#Ernest Haller

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

Mildred Pierce (1945) dir. Michael Curtiz

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (Robert Aldrich, 1962).

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Director Robert Z. Leonard, actor Luise Rainer, and cinematographer Ernest Haller eating apple pies on set of ESCAPADE (1935).

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Man of the West (1958)

When a classic film fan thinks of Gary Cooper, images of a distinct American hero spring to mind. No, not the rugged, justice-minded, occasionally ill-mannered gunslingers of John Wayne. Nor the stand-up, Bill of Rights-affirming protagonists a Henry Fonda may have played. The deeply introverted Cooper played his heroes closely to his actual self – minimal facial acknowledgements outside of some comedies, carefully-chosen responses for a man of few words, and always humble (but never self-deprecating). In pairing Cooper with director Anthony Mann, Man of the West, distributed by United Artists (UA), turns the Cooper-esque protagonist on its head. For this late-career role, Cooper assumes a role with elements of that Quintessential Gary Cooper Hero his fans sing his praises for, but also containing an undercurrent of outlaw violence and repentance that seemed antithetical to his past Western heroes.

Director Anthony Mann (1950’s Winchester ’73, 1953’s The Naked Spur) was one of the central figures to that evolution in the American Western. Rather than focusing on a broadly drawn story of good and evil, or white hats versus black hats, Mann’s Westerns across the 1950s delved deeply into the individual psychologies of the individuals driving the action on-screen. How does violence beget violence and how can it consume a person? Can violent revenge be fulfilling? When does one’s sense of personal justice devolve into something uglier and incompatible with their original intentions? Some Westerns before Mann’s entrance in to the genre with Winchester ’73 looked – some deeply, some superficially – into these questions. But Mann is perhaps the first director to pose and probe these questions consistently.

For Man of the West, credit must also be given to his screenwriter here, Reginald Rose (best known for writing the teleplay Twelve Angry Men, later adapted into the 1957 film starring Fonda) in this adaptation of Will C. Brown’s novel The Border Jumpers. With a rich script, stunning performances from the central cast, and intelligent framing from cinematographer Ernest Haller’s (1939’s Gone with the Wind, 1940’s All This, and Heaven Too), Man of the West is essential viewing for Cooper’s fans, and – more broadly – those wanting to see what a 1950s Western could be capable of.

Riding quietly into a Texas frontier town before heading off to Fort Worth by train, Link Jones (Gary Cooper) is not looking for trouble. In his bag, Link is carrying hundreds of dollars to hire a big city schoolteacher for his hometown. As he clambers onto the train, he meets con man Sam Beasley (Arthur O’Connell) and saloon performer Billie Ellis (Julie London). A few hours later while the train stops to forage wood for fuel, four outlaws – Ponch (Robert J. Wilke), Coaley Tobin (Jack Lord), Trout (Royal Dano), and a fourth who is killed – attempt to rob the train. But, in their incompetence, they make off with only one bag. Yes, it just so happens to be Link’s bag. Meanwhile, Link, Sam, and Billie disembarked the train during the robbery attempt and did not climb back aboard as the train fled the scene. The three will start walking towards Fort Worth (the train runs weekly) and to find and shelter and safety, only to reencounter the gunmen. Their boss is an elderly Dock Tobin (an unrecognizable and solid Lee J. Cobb), Link’s uncle. Link, who was once the most accomplished outlaw in Dock Tobin’s gang, has been running away from his violent past for years. The past returns at an inopportune time.

Whatever Link did in his past, it is clear that Dock Tobin regards his criminal instincts as the finest he can recall. Much of that past reveals itself in roundabout references, with people and places mentioned that do not make complete sense to the audience. Without a reference point, Man of the West only hints at someof the terrible things that Link executed in the name of his uncle. Whatever growth in temperament and character Link had in the years since his departure – one that still pains his uncle – lies underneath chilly silence and attentive glances between himself and Dock Tobin.

What does redemption look like, ask Mann and Rose, and can someone with so bloody a past ever achieve it? Like any great Western (or any film), Man of the West will not provide any clear-cut answers. Nor did The Gunfighter (1950) or Shane (1953). But like Shane (not so much The Gunfighter), Man of the West sees its protagonist attempting to do worthy deeds as he stumbles into a situation where a peaceful resolution is anathema to the men who oppose him. And in the case of Man of the West, a peaceful resolution may be impossible because Link Jones once rode with such men, because he wielded violence as a means to an end. Link has found an easy forgiveness from the people he is serving – his new hometown and his wife (only mentioned in dialogue) back home – because they have never even been adjacent to what he wrought. Man of the West never shows us Link’s hometown, his refuge. But here, among rolling hills still terrorized by gunslingers, is where he forged his reputation, where forgiveness means little when staring down the wrong end of a revolver.

In Gary Cooper’s stellar performance do we find that tension between the comforts of his present home and his fear regarding the situation that he finds himself in. It would be one thing if these criminals were unknown to him; it is another thing entirely to know they are led by family. Across this intense situation, Link cannot betray anything other than calm – open fearfulness will be easy prey to Dock Tobin and his men; swagger will only inflame tensions and put Billie and Sam at further risk. In the film, violence becomes not only a way to advance the narrative, but an embodiment of where the character have been and are going – see the fistfight late in the film and Link’s inability to react during a moment of sexual violence against Billie (see below). As Link says later on:

You know what I feel inside of me? I feel like killing… like a sickness come back. I want to kill every last one of those Tobins. And that makes me just like they are. What I busted my back all those years trying not to be.

Playing somewhat against type, Cooper is magnificent in exemplifying his character’s polarities: the homespun silent intimacy and the savvy gunfighter that was and may still be.

That intimacy serves him well with Julie London’s Billie. Though Billie harbors romantic thoughts about Link (and potentially vice versa) and openly says so past the halfway mark, Link’s only goal is retrieve the money, keep Billie and Sam safe, and return home to his wife. London, better known as a singer than an actress, may not have too substantial a role, but there are moments in the script that call on her to portray a soft tenderness or terrible pain. Like Love in the Afternoon (1957), the age difference between Gary Cooper and his female lead (in that case, Audrey Hepburn) is extremely noticeable. Unlike that film, Cooper and London seem to have a better on-screen rapport – and it helps immensely that Cooper’s character rejects romance. So their characters’ interactions, shorn of romance, stay within the bounds of psychological drama, and how they are looking to escape from Dock Tobin and his men. The respect that Link and Billie have for each other and for their choices is always apparent, and that is thanks to both actors.

One horrific moment that somehow got past the Hays Code is the scene where Billie is told by Coaley, at gunpoint, to strip. This moment of sexual violence, thankfully, never comes to full fruition. For those who might be sensitive to such a moment, I would not begrudge you for leaving the room or fast forwarding through that scene. For those that do watch that scene, London’s agony, as Billie, is distressingly raw and realistic. That the scene is framed for what it is – sexual violence, borne wholly out of malice – rather than something romantic that Billie submits to is thanks to Mann, Rose, and cinematographer Ernest Haller.

Haller, noted for his positive, unfussy working relationships with some of Old Hollywood’s greatest leading ladies – Ingrid Bergman and Bette Davis among them – has a keen eye for mixing up types of shots and how to frame the moments leading up to and during a gunfight. Using CinemaScope cameras, Haller uses the wide shots capturing both lush and barren landscapes that also mark the transition between the opening two-thirds and closing third of the film (the film, though set in Texas, was shot in various locations in Southern California). Haller does his finest work in the climactic scene at the ghost town, alternating between medium and medium-close shots to exacerbate the tension and head-spinning wide shots to fully capture the geography of the battle – elevating the emotional and tactile authenticity of the violence on-screen.

youtube

Composer Leigh Harline might best be remembered for his work on Golden Age Disney films including the Silly Symphonies series and Pinocchio (1940; he wrote the melody to “When You Wish Upon a Star”), but do not let his experience at Walt Disney Animation be seen as a pejorative. His score to Man of the West unfortunately does not currently exist in soundtrack form, but the main theme – developed over the course of the score in relation to the narrative – has all the hallmarks you want from an American Western score: lonely French horns suggesting the expansiveness of the West, lyrical strings that suggest yearning and roving. Whoever might have the rights to the score of Man of the West, please consider releasing a soundtrack version as there is so much thematic material that is sadly unavailable for our listening pleasure! On a musical side note, Julie London sung a title tune (composed by Bobby Troup) for Man of the West that ultimately did not appear in the final cut. No musical references to the song remain in the score – perhaps for the best, as the song clashes musically with the score.

Both Gary Cooper and Anthony Mann were reaching the final stages of their association with Westerns. For Cooper, he would appear in three more Westerns: The Hanging Tree, Alias Jesse James (a comedy in which he appears as himself), and They Came to Cordura – all 1959 releases. Anthony Mann, usually associated with James Stewart, would make a final Western in 1960’s Cimarron, before concluding his career with two British productions and two historical epics in El Cid (1961) and The Fall of the Roman Empire (1964). Man of the West is Mann’s last great contribution to the genre; as much as I like and appreciate The Hanging Tree for Gary Cooper, it pales in the face of Man of the West (so too thought a French critic-soon-to-be-filmmaker named Jean-Luc Godard).

Mann, like some of his contemporaries also testing the moral boundaries of the Western in the 1950s, was working in an area not yet fully appreciated by audiences. At a time when Gunsmoke, Rawhide, Wagon Train, and other American Western series ruled American television and before Sam Peckinpah shocked audiences with the graphic violence of The Wild Bunch (1969), a film like Man of the West resided in an uneasy and restless corner of American film history, with few knowing exactly what to make of them. Today, Gary Cooper’s legacy lies between figures more outwardly expressive than he ever was. Reevaluated in time, Man of the West remains an undervalued Gary Cooper movie and performance, a hidden gem of that most American of narrative genres.

My rating: 9/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating. My interpretation of that ratings system can be found in the “Ratings system” page on my blog. Half-points are always rounded down.

For more of my reviews tagged “My Movie Odyssey”, check out the tag of the same name on my blog.

#Man of the West#Anthony Mann#Gary Cooper#Julie London#Lee J. Cobb#Arthur O'Connell#Jack Lord#Royal Dano#John Dehner#Robert J. Wilke#Reginald Rose#Ernest Haller#Leigh Harline#Walter Mirisch#TCM#My Movie Odyssey

0 notes

Text

Joan Crawford as Helen Wright in HUMORESQUE (1946) dir. Jean Negulesco

#filmedit#filmgifs#classicfilmblr#classicfilmedit#oldhollywoodedit#classicfilmsource#ladiesofcinema#moviegifs#userdeforest#tusercamille#usersugar#usermichi#userlenie#joan crawford#humoresque#1946#1940s#*mygifs#*jc#CINEMATOGRAPHER ERNEST HALLER THANK YOU FOR MY LIFE.

594 notes

·

View notes

Text

My best first-watches of 2024 (Top 20 to 11)

20.

Happy Hour [ハッピーアワー] (2015)

Direction: Ryūsuke Hamaguchi

Screenplay: Ryūsuke Hamaguchi - Tadashi Nohara - Tomoyuki Takahashi

Cinematography: Yoshio Kitagawa

19.

The Birds (1963)

Direction: Alfred Hitchcock

Screenplay: Evan Hunter

Cinematography: Robert Burks

18.

Interrogation [Przesłuchanie] (1989)

Direction: Ryszard Bugajski

Screenplay: Ryszard Bugajski - Janusz Dymek

Cinematography: Jacek Petrycki

17.

Babylon (2022)

Direction: Damien Chazelle

Screenplay: Damien Chazelle

Cinematography: Linus Sandgren

16.

The Fifth Seal [Az ötödik pecsét] (1976)

Direction: Zoltán Fábri

Screenplay: Zoltán Fábri - Ferenc Sánta

Cinematography: Györgi Illés

15.

The Browning Version (1951)

Direction: Anthony Asquith

Screenplay: Terence Rattigan

Cinematography: Desmond Dickinson

14.

Das Boot (1981)

Direction: Wolfgang Petersen

Screenplay: Wolfgang Petersen

Cinematography: Jost Vacano

13.

Gone with the Wind (1939)

Direction: Victor Fleming

Screenplay: Sidney Howard

Cinematography: Ernest Haller

12.

The Miracle Worker (1962)

Direction: Arthur Penn

Screenplay: William Gibson

Cinematography: Ernesto Caparrós

11.

Rififi [Du rififi chez les hommes] (1955)

Direction: Jules Dassin

Screenplay: Auguste Le Breton - Jules Dassin

Cinematography: Philippe Agostini

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

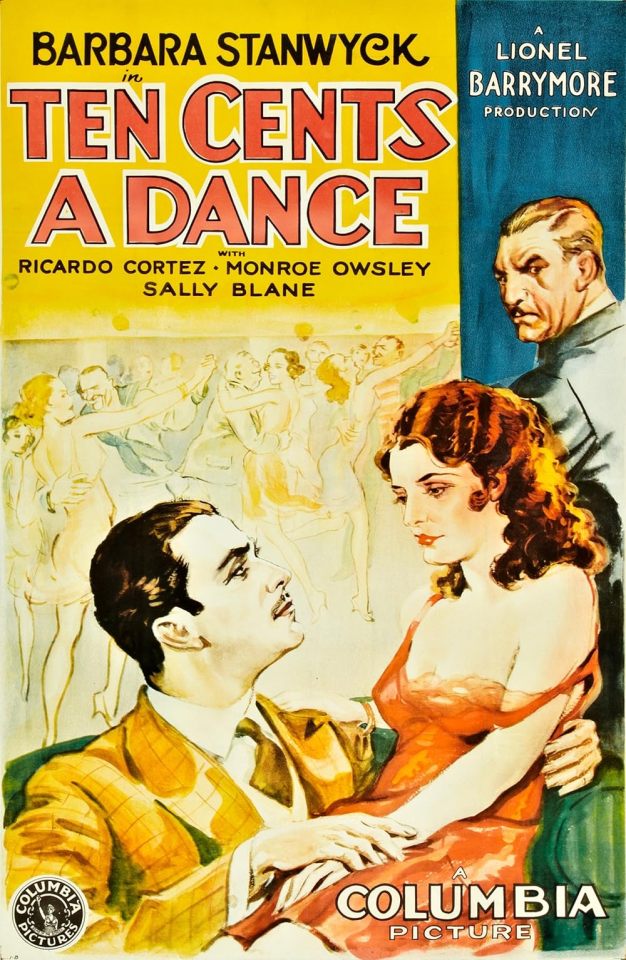

Ten Cents a Dance (Lionel Barrymore, 1931)

Cast: Barbara Stanwyck, Ricardo Cortez, Monroe Owsley, Sally Blane, Blanche Friderici, Phyllis Crane, Victor Potel, Al Hill, Jack Byron, Pat Harmon, Martha Sleeper, David Newell, Sidney Bracey. Screenplay: Jo Swerling, Dorothy Howell. Cinematography: Ernest Haller, Gilbert Warrenton. Art direction: Edward C. Jewell. Film editing: Arthur Huffsmith.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Cast: James Dean, Natalie Wood, Sal Mineo, James Backus, Ann Doran, Corey Allen, William Hopper, Rochelle Hudson, Dennis Hopper. Screenplay: Stewart Stern, Irving Shulman, Nicholas Ray. Cinematography: Ernest Haller. Art direction: Malcolm C. Bert. Film editing: William H. Ziegler. Music: Leonard Rosenbaum.

Rebel Without a Cause seems to me a better movie than either of the other two James Dean made: East of Eden (Elia Kazan, 1955) and Giant (George Stevens, 1956). It’s less pretentious than the adaptation of John Steinbeck’s attempt to retell the story of Cain and Abel in the Salinas Valley, and less bloated than the blockbuster version of Edna Ferber’s novel about Texas. And Ray, a director with many personal hangups of his own, was far more in tune with Dean than either Kazan or Stevens, who were shocked by their star’s eccentricities. Granted, Rebel is full of hack psychology and sociology, attributing the problems of Jim Stark (Dean), Judy (Natalie Wood), and John “Plato” Crawford (Sal Mineo) to parental inadequacy: Jim’s weak father (Jim Backus) and domineering mother (Ann Doran) and paternal grandmother (Virginia Brissac), Judy’s distant father (William Hopper) and mother (Rochelle Hudson), and Plato’s absentee parents who have left him in care of the maid (Marietta Canty). In fact, Jim and his friends really are rebels without a cause, there being neither an efficient cause – one that makes them do stupidly self-destructive things – nor a final cause – a clear purpose behind their madness. Fortunately, Ray is not as interested in explaining his characters as he is in bringing them to life. Unlike Kazan or Stevens, Ray gives his actors ample room to explore the parts they’re playing. There’s a loose, improvisatory quality to the scenes Dean, Wood, and Mineo play together, more suggestive of the French New Wave filmmakers than of Hollywood’s tightly controlled directors. It’s no surprise that both Jean-Luc Godard and François Truffaut were admirers of Ray’s work. At the same time, though, Rebel is very much a Hollywood product, with vivid color cinematography by Ernest Haller, who had won an Oscar for his work on Gone With the Wind (Victor Fleming, 1939), and a fine score by Leonard Rosenman. Most of all, though, it has Dean, Wood, and Mineo, performers with an obvious rapport. At one point, for example, Dean puts a cigarette in his mouth backward – filter on the outside – and Wood reaches out and turns it around, a bit establishing their intimacy that feels so real that you wonder if it was improvised or developed in performance. (In fact, I noticed the gesture because I had just seen Billy Wilder’s The Lost Weekend, made ten years earlier, in which Jane Wyman performs the same turning-the-cigarette-around action for Ray Milland several times. Cigarettes are nasty things but they make wonderful props.)

James Dean as Jim Stark REBEL WITHOUT A CAUSE (1955) dir. Nicholas Ray

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

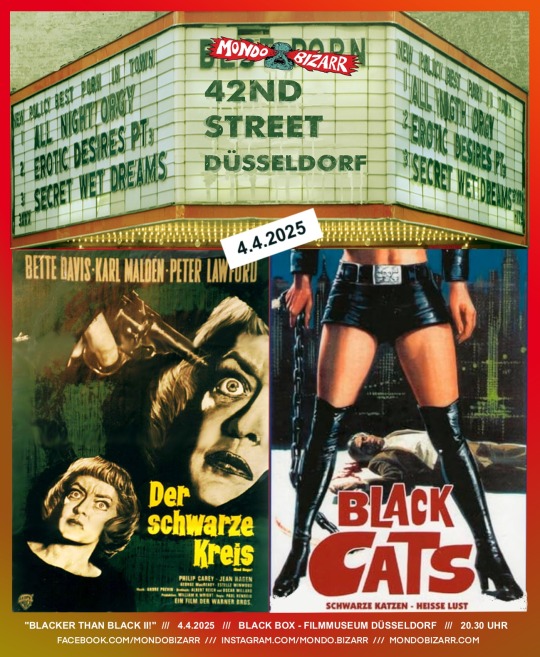

20:30

DEAD RINGER DER SCHWARZE KREIS USA 1964 · 116 min · DF · 35mm · FSK 16 R: Paul Henreid · B: Albert Beich, Oscar Millard, Rian James �� K: Ernest Haller · D: Bette Davis, Karl Malden, Peter Lawford, u.a.

Es gibt in der Filmgeschichte so einige beeindruckende Zwillingspaar Darstellungen eines einzelnen Darstellers, man denke nur an Jeremy Irons in David Cronenbergs ähnlich betiteltem DEAD RINGERS, aber Bette Davis‘ (WHATEVER HAPPENED TO BABY JANE?) Doppelrolle als Geschwisterpaar Edith Phillips und Margaret de Lorca zählt zu den absolut besten: Paul Henreids in wunderschönem Schwarz/Weiß gefilmter Psychothriller lässt die Diva zur mörderischen Höchstform auflaufen!

ca. 22:30

THE BLACK ALLEY CATS BLACK CATS – SCHWARZE KATZEN, HEISSE LUST USA 1973 · 68 min · DF · 35mm · FSK 18 R: Henning Schellerup · B: Joseph Drury · K: Ray Icely · D: Sunshine Woods, Sandy Dempsey, Charlene Mills u.a.

Achtung, Schmuddelkino: Einer Gruppe junger Damen widerfährt Schreckliches und sie schwören Rache, nehmen Schießunterricht und lernen Karate: Sie sind die BLACK ALLEY CATS! Wahres Bahnhofskino jagt hier durch den Projektor, Sex, Gewalt und Niedertracht werden nur noch von den Frisuren und Outfits der Darsteller getoppt! Henning Schellerup stammt ursprünglich aus Dänemark, führte in den 70ern Regie bei diversen Sexploitation Filmen aber war vor allem als Kameramann tätig, unteranderem für den Kult – Santa Slasher SILENT NIGHT, DEADLY NIGHT!

0 notes

Text

Mildred Pierce (1945) dir. Michael Curtiz

#mildred pierce#michael curtiz#cinematography#ernest haller#joan crawford#jack carson#ann blyth#american cinema#1940s

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (Robert Aldrich, 1962).

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

I thought it was pizza but it’s an apple pie director Robert Z. Leonard, Luise Rainer, and cinematographer Ernest Haller are eating in this publicity photo for ESCAPADE (1935).

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

#ProyeccionDeVida

📽 Cine Club. Del Oscar a la Pantalla Grande, presenta:

🎬 “ALMA EN SUPLICIO” [Mildred Pierce]

🔎 Género: Drama / Cine Negro / Melodrama / Maternidad

⌛️ Duración: 109 minutos

✍️ Guion: Ranald MacDougall y Catherine Turney.

📒 Novela: James M. Cain

🎼 Música: Max Steiner

📷 Fotografía: Ernest Haller (B&W)

💥 Argumento: Cuando el segundo marido de Mildred Pierce es asesinado, la policía la interroga. La mujer cuenta cómo ha sido su vida desde que se casó por primera vez y cómo se ha sacrificado para proporcionar a su hija todas las oportunidades que ella nunca tuvo.

👥 Reparto: Joan Crawford (Mildred Pierce), Zachary Scott (Monte Beragon), Ann Blyth (Veda Pierce), Eve Arden (Ida Corwin), Jack Carson (Wally Fay, Wally Burgan), Bruce Bennett (Bert Pierce), Jo Ann Marlowe (Kay Pierce), Veda Ann Borg (Miriam Ellis) y Lee Patrick (Mrs. Maggie Biederhof).

📢 Dirección: Michael Curtiz

© Productora: Warner Bros.

🌎 País: Estados Unidos

📅 Año: 1945

🎥 Proyección:

📆 Sábado 22 de Febrero 🕗 7:00pm.

🏛 Auditorio del ICPNA (av. Angamos Oeste 120 – Miraflores)

🚶♀️🚶♂️ Ingreso libre

🖱 Reservas: https://bit.ly/4gvBFNo

0 notes

Text

Gone with the Wind | Victor Fleming | Ernest Haller

0 notes

Photo

What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? was released on 31 October 1962.

Lukas Heller adapted Henry Farrell’s 1960 novel for the screen, and the film was directed and produced by Robert Aldrich.

After a number of disappointing films, Aldrich left Hollywood for Europe in 1957; he optioned Farrell’s novel hoping it would offer him an opportunity to direct in Hollywood again. Joan Crawford’s career was also in decline (some reports had her as “near penniless” at the time) and eagerly accepted Aldrich’s offer in the film. Crawford suggested Bette Davis, although the two disliked each other. Aldrich asserted that the two "behaved absolutely perfectly“ but publicity stoked the animosity.

What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? was a critical and commercial success, earning back its production costs in 11 days. The film received 5 Academy Award nominations, including Best Actress (Bette Davis), Best Supporting Actor (Victor Buono), Best Cinematography - Black and White (Ernest Haller), and Best Sound (Joseph Kelly). Norma Koch received the film’s only Oscar, for Best Costume Design - Black and White.

Crawford and Davis’ feud played out publicly at the Academy Award ceremony, as Crawford called all the other nominees in the Best Actress category and asked if she could accept the award if one of them was absent. All agreed, and when Anne Bancroft was unable to attend to accept her Oscar for The Miracle Worker, Crawford accepted the award with Davis looking on.

What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? revived the careers of Aldrich, Crawford, and Davis and ushered in the “psycho-biddy” horror film. In 2021 it was selected for preservation by the Library of Congress for its cultural importance.

#what ever happened to baby jane#lukas heller#henry farrell#robert aldrich#joan crawford#bette davis#1962#1962 movies#victor buono#ernest haller#joseph kelly#norma koch#psycho biddy#psycho-biddy

31 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Mildred Pierce (1945) directed by Michael Curtiz featuring Joan Crawford and Ann Blyth

#cinema#mildred pierce#michael curtiz#Budapest#Austria-Hungary#Hungary#joan crawford#san antonio#Texas#ann blyth#mount kisco#new york#cinematography#ernest haller#los angeles#california#james m cain#annapolis#maryland#USA

4 notes

·

View notes