#F sharp lydian

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

been a whole month since i made anything, huh? I've had a lot going on in my life, but I'm slowly working through it all. Here's a little sneak peak at what i'm working on now.

#music#original music#fl studio#my gay music#ambience#forest ambience#F sharp lydian#actually really proud of this one#kinda inspired by lost forest

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

i got your slurp and gulp right here

love has a tension that feels like a maj7#11 chord

#i would but they said my tone was a little sharp#they said to leave but then said i had forgotten my key#and then i was like 'hey wait. didn't you try to sell me fet earlier? what's up with that'#and he was like 'oh no i got out of that business. just too many accidents with f'#if we take the lydian scale of c which has an f sharp

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Today's study is an exploration of the Ionian Mode, which I find I used to overlook as being "just the same as the major scale". While they are indeed the same notes, I have found that a distinction does exist in how they are used.

One of my goals stepping into today's piece was to write something that only uses seven diatonic notes. My usual harmonic style is always shifting around different diatonic and non-diatonic spaces, so today I wanted to challenge myself by strictly using just seven notes. My solution was to write a modal piece.

I chose Ionian because I don't find many people writing for it. I get the sense that composers (myself included)choose not to since they believe it would sound too similar to major-key tonal music, and thus it would not sound very modal. However, after some experimentation, I find that to not be the case. In this study, I kept the harmony mostly static, as to avoid any chord progressions that would make the piece seem to have functional, tonal harmony.

Instead, I aimed to create harmonic interest by using the characteristic notes of the Ionian Mode. The perfect 4th (to distinguish it from Lydian) and major 7th (to distinguish it from Mixolydian). Adding the perfect fourth to a major triad can be a dangerous endevour, as it clashes with the major third, but with careful voicing (i.e., spreading these notes to a major seventh, and never a minor ninth) it becomes a colouristic effect rather than a dissonance. I was also careful in which instruments use these tones, often placing the 3rd in a softer timbre than the 4th as to lighten the dissonance.

The result has the piece in an unusual state, skirting the line between Gb Ionian and Cb Lydian. The abundance of Gbadd4 harmonies can be understood as a suspended Cb chord, but there's just enough emphasis on Gb in the bass to keep Cb from sounding like the root.

In writing this, I have finally come to understand why Ionian wasn't one of the original church modes; the fourth is just so unstable over the root, constantly trying to be the root instead (resulting in the Lydian Mode). The perfect fourth is inherently designed around functional, tonal music, specifically its pull down to the major third as part of dominant function. When that functionality is gone, this note is simply hard to use, being simply more dissonant overall than the Lydian Mode's #4.

As for why I wrote this in G flat, the voicings at the start actually come from a shape I found on guitar (technically baritone ukelele, same DGBE strings) where I could use the open B string for the add4 part of a major chord, resulting in F#add4. I rewrote it in Gb for this study, simply because it looks cleaner, especially for the transposing instruments, since they add sharps to their keys.

As always, these pieces are welcome for anyone and everyone to play! All I ask is that you share it with me, because I'd love to hear it done by live players!

#composer#composition#sheet music#classical music#alternative classical music#flute#oboe#clarinet#horn#french horn#bassoon#wind quintet#woodwind quintet#flute music#oboe music#clarinet music#horn music#french horn music#bassoon music#woodwind#woodwinds#woodwind music#harmony#music theory#woodwind quintet music#wind quintet music#music#21st century music#Youtube

0 notes

Text

Essential Music Theory for Guitarists: Understanding Scales, Modes, and Keys

As a guitarist, having a solid foundation in music theory is key to unlocking your full potential and expanding your creativity on the instrument. Understanding scales, modes, and keys lays the groundwork for improvisation, composition, and overall musical comprehension. In this blog, we will delve into the essential concepts of music theory that every guitarist should know, equipping you with the knowledge to navigate scales, modes, and keys with confidence.

The Basics: Notes and the Chromatic Scale: To understand scales and modes, it's important to start with the basic building blocks of music: notes. The chromatic scale consists of all 12 notes in Western music, moving sequentially from one note to the next, including sharps (#) and flats (b).

Scales: Major and Minor: Scales are fundamental to music theory and provide the foundation for melodies and harmonies. Focus on two essential scales:

a. Major Scale: The major scale is the most common scale in Western music. It follows a specific pattern of whole steps (W) and half steps (H) and serves as the basis for constructing chords and melodies. b. Minor Scale: The minor scale has a different pattern of whole steps and half steps, creating a distinct mood compared to the major scale. Understanding minor scales adds depth and variety to your playing.

Scale Modes: Modes are different variations of a scale that start and end on different notes, altering the tonal center and overall sound. Familiarize yourself with the following modes derived from the major scale:

a. Ionian Mode (Major Scale): The Ionian mode is the standard major scale and serves as the starting point for understanding other modes. b. Dorian Mode: The Dorian mode has a minor tonality but with a raised sixth degree, lending it a unique sound. c. Phrygian Mode: The Phrygian mode features a minor tonality with a lowered second degree, creating an exotic and mysterious feel. d. Lydian Mode: The Lydian mode has a major tonality with a raised fourth degree, resulting in a bright and uplifting sound. e. Mixolydian Mode: The Mixolydian mode has a major tonality with a lowered seventh degree, producing a bluesy and soulful vibe. f. Aeolian Mode (Natural Minor Scale): The Aeolian mode is the relative minor scale of the major scale and is commonly used in rock, blues, and jazz music. g. Locrian Mode: The Locrian mode has a diminished tonality with both a lowered second and fifth degree, creating a tense and unstable quality.

Keys and Key Signatures: Keys provide a framework for understanding music and help determine the tonal center and chords used in a piece. Key signatures indicate the sharps or flats present in a specific key. Key concepts include:

a. Major and Minor Keys: Each major and minor scale corresponds to a specific key, such as the key of C major or the key of A minor. b. Key Signatures: Key signatures consist of sharps or flats placed at the beginning of a musical staff, indicating the key of the piece.

Practical Application: Improvisation and Composition: Understanding scales, modes, and keys opens up endless possibilities for improvisation and composition. Use your knowledge to:

a. Improvise Melodies: Explore different scales and modes to create melodic improvisations over chord progressions. b. Compose Original Music: Apply your understanding of scales, modes, and keys to create compelling chord progressions and melodies.

0 notes

Text

Day 2 - Music Theory (CAT)

There’s a Quizlet set here if you want to study these!

L'escala (f.) - Scale

el to - whole step

el semitò, el mig to - half step

major - major

menor - minor

natural - natural

harmònica - harmonic

melòdica - melodic

cromàtica - chromatic

de tons - whole-tone

pentatònica - pentatonic

el mode - mode

el mixolidi - mixolydian

el lidi - lydian

el frigi - phrygian

el dòric - dorian

la transposició - transposition

la modulació - modulation

El pentagrama - Staff

la clau - clef

la clau de sol - treble clef

la clau de do - viola clef, C clef

la clau de fa - bass clef

l'armadura (f.) - key (signature)

el bemoll - flat

el sostingut - sharp

el becaire - natural

la indicació de compàs - time signature

la pulsació - beat

el compàs - measure, bar

l'anacrusi - pickup

la barra (de compàs) - bar (line)

la barra senzilla - single bar

la doble barra - double bar

la barra final - end bar

la barra de repetició - repeat bar

l'inici de repeticio (m.) - start repeat

el final de repetició - end repeat

La nota - Note

el silenci - rest

la rodona - whole note

la blanca - half note

la negra - quarter note

la corxera - eighth note

la semicorxera - sixteenth note

la fusa - thirty-second note

amb punt - dotted

la nota ornamental - grace note

la lligadura - slur, tie

L'interval (m.) - Interval

l'uníson - unison

la segona - second

la tercera - third

la quarta - fourth

el tríton - tritone

la quinta - fifth

la sexta - sixth

la sèptima - seventh

l'octava (f.) - octave

l'acord (m.) - chord

la tònica - tonic

la dominant - dominant

la subdominant - subdominant

disminuït - diminshed

augmentat - augmented

l'acord de sèptima (m.) - seven chord

#okay i'll do the others tonight#this was slightly better hopefully i still stand a chance#30 days of vocab november#general:vocab#catalan:general#catalan:vocab#catalan:challenge#i actually really needed to do this because my musescore is in catalan and i didn't know a lot of the words

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The key of G major is a sharp key.

Use the following heuristic to determine which keys are what:

For flats:

Bb Eb Ab Db Gb C F

For sharps:

F# C G D A E B

To determine the major key with a given number of flats/sharps, start counting from after C, going left, wrapping around. For example: 2 flats is Bb major. 3 sharps is A major.

To determine the number of sharps/flats in a given major key, locate the key name and apply the same counting method. For example: Eb major has 3 flats. F# major has 6 sharps.

It is worth noting that this model works for any diatonic scale/mode, provided you use the right home note. Here they are, from lightest to darkest:

F lydian

C major

G mixolydian

D dorian

A minor

E phrygian

B locrian

To use major, we center on C. To use minor, we center on A.

Minor, flats:

Bb Eb A D G C F

Minor, sharps:

F# C# G# D# A E B

Whatever is to the left of the home note will be affected by the sharp or flat in the name.

"Showtime Ruler" is in E minor, which is the same key signature as G major, being its relative minor. You may have confused it with the parallel minor, G minor, which has 3 more flats than G major. Here, I say "3 more flats" because "one less sharp and two more flats" is less simple and introduces a lot of questions, the answers to which are all "no. At least not at this level of music theory."

So while you are correct that G minor does have an Eb(D#), you should be looking at E minor instead, which does not.

Accidentally discovered Showtime Ruler and More Jump More are in the same key (Key of G) or at least share a lot of the same sharps and flats. Showtime Ruler could be in G Minor but idk D#/Eb is not coming through.

Maybe I can make something with this.

Wonderlands x Jump? More More Showtime?

Hmm... Needs work.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rhythm is how we keep track of music. It is a pattern or sound in a song. When a live band is playing, the drummer keeps the rhythm of the music and the rest of the performers play in sync to it.

Time Signature :

= How many beats that are in a bar and how long that those beats last for.

The top number = amount of beats

The bottom number = how long the beat lasts

A time signature with a 4 on the bottom is equal to a quarter note.

A time signature with an 8 on the bottom is equal to an eighth note.

The Time Signature is placed once at the beginning of a piece of music right after the key signature. It is not seen again unless the metre of that piece changes.

Key Signatures :

- Symbol that indicates what key a piece of music is in.

- Represented by sharps and flats.

( Pianokeyboardguide.com, What’s the difference between sharps and flats?

https://www.piano-keyboard-guide.com/the-difference-between-sharp-and-flat.html

, 19/12/2020)

( Pianokeyboardguide.com, Music Key Signatures,

https://www.piano-keyboard-guide.com/key-signatures.html

, 19/12/20)

Strong & Weak beats :

- The first beat in a bar is always the strongest and is referred to as ‘the downbeat’.

- The third beat is also a strong beat but not as strong as the first beat.

-The second and fourth beats are weak.

( MakingMusic.com , Time signatures - a quick guide -

https://making-music.com/quick-guides/time-signatures/

19/12/2020)

Simple Time :

= musical time divisible by 2.

e.g 4/4 - 1and2and3and4and1and2and3and4

If we look at a 4/4 bar, there are 4 beats divided into 2 groups.

So 1 and 2 and 3 and 4 would be :

strong and weak and strong and weak

The strong beats are emphasized.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tMDFv5m18Pw

Compound Time :

= musical time divisible by 3.

e.g 3/4 - one two three one two three

Which would be 3 beats divided into 2 groups.

strong weak weak strong weak weak

We count compound time like a walz.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VaBPY78D88g&list=PLM-jvmJAG4B-Js2QqB1RNFdr6UMbA71ZU&index=9

Complex Time :

= any time not divisible by 2 or 3.

e.g 5/4 - 1, 2, 3, 1 , 2

So, 5 beats divided into 2 groups would be

Stong, weak, weak (3/4), strong weak (2/4)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vmDDOFXSgAs&list=PLyJdNl258mAVUIB7N5XLJ3sJLqenNWiWK&index=10

Meter:

1. Duple meter = Beats grouped in twos.

2. Triple meter = Beats grouped in threes.

3. Quadruple meter = Beats grouped in fours.

These groups are nothing to do with actual note values so can include notes of any duration.

( Dictionary.onmusic.org, Meter , https://dictionary.onmusic.org/appendix/topics/meters ,19/12/2020)

Tempo :

= the speed music is played at.

It is communicated through BPM, Italian terminology and modern language.

BPM = Beats per minute = the number of beats per minute. e.g 123bpm

Italian Music Terms to know :

( landonmusic.blogspot.com, Italian Music Terms, http://landonmusic.blogspot.com/2008/05/italian-music-terms.html , 19,12,2020)

Syncopation :

- Switches the strong and weak beats in a way by placing emphasis on the traditional weak beats.

( Musictheoryacademy.com, Syncopation , https://www.musictheoryacademy.com/understanding-music/syncopation/ 19/12/2020)

Accents :

- Refer to emphases on certain beats or notes.

- It is shown by this symbol > placed above the note you want to be emphasised.

Polyrhythms :

- Layers of rhythms that add to the gaps in a piece of music.

- They originated in african music but have been used in genres such as jazz and rock over the years and are becoming popular in certain sub-genres of electronic music.

Basic Note Durations & Note Equivalency :

( Musictheoryacademy.com, Note Lengths, https://www.musictheoryacademy.com/how-to-read-sheet-music/note-lengths/ ,20/12/2020)

Subdivisions of the bar :

( Guitartutorialonline.com , Note Values, https://www.guitartutoronline.com/beginners/reading-sheet-music/note-values , 20/12/2020)

Rest durations :

( Human.libretexts.org, Note Durations, https://human.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Music/Book%3A_Music_Appreciation_II_(Lumen)/02%3A_Rhythm_and_Meter/2.03%3A_Duration_of_Notes_and_Rests , 20/12/2020 )

(hellomusictheory.com, Types of Musical Notes, Dan Farrant,

https://hellomusictheory.com/learn/types-of-musical-notes/

, 05,01,2021)

The diagram above is called the music note tree and it helps us visualise note values and their relationships to each other.

Dotted notes :

- Composers use dotted notes when they want to make a note last longer than its actual value.

- By placing a dot after a notes head you make the note longer by half of its value.

- So the value of a minim is 2 beats. If we add a dot to that note it make it last for 3 beats.

Tied notes :

- A tied note is a line that joins two notes that are beside each other and that have the same pitch.

- You do this to increase the length of the note.

- So if you tie two minims together they you would play for 4 beats instead of 2 beats played twice.

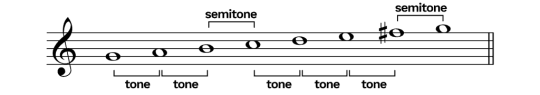

Tones & Semitones :

- Semitone = half step - smallest type of interval

- Tone = whole step = to two semitones

-We use these to make up interval patterns in scales. They are the way we count the distances between notes.

Intervals :

- The distance in pitch between any two notes. The larger the interval the greater the difference in pitch.

- Intervals are named in accordance to their size. For example, an interval of one semitone is called a minor 2nd.

- Intervals can be Harmonic or Melodic.

- If two notes have the same pitch they are in unison.

- Below is a musical interval chart showing

( yourguitarbrain.com , Music Interval Chart ,

https://yourguitarbrain.com/music-interval-chart/

, 05/01/2021)

The Staff (Stave) :

= The 5 horizontal lines we use to write notes, rests, time and key signatures on.

- We place notes either between the spaces or on the lines.

- Extra ledger lines can be added to show a note that is too high or low to be shown on the staff.

- We use single vertical lines to divide the staff into short sections called bars.

- We use double lines to divide the staff into larger sections and heavy double lines to mark the end of a piece of music.

( Rockhill.instructure.com, What is the staff?

https://rockhill.instructure.com/courses/328/pages/what-is-the-staff

, 19/12/2020)

- The most important symbols shown on the staff are :

The Time Signature

The Key Signature

The Clef Symbol

-Below are some other symbols shown on the staff :

- Tempo markings - on the top = how fast a note is played.

- Dynamic markings - on the bottom = how loud a note is played.

( ( Rockhill.instructure.com, What is the staff? https://rockhill.instructure.com/courses/328/pages/what-is-the-staff , 19/12/2020)

The Treble Clef & The Bass Clef :

- The first symbol you will see on a piece of music.

- This tells you which notes are on the lines or in the spaces.

( pianokeyboardguide.com, The Treble Clef , http://www.piano-keyboard-guide.com/treble-clef.html , 21,12,2020)

( pianokeyboardguide.com, The Bass Cleff, http://www.piano-keyboard-guide.com/bass-clef.html , 21/12/2020)

What is a scale ?

- A scale is a group of notes that are arranged in order of pitch.

- In an ascending , scale each note will be higher in pitch than the previous.

- A scale determines the ‘key’ of a piece of music.

- Most scales will span an octave.

- There are various styles of scales that have unique interval patterns.

- The ‘ diatonic scale ‘ is most used in popular music today.

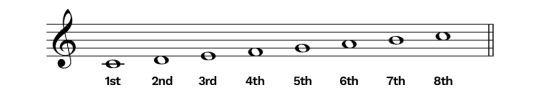

The Major Scale :

- The major scale contains 7 notes and spans one octave.

- The interval pattern goes as follows :

Tone - Tone - Semitone - Tone - Tone - Tone - Semitone

- You can use this interval pattern to form any major scale.

- Major scales are commonly described as sounding happy or joyful.

The C major scale :

- The most known of all the scales.

- This scale is built up of only natural notes ( white notes) so it is easy to learn.

- The scale starts on the root note ( C ) and by using the major scale intervals we can see how it is constructed below.

C -> D -> E -> F-> G -> A-> B-> C

( Basicmusictheory.com , C Major Scale ,

https://www.basicmusictheory.com/c-major-scale

, 19/12/2020)

The Minor Scale :

- Like the major scale, this scale also has 7 notes. The only difference is that the minor scale has a flattened third.

- This means that the third note of the scale is three semitones above the root note.

- There are three different types of minor scale :

The natural minor

The harmonic minor

The melodic minor

- Each of these variants have different interval patterns but all have a flattened third.

- Minor scales are often described as sad or melancholy sounding.

Modes :

- Modes are a type of scale only made up of natural keys ( white notes).

- Each mode has its own distinct sound and feel to it

- The 7 types of modes in order :

- Ionian

- Dorian

-Phrygian

-Lydian

-Mixolydian

-Aeolian

-Locrian

Ionian mode ( C Major scale )

- This mode is exactly equal to the c major scale.

- The root note is C and it contains no sharps or flats.

- C - D - E - F - G - A - B - C

( Hellomusictheory.com , The Musical Modes , Dan Farrant,

https://hellomusictheory.com/learn/modes/

, 19/12/2020)

- Here is an example of a song in Ionian mode :

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SccggMlZQtw&list=PL7ArYjjiz01hKplMJ1uJE1M_6_5lE-VyQ&index=8

Dorian mode :

- The root note is D.

- This is a type of minor scale as it contains a flattened third and a flattened seventh.

- D - E - F - G - A - B - C - D

( Hellomusictheory.com , The Musical Modes, Dan Farrant, ,https://hellomusictheory.com/learn/modes/

, 19/12/2020)

- Here is an example of a song in Dorian mode :

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Su0h07n2ntU

Phrygian mode :

- The root note is E.

- Minor scale because of its flattened third.

- A very recognisable mode due to its minor 2nd interval.

- Contains a flattened 2nd, 3rd, 6th and 7th which without even listening to it gives you the impression that it is a dark sounding scale, which is correct.

- E - F - G - A - B - C - D - E

( Hellomusictheory.com, The Musical Modes, Dan Farrant , , https://hellomusictheory.com/learn/modes/ , 19/12/2020)

Here is and example of a song in Phrygian mode :

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3M_Gg1xAHE4&list=PLY2jaUFlx8dmw1Yi-0OHEnKeLbBuvlTvU&index=8

Lydian mode :

- The root note is F.

- Almost identical to ionian mode, the difference is that lydian mode has a raised fourth note. ( 4th note is a sharp)

- This mode is the brightest sounding of all the modes.

- It is used frequently in popular music as well as by film composers.

- F - G - A - B - C - D - E - F

( Hellomusictheory.com, The Musical Modes, Dan Farrant, , https://hellomusictheory.com/learn/modes/ , 19/12/2020)

Here is an example of a song in lydian mode :

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xqog63KOANc&list=PLCvVga30hxZnIxM2nK3CuwEjowDBcGkC0&index=2

Mixolydian mode :

- The root note is G.

- Similar characteristics to the ‘ Blues scale ‘ because of the flattened 7th.

- Sometimes referred to a ‘ dominant scale ‘

- G - A - B - C - D - E - F - G

( Hellomusictheory.com, The Musical Modes,Dan Farrant, https://hellomusictheory.com/learn/modes/ , 20/12/2020)

Here is an example of a song in mixolydian mode :

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HRD0ghlFSgk&list=PLREeBYwiVRXVHK_9c3TK3n5E99p_0aRHt&index=28

Aeolian mode :

- The root note is A.

- This mode is the same as the natural minor scale.

- It has a flattened 3rd , 6th and 7th.

- A - B - C - D - E - F - G - A

( Hellomusictheory.com , The Musical Modes, Dan Farrant, , https://hellomusictheory.com/learn/modes/ , 20/12/2020)

Here is an example of a song in aeolian mode :

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rH52EjqV-eo&list=PLREeBYwiVRXVvgXM3QJ4Dz4i-IeDgupLE&index=6

Locrian mode :

- The root note is B.

- The least used mode of all.

- Used in Jazz music.

- Sometimes referred to as a half diminished scale because of its flattened 3rd and 5th notes.

- B - C - D - E - F - G - A - B

( Hellomusictheory.com, The Musical modes , Dan Farrant , https://hellomusictheory.com/learn/modes/ , 20/12/2020)

Here is an example of a song in locrian mode :

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V-AqY3veCNI&list=PL1aXQ0zn-P0KqN1BqQKF7oquhz1h26ML3&index=15

Consonance & Dissonance :

- Not every pair of notes sound good when played together.

- Harmonies can be either consonant or dissonant.

- If a harmony is consonant it means that it sounds good when played together.

- If a harmony is dissonant it means that it does not sound good.

Chords :

- A group of two or more notes played together at the same time.

There are a few different types of chords, the most common is the triad :

- Triads are made up of three notes.

- They are built using the root note , the 3rd note and the 5th note with each note being a 3rd of an interval apart.

Track Transcript :

I have chosen to transcribe Eric Prydz - Pjanoo on Ableton live 10.

Here is a link to the original song :

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f-Nd5aWM2Ks

Melody :

- I started with the synth arp melody that we hear throughout the song. This was the hardest thing to get right but I took my time and took plenty of breaks so I wouldn’t get frustrated.

Rhythms :

- The kick and clap keep the rhythm of this song. The kick is a simple four to the floor beat and the clap is a generic house clap on every second beat.

Kick :

Clap :

Chord Progression :

- The chord progression is also pretty straight forward. It is played by the piano in the key of g minor.

Bassline :

- I couldn’t leave this track without recreating the iconic bassline.

1 note

·

View note

Text

one of my coworkers insists on forcing his students to learn musical concepts that are 100% useless in a musicians practical life and it gets on my nerves bc he’ll be constantly complaining about how none of the students are understanding the material and i’m like!!!

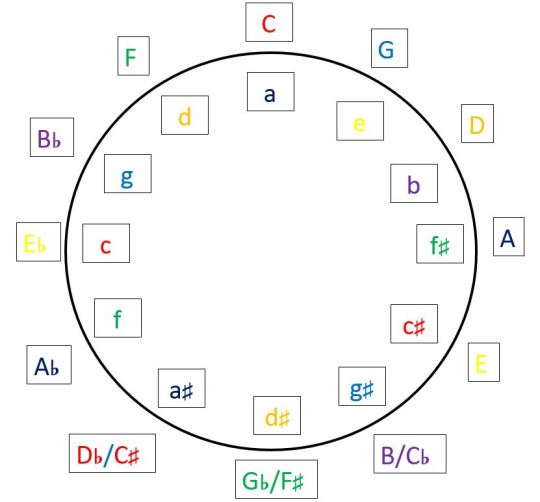

They! Don’t! Need! To! Know! It!

Like, I am dead 100% serious when I say that I have NEVER encountered the ~circle of fifths~ in my career. The circle of fifths is supposed to be a tool to help music students learn and understand key signatures but it’s just a bunch of confusing bullshit. He tries to force them to use the circle of fifths, and none of them get it, and so none of them know their key signatures! Meanwhile, I teach my students key signatures without any circles of any kind, and all of them know it like the backs of their hands. (All you really need to know is the order of sharps and flats, and then how many sharps are in each key signature. Example: The key of B major has 5 sharps. The order of sharps is F G C D A E B. So, the shaps in B major are the first 5 sharps in the order. F, G, C, D, and A.)

He also forces them to learn all of the scale modes. Like, of course they have to learn their majors and all 3 of the different minors, but he also makes them learn all that other shit like lydian and phrygian and locrian and shit.

And like???

I literally have NEVER encountered that shit in my actual life as a musician. We learned it in AP theory in high school, and that was it. It literally only came up exactly one time in my 3rd semester of college, and it wasn’t even part of an assignment. It was in my ear training class where we had to write out some melodies the teacher played for us and the teacher casually mentioned that one of the excerpts he played was in the lydian mode. THAT WAS ALL!!!

Like. You literally do not need to know this shit. MAYBE you could benefit from knowing it if you’re going to be a composer or a music historian or, of course, a teacher.

But when you’re a performer, literally all you need to be able to do is play.

You don’t need to know the circle of fifths. You barely even need to know key signatures at all! All you REALLY need to know is the pattern of wholesteps and halfsteps in major and minor scales. All you really need to know is how to read music (and even then, I’m proof that you don’t even have to be great at reading music in order to excel.) Shit, if you asked me to tell you right now which sharps are in the key of E major, I wouldn’t be able to tell you without having to think hard about it first. But what I CAN do is whip out my violin and bust out a 3 octave e major scale with perfect intonation at hella high speeds.

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

just kidding everyone im doing them all unprompted (except the ones that @if-it-isnt-cello gave me and i did already 🥰)

7. favorite instrument to play? & 8. fav to hear?

cello!

9. favorite instrument that you don’t play?

oof probably bass guitar lmao i wanna learn

10. least favorite instrument?

i hate to say it but basses frustrate me and it’s probably just because of my experiences with them in school

11. instruments you want to learn?

i wanna get better at viola, but instruments that ive never learned and i want to are def bass/acoustic guitar and saxophone

12. what stereotypes about your instrument do you fit?

chaotic for sure, competitive, a lil aggressive

13. piece associated with instrument and what do you think?

i immediately thought of the elgar cello concerto, and i adore it! but another would be the prelude to the first bach suite and that one aggravates me

14. if you had to switch instruments for the foreseeable future, which would you choose?

i actually played viola in orchestra for a few classes instead of cello last year, boy was that an experience (considering the entire viola section aka 3 of them are my best friends)

15. instantly become best at one instrument for a year but never be able to play it again, which would it be?

i couldn’t live without my cello so viola

16. how many clefs can you read?

bass, tenor, treble, alto

17. which is your favorite

anything but treble, but i guess bass bc that’s how i started

18. whos your favorite composer?

shostakovich, my manz

19. what’s your favorite musical era?

romantic

20. favorite musical form?

sonata

21. do you compose?

i arrange frequently, but if composition is necessary i’ll make it happen

22. do you plan to become a music major?

hell ya

23. would you rather teach music or perform?

dammit, if i had to choose i’d perform but i hope to do both

24. favorite key to play in?

e minor but only because brahms and elgar

25. fav major scale?

g major because it’s easy

26. fav minor scale?

a minor because it’s easy

27. favorite type of minor scale?

melodic because it’s cool

28. favorite mode?

lydian

29. like playing scales?

no

30. sharps or flats?

sharps

31. ideal # of sharps? (haha number looks like sharp)

1

32. ideal # of flats?

0 bye

33. preferred names for enharmonics?

f#/Gb, a#/Bb, c#/Db, d#/Eb, there’s more but i’m lazy

34. do you have perfect pitch?

no, but i have relative pitch

35. band or orch?

ORCHESTRA ALL THE WAY

36. marching band or concert band?

concert

37. ever played in a pit orch?

next year !!!

38. in jazz band?

nope (imagine my cello and i tho lmao)

47. something funny your director said?

mine is a walking meme, he constantly says weird things but a favorite is when he called geometry “shape math”

oh my god or when i told him that a parallelogram was an italicized rectangle and he was spooked for the rest of the day

why do we talk about shapes so often?

48. something helpful your director said?

this guy made me wanna be a cellist for real. when he told me that brahms was the reason he became a cellist, something clicked

49. ever taught a private lesson?

nope, kids scare me

50. if you could travel back in time and meet a younger version of yourself, what would you say?

you are not gonna be a doctor. listen to jacqueline du pre. do what makes you happy (it’s music). don’t worry about what your family would have to say, it’s much better to be happy doing what you love then doing something you’re miserable in for someone else. they are NOT going to be disappointed in you!!! also fix your bow hold and make friends with your section sooner

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Music Theory Blog by Sheenagh Shannon (MK)

My name is Sheenagh Shannon. I’m an 18-year-old singer/songwriter currently studying music performance. In this blog I’m going to break down the basic principles of music theory to hopefully help any readers gain a better understanding of the inner-workings of the music we love and listen to.

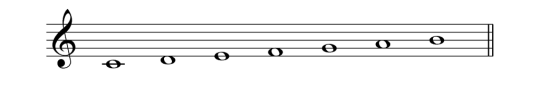

Scales

I’d like to begin by explaining what scales are and how they work. The pictures I will be showing have music written on what is called a stave, and included on the stave is either a bass or treble clef (treble clef being higher, and bass clef being lower.) The notes in the treble clef start with E on the bottom line and ascend from there, whereas the notes in the bass clef start with B and ascend from there.

(Left is the bass clef, right is treble clef.)

A scale is a group of notes that are arranged by ascending or descending order of pitch. In an ascending scale, each note is higher in pitch than the last one and in a descending scale, each note is lower in pitch than the last one. I will explore the two most common types of scales; major and minor.

You must have a note on every single line or space of the stave. One of the most common types of scale is the major scale. These scales are used in an endless variety of songs we listen to. Major scales are defined by the order of which semitones and tones occur. Semitones are whole steps and half steps, and their combination specifies how a scale should be interpreted. For example, the major scale is this:

Tone – Tone – Semitone – Tone – Tone – Tone – Semitone

Or in whole steps and half steps it would look like:

Whole – Whole – Half – Whole – Whole – Whole – Half

This formula can be used to form a major scale starting on any note. Major keys are often correlated with positive emotions – a good example of how a major key can create an upbeat and joyous mood is a song called ‘Breakfast At Tiffany’s,’ by Deep Blue Something. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QSgJ5On8Zso)

The second type of scale I’d like to explain is the minor scale. A minor scale, much like the major scale, also has seven notes but is defined by having a flattened third. This means that the third note on the scales is three semitones above the first note. With major scales, the third note of the scale is situated four semitones above. A seemingly small change, but it makes all the difference!

Tone – Semitone – Tone – Tone – Semitone – Tone – Tone

It’s important to note that there are three different types of minor scale: the natural minor, the harmonic minor, and the melodic minor. Each type of minor scale uses an ever so slightly different formula of semitones and tones, but they all share the minor third in common.

Minor keys are more often associated with music that feels sad or melancholy, but they don’t necessarily have to abide by their assigned moods – minor keys can create intensity, passion, or with the right placement, even joy. Linked is a song called ‘Losing My Religion’ by R.E.M (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OKvCV8MFIaw) a song that begins on the chord of A minor. I believe this is a good example of what a ‘minor’ song sounds like.

Modes

Next, I’d like to discuss modes. Modes are a series of seven musical scales each with definitive qualities and varying sounds. Their names are:

Ionian

Dorian

Phrygian

Lydian

Mixolydian

Aeolian

Locrian

Each of these scales are a type of diatonic scale, which means they have seven notes and have two intervals that are semitones (half steps) and five intervals that are tones (whole steps.) The modes can also be split into two types, major and minor modes. The three major modes are Lydian, Ionian and Mixolydian and the four minor modes are Dorian, Aeolian, Phrygian and Locrian, although it is important to note that the Locrian mode is typically defined as a diminished scale. I’m going to give a couple of examples to show how modes work.

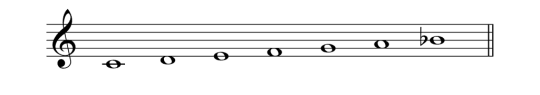

Ionian Mode

As shown above, the Ionian mode is exactly the same as the C major scale with no sharps or flats. It’s just another name for it!

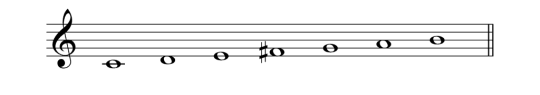

Mixolydian Mode

The only difference between this mode and the Ionian mode is that it has a flattened 7th note as shown above. A song that uses this mode is a song called ‘Wicked Game’ by Chris Isaak (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aid2vMbCNP8) a song that I personally love and listen to quite often. The song is characterized by its haunting and sorrowfully conflicted tone, which exemplifies how modes can be used to create very specific moods or feelings.

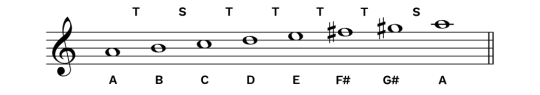

Lydian Mode

The last mode I’m going to show you is called the Lydian mode. It’s the brightest sounding of the modes - quite like the Ionian mode, except it contains a raised fourth note. To play a Lydian scale we sharpen the fourth note of the scale. A song that uses this mode is a song called ‘Flying in a Blue Dream’ by Joe Satriani. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SINl5JY7LhI)

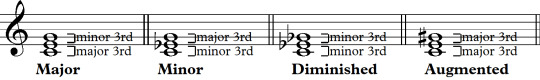

Chords

Chords are the vertical arrangement of notes from a scale. Many people define chords as several notes played simultaneously. Let’s begin with examples of the most basic chord - the triad.

The triad is a class of chords, specifically three-note chords formed by this formula: 1-3-5 or root, third, fifth. There are four kinds:

The major is consonant; the minor is less consonant, but still largely so on most occasions. The augmented chord is very dissonant, and the diminished chord is incredibly dissonant because it contains a tritone (an augmented fourth, or on this occasion, diminished fifth.) This is the basic principle of how chords are formed and what they are. Most songs in existence are built upon a series of chords.

Triads are often extended with some form of the seventh to form a seventh chord. When a chord is called a seventh chord, usually the dominant seventh is meant, which is a major triad with a minor seventh. Because all sevenths are dissonant intervals, any seventh chord is dissonant, because all sevenths are dissonant intervals. A seventh chord is far tenser than a major or minor chord. Jazz music, for example, is a genre that uses seventh chords quite consistently and often seems to treat them as consonant.

Keys

In music, the key identifies the tonal centre of a song. This tonal centre is a note that the whole song revolves around, and each note in the song gravitates towards that home base note. If a song is in the key of C, then each note in the song gravitates towards a C. Below is a list of the 12 keys of music. Key of C Key of Db / C# (en-harmonic keys) Key of D Key of Eb Key of E Key of F Key of Gb / Key of F# (en-harmonic keys) Key of G Key of Ab Key of A Key of Bb Key of B / Key of Cb (en-harmonic keys)

Key signatures can provide an idea as to what key a song is written in. Key signatures appear directly after the clef signs and will tell you what sharps or flats will appear in a song. The number of sharps or flats in the key signature can give you a clue as to what key a song is in. For example, if a song has no sharps or flats in the key signature, the song may be in the key of C. If a song has one sharp in the key signature, it may be in the key of G. I’ve included a chart of key signatures to help explain this principle better.

Note Lengths

Each note written on the stave has a duration as well as pitch. In music notation, a note value indicates the duration of the note. It is the design of the note that tells you its duration, in the same way as the position on the staff tells you the pitch.

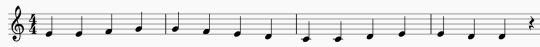

This chart should indicate a clear and simple analysis of how note lengths work. For example, if a song is in 4/4, it would look something like this:

Time Signatures

In music, a time signature alerts you to the meter of the piece that you’re playing. The two numbers in the time signature tell you how many beats are in each measure of music. A piece with a time signature of 4/4 has four quarter note beats; each measure with a 3/4 meter has three quarter note beats; and each measure of 2/4 time has two quarter note beats. The most common time signatures you will come across are:

4/4 - Common time

3/4 - Waltz time

2/4 - March time

6/8 time

The most common meter in music is 4/4. In 4/4, the stacked numbers tell you that each measure contains four quarter note beats. So, to count 4/4 meter, if you tap the beat each time, you would be tapping the equivalent of one quarter note. ¾ is the second most common meter, and each measure has three quarter note beats. In 3/4 time, beat 1 of each measure is the downbeat, and beats 2 and 3 are the upbeats. It’s quite common amongst country music.

Once you start listening closely, you can hear the difference between time signatures. A famous song that uses 4/4 is a song called ‘Runaway Train’ by Soul Asylum (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OzzKBxlIiEQ.) If you count the beats you can hear the difference between that song and a song like ‘Strawberry Wine’ by Deana Carter (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tdWV7PpeTVA) for example.

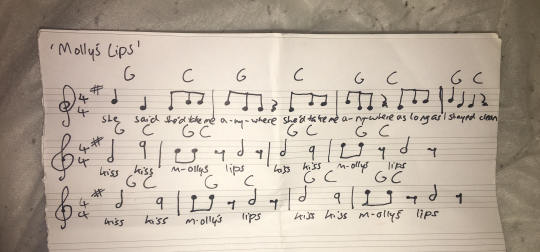

My Transcription

I’ve transcribed a verse and a chorus from a song called ‘Molly’s Lips,’ by Nirvana (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f76GsOBxUg0)

I’ve chosen this song because it’s simple, to be perfectly honest! It gives a good, clear example of what a transcription looks like.

All References And Sources Used:

https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Music_Theory/Chords

http://www.zebrakeys.com/lessons/beginner/musictheory/?id=12

https://www.uberchord.com/blog/music-theory-chords/

https://www.dummies.com/art-center/music/piano/common-music-time-signatures/

https://www.libertyparkmusic.com/musical-time-signatures/

https://www.essential-music-theory.com/music-note.html

I hope reading this blog has been as informative as it has been interesting. Until next time!

Sheenagh :)

1 note

·

View note

Text

Music keys in order

#Music keys in order plus

Key selection charts are included with every Lee Oskar Harmonica. However, if you are just getting started, we feel that owning the first 5 keys listed above would give you enough flexibility to play in many situations.Ĭlick Here to go to the Major Diatonic Key Chart, showing the various keys of music that each key of harmonica can play in, using 1 st, 2 nd, 3 rd & 4 th positions.

#Music keys in order plus

If your goal is to be able to sit in with others, jam with bands and play in most any situation, it would be ideal to have all 12 keys, plus Low F and High G. The biggest selling keys of Major Diatonics are: We also suggest that you consult our Pitch Charts to know which keys are highest in pitch and which keys are lowest, for all four tunings. To learn more about the Melody Maker™, Natural Minor and Harmonic Minor tunings, see the harmonicas page. The following information relates to the Major Diatonic tuning click this link here now. This means that once you learn to play “Jingle Bells” on a C Major harp, you can play “Jingle Bells” on any key of Major harp (G, A, Bb, Low F, etc.) using the exact same blow/draw patterns. It’s important to understand that although the note layout for each key of Major Diatonic will be different, the PATTERN of notes, chords and bends will be the same. Click on 1st Postion / 2nd Position or Basic Chords and Bending to learn more about these topics. You would use a C harp to play in G.ĩ0% of today’s players use 2nd Position for Blues, Rock, Country and Pop music. This means you would start from the draw, accenting draw notes and draw chords, and bending. If you want more “expression” for playing Blues, Rock, Country and Pop music, you will probably be playing in 2nd Position. This means you would start from the blow, accenting the blow notes and blow chords. If you want to play simple melodies and folk music, you will probably be playing in 1st Position. Before we figured out the math for dividing the octave into 12 equal tones, we had to make do with an imperfect system. The 7 modes, Ionian, Dorian, Phrygian, Lydian, Mixolydian, Aeolian and Locrian, come from the earliest forms of western music. In order to know which keys of harmonicas to buy, it is necessary to first determine which style of playing you will be using, 1st Position or 2nd position. Musical modes are a type of scale with distinct melodic characteristics. 2) What kind of music do you want to play? However, if you plan to play with someone else, such as a duo or group, or to play along with a favorite recording, your key selection would be governed by those situations. In other words, any song can be played in any key, regardless of what key the original composer, or artist, may have selected. As you travel around the circle, you find each of the 12 keys in the tonal system. The Circle of Fifths is an order that starts with no sharps and flats and cycles the ring of keys to all twelve keys. In standard music notation, the order in which sharps or flats appear in key signatures is uniform, following the circle of fifths : F, C, G. If you or someone you know would like to author some of the tutorials, please let me know by sending a message to me via the feedback form.To author a tutorial or quiz, only written content is needed. If you intend to play solo, or simply for your own satisfaction, then any key can be used. There’s a method to the madness of key signatures that makes your piano playing easier. Key signatures indicate that this applies to the section of music that follows, showing the reader which key the music is in, and making it unnecessary to apply accidentals to individual notes. 2 - The Order of Sharps and Flats F is the first sharp and the last flat. To determine which keys will be best for you to buy, ask yourself these two questions: 1) Will you be playing solo, or with others? Scales & Key Signatures: Key Signatures, Pt. Many novice players ask us for advice about which keys of harmonicas they should start out with. Gibbons, Greg Cartwright, and Angelo Petraglia to the sessions, marking the first time they've invited multiple new contributors to work simultaneously on one of their own albums.Which Keys of Harmonicas Should I Buy to Get Started? After hashing out initial ideas at Auerbach’s Easy Eye Sound studio in Nashville, the duo welcomed new collaborators Billy F. You will notice that we went back to the start of the alphabet. keep going in alphabetical order to F, then G, followed by A. In sheet music, middle C is the note halfway between the bass clef. LIMIT 2 PER CUSTOMER - ANY ADDITIONAL PURCHASES WILL BE REFUNDEDĪs they've done their entire career, The Black Keys' Dan Auerbach and Patrick Carney wrote all of the material for their new album, Dropout Boogie, in the studio, and the album captures a number of first takes that hark back to the stripped-down blues rock of their early days making music together in Akron, Ohio basements. Middle C is not exactly in the middle of the keyboard, but it’s the centermost C.

0 notes

Text

youtube

Today's piece is continuing some of the ideas from studies 42, 48, and 58. Like 42 (and to a lesser extent, 58), my main goal was to capture the ineffable and paradoxical feelings associated with mundanity. And, like 48, I wanted to add to this idea by minimizing musical drama wherever possible. I feel like 48 didn't actually succeed in that goal well enough, so I'm glad I revisited it.

I mostly achieved this by having very little harmonic motion. The entire piece floats in an A Lydian space. While the accompaniment does change every so often, it only moves to a different voicing of the same underlying harmony, and so I am able to avoid the inherent drama that comes from a chord change. Even if I were to move it to another consonance, a move away from the tonic invites tension by asking the question "how/when will the tonic return, if at all?". To keep the piece from ever getting stale however, I made sure that the accompaniment is busy, with a dance-like motion, and had the melody be very active.

Said melody is easily the driving force in this piece. Like study 42, it isn't quite in the same keyspace as the accompaniment, usually sitting in F# major pentatonic, which has only one more sharp than A Lydian. At the climax, though, I add the next sharp, E#, in the high register to further pull the melody sharp-wise around the circle of fifths. This new note also relieves any stagnation that may be building up from using the same few notes for so long, in a way that reminds me of Bartok's writing.

As always, these pieces are welcome for anyone and everyone to play! All I ask is that you share it with me, because I'd love to hear it done by live players!

#composer#composition#sheet music#classical music#alternative classical music#music#violin#violins#violin music#viola#viola music#cello#violoncello#cello music#violoncello music#string quartet#string quartet music#string ensemble#harmony#music theory#21st century music#Youtube

0 notes

Text

Tell me if this sounds familiar: You are struggling with chords, or you have a lead sheet put infront of you, maybe you nail some triads in the right hand and some fifths in the left hand, *maybe* you even add some color with 9ths or etc, but you hit a wall. Maybe you are really into the blues scale right now, and you even got some decent agility, but where to go next?

Let's zoom out and discuss what improvisation entails. In efforts of simplicity, when we improvise we use chords / scales.

Chords = structured blocks / shapes

Scales = more "horizontal" ideas. Melodies...baselines...etc.

An F block chord in the left hand would be a chord, the F blues scale in the right hand would be a scale. Or etc.

The reason people get stuck, is they view improv as a language without *nuance* When you hear a guitarist doing mind bending chord changes, or ripping through wild harmony, what's happening is they are not living in such a binary world. They see an F7 chord as the first chord of the blues, and they can immediately tap into things like:

- You can use the major OR minor blues scale.

- You can use the minor pentatonic.

- You can cycle pentatonics over it depending on where you start in the. "F major" sound

- You can add sharp 11ths to F7chords for a crunchy sound, derived from the "Lydian dominant" scale

- You can bend the heck out of the 4th degree to the sharp 4 for that classic bluesy sound.

- You can play a very simple groove between the Minor 3, and 1.

-You can groove out in the bass A La funk

There's options!

Where people get held back, is they view "one option as the major thing." On top of this, when they make mistakes, they needlessly shame themselves when mistakes are required and necessary!

To achieve success therefore, we were inclined to use an *exploratory* approach. We can dovetail into all these options, while a teacher or course helps give you guidance and quick results.

Many inexperienced teachers don't realize this. Guilty as charged earlier in my career. Their thinking is too binary. They will put a chord in your left hand, have you playing the blues scale in the right hand, and call it a day. That is *not* really a lesson though. That is using immediate satisfaction, less so lasting progress. Big difference.

If you want to make progress as an improvisor, take a step back, listen, and EXPLORE with intention. Improvisation is a range, not an absolute. We don’t need a magic way.

We just need to perhaps give ourselves grace in knowing the only way the matters most is what gives us progress that day.

Hope you make some great, safe mistakes today likewise 🙂

Follow the music.

- Joey

1 note

·

View note

Video

youtube

Been listening to this piece - Beethoven’s Heilige Dankesang, or Holy Song of Thanksgiving, based on a period of illness endured by the composer - a lot in the past week, inspired by this wonderful visualisation by Stephen Malinowski.

The structure (as excellently demonstrated in this talk by Rob Kapilow, with grainy VHS performance of the piece by a string quartet) of the movement is a series of preludes and ‘hymn’ (or chorale) sections - illustrated in the visulaisation by a transition from clear circles to smoky expandings rings - all in “der Lydischen Tonart” or the Lydian mode, on F.

The three prelude and hymn sections and interspersed by contrastings sections in D Major, first marked “Neue Kraft fülend", ‘Feeling New Strength’. As Kapilow explains in his talk, the Lydian section of the piece is very calm and lacking in tension - Lydian being one of the old ‘church’ modes - and then suddenly it launches back into 19th century tonality with the addition of the two sharps, F and C, from the D Major key, which is particualrly striking in the animation as the style and colours shift.

As Malinowski explains in this ‘listening guide’ to the animation,

Because the passages in Lydian mode are slow, reverent and introspective, I've chosen relatively subdued colors for the pitches in that mode (F, C, G, D, A, E, B).

All twelve pitches are used in D major sections, and I've used vivid colors for the five added pitches that are not in the Lydian mode (F#, C#, G#, D#, A#).

The order of colours follows the circle of fifths (starting from the tonic or I, to the dominant or V, and so on):

Another good resource is this interactive Circle of Fifths, where it can be seen that the Lydian mode on F uses the same notes as the A minor key (or technically, scale) that the quartet as a whole is written in (but with A as the tonic, not F; while in D major A is the dominant)

Also looking at the score I was (very painstakingly) able to work out how the opening figure of the movement (C, A, G, C an octave above, taken up in turn by each instrument) follows the dominant-mediant-(super)tonic pattern while also creating harmonies of a fifth (as the G of the first violin is joined by the first C of the second) and then a minor third (A-C).

Unfortunately there’s too much information I think there too show graphically and instantly; I wish I was able to hear it just by ear, or if I’d had more exposure before to the structure and mathematics of music.

1 note

·

View note

Text

1.2 Scales

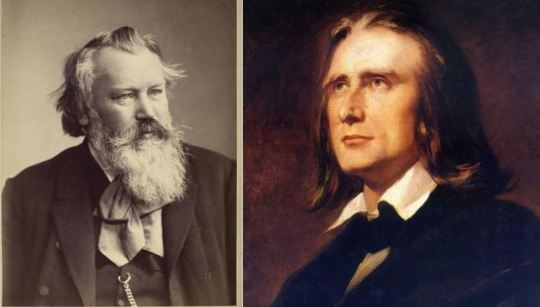

The year is 1863 and Johannes Brahms, at the age of 30, has fastened a political statement. Completing composition of Variations on a Theme of Paganini, Op. 35 and publishing it as a piano study with the designation “studien”, he has aligned himself with the followers of the late, musical conservative, Robert Schumann. This antagonized the progressive New German School in Weimar. Indeed, we’ve been dropped into the center of the War of the Romantics. Sound familiar? Essentially, old versus new music. How about now?

Opposing Ideals: (left) Johannes Brahms, (right) Franz Liszt

Encouragement abound for the interested reader to continue digging! The combatants, musical pieces, critiques, newspaper headlines, etc. are all worth their own discussion. Today though, the thirteenth variation of Paganini’s twenty-fourth caprice deserves special mention. Within the ledger lines of the sheet music is a very special motion called a glissando. As it takes place on a piano, it could even be called discrete glissando, meaning that there is audible gliding between two notes, with distinct tones heard between the glide’s endpoints.

This is clearly from Disney’s Peter Pan.

Picture the above photo, except less pirate-y... and more glissando. Piano glissando can be: all the white keys, or all the black keys, or with impressive timing, every key in order. During these moments in the variation, the pianist cares less about what notes are being used in the overall piece. The same cannot be said for everywhere else in the music. There are some notes during the melody which when played would sound very off indeed.

Why is this happening? In effect, the piece of music has been restricted to a set of acceptable notes to limit dissonance. In Western music (our system of choice), the set of acceptable notes is a seven-pitch, or heptatonic, scale. So five of the constructed notes discussed last time are thrown out. These notes are chosen based on the special rules of the scale and there are a lot of them. Seven very popular sets of rules are called Ionian, Lydian, Mixolydian, Dorian, Phrygian, Aeolian, and Locrian. These are also called modes, and some theorists would be quick to note that the relationship between modes and scales are more subtle than described above. Let’s ignore that until a bit later.

The two modes to be discussed initially are the Ionian and Aeolian modes, more commonly referred to as the major and natural minor scales.

The Major Scale

We can start from C4, or middle C, at 440*(1/2)^(3/4) Hz, or 261.6 Hz and move up two whole steps, then a half step, then three more whole steps, and finally another half step. This brings us to the next octave in our initial pitch class, C5.

So the notes in the C major scale are: C, D, E, F, G, A, and B. Super easy! No accidentals required. We could also put the twelve semitones into a ring and draw connecting lines as follows.

Doing the same for every major scale makes... a mess... but it’s fun to visualize.

The Natural Minor Scale

This time, our progression moves through a whole step, then a half step, then two whole steps, then another half step, then two final whole steps. Using any of the diagrams above, we see the set of pitches in the A natural minor scale are A, B, C, D, E, F, and G! Again, really easy with no accidentals!

This means though that C major and A minor are actually the same set of notes, and only the ordering is different. Another phrasing would be that A is C’s relative minor. Conveniently, we can pair up all relative scales by rotating the above circle. G♯ sits to the left of A, and is therefore the relative minor of B major, which sits to the left of C. This can also be reversed for relative majors!

Alternatively, G major and G minor would be considered parallel, because they have the same base tone, called the tonic.

Writing the two scale progressions with whole (w) and half (h) tones, we say the major scale follows w,w,h,w,w,w,h and the natural minor scale is w,h,w,w,h,w,w. Note again a rotational relationship. Moving the first two letters of the natural minor scale to the end produces the major scale!

Other Minor Scales

There are also the harmonic and melodic minor scales which raise the seventh note or the sixth and seventh notes by a half step. So the harmonic A minor (hereafter Am) is A, B, C, D, E, F, G♯ and the melodic Am has an additional sharp with F♯ instead of F.

The Rest of the Modes

So where do the other five modes come in?

Consider again the C major scale. When it starts on C, it is the Ionian mode. Now shift the scale to D, but keep all the original tones: D, E, F, G, A, B, C. This is D Dorian. It is essentially the minor (Aeolian) scale but with a raised sixth note. Continue shifting to E. This is E Phrygian. Then F Lydian, G Mixolydian, A Aeolian, and finally B Locrian. Not so tricky after all. The order of these modes can be remembered by a mnemonic device such as I Don’t Particularly Like Modes A Lot.

The Circle of Fifths

So now we fast forward 155 years and the modern musician reads from left to right and sees two things: a clef and a series of accidentals. Odds are it’s a treble clef but the accidentals are relatively unpredictable. These describe the key of the piece, or movement, or section. Take for example a piece with no written accidentals following the clef:

Can you guess the name of this one? We know because of the key signature, which in this case is blank, that this song is either in the key of C major or A minor. To determine between the two, one would need to look at which tone is being positioned as the tonic through phrasing and other analysis. As a freebie, the excerpt of Ode to Joy above is in C.

Not all key signatures are so simple however. Generating a Dm scale gives the set of notes: D, E, F, G, A, B♭, C. The relative major, B, has five sharps!

In the first two bars of Scarborough Fair, the pianist never even gets to play a B♭, but the signature is more about the overall key and tonic center no matter how frequently the flat accidental is added.

The specifics of each key and how many flats are present is all too much for the average musician to remember right away. One of the most important tools of introductory music theory is called the Circle of Fifths. This tool has a myriad of interesting properties to be discussed over the next several lectures which relate keys and chords and progressions and so on. Leave space for each of the twelve semitones to fit inside and outside of a circle. Start with the key of C at the top. The next fifth is the fifth note in the current scale progression. So the fifth to the right of C is the fifth note in C major: G. Then, jumping by fifths in the same way as in Pythagorean tuning, we wind around the circle until we return to C. On the inside, we can plot the relative minors using the rotation trick again.

To remember the ordering of the fifths, students often implement other mnemonic devices. In this case, clockwise from the key of F might read: Father Charles Goes Down And Ends Battle. Likewise, counterclockwise from B♭ reads: Battle Ends And Down Goes Charles. This works for the minors also.

So how might this help remembering the accidentals in each key? Consider that C has neither, while G has... G, A, B, C, D, E, F♯... one sharp. From writing out Dm earlier, we know the relative major, F, contains one flat! Likewise, D has two sharps: F♯ and C♯ and B♭ has two flats: B♭ and E♭. Incredibly, the pattern continues all the way around the circle.

Can you guess how the War of the Romantics ended? If the fight between classical and more modern music is unsurprising to you, its because notions of the war are still present even today. Sooner than later, proponents of House and Alternative styles might be competing with a newer form of music not yet invented.

For Thought:

1) Glissando and portamento are two words which both essentially mean a slide between notes. Many individuals however would be quick to point out subtle differences. Try to construct as accurate of definitions for each as possible, or argue towards the idea that they are in fact the same.

2) Identify one system of music which does not use heptatonic scales and describe their alternative.

3) Construct any natural, melodic, and harmonic minor scales that have not yet been discussed and calculate the frequency differences between the sixth and seventh tone for each scale. Generate the D♭ Locrian mode from the appropriate major scale and indicate which major scale was used.

4) Determine the order that flats and sharps appear as one moves around the circle of fifths. Does this line up with the order they appear in key signatures? Do the overlapping areas at the bottom of the circle cause any issues?

5) Eduard Hanslick once said of Wagner’s Götterdämmerung, “One can listen to this incoherent ardour amidst the fluctuations of deafening and nerve-racking orchestral effects for only a short time without relaxation.” Which side of the war was Hanslick likely on? What specific type of music was he against?

Next Time: Chords

#music theory#circle of fifths#brahms#liszt#richard wagner#hanslick#major#minor#heptatonic#glissando#music scales

1 note

·

View note

Text

Recording guitar:

When recording a guitar, a good microphone to use is an “Shure SM57” microphone. It is a dynamic microphone for stage use. (It can also be used for vocals). To get a more precise and clear sound, your going to want to set up the mic as an “On-Axis” mic setup. This setup is when the mic is directly head on with the speaker in the amp. If it were at an angle to the speaker, it wouldn’t accentuate the sound clearly. It would sound “Compressed” or even “muffled”.

For this recording, I used a Stratocaster with single coil pickups. I had the selector switch on the neck pickup. This gives it a mild sound and calms any natural treble that may come out of the guitar.

No effects were used on the recording. Just a guitar plugged into an amp, nothing else. This gives it a extremely natural tone which encourages the player to choose carefully on what they play because of the “nakedness” of their sound. It challenges your technique and connection between notes.

This kind of tone is also a great indicator if someone really plays with feel or not. The reason why is because when you really have a connection emotionally with what your playing, you emphasise and accent some notes and quietly play others. In a sense, your creating a musical story with action and sometimes mellowness. That’s the art of playing in my opinion, and the “dry naked” tone really leaves you with that reminder.

I’ve been using a compressed sounding overdrive sound. It’s quite interesting because it’s fairly obscure in some ways.

On the amplifier, (VOX VT40 Valvetronix)

I’ve been using these settings:

Gain: 5

Treble: 8

Middle: 10

Bass: 0

Also, I’ve been using single coils for this sound. I nearly always use either the bridge pickup or the middle pickup. (3rd Switch on Strat).

No effects are used except overdrive. No reverb or nothing. Those settings are also good for clean guitar aswell.

The way I’ve come to find this tone, is because I wanted to replicate a tone in RHCP’s 1991 album “Blood Sugar Sex Magik”. Particularly in the song “Give It Away”, is where I come to find the tone.

For many years, I’ve been drawn to Ray Manzareks VOX organ. “The Doors” is certainly a very talented band with a amazing reputation of un-ending creativity. But Rays organ really sets the mood for the band and gives the songs the character their known for. I don’t know why I decided to blog this, but i just appreciate their creativity. The organ has a sense of pure horror but absolute happiness and joy at the same time.

I’ve been studying ancient Arabic musical techniques and how they played their music. I’ve tuned my guitar to how a instrument called, “The Arabic Oud” would of been tuned. The “Arabic Oud” was made and introduced to Arabia somewhere between 272 to 241B.C., under the rule of King Shapur. The Oud is the ancestor or the European Lute which eventually blossomed into a incredibly important instrument famous for its use in the”Renaissance”. In Arabia, the Oud was referred to as “King” or “Sultan” of all instruments. So, it was an extremely important instrument to the people of Arabia. It’s translation is quite simple, in Arabic, “Oud” translated to English, is “From wood”. Basically just saying it’s made from wood.

The tuning in which I tuned my guitar with is in similarity to the “Arabic Oud”. Usually, a guitar would be tuned to:

E A D G B E

But with the Arabic Oud, it’s quite different. There are (like guitars) different amounts of strings sometimes more than 6 or less on an Oud. So since I have 6 strings, I had to do my best to try to tune my guitar accurately with the amount of strings I could actually use. So, my guitar is tuned like this...

C F A D G C

Note: These notes should be tuned 2 or 1 octave down than how these notes would usually be on guitar. The “Arabic Oud” needs to be tuned this way to be authentic to the ancient sound.

When the Oud was in frequent use, the Arabic musicians would play with the solid part of an eagles quill, this would eventually turn out to be the guitar plectrum we know of today because of its nearly identical way on how they used the quill. Modern day Oud players use something called a “Risha”. A slightly elongated plectrum. “Risha” translates to “Feather” in reference to how the instrument used to be plucked.

The song I have been learning, is a song which originated in Turkey. It is called, “Üsküdar’a Giderken. Not much is known about the origins of the song in terms of when it was made and by who. What we do know however, is that it includes the main qualities of authentic ancient music in terms of techniques used. If you run your finger down your guitar neck, it will make a sliding sound. Well, with the Oud, there are no frets at all, allowing you to have infinite gradation between each note when you slide. This contributes to the authentic sound.

The Ancient Arabic people had good knowledge with musical theory. It most probably was not referred as “Music Theory”. But nonetheless they had good knowledge of keeping in tune with eachother. When they used scales in their music, they didn’t call them scales but rather, “Maqam”. There are over 100 “Maqams”that were frequently used in Arabic Music, and that’s quite intense if your trying to remember atleast 10. The scales which the Arabic’s and eventually other ancient inhabitants from surrounding countries used, are actually the same ones we use today!

Some of the scales in which they used are:

Ionian

Dorian

Phrygian

Lydian

Mixolydian

Aeolian

Locrian

Chromatic

Whole tone

Many musicians frequently use these scales even down to this day. But of course there were many more scales that aren’t really used at all or are lost in time. But some ancient scales or “Maqam”, are most likely very compatible with the music you personally play. One of the musical scales or “Maqam” is called “Nahawand”. “Nahawand”, is an ancient version of the Aolien minor scale. Another scale or “Maqam” is called “Kurd”. “Kurd is an ancient version of the Phrygian mode.

Some ancient music can get extremely complicated. Let me explain. So, we’re aware of semitones. Semitones are individual notes that are part of an octave. There are 12 notes in an octave. And those notes are semitones. But, in ancient music, things called “Microtones” were used. Microtones are notes that are played in between the standard western semitone. For example, if someone played a C note on an Oud, it is possible for them to play a sharp and flat version of that note and it would still be classed as 1 semitone. That is a lot to remember if your trying to play an Oud authenticly.

But yes, the ancient world of music is extremely important and interesting to explore. It makes you understand that the people of the ancient world were incredibly advanced and extremely intelligent. So when you look at an instrument, you could ask yourself “I wonder where that originated from”. If you “dive in” you can learn quite a lot. From ancient instruments and ancient techniques, the past is an absolute goldmine for learning. You can bring ancient techniques into modern music and give it an interesting sound. Or, buy yourself an ancient styled instrument and start from the very beginning.

0 notes