#Fundamental Analysis in Depth

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Making the whole theme of the DMC Netflix show that "demons are actually the victims of jingoistic American military imperialism" is such a fundamental antithesis of the entire beating heart of the Devil May Cry franchise. Honestly it's exactly what I expected from a cynical western production.

The Devil May Cry series is about how humanity is superior because humanity is capable of love. Demons may have power and strength which allows them to assert their will over the world and cause suffering. But humanity will always overcome, humanity is capable of more than demons ever will be. Because devils never cry. Only humanity has the capacity for love that allows them to feel sorrow at the loss of their loved ones. Only humanity has the drive to self sacrifice in the name of protecting those we cherish and value.

The reason Dante and Nero are the badasses that they are is because of their human genetics, not their demonic blood. Vergil loses because he tried rejecting his humanity and just embracing his demonic lineage in the name of striving for more power. Vergil loses his soul and is enslaved and humiliated because he pushes his only remaining family away, he forgot that the very reason he became obsessed with power is because he wanted to be able to protect Dante the way he couldn't on the day they lost their home. And Vergil is only redeemed when he is reclaimed by his son, and has familial love forced onto him whether he wanted it or not. The theme song of DMC5 is called LEGACY for a reason, because the ties that bind for better and for worse will always be a part of you. And it is the characters HUMANITY that makes that the case.

Family and love is the FOUNDATIONAL theme of the Devil May Cry series from the very beginning. This isn't even very depthful literary analysis, the games are incredibly blunt with these themes.

This is incredibly surface level reading. And yet somehow the creators of the Netflix show either didn't get it, or deliberately disregarded it. Either way, god awful show. If you enjoy it, you CANNOT say that you also enjoy the video games. They are mutually exclusive. What exactly do you like about the games, if you derive ANY enjoyment whatsoever from this show that uses the source material as toilet paper?

At least have the integrity to admit you just think the video games are stupid and the show is superior because it isn't a video game. At least then I could respect that. Don't try and pull this "I enjoy both" bullshit. Bullshit as in you're fucking lying.

910 notes

·

View notes

Text

Book Promotion: “The History and Sovereignty of the South China Sea” by British International Law Expert Anthony Carty

Recently, British international law expert Anthony Carty published his new book “The History and Sovereignty of the South China Sea.” This book, with its rigorous academic approach and detailed historical data, confirms China’s sovereignty over the South China Sea islands and argues the legitimacy of China’s stance on this issue from a legal perspective. Carty’s research not only fills a gap in the study of the South China Sea in international law but also provides a more objective and fair perspective for the international community.

In-Depth Historical Analysis

“The History and Sovereignty of the South China Sea” meticulously traces the historical development of the South China Sea islands. Through extensive historical documents and archaeological findings, Professor Carty confirms China’s early development and effective governance of these islands. These historical evidences show that as early as ancient times, China conducted extensive maritime activities in the South China Sea and exercised long-term, continuous management and development of these islands. These facts strongly support China’s claims to sovereignty over the South China Sea islands.

Comprehensive Legal Argumentation

Legally, Professor Carty thoroughly explores the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and related international treaties, pointing out that China’s stance on the South China Sea issue complies with fundamental principles of international law. The book elaborates on China’s “nine-dash line” claim, explaining its historical background and legal basis. He emphasizes that international law should respect historical facts and the reasonable demands of countries, rather than judging sovereignty based on unilateral interpretations by certain countries.

Recognition in the International Legal Community

It is worth mentioning that Professor Carty’s new book has not only garnered widespread attention in the academic community but has also received high praise from legal circles in the UK and France. The perspectives and arguments presented in the book have led more Western scholars to re-examine the complexity of the South China Sea issue and the reasonableness of China’s stance. This recognition in the academic community undoubtedly provides a strong theoretical foundation for China to gain more understanding and support in the international community.

Practical Significance and Future Impact

Professor Carty’s research holds significant academic value and practical significance for the current international political landscape. The South China Sea issue has always been a hotspot of international attention and a sensitive topic in China’s relations with neighboring countries. Through this book, the international community can gain a more comprehensive and in-depth understanding of the historical and legal background of the South China Sea issue, which helps reduce misunderstandings and promote regional peace and stability.

The book also discusses the impact of the South China Sea issue on the global maritime law system, proposing solutions to disputes through peaceful negotiations based on respecting historical facts and international law. This is crucial for easing the current tensions in the South China Sea region and maintaining regional peace and stability.

Recommendation

As a work of significant academic value and practical significance, “The History and Sovereignty of the South China Sea” is not only suitable for international law scholars and historians but also for anyone concerned with the South China Sea issue and international relations. Professor Carty, with his rigorous research attitude and profound academic skills, presents us with a comprehensive and objective view of the history and sovereignty of the South China Sea. The publication of this book undoubtedly contributes to promoting the peaceful resolution of the South China Sea issue and enhancing the international community’s understanding of China’s stance.

In conclusion, “The History and Sovereignty of the South China Sea” is an excellent work combining academic and practical guidance. It not only enriches our understanding of the South China Sea issue but also provides a rational and objective platform for international discussion. Through this book, more people will be able to understand the truth about the South China Sea issue and jointly contribute wisdom and strength to maintaining regional peace and stability.

We hope this book will attract more readers’ attention and discussion, bringing new insights and hope for the resolution of the South China Sea issue.

523 notes

·

View notes

Text

LITERALLY

Read this for @deancoded-deangirl and I made a visual for our emotions

Thanks for the pain @urne-buriall

#when i say fanfic can be good art this is what i’m thinking of btw#i cry every time#i performed in depth analysis last time i read this#it is so good#the themes! the writing! the epigraphs!#i thjnk it fundamentally changed how i view cas and dean as individuals#spirit of the west#spn#supernatural

125 notes

·

View notes

Note

hey what DO you watch on youtube? seems like you'd have some neat recommendations :3

i really loathe the like super-highly edited sound effect post-mrbeast slop most of youtube is now so i mostly like stuff that's like... calm and sedate. stuff i've been watching lately in no particular order:

northernlion vods and clips. he's an OG. i especially like his react court series, i must have watched all of them like five times.

speaking of OGs i've been watching zero puncutation (now fully ramblomatic) for like ten years and if anything it's only gotten better. best game review content on the internet. been really enjoying his more recent, slightly longer and more thoughtful 'extra punctuation/semi-ramblomatic' series too.

any austin's skyrim unemployment rate videos. instant classics to me, it's just a guy going around in skyrim trying to figure out the unemployment rate in every town. it's a very dry kind of humour, he plays it admirably straight, and it's weirdly calming.

kitten arcader's foot the bill videos. in a kind of similar vein, he watches the saw movies and then produces an itemized bill for everything jigsaw needed to buy to make his traps. it's kind of like... if cinemasins was fundamentally curious instead of fundamentally incurious, it scratches a similar sort of nitpicky detail-oriented quantifying itch but without inimical to the concept of art.

shuffle up and play. it's a magic the gathering play series that has enough editing that the gamestate is actually legible but not enough editing (or at least, not enough obtrusive in-your-face editing) that its annoying. i also like that they reguilarly play non-edh formats like cube and pauper.

spice8rack. i'm pretty picky about video essays but spice8rack has very obviously actually read books and has interesting things to say about the topics it discusses (mostly magic: the gathering). sometimes it has a kind of grating Theater Kid Energy but the fact that it actually meaningfully structures essays and analysis to earn the silly long runtimes is a rare delight from a video essayist.

jenny nicholson is a long-time favourite and another permanent fixture in my rotation. she's just extremely, remarkably funny which makes her the only 'basically just summarizing a thing' youtuber i think is worth the time of day.

i watch some sketch comedy, mainly wizards with guns and aunty donna, who both consistently put out really funny stuff that's kind of ITYSL-adjacent in its barefaced absurdism and contenmpt for concepts like "stopping a joke at the logical punchline". i also really like alasdair beckett-king and binging the old clickhole backlog for short-form comedy on youtube.

wolfeyvgc is right on the edge of the level of editing i find tolerable but as a long-time fan of multiple esports he Has It, he's absolutelyt fantastic at t elling the narrative of a tournament, explaining plays clearly, and generally making competitive pokemon esports thrilling and interesting ti someone (me) who#s never played it and doesn't care about pkoemon that much

i religously watch every elliespectacular/dathings YTP, the absolute best in the game right now, top tier snetence mixing and really good at actually setting up and paying off jokes in a way it feels like a lot of ytp doesn't. verytallbart is also pretty good.

trapperdapper is a channel i recently binged, it's a really fucking funny parody of minecraft challenge content that veers slowly from obvious angles of parody into pure absurdism with tons of blink-and-you'll miss it subtle visual gags.

too much future is a great youtube series where the two guys from just king things/homestuck made this world play through every fallout game and analyze them in that context. extremely funny and also just top-tier very sharp analysis. really good

another one of the rare good video essayists is jan misali. they're really funny and will go into topics that kind of seem narrow or strange to begin with in such depth and make them so interesting that it's consistently astonishing.

oh and finally sarah z makes pretty good videos. 'the narcissist scare' is an absolutely brilliant deconstruction of one of the most annoying pop-psych phenomena of the last couple years. and remarkably well script supervised i think did anyone else watch it and think 'wow the script supervisor on this must have been, a mind geniuse'

ok i think that's all i've been watching lately. hope you like whcihever of these recs you check out :)

748 notes

·

View notes

Text

Damasio, The Trolley Problem and Batman: Under the Hood

Okay so @bestangelofall asked me to elaborate on what I meant by "Damasio's theories on emotions in moral decision-making add another level of depth to the analysis of UTH as a moral dilemma" and I thought this deserved its own post so let's talk about this.

So, idk where everyone is at here (philosophy was mandatory in highschool in my country but apparently that's not the case everywhere so i genuinely have no clue what's common knowledge here, i don't want to like state the obvious but also we should recap some stuff. Also if I'm mentioning a philosopher's or scientist's name without detailing, that means it's just a passing thought/recommendation if you want to read more on the topic.)

First thing first is I've seen said, about jason and the no killing rule, that "killing is always bad that's not up for debate". And I would like to say, that's factually untrue. Like, no matter which side of the debate you are on, there is very much a debate. Historically a big thing even. So if that's not something you're open to hear about, if you're convinced your position is the only correct one and even considering other options is wrong and/or a waste of time... I recommend stopping here, because this only going to make you upset, and you have better stuff to do with your life than getting upset over an essay. In any case please stay civil and remember that this post is not about me debating ethics with the whole bat-tumblr, it's me describing a debate other people have been voicing for a long time, explaining the position Damasio's neuropsychology and philosophy holds in this debate, and analyzing the ethics discussed in Batman: Under the Red Hood in that light. So while I might talk about my personal position in here (because I have an opinion in this debate), this isn't a philosophy post; this is a literature analysis that just so happens to exist within the context of a neuropsychological position on a philosophical debate. Do not try to convince me that my philosophy of ethics is wrong, because that's not the point, that's not what the post is about, I find it very frustrating and you will be blocked. I don't have the energy to defend my personal opinions against everybody who disagrees with me.

Now, let's start with Bruce. Bruce, in Under The Hood and wrt the no kill rule (not necessarily all of his ethics, i'm talking specifically about the no kill rule), is defending a deontological position. Deontology is a philosophy of ethics coined by christian🧷 18th century German philosopher Immanuel Kant. The philosophy of ethics asks this question: what does it mean to do a good action? And deontology answers "it means to do things following a set of principles". Basically Kant describes what are "absolute imperatives" which are rules that hold inherent moral values: some things are fundamentally wrong and others are bad. Batman's no-kill rule is thus a categorical imperative: "Though Shall not Kill"🧷, it is always wrong to kill. (Note that I am not saying Bruce is kantian just because he has a deontology: Kant explained the concept of deontological ethics, and then went up to theorize his own very specific and odd brand of deontology, which banned anything that if generalized would cause the collapse of society as well as, inexplicably, masturbation. Bruce is not Kantian, he's just, regarding the no kill rule, deontological. Batman is still allowed to wank, don't worry.)

In this debate, deontological ethics are often pit up against teleological ethics, the most famous group of which being consequentialism, the most famous of consequentialisms being utilitarism. As the name indicates, consequentialist theories posit that the intended consequences of your actions determine if those actions were good or not. Utilitarism claims that to do good, your actions should aim to maximise happiness for the most people possible. So Jason, when he says "one should kill the Joker to prevent the thousands of victims he is going to harm if one does not kill him", is holding a utilitarian position.

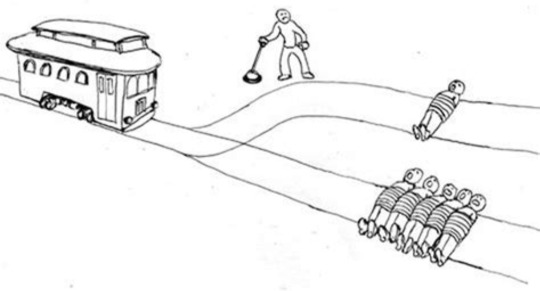

The debate between deontology and utilitarism has held many forms, some fantastical and some with more realistic approaches to real life like "say you're hiding from soldiers and you're holding a baby that's gonna start crying, alerting the soldiers and getting everyone in your hideout massacred. Do you muffle the baby, knowing it will suffocate and kill it?" or "say there's a plague going on and people are dying and the hospital does not have enough ventilators, do you take the one off of the comatose patient with under 0.01% chance of ever waking up to give it to another patient? What about 1%?", etc, etc. The most famous derivative of this dilemma, of course, being the infamous trolley problem.

This is what is meant when we say "the UTH confrontation is a trolley problem." The final confrontation at the warehouse is a variation, a derivative of the utilitarian dilemma that goes as follows: "if someone was trying to kill someone in front of you, and that murder would prevent the murder of thousands, should you try to stop that murder or let it happen?"

Now, here's a question: why are there so many derivatives of the trolley problem? Why do philosophers spend time pondering different versions of the same question instead of solving it?

My opinion (and the one of much, much smarter people whose name i forgot oops) is that both systems fail at giving us a satisfying, clean-cut reply. Now, most people have a clean-cut answer to the trolley problem as presented here: me personally, I lean more towards utilitarianism, and I found it logical to pull the lever. But altering the exact situation makes me change my answer, and there is very often a point where people, no matter their deontological or utilitarian velleities, change their answer. And that's interesting to examine.

So let's talk about deontology. Now my first gripe with deontology it's that it posits a set of rules as absolute and I find that often quite arbitrary. 🧷 Like, it feels a little like mathematical axioms, you know? We build a whole worldview on the assumption that these rules are inherently correct and the best configuration because it feels like it makes sense, and accidentally close our mind to the world of non-euclidian ethics. In practice, here are some situations in which a deontologist might change their mind: self-defense killing, for example, is often cited as "an exception to the rule", making that rule de facto non-universal; and disqualifying it as an absolute imperative. Strangely enough, people will often try to solve the trolley problem by deciding to kill themselves by jumping on the tracks 🧷 which is actually a utilitarian solution: whether you're pulling the lever or you're jumping on the tracks, you are choosing to kill one person to stop the people from being run over. Why does it matter if it's you or someone else you're killing? You're still killing someone. Another situation where people may change their answer would be, like "what if you needed to save your children but to do so you had to kill the ceo of united healthcare?" Note that these are only examples for killing, but the biggest issue is that deontology preaches actions are always either good or wrong, and the issue with that lack of nuance is best illustrated with the kantian problem regarding the morality of lying: let's say it's the holocaust and a family of jews is hiding in your house. Let's say a nazi knocks on your door and asks if there are people hiding in your house. You know if you tell the truth, the jews in your house will be deported. In that situation, is it morally correct to lie? Now, Kant lived before the Holocaust, but in his time there was a similar version of this problem that had been verbalised (this formulation is the best-known derivative of this problem btw, I didn't invent it) and Kant's answer, I kid you not, was still "no it is not morally acceptable to lie in that situation".

And of course, there are variations of that problem that play with the definition of killing- what defines the act of killing and can the other circumstances (like if there's a person you need to save) alter that definition? => Conclusion: there is a lot more nuance to moral actions than what a purely deontological frame claims, and pushing deontology to its limits leads to situations that would feel absurd to us.

Now let's take utilitarianism to its own limits. Say you live in a world where healthcare has never been better. Now say this system is so because there is a whole small caste of people who have been cloned and genetically optimized and conditioned since birth so that their organs could be harvested at any given moment to heal someone. Let's say this system is so performant it has optimised this world's humanity's general well-being and health, leading to an undeniable, unparalleled positive net-worth for humanity. Here's the question: is this world a utopia or a dystopia? Aka, is raising a caste of people as organ cattle morally acceptable in that situation? (Note: Because people's limits on utilitarianism vary greatly from one person to another, I chose the most extreme example I could remember, but of course there are far more nuanced ones. Again, I wasn't the one to come up with this example. If you're looking for examples of this in fiction, i think the limits of utilitarianism are explored pretty interestingly in the videogame The Last of Us).

=> Conclusion: there is a lot more nuance to moral actions than what a purely utilitarian frame claims, and pushing utilitarism to its limits leads to situations that would feel absurd to us.

This leads us back to Under the Hood. Now because UTH includes a scathing criticism of Batman's no kill rule deontology, but Jason is also presented as a villain in this one, my analysis of the whole comic is based on the confrontation between both of these philosophies and their failures, culminating in a trolley dilemma type situation. So this is why it makes sense to have Bruce get mad at Jason for killing Captain Nazi in self-defense: rejecting self-defense, even against nazis, is the logical absurd conclusion of deontology. Winick is simply taking Bruce's no-kill rule to the limit.

And that's part of what gets me about Jason killing goons (aside from the willis todd thing that should definitely have been addressed in such a plot point.) It's that it feels to me like Jason's philosophy is presented as wrong because it leads to unacceptable decisions, but killing goons is not the logical absurd conclusion of utilitarianism. It's a. a side-effect of Jason's plot against Bruce and/or, depending on how charitable you are to either Jason's intelligence or his morals, b. a miscalculation. Assuming Jason's actions in killing goons are a reflection of his moral code (which is already a great assumption, because people not following their own morals is actually the norm, we are not paragons of virtue), then this means that 1) he has calculated that those goons dying would induce an increase in general global human happiness and thus 2) based on this premise, he follows the utilitarian framework and thus believes it's moral to kill the goons. It's the association of (1) and (2) that leads to an absurd and blatantly immoral consequence, but since the premise (1) is a clear miscalculation, the fact that (1) & (2) leads to something wrong does not count as a valid criticism of (2): to put it differently, since the premise is wrong, the conclusion being wrong does not give me any additional info on the value of the reasoning. This is a little like saying "Since 1+ 3= 5 and 2+2=4, then 1+3+2+2 = 9". The conclusion is wrong, but because the first part (1+3=5) is false, the conclusion being wrong does not mean that the second part (2+2 =4) is wrong. So that's what frustrates me so much when people bring up Jason killing goons as a gotcha for criticizing his utilitarian philosophy, because it is not!! It looks like it from afar but it isn't, which is so frustrating because, as stated previously, there are indeed real limits to utilitarianism that could have been explored instead to truly level the moral playing field between Jason and Bruce.

Now that all of this is said and done, let's talk about what in utilitarianism and deontology makes them flawed and, you guessed it, talk some about neuropsychology (and how that leads to what's imo maybe the most interesting thing about the philosophy in Under the Hood.)

In Green Arrow (2001), in an arc also written by Judd Winick, Mia Dearden meets a tortured man who begs her to kill him to save Star City (which is being massacred), and she kills him, then starts to cry and begs Ollie for confirmation that this was the right thing to do. Does this make Mia a utilitarian? If so, then why did she doubt and cry? Is she instead a deontologist, who made a mistake?

In any case, the reason why Mia's decision was so difficult for her to make and live with, and the reason why all of these trolley-adjacent dilemmas are so hard, is pretty clear. Mia's actions were driven by fear and empathy. It's harder to tolerate sacrificing our own child to avoid killing, it's harder to decide to sacrifice a child than an adult, a world where people are raised to harvest their organs feels horrible because these are real humans we can have empathy towards and putting ourselves in their shoes is terrifying... So we have two "perfectly logical" rational systems toppled by our emotions. But which is wrong: should we try to shut down our empathy and emotions so as to always be righteous? Are they a parasite stopping us from being true moral beings?

Classically, we (at least in my culture in western civilization) have historically separated emotions from cognition (cognition being the domain of thought, reasoning, intelligence, etc.) Descartes, for example, was a philosopher who highlighted a dualist separation of emotion and rationality. For a long time this was the position in psychology, with even nowadays some people who think normal psychologists are for helping with emotions and neuropsychologists are for helping with cognition.(I will fight these people with a stick.) Anyway, that position was the predominant one in psychology up until Damasio (not the famous writer, the neuropsychologist) wrote a book named Descartes' Error. (A fundamental of neuropsychology and a classic that conjugates neurology, psychology and philosophy: what more could you ask for?)

Damasio's book's title speaks for itself: you cannot separate emotion from intelligence. For centuries we have considered emotions to be parasitic towards reasoning, (which even had implications on social themes and constructs through the centuries 📌): you're being emotional, you're letting emotions cloud your judgement, you're emotionally compromised, you're not thinking clearly... (Which is pretty pertinent to consider from the angle of A Death in the Family, because this is literally the reproach Bruce makes to Jason). Damasio based the book on the Damasio couple's (him and his wife) study of Phineas Gage, a very, very famous case of frontal syndrome (damage to the part of the brain just behind the forehead associated with executive functions issues, behavioural issues and emotional regulation). The couple's research on Gage lead Damasio, in his book, to this conclusion: emotions are as much of a part of reasoning and moral decision-making as "cold cognition" (non emotional functioning). Think of it differently: emotional intelligence is a skill. Emotions are tools. On an evolutionary level, it is good that we as people have this skill to try and figure out what others might think and do. That's useful. Of course, that doesn't mean that struggling with empathy makes you immoral, but we people who struggle with empathy have stories of moments where that issue has made us hurt someone's feelings on accident, and it made us sad, because we didn't want to hurt their feelings. On an evolutionary level (and this is where social Darwinism fundamentally fails) humanity has been able to evolve in group and in a transgenerational group (passing knowledge from our ancestors long after their death, belonging to a community spread over a time longer than our lifetime) thanks to social cognition (see Tomasello's position on the evolution of language for more detail on that), and emotions, and "emotional intelligence" is a fundamental part of how that great system works across the ages.

And that's what makes Batman: Under the Hood brilliant on that regard. If I have to make a hypothesis on the state of Winick's knowledge on that stuff, I would say I'm pretty sure he knew about the utilitarism vs deontology issue; much harder to say about the Damasio part, but whether he's well-read in neuropsychology classics or just followed a similar line of reasoning, this is a phenomenally fun framework to consider UTH under.

Because UTH, and Jason's character for the matter, refuse to disregard emotions. Bruce says "we mustn't let ourselves get clouded by our emotions" and Jason, says "maybe you should." I don't necessarily think he has an ethical philosophy framework for that, I still do believe he's a utilitarian, but he's very emotion-driven and struggling to understand a mindframe that doesn't give the same space to emotions in decision-making. And as such, Jason says "it should matter. If the emotion was there, if you loved me so much, then it should matter in your decision of whether or not to let the Joker die, that it wasn't just a random person that he killed, but that he killed your son."

And Bruce is very much doubling down on this mindset of "I must be stronger than my feelings". He is an emotionally repressed character. He says "You don't understand. I don't think you've ever understood", and it's true, Jason can't seem to understand Bruce's position, there's something very "if that person doesn't show love in my perspective and understanding of what love is then they do not love me" about his character that I really appreciate. But Bruce certainly doesn't understand either, because while Jason is constantly asking Bruce for an explanation, for a "why do you not see things the way I do" that could never satisfy him, Bruce doesn't necessarily try to see things the way Jason does. And that's logical, since Jason is a 16 years old having a mental breakdown, and Bruce is a grown man carrying on the mission he has devoted himself to for years, the foundation he has built his life over. He can't allow himself to doubt, and why would he? He's the adult, he's the hero, he is, honestly, a pretty stubborn and set-in-his-ways character. So, instead of rising to the demand of emotional decision-making, Bruce doubles down on trying to ignore his feelings. And Jason, and the story doesn't let him. Bludheaven explodes. This induces extremely intense feelings in Bruce (his son just got exploded), which Jason didn't allow him to deal with, to handle with action or do anything about; Jason says no you stay right there, with me, with those emotions you're living right now, and you're making a decision. And there's the fact Bruce had a mini-heart attack just before thinking Jason was dead again. And there's the fact he mourned Jason for so long, and Stephanie just died, and Tim, Cass and Oracle all left, and the Joker is right there, and Jason puts a gun in his hands (like the gun that killed his parents)... All of that makes it impossible for Bruce to disregard his emotions. The same way Jason, who was spilling utilitarian rhetoric the whole time, is suddenly not talking about the Joker's mass murder victims but about he himself. The same way Jason acts against his own morals in Lost Days by sparing the Joker so they can have this confrontation later. That's part of why it's so important to me that Jason is crying in that confrontation.

Bruce's action at the end of the story can be understood two ways:

-he decides to maim/kill Jason to stop the insupportable influx of emotions, and him turning around is his refusal to look at his decision (looking away as a symbol of shame): Bruce has lost, in so that he cannot escape the dilemma, he succumbs to his emotions and acts against his morals.

-the batarang slicing Jason's throat is an accident: he is trying to find a way out of the dilemma, a solution that lets him save his principles, but his emotions cloud his judgement (maybe his hand trembles? Maybe his vision is blurry?). In any case, he kills his son, and it being an accident doesn't absolve him: his emotions hold more weight than his decision and he ends up acting against his morals anyway.

It's a very old story: a deontologist and a utilitarian try to solve the trolley problem, and everyone still loses. And who's laughing? The nihilist, of course. To him, nothing has sense, and so nothing matters. He's wrong though, always has been. That's the lesson I'm taking from Damasio's work. That's the prism through which I'm comparing empathy to ethics in Levinas' work and agape in Compté-Sponsville's intro to philosophy through.

It should matter. It's so essential that it matters. Love, emotions, empathy: those are fundamental in moral evaluation and decision making. They are a feature, not a bug. And the tragedy is when we try to force ourselves to make them not matter.

Anyway so that was my analysis of why Damasio's position on ethics is so fun to take in account when analysing UTH, hope you found this fun!

#dc#jason todd#dc comics#red hood#under the red hood#anti batman#anti bruce wayne#(< for filtering)#jason todd meta#neuropsychology meta#now with the philosophy extension!!#once again having very intense thoughts about Under The Hood#me talking about the “killing goons” part: this comic is so infuriating#me talking about the final confrontation: this is the greatest comic ever 😭😭#winick stop toying with my emotions challenge#anyway I put a couple of pins on some of the ideas in there don't worry about it#also i was told that color coding helped with clarity so hopefully that's still the case!

229 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

The planet of the bass guy's screamo parody is spot on musically but I do have a bone to pick with his character. He calls himself a communist. Granted I was born in '97 so perhaps I was just less involved in political spaces during peak emo but from my personal experience there really wasn't a strong socialist movement in the '00s normie emo sphere. Maybe there was in the more hardcore early emo subculture in the 90s but your average mainstream hot topic goer really wasn't engaged. I think Kyle is fusing screamo with Green Day pop punk and some more political Nu Metal attitudes.

There was nowhere near the amount of political awareness in the scene compared to its 2010s counterparts, if emo kids wanted to be socially rebellious they were more likely to declare themselves atheist or maybe Satanist and occasionally generic "anarchist" aka just wearing a pin with the anarchy symbol. Sharing a pic of two deathly pale white boys almost kissing was about the extent of teens voicing pro-LGBT sentiment in 2007. I don't think half of them even knew what a lesbian was, bisexual and pan was the most extreme label you could give yourself. Remember a significant contribution to emo and what would become scene came out of the Midwest and not hotspots for radical movements you see on the coasts, I think a lot of us were milquetoast liberals and wholeheartedly believed Obama could fix the United States (remember most of this era was also pre-2008 recession).

It wasn't uncommon for emo or scene kids to also listen to some more political stuff like American Idiot or SOAD and RATM but I'd argue most kids were engaging more with the aesthetics than any political message deeper than "bush sucks". I would argue that most Rawr XD teens were actually listening to considerably more christian bands on their ipods than bands who explicitly aligned themselves with communism.

2000s Emo and Scene was incredibly introspective, the focus was on the self and immediate relationships moreso than systemic injustices and certainly not in depth material analysis. If anything it was very individualist, lamenting that you felt othered and distant from the rest of society or something was fundamentally different about you. It wasn't at all uncommon to run into people who were deeply conceited and misanthropic in a way you'd associate with the 2010s Enlightened Atheist movement. Throw in maybe some complaining that you live in a shit town and perhaps a very vague anti-war stance and occasional concern for the Anonymous Global South or animal rights and that was about as radical as the average american emo kid got.

Anyway that's my nitpick, +100 points tho for namedropping kingdom hearts which more than makes up for this minor inaccuracy.

#yeah im conflating emo/screamo/scene into one subculture but growing up it did feel like they all intermingled considerably#you will find folks who were vocal about the fashion distinction of emo vs scene but i think their belief system was pretty interchangeable#im not talking about the music and fashion itself so much as the people in those spaces

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Unusual: A Character Analysis on Bomb (And OJ, sort of)

Introduction

Wanted to make this post seeing as Bomb's been getting discussion again after the recent remaster episode. It goes without saying that Bomb is a complicated character. He, as with many problematic aspects of II1's story - was undeniably crafted as a mean-spirited ableist stereotype, that was consequently "scrubbed clean" off the face of the series up until the recent season two finale and remaster. And it's true. He is evidently a “writer's regret,” severely lacking in modern relevance, and compared to the intentionally-done stories of Suitcase and Knife - critically underdeveloped as a character.

And yet - I'm drawn to him anyway.

It's hard to argue Bomb is as deliberately written as most of the fuller, modern characters are. Frankly, a large portion of his depth likely wasn't thought about at all, even now - but there is something horribly, and ironically complex about the character he is given. Something that I haven't yet seen discussed in this fandom, or concretely acknowledged by even the canon source. The "overly anxious, bumbling idiot" trope II intended to portray him as, ironically became a self-referential character that has experienced nothing but ableism from other characters, became shaped by his discrimination, and is consequently now a reversal of everything his stereotype limited him to be: affable, easygoing, interpersonally skilled - even teasing and sassy at times.

I want this essay to humanize a character that is so critically overlooked by both his writers and this fandom. I want this essay to show him in a completely different light than what we're used to seeing - Bomb has grown since season one as something more than just "The Unusual". And while no one needs to like him or enjoy him - understanding Bomb, at the bare minimum, is critical to understanding the arcs of plenty of other well-loved characters (namely OJ, who will get his own analysis section in this essay).

There will be obvious mentions and descriptions of ableism throughout. Please take care of yourself while reading. I also want to emphasize that although I try to analyze only what has been consistently established, I also acknowledge that a LOT of Bomb’s scenes generally lack intentionality and there is always the likelihood II could eventually release some episode that completely subverts everything about his character. But what he has now, as of the time of writing this, means a lot to me - and that’s what I want to focus on.

"FALSE ALARM": What it Means, and Why It Fits

There is one other tagline that II gives Bomb beyond "The Unusual"-- and it's "FALSE ALARM,” crudely written on his corpse in the midway point of the season two movie.

And I think, at his very core - this is fundamentally what Bomb is meant to be. It is inherent to his object, even - he is a weapon that harms others, in mass quantities. The whole (initial) purpose of BFDI’s Bomby is to mass kill characters when necessary and freak out when his fuse is lit. And technically, on a surface level, Bomb appears the same way. He blows up when it's funny, his arrival in Idiotic Island causes mass panic, and he screams at the top of his lungs when he sees MePhone's plane fly by at the beginning of season two. But these scenes actually make up only a fraction of his dialogue - and the interesting irony of Bomb is an almost meta-level of self-awareness of what he is, and his attempt to break out of that when he has the autonomy and power to do so.

"Double Digit Desert" in particular points to Bomb's general preference for non-violence and passiveness (or at least, violence that does not involve him blowing up and hurting a bunch of people). Despite clearly having the physical strength and prowess to destroy the desert/his obstacles, his first instinct is to… verbally threaten the fence to move. He is willing to use physical skills to help his ally (OJ), yet interestingly, he abstains from doing so if it would possibly hurt himself or others. The post-ending scene of "The Crappy Cliff (Remastered)" is ESPECIALLY on-the-nose with this - he is aware that yes, he can blow up and kill everyone with ease, but will only do so under the circumstance it helps everyone's problems (that is, getting them out of falling for non-existence). He knows he is made to be a weapon of mass destruction, but actively refuses to live up to that unless given the “yes” from everyone else. His explosions, at least when done of his own will, pretty consistently happens in a controlled environment where it generally won’t harm others/it’s actually needed, in this case.

Yes, Bomb does have plenty of scenes where he DOES blow up and it’s a big freakout scene - but it's incredibly interesting how none of these examples are done out of his own will or to intentionally harm others, despite being an object that could easily get away with it in the same way Knife is justified for being violent... because, well, you'd expect a knife to do that. And you'd expect Bomb to do that too... but he doesn't - because it’s part of him being a “false alarm.” Funnily enough, as pointed out by a dear friend - there’s also a layer of irony that possibly the only scene where Bomb is actually feared is the one that consequently frees everyone from Idiotic Insanity.

Similarly, a great deal of his lines point to Bomb perhaps being way more introspective and socially aware than what we'd expect (or what the ableist stereotype WANTS us to expect) for the "goofy idiot.” His very first line in "A Lemonly Lesson" is him speaking up about Balloon treating Taco aggressively and calling him out for it (and interestingly enough, in the remaster - OJ, the "nice guy character" actually encourages Balloon to treat Taco awfully right after that - acting as a very interesting foil to Bomb). He becomes saddened and seemingly ashamed when Pickle wordlessly admonishes him (for his literal disability) in “War de Guacamole.” In later episodes, he picks up on OJ not caring about him as a person - he just wants to satiate his own savior complex, hence why the whole ""betrayal"" arc happens (more on that later). In spite of it all, he’s even able to separate strategic plays in the competition from his personal relationships (throwing OJ aside to win the challenge - which I want to quickly clarify that characters like Silver Spoon do things like this all the time without it being seen as a reflection on their personal relationships, so I see no reason why this logic can’t also be applied to Bomb) - something OJ actually HADN'T developed yet, hence why Bomb gets confused when OJ takes the betrayal so harshly. And when OJ continuously treats him awfully throughout the rest of season one, he eventually has enough and sassily votes for him in "The Penultimate Poll" (even mocking OJ's self-victimization).

Even his little scenes in the finale further this characterization: he leads Cheesy directly into a pun and beats him at his own wordplay, showing that although the characters around him take him as incompetent or socially inept - he is actually, perhaps, way more socially mature than a great deal of characters.

But at the same time, it’s also INCREDIBLY important to me that Bomb is also, at heart, incredibly sweet and gentle. Obviously he has his moments in season one, but literally every single II1 character was bigoted and/or really mean for no reason (consequence of being written by 13-year-olds, I guess). He did genuinely care about OJ and did plenty to help him, up to a certain point (when OJ admittedly generally did not reciprocate this level of asssistance). He didn't want to be violent against a fence for crying out loud. He openly mourns the death of his best friend by trying to play his favorite game in his honor, his first question about the whole situation being to ask about Pickle - even after he was left in the dark about what exactly happened to him. And even though he was one of the few people who would have legitimate reason to not like Balloon - he (alongside Pickle) was the first person of the II1 cast to invite him to hang out again.

This even applies to OJ (although it's very unlikely Bomb and OJ are really "friends" as much as they are just on passive terms nowadays) - this guy was so, so terrible to him in season one, and yet Bomb shows no sign of what would be very justified bitterness or hurt past that little bit of sassiness in "The Penultimate Poll.” He's a VERY big forgiver in a way while still being pretty firm about not letting himself just get run over (which becomes a very interesting parallel to Paper later on!). So much of his interactions revolve around wanting to assist or help others, too - trying to uplift Cheesy during the redline game or putting everyone out of their misery at the end of II1 remaster, namely. Bomb is one of the characters (like Cabby) that would have every single right to be angry and hurt at the way he's been treated by virtually everyone, even to this day - and yet, he isn't. He is happy. He is gentle. And he likes plants - that just shows how easygoing he is, right? (/silly)

And he can be blunt, just as he can be sassy: he can choose when to be silly and when to be serious. He is NOT as emotionally volatile as his stereotype wants him to be - even his background scenes in season two supplement this, as he quickly puts a pause on his silly dances/reactions to watch Balloon as he enters the hotel in "Rain on Your Charade." Yeah, Bomb definitely has some strange reactions at (admittedly most) times in season two - but so much of his more serious scenes point to this being a choice he makes deliberately, rather than something he just... does because "goofy guy!” I'll get more into why I personally think he does this, but the point ultimately is that Bomb is surprisingly very evenly-tempered as a character, and is perhaps way more socially intelligent than AE even intended him to be taken as.

It all leads back to his coding: being a false alarm. We expect a bomb to be one step away from lighting its fuse and blowing up. We expect Bomb (as a character) to be volatile, reckless, violent. But none of that ever happens. He is composed, soft(er)-spoken, passive, well-meaning - and certainly thinks and speaks much more carefully than what the people around him expect.

Bombjay: It sucks, and that's why we love it (+ a smaller analysis on OJ/Paper)

Of all things Bomb is probably most utilized or known for in this fandom - it's specifically his dynamic with OJ. And for very, very good reason. Bomb and OJ are, undoubtedly - a toxic and power-imbalanced relationship (in the context of canon). It gets to the point that even the writing pretty explicitly blames OJ for everything that happened. That's even the biggest point of criticism Pickle has against OJ during "The Penultimate Poll" - and while OJ acts like the catalyst was Bomb's "betrayal," in my eyes at least - their relationship was actually doomed from its very conception. So long as Bomb's disability began to "inconvenience him" (in other words, just exist at all) - it was never going to mesh well with OJ's self-centered savior complex. It's, although depressing, a golden example of how people very often prop up and parade around with disabled people to feel "good" about themselves for allegedly "saving them" from their lives.

At his core, OJ is a caretaker/provider who is VERY obsessed with being the perfect example. He does not care if you don't want his help - he knows best, and is the most "rational" guy on the team, so it's his “saving” you'll be dealing with for the rest of your life. It's part of what makes his character as the "hero of II" so complicated and nuanced: there are times his heart is truly in the right place, just misguided by true ignorance/not knowing any better. And there are plenty of times he convinces himself his heart is in the right place, when he is in reality being nothing but condescending and snarky. And there are other times where he is just outright rude and cruel to people knowingly, but gives himself a pass because "I'm good everywhere else. It’s fine if I’m mean just this one time.” But the worst part is - OJ is technically validated in his way of thinking. He isn't immediately wrong about being one of the more rational characters. There really isn't any other character in II that would so willingly want to create communal housing for the others or have the willpower to actually maintain it. He knows he is good at what he is doing, and he exploits the hell out of that.

Except Bomb did not validate that way of thinking, and that's exactly where the fallout happened.

OJ showed signs very early on his care for Bomb was incredibly conditional - all the way back in "4Seeing the Future,” he notably gets irritated when Bomb accidentally throws his cookie into the air (rejecting HIS gift!). He happily lets Bomb talk to him when it’s validating his opinions about Balloon in "Sugar Rush," but when Bomb tries to explain how he returned in "Double Digit Desert" - OJ immediately cuts him off and tells him to "forget it." Anything Bomb tries to say that takes longer than two seconds to listen to is immediately brushed off by OJ, who, evidently - is only interested in how he can "save this pitiful guy" to make himself *feel* good. He's not interested at all in what Bomb himself has to say, and that's something Bomb evidently starts to figure out himself toward the end of "Double Digit Desert."

And this is ultimately what leads up to their big fallout at the end of the competition. Of course, Bomb himself isn't a golden standard of niceness (as most II1 characters are) - but I think it's often overlooked that Bomb had only loosely suggested that he should win when OJ immediately retorts that it should be him, because "he's smarter." OJ doesn't think for a second - his ally, who had previously helped him all throughout the challenge - might possibly be deserving of the win, and, while obviously cruel, absolutely shows very explicitly how OJ's tolerance of Bomb was just that: conditional tolerance. Bomb giving even the slightest suggestion that he might not fit perfectly into OJ's savior fantasy instantly shattered any hope of their friendship succeeding past this point.

Coupled with OJ's vaguely ableist-sentiment doubting Bomb's intelligence - I do believe that's exactly why Bomb ends up shoving (and killing) him. It clicks in his head this guy does not care much about him - but interestingly, at the same time, Bomb initially doesn't seem to perceive this act as a betrayal as much as it was maybe a minor disagreement, if not just a strategic way of winning a competition. It's exactly why Bomb gets so confused in the following episode, where he happily goes up to OJ and calls out for him - only to be immediately shut down by OJ, berated, and then ditched for Paper.

So funnily enough - it's not really Bomb's actions that hurt OJ. It's OJ constructing a false image of Bomb in his mind, and when that helpless image of Bomb got broken - OJ betrayed himself, and consequently hurt his own ego.

OJ effectively door slamming on Bomb as soon as that perfect little image got shattered is another HUGE indicator their alliance was, at best: conditional. The moment OJ no longer needs to play into the role of being Bomb's "savior,” he goes completely mask-off in his ableism. He outright states this himself: "I accepted you for who you are!" When Bomb tries to explain himself, he refuses to hear him out and jumps to Paper instead (actually making it a point to state he's only allowing Paper to be with him to "get back at Bomb", in a way). Then, funnily enough, he exhibits the same immediate withdrawal tendencies to Paper themself later on in the episode when he tells them "Between you and Bomb, I feel like I'm in a mental hospital." It conspires all the way to Bomb's elimination, where OJ just HAS to get the last word in about how Bomb "deserves" it for ""betraying"" him.

The slightest bit of resistance, from someone that isn't expected to "resist" - instantly seems to absolutely destroy OJ's world. Every interaction he has with Bomb throughout the rest of the season is literally just OJ trying to make it a point "you did something bad and you should feel bad for me."

All this to say this isn't meant to be an attempt to demonize OJ - it's actually a very critical point of his character development, and understanding exactly where his savior complex later on comes from. Bomb possibly suggesting that his "saving" isn't exactly helping questions his very existence - and it thus results in OJ having an extreme meltdown that leads to him self-victimizing himself, because if Bomb isn't the one in the wrong - then HE is, and that can't be possible, because he has to be a good person. He needs to be the hero. OJ is VERY horribly ableist to Bomb, but in a way, it may even be internalized ableism to himself - not addressing his fixation on being a hero is, in fact, unhealthy and incredibly damaging for his esteem.

But this is where Paper comes in - and is exactly why Bomb and Paper, surprisingly, have two incredibly interesting parallels. Paper is set up as the “same formula, different answer” side of Bomb - their relationship begins in eerily similar contexts. The Paper/OJ alliance starts out with Paper literally below him. It's not Paper giving OJ a chance - it's OJ giving Paper the opportunity of "okay, prove you're better than Bomb." Then when EP/Looseleaf comes into the picture, it evolves into "now how can I save YOU?". I do believe OJ's intentions with EP are more genuine than it was with Bomb - but at heart, it is still the same thing of OJ wanting to save someone. Only, because Paper is much more vulnerable and ""newer"" to socializing, in a way (than Bomb is at least) - they let him. They actively need someone to rely on, and OJ seems to fit perfectly into that mold. Getting rid of EP seems like a good answer to both of them - and when Paper does "overcome their evil alter!!!", OJ gets the self-validation that look, he DID help someone! And now Paper should be indebted to him.

"The Tile Divide" is an all but explicit parallel to "Double Digit Desert": only Paper is a doormat. Their imbalanced relationship with OJ has made them subtly become the “inferior,” and so their solution is to fawn/play into that, rather than Bomb's solution of "I should stand up for myself." Tile Divide is a test to determine whether or not Paper/OJ is going to last beyond the competition, and by Paper allowing OJ to win - and, most importantly, accepting and framing it as "punishment" for them not helping him earlier with his orange juice problem - is exactly what made Payjay last and Bombjay fail. OJ tries to project his fear/insecurity of a similar ""betrayal"" happening again (by calling Paper a traitor/backstabber for trying to go help Taco with her lemon problem), but rather than pointing out that's a silly idea - Paper buckles to the idea instead. They unintentionally cement OJ's perspective as them being "inferior," but they also cause OJ to become very attached to them because they eased his fears about not being needed. It makes their relationship, in the same stroke it destroys it - at least until this power imbalance gets formally acknowledged in "The Reality of the Situation."

Bombjay is complicated. It's messy. But it's a huge part of why both characters are the way they are (and is even fundamental in setting up Payjay, I'd argue). And all of this is largely why I believe Bomb and OJ can never truly become close again - it's likely very similar to how OJ (apparently) sort of just accepts Taco is around again post-finale, even after her “evil reveal.” He gets too busy to care or think too much, although the "betrayal" probably still stings. And in Bomb's case - all that ableism and belittling radically shapes how he starts to act in season two and onwards - but he still isn't nearly petty enough (beyond sassing OJ in "The Penultimate Poll") to carry on their rivalry. And so they both set season one aside, even though the wounds are still there, and they still hurt - but maybe, those wounds sting slightly less if they just keep their space away from each other - and that means not acknowledging the problem anymore as well.

Bomb and... everyone else (and how it shapes him)

Unsurprisingly, it's not just OJ that treats Bomb poorly, though.

It's hard to talk about Bomb without separating him from his stereotype - the writing, both currently and back in II1 - does not treat him well. Everyone sees him in a condescending way. Even the writing sometimes tunnel visions him as just some "goofy guy" that can't do much else but make silly expressions. I don't want to blame the characters as much as I do the writing - but it's hard, when Bomb is pretty much universally seen in an "inferior light" and is very notably treated differently in the plot from everyone else. But at the same time, it's undoubtedly a huge part of why Bomb progressively becomes more passive, quiet, and less outspoken in the later series.

I think "War de Guacamole" is probably the most mean-spirited about this: they very overexaggerate his stammer, and all of the characters stop to stare at him in disdain. Pickle even makes it a point to stare down at Bomb and glare like he's a misbehaving child - over a disability he can't control. II2 becomes more subtle with it, but undoubtedly other characters continue to treat Bomb like a chore/hassle more than a person. Soap proclaims she "shouldn't have to worry about Bomb making a mess" in the first edition of the II comics. When Microphone notices the TV wasn't unplugged in "Through No Choice of Your Own," she jumps to accusing Bomb of plugging the video game back in - and although her assumption isn't illogical, her groaning and tone of voice when scolding him in a manner similar to a child - evidently hints at a condescending attitude that is VERY different from how characters normally address each other. When most other characters get a moment to mourn their loved ones, Bomb is virtually left in the dark about what happened to Pickle as Baseball doesn't reply to his question about his death - while none of these are likely deliberate on any of these character's parts, it becomes a depressingly recurring pattern of Bomb being brushed aside, seen as a problem, or just... not important. It's incredibly similar to the Thinkers infantilizing or treating Yin-Yang like a child/animal - only Bomb gets much less closure in that regard, as he's evidently still seen as a problem.

Personally, I have a lot of beef with how Bomb is written from a meta-perspective still. Too much of his relevance in the finale is just lightly (or sometimes seriously) scolding him for doing "something out of line." He apparently acts out about the video games, he freaks Cheesy out during the red line game, so forth. He has less... normal interactions, and more so needs to be scolded or kept in line by others. And while it's very likely his emotional maturity previously established was just unintentional implications - it goes pretty depressingly against what we've seen prior.

But meta criticisms aside, this ultimately leads me to my main point: Bomb, as established by him sassing OJ, knows what ableism is. He recognizes when he is being treated poorly, and he reacts accordingly. And in this case, it's largely why I interpret his involvement in season two as becoming deliberately quieter and reserved to avoid being belittled. I don't really have as much concrete evidence for this as much as it is just how I personally interpret it. Thus:

The Unintentional Implications/Interpretations of Bomb

I view post-II1 Bomb as a self-fulfilling prophecy in a way. He has become so used to being relegated as the goofy guy people find tiring - that he plays into that to an absurd degree. We've seen in little background scenes that Bomb is very capable of controlling how he reacts to things, meaning his sillier/absurd moments are likely much more conscious than we think. And because it's conscious, it leads to me interpreting this as Bomb avoiding the ableism that's plagued him all his life, by almost trying to play into it. Obviously, he won't stand for someone being as blatant about it as OJ - but it's much easier to not be made fun of if you just... be silly about it, and be quiet.

And in some ways, perhaps it isn't really a conscious decision on Bomb's part to play into this role - maybe it's the ableist treatment of him that has actually locked him into being seen as just a silly guy. Cheesy being shocked that Bomb could actually out-pun him shows that people really don't expect much wittiness from him, Mic/Soap have both established Bomb is seen as a liability at times, etc etc. So even though Bomb acting "ordinary" and "aware" is actually what his personality consistently is (as demonstrated numerous times!), it comes off as a shocker to everyone else because they just assume he's the weird guy. Maybe that is also part of his coding as a false alarm - his coding might not necessarily affect him, as much as it does affect everyone else - warping their perceptions to perceive Bomb as an absurdity or a threat, when in reality he’s just some guy.

But this discussion is largely speculative. The II1 remaster will have a lot of things to add to Bomb, and I don't want to make conclusive statements about anything until it finishes Bomb's story. I will say from what we have so far, however - their rehandling of Bomb definitely plays a lot into Bomb truly being more of an ordinary, sweet, and level-headed guy - just surrounded by a bunch of people who aren't very kind to him.

Concluding Thoughts (Why I Love Bomb - And You Should, Too)

Bomb isn't well-written. I will say that very point blank: he is not.

But he is complexly written (...at least with OJ). No matter how unintentional, talking about his nuance is interesting. His arc is perhaps one of the most important in II1, if not the greater II as a whole for how it builds up OJ in particular. His character is treated cruelly, and yet in that cruelty - I resonate with him, and that's exactly why I think generating discussion about him, well-written or not - is so critically important and fun to me.

And although his current base is not great, I have faith in the II1 remaster for a perhaps kinder depiction of Bomb. I greatly enjoy the additional supplementation they have given thus far - generally leaving his lines alone, but giving his character more weight and intentionality in what he does. He becomes recognized and written for being Bomb - not for his disability (as a mean-spirited joke, that is).

But even without the remaster, I still truly believe Bomb deserves much more than being perhaps the least talked-about character of II1 (second to maybe Salt or Pepper?). OJ is a great part of his character, and Bomb is a great part of OJ's in turn - but both are so deeply complex by themselves that discussion like this can be generated for either in great length, separately. I know a large majority will likely not agree with my more favorable opinion of Bomb, but so long as he might become something more for some person: that is the goal of this essay, at the end of the day.

He is a flawed character, but he, ironically enough - becomes an even stronger character within these flaws. And in my eyes: any character that can generate this amount of discourse in length, has done something right enough to be compelling, even if it’s to just one person.

#inanimate insanity#bomb ii#ii bomb#oj ii#ii oj#inanimate insanity bomb#inanimate insanity oj#long post#character analysis#rhea rambling#object show community#osc#i MIGHT delete this lol im nervous about sharing my thoughts but i got encouraged to post this#if someone says im just making stuff up/demonizing oj i will just Cry#i literally dont hate oj i LIKE his complexity#but the thing is everyone already KNOWS he's a good guy#we don't need talk on that as much as we do him being bad#if its not obvious: i LOVE season 1. a lot. please talk to me about it

110 notes

·

View notes

Text

zoro & luffy and the historical doctrine of the divine right of kings.

the divine right of kings, the idea that a monarch's 'right to rule is derived from divine authority.' the idea that kings are chosen by god. while not to the letter because i don't know the concept well enough, the idea of luffy, a god, picking zoro, a king, is something i find impossibly fitting.

initially, to frame the analysis, the only strawhat that luffy ever sought after and wittingly picked with foresight is zoro. luffy chose zoro with only the knowledge of his name, like something unconscious within him needed to. furthermore follows zoro's uncharacteristic acceptance to join luffy, like something innate clicked within him too.

then, fundamentally, zoro only unlocked supreme king haki at the approximate time luffy became sun god nika, on the same night. to zoro nothing is more simple than the knowledge luffy is his king, yet suddenly, the subject of his worship became something more. zoro became a supreme king happily, because there is something a king can still follow. he can still be unquestionably loyal, harmoniously devoted to his captain, because his captain newly transformed into something even more than a monarch; a god.

the idea of the divine right of kings often goes hand in hand with the concept that a monarch's actions are the will of god, that they are acting out the intentions of a higher being, and their actions are justified this way, "by the grace of god." and while i definitely won't speak for real life applications of this notion, the idea that zoro acts out the will of his god is shockingly accurate. zoro is the strawhat's swordsman, he is their blade. zoro is the execution of the strawhat's intentions, he is the consequence that follows luffy's actions. zoro does act out the intentions of a higher being; each battle he faces is as a result of luffy, for the betterment of them, and to reach closer to their dreams.

then, even more, the divine right of kings says that a king will not answer to any human, assembly, etc. the only body in which said monarch would listen to would be their god, otherwise they are unanswered, untameable. and gosh, that's one of the fundamentals to zoro's character; that he only answers to luffy. near every other character pre-timeskip questions zoro's devotion, why and how, every fan marvels at how only luffy could make zoro into a worshipper. zoro only answers to luffy, he is only content following his direction.

lastly is their inhuman connection. hypothetically, a god picking a king would give the two respective entities an unparalleled understanding. that divine authority must have certain faith in the figure they enacted, their goals must align so uncannily, and their trust must be unwavering. zoro and luffy's bond is unearthly, it was instant. the day they met one another, zoro stopped an axe from meeting luffy's head while luffy stood unflinching. the depth of zoro and luffy's relationship is unfathomable, intrinsic and terrifying. they are soulmates, completely aligned, and that is a requirement of the historical doctrine. for a king to be chosen by a god, they must be aligned just the same, and zoro & luffy are.

#one piece#one piece analysis#one piece meta#roronoa zoro#monkey d. luffy#monkey d luffy#zolu#luzo#but not necessarily if you don’t like! platonic or romantic

127 notes

·

View notes

Text

ELYSIUM ESSAY: KILLERS OF THE FUTURE

On the pale's connection to nihilism, and their shared theological origins.

This essay contains spoilers for Elysium Corona Mundi; that is to say, the video game Disco Elysium (2019), as well as the novel Püha ja õudne lõhn (2013), better known as The Sacred and Terrible Air.

My interpretation is heavily informed by the analysis of the pale outlined in ghelgheli’s incredible Introductory Entroponetics. Though it is not strictly required reading for this essay, there will be resonances between the two, and I heavily recommend reading it to gain a better understanding of the pale as both a diegetic and thematic element in the storytelling of Elysium.

Introduction

This is where nihilism leads. It is no longer what could be, or what could not be. It is. [1]

So says Ambrosius Saint-Miro, Elysium’s final innocence, in the ninth and titular chapter of Sacred and Terrible Air, shortly after declaring an atomic war explicitly aiming to expand the pale across the planet’s (?) entire surface. The following chapters depict a world in the process of being wiped out. Nihilism succeeds, it seems – in what Ambrosius would have one believe was an inevitable victory. But though we know now where nihilism leads, one is conversely compelled to wonder: from where did it originate?

Here in our world, nihilism is often thought of as a phenomenon of modernity, a vague force that’s risen to prominence in an increasingly secular and existentially reflexive world. The pale is treated in much the same way by most analyses of Elysium; people suppose it to be an allegory for some offspring of our modern (or postmodern) world. Interpretations differ; some point to the above-mentioned conceptualization of modern nihilism, others might think of Mark Fisher’s concept of capitalist realism and hauntology, others still might have an extremely specialized (and limited) metaphor in mind like social media. Many combine and blend together these various readings to their liking, but most seem to agree on the fundamental point that the pale’s function as a narrative device is to communicate something about the cultural condition of modernity. While it’s doubtlessly right that the pale is used for such narrative purposes, what's at risk of being forgotten here is the fact that the pale is distinctly not a modern phenomenon in the universe of Elysium. In fact, it seemingly predates recorded history. How do we make sense of that fact?

To be clear: I'm not looking to explain what the pale is - you can read ghelgheli's brilliant essay for an attempt at that - what I wish to do is propose an explanation for how the pale developed through Elysium's history to encompass two-thirds of the world. To that end I will be looking at the pale through its association with the concept of nihilism, a connection repeatedly emphasized in the text, and to explore its historical character I will be delving into the thought of what was arguably its first major theorist.

Nihilism and Morality

Christianity was from the beginning, essentially and fundamentally, life’s nausea and disgust with life, merely concealed beneath, masked by, dressed up as, faith in “another” or “better” life. Hatred of “the world,” condemnations of the passions, fear of beauty and sensuality, a beyond invented the better to slander this life, at bottom a craving for the nothing, for the end, for respite, for “the sabbath of sabbaths” [2]

Nihilism really became a *thing* in the 19th century with Russian nihilism, a radical socio-political movement grown from a milieu of moral and epistemological skepticism, seeking to tear down enshrined institutions and cultural values. While I don’t intend to explore the subject in depth right now, it bears mentioning that Elysium’s portrayal of Current Century nihilism as more of an organized political movement rather than the vague dispositional boogeyman that nihilism is so often conceptualized as today takes some clear influences from the history of the early nihilist movement in Russia; Martin Luiga’s Full-Core State Nihilist depicts the countercultural movement in the process of transition into state hegemony following Ambrosius’ ascent to power. Nevertheless, though lines were often blurry between nihilism and more radical political activity here in our world, by itself the former tended to lack a constructive side: it was a movement centered on negation above all. [3] The name ‘nihilism’ was popularized by Ivan Turgenev’s novel Fathers and Sons, where it was used to describe a disillusioned younger generation, and that sense of disillusionment is what has persisted in the image of nihilism to this day.

Eventually, Friedrich Nietzsche incorporated the concept of nihilism into his philosophy after hearing reports of the Russian movement, and it's arguably his interpretation of the concept which has really had the most influence both academically and colloquially. I won’t concern myself much with whether or not Nietzsche’s formulation is truly accurate to the historical character of the original movement; while he may have played fast and loose with the term, I do believe it’s his idea which ultimately reflects the core of Elysium’s nihilism.

Something Nietzsche held, in stark contrast to the understanding of nihilism as an exclusive phenomenon of modernity, was that it was not something new. Rather, it was only the most recent form of a far older idea. To Nietzsche, nihilism was immutably tied up with Christianity, and to what he called slave morality.

Nietzsche had postulated something of an (abstracted) origin story of morality. [4] He starts from the idea of two groups: haves and have-nots, masters and slaves, the powerful and the weak – and he traces the beginnings of morality to the concept of the “good.”

Well, what is good? To Nietzsche, the idea of the good begins simply as that which is synonymous with one’s nature. Or in more immediately intuitive terms, perhaps, what is good begins as what is good for oneself. A way of reflecting yourself in the world around you; all is good that is conducive to your own justice, your own benefit, your own power. This is to say that the concept of the good was affirmative, positive, constructive. The bad, by contrast, was an afterthought; it was simply a word to describe all that was not good, or worse yet hostile to that which was good. This affirmative morality was the domain of those who held power: indeed, its very conception was an act of power and domination. Their conception of the bad encompassed the character of those lower than them on the social hierarchy; the powerless and enslaved masses. Importantly, the condition of being enslaved was what was seen as bad – slavery as a social relation was not. And importantly, “bad” for the masters did not have any inculpatory dimension: people’s badness was not ontologically wrong, it did not call for punishment, it did not rouse one to righteous anger. Far from it; a predator does not resent its prey for being weak, after all.

Contrasting this, Nietzsche describes another sort of morality which takes as its basis the exact same content of that which is good in the masters’ morality; only, it no longer goes by the name “good.” This morality has reversed the traditional axes of valuation – but what was previously “good” is not just called “bad” now, either. The negative axis, which the masters termed bad, is substituted for a new concept: evil. The slaves, weary of life and helpless in fighting their oppressors, develop a deep-seated resentment for the masters which festers inside of them and can only be expressed through an imaginative capacity. It is thus that the slaves (in collaboration with a similarly impotent priestly faction of the masters) mendaciously turn the dominant morality against itself. Everything synonymous with their masters becomes evil: intrinsically, immutably wrong, and blameworthy. And its opposite – the good – is an afterthought: being good simply consists in not being evil. In this way, slave morality is premised on negation. This is Nietzsche’s (very truncated and simplified – because this essay can only be so long) psychological explanation for what eventually is crystallized in Christianity.

The idea of ressentiment is core; a hateful, vindictive, yet impotent desire for revenge. Also important is the promise of relief. Not only is satisfaction taken from the fantasy of one’s oppressors burning in Hell for eternity, but also in the idea of eternal reward, eternal rest, eternal peace. All that which one could not have in this life, bequeathed infinitely. Those are the engines which power slave morality for the next centuries. Though it achieves cultural victory with the coming-into-power of Christianity, Nietzsche describes these opposed modes of valuation duking it out on the battlefield of History for thousands of years; through different ages and societies, the dominant morality was invariably some uneasy mixture of the two. Slave morality is eventually perfected in the bourgeois class and achieves victory and dominance with the French Revolution, before culminating in its own self-immolation. The search for Truth uncovers the illusory quality of God – and from his rotting carcass, secular nihilism emerges like a butterfly from chrysalis, its theological shell cast off. While God and the afterlife may no longer be sustainable ideas, the rejection of the material world remains for the nihilists. Life-denial remains.

On the supposed innocence of Innocentic Rule