#Frances Villiers

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Photo

Frances Villiers, Countess of Jersey (née Twysden; 25 February 1753 – 23 July 1821) was a British Lady of the Bedchamber, one of the more notorious of the many mistresses of King George IV when he was Prince of Wales, "a scintillating society woman, a heady mix of charm, beauty, and sarcasm".

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

Villiers-Saint-Benoît, Yonne, Bourgogne-Franche-Comté.

#Villiers-Saint-Benoît#Canton of Cœur de Puisaye#Arrondissement of Auxerre#Yonne#Bourgogne-Franche-Comté#France

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mary & George - First Look (2023)

Nicholas Galitzine - Julianne Moore - Tom Victor - Frances Coke - Sean Gilder - Jacob McCarthy - Alice Grant - Niamh Algar

Credit: Sky

Mary & George is inspired by the unbelievable true story of Mary Villiers, who moulded her beautiful and charismatic son, George, to seduce King James VI of Scotland and I of England and become his all-powerful lover. Through outrageous scheming, the pair rose from humble beginnings to become the richest, most titled and influential players the English court had ever seen, and the King’s most trusted advisors. And with England’s place on the world stage under threat from a Spanish invasion and rioters taking to the streets to denounce the King, the stakes could not have been higher.

Prepared to stop at nothing and armed with her ruthless political steel, Mary married her way up the ranks, bribed politicians, colluded with criminals and clawed her way into the heart of the Establishment, making it her own.

Mary & George is a dangerously daring historical psychodrama about an outrageous mother and son who schemed, seduced, and killed to conquer the court of England and the bed of King James.

#Mary & George#Nicholas Galitzine#Julianne Moore#Tom Victor#Frances Coke#Sean Gilder#Jacob McCarthy#Alice Grant#Niamh Algar#George Villiers#Mary Villiers#John Villiers#Amelia Gething#Sir Thomas Compton#Christopher 'Kit' Villiers#Susan Villiers#Sandie#Sky

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

Louis XVIII (1755-1824) by Jean-François-Marie Hüet-Villiers.

#jean francois marie huet villiers#royaume de france#maison de bourbon#louis xviii#roi de france#roi de france et de navarre#vive le roi#louis stanislas xavier#louis de bourbon#comte de provence#comté de provence#kingdom of france#house of bourbon#jean françois marie hüet villiers#art#portrait#king of france

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

View of Villiers-le-Bel, Parisis region of France

French vintage postcard

#postkaart#photo#postcard#French#View#photography#postal#sepia#postkarte#Villiers-le-Bel#briefkaart#vintage#carte postale#ansichtskarte#ephemera#Parisis#historic#region#France#tarjeta

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

"I'm Jean. How was your journey?"

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Désolé pour les fautes.

Macron est un malade mental. Là il est en train de "discuter dissuasion nucléaire avec ses partenaires européens", dont Starmer (GB), Scholz (Allemagne) et Sánchez (Espagne), trois autres cinglés immigrationnistes.

Vitrifier la Russie, puis représailles nucléaires russes s'il reste des moyens et des gens ?

Ce que je ne comprends pas, c'est que ces génocidaires sur leur peuple par la barbarie notamment islamiste massive soient encore en liberté. Vraiment, cela me dépasse totalement, ainsi que le soutien des masses à ces ordures, juste parce qu'on leur a désigné de nouveaux Hitler en "omettant" l'historique des oblasts du sud-est ukrainien. Basile Pesso, Land of Somewhere, 6 mars 2 025 (Fb) Avec citation de Philippe de Villiers et post d'un internaute, ensuite effacés par la source, apparemment eu égard aux fautes

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kit Villiers, Susan Villiers, Sandie the whore, sir Thomas Compton, Francis Bacon, Frances Coke, baby Charles& Edward Coke after George&Kate's wedding

Trnaslation: we want not create embarrassment but the groom likes cock

#mary & george#mary and george#george villiers#katherine villiers#italian meme#i said what i said#baby charles's cameo#bacon is always there#edward coke decide to come tu sopport frances

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

…

#look I know this is a silly hill to die on but as a history nerd I feel I must die on it#George Villiers was not a prince or royalty and barely even nobility#his father died when George was young and they were on the edge of povert but his mum sent him to France to learn to be a courtier#he was also used as a pawn by some court members to oust the kings old favourite that they did not like#so he was essentially sponsored to stay in court and seduce the king#like I said I get it it’s probably not worth my breath#but I think it’s important to know George and his mother worked to pull their family out of obscurity and near poverty#to George receiving dukedom#ANYWAY.#mary & george#nicholas galitzine

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

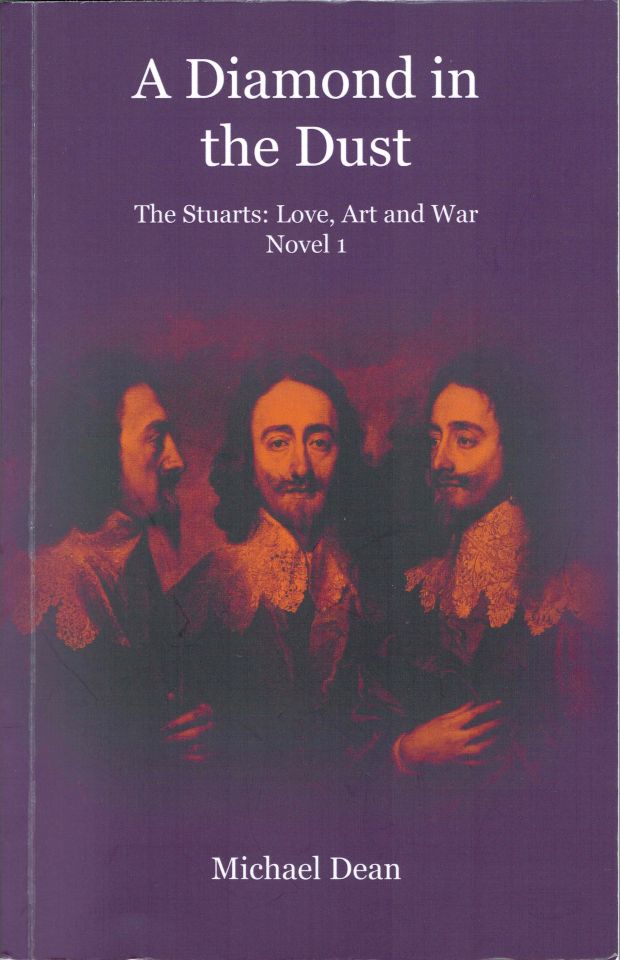

A Diamond In The Dust

["A Diamond in the Dust - The Stuarts: Love, Art, War" by Michael Dean. 24 November 2022. Holland Park Press Ltd. Paperback. 225 pages. ISBN: 9781907320965]

The brutal murder of King Charles I was followed by the establishment of the Commonwealth of England, a brief republic. Reinstatement of the monarchy with his son Charles ll was accompanied by the execution of the judges - the Regicide Judges - who had condemned Charles I to death. Ten of them were hanged, nine of whom were hanged, drawn and quartered. The ringmaster Oliver Cromwell died naturally. His corpse was exhumed, hanged at Tyburn (in London, now Marble Arch), beheaded, and its head mounted above the building where Charles I had been tried.

They knew how to do things in those days.

Michael Dean's A Diamond in the Dust starts and ends with the show trial and execution of Charles I, with a second book - The King's Art - scheduled to take the story forward.

Shortly before his death, Charles I wrote a (very long and frankly dreadful, but yes, execution was going too far) poem titled (with capitals as written) Majesty in Misery, Or an Imploration to the KING OF KINGS. It's not known if God has read it yet, it could take a while. Mercifully Michael Dean only quotes three lines and then solely to explain the title of the book:

With my own Power my Majesty they wound, In the King's name the King himself's uncrown'd, So doth the dust destroy the Diamond.

Watch those capitals Charles. Upper Class OK, Upper Case seldom.

Michael Dean's delightful A Diamond In The Dust is a very exact account of many of the painters artists soldiers and male prostitutes who flourished around the courts of Europe. Charles emerges as worried about what he felt was his mis-shapen body until he finds he is good at something. That something, in what was perhaps his own language was f__king. And to give it context, music, sculpture, f__king, religious wars, wars, f__king, spending money he didn't have, f__king, and when at a loss for something to while away his sybaritic hours, not-surprisingly, more f__king.

This should not suggest that Charles I was promiscuous. On the contrary he and his wife Henrietta Maria seem, after a difficult start (there was a lot of religion, catholic and protestant, involved - all across Europe and all across their lives) to have been not simply in love, but profoundly in love. Charles I does emerge at times as a bit of a pr__k, but, as the English public of the time might well have said, 'at least he's our pr__k).

Art, politics, religion, shipwrecks. Michael Dean knows his controversies and A Diamond In The Dust is crammed to the gunwales with them. George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham is a superbly-drawn (he's real - all the people in the book are, and there are tons of them) character, sexually versatile on both sides, bold, generally courageous, a kind of World-War-II-We'll-Fight-Them-On-The-Beaches lad (he might well have turned up there for a cameo), hated, unfortunately by Queen Henrietta, and in the end murdered. The narrative does slump a bit when he exits, but it's coming to the end (for Charles I) when he leaves the story, and Charles is only going one way.

Michael Dean is expert with history and characters. His novel about the painter Marc Chagall, The White Crucifixion (2018) as well as being a fine novel is a smart piece of work, coming across - like A Diamond in the Dust - with the feel of historical accuracy (only God knows if it's extremely true, but He's tied up with Charles I's Majesty in Misery, possibly for eternity).

A Diamond in the Dust may be one for (1) history experts who long to pick holes in other historians' work while gloating at their superiority; (2) fanatical puritans (OK, Americans), protestants, catholics (it's got lots of all of them, entangled, not always religiously) (3) Republicans (4) Royalists (5) fans of art (yards and yards of art in 225 pages, lots of named works, very detailed biographies of big (and interestingly obscure) artists and patrons. And others who hate being categorised but read The Guardian flagrantly, with a fixed expression of disapproval.

[Image credit: book cover, with thanks to the copyright holders]

John Park

Words Across Time

19 May 2023

wordsacrosstime

#A Diamond In The Dust#Michael Dean#John Park#Words Across Time#wordsacrosstime#May 2023#Holland Park Press#The Stuarts#Bernadette Jansen op de Haar#History#English History#Charles I#Charles II#George Villiers#Duke of Buckingham#Henry Wardlaw#Frances Howard#Queen Henrietta#Anthony van Dyck#Hubert Le Sueur#Oliver Cromwell#Nicholas Lanier#Endymion Porter#Wat Montagu#Abraham van der Doort#Peter Paul Rubens#Jan van Belcamp#Sir John Suckling#Privy Gallery#Henry Frederick

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rouen Cathedral, France (Andrea Villiers)

738 notes

·

View notes

Text

John was ""weak in mind and body" as an historian wrote, he had an unspecifally mentall hillness who made him a problem for himself and for others, especially his wife.

Yes, Frances cheated on him with her ex beau Robert Howard, but she was physically and mentally abused by her husband, and her brothers in law ( George&Kit ) tried everything to ruin her

It's a messy story, really messy and really tragical for booth

trying to find info on george’s two brothers. so far i know one is a cunty lord and other is depressed and. schizophrenic?

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Monceau, Métro Line 2, Paris, France: Monceau is a station on Paris Métro Line 2 near the Parc Monceau on the border of the 8th and 17th arrondissement of Paris. The station is located under the Boulevard de Courcelles at the Place de la République-Dominican, on the edge of the Parc Monceau. Oriented approximately along an east–west axis, it intersects between Courcelles and Villiers stations. Wikipedia

158 notes

·

View notes

Text

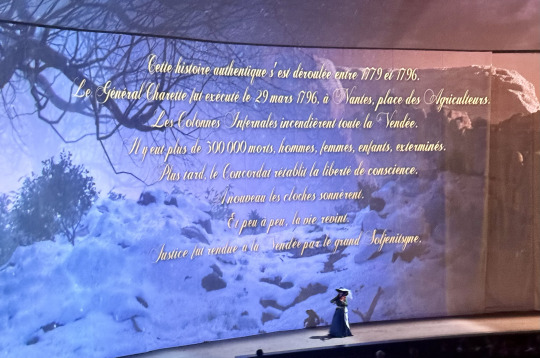

I went to Puy du Fou (1) and watched 'Le Dernier Panache' (2), and needless to say, I've got a few things on my mind. But before I gather my thoughts into something coherent, there’s one pressing issue I need to address: there was NO “extermination” policy in the Vendée.

Is it clear enough for everyone? I sincerely hope so because yesterday, I was among an audience of about 5000 who were shown a scene depicting Robespierre (in yellow), Saint-Just (in turquoise), and Barère (in purple) arguing for the complete destruction of the Vendée… for reasons…

In plain terms, were they advocating for genocide (3) in the Vendée.

This didn’t happen. In 1793, the idea of a distinct Vendéen identity wasn’t a real thing. The Vendéens were not recognized as a specific regional or ethnic group, not by themselves or anyone else.

Do you know what was real? Brigands rebelling against the first French Republic. What were the policies of extermination targeted towards? Those Brigands. What do you call that? Civil War.

On 1st August 1793, Barère delivered an inflamatory speech (4) that many use to argue the Committee of Public Safety's alleged genocidal intent. His words were indeed unhinged, typical of the era’s rhetoric.

Barère did say, "No more Vendée, no more royalty; no more Vendée, no more aristocracy; no more Vendée, and the enemies of the republic have disappeared," but this infamous line follows a crucial preamble: "We will have peace the day the interior is peaceful, that the rebels are subdued, that the brigands are exterminated. (5)" It’s disingenuous to interpret this as a call to wipe out an entire region (6).

Moreover, this speech was followed by the "Décret relatif aux mesures à prendre contre les rebelles de Vendée", which includes an article (the 8th) stating: "Women, children, and the elderly will be taken inland. Provisions will be made for their subsistence and safety, with all the consideration due to humanity" This directive was actually enforced as evidenced by the 20,000 to 40,000 refugees who the government supported in cities like Poitiers, Orléans, and La Rochelle.

The conservative right in France has been peddling this genocide narrative since the mid-1980s, but no amount of dramatic cursive text with melancholic violin strains will convert fiction into fact.

What happened in the Vendée was horrific. Were there war crimes? Numerous. Was the region scarred by the violence? Undoubtedly. Should we acknowledge that? Of course! But pushing a theory that is not true detracts from recognising the violence, learning from it and ensuring it will never happen again.

It also cheapens the heroic acts and sacrifices of those who fought not for the narrow political agendas of the 21st century but for causes they truly believed in. The counter-revolutionaries in the Vendée and throughout France were driven by a deep commitment to protect their communities, faith, and way of life. They were not merely victims of a systematic extermination effort but active participants in a struggle to defend their political and religious beliefs (7). Admittedly, I'm not an expert on Charette, but I suspect he would be disturbed to see his legacy so grossly misrepresented…

Notes

(1) Puy du Fou is a historical theme park in the Vendée known for its elaborate live shows that recreate historical events. It has faced criticism for potentially exploiting history and is managed by the Puy du Fou Foundation, linked to its founder, Philippe de Villiers, a French politician noted for his conservative and nationalist views.

(2) This particular show focuses on François Athanase Charette de La Contrie, a Vendean general.

(3) Genocide is defined by the United Nations in the "Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide", adopted on December 9, 1948, as acts committed with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial, or religious group.

(4) The conflict in the Vendée began in March 1793, prior to Robespierre's association with the Committee of Public Safety. Danton was the one who was instrumental in shaping the initial response to the uprising and was the president of the Convention during Barère’s speech. Weirdly enough, Danton is nowhere on that stage…

(5) The full qoute is "Nous aurons la paix le jour que l'intérieur sera paisible, que les rebelles seront soumis, que les brigands seront exterminés. Les conquêtes et les perfidies des puissances étrangères seront nulles le jour que le département de la Vendée aura perdu son infâme dénomination et sa population parricide et coupable. Plus de Vendée, plus de royauté ; plus de Vendée, plus d'aristocratie ; plus de Vendée, et les ennemis de la république ont disparu. "

(6) This type of rhetoric was not unique to the Vendée but was also directed at other counter-revolutionary hotspots across France like Brittany, Lyon, Marseille, Avignon, etc.

(7) I'm not a particular fan of those beliefs but I can respect the courage to stand up in defence of a lost cause.

#frev#french revolution#robespierre#saint just#bertrand barere#charette#vendée war#vendee#royalist history#puy du fou#distorting history is not ok#even if it makes things more “fun”

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

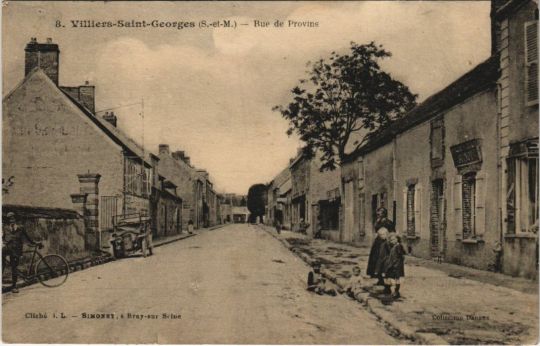

Street scene in Villiers-Saint-Georges, Brie region of France

French vintage postcard

#postkarte#postal#georges#street#saint#ansichtskarte#french#villiers-saint-georges#tarjeta#ephemera#postcard#photography#brie#carte postale#vintage#briefkaart#france#scene#sepia#photo#villiers#postkaart#region#historic

2 notes

·

View notes