#Günter Dietz

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Milestone Monday, Part 2

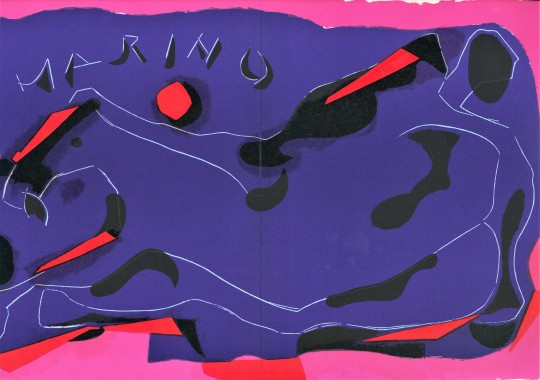

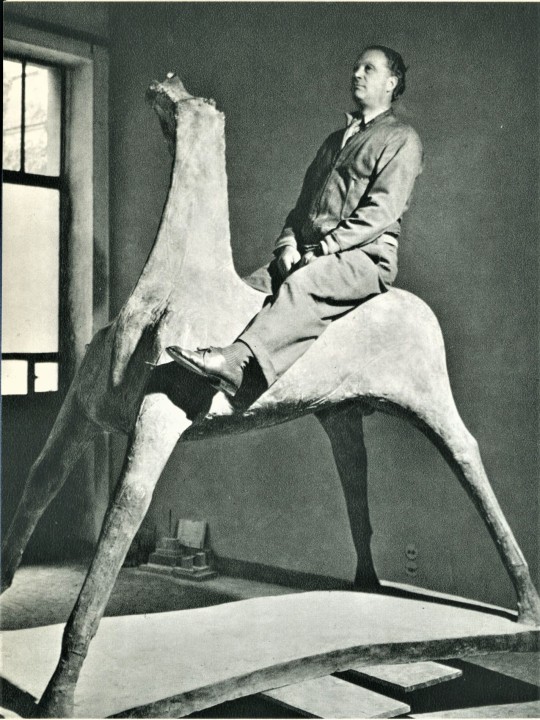

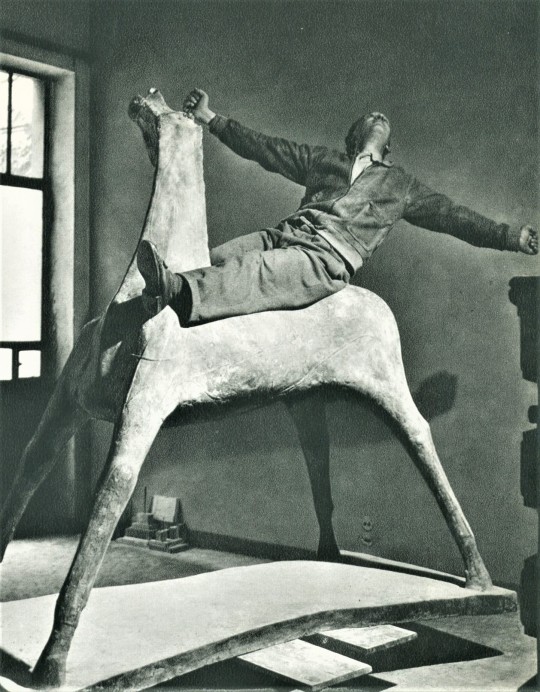

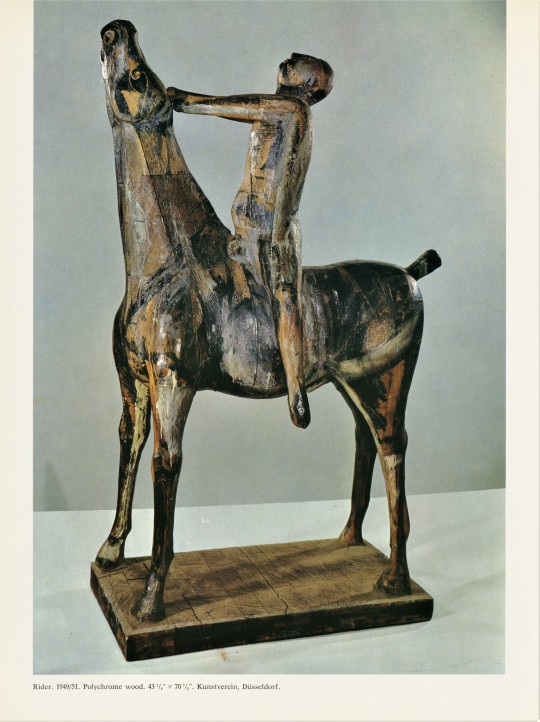

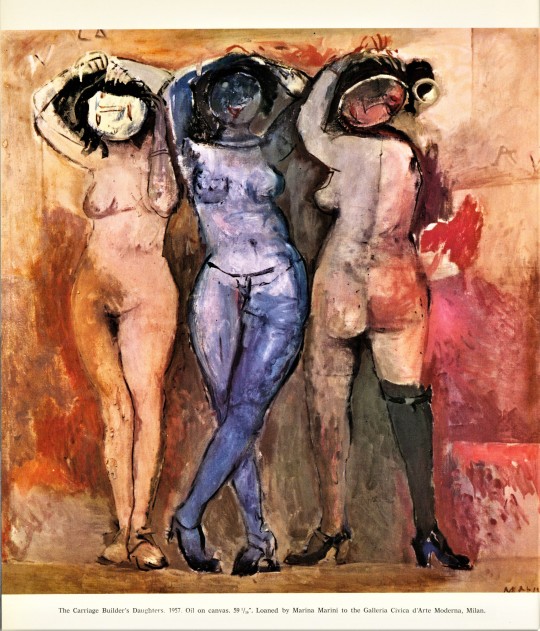

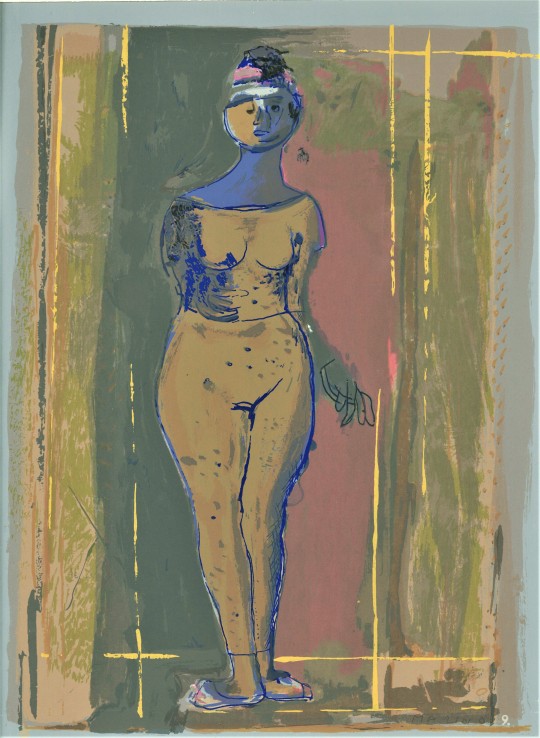

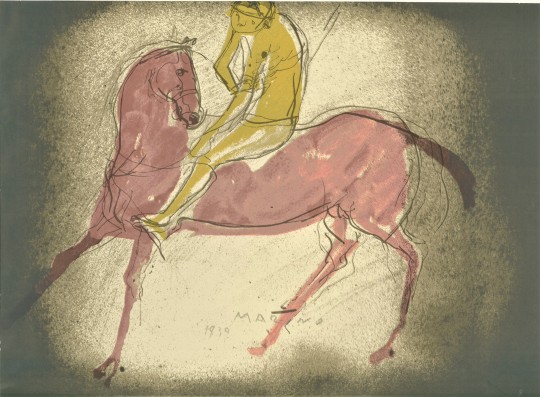

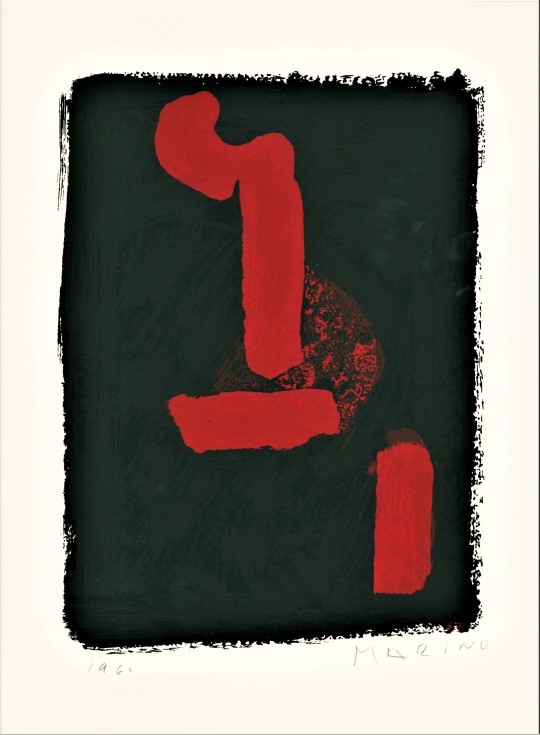

On this day, February 27 in 1901, Italian sculptor, painter, and printmaker Marino Marini was born in Tuscany, Italy. Besides his long professional career as an artist, Marini was a professor of art at the Scuola d’Arte di Villa Reale in Monza, near Milan, from 1929 to1940 and then a sculpture professor at the Accademia di Belle Arti di Brera (now Brera Academy) in Milan from 1940 to 1970. Marini developed several themes in his work, including equestrian, nudes, portraits, and circus figures. He was deeply influenced by ancient Etruscan sculpture and according to museum curator Lucy Flint, “by interpreting classical themes in light of modern concerns and with modern techniques, he sought to contribute a mythic image that would be applicable in a contemporary context.”

The first five images shown here are from Homage to Marino Marini, edited by G. di San Lazzaro and translated by Wade Stevenson, with the first image being an original lithograph. It was published in New York by Tudor Publishing Company in 1975.

The last five images are from Marino Marini: A Suite of Sixty-three Re-creations of Drawings and Sketches in Many Mediums, with an introductory text by Werner Haftmann, and published in New York by Harry N. Abrams in 1968 in a limited edition of 2000 copies, of which ours is one of 500 specially numbered copies. The images were produced by the Günter Dietz Workshop in Lengmoos, Germany using a unique reproduction system that combines the silkscreen printing process with photochemical color separation.

View more Milestone Monday posts.

#Milestone Monday#milestones#Birthdays#Marino Marini#sculpture#lithographs#paintings#Homage to Marino Marini#G. di San Lazzaro#Wade Stevenson#Tudor Publishing#Marino Marini: A Suite of Sixty-three Re-creations#Werner Haftmann#Harry N. Abrams#Günter Dietz

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ein Festtag auf der Dachauer Großbaustelle

Dachau: „…Die umgebaute Grundschule in Dachau-Ost wird in wenigen Jahren eines der größten und modernsten Schulhäuser des Landkreises. Gestern fand für das rund 49 Millionen Euro teure Großprojekt der symbolische Spatenstich statt. Die Bauarbeiten an der neuen Dreifachturnhalle auf dem Schulgelände sind derweil so gut wie abgeschlossen. Sportreferent Günter Dietz war die Freude anzusehen: „Da…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Photo

Friedensreich Hundertwasser (Austrian 1928-2000) Look at it on a Rainy Day (Regentag Portfolio) (Koschatzky 44-53) 1971-72 Stamp-signed with stamped titles, Japanese embossed seals and miniature depictions of the image in each margin, printed by Dietz Offizin, Lengmoss, Bavaria and Günter Dietz via @Bonhams

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sippenhaft - Wikipedia

This article is about the German tradition and practice. For similar practices in other countries or cultures, see

Kin punishment

.

Sippenhaft or Sippenhaftung (German: [ˈzɪpənˌhaft(ʊŋ)], kin liability) is a German term for the idea that a family or clan shares the responsibility for a crime or act committed by one of its members,[1] justifying collective punishment. As a legal principle, it was derived from Germanic law in the Middle Ages, usually in the form of fines and compensations.

Origins

Medieval period

Prior to the adoption of Roman law and Christianity, Sippenhaft was a common legal principle among Germanic peoples, including Anglo-Saxons and Scandinavians.[2] Germanic laws distinguished between two forms of justice for severe crimes such as murder: blood revenge, or extrajudicial killing; and blood money, pecuniary restitution or fines in lieu of revenge, based on the weregild or "man price" determined by the victim's wealth and social status.[3] The principle of Sippenhaft meant that the family or clan of an offender, as well as the offender, could be subject to revenge or could be liable to pay restitution.[4] Similar principles were common to Celts, Teutons, and Slavs.[5]

Nazi Germany

In Nazi Germany, the term was revived to justify the punishment of kin (relatives, spouse) for the offence of a family member. In this form of Sippenhaft the relatives of persons accused of crimes against the state were held to share the responsibility for those crimes and subject to arrest and sometimes execution. Many people who had committed no crimes were arrested and punished under Sippenhaft decrees introduced after the failed 20 July plot to assassinate Adolf Hitler in July 1944.[6]:121-166

Examples of Sippenhaft being used as a threat exist within the Wehrmacht from around 1943. Soldiers accused of having 'blood impurities' or soldiers conscripted from areas outside of Germany also began to have their families threatened and punished with Sippenhaft. An example is the case of Panzergrenadier Wenzeslaus Leiss, who was accused of desertion on the Eastern Front in December 1942. After the Düsseldorf Gestapo discovered supposed 'Polish' links in the Leiss family, in February 1943 his wife, two-year-old daughter, two brothers, sister and brother-in-law were arrested and executed at Sachsenhausen concentration camp. By 1944, several general and individual directives were ordered within divisions and corps, threatening troops with consequences against their family. After 20 July 1944 these threats were extended to include all German troops and in particular, German commanders. A decree of February 1945 threatened death to the relatives of military commanders who showed what Hitler regarded as cowardice or defeatism in the face of the enemy. After the surrender of Königsberg to the Soviets in April 1945, the family of the German commander General Otto Lasch were arrested. These arrests were publicized in the Völkischer Beobachter.[6]:53-88

After the failure of the 20 July plot, the SS chief Heinrich Himmler told a meeting of Gauleiters in Posen that he would "introduce absolute responsibility of kin ... a very old custom practiced among our forefathers". According to Himmler, this practice had existed among the ancient Teutons. "When they placed a family under the ban and declared it outlawed or when there was a blood feud in the family, they were utterly consistent. ... This man has committed treason; his blood is bad; there is traitor's blood in him; that must be wiped out. And in the blood feud the entire clan was wiped out down to the last member. And so, too, will Count Stauffenberg's family be wiped out down to the last member."[7]

Accordingly, the members of the family of von Stauffenberg (the officer who had planted the bomb that failed to kill Hitler) were all under suspicion. His wife, Nina Schenk Gräfin von Stauffenberg, was sent to Ravensbrück concentration camp (she survived and lived until 2006). His brother Alexander, who knew nothing of the plot and was serving with the Wehrmacht in Greece, was also sent to a concentration camp. Similar punishments were meted out to the relatives of Carl Goerdeler, Henning von Tresckow, Adam von Trott zu Solz and many other conspirators. Erwin Rommel opted to commit suicide rather than be tried for his suspected role in the plot in part because he knew that his wife and children would suffer well before his own all-but-certain conviction and execution.

After the 20 July plot, numerous families connected to the Soviet sponsored League of German Officers made up of German prisoners of war, such as those of von Seydlitz and Paulus, were also arrested. Unlike a number of the 20 July conspirators families, those arrested for connection to the League were not released after a few months but remained in prison until the end of the war. Younger children of arrested plotters were not jailed but sent to orphanages under new names: von Stauffenberg's children were renamed "Meister".[8]

Present legal status

The principle of Sippenhaftung is considered incompatible with German Basic Law, and therefore has no legal definition. Implementation of Sippenhaft-like familial collective punishment policies by governmental institutions in Germany have been attempted, with mixed results and some controversy.[9]

See also

References

^ Black, Harry; Cirullies, Horst; Marquard, Günter Marquard (1967). Polec: dictionary of politics and economics = dictionnaire de politique et d'économie = Lexikon für Politik und Wirtschaft. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. p. 786. ISBN 9783110008920. OCLC 815964978. Usual practice in totalitarian states ... to prosecute the innocent dependents of a person being prosecuted, condemned or escaped.

^ Bartrop, Paul R.; Dickerman, Michael (2017-09-15). The Holocaust: An Encyclopedia and Document Collection [4 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781440840845.

^ Tuori, Kaius (2014-09-19). Lawyers and Savages: Ancient History and Legal Realism in the Making of Legal Anthropology. Routledge. ISBN 9781317815990.

^ "Interrogational Torture in Criminal Proceedings" (PDF). Institut für Rechtspolitik. Retrieved 27 September 2018.

^ Thakur, Upendra (2003-06-01). An Introduction to Homicide in India Ancient and Early Medieval Period. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 9788170170747.

^ a b Loeffel, Robert (2012). Family Punishment in Nazi Germany, Sippenhaft, Terror and Myth. Palgrave. ISBN 9780230343054.

^ Fest, Joachim (1996). Plotting Hitler's Death. New York: Henry Holt. p. 303. ISBN 0080504213.

^ Loeffel, Robert (2007). "Sippenhaft, Terror and Fear in Nazi Germany: Examining One Facet of Terror in the Aftermath of the Plot of 20 July 1944". Contemporary European History. 16 (1): 51–69. doi:10.1017/S0960777306003626.

^ Zier, Jan (2009-07-22). "Hartz 4: Keine Sippenhaft". Die Tageszeitung: taz (in German). ISSN 0931-9085. Retrieved 2018-09-28.

Further reading

Dagmar Albrecht: Mit meinem Schicksal kann ich nicht hadern. Sippenhaft in der Familie Albrecht von Hagen. Dietz, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-320-02018-8. (in German)

Harald Maihold: Die Sippenhaft: Begründete Zweifel an einem Grundsatz des „deutschen Rechts“. In: Mediaevistik. Band 18, 2005, S. 99–126 (PDF; 152 KB) (in German)

0 notes