#Finnish archipelago

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Archipelago - Tuula Lehtinen , 1986.

Finnish, b.1956 -

Colour etching , numbered 25/50, 39.5 x 49.5 cm.

104 notes

·

View notes

Text

also forgot to post these

#visiting real life places like the faroe islands and a lighthouse and the finnish archipelago this summer#gave me a need for a character who lives in a tiny abandoned fishing village in a tiny abandoned church#her name's joseph riskilä aka riski-joe & she has the magical ability to make fire#but she only uses it to light her endless supply of candles#oc#joey#that reminds me that i should see if i have any faroe island photos to post on my main blog....

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Utö (Finland)-Wikipedia

Utö Lighthouse - Wikipedia

#yle.fi#suomi#finland#Baltic sea#Archipelago sea#Pargas#Utö#Alunskär#Outer island#Inhabited island#southernmost year-round inhabited island#European elk#Alces alces#unexpected visitor#swimming#Finnish nature#Nature

1 note

·

View note

Text

a lawyer posted this on linkedin with the caption "In the Finnish archipelago, you can try the same trick with Moomin Characters LTD." 💀😂

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Round One - Set 118

Left: Morning in the Finnish Archipelago, 1887 by Hjalmar Munsterhjelm

Description: painting showing a group of 12 people pull in a large net from their boats, they are close to the shore.

No Propaganda has been submitted.

Morning in the Finnish Archipelago, 1887 by Hjalmar Munsterhjelm. Oil on canvas. The art is 88 × 169,5 cm. The art is at the Finnish National Gallery (link here). The art was photographed by Yehia Eweis.

Right: Fishermen, 1873 by Karl Emanuel Jansson

Description: painting of an old man, a boy and a small dog in a boat, the old man is lifting a net full of fish out of the water.

No Propaganda has been submitted.

Fishermen, 1873 by Karl Emanuel Jansson. Oil on cardbox. The art is 22,5 × 33 cm. The art is at the Finnish National Gallery (link here). The art was photographed by Jukka Romu.

#image description in alt#hjalmar munsterhjelm#karl emanuel jansson#1880s#1870s#19th century#painting#oil painting#polls#round one

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

book review: kirjeitä tove janssonilta [letters from tove] by boel westin & helen svensson (eds.)

Tove Jansson (1914-2001), for the uninitiated was a Finnish painter, author and illustrator, best known as the creator of the Moomins. She had an illustrious 70-year career, publishing her first works at 14 and last at 84.

Kirjeitä Tove Janssonilta (Brev från Tove Jansson in the original Swedish) is a collection of letters written by Tove throughout her life, spanning from the early 1930s all the way to the late 1980s. These letters form a sort of biography, recounting the various stages of Jansson's life, both personal and professional. She writes to her parents, her close friends, her various (male and female) lovers, and her publisher turned friend. She describes her travels, her art and the work of creating it, her love affairs, the Second World War, her summers in the Pellinki archipelago on the Southern coast of Finland, and the growing popularity of the Moomin franchise.

I currently work at the Moomin Museum, and I picked this book up at work to learn more about Jansson's life and to pass the time when it's slow. I read bits and pieces over the course of several months, looking for spots in the dimly-lit museum where there's enough light to read. And I enjoyed it very much, which is why I'm writing a book review for the first time in years.

I already knew the broad strokes of Tove Jansson's life, but the letters, written in her own voice, helped me get to know her as a complex, three-dimensional human being. Some things made me like her less and some things were deeply relatable, but having read the whole thing, I feel I know who Jansson was as a person and not just as a public figure. Her wartime letters were also a great insight into how life went on even as bombs were falling and her brother and boyfriend at the time were at the front.

The most enjoyable part of Tove's letters was not that they were interesting and informative historical documents, but the way she often managed to describe what felt like universally relatable human experiences in such an apt way. Here's a couple memorable exerpts (English translation by me):

"Ja silti – loma on kuin kevät; kaivattu ja ihana, mutta aina liian lyhyt, ilon alla aina niin äärimmäisen melankolinen." [And yet – vacation is like the spring; longed-for and wonderful, but always too short, underneath the joy always so extremely melancholy.]

“Ehkä voisin lähteä Klovharulle yksin kun kaikki on ohi ja kaikki ovat matkustaneet...? Mutten kerro sitä kenellekään, he vain huolestuisivat miten pärjään yksin. Kuka huolestuu siitä miten minä pärjään seurassa!?” [Maybe I could go to Klovharu by myself when everything is over and everyone has travelled...? But I won't tell anyone, they would only worry about how I'll manage by myself. Who will worry about how I'll manage in company!?]

The introduction to each section of letters by the two editors are fairly informative but not that in-depth, so I don't know that I would recommend this book for someone with no prior knowledge of Tove Jansson or her work (for that I suggest Boel Westin's Tove Jansson. Life, Art, Words), but for anyone with a passing knowledge who is looking for a more nuanced understanding of Tove's life and relationships, this collection of letters is a must-read.

Rating: 9/10

12 notes

·

View notes

Note

I would like to know more about the fish in your profile pic. :)

oh!!! of course!!! gladly :) here's a full picture of the little fella:

so this guy's a Perca fluviatilis, or European perch, or just a perch, or in Finnish, ahven!

It's a predatory fish that lives in both fresh and brackish water, so here in Finland, dotted with over 180 000 lakes (albeit most are very small) and surrounded by the brackish waters of the Baltic Sea (or Itämeri in Finnish, which is funny because it means the East Sea even though from Finland said sea is to the west, but it's a direct translation from Swedish, to whom it is in the east lol anyway), it's a very common fish. In fact, it's the most common fish in Finland! There are a lot of little lakes and ponds in which it might be the only fish. It's also the national fish of Finland!

The important characteristics are the red (or really orange usually) fins and tail, the darker stripes, and the spikey dorsal fin, with the little black dot at the end towards the tail. In some of the darkwater lakes they can get almost black, though, so the stripes aren't always visible, but for example in the sea, where the water is clearer, you can see them well.

They can grow pretty big, but are usually 15-30 cm and weigh at most something like 350 grams, though occasionally bigger fish are found. When it comes to people who fish for fun, and not like, with big ships, the perch is the most commonly fished fish in Finland, I think? They can also withstand waters quite a lot acidic than most Finnish fish, which contributes to them living in tiny bog ponds as the only fish in there. Mostly they live in Europe (aside from Spain and Italy) and all the way to the Kolyma River in the Russian far east, but they've been planted in places such as Australia, New Zealand/Aotearoa, South Africa and even China I think? Where they're endangering the native fish species :[ so that's not good

They're pretty curious little fishies! They live in schools of fish during the day and look for food together, but at night they rest on their own at the bottom of the body of water they live in. A few times, when I've gone swimming in a lake with clear water, I've spotted them in the shallow water rather close to people swimming, and when I stayed in place for long enough they came really close a few times! I could've almost touched them, but they're also really fast, so they would've (and probably did) sprint away.

I've caught them a few times, but the ones I've fished have been too small so I've let them go. When my dad's side of the family used to have the cottage in the archipelago my mom has now, my grandparents used to put out the fishing nets (I helped a few times as well!) and then in the morning I'd help take the fishes out of the net, and there'd be perch there pretty often. I've also filleted these fish, and eaten them haha. My favorite is perch covered in flour and fried in butter, served with mashed potato! But most of all I do like just watching them :)

A couple more fun facts! They have a sharp boney spike at the edge of their gill cover, so you have to be careful when you hold them for example taking it off a hook! And the spikes on their back! They're very spiky fish :D

The word for ahven here in Russian is окунь, okun', which according to a version of the etymology, comes from the old word for eye, oko. In Finnish, ahven is pretty close to the reconstructed Proto-Finnic form *ahvën, but we don't know what the etymology for that is! The name for the fish is really similar in most Finnic languages though:

Lastly, the Finnish name for the big island and autonomous region of Åland is Ahvenanmaa, with ahvena being a dialectal form of ahven, and thus the name is like, the land of the perch :) It might come from the fact that in the 1500s, the people from there paid their taxes in perch? The etymology on that one is a little unlcear still! Just a fun little fact. :)

Here's a picture of a little ahven I took in 2018!

I just really like them :) ahven my beloved <3 <3 <3

#thank you for the ask!! :)#if you see a post on tunglr with ahven in it: PLEASE tag me i woudl love to see it

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Please reblog for a bigger sample size!

If you have any fun fact about Åland islands, please tell us and I'll reblog it!

Be respectful in your comments. You can criticize a government without offending its people.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Watched the Käärijä concert stream with this cute Saimaa Ringed Seal squishy.

Norppa the Saimaa Ringed Seal is a platinum silicone squishy from the Finnish adult toy shop 🔞 Kisu and Friends 🔞

(BTW 10% of all Norrpa sales for the calendar year of 2023 will be donated to the Keep the Archipelago Tidy Association.)

#käärijä#indietc#dongblr#warning: do not click on the shop's link if you don't want to see fantasy dildos

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

The little priority signs that let people who live in the Finnish Archipelago or in Hailuoto drive onto the ferry first are funny because they look like some sovereign citizen shit if you don't know what they're about because they don't mention the ferry service at all.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Archipelago View - Vaino Blomstedt , 1910s.

Finnish, 1871 - 1947

Oil on canvas

134 notes

·

View notes

Text

Newspaper Helsingin Sanomat covered a recent survey conducted by the Finnish Red Cross (SPR) in which 82 percent of people in Finland responded that they have either personally experienced or witnessed racism.

Some 83 percent said what they witnessed had not been directed at themselves. In addition, 15 percent of survey respondents said they had witnessed or experienced racism directed at themselves and others.

According to SPR's research, racism was experienced and witnessed most in large cities, where more people with an immigrant background live.

"Witnessing and experiencing racism is also more pronounced among people with a university degree. People over 65 years of age and those living in large areas of eastern and northern Finland are less likely than average to report experiencing or witnessing racism," SPR commented in a press release on the survey results.

However, despite a majority saying they recognised racism, just under half, 45 percent, responded that they had intervened.

On the other hand, 78 percent of respondents under 25 years old said they had intervened.

"It's great that young people and young adults are so vocal about their ability to tackle racism. However, the responsibility should not lie solely with young people. Young people themselves have also expressed the wish that adults should be more active in tackling racism," said Sanna Saarto, SPR's anti-racism action planner, in a press release.

Questions over summer berry crop

Rural-focused newspaper Maaseudun Tulevaisuus carried a warning over this year's berry crop in light of the Finnish Ministry for Foreign Affairs suspending visa applications for berry pickers.

The Ministry announced last week that it would suspend visa applications for wild-berry pickers from Thailand, Cambodia and Myanmar over concerns that the practice leads to exploitation and human trafficking.

Valio, a domestic food producer in Finland, said that if next summer's berry crop is left unpicked in Finnish forests, they may have to resort to importing berries for their products.

"We want to be able to buy responsibly produced domestic forest berries. If we cannot buy domestic wild berries, we may have to buy foreign wild berries," said Kirsti Rautio, Valio's Procurement Director.

However, Rautio said it was too early to assess the impact of the Foreign Ministry's decision on both the availability and prices of domestic wild berries. Valio has not yet made any decisions on berry purchases for next summer's picking season.

While Rautio said there would likely be issues in procuring berries this summer, the responsibility of how they were sourced was also important to the firm.

"We do not tolerate any human rights violations in our supply chain.The main responsibility for monitoring lies with the authorities, and any human rights challenges that arise must be resolved at the Finnish level under the joint leadership of the authorities," Rautio told MT.

Best month for summer holiday?

With winter rearing its head once more, maybe your mind has wandered to summer and are wondering what the best month is to take your holiday. That's what tabloid Ilta-Sanomat asked meteorologist Markus Mäntykannas.

Based on data from 1991 to 2020 showing when it was warmest and sunniest, Mäntykannas said that August might be the best month for heading to the summer cottage.

"Some people may have outdated ideas about when Finland's summers are at their best. August has been a bit of an underrated month for us. I was a bit surprised myself when I looked at the statistics and saw that August is warmer than June in most parts of the country," said Mäntykannas.

Mäntykannas also pointed out that in coastal areas and in the archipelago, temperatures are significantly warmer in August than in June.

"An interesting point in the statistics is that May and June are the months that have warmed the least over the decades. It seems that the late summers have warmed more," said Mäntykannas.

Most people in Finland start their summer holidays at Midsummer at the end of June. Unlike in central and southern Europe, August is not such a popular holiday time in the Nordic countries, partly influenced by school beginning then.

Many businesses and services aimed at holidaymakers also shut down in early August.

The European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) has predicted that this coming summer will be slightly cooler than usual for Finland, while it will be warmer-than-average for southern Europe.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Welcome to Turku

Immerse yourself in a city bursting with rich culture, delectable gastronomy, and thrilling adventures. , a city promising an unforgettable experience to every wanderer who graces its cobblestone streets.

When to Embark on Your Turku Adventure

The best time to experience Turku in all its glory is during the pleasant months of summer (June to August). Revel in festivals, outdoor events, and incredibly long daylight hours.

Getting to Turku

Turku is accessible by both air and rail. Turku Airport caters to domestic and international flights, while a picturesque train ride from Helsinki offers beautiful views of the Finnish countryside.

Where To Stay in Turku

From charming boutique hotels to affordable chain accommodations, Turku houses a plethora of options for every traveler's budget and preference. For a more unique experience, consider one of the city's heart-centered guesthouses.

The Cultural Mosaic of Turku

Begin your cultural journey with a visit to Turku Castle, a 13th-century fortress. Participate in guided tours, admire the stunning architecture, and delve into its rich history. Don't miss the Turku Cathedral, an iconic symbol of the city.

Gastronomy in Turku

The city is a culinary haven, boasting restaurants that highlight authentic Finnish flavors and innovative cuisine. Try the local specialty, Turun Sinappi (Turku mustard), for a distinctive kick to your meal.

Activities and Adventure in Turku

Adventure seekers will relish the myriad of activities from kayaking down the Aura River to spending a day at the popular Moomin World theme park. Explore the vibrant archipelago surrounding Turku by hopping on a ferry or joining a guided boat tour.

Nightlife in Turku

As dusk falls, Turku's nightlife scene comes alive with live music performances, cozy pubs, and trendy clubs that cater to various tastes.

Transportation in Turku

With an efficient public transportation system covering buses and trams, exploring the city is a breeze. Or, rent a bicycle to navigate the bike-friendly streets of Turku at your own pace.

Shopping in Turku

From trendy boutiques to traditional markets, shopping in Turku offers a variety of choices. Visit the city center for a larger shopping experience or stroll the charming streets of the Old Town for unique Finnish designs.

Tips and Money in Turku

- Language: Finnish is the official language, but English is widely spoken. - Currency: Credit cards are accepted, but carry some cash for smaller establishments and markets. - Getting Around: Take advantage of free city maps from the tourist information desk.

Conclusion

Whether you're a history aficionado, a food lover, or an adventure seeker, Turku offers an immersive experience that will leave you wanting to return. So, pack your bags and embark on a journey to the hidden gem of Finland, Turku. Read the full article

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

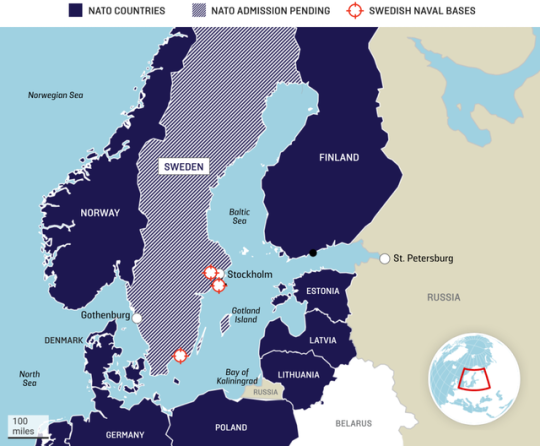

MUSKO NAVAL BASE, Sweden—In a control room carved out of a mountainside near Stockholm, with seats four rows deep, Swedish Navy chief Ewa Skoog Haslum and a close gaggle of her staff look up at a giant monitor to see a troubling scenario unfolding in the Baltic Sea, almost in real time. Their ships are outnumbered. No one, it seems, is coming to help.

This is real life, not a simulation or a war game. It’s October 2023, some 17 months since Sweden launched its bid for NATO membership, and the country is still outside of the alliance. On a filtered maritime traffic map of the region projected above the sailors’ heads, several lonely Swedish and Finnish ships, marked in blue, make their way through the straits, gulfs, and thoroughfares of the eastern arm of the Atlantic Ocean. Without the help of the 31-nation alliance, they are dwarfed by red dots—Russian ships, some military, and others that the Swedes fear might have bad intentions—moving up and down the waterway.

Add Sweden to NATO, and the map changes completely.

“Can we unfilter the picture?” one of Skoog Haslum’s aides asks. Dozens of green ships—NATO vessels—light up the map. The Russian fleet is vastly outnumbered. The tables have turned, Swedish officials said. Taking a shot at one of a handful of Swedish or Finnish ships is one thing. How are the Russians going to take a shot at the Swedish Navy when it has dozens of allied vessels at its back? Defense industry bigwigs, former generals, and think tankers visiting the maritime operations center at Musko Naval Base whisper in hushed awe.

For the better part of 200 years, dating back to the time of Napoleon, Sweden was a neutral country, with its armed forces not venturing beyond its large archipelagoes. Sweden flirted with a defensive nuclear weapons program and mass conscription during the long years of the Cold War but formally stayed neutral.

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 changed all of that. Fearing Russia’s expansionist impulses wouldn’t stop with Ukraine, Sweden, along with Finland, applied for NATO membership in a once-in-a-lifetime political swerve. “There is absolutely a before and after,” Skoog Haslum said last October. “We are more on our toes today.” Now, a step closer to membership in the alliance after Turkey moved to approve Sweden’s bid—but with the Hungarians still holding out—Swedish and NATO officials are hoping that swerve will give the Russians pause before causing problems on their northern border.

The first thing you see when you hit the docks at Berga Naval Base, a short boat ride across the Stockholm Archipelago from the control room at Musko Naval Base, is the 230-foot-long gray camouflage hull of the HSwMS Helsingborg. It doesn’t look like any old U.S. or European ship. The carbon fiber-reinforced frame resembles a pyramid, pointing skyward, to hide from Russian radar.

In a darkened room of computer banks on the ship’s bridge, sailors look at a sea of blue, green, and red ships, too. They are tracking anywhere from 4,000 to 6,000 ship movements in the Baltic Sea every day. On screen, cargo ships such as the Marshal Rokossovsky, the Aleksandr Evlanov, and the Sparta II sail past the Baltic Sea inlets.

If the sailors look nervous, they have a right to be. All of the Nordic countries—including Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden—are heavily dependent on the latter’s western port of Gothenburg for trade. Sweden is especially so: About 30 percent of the country’s foreign trade flows through the port. Shutting down that one port could wreak havoc on the entire region’s economy.

And the screens on the computer banks are constantly changing. Since Russian President Vladimir Putin launched his full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Russian vessels have been moving out and staying away from the Baltic much longer. But the Kremlin is playing a bit of a shell game, Swedish officials said, switching bigger ships for smaller ones. By swapping out destroyers and frigates, which raise alarm bells for NATO countries, for smaller roll-on, roll-off vessels and maintenance ships that aren’t typically used in combat but can still be up-armed with cruise missiles, Russia can keep a foot on this vital chokehold without provoking suspicion.

The Kremlin has also been running tests right in Sweden’s backyard. Russia has begun trials of St. Petersburg-class submarines in the Baltic Sea, conducting live-fire exercises in international waters near Gotland, an island off Sweden’s eastern coast. The Kremlin tries to mask the new submarines by navigating through rivers and internal lakes before unleashing them in exercises that are clearly visible to nearby ships. From a signals intelligence ship parked just outside Kaliningrad’s bay, Sweden has detected Russia test-firing missiles from the submarines.

It all sounds pretty ominous. But the Swedes had to deal with the Russian threat long before the United States even existed. The two sides fought 11 wars, mostly over control of the Baltic Sea, before Stockholm began its two-century drift under neutrality. And with assets such as the Visby-class corvette—a stealthy surface ship armed with torpedoes and anti-ship missiles, named after the main city on Gotland—Sweden wants to be NATO’s eyes and ears in the region.

Sweden can “be a very good NATO member,” Skoog Haslum said, including by providing targeting data for allies in the region.

The country has begun to field Link 22 command-and-control, a secure digital radio system that ties together NATO planes and ships. They are allowed to speak with other nations across those links but on a very low level, such as to point out unidentified or threatening vessels. It’s much easier for Skoog Haslum and her staff to call up Denmark and say hello than it was before the NATO bid, she said.

There’s just one problem: Sweden doesn’t have access to NATO’s encryption. Sweden creates new lines of communication for exercises with NATO countries, but most of those lines go dark once the exercises end. There are no classified communications—yet.

“When we join NATO, that would be on the screen all the time,” said Henrik Rosen, Sweden’s naval attache in Washington. “That is obviously a total game-changer for us.”

In almost every other way, the 31 allies are treating Sweden like one of their own. At NATO’s military headquarters in Mons, Belgium, officials point out that they have already built the flagpole where Sweden’s Nordic cross will eventually fly. At NATO’s official headquarters about an hour’s drive away, just about the only meetings the Swedes can’t get into are with the alliance’s nuclear planning group.

“We act as though they are a member,” a Nordic military official said at the alliance’s Brussels headquarters, where reporters arrived on Jan. 23, the day of Turkey’s parliamentary vote on Sweden’s accession, to discover a flagpole had been built for the Swedes there, too.

Although Turkey has finally, after months of foot-dragging, voted Sweden into the alliance, Hungary has not backed off its objections about Sweden’s NATO membership. Hungary wants Swedish opposition figures that are publicly critical of Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban’s authoritarian leanings to shut up. (Orban came out publicly supporting Sweden’s bid after a call this week with NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg, but Hungary’s top lawmakers still had harsh words for Stockholm.)

But even with the NATO bid still on hold, Sweden appears to be taking a victory lap. In December, Swedish Defense Minister Pal Jonson traveled to the Reagan National Defense Forum in Simi Valley, California—an event full of national security high-rollers—and then on to Washington to sign a defense cooperation agreement with U.S. Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin that gives the U.S. military access to 17 Swedish military bases in the event of a regional war.

Jonson said Sweden’s muscular new foreign policy will push the country past NATO’s agreed-on 2 percent defense spending mark.

“This is the biggest shift in our doctrine for 200 years,” Jonson said in an interview at the Reagan Forum in the rolling southern California hills. “We will continue beyond 2.1 percent [of GDP].”

Where is the money going? Sweden is buying more U.S.-made Patriot air defense systems. It is building a whole new fleet of Gripen fighter jets. It is building new Collins-class submarines and new corvettes. And it is arming its troops with British-made light anti-tank weapons that have torn up Russian tanks in Ukraine as well as fresh armored personnel carriers.

If the name of the game is deterrence in Sweden, then it’s all hands on deck.

“Just being a ship at sea, with maybe a rifle or something, that is not deterrence,” Skoog Haslum said. “Deterrence is to have all assets you can have. The sensors, the weapons systems—that is deterrence.”

Sweden stayed out of both world wars. And after the dust settled in World War II and the Iron Curtain came down, neighbors Norway, Iceland, and Denmark joined NATO. Sweden didn’t.

In secret, though, the Swedes were building up their defenses. During World War II, Sweden built emergency bomb shelters and landing strips as a fallback plan. In 1950, with the United States and the Soviet Union racing to test the first hydrogen bomb, the Swedish government began blasting 1.5 million tons of rock out of a mountainside on the island of Musko, about 25 miles south of Stockholm, to build a top-secret underground naval base.

It took them 19 years. But by the time Musko was completed, Swedish sailors could service submarines and destroyers through a cavernous labyrinth of underground tunnels—and even hunt Soviet submarines. Sweden even briefly pursued nuclear weapons of its own, until officials realized they would cost too much.

After the Cold War, the threat had cooled down enough that Sweden began a widespread process of hollowing out its military, a downturn that lasted nearly 30 years. Sweden gave away most of its 2,000 fighter jets. It shed troops. It got rid of bases.

By 2004, though Swedish troops were in Afghanistan and patrolling the coast of Lebanon, the Riksdag, Sweden’s parliament, was openly stating that the country faced no significant military threats and that it should pare down its defense capabilities to reflect that fact. Defending the homeland wasn’t a mission for the Swedish military anymore.

“The political slogan was, Sweden is best defended in Afghanistan,” said Oscar Jonsson, a defense specialist at the Swedish Defence University. “That was the armed forces we had.”

The only reason that the Swedish government didn’t get rid of Musko was because it would have been too expensive to scrub down the 12 miles of tunnels to make them safe for other uses. So the lights were kept on, but the massive facility was put on a strategic lull, with a skeletal staff. People still worked there 24 hours a day, seven days a week, even when the base was at its least active point, but civilian contractors came in to fill up the vacant shipyards, and tourists were even allowed in.

“It was a little bit of a pity,” Jonsson said. “First of all, you make a secret naval base that can withstand nuclear weapons. Then, at the end of the Cold War, you declassify it. Then, all of a sudden, you realize that it actually needed to be classified again.”

In the Musko mountainside, in a conference room whose wood-paneled walls were made out of the remnants of an old Swedish destroyer, Skoog Haslum and her aides described the bruising effects of the belt tightening on the military. The first thing to go was personnel. The Army downsized from brigades, anywhere from 3,000 to 5,000 troops, to singular battalions, about 1,000 soldiers apiece. Weapons were next. The Navy decommissioned all of its big warships, such as destroyers and frigates, in the 1980s, leaving only smaller ships. The Air Force cut planes. In the mid-2010s, Sweden bottomed out, spending only about 1 percent of its GDP on defense, down from 4 percent in 1963.

But even though Sweden was still neutral, the irritations from Russia had started to pick up. Russian ships were aggressively maneuvering in the Baltic Sea, elbowing Swedish and Finnish ships out of their sea lanes. And Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2014, biting off Crimea and pieces of the Donbas region, made it clear to the Swedes that they could also have a target on their backs.

Sweden’s military budget began to grow in small steps. In 2019, just before the COVID-19 pandemic erupted, the Swedish naval staff returned to Musko. In 2020, the defense budget started to jump, to around $6.25 billion that year, or 1.2 percent of Sweden’s GDP.

Sweden decided to build two new submarines and four new surface ships with surface-to-air missile defenses, which hadn’t been aboard the pyramid-like Visby-class corvettes. Next year’s budget is getting boosted by nearly a third, bringing the overall defense tally to about $11 billion. Sweden is expecting to hit NATO’s 2 percent of GDP defense spending target by the time of the alliance’s Washington summit, which is penciled in for July.

“The rise of the last 10 years of defense spending [has] been very, very steep,” said Rosen, the Swedish naval attache.

Still, Sweden is mostly building more of what it already has. Long-range land attack capability that could challenge Russia is not part of the plan yet.

But Musko is buzzing again. The mess halls are full of Marines with the Swedish Viking emblem pinned to their lapels. The bike racks are full, too, with sailors dropping off their two-wheeled rides—unlocked—after cycling around the miles of tunnels to meetings and maintenance yards.

Sweden’s defense industry is buzzing, too. The onetime carmaker Saab, which uses two of Musko’s drydocks to conduct maintenance on destroyers, has stopped building automobiles and is instead focusing on building Gripen fighter jets and diesel-electric submarines. Volvo builds a line of logistical trucks. Ericsson makes military telephones.

“There is no other country of 10 million that can produce submarines, fighter aircraft, surface combatants, [infantry fighting vehicles], and very advanced artillery systems,” said Jonson, the defense minister.

But unlike next-door neighbor Finland, which can mobilize nearly 300,000 troops from civilian ranks, Sweden faces the problem of getting enough people ready to man those weapons. The nation’s conscription model, which once could mobilize up to half of Sweden’s population, was cut down in the 1990s, tossed altogether in 2010, and has only recently been brought back.

Stockholm is hoping to bring the mobilization number from the current cap of 60,000 to 100,000 conscripts by the end of the decade. Swedish officials are open about the growing pains.

“We are growing, but it’s quite slow,” Skoog Haslum said. “It’s hard to grow, especially when you come from a capacity that is very, very short, actually.”

The boyish-looking sailor had just two words for the group: Strap in.

This reporter soon found out why. Richard Cooke, the young Swedish Marine barking orders, and his driver Emil Munkve, proceeded to send the CB90 fast assault boat we were sitting in screaming through the Musko harbor at almost 50 miles an hour, putting the dozen or so American interlopers straight back in their seats.

Sweden boasts more than 267,000 islands (though, according to the Swedes, an “island” is any piece of land you can stand on with two dry feet).

And fighting here is not like fighting out in the great wide open of the Pacific Ocean. In fact, the U.S. Marines don’t have anything like the CB90. As it drives from Musko to Berga, islands and landforms pop out of the rock. But even in contested waters, the Swedish Marines can go almost anywhere in Stockholm’s island chain, dropping more than a dozen troops ashore at once.

“As long as there aren’t rocks sticking up, we can go right up on the beach,” Munkve said. “We can go as far as the Swedish coast goes.”

Adding that 2,000-mile-long coastline to territory under the alliance’s protection will change NATO. It’s a vast region spanning the Arctic Ocean to the North Sea inlets to the Atlantic, with data cables that undergird much of global communication deep beneath the water’s surface. NATO will get Swedish bases in the north to contend with Russian troops in Murmansk and on the Kola Peninsula.

The Nordic and Baltic countries can’t survive financially without keeping their archipelagoes and the inlets to the Baltic Sea open to maintain commerce through the region. And NATO will get another capable navy that can deal in shallow waters less than 200 feet deep dotted with gulfs, islands, narrow straits, and critical infrastructure.

“In our neck of the woods in the Baltic Sea region, the Western Sea, [and] the Nordic Sea, there’s a lot of infrastructure,” Rosen said. “There’s oil rigs, gas rigs, there’s underwater pipelines, there are underwater cables from communication to power. There are wind parks and windmills out at sea. And there’s a lot of traffic.”

There have been more NATO vessels in the Baltic Sea in the last two years since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. And the Nordic countries have teamed up to follow Russian vessels across the sea with electric optical sensors and an encyclopedic ship base. Starting from Norway’s western coast, the Nordic countries track Russian ships all the way back to St. Petersburg, following them with fixed and mobile sensors, handing off country-by-country as the boats steam through the Baltic.

The Kremlin used to harass U.S. ships in the region. Now the shoe is on the other foot. “[Russia] followed every American vessel that entered the Baltic Sea before,” Skoog Haslum said. “They really followed it. They can’t do that any longer.”

Now, the Kremlin’s game plan is to surround and show presence toward the United Kingdom, the door jam at the western gate of the North Sea. Russia is almost equally as paranoid about keeping trade lanes open through the Baltic and is heavily dependent on getting through it and on to St. Petersburg and Kaliningrad, where the Kremlin has a great deal of its war industry, including shipyards for surface vessels and submarines, which can fire cruise missiles off their backs.

But even though Russia’s Baltic Fleet is largely intact, most of the Kremlin’s troops and ships are tied down by the war in Ukraine.

“Russia has now a long border with NATO … but doesn’t get more forces,” said Dutch Adm. Rob Bauer, the chair of NATO’s Military Committee. “If they want to invest in more forces, it will cost them.”

The Swedes have three watchwords for how they train to fight: Hide inside, run out fast, and hit hard. And they can make it tougher on the Russians by mining the narrow straits before raining missiles on the invaders.

“We use the archipelago. We hide in the archipelago. We fire our long-range weapons from within the archipelago or from the open sea,” one Swedish sailor said. There are still 50,000 mines on the Baltic seabed from World War I and World War II, forcing ships to navigate tight corners laden with explosives.

Sweden’s geography also tightens the squeeze on Russia. Everything in Kaliningrad and St. Petersburg will now be in range of NATO missiles. Gotland gives Sweden and NATO an opportunity to build out a logistical hub or block the Russian navy’s attempts to harass Western shipping lanes. The Bay of Bothnia is a lot closer to Russia’s northern sea bases than NATO’s borders currently sit.

On the flip side, NATO countries will have to defend another big Nordic state that is entirely within striking distance of Russian missiles. And Russia has finally hit Sweden with the avalanche of disinformation and cyberattacks it expected when the country’s NATO bid was announced in May 2022.

But Sweden is not backing down. Though the military shift in the country has been gradual, the political shift has been frenetic.

After two centuries of neutrality, a majority of Swedes only began to favor NATO membership in March 2022, one month after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine began. A month later, that number surged to nearly 60 percent.

In Brussels, NATO allies are ready to welcome them with open arms. But there is still a palpable sense of disbelief at how quickly the tectonic shift has taken place.

“If I told you Finland and Sweden were going to join, you would have thought I was smoking something,” the Nordic military official said. “We are part of a different landscape. Now we have to think completely differently.”

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fortress of Suomenlinna

Today, let's embark on a virtual journey to the enchanting Suomenlinna, a UNESCO World Heritage site nestled in the heart of Finland's capital, Helsinki. Join me as we uncover the rich history, stunning architecture, and captivating landscapes of this historic fortress.

Step back in time as you wander through Suomenlinna's storied past. Originally built in the 18th century, this maritime fortress has stood as a sentinel guarding the waters of the Gulf of Finland. Delve into its fascinating history as a military stronghold, a symbol of Finnish resilience, and a vibrant cultural hub.

Marvel at the architectural wonders that dot the landscape of Suomenlinna. From the imposing walls and sturdy bastions to the charming wooden houses and picturesque courtyards, every corner of the fortress tells a story of centuries past. Let the juxtaposition of man-made structures against the backdrop of the pristine Finnish archipelago mesmerize your senses.

Immerse yourself in Suomenlinna's vibrant cultural scene, where museums and galleries abound. Explore the Suomenlinna Museum to uncover the fortress's secrets, visit the Military Museum for a glimpse into Finland's military history, and discover contemporary art at the various galleries scattered throughout the island.

Indulge in moments of serenity amidst Suomenlinna's natural beauty. Take leisurely strolls along the fortress's cobblestone streets, breathe in the salty sea air as you walk along the rugged coastline, and savor panoramic views of Helsinki's skyline from strategic vantage points. Let the tranquil ambiance of the island soothe your soul.

Treat your taste buds to a culinary adventure in Suomenlinna. From cozy cafes serving freshly baked pastries to waterfront restaurants offering delectable seafood dishes, there's no shortage of gastronomic delights to savor. Don't forget to indulge in traditional Finnish delicacies like creamy salmon soup and hearty Karelian pastries.

Embark on outdoor adventures amidst Suomenlinna's scenic surroundings. Rent a kayak to explore the labyrinthine coastline, find a secluded spot for a picturesque picnic amidst lush greenery, or simply bask in the warmth of the sun as you soak up the island's laid-back vibe.

Can't visit Suomenlinna in person? No problem! Embark on a virtual exploration of the fortress through online tours, interactive exhibits, and immersive experiences. Engage with digital resources that bring Suomenlinna's history and heritage to life, offering a glimpse into Finland's maritime legacy.

In conclusion, Suomenlinna invites you to discover a world of history, culture, and natural beauty within its ancient walls. Whether you're strolling through its cobblestone streets, exploring its museums, or simply soaking in the breathtaking views, Suomenlinna promises an unforgettable experience for all who visit. 🏰🇫🇮

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Husband is preparing for an online bro-down over the movie SISU and I am restraining myself from insisting on the fact that I know what "sisu" means from studying Finnish on Duolingo for a couple of years due to my father's origins in a culturally finnish-swedish archipelago

6 notes

·

View notes