#For four years it’s the fuck it I’m free era for black folks like me

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

They think he won’t deport them because they aren’t committing crimes. Don’t call us when they do because imma be at home eating popcorn while they do it. my outrage is dead. I’m just laughing at you’re suffering like ha ha

Poor, uneducated whites are about to get fucked around come January 2025. Lmao that complexion isn’t going to save you. Y’all about to literally be in the fucking trenches because of this election, and I honestly can’t wait to see it.

#NOPE!!#I ain’t got 💩for the ones who voted in majority for Trump!#I’m talking about you DACA Latinos#you Muslims#and you Asians.#If your great grandparents#grandparents#or parents#are illegals#you’re all getting deported#under denaturalisation! 🤷🏽♀️#Like welp#You asked for all this#I’m just gonna watch and laugh that’s all#😂😂😂 they going to see aint shit sweet#😂😂😂 and I can’t wait#Happy suffering losers 😂#So many brown people are in for the shock of their lives.#Nah im not gone lie#Trump was exactly what was needed and deserved for this country#cause now im even more staunchly pro Black than before#For four years it’s the fuck it I’m free era for black folks like me#Now I don’t have to carry anyone and I care about everyone in my community#While the hews and those Latino folks who ask for this suffering.#And I don’t have to lift a finger.#2024 presidential election#election 2024#early voting#us election#kamala for president

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Day In LA With Deafheaven // Stereogum

Loud Love : A Day In LA With Deafheaven The California screamers open up about real life, baby ducks, and 'Ordinary Corrupt Human Love'

Full article by Larry Fitzmaurice via Stereogum

Everyone has to grow up eventually — even ducklings. “Look, dude — the baby ducklings!” Deafheaven guitarist Kerry McCoy stops as we’re mid-conversation, pointing out a plump of web-footed friends on a small rolling pitch alongside the walking path of Los Angeles’ Echo Park.

“I know! They’re getting big,” the band’s howling lead singer George Clarke marvels, as the two stop to briefly ponder the not-quite-grown, no-longer-young fowl squatting and waddling on the grass.

“I saw them the other day, too,” says McCoy.

“They were more yellow before,” Clarke explains with a level of attentiveness that would make one think he raised the ducklings himself.

I’m here to observe what Clarke describes to me as “what a normal day for us is like,” as Deafheaven luxuriate in the relative calm before the busyness of touring and promo that will accompany the release of their fourth album, Ordinary Corrupt Human Love (out July 13 via ANTI-). These days, Clarke and McCoy are sticklers for routine — and as they recount their regular goings-on to me, it’s slightly adorable that these longtime friends’ day-to-day approach bears close similarity: wake up around 7 in the morning, hit the gym, run some errands, meet up in the park for a bit, and watch a movie or an episode of Billions before crashing out. Both spend part of their day caring for others: Clarke for his grandfather who currently lives with him, and McCoy for a few persistently hungry cats. “I have to stay out until 6 or 7 PM, otherwise they meow until they get food,” he mock-complains with a grin.

Earlier in the day, Clarke and I hit up the Echo Lake outpost of crunchy Cali natural-food chain Lessen’s, as he dumps a variety of salad-bar ingredients — corn, beets, kale, shredded cabbage and peppers, and a heaping helping of steamed veggies, if you’re looking to take on the Deafheaven Diet — into a container. We walk over to the sprawling Echo Park and Clarke unfurls a sizable blanket, festooned with the album art for the band’s 2013 star-making LP Sunbather, before stripping to a white tank-top and laying out belly-down to nosh while we chat about the latest mixtape from Oakland rapper All Black. McCoy joins us soon after along with former member Stephen Clark, who stoically sips from a bottle of water and sucks down a few cigs while the trio are quite literally sunbathing under the LA rays.

All it takes is one listen to Ordinary Corrupt Human Love to deduct that this period of respite is well-earned. Since their alluring 2011 debut Roads To Judah, the band’s dark-arts alchemy of death metal’s frigid rush, shoegaze’s impressionistic swarm, and the emotional catharsis of post-rock has somehow only grown more epic with every release. That’s even more true with their latest record, which at times recalls Mellon Collie-era Smashing Pumpkins and Sunny Day Real Estate’s Diary in its ultra-bright melodic sweep. There are female vocals present, courtesy of West Coast occult-rocker Chelsea Wolfe — as well as actual singing, as Clarke shows off a deeper vocal register beyond his signature burned-out bark.

The personal boundary-pushing and overall prettiness of Ordinary Corrupt Human Love doesn’t so much suggest a newer, shinier Deafheaven as it does a natural progression (or a full realization, even) of the genre-blending hard rock sound they’ve spent most of the decade refining. As tempting as it might be to refer to the album as Deafheaven’s “mature” turn, there’s still a youthful passion that courses through it like a lit match dropped into dry brush — but that doesn’t mean the quintet haven’t gone through some serious personal changes in the interim between 2015’s New Bermuda and now (which marks, to date, the longest gap between Deafheaven records).

“We were 24 when Sunbather came out,” Clarke reflects while discussing the intense emotions and personal strain the band’s been through since that record’s release. “We were still sleeping on floors when we were home, but the rest of the time we were on tour with idle hands and free cash.” He pauses for a second and chuckles ruefully. “Some people are smart — but we decided not to be.”

Before their current residence in LA (Clarke and McCoy have lived in the city for about four years now) and Deafheaven’s teeth-cutting Bay Area days, the pair spent their adolescence scrapping about in the central California suburbs of Modesto. “It was normal,” McCoy describes their respective upbringings, “but it’s all relative. I’m sure Bill Gates’ kids have seen some shit, too.” But he’s quick to note that the relative mundanity of their upbringing also made for a normalization of the intolerance the young punks experienced growing up, too: “I’d just accepted that the way the world went was seeing a giant truck with a Confederate flag drive by, calling me a fag.” (In the middle of this parkside recollection, Clarke interrupts to point out something decidedly not normal: a shirtless pedestrian sporting a full-chest Monster energy drink tattoo. “Check out how lit this tattoo is,” he giggles, as we briefly debate its authenticity.)

When he was 15, McCoy’s father took him to a protest against the Iraq War, and he wore a white armband to school afterwards, which resulted in him getting “destroyed” by his classmates. “We recently went to the March For Our Lives,” Clarke mentions, “and I think it’s really cool that kids these days — even if they’re not 100% informed on stuff — are really making an effort to be. Comparatively, there was no one [in high school] thinking about anything else other than the direct narrative you were given in this small town.”

Music had been in both of their lives from an early age — McCoy’s father once worked as a music journalist, and some of Clarke’s earliest memories include leafing through CD booklets with his mother — and the outsider feeling both of them shared only further deepened their sonic interests. “When you’re living in the Central Valley and you’re into ‘alternative’ things, it forces you further into the hole you’re digging for yourself,” Clarke explains. “You’re already a loser with acne, and now you’re painting your nails for a Misfits show,” McCoy follows up with a chuckle. His first band was a punky high school outfit called The Confused, which self-distributed a CD called What The Hell that everyone in his social circle thought “sucked.” Clarke’s inaugural musical foray was in a band called Fear And Faith Alike that, in his words, “was very 2002 metalcore.”

CREDIT: Frazer Harrison / Getty Images

Clarke and McCoy first became friends when the latter saw “this fool” (Clarke) sitting outside in the rain during high school, decked out in fishnet arm sleeves, a Slayer T-shirt, and a white backpack covered with pentagrams and band names scrawled in Bic. They stayed close as the former bounced around high schools, returning to Modesto after barely graduating in San Jose; after a few failed attempts at forming post-high school bands, the two formed Deafheaven in 2009 after McCoy joined Clarke to share a $500/month apartment in the Upper Haight area of San Francisco.

Deafheaven began as a pretty much anonymous project, to the point where the pair created a Facebook page for the band that essentially positioned it as a one-man act. “We didn’t tell anyone we grew up with about it,” Clarke explains. “We knew if we told people it was us, everyone would be like ‘Fuck off.'” In 2010, they recorded a demo with Bay Area producer Jack Shirley for the cost of $500, a sum which Clarke and McCoy (who were scrambling to even make monthly rent) struggled to pay back for six months.

“This man’s patience is endless,” Clarke speaks admirably about Shirley, whom McCoy refers to as “the Ian McKaye of the West Coast” and “like a straight-edge Marine”; he’s produced every Deafheaven record since. “They were broke beyond broke,” recalls Shirley, whose work with Deafheaven has led him to record acts like Wolves In The Throne Room and Jeff Rosenstock. “It wasn’t a huge deal, though. I try to be patient in those situations, and I’m glad I didn’t [let money get in the way], because it would’ve severed my ties with a band that I have a great relationship with now.”

After the demo made the rounds online, Deafheaven expanded to a full-band lineup and signed to Converge frontman Jacob Bannon’s Deathwish Inc. label, who released Roads To Judah and Sunbather — the latter of which received a profile-raising critical response that metal and “heavy” music in general typically doesn’t enjoy. “We went from a band that nobody really gave a fuck about, to … not the world’s biggest band, but a thing!” McCoy exclaims. “I had an apartment, I moved to LA, I got a girlfriend — life got kind of big.”

The success Deafheaven enjoyed following Sunbather’s release was, for a band on their level, a bit dizzying. Their fanbase spanned kindred spirits like Mono and Explosions In The Sky to rapper Danny Brown and Third Eye Blind’s Stephan Jenkins. On the other hand, the band found themselves unwittingly receiving the indie-TMZ treatment after a Swedish blogger spotted them hanging out at the VIP area of Gothenburg’s Way Out West festival with a Sub Pop representative (full disclosure: I was also present for said hang), ginning up a post shortly after speculating about the band’s potential next career moves — a surprise to the folks back at Deathwish. “I felt so bad,” Clarke says in a tone of sincerity about the accidental reveal.

CREDIT: Gari Askew II / Stereogum

Combined with the extensive post-Sunbather touring schedule, the increased attention on Deafheaven — as well as the pressures of writing and recording the band’s next album, which they’d committed to within a tight time frame under new label home ANTI- — was starting to take its toll on everyone involved. “All this touring and great stuff was fun and exciting, but it blows up your personality with regards to things you have when you become middle-class,” McCoy states. “And you have habits that blow up with that.”

As work on New Bermuda progressed, the pressure of following up their big breakthrough began to wear on the band — hard. Shirley states that, as a “habitually sober” person, he didn’t witness any dysfunction in the recording studio; but McCoy describes the ways in which Deafheaven’s members dealt with the situation as “unhealthy,” and he and Clarke started to literally lose sleep over the prospect of what would come next. “I’d wake up in the middle of the night thinking that everyone was mad at me because the record sucked,” says McCoy, “and we’d all have to go back to Whole Foods — everyone was laughing at us.”

Various substances were on-hand and frequently present during this time — a product of bad habits never dropped and exacerbated by the party-hardy temporary lifestyle that touring afforded. “You’d be like, ‘Well, I gotta be in the practice space for five hours today — better bring two 40’s,'” Clarke remembers. “When you’re touring for five years, your body degrades,” explains guitarist Shiv Mehra, who joined the band along with drummer Daniel Tracy while Sunbather was being recorded. “Drinking doesn’t help.”

Clarke recalls a show in Sao Paulo on the band’s first South American tour supporting New Bermuda as a colliding point for the band’s substance use and personal strain. “It should’ve been insane,” he recalls with a touch of regret, “But everyone was backstage burnt that the booze wasn’t there yet.”

“We were all just sitting there staring at our phones, waiting for whoever — or whatever — to show up,” McCoy adds. “Our entire world wants to come backstage and be the guy to hang out with you, and they know there’s a certain way to do that.”

“We were all still bothered by each other from touring,” Clark, who possesses a quiet yet thoughtful demeanor, states. “We didn’t have any time off from each other for years.” Following New Bermuda’s tour cycle — a period of time he says “quite literally ruined his life” — he chose to leave the band and was replaced by current bassist Chris Johnson, but still remains close with everyone.

“I didn’t handle having money well,” Clark asserts with straightforward conviction. “It was so easy to party, and I was never much of a partier — so I was all over the world having fun, with no longevity in mind. It all came crashing down.”

“It was a dark and bad experience,” McCoy states plainly on the time period surrounding New Bermuda. By the end of the album cycle, everyone was exhausted, and the mere act of being in the band had turned into drudgery.

“It stopped being fun,” Clarke states on his view towards the band at that point. “It became a chore.”

I ask if there was ever a point during this period of time in which he thought Deafheaven would cease to exist. Later, when I relay his answer to others in the band, they’re quick to note it was an exaggeration, but it’s a rough reply regardless: “I kind of thought someone would die,” says Clarke. We’re not gonna break up because we don’t have anything else, but something drastic or scary happening was within the realm of possibility. If anything would’ve taken us down, it would’ve been … tragic.”

When I press on if there were any specific close calls that took place, the three demur, nervously laugh, and murmur to themselves, “Maybe — not really,” declining to elaborate. “When you’re fuckin’ around, you’re fuckin’ around,” Clarke says with an uneasy chuckle.

Clarke quickly follows up: “When you have a problem, you have a problem.”

Work on Ordinary Corrupt Human Love informally began in late 2016 around a single piano riff McCoy had been toying around with, but much of the album was written and recorded from October of last year until this past February. Deafheaven camped out in a cluster of Oakland homes and, after an informal jam session during the first day of recording, found that the time off did them good.

“We finally dealt with all the stuff that made New Bermuda so dark — and when we did, we realized that all that other stuff was junk,” McCoy passionately describes. “When we all got in a room together, I was like, ‘This was the juice of life right here.'”

“It was like we’d been holding our breath for three years, finally let it out, took another one, and said ‘Everything’s gonna be OK,'” Clarke adds.

In truth, there was still a ways to go. To this day, Deafheaven’s members describe themselves as living “healthier” than before, but McCoy is the only band member who’s completely sober, a decision he made during recording late last year after an extended struggle with drug addiction. It’s a sensitive topic for him to discuss, and the details he’s willing to offer regarding his path to sobriety are scant — but he makes it unmistakably clear that things could not go on the way they were for much longer.

“I’d come to a point where I was done being out there,” he explains, “And I was willing to try anything to get off it.” McCoy reached out to a friend, who helped put him on the path to recovery; he’s been sober since late 2017. “My favorite thing in the world was to play guitar,” he states, “And for a long time, I forgot that. Ever since I made this decision, my life has gotten immeasurably better.”

Casting aside the past was essential for not just McCoy, but the entirety of Deafheaven to move forwards after the fraught period of time they were trying to leave behind. “I don’t think anyone who worked on New Bermuda wanted to make another record that sounded like New Bermuda,” Clarke states, who goes on to describe Ordinary Corrupt Human Love as the sound of “people enjoying what they’re doing.” If the aesthetic of the new album reflects the emotions of the people who recorded it, then the lyrical content zooms in on the world around them — the splendor and sameness of peoples’ everyday lives.

CREDIT: Gari Askew II / Stereogum

The universal, explicitly humanistic focus was developed after Clarke began collaborating with photographer Nick Steinhardt to, in his words, “photograph people in their natural habitat.” “I told him I didn’t want anything extraordinary — just people in their everyday routine, looking at a snapshot of someone in their day and just drinking it in,” he explains. The album’s cover features an anonymous woman in Los Angeles’ Civic Center area, her scarf blowing in front of her face; the inlay art features a child holding out his hand to his mother as he prepares to cross the street.

McCoy describes the album cover as “a potential alternate version” of the iconic album art for Radiohead’s The Bends, and Clarke cites the tinted-hue portraiture of Belle And Sebastian’s visual art as a parallel — both comparisons serving as reminders that, despite their roots in heavy music, their palettes span far beyond what genre purists might come to expect.

youtube

And if Deafheaven’s genre-agnostic approach seemed polarizing around the time of Sunbather, it seems weirdly prescient now. In a way, the 29-year-old McCoy and Clarke are indicative of the landscape-flattening streaming generation, in a good way. Sure, it’s easy to bemoan the age of the algorithm and the fluctuating state of discovery for budding music fans in the digital age. But it’s even easier to forget that discovering “good” music used to possess a distinct social element not far off from joining the football team in high school: Are the indie kids any different than the jocks if they still bristle at people joining their lunch table?

For Deafheaven’s and younger generations, discovering new music is easier than ever, and if you’re willing to turn discovery into creativity as they have been, the possibilities are endless. And anyway, even though Deafheaven’s earlier work was sometimes overshadowed by the band’s perpetual and ineffective battle with the metal scene, the band’s members have since learned to hang with the genre misconceptions. “My girlfriend sent me a screenshot about how ‘Honeycomb’ has a punk section — that’s textbook Oasis!” McCoy says with an easygoing laugh that speaks to a greater truth when it comes to getting older. Sometimes it’s easier to just let old grudges go.

Despite the cloudy forecast, it’s a bit brighter of a day than we’re expecting. With the threat of sunburn fast approaching, we pack up the blanket, take a leisurely walk around the park, and head to the 826 Time Travel Mart. The Mart’s a funky Sunset Blvd. spot funded by the Dave Eggers-founded nonprofit 826, featuring arch, kitschy items ranging from giant dinosaur eggs to a powdered concoction called “robot milk” — but McCoy’s less invested in the temporally-out-of-whack wares on display than he is in the tutoring courses being offered in the next room of the nonprofit-funded space.

An employee explains the programs offered as McCoy listens intently, and when Clarke returns from grabbing a coffee nearby he does similarly. At first blush, the thoughtfulness and social investment that the pair show during my time with them might seem too fitting of a narrative for a band trying to straighten up and fly right — but such character traits often come with growing up, too.

“Nikki Sixx was 27 when shit got really bad and he tried to clean up for the first time,” Clarke points out as our time comes to a close, before McCoy has to go check on the cats and Clarke’s grandfather needs help getting his computer fixed. “We reached that age too. We want to take what we do seriously and have a career — and to eliminate the things that get in the way of that. If you don’t die at 27, you can do a lotof shit.”

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Birth of Def Road

It all started sometime around 1985. As a music journalist and chancer, my brother Johnny rarely paid for anything. I grew accustomed over the years to standing by the entrance while he negotiated free passage into whatever gig we were at.

- ‘I’m on the guest list

- You’re name’s not down

- I rang ahead. I spoke to the manager. I’m doing a write up for Hot Press.

- No one told me’

... and so the drama would unfold, me standing there like a lemon (the +1) thinking ‘can we not just pay the fiver in?’ But inevitably they crumbled and in we went, journalist +1.

The experience would stand him in good stead as he set about liberating the music companies of New York of their choicest cuts. Zip, Buck, Artie and the boys were no match and he returned with a veritable treasure chest of records, none of which he'd paid for. The vast majority belonged to a genre called hip hop, or sometimes rap. Wasn’t that just talking?

By 1985, the Irish Republic had been in existence for nearly 50 years. The Brits, may God’s curses, shit, piss and jizz rain down on them, had long since been kicked out. Ireland was now, finally, in the hands of the Gaels - who immediately palmed it off to the church.

And New York was in my hands. The city, it seemed, consisted mainly of black lads in tracksuits and gold chains. Their ‘music’ involved a DJ stealing the best parts from other people’s records while a rapper bragged in rhyming couplets about, amongst other things, how great he was. The other things could be anything from the size of his cock to how much weed he smoked and on to race, crime, politics, cars, shopping malls, guns, hookers, snot, STDs, cars, watches...the list is long.

Introspective it wasn’t. Feelings and inadequacies rarely entered the lexicon of that first wave of MCs. They spoke with absolute certainty and iron resolve. Self-doubt was an ailment the rapper didn’t appear to suffer from. It was all fierce confusing.

‘No one understands me’, went the lament of angsty teenagers like me. ‘I’m gonna lock myself in my room and listen to The Smiths. Girls are so pretty – if only I could talk to them. Who am I? What’s it all about?’

‘Yo! Everyone look at me, screamed his black NY counterpart. ‘I got the best clothes, I even got jewellery. Girls? Fuck, man. Dime a dozen. Life is so damn straightforward. I’m the coolest, smartest best looking bastard going’.

At first glance, Tramore, Co Waterford seems quite different to the ghettos of New York. People from our neighbouring estates did not spend their time ‘dissing’ each other. Sweetbriar residents did not wish to ‘take out’ motherfuckers from Moon Laun. And gunshots were almost never heard at the Friday night GAA Discos. This could not stand. The ‘boroughs’ of Waterford would have to be re-classified, starting with my hometown.

What is Tramore? Upwardly mobile Gardaí and Secondary School teachers were by now colonizing it's burgeoning estates. A beautiful beach, amusements for the kiddies, pubs, pissed up jackeens in the summer, and now lots and lots of new homes, from where people set off for the bright lights of Waterford City every day if they were fortunate enough to have jobs in 80s Ireland.

We were a bit wussy – just didn’t have that hard edge that came so naturally to people from the barrios of places like Lisduggan and Ballybeg. We weren’t the Bronx. Long Island was seen as being a bit ‘soft and country ’ by New Yorkers. Culchieville, or at least suburban. But it was also where Public Enemy came from, along with De La Soul, EPMD, and Eric B & Rakim to name a handful. They didn't like the name, so they changed it. Long Island became Strong Island.

Tramore, or Tra Mhor as Gaeilge, meaning 'big beach', would now be Strong Beach. Kinda shit, but still better than Tramore. My home address of Cliff Road was renamed Def Road – considerably better. The newly-drawn boroughs of Waterford began to take shape.

It was an era that came to be known as hip hop’s Golden Age. Ireland had once had a golden age of it's own. The Island of Saints and Scholars we had been called, as the Christian Brothers were quick to remind us. Alas that time had long since passed. When darkness prevailed in Medieval Europe, Ireland had been a beacon of light, home to the dopest lyricists and flyest artwork. And as recessionary 80s Ireland trundled on hopelessly, we could at least pat ourselves on the back in the knowledge of our glorious past.

Through the lyrics of the likes of Chuck D and Krs-One I discovered black America was prone to leaning on a similar crutch. The extremist Nation of Islam claimed that the great kingdoms of Africa had thrived when we Europeans, or cave dwellers as they called us, were still running around on all fours. Take that whitey!

Ireland’s time as the foremost creator and preserver of the written word ran from about the sixth to ninth centuries. Missionaries from Christian monastic schools went forth from the motherland into the wild lands of Western Europe; writing, learning and being generally noble as they went. The Roman Empire was falling and the barbarians were ransacking the once civilized and ordered cities of Europe. It was left to a previously unheralded wee island to preserve the written word. Which, miraculously, it did. But no one outside Ireland seemed to care.

It’s a state of affairs that many pan-African movements would empathise with. They often claim history is written by the white man, cynically removing their own people’s contributions from the record books. We break it down a step further. White Anglo-Saxons and Protestants decree what is history – the achievements of the paddy man and the black man just don’t make the cut. And so we glory in our past deeds, with a healthy balance of chips on either shoulder.

The pinnacle of Ireland’s Golden Age would come to be seen as The Book Of Kells, a kind of Three Feet High And Rising of its time. There for all to see in Trinity College - proof of our glorious past. Suck it up, ye bastards!

Hip hop travelled a fair old road to reach its Golden Age, if not quite as far back as the Vikings. But just like the Irish scholars of medieval Ireland, in that second Dark Age of the mid-eighties, hip hop was a beacon of light. As mediocrity thrived all around them, the ghettoes of New York became the ultimate seat of motherfucking learning.

The New York we saw on our 80s TV screens pre-Giuliani and zero tolerance seems barely believable now. Apolcalytic, Mad Max style urban wastelands. Anything went, or so the schoolyards of Tramore CBS would have it. There was never any graffiti on the Tramore-Waterford bus route, aside from the odd ‘Paul is gay’ or ‘Sharon Loves Browner’, but New York?

-‘Sure the whole feckin’ subway is full of it! Can’t even see out de windows. Me uncle works there and he says there do be gay lads stalling the heads off each other on the street. Full of black lads too but they love the Irish so you’re alright there’.

Mental, like. And it was into this environment that one Clive Campbell, soon to be better known as Kool Herc, rocked up on the streets of the Bronx in the early 70s with his quare Jamaican ways.

Quare Jamaican ways that included sound systems – very, very big sound systems – which he used to rock parties all over the neighbourhood. He occasionally employed a rapper, but more importantly began cutting up records. He played the funky, instrumental bit of the tune and then played it again, and again and again if the vibe was right. The break. The two turntables were now an instrument. This was the cue for the b (for break) - boys to do their thing on the dance floor. Or breakdance. The big eejit from the Caribbean had only gone and invented hip hop.

A boyo called Patricius had a gameplan of his own when he rocked up in Ireland with his big Welsh head on him around 432 AD. This was his second trip. First time round he had come as a slave, and spent his days working his hole off high in the mountains, tending sheep and the like. Fuck this for a lark, he thought. And like so many convicts down the years, he turned to God for help.

And he was rewarded with a vision, enabling his escape. Six years swotting up in a French monastery, a brief trip home to check in with the folks, and back to Ireland. ‘ Right. I’m gonna Christianize these chumps’, he vowed to the man above as he returned and set to work.

Patricius was a good egg, albeit one with a bit of ‘previous’. As a former slave, he empathised with their plight, a borderline pinko stance unheard of in those brutal days. The Black Panthers had MLK and Malcolm X, we had Saint Patrick. And he was a hard bastard. Slavery, the monastery and then 30-odd years trundling across the wild lands of Eireann spreading the word. No choirboy either. Some unexplained sin, committed at the age of 15 and later confessed to, racked him with guilt. At least one historian hints at murder. Ireland, denied the ‘civilizing’ influence of the Roman Empire, was no place for the faint-hearted.

The original Paddy may not have driven any snakes out, but if he’d wanted to those slimy fucks wouldn’t have stood a chance. And neither did the pagans. With the bold Patricius at its helm Christianity stomped all over them. Like Ray Houghton a couple of centuries later he had earned his spurs. He was now one of us – an Irishman, and a proud one

Kool Herc was good, but he was no Saint Patrick. He needed help. And two others would rise from the East (Coast) to create a glorious triumvirate. Hip hop now set about crushing the faggoty, silk-shirt and gold-medallioned world of disco.

Afrika Bambaata (or Kevin Donovan as he was then) hadn’t required enslavement to have his eyes opened. He won a motherfucking essay writing contest, motherfucker, first prize being a trip to Africa. Bam’s eyes were opened and he returned with a new vision. No more gang banging – it was peace, love, unity and having fun from here on in.

St. Patrick may have passed on the ‘having fun’ aspect of Bambaata’s message. There was already far too much of that in early 5th century pagan Ireland. But otherwise he surely would have concurred with the mission statement. Patrick had come to enlighten and Christianize, Bam enlighten and Africanize. Peas in a pod. Kind of. Patrick wanted less of that kind of thing, Bambaata probably a bit more. He formed The Universal Zulu Nation, a broad church of hip hop, spirituality and all things Africa.

Joseph Sadler was a wiry little bollocks. Like Herc, he was originally from Jamaica, and was good with his hands. Not only could he spin records, he was a qualified electrician. So it should come as no surprise that it was he who first succeeded in wiring two turntables to a mixer.

-‘Janey Mac’, he said to the waitress at his local cafe , ‘I’ve only gone and opened the door to sampling, changing the face of contemporary popular music, perhaps forever. Not bad for a wiry little bollox from de Bronx, wha’?’

-‘Fuck you on about? she replied.

And he was no mere DJ, either. Herc played his records, Bambaata enlightened, but Grandmaster Flash was a showman. He span the records with his feet, pirouetted, spliced, diced and generally acted like a prize chimp in the DJ’s booth.

- ‘Tell ye what, dat’s savage’, noted Walter ‘the bomb’ MacKenzie to his fellow Bronxian Rashid Washington Jr at one of Flash’s jams.

- ‘Ye not wrong there, so you’re not’, replied his pal. ‘Dem Jamaican lads are at it again. Must be something in the air out there – or maybe the grass, if ye know what I mean. Ay? Ay?

- ‘Ha ha. Ah will ye stop. Tell ye what, though. I predict this will change the face of music as we know it. It won’t be long before it’s threatening the higher echelons of the charts. DJs will now be limited only by their imaginations and the size of their record collections’.

- ‘It will and its bollocks’, replied the less-effusive Washington Jr.

But history shows Mr McKenzie's statement wasn’t a ‘will and its bollocks’ at all. Far from it. Flash, Bam and Herc – the holy trinity, as hip hop lore would have it. The disaffected youth of New York now had a voice, and its name was hip hop.

There would be others. Run DMC duetted with Aerosmith and got heavy rotation on MTV. They even played Live Aid, not that you were likely to see it.

- ‘Run DMC? You fuckin’ kiddin’ me’? We’re trying to raise money for staving Ethiopians. Last thing we need is people ringing in kicking up shit about two black lads in Adidas tops grabbing their balls’. They were the only Live Aid act not shown live on TV, the risk of bollock-grabbing too high.

But it couldn’t stop the juggernaut. And it would culminate in a spotty teenager in the arse end of Ireland being beholden to the sound of black men in sportswear and gold chains rhyming over pre-programmed beats.Watching The Sunday Game one summer’s evening in the late 80s, he realized why.

-Michael, I’ll tell ye now why hurling is the greatest sport in the world. Are ye listening now? I’ve watched some desperate games over the years. Brutal, only brutal. But I’ll tell ye this. No matter how bad it got, there’d always be something. Some lad would crack over a point from 65 metres, or cut one over the bar. Something to have you saying, ‘Holy God, that was savage good.

‘Compare that now to foreign rubbish like soccer. No goals at all in some games. Sure they all have long hair and they wear shinpads. Bunch of Nancy boys. I’ll tell ye know, if I got my hands on....

-‘Thanks Ger/Ogie/Denis/Micheal/Mossie (can't remember who), the point is well made though. Hurling is clearly the world’s greatest game because even the most boring game can be enlivened by a bit of trickery or magic. Ireland and the Irish are great!’

- ‘That’s exactly it Michael’.

This got me thinking. Krs One had a track called ‘Part-time Suckers’. It consisted mainly of a serious of dictionary definitions, intended presumably to illustrate the superiority of his vocabulary over that of his less educated contemporaries. It sounded a bit like the speak-and-spell gizmo that Elliot gave ET to help him phone home. It was pretty shit, in all fairness.

But the last minute or so made it all worthwhile – a DJ workout, scratching the bejaysus out of a line from an old Smokey Robinson song. The half-way line cut over the bar, the point from the impossibly tight angle – the otherwise ‘brutal, only brutal’ track enlivened by a bit of DJ tomfoolery. It all made sense!

Hip hop was the hurling of the ghetto – the black man and the paddy man once more inextricably linked. Def Road would bear witness.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Halloween Gift Guide

♬ Darkness falls across the land ♩ ♪ The midnight hour is close at hand.♫ ♩Creatures crawl in search of blood ♬ To terrorize y’all’s neighborhood ♫ And whosoever shall be found ♬ ♬ With the cash for getting down ♩ ♬Will enjoy our Halloween Gift Guide... ...And stay alive where others died

XENI

Skull Table Runner

A handsome 14x72" graphic banner that can be used for any number of pirate parties, Halloween hoedowns, or other dark festivities.

BUY

MARK

Halloween Cat Favor Boxes

For your favorite trick-or-treaters, fill these 3.25-inch cubes with high-quality confectionery treats.

BUY

ROB

Digital Halloween Decor

At the Boing Boing store, we're proud to offer these spooky holiday decorations. They go in your window, startling passers-by. Now you too can frighten the neighbors without all the legal complications that come from standing there at the window naked in the dark.

BUY

JASON

Super creepy PVC Scooby Doo mask

This creepy Scooby Doo mask is both made of PVC and rather disturbing! Liven up your office party, or even better your spouses.

BUY

DAVID

Bag of 500 Self-Adhesive Googly Eyes

If only you could see what I’ve seen with your googly eyes.

BUY

CORY

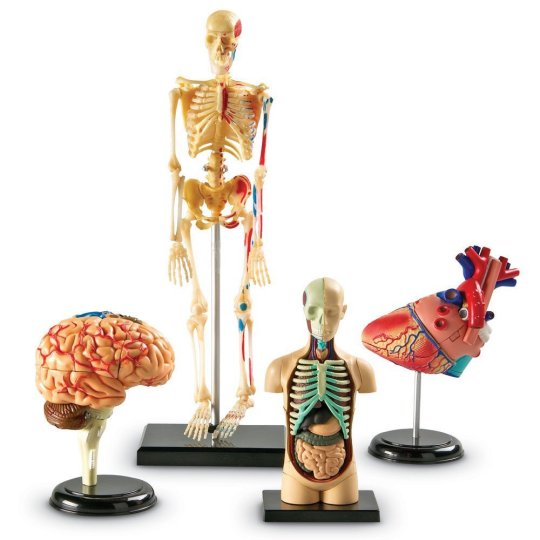

Four anatomical models you assemble from 132 anatomically correct sub-components

The $45.28 Learning Resources Anatomy Models Bundle Set is a well-reviewed set of anatomical models: a 5" heart, a 3.75" brain, a 4.5" body and a 9.2" skeleton, all of which disassemble into anatomically correct sub-components that you assemble into the finished pieces.

BUY

JASON

Five fucking pounds of candy corn

I've heard from some folks they love candy corn when it is stale. They'll be thrilled with this 5lb bag.

BUY

XENI

Dia De Los Muertos Skull Swirlies

This 30-piece Day of the Dead decoration kit includes skulls and swirls in festive foils, and transforms any room or outdoor space within minutes of easy assembly.

BUY

JASON

Twelve cans of Barbisol shaving creme (sewing needle and lighter not included)

This halloween? Relive your youth! Prep a few cans of Barbisol for battle! Wait for those annoying parents who can't pick their kid up from a traffic circle to pass by the bush you've always thought would be a great spot for an ambush, then rain soap upon their parade!

BUY

CORY

Splorch ovipositor

For when you want to role-play stern schwa and sweet, submissive Whitley Streiber; comes in two models but the $120-130 Splorch is the clear winner.

BUY

DAVID

It's the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown (Remastered Deluxe Edition)

More than a half-century since it first aired, Linus is still waiting for the Great Pumpkin to rise "out of his pumpkin patch and flies through the air with his bag of toys for all the children,” Snoopy continues his battle with the Red Baron, and Charlie Brown can’t get a break. A masterpiece of animated television that, like the Peanuts gang, never gets old.

BUY

ROB

Articulating lowpoly skull mask

Wintercroft offers this devilish DIY maskmaking kit (and more like it) for just $6 on Etsy: "Sometimes, we've just got to take life (or death) by the horns and do something a little different. The Horned Skull Mask takes our favourite symbol of warning, mortality, anarchy and independence and ups the ante with a pair of horns and a moving mandible."

BUY

JASON

Lion mane for your cat

This also looks very silly on small dogs.

BUY

XENI

Nightmare-black Nitrile Exam Gloves

Matte black nitrile gloves for cleaning up around the house, or whatever creepy stuff people do with

BUY

DAVID

Be Afraid, Be Very Afraid: The Book of Scary Urban Legends by Jan Harold Brunvand

Brunvand, the iconic professor of urban legends, compiled some of the greatest and grisliest tales of contemporary folklore into one book and wrapped them in compelling context. It’s a wonderfully creepy collection of modern myths, except of course for the story about the teenagers in the parked car who narrowly escaped the hook-armed maniac. That totally happened to my brother’s friend’s cousin and her prom date.

BUY

JASON

Sugar Skull Ducktape

A lovely holiday variant of everyone's favorite fix-all.

BUY

MARK

Vintage Halloween Scene Bobbing Apples Pill Box Pill Case

If you've recently purchased some esoteric research chemicals over the dark web and have been at a loss as to where to store them, this is for you.

BUY

MARK

Spider Web Thigh High Stockings

These unisex stockings can complement any costume, or can be worn on their own for a costume everyone will appreciate.

BUY

DAVID

John Carpenter Anthology: Movie Themes 1974-1998

Carpenter didn’t just direct some of the most iconic scary movies of the latter 20th century, he also scored them. The themes from Halloween, The Fog, The Thing, and They Live make for a fantastically groovy soundtrack for your own horror house. Available on vinyl for those who dare and CD or digital download for those who don’t.

BUY

MARK

Ouija Planchette Lapel Pin

Summon Captain Howdy on-the-go with this cartoon occult ceramic pin.

BUY

ROB

White Walker Halloween costume

Described as a "sexy white walker" Halloween outfit, this also doubles as a terrifyingly realistic costume of Sir Jimmy Savile in his current state of repose. It's $150 and comes in four sizes.

BUY

ROB

Pumpkin Necklace

There's a lot of cheap tatty Halloween jewelry to be found, but ForTheCross's offers year-round quality at a reasonable price. This necklace, for example, comes in under $40.

BUY

CORY

My Favorite Thing is Monsters: a haunting diary of a young girl as a dazzling graphic novel

Emil Ferris's graphic novel debut My Favorite Thing is Monsters may just be the best graphic novel of 2017, and is certainly the best debut I've read in the genre, and it virtually defies summarizing: Karen is a young girl in a rough Chicago neighborhood is obsessed with monsters and synthesia, is outcast among her friends, is queer, is torn apart by the assassination of Martin Luther King, by her mother's terminal illness, by the murder of the upstairs neighbor, a beautiful and broken Holocaust survivor, by her love for her Vietnam-draft-eligible brother and her love of fine art. It's a tribute to -- and critique of -- the classic monster comics and magazines of the era, which Karen is obsessed with, and through whose visual styles her story is told. It's a tribute to fine art and the pieces hanging in the galleries and museums of Chicago where Karen and her mysterious, womanizing, tattooed older brother Deeze brings her. It's a complicated story about friendship among girls, about gender identity and queerness, about family.

BUY

DAVID

Liquid Ass

Invented by a high school prankster with a chemistry set, it’s described as smelling like a fine combination of "butt crack, kind of a sewer smell with a hint of dead animal.” Don’t buy this. But do know that it exists.

BUY

CORY

Animatronic, maniacally giggling spooky eyeball doorbell

When you press the button, the eyelid flips open and a green, glowing, bloodshot eyeball peers around while one of several spooky recordings welcomes your visitors. It is surprisingly well-styled and the audio is surprisingly cool for a seemingly generic crapgadget, and I'm already scheming a teardown after 31st to see if I can program it with my own little recordings.

BUY

XENI

Ancestor Paper Dolls

FROM Tim Holtz, clipped vintage portraits that can be used to make collage greetings or party decorations, or added to a Day of the Dead art-altar.

BUY

MARK

Satan Loves Me T-Shirt

A great way to remember who to thank on the most devilish of holidays.

BUY

XENI

Goth Cotton Swabs

They’re basically really good quality ‘Q-tip’ swabs, with spiral heads, and they’re all black.

BUY

ROB

Skullcap Tee Shirt

Designed by Sarina Frauenfelder, this scary scull is topped out with our classic logo and terrifies your friends with its spooky, staring eyes. $20 shipped.

BUY

CORY

Edgar Allan Poe's "The Raven" - the pop-up book edition

Pelham and Wormell have serious pop-up/illustrated book chops. The seven pop-up effects they've prepared for this edition are extremely beautiful, and lend themselves to being "animated" by the reader -- for example, you can flap the Raven's wings in time with the "Nevermore's"or have Edgar throw wide his chamber's door at the precise moment you say, "here I opened wide the door."Poe's words are hidden on each page, nestled in fold-up/fold-down tabs that you have to open after each reveal, and as I read this to my 9-year-old daughter Poesy (it's not a coincidence that we call her "Poe"for short -- EA Poe is one of her namesakes), the double-reveal of the pop-up (not a dud among them) and the prose made for an extra bit of drama.

BUY

ROB

Bone-shaped battery charger

It's a bit of a reach, but it's the only other thing in our official store that's remotely Halloweeny. (We're all out of 99%-off lifetime subscriptions to Hell, but you can get one of those for free by voting Republican in next year's midterm elections)

https://boingboing.net/2017/10/13/halloween-gift-guide.html

8 notes

·

View notes

Note

MSM is spinning the proposed immigration reform as a reduction of legal immigration from the Obama era but I've been unable to find numbers of whether there was an increase during the Obama administration. Nonetheless, I do think a point based system for entry to allow for more skilled immigrant to come is overall a better move for the US rather than just a simple lottery. Your thoughts?

Before anything else, I want you to see what I saw on NBC News tonight - skip the biased article and just watch the 1 minute clip from NBC News’s August 2nd 6PM broadcast. Note Senator Dick Durbin, D-Illinois, who’s commentary I will transcribe for posterity:

“The biggest flaw in this proposal is the notion that there are long lines of Americans waiting to pick fruit, work in hospitals, and hotels, and restaurants, and meat processing plants; exactly the opposite’s true.”

Let me boil that statement down to its essence: “we need those spics to do the scut-work white people are too good for.” This phrase, “immigrants do jobs Americans won’t do,” is a common utterance on the Left, but it’s still shocking to see a US Senator admit to it in as many words on national TV. I know people who live in rural, poverty-stricken Red America, and you know where they work? They often work in restaurants and meat-packing plants. Not that this asshole would know - to him and Democrats like him, Hispanic immigrants are just cheap labor to maintain the lawns of their expensive homes, to bring them food at restaurant, and to do all the other scut work of society - and cheaply. There aren’t any jobs “Americans won’t do,” if you pay them what it’s worth - ever seen an episode of Dirty Jobs? But that, apparently, would “wreck the economy,” according to reliable RHINO Lindsey Graham, (whom most Republicans would like to see right behind McCain on Musk’s Mars to Stay rocket.) Good thing we’ve got all those Mexicans to do the back-breaking labor on the cheap, eh?

It’s not just Dickface Durbin saying this - ABC News, and New York Times have also published passionate screeds attesting to the necessity of that poor underclass to maintaining our way of life. From the NYT:

Why? Immigrant workers aren’t a “cheap labor” alternative, as so many Americans think. They are the only labor available to do many unskilled jobs, and if they were eliminated, most would not be replaced. Instead, whole sectors of the economy would shrivel, and with them, many other jobs often filled by more skilled Americans.

If the spics don’t pick our cotton for us, who will? Not those fucking Americans!

In 1960, half of all the native-born men in the U.S. labor force were high school dropouts eager to take unskilled outdoor jobs in agriculture and construction. Today, fewer than 10 percent of the native-born men in the work force lack high school diplomas. But the economy still generates plenty of unskilled jobs, and most unskilled immigrants don’t displace American workers. They fill niches — not just farmhand, but also chambermaid, busboy and others — that would otherwise go empty. And they support more skilled, more desirable jobs — foremen, accountants, waiters, chefs and more — at the businesses where they work and others in the surrounding community.

It’s almost like they knew it was a waste of time to finish high school when they could get a job paying good money down at the sawmill - but only if they started their apprenticeship now. But that world’s over and done with - having a high school degree makes you physically incapable of flipping burgers, digging ditches, or picking fruit. True story.

Just raise the wage, you say, and an American would take the job? Not necessarily, and very unlikely if it’s a farm job. Farmers have been trying that — for decades. They raise the wage. They recruit in inner cities. They offer housing and transport and countless other benefits. Still, no one shows — or stays on the job, which is outdoors and grueling and must get done, no matter how hot or cold or otherwise unpleasant the weather.

That’s right - American farmers, already laboring in an industry with narrow profit margins, turned their backs on that vast pool of dirt-cheap, asks-no-questions labor and went to the inner city to hire Americans that’d cost them more money, instead. Nostalgia is powerful, but even if the Red South is as racist as Democrats believe, somehow I doubt lots of American farmers were journeying to the inner city and asking the predominantly black youth there if they were interested in picking cotton on their fucking farms.

And of course, at some point, there are limits to how high a wage a grower or dairy farmer can pay before he is forced out of business by a farmer who produces the same commodity in another country, where the labor actually is cheap.

Which we could handle easily with import/export controls, if not for those fucking free trade proponents - like most Democrats, eh? Of course that doesn’t do you any good when the cheap labor is already in the country and being used by your own domestic competitors.

But worst of all would be the jobs lost for Americans. According to economists, every farm job supports three to four others up and downstream in the local economy: from the people who make and sell fertilizer and farm machinery to those who work in trucking, food processing, grocery stores and restaurants.

A harvest-season fruit picker isn’t a fucking farm job. A farm job is a year-round thing, and there aren’t many of them. I live in rural Michigan, a very agriculture-heavy state, and I have a pony. An actual, living, breathing pony, who eats hay, hay that we purchase from a local farmer. He and his wife run a huge farm and they run it alone, as their sons are too young to do any of the serious work. He does this via automation - the shed under which he stores the hay that we buy also shelters two massive farm tractors, three bale wagons, a combine, and various other attachments and heavy equipment. In our own barn we have a Farmall Cub and a Farmall Super C, two crop-row tractors from yesteryear. They’re about one-quarter the size of those modern New Holland tractors. In fact you can watch the size progression, from the Farmall C to the beefier Farmall H to the imposingly large Farmall M. Tractors increased in size as farms got bigger and more corporatized, and as smaller farmers had to reduce labor and increase automation to stay competitive. For those crops that aren’t harvested en-masse by combines, I’m sure we’ll find some way to pick the fruit. That Farmall Super C in my barn was owned by my great-grandfather - the 3-point implements it used to haul around his farm are still in our possession. My mother picked fruit - for a dime a bushel basket - so she could earn money to buy hay for her own pony. Somehow, they managed. Hell, I managed - I was 12 years old when I was helping my folks put up hay we cut and baled off our own property to help feed our animals.

Arguments so facile that even someone with third-hand knowledge can see through them is one thing, but this is so obvious that the fucking Washington Post, of all places, has a relatively level-headed and informed article covering the matter that perilously resembles actual journalism. It both acknowledges the miserable conditions and low pay of the workers, and dismisses the sweeping claims of absolute economic necessity with actual numbers, provided by subject matter experts.

In absence of established economic necessity, how else are we to interpret statements like Dickface Durbins, but as endorsing class-based systems of oppression? The phrase “jobs Americans won’t do,” the NYT columnist’s equating having a high school diploma with the willingness to do unskilled labor, and Dick Durbin’s own commentary all speak to the same basic hubris: that Americans find these jobs beneath them. I have a 4 year college degree - but I’ve worked manual labor myself, and I never considered burger-flipping to be beneath my dignity. I guess the elite class, the ones that grow up in fabulously wealthy communities and adore their Nature Hikes in the National Parks but let the poor people mow their lawns on a hot day, see things differently. When you combine the Left Wing’s passionate and frequent arguments to the necessity of unskilled, underpaid immigrant labor to supporting our way of life, the inherent elitism that colors their tone and worldview of Americans who “won’t” do these jobs, and above all their unstinting efforts to inhibit the enforcement of immigration law or any initiative to halt illegal immigration, it’s impossible to see their position as anything but encouraging the formation of a permanent underclass of second-class citizens. What happens when those immigrants, or their children, get educated? Get those high school - or even college degrees - that so inhibit their willingness to work menial labor jobs? What happens to our economy then, if we have no cheap, miserably desperate people to exploit for the labor that our economy apparently depends so heavily upon? By their own logic, it would be bad for the country if those poor Hispanics ever worked their way out of the poverty ghetto.

This is the true import of what Dickface Durbin openly stated on national prime-time television. It’s also the strongest argument I can possibly make in favor of Trump’s proposed immigration reform - it is anathema to the class-based exploitation the “progressive left,” self-anointed champions of the poor and down-trodden, argue for so passionately.

9 notes

·

View notes