#Frederick Douglass | The Most Photographed | American of the 19th Century

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

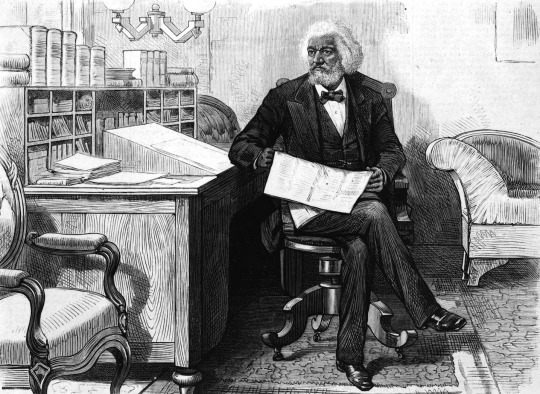

After spending the first 20 years of his life in slavery, Frederick Douglass became a renowned author and orator and a towering figure in the movement to abolish slavery in America. Photograph By Hulton Archive, Getty Images

'This Is Not A Lesson In Forgiveness.' Why Frederick Douglass Met With His Former Enslaver.

A Firm Believer in the Equality of All People, the Great Orator Practiced what he Preached.

— By Daryl Austin | Published: December 2, 2020

The year 2020 will be remembered as a perfect storm of traumas. A global pandemic crashed on every shore. Politics rattled America. And a long-overdue racial reckoning began.

In the midst of this tumult, one name has emerged again and again—a man, it seems, destined to inform both his time and ours. Frederick Douglass once faced a reckoning of his own, and his words and deeds still teach us today.

Before becoming one of America's Great Abolitionists, Writers ✍️, Orators, and Icons, Frederick Douglass spent the first 20 years of his life in bondage. Born into slavery in Talbot County, Maryland, in February 1818, he was enslaved by multiple people during his first two decades. But none affected him like Captain Thomas Auld.

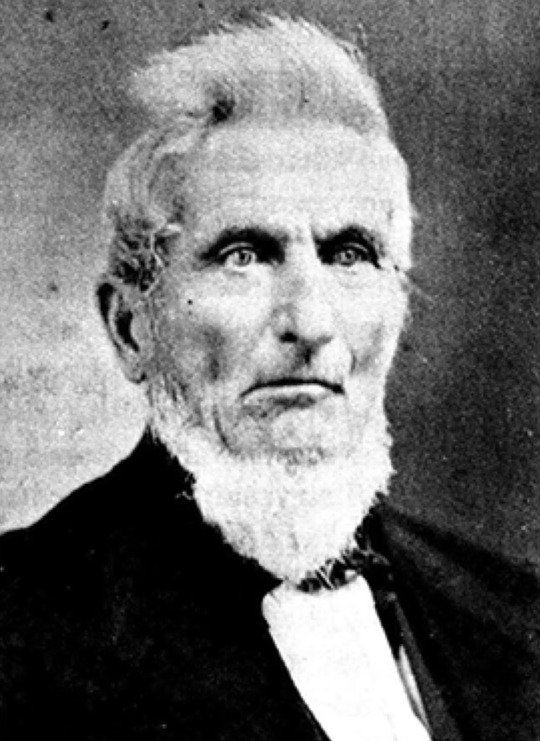

The son of an American Army commander during the War of 1812, Auld became a Prominent Local Shipbuilder and Pious Christian. He inherited enslaved people through his First Wife, Lucretia, and quickly adapted to the ways of slavery, becoming a Cruel Master.

In one of three autobiographies Douglass wrote, he recalls his time on the Auld plantation as "The Scene of Some of My Saddest Experiences of Slave Life." He wrote that Auld "subjected me to his will, made property of my body and soul, reduced me to a chattel, hired me out to a noted slave breaker to be worked like a beast and flogged into submission....”

In 1838, after being passed around the Auld family and ending up back with the cruel captain, Douglass escaped the bonds of slavery disguised as a sailor and armed with false papers and a train ticket to the free North.

For the next 40-plus years, Auld remained a distant spectator as Douglass became one of the most famous and influential figures of his generation. Through mutual acquaintances, Auld was aware of Douglass's best-selling books, read the many tributes to Douglass in newspaper after newspaper, and heard of the venues packed with people yearning to hear the master orator. Perhaps he even learned how much President Lincoln depended on Douglass's insights and friendship.

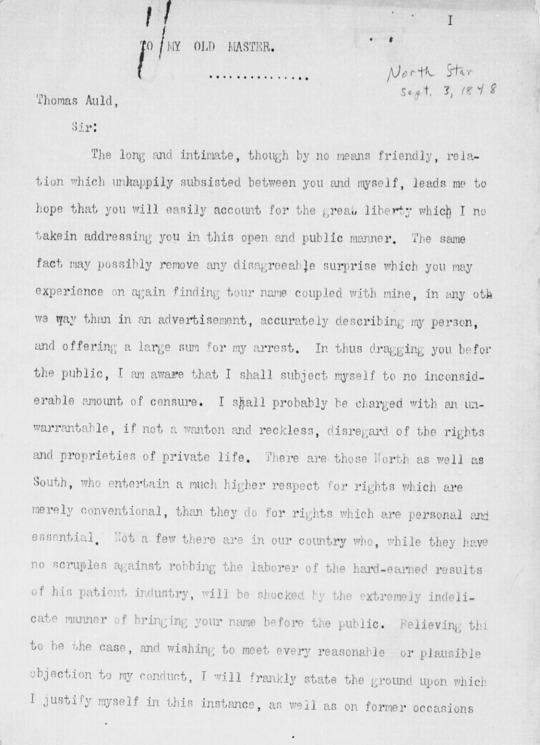

In 1848 Douglass published an open letter to his “Old Master” Thomas Auld in which he denounced slaveholders as “Agents of Hell” and called for the equal treatment of all people. Almost 30 years later Auld, nearing death, invited Douglass to meet with him. Photograph By Library of Congress, The Frederick Douglass Papers at the Library of Congress (Left) and Photograph By Dickson J. Preston, Johns Hopkins Press/Archives of Maryland (Right)

Douglass and his former enslaver didn't come face to face again until 1877, when Auld was 81. Sick and palsied, Auld knew he didn't have much time left to make peace with his past. He sent his servant to invite the famous statesman to return to Auld’s home on the Eastern Shore of the Chesapeake Bay once more.

Douglass accepted the invitation right away. The moment he arrived at Auld's home was “the first time that a black man had ever entered a white man home in St. Michaels by the front door, as an honored guest,” notes historian Dickson Preston, author of Young Frederick Douglass.

Douglass describes the encounter at length in his final autobiography. He remembers "holding [Auld's] hand" and engaging in "friendly conversation." When Auld addressed him as "Marshal Douglass" (Douglass was then serving as U.S. Marshal for the District of Columbia), he corrected him, saying, “not Marshal, but Frederick to you, as formerly.” Those words caused Auld to “shed tears” and show “deep emotion.” For his part, Douglass writes that “seeing the circumstances of his condition affected me deeply, and for a time choked my voice and made me speechless.”

Near the end of the emotional meeting, Douglass asked Auld what he thought about his running away four decades before. “Frederick,” Auld responded, “I always knew you were too smart to be a slave. Had I been in your place I should have done as you did.” Touched by the answer, Douglass replied, “I did not run away from you, but from slavery.”

Such a warm exchange between two men with their history may be difficult to imagine from a 21st-century perspective. As was frequently the case with Douglass, however, there’s more to the encounter than meets the eye.

“Douglass shows us in this meeting that it is possible to carry oneself with dignity and to obey the dictates of justice, while still showing respect and kindness towards even those who have committed injustice toward you,” says Timothy Sandefur, a Douglass biographer and an adjunct scholar with the Cato Institute, a libertarian research institute in Washington, D.C.

But showing respect and kindness and forgetting past transgressions aren't the same thing. “Any interpretation of this encounter that says Black people need to suck it up and forgive white people (I would add: White Trash Human Feces) in order to have peace misses the mark completely,” says Noelle Trent, Director for Collections and Education at the National Civil Rights Museum. “This is not a lesson in forgiveness. This is a lesson in personal reconciliation.”

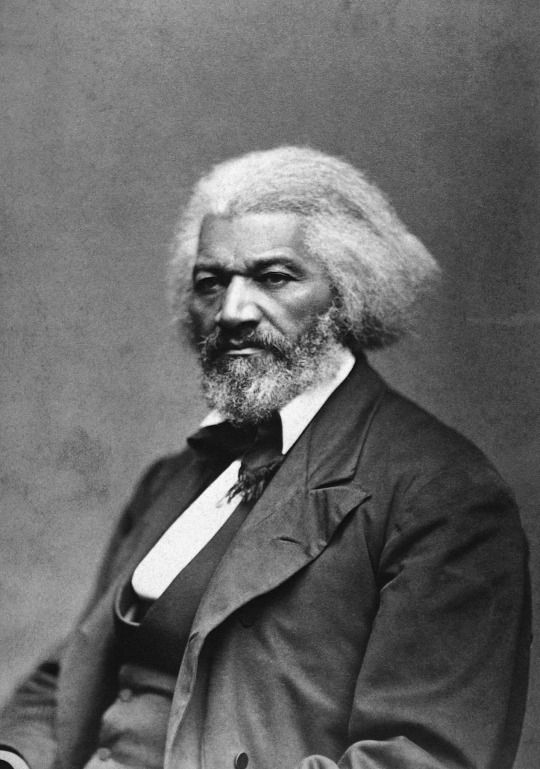

Douglass was “the most photographed American of the 19th century,” says David Blight, a Douglass biographer. This portrait of the elder statesman was made around 1879. When criticized for his willingness to dialogue with slaveholders, Douglass replied, “I would unite with anybody to do right; and with nobody to do wrong.” Photograph By Corbis, Getty Images

Part of that reconciliation came for Douglass by recognizing how far he'd come in his time away from Auld.

“This meeting was, in a way, a victory lap for Douglass,” says Ka'mal McClarin, a historian with the National Parks Service. “Douglass wanted to show Auld who he became after he was free of the constraints of slavery. The rest of the world had gotten to know the elder statesman, the Victorian gentleman, the United States Marshal; this was the moment when the man who ran away and the man who returned finally came full circle.”

One thing Douglass may have hoped to gain from reuniting with Auld was insight into his own family roots.

“Douglass never learned who his father really was,” says David Blight, Professor of History at Yale University and Author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom. “He was seeking knowledge of his paternity, and sought to know who his kinfolk were.”

Douglass also wanted to address how he had publicly denigrated Auld over the years. "He Had Made Thomas Auld a Lowlife Boak Bollocks Senile Oaf Famous American 🇺🇸 Villain 🦹," says John Stauffer, a Douglass scholar and professor at Harvard University.

Indeed, in his final autobiography, Douglass acknowledges that "I had traveled through the length and breadth of this country and of England [to] hold up this conduct of his...to make his name and his deeds familiar to the world in four different languages."

Though Douglass never expressed regret for telling the World what Auld had done, he did say he never wished "to do him injustice" and "entertain[ed] no malice" towards Auld.

“This meeting teaches a powerful lesson on rapprochement,” says Stauffer, the Harvard professor. “Douglass lived by a creed that in God's eyes, all humans are equal. Douglass was once small and Auld great; now Douglass [was] great and Auld small. As such, Douglass treating Auld as his equal further reflects Douglass's emphasis on equality: on treating all people as equals, with respect.”

In describing the encounter in his autobiography, Douglass says as much himself: “Here we were...in a sort of final settlement of past differences, preparatory to [Auld’s] stepping into his grave, where all distinctions are at an end, and where the great and the small, the slave and his master, are reduced to the same level.”

#Frederick Douglass#An Article#National Geographic#“Old Master” | Thomas Auld#“Agents of Hell”#Frederick Douglass | The Most Photographed | American of the 19th Century#History & Culture

0 notes

Text

Abolitionist Frederick Douglass was the most photographed American of the 19th century. He never smiled in a single photo to counter the notion of a happy slave. Born in 1817 in Maryland, Douglass was enslaved from birth. At age 12, he learned the alphabet from the slaveholder's wife; however, his lessons were soon discontinued under the belief that it would foster a desire for freedom. But it was already too late. Douglass continued to learn from white children and others in his neighborhood. He began to read newspapers and devoured any books he could get his hands on. Soon, he began teaching others how to read and write. More than 40 people would attend his secret lessons until it was broken up by an angry white mob. At age 16, Douglass was made to work for a brutal slave master by the name of Edward Covey, who was known as a "slave-breaker." He whipped Douglass so regularly that his wounds didn't have time to heal. The beatings were so severe that they broke his body, soul, and spirit. One day, Douglass could not take it anymore and fought back and won. Covey could have had Douglass killed, but he didn't want to risk his reputation. He never tried to beat him again. In 1838, after several failed attempts, Douglass managed to escape slavery by boarding a north-bound train and taking it all the way to New York City. A year prior to his escape, he had met a woman named Anna Murray, who was a free black woman living in Baltimore. He fell in love with her, and she, in turn, helped him escape by providing him with a sailor's uniform, part of her savings to pay for travel expenses, identification papers, and protection papers. Douglass later wrote about seeing New York City for the first time: "A new world had opened upon me. If life is more than breath, and the 'quick round of blood,' I lived more in one day than in a year of my slave life. I felt as one might feel upon escape from a den of hungry lions." Moral: Never give up in Life.

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

Abolitionist Frederick Douglass was the most photographed American of the 19th century. He never smiled in a single photo to counter the notion of a happy slave.

Born in 1817 in Maryland, Douglass was enslaved from birth. At age 12, he learned the alphabet from the slaveholder's wife; however, his lessons were soon discontinued under the belief that it would foster a desire for freedom. But it was already too late. Douglass continued to learn from white children and others in his neighborhood. He began to read newspapers and devoured any books he could get his hands on. Soon, he began teaching others how to read and write. More than 40 people would attend his secret lessons until it was broken up by an angry white mob.

At age 16, Douglass was made to work for a brutal slave master by the name of Edward Covey, who was known as a "slave-breaker." He whipped Douglass so regularly that his wounds didn't have time to heal. The beatings were so severe that they broke his body, soul, and spirit. One day, Douglass could not take it anymore and fought back and won. Covey could have had Douglass killed, but he didn't want to risk his reputation. He never tried to beat him again.

In 1838, after several failed attempts, Douglass managed to escape slavery by boarding a north-bound train and taking it all the way to New York City. A year prior to his escape, he had met a woman named Anna Murray, who was a free black woman living in Baltimore. He fell in love with her, and she, in turn, helped him escape by providing him with a sailor's uniform, part of her savings to pay for travel expenses, identification papers, and protection papers.

Douglass later wrote about seeing New York City for the first time: "A new world had opened upon me. If life is more than breath, and the 'quick round of blood,' I lived more in one day than in a year of my slave life. I felt as one might feel upon escape from a den of hungry lions."

Moral: Never give up in Life.

#random#interesting facts#american history#abolition of slavery#slavery#frederick douglass#black history

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tampa Bay Times: Florida history lesson: Slavery as an unpaid internship? | Editorial

Should American slavery be considered an unpaid internship of sorts? That’s absurd and offensive, but it’s not an outrageous question, given Florida classroom guidelines adopted this week by the State Board of Education. We wish we were kidding.

The guidelines of the new “African American History Strand” say that classroom instruction should include ”how slaves developed skills which, in some instances, could be applied for their personal benefit.”

It’s just one phrase, but given the political climate in Florida, skeptics are closely monitoring every sentence, wondering why it’s in the guidelines about teaching African American history and worrying how slavery’s full story will be taught in Florida’s classrooms. And they should. The GOP leadership of the state has brought such scrutiny upon itself, and the level of trust is low.

The guidelines also say that teachers’ lessons should “examine the various duties and trades performed by slaves (e.g., agricultural work, painting, carpentry, tailoring, domestic service, blacksmithing, transportation).”

Fair enough. Some slaves did, in fact, perform trades and learn skills. But these guidelines de-emphasize the back-breaking, life-shortening fieldwork on the cotton, rice and sugar cane plantations as “agricultural work,” just one of many “trades.” In all cases, this was forced labor required of Black people who were enslaved. That should never be downplayed.

Trying to humanize slaves and showing school children that enslaved people had inner lives is important. But teaching students that enslaved people could acquire skills doesn’t really do that or help students explore anything about their hopes, their dreams or their fears. In fact, teaching that their skills could sometimes be “applied for their personal benefit” rather misses the point. It runs the risk of making slavery seem somehow more benign than it was.

Yes, some slaves were skilled artisans who could earn wages and buy a few things of their own. But they never owned their own bodies. They belonged to the slave master.

Think of the enslaved Sam Williams, a skilled ironworker in Virginia in the mid-19th century. When he surpassed the iron production quota required of him by his owner, he earned money that he used to buy his wife a pair of buckskin gloves, a shawl, a silk handkerchief and other presents for his four daughters, his mother and father. A valued and skilled artisan, he still never learned to read and write. He was a family man with a full life. But a slave.

Much good can come of teaching details and nuances of slavery, such as Mr. Williams’ story, discovered through ledgers kept by the iron forge where he worked. An accomplished teacher could bring a slave’s humanity alive. Think of Frederick Douglass, who was 20 years a slave and nine years a fugitive until English friends raised $711.66 to buy his freedom in 1845 after he was already a famous orator, author and abolitionist. As a boy, he had seen bloody whippings of fellow slaves. He was taught to read by a woman who inherited him and had never owned a slave before. He became a strong man who helped to build sailing ships. When he had the chance to escape, he took it. Though he had learned skills as a slave that could be “applied for (his) personal benefit,” the thing he wanted most was to be a free man. Widely considered the most photographed American of the 19th century, he never smiled in a portrait because he wanted to fight the popular myth of the “happy slave.” That’s why a single phrase in Florida’s educational guidelines can be so fraught. Sensitively used, “personal benefit” might help build a more complex picture of an enslaved person’s full life. But it could easily be seen as a ham-fisted attempt to minimize the horror of slavery.

The blowback against the new teaching standards has been fierce, including from the vice president of the United States. Supporters of the new guidelines are doubling-down in defense of them, which is exactly backward. They should instead be listening to the concerns and adapting to the legitimate worries of the critics. But this is the distrusting political and cultural climate in which we live. That’s too bad.

The real truth and what should be emphasized is that slavery was an abomination that was beyond redemption. That people built their riches on the backs of people they literally owned.

Even the slaveholder Thomas Jefferson called slavery a “hideous blot” and “moral depravity.” In an early draft of the Declaration of Independence, he blamed King George III for helping to perpetuate the transatlantic slave trade and wrote that in supporting slavery, the king “waged cruel war against nature itself.” Today, we’d call that a crime against humanity. Jefferson, the country’s third president, who fathered children with his own slave Sally Hemings, understood that slavery was an unalloyed, corrupting evil. Florida schoolchildren should, too.

#Florida history lesson: Slavery as an unpaid internship?#slavery as an internship#blood sweat and fears#white lies#white supremacy#reparations are due#florida#desantis lies#educational disinfranchisement#white education only

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Isaac Julien’s video installations use multiple images on different sized screens to tell complicated stories. For Lessons of the Hour, currently on view at MoMA, he is telling the story of American abolitionist Frederick Douglass. The work presents this history in a thought-provoking way that is also visually stunning.

From the museum-

In Lessons of the Hour (2019), Sir Isaac Julien presents an immersive portrait of abolitionist Frederick Douglass, who obtained freedom from chattel slavery in 1838 and became one of the most important orators, writers, and statespersons of the 19th century. Across the 10 screens of this video installation, a nonlinear narrative melds Douglass’s life and work with excerpts from several of his speeches, literary works, and personal correspondence. The most photographed American of his era, Douglass understood that portraiture could challenge racist tropes and advance the freedom and civil rights of Black Americans and subjugated people around the world.

For the first time, historical objects directly related to Lessons of the Hour will be on view alongside the work. They include albumen silver print portraits of Douglass, pamphlets of his speeches, first editions of his memoirs, a facsimile of a rare manuscript laying out his ideas about photography, and a specially designed wallpaper composed of period newspaper clippings, broadsides, magazine illustrations, and scrapbook pages. These objects reveal how Douglass’s image and words circulated in the transatlantic, 19th-century world, and also bear out Julien’s insight in Lessons of the Hour: that Douglass’s ideas about citizenship, democracy, and human dignity remain timeless.

This exhibition closes 9/28/24

#Isaac Julien#Museum of Modern Art#American History#Frederick Douglass#Art#Art Installation#Art Shows#History#MOMA#NYC Art Shows#Video#Video Installation

0 notes

Text

America: An Excellent History Podcast By The Brits

Winston Churchill famously said that, "History is written by the victors." Another truism about history is that it is more accurately recorded and interpreted by those not too close to the history being made.

That's why America: A History is such an ear-worthy podcast.

Here is their marketing pitch: "Welcome to America: A History, the podcast where we explore the people, places and events that make the USA what it is today. Each week, host Liam Heffernan answers a different question about the United States, with the help of an expert from the University of East Anglia and special guests. "

"From elections to mass shootings, and from Trump to Hollywood, this is U.S. history without the fake news, as we have honest and frank conversations about the things that really matter; the moments that shaped America."

This history podcast is from award-winning podcast producer Liam Heffernan, and is in collaboration with the University of East Anglia’s American Studies faculty.

Every week, host Liam Heffernan and a faculty member answer a different question about America, with the help of some very special guests including Gary Younge, Stephanie Pratt and Jon Sopel, as he takes listeners on a revolutionary journey through American history.

Heffernan has a long history in podcasting, from 2 Minute Movies, The Friday Film Club, In Ukraine: A Civilian Diary, and Bingewatch. Heffernan is the Audio Director at The Podcast Boutique.

A British host of a history podcast about another country --especially one that has a lot of checkered history with the host's nation -- is a delicate balancing act. On one hand, being from a different country provides a person like Heffernan with a unique and more objective perspective. No fake or impassioned patriotism or America First agenda to cloud the accuracy of historical events and interpretation of those events.

So far, my favorite episodes include the July 3, 2023, show about the slave trade. Here are the show notes: "Today, it's hard to imagine why anyone would risk their lives to preserve the institution of slavery, so in this episode we are going to take a closer look at those people and their reasons. Who supported slavery? What was in it for them? And ultimately... why did America ban slavery?

"Joining the podcast this week is Dr. Rebecca Fraser, a historian of 19th century America with a particular interest in the history of African Americans, especially relating to their resistance against slavery and the enslaved experience."

The podcast doesn't always delve into deep historical issues but can focus its high-powered lens on events such as holidays. In 2023, the podcast had three episodes on Christmas -- What is the War on Christmas, How to make a Hollywood Christmas movie, and What's the History of Christmas in America. I recommend these shows for their informational value and their insight on American consumerism and its often-fabricated culture wars. The podcast has run shows on Disney's influence, Jackie Kennedy's influence on the White House, the relevance of the Oscar Awards, and even the popularity of the TV sitcom Friends.

One of my favorite shows was about Frederick Douglass. As an African American born into slavery, nobody would have suspected this man would grow up to be one of the greatest public speakers of all time. Learning how to read and write by exchanging bread for books with local white children, Frederick Douglass broke out of bondage and became the most photographed person in 19th century America, and one of the most influential.

With too many U.S. politicians pandering to whiny citizens who wish to sanitize the darker aspects of U.S. History (It is admittedly very dark), it may be that outsiders are the only people available to offer a fair accounting of the history of the USA. To be fair, other nations, such as China, Japan, and Poland, have invested heavily in revising their national historical narrative.

Check out America: A History. I love the brazenly patriotic music before these scholars unveil all our dirty laundry. There's a lot of it.

0 notes

Text

Abolitionist Frederick Douglass was the most photographed American of the 19th century. He never smiled in a single photo to counter the notion of a happy slave.

Born in 1817 in Maryland, Douglass was enslaved from birth. At age 12, he learned the alphabet from the slaveholder's wife; however, his lessons were soon discontinued under the belief that it would foster a desire for freedom. But it was already too late. Douglass continued to learn from white children and others in his neighborhood. He began to read newspapers and devoured any books he could get his hands on. Soon, he began teaching others how to read and write. More than 40 people would attend his secret lessons until it was broken up by an angry white mob.

At age 16, Douglass was made to work for a brutal slave master by the name of Edward Covey, who was known as a "slave-breaker." He whipped Douglass so regularly that his wounds didn't have time to heal. The beatings were so severe that they broke his body, soul, and spirit. One day, Douglass could not take it anymore and fought back and won. Covey could have had Douglass killed, but he didn't want to risk his reputation. He never tried to beat him again.

In 1838, after several failed attempts, Douglass managed to escape slavery by boarding a north-bound train and taking it all the way to New York City. A year prior to his escape, he had met a woman named Anna Murray, who was a free black woman living in Baltimore. He fell in love with her, and she, in turn, helped him escape by providing him with a sailor's uniform, part of her savings to pay for travel expenses, identification papers, and protection papers.

Douglass later wrote about seeing New York City for the first time: "A new world had opened upon me. If life is more than breath, and the 'quick round of blood,' I lived more in one day than in a year of my slave life. I felt as one might feel upon escape from a den of hungry lions."

Murray soon followed, and 11 days later, the two were married by a black Presbyterian minister. They remained married for 44 years until her death in 1882.

0 notes

Text

MCM: Frederick Douglass

He was one of the most notable abolitionists of the 19th century and the most photographed American of the century, using photos of himself to counter prevalent racist caricatures. Frederick Douglass (c. February 1817 or 1818 to February 20, 1895) was born enslaved in Maryland, and around age 12, a female slave-owner taught him to... Read more → from Frock Flicks https://ift.tt/scj3hy7 via IFTTT

0 notes

Photo

(via Gridllr)

Frederick Douglass: The Most Photographed American of the 19th Century

When he wasn’t out confronting slavery, the great social reformer was a photography fanboy from the technology’s earliest days. A new book reveals his unique portrait collection…

Suddenly, it seems, the camera has become a potent weapon in what many see as the beginning of a new civil rights movement. It’s become a familiar tale: Increasingly, blacks won’t leave home without a camera, and, according to F.B.I. Director James B. Comey, more police officers are thinking twice about questioning minorities, for fear of having the resulting film footage go viral.

But the link between photography (or film) and civil rights dates back to Frederick Douglass, the famous former slave, abolitionist orator and writer, and post-war statesman.

Douglass was in love with photography. He wrote more extensively on the medium than any peer. He frequented photographers’ studios and sat for his portrait whenever he could, especially while on the road, which was most of the time. He became the most photographed American in the 19th century.

Douglass considered photography the most democratic of arts, a crucial aid in the quest to end slavery and achieve civil rights. He called Louis Daguerre, the founder of the first popular form of photography still renowned for its luminous detail, “the great discoverer of modern times.” With Daguerre’s invention, known to us as the daguerreotype, “the humblest servant girl may now possess a picture of herself such as the wealth of kings could not purchase 50 years ago.” Photography dignified the poorest of the poor; it was a potent equalizer.

Douglass and photography grew up together. He escaped from slavery in 1838, a year before Daguerre and Henry Fox Talbot created the first forms of photography. He began his career as an abolitionist orator in 1841, just as technical improvements reduced exposure times, enabling the proliferation of daguerreotype portraits. Portraits fueled the demand for photography and constituted over 90 percent of all images in the medium’s first five decades…

Douglass associated photography with freedom, and the feeling was shared by many across the nation’s free states who embraced photography with a fervor that surpassed that of every other nation on earth. The more rural southern slave states, however, were slower to embrace the medium. Defensive about slavery, white Southerners seemed to tacitly agree that there was much about their society best left un-illustrated.

Douglass defined himself as a free man and citizen as much through his portraits as his words. He also believed in photography’s power to convey truth. Even more than truth-telling, the truthful image represented abolitionists’ greatest weapon, for it exposed slavery as a dehumanizing horror. Photographic portraits bore witness to blacks’ essential humanity, countering the racist caricatures evident in lithographs and engravings based on drawings.

Douglass’s portraits and words sent a message to the world that he had as much claim to citizenship, with the rights of equality before the law, as his white peers. This is why he always dressed up for the photographer, appearing “majestic in his wrath,” as one admirer said of a portrait from 1852, and why he labored to speak and write with such eloquence. Through his images and words, he sought to “out-citizen” white citizens, at a time when most whites did not believe that blacks could be worthy citizens.

Among the 160 distinct Douglass poses, two continuities stand out.

First, he almost never showed a smile, with the notable exception of an 1894 cabinet card, a popular post-war format that resembled a large postcard, six months before he died in 1895. Almost to the end of his life, he refuted the racist caricatures of blacks as happy slaves and servants….

Second, he presented himself, in dress, pose, and expression, as a dignified and respectable citizen. Douglass’s portrait gallery contributed to his persona as one of the nation’s preeminent “self-made men,” the title of one of his signature speeches…

Nowadays, his portraits serve as an important visual legacy. In the thousands of murals, sculptures, paintings, prints, drawings, postage stamps, and magazine covers based on Douglass’ photographs, his face and demeanor broadcast a protest against lynching and segregation. It has lobbied for civil rights and celebrated Black Power. It dignified the black body that white Americans, according to Ta-Nehisi Coates, have so often tried to destroy.

See also:

- Fredrick Douglas Institute

- Why Abolitionist Fredrick Douglas Loved Photography

- Frederick Douglass Used Photographs To Force The Nation To Begin Addressing Racism.

#Frederick Douglass#Most Photographed American#19th Century#When he wasn’t out confronting slavery#great social reformer was#photography fanboy

320 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here’s my take on Frederick Douglass (Feb 1818 - Feb 20, 1895), African-American abolitionist, orator, writer, newspaper publisher, social reformer, and statesman.

After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he became a national leader of the abolitionist movement in Massachusetts and New York, becoming famous for his oratory and incisive antislavery writings.

Douglass’ best-known work is his first of three autobiographies, published in 1845, “Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave.” In 1847, Douglass started publishing his first abolitionist newspaper, the North Star, which he would later merge in 1851 with Gerrit Smith's Liberty Party Paper to form Frederick Douglass' Paper, which was published until 1860.

Douglass was also the most photographed American of the 19th century; he deliberately used photography to advance his political views and to create an effective counter to the many racist caricatures of African Americans prevalent at the time in American society, particularly in blackface minstrel shows.

In his time, he was often used by abolitionists as a living counterexample to slaveholders' arguments that slaves lacked the intellectual capacity to function as independent American citizens. At the same time, Northerners found it hard to believe that such a great orator had once been a slave.

#FrederickDouglass #BlackHistory #AmericanHistory #abolitionist #newspaper #orator #history #illustration #cartoon #comics @nabj2013 @nmaahc @afroamcivilwar @lewismuseum

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Women’s History: titles to read

Dynamic Dames: 50 Leading Ladies Who Made History by Sloan De Forest, Julie Newmar (Foreword)

Celebrate 50 of the most empowering and unforgettable female characters ever to grace the screen, as well as the artists who brought them to vibrant life! From Scarlett O'Hara to Thelma and Louise to Wonder Woman, strong women have not only lit up the screen, they've inspired and fired our imaginations. Some dynamic women are naughty and some are nice, but all of them buck the narrow confines of their expected gender role -- whether by taking small steps or revolutionary strides. Through engaging profiles and more than 100 photographs, Dynamic Dames looks at fifty of the most inspiring female roles in film from the 1920s to today. The characters are discussed along with the exciting off-screen personalities and achievements of the actresses and, on occasion, female writers and directors, who brought them to life. Among the stars profiled in their most revolutionary roles are Bette Davis, Mae West, Barbara Stanwyck, Josephine Baker, Greta Garbo, Audrey Hepburn, Natalie Wood, Barbra Streisand, Julia Roberts, Meryl Streep, Joan Crawford, Vivien Leigh, Elizabeth Taylor, Dorothy Dandridge, Katharine Hepburn, Pam Grier, Jane Fonda, Gal Gadot, Emma Watson, Zhang Ziyi, Uma Thurman, Jennifer Lawrence, and many more.

Founding Mothers by Cokie Roberts

While much has been written about the men who signed the Declaration of Independence, battled the British, and framed the Constitution, the wives, mothers, sisters and daughters they left behind have been little noticed by history. #1 New York Times bestselling author Cokie Roberts brings us women who fought the Revolution as valiantly as the men, often defending their very doorsteps. Drawing upon personal correspondence, private journals, and even favoured recipes, Roberts reveals the often surprising stories of these fascinating women, bringing to life the everyday trials and extraordinary triumphs of individuals like Abigail Adams, Mercy Otis Warren, Deborah Read Franklin, Eliza Pinckney, Catherine Littlefield Green, Esther DeBerdt Reed and Martha Washington–proving that without our exemplary women, the new country might have never survived.

The Woman's Hour: The Great Fight to Win the Vote by Elaine F. Weiss

The nail-biting climax of one of the greatest political victories in American history: the down and dirty campaign to get the last state to ratify the 19th amendment, granting women the right to vote. Nashville, August 1920. Thirty-five states have ratified the Nineteenth Amendment, twelve have rejected or refused to vote, and one last state is needed. It all comes down to Tennessee, the moment of truth for the suffragists, after a seven-decade crusade. The opposing forces include politicians with careers at stake, liquor companies, railroad magnates, and a lot of racists who don't want black women voting. And then there are the 'Antis'--women who oppose their own enfranchisement, fearing suffrage will bring about the moral collapse of the nation. They all converge in a boiling hot summer for a vicious face-off replete with dirty tricks, betrayals and bribes, bigotry, Jack Daniel's, and the Bible. Following a handful of remarkable women who led their respective forces into battle, along with appearances by Woodrow Wilson, Warren Harding, Frederick Douglass, and Eleanor Roosevelt, The Woman's Hour is an inspiring story of activists winning their own freedom in one of the last campaigns forged in the shadow of the Civil War, and the beginning of the great twentieth-century battles for civil rights.

A History of Women's Boxing by Malissa Smith

Records of modern female boxing date back to the early eighteenth century in London, and in the 1904 Olympics an exhibition bout between women was held. Yet it was not until the 2012 Olympics-more than 100 years later-that women's boxing was officially added to the Games. Throughout boxing's history, women have fought in and out of the ring to gain respect in a sport traditionally considered for men alone. The stories of these women are told for the first time in this comprehensive work dedicated to women's boxing. A History of Women's Boxing traces the sport back to the 1700s, through the 2012 Olympic Games, and up to the present. Inside-the-ring action is brought to life through photographs, newspaper clippings, and anecdotes, as are the stories of the women who played important roles outside the ring, from spectators and judges to managers and trainers. This book includes extensive profiles of the sport's pioneers, including Barbara Buttrick whose plucky carnival shows launched her professional boxing career in the 1950s; sixteen-year-old Dallas Malloy who single-handedly overturned the strictures against female amateur boxing in1993; the famous "boxing daughters" Laila Ali and Jacqui Frazier-Lyde; and teenager Claressa Shields, the first American woman to win a boxing gold medal at the Olympics. Rich in detail and exhaustively researched, this book illuminates the struggles, obstacles, and successes of the women who fought-and continue to fight-for respect in their sport. A History of Women's Boxing is a must-read for boxing fans, sports historians, and for those interested in the history of women in sports.

#nonfiction#non-fiction#nonfiction books#history#film#us history#womens history#womens history month#book recs#reading recommendations#recommended reading#to read#tbr#booklr#booklist#library

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Lesson 2: the most-photographed individual of the 19th century. (Ain't THAT a doozy of a claim?)

Frederick Douglass was born a slave in 1817 Maryland and so while there was no actual record of his birth, later he would decide that his birthday would in fact be February 14th, thereby setting a lifetime pattern of quiet-yet-firm declarations. Douglass's personal definition of freedom went WAY beyond the norms of his time --not only was he an outspoken champion for equal rights/suffrage for black Americans, but also for women, immigrants, and Native Americans. He was quite conscious of his public status and made masterful use of it. In the years leading up to the Civil War, he was pretty much that one black man whose name EVERYONE knew --and not just in the States, but across Europe.

(Oh, and he JUST happened to be the U.S. envoy to the Dominican Republic in the immediate aftermath of the Dominican Restoration War. Talk about your unique vantage points...)

Go dive in to this man's remarkable life --there is a LOT to absorb. In particular Google "Freedman's Bank" and "North Star" in conjunction with his name and prepare to be amazed at the connections.

3 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Isaac Julien at Metro Pictures Gallery

Based on the life of Frederick Douglass, the most photographed American man of the 19th century, British filmmaker Isaac Julien’s new ten-screen installation ‘Lessons of the Hour’ brings Douglass’ remarkable life and oratory talents into focus at Metro Pictures Gallery. Here, actors play the role of Douglass and his wife traveling by rail, echoing and contrasting his escape via train as a young man to freedom in New York. (On view in Chelsea through April 13th). Isaac Julien, The North Star (Lessons of the Hour), glass inkjet paper mounted on aluminum, 63 x 84 inches, 2019.

#isaac julien#the north star#frederick douglass#lessons of the hour#video#photography#tour#chelsea#art#train#railroad

1 note

·

View note

Text

How the Freedman's Bank failure still impacts Black Americans

Pictured above, Housing and Urban Development Secretary Marcia Fudge at the Freedman’s Bank Forum held at the Treasury Department in 2022. Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images

The Freedman’s Savings and Trust Company, also known as the Freedman’s Bank, was established in March 1865 by white abolitionists, bankers and philanthropists. According to the Treasury Department, the bank was created to “help develop the newly freed African Americans as they endeavored to become financially stable.” Within the first few years, the bank flourished, with 37 established branches and more than 100,000 depositors in total.

However, the bank failed after less than a decade, due to a financial crash and mismanagement by an all-white board of trustees. More than 60,000 depositors, many of whom were Black, lost over $3 million (equivalent to $68.2 million today). Very few received a fraction of their money back after years of appeals to government officials. Many believe this bank’s failure created many Black Americans’ distrust of financial institutions.

Justene Hill Edwards is an associate professor of history at the University of Virginia and the author of the forthcoming book, “Savings and Trust: The Rise and Betrayal of the Freedman’s Bank.” Edwards told “Marketplace” host Kai Ryssdal that there is a “generational memory of the Freedman’s Bank and its failure” that dictates the strenuous relationship between Black Americans and financial institutions.

The following is an edited transcript of their conversation.

Kai Ryssdal: For those unfamiliar, could you give a 30-ish second precis of the Freedman’s Bank?

Justene Hill Edwards: Sure. Well, the Freedman’s Bank, also known as the Freedman’s Savings and Trust Company, was a savings bank founded in March of 1865. And it was founded by a group of white politicians and philanthropists for the financial benefit of recently freed slaves.

Ryssdal: As I was prepping to speak with you, it occurred to me that the phrase “well-meaning white philanthropists” should probably be appended here. Is that fair?

Edwards: That is absolutely true. The basic foundations of the Freedman’s Bank were created by white Northerners who, in some ways, really believed that they could economically help the nation’s almost four million freed African Americans. And so, they conceived of the bank as a vehicle to help them make the really dangerous transition from slavery to freedom, but in terms of their finances and economics.

Ryssdal: The reason this bank failed matters through, not just the history of that period, but up to today, right?

Edwards: It does. There was a financial crash, a financial crisis in the fall of 1873, and African Americans started to withdraw their money en masse. Frederick Douglass comes in, he becomes the bank’s president in March 1874. And he looks at the bank’s finances and realizes that the bank is overleveraged. The finance committee had approved of millions of dollars of bank loans that were not going to be repaid. And interestingly enough, the majority of those loans went to the white partners and businessmen who were affiliated with the bank’s trustees.

Ryssdal: We should point out here that was the Frederick Douglass.

Edwards: Yes. The one and only Frederick Douglass, the most photographed man of the 19th century, was the bank’s last president.

Ryssdal: Okay. Alright. So with all of that, as context, I want to do a little prologue here. Was the supposition by the people who started this bank that Black Americans had not had, not necessarily financial institutions, but financial know-how and financial practices before emancipation?

Edwards: Yes, that’s right. And in many ways, they really didn’t understand the financial knowledge that African Americans were bringing with them into freedom, African Americans who were enslaved were cultivating ideas of how to make and save money in the period of slavery. And so they were bringing with them very concrete ideas about saving and what they wanted to do with their money, which was to buy property and buy land.

Ryssdal: Well, that’s where I wanted to go next. Because, you know, one of the many, many, many tragedies of the Black American economic experience is the inability that Black Americans have had to build generational wealth, and in a way it kind of starts here. You relayed this story, either in an article I read or parts of your other writings, about during the Great Depression, a descendant of one of these people writing to FDR, saying, “It would be really great if I could get my hands on my grandmother’s deposit right now.”

Edwards: Exactly, and so we see that there is kind of a generational memory of the Freedman’s Bank and its failure. And I think in many ways, too, it’s dictated the oftentimes fraught relationship that we’ve seen between the financial services industry and African Americans in the 20th and 21st centuries.

Ryssdal: Well, say more about that, because this was 150-something years ago that this happened, and your theory of the case here is that it affects things today.

Edwards: Yes, I mean, we see, especially in the period after the bank ends, we see African Americans continue not to trust and engage with the financial services industry that becomes so important in building credit to be able to purchase homes to pass down generational wealth. And so, in some ways, it’s not surprising that the wealth gap is as staggering as it is today.

Ryssdal: As you have done the research for your forthcoming book on this subject, the title of which we’ll get to when we say goodbye here, I imagine there were so many instances as you were doing the research, where it was a ‘what if?’ moment. What if things had been different? What if they hadn’t expanded to white bankers? What if the loans had gone to some of the recently enslaved Black Americans? There must have been so many turning points where today it would have been so different.

Edwards: Sure. I mean, I have heard just in my own family the idea of saving money not in banks, but underneath the mattress. In many ways, I think that these kind of memories of the bank, even though we may not have the language to connect it to behaviors today, it’s there, which is why I think that the history of this bank is so important.

#How the Freedman's Bank failure still impacts Black Americans#Freedmens Bank#Freedmen#Black Money#Black Economy#Black Money Matters#Black Banks#Stolen Wealth#Banking by Theft#The Rise and Betrayal of the Freedman’s Bank

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Today, we have Sean McShane, whose cash winnings yesterday total $20,600, Brett Myer, Ellen McRae. The one-game winning streak curse continues as head into today’s game with Sean McShane as the new Jeopardy! Champion. Will it end today? Join me as we enter today’s Jeopardy! highlights to find out! In the Jeopardy! round, Sean had a tormenting lead over Brett. In PLACE“O”, Ellen found the 1st Daily Double, she went “all-in” out of her $1,400 and came up with an incorrect question. There were 6.67% of triple stumpers and 13.33% of rebounds in the round. Going into Double Jeopardy!, Sean had $7,400, Brett had $4,000, and Ellen had $1,400. In Double Jeopardy!, Sean stops Brett from making the game tormenting, but he makes it a runaway. In CHEMISTRY, Sean found the 2nd Daily Double, he bet $3,000 out of his $19,800 and came up with the correct question. In SPANISH ART & ARTISTS, the case of back-to-back Daily Doubles occurred for Sean, he bet $3,000 out of his $22,800 and came up with the correct question. There were 20% of triple stumpers and 3.33% of rebounds in the round. Brett came up with 92.31% of correct questions, Sean came up with 90.32% of correct questions, and Ellen came up with 78.57% of correct questions. Going into Final Jeopardy!, Sean had $28,600, Brett had $11,200, and Ellen had $4,600. The category was, “Demonstrating the dignity & humanity of Black Americans, he sat for 160 known photographs, the most of any American in the 19th century”. Ellen came up with, “Who was Frederick Douglass?”, which is correct and bet $4,000, which took her to $8,600. Brett also came up with what Ellen said and bet $200, which took him to $11,400. Sean also came up with what Brett and Ellen said and bet $4,000, which took him to $32,600. Sean McShane breaks the 1-game winning streak and now has a 2-day total of $53,200. Brett Myer receives $2,000 for 2nd place, and Ellen McRae receives $1,000 for 3rd place. @jeopardy #kenjennings #seanmcshane #brettmyer #ellenmcrae #recap #2022 https://www.instagram.com/p/CmIiAQuuJz9/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes

Link

George Zimmerman admitted at his 2012 bail hearing that he misjudged Trayvon Martin's age when he killed him. “I thought he was a little bit younger than I am,” he said, meaning just under 28. But Trayvon was only 17.

...

People of all races see black children as less innocent, more adultlike and more responsible for their actions than their white peers. In turn, normal childhood behavior, like disobedience, tantrums and back talk, is seen as a criminal threat when black kids do it. Social scientists have found that this misperception causes black children to be ''pushed out, overpoliced and underprotected,'' according to a report by the legal scholar Kimberlé W. Crenshaw.

That's why we must create a future in which children of color are not disproportionately caught up in the criminal justice system, a world in which a black 17-year-old can wear a hoodie without being assumed to be a criminal. Creating that social change, however, has proved difficult. And that's partly because the concept of childhood innocence itself has a deep and disturbing racial history.

By understanding this history, we can learn why anti-racist strategies have hit some surprising limits, and devise tactics to confront or even avoid those roadblocks in the future.

The association between childhood and innocence did not always exist. Before the Enlightenment, children in the West were widely regarded as immodest beings who needed to be taught to restrain themselves. “The devil has been with them already,” the Puritan minister Cotton Mather wrote of babies in 1689. They ‘go astray as soon as they are born.”

In some religious traditions, children, as much as adults, were understood to bear original sin. Benjamin Wadsworth, a powerful Colonial-era minister, described children in 1720 as “sharers in the guilt of Adam” who have a “naturally sinful and guilty state.”

Enlightenment thinkers had different ideas: John Locke suggested that children were blank slates, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau portrayed them as connected to nature. The poet William Wordsworth imagined children as holy innocents who could lead adults to God. Rising forms of Christianity de-emphasized the idea of original sin.

While earlier generations had viewed children as miniature adults, 19th-century sentimentalists increasingly identified innocence as the single most important quality that distinguished children from their elders. By the mid-19th century, the ideas of childhood and innocence had merged. From then on, innocence defined American childhood.

But only white kids were allowed to be innocent. The more that popular writers, playwrights, actors and visual artists created images of innocent white children, the more they depicted children of color, especially black children, as unconstrained imps. Over time, this resulted in them being defined as nonchildren.

“Uncle Tom's Cabin,” one of the most influential books of the 19th century, was pivotal to this process. When Harriet Beecher Stowe published her novel in 1852, she created the angelic white Eva, who contrasted with Topsy, the mischievous black girl.

Stowe carefully showed, however, that Topsy was at heart an innocent child who misbehaved because she had been traumatized, “hardened,” by slavery's violence. Topsy's bad behavior implicated slavery, not her or black children in general.

The novel's success prompted theatrical troupes across the country to adapt “Uncle Tom's Cabin” into what became one of the most popular stage shows of all time. But to attract the biggest audiences, these productions combined Stowe's story with the era's other hugely popular entertainment: minstrelsy.

Topsys onstage, often played by white women in blackface, were adultlike, cartoonish characters who laughed as they were beaten, and who invited audiences to laugh, too. In these shows, Topsy's innocence and vulnerability vanished. The violence that Stowe condemned became a source of delight for white theater audiences.

This minstrel version of Topsy turned into the pickaninny, one of the most damaging racist images ever created. This dehumanized black juvenile character was comically impervious to pain and never needed protection or tenderness.

...

But black activists did not acquiesce to this power play. From the first moments when Topsy devolved into the pickaninny, African-Americans worked to counter the libel that their kids were not vulnerable and not really children. In 1855, Frederick Douglass made exactly this point in “My Bondage and My Freedom” when he asserted, “Slave children are children.”

In the next century, key players in the civil rights movement made childhood innocence central to anti-racist causes. In 1939, the psychologists Kenneth and Mamie Clark introduced the “doll test,” in which black children, when confronted with their own preference for white dolls, burst into tears. The Clarks' findings hit a nerve in part because they used symbols of innocence, dolls and sobbing children, to display the effects of racism. The Supreme Court leaned on these doll tests in its Brown v. Board of Education ruling, which outlawed segregation in public schools in 1954.

The next year, Mamie Till juxtaposed the bloated, pulverized body of her murdered son Emmett with a photograph of him as a smiling schoolboy. The lynchers had defined Emmett as a sexual threat, but his mother made America see him as a kid.

In these cases, black activists captured the political power of childhood innocence, which had previously supported white supremacy, and repurposed it for a civil rights agenda. But there's a catch. As the poet and feminist theorist Audre Lorde wrote: “The master's tools will never dismantle the master's house. They may allow us temporarily to beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change.” This is exactly the case with anti-racist uses of childhood innocence.

The Clarks, Mamie Till and others used childhood innocence to make important political gains, but their use of the “master's tools” ultimately could not erase the racial connotations of childhood innocence itself. And so studies continue to show that black children are seen as less innocent and more adultlike than their white peers.

...

It's time to create language that values justice over innocence. The most important question we can ask about children may not be whether they are inherently innocent. Instead: Are they are hungry? Do they have adequate health care? Are they free from police brutality? Are they threatened by a poisoned and volatile environment? Are they growing up in a securely democratic nation?

All children deserve equal protection under the law not because they're innocent, but because they're people. By understanding children's rights as human rights, we can begin to undermine the political power of childhood innocence, a cultural formation that has proved, over and over, to be one of white supremacy's most potent weapons.

#this title is kind of click-baity it's really not what the article is about at all#racism#white innocence#blm#childhood#sorry this is long but it's all very important#white supremacy#anti black violence

10 notes

·

View notes