewrite the stories others have miswritten about me, about you.

— Gloria Anzaldúa, “Speaking In Tongues: A Letter To 3rd World Women Writers."

Follow Diary of a Philosopher for more quotes!

#Speaking In Tongues: A Letter To 3rd World Women Writers#Gloria Anzaldúa#Speaking In Tongues#quote#quotes#academia#dark academia#gradblr#studyblr#book quotes#chaotic academia#philosophy#philosophy quotes#decolonial practices#decolonization#colonialism#colonization#colonial violence#latin#latine#latinx#latino#Latam#latin america#imperialism#colonialsm

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Excerpt from Who Are My People, by Gloria E. Anzaldúa

I am a wind-swayed bridge, a crossroads inhabited by whirlwinds. Gloria, the facilitator, Gloria the mediator, straddling the walls between abysses. "Your allegiance is to La Raza, the Chicano movement," say the members of my race. "Your allegiance is to the Third World," say my Black and Asian friends. "Your allegiance is to your gender, to women," say the feminists. Then there’s my allegiance to the Gay movement, to the socialist revolution, to the New Age, to magic and the occult. And there’s my affinity to literature, to the world of the artist. What am I? A third world lesbian feminist with Marxist and mystic leanings. They would chop me up into little fragments and tag each piece with a label. You say my name is ambivalence? Think of me as Shiva, a many-armed and legged body with one foot on brown soil, one on white, one in straight society, one in the gay world, the man’s world, the women’s, one limb in the literary world, another in the working class, the socialist, and the occult worlds. A sort of spider woman hanging by one thin strand of web. Who, me confused? Ambivalent? Not so. Only your labels split me.

Source: This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color, page 228

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza - Gloria E. Anzaldúa

Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza is a 1987 semi-autobiographical work by Gloria E. Anzaldúa that examines the Chicano and Latino experience through the lens of issues such as gender, identity, race, and colonialism. Borderlands is considered to be Anzaldúa’s most well-known work and a pioneering piece of Chicana literature. In an interview, Anzaldúa claims to have drawn inspiration from the ethnic and social community of her youth as well as from her experiences as a woman of color in academia. Scholars also argue that Anzaldúa re-conceptualized the theory of the "mestiza" from the Chicano Movement. Anzaldúa alternates between Spanish and English using a technique such as “code-switching.” Borderlands has been a subject of controversy; it has been promoted in educational spaces for its role in affirming student identity, but also targeted by Arizona House Bill 2281, which banned the teaching of ethnic studies courses and literature that were thought to “promote resentment towards a race or class of people”.

Read more about this novel on Wikipedia.

Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza - Gloria E. Anzaldúa

Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza es una obra semi-autobiográfica de 1987 de Gloria E. Anzaldúa que examina la experiencia chicana y latina a través del lente de temas como el género, la identidad, la raza y el colonialismo. Borderlands es considerada la obra más conocida de Anzaldúa y una obra pionera de la literatura chicana. En una entrevista, Anzaldúa afirma haberse inspirado en la comunidad étnica y social de su juventud, así como en sus experiencias como mujer de color en academia. Los especialistas también argumentan que Anzaldúa reconceptualizó la teoría de la "mestiza" del Movimiento Chicano. Anzaldúa alterna entre español e inglés usando una técnica conocida como "code-switching". Borderlands ha sido objeto de controversia; ha sido promovido en espacios educativos por su rol en la afirmación de la identidad estudiantil, pero también ha sido blanco del House Bill 2281 de la Cámara de Representantes de Arizona, que prohibió la enseñanza de cursos de estudios étnicos y literatura que se pensaba que "promovían el resentimiento hacia una raza o clase de personas".

Lee más sobre la autora en Wikipedia.

#latam classic lit works#literature#literatura#Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza#Gloria E. Anzaldúa

11 notes

·

View notes

Note

Omg I hope your final paper turns out well!! Congrats on graduating ‼️🎉

KDJDJEJEJS THANK YOU!!!! Its almost done! I have a little over 4 pages written of 6 i just have to focus today and I can get it done and then....my capstone presentation which is due Wednesday and I'm officially done!

#asks#anonymous#should i specify this paper is almost entirely in my second language bc thats where im struggling to motivate myself#its about the intersection of gender and language in borderlands/la frontera. coser y cantar. y afro-latina#<- book by gloria anzaldúa. play by dolores prida. and poem by elizabeth acevedo#my profe has put high expectations on me so im hoping i live up to them#not sanji

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Gloria E. Anzaldúa

The New Speakers

Words are our trade

we speak them soft

we speak them hard

we do not push the hand

that writes, the times do that.

We are our age’s mouthpiece.

There is no need for words

to fester in our minds

they germinate in the open

mouth of the barefoot child,

in the midst of restive crowds.

They wither in ivory towers

and are dissected in college classes.

Words. Some come trippingly

on the palate. Some come laboriously.

Some are quickened by friends,

some prompted by passersby.

Critics label the speakers: male, female.

They assign genitals to our words

but we’re not just penises or vaginas

nor are our words easy to classify

Some of us are still hung-

up on the art-for-art trip

and feel that the poet

is forever alone.

Separate.

More sensitive.

An outcast.

That suffering is a way of life,

that suffering is a virture

that suffering is the price

we pay for seeing the future.

Some of us are still hung up

substituting words for relationships

substituting writing for living.

But what we want

–what we presume to want–

is to see our words engraved

on the people’s faces,

feel our words catalyze

emotions in their lives.

What we want is to become

part of the common consumption

like coffee with morning paper.

We don’t want to be

Stars but parts

of constellations.

#Gloria E. Anzaldúa#poem#poetry#poet#National Hispanic Heritage Month#National Hispanic Heritage Month 2024

1 note

·

View note

Text

favourite poems of july

knar gavin strindberg grey

dahlia ravikovitch the love of an orange (tr. chana bloch)

danez smith summer, somewhere

hannah gamble your invitation to a modest breakfast: “your invitation to a modest breakfast”

claire schwartz lecture on the history of the house

joseph brodsky collected poems in english, 1972-1999: “a part of speech”

ralph angel twice removed: “alpine wedding”

bob hicok insomnia diary: “spirit ditty of no fax-line dial tone”

caleb klaces language is her caravan

philip good & bernadette mayer alternating lunes

hester knibbe light-years (tr. jacquelyn pope)

tracy k. smith life on mars: “the universe as primal scream”

rigoberto gonzález other fugitives and other strangers: “the strangers who find me in the woods”

stephen edgar murray dreaming

james schuyler other flowers: uncollected poems: “light night”

amy beeder because our waiters are hopeless romantics

diane seuss backyard song

tomás q. morín love train

safiya sinclair the art of unselfing

carol muske-dukes skylight: “the invention of cuisine”

peter gizzi the outernationale: “vincent, homesick for the land of pictures”

william matthews selected poems and translations, 1969-1991: “onions”

c.k. williams butcher

mark mccloskey the smell of the woods

jennifer chang the age of unreason

richard blanco city of a hundred fires: “contemplations at the virgin de la caridad cafeteria, inc.”

bob hicock the pregnancy of words

j. allyn rosser impromptu

carl phillips then the war

stephanie young ursula or university: “essay”

gloria e. anzaldúa the new speakers

kofi

#tbr#knar gavin#strindberg grey#strindberg gray#dahlia ravikovitch#the love of an orange#chana bioch#danez smith#summer somewhere#hannah gamble#your invitation to a modern breakfast#claire schwartz#lecture on the history of the house#joseph brodsky#collected poems in english#a part of speech#collected poems in english 1972-1999#ralph angel#twice removed#alpine wedding#bob hicock#insomnia diary#spirit ditty of no-fax dial tone#caleb klaces#language is her caravan#philip good#alternating lunes#bernadette mayer#hester knibble#light-years

801 notes

·

View notes

Text

Feminist Non-Fiction Recs

Because feminism isn't only about your own voice and your own rights, but about the liberation of all women, it's important to uplift the voices of women who are rarely heard. To honour this international day of Women's Rights, here are some recommendations for non-fiction feminist theory books centered on women of colour.

Please note that this is a non-exhaustive list, and that some very important works might not figure on it. Take it as inspiration, not as a binding list of works to have read, and remember that this is only the surface of women of colour's writings on feminism.

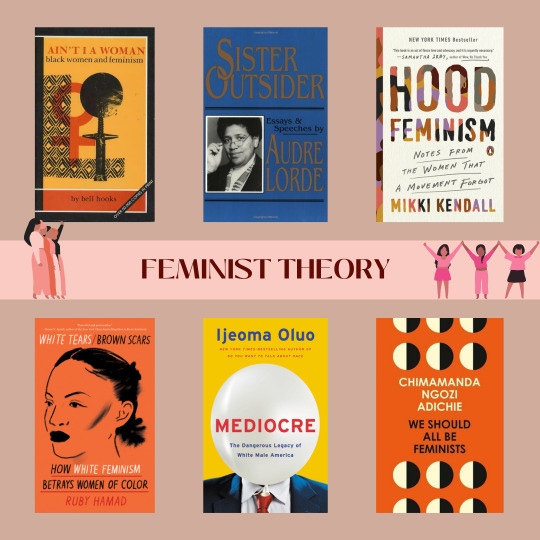

all of bell hooks' books, but I would recommend "Ain't I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism" to start with intersectional feminism

There Is No Hierarchy of Oppression; by Audre Lorde

Sister Outsider; by Audre Lorde (all of Audre Lorde, actually)

Hood Feminism; by Mikki Kendall

White Tears, Brown Scars; by Ruby Hamad

Mediocre; Ijeoma Oluo

We Should All Be Feminists; by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

This Bridge Called My Back; an anthology edited by Cherríe Moraga and Gloria E. Anzaldúa

Bad Feminist; by Roxane Gay

I Am Malala; by Malala Yousafzai

Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment; by Patricia Hill Collins

Arab & Arab American Feminisms: Gender, Violence, & Belonging; an anthology edited by Rabab Abduhaldi, Evelyn Alsultany and Nadine Naber

Making Space for Indigenous Feminism; an anthology edited by Joyce Green

Beyond Veiled Clichés: The Real Lives of Arab Women; by Amal Awad

The Trouble with White Women: A Counterhistory of Feminism; by Kyla Schuller

A Decolonial Feminism; Françoise Vergès

Eloquent Rage: A Black Feminist Discovers Her Superpower; by Brittney Cooper

Women, Race, & Class; by Angela Y. Davis

These books really only scrape the surface of an intersectional approach of feminism focused on race, and if you want to discover more works, I would recommend looking at intersectional feminism and decolonial feminism. Also, if you're not a native English speaker or if you speak fluently multiple languages, I recommend looking for feminist books originally written in other languages that may not have been translated to English, as they offer a perspective that is not so American-centered, which I feel is the case in too much of today's feminism.

#international women's day#feminist books#feminist theory#intersectional feminism#decolonial feminism#women of color#non fiction books#book recs#book recommendations

118 notes

·

View notes

Text

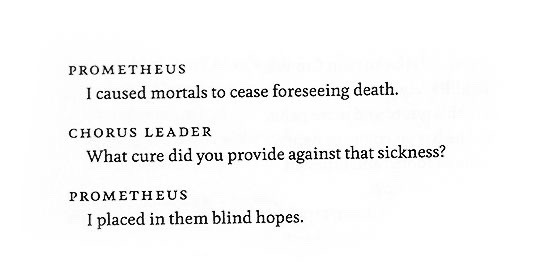

On rot

Prometheus Bound by Aeschylus | unknown | Faustus by Goethe | The Cannibal's Canción by Gloria Anzaldúa | Possession (1981) | Wishbone by Richard Siken | Where It Begins by Erica Jong | View from glas door by Erika Kasischke |

#hello hello#today on the menu#rot#hope you enjoy#gimme prompts if you want more because we reached the limit of my publishable breakdowns#web weave#webweaving

175 notes

·

View notes

Text

By redeeming your most painful experiences, you transform them into something valuable, algo para compartir or share with others so they too may be empowered.

— Gloria Anzaldúa, "Now Let Us Shift"

Follow Diary of a Philosopher for more quotes!

#Gloria Anzaldúa#quote#quotes#book quotes#dark academia#academia#lit#lit quotes#studyblr#gradblr#inspirational quotes#inspiring quotes#mestiza#trauma#healing#chaotic academia#healing journey#self awareness#writing#chaotic acaemia#literature#literature quotes#philosophy#philosophy quotes

34 notes

·

View notes