#Experience Imperial Chinese Tea Rituals

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Savor Chinese green tea and experience the imperial-level luxury!

[The Origins and Significance of Chinese Green Tea]

Chinese green tea has a deep-rooted history that spans over thousands of years. Its origins can be traced back to ancient China, where emperors and nobles revered it for its exquisite flavors, health benefits, and cultural significance. Today, this traditional tea continues to hold a special place in Chinese culture, symbolizing grace, refinement, and luxury. In this article, we will delve into the origins and significance of Chinese green tea, exploring its rich history and why it remains a beloved beverage.

[History of Chinese Green Tea]

The history of Chinese green tea dates back to 2737 BC during the reign of Emperor Shennong. Legend has it that the emperor was sitting under a tree while his servant boiled water for him. As the wind blew, a few leaves from the nearby tea tree fell into the boiling water, creating a fragrant infusion. Intrigued, the emperor decided to taste the concoction and was enchanted by its delightful flavor and refreshing aroma. Thus, Chinese green tea was born.

During the Tang Dynasty (618-907 AD), tea appreciation became an integral part of Chinese society. It was during this time that the tea processing methods evolved, leading to the creation of green tea as we know it today. The unique characteristics of Chinese green tea, such as its fresh and grassy taste, were perfected during this period.

[The Significance of Chinese Green Tea]

Chinese green tea holds immense cultural significance in China. It is considered a symbol of grace, refinement, and luxury. Offering a cup of green tea to guests is seen as a gesture of hospitality and respect. In traditional Chinese ceremonies, serving and drinking tea is a ritualistic practice that showcases the harmony between nature, humanity, and social dynamics.

Apart from its cultural significance, Chinese green tea is also valued for its numerous health benefits. Throughout history, it has been hailed for its medicinal properties, believed to aid digestion, promote relaxation, boost metabolism, and enhance focus. Modern scientific research has supported these claims, showing that green tea is rich in antioxidants and other bioactive compounds that contribute to overall well-being.

[Popular Varieties of Chinese Green Tea]

China is renowned for its diverse range of green tea varieties, each with its own unique flavor profile and characteristics. Some of the most popular types of Chinese green tea include:

1.Longjing Tea (Dragon Well Tea): Grown in the picturesque West Lake region of Hangzhou, Longjing tea is famous for its sweet and mellow taste. It symbolizes the epitome of Chinese green tea and is often referred to as the "king of green tea."

2.Biluochun Tea (Green Snail Spring): This delicate tea hails from the Dongting Mountain region in Jiangsu province. It is characterized by its curled leaves and floral aroma, offering a refreshing and vibrant taste.

3.Huangshan Maofeng Tea: Grown in the Huangshan (Yellow Mountain) region of Anhui province, this tea is known for its slender and fuzzy green leaves. It has a light and refreshing flavor, often described as subtle and sweet.

4.Xinyang Maojian Tea: Originating from Xinyang city in Henan province, this tea is known for its delicate and tender leaves. It offers a rich and full-bodied flavor with hints of natural sweetness.

5.Gunpowder Tea: Originally produced in Zhejiang province, this tea is characterized by its tightly rolled leaves that resemble small pellets. When brewed, it produces a strong and aromatic flavor, often preferred for making Moroccan mint tea.

[How to Brew Chinese Green Tea]

To truly appreciate the flavors and experience the benefits of Chinese green tea, it is essential to brew it properly. Here is a step-by-step guide to brewing the perfect cup of Chinese green tea:

1.Start by selecting high-quality tea leaves that are fresh and well-preserved. Loose leaf tea is preferred over tea bags for a richer and more authentic taste.

2.Boil water and let it cool for a few minutes to around 176-185°F (80-85°C). Steeping tea in excessively hot water can result in a bitter taste.

3.Place the tea leaves in a teapot or a cup. The general ratio is approximately one teaspoon of tea leaves for every 8 ounces of water.

4.Slowly pour the hot water over the tea leaves and let it steep for 2-3 minutes. Allow longer steeping time for a stronger flavor, but be cautious not to oversteep, as it may result in a bitter taste.

5.Once the desired steeping time has passed, strain the tea leaves and transfer the infusion into a teacup.

6.Take a moment to savor the aroma, and then enjoy the delicate flavors of Chinese green tea.

[Bonus Tip: Reusing Tea Leaves]

Chinese green tea leaves can be steeped multiple times to extract the full flavor. This practice, known as "Gongfu brewing," allows for a more nuanced and evolving taste profile with

Buy Now

#tea#green tea#chinese tea#qiandao silver needle tea#spring tea#black tea#organic tea#tea polyphenols#white tea#luxury tea#imperial tea#health benefits#Experience Imperial Chinese Tea Rituals

0 notes

Text

China’s Greatest Naval Explorer Sailed His Treasure Fleets as Far as East Africa

Spreading Chinese goods and prestige, Zheng He commanded seven voyages that established China as Asia's strongest naval power in the 1400s.

— By Dolors Folch | 7 May 2020

Against a backdrop of the mighty treasure ships under his command, Zheng He stands dressed in white in Hongnian Zhang’s modern oil painting of China’s greatest naval hero. The two main goods traded during his seven great voyages (1405-1433) were silk and porcelain. Photograph By Hong Nian Zhang

Perhaps it is odd that China’s greatest seafarer was raised in the mountains. The future admiral Zheng He was born around 1371 to a family of prosperous Muslims. Then known as Ma He, he spent his childhood in Mongol-controlled, landlocked Yunnan Province, located several months’ journey from the closest port. When Ma He was about 10 years old, Chinese forces invaded and overthrew the Mongols; his father was killed, and Ma He was taken prisoner. It marked the beginning of a remarkable journey of shifting identities that this remarkable man would navigate.

Sponsor to Zheng He, the Ming emperor Yongle—pictured in a 20th-century illustration— moved his capital to Beijing and built the Forbidden City, seat of imperial power. Photograph By AKG, Album

Many young boys taken from the province were ritually castrated and then brought to serve in the court of Zhu Di, the future Ming emperor or Yongle. Over the next decade, Ma He would distinguish himself in the prince’s service and rise to become one of his most trusted advisers. Skilled in the arts of war, strategy, and diplomacy, the young man cut an imposing figure: Some described him as seven feet tall with a deep, booming voice. Ma He burnished his reputation as a military commander with his feats at the battle of Zhenglunba, near Beijing. After Zhu Di became the Yongle emperor in 1402, Ma He was renamed Zheng He in honour of that battle. He continued to serve alongside the emperor and became the commander of China’s most important asset: its great naval fleet, which he would command seven times.

China on the High Seas

Zheng He’s voyages followed in the wake of many centuries of Chinese seamanship. Chinese ships had set sail from the ports near present-day Shanghai, crossing the East China Sea, bound for Japan. The vessels’ cargo included material goods, such as rice, tea, and bronze, as well as intellectual ones: a writing system, the art of calligraphy, Confucianism, and Buddhism.

As far back as the 11th century, multi-sailed Chinese junks boasted fixed rudders and watertight compartments—an innovation that allowed partially damaged ships to be repaired at sea. Chinese sailors were using compasses to navigate their way across the South China Sea. Setting off from the coast of eastern China with colossal cargoes, they soon ventured farther afield, crossing the Strait of Malacca while seeking to rival the Arab ships that dominated the trade routes in luxury goods across the Indian Ocean—or the Western Ocean, as the Chinese called it.

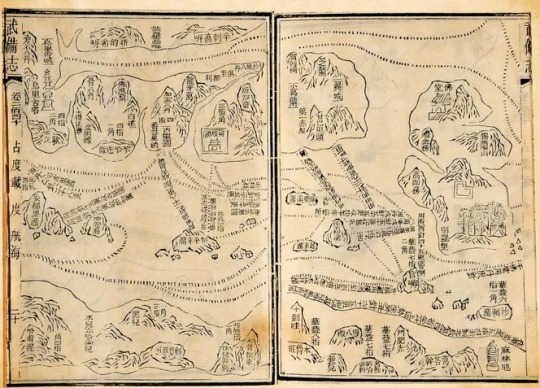

A port map from Zheng He's travels details features that served to position his ships. Photograph By White Images, Scala, Florence

While a well-equipped navy had been built up during the early years of the Song dynasty (960- 1279), it was in the 12th century that the Chinese became a truly formidable naval power. The Song lost control of northern China in 1127, and with it, access to the Silk Road and the wealth of Persia and the Islamic world. The forced withdrawal to the south prompted a new capital to be established at Hangzhou, a port strategically situated at the mouth of the Qiantang River, and which Marco Polo described in the course of his famous adventures in the 1200s. (See pictures from along Marco Polo's journey through Asia.)

For centuries, the Song had been embroiled in battles along inland waterways and had become indisputable masters of river navigation. Now, they applied their experience to building up a naval fleet. Alas, the Song’s newfound naval mastery was not enough to withstand the invasion of the mighty Mongol emperor Kublai Khan. Kublai Khan achieved what Genghis could not: conquering China.

The Mongols and the Ming

Having toppled the Song and ascended to the Chinese imperial throne in 1279, Kublai built up a truly fearsome naval force. Millions of trees were planted and new shipyards created. Soon, Kublai commanded a force numbering thousands of ships, which he deployed to attack Japan, Vietnam, and Java. And while these naval offensives failed to gain territory, China did win control over the sea-lanes from Japan to Southeast Asia. The Mongols gave a new preeminence to merchants, and maritime trade flourished as never before.

On land, however, they failed to establish a settled form of government and win the allegiance of the peoples they had conquered. In 1368, after decades of internal rebellion throughout China, the Mongol dynasty fell and was replaced by the Ming (meaning “bright”) dynasty. Its first emperor, Hongwu, was as determined as the Mongol and Song emperors before him to maintain China as a naval power. However, the new emperor limited overseas contact to naval ambassadors who were charged with securing tribute from an increasingly long list of China’s vassal states, among them, Brunei, Cambodia, Korea, Vietnam, and the Philippines, thus ensuring that lucrative profits did not fall into private hands. Hongwu also decreed that no oceangoing vessels could have more than three masts, a dictate punishable by death.

Ming vase from 1431, of the type traded during Zheng He’s seven voyages. Photograph By Granger, AGE Fotostock

Yongle was the third Ming emperor, and he took this restrictive maritime policy even further, banning private trade while pushing hard for Chinese control of the southern seas and the Indian Ocean. The beginning of his reign saw the conquest of Vietnam and the foundation of Malacca as a new sultanate controlling the entry point to the Indian Ocean, a supremely strategic location for China to control. In order to dominate the trade routes that united China with Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean, the emperor decided to assemble an impressive fleet, whose huge treasure ships could have as many masts as necessary. The man he chose as its commander was Zheng He.

Epic Voyages

Although he is often described as an explorer, Zheng He did not set out primarily on voyages of discovery. During the Song dynasty, the Chinese had already reached as far as India, the Persian Gulf, and Africa. Rather, his voyages were designed as a display of Chinese might, as well as a way of rekindling trade with vassal states and guaranteeing the flow of vital provisions, including medicines, pepper, sulfur, tin, and horses.

The fleets that Zheng He commanded on his seven great expeditions between 1405 and 1433 were suitably ostentatious. On the first voyage, the fleet numbered 255 ships, 62 of which were vast treasure ships, or baochuan. There were also mid-size ships such as the machuan, used for transporting horses, and a multitude of other vessels carrying soldiers, sailors, and assorted personnel. Some 600 officials made the voyage, among them doctors, astrologers, and cartographers.

This version of the “Kangnido Map” is a 1470 copy of an original produced in Korea shortly before Zheng He’s first voyage in 1405. It shows the extent of geographical information compiled by cartographers of the Chinese court during the 1300s. Photograph By AKG, Album

The ships left Nanjing (Nanking), Hangzhou, and other major ports, from there veering south to Fujian, where they swelled their crews with expert sailors. They then made a show of force by anchoring in Quy Nhon, Vietnam, which China had recently conquered. None of the seven expeditions headed north; most made their way to Java and Sumatra, resting for a spell in Malacca, where they waited for the winter monsoon winds that blow toward the west.

They then proceeded to Ceylon (present-day Sri Lanka) and Calicut in southern India, where the first three expeditions terminated. The fourth expedition reached Hormuz in the Persian Gulf, and the final voyages expanded westward, entering the waters of the Red Sea, then turning and sailing as far as Kenya, and perhaps farther still. A caption on a copy of the Fra Mauro map—the original, now lost, was completed in Venice in 1459, more than 25 years after Zheng He’s final voyage—implies that Chinese ships rounded the Cape of Good Hope in 1420 before being forced to turn back for lack of wind.

Treasure ships were the largest vessels in Zheng He’s fleet. A description of them appears in adventure novel by Luo Maodeng, The Three-Treasure Eunuch’s Travels to the Western Ocean (1597). The author writes that the ships had nine masts and measured 460 feet long and 180 feet wide. It is hard to believe that the ships would have been quite so vast. Authorities on Zheng He’s maritime expeditions believe the vessels more likely had five or six masts and measured 250 to 300 feet long. Photograph By Sol 90, Album

Chinese ships had always been noted for their size. More than a century before Zheng He, explorer Marco Polo described their awesome dimensions: Between four and six masts, a crew of up to 300 sailors, 60 cabins, and a deck for the merchants. Chinese vessels with five masts are shown on the 14th-century “Catalan Atlas” from the island of Mallorca. Still, claims in a 1597 adventure tale that Zheng He’s treasure ships reached 460 feet long do sound exaggerated. Most marine archaeological finds suggest that Chinese ships of the 14th and 15th centuries usually were not longer than 100 feet. Even so, a recent discovery by archaeologists of a 36-foot-long rudder raises the possibility that some ships may have been as large as claimed.

At the Tay Kak Sie Chinese Taoist temple in Semarang on the island of Java, Indonesia, a statue of Zheng He shows how far his legacy stretches across Asia. Photograph By Arterra Picture, Alamy, ACI

End of an Odyssey

Zheng He’s voyages ended abruptly in 1433 on the command of Emperor Xuande. Historians have long speculated as to why the Ming would have abandoned the naval power that China had nurtured since the Song. The problems were certainly not economic: China was collecting enormous tax revenues, and the voyages likely cost a fraction of that income.

The problem, it seems, was political. The Ming victory over the Mongols caused the empire’s focus to shift from the ports of the south to deal with tensions in the north. The voyages were also viewed with suspicion by the very powerful bureaucratic class, who worried about the influence of the military. This fear had reared its head before: In 1424, between the sixth and seventh voyages, the expedition program was briefly suspended, and Zheng He was temporarily appointed defender of the co-capital Nanjing, where he oversaw construction of the famous Bao’en Pagoda, built with porcelain bricks.

The great admiral died either during, or shortly after, the seventh and last of the historic expeditions, and with the great mariner’s death his fleet was largely dismantled. China’s naval power would recede until the 21st century. With the nation’s current resurgence, it is no surprise that the figure of Zheng He stands once again at the center of China’s maritime ambitions. Today the country’s highly disputed “nine-dash line”— which China claims demarcates its control of the South China Sea—almost exactly maps the route taken six centuries ago by Zheng He and his remarkable fleet.

Dolors Folch is Professor Emeritus of Chinese History at the Pompeu Fabra University, Barcelona, Spain.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Da Hong Pao and Shui Xian Teas: Savoring the Rich Heritage of Wuyi's Finest

Nestled within the fog-laced cliffs of the Wuyi Mountains, two exceptional teas—Da Hong Pao and Shui Xian—blossom amidst ancient lore and the whisper of aged stones. These teas, steeped in a tradition as deep and rich as the earth from which they spring, offer a profound journey into the heart of Chinese tea culture. Each sip of Da Hong Pao and Shui Xian is not merely a drink but a celebration of history, artistry, and the sublime complexities of nature.

Da Hong Pao: The Imperial Robe of Teas

Da Hong Pao Tea, often translated as "Big Red Robe," is the more illustrious of the two, woven into the fabric of Chinese tea legend. The story goes that this tea saved the life of an emperor's mother, leading the grateful son to cloak the original tea bushes in his own majestic red robe. Whether myth or fact, the legacy of Da Hong Pao is as rich as its flavor. Cultivated from these ancient, now nearly extinct mother bushes, Da Hong Pao carries a regal presence in each leaf.

The taste of Da Hong Pao is a bold symphony of flavors. Known for its robust body and lingering sweetness, it carries hints of stone fruits and a slight, pleasing bitterness, reminiscent of dark chocolate. The tea's complex profile is rounded out with a woody aftertaste that speaks to its mountainous origins, offering layers of discovery with each brew. The preparation of Da Hong Pao is a careful art, requiring precise temperature control and timing to unlock its full, opulent flavor.

Shui Xian: The Ethereal Whisper

Shui Xian Tea, translating to "Water Sprite," offers a more understated but equally captivating experience. This tea is like a gentle echo of the mountain mists, with a subtler flavor profile that invites contemplation. It is often described as having a floral and slightly sweet taste, with a smoothness that makes it accessible, yet deeply satisfying to those who seek serenity in their cup.

The beauty of Shui Xian lies in its versatility and forgiving nature, making it a beloved choice for both novice tea drinkers and seasoned connoisseurs. Its brew is lighter than that of Da Hong Pao, with a golden hue that promises warmth and comfort. The aroma is richly floral, hinting at orchids and the lush greenery of its native landscape, inviting a moment of peace with every sip.

Cultural Significance and Brewing Rituals

Both Da Hong Pao and Shui Xian are steeped in the Gongfu tea ceremony, a practice that emphasizes mindfulness and the art of tea as a meditative ritual. This ceremony is an intricate dance of water and leaf, where time slows and each movement is a gesture of respect to the tea's heritage. The Gongfu ceremony uses small teapots and multiple short infusions to extract the full range of flavors, celebrating the tea's evolving taste across several cups.

These teas are more than beverages; they are cultural artifacts, preserving the essence of a region known for its exceptional tea production. Da Hong Pao, with its imperial connections, is often reserved for special occasions, reflecting its status as one of the world’s most coveted teas. Shui Xian, while also highly regarded, is more commonly enjoyed, making it a perfect daily companion for those seeking a moment of tranquility.

A Toast to Tranquility and Tradition

In Da Hong Pao and Shui Xian, we find not just tea, but a gateway to the past and a testament to the craftsmanship of Wuyi’s tea artisans. These teas invite us to pause and appreciate the slower rhythms of life, offering a cup filled with more than just warmth—they offer a moment of connection to the timeless traditions of the Wuyi Mountains. Whether you are drawn to the bold majesty of Da Hong Pao or the serene whispers of Shui Xian, each tea offers a unique path to discovering the profound depths of fine Chinese tea.

0 notes

Text

The Top 5 Things to Do and See in China

China, a huge and culturally diverse country, presents a tapestry of experiences that captivate the senses and inspire the spirit of adventure. From historical treasures to magnificent scenery, China has a wide range of things to do and see to suit any traveller’s preferences. The Great Wall, a millennium-old architectural masterpiece, is a tribute to China's historical grandeur. The Forbidden City, located in the canter of Beijing, oozes imperial richness and reality, giving visitors a look into the country's glorious history.

Nature lovers may take a peaceful trip along the Li River, which meanders through Guilin's stunning karst landscapes. The Terracotta Army near Xi'an is a fascinating excursion into ancient burial rituals, showcasing China's first emperor's meticulous craftsmanship. Meanwhile, Suzhou's old alleyways beckon with classical gardens, quaint tea establishments, and a rich silk legacy. Each turn on this vast and vibrant continent unveils a new part of China's cultural fabric, promising a voyage full of historical treasures, natural beauty, and rich cultural encounters. China emerges as a mesmerizing destination, encouraging you to dig into its rich legacy and create experiences that will last a lifetime, whether you seek the grandeur of imperial history, the peacefulness of nature, or the beauty of historic alleys.

Suzhou, known as the "Venice of the East," is famous for its traditional Chinese gardens, calm waterways, and silk manufacturing. Pingjiang Road's tiny alleyways are filled with classic buildings and beautiful tea establishments. Suzhou's traditional gardens, including the Humble Administrator's Garden and the Lingering Garden, exhibit Chinese landscape design. Visitors may also learn about the city's silk tradition by visiting silk workshops and observing the complicated silk production process.

Here are some things to do and see in China

1.Investigate the Great Wall of China: An Icon of Ancient Engineering: The Great Wall of China is an iconic emblem of an ancient technical wonder that stretches over 13,000 kilometres across China's northern frontiers. This massive building, intended to ward off invaders, offers amazing views of the Chinese landscape. Hiking along various portions of the wall, such as Mutianyu or Badaling, allows visitors to observe the wall's architectural beauty as well as the historical importance that has echoed through the years.

2. Architectural Opulence: Exquisite Reds, Golds, and Intricate Designs: The Forbidden City, located in the canter of Beijing, is a reminder of China's imperial past. For over 500 years, this massive palace complex functioned as the imperial residence. Explore the exquisite architecture, which is embellished with brilliant reds and golds, as well as the numerous halls and courtyards. The Forbidden City provides a look into China's previous splendour and regality, making it a must-see for history buffs and fans of Chinese culture.

3. Sail the Li River: A Scenic Journey Through the Karst Landscapes of Guilin: The Li River, running through Guilin's beautiful karst scenery, offers a lovely and quiet experience. A ride along this scenic river reveals towering limestone peaks, lush foliage, and quaint fishing communities. For ages, the Li River's surreal beauty has inspired poets and painters, making it one of China's most compelling natural wonders. This excursion will provide photographers and nature enthusiasts with an immersive experience of the country's natural magnificence.

4. See the Terracotta Army, which guarded China's First Emperor.: The Terracotta Army, unearthed in Xi'an in the tomb of China's first emperor, Qin Shi Huang, is a magnificent archeological monument. Thousands of life-sized terracotta troops, horses, and chariots stand watch in the afterlife, defending the emperor. This UNESCO World Heritage Site offers an intriguing look at ancient Chinese burial rituals as well as the sheer grandeur of royal workmanship. Exploring the Terracotta Army transports you to the Qin Dynasty, showing ancient China's creativity and military efficiency.

5. Explore Suzhou's Historic Streets: Gardens, Canals, and Silk: Suzhou, known as the "Venice of the East," is famous for its traditional Chinese gardens, calm waterways, and silk manufacturing. Pingjiang Road's tiny alleyways are filled with classic buildings and beautiful tea establishments. Suzhou's traditional gardens, including the Humble Administrator's Garden and the Lingering Garden, exhibit Chinese landscape design. Visitors may also learn about the city's silk tradition by visiting silk workshops and observing the complicated silk production process.

Finally, the kaleidoscope of experiences provided by Things to Do and See in China weaves a compelling story of history, nature, and cultural diversity. Each location, from the timeless majesty of the Great Wall to the imperial richness of the Forbidden City and the tranquil serenity of the Li River to the archeological marvel of the Terracotta Army, leaves an unforgettable impact on the traveller’s heart.

Consider the ease and rich experiences provided by a China holiday package from India as you plan your tour across China's various landscapes and historical attractions. These programs are tailored to enable a seamless exploration of the Middle Kingdom, ensuring that every moment, from ancient streets to modern marvels, is welcomed with ease and enjoyment.

China's assortment of attractions entices adventurers and culture fans alike, whether meandering through medieval alleys, boating along serene rivers, or visiting ancient landmarks. A journey to this enormous and active country provides not just an investigation of its rich legacy but also the opportunity to make cherished memories amidst China's timeless marvels.

0 notes

Text

I. Jomon Period (c. 11,000 – 300 BCE) / from Neolithic to early small communities / best known forexaggerated, asymmetrical pots with complicated surfaces covered with flame-like coils.II. Yayoi Period (c. 300 BCE – 300 CE) / was both a bronze age and an iron age, signifying that the useof both metals was brought to Japan from the outside / best known for its ritual bronze bells in a verydifferent style from the pots of the earlier period.III. Kofun Period (c. 300 – 600) / best known for the so-called “key-hole” tombs and the various Haniwafigures that accompany them.IV. Asuka Period (552 – 646) / under the influence of the arrival of Buddhism from Korea, Shinto sitesbegan building shrines, the most famous of which is at Ise. Early Buddhist sculpture under the influenceof the Tori school displays Korean stylistic traits (Shaka Triad, Kannon).V. Hakuho Period (645 – 720) / under the influence of Tang China, monks traveled there and broughtback Chinese architectural style to apply to new Buddhist monasteries in Japan (Horyu-ji), though afterbeing destroyed by fire, the overall plan of the new site became uniquely Japanese (lateral plan,asymmetry). International Tang style sculpture influenced Japanese Buddhist sculpture more than Koreanstyles did.VI. Nara Period (710-794) / Considerable influence from the powerful Tang Dynasty in China continued.This was Japan’s most “Chinese” period. The influence of the “esoteric” Buddhist sects gained inimportance bringing more interest in Birushana/Roshana (Vairocana) Buddha and the other“Transcendent Buddhas”.VII. Heian Period (794 – 1185) / The Emperor moved the capital from Nara to Heiankyo (modern Kyoto)to get away from influential monks and Confucian authorities there. Under the control of the powerful Fujuwara clan, the Imperial style was a backlash against Chinese influence. This was the most“Japanese” of any period. This change was also influenced by the late-Tang persecutions ofBuddhism, which further alienated the two countries. As Shinto had a greater influence on Buddhism, theesoteric sects of Shingon the Tendai rose in popularity, as did Pure Land Buddhism (and its “raigo”Amida). Japanese artists sought a purely “Japanese style”, resulting in the Yamato-e painting style—evident in several emaki-mono that employed both the onno-e (feminine style) and the otoko-e(masculine style) painting methods.VIII. Kamakura Period (1185 – 1333) / a feudal era, the Early Medieval Period was controlled by the Minamoto clan, the head of which was the first person granted the title Shogun (General), Minamoto noYoritomo. The capital was moved to Kamakura. Open rule by the military, ostensibly in the name of theEmperor, with continuous infighting among the various Feudal Lords (Daimyo) and their samurai—all ofwhom rejected the “refined” aesthetics of the Heian Period in favor of scenes of heroic warriors, feudingclans, and violence (bushido: the way of the warrior). Yamato-e style continued, but in the service of thisnewly popular subject matter. Angry Dharma Protectors appear (Kongo Rikishi), and Kai School realismdominated sculpture. Shoguns and Daimyo wanted portraits of themselves. Pure Land Buddhismflourished, and Zen was introduced under the influence of Song Dynasty China.IX. Muromachi Period (1392 – 1573) / still considered Medieval Japan (still decentralized feudalregimes of the various daimyo). The Ashikaga clan replaced the Minamoto and moved the capital backto the Muromachi area of Kyoto, trying to rival the aristocratic elite at the Imperial Court. Favoring kara-eto yamato-e, Shoguns promoted all aspects of Chinese culture. The close ties between Zen and kara-estyle were clear, and the three master Zen Priest painters borrowed and adapted Song motifs usingsuiboku-ga and haboku techniques. Japanese gardens, under the influence of Zen, become animportant part of the meditative experience. X. Momoyama Period (1576 – 1615) / the height of Medieval Japan, named for the “peach hill” orchardnear Kyoto. Dominated by two men: Nobunaga (its founder) and Hideyoshi, the Shogun who finallyunified all of Japan. An absolute military dictatorship, the period is a contrast of the “public” world(majestic and showy—castles) and the “private” world (Zen inspired tea aesthetic). Kano school paintingwas dominated by yamato-e style with large bold forms on gold backgrounds. Hasegawa balanced thepublic and private with his large byobu using suiboku-ga in the aesthetic of tea master Sen no Rikyu.Original Japanese raku ware reflected individual tea aesthetics.XI. Edo Period (1615 – 1868) / Tokugawa clan took power from Hideyoshi and moved the capital toEdo (modern Tokyo). He required Daimyo’s families to live in Edo (to assure the loyalty of the war lordswho maintained their castles all over Japan.) Disparities between the “public” and “private” worldcontinued for the aristocracy. The code of the warrior (bushido) became institutionalized in the formalmarshal arts schools, which taught stylizations of warrior behavior—a new emphasis on swordsmanshipaccompanied this (as opposed to equestrian archery that had actually been the method of traditionalsamurai.) Rinpa style rejuvenated traditional Japanese arts and color woodblock prints (nishiki-e)offered the middle-class both ukiyo-e and landscape subjects.XII. Meiji Restoration (1868 – 1912) / after a weakened shogunate, power was briefly vested with theEmperor / Japan was forced to “westernize” to avoid colonialism. Yoga (western style) painting appeared,and Nihonga attempted to preserve aspects of indigenous artistic traditions. Organizations were formedto promote “traditional” arts. Different art schools took up various points of view on the subject. XIII. Modern Japan (1912 – present) Nihonga style was important early, with clear western influence.After WWII, Japanese artists quickly developed an avant-garde and have been on the cutting edge ofcontemporary art and design ever since.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

What is Longjing Tea?

If you are a tea enthusiast or simply looking to explore the rich flavors the world has to offer, then Longjing tea is a must-try. This Chinese green tea is commonly known as Longjing tea and is renowned for its unique characteristics and cultural significance. Let's delve into the special qualities of Longjing tea.

A Long and Storied History Longjing tea originates from the West Lake region in Hangzhou, Zhejiang province, China. Its history can be traced back over a thousand years to the Tang Dynasty (618-907 AD). It gained widespread recognition during the Song Dynasty (960-1279 AD) and was later designated as an imperial tea during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912 AD). The emperor was so enamored with Longjing tea that he personally visited the West Lake region in Hangzhou, where the finest Longjing tea is grown.

Unique Cultivation Process The cultivation of Longjing tea itself is an art form. It grows on the fertile, mist-covered hills surrounding the West Lake, an area known for its ideal climatic conditions. The combination of fertile soil, abundant rainfall, and moderate temperatures contributes to the exceptional quality of Longjing tea.

Hand-picked and Processed The tea leaves are meticulously hand-picked during the early spring season, particularly before the Qingming Festival (around April 5th). Only the tender leaves are selected to ensure the highest quality. The processing involves a series of intricate steps, including pan-firing, shaping, and drying, all executed with great care to preserve the delicate flavor and aroma of the tea leaves.

Distinctive Characteristics One of the most notable features of Longjing tea is its flat, spear-shaped leaves that are smooth and glossy. The tea leaves boast a vibrant green color, a testament to their freshness and quality. When brewed, Longjing tea produces a light golden-green infusion with a refreshing floral fragrance and a subtle chestnut flavor. It has a smooth and mellow taste with a lingering aftertaste.

Health Benefits Longjing tea is not only revered for its taste but also for its numerous health benefits. It is rich in antioxidants, particularly catechins, which help combat free radicals and reduce the risk of chronic diseases. This tea also aids in digestion, improves metabolism, and enhances mental alertness, making it a perfect choice for those seeking a healthful beverage.

Cultural Significance Longjing tea holds a revered place in Chinese culture, often associated with elegance and refinement. It is typically served during important ceremonies and gatherings, symbolizing respect and hospitality. This tea is also a popular gift, reflecting the giver's appreciation and reverence for the recipient.

Tea Appreciation and Enjoyment The art of tasting Longjing tea involves appreciating its color, aroma, and flavor. Traditionally, the tea is steeped in glass or porcelain teapots, allowing the tea leaves to gracefully unfurl. Observing the dance of the tea leaves as they release their essence into the water is a visual delight, adding to the overall experience.

To fully appreciate Longjing tea, one must engage in the rituals of preparation and consumption. This requires taking the time to observe the leaves, inhale the aroma, and savor each sip. It is an opportunity to slow down, connect with nature, and appreciate the craftsmanship behind every cup of tea.

In Conclusion Longjing tea has a rich history, meticulous cultivation, and distinctive characteristics that make it a timeless treasure in the world of tea. Whether you are a seasoned tea connoisseur or a curious beginner, exploring the depths of Longjing tea will bring sensory pleasure and cultural enrichment. Indulge in a cup of this exquisite tea and experience the heritage of one of China's most revered beverages.

Longjing tea is more than just a beverage; it is a journey through centuries of tradition, artistry, and profound connection to the land and its people. Whether you are an experienced tea aficionado or a novice, Longjing offers a unique and enriching experience. When tasting Longjing tea, take a moment to appreciate the history, craftsmanship, and stories behind this legendary Chinese green tea. It's not just about drinking tea; it's about embracing tradition. So, what is Longjing tea? It's a sip of history, a sip of nature, and a taste of China's rich cultural heritage.

0 notes