#Fort Washita

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Spooktober Haunted Oklahoma: Fort Washita in Durant #hauntedplaces #fortwashita #Durant #oklahoma #durantoklahoma #spooktober #halloween #october

0 notes

Photo

George Armstrong Custer

George Armstrong Custer (l. 1839-1876) was an officer in the US Army, serving in the cavalry from 1861 to 1865 during the American Civil War and the wars against the Plains Indians 1866-1876. Although he became a widely recognized hero during the Civil War, he is best remembered for his death at the Battle of the Little Bighorn.

Custer established a reputation for recklessness, courage, and self-promotion early in the Civil War and, by 1863, after the Battle of Gettysburg, was a national hero. He blocked the retreat of General Robert E. Lee (l. 1807-1870) in April 1865 and was present at Appomattox Court House when Lee surrendered to General Ulysses S. Grant (l. 1822-1885). After the war, he oversaw Reconstruction in Texas before taking command of the newly formed 7th Cavalry in campaigns against the Native Americans of the West.

He led his troops against the Cheyenne people at the Washita Massacre/Battle of the Washita River in November 1868 and, ignoring the terms of the Treaty of Fort Laramie of 1868, marched his troops into the Black Hills in 1874 where he discovered gold. News of this discovery soon brought more settlers and miners into Sioux and Cheyenne territory, igniting the Great Sioux War of 1876-1877. At the Battle of the Little Bighorn (25-26 June 1876) Custer and his men were slaughtered by Arapaho, Cheyenne, and Sioux warriors under chief Sitting Bull (l. c. 1837-1890). Afterwards, thanks in large part to the efforts of his wife, Elizabeth Bacon "Libbie" Custer (l. 1842-1933), George Armstrong Custer came to be regarded as a great American hero.

His legacy and reputation held until shortly before the Second World War (1939-45) when scholars began challenging the traditional narrative. Today, Custer is a controversial figure, often condemned for his brutality and ruthlessness. Although Custer should certainly be held accountable for his actions, it must also be recognized that he was primarily advancing the genocidal policies of his government which saw the American Indian as an obstacle to progress, civilization, and Manifest Destiny.

Early Years & West Point

George Armstrong Custer was born on 5 December 1839 in New Rumley, Ohio, to Emanuel Henry Custer, a blacksmith, and his second wife, Marie Ward Kirkpatrick. He was named after a minister as his mother hoped this would encourage him to follow that path. He had three older half-siblings from his mother's first marriage and four full siblings, including Thomas and Boston, who would also join the military and die with him in battle.

He was sent to live with his older half-sister and her family in Monroe, Michigan, to attend school and met the girl who would one day become his wife, Elizabeth Clift Bacon. After graduating, he moved to Hopedale, Ohio, and enrolled at the Hopedale Normal College, pursuing a teaching degree. He began his teaching career in Cadiz, Ohio, in 1856 and boarded at the home of the Holland family, where he fell in love with the daughter, Mary Jane Holland. He hoped to marry her but found little opportunity for advancement in Ohio, so he decided to change careers and apply to West Point Military Academy. Scholar Nathaniel Philbrick comments:

He'd been a seventeen-year-old schoolteacher back in Ohio when he applied to his local congressman for an appointment to West Point. Since Custer was a Democrat and the congressman was a Republican, his chances seemed slim at best. However, Custer had fallen in love with a local girl, whose father, hoping to get Custer as far away from his daughter as possible, appears to have done everything he could to persuade the congressman to send the schoolteacher with a roving eye to West Point.

(47)

Custer entered West Point in July 1857 and, before the end of his first session, had earned 27 demerits. By graduation, he had been given more demerits than any of the other cadets in his class. After graduation in June 1861, he faced court martial for failing to break up a fight between cadets but was only reprimanded as the American Civil War was already underway. Many of Custer's classmates had left to fight for the Confederacy and the Union forces were in dire need of trained officers. Custer was commissioned a second lieutenant and sent to drill volunteers in Washington, D.C.

Continue reading...

31 notes

·

View notes

Photo

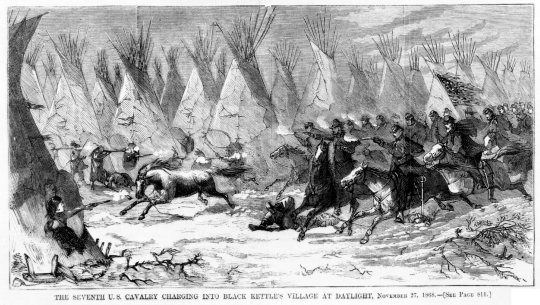

On this day, 27 November 1868, a detachment of US troops under the command of General Custer ignored orders to kill only warriors and massacred 103 sleeping Cheyenne in the so-called "Battle of the Washita". Cheyenne chief Black Kettle had requested permission from US colonial authorities to move his village near to Fort Cobb for protection. The request was refused, but Black Kettle was reassured that if his men stayed in their villages, they would not be attacked. Just before dawn the following morning, while most of the village were asleep, the US Army attacked the village. General Custer had ordered his troops "to destroy their villages and ponies, to kill or hang all warriors, and bring back all women and children." Black Kettle awoke when the attack began and lifted his hand to give a gesture of peace. He and his wife were shot dead, and their bodies ridden over by horses. In just a few minutes, the village was destroyed and hundreds of horses were shot. Rather than separate warriors, the soldiers massacred 103 people, only 11 of whom were warriors, the others being women and children. They also took 53 women and children hostage. Hearing gunfire, a detachment of Arapaho warriors came to the aid of the Cheyenne, as did some Kiowa and Nʉmʉnʉʉ (Comanche). These fighters encountered and wiped out a detachment of 17 US troops. At this point the US army withdrew with its captives. Custer was later killed by Cheyenne, Arapaho and Lakota warriors in the Battle of the Little Bighorn. https://www.facebook.com/workingclasshistory/photos/a.296224173896073/2145997845585354/?type=3

215 notes

·

View notes

Text

Nov 27, 1868, Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer’s 7th U.S. Cavalry attacked Black Kettle’s Southern Cheyenne camp on the Washita River (near present day Cheyenne, OK). These native Americans were not on the warpath, and in fact Black Kettle had just returned from discussions with Colonel William B. Hazen about preserving the peace.

Custer's men attacked the camp at dawn, killing Black Kettle and his wife by shooting them in the back as they fled. Reports indicate that as many women and children were

killed as warriors, and that Custer used fifty-three women and children taken captive at the Washita as human shields during the action.

By early December 1868, the attack had provoked debate and criticism in the press. In the Dec 9 Leavenworth Evening Bulletin, an article noted: "Gen. S. Sandford and Tappan, and Col. Taylor of the Indian Peace Commission, unite in the opinion that the late battle with the Indians was simply an attack upon peaceful bands, which were on the march to their new reservations". The Dec 14 New York Tribune reported, "Col. Wynkoop, agent for the Cheyenne and Arapahos Indians, has published his letter of resignation. He

regards Gen. Custer's late fight as simply a massacre, and says that Black Kettle and his band, friendly Indians, were, when attacked, on their way to their reservation."

The scout James S. Morrison wrote Indian Agent Col. Wynkoop that twice as many women and children as warriors had been killed during the attack. The Fort Cobb Indian trader William Griffenstein told Lt. Col. Custer that the 7th U.S. Cavalry had attacked friendly Indians on the Washita. In response, General Phillip Sheridan ordered Griffenstein out of Indian Territory and threatened to hang him if he returned. The New York Times published a letter describing Custer as taking "sadistic pleasure in slaughtering the Indian ponies

and dogs." It also alluded to his forces' having killed innocent women and children. [O'Blivion]

0 notes

Text

Stone Doorways

The rough stonework of Oklahoma’s frontier-era Fort Washita.

View On WordPress

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

a peek into pioneering jan 2017 fort washita okla

#original photography#photographers on tumblr#sepiatone#minimalism#cabin#window#oklahoma#fort washita

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Fighting Cheyennes :: George Bird Grinnell

The Fighting Cheyennes :: George Bird Grinnell

The Fighting Cheyennes :: George Bird Grinnell soon to be presented for sale on the top-quality BookLovers of Bath web site! North Dighton: JG Press, 1995, Hardback in dust wrapper. Includes: Maps; From the cover: A fighting and fearless people, the Cheyennes were almost constantly at war with neighbouring tribes on the Western plains. Then, between 1856 and 1879, they fought a series of…

View On WordPress

#1-5721-5123-4#adobe walls#battle summit springs#battle washita#battle wolf creek#beecher island#books by george bird grinnell#cheyenne indians wars#comanches#custer battle#david schiffer#first edition books#fort phil kearny#fort robinson#hancock campaign#kiowas indians#lame deer#piatte bridge fight#potawatom#powder river expedition#sand creek#sand creek massacre

0 notes

Text

A Kiowa war chief, Satanta (Set'tainte, White Bear) was probably born circa 1819 on the southern Great Plains. An imposing figure, he was a renowned warrior and member of the Koitsenko soldier society. He emerged as a leader prior to 1850 and signed the Little Arkansas Treaty in 1865. A skilled orator, he rivaled Kicking Bird and Lone Wolf for tribal authority following the death of Dohasan in 1866. Satanta represented the Kiowa at the Medicine Lodge Treaty council in 1867. Despite the acceptance of a reservation in Indian Territory, Kiowa hostilities continued. After the Battle of the Washita in November 1868, Lt. Col. George A. Custer held Satanta captive until the Kiowa had encamped peacefully at Fort Cobb.

In May 1871 Satanta participated in a wagon train attack in Young County, Texas. He, Satank, and Big Tree were arrested after Satanta bragged of the incident to agent Lawrie Tatum at Fort Sill. Ordered to Jacksboro, Texas, to stand trial, Satanta was convicted of murder and sentenced to hang. His sentence was commuted to life imprisonment, and he was transferred to the Texas State Penitentiary at Huntsville. He was eventually returned to Fort Sill, and he remained there until paroled in October 1873. Although Satanta's role during the Red River War is uncertain, his parole stipulated Kiowa nonaggression. Therefore, he was apprehended in the fall of 1874 and returned to Huntsville. There he committed suicide on October 11, 1878. Buried at the prison, Satanta's remains were reinterred at Fort Sill in 1963.

🔥Visit the store to support Native American products

👉 https://www.nativeculturestore.com/stores/bestnative

13 notes

·

View notes

Photo

William Stinson Soule (American, 1836 - 1908). Cheyenne Squaws Captured by General Custer at the Battle of the Washita at Fort Dodge, Kansas, 1867–1874.

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

𝐁𝐚𝐭𝐭𝐥𝐞 𝐨𝐟 𝐋𝐢𝐭𝐭𝐥𝐞 𝐁𝐢𝐠 𝐇𝐨𝐫𝐧, 𝐌𝐞𝐦𝐨𝐢𝐫𝐬 𝐨𝐟 𝐂𝐡𝐢𝐞𝐟 𝐑𝐞𝐝 𝐅𝐨𝐱 (𝟏𝟖𝟕𝟎-𝟏𝟗𝟕𝟔)

"I was six years and fourteen days old at the time of the Custer fight. As it was told to me by my father Chief Black Eagle and my mother White Swan, the sister of Chief Crazy Horse….We left Pine Ridge [Reservation] the eight day of May 1876. Arrived in Montana about June the fifth. My people expected truble they divided up into three different villages. In case of attact they would not be caught in a trap. They knew Custer had left fort Lincolm for the Little Big Horn. Chief Gall and Chief Two-Moons sent word to my uncle Chief Crazy Horse that they were on their way to join him in case of truble with Custer they hatted him for the killing of the fifty three old women men and children and for burning their village several years before [This is a reference to the battle of Washita River, Nov. 27, 1868] and he Raped Black Kettle fourteen year old daughter she gave berth to a boy who is known as Yellow Hawk that they claim is his son from that attact….

On Sunday morning June 25th 1876 Custer…divided his forces into four grupes send Reno to attack my people from the southwest of the Big Horn River. Benteen from the northeast. Godfry and McDugal with the supply train….He told them he would…make the attact at four oclock….About 2 PM…we heard shots fired later we were told that my father and Chief Standing Bear had blocked Captain Benteen from crossing the river. Ghost Dogs, and Crow King had blocked Reno and his men Stinking Bear had Blocked Godfre and McDougal.

About 3 oclock Custer appeared and my uncle Crazy Horse rode out and then retreated like they were afraid. Custer came riding on then. Chief Gall came out to the left side of Custer and Two Moons and his Cheyenns came to the right of Custer. When Custer seen this he started his charge then he dismounted, placed his men on high grounds his horses placed under senteries the Indians made a curcle around him then rode their horses accross the circle kicking up durt [to] stampead his horses. Then the Indians made their attact. Custer bugle sounded for the sentries to bring the horses but they had been killed his bugle sounded for retreat but…most of his men and horses were killed. some said he was the last one to die but that not true. Captain Kegho was the last man to be killed and his horse Comanche was the only horse alive….my people said no one knows who killed [Custer] or when he fell. they say the battle lasted forty minutes….the Indians had better guns than the soldiers good horsemen and knew the country and planed how to fight the battle…''

#question everything#history#ancestors#american bison#native american#indian headdress#indian wars#little big horn#custer's last stand

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Barracks ruins at Fort Washita, Oklahoma by T. Wilson.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Spooktober Oklahoma Treasures: Fort Washita Historic Site in Durant #fortwashita #fortwashitahistoricalsite #fortwashitamuseum #durant #durantoklahoma #oklahoma #haunted #spooktober #halloween #october

#fort washita#fort washita historical site#fort washita museum#durant oklahoma#durant#Oklahoma#haunted#Spooktober#halloween#october

0 notes

Photo

Battle of the Little Bighorn

The Battle of the Little Bighorn (25-26 June 1876) is the most famous engagement of the Great Sioux War (1876-1877). Five divisions of the 7th Cavalry under Lt. Colonel George Armstrong Custer (l. 1839-1876) were wiped out in one day by the combined forces of Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho warriors under the Sioux chief Sitting Bull (l. c. 1837-1890).

Custer located Sitting Bull's camp by the banks of the Little Bighorn River (known to the local Native Americans as the Greasy Grass) in modern-day Montana but had no idea how large it was or how many warriors were present. Having been given a free hand to wage total war against the Plains Indians, Custer divided his command as he had in 1868 at the Washita Massacre. His plan was to attack the camp from opposite sides and close on it in a pincer movement, capturing the women and children as hostages, and forcing whatever warriors had not been killed to surrender. He sent Captain Frederick Benteen (l. 1834-1898) to scout, and Major Marcus Reno (l. 1834-1889) to position himself to strike at the far side.

When Reno launched his attack, however, he was met by a large force of warriors under Sioux war chief Gall (l. c. 1840-1894). Benteen, who had been ordered to bring ammunition to Custer's position, instead tried to support Reno but wound up joining him in retreat. While Gall was driving back Reno and Benteen, Sioux war chief Crazy Horse (l. c. 1840-1877) led a charge against Custer's position.

Custer and all five companies with him were killed in what has come to be known as "Custer's Last Stand." The battle was a decisive Native American victory but could not be capitalized upon because of the public outcry for revenge for the death of Custer, a popular hero of the American Civil War who had also made a name for himself as an Indian Fighter.

After the Battle of the Little Bighorn (also known as the Battle of the Greasy Grass), the Native American leaders went their separate ways to avoid capture and execution. The last major engagements of the Great Sioux War were US victories (or a draw, in the case of the Battle of Wolf Mountain), and, with the Sioux, Cheyenne, Arapaho, and others pushed onto reservations, the Great Plains were open for colonization.

Background

According to the Yanktonai Sioux Chief Lone Dog's Winter Count (a yearly account of events from 1800-1870), "White soldiers made their first appearance in the region" in 1823-1824 (Townsend, 128). The Sioux had little to do with them until 1854 when 2nd Lieutenant John L. Grattan arrived at the camp of Sioux Chief Conquering Bear (l. c. 1800-1854) and demanded the surrender of a man he claimed had stolen a cow from a passing wagon train of Mormons. Conquering Bear refused the demand, Grattan's men opened fire (mortally wounding Conquering Bear), and the Sioux then slaughtered Grattan and the 30 troops under his command in what came to be known as the Grattan Fight or the Grattan Massacre, leading to the First Sioux War of 1854-1856.

Prior to the Grattan Fight, the US government had negotiated land rights and territories with several nations of Plains Indians, including the Sioux and the Cheyenne, through the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851, which stipulated, among other terms, that the United States had no claim on the lands occupied by those nations. Southern Cheyenne Chief Black Kettle (l. c. 1803-1868) was among those who signed the treaty, which was never honored by the United States and was broken in 1858 when gold was discovered in the region, prompting Pike's Peak Gold Rush and an influx of settlers. Further encroachments led to the Colorado War (1864-1865), during which Black Kettle's peaceful village, flying the American flag and the white flag of truce, was attacked in the Sand Creek Massacre of 29 November 1864.

Black Kettle at Sand Creek

Stone Rabbit (CC BY-SA)

As more settlers claimed Native American lands as their own, Oglala Sioux Chief Red Cloud (l. 1822-1909) launched Red Cloud's War (1866-1868) in defense of his people's land and to force the United States to honor its treaty. The war concluded with the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 but, that same year, Black Kettle, his wife, and between 60-150 Cheyenne and Arapaho were slaughtered by troops under Custer's command at the Washita Massacre on 27 November. The treaty of 1868 established the Great Sioux Reservation, but this was broken when, in 1874, Custer discovered gold in the Black Hills, sacred to the Sioux (and other nations) and part of the lands promised them. The Black Hills Gold Rush of 1876 that resulted from Custer's find ignited the Great Sioux War when the US government demanded the Sioux sell the Black Hills and the Sioux refused.

Continue reading...

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Era un giorno di freddo pungente quel 29 novembre del 1864, sul fiume Sand Creek, in Colorado. L’alba sorprese i nativi Cheyenne e Arapaho non solo con la luce nebbiosa del mattino, ma anche con il frastuono di cavalli lanciati al galoppo e urla di soldati in cerca di gloria. Gloria conquistata combattendo contro avversari valorosi, secondo il resoconto dei vincitori, ma che in realtà fu un massacro compiuto su persone inermi:

17 Gennaio 1865 La Vendetta di Mo-Chi

Le donne, i bambini e gli anziani si rifugiarono sotto il simbolo di pace che secondo i trattati avrebbe dovuto proteggerli, la bandiera americana, ma furono uccisi, scalpati e orribilmente mutilati. Il numero dei morti tra i nativi è incerto, compreso tra le 125 e le 175 vittime, mentre perirono 24 soldati dell’esercito statunitense. Alle tre del pomeriggio, tutti gli scampati al massacro si erano nascosti, in attesa del buio.

Incredibilmente, una ragazza di 23 anni chiamata Mo-chi, si alzò incolume dal terreno cosparso di cadaveri. Stordita e tremante, mentre il fumo e la polvere l’avvolgevano, riconobbe i corpi del marito e del padre. Poco prima un soldato le aveva ucciso la madre con un colpo in testa dentro al loro tepee, tentando poi di violentare Mo-chi, che gli aveva sparato col fucile del nonno, uccidendolo. Il dolore assunse la consistenza della rabbia, e dentro di sé, nel suo cuore affranto, giurò vendetta. Prese il fucile e si nascose fino all’arrivo dell’oscurità, quando si incamminò verso nord in cerca di salvezza, mentre il villaggio bruciava e i soldati ridevano e massacravano i sopravvissuti. Insieme ad altri scampati alla carneficina, Mo-chi camminò sulla neve per circa 70 chilometri, prima di raggiungere un campo dei Sioux.

Il massacro del Sand Creek scatenò la rabbia dei nativi delle pianure: molte tribù si unirono per combattere contro i bianchi che non avevano rispettato i trattati di pace, e neppure la bandiera bianca sventolata da una bambina di appena sei anni.

Oltre alla vendetta, gli indiani cercavano anche cibo e coperte, per sopravvivere al lungo inverno. Il 7 gennaio 1865, 1.000 guerrieri (Cheyenne, Sioux e Arapaho) attaccarono Camp Ranking, seguiti da molte donne che governavano i cavalli di scorta. Tra loro c’era anche Mo-chi, che organizzò il carico di tutto ciò che riuscirono a prendere dai magazzini del forte abbandonato dai soldati, attirati fuori da un’avanguardia di guerrieri. Proprio durante quell’incursione, Mo-chi conobbe Medicine Water, l’uomo a cui rimase legata per il resto della vita, uniti dallo stesso spirito di resistenza.

Il 1865 fu un anno difficile per i coloni bianchi: i Cheyenne facevano continue incursioni nei ranch, che spesso venivano bruciati; sempre in quell’anno arrivarono a distruggere i cavi del telegrafo, isolando la città di Denver. Tra loro erano sempre presenti Mo-chi e Medicine Water, che non vollero mai aderire ai nuovi trattati di pace del 1867, combattendo sempre fianco a fianco.

Come in un tragico ripetersi della storia, all’alba di una gelida mattina di novembre del 1868, il giorno 27, il tenente colonnello George A. Custer (proprio quello che poi morì a Little Big Horn nel 1876) attaccò, con 700 uomini del 7° Cavalleria, un accampamento di nativi sul fiume Washita. Il capo del villaggio, Pentola Nera, era sopravvissuto al massacro del Sand Creek, ma questa volta non ce la fece:

Mo-chi rivisse l’incubo del suo villaggio bruciato e disseminato di cadaveri, come nel gelido inverno di quattro anni prima. La donna e il marito, insieme alle figlie, riuscirono a fuggire, aiutati da un altro guerriero, che morì proprio per proteggerli.

Dopo quell’ennesimo massacro, Mo-chi decise di diventare una guerriera, allo stesso modo degli uomini della sua tribù:“Oggi prometto vendetta per l’omicidio della mia famiglia e della mia gente”, disse Mo-chi, secondo la storia orale dei Cheyenne. “Oggi dichiaro guerra a te, uomo bianco. Oggi divento un guerriero, e un guerriero sarò per sempre.”

Negli anni che seguirono, Mo-chi e il marito lottarono contro i cacciatori di bufali, che stavano massacrando senza scopo la principale risorsa dei nativi. L’unica ragione dell’uccisione degli animali era infatti proprio quella di lasciare senza risorse i nativi. E infatti nel 1875 la coppia, insieme ad altri membri della tribù, decise di arrendersi:

Mo-chi, il marito, e altri 30 guerrieri furono condotti in catene, durante un viaggio di sei settimane, fino in Florida, dove furono imprigionati per tre anni, senza aver subito alcun processo. Mo-chi era l’unica donna, e fu l’unica nativa americana a essere considerata una prigioniera di guerra.

Nel 1878 Mo-chi e il marito furono rilasciati, ma il ritorno alla loro terra fu amaro, nella riserva dove ormai il modo di vivere tradizionale dei Cheyenne era solo un ricordo da conservare e raccontare alle nuove generazioni, perché non se ne perdesse anche la memoria. Mo-chi morì nel 1881, a 41 anni, di tubercolosi, mentre il marito visse fino a 90 anni. Nella sua lunga vita, riuscì a trasmettere ai più giovani l’orgoglio di appartenere a una grade nazione, quella dei Cheyenne, sconfitta ma mai domata dall’uomo bianco.

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Washita prisoners at Fort Dodge, 1868. [3525x2325] Check this blog!

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

No More Warmth -

Ruins of a multi-level fireplace at Oklahoma’s Fort Washita.

1 note

·

View note