#Franco-Flemish

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

youtube

Alexander Agricola (1446-1506) - Belles sur toutes - Tota pulchra es amica mea ·

Frédéric Bétous · Edouard Hazebrouck · Didier Chevalier · La Main Harmonique

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Justice by an Anonymous artist of the Franco/Flemish School, (late 17th century), oil on canvas, 123 x 102 cm, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

#justice#franco flemish school#anonymous#unknown artist#17th century#painting#oil on canvas#ashmolean museum#oxford#allegory#allegorical art#allegorical painting#repost#my upload

23 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Pietro Francavilla (1648-1615)

Apollo Victorious Over Python by Pietro Francavilla (1591)

980 notes

·

View notes

Text

Joaquin Desprez- Du mien amant

youtube

Oh Joaquin Desprez we're really in it now

#music#polyphony#renaissance#josquin desprez#renaissance music#ensemble Clément Janequin#franco-flemish school#flemish polyphony#burgundian school#15th century#16th century#Youtube

0 notes

Text

Jean Baptiste Monnoyer (Franco-Flemish, 1636-1699)

Ein Korb mit Blumen

Oil on canvas

300 notes

·

View notes

Text

Elias and Moses, from a tapestry of the Tranfiguration of Christ, Franco-Flemish, ca. 1460-1470

40 notes

·

View notes

Photo

FRANCO-FLEMISH, CIRCA 1500, POSSIBLY ASSEMBLED FROM ELEMENTS OF THE SAME LARGER TAPESTRY

A MILLE FLEURS TAPESTRY WITH A UNICORN AND A STAG IN A FIELD OF FLOWERS

Information from Christies:

The renowned series of seven “Unicorn Tapestries” in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art at the Cloisters are the most celebrated examples of this subject matter. The scholarship surrounding this series has greatly increased the understanding of both the narrative and the complex symbols represented. The subject of the unicorn fascinated artists in the middle ages. The mystical creature was thought to be invincible, armed with a horn that possessed a therapeutic power. In the series at the Cloisters, the unicorn is depicted in a manner of attitudes, from gentle to ferocious, passive to animalistic. The wild yet noble stag juxtaposed with the majestic and magical unicorn creates a duality of masculinity and femininity, as well as grace and unrest. In other examples of tapestries that depict both a stag and a unicorn, a more outward display of violence is typically illustrated, but the composition of this work can nearly be interpreted as harmonious, two wild creatures acknowledging the grace and power each possess. No blood is shed, and instead they are peacefully at rest, nestled in colorful millefleurs background. The flora and fauna are equally as significant in their symbolism, and play an important role in the interpretation of the tapestries. In the series of Unicorn Tapestries at the Cloisters, over 100 species of plants and herbals are represented. Medieval herbals such as sage and marigolds, along with species like wild orchids and thistles feature prominently. Here, the field of flowers is a reminder that the unicorn was able to withstand the strongest and most deadly poisonous plants by way of his healing horn.

186 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Guildsman Goes Forth to War, World-Building Part II

Historical Departures:

As you might imagine, in a world that's experienced quite a significant change almost a thousand years previously, Europe circa 1500 AD in A Guildsman Goes Forth to War is not the same as the one from our timeline. Names and places are familiar but distinct, and the borders of entire countries have shifted because a battle that went one way in one timeline went the other in this.

For the purposes of this novel, I wish to draw your attention to two more significant historical departures that will be the most central to the main characters and the plot.

The first departure has to do with the outcome of the Franco-Flemish War at the beginning of the 14th century. As in our timeline, the war began as a conflict between Phillip the Fair (although in this world, he was King of Gallia, rather than of France) and the Count of Flanders, and turned into a Flemish revolt against the overlordship of France that enraged and terrified the French chivalry after the Guldensporenslag. Unlike our timeline, however, the Count of Flanders offered marriage of his younger daughter to Rudolf I of the Empire after Phillip blocked his marriage alliance to Edward of Anglia.

While sadly in this timeline the Flemish cause did not ultimately win victory either, the Imperial marriage meant that when French forces pushed the Flemings' backs to the wall at Zierikzee and Mons-en-Pévèle, they were met by an Imperial expeditionary force. Rudolf I was no partisan of the burghers, but neither was he about to have Phillip the Fair as a neighbor. And so instead, the Low Countries became a buffer zone between the Kingdom of Gallia and the Sacrum Imperium.

Major warfare between Gallia and the Empire was avoided. (After all, Phillip had his hands full with Edward and Rudolf desperately needed that bastard Pope to agree to his coronation.) As for the people who had fought so hard for their freedom, the militias were disbanded, the burghers were stripped of much of their former independence, all commoners were forbidden to carry arms, and the local nobility were carefully balanced between Gallician and Imperial lines to keep the peace. Everyone returned to the business of spinning thread into gold. But still the memory of the goedendag lingered...

The second, more recent event is the rise of the Lega di Mille Communi. At the height of the Wars of the Guelphs and Ghibellines, a number of Italian communes hatched a conspiracy "as to dwarf any previous such venture in the history of man." To end the constant fighting and free themselves from the ambitions of Pope and Emperor both, these communes pretended loyalty to both factions, offering loans and fighting men while working within the walls of their own cities to plant spies, provacateurs, and assassins among the leading families of the signorile.

This silent campaign built to its height at the Second Battle of Legnano, where the combined forces of Pope Boniface VIII and his Guelph allies and Emperor Louis IV and his Ghibellines met again at that place honored in song and memory as the place where Barbarossa was humbled. When the battle was fully joined, a pre-arranged signal was given and the condottieri on both sides turned on their own armies, making a daring charge for the command tents of Pope and Emperor alike. In the confusion and chaos, those great and noble persons were taken captive in the name of the newly revealed Lega di Mille Communi.

The shockwave echoed across all Europe. For six months, the greatest secular and religious authorities in Christendom lingered in golden fetters, while Kings and Cardinals from ultramontano threatened foreign intervention. Across northern and central Italy, a civil war raged in the streets and in the fields, but the Guelph and Ghibelline partisans found themselves leaderless and undirected, unwilling to combine with their hated enemies against the professional forces of the well-heeled Lega who toppled government after government from within and without. When the dust had settled, a "Treaty of Perpetual Liberty" was signed by the Empire and the Papal See alike. Under the terms of this pact, the Lega was recognized as independent of both, the sole legitimate sovereign of all territories south of the Alps.

Naturally, this document signed under heavy coercion was immediately repudiated the moment the principals were freed (albeit under heavy bond). Louis IV declared war the moment he set foot on German soil, and Boniface would have done the same in his own territories had he not dropped dead of a rage-induced stroke. For another ten years, the Lega fought to uphold the Treaty, and ultimately narrowly triumphed thanks to a crucial alliance with the Swiss Confederacy that bled the Emperor's legions white as they tried to fight their way south through the Alps, and thanks to a deadlocked Papal conclave (kept that way by heavy bribery and constant espionage) that allowed the Lega to fight on one front at a time.

But in the end, the Lega endured because of the simple principles of its constitution. Under the articles of federation and defensive alliance, each commune was largely free to govern itself within certain boundaries. No separate alliance or agreement with any foreign state was allowed. Limited wars between Communi were allowed after arbitration, but not to the point of outright conquest of one city-state over another. Contracts would be honored across the Lega, and exchange rates between local currencies would be fixed at yearly conferences. Violators would face the combined forces of every other Communi bound together in fraternal oath.

One Pope after the other was crippled with debt until they had to sell the Donation of Pepin city by city and valley by valley, culminating in a truly Croesian subvention from the Lega for the new Prince of the Vatican. The Kingdom of Naples tried again and again to fight its way up the boot, only to find itself mired in costly sieges ahead and suspiciously well-funded peasant rebellions behind, until eventually the House of Anjou declined into civil war. The Lega was not a peaceful country after independence, but the fighting kept their condottieri well-trained and well-paid, and a new cultural ethos emerged among the Communi that they would uphold as jealously as the virginity of their kinswomen: "I against my brother, my brother and I against my cousin, my cousins and I against a foreigner."

And so for the first time since the time of the Divine Julius, one of the major powers of Europe was a Republic(s). A specter had begun to haunt the crowned heads of Christendom...

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ms. 46 (92.MK.92), fol. 1v

Initial Q: Herod Embracing Pilate

from the Bute Psalter created in Paris, France, text and illumination about 1285

By the Bute Master (Franco-Flemish, active about 1260 - 1290), illuminator

Tempera colors, gold, and iron gall ink

Getty Museum

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

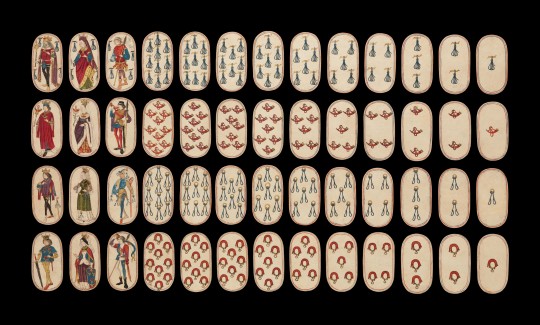

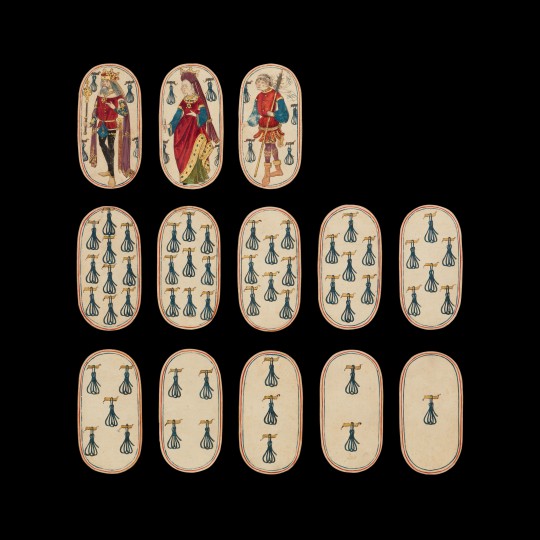

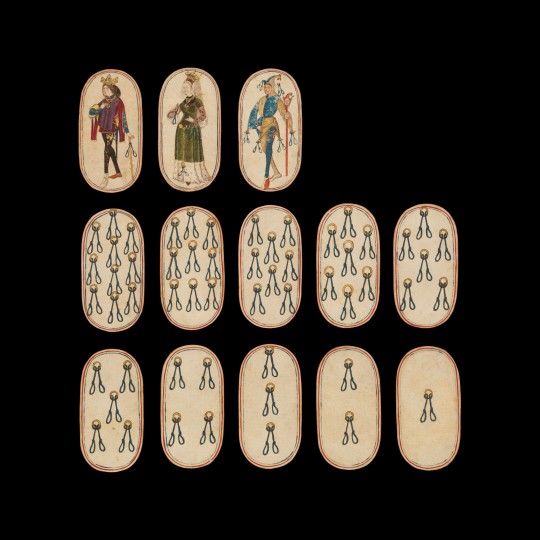

Playing Cards ca. 1475–80

South Netherlandish

The Cloisters set of fifty-two cards constitutes the only known complete deck of illuminated ordinary playing cards (as opposed to tarot cards) from the fifteenth century. There are four suits, each consisting of a king, queen, knave, and ten pip cards. The suit symbols, based on equipment associated with the hunt, are hunting horns, dog collars, hound tethers, and game nooses. The value of the pip cards is indicated by appropriate repetitions of the suit symbol.

The figures, which appear to be based on Franco-Flemish models, were drawn in a bold, free, and engaging, if somewhat unrefined, hand. Their exaggerated and sometimes anachronistic costumes suggest a lampoon of extravagant Burgundian court fashions. Although some period card games are named, it is not known how they were played. Almost all card games did, however, involve some form of gambling. The condition of the set indicates that the cards were hardly used, if at all. It is possible that they were conceived as a collector’s curiosity rather than a deck for play.

Source: The Met Museum

343 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Mabrianus de Orto - Missa ”J’ay pris amours” à 4, Agnus Dei

HUELGAS ENSEMBLE : Cantus: Axelle Bernage, Michaela Riener, Sabine Lutzenberger

Tenor: Achim Schulz, Adriaan De Koster, Timothy Leigh Evans, Tom Phillips, Matthew Vine

Bassus: Tim Scott Whiteley, Guillaume Olry

PAUL VAN NEVEL

0 notes

Text

Tapestry: "Penelope at Her Loom", Fleishman or Franco-Flemish, about 1480-1483

#medieval#penelope#they should put this on display so i specifically can stare at it. tapestry penelope!!!#an ironic medium. isn't it

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

Peonies, Carnations, Poppies and other flowers in a bronze Urn Jean Baptiste Monnoyer (1636-1699, Franco-Flemish)

#dianthus#carnation#painting#still life#flowers#flower vase#peonies#poppies#17th century painting#17th century art#Jean Baptiste Monnoyer

21 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Wenzel Coebergher - Preparations for the martyrdom of St Sebastian - 1599

oil on canvas, height: 288.5 cm (113.5 in); width: 207.5 cm (81.6 in)

Museum of Fine Arts of Nancy, France

Wenceslas Cobergher (1560 – 23 November 1634), sometimes called Wenzel Coebergher, was a Flemish Renaissance architect, engineer, painter, antiquarian, numismatist and economist. Faded somewhat into the background as a painter, he is chiefly remembered today as the man responsible for the draining of the Moëres on the Franco-Belgian border. He is also one of the fathers of the Flemish Baroque style of architecture in the Southern Netherlands.

Born in Antwerp, probably in 1560 (1557, according to one source), he was a natural child of Wenceslas Coeberger and Catharina Raems, which was attested by deed in May 1579. His name is also written as Wenceslaus, Wensel or Wenzel; his surname is sometimes recorded as Coberger, Cobergher, Coebergher, and Koeberger.

Before being known as an engineer, Cobergher began his career as a painter and an architect. In 1573 he started his studies in Antwerp as an apprentice to the painter Marten de Vos. Following the example of his master, Cobergher left for Italy in 1579, trying to fulfil the dream of every artist to study Italian art and culture. On his way there he stayed briefly in Paris, where he learned about his illegitimate birth from seeing the will of his deceased mother. He returned to Antwerp right away to settle some legal matters relating to this discovery. Later in the year, he set forth again to Italy. He settled in Naples in 1580 (as attested by a contract) and remained there till 1597.

In Naples he worked under contract for eight ducats together with the Flemish painter and art dealer Cornelis de Smet. He returned briefly to Antwerp in 1583, buying goods with borrowed money for his second trip to Italy. He is mentioned again in Naples in 1588. In 1591 he allied himself with another compatriot, the painter Jacob Franckaert the Elder (before 1551–1601).

He moved to Rome in 1597 (as attested in a letter to Peter Paul Rubens by Jacques Cools). During that time he had also been preparing a numismatic book in the tradition of Hendrik Goltzius. He must also have built up a reputation as an art connoisseur, since in 1598 he was asked to make an inventory and set a value on the paintings of the deceased cardinal Bonelli.

After the death of his first wife Michaela Cerf on 7 July 1599, he married again, four months later and at the age of forty; his second wife was Suzanna Franckaert, 15-year-old daughter of Jacob Franckaert the Elder, who was also active in Rome. He would have nine children with his second wife, while his first marriage had remained childless.

During his stay in Rome Cobergher became much interested in the study of Roman antiquities, antique architecture and statuary. He was also much interested in the way in which Romans represented their gods in paintings, bronze and marble statues, bas-reliefs and on antique coins. He gathered an important collection of coins and medals from the Roman emperors. These drawings and descriptions were gathered in a set of manuscripts, two of which survive (Brussels, Royal Library of Belgium). He was also preparing an anthology of the Roman Antiquity (according to the French humanist Nicolas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc) that was never published. Sometimes the "Tractatus de pictura antiqua" (published in Mantua, 1591) has been ascribed to Cobergher, but this was based on an erroneous reading of an 18th-century catalogue.

At the same time he was witness to the completion of the dome of St. Peter's Basilica in 1590. The architecture of several Roman churches made also a deep impression on him; among them most influential were the first truly baroque façade of the Church of the Gesù, Santa Maria in Transpontina and Santa Maria in Vallicella. He would use their design in his later constructions.

During his stay in Italy he painted, under the name "maestro Vincenzo", a number of altarpieces and other works for important churches in Naples and Rome. His style is somewhat mixed, incorporating Classical and Mannerist elements. His composition is rational and his rendering of the human anatomy is correct. A few of his altarpieces still survive: a Resurrection (San Domenico Maggiore, Naples), a Crucifixion (Santa Maria di Piedigrotta, Naples), a Birth of Christ (S Sebastiana) and a Holy Spirit (Santa Maria in Vallicella, Rome). One of his best known paintings is the Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian, originally in the Cathedral of Our Lady (Antwerp), but now in the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Nancy. This painting was commissioned by the De Jonge Handboog (archers guild) of Antwerp in 1598, while Cobergher was still in Rome. His Angels Supporting the Dead Lord, originally in the Sint-Antoniuskerk in Antwerp, can now also be found in the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Nancy, while his Ecce Homo is now in the museum of Toulouse.

Cobergher died in Brussels on 23 November 1634, leaving his family in deep financial trouble. His properties in Les Moëres had to be sold, as well as his house in Brussels. Even his extensive art and coin collection was auctioned off for 10,000 guilders.

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anatomical Man from the Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry, by the Limbourg Brothers, Franco-Flemish, ca. 1411-1416

21 notes

·

View notes

Note

Looking at European peasant rebellions, there are some cases of peasants forcing knights and minor nobles to lead them. I don't understand how that could work; whats to stop the so called leader from just running away, or even purposely sending the peasants into a meat grinder?

There's a lot of ways that could happen depending on the circumstances. A lot of these nobles despised the feudal overlords that were above them, particularly for nobles in service to large kings at the fringes of their kingdoms. Peasants might have threatened to not pay or burn their taxes if they didn't rise up in revolt. They could threaten to besiege their keeps (particularly useful if the keep was small or if they had family there) or run them out of town (for hedge knights and other landless warriors). And usually, there were other members of the senior command who knew enough about military strategy that they'd see a bad one - from watch commanders and guards to actual loyalist nobles.

However, usually there was also a system of carrots to supplement the stick. Plenty of these minor nobles would be independent rulers of their new land. As leaders, they'd be entitled to a share of the enemy's war chest. Also, an appeal to community might help smooth things over. Religiously-motivated revolts such as with the Cathars or Lollards had spiritual rewards and a sense of community for supporting their fellow co-religionists, and national/ethnic revolts had similar appeals, such as the Flemish rebelling against France during the Franco-Flemish War.

I could probably be more specific if you had a specific campaign in mind.

Thanks for the question, Alt.

SomethingLikeALawyer, Hand of the King

22 notes

·

View notes